1. Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) due to pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS) is a life-threatening disease, which mainly affects the pediatric population[

1]. This type of PH, that ultimately results in a left ventricular inflow tract obstruction, is classified under type II PH [

2]. PVS presents mostly with congenital heart defects (univentricular heart disease, ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect or persistent arterial duct), lung disease (bronchopulmonary dysplasia) or Down syndrome or other trisomy [

3,

4]. In rare cases, PVS can also occur in adults because of radiofrequency ablation therapy post atrial fibrillation[

5]. This type of PH is characterized by initial passive increase in pressure due to increased resistance resulting in increased mean pulmonary artery pressure and is followed by vascular remodeling leading to in increased in pulmonary vascular resistance and a further increase in pressure. Surgical interventions and/or stenting of the lesions in patients with PVS frequently lead to restenosis, and use of vasodilators comes with the risk for pulmonary edema[

6]. The complex molecular mechanisms involved in PH are the limiting factors in the development of novel therapeutic interventions.

Previous work by our group has shown that endothelial factors are important in development of PH in a swine model using pulmonary vein banding (PVB) of the lower lobes for 12 weeks to induce type II PH [

7]. This procedure results in areas of the lung with a varied hemodynamic profile within the lung; the lower lobes experience high pressure and low flow (HF/LF) whereas the upper lobes experience high pressure and high flow (HP/HF). High and low shear stress have very striking effects on the endothelial cells of the lung vasculature. Endothelial cells typically respond to high shear stress with strong nitric oxide synthesis, but "activate" a pro-inflammatory profile at low shear stress, characterized by low nitric oxide production[

8]. In this current study, we conducted a quantitative LC-MS/MS based proteomic analysis of lung samples along with untargeted metabolomics from swine with PVB and Control (Cntrl) swine. We analyzed the tissues from upper and lower lobes to investigate how different hemodynamic profiles impact protein and metabolite expression due to PH in the lobes.

3. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

The main findings in this study were that (i) chronic alterations in flow and pressure induced by PVB impact the proteomic and metabolomic profile in the lung tissue and result in increased ECM and collagen production in lobes with both HP/HF and HP/LF; (ii) upper lung lobes with HP/HF adapt by altering the fatty acid metabolism as well as ROS signaling and (iii) the lower lobes with HP/LF increase their purine metabolism in order to cope with increased demand of cellular proliferation (

Figure 8).

We have previously demonstrated that PH caused by pulmonary vein stenosis results in a progressive increase in pulmonary vascular resistance, which is accompanied by functional (increased contribution of endothelin, phosphodiesterase 5) as well as structural (increased media thickness) pulmonary vascular remodeling [

7],[

20]. Banding of the confluent of the veins from the lower lobes results in areas of the lungs with distinct hemodynamic profiles, HP/HF in the unbanded upper lobes, and HP/LF in the banded lobes. This model is therefore well-suited to study mechano-metabolic coupling and its role in pulmonary vascular remodeling in PH, as it has been demonstrated that metabolic and structural changes are coupled to each other [

21]. Here, we present a thorough proteome and metabolome profile analysis of lung tissue with these distinct mechanical profiles. Pathway enrichment analysis in PVB animals demonstrated changes in several pathways that have been associated with the progression of PH. Thus, alterations were observed for extracellular matrix proteins involving integrins, matrix metalloproteases, collagen, vitronectin, serpins, and others observed in both lobes of the animals. This is in accordance with our histological data, suggesting increased ECM deposition around the vessels. We also detected high amounts of phospatidylcholine (PC) as well as prostaglandins which indicate plasma membrane break and inflammatory signaling due to high shear stress[

22]. In line with these findings, the comparison with the lung matrix database revealed that further extracellular matrix proteins were altered in upper and lower lobes of PVB swine (

Supplementary Figure S1A). ECM proteins such as FGB, COL1A, COL15A1 were significantly upregulated in the PVB lower lobe whereas in the upper lobe the analysis revealed synergistic downregulation of extracellular proteolytic proteins such as MMP9 and Serpins[

23],[

24].

Strikingly, proteins of the apolipoprotein-family were significantly altered in abundance in PVB animals. The key protein component of HDL-C, apolipoprotein A (APOA), which was downregulated in the upper lobe, was not shown to be differentially regulated in the lower lobe. Downregulation of APOA1 is in accordance with data showing that ApoA-1 is less prevalent in PH, which contributes to oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction[

25]. Furthermore, administration of a peptide mimetic of ApoA-1 reduced pulmonary hypertension in rodent models with PH[

26]. Along with ApoA, we also detected significantly reduced levels of ApoE at the proteomics as well as at the transcription level in the PVB upper lobe. The metabolomics data in the upper lobe further point to an ongoing alteration of lipid homeostasis and detected increased fatty acids such as oleic acid, linoleic acid, arachidonic acid and palmitic acid in the PVB group, indicate a reduced uptake of fatty acids due to decreased levels of apolipoproteins [

27]. High amounts of linoleic and oleic acids have been found to significantly lower nitric oxide (NO) levels in endothelial cells and exert their deleterious effects via ROS [

28]–[

30]. It has been shown that HIF-1α activation, a common dysregulated pathway in PH and lung diseases, can inhibit β-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids leading to accumulation of fatty acids[

31]. However, we did not detect increased accumulation of Carnitine and acyl-carnitine that reflects inhibition of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation and has been previously shown to be involved in the development of PH [

32].

