Background

Roughly one-third of people living with major depressive disorder never achieve full remission despite multiple trials of conventional antidepressants; they fall into the category now labelled treatment-resistant depression, or TRD [

1]. Among adults with TRD, inattentive-type attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is strikingly common, with prevalence estimates hovering between one quarter and two fifths [

2,

3]. The overlap creates a therapeutic tight-rope. Serotonergic or noradrenergic drugs that form the backbone of standard depression care often underperform in TRD, yet the stimulants that reliably sharpen attention seldom lift mood and can aggravate insomnia or anxiety.

Interest has therefore shifted toward glutamatergic strategies. Intravenous ketamine and intranasal esketamine can reverse depressive symptoms within hours, even in deeply refractory cases [

4,

5]. Their reach, however, is blunted by cost, monitoring requirements, and limited clinic availability. In search of a simpler option, Cheung [

6] proposed an entirely oral protocol that combines low-dose dextromethorphan—kept in circulation by pairing it with a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor—with piracetam to amplify downstream AMPA signalling. Early open-label experience hints at surprisingly fast and robust antidepressant and anti-obsessional effects.

A snag appears when the same patient also relies on a stimulant, particularly lisdexamfetamine. However, standard inhibitory doses of paroxetine, fluoxetine, or bupropion could lengthen stimulant exposure and invite jitteriness, insomnia, or blood-pressure spikes.

The present report describes how an ultra-low, bedtime dose of controlled-release paroxetine (6.25 mg) was used to anchor the Cheung glutamatergic regimen in a 35-year-old woman with long-standing TRD who remained dependent on morning lisdexamfetamine for inattentive ADHD. The strategy provided rapid relief of depressive and anxious symptoms without disrupting stimulant tolerability, and may offer a practical blueprint for managing this increasingly common pharmacologic intersection.

Methods

The patient was assessed and treated by the author in a private outpatient psychiatry clinic in Hong Kong between October and November 2025. Diagnosis was clinical (DSM-5) supported by Continuous Performance Test (Conners CPT-3) and serial Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scores. The Cheung glutamatergic regimen was defined as a CYP2D6 inhibitor + dextromethorphan + piracetam (or another AMPA positive allosteric modulator), all administered at night. Paroxetine CR 12.5 mg tablets were halved to yield 6.25 mg, the lowest commercially available dose. Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) 20 mg was continued each morning. Low-dose risperidone 0.25 mg nightly was retained for ruminative agitation. Follow-up occurred every 2–4 weeks with clinical interview, self-rating scales, and monitoring for stimulant side-effects or pharmacokinetic interaction.

All participants gave written permission for their anonymised clinical information to be reported. For individuals younger than 18 years, parental or guardian consent was obtained in addition to the patient's written assent.

