1. Introduction

The asymmetry of time remains one of the most persistent puzzles in physics, metaphysics, and the philosophy of science. Although the dynamical equations governing microscopic behavior are mostly time-reversal symmetric, the macroscopic world displays a clear directionality: processes unfold irreversibly, traces accumulate, and the past becomes fixed in a way the future does not (Clausius 1865; Boltzmann 1877; Penrose 2011). This asymmetry—grounded in the statistical tendency of entropy to increase—shapes not only thermodynamic evolution but also the conditions under which information is stored, retrieved, and made durable (Jaynes 1957a; Shannon 1948; Landauer 1961). Lindsay (1959, pp. 383–84), in one of the earliest attempts to link entropy with normativity, noted that irreversibility might illuminate moral and existential questions as well.

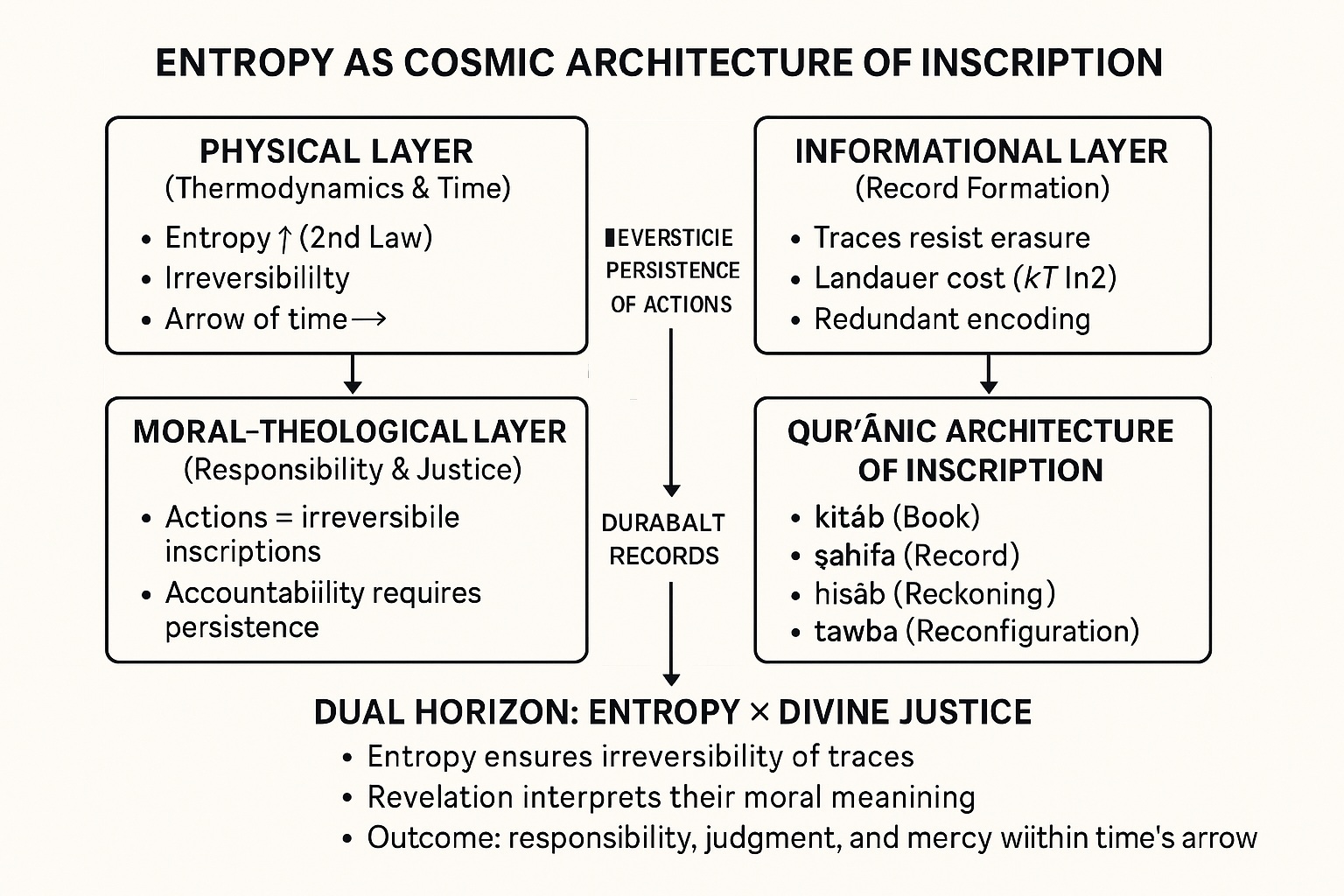

Against this backdrop, the present article develops an interdisciplinary framework that treats entropy not as a metaphysical essence but as a structural constraint—a set of physical conditions that predispose records to form, persist, and resist erasure. While the account remains fully naturalistic on the physical side, this structural environment offers a conceptual scaffolding for reflecting on moral responsibility within a Qurʾānic horizon. Islamic scripture depicts the cosmos as morally archived: deeds are written (kitāb), enumerated (aḥṣaynāhu), and made publicly accessible in an eschatological horizon (Q 36:12; Q 45:29; Q 17:14). Without collapsing scientific explanation into theological meaning, the study proposes that physical irreversibility—which enables the persistence of records—can be set in analogical dialogue with Qurʾānic notions of inscription and accountability.

Methodological Clarifications:This study does not claim an identity between thermodynamic entropy and Qurʾānic metaphysical categories. Its interpretive strategy is instead:

Analogical: drawing structural parallels without reducing one domain to the other.

Operational: using entropy to describe the physical constraints that govern the formation and persistence of records, not as a moral agent.

Non-reductive: upholding that normative authority in Islam derives from revelation rather than from physics.

These methodological boundaries preserve conceptual clarity. Physical laws do not generate moral “oughts”; yet the temporal structure they describe—particularly irreversibility—helps illuminate how moral inscriptions persist and why accountability presupposes a world in which traces cannot be readily erased.

2. Conceptual Framework

This study employs an interdisciplinary framework that places thermodynamics, information theory, and Qurʾānic metaphysics in structured dialogue without collapsing their explanatory boundaries. The aim is not to derive theology from physics or to naturalize revelation, but to explore how the structural features of entropy—irreversibility, trace persistence, and the energetic cost of information—create a conceptual environment in which moral inscription and accountability become intelligible (Clausius 1865; Penrose 2011; Jaynes 1957a; Lindsay 1959).