In keeping with studies from Umar et al. who showed higher oxidized LDL in lungs and plasma in PH with decrease in CD36, our proteomic analysis did detect modifications of pathways regulating cholesterol levels consisting primarily of downregulation of fatty acid transporters such CD36 and LDLRAP1 [

33] . Along with this we detected significant upregulation of the protein LDLR in the PVB upper lobe. LDLR mainly binds to apolipoprotein B100 (APOB) and APOE to clear cholesterol from blood[

34]. Both ApoB and ApoE are high-affinity ligands for LDLR and are expressed in various immune and vascular cells[

34],[

35]. Negative feedback inhibition from transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms closely controls the LDLR pathway and disruption of this tightly controlled pathway can influence lipid and cholesterol regulation[

36]. These data are also in accordance to integrated proteomic and metabolomics data on HUVECs presented by Venturini et al. showing that high shear upregulates the lipoprotein metabolism and increases expression of LDLR[

37].

Additionally, we found metabolites such as Oxaloacetic acid and L-Malic acid, both intermediate products of the TCA cycle, to be enriched in the PVB upper lobe along with decreased glucose. These metabolites take part in anaplerotic reactions where the intermediate metabolites exit the TCA cycle and are used by proliferating cells due to an increased demand for protein and fatty acids in PH[

21]. These data support the presence of the Warburg effect, showing that glucose metabolism is increased in PH [

32], [

38],,[

39]. Further evidence for this Warburg effect is the lower amount of NADP in the PVB upper lobe. NADP maintains the redox balance in the cells and supports the biosynthesis of the fatty acids and is essential for maintaining a large number of biological processes[

40]. In agreement with this finding, Nukula et al. reported a lower NADPH/NADP ratio in CTEPH patients' endothelial cells compared to healthy subjects, implying increased oxidative stress and endothelial cell dysfunction[

41].

A key metabolite which was downregulated in the PVB upper lobe and deemed important from our network analysis was S-Adenosylhomocysteine (SAH). Asymmetric Dimethyl arginine (ADMA), a negative regulator of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, is formed by hydrolysis of methylated proteins and the methylated proteins are derived when S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) is converted to SAH. We also simultaneously observed increased aspartic arginine (VIP > 1, Suppl data 2 table S2) in the upper lobe PVB which is a source of NO in endothelial cells[

33],[

43] . In our previous work we have shown NO production is increased in HP/HF areas, likely as a compensatory mechanism to maintain vasodilation[

20]. Our current data suggest that low SAH, and hence low ADMA, in combination with high arginine, the substrate for endothelial NO synthesis, facilitates the NO synthesis in the PVB upper lobe vasculature.

Notably, proteomic and metabolic alterations were less pronounced between PVB and Cntrls in the lower lobes. The STRING analysis points to reduced glucose synthesis in the PVB lower lobes, which supports the notion that glycolysis predominates over other metabolic activities in PH in the lower lobes as well[

32]. Another intriguing observation was that the purine pathway metabolites adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and guanosine monophosphate (GMP) were significantly enriched, and the enzyme guanosine monophosphate reductase (GMPR), which converts GMP to IMP, was downregulated. Additionally, our proteome data revealed that the PVBs had a decreased abundance of the enzyme HPRT, which transforms hypoxanthine into inosine monophosphate and is crucial for salvage pathway for recycling nucleotides[

44]. We also found more inosine in the metabolome of lower lobe PVBs, which indicated that there, cells increased de novo purine production rather than using the standard active salvage pathway. These data are consistent with the study by Hautbergue et al., where modifications to the purine metabolic pathway in the right ventricle and plasma of PH rats were shown [

45]. The purine metabolite levels in endothelial cells from PAH patients have also been found to be higher, the same was true for the serine to glycine ratio, which is mediated by the mitochondrial enzyme Serine hydroxymethytransferase (SHMT) [

46]. Although SHMT was unchanged in our lung tissue samples, we did observe an increase in the metabolite serine (VIP>1) in the PVB lower lobes. Moreover, in atherosclerosis models, it has been shown that vessels with low flow and shear stress have decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) along with increased cell proliferation and collagen deposition [

47].

4. Materials and Methods

Lung tissue was used from experiments that have previously been published [

7],[

20]. These experiments followed the "Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals," which are endorsed by the Council of the American Physiological Society, and the protocol was approved by the Animal Care Committee at Erasmus University Medical Centre (EMC3158,109-13-09).

4.1. Outline of Study

For all surgical procedures, swine were sedated with an intramuscular injection of a mixture of tiletamine/zolazepam (5 mg kg−1, Virbac, Barneveld, the Netherlands), xylazine, (2.25 mg kg−1, AST Pharma, Oudewater, the Netherlands) and atropine (0.5 mg), intubated and ventilated (O2:N2 (1:2)). Isoflurane (2% vol/vol, Pharmachemie, Haarlem, the Netherlands) was added to the gas mixture to induce anesthesia. Post-surgical analgesia was administered by means of an i.m. injection (0.3 mg buprenorphine i.m. Indivior, Slough, UK) and a fentanyl slow-release patch (6 or 12 μg h−1 depending on body weight), 72 h).

