Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

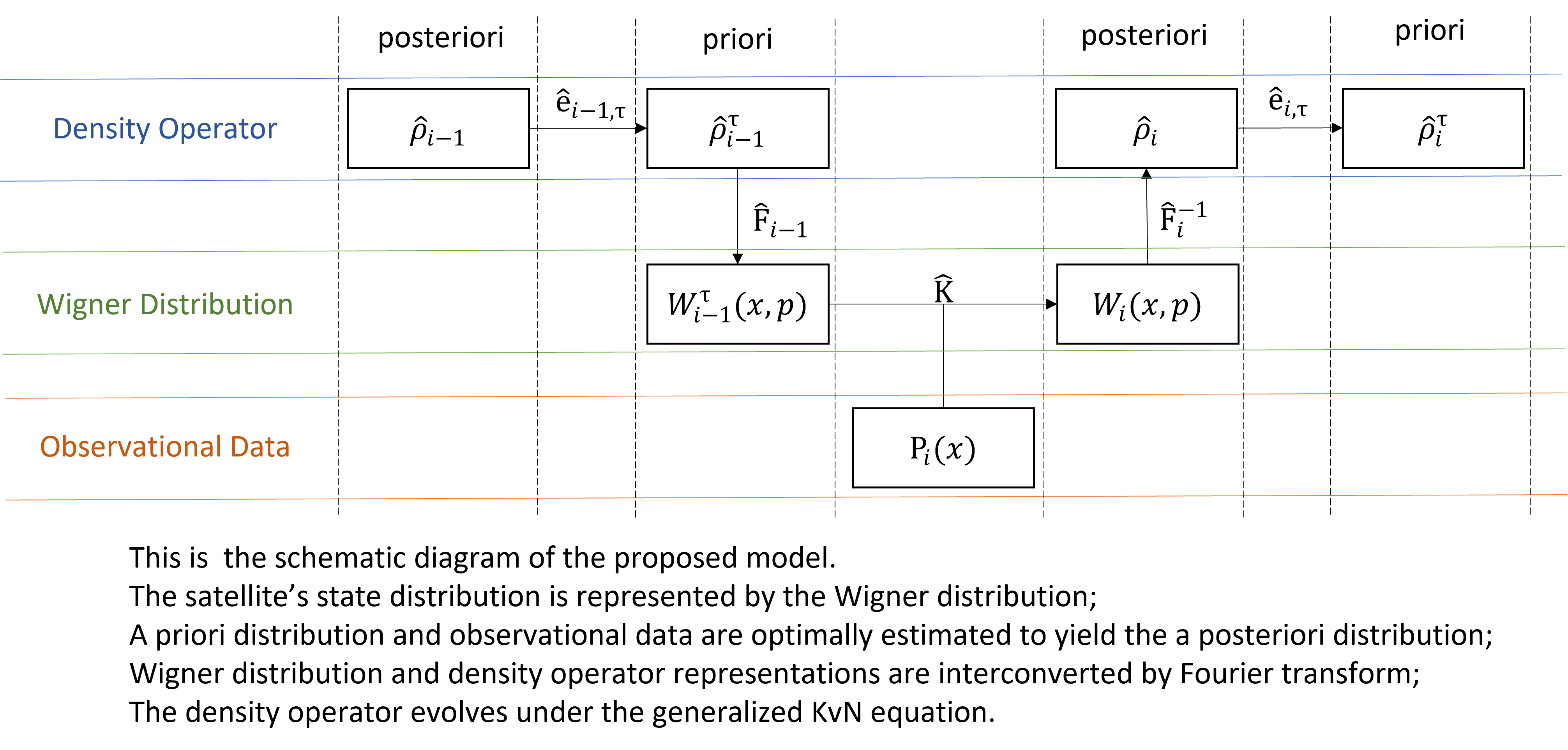

2. Wigner-Based Filtering Framework: Theoretical Foundation

2.1. The Wigner Quasi-Probability Distribution

2.2. The Koopman-von Neumann Formalism

2.3. The Operator Dynamic Model and Generalised KvN Equation

2.4. Evolution for the Wigner Quasi-Probability Distribution

3. Physical Realisation for Gravitational Orbit Dynamics

3.1. Wigner Distribution for Orbital States

3.2. Generalised KvN Evolution under Gravitational Forces

3.3. Flatering Procedure

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experimental Design and Data Generation

4.1.1. Orbit-Parameter Combinations and Simulation Setup

4.1.2. Perturbation Modeling and Error-Source Characterization

- Self-consistent run: only two-body plus J2 perturbation, identical to the force model used in the estimator.

- Biased run: additionally includes solar-radiation pressure and atmospheric drag to assess performance under small systematic errors.

4.1.3. Construction and Grouping Strategy of Observation Data

- (1)

- Clean (no-bias set): contains only machine-precision truncation errors; serves as the theoretical lower bound for filter consistency checks.

- (2)

- SysBias (small-bias set): adds un-modelled atmospheric drag and solar-radiation pressure (Table 2) to the true trajectory, yielding long-term drift at the level of ; used to test robustness under mild model mismatch.

- (3)

- ObsNoise (random-error set): further superimposes zero-mean Gaussian white noise on the SysBias truth, with standard deviations taken from current optical and laser ranging accuracies (radial , along/cross ); dominant in short-term scatter and used to evaluate the benefit of improving observation precision versus refining dynamical models.