The methodology is both analogical and operational (McMullin 1985; Barbour 1997). Analogical reasoning allows the identification of structural resonances without implying metaphysical identity or suggesting that scientific findings confirm scripture (Guessoum 2011; Rahman 1958). Operationally, concepts such as entropy, work, redundancy, and the energetic cost of erasure (Shannon 1948; Landauer 1961; Zurek 2009) clarify how records form, endure, and resist deletion. Throughout, the framework preserves theological autonomy: Qurʾānic notions of record, judgment, and accountability derive their authority from revelation, not from physical mechanisms (Nasr 2006). Consequently, this work neither advances iʿjāz al-Qurʾān claims nor engages in scientific apologetics; physics and revelation remain distinct yet structurally resonant domains.

Thermodynamic irreversibility renders macroscopic processes effectively one-directional (Jaynes 1957b; Price 1996). Interactions produce informational residues that become practically impossible to erase once they are widely dispersed. Shannon entropy quantifies uncertainty, Landauer’s principle establishes the energetic cost of erasure, and Zurek’s theory of environmental “witnessing” explains the stability of certain information over time. Together, these insights demonstrate that the universe inherently favors the persistence of traces.

Qurʾānic descriptions of inscription—including kitāb, ṣaḥīfa, istinsākh, and ḥisāb—present a metaphysics in which deeds are preserved within divine knowledge (Rahman 1958; Izutsu 2002). Within the analogical framework developed here, these motifs correspond—structurally, rather than substantively—to the physical logic of persistent records. Entropy explains why traces endure; revelation explains why they matter.

3. The Ontological Status of Entropy: Physical Law or Universal Principle?

The ontological status of entropy has long occupied a contested space in physics and philosophy. Although commonly introduced as a quantitative measure of disorder, uncertainty, or the multiplicity of microstates, these descriptions do not resolve whether entropy is a physical property, an epistemic tool, a statistical artifact, or a structural feature of the world itself (Jaynes 1957a; Callender 2011). This ambiguity becomes especially significant when entropy is used to explain the arrow of time or invoked in broader metaphysical discussions.

Two major interpretive traditions define contemporary debates.

The first treats entropy as an objective physical magnitude grounded in the statistical behavior of matter. On this view, entropy reflects the vastly larger volume of high-probability macrostates in phase space, toward which systems naturally evolve (Boltzmann 1877; Lebowitz 1993). Penrose (2011) extends this by arguing that entropy also possesses a geometric and gravitational dimension tied to the universe’s extraordinarily low-entropy initial state. These accounts present entropy as a real, mind-independent feature of the cosmos.

The second tradition approaches entropy epistemically, interpreting it as a measure of missing information relative to an observer’s coarse-graining (Shannon 1948; Jaynes 1957b). Here, entropy does not describe nature as it is, but the limits of what can be known under informational constraints. Entropy increase, on this reading, reflects not metaphysical directionality but the collapse of accessible microstate distinctions as systems evolve, forcing descriptions to be averaged over larger ensembles (Earman 2006).

Yet neither interpretation alone captures entropy’s full role in shaping temporal structure. A purely physical account struggles to justify why coarse-graining is indispensable, whereas an entirely epistemic view fails to explain why entropy rises so uniformly across systems, regardless of human knowledge. This tension motivates recent structural or emergentist views in which entropy is neither wholly objective nor wholly subjective, but a relational feature that arises from the interaction between microscopic dynamics and macroscopic organization (Wallace 2010; Frigg & Werndl 2019).

In this study, entropy is treated as a structural-physical condition that enables key aspects of temporal experience: irreversibility, the persistence of traces, and the nontrivial energetic cost of erasure (Landauer 1961; Bennett 2003). Entropy is not taken to be a metaphysical principle or a fundamental substance, but a constraint emerging from the statistical behavior of complex systems. This non-essentialist interpretation aligns with viewing entropy as a physical–informational descriptor of how the universe evolves, not an explanation of why it exists or what purpose it serves.

This approach avoids two common pitfalls.

First, it does not attribute moral or teleological value to entropy. Entropy neither guides history nor evaluates actions; it simply shapes the physical landscape in which irreversible processes occur.Second, it avoids reducing moral accountability to thermodynamic properties. Entropy provides the conditions under which traces endure, but the meaning of those traces belongs to normative and theological reasoning.

Accordingly, entropy functions neither as an ontological foundation for morality nor as an explanatory rival to revelation. Instead, it offers a naturalized account of why the world is temporally asymmetric and why the past leaves persistent residues. These structural features make possible a conceptual dialogue with Qurʾānic motifs of inscription and accountability without erasing the boundary between physical law and theological meaning. In this view, entropy is a structural feature of created order, not a metaphysical or moral principle.

4. Record, Information, and Divine Justice: The Entropic Logic of the Book of Deeds

Entropy is not merely a measure of physical disorder; it expresses irreversibility, the durability of traces, and the embedding of events into the informational fabric of the universe. In thermodynamics, every transformation—however small—produces a residue of practically irretrievable change (Clausius 1865). Motions, intentions, and actions leave persistent informational imprints (Clausius 1865; Shannon 1948). This study draws on these scientific insights to illuminate how entropy’s structural features clarify the persistence of records, without collapsing scientific explanation into theological meaning.

From this standpoint, entropy functions as a mechanism of universal inscription. The Qurʾān repeatedly invokes kitāb (Book), ṣaḥīfa (Register), and istinsākh (precise transcription), forming an architecture of divine record-keeping. “This is Our record that tells the truth about you: We have been recording everything you do” (Q 45:29). The imagery suggests not only moral surveillance but a structured memory—conceptually comparable, as an intellectual analogy, to archival systems or probabilistic encoding models (Shannon 1948).

Thermodynamically, every action induces irreversible reconfigurations. Just as a plastically deformed metal cannot return to its prior microstate, human actions inscribe effectively irreversible marks upon spacetime. These traces are not figurative; they consist of correlations in matter and fields that are extraordinarily difficult to erase (Clausius 1865; Penrose 2005). This ontological framing resonates with an Islamic hierarchy in which ʿilm (knowledge) is not merely epistemic but possesses ontological and moral significance (Bakar 1998).

