Submitted:

30 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder that leads to elevated blood sugar levels and has become a global concern. Though there has been an increase and evolution of antidiabetic drugs and therapeutics, they fall short of the desired efficacy and are often associated with adverse effects. This study explores reduced chalcone as a scaffold to design and synthesize potential antidiabetic drugs with improved efficacy through glycosylation and supplemented by in silico evaluation. Methodology: The 3ʹ-hydroxychalcone was initially reduced to 1-phenyl-3-(3ʹ-hydroxyphenyl)propane (2), followed by direct C-glycosylation at C-4ʹ under temperature control from -78 ℃ to room temperature (RT) and afforded the C-4ʹ glucosylated 1,3-diaryl propane. The first step in the mechanism was 3ʹ-O-glycosylation, and the resultant 3ʹ-O-a,b-glucose isomer mixture was isolated at -40 ℃. NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry were used to characterise and validate compound structures. These compounds' antidiabetic potentials and drug-likeness were evaluated through integrated computational techniques. Results: The main compound (5) showed no inhibitory activity against α-glucosidase and α-amylase. However, all the compounds showed higher probable antidiabetic activities and improved drug-likeness relative to aspalathin. Their binding affinity assessment showed they are potential ‘pan-binders’ with high binding affinities to several proteins implicated in the advancement of diabetes, including AKT, AMPK, GLUT4, SGLT2, and SIRT6. Furthermore, they were observed to stabilise within the binding pocket of AKT, underscored by strong hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds resulting in protein conformational changes, thus highlighting their antidiabetic potential. Conclusion: The synthesised glucosyl chalcones could be potential lead compounds for developing novel antidiabetic compounds.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. General Information

