Background

Autism spectrum disorder is now viewed as a moving target rather than a fixed anomaly, with children first showing an overabundance of synapses and hyper-connectivity that later gives way to sparse, under-connected circuits in adolescence and adulthood. Mounting evidence points to overactive mTOR signaling and the downstream glutamatergic cascade as key forces behind this shift, upsetting the delicate balance between building new synapses and pruning excess ones. In this landscape, clinicians and researchers have begun to explore the so-called Cheung glutamatergic regimen—a readily available combination of dextromethorphan, a CYP2D6-blocking antidepressant, piracetam, and l-glutamine—as a low-cost, oral alternative to ketamine for inducing neuroplastic change. Yet the same pharmacology that could reignite plasticity in a pruned adolescent or adult brain could drive excitotoxic damage in a young child whose cortex is already overcrowded with synapses. The present review therefore asks whether, and at what developmental stage, this regimen can be deployed safely to tip neural circuits from dysfunction toward balance.

From Overgrowth to Attrition: How Faulty Synapse Editing Drives the Autism Trajectory

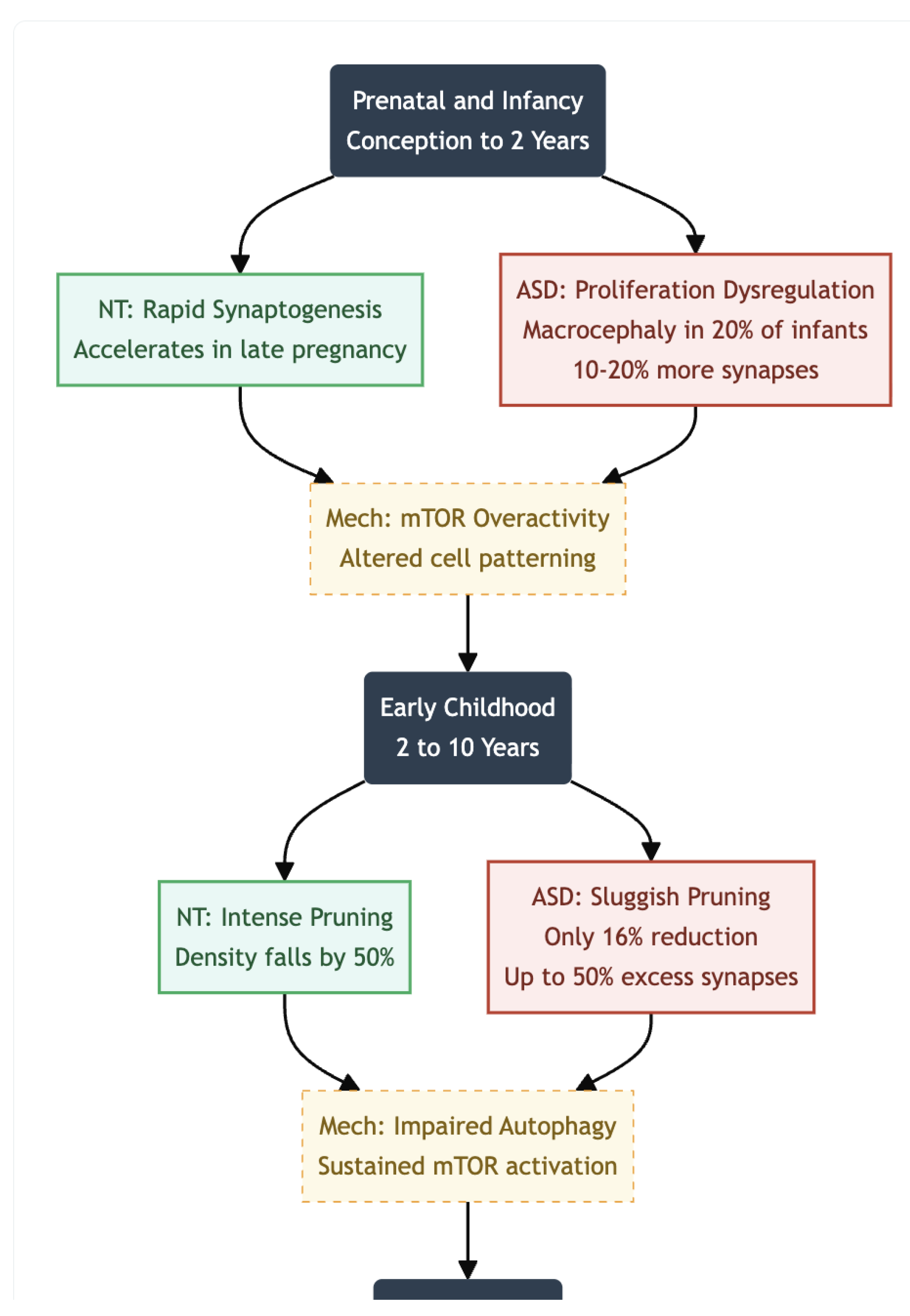

During typical brain development, a surge of synapse formation is followed by large-scale pruning that refines neural circuits and increases their efficiency. In autism spectrum disorder (ASD), however, both phases unfold along markedly different pathways. Post-mortem work has documented a persistent excess of dendritic spines in layer V pyramidal neurons of the temporal cortex, together with evidence that the normal wave of pruning is sharply attenuated (1). Such findings support a view of ASD as a multistage, progressive disorder in which early overproduction of synapses is not matched by adequate later elimination. The resulting surplus may help explain core autistic features—sensory hypersensitivity, social-communication challenges, and repetitive behaviours—because densely connected local circuits can diminish the signal-to-noise ratio that underlies efficient information processing.