Crossbred Landrace x Yorkshire pigs of either sex (8±2 kg) underwent non-restrictive inferior pulmonary vein banding (n = 7) via the third right intercostal space [

7], [

20] or a sham procedure (n = 6). All 13 animals, underwent chronic instrumentation 4 weeks later, enabling hemodynamic assessments on awake animals. Following a left-sided thoracotomy in the fourth intercostal space, fluid-filled catheters (Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA), were inserted in the aorta, the pulmonary artery, the left and right ventricle and the left atrium for measurement of blood pressure. A flow probe (20PAU, Transonic systems, Ithaca, NY, USA) was placed around the ascending aorta for measurement of cardiac output. Aorta flow was indexed to bodyweight. Total pulmonary vascular resistance index (tPVRi) was calculated as the ratio of mPAP and Cardiac index while pulmonary vascular compliance was calculated as stroke volume index/ (systolic PAP-diastolic PAP). Hemodynamics were recorded (WinDaq, Dataq instruments) in the awake state, with swine standing quietly, and analyzed off-line using a custom written program (Matlab, The MathWorks).

Twelve weeks after the PVB procedure, swine were re-anesthetized, the thorax was opened using sternotomy, and heart and lungs were excised, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and processed for further analysis.

4.2. Real time quantitative PCR of lung tissue

Lung tissue was snap frozen and 30 mg of tissue was homogenized and mRNA was extracted using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA was made using 500ng of mRNA and the SenSi FAST cDNA synthesis kit (Bioline, UK). Target genes were normalized against Beta actin and cyclophilin using the CFX manager software (BioRad). Relative gene expression was calculated using delta delta Ct method.

4.3. Proteomics

4.3.1. Sample preparation for proteome analysis

Frozen lung tissue samples were placed into pre-cooled tubes and cryo-pulverized in a CP02 Automated Dry Pulverizer (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA) with an impact level of 5 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue lysis was performed in 8 M urea/0.5 M NH4HCO3 with ultrasonication (18 cycles of 10 s) using a Sonopuls HD3200 (Bandelin, Berlin, Germany). Total protein concentration was quantified using Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Fifty micrograms of protein were digested sequentially, firstly with Lys-C (FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals Europe GmbH, Neuss, Germany) for 4 h and subsequently with modified porcine trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) for 16 h at 37°C.

4.3.2. Nano-liquid chromatography (LC)–tandem mass spectrometry (MS) analysis and bioinformatics

MS data acquisition and data analysis were performed similarly as described in (Stirm et al., 2021). Briefly, 1 μg of the digest was injected on an UltiMate 3000 nano-LC system coupled online to a Q Exactive HF-X instrument operated in the data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. Peptides were transferred to a PepMap 100 C18 trap column (100 µm×2 cm, 5 µM particles, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and separated on an analytical column (PepMap RSLC C18, 75 µm×50 cm, 2 µm particles, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 250 nl/min flow-rate with a 160-min gradient of 3-25% of solvent B followed by 10-min ramp to 40% and 5-min ramp to 85%. Solvent A consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water and solvent B of 0.1% FA in acetonitrile. MS spectra were acquired using a top 15 data-dependent acquisition method on a Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer. Protein identification was done using MaxQuant (v.1.6.7.0)[

9] (Tyanova et al., 2016) and the NCBI RefSeq Sus scrofa database (v.7-5-2020). All statistical analyses and data visualization were performed using R CORE team[

10] . Prior to statistical analysis, potential contaminants, only identified by site and reverse hits were excluded. Proteins with at least two peptides detected in at least three samples of each condition were quantified using the MS-EmpiRe algorithm as previously described [

11,

12]. R script used for quantitative analysis is available at

https://github.com/bshashikadze/pepquantify. Proteins with a Benjamini–Hochberg corrected P-value ≤ 0.05 and fold-change ≥ 1.5 were regarded as significantly altered. Pre-ranked gene set enrichment analysis using STRING was employed to reveal biological processes related to differentially abundant proteins[

13]. Signed (based on fold-change) and log-transformed p-values were used as ranking metrics and false discovery rate was set to 1%. The redundancy of the significantly enriched biological processes were minimized using REVIGO tool [

14].

4.4. Metabolomics:

Approximately 50 mg sample material was weighed in a 2 mL bead beater tube (CKMix , Bertin Technologies, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) filled with 2.8 mm and 5.0 mm ceramic beads. Then, 1 mL of a methanol/water mixture (70/30, v/v) was added and the samples were extracted with a bead beater (Precellys Evolution, Bertin Technolgies) supplied with a Cryolys cooling module 3 times each for 20 seconds with 15 seconds breaks in between at 10.000 rpm. After centrifugation at 13.000 U/min for 10 min the supernatants were dried by vacuum centrifugation, suspended in 150 µL of methanol/water (70/30, v/v) and subjected to MS analysis.