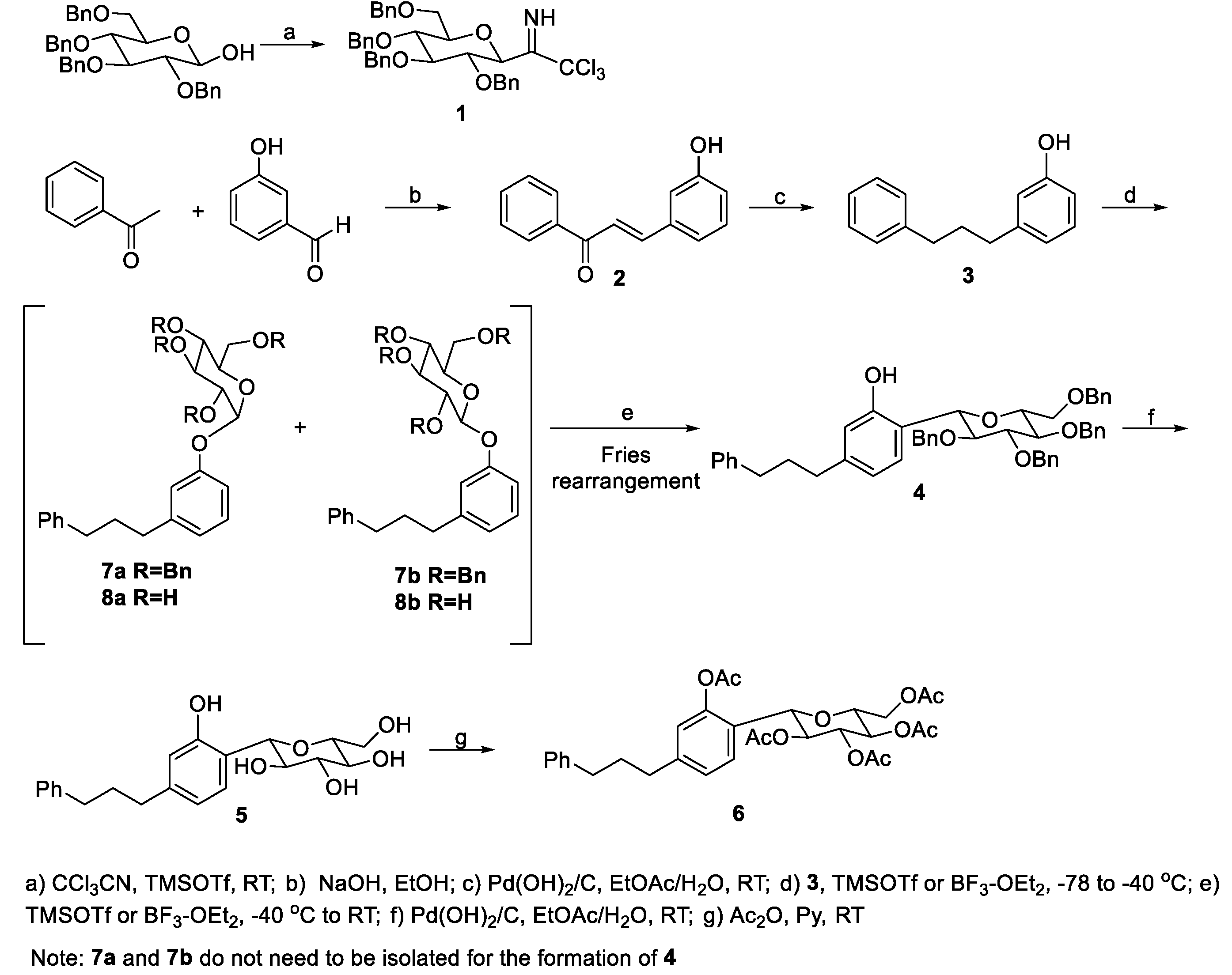

2.2. Syntheses

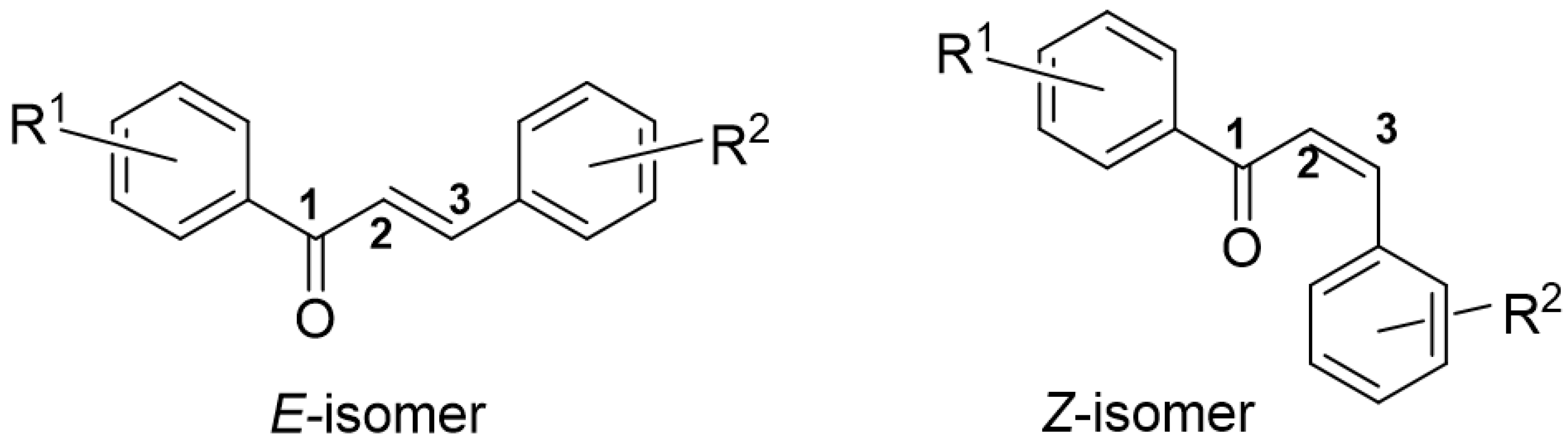

2.2.1. Synthesis of (E)-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-1-phenylprop-2-en-1-one (2)

2.2.2. Synthesis of 3-(3-phenylpropyl)phenol (3)

2.2.3. Synthesis of 1-phenyl-3-(4ʹ-C-β-D-2ʹʹʹ,3ʹʹʹ,4ʹʹʹ,6ʹʹʹ-tetra-O-benzylglucopyranosyl-3'-hydroxyphenyl)propane (4)