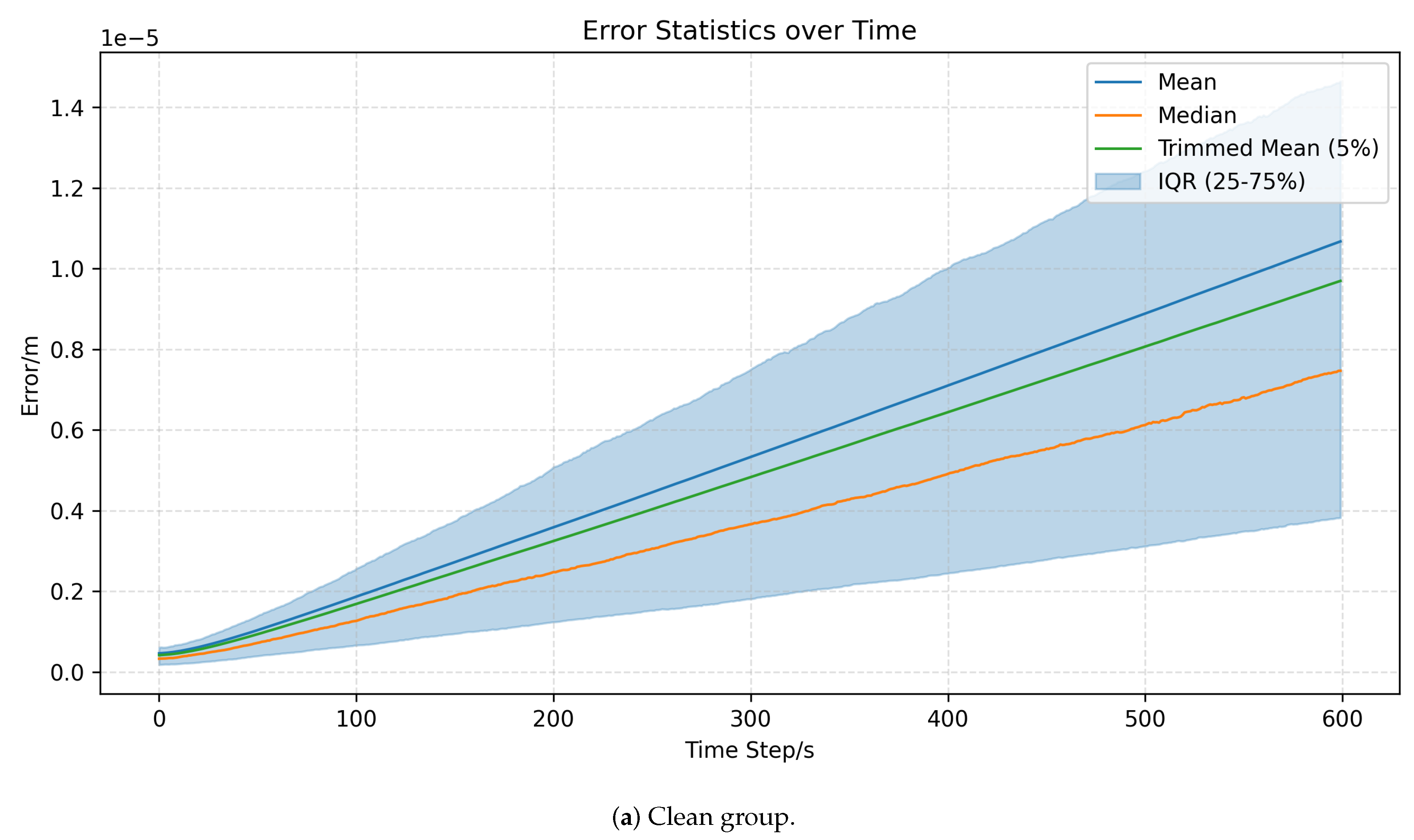

4.2. Statistical Analysis of Prediction Errors

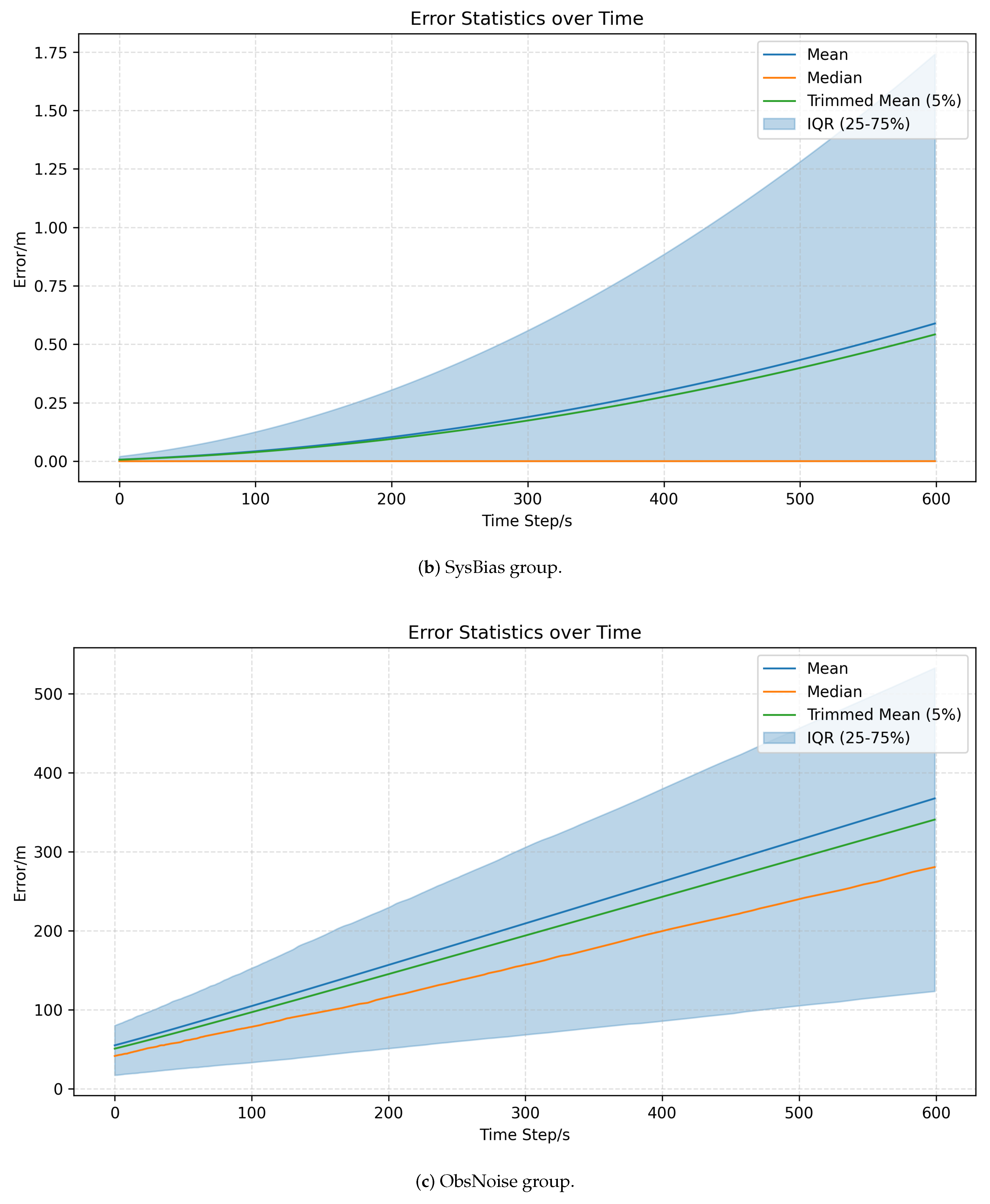

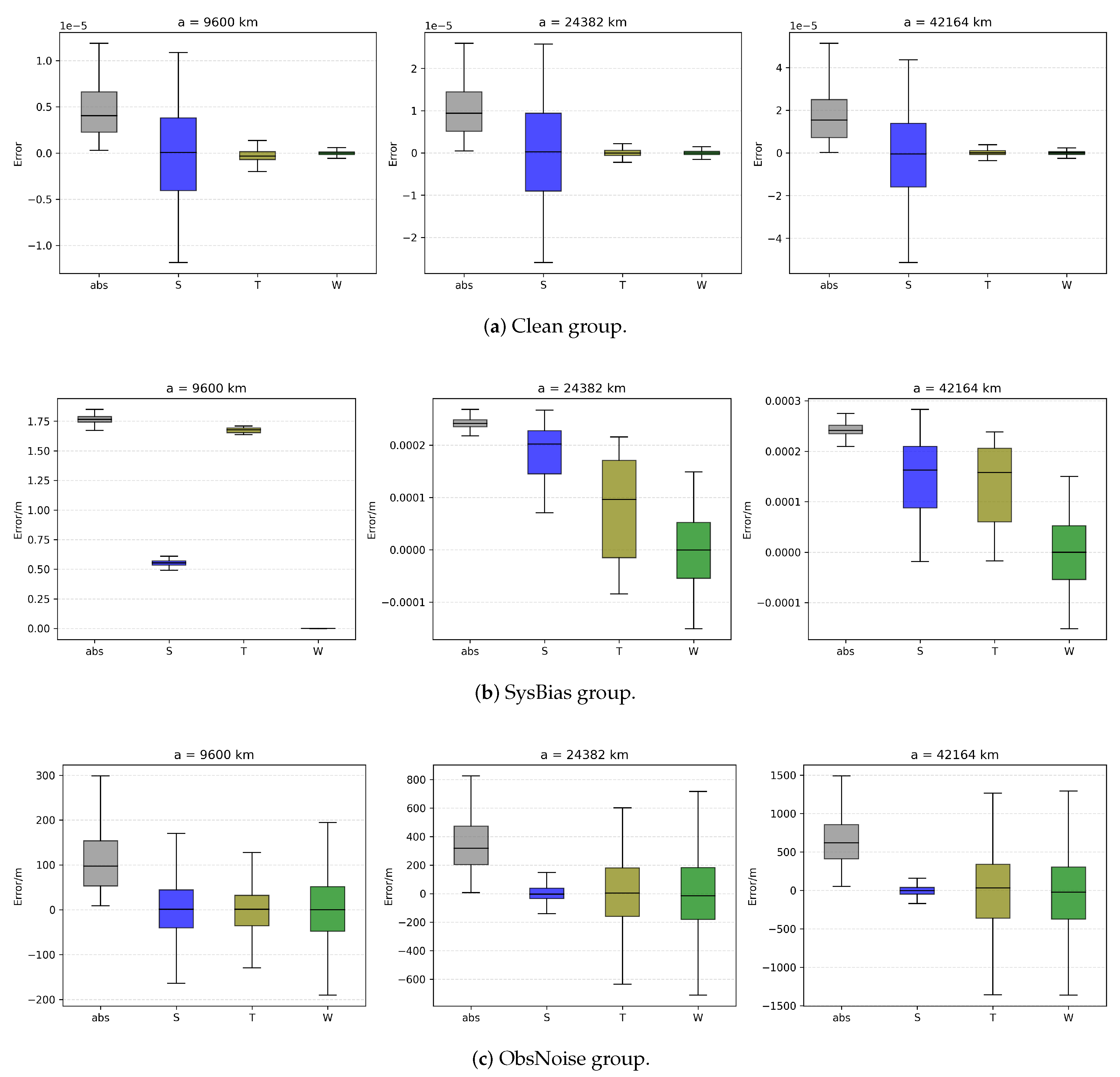

4.2.1. Ten-Minute Prediction-Error Distribution

4.2.2. Comparison Among Clean, SysBias and ObsNoise Groups

- Clean: errors grow linearly and slowly with time, confirming model self-consistency.

- SysBias: mean deviates from median, indicating systematic outliers.

- ObsNoise: envelope width increases markedly, yet without skewness; random errors dominate.

