Submitted:

30 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

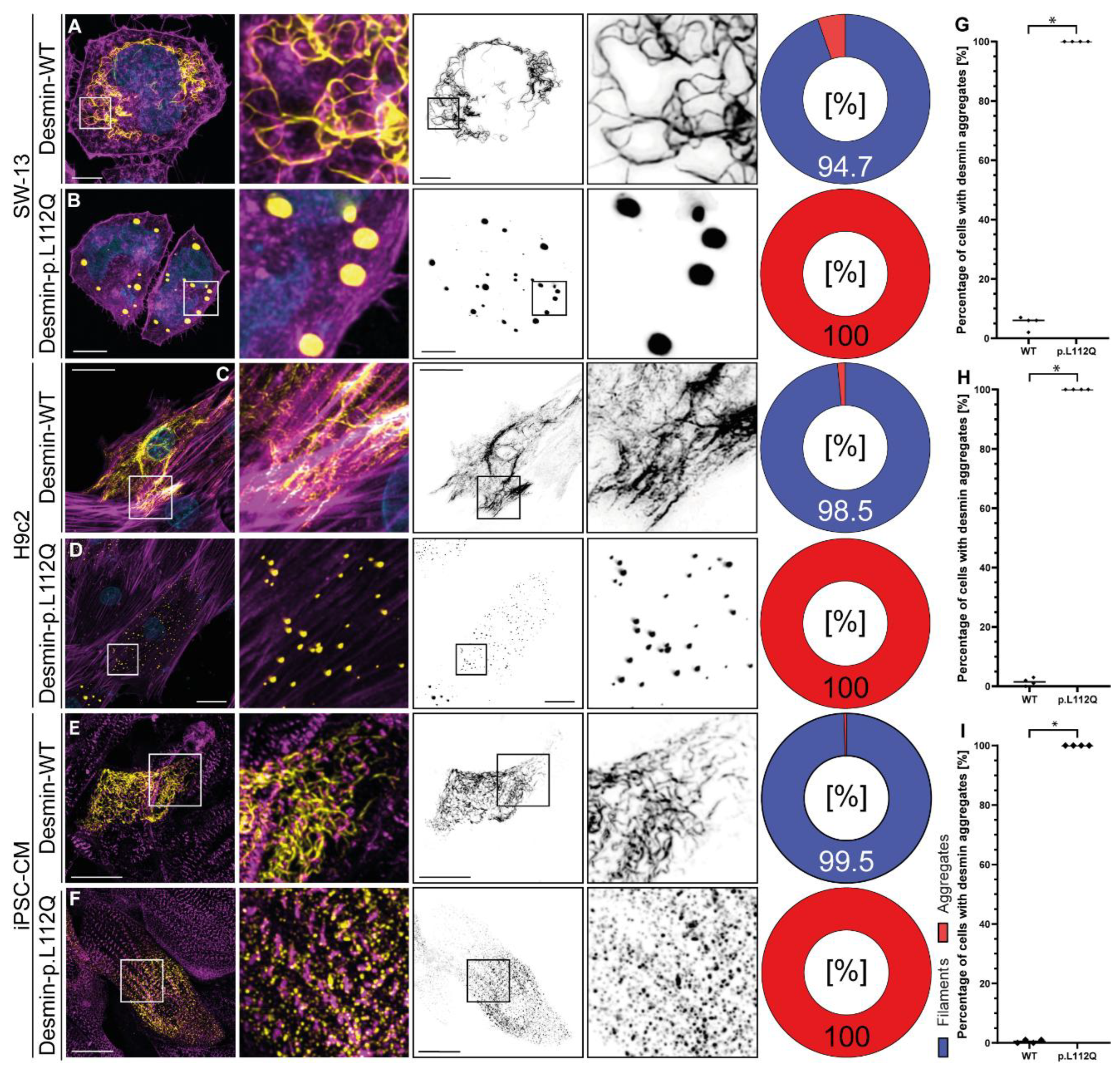

DES encodes the muscle specific intermediate filament protein desmin and mutations in this gene cause different cardiomyopathies. Here, we functionally validate DES-p.L112Q using SW-13, H9c2 cells and cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells by confocal microscopy. These experiments reveal an aberrant cytoplasmic aggregation of mutant desmin. In conclusion, these functional analyses support the re-classification of DES-p.L112Q as a likely pathogenic variant leading to dilated cardiomyopathy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmid Generation