Untargeted analysis was carried out on a Nexera UHPLC system connected to a Q-TOF mass spectrometer (TripleTOF 6600, AB Sciex). Chromatographic separation was achieved by using a HILIC UPLC BEH Amide 2.1x100, 1.7 µm column with 0.4 mL/min flow rate. The mobile phase consisted 5 mM ammonium acetate in water (eluent A) and 5 mM ammonium acetate in acetonitrile/water (95/5, v/v) (eluent B). The following gradient profile was used: 100% B from 0 to 1.5 min, 60% B at 8 min and 20% B at 10 min to 11.5 min and 100% B at 12 to 15 min. Aliquots of 5µL per sample were injected into the UHPLC-TOF-MS. The autosampler was cooled to 10°C and the column oven heated to 40°C. A quality control (QC) sample was pooled from all samples and injected after every 10 samples. MS settings in the positive mode were as follows: Gas 1 55, Gas 2 65, Curtain gas 35, Temperature 500°C, Ion Spray Voltage 5500, declustering potential 80. The mass range of the TOF-MS scans were 50 - 2000 m/z and the collision energy was ramped from 15 - 55 V. MS settings in the negative mode were as follows: Gas 1 55, Gas 2 65, Cur 35, Temperature 500°C, Ion Spray Voltage -4500, declustering potential -80. The mass range of the TOF-MS scans were 50 - 2000 m/z and the collision energy was ramped from -15 - -55 V.

The "msconvert" from ProteoWizard [

15] was used to convert raw files to mzXML (de-noised by centroid peaks). The bioconductor/R package xcms [

16] was used for data processing and feature identification. More specifically, the matched Filter algorithm was used to identify peaks (full width at half maximum set to 7.5 seconds). Then the peaks were grouped into features using the "peak density" method[

16]. The area under the peak was integrated to represent the abundance of features. The retention time was adjusted based on the peak groups presented in most samples. To annotate features with names of metabolites, the exact mass and MS2 fragmentation pattern of the measured features were compared to the records in HMBD[

17] and the public MS/MS spectra in MSDIAL[

18], referred to as MS1 and MS2 annotation, respectively. Missing values were imputed with half of the limit of detection (LOD) methods, i.e., for every feature, the missing values were replaced with half of the minimal measured value of that feature in all measurements. To confirm that a MS2 spectra is well annotated, we manually reviewed our MS2 fragmentation pattern and compared it with records in the public database or previously measured reference standards to evaluate the correctness of the annotation.

MetaboAnalyst 5.0 platform was utilized to conduct multivariate data analysis, for PCA and OPLS-DA. The contribution of each variable to the classification was indicated by the VIP value that was calculated in the OPLS-DA model after Pareto scaling. The student’s t-test at the univariate level was further employed to measure the significance of metabolites with VIP > 1.0. Metabolites with the P-value < 0.1 were considered as differential metabolites, while those with the P-value < 0.05 were recognized as statistically significant differential metabolites. Enrichment analysis and Network analysis was performed using only the significant metabolites and significant genes using KEGG pathway database.

Figure 1.

Pulmonary vein banding causes PH (A) Angiogram of the Inferior venous confluent of a representative Control (Cntrl, top) and PVB animal (bottom). (B, C) Picrosirius red staining of the lung upper and lower lobe in Cntrl and PVB animals. (D, E, F) mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP), total pulmonary vascular resistance index (tPVRi) and pulmonary artery compliance in awake resting swine. Values are means ± SEM. * p ≤ 0.05. PVB vs. Control by Student’s t-test PVB, n = 6, Cntrl=7.

Figure 1.

Pulmonary vein banding causes PH (A) Angiogram of the Inferior venous confluent of a representative Control (Cntrl, top) and PVB animal (bottom). (B, C) Picrosirius red staining of the lung upper and lower lobe in Cntrl and PVB animals. (D, E, F) mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP), total pulmonary vascular resistance index (tPVRi) and pulmonary artery compliance in awake resting swine. Values are means ± SEM. * p ≤ 0.05. PVB vs. Control by Student’s t-test PVB, n = 6, Cntrl=7.

