1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a progressive metabolic disorder that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates worldwide. The main types of diabetes include type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), and other types that develop secondary to certain therapeutic interventions or are associated with specific genetic factors. In particular, T2DM accounts for most cases, approximately 96% globally [

1,

2,

3].

Early projections anticipated a rise in global diabetes prevalence from 9.3% (463 million people) in 2019 to 10.2% (578 million) by 2030 and 10.9% (700 million) by 2045 [

1]. However, by 2021, global prevalence had already surpassed the 2030 forecast, reaching 10.5% (537 million), and was forecast to reach 12.2% (783 million) by 2045 [

2]. A more recent analysis by the Global Burden of Disease research group projects that diabetes cases will exceed 1.3 billion by 2050 [

3].

This escalating prevalence in diabetes results from population aging and, more critically, from the global rise in obesity, which consistently exceeds projected figures annually [

1,

2,

3]. Obesity is one of the strongest leading factors of type 2 diabetes, driving further progression of insulin resistance and chronic systemic inflammation, while impairing the function of pancreatic β-cells [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These pathophysiological processes interrelate, establishing a vicious cycle of metabolic dysregulation, eventually exacerbating the risk of vascular, immunologic, and endocrine complications [

4].

The body’s ability to repair and regenerate tissues declines upon dysregulation of its systemic metabolism, contributing in this manner to macrovascular complications, including cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and peripheral artery disease, but also driving in a microscale accident in tiny blood vessels, which can further lead to diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy [

3,

4,

5]. These secondary manifestations carry clinical significance for individuals with T2DM who undergo surgical procedures.

Patients who have diabetes often display delayed wound healing, either by primary or secondary intent, because of impaired tissue regeneration [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. They are also at heightened risk of developing surgical site infections (SSIs) during surgical procedures, through mechanisms that extend beyond perioperative hyperglycemia [

14]. The increase in perioperative risk supports the need for targeted management strategies in patients with diabetes [

14,

15]. Prognostic models consider the presence and severity of diabetes-related vascular complications to assess perioperative risk and predict adverse surgical outcomes [

15,

16,

17].

Particularly, in oral care, several studies indicate that T2DM patients undergoing oral care procedures are also at risk of developing diabetes-derived complications with some added nuances [

12,

13,

18,

19]. The oral microenvironment in diabetes promotes chronic inflammation, which dysregulates growth factor signaling, and impairs regeneration of soft-tissue within the context of the oral cavity; healing protracts while the risk of infection and need for antibiotic treatment of oral wound sites increases [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In the later stages of the healing process, dysregulated angiogenesis and altered macrophage polarization eventually contribute to compromised socket healing in post-extraction surgery [

9,

12,

13,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Current therapies do not fully address the many complications encountered while managing diabetic wound sites [

6,

23,

24,

25]. Consequently, there is a need for alternative adjunctive therapies that target persistent inflammation, impaired angiogenesis, and disruption of immune cell responses during wound healing of diabetic patients. Researchers are exploring the use of adjunctive hyaluronic acid (HA)-based formulations designed to be delivered locally at wound sites. Some of these formulations show promise for patients living with diabetes, promoting tissue regeneration, and improving healing outcomes [

26,

27].

In the oral context, clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of HA in improving wound healing in diabetic patients following tooth extraction [

17,

26]. Furthermore, by incorporating amino acids into wound healing strategies, researchers hope to improve healing by promoting, particularly collagen, critical for tissue repair and restoring immune balance in chronic wounds [

23,

24,

28,

29,

30]. The formulation HA + AA is intended to promote fast healing of ulcerative-erosive lesions, including bullous ones, and of wounds. The mechanism of action of the HA + AA formulation in promoting faster gingival tissue regeneration is based on the hydrating and film-forming properties of hyaluronic acid (HA), combined with the ability of the charged amino acid (AA) mixture to stabilize the HA structure and protect it from degradation by hyaluronidases. Moreover, amino acids contribute to the overall mechanism by exerting humectant, buffering, and pH-balancing effects. Together, HA and AAs help maintain a favorable microenvironment within the gingival lesion, thereby supporting tissue healing and re-epithelialization through a predominantly physico-chemical mechanism of action. In the context of diabetes mellitus, topically applying sodium hyaluronate combined with synthetic amino acids post-tooth extraction has demonstrated potential in enhancing tissue regeneration [

17].

In this clinical trial, we aimed to investigate the efficacy of a topical gel formulation combining sodium hyaluronate (HA) and six synthetic amino acids (glycine, L-proline, L-leucine, L-lysine HCl, L-valine, L-alanine) in enhancing wound healing post tooth extraction in patients with T2DM compared to no treatment. A total of 43 patients enrolled in the study. Participants were randomized into two groups, one received the designated topical intervention (N=21), and the other group served as an untreated control (N = 22). The study assessed the healing index score and socket closure.

