Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Trichoderma Species

3. Mechanisms of Trichoderma

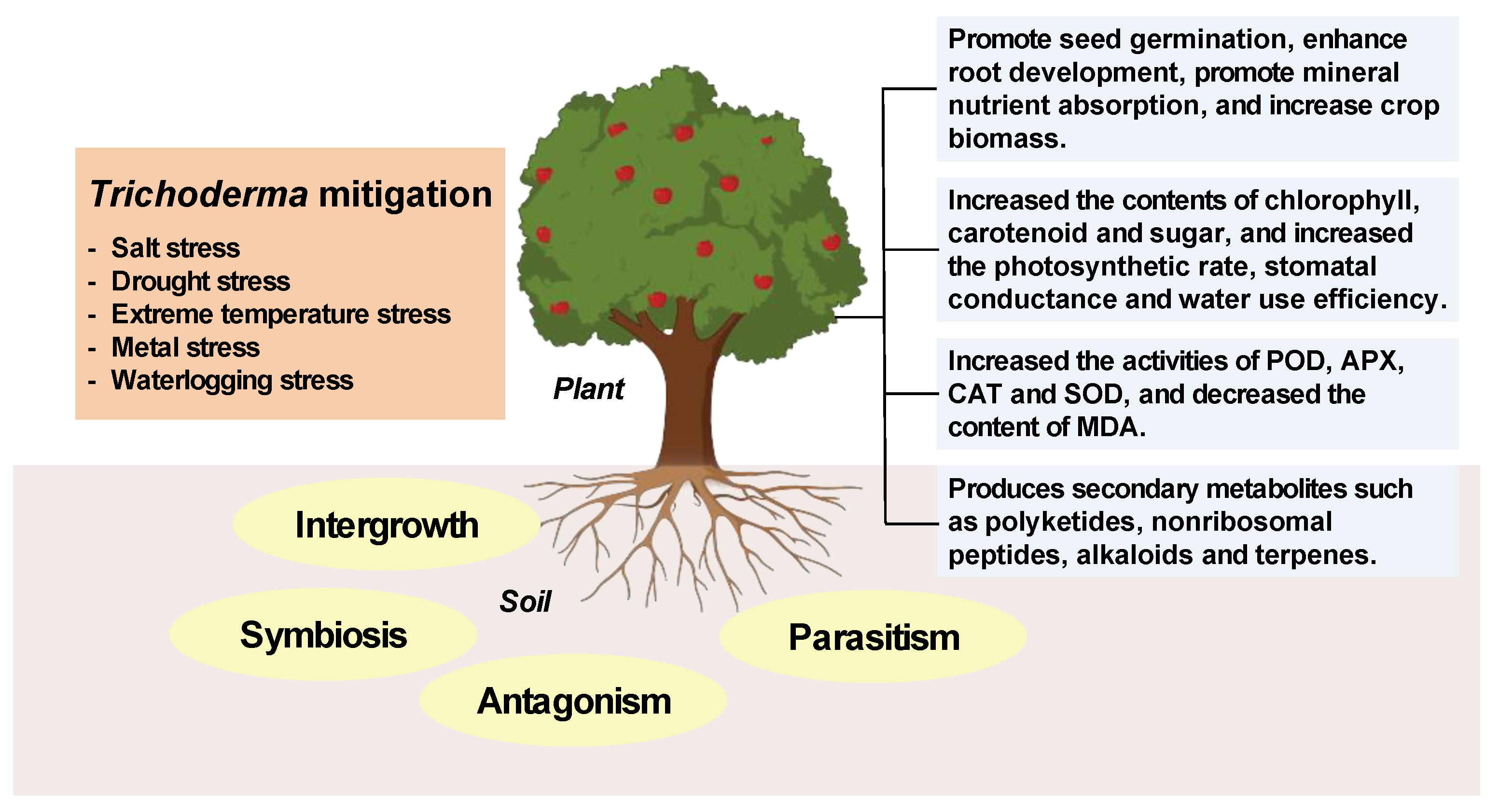

4. Application of Trichoderma in Crop Resistance to Abiotic Stress

4.1. Salt Stress

4.2. Drought Stress

4.3. Extreme Temperature Stress

4.4. Heavy Metal Stress

4.5. Waterlogging Stress

5. Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zia, M.U.; Sambasivam, P.T.; Chen, D.; Bhuiyan, S.A.; Ford, R.; Li, Q. A carbon dot toolbox for managing biotic and abiotic stresses in crop production systems. EcoMat. 2024, 6, e12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J.K. Thriving under Stress: How Plants Balance Growth and the Stress Response. Cells Dev. 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, R.F.; Ge, Y.R.; Li, Y.F.; Li, R.L. Plants’ Response to Abiotic Stress: Mechanisms and Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, F.M.A.; Islam, M.A.; Rubel, M.H.; Bhattacharya, D.; Ahmed, F. A sustainable methodological approach for mitigation of salt stress of rice seedlings in coastal regions: Identification of halotolerant rhizobacteria from Noakhali, Bangladesh and their impact. MethodsX 2024, 13, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Zhou, W.; Li, J.; Luo, M.Q.; Scheres, B.; Guo, Y. On salt stress, PLETHORA signaling maintains root meristems. Cells Dev. 2023, 58, 1657–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.J.; Strøbech, E.; Qiao, Y.J.; Konakalla, N.C.; Harris, P.; Peschel, G.; Agler-Rosenbaum, M.; Weber, T.; Andreasson, E.; Ding, L. Streptomyces alleviate abiotic stress in plant by producing pteridic acids. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Akhtar, M.S.; Siraj, M.; Zaman, W. Molecular Communication of Microbial Plant Biostimulants in the Rhizosphere Under Abiotic Stress Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.W.; Brettell, L.E.; Qiu, Z.G.; K.Singh, B. Microbiome-Mediated Stress Resistance in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.L.; Hermosa, R.; Lorito, M.; Enrique, M. Trichoderma: a multipurpose, plant-beneficial microorganism for eco-sustainable agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, M.; Kapoor, D.; Kumar, V.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ramarkrishnan, M.; Landi, M.; Landi, M.; Araniti, F.; Sharma, A. Trichoderma: The "Secrets" of a Multitalented Biocontrol Agent. Plants 2020, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TariqJaveed, M.; Farooq, T.; Al-Hazmi, A.S.; Hussain, M.D.; Rehman, A.U. Role of Trichoderma as a biocontrol agent (BCA) of phytoparasitic nematodes and plant growth inducer. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2021, 183, 107626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, P.L.; Rai, P.; Srivastava, A.K.; Kumar, S. Trichoderma for climate resilient agriculture. World J. Microb. Biot. 2017, 33, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bononi, L.; Chiaramonte, J.B.; Pansa, C.C.; Moitinho; et al. Phosphorus-solubilizing Trichoderma spp. from Amazon soils improve soybean plant growth. J. Archaeol Sci.-Rep. 2020, 10, 2858. [Google Scholar]