Prenatal and Infancy (Conception to ~2 Years)

The first hints of divergence appear well before birth. Synaptogenesis begins at roughly the fifth gestational week (2) and accelerates rapidly in late pregnancy and the first postnatal year (3). Genetic studies point to dysregulation of molecular programs that control cell proliferation and patterning, including overactivity of the mTOR pathway; these alterations are thought to drive both neuronal overproduction and early synaptic abundance. Clinically, the process is mirrored in head-circumference data: approximately one-fifth of infants later diagnosed with ASD show macrocephaly as early as the first six months of life (4,5,6,7,8). Imaging and post-mortem estimates suggest that cortical regions at this stage may contain 10–20% more synapses than those of neurotypical peers (9,10).

Early Childhood ( ~2-10 Years)

From roughly two to ten years of age, synaptic density normally falls by almost half as pruning intensifies. In ASD, by contrast, pruning proceeds sluggishly: one study reported only a 16% reduction in synapse number between childhood and adolescence, compared with about 50% in controls (1). Frontal and temporal cortices can therefore contain up to 50% more synapses than age-matched neurotypical brains, a surplus linked experimentally to sustained mTOR activation and impaired autophagy. Behavioural work shows that children who carry this synaptic excess often display greater symptom severity, lending weight to the hypothesis that pruning deficits translate directly into clinical difficulty.

