Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample Population

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive data and Sample Distribution

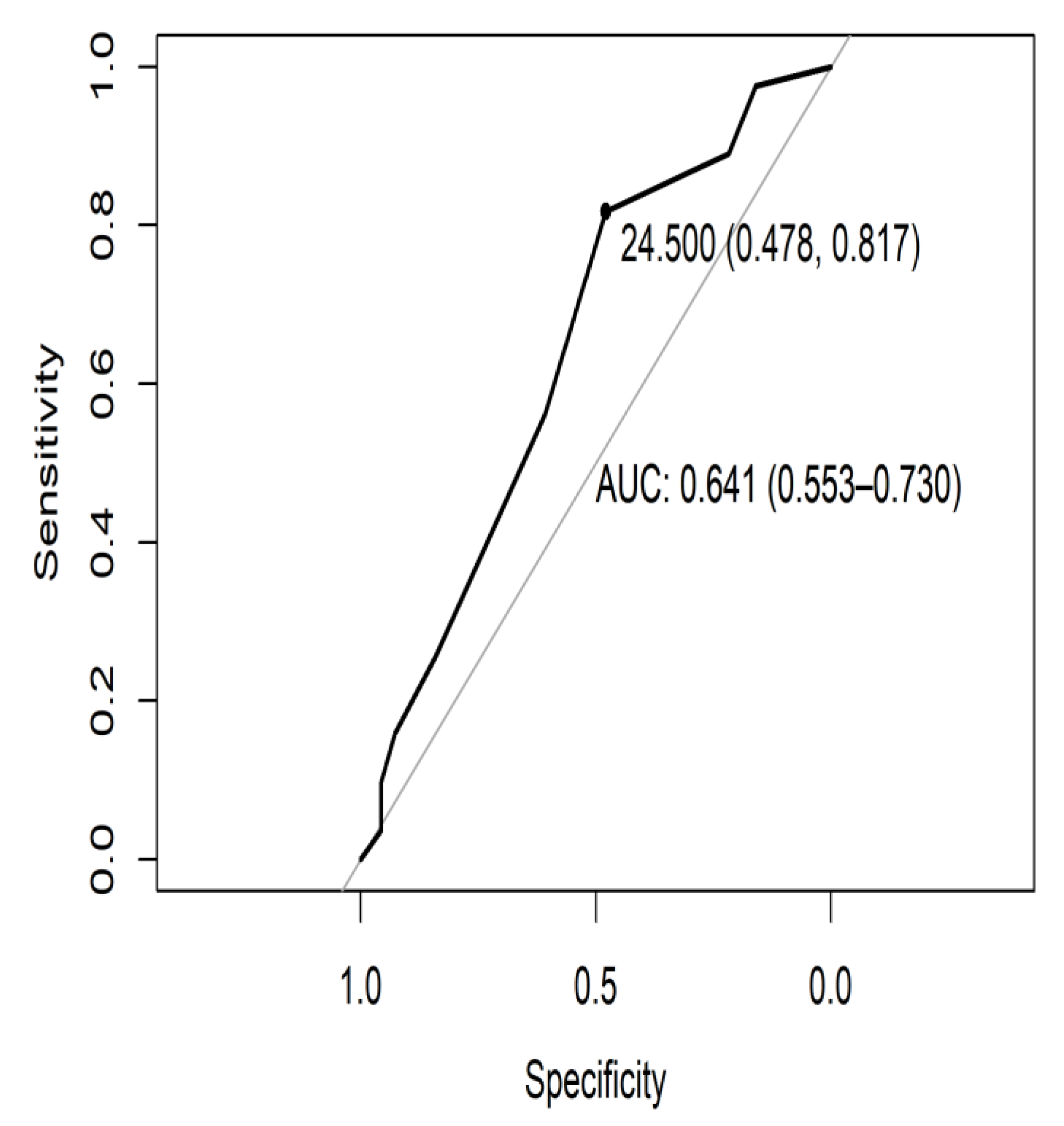

3.2. Internal Consistency, Prevalence of Impairment, and ROC Curve of the TYM-MCI

3.3. Correlation Analysis Between Cognitive Tests

3.4. Sensitivity and Specificity by Cognitive Domains

3.5. Principal Components Analysis (PCA). State Variables

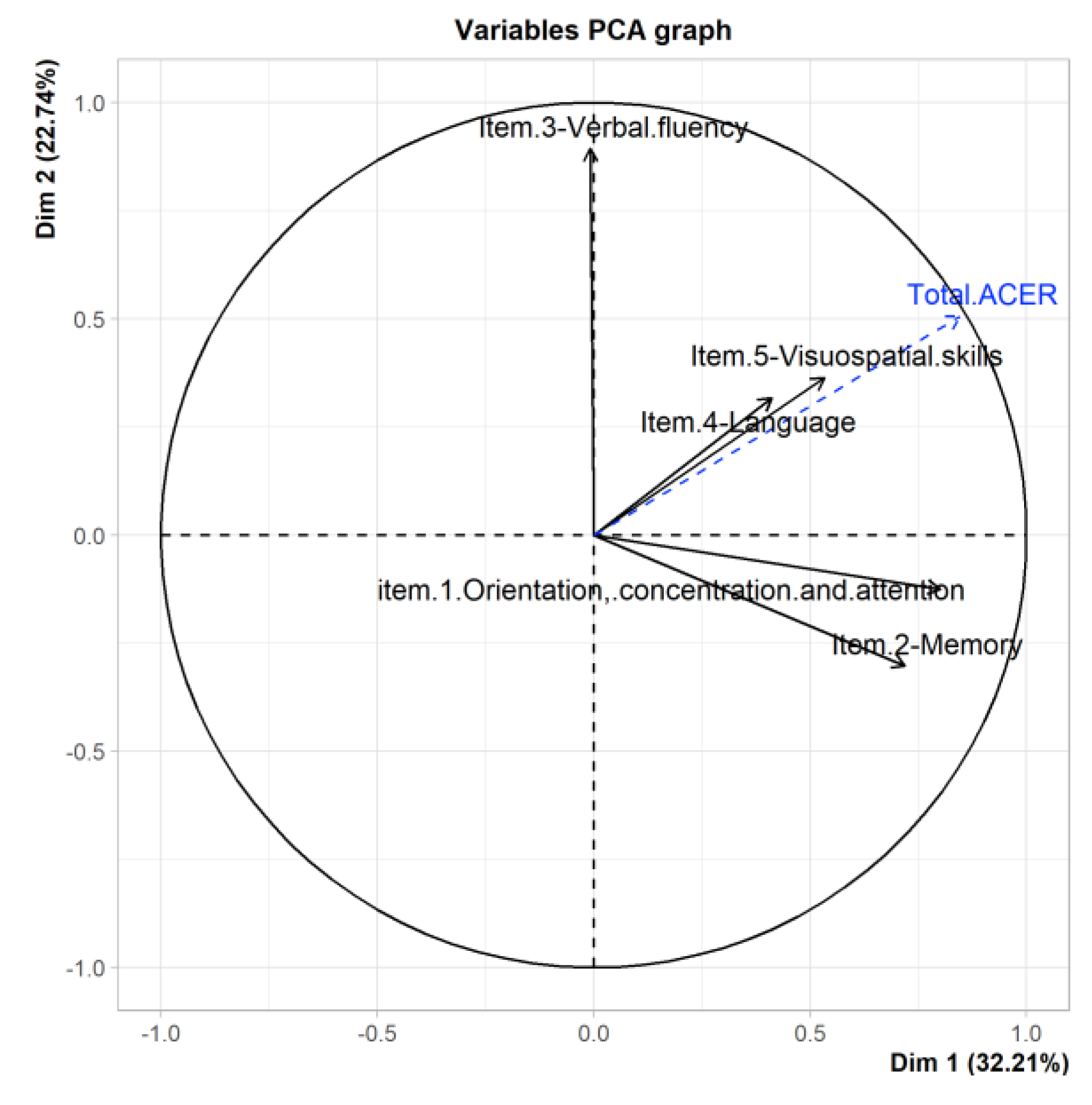

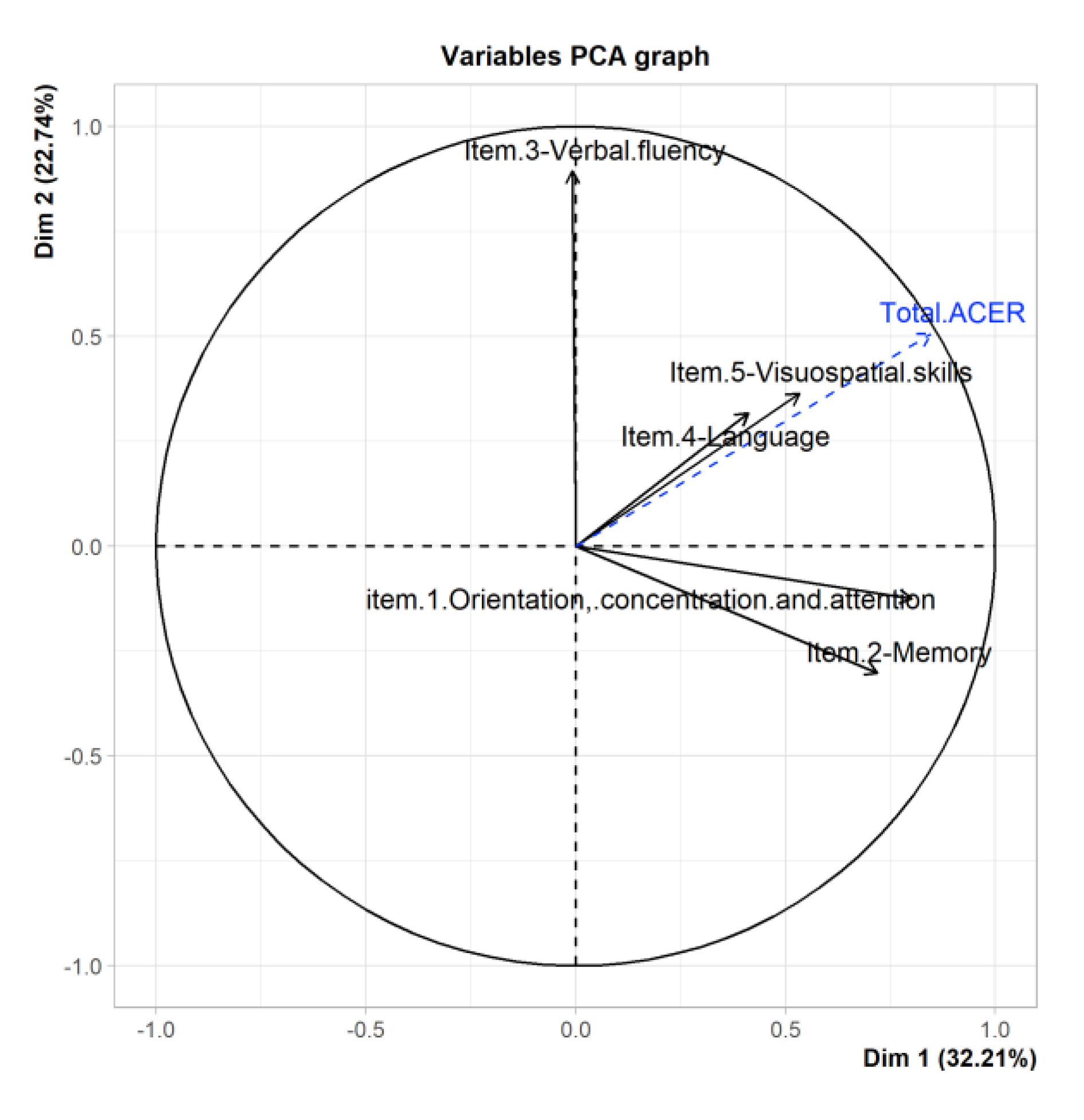

3.6. PCA Del ACE-R

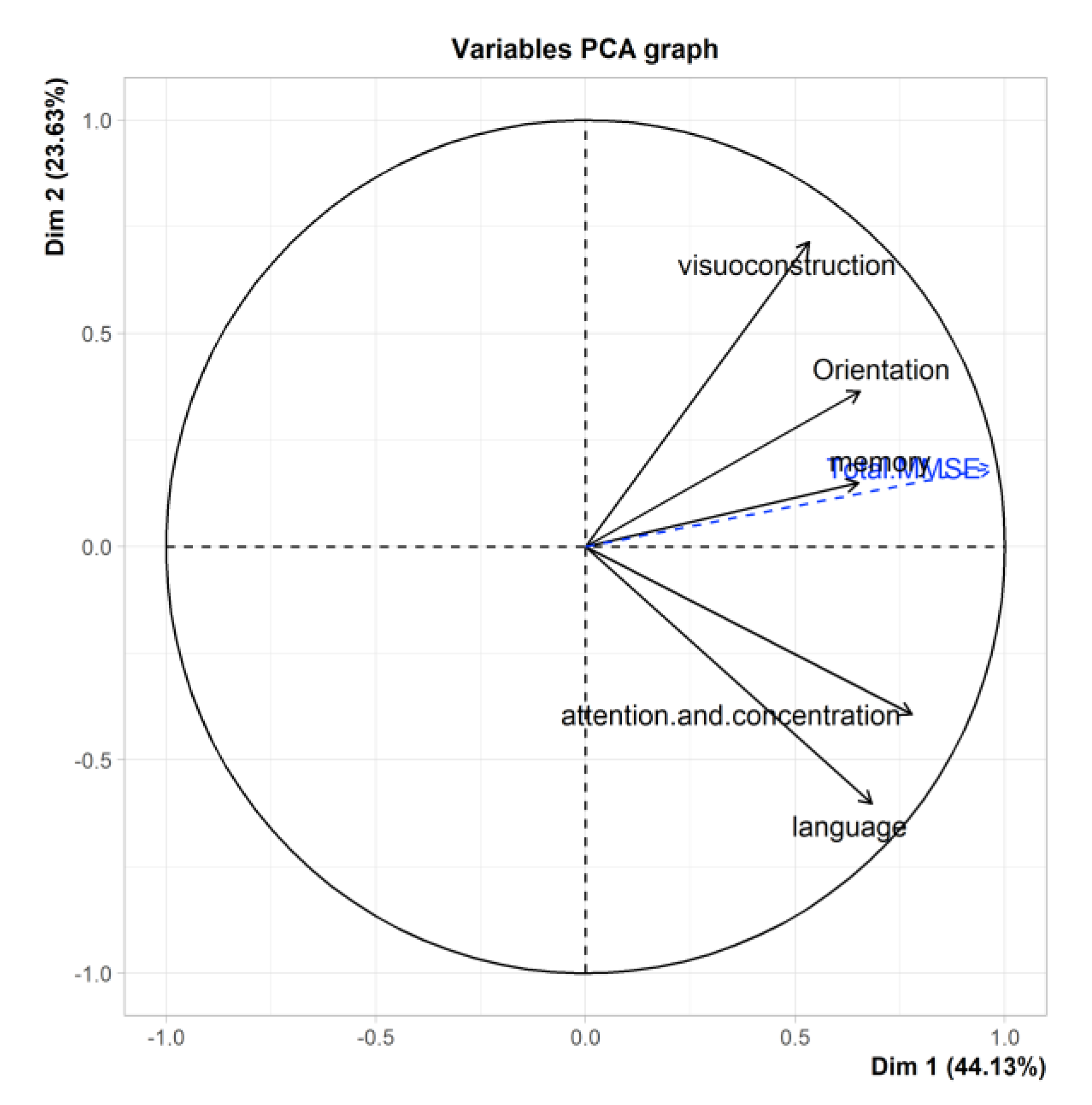

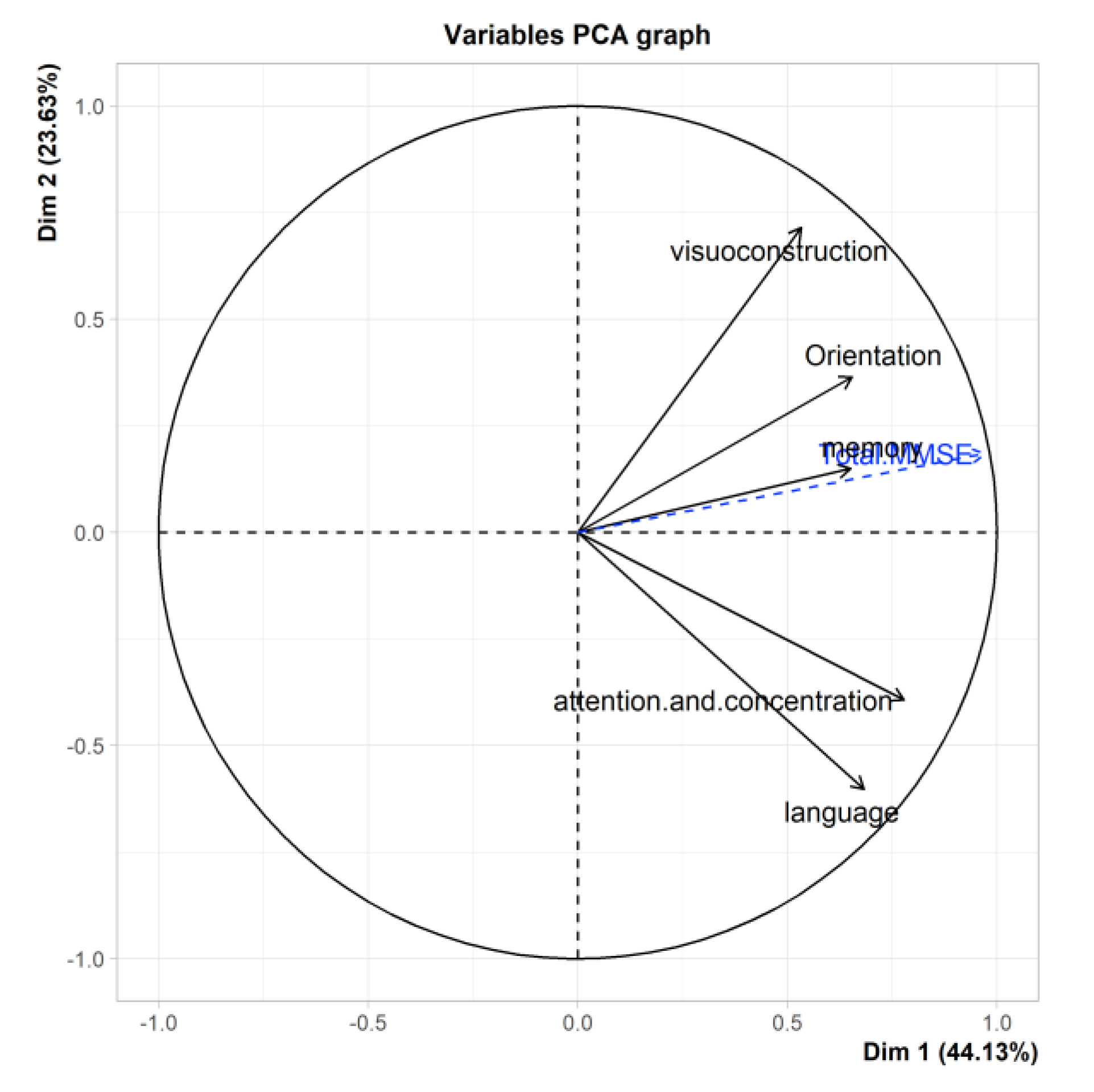

3.7. PCA of the MMSE

3.8. PCA of the TYM-S

3.9. PCA of the TYM-MCI

4. Discussion

4.1. Global Analyses

4.2. Analysis of the Relationship Between Cognitive Tests Regarding Episodic Memory

4.3. Does the TYM-MCI Effectively Assess Episodic Memory Compared to Other Tests?

5. Conclusions

5.1. General Conclusion

5.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cowan, E.T.; Schapiro, A.C.; Dunsmoor, J.E.; Murty, V.P. Memory consolidation as an adaptive process. Psychonomic bulletin & review 2021, 28, 1796–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, W.E.; Scott, T.M.; Duffy, J.; Whitmer, R.A.; Chesney, M.A.; Boscardin, W.J.; Barnes, D.E. Dyadic Group Exercises for Persons with Memory Deficits and Care Partners: Mixed-Method Findings from the