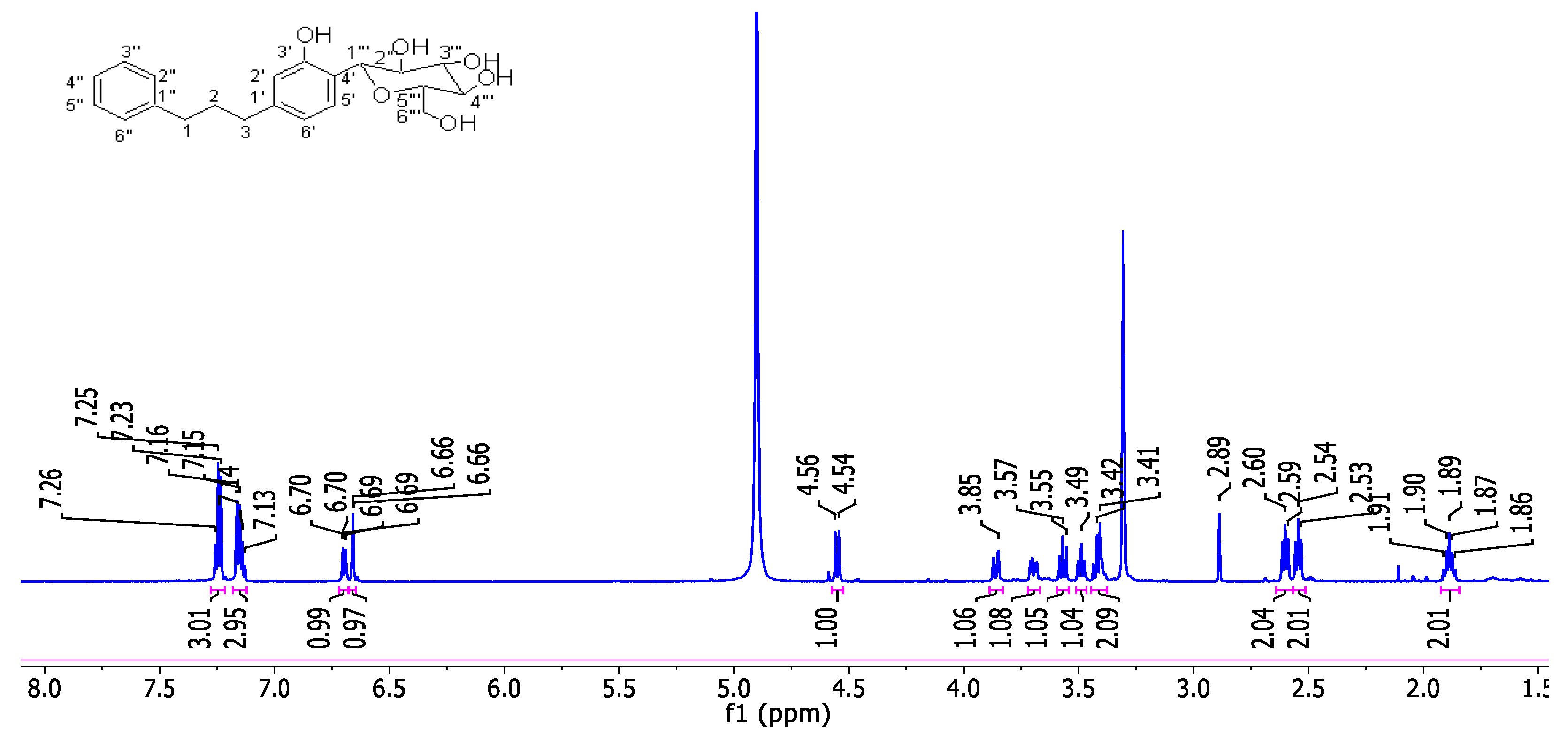

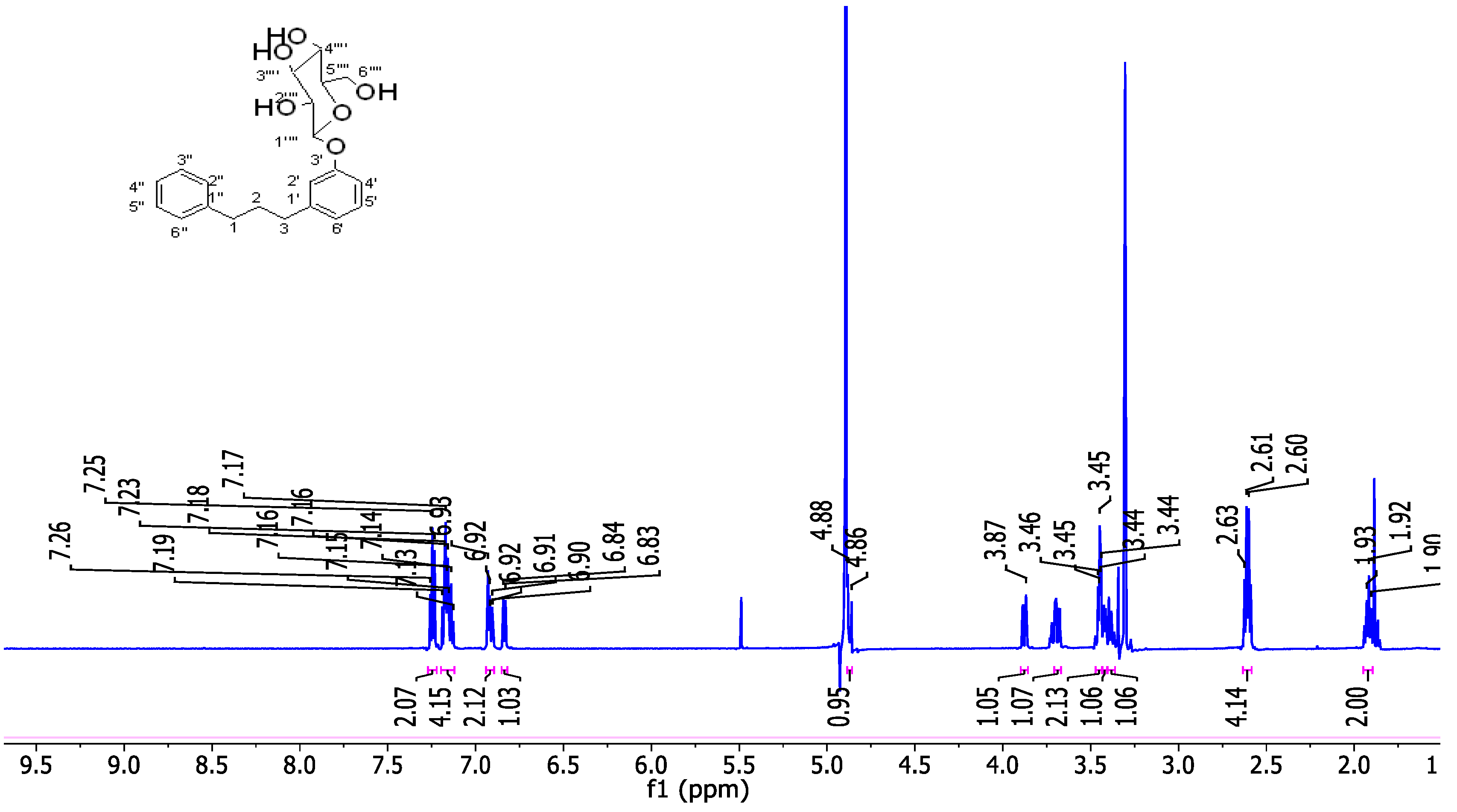

2.2.4. Synthesis of 1-phenyl-3-(4ʹ-C-β-D-2ʹʹʹ,3ʹʹʹ,4ʹʹʹ,6ʹʹʹ-tetrahydroxyglucopyranosyl-3'-hydroxyphenyl)propane (5)

2.2.5. Synthesis of 1-phenyl-3-(3ʹ-acetoxy-4ʹ-C-(2ʹʹʹ,3ʹʹʹ,4ʹʹʹ,6ʹʹʹ-tetra-O-acetyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl)propane (6)

