1. Introduction

In the present world, people have become very dependent on mobile phones. Over the past few decades, the number of mobile subscribers has significantly increased. At present, approximately 89.90% percent of the world’s population uses a mobile device [

1]. 5G is the fastest-growing generation, with about 220 million worldwide subscribers in the fourth quarter of 2020, increasing to 300 million in the first quarter of 2021 [

2].

The 3GPP (3rd Generation Partnership Project) developed Authentication & Key Agreement (AKA) protocols of the following 3G and 4G technologies, which have provided mutual authentication between user equipment and the network. The current 5G contains the 5G AKA proposed by 3GPP, which is an enhanced variant of the AKA protocol [

3,

4].

Although the 4G authentication protocol is far improved than previous generations, there remain a number of security vulnerabilities [

4,

5]. Also, it is expected that 5G will not contain the authentication security vulnerabilities or at least have a solution to some of the vulnerabilities of authentication protocols that existed in 4G. Although 5G addresses some of the shortcomings of 4G, it does not ensure the user’s location confidentiality as well as untraceability.

One of the security vulnerabilities of the AKA protocol is that HN doesn’t check the freshness of encrypted identifiers. Also, whenever it generates an authentication challenge and sends it to SN, it does not add any users’ specific information. So, an adversary can take advantage of this and execute a parallel session. In a parallel session, the Serving Network doesn’t know where to respond to the request message. The Serving network can allow wrong responses on the protocol. This incident causes a contrary situation in authentication procedures. Consequently, the attacker gains control over the timings and flow of messages [

5]. Another weakness of the authentication protocol is that the UE does not first check the freshness of the authentication challenge before checking its authenticity. By using this vulnerability, an adversary can record the authentication challenge that the HN sends to the target UE and replay it to all UEs in a specific region. The attack region. The target UE passes the Message Authentication Code (MAC) check since it was created with the correct key, but it fails the next freshness check because the message was replayed and responds with a Sync Failure message, whereas the other UEs all fail the MAC check and respond with MAC Failure messages [

6,

7].

In this paper, we have presented some inherent security vulnerabilities related to the AKA protocol, which have been identified through a review of recent literature, and also provided a modified 5G AKA protocol that will mitigate the exploitation of the identified vulnerabilities.

In a nutshell, the major contributions of the research are as follows.

We explore the authentication weaknesses of the AKA protocol in different generations of mobile communication and study the existing vulnerabilities.

We propose a security-enhanced 5G AKA protocol that will address the security and privacy issues identified earlier.

We provide a formal analysis of the proposed security-enhanced 5G AKA protocol.

2. Background

The 5G mobile telephone system architecture consists of the following 4 main entities. The AKA protocol is executed through the communication between the 4 entities.

UE: The User Equipment (UE) stands for the subscriber’s ME (Mobile Equipment) that is carried by the subscriber. Each subscriber is identified by a unique permanent identifier known as SUPI, which is stored in the USIM processing on the UE [

5,

9,

12].

SEAF: The security anchor function (SEAF) resides within the serving network and provides the authentication functionality. In a roaming scenario, if no HN base station is available in the user’s location, the UE is attached to the SEAF rather than its HN. In this paper, SN and SEAF have been used interchangeably [

5].

AUSF: The Authentication Server Function (AUSF) is an HN function that makes decisions during the authentication process. AUSF manages SEAF requests and communicates with the ARPF [

11].

ARPF: The authentication credential repository and processing function (ARPF) is also a function of HN which provides backend services to AUSF. It stores each UE’s long-term secret key, as well as cryptographic algorithms and authentication vectors for each authentication session.

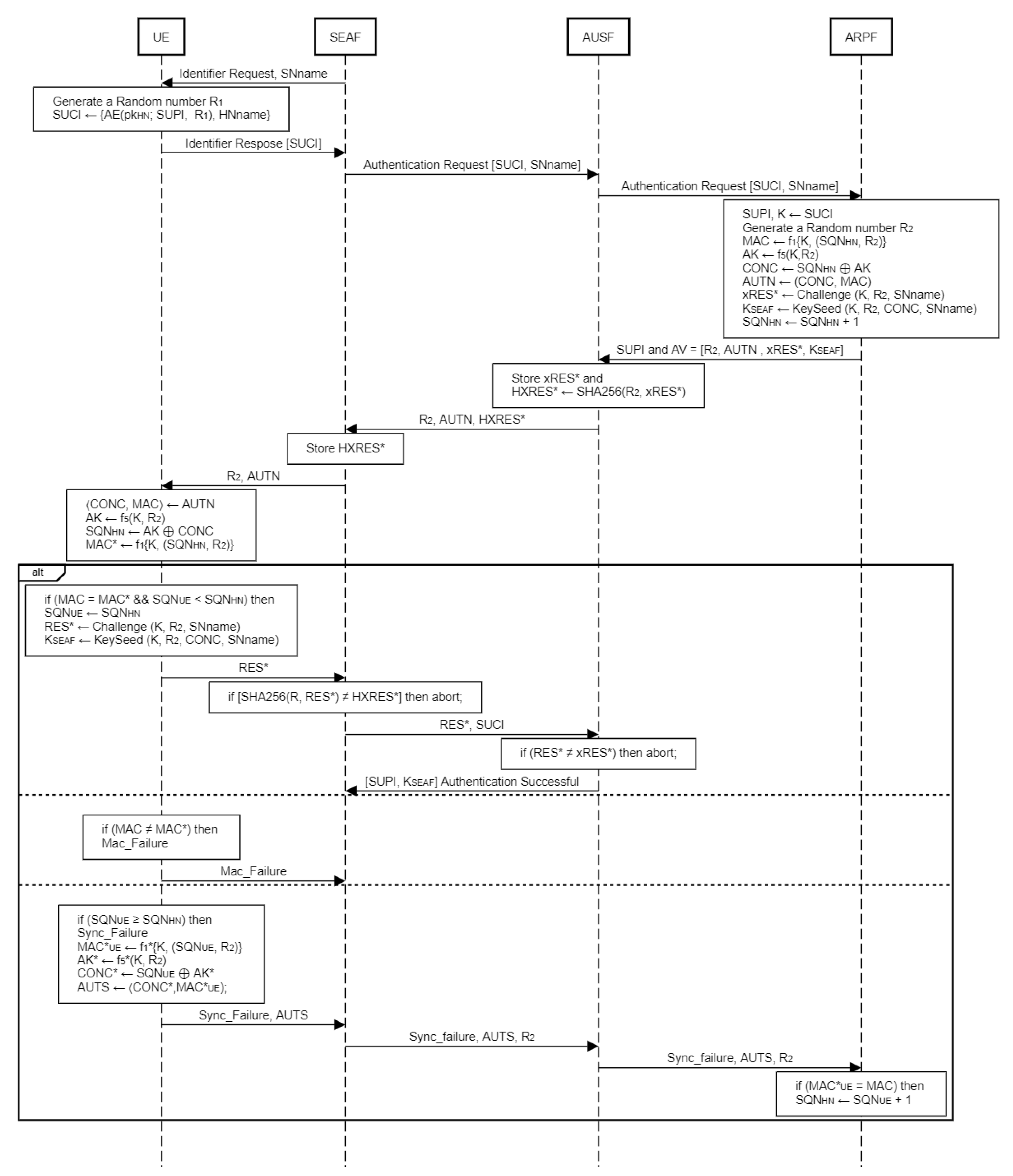

Here we present the description of the standard 5G Authentication and Key Agreement (AKA) protocol:

For user identification, the SN will first want to know the identity of the UE by sending an identity request message to the UE. When UE receives the message, it generates an Identity response message containing SUCI, in which SUPI is encrypted with a Random number R1 and HNname is remains unencrypted.

UE sends the encrypted SUPI and HNname to the SEAF and then SEAF sends it to AUSF together with SNname instead of HNname. Then AUSF forwards the message to ARPF.

When the SUCI and SNname are received, the ARPF’s SIDF function is used to decrypt the encrypted SUPI with HN’s private key and obtain the SUPI after decrypting it. Then ARPF retrieves the long term shared secret key K of the corresponding SUPI and SQNHN, which are both used to generate AV.

The ARPF sends the SUPI and AV of the corresponding SUPI to the AUSF in an “authentication response” message. The AV contains R

2, AUTN, xRES* and K

SEAF. The detailed calculation of AV is shown in

Figure 1.

After receiving SUPI and AV from ARPF, AUSF stores the xRES* and uses the SHA256 function to compute the hash value HXRES* from the received and sends it to SEAF instead of xRES* within AV. When AUSF delivers the AV to SEAF, it simply contains R2, AUTN and HXRES*.

After receiving the Authentication Response message from AUSF, SEAF stores the HXRES* and delivers only R2 and AUTN to UE as the Authentication Request Message.

- 7.

After 2. and the stored long term secret key K of the user which is only known to UE and HN’s ARPF. Using that AK, UE calculates the sequence number of HN. After regenerating the sequence number of HN, MAC* will be regenerated, which is the same procedure in UE as ARPF and compare it to MAC, which is derived from received AUTN.

- 1.

After recalculating SQN

HN and MAC*, the UE will perform two tests: MAC and SQN checks to ensure the authenticity and freshness of the authentication challenge received from the network as an Authentication Request Message. MAC check confirms the authenticity of the challenge, while SQN check verifies the freshness of the authentication request.

Figure 1 depicts in detail the verification of AUTN in UE.

- 1.

a. If both checks succeed, SQN of UE will be updated to HN’s SQN and the UE will send an authentication response RES* to SEAF for further verification. The SEAF then computes the hash value of the RES* using the SHA256 function and compares it to the previously stored HXRES*. If the comparison succeeds, the RES* will be transmitted to AUSF; otherwise, the session will be terminated. In AUSF, the received RES* is compared to the previously saved xRES* from AV, and if this check is successful, AUSF sends the previously stored SUPI and KSEAF to SEAF.

- 1.

b. If the MAC check fails, the UE will send a MAC failure message to SEAF.

- 1.

c. If the MAC check is successful but the SQN check fails, the UE will calculate an AUTS and send it to SEAF along with a Sync failure message for re-synchronization.

Existing Security Threats

Several security vulnerabilities exist in 5G AKA protocol and one of the security vulnerabilities is the Linkability attack. By taking advantage of the linkability attack an adversary can identify in which cell the target user is situated. Linkability attack is present and executable in every generation of mobile communication [

4]. Another weakness in the authentication protocol is that HN does not verify the freshness of encrypted identifiers, which might lead to SUCI replay attacks. Also, for a specific encrypted identifier whenever HN generates an authentication challenge it does not add any users’ specific information. So, an adversary can take advantage of this and execute a parallel session attack [

5].

Now we will describe parallel session attack, linkability attack and SUCI replay attack from the understanding that we have gained by studying recent literatures:

Parallel Session Attack

In a parallel session attack, Attacker records the SUCIV (Victim’s concealed SUPI). From the same home network, the attacker manages an authentic USIM for his own use and obtains its long-term key KA. The attacker then initiates a parallel authentication session with the HN via SEAF by sending his SUCIA (the attacker’s concealed SUPI) and replaying the victim’s recorded SUCIV. Since the HN cannot check the freshness of the SUCI, the HN cannot determine whether or not this SUCI is replayed. So, HN’s ARPF decrypts SUCIV and SUCIA then calculates the AV for both which contains R, AUTN. xRES, KSEAF, SUPI. The ARPF then sends AV to the AUSF, while the AUSF sends AV to the SEAF it contains only R, AUTN, but no user information. In this case, SEAF is unable to determine to which user it should transmit this R, AUTN. So, it can respond to SUCI-Attacker or SUCI-Victim which cause identifier miss binding. If SEAF transmits an attacker’s AV to the victim by mistake, then as we previously mentioned the victim is actually an attacker so the attacker could recalculate the SQNHN, AK and MAC from AUTN by using KA (long-term key of Attacker) and compare them with its own MACUE and SQNUE. After satisfying these conditions of authentication procedure, AUSF will send SUPI-Attacker to the SEAF. As a result, the attacker gains control of the authentication procedures because the home network views the attacker as a victim.

Linkability Attack

In Linkability attack, at first the attacker observes the authentication request message of the target UE containing RAND and AUTN and records this message. Then the adversary using a replay mechanism can broadcast the recorded authentication request message of the target UE to all UEs in a specific region. All the UE in the attack area will receive the replied authentication request message [

6,

7]. After receiving the Authentication Request Message [R, AUTN], UE tries to retrieve MAC

HN, AK and SQN

HN from AUTN and compare them with its own calculated MAC and SQN

UE. After those comparisons UE will send an Authentication Response Message to SN which could be of three types.

Only the target user can pass the MAC check because using the same long term secret key is used to generate AUTN. However, since the message was replayed, it fails the next freshness check. So it will give a Sync_failure message and whereas the other users all fail the MAC check and respond with MAC Failure messages [

6,

7]. As the attacker can differentiate the two kinds of failure messages, the attacker will be able to determine that the target user is present in a specific area if the received message is a synchronization failure message or UE is not in a specific area if all the received messages are MAC failures [

6,

7,

10].