2. Materials and Methods

The study received ethical approval from the local ethics committee of the University of Turin (approval code: 0100924 on 15/09/2022). The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT05896319) with registration date 09/06/2023. The study was designed and reported in accordance with the CONSORT 2010 guidelines for reporting of randomized controlled trials [

31]. All participants provided the signed informed consent form. All procedures undertaken during the clinical phase adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the World Medical Association’s (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

2.1. Study Design

This is a single-center, two-arm, randomized controlled trial conducted at the C.I.R. (Interdepartmental Research Center), Dental School, Section of Oral Surgery, Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Turin between September 2022 and February 2024. The study population comprised patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus who required extraction of at least one non-impacted tooth. Prior to enrolment, all participants were fully informed about the study procedures and provided signed written informed consent.

Patients requiring extraction of at least one non-impacted tooth were recruited and treated between September 2022 and December 2023. Subjects who met the following inclusion criteria were eligible for recruitment, including individuals aged 18 years or older; diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus and a documented history of diabetes-related complications (nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, cardiomyopathy, or peripheral vascular disease); and with a requirement for extraction of non-impacted teeth; having provided signed informed consent to participate in the study and with confirmed availability to attend follow-up visits. The exclusion criteria included the presence of platelet dysfunction or thrombocytopenia; ongoing corticosteroid therapy; current smokers; subjects who declined to participate in the study; poorly controlled diabetes mellitus; use of medications known to interfere with wound healing; extractions requiring flap elevation; teeth requiring sectioning with burs; ankylosed teeth requiring bur use for extraction; and the occurrence of apical root fractures during the extraction procedure.

Tooth extractions were performed one at a time. Subsequently, extraction sites were randomly allocated to the test group (Aminogam 6® gel, PROFESSIONAL DIETETICS S.p.A., Via Ciro Menotti, 1/A, 20129, Milan, Italy) and the control group (no treatment), using a computer-generated random sequence (SPSS version 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

2.2. Preoperative Data Collection

All participants received a professional oral hygiene session in advance of the tooth extraction. During the same visit, clinical and radiographic evaluations were performed to collect baseline data. Demographic characteristics recorded included gender, age, ethnic origin, body mass index (BMI), and smoking status. Diabetes-related variables were also recorded, comprising the duration of diabetes, glycemic status on the day of surgery (measured by blood glucose levels), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, and end-organ disease score.

In addition, the pre-operative status of the teeth scheduled for extraction was evaluated, including the number of roots (single- or multi-rooted), the presence of cavities, pulp vitality, any history of endodontic treatment, and the presence of any periapical lesion. The degree of extraction difficulty [

17,

32] was also recorded and classified into three categories based on space relative to mesiodistal distance, crown integrity, and root anatomy as reported by Ruggiero et al. [

17]. Low indicated all parameters were of low difficulty with no more than one parameter of medium difficulty; medium indicated more than one parameter of medium difficulty but none of high difficulty; and high indicated one or more parameters of high difficulty [

17,

24,

33].

Systemic risk was evaluated as reported by Ruggiero et al. [

17], based on the diagnostic and management criteria for diabetic patients provided by Mozzati et al. [

32]. The classification system grouped patients into low/absent, moderate, and high systemic risk. Specifically, the systemic risk classification was based on a composite of parameters, including the end-organ disease score, time in years since diabetes diagnosis, typical blood glucose levels, and the presence of key clinical and treatment indicators [

17,

34]. These parameters were systematically collected to allow for inter- and intra-patient comparisons, while reducing the risk of bias related to baseline variability across patients at baseline.

2.3. Surgical Procedures and Postoperative Care

All the surgical procedures were carried out by the same experienced clinician, a specialist in oral surgery, who was blinded to the allocation of treatment and control groups. Preoperative and postoperative clinical assessments were conducted by trained examiners, who were also blinded to group allocation. Inter-examiner reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa statistic.

Tooth extractions were performed during the same surgical appointment. Local anesthesia was administered using either plexus or alveolar nerve block techniques, with 1.8mL vials of 3% mepivacaine without vasoconstrictor (Opticain, Molteni Dental Srl, Firenze, Italy). Tooth extractions were conducted in a nontraumatic manner, avoiding elevation of a full thickness mucoperiosteal flap to preserve both the alveolar bone crest and soft tissue integrity. Following tooth removal, the sockets were carefully debrided to eliminate any infected or granulation tissue, promoting wound healing. In cases where suturing was required due to underlying blood dyscrasias, nonabsorbable silk suture (Permahand 3/0, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) was applied. All sockets were compressed using sterile gauze immediately post-extraction.

Participants were provided with standard postoperative instructions, including oral hygiene recommendations. In addition, patients in the treatment group received a 15mL tube of the test product for topical application (see postoperative care below). No anti-inflammatory medications or antibiotics were routinely prescribed to avoid potential interference with the mechanism of action of the test product, due to the cytokine-inhibiting effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Prescription of antibiotic postoperatively was recorded as a negative clinical outcome, as it indicated the presence of infectious complications.