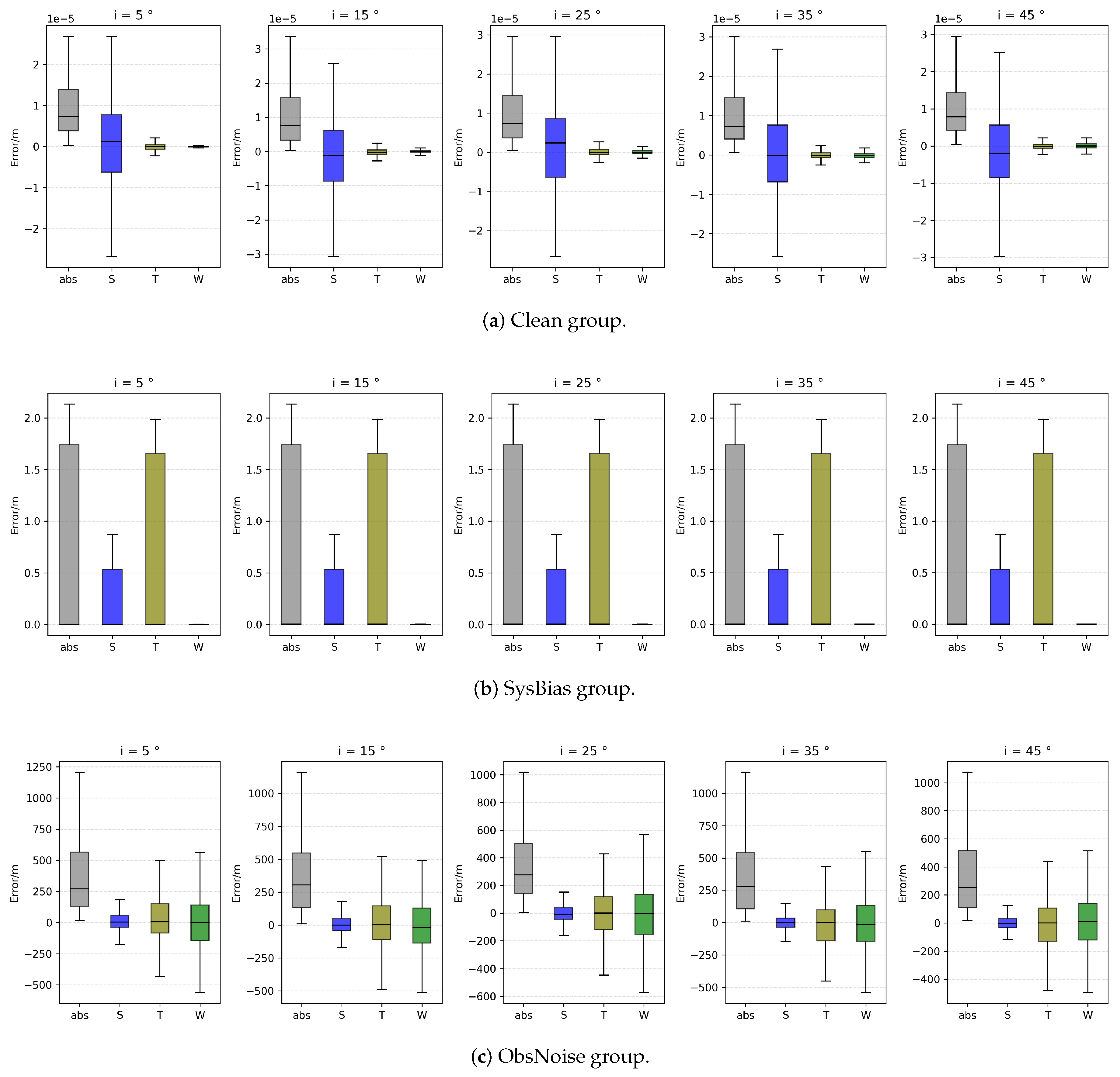

4.3. Parameter-Sensitivity Analysis

4.3.1. Effect of Inclination (Verification of Irrelevance)

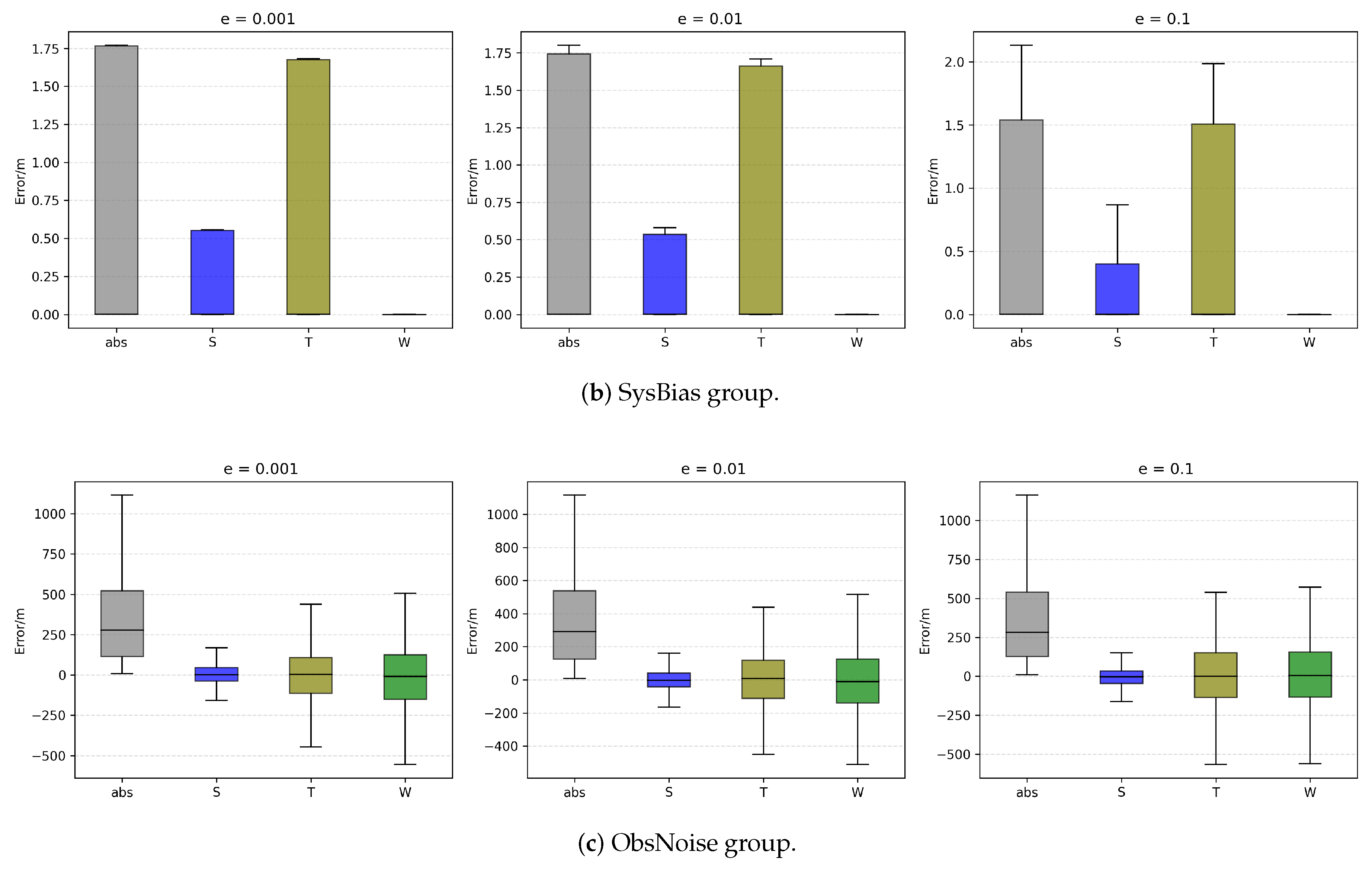

4.3.2. Coupled Effect of Semi-Major Axis and Perturbations

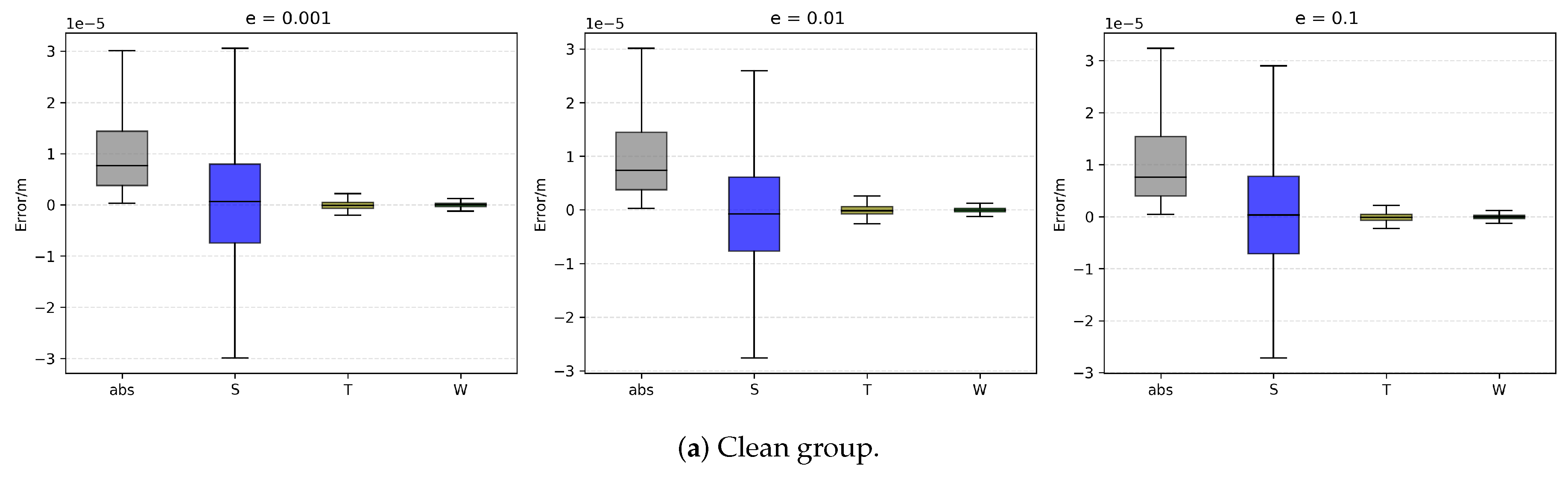

4.3.3. Modulation of Error Distribution by Eccentricity

4.3.4. Rank-Sum Sensitivity Test

- Semi-major axis is highly significant for the abs error in all scenes (, H 350–840), confirming orbital altitude as the most sensitive parameter. The R component is also significant under SysBias (), while T is significant only in SysBias and N is never significant, indicating that altitude amplifies errors mainly within the orbital plane.

- Inclination shows only marginal significance for the R component in the Clean scene (); all other components and scenes yield with , verifying that inclination has no statistically significant influence on 10-minute forecast error.

- Eccentricity gives and H values 0.05–2.9 (far below ) in every scene and component, demonstrating that within the commonly used eccentricity range the short-term error is not significantly affected by this parameter.