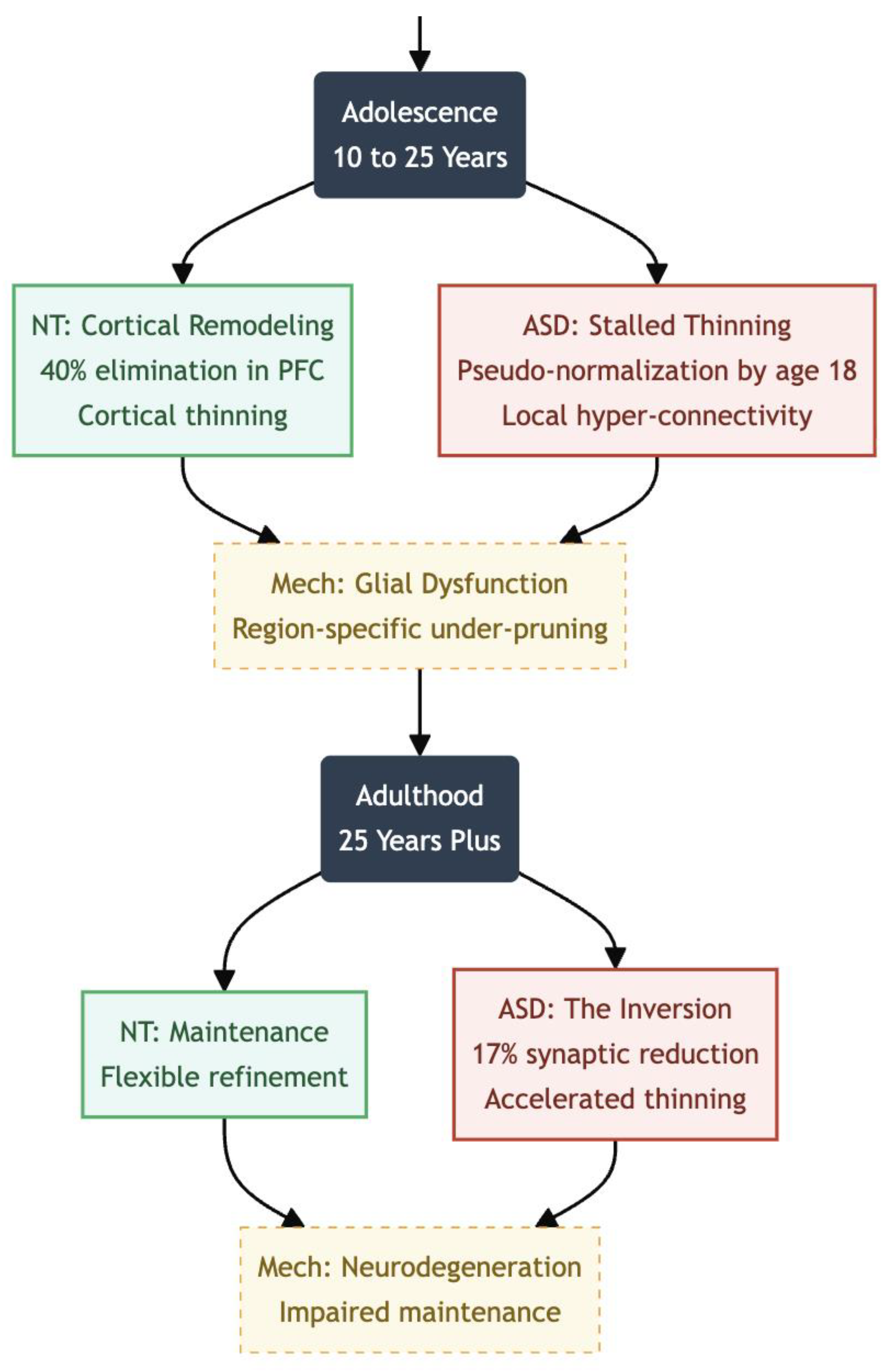

Adolescence (~10–25 Years)

During typical maturation, adolescence is dominated by an intense wave of synaptic pruning that remodels cortico-cortical circuitry, especially within prefrontal and association cortices. Longitudinal imaging and post-mortem work indicate that up to 40 percent of excitatory synapses are eliminated in human prefrontal cortex between roughly ages 10 and 30, cutting total spine density by about one-half and coinciding with marked cortical thinning and continued myelination (11,12). Although synaptogenesis never stops, the new contacts that do form are largely experience-dependent, permitting flexible refinement of executive networks and reward pathways (11).

In autism spectrum disorder the adolescent trajectory is far less uniform. Quantitative spine counts reveal that pruning proceeds, but at a fraction of the neurotypical rate: post-mortem tissue from individuals aged 13–20 shows only a 16 percent reduction in dendritic spines from childhood to adolescence, versus 45 percent in controls (1,13). Excess synapses remain in the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, indicating region-specific under-pruning (14). MRI shows that cortical thinning, which is the macroscopic sign of pruning, happens more slowly in autistic children and then speeds up during mid-adolescence. This creates a “catch-up” or pseudo-normalization by the time the child is about 18 years old, but it still hides unusual micro-architecture (15,16).

