Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Atherosclerosis: An Overview:

1.2. Caveolae and Caveolins in Vascular Biology

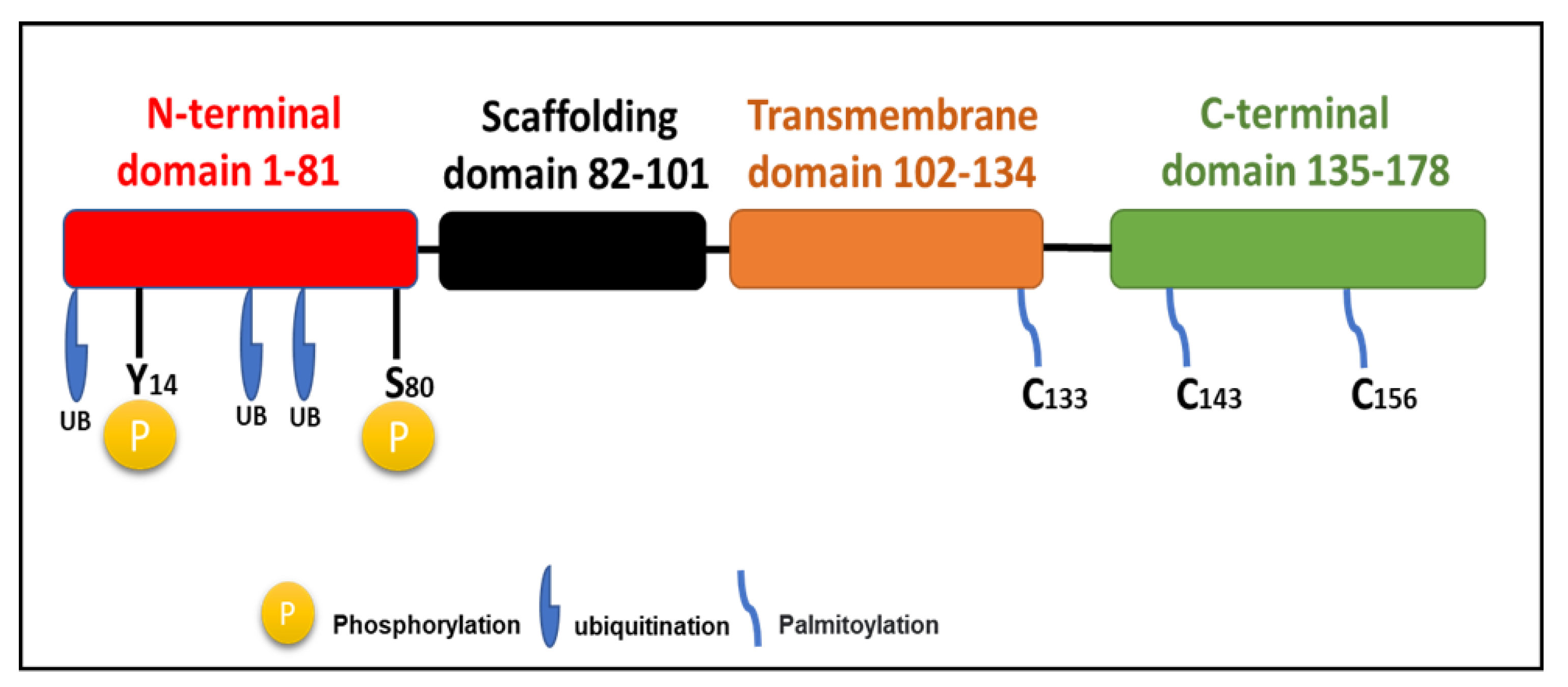

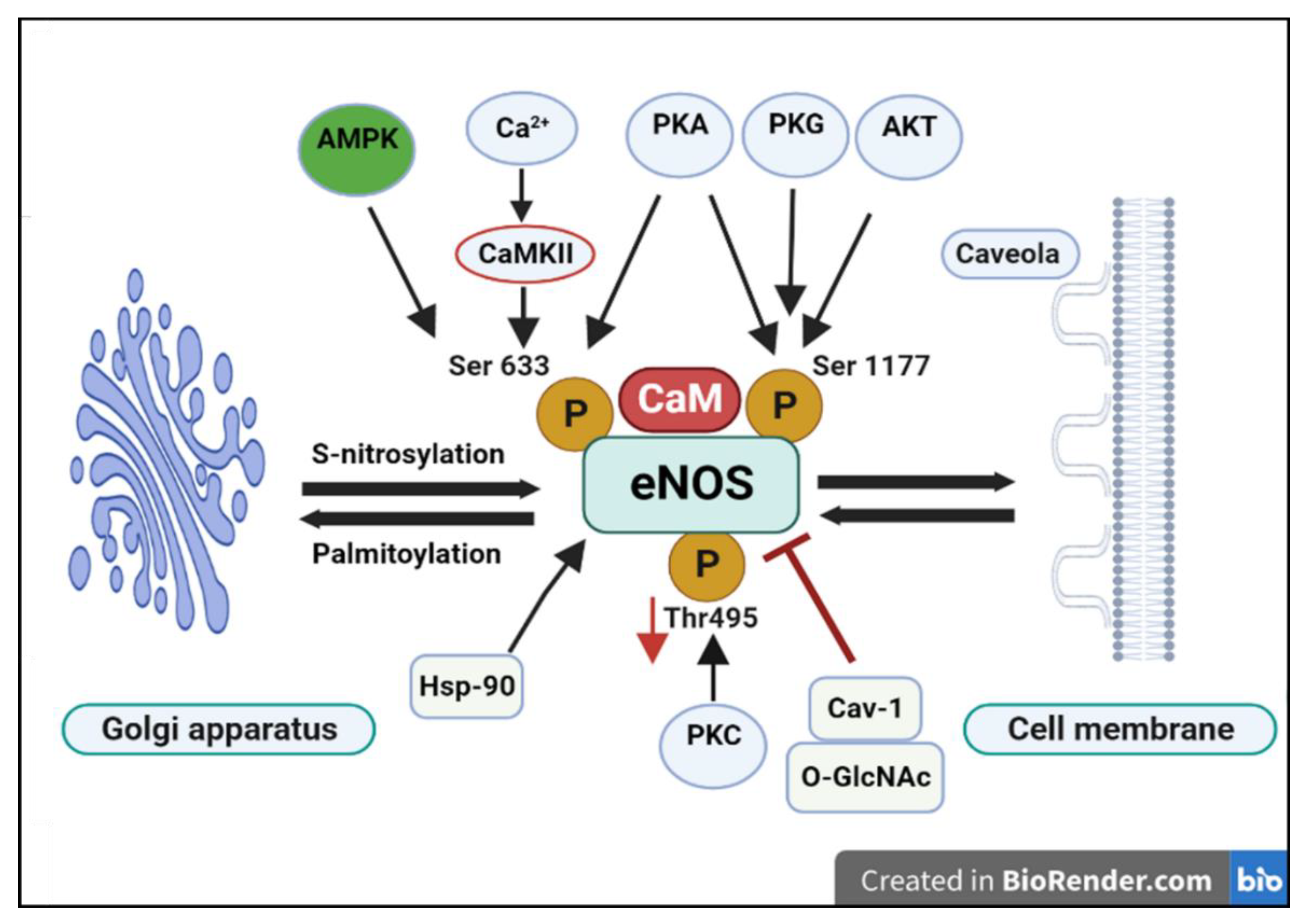

2. Role of Caveolae Microdomains in eNOS Localization and Activity: A Central Regulatory Mechanism

3. The Paradox of Cav-1 in Atherosclerosis: Protective vs. Proatherogenic Roles:

4. PVAT Inflammation and Vascular Dysfunction: Early Event or Late Response?

5. Anti-Atherogenic / Protective Effects of Cav-1

6. Pro-Atherogenic and Pathological Roles of Caveolin-1 (Cav-1)

7. Caveolin-1, PVAT, and Endothelial Dysfunction

| Cell Type | Primary Effect | Mechanisms | Overall Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Cells | Proatherogenic | Increases LDL transcytosis, inhibits eNOS activity, promotes inflammation | Atherosclerosis progression |

