Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

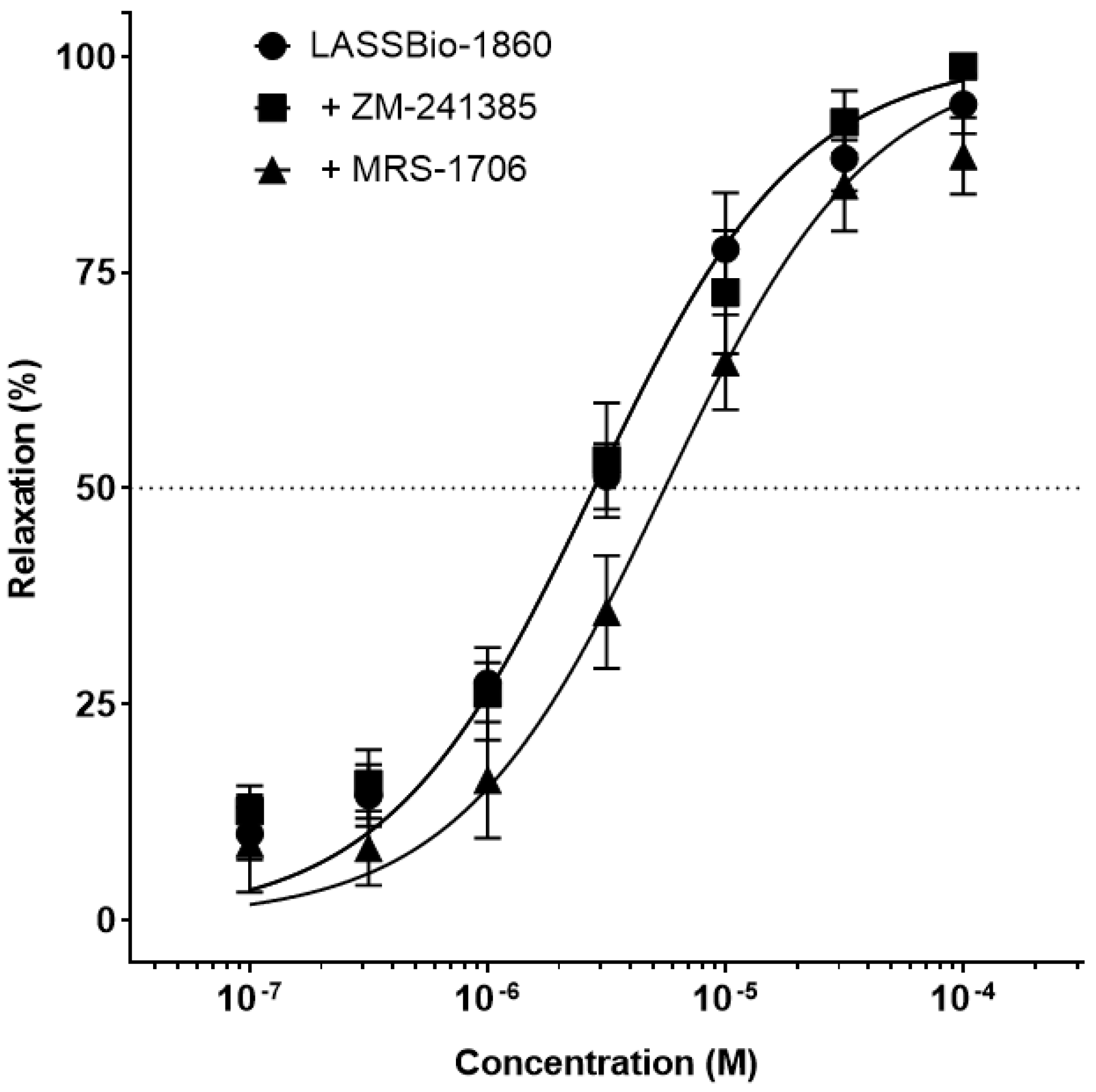

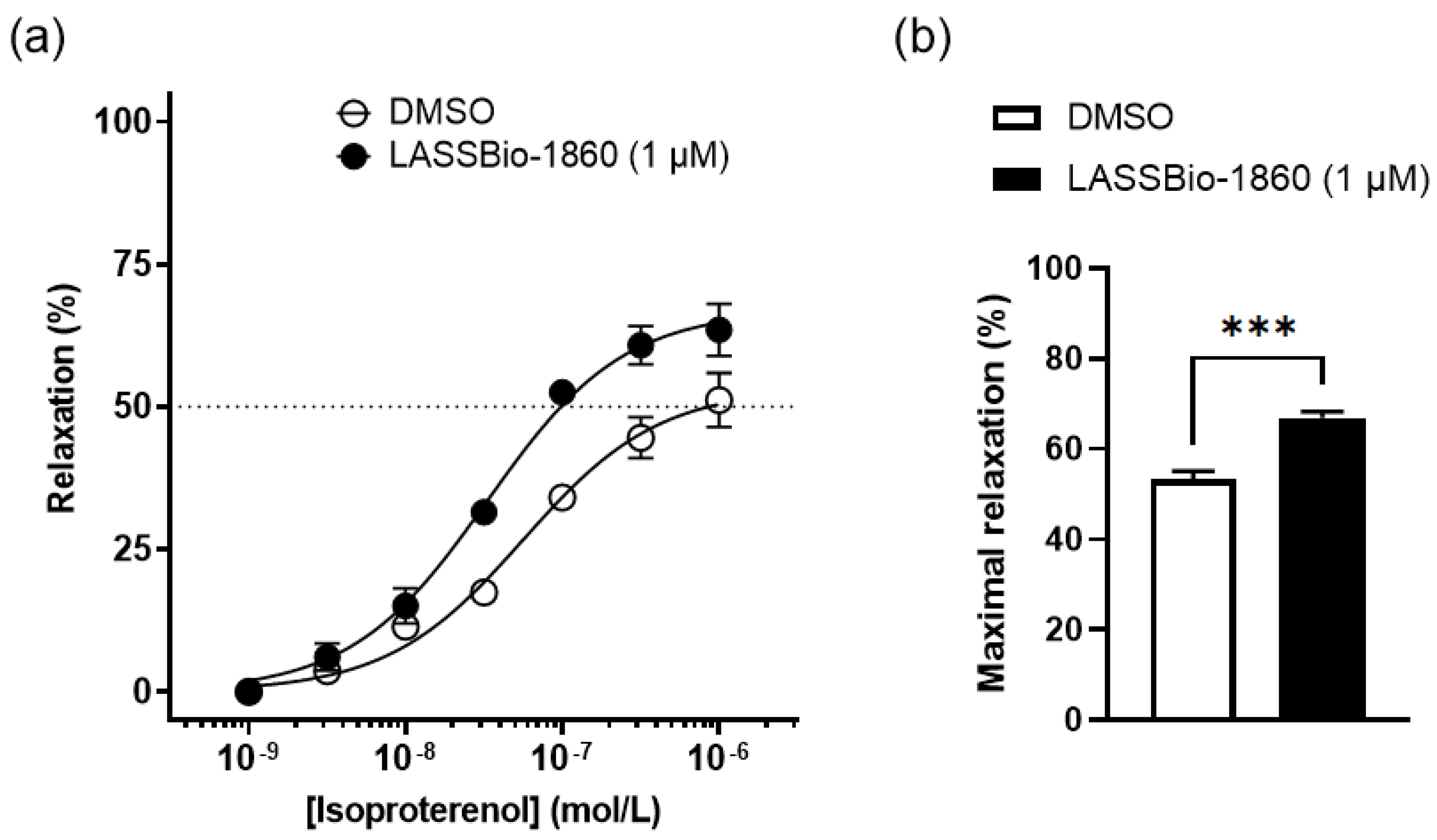

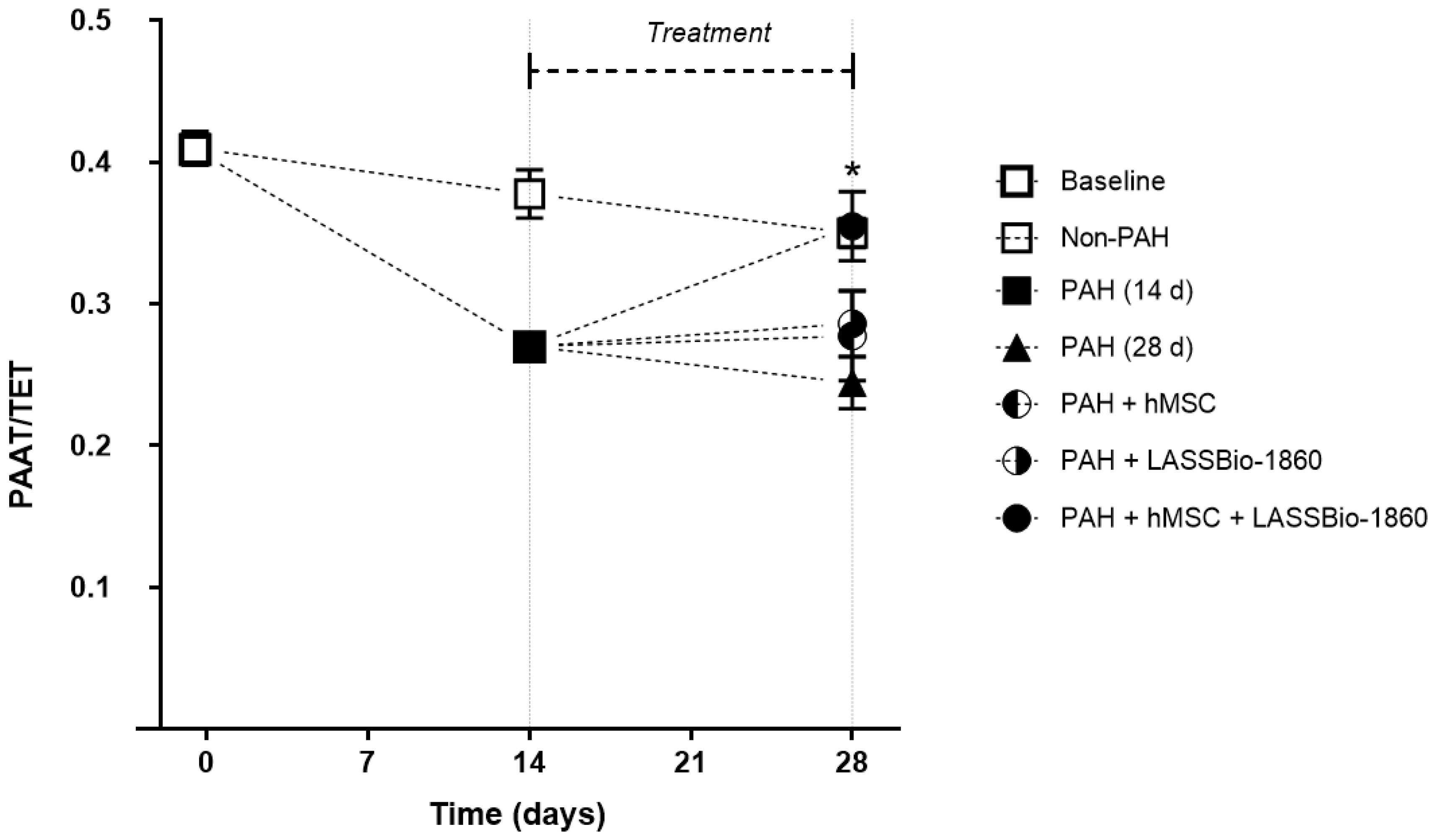

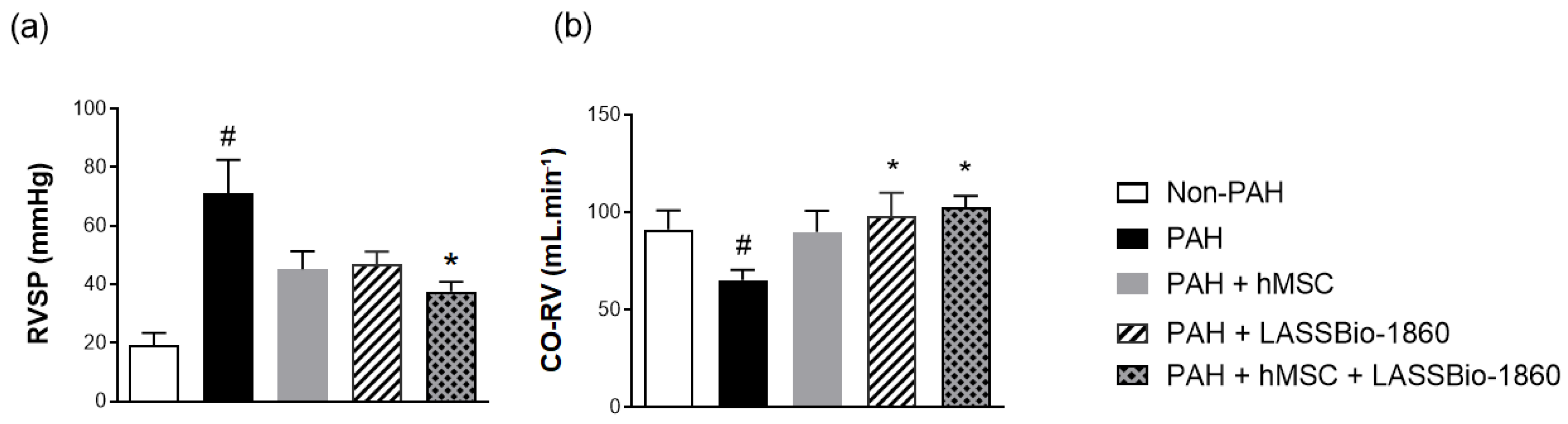

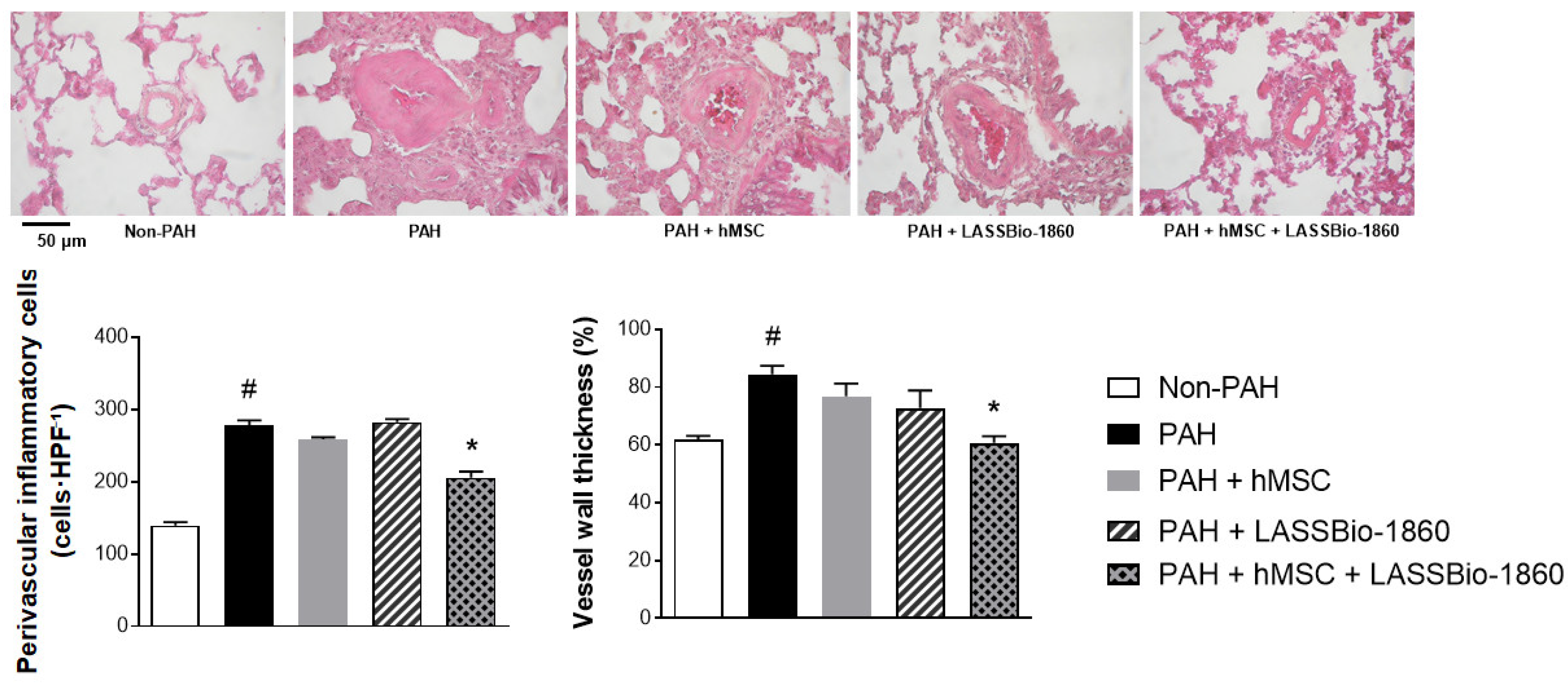

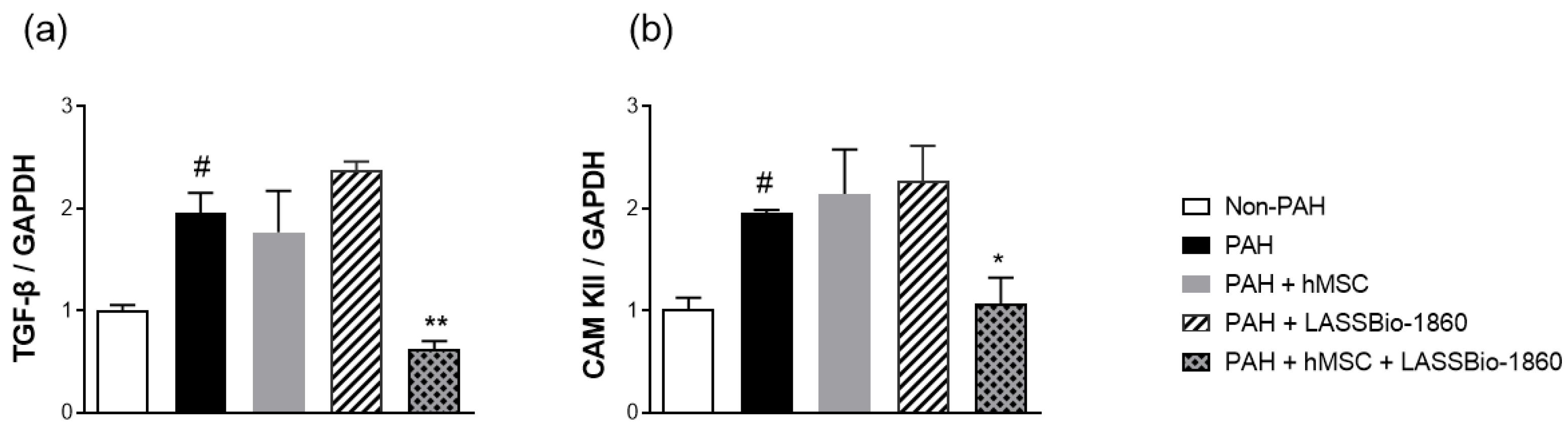

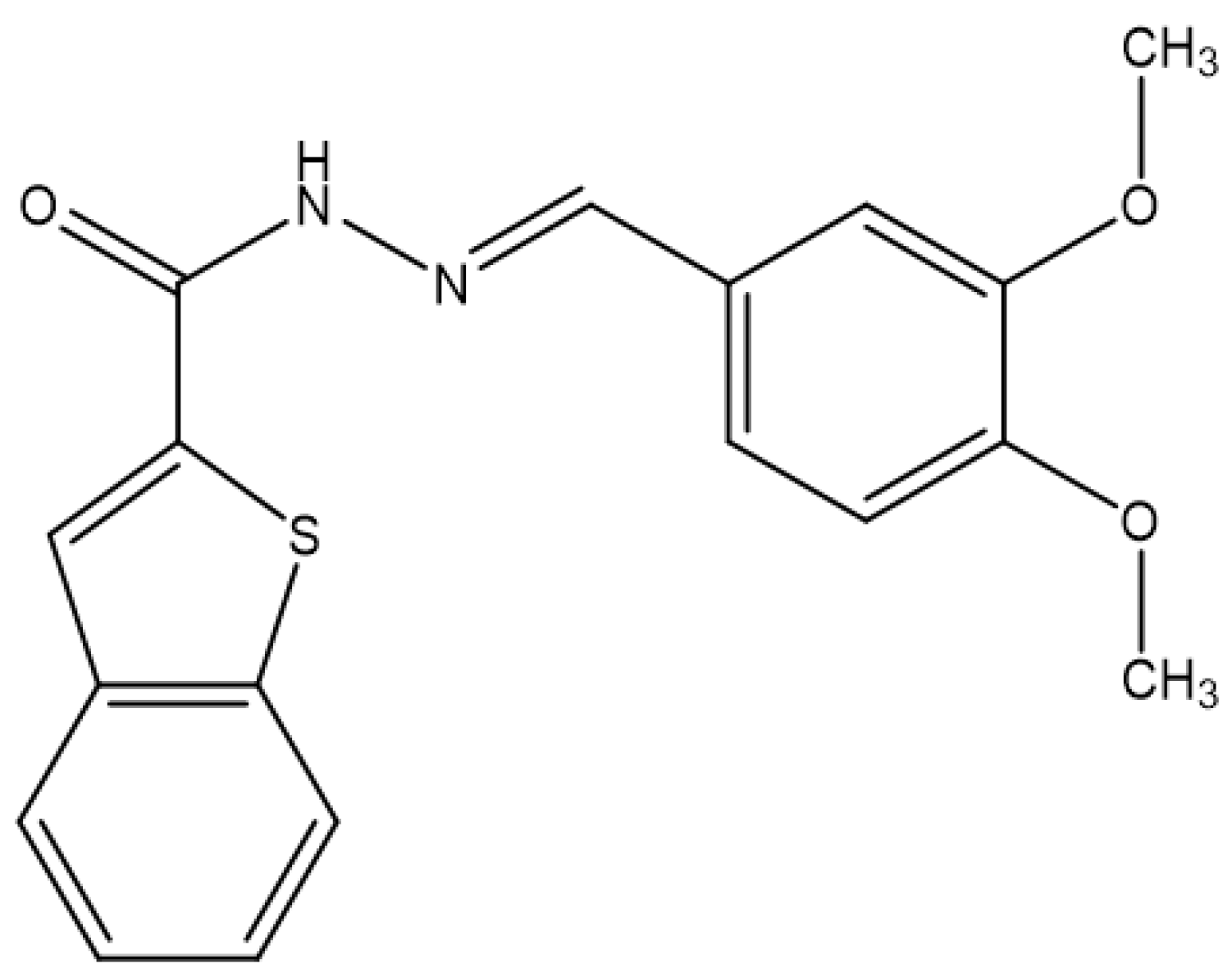

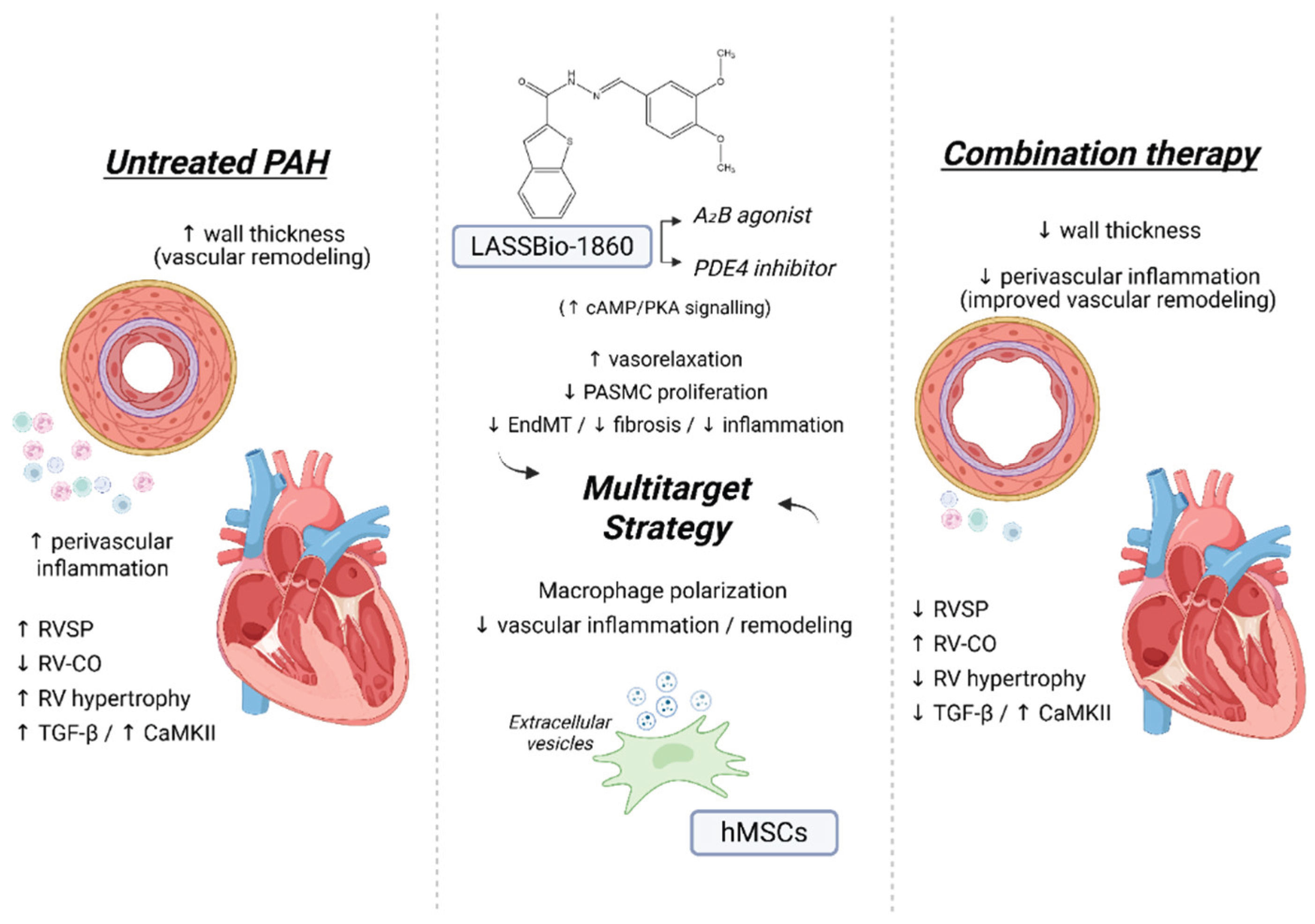