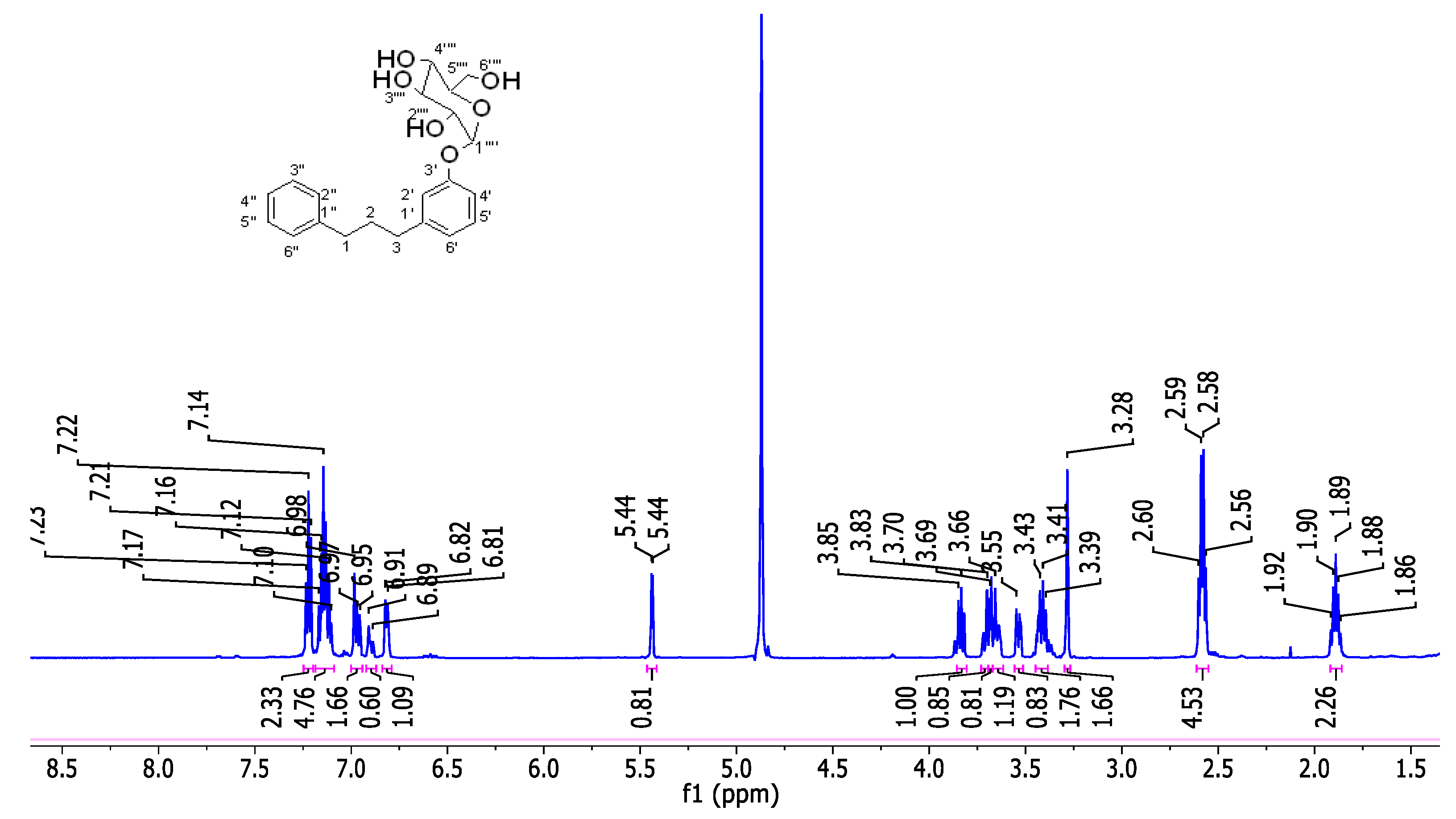

2.2.6. Synthesis of 1-phenyl-3-(3'-O-α- and b-D-2′′′,3′′′,4′′′,6′′′-tetra-O-benzylglucopyranosylphenyl)propane (7a and 7b)