The treatment group carried out postoperative care by topically applying the intervention, three times daily, at eight-hour intervals, for seven days. Postoperative care was self-administered following oral hygiene procedures, with patients instructed to refrain from swallowing, eating, or drinking for at least one-hour post-topical administration. Before use, patients were advised to wash their hands thoroughly. They were instructed to apply a layer of the gel directly onto the extraction site to fully cover the socket while gently massaging the area with a finger to ensure even distribution of the product and then compress the treated area with gauze.

2.4. Intervention Product

The product used comprises sodium hyaluronate and a combination of synthetic amino acids, which act as precursors in collagen synthesis (Aminogam 6® gel, PROFESSIONAL DIETETICS S.p.A., Via Ciro Menotti, 1/A, 20129, Milan, Italy). Specifically, the formulation includes purified water, sodium hyaluronate, glycine, L-proline, L-leucine, L-lysine HCl, L-valine, L-alanine, methyl parahydroxybenzoate, propyl paraben, sorbitol, polyvinyl pyrrolidone, sodium hydroxide.

2.5. Clinical Outcome Measures

Wound healing of post-extraction sockets was assessed using a modified version of Landry’s healing index as primary outcome [

17]. The Landry index was initially designed for wound healing by primary intention [

35]. By contrast, post-tooth extraction sockets heal, later progressing through granulation tissue development and subsequent epithelial coverage. To account for this difference, modifications were introduced to adapt the index for socket repair evaluation. In the modified Landry’s healing index, granulation tissue was interpreted as a favorable indicator of early connective tissue formation, rather than a negative feature as in the original scoring system [

17,

35]. This modified healing index incorporated four clinical parameters, tissue color, bleeding, granulation tissue, and suppuration. Each parameter was scored on a scale from 1 to 3, where higher values indicated poorer clinical presentation. The composite score or modified healing index was calculated as the sum of the individual scores for each parameter, ranging from 4 to 12, with higher scores indicating worse clinical outcomes. Specifically, tissue color scored 1 for fully pink gum (100%), 2 when ≤ 50% of red, hyperemic, moving gum, 3 when ≥ 50% of red, hyperemic, moving gum. Bleeding was registered as 1 if absent, 2 if induced by palpation, and 3 if spontaneous. Granulation tissue was scored as 1 if it was pink and firm (fine-grained in appearance), 2 if it appeared red and soft, and 3 if it was brittle, greenish or grayish. Suppuration was assessed by observing the presence of plaque and signs of alveolitis at the socket margins, where 1 indicated no accumulation of plaque on the margins, 2 visible plaque accumulation along the walls of the alveolus, 3 suppuration or clinical signs of alveolitis (

Table 1).

