Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

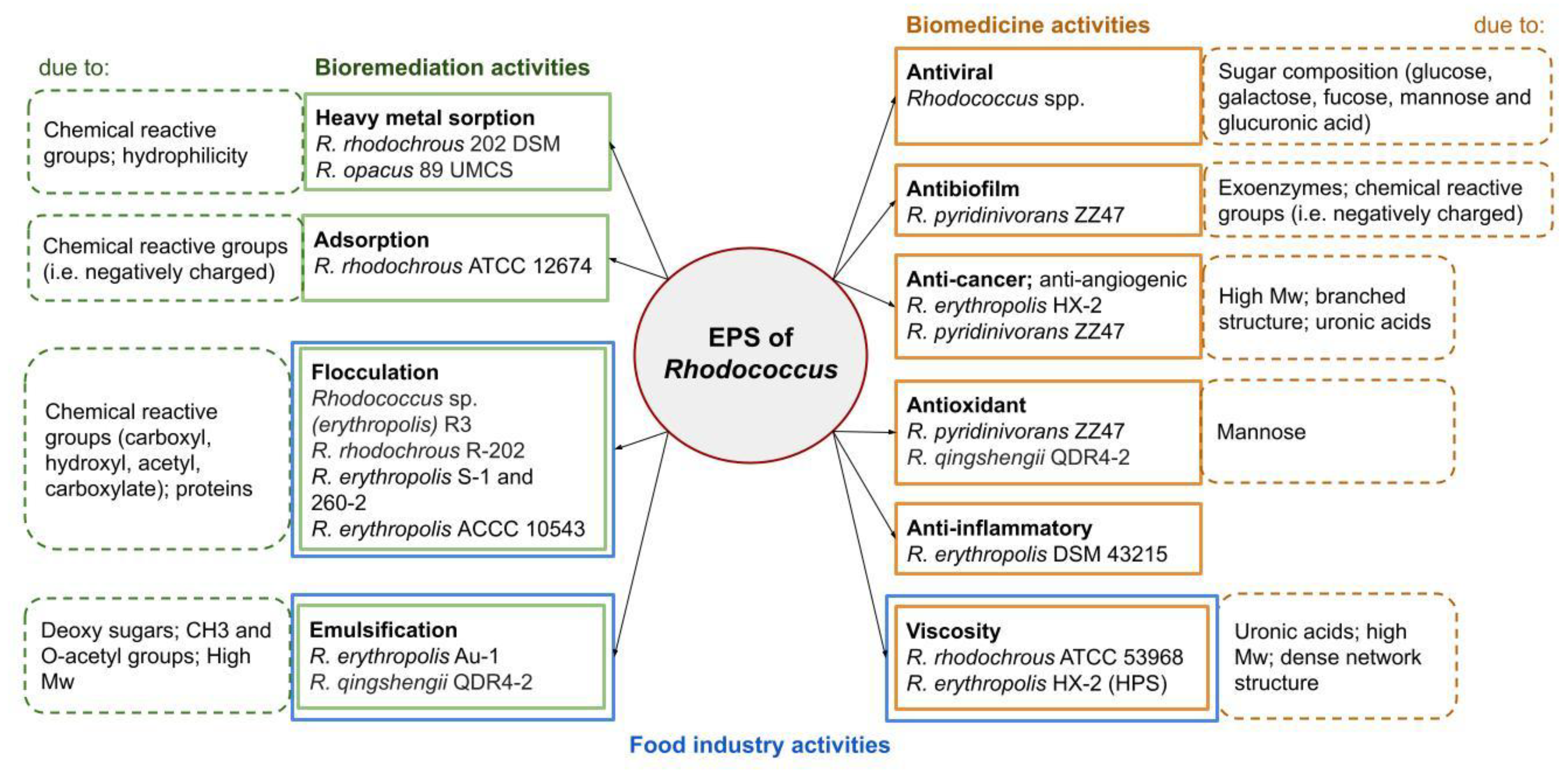

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

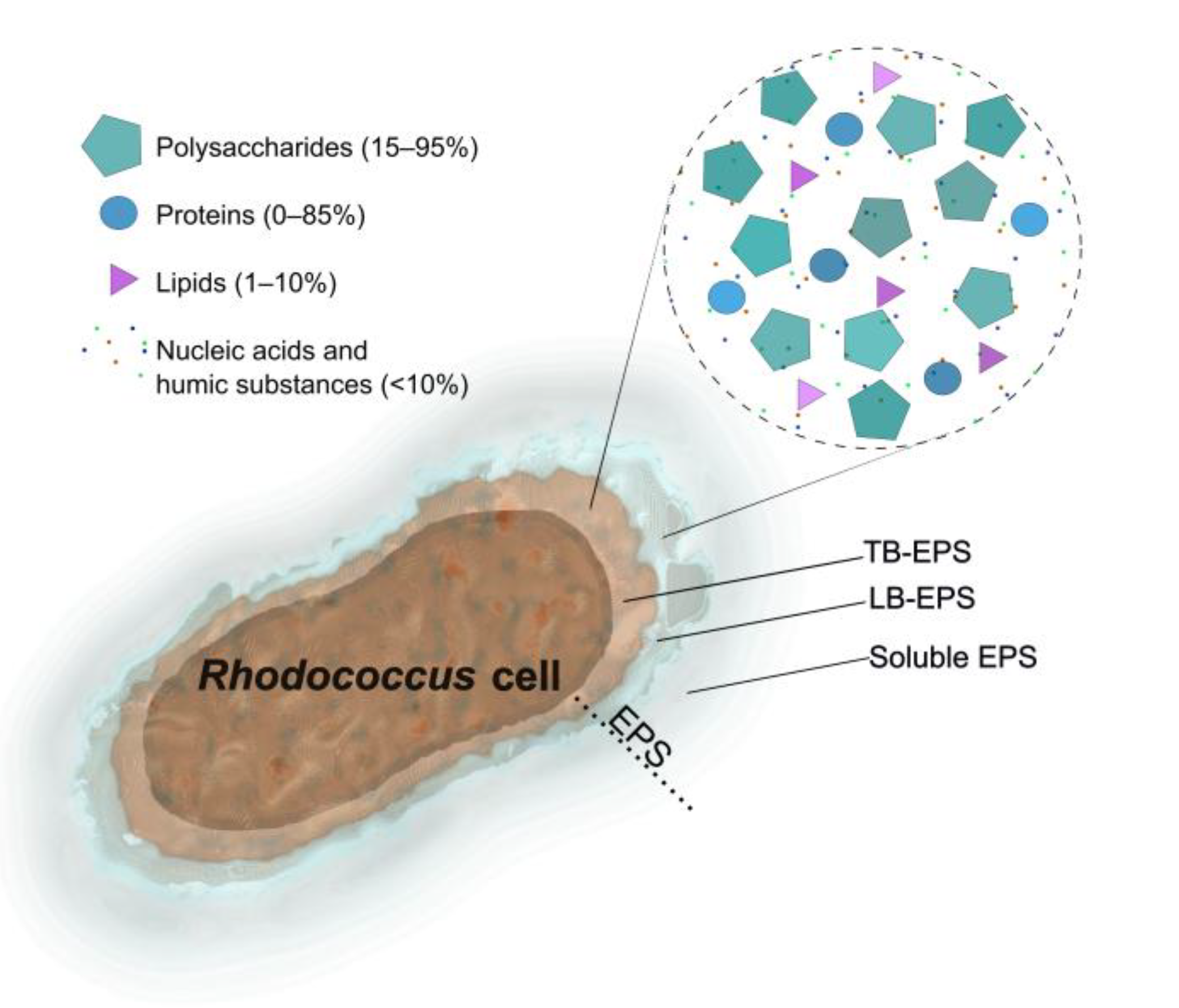

2. Chemical Composition

2.1. Carbohydrates (Exopolysaccharides)

2.2. Proteins

2.3. Lipids

2.4. Humic Substances

3. Biological Functions

4. Applications (Bioactivities)

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substances |

| TB | Tightly bound |

| LB | Loosely bound |

| DPPH | Diphenylpicrylhydrazyl |

| PCB | Polychlorinated biphenyls |

References

- Naseem, M.; Chaudhry, A. N.; Jilani, G.; Naz, F.; Alam, T.; Zhang, D.-M. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Extracellular Polymeric Substances from Divergent Microbial and Ecological Bioresources. Arab J Sci Eng, 2024, 49 (7), 9043–9052. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.-L.; Mo, S.-Y.; Ali-Saeed, R.; Zeng, H. Isolation, Structure, and Biological Activities of Exopolysaccharides from Actinomycetes: A Review. Curr Microbiol, 2025, 82 (1), 45. [CrossRef]

- Shanshoury, A.; Allam, N.; Basiouny, E.; Azab, M. Optimization of Exopolysaccharide Production by Soil Actinobacterium Streptomyces plicatus under Submerged Culture Conditions. Egypt. J. Exp. Biol. (Bot.), 2022, No. 0, 1. [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J. The Biofilm Matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2010, 8 (9), 623–633. [CrossRef]

- Krivoruchko, A.; Nurieva, D.; Luppov, V.; Kuyukina, M.; Ivshina, I. The Lipid- and Polysaccharide-Rich Extracellular Polymeric Substances of Rhodococcus Support Biofilm Formation and Protection from Toxic Hydrocarbons. Polymers, 2025, 17 (14), 1912. [CrossRef]