- Vinale, F.; Sivasithamparam, K. Beneficial effects of Trichoderma secondary metabolites on crops. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2835–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, F.; Druzhinina, I.S. In honor of John Bissett: authoritative guidelines on molecular identification of Trichoderma. Fungal divers. 2021, 107, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Schmoll, M.; Esquivel-Ayala, B.A.; E.Gonzalez-Esquivel, C.; Rocha-Ramirez, V.; Larsen, J. Abiotic plant stress mitigation by Trichoderma species. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2024, 6, 240240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyśkiewicz, R.; Nowak, A.; Ozimek, E.; Jolanta, J.S. Trichoderma: The Current Status of Its Application in Agriculture for the Biocontrol of Fungal Phytopathogens and Stimulation of Plant Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.; Najeeb, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Hou, J.M.; Liu, T. Insights into the molecular mechanism of Trichoderma stimulating plant growth and immunity against phytopathogens. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 175, e14133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Zou, C.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, X.J.; Ye, X.L. Effects of Reduced Phosphate Fertilizer and Increased Trichoderma Application on the Growth, Yield, and Quality of Pepper. Plants 2023, 12, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halifu, S.; Deng, X.; Song, X.; Song, R.Q. Effects of Two Trichoderma Strains on Plant Growth, Rhizosphere Soil Nutrients, and Fungal Community of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica Annual Seedlings. Forests 2019, 10, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.N.; Singh, V.; Awasthi, S.K. Trichoderma induced improvement in growth, yield and quality of sugarcane. Sugar Tech 2006, 8, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, R.; Mao, Y.R.; Jiang, W.T.; Chen, X.S.; Shen, X.; Yin, C.M.; Mao, Z.Q. Effects of Trichoderma asperellum 6S-2 on Apple Tree Growth and Replanted Soil Microbial Environment. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmoaty, S.; Khandaker, M.M.; Mahmud, K.; Majrashi, A.; Alenazi, M.M.; Badaluddin, N.A. Influence of Trichoderma harzianum and Bacillus thuringiensis with reducing rates of NPK on growth, physiology, and fruit quality of Citrus aurantifolia. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, e261032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, F.J.; Ge, H.L.; Tian, F.S.; Yang, T.W.; Ma, K.; Zhang, Y. Trichoderma harzianum mitigates salt stress in cucumber via multiple responses. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2019, 170, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Macias-Rodriguez, L.; Alfaro-Cuevas, R.; Lopez-Bucio, J. Trichoderma spp. Improve growth of Arabidopsis seedlings under salt stress through enhanced root development, osmolite production, and Na(+) elimination through root exudates. Mol. Plant Microbe. In. 2014, 27, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, B.; Gan, Y. Seed Treatment with Trichoderma longibrachiatum T6 Promotes Wheat Seedling Growth under NaCl Stress Through Activating the Enzymatic and Nonenzymatic Antioxidant Defense Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastouri, F.; Bjorkman, T.; Harman, G.E. Trichoderma harzianum enhances antioxidant defense of tomato seedlings and resistance to water deficit. Mol. Plant Microbe. In. 2012, 25, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudeletti, D.; Crusciol, C.; Bossolani, J.W.; Moretti, L.G.; Momesso, L.; Brenda, S.T.; de Castro, S.G.Q.; De Oliveira, E.F.; Hungria, M. Trichoderma asperellum Inoculation as a Tool for Attenuating Drought Stress in Sugarcane. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 645542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrouz, M.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Fazeli-Nasab, B.; Piri, R.; Almalki, W.H.; Fitriatin, B.N. Seed bio-priming with beneficial Trichoderma harzianum alleviates cold stress in maize. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, P.; Singh, P.C.; Mishra, A.; Srivastava, S.; Chauhan, R.; Awasthi, S.; Mishra, S.; Dwivedi, S.; Tripathi, P.; Kalra, A.; Tripathi, R.D.; Nautiyal, C.S. Arsenic tolerant Trichoderma sp. reduces arsenic induced stress in chickpea (Cicer arietinum). Environ. Pollut. 2017, 223, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez-Geffriaud, V.; Vicente, R.; Vergara-Diaz, O.; Reinaldo, J.J.N.; Trillas, M.I. Application of Trichoderma asperellum T34 on maize (Zea mays) seeds protects against drought stress. Planta Daninha 2020, 252, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, N.; Caira, S.; Troise, A.D.; Scaloni, A.; Vitaglione, P.; Vinale, F.; Marra, R.; Salzano, A.M.; Lorito, M.; Woo, S.L. Trichoderma Applications on Strawberry Plants Modulate the Physiological Processes Positively Affecting Fruit Production and Quality. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, K.; Zhu, M.Y.; Su, H.Y.; Liu, X.; Li, S.X.; Zhi, Y.B.; Li, Y.X.; Zhang, J.D.; Thomas, S. Trichoderma asperellum boosts nitrogen accumulation and photosynthetic capacity of wolfberry (Lycium chinense) under saline soil stress. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpad148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbanpour, A.; Salimi, A.; Ghanbary, M.A.T.; Pirdashti, H.; Dehestani, A. The effect of Trichoderma harzianum in mitigating low temperature stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. Sci. Hortic.-Ams Terdam 2017, 230, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusnawan, E.; Taufiq, A.; Wijanarko, A.; Susilowati, D.M.; Praptana, R.H.; Chandra-Hioe, M.V.; Supriyo, A.; Inayati, A. Changes in Volatile Organic Compounds from Salt-Tolerant Trichoderma and the Biochemical Response and Growth Performance in Saline-Stressed Groundnut. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Ali, N.; Jan, G.; Iqbal, A.; Hamayun, M.; Jan, F.G.; Hussain, A.; Lee, I. Trichoderma reesei improved the nutrition status of wheat crop under salt stress. J. Plant Interact. 2019, 14, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.L.; Yang, H.; Hu, J.D.; Li, H.M.; Zhao, Z.J.; Wu, Y.Z.; Li, J.S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, K.; Yang, H.T. Trichoderma harzianum inoculation promotes sweet sorghum growth in the saline soil by modulating rhizosphere available nutrients and bacterial community. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1258131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.P.; Shi, H.F.; Yang, Y.Q.; Feng, X.X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.H.; Guo, Y. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J. Genet. Genomics 2024, 51, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastouri, F.; Björkman, T.; Harman, G.E. Seed treatment with Trichoderma harzianum alleviates biotic, abiotic, and physiological stresses in germinating seeds and seedlings. Phytopathology 2010, 100, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Wang, W.W.; Hu, Y.H.; Peng, Z.P.; Ren, S.; Xue, M.; Liu, Z.; Hou, J.; Xing, M.Y.; Liu, T. A novel salt-tolerant strain Trichoderma atroviride HN082102.1 isolated from marine habitat alleviates salt stress and diminishes cucumber root rot caused by Fusarium oxysporum. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotman, Y.; Landau, U.; Cuadros-Inostroza, A.; Takayuki, T.; Fernie, A.; Chet, I.; Viterbo, A.; Willmitzer, L. Trichoderma-plant root colonization: escaping early plant defense responses and activation of the antioxidant machinery for saline stress tolerance. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, S.M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Naveed, M.; Ashraf, M. Microbial ACC-Deaminase: Prospects and Applications for Inducing Salt Tolerance in Plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2010, 6, 360–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z. Plant abiotic stress: New insights into the factors that activate and modulate plant responses. J. Integr. Plant biol. 2021, 63, 429–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, N.; Pang, Q.Y.; Khan, R.A.A.; Xu, Q.S.; Wu, C.D.; Liu, T. A Salt-Tolerant Strain of Trichoderma longibrachiatum HL167 Is Effective in Alleviating Salt Stress, Promoting Plant Growth, and Managing Fusarium Wilt Disease in Cowpea. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, S.; Zhang, S.W.; Xu, B.L.; Li, T.; Calderon-Urrea, A.; Tiika, R.J. Trichoderma longibrachiatum TG1 increases endogenous salicylic acid content and antioxidants activity in wheat seedlings under salinity stress. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Macias-Rodriguez, L.; Alfaro-Cuevas, R.; Lopez-Bucio, J. Trichoderma spp. Improve growth of Arabidopsis seedlings under salt stress through enhanced root development, osmolite production, and Na(+)elimination through root exudates. Mol. Plant Microbe In. 2014, 27, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.S.; Zhang, Q.K.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhou, H.P.; Ma, C.; Wang, P.P. Regulation of Plant Responses to Salt Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gan, Y.; Xu, B. Mechanisms of the IAA and ACC-deaminase producing strain of Trichoderma longibrachiatum T6 in enhancing wheat seedling tolerance to NaCl stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Lesk, C.; Rowhani, P.; Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2016, 529, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Boorboori, M.; Zhang, H. The Mechanisms of Trichoderma Species to Reduce Drought and Salinity Stress in Plants. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 92, 2261–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wang, W.; Hou, J.; Li, X.E. Dark Septate Endophytes Isolated From Wild Licorice Roots Grown in the Desert Regions of Northwest China Enhance the Growth of Host Plants Under Water Deficit Stress. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 522449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstecka, Z.; Antoszewski, M.; Mierek-Adamska, A.; Krauklis, D.; Niedojadlo, K.; Kaliska, B.; Hrynkiewicz, K.; Dabrowska, G.B. Trichoderma viride Colonizes the Roots of Brassica napus L., Alters the Expression of Stress-Responsive Genes, and Increases the Yield of Canola under Field Conditions during Drought. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.N.; Dwivedi, P.; Sarma, B.K.; Singh, G.S.; Singh, H.B. Trichoderma asperellum T42 Reprograms Tobacco for Enhanced Nitrogen Utilization Efficiency and Plant Growth When Fed with N Nutrients. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Jiang, X.; Xu, H.Y.; Ding, G.J. Trichoderma longibrachiatum Inoculation Improves Drought Resistance and Growth of Pinus massoniana Seedlings through Regulating Physiological Responses and Soil Microbial Community. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, R.; Nawaz, M.S.; Siddique, M.J.; Hakim, S.; Imran, A. Plant survival under drought stress: Implications, adaptive responses, and integrated rhizosphere management strategy for stress mitigation. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 5, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, P.M.; Santos, M.P.; Andrade, C.M.; Souza-Neto, O.A.; Ulhoa, C.J.; Lima, A.; Francisco, J. Overexpression of an aquaglyceroporin gene from Trichoderma harzianum improves water-use efficiency and drought tolerance in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Physiol. Indian J. Biochem. Bio. 2017, 121, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashyal, B.M.; Parmar, P.; Zaidi, N.W.; Aggarwal, R. Molecular Programming of Drought-Challenged Trichoderma harzianum-Bioprimed Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 655165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Teng, R.M.; Liu, J.X.; Yang, Y.Z.; Lin, S.J.; Han, M.H.; Li, J.Y.; Zhuang, J. Identification and Analysis of Genes Involved in Auxin, Abscisic Acid, Gibberellin, and Brassinosteroid Metabolisms Under Drought Stress in Tender Shoots of Tea Plants. DNA Cell Biol. 2019, 38, 1292–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszuk-Scisel, J.; Tyskiewicz, R.; Nowak, A.; Ozimek, E.; Majewska, M.; Hanaka, A.; Tyskiewice, K.; Pawlik, A.; Janusz, G. Phytohormones (Auxin, Gibberellin) and ACC Deaminase In Vitro Synthesized by the Mycoparasitic Trichoderma DEMTkZ3A0 Strain and Changes in the Level of Auxin and Plant Resistance Markers in Wheat Seedlings Inoculated with this Strain Conidia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Zhao, X.B.; Bürger, M.; Chory, J.; Wang, X.C. The role of ethylene in plant temperature stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Jiang, S.; Xiong, R.; Shanfique, K.; Zahid, K.R.; Wang, Y. Response and tolerance mechanism of food crops under high temperature stress: a review. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, 253815-e253898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokszczanin, K.L.; Fragkostefanakis, S.; Solanaceae, P.T.I.T. Perspectives on deciphering mechanisms underlying plant heat stress response and thermotolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Sui, J.J.; Li, H.Y.; Yue, W.X.; Liu, T.; Hou, D.; Liang, J.H.; Wu, Z. Enhancing heat stress tolerance in Lanzhou lily (Lilium davidii var. unicolor) with Trichokonins isolated from Trichoderma longibrachiatum SMF2. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1182977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.; Keswani, C.; Tewari, R. Trichoderma Koningii enhances tolerance against thermal stress by regulating ROS metabolism in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. J. Plant Interact. 2021, 16, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.A.; Hussain, S.; Khaliq, A.; Ashraf, U.; Anjum, S.A.; Men, S.N.; Wang, L.C. Chilling and Drought Stresses in Crop Plants: Implications, Cross Talk, and Potential Management Opportunities. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, E.; Ortega-Amaro, M.A.; Salazar-Badillo, F.B.; Bautisa, E.; Douter, J.B.; Juan, F. The Arabidopsis-Trichoderma interaction reveals that the fungal growth medium is an important factor in plant growth induction. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16414–16427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi-Shahandashti, S.S.; Maali-Amiri, R. Global insights of protein responses to cold stress in plants: Signaling, defence, and degradation. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 226, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Wang, R.X.; Sun, X.A.; Liu, L.N.; Liu, P.; Tang, J.C.; Zhang, C.X.; Liu, H. Heavy metal stress in plants: Ways to alleviate with exogenous substances. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 897, 165397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaf, M.A.; Hao, Y.Y.; Shu, H.Y.; Mumtaz, M.A.; Cheng, S.H.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Ahmad, P.; Wang, Z. Melatonin enhanced the heavy metal-stress tolerance of pepper by mitigating the oxidative damage and reducing the heavy metal accumulation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Parihar, P.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Heavy Metal Tolerance in Plants: Role of Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics, and Ionomics. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez Vargas, J.; Rodríguez-Monroy, M.; López Meyer, M.; Montes-Belmont, R.; Sepulveda-Jimenez, G. Trichoderma asperellum ameliorates phytotoxic effects of copper in onion (Allium cepa L.). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 136, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.Q.; Meng, M.; Wu, L.R.; Zheng, X.M.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Dai, S.H. Function and mechanism of polysaccharide on enhancing tolerance of Trichoderma asperellum under Pb2+ stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeed, A.H.A.; Mahdy, R.E.; Alshehri, D.; Hammami, I.; Eissa, M.A.; Latef, A.A.H.A.; Mahmoud, G.A.E. Induction of resilience strategies against biochemical deteriorations prompted by severe cadmium stress in sunflower plant when Trichoderma and bacterial inoculation were used as biofertilizers. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1004173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanullah, F.; Khan, W. Trichoderma asperellum L. Coupled the Effects of Biochar to Enhance the Growth and Physiology of Contrasting Maize Cultivars under Copper and Nickel Stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaf, M.; Ilyas, T.; Shahid, M.; Shafi, Z.; Tyagi, A.; Ali, S. Trichoderma Inoculation Alleviates Cd and Pb-Induced Toxicity and Improves Growth and Physiology of Vigna radiata (L.). ACS Omega 2024, 9, 8557–8573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.G.; Shea, P.J.; Oh, B.T. Trichoderma sp. PDR1-7 promotes Pinus sylvestris reforestation of lead-contaminated mine tailing sites. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 476-477, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jam, E.; Khomari, S.; Ebadi, A.; Goli-Kalanpa, E.; Ghavidel, A. Correction to: Influences of peanut hull-derived biochar, Trichoderma harzianum and supplemental phosphorus on hairy vetch growth in Pb- and Zn-contaminated soil. Environ. Geochem. Hlth. 2023, 45, 9433–9434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.W.; Sharif, R.; Xu, X.W.; Chen, X.H. Mechanisms of Waterlogging Tolerance in Plants: Research Progress and Prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 627331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkelish, A.A.; Alhaithloul, H.A.S.; Qari, S.H.; Soliman, M.H.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Pretreatment with Trichoderma harzianum alleviates waterlogging-induced growth alterations in tomato seedlings by modulating physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 171, 103946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.F.; Jiang, F.L.; Yin, J.; Wang, Y.L.; Li, Y.K.; Yu, X.Q.; Song, X.M.; Ottosen, M.R.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, R.; Rosenqvist, E.; Mittler, R. ROS-mediated waterlogging memory, induced by priming, mitigates photosynthesis inhibition in tomato under waterlogging stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1238108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, M.; Awais, M.; Ud-Din, A.; Ali, K.; Gul, H.; Rahman, M.M.; Hamayun, M.; Arif, M. Molecular Mechanisms of the 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylic Acid (ACC) Deaminase Producing Trichoderma asperellum MAP1 in Enhancing Wheat Tolerance to Waterlogging Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 614971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, R.S.; Kim, Y.O.; Cho, S.; Mercer, M.; Rienstra, M.; Manglona, R.; Biaggi, T.; Zhou, X.G.; Chilvers, M.; Gray, Z.; Rodriguez, R.J.; Egamberdieva, D. A Symbiotic Approach to Generating Stress Tolerant Crops. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chunyan, L.I.U.; Yujie, Y.A.N.G.; Qiangsheng, W.U.; Yeyun, L.I. Plant Root Hair Growth in Response to Hormones. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2019, 47, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yuan, D.; Hu, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y. Effects of mycorrhizal fungi on plant growth, nutrient absorption and phytohormones levels in tea under shading condition. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2020, 48, 2006–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, B.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, D.; Liu, C.; Wu, Q.; Luo, C. Genome-wide identification of citrus histone acetyltransferase and deacetylase families and their expression in response to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and drought. J. Plant Interact. 2021, 16, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, D.; Deng, X. Phosphorus-induced change in root hair growth is associated with IAA accumulation in walnut. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2021, 49, 12504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Gong, T.i.; Li, M.; Hu, C.; Zhang, D.; Sun, M. Root hair specification and its growth in response to nutrients. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2021, 49, 12258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Hui, X.; Tong, C.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, D. The Physiological and Molecular Responses of Exogenous Selenium to Selenium Content and Fruit Quality in Walnut. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 92, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, B.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, D.; Liu, C.; Wu, Q.; Luo, C. Genome-wide identification of citrus calmodulin-like genes and their expression in response to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonization and drought. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2022, 102, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, P.; Zha, Q.; Hui, X.; Tong, C.; Zhang, D. Research Progress of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Improving Plant Resistance to Temperature Stress. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Jin, L.F.; Tong, C.L.; Liu, F.; Huang, B.; Zhang, D.J. Research Progress on the Growth-Promoting Effect of Plant Biostimulants on Crops. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 93, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Zhou, X.; Tong, C.; Zhang, D. The Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Fruit Cracking Alleviation by Exogenous Calcium and GA3 in the Lane Late Navel Orange. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.-J.; Tong, C.-L.; Wang, Q.-S.; Bie, S. Mycorrhizas Affect Physiological Performance, Antioxidant System, Photosynthesis, Endogenous Hormones, and Water Content in Cotton under Salt Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Tong, C.; Zhang, D. Effects and Mechanism of Auxin and Its Inhibitors on Root Growth and Mineral Nutrient Absorption in Citrus (Trifoliate Orange, Poncirus trifoliata) Seedlings via Its Synthesis and Transport Pathways. Agronomy 2025, 15, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.H.; Li, H.; Tong, C.L.; Zhang, D.J.; Lu, Y.M. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal the effect of mycorrhizal colonization on trifoliate orange root hair. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 336, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zheng, J.; Yi, Q. Effects of Exogenous Trehalose on Plant Growth, Physiological and Biochemical Responses in Gardenia jasminoides Seedlings During Cold Stress. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Tong, C.; Zhang, D. Effects of exogenous melatonin on plant growth, root hormones and photosynthetic characteristics of trifoliate orange subjected to salt stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 97, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, F.; Hu, W.; Gong, S.; Wu, Q. Auxin modulates root-hair growth through its signaling pathway in citrus. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 236, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Yuan, S.; Tong, C.; Zhang, D.; Huang, R. Ethylene modulates root growth and mineral nutrients levels in trifoliate orange through the auxin-signaling pathway. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2023, 51, 13269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crop | Trichoderma | Environment | Key function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus aurantifolia | T. harzianum | No stress | The secretion of IAA and cytokinin increased the plant height, branch number, leaf area, and absolute growth rate. | [23] |