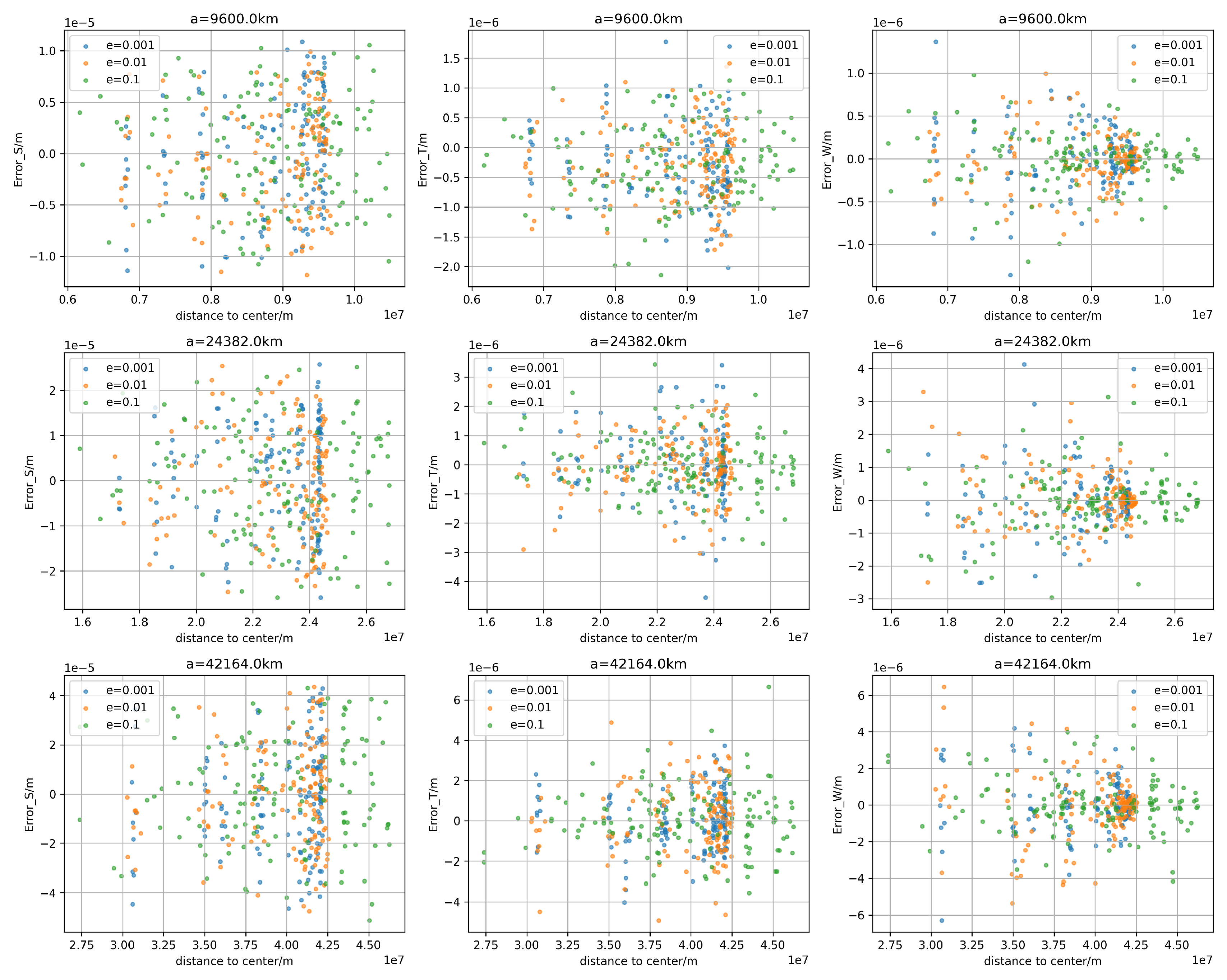

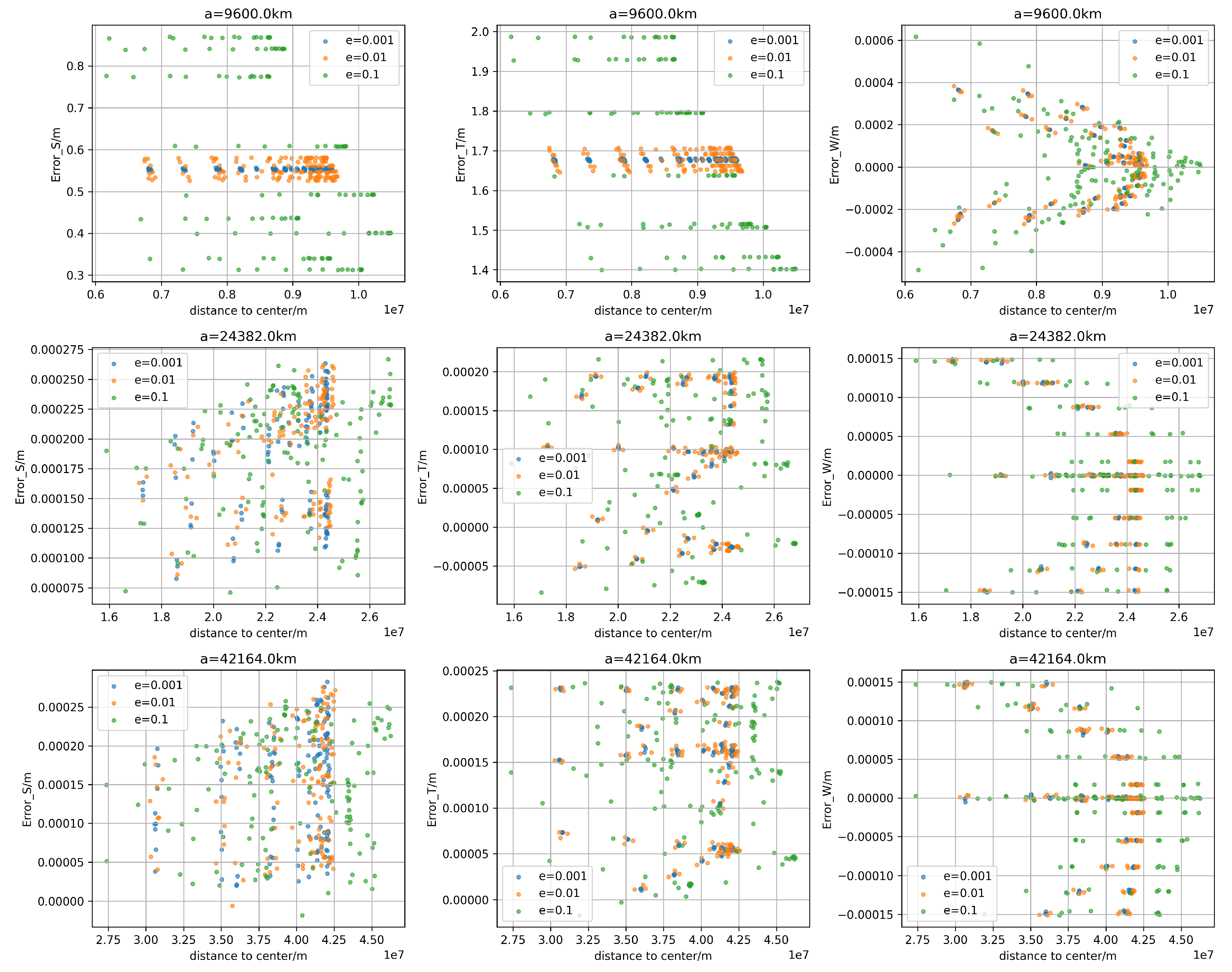

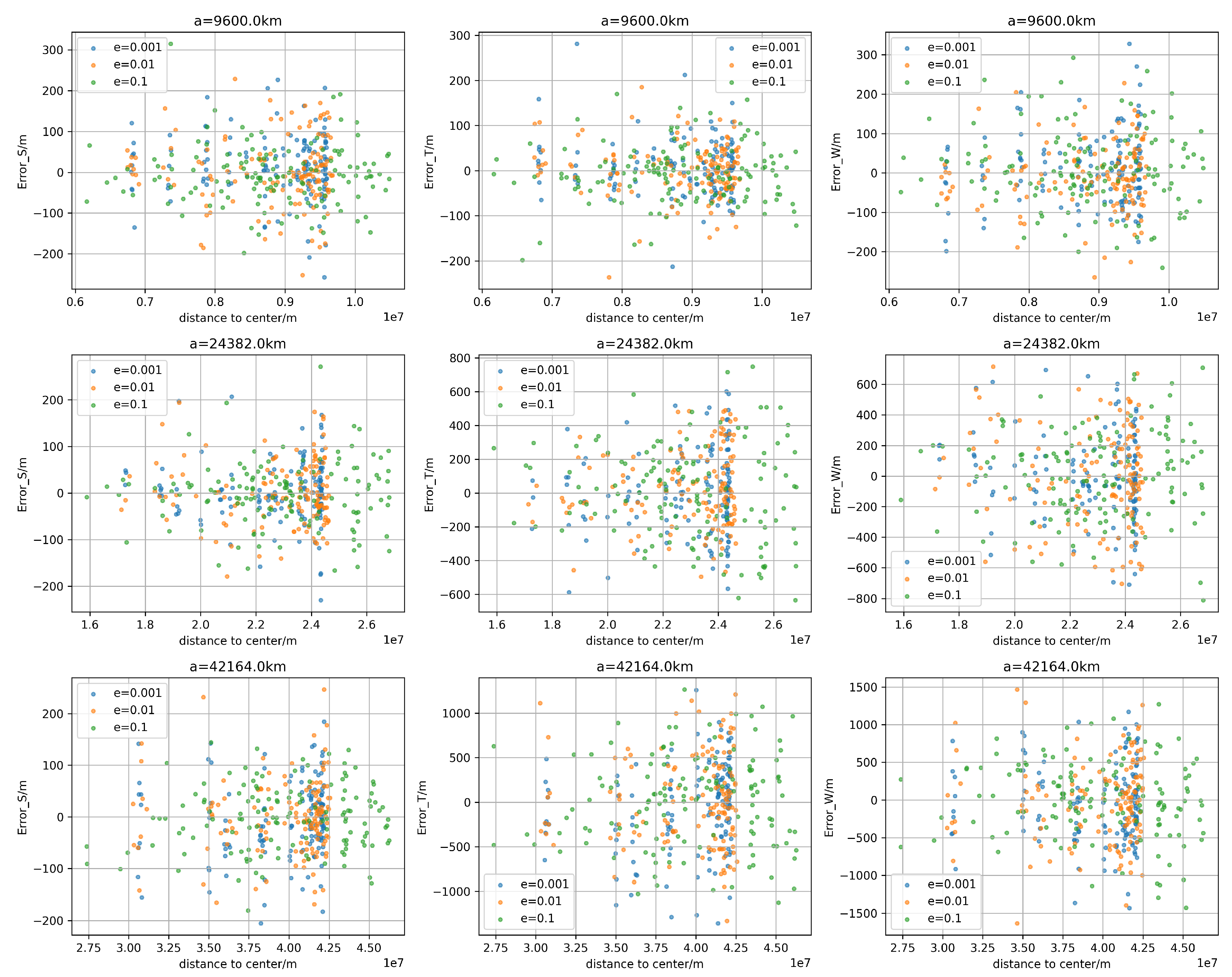

4.4. Visualisation of Combined Bias and Error Effects

4.4.1. Scatter Plots of Radial / Along-Track / Cross-Track Errors

4.4.2. Dominant-Factor Discrimination Between Bias and Noise

4.4.3. Summary of Experimental Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Current Practice under SysBias

5.2. Future Improvements and Extensions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, H.; Bai, X. Improving orbit prediction accuracy through supervised machine learning. Advances in Space Research 2018, 61(10), 2628–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Huang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H. Improvement of orbit prediction accuracy using extreme gradient boosting and principal component analysis. Open Astronomy 2022, 31, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondar, D. I.; Cabrera, R.; Zhdanov, D. V.; Rabitz, H. A. Wigner