2.2. Cell Culture and Transfection

2.3. Differentiation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells into Cardiomyocytes

2.4. Fixation and Staining

2.5. Confocal Microscopy

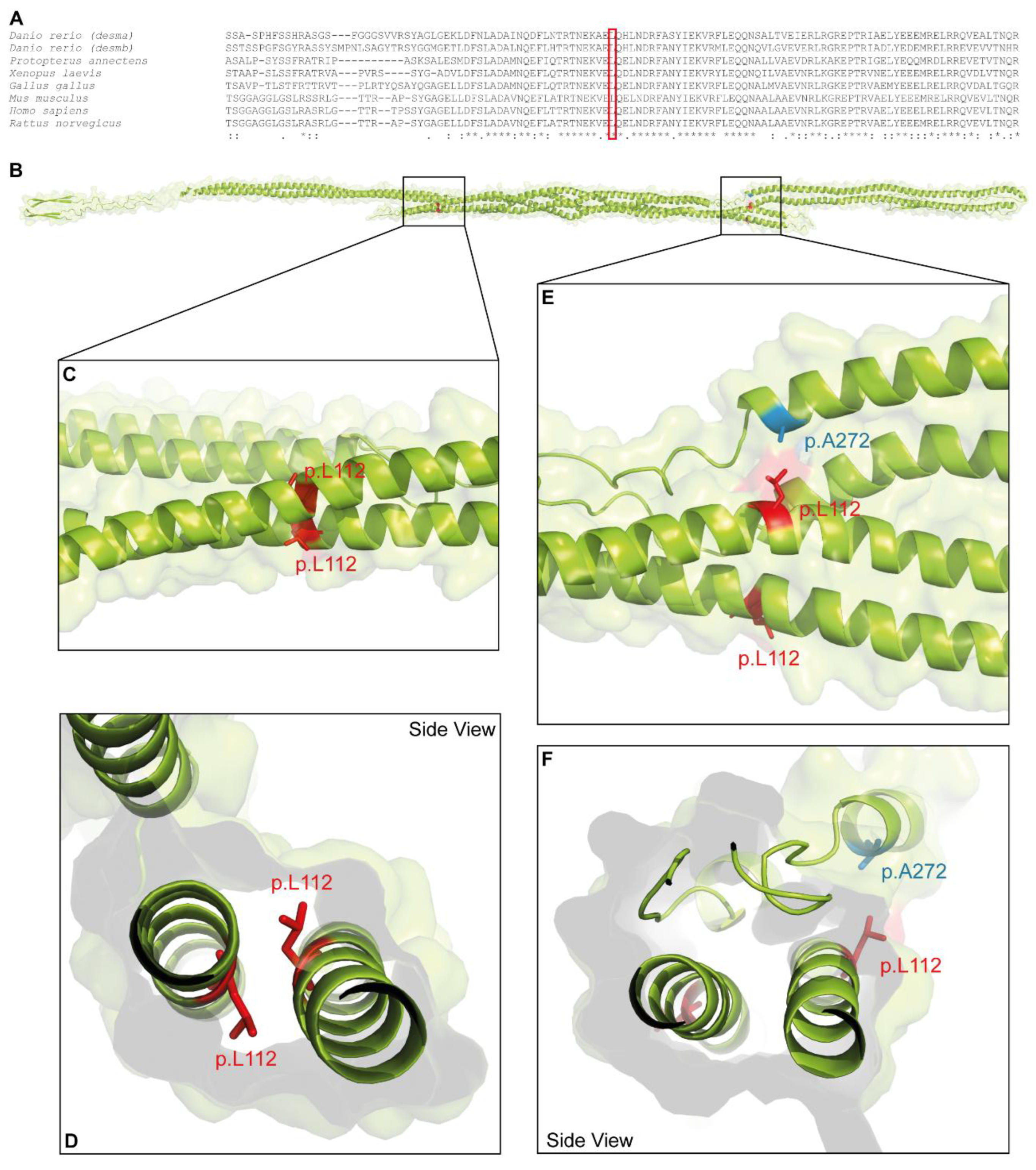

2.6. Molecular Desmin Model

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| DCM | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| iPSCs | Induced pluripotent stem cells |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| RT | Room temperature |

| VUS | Variant of Unknown Signficance |

References

- Q. , X.G.C.L.L.L.X.G.D.Y.L.J.L.X.W. Genetic Profiling and Phenotype Spectrum in a Chinese Cohort of Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Patients. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 466. [Google Scholar]