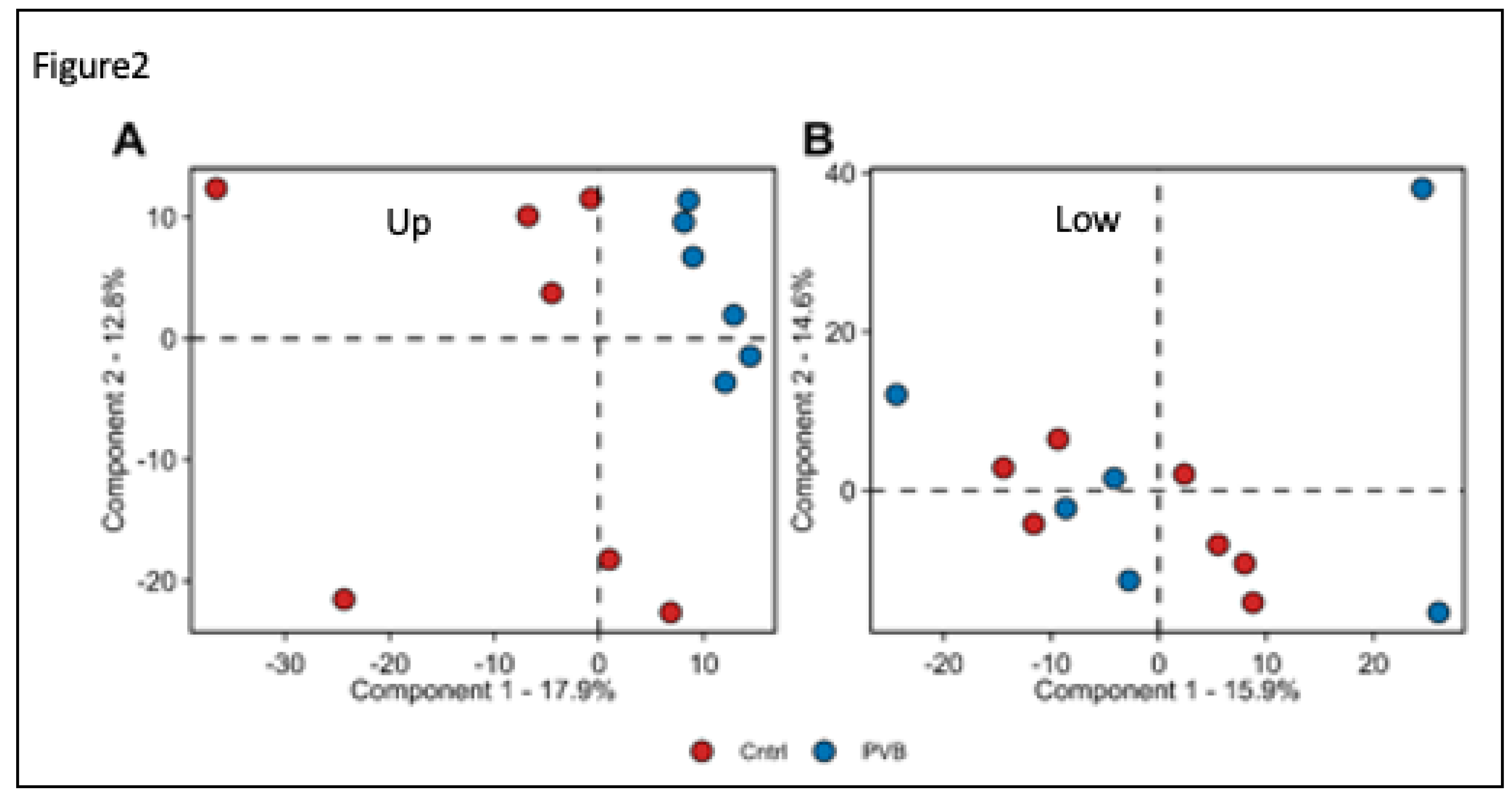

Figure 2.

Proteomic analysis of Lung tissue of PVB vs Control (Cntrl) animals (A, B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of proteome profiles from upper (A) and lower (B) lobe of Cntrl (n= 7) and PVB animals (n=6).Colored circles indicate individual animals. Red filled circles are Cntrl and Blue filled circles are PVB animals.

Figure 2.

Proteomic analysis of Lung tissue of PVB vs Control (Cntrl) animals (A, B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of proteome profiles from upper (A) and lower (B) lobe of Cntrl (n= 7) and PVB animals (n=6).Colored circles indicate individual animals. Red filled circles are Cntrl and Blue filled circles are PVB animals.