Results

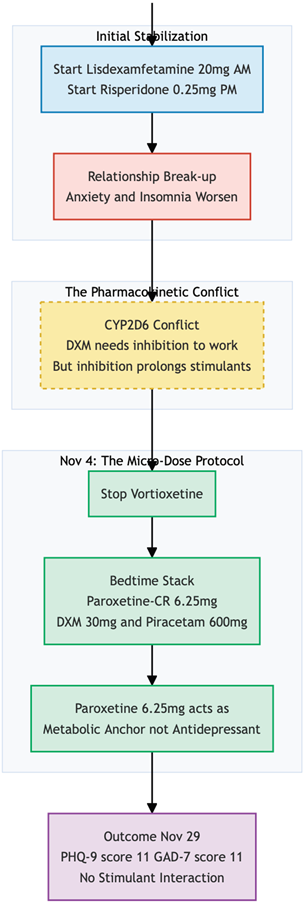

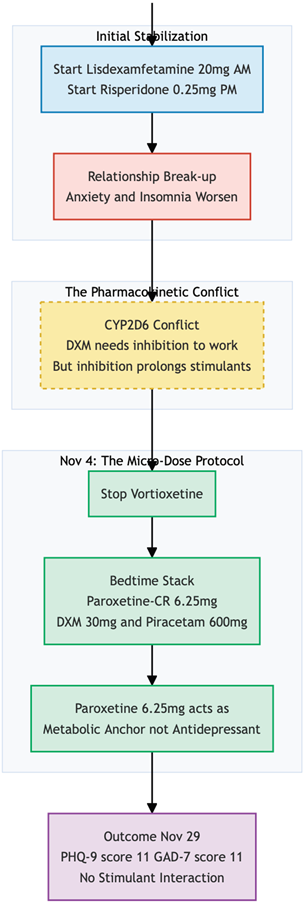

Miss L, a 35-year-old office administrator, was first seen on 21 October 2025 for long-standing mood disturbance, pronounced anxiety, and lifelong problems with concentration. She was seen by other psychiatrists before, described a persistent "grey wallpaper" depression dating back to childhood, punctuated by bouts of irritability and paralysing procrastination that had jeopardised several jobs and relationships. A hospital admission for suicidal ideation the previous year had been followed by trials of vortioxetine, high-dose zopiclone, and two other antidepressants, none of which produced more than fleeting benefit. On intake she reported pervasive hopelessness, fear of losing her new position because of missed deadlines, and increasing tension at home. Continuous-performance testing confirmed marked inattentive ADHD, while self-ratings placed her in the severe range for depression (PHQ-9 = 21) and the upper-moderate range for anxiety (GAD-7 = 14). The working diagnosis was treatment-resistant major depressive disorder with anxious distress, comorbid ADHD—predominantly inattentive type.

She started on lisdexamfetamine 20 mg each morning for attentional deficits, with low-dose risperidone 0.25 mg at night to temper ruminative agitation, on top of her usual regime (Vortioxetine 20mg Daily). Two weeks later, an unexpected relationship break-up triggered a sharp emotional slide; although her PHQ-9 fell to 14, anxiety remained unchanged and insomnia worsened. At this visit, Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen (6), a fully oral glutamatergic protocol was introduced while vortioxetine stopped. Ultra-low-dose paroxetine-CR 6.25 mg was chosen as a potent CYP2D6 inhibitor unlikely to prolong stimulant action, and combined at bedtime with dextromethorphan 30 mg and piracetam 600 mg. The risperidone and morning lisdexamfetamine were left in place.

By 29 November—25 days after the glutamatergic stack was added—Miss L reported that both mood and anxiety were "much better." She had reconciled with her partner, was making plans for a Christmas trip to Germany, and felt able to manage ordinary workplace stress. Objective scores echoed the change (PHQ-9 = 11; GAD-7 = 11). The main residual problems were fragmented sleep and a tendency to take a second, unsanctioned dose of lisdexamfetamine late in the afternoon when the morning effect wore off.

Within four weeks the combination produced a clinically meaningful shift from severe to moderate symptomatology, restored interpersonal stability, and rekindled future planning. Importantly, the glutamatergic agents were well tolerated and showed no adverse interaction with the prescribed stimulant, suggesting that an ultra-low-dose paroxetine anchor can safely support nightly dextromethorphan-piracetam therapy even in patients who rely on daytime lisdexamfetamine for ADHD.

Conclusions

This case illustrates how an oral glutamatergic protocol can be woven into a complex psychopharmacologic tapestry without upsetting the balance already achieved for comorbid ADHD [

7,

8]. The central problem was straightforward: dextromethorphan needs a potent CYP2D6 inhibitor to stay in the therapeutic range [

9,

10], yet lisdexamfetamine, the patient's sole defence against crippling inattention, can be overly prolonged by that very same inhibition [

11,

12].

Although lisdexamfetamine is largely converted to d-amphetamine by enzymatic hydrolysis rather than the cytochrome system [

13,

11], a small oxidative pathway does run through CYP2D6 [

14,

15]. Full-strength paroxetine, fluoxetine, or bupropion would almost certainly slow this secondary route and risk a longer or more intense stimulant tail [

16,

17], with insomnia, jitteriness, or blood-pressure spikes to follow. To sidestep that hazard we settled on a deliberately tiny dose of paroxetine-CR—just 6.25 mg at night. At such a level the drug contributes little, if anything, to mood but still shifts dextromethorphan from rapid to intermediate metabolism, stretching its half-life into a useful therapeutic window [

18,

19].

Timing did the rest of the work. By giving paroxetine, dextromethorphan, and piracetam together at bedtime, we placed the peak of CYP2D6 inhibition squarely in the hours when d-amphetamine levels from the morning Vyvanse have already fallen. The patient reported no change in the onset or offset of stimulant action, no new palpitations, and no extra difficulty sleeping—evidence that the interaction, if present at all, remained clinically silent. Her occasional impulse to take an unscheduled second dose of Vyvanse fit the classic afternoon "fade" seen in many adults and could not be pinned on altered clearance.