Information theory further sharpens this conceptual picture. For Shannon (1948), entropy quantifies average unpredictability rather than semantic meaning (Jaynes 1957a, 1957b). A record is a retrievable, integrity-protected correlation with a past event. Two features make such records durable under noise: integrity (resistance to tampering) and redundancy (multiple, independent attestations). In physics and biology, redundancy enhances survivability; in quantum systems, environments can act as many-copy “witnesses” to system states (Zurek 2009). In the Qurʾānic register, a similar grammar emerges: shahāda (witnessing), kataba (inscription), and moral consequence are intertwined so that what is known is also written, enumerated, and preserved. Angelic scribes, communal memory, and even bodily testimony (Q 50:17–18; Q 36:65) function as redundant channels of attestation that increase the recoverability of deeds.

Within this conceptual schema, divine justice depends on informational integrity. Judgment becomes meaningful only if deeds are reliably recorded. Entropy reinforces this condition by making erasure costly and full reversals overwhelmingly unlikely (Landauer 1961). The Qurʾānic ṣaḥīfa thus resonates with the thermodynamic necessity of trace persistence: “Whoever does good benefits his own soul, and whoever does evil harms only himself: your Lord is never unjust to His creatures” (Q 41:46).

A ḥadīth qudsī narrated by Abū Dharr deepens this moral architecture. The narration emphasizes divine justice and mercy through a sweeping address to humanity:

“O My servants! I have forbidden oppression for Myself and made it forbidden among you… O My servants, you sin by night and by day, and I forgive all sins… O My servants, were the first of you and the last of you… to ask of Me and I gave everyone what he requested, that would not decrease what I have any more than a needle decreases the sea… O My servants, it is but your deeds that I record for you and then recompense you for…”

(Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2577a).

The image of a needle entering the sea highlights two structural points. First, divine governance is non-rivalrous: nothing given, recorded, or forgiven diminishes God’s power—unlike finite archives that incur energetic costs for writing or erasing. Second, creaturely actions disperse their consequences, just as physical processes broadcast energy and correlations into their environments, aligning with the second law of thermodynamics (Clausius 1865). Thus, the ḥadīth presents a world in which human deeds have distributive consequences while God’s sovereignty remains unaffected.

A parallel emerges in Penrose’s cosmology: the universe’s extremely low-entropy initial state required “needle-like precision” within an “ocean” of possible configurations (Penrose 2011). Although not theological, the metaphor echoes the ḥadīth’s portrayal of divine infinitude. A needle’s immersion in the ocean mirrors the negligible impact of human actions on God’s boundless sovereignty, while the entropic dispersal of deeds parallels the universe’s irreversible evolution.

This framing challenges moral theories that treat ethics as detached from natural law. By contrast, the Qurʾānic paradigm embeds ethics within the temporal and physical architecture of the world. The irreversible inscription of deeds becomes both an ontological structure and a moral condition. Entropy does not undermine moral order; it provides the very conditions that make ordered moral life possible.

Actions do not dissolve into oblivion; they are thermodynamically and metaphysically retained. Within this framework, divine justice requires that nothing be lost and everything be accounted for. Entropy thus becomes not a descent into disorder but the operative logic of enduring record. On this foundation, §5 examines tawba (repentance) as the practice through which the record persists while its moral valence is re-inscribed.

5. Sin, Repentance, and the Thermodynamics of Moral Irreversibility

The second law of thermodynamics is not merely an index of disorder; it encodes temporal asymmetry and the pervasive tendency toward irreversibility. Every physical process—however minute—produces dissipative by-products and reconfigures degrees of freedom in ways that are exceedingly unlikely to reverse without external work. Entropy therefore establishes the background against which actions, whether physical or moral, leave operationally persistent traces (Clausius 1865; Shannon 1948; Price 1996; Gołosz 2021). For broader implications of temporal asymmetry, see §8.

Within the Qurʾānic horizon, this irreversibility converges with themes of exposure, reckoning, and eschatological disclosure. “Read your record; today your own soul suffices as an accountant against you” (Q 17:14). “We have removed your veil, and your sight today is sharp” (Q 50:22). Revelation portrays not merely a ledger of deeds but an ontological unveiling. The environment itself becomes a witness: “When the earth is shaken… and it throws out what is within it and becomes empty… on that Day it will report its news” (Q 99:1–4). Similarly, “It casts out what is in it and becomes void” (Q 84:4). In these passages, the world is not a passive container but an active, truth-telling medium. What actions broadcast into their surroundings eventually returns as testimony.

From a thermodynamic perspective, every action propagates correlations into its environment. Just as a plastically deformed metal cannot spontaneously regain its former microstate, human actions alter the informational environment irreversibly. Such traces are coarse-grained features of fields and matter, resistant to perfect erasure (Clausius 1865; Penrose 2005; Zee 2010). Zurek (2003, 2009) shows how decoherence stabilizes such residues across environmental degrees of freedom, while Zee (2010) outlines the cosmological and quantum-field-theoretic structures that underwrite their persistence. These accounts parallel the Islamic conception of ʿilm, in which knowledge possesses ontological and moral weight and is inseparable from inscription, witnessing, and accountability (Bakar 1998).

For judgment to be meaningful, deeds must be reliably recorded. Entropy provides the natural background for this condition by making erasure costly and full reversibility practically unattainable. Within this nexus of witnessing, inscription, and consequence, ʿilm becomes that which is seen, written, enumerated, and preserved. The Qurʾānic ṣaḥīfa operates within this grammar of persistence, mapping an ontological landscape in which the endurance of traces makes accountability intelligible.

Repentance (tawba) enters this picture not as a negation of the trace but as a transformation of its meaning. “Whoever commits a sin or wrongs himself, then seeks God’s forgiveness will find God Forgiving and Merciful” (Q 4:110). Tawba “re-indexes” the moral significance of the event: the act remains part of the agent’s temporal history, but its evaluative meaning is altered. A physical analogy clarifies this dynamic: a river carved by erosion continues along its channel even if its flow is later redirected through intentional intervention. In the moral realm, the redirection is not mechanical but divine—mercy reshapes the evaluative weight of what remains inscribed.