SUCI Replay Attack

In this attack scenario, the attacker monitors in on all the transmission between the target UE and SN. The attacker records the SUCI sent by the target UE to the SN and replays it to the network. According to the standard 5G AKA protocol, since the HN cannot check the freshness of the received SUCI, it cannot determine whether the received SUCI is replayed or not. Due to this vulnerability, HN generates an AV for that SUCI and transmits it to UE. Since HN calculated the AV appropriately for that UE, the AV will be verified by UE without any failure notice. Other UEs will send a MAC failure message to the SN since the HN calculates their MACs using the k shared with the target UE. By distinguishing response messages, the attacker locates the target user [

6].

3. Related Works

Many researchers have done significant work and contribution in the field by identifying security vulnerabilities, security threats, providing solutions, and executing formal analysis of the AKA protocol.

Cremers et al. in [

5] performed formal analysis of 5G AKA protocol and ensured already discovered security issues. They described how security issues can be exploited by an Attacker to execute a parallel session attack by impersonating as the target user. They suggested explicit identity binding and tighter session binding as possible defenses against the attack and utilized the TAMARIN Prover tool to demonstrate their validity. Haibat et al. in [Identity Confidentiality in 5G Mobile Telephony Systems] conducted a study on the subscribers identity confidentiality of 5G and stated the importance of quantum secure cryptographic schemes. In future quantum computing will be far advanced and the cryptographic scheme used in 5G specification such as ECIES scheme which is used to ensure the privacy of subscriber identifiers is vulnerable to quantum algorithms. They identified security loopholes in the ECIES based subscriber identifier protection scheme such as it is susceptible to chosen SUPI attack, replay attack, bidding down attack and quantum insecure which is already mentioned. They proposed a quantum secure scheme which is a symmetric alternative to the ECIES mechanism.

Xinxin HU et al. in [

10] described an attack called location sniffing attack which is actually linkability attack and they identified the underlying AKA security vulnerabilities that were exploited to execute the attack. They proposed a countermeasure to a novel linkability attack of 5G authentication by redesigning the authentication response message and encrypting it using the 5G network’s current PKI method. For 5G Yuchen Wang et al. in [

6] analyzed the underlying cause of known 5G AKA linkability attacks. They provided a privacy-preserving solution for the AKA protocol that prevents linkability attacks by encrypting the authentication challenge delivered from HN with a shared key using ECIES-based technique.

In our research we have also identified some security and privacy vulnerabilities of the 5G AKA protocol and proposed a security enhanced 5G AKA protocol by incorporating Cremers et al. [

5] idea of session binding with our own unique idea to prevent not only parallel session attack but also linkability attack and SUCI replay attack.

4. Proposed Security Enhanced 5G AKA Protocol

In our proposed protocol we have modified the 5G AKA protocol such that it can prevent the security vulnerabilities that allow parallel session attack, linkability attack and SUCI replay attack. In a parallel session scenario, the Serving network gets confused about which UE to respond to the request message and allows wrong responses to get attached to wrong UE [

5]. The confusion arises due to the fact that HN doesn’t add any user specific identifier when it generates an authentication challenge for an encrypted subscriber identifier and also HN doesn’t check the freshness of encrypted subscriber Identifiers [

5]. For the linkability attack issue, an attacker uses a replay mechanism to replay the recorded authentication challenge to all UEs in the attack region. The protocol’s flaw is that after deriving the sequence number from the authentication challenge, the UE’s USIM does not check whether the sequence number has been used before comparing MAC (Message Authentication Code) [

6,

7].

To solve the parallel session issue, we have implemented the idea of one-to-one mapping of 5G AKA session and inner function SEAF—AUSF, AUSF- ARPF from Cremers et al. [

5] by using sessions id also have contributed with our idea of HN ensuring the freshness of SUCI. In addition, for linkability attack issues, we implemented our idea to first check the freshness of the Authentication Request Message before checking the MAC address.

In the initialization phase, after getting an Identifier request from SN, UE calculates SUCI and sends it to SEAF as an identifier response message. But according to the 5G standard protocol, HN does not have any replay protection mechanism [

8,

9]. To address this weakness of HN, in our proposed protocol we used 48-bit SQN

UE instead of a random number and delivered it as an identifier response message (SUCI).

After receiving SUCI HN’s ARPF will derive SUPI from SUCI then compare the SQN with its previously used SQN for a specific SUPI which was stored when the UE was previously verified. To defeat replay attacks, SQNUE should be always greater than previously stored SQN of UE (like; SQNUE > SQNUE-1 ). So in our proposed solution if the SQNUE is less than SQNUE-1 authentication session will be aborted. ARPF will calculate an AV for that SUPI and send it to AUSF for further authentication if and only if SQNUE > SQNUE-1. For the first time authentication, the likely value of SQNUE-1 will be in a certain range determined by the service provider which is only known by the HN’s ARPF.

After a single authentication is completed, the previously stored sequence number SQNUE-1 should be updated as SQNUE.