2.2.7. Synthesis of 1-phenyl-3-(3'-O-α-D-2′′′,3′′′,4′′′,6′′′-tetra-hydroxyglucopyranosylphenyl)propane (8a)

2.2.8. Synthesis of 1-phenyl-3-(3'-O-β-D-2′′′,3′′′,4′′′,6′′′-tetra-hydroxyglucopyranosylphenyl)propane (8b)

2.3. In vitro Anti-Diabetic Investigation of the Compound 5

2.4. Measurement of α-Amylase Inhibition

2.5. Measurement of α-Glucosidase Inhibition

2.6. In Silico Procedure

2.7. Biological Activity Prediction

2.8. Physicochemical and Pharmacokinetics Study

2.9. Density Functional Theory

2.10. Targets Retrieval and Processing

2.11. Molecular Docking

2.12. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

3. Results and Discussion

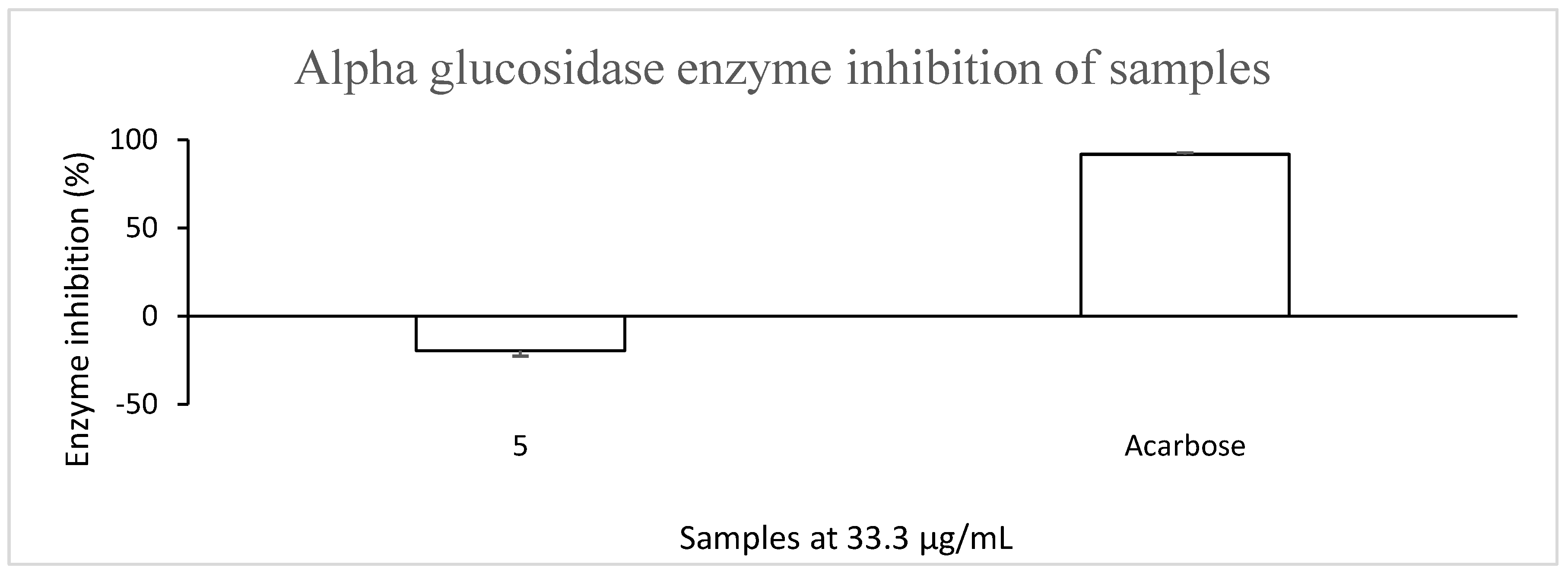

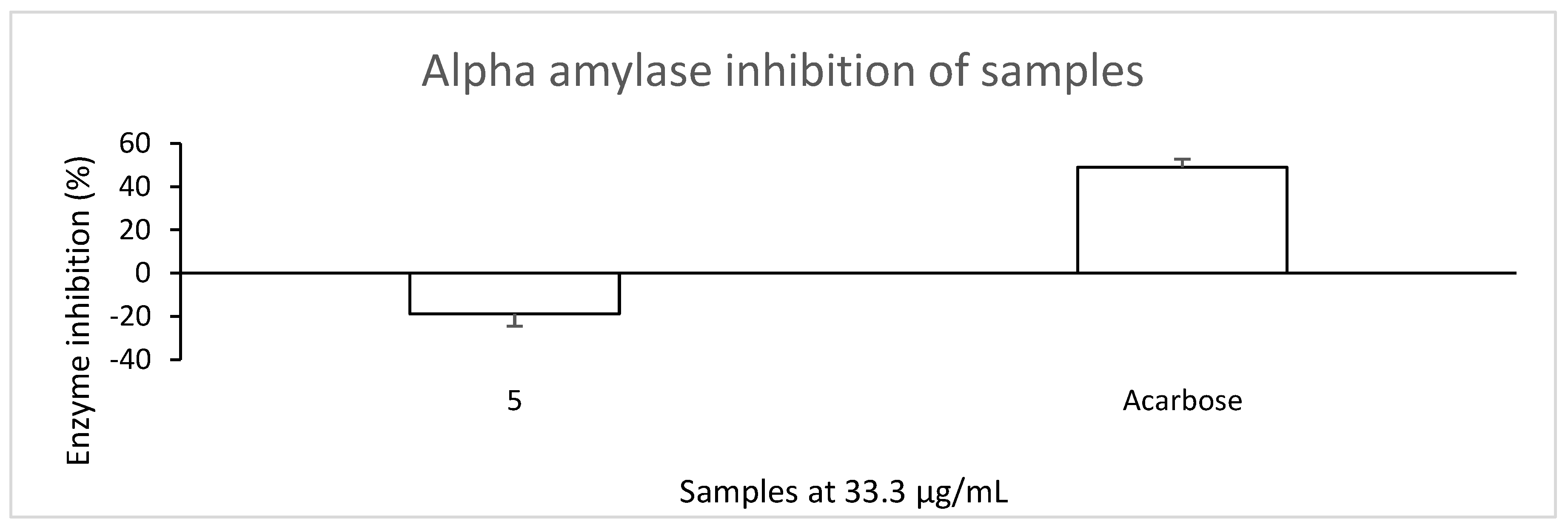

3.1. Compound 5 Showed No Inhibitory Activity Against α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase

3.2. In Silico Analysis

3.2.1. Biological Activity of Compounds

3.2.2. The Synthesised Compounds Show Relatively Better Drug-Likeness Than Aspalathin

3.2.3. The Synthesised Compounds Exhibit High GI Absorption with Good Metabolism and Low Toxicity

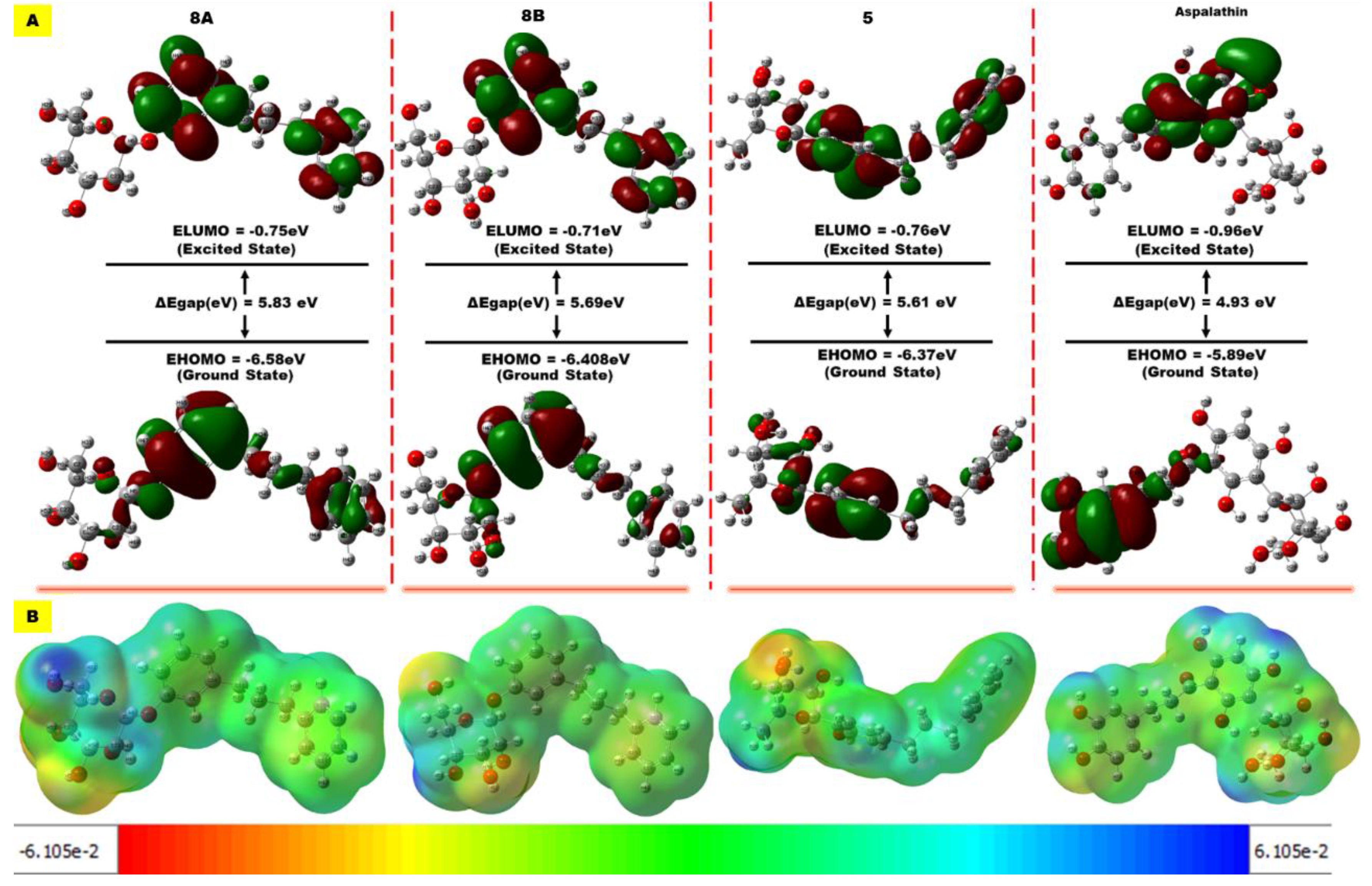

3.3. Compounds’ Reactivity

3.4. The Synthesised Compounds as Potential Pan-Binders

3.5. Compounds’ Dynamics

3.6. Compounds Stabilise and Penetrate Deeper into the Hydrophobic Regions of the AKT Binding Pocket

3.7. Compounds-Residues Interactions Profile

3.8. AKT Conformational Changes Upon Compounds’ Binding

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ipp, E., “Diabetic Retinopathy and Insulin Insufficiency: Beta Cell Replacement as a Strategy to Prevent Blindness,” Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne)., vol. 12, no. November, pp. 1–7, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.C.; et al., “Diabetic kidney disease,” Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim., vol. 1, no. 1, p. 15018, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Leon, B.M.; Maddox, T.M., “Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiology, biological mechanisms, treatment recommendations and future research.,” World J. Diabetes, vol. 6, no. 13, pp. 1246–1258, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ristow, M., “Neurodegenetive disorders associated with diabetes mellitus,” J. Mol. Med., vol. 82, no. 8, pp. 510–529, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Kulshrestha, V.; Agarwal, N., “Maternal complications in pregnancy with diabetes.,” J. Pak. Med. Assoc., vol. 66, no. 9 Suppl 1, pp. S74-7, Sep. 2016.

- Wong, M.S.; Hawthorne, W.J.; Manolios, N., “Gene therapy in diabetes.,” Self. Nonself., vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 165–175, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Rahim, F.; Arjmand, B.; Shirbandi, K.; Payab, M.; Larijani, B., “Stem cell therapy for patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of metabolomics-based risks and benefits.,” Stem cell Investig., vol. 5, p. 40, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Elnaem, M.H.; Mohamed, M.H.N.; Huri, H.Z.; Azarisman, S.M.; Elkalmi, R.M., “Statin Therapy Prescribing for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of Current Evidence and Challenges.,” J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 80–87, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Perreault, L.; Skyler, J.S.; Rosenstock, J., “Novel therapies with precision mechanisms for type 2 diabetes mellitus,” Nat. Rev. Endocrinol., vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 364–377, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, D.K.; Asati, V.; Bharti, S.K., “Chalcones and their therapeutic targets for the management of diabetes: Structural and pharmacological perspectives,” Eur. J. Med. Chem., vol. 92, pp. 839–865, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S.; Ribeiro, D.; Fernandes, E.; Freitas, M., “A Systematic