Paired Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIÉ) Randomized Trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 78, 1689–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, M.; Tahiri, J.; Eldin, R.; Altabaa, M.; Sehar, U.; Reddy, P.H. Overlooked cases of mild cognitive impairment: Implications to early Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Research Reviews 2024, 98, 102335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garre-Olmo. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Neurology Journal 2018, 66, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.D. State of the science on mild cognitive impairment (MCI). CNS Spectrums 2019, 24, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud. Plan nacional de demencia. Ministerio de Salud 2017. https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/PLAN-DE-DEMENCIA.pdf.

- Mowszowski, L.; Lampit, A.; Walton, C.C.; Naismith, S.L.; Valenzuela, M. The role of memory interventions in mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Neuropsychology Review 2022, 32, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulving, E. Episodic memory: from mind to brain. Annual Review of Psychology 2002, 53, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovitch, M.; Cabeza, R.; Winocur, G.; Nadel, L. Episodic Memory and Beyond: The Hippocampus and Neocortex in Transformation. Annual Review of Psychology 2016, 67, 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonelinas, A.; Hawkins, C.; Abovian, A.; Aly, M. The role of recollection, familiarity, and the hippocampus in episodic and working memory. Neuropsychologia 2024, 193, 108777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, M.; Teng Koh, M. Episodic memory on the path to Alzheimer’s disease. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2011, 21, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2020, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Hampel, H.; Feldman, H.H.; et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: Definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2016, 12, 292–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Barve, K.H.; Kumar, M.S. Recent advancements in pathogenesis, diagnostics and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Current Neuropharmacology 2020, 18, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G.; Quaranta, D.; Vita, M.G.; Marra, C. Neuropsychological predictors of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD 2014, 38, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Jacova; et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. The Lancet Neurology 2014, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis, Z.; Shah, R.; Bennett, D. Diagnosis and management of dementia: review. Journal of the American Medical Association 2019, 322, 1589–1599, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31638686/. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, D.; Slachevsky, A.; Fiorentino, N.; Rueda, D.; Bruno, G.; Tagle, A.; Olavarría, L.; Flores, P.; Lillo, P.; Roca, M.; Torralva, T. Validación argentino-chilena de la versión en español del test Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III para el diagnóstico de demencia. Neurología 2020, 35, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Neira, C.; Ihnen, J.; Flores, P.; Henriquez, F.; Sánchez, M.; Slachevsky, A. Propiedades psicométricas y utilidad diagnóstica del Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R) en una muestra de ancianos chilenos. Revista Médica Chile 2012, 140, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Wiggins, J.; Dawson, K.; Rittman, T.; Rowe, J. Test Your Memory (TYM) and Test Your Memory for Mild Cognitive Impairment (TYM-MCI): a review and update including results of using the TYM test in a general neurology clinic and using a telephone version of the TYM test. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Lansdall, C.; Wiggins, J.; Dawson, K.; Hunter, K.; Rowe, J.; Parker, R. The Test Your Memory for Mild Cognitive Impairment (TYM-MCI). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 2017, 88, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Zande, E.; Van de Nes, J.; Jansen, I.; Van den Berg, M.; Zwart, A.; Bimmel, D.; Rijkers, G.; Andringa, G. The Test Your Memory (TYM) test outperforms the MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia. Current Alzheimer Research 2017, 14, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Lario, P.; Azcárate-Jiménez, L.; Seijas-Gómez, R.; Tirapu-Ustárroz, J. Propuesta de una batería neuropsicológica de evaluación cognitiva para detectar y discriminar deterioro cognitivo leve y demencias. Rev Neurol 2015, 60, 553–561, https://psicogerontologia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Propuesta-de-bateria-neuropsicologica.pdf. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Neira, C.; Chaparro, F.; Delgado, C.; Brown, J.; Slachevsky, A. Test Your Memory-Spanish version (TYM-S): a validation study of a self-administered cognitive screening test. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2014, 29, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larner, A. Hard-TYM: a pragmatic study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2015, 30, 330–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Wiggins, J.; Dong, H.; Harvey, R.; Richardson, F.; Hunter, K.; Dawson, K.; Parker, R.A. The hard Test Your Memory. Evaluation of a short cognitive test to detect mild Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2014, 29, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Síntesis de resultados Censo 2017. 2018. http://resultados.censo2017.cl/.