The Qurʾān further states, “God erases what He wills and confirms what He wills; and with Him is the Mother of the Book” (Q 13:39). Erasure (maḥw) and confirmation (ithbāt) thus coexist within the same metaphysical architecture. The verse indicates that permanence of record and the possibility of merciful reinterpretation are not opposites but complementary dimensions of divine order. A thermodynamic parallel illuminates the distinction: entropy in a heat engine increases irreversibly with each cycle, rendering some energy unavailable for future work, yet an external intervention—a reset mechanism—can redirect the system’s outcome. Tawba functions analogously at the moral level: the trace persists, but its narrative significance is redefined by divine action.

Within this composite vision, sin is not an isolated event but a modification of one’s moral trajectory. Repentance becomes the reconfiguration of that trajectory within a universe where traces endure yet meanings can shift. Entropy frames a world in which actions leave indelible marks; Qurʾānic theology reveals that these marks, though permanent as traces, are not irrevocable in meaning. The created order preserves the history of deeds, while the divine order determines their value.

6. Time, Entropy, and the Apocalypse: A Scenario of Cosmic Closure

The second law of thermodynamics—asserting that entropy in isolated systems tends to increase—expresses not only a physical principle but also a macroscopic trajectory for the universe. Interpreted as the progressive dissipation of usable energy, entropy implies a cosmic evolution toward thermodynamic equilibrium, the so-called “heat death” (Clausius 1865; Price 1996; Penrose 2011; Gołosz 2021). At this limit, gradients flatten, complexity wanes, and no further work can be extracted. The universe approaches a horizon of physical stillness (Penrose 2005, 2011; Rovelli 2018). The Qurʾānic depiction—“when the earth is spread out and casts out what is in it, and becomes empty” (Q 84:3–4)—bears symbolic resonance with this entropic horizon.

The scientific projection of cosmic dissolution finds a conceptual parallel in the Qurʾānic eschatological vision. Yawm al-Qiyāmah is not merely a moment of judgment; it is a rupture in cosmic order. “The Trumpet will be sounded, and everyone in the heavens and the earth will be struck down unconscious… then it will be sounded again, and they will be standing and looking on” (Q 39:68). Likewise, “the sky will be torn apart, for it will be frail that Day” (Q 69:16). These passages evoke an irreversible collapse of the universe’s current structure—a motif conceptually akin to the entropic unraveling described in cosmology (Penrose 2011; Mikki 2021).

A further speculative bridge emerges in Penrose’s Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC). In this model, the thermodynamically saturated end of one aeon becomes, under conformal rescaling, the extraordinarily low-entropy initial condition for the next (Penrose 2011, 2014). When read alongside the Qurʾānic proclamation, “On that Day the earth will be changed to another earth, and so will the heavens…” (Q 14:48), and in light of Qurʾānic themes of renewal (Q 36:12; Q 103:1–3), CCC suggests a pattern in which dissolution gives way to regeneration. Entropy becomes a portal of transformation rather than a terminal boundary—like a cosmic clock that, upon reaching its maximal extent, is reset to begin a new cycle (cf. Eckstein 2023). Though empirical validation remains open, such cosmological proposals offer conceptual tools for thinking about renewal after collapse.

This convergence reframes entropy’s apparent finality. Rather than sheer cessation, entropy marks a threshold. The Qurʾānic perspective interprets cosmic dissolution as a phase within divine order: a transition from this temporal world to another ontological regime—“Every soul will taste death; then you will be returned to Us” (Q 29:57). Collapse is not regression but fulfilled directionality (Murphy 1991; Peacocke 1993; Russell 1984). The eschaton also highlights the agentive character of cosmic order: “On that Day, eight will bear your Lord’s Throne above them” (Q 69:17).

Within this frame, entropy is not merely energy dispersal but a script of dissolution written into the fabric of the cosmos. The final breakdown of form can be theologically read as an act of divine authorship. Penrose underscores that the smooth, low-entropy boundary conditions necessary for a new aeon are not accidental; they constitute the very possibility of subsequent order (Penrose 2011; Zee 2010). Zurek (2003, 2009) details how decoherence stabilizes informational traces, while Zee (2010) provides the quantum-field-theoretic and cosmological context through which large-scale structure dissipates and reforms.

Appeals to a “new aeon” belong to speculative cyclic cosmologies (e.g., Penrose 2011). They do not derive theology from physics but provide conceptual scaffolding for imagining how renewal might follow dissolution. Within this horizon, the apocalypse is not a negation of natural law but its culmination: entropy gathers transformations into a single trajectory that can be read as divine orchestration. A parallel appears in the Carnot cycle, where each thermodynamic loop dissipates energy irreversibly, yet an external reset—analogous to divine intervention—initiates a new cycle. This alignment between physical cycles of decay and renewal and the Qurʾānic vision of cosmic rebirth (Peacocke 1993; Polkinghorne 2006) illustrates how entropy and eschatology can illuminate one another without collapsing their explanatory domains.

7. The Limits of Thermodynamics and Metaphysical Horizons

The second law of thermodynamics—asserting that entropy in isolated systems tends to increase—stands among the most secure principles of modern science. It governs the dissipation of energy, the transformation of work, and the progressive unraveling of structure. Yet from a metaphysical standpoint, the law also reveals its limits. Thermodynamics describes the directional behavior of physical processes with extraordinary success; it does not explain why this behavior is unidirectional, what the ontological meaning of temporal directionality might be, or what mode of being is implied by the irreversible inscription of events. These questions lie beyond the domain of physics and belong instead to ontology, epistemology, and phenomenology (Clausius 1865; Shannon 1948; Eddington 1929; Prigogine 1980; Penrose 2011).

Classical Newtonian mechanics imagined the universe as a deterministic system in which complete knowledge of initial conditions would, in principle, allow prediction of the entire future. Microscopic dynamics were time-reversal symmetric; causality was linear; time appeared fundamentally neutral. This picture deeply influenced rationalist moral theories—most prominently Kant’s conception of a moral law grounded in the autonomy of practical reason rather than in the fabric of the natural world (Kant (1785) 1998; (1788) 2002). On such a view, moral obligation stands wholly independent of temporal or physical structure.

Entropy disrupts this neutrality. Real processes are irreversible; they leave behind gradients of dissipation and structural residues that mark the passage of time. These residues are not incidental inefficiencies but ontological traces encoding the asymmetry of becoming. In relativity, a worldline may appear as a clean geometric curve through spacetime, yet every orbit generates frictional losses, heat, and molecular disorder. A projectile’s path is not merely a trajectory; it carries shock waves, microstructural deformation, and a thermodynamic signature of its history. Such hidden costs form the informational imprint of physical events.