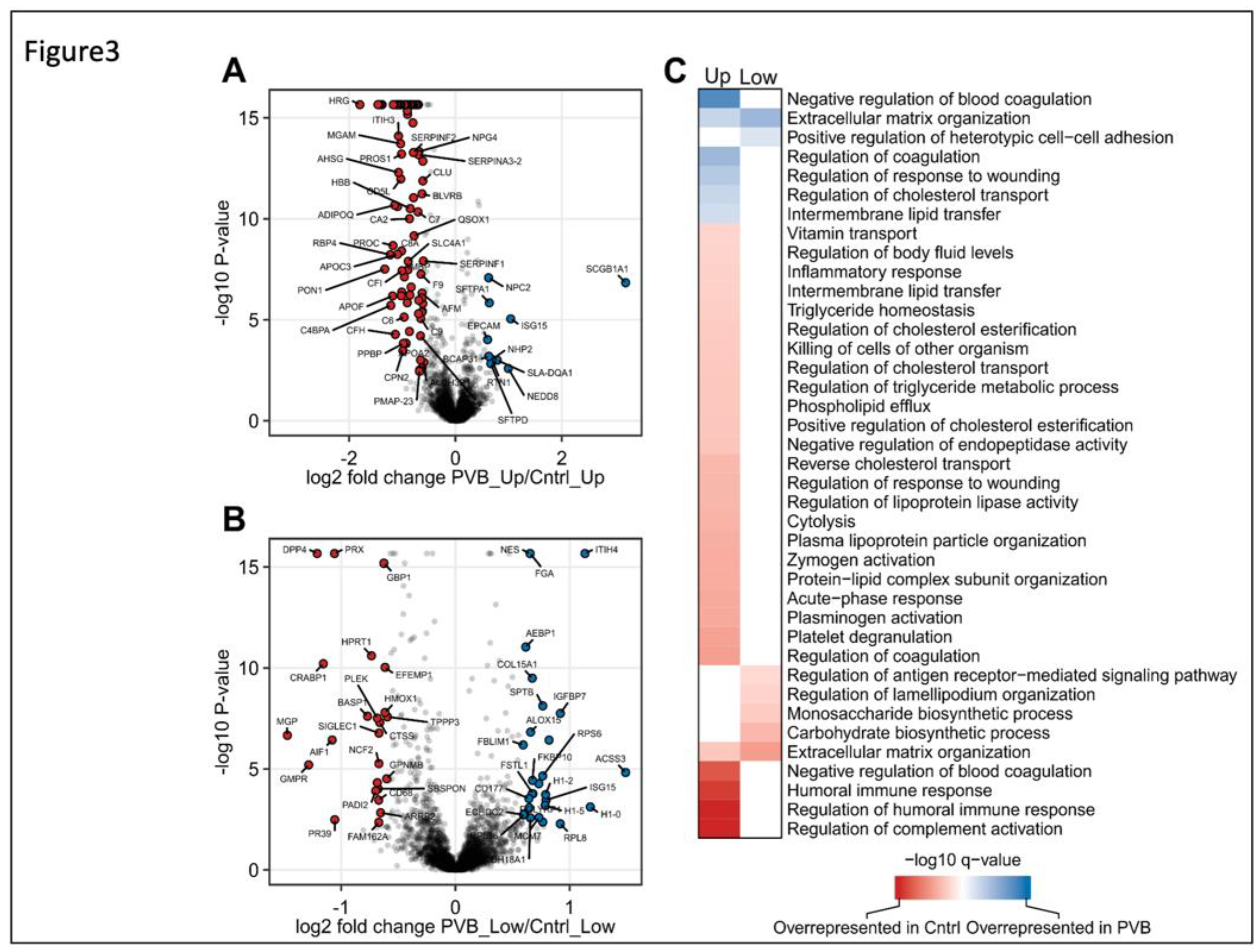

Figure 3.

Quantitative and functional analysis of upper and lower lobe PVB vs Cntrl animals (A, B) The quantitative proteome alterations is visualized via Volcano plots in upper and lower lobes, respectively from PVB vs. Cntrl pigs. Color filled circles (Blue upregulated, red downregulated) indicate differentially abundant proteins (Benjamini–Hochberg corrected P-value ≤ 0.05 and fold-change ≥ 1.5). (C) Functional characterization of differences between upper and lower lobes in PVB and Cntrl animals. Heatmap shows GO-term enrichment in PVB compared to Cntrl.

Figure 3.

Quantitative and functional analysis of upper and lower lobe PVB vs Cntrl animals (A, B) The quantitative proteome alterations is visualized via Volcano plots in upper and lower lobes, respectively from PVB vs. Cntrl pigs. Color filled circles (Blue upregulated, red downregulated) indicate differentially abundant proteins (Benjamini–Hochberg corrected P-value ≤ 0.05 and fold-change ≥ 1.5). (C) Functional characterization of differences between upper and lower lobes in PVB and Cntrl animals. Heatmap shows GO-term enrichment in PVB compared to Cntrl.