- Taşkaya, A.; Güvensen, N. C.; Güler, C.; Şanci, E.; Karabay, Ü. Exopolysaccharide from Rhodococcus pyridinivorans ZZ47 Strain: Evaluation of Biological Activity and Toxicity. Journal of Agricultural Production, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Atmakuri, A.; Yadav, B.; Tiwari, B.; Drogui, P.; Tyagi, R. D.; Wong, J. W. C. Nature’s Architects: A Comprehensive Review of Extracellular Polymeric Substances and Their Diverse Applications. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy, 2024, 6 (4), 529–551. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, D.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Huang, L. Purification, Characterization and Anticancer Activities of Exopolysaccharide Produced by Rhodococcus erythropolis HX-2. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 145, 646–654. [CrossRef]

- Weathers, T. S.; Higgins, C. P.; Sharp, J. O. Enhanced Biofilm Production by a Toluene-Degrading Rhodococcus Observed after Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Acids. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2015, 49 (9), 5458–5466. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.; Alves, V. D.; Reis, M. A. M. Advances in Bacterial Exopolysaccharides: From Production to Biotechnological Applications. Trends in Biotechnology, 2011, 29 (8), 388–398. [CrossRef]

- Finore, I.; Di Donato, P.; Mastascusa, V.; Nicolaus, B.; Poli, A. Fermentation Technologies for the Optimization of Marine Microbial Exopolysaccharide Production. Marine Drugs, 2014, 12 (5), 3005–3024. [CrossRef]

- More, T. T.; Yadav, J. S. S.; Yan, S.; Tyagi, R. D.; Surampalli, R. Y. Extracellular Polymeric Substances of Bacteria and Their Potential Environmental Applications. Journal of Environmental Management, 2014, 144, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Netrusov, A. I.; Liyaskina, E. V.; Kurgaeva, I. V.; Liyaskina, A. U.; Yang, G.; Revin, V. V. Exopolysaccharides Producing Bacteria: A Review. Microorganisms, 2023, 11 (6), 1541. [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Kato, W.; Ikeda, H.; Katsuyama, Y.; Ohnishi, Y.; Imoto, M. Discovery of “Heat Shock Metabolites” Produced by Thermotolerant Actinomycetes in High-Temperature Culture. J Antibiot, 2020, 73 (4), 203–210. [CrossRef]

- Ivshina, I. B.; Kuyukina, M. S.; Krivoruchko, A. V. Extremotolerant Rhodococcus as an Important Resource for Environmental Biotechnology. In Actinomycetes in Marine and Extreme Environments; CRC Press, 2024; pp 209–246.

- Peng, L.; Yang, C.; Zeng, G.; Wang, L.; Dai, C.; Long, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhong, Y. Characterization and Application of Bioflocculant Prepared by Rhodococcus erythropolis Using Sludge and Livestock Wastewater as Cheap Culture Media. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 2014, 98 (15), 6847–6858.

- Ivshina, I. B. Current Situation and Challenges of Specialized Microbial Resource Centres in Russia. Microbiology, 2012, 81 (5), 509–516. [CrossRef]

- Cappelletti, M.; Presentato, A.; Piacenza, E.; Firrincieli, A.; Turner, R. J.; Zannoni, D. Biotechnology of Rhodococcus for the Production of Valuable Compounds. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2020, 104 (20), 8567–8594. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, D.; Liu, L.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y. A Review of the Role of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) in Wastewater Treatment Systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022, 19 (19). [CrossRef]

- Iorhemen, O. T.; Hamza, R. A.; Zaghloul, M. S.; Tay, J. H. Aerobic Granular Sludge Membrane Bioreactor (AGMBR): Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) Analysis. Water research, 2019, 156, 305–314.

- Li, D.; Xi, H. Layered Extraction and Adsorption Performance of Extracellular Polymeric Substances from Activated Sludge in the Enhanced Biological Phosphorus Removal Process. Molecules, 2019, 24 (18). [CrossRef]

- Simões, M.; Simões, L. C.; Vieira, M. J. A Review of Current and Emergent Biofilm Control Strategies. LWT - Food Science and Technology, 2010, 43 (4), 573–583. [CrossRef]

- Styazhkin, K.; Artemkina, I.; Zakshevskaya, L. Exogenous Polymers of Microorganisms from Natural and Technogenic Ecosystems of Oil Production Areas. Oilfield Engineering, 2007, No. 1, 21–25. in Russian.

- Botvinko, I. Exopolysaccharides of Bacteria. Uspekhi mikrobiologii (Advances in Microbiology), 1985, 20, 79–122. in Russianin Russian .