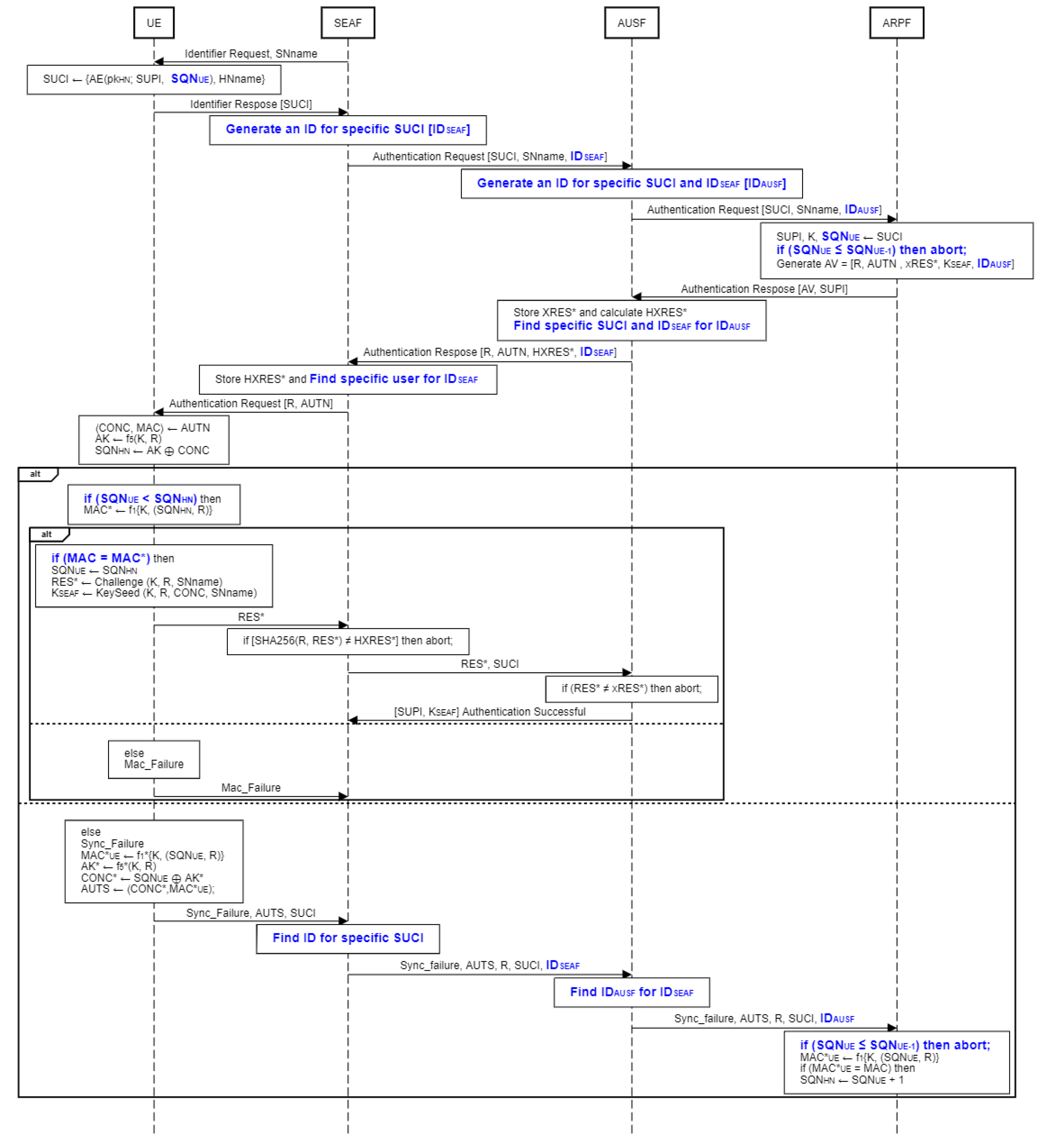

Figure 2.

Proposed Security Enhanced 5G AKA Protocol (simplified version).

Figure 2.

Proposed Security Enhanced 5G AKA Protocol (simplified version).

When multiple sessions occur at a time the serving network gets confused about which user to respond to, to solve this parallel session issue in our proposed protocol we have incorporated the use of session id for session binding. In the proposed protocol after getting SUCI from UE, SEAF generates a specific IDSEAF for each SUCI. After that SEAF will transmit the SUCI along with IDSEAF to AUSF and AUSF will also generate an IDAUSF for each SUCI and transmit it along with IDAUSF to ARPF. So whenever ARPF generates an AV for a session, it includes IDAUSF and sends it to AUSF. Then AUSF will search IDSEAF using that IDAUSF which it receives from ARPF along with AV. After that AUSF will transmit R, AUTN and HXRES* with the founded IDSEAF. With the support of IDSEAF, SEAF will now be able to identify the user to whom R, AUTN needs to transfer. This way SEAF will not be confused about users because in 5G standard protocol SEAF has no specific information.

According to standard 5G AKA protocol, When UE receives R and AUTN as Authentication Request Message from SEAF, it first checks its authenticity rather than freshness. As a result, attackers can locate the target user by replaying the stored authentication request message. To solve this issue in our proposed protocol UE will first check the freshness of the Authentication Request Message. To solve this issue we made some modifications in which UE will first check the freshness of the Authentication Request Message. It checks if SQNHN is greater than SQNUE or not. If SQNHN is not greater than SQNUE, then it sends SEAF a Sync_failure message for resynchronization. In this way even if the attacker replays the authentication request message[R, AUTN] to all UE in a region, he/she will receive a sync_failure message from all UE and will not be able to differentiate between them. As a result, target UE will be untraceable and user’s location privacy will be protected from the attacker.

The above-mentioned modifications to our proposed protocol will prevent the parallel session attack, linkability attack, and SUCI replay attack, which the standard 5G AKA protocol cannot prevent.

The operations in each entity participating in the protocol are described in the subsequent sections in detail.

4.1. Operation and Modification of UE

SUCI = {AE( pkHN; SUPI, SQNUE), HNname }

Here SQN is a 48-bit UE/SUPI specific value. This public key of the HN is given to the UE during the USIM registration [19]. UE sends the encrypted SUPI and HNname to the SEAF.