| Cucumber | T.harzianum | Salt stress | Increase the contents of proline, soluble sugars, soluble proteins, and chlorophyll. Enhance root activity, inhibit the absorption of Na+, and promote the absorption of K+. | [24] |

| Arabidopsis | T.viride | Salt stress | Enhance root development, improve plant IAA levels, and plant antioxidant capacity and osmotic protection. | [25] |

| Wheat | T. longibrachiatum | Salt stress | Promote seed germination, increase shoot and root weight, enhance Pro content, POD and APX enzyme activities, and reduce MDA content. | [26] |

| Tomato | T. harzianum | Drought stress | Increase the fresh and dry weights of roots and shoots, and enhance the enzymatic activities of SOD, CAT, and APX. | [27] |

| Sugarcane | T. harzianum | Drought stress | Increase the content of chlorophyll, carotenoids, sugar, improve photosynthesis rate, stomatal conductance, and water use efficiency. | [28] |

| Maize | T. harzianum | Cold stress | Produce growth regulators (such as auxin, cytokinin) to promote germination, root growth, and plant biomass. | [29] |

| Cicer arietinum | Trichoderma strain M-35 | Heavy metal stress | The methylation of arsenic in soil reduced the absorption of arsenic by plants, and the down-regulation of genes (MIPS, PGIP, CGG) enhanced the potential of plants to cope with As stress. | [30] |

| Maize | T. asperellum strain T34 | Drought stress | It improved grain P and C, grain number and dry weight, and increased leaf relative water content, water use efficiency, PSII maximum efficiency, and photosynthesis. | [31] |

| Strawberry | T. harzianum | No stress | Promote fruit development, increase yield, and enhance the accumulation of anthocyanins, and other antioxidants in fruits. | [32] |

| Lycium chinense | T. asperellum | Salt stress | Enhance the accumulation of nitrogen, dry matter, and biomass, and increase the activities of NR, NIR, and GS in roots and leaves. | [33] |

| Tomato | T. harzianum | Cold stress | It enhanced the expression of TAS14 (regulating ABA signaling pathway to enhance water retention capacity) and P5CS (catalyzes proline synthesis, maintains cell osmotic pressure), boosted the photosynthesis and growth rates, decreased the rate of lipid peroxidation and electrolyte leakage, and simultaneously increased the leaf water content and proline accumulation. | [34] |

| Groundnut | T. harzianum | Salt stress | IAA was produced, phenolic substances and flavonoids increased by 31% and 43%, photosynthesis was enhanced, chlorophyll content, bud and biomass weight were increased. | [35] |

| Wheat | T. reesei | Salt stress | Reduce the toxicity of ROS in cells and increase the content of IAA, GA, Ca, and K. | [36] |

| Sweet sorghum | T. harzianum | Salt stress | The yield, plant height, stem diameter and total sugar content in stem were increased by 35.52 %, 32.68 %, 32.09 %, and 36.82 %, respectively. | [37] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).