Within this enlarged horizon, entropy functions as a metaphysical ledger. Each irreversible process represents a transition from potentiality to actuality. Once a configuration occurs, it cannot be undone—not in form, not in energy distribution, and not in moral consequence. Entropy is therefore not simply decay; it marks the stabilization and actualization of possibility.

This reading resonates with Islamic metaphysics. The concepts of qadar (destiny) and qaḍāʾ (divine decree) do not reduce causality to mechanical necessity; they articulate a world in which events unfold by divine enactment, not by autonomous material force. Al-Ghazālī held that what we call “causes” are habitual correlations sustained by God’s continuous creative act (ʿādah) (al-Ghazālī 2000). No necessary connection binds causes to effects; the contingency of all things reveals their ongoing dependence on divine will.

Entropy reinforces this insight. A universe tending toward dissipation and eventual extinction cannot sustain itself independently. Its structures persist only moment by moment. This mirrors the Islamic doctrine of imkāniyya (ontological contingency): nothing endures through its own power; everything depends continuously on divine command. To attend to entropy is to attend to contingency—to recognize the fragility of existence and the responsibility that arises from it.

Thermodynamic irreversibility does not contradict this worldview; it complements it. If entropy marks what cannot be repeated or fully reversed, then every action—physical or moral—serves as an inscription in the unfolding history of the universe. Landauer’s principle reinforces this: resetting a single bit to a known state dissipates at least of heat into an environment at temperature T (Landauer 1961). Information erasure is inherently dissipative and therefore irreversible.

Zurek (2003, 2009) explains how quantum decoherence preserves informational traces, while Zee (2010) outlines the quantum-field-theoretic and cosmological structures that underwrite their persistence. Landauer’s bound has been experimentally verified in colloidal particle erasure, nanoscale magnetic memory, and quantum nonequilibrium realizations of Maxwell’s demon (Bérut et al. 2012; Hong et al. 2016; Camati et al. 2016; Aimet et al. 2025). In each case, erasure generates real, measurable heat—an indelible thermodynamic signature. By analogy, every irreversible transition inscribes its history into the entropic memory of the cosmos.

Time thus emerges not as a neutral background but as an ethical medium. Entropy clarifies the structure of what is; revelation addresses why it matters. Kantian ethics grounds meaning in pure reason yet struggles to reconcile moral agency with the lived irreversibility of becoming. Revelation completes the picture by interpreting the physical inevitability of entropy as a metaphysical horizon where intention, agency, contingency, and divine decree converge. This insight aligns with the emerging philosophy of information, which examines how meaning arises from structural and irreversible processes (Floridi 2002, 20