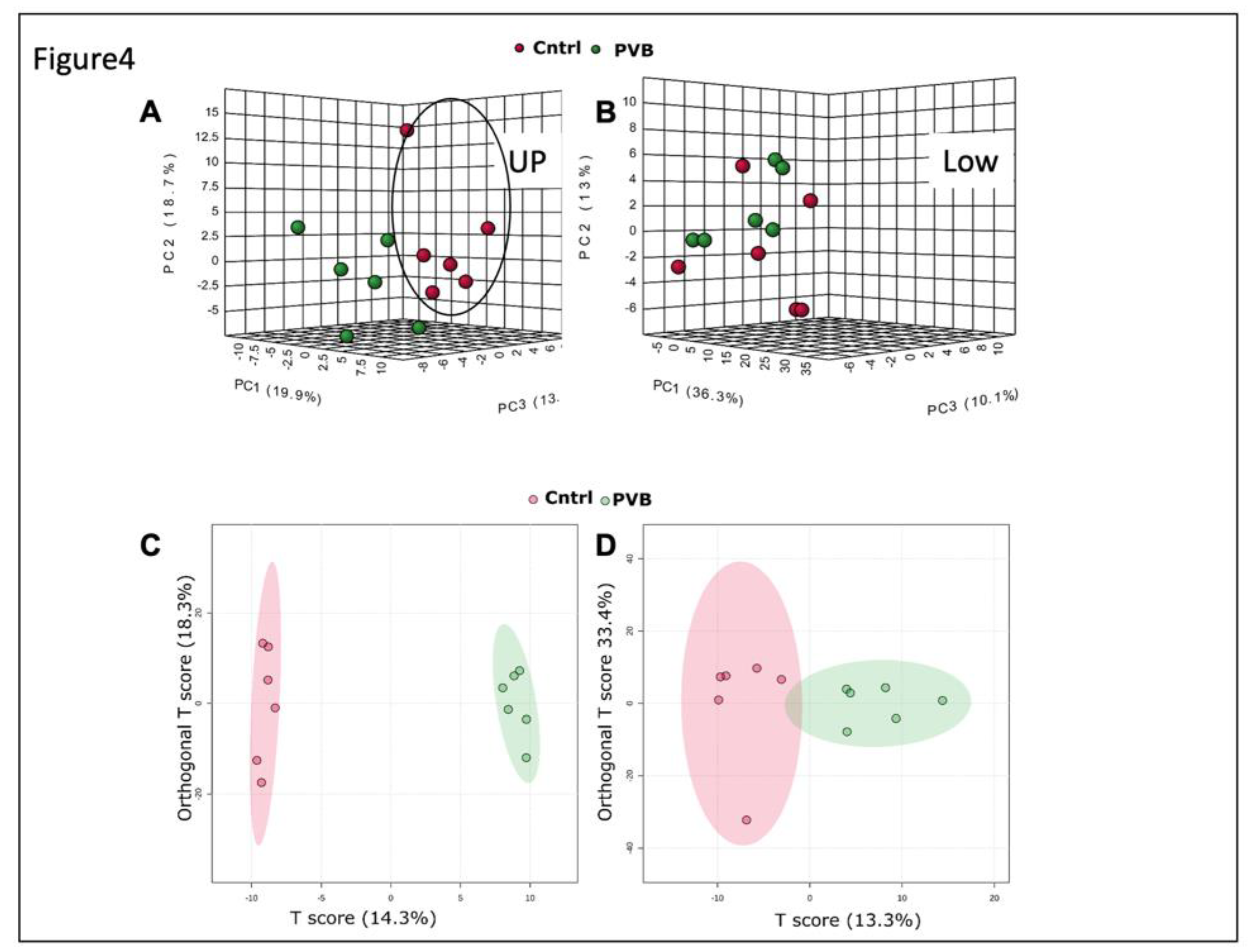

Figure 4.

Metabolomic analysis in the upper and lower lobe of PVB vs Cntrl animals. (A, B) 3D PCA analysis based on metabolic profiles of PVB and Cntrl animals in upper and lower lobe in negative mode (HILIC). (C, D) Ortho PLS-DA analysis based on metabolic profiles of PVB and Cntrl animals in upper and lower lobe in negative mode (Hilic). n=6 in each group.

Figure 4.

Metabolomic analysis in the upper and lower lobe of PVB vs Cntrl animals. (A, B) 3D PCA analysis based on metabolic profiles of PVB and Cntrl animals in upper and lower lobe in negative mode (HILIC). (C, D) Ortho PLS-DA analysis based on metabolic profiles of PVB and Cntrl animals in upper and lower lobe in negative mode (Hilic). n=6 in each group.

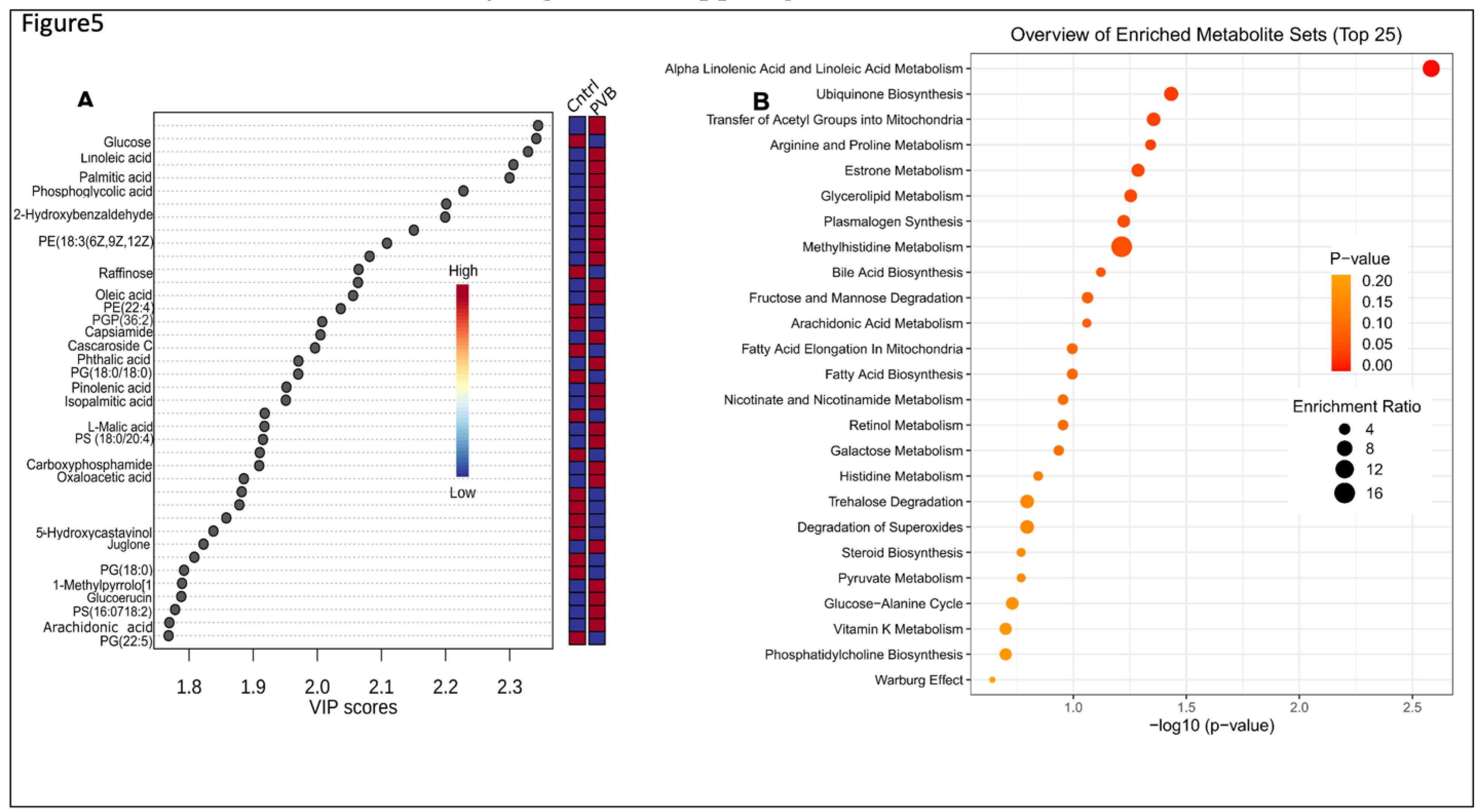

Figure 5.