- Urai, M.; Yoshizaki, H.; Anzai, H.; Ogihara, J.; Iwabuchi, N.; Harayama, S.; Sunairi, M.; Nakajima, M. Structural Analysis of Mucoidan, an Acidic Extracellular Polysaccharide Produced by a Pristane-Assimilating Marine Bacterium, Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4. Carbohydrate Research, 2007, 342 (7), 927–932. [CrossRef]

- Iwabuchi, N.; Sunairi, M.; Urai, M.; Itoh, C.; Anzai, H.; Nakajima, M.; Harayama, S. Extracellular Polysaccharides of Rhodococcus rhodochrous S-2 Stimulate the Degradation of Aromatic Components in Crude Oil by Indigenous Marine Bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2002, 68 (5), 2337–2343. [CrossRef]

- Urai, M.; Anzai, H.; Iwabuchi, N.; Sunairi, M.; Nakajima, M. A Novel Viscous Extracellular Polysaccharide Containing Fatty Acids from Rhodococcus rhodochrous ATCC 53968. Actinomycetologica, 2004, 18, 15–17. [CrossRef]

- Urai, M.; Yoshizaki, H.; Anzai, H.; Ogihara, J.; Iwabuchi, N.; Harayama, S.; Sunairi, M.; Nakajima, M. Structural Analysis of an Acidic, Fatty Acid Ester-Bonded Extracellular Polysaccharide Produced by a Pristane-Assimilating Marine Bacterium, Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4. Carbohydrate Research, 2007, 342 (7), 933–942. [CrossRef]

- Szcześ, A.; Czemierska, M.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A. Calcium Carbonate Formation on Mica Supported Extracellular Polymeric Substance Produced by Rhodococcus opacus. Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 2016, 242, 212–221.

- Santiso-Bellón, C.; Randazzo, W.; Carmona-Vicente, N.; Peña-Gil, N.; Cárcamo-Calvo, R.; Lopez-Navarro, S.; Navarro-Lleó, N.; Yebra, M. J.; Monedero, V.; Buesa, J.; et al. Rhodococcus spp. Interacts with Human Norovirus in Clinical Samples and Impairs Its Replication on Human Intestinal Enteroids. Gut Microbes, 2025, 17 (1), 2469716. [CrossRef]

- Güvensen, N. C.; Alper, M.; Taşkaya, A. The Evaluation of Biological Activities of Exopolysaccharide from Rhodococcus pyridinivorans in vitro. The European Journal of Research and Development, 2022, 2 (2), 491–504.

- Rapp, P.; Beck, C. H.; Wagner, F. Formation of Exopolysaccharides by Rhodococcus erythropolis and Partial Characterization of a Heteropolysaccharide of High Molecular Weight. European journal of applied microbiology and biotechnology, 1979, 7 (1), 67–78.

- Neu, T. R.; Poralla, K. An Amphiphilic Polysaccharide from an Adhesive Rhodococcus Strain. FEMS microbiology letters, 1988, 49 (3), 389–392.

- Aizawa, T.; Neilan, B. A.; Couperwhite, I.; Urai, M.; Anzai, H.; Iwabuchi, N.; Nakajima, M.; Sunairi, M. Relationship between Extracellular Polysaccharide and Benzene Tolerance of Rhodococcus sp. 33. Actinomycetologica, 2005, 19 (1), 1–6.

- Dobrowolski, R.; Szcześ, A.; Czemierska, M.; Jarosz-Wikołazka, A. Studies of Cadmium(II), Lead(II), Nickel(II), Cobalt(II) and Chromium(VI) Sorption on Extracellular Polymeric Substances Produced by Rhodococcus opacus and Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 225, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, R.; Krzyszczak, A.; Dobrzyńska, J.; Podkościelna, B.; Zięba, E.; Czemierska, M.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A.; Stefaniak, E. A. Extracellular Polymeric Substances Immobilized on Microspheres for Removal of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Environment. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 2019, 143, 202–211. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xiao, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L. Adsorption–Flocculation of Rhodococcus erythropolis on Micro-Fine Hemalitic. J. Cent. South Univ, 2013, 44, 874–879.

- Kurane, R.; Toeda, K.; Takeda, K.; Suzuki, T. Culture Conditions for Production of Microbial Flocculant by Rhodococcus erythropolis. Agricultural and biological chemistry, 1986, 50 (9), 2309–2313.