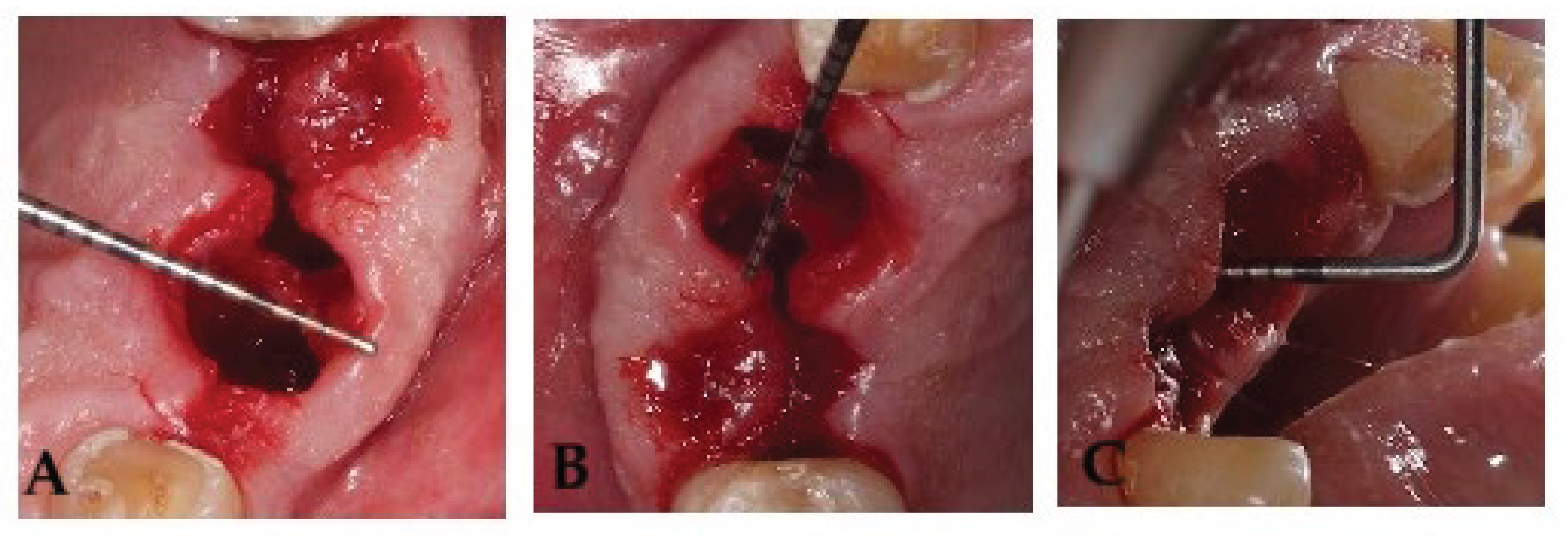

Socket volume was calculated using three linear measurements, expressed in millimeters, the maximum oral-vestibular (OV) diameter, the maximum mesiodistal (MD) diameter, and the socket depth (SD) [

17]. The mesiodistal diameter, oral-vestibular diameter, and socket depth were measured as previously described [

17]. Measurements were taken at baseline (day 0) and on postoperative days 3, 7, and 14 with a Hu-Friedy PCPUNC 15 periodontal probe (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA). Anatomical references were recorded for each tooth extraction to minimize measurement variability across time points (

Figure 1), if complete socket healing had not been achieved by day 21, an additional assessment was scheduled.

2.7. Sample Size

The sample size for this study was calculated based on estimates derived from data presented in a previously published research article [

17,

36].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) with 95% confidence intervals; normally distributed variables were compared using the Student’s

t-test, and non-normal variables using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were summarized as frequencies or percentages and analyzed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as previously described by Ruggiero et al. [

17].

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 43 patients were recruited and randomly allocated to either the treatment group (T6) or the control group (no treatment, C6). The study was conducted between September 2022 and February 2024. Participants were evenly distributed between the two study arms, with 21 individuals assigned to the designated topical intervention (T6), and 22 to the control group (C6). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 2.

During the preoperative assessment, a statistically significant difference in age was observed between the two groups (p < 0.001), with the treatment group presenting a mean age of 78 ± 3.1 years, compared with 70 ± 6 years in the control group. Analysis of the body mass index (BMI) also revealed a significant difference (p < 0.05) with the treatment group displaying a mean BMI of 28.3 ± 5.8 kg/m², versus 33.7 ± 9.4 kg/m² in the control group. With respect to tobacco use, 13 participants in the treatment group and 8 participants in the control group were recorded as active smokers.

Regarding diabetes-related chronic complications, a total of 11 patients were diagnosed with retinopathy (5 in the treatment group, and 6 in the control group), 13 with nephropathy (10 in the treatment group, and 3 in the control group), and 22 with diabetic neuropathy (13 in the treatment group, and 9 in the control group). Diabetic cardiomyopathy was present in 43 patients (21 in the treatment group, and 22 in the control group), while peripheral vasculopathy was noted in 32 individuals (19 in the treatment group, and 13 in the control group). These clinical findings contributed to the overall systemic risk classification. Notably, all patients in the treatment group (n = 21) were classified as having high systemic risk, whereas in the control group, 7 were categorized as having high systemic risk, and 15 were categorized as having moderate systemic risk.

Assessment of periodontal health before surgery, using the periodontal screening record (PSR), revealed a statistically significant difference between the two arms (

p < 0.01), with a mean PSR index of 3.5 ± 0.5 in the treatment group and 4.0 ± 0.5 in the control group. Pre-operative surgery difficulty was classified as low, medium, or high, based on predefined criteria [

17]. No cases were identified as having high surgical difficulty. A total of 25 participants were classified as medium difficulty (16 in group T6, 9 in group C6), while 18 participants were classified as low difficulty (5 in group T6, 13 in group C6) (

Table 2). All enrolled participants completed the study, with no dropouts or losses to follow up. Consequently, all enrolled participants were included in the efficacy and safety analyses. The topical treatment was well tolerated across all subjects, with no adverse reactions or need for antibiotic therapy reported during the study period.

3.2. Modified Healing Index (mHI)

A comparative analysis of the modified healing index, conducted at multiple postoperative time points between day 0 (day of the extraction) and day 14 (at days 0 or D0, day 3 or D3, day 7 or D7, and day 14 or D14), revealed statistically significant differences in early tissue regeneration dynamics between the two study groups (

Table 3). Healing progression within the post-extraction sockets was evaluated using a modified version of Landry’s healing index, incorporating four clinical parameters tissue color, bleeding, granulation tissue, and suppuration. Each parameter was scored on a scale from 1 (optimal) to 3 (compromised) as described above.