Metabolomic analysis in the upper lobe of PVB vs Cntrl animals. (A,) Metabolites ranked by Variable importance in the projection score (VIP)>1 in PVB vs Cntrl pigs in upper lobes based on OPL- DA analysis. (B) Pathway analysis based on KEGG database of the enriched metabolites (VIP>1 and P value <0.05 in the upper lobe PVB vs Cntrl swine. n=6 in each group. The size of the dots represents the enrichment ratio and the shade of the color represent the -log 10(P value).

Figure 5.

Metabolomic analysis in the upper lobe of PVB vs Cntrl animals. (A,) Metabolites ranked by Variable importance in the projection score (VIP)>1 in PVB vs Cntrl pigs in upper lobes based on OPL- DA analysis. (B) Pathway analysis based on KEGG database of the enriched metabolites (VIP>1 and P value <0.05 in the upper lobe PVB vs Cntrl swine. n=6 in each group. The size of the dots represents the enrichment ratio and the shade of the color represent the -log 10(P value).

Figure 6.

Interaction network analysis of the metabolites and proteins from metabolomics and proteomics. (A) Metabolite-metabolite interaction network for the most enriched metabolites in the upper lobe of PVB vs Cntrl. Labelled and red filled circles represent the upregulated metabolites and green filled circles represent the downregulated metabolites detected in the PVB group. Metabolites clustered in green background represent metabolites participating in fatty acid metabolism, red background- in ROS pathway; Blue- ECM remodeling and Yellow- glucose metabolism. (B) Gene- metabolite network analysis for the significantly altered proteins and enriched metabolites for upper lobe of PVB vs Cntrl. The red filled squares represent the downregulated proteins and green filled circles represent the upregulated metabolites detected in the PVB group. Metabolites of VIP>1 with P-value < 0.05 and proteins with fold-change > 1.3 and Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted P-value < 0.05 were used for the analysis. The proteins and metabolites belonging to one GO term are encircled together.

Figure 6.

Interaction network analysis of the metabolites and proteins from metabolomics and proteomics. (A) Metabolite-metabolite interaction network for the most enriched metabolites in the upper lobe of PVB vs Cntrl. Labelled and red filled circles represent the upregulated metabolites and green filled circles represent the downregulated metabolites detected in the PVB group. Metabolites clustered in green background represent metabolites participating in fatty acid metabolism, red background- in ROS pathway; Blue- ECM remodeling and Yellow- glucose metabolism. (B) Gene- metabolite network analysis for the significantly altered proteins and enriched metabolites for upper lobe of PVB vs Cntrl. The red filled squares represent the downregulated proteins and green filled circles represent the upregulated metabolites detected in the PVB group. Metabolites of VIP>1 with P-value < 0.05 and proteins with fold-change > 1.3 and Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted P-value < 0.05 were used for the analysis. The proteins and metabolites belonging to one GO term are encircled together.

Figure 7.

Fatty acid uptake pathway in the upper lobe at protein and mRNA level (A) Protein abundance of apolipoproteins significantly changed (Benjamini–Hochberg corrected P-value ≤ 0.05) in PVB compared to Cntrls in upper and lower lobes are depicted as dots. n= 6 per group. (B-E) mRNA level of APOA, APOE, CD36 and LDLR respectively are expressed relative to the mean expression of the sham animals (Values are mean +/- SEM. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 Students’s t-test n=5 animals per group).

Figure 7.

Fatty acid uptake pathway in the upper lobe at protein and mRNA level (A) Protein abundance of apolipoproteins significantly changed (Benjamini–Hochberg corrected P-value ≤ 0.05) in PVB compared to Cntrls in upper and lower lobes are depicted as dots. n= 6 per group. (B-E) mRNA level of APOA, APOE, CD36 and LDLR respectively are expressed relative to the mean expression of the sham animals (Values are mean +/- SEM. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 Students’s t-test n=5 animals per group).

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of the metabolic pathways altered in PVB. The blue labelled metabolites and proteins are detected in the upper lobe which is under high shear stress and green labelled ones are detected in the lower lobe which is under low shear stress. Pathways or metabolites /proteins labeled in red are found to be altered in both the lobes. HA- Hyaluronic acid, 3 PG- Phosphoglyceric acid, SAM- S adenosyl methionine, SAH- S adenosyl homocysteine, NO- Nitric oxide, PC- Phosphatidyl choline, OAA- Oxaloacetic acid.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of the metabolic pathways altered in PVB. The blue labelled metabolites and proteins are detected in the upper lobe which is under high shear stress and green labelled ones are detected in the lower lobe which is under low shear stress. Pathways or metabolites /proteins labeled in red are found to be altered in both the lobes. HA- Hyaluronic acid, 3 PG- Phosphoglyceric acid, SAM- S adenosyl methionine, SAH- S adenosyl homocysteine, NO- Nitric oxide, PC- Phosphatidyl choline, OAA- Oxaloacetic acid.