Background/Objectives. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare but severe disease which leads to right ventricular (RV) maladaptation, failure and death. Currently approved drugs have limited impact on disease progression. A multitarget strategy consisted of activation of adenosine A2B receptor and inhibition of phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) in combination with human mesenchymal stromal cells (hMSCs) was tested in PAH animal model. The main objective was to determine whether the combination improves pulmonary hemodynamics, vascular remodeling, and RV function, given the limited disease-modifying effects of approved vasodilators. Methods. Vascular reactivity was assessed in isolated rat pulmonary artery rings exposed to the dual target compound named LASSBio-1860 alone or in the presence of either A2A (ZM-241385) or A2B (MRS-1706) antagonist. PAH was induced in male Wistar rats through the administration of monocrothaline (MCT, 60 mg·kg−1). After confirmation of PAH, by the decrease of the ratio of pulmonary artery acceleration time and ejection time ratio (PAAT/TET), animals were randomized divided to receive vehicle, hMSC (single i.v. dose, 1×105 cells), LASSBio-1860 (62 mg·kg−1·day−1, p.o., 14 days), or the combination. Outcomes included PAAT/TET and RV cardiac output (RV-CO) using echocardiography, RV systolic pressure (RVSP) by direct puncture, Fulton index and RV wall thickness, lung histology (perivascular cell counts and wall thickness), and RV protein expression (TGF-β, CaMKII) by Western blot. Results. LASSBio-1860 produced endothelium-independent vasorelaxation of rat pulmonary arteries, consistent with A2B agonism and PDE4 inhibition responses. In MCT-induced PAH, the combination of LASSBio-1860 with hMSCs promoted: 1. Recovery of PAAT/TET and RV-CO; 2. Decrease of RVSP; 3. Reduction of RV hypertrophy, vascular inflammation and remodeling; 4. Downregulation of ventricular TGF-β and CaMKII. Conclusions. Combination of LASSBio-1860 with hMSC improved RV function, attenuated pulmonary hypertension, RV and vascular remodeling; reduced inflammatory/proliferative signaling in MCT induced-PAH, supporting a promising multitarget therapeutic strategy for PAH.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Dual Target of LASSBio-1860