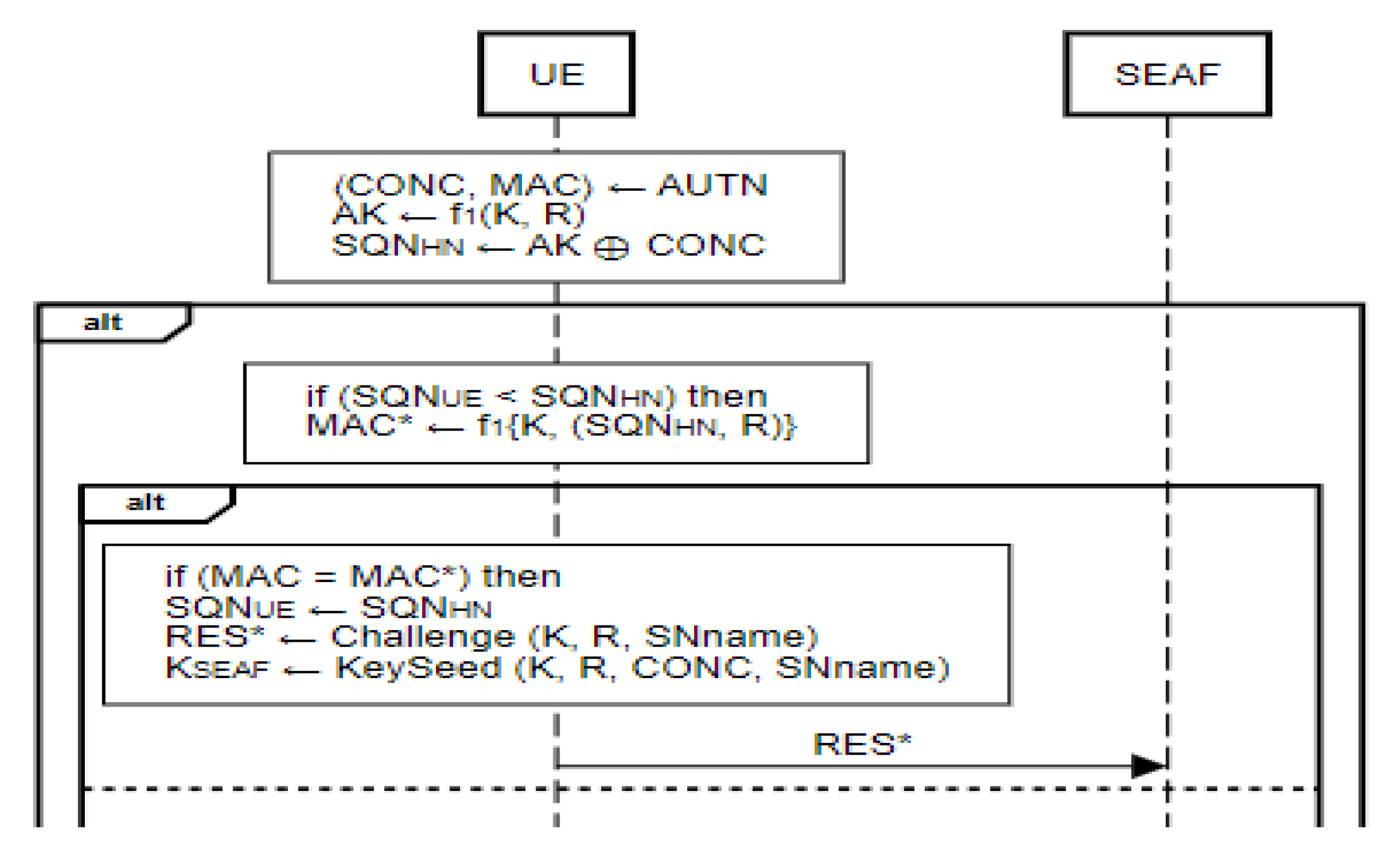

(CONC, MAC) ← AUTN

Figure 3.

UE sends RES* to SEAF.

Figure 3.

UE sends RES* to SEAF.

The anonymity key AK is computed using received random number R and derived long term secret key K which is only known to UE and HN where,

AK = f1 (K, R)

At first CONC and MAC are derived from received AUTN and an anonymity key AK is computed using received random number R and the stored long-term secret key K of the user which is only known to UE and HN’s ARPF. After that SQNHN will be recovered by UE using the regenerated AK and CONC where,

SQNHN = (AK⊕ CONC)

UE compares the SQNHN with its own SQNUE to check the freshness of the Authentication Request Message. This comparison determines whether SQNHN is greater than SQNUE.

If SQNHN > SQNUE, MAC* will be regenerated using SQNHN, K, and R, and then compared to MAC, which is derived from received AUTN where,

MAC* = f1 (K, SQNHN || R2)

SQNUE ← SQNHN

RES* = Challenge (K, R, SNname)

KSEAF = KeySeed (K, R, CONC, SNname).

- 2.

If MAC* ≠ MAC, then the UE sends a Mac_failure message to SEAF to terminate the authentication procedure.

B. If SQNHN ≤ SQNUE, it recalculates MAC*UE, AK, and CONC*, which are all utilized to generate AUTS. In AUTS, MAC*UE and CONC* are calculated using SQNUE rather than SQNHN.

4.2. Operation and Modification of SEAF

When SEAF obtains the identity response message containing SUCI from the UE, SEAF will generate a unique 128-bit random number for that specific SUCI as a session id [IDSEAF].

After receiving the R, AUTN, and IDSEAF from AUSF, SEAF uses the received IDSEAF to locate the specific UE and deliver the R and AUTN.

SEAF receives RES* from UE and computes the hash value of RES* using SHA256 and compares it to HXRES* which is received during AV transmission. If both are found to be equal, RES* and its matching SUCI are sent to AUSF.

4.3. Operation and Modification of AUSF

After getting the IDSEAF, SUCI, and SNname from SEAF, AUSF stores the IDSEAF and produces a 128-bit random number [IDAUSF].

After receiving AV from ARPF, which consists of R, AUTN, xRES*, KSEAF, SUPI, and IDAUSF, AUSF stores the xRES* and uses the SHA256 function to compute the hash of the response HXRES* from the received xRES*. Then AUSF finds the IDSEAF for the received IDAUSF and sends it in place of IDAUSF. When AUSF delivers the AV to SEAF, it simply contains R and AUTN.

If the hash of RES* and HXRES* check is passed the AUSF receives RES* and SUCI from SEAF. Then compares RES* with the recorded xRES*. If the comparison succeeds, the authentication is successful, and AUSF will send the stored SUPI and KSEAF to SEAF; otherwise, the session will be terminated.