Review on Anti-diabetic Properties of Chalcones.,” Curr. Med. Chem., vol. 27, no. 14, pp. 2257–2321, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Kai, G.; Yamamoto, K.; Chen, X., “Advance in dietary polyphenols as α-glucosidases inhibitors: a review on structure-activity relationship aspect.,” Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 53, no. 8, pp. 818–836, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, D.K.; Bharti, S.K.; Asati, V., “Chalcone scaffolds as anti-infective agents: structural and molecular target perspectives.,” Eur. J. Med. Chem., vol. 101, pp. 496–524, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; et al., “Concise and Scalable Synthesis of Aspalathin, a Powerful Plasma Sugar-Lowering Natural Product,” J. Nat. Prod., vol. 77, no. 3, pp. 583–588, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, A.; et al., “Syntheses and in Vitro Antiplasmodial Activity of Aminoalkylated Chalcones and Analogues,” J. Nat. Prod., vol. 78, no. 8, pp. 1848–1858, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, P.M.; de Sales, P.M.; Simeoni, L.A.; Silva, E.C.; Silveira, D.; de O, P., “Inhibitory activity of α-amylase and α-glucosidase by plant extracts from the Brazilian cerrado.,” Planta Med., vol. 78, no. 4, pp. 393–399, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Krentz, A.J.; Bailey, C.J., “Oral antidiabetic agents: current role in type 2 diabetes mellitus.,” Drugs, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 385–411, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma, C.I.; Mashele, S.S.; Akuru, E.A., “Evaluation of the in vitro ⍺-amylase inhibitory, antiglycation, and antioxidant properties of Punica granatum L. (pomegranate) fruit peel acetone extract and its effect on glucose uptake and oxidative stress in hepatocytes.,” J. Food Biochem., vol. 44, no. 5, p. e13175, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Motloung, D.M.; et al., “Synthesis, characterization, antidiabetic and antioxidative evaluation of a novel Zn(II)-gallic acid complex with multi-facet activity,” J. Pharm. Pharmacol., vol. 72, no. 10, pp. 1412–1426, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.; Stepanchikova, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V., “PASS: Prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances,” Bioinformatics, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 747–748, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Tratrat, C., “Novel Thiazole-Based Thiazolidinones as Potent Anti-infective Agents: In silico PASS and Toxicity Prediction, Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Molecular Modelling.,” Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen., vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 126–140, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.; Stepanchikova, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V., “PASS: prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances.,” Bioinformatics, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 747–748, Aug. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.A.; et al., “Prediction of the Biological Activity Spectra of Organic Compounds Using the Pass Online Web Resource,” Chem. Heterocycl. Compd., vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 444–457, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Eckert, A.O.; Schrey, A.K.; Preissner, R., “ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals,” Nucleic Acids Res., vol. 46, no. W1, pp. W257–W263, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V., “SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, no. October 2016, pp. 1–13, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Nalewajski, R.F., “Density Functional Theory BT - Perspectives in Electronic Structure Theory,” R. F. Nalewajski, Ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012, pp. 255–368.