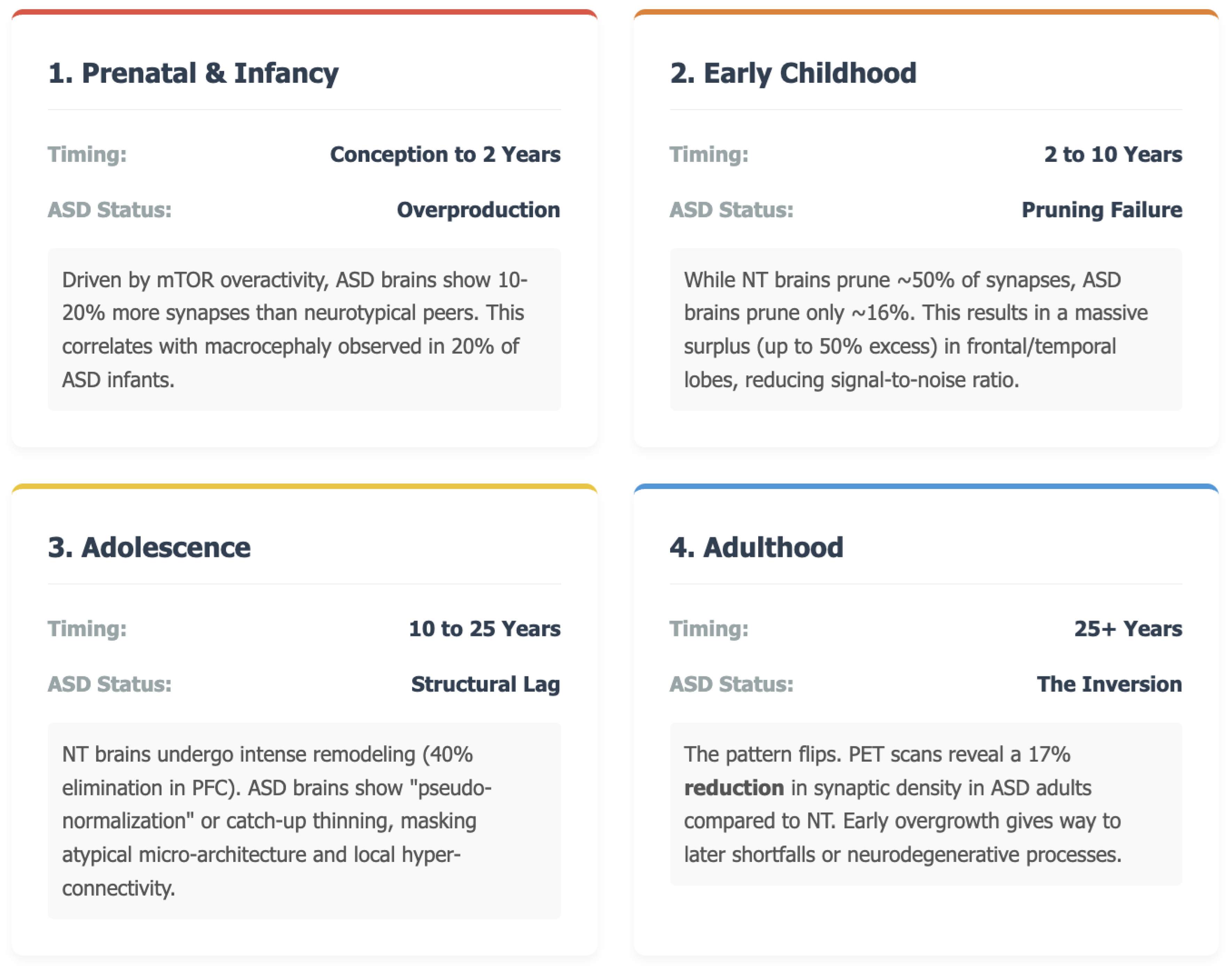

Figure 1.

Prenatal & Infancy (Conception to 2 Years); ASD Status: Overproduction; Driven by mTOR overactivity, ASD brains show 10-20% more synapses than neurotypical peers. This correlates with macrocephaly observed in 20% of ASD infants. Early Childhood (2 to 10 Years); ASD Status: Pruning Failure; While NT brains prune ~50% of synapses, ASD brains prune only ~16%. This results in a massive surplus (up to 50% excess) in frontal/temporal lobes, reducing signal-to-noise ratio.

Figure 1.

Prenatal & Infancy (Conception to 2 Years); ASD Status: Overproduction; Driven by mTOR overactivity, ASD brains show 10-20% more synapses than neurotypical peers. This correlates with macrocephaly observed in 20% of ASD infants. Early Childhood (2 to 10 Years); ASD Status: Pruning Failure; While NT brains prune ~50% of synapses, ASD brains prune only ~16%. This results in a massive surplus (up to 50% excess) in frontal/temporal lobes, reducing signal-to-noise ratio.

Adulthood and Later Life (25+ Years)

By adulthood the picture appears to invert. The first in-vivo positron emission tomography study using the synaptic marker ^11C-UCB-J found an average 17% reduction in synaptic density across multiple brain regions in autistic adults, and lower binding correlated with greater social-communication difficulty (17). These data suggest that early overgrowth can give way to later shortfalls—perhaps through delayed but ultimately excessive pruning, impaired maintenance, or neurodegenerative processes. Longitudinal MRI confirms atypical ageing patterns as well, with some cortical areas showing accelerated thinning while others remain abnormally thick.

Taken together, the literature portrays ASD as a condition in which synaptogenesis is heightened early, pruning is chronically dysregulated, and life-span trajectories diverge from birth onward. Therapeutic strategies that target upstream regulators—mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin, for example—have normalised pruning and improved behaviour in animal models, but translating such approaches to humans will require careful study (1). Continued work that integrates genetics, imaging, and longitudinal clinical follow-up is essential for clarifying how these synaptic alterations map onto the striking heterogeneity of autistic phenotypes.

Figure 2.

Adolescence (10 to 25 Years); ASD Status: Structural Lag; NT brains undergo intense remodeling (40% elimination in PFC). ASD brains show “pseudo-normalization” or catch-up thinning, masking atypical micro-architecture and local hyper-connectivity. Adulthood (25+ Years); ASD Status: The Inversion; The pattern flips. PET scans reveal a 17% reduction in synaptic density in ASD adults compared to NT. Early overgrowth gives way to later shortfalls or neurodegenerative processes.

Figure 2.

Adolescence (10 to 25 Years); ASD Status: Structural Lag; NT brains undergo intense remodeling (40% elimination in PFC). ASD brains show “pseudo-normalization” or catch-up thinning, masking atypical micro-architecture and local hyper-connectivity. Adulthood (25+ Years); ASD Status: The Inversion; The pattern flips. PET scans reveal a 17% reduction in synaptic density in ASD adults compared to NT. Early overgrowth gives way to later shortfalls or neurodegenerative processes.