With the pharmacokinetic puzzle solved, the clinical gains arrived quickly. Within four weeks depressive symptoms moved from the severe into the moderate band, anxiety eased, and she re-engaged with both work and personal life. Importantly, these benefits came without sacrificing attentional control: the morning lisdexamfetamine continued to tame her distractibility just as before.

The experience suggests a practical rule of thumb. When stimulants and dextromethorphan must live side by side, a micro-dose of a strong CYP2D6 blocker—taken at night and kept well below conventional antidepressant ranges—can provide enough enzyme inhibition for glutamatergic therapy while leaving stimulant kinetics essentially unchanged. For clinicians who treat the frequent pairing of mood disorders and adult ADHD [

7,

8,

20], that strategy opens the door to ketamine-like results with drugs that are inexpensive, oral, and easily adjusted.

Conflict of Interest and Source of Funding Statement

None declared.

References

- Zhdanava, M.; Pilon, D.; Ghelerter, I.; et al. The Prevalence and National Burden of Treatment-Resistant Depression and Major Depressive Disorder in the United States. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 82, 20m13699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.H.; Pan, T.L.; Hsu, J.W.; et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder comorbidity and antidepressant resistance among patients with major depression: A nationwide longitudinal study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternat, T.; Fotinos, K.; Fine, A.; et al. Low hedonic tone and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: risk factors for treatment resistance in depressed adults. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 2379–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, G.C.; Demo, I.; Goes, F.S.; et al. Personalized use of ketamine and esketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystal, J.H.; Kavalali, E.T.; Monteggia, L.M. Ketamine and rapid antidepressant action: new treatments and novel synaptic signaling mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. DXM, CYP2D6-Inhibiting Antidepressants, Piracetam, and Glutamine: Proposing a Ketamine-Class Antidepressant Regimen with Existing Drugs. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Adler, L.; Barkley, R.; et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.; Adamo, N.; Ásgeirsdóttir, B.B.; et al. Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadel, M.; Wu, D.; Otton, S.V.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of dextromethorphan and metabolites in humans: influence of the CYP2D6 phenotype and quinidine inhibition. J. Clin. Psychopharmacology 1995, 15, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.A.; Reviriego, J.; Lou, Y.Q.; et al. Diazepam metabolism in native Chinese poor and extensive hydroxylators of S-mephenytoin: interethnic differences in comparison with white subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1990, 48, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, S.M.; Pennick, M.; Stark, J.G. Metabolism, distribution and elimination of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: open-label, single-centre, phase I study in healthy adult volunteers. Clin. Drug Investig. 2008, 28, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. VYVANSE (lisdexamfetamine dimesylate) capsules, for oral use, CII. 2007. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/021977lbl.

- Pennick, M. Absorption of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate and its enzymatic conversion to d-amphetamine. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2010, 6, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, M.V.; Coutts, R.T.; Baker, G.B. Involvement of CYP2D6 in the in vitro metabolism of amphetamine, two N-alkylamphetamines and their 4-methoxylated derivatives. Xenobiotica 1999, 29, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharman, J.; Pennick, M. Lisdexamfetamine prodrug activation by peptidase-mediated hydrolysis in the cytosol of red blood cells. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 2275–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro, C.L.; Lam, Y.W.; Simpson, J.; et al. CYP2D6 status of extensive metabolizers after multiple-dose fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, or sertraline. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999, 19, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ereshefsky, L.; Riesenman, C.; Lam, Y.W. Antidepressant drug interactions and the cytochrome P450 system. The role of cytochrome P450 2D6. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1995, 29, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessurun, N.T.; Vermeulen Windsant, A.; Mikes, O.; et al. Inhibition of CYP2D6 with low dose (5 mg) paroxetine in patients with high 10-hydroxynortriptyline serum levels-A prospective pharmacokinetic study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 1529–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laine, K.; Tybring, G.; Härtter, S.; et al. Inhibition of cytochrome P4502D6 activity with paroxetine normalizes the ultrarapid metabolizer phenotype as measured by nortriptyline pharmacokinetics and the debrisoquin test. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 70, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, P.S.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Kraemer, H.C.; et al. ADHD comorbidity findings from the MTA study: comparing comorbid subgroups. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).