- Frisch, M.J., “gaussian09,” http//www. gaussian. com/, 2009.

- Lutnaes, O.B.; Ruden, T.A.; Helgaker, T., “The performance of hybrid density functional theory for the calculation of indirect nuclear spin-spin coupling constants in substituted hydrocarbons.,” Magn. Reson. Chem., vol. 42 Spec no, pp. S117-27, Oct. 2004. [CrossRef]

- McCullough, E.A.; Aprà, E.; Nichols, J., “Comparison of the Becke−Lee−Yang−Parr and Becke−Perdew−Wang Exchange-Correlation Functionals for Geometries of Cyclopentadienyl−Transition Metal Complexes,” J. Phys. Chem. A, vol. 101, no. 13, pp. 2502–2508, Mar. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Fang, X.; Wei, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Tian, J., “Akt: A Potential Drug Target for Metabolic Syndrome.,” Front. Physiol., vol. 13, p. 822333, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.-Y.; Choi, H.-K.; Hwang, J.-T., “AMPK Activity: A Primary Target for Diabetes Prevention with Therapeutic Phytochemicals.,” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 11, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Kong, F.; Xu, H.; Zhu, A.; Yan, N.; Yan, C., “Cryo-EM structure of human glucose transporter GLUT4,” Nat. Commun., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 2671, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, P.; King, G.L., “Activation of protein kinase C isoforms and its impact on diabetic complications.,” Circ. Res., vol. 106, no. 8, pp. 1319–1331, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hiraizumi, M.; et al., “Transport and inhibition mechanism of the human SGLT2–MAP17 glucose transporter,” Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 159–169, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.J., “Sirtuin 6, a possible therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes.,” Arch. Pharm. Res., vol. 40, no. 12, pp. 1380–1389, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Suite, S. 2017-4 Protein Preparation Wizard. 2018.

- Shelley, J.C.; Cholleti, A.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Timlin, M.R.; Uchimaya, M., “Epik: a software program for pKaprediction and protonation state generation for drug-like molecules,” J. Comput. Aided. Mol. Des., vol. 21, no. 12, pp. 681–691, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; et al., “OPLS4: Improving Force Field Accuracy on Challenging Regimes of Chemical Space.,” J. Chem. Theory Comput., vol. 17, no. 7, pp. 4291–4300, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- 39. “Schrödinger Release 2024-2: LigPrep, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2024.”.

- Friesner, R.A.; et al., “Glide: a New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy,” J. Med. Chem., vol. 47, p. 1739, 2004.

- Shaw, D.E., “Desmond Molecular Dynamics System.” D. E. Shaw Research, New York, NY, 2021.

- Harrach, M.F.; Drossel, B., “Structure and dynamics of TIP3P, TIP4P, and TIP5P water near smooth and atomistic walls of different hydroaffinity,” J. Chem. Phys., vol. 140, no. 17, p. 174501, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Noreljaleel, A.E.M.; Wilhelm, A.; Bonnet, S.L.; van der Westhuizen, J.H., “Synthesis and Bioactivity of Reduced Chalcones Containing Sulfonamide Side Chains,” J. Nat. Prod., vol. 81, no. 1, pp. 41–48, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kakoti, B.B.; Alom, S.; Deka, K.; Halder, R.K., “AMPK pathway: an emerging target to control diabetes mellitus and its related complications.,” J. Diabetes Metab. Disord., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 441–459, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Son, M.J.; Minakawa, M.; Miura, Y.; Yagasaki, K., “Aspalathin improves hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance in obese diabetic ob/ob mice.,” Eur. J. Nutr., vol. 52, no. 6, pp. 1607–1619, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; et al., “Aspalathin-Enriched Green Rooibos Extract Reduces Hepatic Insulin Resistance by Modulating PI3K/AKT and AMPK Pathways.,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 20, no. 3, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; et al., “Aspalathin alleviates skeletal muscle insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction.,” Physiol. Res., vol. 71, no. 5, pp. 643–656, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; et al., “Aspalathin, a natural product with the potential to reverse hepatic insulin resistance by improving energy metabolism and mitochondrial respiration,” PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 5, p. e0216172, May 2019, [Online]. Available: . [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V., “Chapter 6. Probabilistic Approaches in Activity Prediction,” Chemoinformatics Approaches to Virtual Screen., pp. 182–216, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Geronikaki, A., “Recent Trends in Enzyme Inhibition and Activation in Drug Design,” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 1. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Emon, N.U.; et al., “Antidepressant, anxiolytic, antipyretic, and thrombolytic profiling of methanol extract of the aerial part of Piper nigrum: In vivo, in vitro, and in silico approaches,” Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 833–846, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lawal, B.; et al., “Pharmacoinformatics and Preclinical Studies of NSC765690 and NSC765599, Potential STAT3/CDK2/4/6 Inhibitors with Antitumor Activities against NCI60 Human Tumor Cell Lines,” Biomedicines, vol. 9, no. 1. 2021. [CrossRef]

- 53. “Computational tools for ADMET.” http://crdd.osdd.net/admet.php (accessed Dec. 08, 2021).

- Lipinski, C.A., “Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability.,” J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 235–249, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Shityakov, S.; Neuhaus, W.; Dandekar, T.; Forster, C., “Analysing molecular polar surface descriptors to predict blood-brain barrier permeation,” Int. J. Comput. Biol. Drug Des., vol. 6, pp. 146–156, 2013.