At day 3 post-extraction, no statistically significant difference in healing index scores was observed between the two groups (

p > 0.05), with the treatment and control groups presenting mean scores of 5.8 ± 2.1 and 6.0 ± 1.3, respectively. However, by day 7 (D7) and 14 (D14), statistically significant differences in healing outcomes emerged between the two study groups (

p < 0.001). Specifically, at D7, the treatment group displayed a mean healing index of 4.0 ± 0.2 compared with 6.0 ± 1.4 in the control group. This trend persisted at day 14 (D14), at which point the group treated with the intervention continued to exhibit superior healing outcomes (4.0 ± 0.1) compared with the control group (5.0 ± 0.9) (

Table 3).

3.3. Socket Measurements

To estimate the extent of socket closure, the subsequent analysis quantified the volumetric reduction of the post-extraction alveolus over time. To achieve this, the residual socket volume (RSV) was estimated using three principal linear measurements the maximum mesio-distal (MD) diameter, the maximum vestibulo-oral (VO) diameter, and the maximum probing depth (P). These parameters were recorded on day 0, 3, 7, and 14 to evaluate volumetric and morphological changes in the socket during the healing process. At T0 (day of tooth extraction), extraction socket measurements revealed statistically significant differences between the treatment and control groups in the mesio-distal (MD) and vestibulo-oral (VO) axes (

p = 0.01). On average, patients in the treatment group presented with reduced MD and VO measurements, with mean values of 5.9 ± 2.7mm and 6.0 ± 2.6mm, respectively. By contrast, the control group displayed substantially larger dimensions, with the MD and VO parameters measuring 8.0 ± 2.7mm and 8.0 ± 2.4mm, respectively. No statistically significant variation in the socket probing depth (P) was observed between the groups at baseline (T6: 10.9 ± 3.3mm; C6: 11.0 ± 3.5mm), suggesting comparable vertical dimensions of the post-extraction alveolus at baseline (

Table 4).

By day 3 post-extraction (D3), patients in the control group displayed mean values of 6.0 ± 2.4mm for the MD axis, 5.0 ± 2.1 mm for the VO axis, and 9.0 ± 3.7 mm in socket depth, corresponding to an estimated residual socket volume (RSV) of 0.4 ± 0.2. Patients in the treatment arm consistently demonstrated a trend toward improved measurements along the MD and P axes, with mean values of 4.7 ± 2.0 mm and 7.6± 2.5 mm, respectively, and a statistically significantly lower vestibulo-oral (VO) distance of 3.8 ± 1.4 mm, resulting in a residual socket volume (RSV) of 0.5 ± 0.5, with no statistically significant difference in residual socket volume between the two groups (

Table 4).

By day 7 post-extraction (D7), measurements across the three axes revealed that patients in the treatment arm had mean values of 3.5 ± 1.5 mm in the mesio-distal (MD), and 3.1 ± 1.4 mm in the vestibulo-oral (VO) dimension, and 5.8 ± 2.2 mm in probing depth (P), corresponding to a residual socket volume (RSV) of 0.3 ± 0.3. The control group exhibited mean measurements of 5.0 ± 2.1 mm (MD), 4.0 ± 2.1 mm (VO), and 6.0 ± 2.2 mm (P), with an associated RSV of 0.2 ± 0.1. At this stage of healing, the mesio-distal (MD) was the only parameter to show a statistically significant difference between cohorts (

p = 0.01) (

Table 4).

Over time, both groups showed a progressive contraction in socket dimensions, consistent with ongoing post-extraction healing. By day 14 (D14), the treatment group demonstrated mean measurements of 2.8 ± 2.1 mm in the mesio-distal (MD), and 2.0 ± 1.5 mm in the vestibulo-oral (VO) axes, and 3.7 ± 2.5 mm in probing depth, corresponding to an estimated residual socket volume (RSV) of 0.1 ± 0.1. By comparison, the control group exhibited mean values of 3.0 ± 1.3 mm (MD), 3.0 ± 1.6 mm (VO), and 3.0 ± 2.5 mm (P), corresponding to an estimated RSV of 0.04 ± 0.03. At this time point, statistically significant differences were observed in both the VO dimension (

p = 0.04) and RSV (

p = 0.01), suggesting that while alveolar contraction over time was evident in both cohorts, the extent and morphological pattern of socket closure significantly diverged between groups (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

This clinical trial studied whether a gel containing sodium hyaluronate and six synthetic amino acids glycine, L-leucine, L-proline, L-lysine, L-valine, and L-alanine could improve healing of the socket post tooth extraction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, a population frequently affected by protracted wound healing and compromised socket remodeling. A total of 43 patients with diabetes-related complications enrolled to assess the efficacy of the gel formulation in individuals at higher risk of impaired healing due to their systemic condition.