- Servicio Nacional del Adulto Mayor [SENAMA]. Envejecimiento en Chile: evolución y características de las personas mayores. Gobierno de Chile 2022. https://www.senama.gob.cl/storage/docs/Envejecimiento-en-Chile-2022.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Chile [Country overview]. data.who.int 2025. (Accessed on 30 July 2025). Disponible en: https://data.who.int/countries/152.

- Leiva, A.M.; Troncoso-Pantoja, C.; Martínez-Sanguinetti, M.A.; et al. Las personas mayores en Chile: el nuevo desafío social, económico y de salud del siglo XXI. Rev Méd Chile 2020, 148, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Vernuccio, L.; Catanese, G.; Inzerillo, F.; Salemi, G.; Barbagallo, M. Nutrition, physical activity, and other lifestyle factors in the prevention of cognitive decline and dementia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, R.C.; Pavlou, M.; Schilder, A.G.M.; Bamiou, D.E.; Lewis, G.; Lin, F.R.; Livingston, G.; Proctor, D.; Omar, R.; Costafreda, S.G. Early detection and management of hearing loss to reduce dementia risk in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: findings from the treating auditory impairment and cognition trial (TACT). Age Ageing. 2025, 54(1), afaf004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Sumerlin, T.S.; Goggins, W.B.; Kwong, E.M.S.; Leung, J.; Yu, B.; Kwok, T.C.Y. Does low subjective social status predict cognitive decline in Chinese older adults? A 4-year longitudinal study from Hong Kong. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2021, 29, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Jacova, C.; et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. The Lancet Neurology 2014, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, M.P. Metodología de la investigación (6ª ed.). McGraw-Hill, 2014.

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, M.; Alinaghipour, A.; Daneshvar, R.; et al. Adapted MMSE and TYM cognitive tests: how much powerful in screening for Alzheimer’s disease in Iranian people. Aging & Mental Health 2020, 24, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, L.P.; Albala, C.; Klaasen, P.G. Validación de un test de tamizaje para el diagnóstico de demencia asociada a edad, en Chile. Rev Méd Chile 2004, 132, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Barrés, S.; García-Barco, M.; Basora, J.; et al. The efficacy of a nutrition education intervention to prevent risk of malnutrition for dependent elderly patients receiving Home Care: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2017, 70, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.R. Tests psicológicos y evaluación (11ª ed.). Pearson Educación, 2003.

- Martínez Pérez, J.A.; Pérez Martin, P.S. La curva ROC [ROC curve]. Semergen 2023, 49, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Fernández, C.; Custodio, N.; Soto-Añari, M. Neuropsychological profile in the preclinical stages of dementia: principal component analysis approach. Dement Neuropsychol 2021, 15, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toloza Ramírez, D.; Martella, D. Reserva cognitiva y demencias: Limitaciones del efecto protector en el envejecimiento y el deterioro cognitivo. Rev Méd Chile 2019, 147, 1594–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, L.M.J. La estimulación cognitiva en personas adultas mayores. Rev Cúpula 2007, 11, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nahm, F.S. Receiver operating characteristic curve: overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J Anesthesiol 2022, 75, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarazin, M.; Berr, C.; De Rotrou, J.; et al. Amnestic syndrome of the medial temporal type identifies prodromal AD: a longitudinal study. Neurology 2007, 69, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainotti, G.; Quaranta, D.; Vita, M.G.; Marra, C. Verbal vs. visual memory in Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analytical review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014, 85, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzikostopoulos, A.; Moraitou, D.; Tsolaki, M.; et al. Episodic Memory in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI) and Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia (ADD): Using the “Doors and People” Tool to Differentiate between Early aMCI-Late aMCI-Mild ADD Diagnostic Groups. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Neira, C.; López, O.L.; Riveros, R.; et al. The technology - activities of daily living questionnaire: a version with a technology-related subscale. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2012, 33, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhla, M.Z.; Banuelos, D.; Pagán, C.; et al. Differences between episodic and semantic memory in predicting observation-based activities of daily living in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2022, 29, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haj, M.; Colombel, F.; Kapogiannis, D.; Gallouj, K. False memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Behavioural Neurology 2020, 2020, 5284504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamoon, M.S.; Cheung, Y.K.; Gutierrez, J.; et al. Functional trajectories, cognition, and subclinical cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 2018, 49, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Añari, M.; Custodio, N.; Rivera-Fernández, C. Validación de instrumentos breves para deterioro cognitivo en adultos mayores. Rev Chilena de Neuropsicología 2020, 15, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haj, M.; Antoine, P.; Amouyel, P.; Lambert, J.; Pasquier, F.; Kapogiannis, D.; Apolipoprotein, E. (APOE) ε4 and episodic memory decline in Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Ageing Res Rev 2016, 27, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungas, D.; Fletcher, E.; Gavett, B.E.; et al. Comparison of education and episodic memory as modifiers of brain atrophy effects on cognitive decline: implications for measuring cognitive reserve. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2021, 27, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollinedo Cardalda, I.; López, A.; Cancela Carral, J.M. The effects of different types of physical exercise on physical and cognitive function in frail institutionalized older adults with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2019, 83, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Bermúdez, S.; Restrepo de Mejía, F. Evaluación neuropsicológica de la memoria episódica. Edupsykhé Rev Psicol Educ 2023, 20, 24–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihnen-Jory, J.I.; Bruna, A.A.; Muñoz-Neira, C.; Chonchol, A.S. Chilean version of the INECO Frontal Screening (IFS-Ch): psychometric properties and diagnostic accuracy. Dement Neuropsychol 2013, 7, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbordone, R.J. Ecological validity: some critical issues for the neuropsychologist. In: Sbordone RJ, Long CJ (eds). St. Lucie Press, 1998. [CrossRef]