- Martin, Y.C., “How medicinal chemists learned about log P.,” J. Comput. Aided. Mol. Des., vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 809–819, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; et al., “Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and Drug Metabolism in Humans.,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 22, no. 23, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ingelman-Sundberg, M., “Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and functional diversity,” Pharmacogenomics J., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 6–13, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yang, K.; Xu, W.; Tang, W.; Li, X., “The structure and functions of P-glycoprotein.,” Curr. Med. Chem., vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 786–800, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Mumit, M.A.; Pal, T.K.; Alam, M.A.; Islam, M.A.-A.-A.-A.; Paul, S.; Sheikh, M.C., “DFT studies on vibrational and electronic spectra, HOMO-LUMO, MEP, HOMA, NBO and molecular docking analysis of benzyl-3-N-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenylmethylene)hydrazinecarbodithioate.,” J. Mol. Struct., vol. 1220, p. 128715, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.-Y.; Zhang, H.-X.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M., “Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery.,” Curr. Comput. Aided. Drug Des., vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 146–157, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.W.; Lindstrom, W.; Olson, A.J.; Belew, R.K., “Analysis of HIV wild-type and mutant structures via in silico docking against diverse ligand libraries.,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 1258–1262, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Issahaku, A.R.; et al., “Multi-dimensional structural footprint identification for the design of potential scaffolds targeting METTL3 in cancer treatment from natural compounds.,” J. Mol. Model., vol. 29, no. 4, p. 122, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

| Antidiabetic Activity | ||

| Probable Activity (Pa) | Probable Inactivity (Pi) | |

| Compound 8a | 0.769 | 0.005 |

| Compound 8b | 0.769 | 0.005 |

| Compound 5 | 0.854 | 0.004 |

| Aspalathin | 0.835 | 0.004 |

| Compound | Formula | MW (g/mol) | MLogP | LogS (Ali) (mol/L) | TPSA (A2) | Molar Refractivity | HBA | HBD | Rotatable Bonds | Lipinski Drug Likeness | |

| 8a | C21H26O6 | 374.43 | 1.87 | -3.99 | 99.38 | 99.65 | 6 | 4 | 7 | Yes:0violations | |

| 8b | C21H26O6 | 374.43 | 1.74 | -3.99 | 99.38 | 99.65 | 6 | 4 | 7 | Yes;0violations | |

| 5 | C21H26O6 | 374.43 | 1.43 | -3.80 | 110.38 | 100.15 | 6 | 5 | 6 | Yes;0violations | |

| Aspalathin | C21H24O11 | 452.41 | -0.49 | -3.73 | 208.37 | 108.66 | 11 | 9 | 6 | No; 2violations | |

| Pharmacokinetics . | Compounds | |||

| 8a | 8b | 5 | Aspalathin | |

| Distribution | ||||

| Blood Brain Barrier Permeability (log BB) | No | No | No | No |

| GI Absorption | High | High | High | Low |

| Metabolism | ||||

| P-gp substrate | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | No | No | No | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | No | No | No |

| CYP 2C9 inhibitor | No | No | No | No |

| CYP 2D6 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| CYP 3A4 inhibitor | No | No | No | No |

| Excretion | ||||

| Total Clearance (log mL/min/kg) | 0.569 | 0.197 | 0.367 | 1.16 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate | No | No | No | Yes |

| Toxicity | ||||

| Oral rat acute toxicity (LD50) (mg/kg) | 3000 | 3000 | 1000 | 2000 |

| Toxicity Class | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Compound | Parameter | |||||||||||

| EHOMO | ELUMO | Eg | I | A | χ | Ƞ | δ | ω | ω− | ω+ | Δω ± | |

| 8a | -6.58 | -0.75 | 5.83 | 6.58 | 0.75 | 3.66 | 2.91 | 0.34 | 2.30 | 7.73 | 1.67 | 9.40 |

| 8b | -6.40 | -0.71 | 5.69 | 6.40 | 0.71 | 3.55 | 2.84 | 0.35 | 2.22 | 7.51 | 1.59 | 9.10 |

| 5 | -6.37 | -0.76 | 5.61 | 6.37 | 0.76 | 3.56 | 2.80 | 0.35 | 2.26 | 7.50 | 1.66 | 9.10 |

| Aspalathin | -5.89 | -0.96 | 4.93 | 5.89 | 0.96 | 3.42 | 2.46 | 0.40 | 2.37 | 7.07 | 1.95 | 9.02 |

| Target | PDB ID | Docking Scores (Kcal/mol) | ||||

|

8a SP XP |

8b SP XP |

5 SP XP |

Aspalathin SP XP |

Control SP XP |

||

| AKT | 2GU8 | -7.55 -9.95 | -7.54 -8.66 | -8.50 -11.45 | -7.27 -14.07 | -12.66 -13.55 |

| AMPK | 6BX6 | -5.74 -7.08 | -6.14 -7.48 | -5.29 -6.64 | -6.19 -7.97 | -7.48 -8.93 |

| GLUT4 | 7WSM | -6.70 -10.69 | -8.05 -9.97 | -8.70 -12.89 | -8.22 -13.54 | -7.00 -7.87 |

| Protein Kinase C | 8UAK | -6.27 -9.11 | -6.00 -8.15 | -7.51 -8.95 | -7.08 -9.89 | -5.96 -7.47 |

| SGLT2 | 8HIN | -5.83 -7.93 | -5.22 -7.31 | -5.11 -7.61 | -6.79 -9.36 | -7.32 -9.06 |

| SIRT6(Main) | 6XVG | -5.98 -9.00 | -6.07 -9.09 | -5.61 -8.83 | -6.59 -10.66 | -8.54 -15.95 |

| SIRT6(Alosteric) | 6XVG | -6.39 -10.34 | -6.91 9.522 | -5.61 -10.74 | -6.72 -12.55 | -4.95 -3.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).