- Kurane, R.; Hatamochi, K.; Kakuno, T.; Kiyohara, M.; Hirano, M.; Taniguchi, Y. Production of a Bioflocculant by Rhodococcus erythropolis S-1 Grown on Alcohols. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 1994, 58 (2), 428–429. [CrossRef]

- Czemierska, M.; Szcześ, A.; Hołysz, L.; Wiater, A.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A. Characterisation of Exopolymer R-202 Isolated from Rhodococcus rhodochrous and Its Flocculating Properties. European Polymer Journal, 2017, 88, 21–33. [CrossRef]

- Czemierska, M.; Szcześ, A.; Pawlik, A.; Wiater, A.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A. Production and Characterisation of Exopolymer from Rhodococcus opacus. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 2016, 112, 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, C.; Zeng, G. Treatment of Swine Wastewater Using Chemically Modified Zeolite and Bioflocculant from Activated Sludge. Bioresource Technology, 2013, 143, 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Sun, X.; Luo, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.; Bao, M. Purification, Structural Characterization, Antioxidant and Emulsifying Capabilities of Exopolysaccharide Produced by Rhodococcus qingshengii QDR4-2. J Polym Environ, 2023, 31 (1), 64–80. [CrossRef]

- Urai, M.; Anzai, H.; Iwabuchi, N.; Sunairi, M.; Nakajima, M. A Novel Moisture-Absorbing Extracellular Polysaccharide from Rhodococcus rhodochrous SM-1. Actinomycetologica, 2002, 16 (2), 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Semeniuk, I.; Koretska, N.; Kochubei, V.; Lysyak, V.; Pokynbroda, T.; Karpenko, E.; Midyana, H. Biosynthesis and Characteristics of Metabolites of Rhodococcus erythropolis AU-1 STRAIN. Journal of microbiology, biotechnology and food sciences, 2022, 11 (4), e4714–e4714.

- Perry, M.; Maclean, L.; Patrauchan, M.; Vinogradov, E. The Structure of the Exocellular Polysaccharide Produced by Rhodococcus sp. RHA1. Carbohydrate research, 2007, 342 15, 2223–2229. [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Szanto, M.; Pavlov, V. Biofilm Development of the Polyethylene-Degrading Bacterium Rhodococcus ruber. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2006, 72 (2), 346–352. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Dong, J.; Sun, F.; Dong, F.; Shen, C.; Su, X. Extracellular Organic Matter-Mediated Self-Regulation of Indigenous Rhodococcus sp. Enhances PCB Biodegradation under Environmental Stress: Self-Recovery Strategy for Sustained Bioremediation. Environmental Research, 2025, 285, 122716. [CrossRef]

- Czaczyk, K.; Myszka, K. Biosynthesis of Extracellular Polymeric Substances.

- Jurášková, D.; Ribeiro, S. C.; Silva, C. C. Exopolysaccharides Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria: From Biosynthesis to Health-Promoting Properties. Foods, 2022, 11 (2), 156.

- Wilkinson, J. The Extracellular Polysaccharides of Bacteria. Bacteriological Reviews, 1958, 22 (1), 46–73.

- Neu, T. R.; Dengler, T.; Jann, B.; Poralla, K. Structural Studies of an Emulsion-Stabilizing Exopolysaccharide Produced by an Adhesive, Hydrophobic Rhodococcus Strain. Journal of General Microbiology, 1992, 138 (12), 2531–2537. [CrossRef]

- Pen, Y.; Zhang, Z. J.; Morales-García, A. L.; Mears, M.; Tarmey, D. S.; Edyvean, R. G.; Banwart, S. A.; Geoghegan, M. Effect of Extracellular Polymeric Substances on the Mechanical Properties of Rhodococcus. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 2015, 1848 (2), 518–526. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Fu, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Li, L. Characterizing the Contaminant-Adhesion of a Dibenzofuran Degrader Rhodococcus sp. Microorganisms, 2025, 13 (1), 93. [CrossRef]

- Leitch, R.; Richards, J. Structural Analysis of the Specific Capsular Polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi Serotype 1. Biochemistry and cell biology = Biochimie et biologie cellulaire, 1990, 68 4, 778–789. [CrossRef]

- Masoud, H.; Richards, J. Structural Elucidation of the Specific Capsular Polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi Serotype 7. Carbohydrate research, 1994, 252, 223–233. [CrossRef]

- Severn, W.; Richards, J. The Structure of the Specific Capsular Polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi Serotype 4. Carbohydrate research, 1999, 320 3-4, 209–222. [CrossRef]

- Severn, W.; Richards, J. Structural Analysis of the Specific Capsular Polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi Serotype 2. Carbohydrate research, 1990, 206 2, 311–332. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, I. W. Microbial Exopolysaccharides - Structural Subtleties and Their Consequences. Pure and Applied Chemistry, 1997, 69 (9), 1911–1918. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Hui, M.; Xu, X.; Su, Q.; Smets, B. F. Aerobic Biodegradation of Quinoline under Denitrifying Conditions in Membrane-Aerated Biofilm Reactor. Environmental Pollution, 2023, 326, 121507. [CrossRef]