| Macrophages | Protective | Regulates cholesterol homeostasis, limits foam cell formation, modulates inflammation | Atherosclerosis suppression |

| Smooth Muscle Cells | Protective | Inhibits proliferation and migration, stabilizes plaques |

8. Conclusion and Therapeutic Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wojtasińska, A., Frąk, W., Lisińska, W., Sapeda, N., Młynarska, E., Rysz, J., & Franczyk, B. (2023). Novel Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(17), 13434. [CrossRef]

- Zubirán, R., Neufeld, E. B., Dasseux, A., Remaley, A. T., & Sorokin, A. V. (2024). Recent Advances in Targeted Management of Inflammation In Atherosclerosis: A Narrative Review. Cardiology and therapy, 13(3), 465–491. [CrossRef]

- YAMADA E. (1955). The fine structure of the gall bladder epithelium of the mouse. The Journal of biophysical and biochemical cytology, 1(5), 445–458. [CrossRef]

- Rothberg, K. G., Heuser, J. E., Donzell, W. C., Ying, Y. S., Glenney, J. R., & Anderson, R. G. (1992). Caveolin, a protein component of caveolae membrane coats. Cell, 68(4), 673–682. [CrossRef]

- Drab, M., Verkade, P., Elger, M., Kasper, M., Lohn, M., Lauterbach, B., Menne, J., Lindschau, C., Mende, F., Luft, F. C., Schedl, A., Haller, H., & Kurzchalia, T. V. (2001). Loss of caveolae, vascular dysfunction, and pulmonary defects in caveolin-1 gene-disrupted mice. Science (New York, N.Y.), 293(5539), 2449–2452. [CrossRef]

- Razani, B., Engelman, J. A., Wang, X. B., Schubert, W., Zhang, X. L., Marks, C. B., Macaluso, F., Russell, R. G., Li, M., Pestell, R. G., Di Vizio, D., Hou, H., Jr, Kneitz, B., Lagaud, G., Christ, G. J., Edelmann, W., & Lisanti, M. P. (2001). Caveolin-1 null mice are viable but show evidence of hyperproliferative and vascular abnormalities. The Journal of biological chemistry, 276(41), 38121–38138. [CrossRef]

- Hwej, A.; Al-Ferjani, A.; Alshuweishi, Y.; Naji, A.; Kennedy, S.; Salt, I.P. Lack of AMP-activated protein kinase-α1 reduces nitric oxide synthesis in thoracic aorta perivascular adipose tissue. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2024, *157*, 107437. [CrossRef]

- Puddu, A., Montecucco, F., & Maggi, D. (2023). Caveolin-1 and Atherosclerosis: Regulation of LDLs Fate in Endothelial Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(10), 8869. [CrossRef]

- Kawabe, J. I., Grant, B. S., Yamamoto, M., Schwencke, C., Okumura, S., & Ishikawa, Y. (2001). Changes in caveolin subtype protein expression in aging rat organs. Molecular and cellular endocrinology, 176(1-2), 91–95. [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. M., & Lisanti, M. P. (2004). The caveolin proteins. Genome biology, 5(3), 214. [CrossRef]

- Fridolfsson, H. N., Roth, D. M., Insel, P. A., & Patel, H. H. (2014). Regulation of intracellular signaling and function by caveolin. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 28(9), 3823–3831. [CrossRef]

- Zipes, D.P.; Jalife, J.; Stevenson, W.G. Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017.