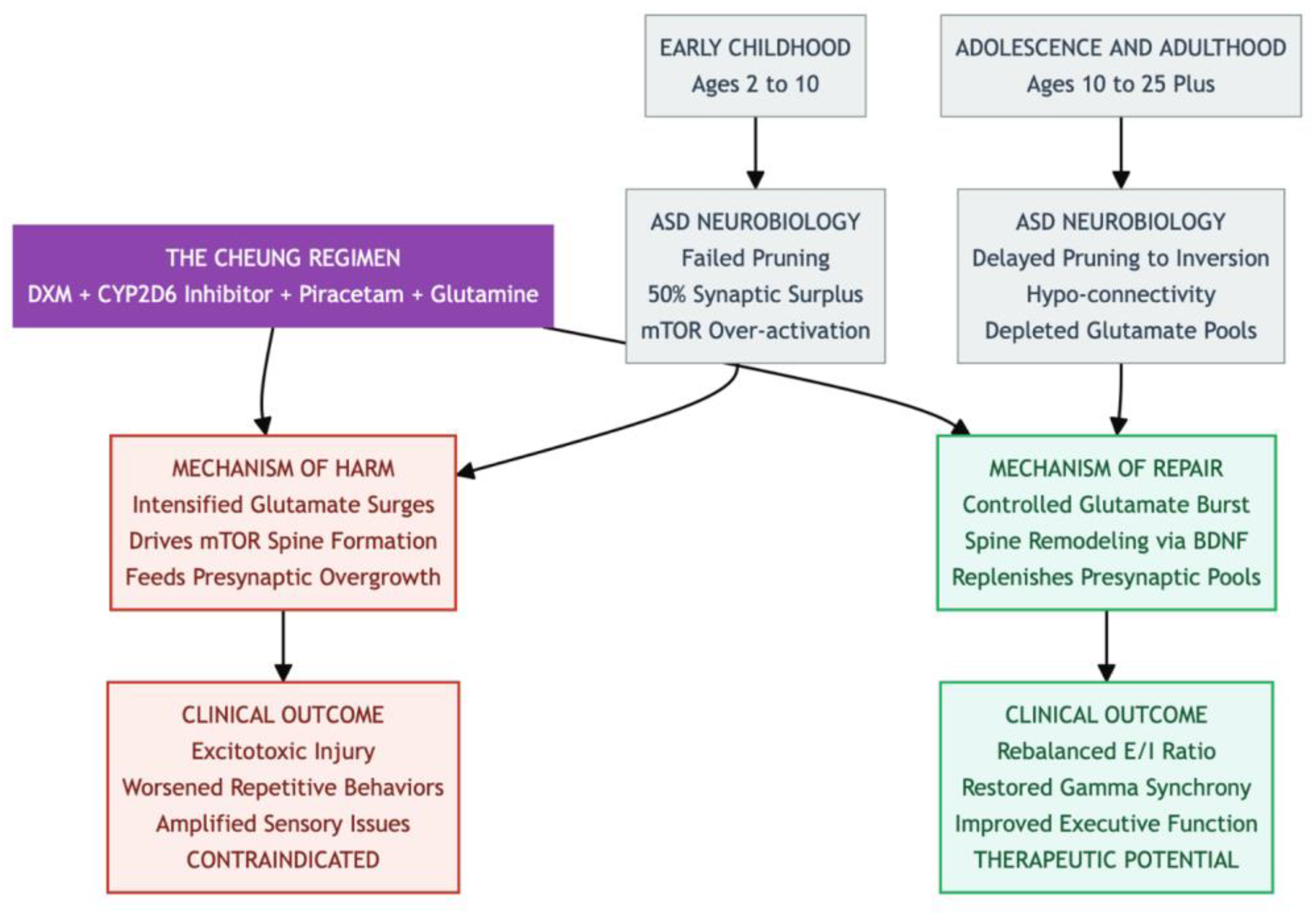

Contraindication in Early Childhood: The Perils of Synaptic Overload in ASD

During early childhood (roughly ages two to ten), a child’s brain normally goes through a sweeping clean-up process in which nearly half of all excitatory synapses are trimmed away. This “pruning” helps streamline communication among distant brain regions and sets the stage for efficient sensory processing and social learning. In autism spectrum disorder (ASD), however, post-mortem tissue studies and longitudinal scans show that barely one-sixth of those connections disappear: the frontal and temporal cortices retain as much as a 50 percent surplus of dendritic spines (1,9). Because microglia struggle to eliminate synapses when the mTOR pathway is chronically over-activated, local networks become hyperconnected, the signal-to-noise ratio plummets, and core features such as sensory hypersensitivity and repetitive behavior are amplified (14,10).