Impaired healing of the tooth socket following extraction remains a significant burden to bear for patients with type 2 diabetes, who often exhibit reduced wound healing compared to non-diabetic or prediabetic individuals [

19,

37]. Interventions are frequently complicated by swelling and infection, making the search for alternative adjunctive strategies a priority in oral surgery [

11,

19]. Even though studies in humans point to some biomaterials, particularly hyaluronic acid and its derivatives, as critical components of formulations in enhancing soft-tissue repair in diabetic patients, further research is needed to support these findings [

17,

26,

32].

This investigation was designed and conducted to evaluate the efficacy of a gel combining sodium hyaluronate with six synthetic amino acids to counteract protracted post-extraction wound healing in type 2 diabetes mellitus. A modified Landry index score was selected as primary outcome to monitor soft-tissue repair in post-tooth extraction wounds [

17].

Patients treated with the intervention achieved statistically significant higher healing scores at day 7 and day 14 compared with controls (

p < 0.001). Healing in the treatment group followed a course similar to what would normally be expected in non-diabetic individuals, whereas the control group required up to 21 days to achieve comparable scores [

19,

37]. These findings are consistent with meta-analysis and review articles that point to HA and its derivatives as promoters of soft tissue healing of diabetic ulcers in the absence of adverse events [

38,

39]. Randomized clinical trials also support the benefits of combining formulations with HA in achieving higher rates of healing in diabetic ulcers [

40,

41]. In oral surgery, studies using a split-mouth design in subjects with poorly controlled diabetes have shown that locally applying HA after tooth extraction can lead to more rapid closure as well as earlier healing compared with untreated sites [

17,

30].

Beyond HA, formulations that combine HA with amino acids also show promising outcomes in wound healing. In oral soft-tissue laser surgery, a gel containing sodium hyaluronate with glycine, L-leucine, L-proline, and L-lysine improved healing indices at day 7 compared with no treatment [

28]. A similar formulation enhanced socket healing in patients with liver failure undergoing tooth extraction [

42].

By contrast, residual socket volume (RSV), which reflects socket morphology dynamics, can diverge from soft-tissue indices, especially in diabetic sockets where remodeling dynamics and baseline morphology may vary [

8,

24,

33]. Even though both groups displayed progress in contraction profiles over time, the control group showed a greater reduction in RSV at day 14. The divergence in healing and socket contraction outcomes suggest that early soft-tissue improvement does not translate into faster socket closure, consistent with complex asynchronous soft- and hard-tissue healing trajectories [

8,

18].

Thus, the results obtained in this study show that topically applying a combination of sodium hyaluronate plus pro-collagen synthesis amino acids facilitates soft tissue healing in patients with type 2 diabetes. The formulation, even in the absence of marked volumetric advantages, while later driving tissue regeneration.

5. Conclusions

Healing index results show that the intervention group exhibited significantly better healing outcomes by days 7 and 14 compared to control. Socket dimension differences between the two groups over time were observed at individual time points across selected parameters, while socket volume contraction was significantly greater in the untreated group on day 14 only. Importantly, even though healing index results indicate a significantly faster progression of tissue repair in the treatment cohort compared to the control over time, socket morphology results suggest that far more complex dynamics are at work between socket morphology and tissue healing in post-extraction wounds.

The topical gel was well tolerated, with no adverse reactions or need for antibiotic therapy.

The results obtained in this study provide evidence supporting the efficacy of the intervention in promoting wound healing and modulating early immune responses in diabetic patients undergoing tooth extractions. Further investigations are needed to compare the efficacy of this formulation against current and alternative therapeutic approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R.; methodology, T.R. and M.B.; validation, R.P. and F. M.; formal analysis, D.C.; investigation, T.R., R.P, E.C. and B.B.; resources, I.R. and F.M.; data curation, I.R.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R., E.C. V.N. and B.B; writing—review and editing, T.R., V.N. and M.B.; visualization, V.N.; supervision, F.M. and P.G.A.; project administration, F.M.; funding acquisition, P.G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding. PROFESSIONAL DIETETICS S.p.A., Via Ciro Menotti, 1/A, 20129, Milan, Italy had no role in the study or in the preparation of the manuscript and submission of this manuscript. The APC was funded by PROFESSIONAL DIETETICS S.p.A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Turin (approval code: 0100924 on 15/09/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carme Gabernet Castelló for her editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that PROFESSIONAL DIETETICS S.p.A., Via Ciro Menotti, 1/A, 20129, Milan, Italy had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| T2DM |

Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| HA |

Hyaluronate |

References

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and Regional Diabetes Prevalence Estimates for 2019 and Projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th Edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2019, 157, 107843. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, Regional and Country-Level Diabetes Prevalence Estimates for 2021 and Projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022, 183, 109119. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Burden of Diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Prevalence to 2050: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [CrossRef]

- Ruze, R.; Liu, T.; Zou, X.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; Yin, X.; Xu, Q. Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Connections in Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Treatments. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1161521. [CrossRef]