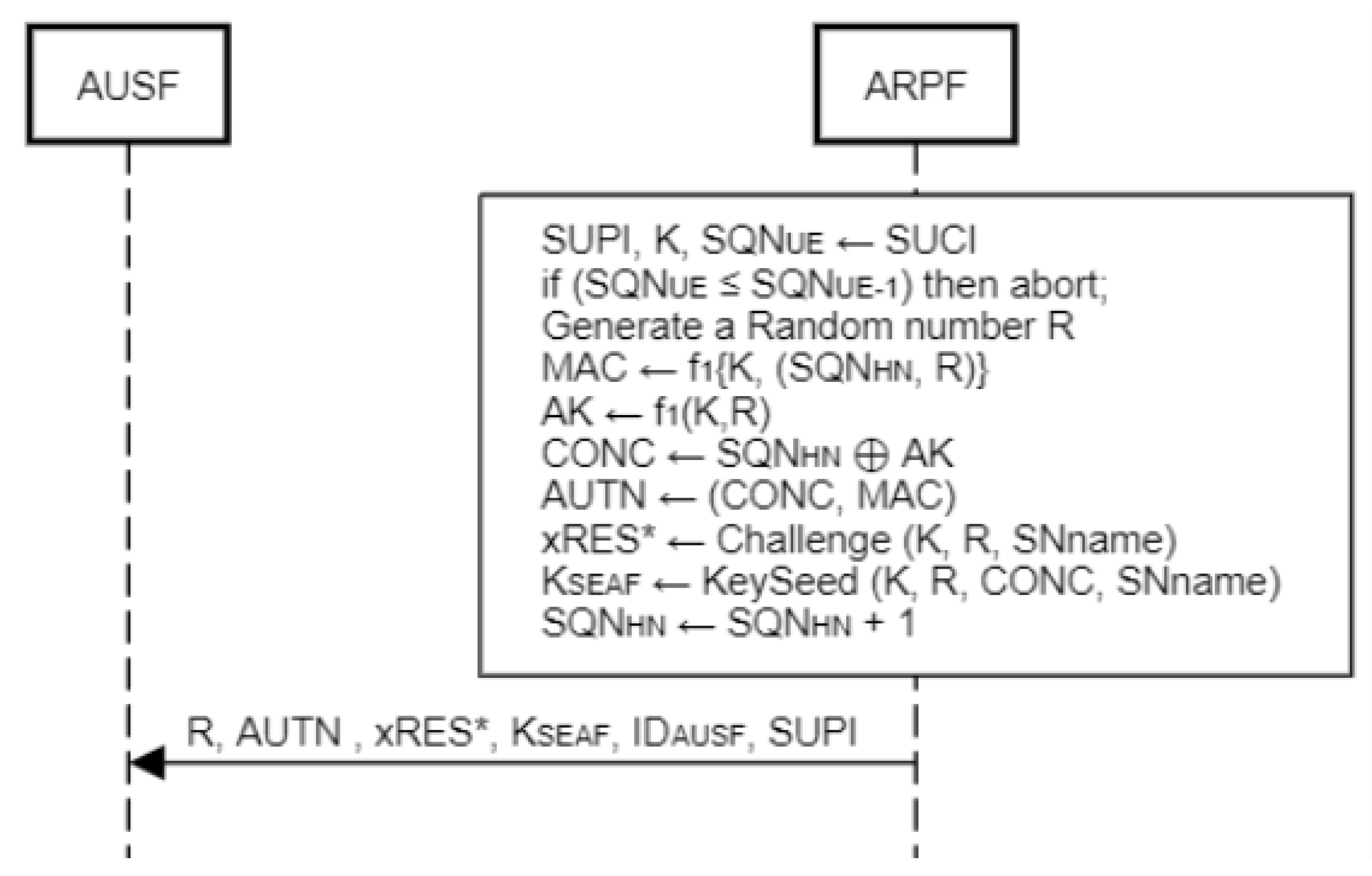

4.4. Operation and Modification of ARPF

SUPI, SQNUE = SIDF(SUCI) prk HN

For the first time authentication, the likely value of SQNUE-1 will be in a certain range determined by HN which is only known by the ARPF and it must be less than SQNUE. If SQNUE ≤ SQNUE-1 then the authentication session will be aborted or otherwise HN will calculate AV. Then ARPF retrieves the SUPI corresponding long term shared secret key K which is 128 bit in length and SQNHN which is 48 bit in length and both are used to generate AV. The standard protocol defines seven cryptographic functions: f1, f1*, f2, f3, f4, f5, and f5*: f1, f1* and f2 are message authentication functions, whereas f3, f4, f5, and f5* are key derivation functions. These are one-way keyed functions that should behave almost exactly like independent random functions.

AV generation consists of following steps:

A 128-bit random number R is generated.

A 64-bit MAC is calculated as MAC = f1 (K, SQN || R).

A n-bit xRES* is calculated where n is a multiple of 8 and in the range between 32-128 as xRES* = Challenge (K, R, SNname), where Challenge () is a key derivation function.

An anchor key KSEAF is calculated by ARPF as KeySeed (K, R, CONC, SN name), where KeySeed () is a complex key derivation function.

The 128-bit ciphering key CK is computed by the ARPF CK = f5 (K, R).

The 128-bit integrity key IK is computed by the ARPF as IK = f4 (K,R).

The 48-bit anonymity key AK is computed by the ARPF as AK = f5(K, R).

A 48-bit CONC is calculated as CONC = (SQNHN ⊕ AK).

The 128-bit authentication token AUTN is generated by ARPF as AUTN = (SQNHN ⊕ AK) || MAC, where || signifies concatenation and ⊕ denotes bitwise exclusive-or.

The ARPF forwards the 5G AV = [R, AUTN, xRES*, KSEAF, IDAUSF] and SUPI in an “authenticate response” message to the AUSF.

Figure 5.

ARPF sends AV to AUSF.

Figure 5.

ARPF sends AV to AUSF.