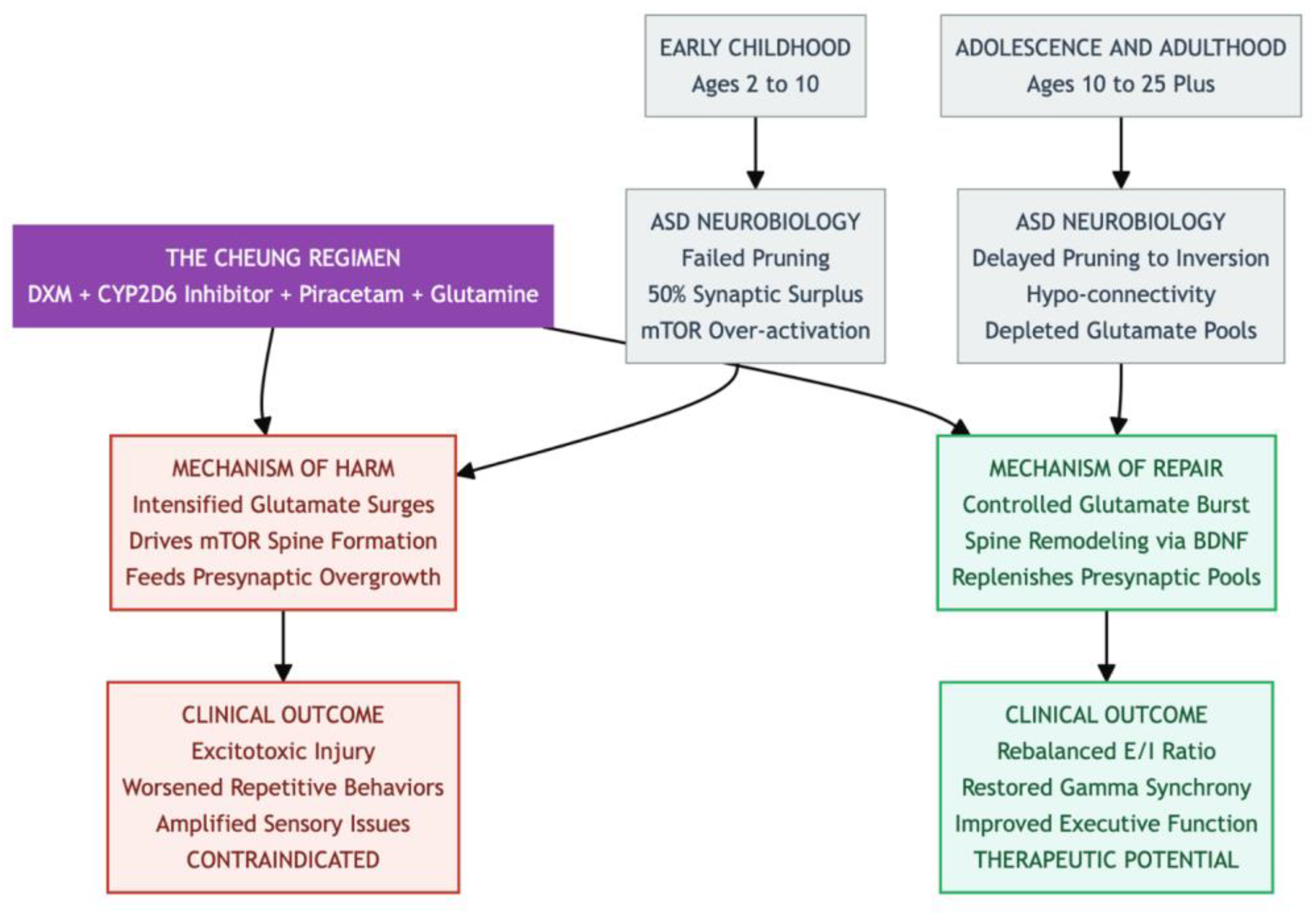

Figure 3.

A Brief Summary On How Faulty Synapse Editing Drives the Autism Trajectory.

Figure 3.

A Brief Summary On How Faulty Synapse Editing Drives the Autism Trajectory.

Against that backdrop, the orally administered Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen—dextromethorphan (DXM) plus a CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressant, piracetam, and L-glutamine—was designed to reproduce ketamine’s rapid neuroplasticity cascade (18,19). Yet the same mechanism that makes the stack attractive for adults could be disastrous for children under ten. DXM blocks NMDA receptors and lifts the brake on pyramidal neurons; piracetam further amplifies AMPA currents; glutamine tops up presynaptic stores. Together, these actions would intensify glutamate surges, drive mTOR-dependent spine formation, and worsen the already unbalanced overgrowth in young ASD brains (20,15,18). The risk is not theoretical: macrocephaly affects up to one-fifth of toddlers with ASD, and excess excitation can push vulnerable circuits toward excitotoxic injury (8,3). Even glutamine—so helpful in mature brains for buffering inflammatory spikes—could, during this high-growth window, feed the presynaptic glutamate pool and entrench behavioral rigidity (21,22). We therefore impose a strict lower age limit, deferring use until after puberty.

Therapeutic Potential in Adolescence and Beyond: Harnessing Plasticity to Remediate ASD Trajectories

The developmental picture changes in adolescence and early adulthood (about ten to twenty-five years). Although pruning in ASD is delayed, it eventually accelerates, sometimes overshooting so that by adulthood synaptic density averages 17 percent below neurotypical norms (1,17). Macroscopic cortical thinning looks “normal,” yet micro-architecture remains skewed: long-range prefrontal–limbic circuits are under-connected, while short-range links are still cluttered (15,12,16). At this stage the Cheung stack may offer a therapeutic opportunity. A brief NMDA blockade from DXM, extended by fluoxetine or another CYP2D6 inhibitor, provokes a controlled glutamate burst; piracetam channels that burst through AMPA receptors, while transient mTOR engagement and BDNF release promote spine remodeling rather than runaway growth (23,24). Such an AMPA-dominant reset could rebalance excitation and inhibition, restore γ-band synchrony, and improve executive function and social reciprocity, effects already hinted at in mTOR-modulation studies (14).