8. The Direction of Time and Moral Values: A Qur’ānic Reading Through Sūrah al-ʿAṣr

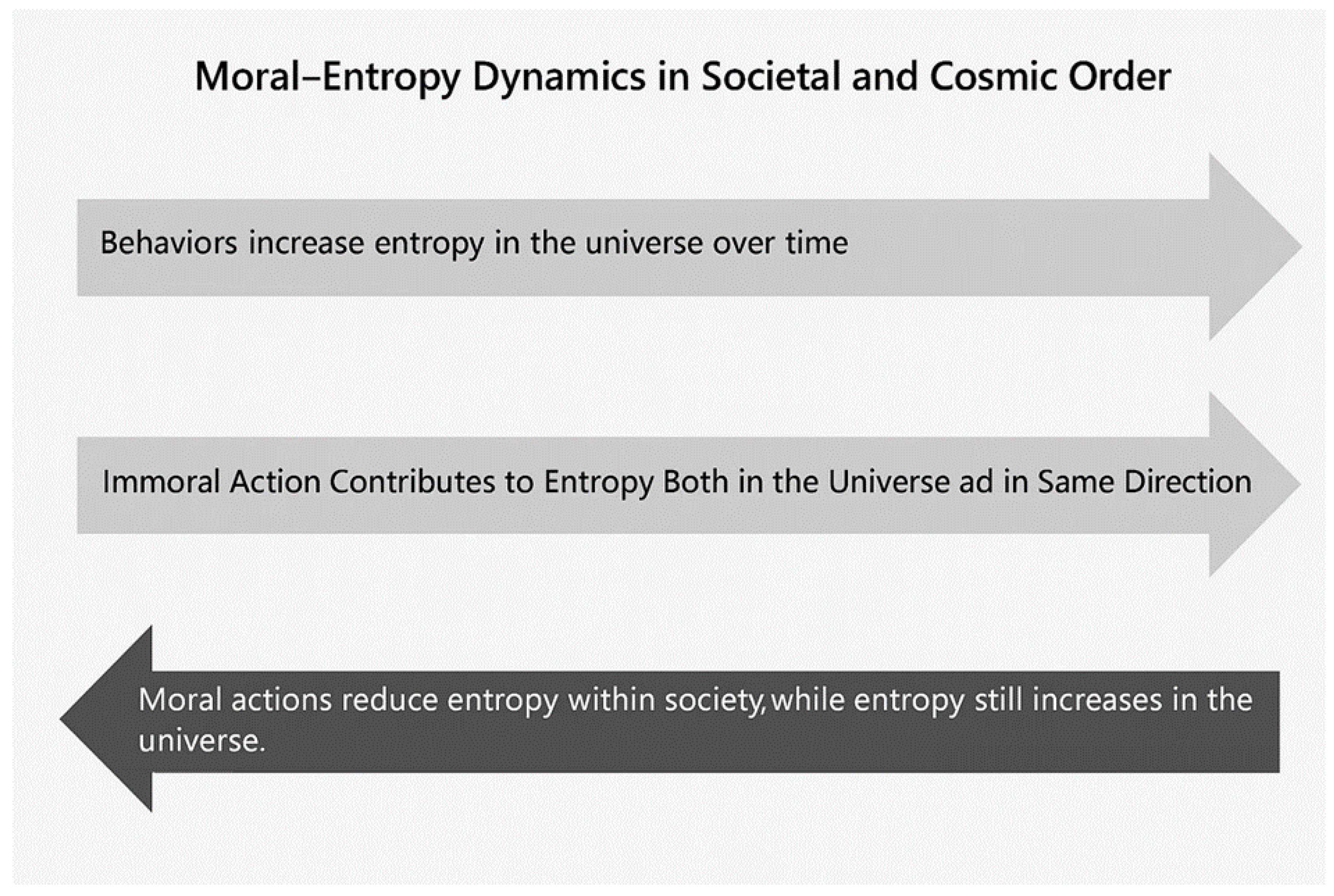

The second law of thermodynamics states that, in isolated macroscopic systems, coarse-grained entropy tends to increase over time. Originally formulated for heat engines and molecular processes, the principle has since inspired broader analogical applications—to ecological collapse, civilizational decline, and cultural fragmentation (Clausius 1865; Shannon 1948; Peacocke 1984; Russell 1984; Nürnberger 2012; Fisher 2024). Entropy marks the drift toward disorder, the leveling of probabilities, and the dissipation of usable information. Yet against this universal trend, pockets of order—living organisms, enduring cultures, resilient moral communities—emerge and persist by exporting entropy into their surroundings, entirely in accordance with the second law (Schrödinger 1992; Prigogine 1980; Peacocke 1993).

This tension between global decay and localized coherence is both scientifically and metaphysically significant. As Schrödinger famously observed, life maintains itself by “feeding on negative entropy”—a metaphor for importing order and exporting disorder (Schrödinger 1992). Moral systems can be viewed analogously as forms of ethical negentropy. They do not halt the arrow of time but generate structure, meaning, and durability within its flow (Peacocke 1993; Murphy 1991; Polkinghorne 2006). Early cybernetics recognized feedback, communication, and control as modes of order formation with ethical relevance (Wiener 1950, 1964). Ethics thus appears not as an artificial imposition upon nature but as a structural attunement to the universe’s deep regularities (Price 1996; Rovelli 2018).

Within this interpretive horizon,

Sūrah al-ʿAṣr—one of the Qurʾān’s briefest yet most incisive chapters—acquires heightened philosophical resonance. It opens with a cosmic oath,

wa’l-ʿaṣr (“By Time” / “By the Declining Day”), summoning the temporal flow itself as witness. This is followed by a stark verdict

: “Truly, man is in loss—except those who believe, do good deeds, urge one another to truth, and urge one another to steadfastness” (Q 103:1–3). On an analogical reading,

loss (

khusrān) corresponds to the entropic condition of existence: as time unfolds irreversibly, disorder intensifies, and unstructured human life tends toward dissolution (Gołosz 2021; Penrose 2011). Yet the sūrah introduces a counter-entropic ethic—faith, righteous action, truth, and patience—that functions as a moral negentropy preserving coherence in a universe governed by entropic drift (Peacocke 1993; Murphy 1991; cf. Lindsay 1959).

Figure 1 schematically illustrates this structure, adapted from Lindsay’s early articulation of a “thermodynamic imperative” (Lindsay 1959).

Within this conceptual frame, the sūrah’s four imperatives outline an architecture of resistance to entropic decay:

Faith (īmān) acts like a thermal reservoir, absorbing fluctuations of doubt and providing a stable moral “temperature,” analogous to an energy source that stabilizes a thermodynamic system.

Righteous deeds (ʿamal ṣāliḥ) function like a heat engine, converting intention into structured action that exports moral disorder while generating local coherence.

Mutual exhortation to truth (tawāṣī bi’l-ḥaqq) resembles a heat exchanger, circulating clarity and reducing informational entropy within a community.

7)

Mutual exhortation to patience (tawāṣī bi’l-ṣabr) operates as an insulator, preserving moral structure against the continuous entropic pressures of time.

Seen in this light, Sūrah al-ʿAṣr does not present a futile attempt to resist entropy; it articulates a theological ethic for inhabiting time rightly. Wa’l-ʿaṣr is not merely rhetorical emphasis but an ontological warning: time itself is loss unless met with coherence, intention, and virtue. The arrow of time thus becomes not only a thermodynamic vector but a moral horizon—a space in which responsibility, steadfastness, and truth confer intelligibility amid the universe’s drift toward dissolution.

9. Entropy, Procreation, and the Moral Status of Lawful Acts

This section intentionally moves away from abstract moral theory—whether deontological, consequentialist, or virtue-ethical—to the lived reality of religiously embedded ethics. For much of humanity, moral life is structured not primarily by philosophical abstraction but by historically rooted legal–ethical traditions. Any metaphysical account of agency seeking existential coherence must therefore reckon with these frameworks. The normative authority of divine law is acknowledged here not as a retreat from reason but as a durable and historically embodied architecture of moral orientation.

A frequent objection to interpreting moral life through an entropic lens is that such a framework may risk pathologizing change, growth, or proliferation as disorder. Procreation—explicitly encouraged in the Islamic tradition—introduces new sentient beings into the world and might appear, at first glance, to intensify social or systemic entropy. Similarly, divorce, though legally permitted, can disrupt established relational structures. Does this mean that such lawful acts contribute to moral dissolution?

The Qurʾānic worldview offers a far more subtle account. Islam encourages procreation within marriage not as unregulated biological expansion but as ordered continuity. The family functions as a local ethical system capable of managing entropy: reproduction adds new variables, yet it does so within a covenantal framework that channels potential disorder toward intergenerational stability (cf. Schrödinger 1992; Peacocke 1993; Murphy 1991). A clarifying physical analogy is crystallization: a liquid does not solidify into perfect uniformity but into grains of internal coherence separated by grain boundaries. Heat is released, yet local order increases. The rate and structure of crystal growth—shaped by gradients or concentrations—determine the quality of the emergent order. Likewise, marriage serves as an ethical crystallization in which relational potential is formed into durable responsibility, guided by divine command and supported by community (Peacocke 1993; Polkinghorne 2006; Porter et al. 2009).

Prophetic traditions reinforce this moral architecture. Among them: “Marry and multiply, for I will boast of your numbers on the Day of Judgment” (Sunan Ibn Mājah 1846), and “Marry loving and fertile women, for I shall take pride in your abundance” (Sunan al-Nasāʾī 3227). These reports do not celebrate reproduction as mere numerical increase; they place it within a framework of divine purpose and communal stewardship (Bakar 1998). Conversely, the well-known report that “The most hated of permissible things to Allah is divorce” (Sunan Ibn Mājah 2018) indicates that not all lawful (ḥalāl) actions carry equal moral weight; their ethical significance requires situational discernment (ḥikma).