- Moura, M. N.; Martín, M. J.; Burguillo, F. J. A Comparative Study of the Adsorption of Humic Acid, Fulvic Acid and Phenol onto Bacillus subtilis and Activated Sludge. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2007, 149 (1), 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Zhu, P.; Jiang, X.; Kim, H. Influence of Natural Organic Matter on the Deposition Kinetics of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) on Silica. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2011, 87 (1), 151–158. [CrossRef]

- Pátek, M.; Grulich, M.; Nešvera, J. Stress Response in Rhodococcus Strains. Biotechnology Advances, 2021, 53, 107698. [CrossRef]

- Hommel, R. K. Formation and Physiological Role of Biosurfactants Produced by Hydrocarbon-Utilizing Microorganisms: Biosurfactants in Hydrocarbon Utilization. Biodegradation, 1990, 1 (2), 107–119.

- Liu, Y.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Tay, J.-H. The Effects of Extracellular Polymeric Substances on the Formation and Stability of Biogranules. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 2004, 65 (2), 143–148.

- Chen, X.; Stewart, P. Role of Electrostatic Interactions in Cohesion of Bacterial Biofilms. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 2002, 59 (6), 718–720.

- Kuyukina, M. S.; Bayandina, E. A.; Kostrikina, N. A.; Sorokin, V. V.; Mulyukin, A. L.; Ivshina, I. B. Adaptations of Rhodococcus rhodochrous Biofilms to Oxidative Stress Induced by Copper(II) Oxide Nanoparticles. Langmuir, 2025, 41 (2), 1356–1367. [CrossRef]

- Mosharaf, M.; Tanvir, M.; Haque, M.; Haque, M.; Khan, M.; Molla, A.; Alam, M. Z.; Islam, M.; Talukder, M. Metal-Adapted Bacteria Isolated from Wastewaters Produce Biofilms by Expressing Proteinaceous Curli Fimbriae and Cellulose Nanofibers. Frontiers in microbiology, 2018, 9, 1334.

- Zhao, H.-M.; Hu, R.-W.; Chen, X.-X.; Chen, X.-B.; Lü, H.; Li, Y.-W.; Li, H.; Mo, C.-H.; Cai, Q.-Y.; Wong, M.-H. Biodegradation Pathway of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate by a Novel Rhodococcus pyridinivorans XB and Its Bioaugmentation for Remediation of DEHP Contaminated Soil. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 640, 1121–1131.

- Weathers, T. S.; Higgins, C. P.; Sharp, J. O. Enhanced Biofilm Production by a Toluene-Degrading Rhodococcus Observed after Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Acids. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2015, 49 (9), 5458–5466. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Rathour, R.; Singh, R.; Thakur, I. S. Production and Characterization of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) Generated by a Carbofuran Degrading Strain Cupriavidus sp. ISTL7. Bioresource Technology, 2019, 282, 417–424.

- Mor, R.; Sivan, A. Biofilm Formation and Partial Biodegradation of Polystyrene by the Actinomycete Rhodococcus ruber: Biodegradation of Polystyrene. Biodegradation, 2008, 19 (6), 851–858.

- Iwabuchi, N.; Sunairi, M.; Anzai, H.; Nakajima, M.; Harayama, S. Relationships between Colony Morphotypes and Oil Tolerance in Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2000, 66 (11), 5073–5077.

- De Carvalho, C. C.; Da Fonseca, M. M. R. Influence of Reactor Configuration on the Production of Carvone from Carveol by Whole Cells of Rhodococcus erythropolis DCL14. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 2002, 19, 377–387.

- De Carvalho, C. C.; Da Fonseca, M. M. R. Preventing Biofilm Formation: Promoting Cell Separation with Terpenes. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2007, 61 (3), 406–413.

- de Carvalho, C. C. C. R. Adaptation of Rhodococcus to Organic Solvents. In Biology of Rhodococcus; Alvarez, H. M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp 103–135. [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, C. C.; Da Cruz, A. A.; Pons, M.-N.; Pinheiro, H. M.; Cabral, J. M.; Da Fonseca, M. M. R.; Ferreira, B. S.; Fernandes, P. Mycobacterium sp., Rhodococcus erythropolis, and Pseudomonas putida Behavior in the Presence of Organic Solvents. Microscopy Research and Technique, 2004, 64 (3), 215–222.

- Huang, H.; Liu, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Xiao, H.; Lu, Z. Efficient Electrotransformation of Rhodococcus ruber YYL with Abundant Extracellular Polymeric Substances via a Cell Wall-Weakening Strategy. FEMS Microbiol Lett., 2021, 368 (9), fnab049. [CrossRef]

- Gressler, L. T.; Vargas, A. C. de; Costa, M. M. da; Sutili, F. J.; Schwab, M.; Pereira, D. I. B.; Sangioni, L. A.; Botton, S. de A. Biofilm Formation by Rhodococcus equi and Putative Association with Macrolide Resistance. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira, 2015, 35, 835–841. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Harding, W.; Willingham-Lane, J.; Hondalus, M. Conjugal Transfer of a Virulence Plasmid in the Opportunistic Intracellular Actinomycete Rhodococcus equi. Journal of Bacteriology, 2012, 194 (24), 6790–6801.