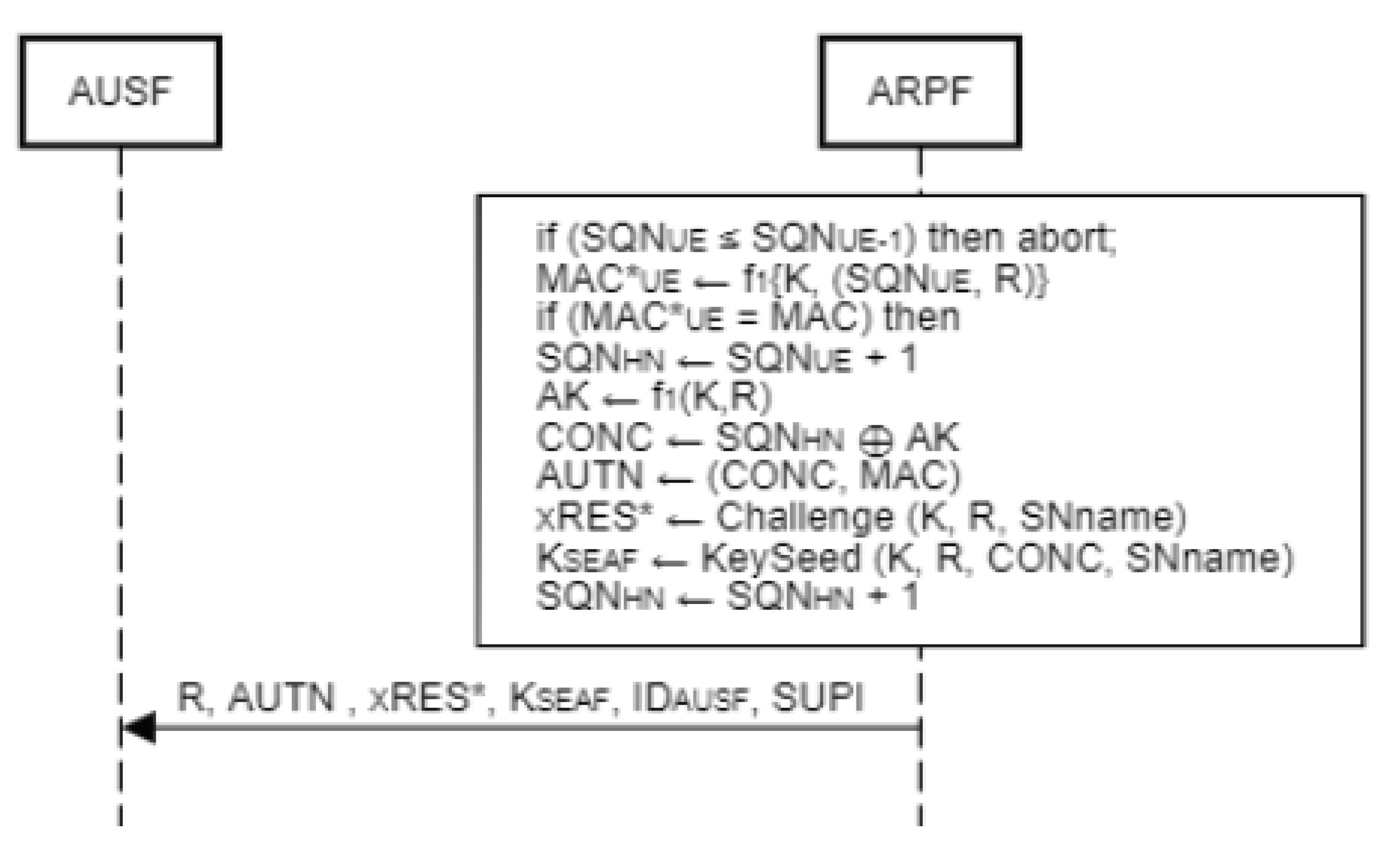

When Sync_failure occurs in the authentication procedure, ARPF needs to adjust its SQNHN and recalculate the AUTN. In this procedure, ARPF first compares the received SQNUE with previously stored SQNUE-1. If condition is fulfilled, then MAC*UE will be generated using the received SQNUE with the help of k and R using the message authentication function f1. After that, if the comparison of MAC*UE and MAC holds, the sequence number of HN will be updated as SQNHN = SQNUE + 1 and the rest of the computation will be the same as before applying the updated SQNHN.

5. Analysis of the Proposed Protocol

We have incorporated all our security modifications in the existing 5G AKA protocol without changing the basic structure of the protocol. According to the 5G standard protocol, HN does not have any replay protection mechanism [

8,

9]. But our proposed protocol provides a replay protection mechanism for HN. To solve this weakness of HN, we have used SQN

UE instead of random number in SUPI encryption, which is a new addition. Because random numbers cannot ensure the uniqueness of the received SUCI. But use of sequence numbers can ensure the difference between received SUCI in two different AKA sessions. This way, it can detect SUCI replay attacks and partially solve parallel session attacks.

Another vulnerability of the standard 5G AKA protocol is whenever SEAF gets AV from AUSF it does not contain any user specific information from which SEAF could decide which AV should be sent to which user. Parallel session attack is the consequence of above-mentioned vulnerabilities of the standard AKA protocol (detailed description of parallel session attack is provided in section 2)

. To solve the parallel session issue, we have implemented the idea of one to one mapping of 5G AKA session and inner function SEAF—AUSF, AUSF—ARPF from Cremers et al. [

5] by using session id also the above-mentioned solution to ensure the freshness of SUCI by using SQN

UE to encrypt SUPI. The use of SQN

UE in SUPI encryption is also able to prevent SUCI replay attacks (detailed description of SUCI replay attack is provided in section 2).

Another vulnerability in UE of the standard 5G AKA protocol is that at first UE does not check the freshness of AV which is received from SEAF. An attacker can take advantage of this vulnerability and execute a linkability attack (detailed description of linkability attack is provided in section 2). To solve this issue in our proposed protocol we first check the freshness of the AV by doing the comparison between SQNHN and SQNUE of UE before MAC comparison. In this way even if the attacker replays the authentication request message [R, AUTN] to all UE in a region, he/she will receive a sync_failure message from all UE and will not be able to differentiate between them. As a result, target UE will be untraceable and user’s location privacy will be protected from the attacker.

As our proposed protocol is compatible with the standard 5G AKA protocol, it can be easily deployed.

Figure 6.

Re-synchronization in ARPF.

Figure 6.

Re-synchronization in ARPF.

6. Conclusions

In our research, we have proposed a security-enhanced AKA protocol by modifying the existing AKA protocol, which is also compatible with the standardized 5G AKA protocol. We have identified the privacy and security vulnerabilities of the standard 5G AKA protocol and proposed a security-enhanced AKA protocol that will prevent attacks that are executable by exploiting the identified vulnerabilities. Furthermore, we have described how our proposed protocol will prevent those vulnerabilities from being exploited. We have performed a formal verification of the proposed protocol to validate the security goals that the modified protocol is designed to fulfill. The proposed 5G AKA protocol will be able to provide subscribers with location confidentiality and untraceability, which was not feasible with the existing 5G AKA protocol.

Although this research only contributes to the context of authentication of 5G AKA, there is significant scope for improvement in the overall development of 5G. There is much research needed in the field of improving the overall performance of the 5G network as in the near future, when 5G is deployed, it will be most used among the telecommunication systems. Furthermore, more research is needed to secure the privacy and security of actual data transmitted over the 5G network, which is now unavailable. Also, there is immense scope for research on providing efficient solutions for unprotected network services transmitted before the authentication process.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mohammad Shafiul Alam Khan., Suraiya Akter Sathi., and Nashrah Hasan. ; methodology, Suraiya Akter Sathi, Nashrah Hasan.; software, Suraiya Akter Sathi.; validation, Mohammad Shafiul Alam Khan.; formal analysis, Suraiya Akter Sathi, Nashrah Hasan and Mohammad Shafiul Alam Khan.; investigation, Suraiya Akter Sathi, Nashrah Hasan and Abdullah Al Mamun.; resources, Mohammad Shafiul Alam Khan.; writing—original draft preparation, Nashrah Hasan and Suraiya Akter Sathi.; writing—review and editing, Nashrah Hasan, Suraiya Akter Sathi, and Mohammad Shafiul Alam Khan ; visualization, Suraiya Akter Sathi. Nashrah Hasan, Abdullah Al Mamun and MD Salim Sadman Ifti; supervision, Mohammad Shafiul Alam Khan.; project administration, Mohammad Shafiul Alam Khan.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AK |