Even divorce, typically associated with rupture, can serve as ethical recalibration. The Qurʾān states: “If a couple do separate, God will enrich both of them from His abundance; God is All-Encompassing, All-Wise” (Q 4:130). Separation does not necessarily signify collapse; it can operate—much like grain boundaries in a crystal—as a mechanism for redistributing internal tensions and restoring wider stability.

In this light, Islam does not deny entropy; it incorporates it. Human agency inevitably generates entropic traces, but lawful actions—when oriented by divine command—channel these traces toward moral form rather than dissolution. The verse “Corruption has appeared on land and sea because of what people’s hands have earned, so that He may let them taste some of what they have done, that they might return” (Q 30:41) highlights this dynamic. The phrase kasabat aydī al-nās (“what people’s hands have earned”) is morally expansive: it includes not only sin but the full range of consequences arising from human action.

Procreation and divorce, as lawful acts, indeed produce entropic residues; they reshape relational and social landscapes. Yet their moral status depends on how they are structured—marriage as ethical crystallization, divorce as calibrated restructuring—within a divine framework that redirects potential disorder toward stability, justice, and purpose. In this way, the entropic condition of existence becomes not a threat to moral order but a medium through which divine law generates coherence across the unfolding of human life.

10. Conclusion

When the physical and metaphysical dimensions of the cosmos are considered together, the second law of thermodynamics appears as more than a scientific axiom. Entropy does not merely describe the irreversible flow of energy; it functions as a cosmic architecture of inscription, rendering events ontologically enduring (Clausius 1865; Shannon 1948; Penrose 2011). This study does not derive moral “oughts” from physical “is.” Instead, it treats physics as specifying constraints—on the formation, energetic cost, and durability of records—within which normative claims are articulated theologically.

Within this interpretive horizon, entropy becomes not only a thermodynamic or informational quantity but a structural principle embedded in the moral design of reality. Qurʾānic notions such as kitāb (Book), ṣaḥīfa (Record), and istinsākh (Transcription) operate as structural counterparts to entropy’s role in encoding action and preserving consequence (Q 36:12; Q 45:29). The universe thus appears simultaneously as a physical system and a moral ledger in which nothing is lost—only transformed and recorded.

Every human act inscribes a trace within the informational fabric of the cosmos. While these traces are irreversible at macroscopic scales, repentance (tawba) reconfigures their moral significance. Divine mercy does not negate law; it elevates its semantic horizon: “God erases or confirms whatever He wills, and the source of Scripture is with Him” (Q 13:39). In aligning cosmological irreversibility with moral possibility, the Qurʾān positions time as the medium through which responsibility is disclosed.

Sūrah al-ʿAṣr embeds moral obligation within the very temporality governed by entropy: “By the declining day, man is in loss—except those who believe, do good deeds, urge one another to truth, and urge one another to patience” (Q 103:1–3). These imperatives do not override physical laws; rather, they transform the flow within those laws to generate localized order—establishing, in Schrödinger-inspired terms, a structure that may be called ‘moral negentropy’ (Schrödinger 1992; Peacocke 1993; Murphy 1991; cf. Lindsay 1959).The Qurʾānic worldview transforms the arrow of time from a source of despair into a horizon of responsibility.

This stands in contrast to Kantian deontology, which isolates moral law from physical causality (Kant (1788) 2002). Without collapsing the nature/freedom distinction, the Qurʾānic paradigm embeds agency within the irreversible architecture of time, in which the “cost” of moral action corresponds to the statistical character of entropy and becomes the condition for accountability. Disorder (fasād) is not merely the result of sin but a structural consequence of human intervention (Q 30:41). Even lawful acts—such as procreation or divorce—generate entropic residues and must be guided by divine frameworks to sustain balance (Q 4:130). Islam thus integrates entropy not only into physics but into intentions, relationships, and societies, constructing legal and spiritual architectures to redirect it toward stability and purpose (Nürnberger 2012; Peacocke 1993; Polkinghorne 2006).

The bridge constructed here between thermodynamics and revelation is not merely metaphorical; it motivates an analogical–structural reading that preserves categorical boundaries. Both entropy and revelation affirm that nothing truly disappears; all is transformed, witnessed, and preserved (Clausius 1865; Shannon 1948; Q 36:12). In this sense, the cosmos is a book, and salvation lies not in resisting its grammar but in learning to read it rightly and aligning one’s life with its orientation.

Relative to rationalist ethics, this Qurʾānic moral cosmology appears more empirically grounded: it roots moral life not in abstract reason alone but in irreversible and measurable features of the universe—structures such as information, recordability, and time’s asymmetry (Shannon 1948; Rovelli 2018). This suggests a form of metaphysical empiricism in which ethical meaning is simultaneously empirical, structural, and transcendent.

Future research may explore how this Qurʾān-centered moral cosmology reframes debates on theodicy, ecology, or AI ethics. What follows when entropy is understood as moral infrastructure? What horizons open for theology, philosophy, and law? While preliminary, this synthesis gestures toward a unified grammar where physics and revelation converge in the structures of inscription, responsibility, and order.

In conclusion, entropy emerges not merely as a physical principle but as a metaphysical horizon sustaining moral responsibility. Every deed is irreversibly inscribed into the architecture of time, yet divine mercy reshapes how those inscriptions are read. This dual vision—law and mercy, irreversibility and reorientation—offers a constructive contribution to contemporary science–religion discourse. Entropy, so understood, is not a threat to coherence but a condition for accountability; for a recent philosophical defense of affirming entropy, see Woodward (2025). Rooted in Islamic thought, its implications extend across traditions, inviting renewed dialogue among theology, philosophy, and the natural sciences.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve studies with human participants or animals.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Author Contributions

Sole author: conceptualization; investigation; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Abdel Haleem, Muhammad A. S. The Qurʾān: A New Translation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abū Dāwūd, Sulaymān ibn; al-Ashʿath. Sunan Abī Dāwūd; Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah: Beirut, n.d. [Google Scholar]