Figure 4.

The Danger Zone: Early Childhood — From approximately ages 2 to 10, the ASD brain enters a critical phase marked by synaptic overload. During this time, the brain already suffers from a 50% surplus of dendritic spines due to failed pruning and mTOR overactivity. Introducing a regimen that boosts glutamate signaling is contraindicated, as it risks excitotoxicity and may exacerbate core symptoms such as sensory hypersensitivity—essentially acting as “fuel to the fire.” The Regimen in question involves a core agent of DXM combined with a CYP2D6 inhibitor, while amplifiers like Piracetam and Glutamine enhance its effects. This stack mimics ketamine by blocking NMDA receptors (via DXM) to induce a glutamate surge; Piracetam channels this surge through AMPA receptors, and Glutamine fuels the presynaptic glutamate pool. While the resulting neuroplasticity cascade is potent, its effect is entirely dependent on the brain’s developmental state. The Therapeutic Window opens post age 10, when ASD brain development shifts toward hypo-connectivity and synaptic depletion. In adolescence and adulthood, this same regimen—now acting on a substrate of under-connectivity—can be beneficial. The controlled glutamate burst and associated BDNF release may help remodel neural circuits, rebalance the excitation/inhibition ratio, and repair long-range connectivity deficits.

Figure 4.

The Danger Zone: Early Childhood — From approximately ages 2 to 10, the ASD brain enters a critical phase marked by synaptic overload. During this time, the brain already suffers from a 50% surplus of dendritic spines due to failed pruning and mTOR overactivity. Introducing a regimen that boosts glutamate signaling is contraindicated, as it risks excitotoxicity and may exacerbate core symptoms such as sensory hypersensitivity—essentially acting as “fuel to the fire.” The Regimen in question involves a core agent of DXM combined with a CYP2D6 inhibitor, while amplifiers like Piracetam and Glutamine enhance its effects. This stack mimics ketamine by blocking NMDA receptors (via DXM) to induce a glutamate surge; Piracetam channels this surge through AMPA receptors, and Glutamine fuels the presynaptic glutamate pool. While the resulting neuroplasticity cascade is potent, its effect is entirely dependent on the brain’s developmental state. The Therapeutic Window opens post age 10, when ASD brain development shifts toward hypo-connectivity and synaptic depletion. In adolescence and adulthood, this same regimen—now acting on a substrate of under-connectivity—can be beneficial. The controlled glutamate burst and associated BDNF release may help remodel neural circuits, rebalance the excitation/inhibition ratio, and repair long-range connectivity deficits.

Glutamine adds a complementary benefit during adolescence. Chronic stress and low-grade inflammation can deplete presynaptic glutamate stores and accelerate synaptic loss; supplementing glutamine replenishes that pool and dampens cytokine-driven toxicity (25,26). Early case series—ranging from trauma-linked somatic complaints to treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive symptoms—report rapid, durable gains when DXM, piracetam, and glutamine are layered onto a CYP2D6-blocking SSRI (27,28,29). Because all components are inexpensive and orally available, the regimen could democratize ketamine-like circuit repair for adolescents and adults with ASD who exhibit mTOR-related dysregulation. Still, systematic trials are essential to fine-tune dosing, confirm durability, and ensure that late-stage pruning is enhanced—rather than reversed—by the intervention (18,19).

Summary

This review underscores that timing is everything when considering the Cheung glutamatergic protocol for autism. In children younger than about ten, autistic brains already carry an excess of poorly pruned excitatory synapses—often reflected in larger head size and heightened sensory reactivity—so further boosting glutamate transmission or mTOR activity could harden behavioral rigidity and even trigger excitotoxic damage. By contrast, once individuals reach adolescence and synaptic density begins to fall, the same drug combination may prove beneficial: transient NMDA blockade paired with AMPA facilitation and glutamine support can help rebalance excitation and inhibition, replenish depleted neurotransmitter stores, and translate into sharper executive skills and improved social engagement, all without the developmental hazards seen in younger brains.

References

- Tang, G.; Gudsnuk, K.; Kuo, S.-H.; Cotrina, M.L.; Rosoklija, G.; Sosunov, A.; Sonders, M.S.; Kanter, E.; Castagna, C.; Yamamoto, A.; et al. Loss of mTOR-Dependent Macroautophagy Causes Autistic-like Synaptic Pruning Deficits. Neuron 2014, 83, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, JJ. Neurology of the newborn E-book. 2008.