- Oguntade, A. S.; Al-Amodi, F.; Alrumayh, A.; Alobaida, M.; Bwalya, M. Anti-Angiogenesis in Cancer Therapeutics: The Magic Bullet. Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute, 2021, 33 (1), 1–11.

- d’Abzac, P.; Bordas, F.; Joussein, E.; van Hullebusch, E. D.; Lens, P. N. L.; Guibaud, G. Metal Binding Properties of Extracellular Polymeric Substances Extracted from Anaerobic Granular Sludges. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2013, 20 (7), 4509–4519.

- Sheng, G.-P.; Yu, H.-Q.; Li, X.-Y. Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) of Microbial Aggregates in Biological Wastewater Treatment Systems: A Review. Biotechnology Advances, 2010, 28 (6), 882–894.

- Whyte, L.; Slagman, S.; Pietrantonio, F.; Bourbonniere, L.; Koval, S.; Lawrence, J.; Inniss, W.; Greer, C. Physiological Adaptations Involved in Alkane Assimilation at a Low Temperature by Rhodococcus sp. Strain Q15. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1999, 65 (7), 2961–2968.

- Takeda, M.; Kurane, R.; Nakamura, I. Localization of a Biopolymer Produced by Rhodococcus erythropolis Grown on n-Pentadecane. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 1991, 55 (10), 2665–2666.

- Watkinson, R. J.; Morgan, P. Physiology of Aliphatic Hydrocarbon-Degrading Microorganisms. Biodegradation, 1990, 1 (2), 79–92.

- Wolfaardt, G. M.; Lawrence, J. R.; Headley, J. V.; Robarts, R. D.; Caldwell, D. E. Microbial Exopolymers Provide a Mechanism for Bioaccumulation of Contaminants. Microbial Ecology, 1994, 27 (3), 279–291.

- Neu, T. R.; Marshall, K. C. Bacterial Polymers: Physicochemical Aspects of Their Interactions at Interfaces. Journal of Biomaterials Applications, 1990, 5 (2), 107–133.

- Sunairi, M.; Iwabuchi, N.; Yoshizawa, Y.; Murooka, H.; Morisaki, H.; Nakajima, M. Cell-Surface Hydrophobicity and Scum Formation of Rhodococcus rhodochrous Strains with Different Colonial Morphologies. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 1997, 82 (2), 204–210.

- Crini, G. Recent Developments in Polysaccharide-Based Materials Used as Adsorbents in Wastewater Treatment. Progress in Polymer Science, 2005, 30 (1), 38–70.

- Salehizadeh, H.; Shojaosadati, S. Extracellular Biopolymeric Flocculants: Recent Trends and Biotechnological Importance. Biotechnology Advances, 2001, 19 (5), 371–385.

- Zhang, Z.-Q.; Bo, L.; others. Production and Application of a Novel Bioflocculant by Multiple-Microorganism Consortia Using Brewery Wastewater as Carbon Source. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2007, 19 (6), 667–673.

- Dhami, N. K.; Reddy, M. S.; Mukherjee, A. Biomineralization of Calcium Carbonates and Their Engineered Applications: A Review. Front. Microbiol., 2013, 4. [CrossRef]

- Braissant, O.; Cailleau, G.; Dupraz, C.; Verrecchia, E. P. Bacterially Induced Mineralization of Calcium Carbonate in Terrestrial Environments: The Role of Exopolysaccharides and Amino Acids. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 2003, 73 (3), 485–490.

- Szcześ, A.; Czemierska, M.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A.; Magierek, E.; Chibowski, E.; Hołysz, L. Extracellular Polymeric Substance of Rhodococcus opacus Bacteria Effects on Calcium Carbonate Formation. Physicochemical Problems of Mineral Processing, 2018, 54 (1), 142–150.