- de Almeida C. J. G. (2017). Caveolin-1 and Caveolin-2 Can Be Antagonistic Partners in Inflammation and Beyond. Frontiers in immunology, 8, 1530. [CrossRef]

- Campos, A., Burgos-Ravanal, R., González, M. F., Huilcaman, R., Lobos González, L., & Quest, A. F. G. (2019). Cell Intrinsic and Extrinsic Mechanisms of Caveolin-1-Enhanced Metastasis. Biomolecules, 9(8), 314. [CrossRef]

- Parton, R. G., & Simons, K. (2007). The multiple faces of caveolae. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology, 8(3), 185–194. [CrossRef]

- Nwosu, Z. C., Ebert, M. P., Dooley, S., & Meyer, C. (2016). Caveolin-1 in the regulation of cell metabolism: a cancer perspective. Molecular cancer, 15(1), 71. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.Y.; Carpentier, J.L.; van Obberghen, E.; Grunfeld, C.; Gorden, P.; Orci, L. Morphological changes of the 3T3-L1 fibroblast plasma membrane upon differentiation to the adipocyte form. J. Cell Sci. 1983, *61*, 219–230.

- Scherer, P. E., Lisanti, M. P., Baldini, G., Sargiacomo, M., Mastick, C. C., & Lodish, H. F. (1994). Induction of caveolin during adipogenesis and association of GLUT4 with caveolin-rich vesicles. The Journal of cell biology, 127(5), 1233–1243. [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Ortega, S., Varela-Guruceaga, M., Algarabel, M., Ignacio Milagro, F., Alfredo Martínez, J., & de Miguel, C. (2015). Effect of TNF-Alpha on Caveolin-1 Expression and Insulin Signaling During Adipocyte Differentiation and in Mature Adipocytes. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology, 36(4), 1499–1516. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A., & Sengupta, D. (2019). Interplay between Membrane Curvature and Cholesterol: Role of Palmitoylated Caveolin-1. Biophysical journal, 116(1), 69–78. [CrossRef]

- Hayer, A., Stoeber, M., Bissig, C. and Helenius, A., 2010. Biogenesis of caveolae: stepwise assembly of large caveolin and cavin complexes. Traffic, 11(3), pp.361-382. [CrossRef]

- Ashford, F., Kuo, C. W., Dunning, E., Brown, E., Calagan, S., Jayasinghe, I., Henderson, C., Fuller, W., & Wypijewski, K. (2024). Cysteine post-translational modifications regulate protein interactions of caveolin-3. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 38(5), e23535. [CrossRef]

- Gokani, S., & Bhatt, L. K. (2022). Caveolin-1: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Diverse Diseases. Current molecular pharmacology, 15(5), 701–715. [CrossRef]

- Huo, J., Mo, L., Lv, X., Du, Y., & Yang, H. (2025). Ion Channel Regulation in Caveolae and Its Pathological Implications. Cells, 14(9), 631. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. Nerve Growth Factor Signaling from Membrane Microdomain to Nucleus: Differential Regulation by Caveolins. Doctoral Dissertation, Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon / East China Normal University, Lyon, France/Shanghai, China, 2012.

- García-Cardeña, G., Martasek, P., Masters, B. S., Skidd, P. M., Couet, J., Li, S., Lisanti, M. P., & Sessa, W. C. (1997). Dissecting the interaction between nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and caveolin. Functional significance of the nos caveolin binding domain in vivo. The Journal of biological chemistry, 272(41), 25437–25440. [CrossRef]

- Razani, B., Woodman, S. E., & Lisanti, M. P. (2002). Caveolae: from cell biology to animal physiology. Pharmacological reviews, 54(3), 431–467. [CrossRef]