Anonymity key |

| AMF |

Authentication management field |

| AUTN |

Authentication token |

| AUTS |

Authentication token in SQN re-synchronization |

| CK |

3GPP cipher key |

| EK |

Encryption key in the Modifiable multiple IMSIs scheme |

| f1 |

3GPP network authentication function |

| f1* |

3GPP re-synchronization message authentication function |

| f2 |

3GPP user authentication function |

| f3 |

3GPP cipher key derivation function |

| f4 |

3GPP integrity key derivation function |

| f5 |

3GPP anonymity key derivation function for normal operation |

| f5* |

3GPP anonymity key derivation function for re-synchronization |

| IK |

3GPP integrity key |

| KA

|

Attacker’s long-term key |

| SUCIV

|

Victims concealed SUPI |

| SUCIA

|

Attacker concealed SUPI |

| KASME

|

Local master key in EPS |

| KSEAF

|

Security anchor function key |

| K Long |

term shared secret key |

| HXRES* |

Hash response |

| MAC |

Message authentication code |

| MAC* |

Regenerate message authentication code |

| SQNHN

|

Sequence number of home network |

| SQNUE

|

Sequence number of user equipment |

| SQNUE-1

|

Previously stored number of user equipment |

| R |

Random number |

| MACUE

|

User equipment message authentication code |

| MACHN

|

Home network authentication code |

| pkHN

|

Home network public key |

| SNname |

Serving network name |

| AE |

Asymmetric encryption |

| IDSEAF

|

ID of security anchor function |

| IDAUSF

|

ID of authentication server function |

| HNname |

Home network name |

| RAND |

Random challenge |

| RES |

Authentication response |

| xRES* |

Expected response |

| RES* |

Generated response |

| SQN |

Sequence number |

| XMAC |

Expected MAC |

| XOR |

Boolean exclusive-OR operation |

| LTE |

Long Term Evolution |

| 2G |

Second Generation |

| 3G |

Third Generation |

| 4G |

Fourth Generation |

| 5G |

Fifth Generation |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| 3GPP |

Third Generation Partnership Project |

| AKA |

Authentication and Key Agreement |

| IMSI |

International Mobile Subscriber Identity |

| GUTI |

Globally Unique Temporary User Equipment Identity |

| UE |

User Equipment |

| HN |

Home Network |

| MAC |

Message Authentication Code |

| AMA |

Activity Monitoring Attack |

| LCA |

Location Confidentiality Attack |

| SUCI |

Subscriber Concealed Identifier |

| SUPI |

Subscriber Permanent Identifier |

| SEAF |

Security Anchor Function |

| AUSF |

Authentication Server Function |

| ARPF |

Authentication Credential Repository and Processing Function |

| UMTS |

Universal Mobile Telecommunication System |

| IP |

Internet Protocol |

| RAN |

Radio Access Network |

| GSM |

Global System for Mobile Communications |

| UTRAN |

Universal Terrestrial Radio Access Network |

| GERAN |

GSM Edge Radio Access Network |

| BTS |

Base Transceiver Station |

| RNC |

Radio Network Controller |

| ME |

Mobile Equipment |

| MSC |

Mobile Switching center |

| VLR |

Visitor Location Register |

| HLR |

Home Location Register |

| GMSC |

Getaway Mobile Switching Center |

| GPRS |

General Packet Radio Service |

| SGSN |

Serving GPRS Support Node |

| GGSM |

Getaway GPRS Support Node |

| MNO |

Mobile Network Operator |

| EPS |

Evolved Packet System |

| EUTRAN |

Evolved Universal Terrestrial Radio Access Network |

| eNB |

Evolved Node |

| gNB |

Next Generation Node B |

| MME |

Mobility Management Entity |

| S-GW |

Serving Getaway |

| PDN |

Public Data Network |

| HSS |

Home Subscriber Server |

| AuC |

Authentication Center |

| USIM |

Universal Subscriber Identity Module |

| P-TMSI |

Packet Temporary Mobile Subscriber Identity |

| TMSI |

Temporary Mobile Subscriber Identity |

| LAI |

Location Area Identity |

| MCC |

Mobile Country Code |

| MNC |

Mobile Network Code |

| MSIN |

Mobile Subscriber Identification Number |

| ECIES |

Elliptic Curve Integrated Encryption Scheme |

| AV |

Authentication Vector |

| SIDF |

Subscription Identifier De-concealing function |

| HPLMN |

Home Public Land Mobile Network |

| VPLMN |

Visited Public Land Mobile Network |

| AMF |

Access and Mobility Management Function |

| NAS |

Non-Access Stratum |

| RRC |

Radio Resource Control |

| SUPA |

Symmetric Updatable Private Authentication |

| PPKA |

Privacy Preserving Key Agreement |

| UICC |

Universal Integrated Circuit Curve |

| TPM |

Trusted Platform Module |

References

- Turner, A. How Many People Have Smartphones Worldwide (Oct 2021). Bank My Cell. 2021. Available online: https://www.bankmycell.com/blog/how-many-phones-are-in-the-world (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- 5G Americas. Global—5G Americas

. 2021. Available online: https://www.5gamericas.org/resources/charts-statistics/global/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Khan, Mohammed Shafiul Alam. Improving Security and Privacy in Current Mobile Systems. Ph.D. dissertation, Information Security Group, Royal Holloway, Univ., London, United Kingdom, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Haibat; Martin, Keith M. On the Efficacy of New Privacy Attacks against 5G AKA. In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications, ICETE 2019—; Prague, Czech Republic, Obaidat, Mohammad S., Samarati, Pierangela, Eds.; SciTePress, 26-28 July 2019; Volume 2, pp. pages 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Cremers, C.; Dehnel-Wild, M. Component-based formal analysis of 5G-aka: Channel assumptions and session confusion. Proceedings 2019 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Y. Privacy-Preserving and Standard-Compatible AKA Protocol for 5G. 30th {USENIX} Security Symposium ({USENIX} Security 21, Aug. 21AD.

- Basin, D.; Dreier, J.; Hirschi, L.; Radomirovic, S.; Sasse, R.; Stettler, V. A formal analysis of 5G authentication. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pari, S.N.; Azhagu Vasanth, R.; Amuthini, M.; Balaji, M. Randomized 5G AKA Protocol Ensembling Security in Fast Forward Mobile Device. 2019 11th International Conference on Advanced Computing (ICoAC), 2019; pp. 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Haibat. Security and Privacy in Emerging Communication Standards. In Information Security Group; Royal Holloway Univ.: London,United Kingdom, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- HU, X.; LIU, C.; LIU, S.; LI, J.; CHENG, X. “A Vulnerability in 5G Authentication Protocols and Its Countermeasure”. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems 2020, vol. 103(no. 8), 1806–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeken, A. “Symmetric key based 5G AKA authentication protocol satisfying anonymity and unlinkability”. Computer Networks 2020, vol. 181, 107424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeken, A.; Liyanage, M.; Kumar, P.; Murphy, J. “Novel 5G Authentication Protocol to Improve the Resistance Against Active Attacks and Malicious Serving Networks”. IEEE Access 2019, vol. 7, 64040–64052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).