- García-Molina, A.; Tirapu Ustárroz, J.; Roig Rovira, T. Validez ecológica en la exploración de las funciones ejecutivas. An Psicol 2007, 23, 289–299, https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/167/16723216.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Femir-Gurtuna, B.; Kurt, E.; Ulasoglu-Yildiz, C.; et al. White-matter changes in early and late stages of mild cognitive impairment. J Clin Neurosci 2020, 78, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demonty, M.; Coppalle, R.; Bastin, C.; Geurten, M. The use of distraction to improve episodic memory in ageing: a review of methods and theoretical implications. Can J Exp Psychol 2023, 77, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alantie, S.; Tyrkkö, J.; Makkonen, T.; Renvall, K. Is old age just a number in language skills? Language performance and its relation to age, education, gender, cognitive screening, and dentition in very old Finnish speakers. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2022, 65, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Losada, M.L.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; Lopez-Higes, R.; et al. How cognitive reserve influences older adults’ cognitive state, executive functions and language comprehension: a structural equation model. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2019, 84, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arévalo-Rodríguez, I.; Smailagic, N.; Roqué IFiguls, M.; Ciapponi, A.; Sánchez-Pérez, E.; Giannakou, A.; Pedraza, O.L.; Bonfill Cosp, X.; Cullum, S. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2015, 3, CD010783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunette, A.M.; Calamia, M.; Black, J.; Tranel, D. Is episodic future thinking important for instrumental activities of daily living? A study in neurological patients and healthy older adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2019, 34, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didic, M.; Barbeau, E.J.; Felician, O.; et al. Which memory system is impaired first in Alzheimer’s disease? J Alzheimers Dis 2011, 27, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ptje.* | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| 27.5 | 0.976 | 0.159 |

| 26.5 | 0.890 | 0.217 |

| 25.5 | 0.866 | 0.304 |

| 24.5 | 0.817 | 0.478 |

| 23.5 | 0.561 | 0.609 |

| 22.5 | 0.256 | 0.841 |

| 21.5 | 0.159 | 0.928 |

| 20.5 | 0.098 | 0.957 |

| 19.5 | 0.073 | 0.957 |

| 18.5 | 0.037 | 0.957 |

| Episodic Memory | Global Cognitive | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACER | MMSE | TYM | TYM-MCI | ACER | MMSE | TYM | TYM-MCI | |||

| Accuracy | .702 | .238 | .623 | .675 | Accuracy | .974 | .729 | .828 | .662 | |

| Sensitivity | .333 | .879 | .333 | .121 | Sensitivity | .942 | .841 | .942 | .478 | |

| Specificity | .805 | .059 | .703 | .831 | Specificity | 1.00 | .634 | .732 | .817 | |

| Components of test | Eigenvalue | % Variance | Cumulative % variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| comp 1 ACE R | 1.61 | 32.21 | 32.21 |