- Minetti, C., Sotgia, F., Bruno, C., Scartezzini, P., Broda, P., Bado, M., Masetti, E., Mazzocco, M., Egeo, A., Donati, M. A., Volonte, D., Galbiati, F., Cordone, G., Bricarelli, F. D., Lisanti, M. P., & Zara, F. (1998). Mutations in the caveolin-3 gene cause autosomal dominant limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Nature genetics, 18(4), 365–368. [CrossRef]

- Galbiati, F., Razani, B., & Lisanti, M. P. (2001). Caveolae and caveolin-3 in muscular dystrophy. Trends in molecular medicine, 7(10), 435–441. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., & Ain, R. (2017). Nitric-oxide synthase trafficking inducer is a pleiotropic regulator of endothelial cell function and signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry, 292(16), 6600–6620. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Lian, Y., Wen, X., Guo, J. and Chen, T. (2014) Caveolin-1: an essential modulator of eNOS function and vascular homeostasis. In: Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. [e-book] Vol. 857. Springer, pp. 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Frank P. G. (2010). Endothelial caveolae and caveolin-1 as key regulators of atherosclerosis. The American journal of pathology, 177(2), 544–546. [CrossRef]

- Jia, G., & Sowers, J. R. (2015). Caveolin-1 in Cardiovascular Disease: A Double-Edged Sword. Diabetes, 64(11), 3645–3647. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Wang, B., Jia, L., Yu, H., Wang, Z., Wei, F., & Jiang, A. (2023). Shear stress leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells through the Cav-1-mediated KLF2/eNOS/ERK signaling pathway under physiological conditions. Open life sciences, 18(1), 20220587. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, X. F., González, D. R., Puebla, M., Acevedo, J. P., Rojas-Libano, D., Durán, W. N., & Boric, M. P. (2013). Coordinated endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation by translocation and phosphorylation determines flow-induced nitric oxide production in resistance vessels. Journal of vascular research, 50(6), 498–511. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Couet, J., & Lisanti, M. P. (1996). Src tyrosine kinases, Galpha subunits, and H-Ras share a common membrane-anchored scaffolding protein, caveolin. Caveolin binding negatively regulates the auto-activation of Src tyrosine kinases. The Journal of biological chemistry, 271(46), 29182–29190. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. W., Razani, B., Schubert, W., Williams, T. M., Wang, X. B., Iyengar, P., Brasaemle, D. L., Scherer, P. E., & Lisanti, M. P. (2004). Role of caveolin-1 in the modulation of lipolysis and lipid droplet formation. Diabetes, 53(5), 1261–1270. [CrossRef]

- Bernatchez, P., Sharma, A., Bauer, P. M., Marin, E., & Sessa, W. C. (2011). A noninhibitory mutant of the caveolin-1 scaffolding domain enhances eNOS-derived NO synthesis and vasodilation in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation, 121(9), 3747–3755. [CrossRef]

- Musicki, B., Liu, T., Lagoda, G. A., Bivalacqua, T. J., Strong, T. D., & Burnett, A. L. (2009). Endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulation in female genital tract structures. The journal of sexual medicine, 6 Suppl 3(S3PROCEEDINGS), 247–253. [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, B. T., Erdman, R. A., & Maltese, W. A. (1991). Carboxyl-terminal isoprenylation of ras-related GTP-binding proteins encoded by rac1, rac2, and ralA. The Journal of biological chemistry, 266(15), 9786–9794.Burridge, K.; Wennerberg, K. Rho and Rac take center stage. *Cell 2004, *116*, 167–179. [CrossRef]

- Burridge, K., & Wennerberg, K. (2004). Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell, 116(2), 167–179. [CrossRef]

- Ramadoss, J., Pastore, M. B., & Magness, R. R. (2013). Endothelial caveolar subcellular domain regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology, 40(11), 753–764. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E., Nagiel, A., Lin, A.J., Golan, D.E. and Michel, T., 2004. Small interfering RNA-mediated down-regulation of caveolin-1 differentially modulates signaling pathways in endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279(39), pp.40659-40669. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E., Kou, R., Lin, A. J., Golan, D. E., & Michel, T. (2002). Subcellular targeting and agonist-induced site-specific phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. The Journal of biological chemistry, 277(42), 39554–39560. [CrossRef]