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Long-Term Effects of Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin on Diabetes Development and Microvascular Complications over 15-Year Follow-up: The Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015, 3, 866–875. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.L.; Wyant, W.A.; Abdo Abujamra, B.; Kirsner, R.S.; Jozic, I. Diabetic Wound-Healing Science. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57, 1072. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-W.; Hung, C.-M.; Chen, W.-J.; Chen, J.-C.; Huang, W.-Y.; Lu, C.-S.; Kuo, M.-L.; Chen, S.-G. New Horizons of Macrophage Immunomodulation in the Healing of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2065. [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.I.; Sculean, A.; Graves, D.T. Diabetic Wound Healing in Soft and Hard Oral Tissues. Transl Res 2021, 236, 72–86. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Shen, X.; Li, B.; Zhu, W.; Fu, Y.; Xu, R.; Du, Y.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, H. Abnormal Macrophage Polarization Impedes the Healing of Diabetes-Associated Tooth Sockets. Bone 2021, 143, 115618. [CrossRef]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Martín-González, J.; Cintra, L.T.A. Impact of Systemic Health on Treatment Outcomes in Endodontics. Int Endod J 2023, 56 Suppl 2, 219–235. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Shen, D. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Wound Healing in Patients with Diabetes after Tooth Extraction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 949535. [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.A.; AlGhamdi, L.; AlKadi, M.; AlBeajan, N.; AlRashoudi, L.; AlHussan, M. The Burden of Diabetes, Its Oral Complications and Their Prevention and Management. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2018, 6, 1545–1553. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Haque, M. Oral Health Messiers: Diabetes Mellitus Relevance. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2021, 14, 3001–3015. [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.T.; Kaye, K.S.; Knott, C.; Nguyen, H.; Santarossa, M.; Evans, R.; Bertran, E.; Jaber, L. Diabetes and Risk of Surgical Site Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016, 37, 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Drayton, D.J.; Birch, R.J.; D’Souza-Ferrer, C.; Ayres, M.; Howell, S.J.; Ajjan, R.A. Diabetes Mellitus and Perioperative Outcomes: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Br J Anaesth 2022, 128, 817–828. [CrossRef]

- Cheisson, G.; Jacqueminet, S.; Cosson, E.; Ichai, C.; Leguerrier, A.-M.; Nicolescu-Catargi, B.; Ouattara, A.; Tauveron, I.; Valensi, P.; Benhamou, D.; et al. Perioperative Management of Adult Diabetic Patients. Preoperative Period. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2018, 37 Suppl 1, S9–S19. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, T.; Carossa, M.; Camisassa, D.; Bezzi, M.; Rivetti, G.; Nobile, V.; Pol, R. Hyaluronic Acid Treatment of Post-Extraction Tooth Socket Healing in Subjects with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2: A Randomized Split-Mouth Controlled Study. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 452. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Song, S.; Wang, S.; Duan, Y.; Zhu, W.; Song, Y. Type 2 Diabetes Affects Postextraction Socket Healing and Influences First-Stage Implant Surgery: A Study Based on Clinical and Animal Evidence. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2019, 21, 436–445. [CrossRef]

- Gadicherla, S.; Smriti, K.; Roy, S.; Pentapati, K.-C.; Rajan, J.; Walia, A. Comparison of Extraction Socket Healing in Non-Diabetic, Prediabetic, and Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2020, 12, 291–296. [CrossRef]

- Abiko, Y.; Selimovic, D. The Mechanism of Protracted Wound Healing on Oral Mucosa in Diabetes. Review. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2010, 10, 186–191. [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.R.; Lima, J.A.; Gonçalves, T.E.D.; Bastos, M.F.; Figueiredo, L.C.; Shibli, J.A.; Duarte, P.M. Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor-Kappa B Ligand/Osteoprotegerin Ratio in Sites of Chronic Periodontitis of Subjects with Poorly and Well-Controlled Type 2 Diabetes. J Periodontol 2010, 81, 1455–1465. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M.; Hu, F.B.; Marino, M.; Li, Y.; Joshipura, K.J. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and 20 Year Incidence of Periodontitis and Tooth Loss. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012, 98, 494–500. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Dipietro, L.A. Factors Affecting Wound Healing. J Dent Res 2010, 89, 219–229. [CrossRef]

- Sathyaraj, W.V.; Prabakaran, L.; Bhoopathy, J.; Dharmalingam, S.; Karthikeyan, R.; Atchudan, R. Therapeutic Efficacy of Polymeric Biomaterials in Treating Diabetic Wounds-An Upcoming Wound Healing Technology. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15, 1205. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.-Y.; Wan, X.-X.; Kambey, P.A.; Luo, Y.; Hu, X.-M.; Liu, Y.-F.; Shan, J.-Q.; Chen, Y.-W.; Xiong, K. Therapeutic Role of Growth Factors in Treating Diabetic Wound. World J Diabetes 2023, 14, 364–395. [CrossRef]