- Aimet, Stefan; Tajik, Mohammadamin; Tournaire, Gabrielle; Schüttelkopf, Philipp; Sabino, João; Sotiriadis, Spyros; Guarnieri, Giacomo; Schmiedmayer, Jörg; Eisert, Jens. Experimentally Probing Landauer’s Principle in the Quantum Many-Body Regime. Nature Physics 2025, 21 (August), 1326–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid. The Incoherence of the Philosophers (Tahāfut al-Falāsifa); Marmura, Michael E., Translator; Brigham Young University Press: Provo, UT, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bakar, Osman. Classification of Knowledge in Islam; The Islamic Texts Society: Cambridge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bérut, Antoine; Arakelyan, Armen; Petrosyan, Artyom; Ciliberto, Sergio; Dillenschneider, Roberto; Lutz, Eric. Experimental Verification of Landauer’s Principle Linking Information and Thermodynamics. Nature 2012, 483, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boltzmann, Ludwig. Über die Beziehung zwischen dem zweiten Hauptsatzes der mechanischen Wärmetheorie und der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung, respektive Sätzen über das Wärmegleichgewicht; Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Klasse: Wien, 1877; Volume 76, pp. 373–435. [Google Scholar]

- Camati, Patrícia A.; Peterson, José P. S.; Batalhão, Tiago B.; Micadei, K.; Souza, A. M.; Sarthour, R. S.; Oliveira, I. S.; Serra, Roberto M. Experimental Rectification of Entropy Production by a Maxwell’s Demon in a Quantum System. Physical Review Letters 2016, 117, 240502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clausius, Rudolf. Ueber verschiedene für die Anwendung bequeme Formen der Hauptgleichungen der mechanischen Wärmetheorie. Annalen der Physik und Chemie 1865, 201(7), 353–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, Michał. Conformal Cyclic Cosmology, Gravitational Entropy and Quantum Information. General Relativity and Gravitation 2023, 55, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddington, Arthur S. The Nature of the Physical World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Matthew Zaro. Entropy and the Idea of God(s): A Philosophical Approach to Religion as a Complex Adaptive System. Religions 2024, 15(8), 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, Luciano. What Is the Philosophy of Information? Metaphilosophy 2002, 33(1–2), 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, Luciano. The Ethics of Information; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilov, Momčilo; Bechhoefer, John. Direct Measurement of Weakly Nonequilibrium System Entropy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114(48), 11097–11102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J. Willard. Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics: Developed with Especial Reference to the Rational Foundation of Thermodynamics; Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York; Edward Arnold: London; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołosz, Jerzy. Entropy and the Direction of Time. Entropy 2021, 23(4), 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-P.; Lambson, B.; Dhuey, S.; Bokor, J. Experimental Test of Landauer’s Principle in Single-Bit Operations Using a Nanomagnetic Memory. Science Advances 2016, 2, e1501492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, Edwin T. Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics. Physical Review 1957a, 106(4), 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, Edwin T. Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics II. Physical Review 1957b, 108(2), 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Yonggun; Gavrilov, Momčilo; Bechhoefer, John. High-Precision Test of Landauer’s Principle in a Feedback Trap. Physical Review Letters 2014, 113, 190601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, Immanuel. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals; Gregor, Mary, Korsgaard, Christine M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1785] 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Practical Reason; Pluhar, Werner S., Engstrom, Stephen, Eds.; Hackett Publishing: Indianapolis/Cambridge, 1788] 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Landauer, Rolf. Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process. IBM Journal of Research and Development 1961, 5(3), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R. B. Entropy Consumption and Values in Physical Science. American Scientist 1959, 47(3), 376–385. [Google Scholar]

- Massoudi, Mehrdad. A Possible Ethical Imperative Based on the Entropy Law. Entropy 2016, 18(11), 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikki, Said. On the Direction of Time: From Reichenbach, Prigogine, and Penrose to an Alternating Causality Theory? Philosophies 2021, 6(4), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, George L. Time, Thermodynamics, and Theology. Zygon 1991, 26(3), 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nürnberger, Klaus. Eschatology and Entropy: An Alternative to a Disqualified Teleology. Zygon 2012, 47(4), 937–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacocke, Arthur. Thermodynamics and Life. Zygon 1984, 19(4), 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacocke, Arthur. Theology for a Scientific Age: Being and Becoming—Natural, Divine and Human, 2nd ed.; SCM Press: London, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, Roger. The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, Roger. Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, Roger. On the Gravitization of Quantum Mechanics II: Conformal Cyclic Cosmology. Foundations of Physics 2014, 44, 873–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, John. Space, Time, and Causality. Zygon 2006, 41(4), 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, David A.; Easterling, Kenneth E.; Sherif, Mohamed Y. Phase Transformations in Metals and Alloys, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Huw. Time’s Arrow and Archimedes’ Point: New Directions for the Physics of Time; Oxford University Press: New York and Oxford, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, Ilya. From Being to Becoming: Time and Complexity in the Physical Sciences; W. H. Freeman: San Francisco, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, Carlo. The Order of Time; Segre, Erica; Carnell, Simon, Translators; Riverhead Books: New York, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Robert John. Entropy and Evil. Zygon 1984, 19(4), 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, Erwin. What Is Life? with Mind and Matter & Autobiographical Sketches. Canto edition. Foreword to What Is Life? by Roger Penrose, 14th printing ed; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1944] 1992; ISBN 978-1-107-60466-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, Claude E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27(3) 27 (4), 379–423 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al-Nasāʾī, Sunan. Hadith 3227. Sunnah.com. Available online: https://sunnah.com/nasai:3227 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Majah, Sunan Ibn. Hadith 1846 (Book of Marriage). Sunnah.com. Available online: https://sunnah.com/ibnmajah:1846 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Sunan Ibn Majah 2018, Sunnah.com. Available online: https://sunnah.com/ibnmajah:2018 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Muslim, Ṣaḥīḥ. Hadith 2577a. Sunnah.com. Available online: https://sunnah.com/muslim:2577 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Wiener, Norbert. The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society; Houghton Mifflin: Boston; The Riverside Press: Cambridge, MA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, Norbert. God and Golem, Inc.: A Comment on Certain Points Where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, Ashley. Affirming Entropy. Technophany 2025, 2(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, Wojciech H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of Modern Physics 2003, 75(3), 715–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, Wojciech. Quantum Darwinism. Nature Physics 2009, 5, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).