- Levine, Y. C., Li, G. K., & Michel, T. (2007). Agonist-modulated regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in endothelial cells. Evidence for an AMPK -> Rac1 -> Akt -> endothelial nitric-oxide synthase pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry, 282(28), 20351–20364. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L., Garcia-Barrio, M. T., & Chen, Y. E. (2020). Perivascular Adipose Tissue Regulates Vascular Function by Targeting Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 40(5), 1094–1109. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. H., Chen, S. J., Tsao, C. M., & Wu, C. C. (2014). Perivascular adipose tissue inhibits endothelial function of rat aortas via caveolin-1. PloS one, 9(6), e99947. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., D S Oliveira, S., Zimnicka, A. M., Jiang, Y., Sharma, T., Chen, S., Lazarov, O., Bonini, M. G., Haus, J. M., & Minshall, R. D. (2018). Reciprocal regulation of eNOS and caveolin-1 functions in endothelial cells. Molecular biology of the cell, 29(10), 1190–1202. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Hernando, C., Yu, J., Suárez, Y., Rahner, C., Dávalos, A., Lasunción, M. A., & Sessa, W. C. (2009). Genetic evidence supporting a critical role of endothelial caveolin-1 during the progression of atherosclerosis. Cell metabolism, 10(1), 48–54. [CrossRef]

- Frank, P. G., & Lisanti, M. P. (2004). Caveolin-1 and caveolae in atherosclerosis: differential roles in fatty streak formation and neointimal hyperplasia. Current opinion in lipidology, 15(5), 523–529. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. W., Hnasko, R., Schubert, W., & Lisanti, M. P. (2004). Role of caveolae and caveolins in health and disease. Physiological reviews, 84(4), 1341–1379. [CrossRef]

- Murata, T., Lin, M. I., Huang, Y., Yu, J., Bauer, P. M., Giordano, F. J., & Sessa, W. C. (2007). Reexpression of caveolin-1 in endothelium rescues the vascular, cardiac, and pulmonary defects in global caveolin-1 knockout mice. The Journal of experimental medicine, 204(10), 2373–2382. [CrossRef]

- Keane, J., & Longhi, M. P. (2025). Perivascular Adipose Tissue Niches for Modulating Immune Cell Function. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 45(6), 857–865. [CrossRef]

- Adachi, Y., Ueda, K., & Takimoto, E. (2023). Perivascular adipose tissue in vascular pathologies-a novel therapeutic target for atherosclerotic disease?. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine, 10, 1151717. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. K., Ding, H., Jiang, M., Yin, H., Gollasch, M., & Huang, Y. (2023). Perivascular adipose tissue: Fine-tuner of vascular redox status and inflammation. Redox biology, 62, 102683. [CrossRef]

- Dalton, C. M., Schlegel, C., & Hunter, C. J. (2023). Caveolin-1: A Review of Intracellular Functions, Tissue-Specific Roles, and Epithelial Tight Junction Regulation. Biology, 12(11), 1402. [CrossRef]

- Kassan, M., Vikram, A., Kim, Y. R., Li, Q., Kassan, A., Patel, H. H., Kumar, S., Gabani, M., Liu, J., Jacobs, J. S., & Irani, K. (2017). Sirtuin1 protects endothelial Caveolin-1 expression and preserves endothelial function via suppressing miR-204 and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Scientific reports, 7, 42265. [CrossRef]