- Elsayed, N.A.; Boyer, T.M.; Burd, I. Fetal Neuroprotective Strategies: Therapeutic Agents and Their Underlying Synaptic Pathways. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2021, 13, 680899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.H.; Hadden, L.L.; Takahashi, T.N.; et al. Head circumference is an independent clinical finding associated with autism. Am J Med Genet. 2000, 95, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainhart, J.E.; Bigler, E.D.; Bocian, M.; Coon, H.; Dinh, E.; Dawson, G.; Deutsch, C.K.; Dunn, M.; Estes, A.; Tager-Flusberg, H.; et al. Head circumference and height in autism: A study by the collaborative program of excellence in autism. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2006, 140A, 2257–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fombonne, E.; Rogé, B.; Claverie, J.; Courty, S.; Frémolle, J. Microcephaly and Macrocephaly in Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1999, 29, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, R.; Militerni, R.; Frolli, A.; Bravaccio, C.; Gritti, A.; Elia, M.; Curatolo, P.; Manzi, B.; Trillo, S.; Lenti, C.; et al. Clinical, Morphological, and Biochemical Correlates of Head Circumference in Autism. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 62, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, C.K.; Joseph, R.M. Brief Report: Cognitive Correlates of Enlarged Head Circumference in Children with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2003, 33, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, C.A.; Eberhart, C.G. The neurobiology of autism. Brain Pathol. 2007, 17, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeron, T. From the genetic architecture to synaptic plasticity in autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, L.P. Adolescent Neurodevelopment. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, S7–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantomio, D.; Chana, G.; Laskaris, L.; Testa, R.; Everall, I.; Pantelis, C.; Skafidas, E. Convergent evidence for mGluR5 in synaptic and neuroinflammatory pathways implicated in ASD. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 52, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthes, E. Brains of children with autism teem with surplus synapses. The Transmitter. September 4, 2014.

- Faust, T.E.; Gunner, G.; Schafer, D.P. Mechanisms governing activity-dependent synaptic pruning in the developing mammalian CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khundrakpam, B.S.; Lewis, J.D.; Kostopoulos, P.; Carbonell, F.; Evans, A.C. Cortical Thickness Abnormalities in Autism Spectrum Disorders Through Late Childhood, Adolescence, and Adulthood: A Large-Scale MRI Study. Cereb. Cortex 2017, 27, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, B.A.; Prigge, M.B.D.; Nielsen, J.A.; Froehlich, A.L.; Abildskov, T.J.; Anderson, J.S.; Fletcher, P.T.; Zygmunt, K.M.; Travers, B.G.; Lange, N.; et al. Longitudinal changes in cortical thickness in autism and typical development. Brain 2014, 13 Pt 6 Pt 6, 1799–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuskey, D.; Yang, Y.; Naganawa, M.; Koohsari, S.; Toyonaga, T.; Gravel, P.; Pittman, B.; Torres, K.; Pisani, L.; Finn, C.; et al. 11C-UCB-J PET imaging is consistent with lower synaptic density in autistic adults. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 1610–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. DXM, CYP2D6-Inhibiting Antidepressants, Piracetam, and Glutamine: Proposing a Ketamine-Class Antidepressant Regimen with Existing Drugs. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Clinical Experience and Optimisation of the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen for Refractory Psychiatric Diseases. Preprints, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Lee, B.; Liu, R.-J.; Banasr, M.; Dwyer, J.M.; Iwata, M.; Li, X.-Y.; Aghajanian, G.; Duman, R.S. mTOR-Dependent Synapse Formation Underlies the Rapid Antidepressant Effects of NMDA Antagonists. Science 2010, 329, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. IL-1β and TNF-α induce neurotoxicity through glutamate production: a potential role for neuronal glutaminase. J Neurochem. 2013, 125, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.H.; Jung, S.; Son, H.; Kang, J.S.; Kim, H.J. Glutamine Supplementation Prevents Chronic Stress-Induced Mild Cognitive Impairment. Nutrients 2020, 12, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, S.; Zarate, C.A.; Du, J.; et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of Ketamine: role of AMPA receptors. Biol Psychiatry 2008, 63, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, H.; Iijima, M.; Chaki, S. Involvement of AMPA receptor in both the rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in animal models of depression. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 224, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, H.; Baek, J.H.; Go, B.S.; Jung, D.-H.; Sontakke, S.B.; Chung, H.J.; Lee, D.H.; Roh, G.S.; Kang, S.S.; Cho, G.J.; et al. Glutamine has antidepressive effects through increments of glutamate and glutamine levels and glutamatergic activity in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology 2018, 143, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Molina, M.P.; Morales-Conejo, M.; Delmiro, A.; Morán, M.; Domínguez-González, C.; Arranz-Canales, E.; Ramos-González, A.; Arenas, J.; Martín, M.A.; de la Aleja, J.G. High-dose oral glutamine supplementation reduces elevated glutamate levels in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes syndrome. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Case Series: Marked Improvement in Treatment-Resistant Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms with Over-the-Counter Glutamatergic Augmentation in Routine Clinical Practice. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. An Oral “Ketamine-Like” NMDA/AMPA Modulation Stack Restores Cognitive Capacity in a Young Man with Schizoaffective Disorder—Case Report. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Oral Glutamatergic Augmentation for Trauma-Related Disorders with Fluoxetine- / Bupropion- Potentiated Dextromethorphan ± Piracetam: A Four-Patient Case Series. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).