| comp 2 ACE R | 1.14 | 22.74 | 54.95 |

| comp 3 ACE R | 1.06 | 21.23 | 76.18 |

| comp 4 ACE R | .674 | 13.49 | 89.66 |

| comp 5 ACE R | .512 | 10.34 | 100.00 |

| comp 1 MMSE | 2.21 | 44.12 | 44.12 |

| comp 2 MMSE | 1.18 | 23.63 | 67.76 |

| comp 3 MMSE | 0.80 | 15.93 | 83.69 |

| comp 4 MMSE | 0.47 | 9.41 | 93.09 |

| comp 5 MMSE | 0.35 | 6.91 | 100.00 |

| comp 1 TYM | 1.95 | 17.71 | 17.71 |

| comp 2 TYM | 1.88 | 17.09 | 34.80 |

| comp 3 TYM | 1.46 | 13.22 | 48.02 |

| comp 4 TYM | 1.12 | 10.18 | 58.21 |

| comp 5 TYM | 1.04 | 9.44 | 67.65 |

| comp 6 TYM | 0.76 | 6.89 | 74.54 |

| comp 7 TYM | 0.68 | 6.15 | 80.69 |

| comp 8 TYM | 0.65 | 5.90 | 86.58 |

| comp 9 TYM | 0.61 | 5.48 | 92.07 |

| comp 10 TYM | 0.56 | 5.09 | 97.16 |

| comp 11 TYM | 0.31 | 2.84 | 100.00 |

| comp 1 TYM-MCI | 1.295 | 32.384 | 32.384 |

| comp 2 TYM-MCI | 1.061 | 26.517 | 58.901 |

| comp 3 TYM-MCI | 0.860 | 21.499 | 80.401 |

| comp 4 TYM-MCI | 0.784 | 19.599 | 100.000 |

| Sub ítem | Dim.1 | Dim.2 | Dim.3 | Dim.4 | Dim.5 | Dim.6 | Dim.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation ACE-R | 0.80 | -0.13 | -0.26 | 0.16 | -0.50 | X | X |

| Memory ACE-R | 0.72 | -0.30 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.40 | X | X |

| Verbal fluency ACE-R | -0.007 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 0.45 | -0.01 | X | X |

| Language ACE-R | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.72 | -0.44 | -0.11 | X | X |

| Visuospatial skills ACE-R | 0.53 | 0.36 | -0.60 | -0.36 | 0.30 | X | X |

| Total ACE-R | 0.85 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.09 | X | X |

| Orientation MMSE | 0.65 | 0.36 | -0.53 | -0.38 | 0.09 | X | X |

| Attention and concentration MMSE | 0.78 | -0.39 | -0.22 | 0.18 | -0.40 | X | X |

| Memory MMSE | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.67 | -0.30 | -0.10 | X | X |

| Language MMSE | 0.68 | -0.60 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.40 | X | X |

| Visuospatial construction MMSE | 0.53 | 0.71 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.08 | X | X |

| Total MMSE | 0.97 | 0.19 | 0.054 | -0.15 | 0.002 | X | X |

| Time-space orientation TYM | 0.42 | 0.64 | -0.31 | 0.15 | 0.21 | -0.16 | -0.12 |

| Direct copy to writing TYM | 0.37 | 0.64 | -0.24 | 0.18 | -0.27 | 0.11 | 0.40 |

| Episodic memory TYM | 0.54 | -0.07 | 0.15 | 0.49 | -0.17 | 0.42 | -0.48 |

| Functional calculation TYM | 0.53 | 0.14 | -0.08 | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Semantic memory TYM | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.68 | -0.27 | 0.46 | 0.17 | -0.06 |

| Similarities TYM | 0.62 | -0.32 | 0.04 | -0.28 | -0.07 | -0.41 | -0.12 |

| Delayed recall and semantic memory TYM | 0.58 | -0.24 | 0.39 | -0.29 | -0.29 | 0.30 | 0.36 |

| Visual agnosia and tracking TYM | -0.18 | -0.35 | -0.60 | -0.20 | 0.30 | 0.44 | 0.03 |

| Visuoconstruction and visuospatial skills TYM | -0.23 | -0.17 | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.20 | -0.13 | 0.25 |

| Deferred recall TYM | -0.50 | 0.54 | 0.14 | -0.07 | -0.08 | 0.19 | 0.005 |

| Evaluator TYM | -0.07 | 0.64 | 0.26 | -0.33 | -0.08 | -0.01 | -0.20 |

| Total TYM | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.21 | -0.004 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.06 |

| Visual episodic memory + visoconstruction + delayed recall |

-0.48 |

-0.57 |

0.65 |

0.10 |

X |

X |

X |

| Episodic verbal memory + delayed recall |

-0.15 |

0.84 |

0.53 |

0.001 |

X |

X |

X |

| Verbal episodic memory + semantic + delayed recall |

0.73 |

-0.06 |

0.21 |

0.65 |

X |

X |

X |

| Episodic visual + semantic + deferred recall |

0.71 |

-0.16 |

0.34 |

-0.60 |

X |

X |

X |

| Total TYM-MCI | 0.12 | -0.30 | 0.93 | 0.16 | X | X | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).