- Qin, L., Zhu, N., Ao, B. X., Liu, C., Shi, Y. N., Du, K., Chen, J. X., Zheng, X. L., & Liao, D. F. (2016). Caveolae and Caveolin-1 Integrate Reverse Cholesterol Transport and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. International journal of molecular sciences, 17(3), 429. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Hoang, A., Escher, G., Parton, R. G., Krozowski, Z., & Sviridov, D. (2004). Expression of caveolin-1 enhances cholesterol efflux in hepatic cells. The Journal of biological chemistry, 279(14), 14140–14146. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Feo, J. A., Hellings, W. E., Moll, F. L., De Vries, J. P., van Middelaar, B. J., Algra, A., Sluijter, J., Velema, E., van den Broek, T., Sessa, W. C., De Kleijn, D. P., & Pasterkamp, G. (2008). Caveolin-1 influences vascular protease activity and is a potential stabilizing factor in human atherosclerotic disease. PloS one, 3(7), e2612. [CrossRef]

- Cassuto, J., Dou, H., Czikora, I., Szabo, A., Patel, V. S., Kamath, V., Belin de Chantemele, E., Feher, A., Romero, M. J., & Bagi, Z. (2014). Peroxynitrite disrupts endothelial caveolae leading to eNOS uncoupling and diminished flow-mediated dilation in coronary arterioles of diabetic patients. Diabetes, 63(4), 1381–1393. [CrossRef]

- Janaszak-Jasiecka, A., Płoska, A., Wierońska, J. M., Dobrucki, L. W., & Kalinowski, L. (2023). Endothelial dysfunction due to eNOS uncoupling: molecular mechanisms as potential therapeutic targets. Cellular & molecular biology letters, 28(1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Lobysheva, I., Rath, G., Sekkali, B., Bouzin, C., Feron, O., Gallez, B., Dessy, C., & Balligand, J. L. (2011). Moderate caveolin-1 downregulation prevents NADPH oxidase-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling by angiotensin II in endothelial cells. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 31(9), 2098–2105. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J., Li, X., & Dou, N. (2024). Insulin Resistance Triggers Atherosclerosis: Caveolin 1 Cooperates with PKCzeta to Block Insulin Signaling in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Cardiovascular drugs and therapy, 38(5), 885–893. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Hernando, C., Yu, J., Dávalos, A., Prendergast, J., & Sessa, W. C. (2010). Endothelial-specific overexpression of caveolin-1 accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. The American journal of pathology, 177(2), 998–1003. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Jia, X., Wang, Y., & Zheng, Q. (2025). Caveolin-1-mediated LDL transcytosis across endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis, 402, 119113. [CrossRef]

- Valentini, A., Cardillo, C., Della Morte, D., & Tesauro, M. (2023). The Role of Perivascular Adipose Tissue in the Pathogenesis of Endothelial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Diseases and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines, 11(11), 3006. [CrossRef]

- Zaborska, K. E., Wareing, M., Edwards, G., & Austin, C. (2016). Loss of anti-contractile effect of perivascular adipose tissue in offspring of obese rats. International journal of obesity (2005), 40(8), 1205–1214. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, C. M., Zhang, X., Bandyopadhyay, C., Rotllan, N., Sugiyama, M. G., Aryal, B., Liu, X., He, S., Kraehling, J. R., Ulrich, V., Lin, C. S., Velazquez, H., Lasunción, M. A., Li, G., Suárez, Y., Tellides, G., Swirski, F. K., Lee, W. L., Schwartz, M. A., Sessa, W. C., … Fernández-Hernando, C. (2019). Caveolin-1 Regulates Atherogenesis by Attenuating Low-Density Lipoprotein Transcytosis and Vascular Inflammation Independently of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Activation. Circulation, 140(3), 225–239. [CrossRef]

- Victorio, J. A., Fontes, M. T., Rossoni, L. V., & Davel, A. P. (2016). Different Anti-Contractile Function and Nitric Oxide Production of Thoracic and Abdominal Perivascular Adipose Tissues. Frontiers in physiology, 7, 295. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).