- Brodehl, A.; Holler, S.; Gummert, J.; Milting, H. The N-Terminal Part of the 1A Domain of Desmin Is a Hot Spot Region for Putative Pathogenic DES Mutations Affecting Filament Assembly. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Lilienbaum, A.; Butler-Browne, G.; Paulin, D. Human desmin-coding gene: Complete nucleotide sequence, characterization and regulation of expression during myogenesis and development. Gene 1989, 78, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalakas, M.C.; Park, K.Y.; Semino-Mora, C.; Lee, H.S.; Sivakumar, K.; Goldfarb, L.G. Desmin myopathy, a skeletal myopathy with cardiomyopathy caused by mutations in the desmin gene. N Engl J Med 2000, 342, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodehl, A.; Gaertner-Rommel, A.; Milting, H. Molecular insights into cardiomyopathies associated with desmin (DES) mutations. Biophys Rev 2018, 10, 983–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, L.G.; Dalakas, M.C. Tragedy in a heartbeat: Malfunctioning desmin causes skeletal and cardiac muscle disease. J Clin Invest 2009, 119, 1806–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauke, B.; Kossmann, S.; Gaertner, A.; Brand, K.; Stork, I.; Brodehl, A.; Dieding, M.; Walhorn, V.; Anselmetti, D.; Gerdes, D.; et al. De novo desmin-mutation N116S is associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet 2010, 19, 4595–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernengo, L.; Chourbagi, O.; Panuncio, A.; Lilienbaum, A.; Batonnet-Pichon, S.; Bruston, F.; Rodrigues-Lima, F.; Mesa, R.; Pizzarossa, C.; Demay, L.; et al. Desmin myopathy with severe cardiomyopathy in a Uruguayan family due to a codon deletion in a new location within the desmin 1A rod domain. Neuromuscul Disord 2010, 20, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Voß, S.; Milting, H. Desmin-p. Y122S affects the filament formation and causes aberrant cytoplasmic desmin aggregation. Human Gene 2024, 41, 201299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Hedde, P.N.; Dieding, M.; Fatima, A.; Walhorn, V.; Gayda, S.; Saric, T.; Klauke, B.; Gummert, J.; Anselmetti, D.; et al. Dual color photoactivation localization microscopy of cardiomyopathy-associated desmin mutants. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 16047–16057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Dieding, M.; Klauke, B.; Dec, E.; Madaan, S.; Huang, T.; Gargus, J.; Fatima, A.; Saric, T.; Cakar, H.; et al. The novel desmin mutant p.A120D impairs filament formation, prevents intercalated disk localization, and causes sudden cardiac death. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013, 6, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protonotarios, A.; Brodehl, A.; Asimaki, A.; Jager, J.; Quinn, E.; Stanasiuk, C.; Ratnavadivel, S.; Futema, M.; Akhtar, M.M.; Gossios, T.D.; et al. The Novel Desmin Variant p.Leu115Ile Is Associated With a Unique Form of Biventricular Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Can J Cardiol 2021, 37, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, M.A.; Ali, N.M.; Albash, B.Y.; Al Sayegh, A.H.; Ahmad, N.B.; Voss, S.; Klag, F.; Gross, J.; Holler, S.; Walhorn, V.; et al. Phenotypic Diversity Caused by the DES Missense Mutation p.R127P (c.380G>C) Contributing to Significant Cardiac Mortality and Morbidity Associated With a Desmin Filament Assembly Defect. Circ Genom Precis Med 2025, 18, e004896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, X.; Zhang, J.; Azarin, S.M.; Zhu, K.; Hazeltine, L.B.; Bao, X.; Hsiao, C.; Kamp, T.J.; Palecek, S.P. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat Protoc 2013, 8, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, S.; Milting, H.; Klag, F.; Semisch, M.; Holler, S.; Reckmann, J.; Goz, M.; Anselmetti, D.; Gummert, J.; Deutsch, M.A.; et al. Atlas of Cardiomyopathy Associated DES (Desmin) Mutations: Functional Insights Into the Critical 1B Domain. Circ Genom Precis Med 2025, e005358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eibauer, M.; Weber, M.S.; Kronenberg-Tenga, R.; Beales, C.T.; Boujemaa-Paterski, R.; Turgay, Y.; Sivagurunathan, S.; Kraxner, J.; Koster, S.; Goldman, R.D.; et al. Vimentin filaments integrate low-complexity domains in a complex helical structure. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2024, 31, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, K.K.; Chen, L.B. Absence of intermediate filaments in a human adrenal cortex carcinoma-derived cell line. Exp Cell Res 1986, 163, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hescheler, J.; Meyer, R.; Plant, S.; Krautwurst, D.; Rosenthal, W.; Schultz, G. Morphological, biochemical, and electrophysiological characterization of a clonal cell (H9c2) line from rat heart. Circ Res 1991, 69, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brnich, S.E.; Abou Tayoun, A.N.; Couch, F.J.; Cutting, G.R.; Greenblatt, M.S.; Heinen, C.D.; Kanavy, D.M.; Luo, X.; McNulty, S.M.; Starita, L.M.; et al. Recommendations for application of the functional evidence PS3/BS3 criterion using the ACMG/AMP sequence variant interpretation framework. Genome Med 2019, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).