2.2. Combination of LASSBio-1860 with Mesenchymal Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Drugs and Reagents

4.2. Animals and Experimental Design

4.3. Vascular Reactivity of Pulmonary Artery Rings

4.4. PAH Induction

4.5. Transthoracic Echocardiography

4.6. Cardiac Catheterism

4.7. Morphometric and Histological Analysis

4.8. Membrane Preparation and Western Blot

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bousseau, S.; Sobrano Fais, R.; Gu, S.; Frump, A.; Lahm, T. Pathophysiology and New Advances in Pulmonary Hypertension. BMJ Med. 2023, 2, e000137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonneau, G.; Montani, D.; Celermajer, D.S.; Denton, C.P.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Krowka, M.; Williams, P.G.; Souza, R. Haemodynamic Definitions and Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benza, R.L.; Miller, D.P.; Barst, R.J.; Badesch, D.B.; Frost, A.E.; McGoon, M.D. An Evaluation of Long-Term Survival from Time of Diagnosis in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension from the Reveal Registry. Chest 2012, 142, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiè, N.; Barberà, J.A.; Frost, A.E.; Ghofrani, H.-A.; Hoeper, M.M.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Peacock, A.J.; Simonneau, G.; Vachiery, J.-L.; Grünig, E.; et al. Initial Use of Ambrisentan plus Tadalafil in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, A.J.; Zamboni, W.; Vizza, C.D. Ambrisentan for the Treatment of Adults with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: A Review. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2015, 31, 1793–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowski, C.T.; Rissmiller, R.W.; Bullington, W.M. Riociguat: A Novel New Drug for Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Pharmacotherapy 2015, 35, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausó, E.; Gómez-Vicente, V.; Esquiva, G. Visual Side Effects Linked to Sildenafil Consumption: An Update. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, R.P.; Hill, J.W.; Lickert, C.A.; Wade, R.L.; Cole, M.R.; Tsang, Y.; Drake, W. Medication Adherence, Hospitalization, and Healthcare Resource Utilization and Costs in Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Treated with Endothelin Receptor Antagonists or Phosphodiesterase Type-5 Inhibitors. Pulm. Circ. 2020, 10, 2045894019880086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.E.; Cober, N.D.; Dai, Z.; Stewart, D.J.; Zhao, Y.-Y. Endothelial Cells in the Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2003957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vara, E.; Ntokou, A.; Dave, J.M.; Jovin, D.G.; Saddouk, F.Z.; Greif, D.M. Vascular Pathobiology of Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Heart Lung Transplant. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Heart Transplant. 2023, 42, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacher, E.; Graham, B.B.; Hunt, J.M.; Gandjeva, A.; Groshong, S.D.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Jessup, M.; Grizzle, W.E.; Aldred, M.A.; Cool, C.D.; et al. Modern Age Pathology of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszak, P.; Alphonse, R.; Vadivel, A.; Ionescu, L.; Eaton, F.; Thébaud, B. Preconditioning Enhances the Paracrine Effect of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Preventing Oxygen-Induced Neonatal Lung Injury in Rats. Stem Cells Dev. 2012, 21, 2789–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-H.; Liang, J.-P.; Zhu, C.-J.; Lian, Y.-J. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Therapy for Pulmonary Hypertension: A Comprehensive Review of Preclinical Studies. J. Intervent. Cardiol. 2022, 2022, 5451947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loisel, F.; Provost, B.; Haddad, F.; Guihaire, J.; Amsallem, M.; Vrtovec, B.; Fadel, E.; Uzan, G.; Mercier, O. Stem Cell Therapy Targeting the Right Ventricle in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Is It a Potential Avenue of Therapy? Pulm. Circ. 2018, 8, 2045893218755979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelova, A.; Berman, M.; Al Ghouleh, I. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 891–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.J.; Beckmann, T.; Vorla, M.; Kalra, D.K. New Drugs and Therapies in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucherat, O.; Bonnet, S.; Provencher, S.; Potus, F. Anti-Remodeling Therapies in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2025, 46, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, F.; Nascimento-Carlos, B.; da Silva, J.S.; Maia, R.C.; Montagnoli, T.L.; Barreiro, E.J.; Zapata-Sudo, G. Novel Agonists of Adenosine Receptors in Animal Model of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2024, 18, 5211–5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, M.D.D. Novos protótipos heteroaril-n-acilidrazônicos multialvos planejados para o tratamento da hipertensão arterial pulmonar, UFRJ: Rio de Janeiro, 2017.