- Kajander, E. O.; Çiftçioglu, N. Nanobacteria: An Alternative Mechanism for Pathogenic Intra-and Extracellular Calcification and Stone Formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1998, 95 (14), 8274–8279.

| Species of Rhodococcus | Compounds name | Molecular weight (Da) | Composition | Bioactivities | References | ||||||||||

| R. hoagii CECT555, R. erythropolis CECT3013, R. rhodochrous CECT5749, R. rhodnii CECT5750, R. coprophilus CECT5751 | No data | No data | No data | Antiviral; Binding Norovirus virus -like particles |

[30] |

||||||||||

| R. pyridinivorans ZZ47 | No data | No data | No data | As antibiofilm, anti-angiogenic, antioxidant agents | [6,31] | ||||||||||

| R. erythropolis HX-2 | HPS | 1.04 × 106 | 79.24% carbohydrate, 5.2% protein and 8.45% lipid Glucose, galactose, fucose, mannose and glucuronic acid with a mass ratio of 27.29%, 24.83%, 4.79%, 26.66% and 15.84% |

As anticancer, viscosity agents |

[8] | ||||||||||

| R. rhodochrous ATCC 53968 | No data | No data | Galactose, glucose, fucose, and glucuronic acid at a molar ratio of 3: 2: 2: 2 1.3% stearic acid, 4.1% palmitic acid, 5.8% pyruvic acid |

As thickeners | [27] | ||||||||||

| R. erythropolis DSM 43215 | PLS-1 | 1.14 × 106 | Glucose and mannose in the molar ratio of 1 : 1 3.3% of proteins |

As antiinflammatory agents | [32] | ||||||||||

| Rhodococcus strain 33 | No data | 1.05 × 105 | Glucuronic acid, glucose, galactose and rhamnose in a molecular ratio of 1:1:1:2. | Adhesion; improving biodegradation | [33] | ||||||||||

| Rhodococcus strain 33 | 33 EPS; PS-33 | > 2 × 106 | D-galactose, D-glucose, D-mannose, D-glucuronic, pyruvic acids in ratio 1:1:1:1:1 | Improving hydrocarbon tolerance | [34] | ||||||||||

| R. erythropolis PR4 | FR2 | No data | d-galactose, d-glucose, d-mannose, pyruvic acid and d-glucuronic acid in ratio 1:1:1:1:1; 2.9% stearic acid and 4.3% palmitic acid | Improving hydrocarbon tolerance | [28] | ||||||||||

| R. erythropolis PR4 | FACEPS | No data | Glucose, N-acetylglucosamine, glucuronic acid, and fucose at a molar ratio of 2:1:1:1. | Improving hydrocarbon tolerance | [25] | ||||||||||

| R. rhodochrous202 DSM and R. opacus 89 UMCS | No data | No data | 52.1% and 62.7% content of CHx groups | Heavy metals (Ni(II), Pb(II), Co(II), Cd(II) and Cr(VI)) sorption | [35] | ||||||||||

| R. opacus |

BES.DM-GMA-TETA-EPS Microspheres |

No data | No data | Pb(II), Cd(II) sorption | [36] | ||||||||||

| R. erythropolis ACCC 10543 | RSF; NOC-1 | No data | Proteoglycan (glycoprotein) composed of polysaccharides (91.2%), protein (7.6%), and DNA (1.2%). | Flocculation | [16] [37] |

||||||||||

| R. erythropolis S-1 and 260-2 | No data | No data | No data | Flocculation | [38,39] | ||||||||||

| R. rhodochrous R-202 | R-202 | 1.3 × 106 | 62.86% of polysaccharide and 10.36% of protein. Mannose, glucose and galactose at the molar ratio of 12:6:1. |

Flocculation (Effective at pH around 7 and in the presence of salt solutions) |

[40] | ||||||||||

| R. opacus89 UMCS | No data | 7.6 × 105 |

64.6% polysaccharide 9.44% protein Mannose, glucose, and galactose. |

Flocculation; Binding metal cations |

[41] | ||||||||||

| R. sp. (erythropolis) R3 | No data | 3.99 × 105 | 84.6% protein and 15.2% sugar content | Flocculation | [42] | ||||||||||

| R. qingshengii QDR4-2 | QEPS | 9.450 × 105 | Mannose and glucose in a molar ratio of 81.5:18.5 | As antioxidant agent; Emulsifying | [43] | ||||||||||

| R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674 | SM-1 EPS | No data | D-galactose, D-glucose, L-fucose, and D-glucuronic acid at a molar ratio of 6: 3: 2: 4 1.2% stearic acid, 2.3% palmitic acid, and 10.3% pyruvic acid |

Absorption | [44] | ||||||||||

| R. erythropolis Au-1 | No data | No data | No data | Emulsification | [45] | ||||||||||

| Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 (NRCC 6316) | No data | No data |

hexuronic acid and neutral glycose in the approximate ratio of 1:3. D-galactose, D-glucose, L-fucose, d-glucuronic acid in ratio 1:1:1:1 |

No data | [46] | ||||||||||

| R. ruber C208 | No data | No data | Polysaccharides and proteins in ratio 2.5:1 | Adhesion | [47] | ||||||||||

| Rhodococcus sp. SJ | EOM | No data | No data | Resuscitation of nonculturable cells; Improving polychlorbiphenyls degradation |

[48] | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).