- Marin, S.; Popovic-Pejicic, S.; Radosevic-Caric, B.; Trtić, N.; Tatic, Z.; Selakovic, S. Hyaluronic Acid Treatment Outcome on the Post-Extraction Wound Healing in Patients with Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Split-Mouth Study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2020, 25, e154–e160. [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, W.; Jedaiba, W.H.; Alnami, A.M.; Hussain Baiti, L.A.; Ali Manqari, S.M.; Bhati, A.; Almarghlani, A.; Assaggaf, M. Efficacy of Hyaluronic Acid Gel and Spray in Healing of Extraction Wound: A Randomized Controlled Study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022, 26, 3444–3449. [CrossRef]

- Romeo, U.; Libotte, F.; Palaia, G.; Galanakis, A.; Gaimari, G.; Tenore, G.; Del Vecchio, A.; Polimeni, A. Oral Soft Tissue Wound Healing after Laser Surgery with or without a Pool of Amino Acids and Sodium Hyaluronate: A Randomized Clinical Study. Photomed Laser Surg 2014, 32, 10–16. [CrossRef]

- Guazzo, R.; Perissinotto, E.; Mazzoleni, S.; Ricci, S.; Peñarrocha-Oltra, D.; Sivolella, S. Effect on Wound Healing of a Topical Gel Containing Amino Acid and Sodium Hyaluronate Applied to the Alveolar Socket after Mandibular Third Molar Extraction: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Quintessence Int 2018, 49, 831–840. [CrossRef]

- Nobile, V.; Cestone, E.; Pisati, M.; Roveda, G. Amino Acids Oral Treatment for the Amelioration of Skin, Hair, and Nails Conditions: An Open-Label Study. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science Journal 2024, 12, 91–101.

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Parallel Group Randomised Trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c332. [CrossRef]

- Mozzati, M.; Gallesio, G.; di Romana, S.; Bergamasco, L.; Pol, R. Efficacy of Plasma-Rich Growth Factor in the Healing of Postextraction Sockets in Patients Affected by Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014, 72, 456–462. [CrossRef]

- Elian, N.; Cho, S.-C.; Froum, S.; Smith, R.B.; Tarnow, D.P. A Simplified Socket Classification and Repair Technique. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 2007, 19, 99–104; quiz 106.

- Bergman, M.; Abdul-Ghani, M.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Manco, M.; Sesti, G.; Fiorentino, T.V.; Ceriello, A.; Rhee, M.; Phillips, L.S.; Chung, S.; et al. Review of Methods for Detecting Glycemic Disorders. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2020, 165, 108233. [CrossRef]

- Landry, R.G.; Turnbull, R.S.; Howley, T. Effectiveness of Benzydamyne HCl in the Treatment of Periodontal Post-Surgical Patients. Res. Clin. Forum.

- Kokash, M.; Darwich, K.; Ataya, J. The Effect of Hyaluronic Acid Addition to Collagen in Reducing the Trismus and Swelling after Surgical Extraction of Impacted Lower Third Molars: A Split-Mouth, Randomized Controlled Study. Clin Oral Investig 2023, 27, 4659–4666. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Ingole, S.; Deshpande, M.; Ranadive, P.; Sharma, S.; Kazi, N.; Rajurkar, S. Influence of Platelet-Rich Fibrin on Wound Healing and Bone Regeneration after Tooth Extraction: A Clinical and Radiographic Study. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2020, 10, 385–390. [CrossRef]

- Maaz Arif, M.; Khan, S.M.; Gull, N.; Tabish, T.A.; Zia, S.; Ullah Khan, R.; Awais, S.M.; Arif Butt, M. Polymer-Based Biomaterials for Chronic Wound Management: Promises and Challenges. Int J Pharm 2021, 598, 120270. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Xie, Q.; Dai, J.; Huang, G. Effectiveness of Hyaluronic Acid and Its Derivatives on Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Felzani, G.; Spoletini, I.; Convento, A.; Di Lorenzo, B.; Rossi, P.; Miceli, M.; Rosano, G. Effect of Lysine Hyaluronate on the Healing of Decubitus Ulcers in Rehabilitation Patients. Adv Ther 2011, 28, 439–445. [CrossRef]

- Ramos Gonzalez, M.; Axler, M.R.; Kaseman, K.E.; Lobene, A.J.; Farquhar, W.B.; Witman, M.A.; Kirkman, D.L.; Lennon, S.L. Melatonin Supplementation Reduces Nighttime Blood Pressure but Does Not Affect Blood Pressure Reactivity in Normotensive Adults on a High-Sodium Diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2023, 325, R465–R473. [CrossRef]

- Cocero, N.; Ruggiero, T.; Pezzana, A.; Bezzi, M.; Carossa, S. Efficacy of Sodium Hyaluronate and Synthetic Aminoacids in Postextractive Socket in Patients with Liver Failure: Split Mouth Study. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2019, 33, 1913–1919. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).