- Alencar, A.K.N.; Montes, G.C.; Barreiro, E.J.; Sudo, R.T.; Zapata-Sudo, G. Adenosine Receptors As Drug Targets for Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, R.K.; Baruscotti, I.; Stiller, R.; Fingerle, J.; Gillespie, D.G.; Mi, Z.; Leeners, B.; Imthurn, B.; Rosselli, M.; Jackson, E.K. Adenosine, Via A2B Receptors, Inhibits Human (P-SMC) Progenitor Smooth Muscle Cell Growth. Hypertension 2020, 75, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Cao, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, L.; Huang, X.; Ding, C.; Cai, X.; Yin, F.; Chu, J.; Li, G.; et al. Paeoniflorin Inhibits Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells Proliferation via Upregulating A2B Adenosine Receptor in Rat. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e69141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckly-Michel, A.; Martin, V.; Lugnier, C. Involvement of Cyclic Nucleotide-Dependent Protein Kinases in Cyclic AMP-Mediated Vasorelaxation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 122, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Hou, Y.; Fan, T.; Gao, R.; Feng, X.; Li, B.; Pang, J.; Guo, W.; Shu, T.; Li, J.; et al. Endothelial Phosphodiesterase 4B Inactivation Ameliorates Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Pulmonary Hypertension. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 1726–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.-L.C.; Ding, S.-L.; Lin, S.-C. Phosphodiesterase 4 and Its Inhibitors in Inflammatory Diseases. Chang Gung Med. J. 2012, 35, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yang, L. PDE4 Inhibitors: Potential Protective Effects in Inflammation and Vascular Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1407871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M. de M.C.; de Alencar, A.K.N.; da Silva, J.S.; Montagnoli, T.L.; da Silva, G.F.; Rocha, B. de S.; Montes, G.C.; Mendez-Otero, R.; Pimentel-Coelho, P.M.; Vasques, J.F.; et al. Therapeutic Benefit of the Association of Lodenafil with Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats. Cells 2020, 9, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Qiao, H.; Wang, P.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Yu, H.; Qu, L. alpha1A-Adrenoceptor Is Involved in Norepinephrine-Induced Proliferation of Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells via CaMKII Signaling. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 9345–9355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.E.; Brown, J.H.; Bers, D.M. CaMKII in Myocardial Hypertrophy and Heart Failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011, 51, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Chai, L.; Chen, H.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Shen, N.; Zhang, J.; et al. Activation of CaMKII/HDAC4 by SDF1 Contributes to Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension via Stabilization Runx2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 970, 176483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik-Pszczoła, K.; Chłoń-Rzepa, G.; Jankowska, A.; Ślusarczyk, M.; Ferdek, P.E.; Kusiak, A.A.; Świerczek, A.; Pociecha, K.; Koczurkiewicz-Adamczyk, P.; Wyska, E.; et al. A Novel, Pan-PDE Inhibitor Exerts Anti-Fibrotic Effects in Human Lung Fibroblasts via Inhibition of TGF-β Signaling and Activation of cAMP/PKA Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Tu, L.; Guignabert, C.; Merkus, D.; Zhou, Z. Purinergic Dysfunction in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e017404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, T.C.J.; Hanmandlu, A.; Tu, L.; Phan, C.; Collum, S.D.; Chen, N.-Y.; Weng, T.; Davies, J.; Liu, C.; Eltzschig, H.K.; et al. Switching-Off Adora2b in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Halts the Development of Pulmonary Hypertension. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmouty-Quintana, H.; Philip, K.; Acero, L.F.; Chen, N.-Y.; Weng, T.; Molina, J.G.; Luo, F.; Davies, J.; Le, N.-B.; Bunge, I.; et al. Deletion of ADORA2B from Myeloid Cells Dampens Lung Fibrosis and Pulmonary Hypertension. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2015, 29, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puertas-Umbert, L.; Alonso, J.; Hove-Madsen, L.; Martínez-González, J.; Rodríguez, C. PDE4 Phosphodiesterases in Cardiovascular Diseases: Key Pathophysiological Players and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beca, S.; Helli, P.B.; Simpson, J.A.; Zhao, D.; Farman, G.P.; Jones, P.; Tian, X.; Wilson, L.S.; Ahmad, F.; Chen, S.R.W.; et al. Phosphodiesterase 4D Regulates Baseline Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Release and Cardiac Contractility, Independently of L-Type Ca2+ Current. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 1024–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growcott, E.J.; Spink, K.G.; Ren, X.; Afzal, S.; Banner, K.H.; Wharton, J. Phosphodiesterase Type 4 Expression and Anti-Proliferative Effects in Human Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells. Respir. Res. 2006, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, P.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Ma, L.; Ge, R. Tibetan Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Alleviate Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling in Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension Rats. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio 2024, 42, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, D.; Shen, Y.; Huang, H.; Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Yu, Y.; Yu, Y.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Nanovesicles as a Credible Agent for Therapy of Pulmonary Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 67, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-H.; Liang, J.-P.; Zhu, C.-J.; Lian, Y.-J. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Therapy for Pulmonary Hypertension: A Comprehensive Review of Preclinical Studies. J. Intervent. Cardiol. 2022, 2022, 5451947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.T.; Braga, C.L.; de Sá Freire Onofre, M.E.; da Silva, C.M.; de Novaes Rocha, N.; Veras, R.G.; de Souza Serra, S.S.; Teixeira, D.E.; dos Santos Alves, S.A.; Miranda, B.T.; et al. Cardioprotective Effects of Extracellular Vesicles from Hypoxia-Preconditioned Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Experimental Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, J.R.; Pereira, M.; Del Tatto, M.; Brodsky, A.S.; Wu, K.Q.; Dooner, M.S.; Borgovan, T.; Wen, S.; Goldberg, L.R.; Aliotta, J.M.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Extracellular Vesicles Reverse Sugen/Hypoxia Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y.; Luo, F.; Zhou, J.; Xu, F. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Prevent the Formation of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension through a microRNA-200b-Dependent Mechanism. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, G.; Chouvarine, P.; Diekmann, F.; Giera, M.; Ralser, M.; Mülleder, M.; von Kaisenberg, C.; Bertram, H.; Legchenko, E.; Hass, R. Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Treatment of Severe Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 1, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, A.K.N.; Pimentel-Coelho, P.M.; Montes, G.C.; da Silva, M. de M.C.; Mendes, L.V.P.; Montagnoli, T.L.; Silva, A.M.S.; Vasques, J.F.; Rosado-de-Castro, P.H.; Gutfilen, B.; et al. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy Reverses Su5416/Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Jung, J.-H.; Ahn, K.-J.; Jang, A.Y.; Byun, K.; Yang, P.C.; Chung, W.-J. Stem Cell and Exosome Therapy in Pulmonary Hypertension. Korean Circ. J. 2022, 52, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Badesch, D.B.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Gibbs, J.S.R.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Preston, I.R.; Souza, R.; Waxman, A.B.; Moles, V.M.; et al. Sotatercept in Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension at High Risk for Death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1987–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewehr, D.M.; Salgueiro, G.R.; Noronha, L. de; Kubrusly, F.B.; Kubrusly, L.F.; Coltro, G.A.; Preto, P.C.; Bertoldi, A. de S.; Vieira, H.I. Plexiform Lesions in an Experimental Model of Monocrotalin-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2020, 115, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urboniene, D.; Haber, I.; Fang, Y.-H.; Thenappan, T.; Archer, S.L. Validation of High-Resolution Echocardiography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging vs. High-Fidelity Catheterization in Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. - Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2010, 299, L401–L412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).