phase-space distribution as a wave function. Physical Review A 2013, 88, 052108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuz’menko, L. S.; Maksimov, S. G. Distribution functions in quantum mechanics and Wigner functions. Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 2002, 131, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkovnikov, A. Phase space representation of quantum dynamics. Annals of Physics 2010, 325, 1790–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoman, D. Applications of the Wigner distribution function in signal processing. EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing 2005, 2005, 264967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, A. H. The Wigner distribution: A time-frequency analysis tool. Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest 1994, 15, 298–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hush, M. R.; Carvalho, A. R. R.; Hope, J. J. Number-phase Wigner representation for scalable stochastic simulations of controlled quantum systems. Physical Review A 2012, 85, 023607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, J. F.; Maskell, S.; Ransom, M.; Ulbricht, H. Classical tracking for quantum trajectories. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.00276 2022.

- Vladimirov, I. G.; Petersen, I. R.; James, M. R. A phase-space formulation and Gaussian approximation of the filtering problem for nonlinear quantum stochastic systems. Journal of Systems Science and Complexity 2017, 30, 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Bondar, D. I.; Cabrera, R.; Lompay, R. R.; Ivanov, M. Yu.; Rabitz, H. A. Operational dynamic modeling transcending quantum and classical mechanics. Physical Review Letters 2012, 109, 190403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, H. A Low Earth Orbit Satellite-Orbit Extrapolation Method. Aerospace 2024, 11, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasankar, P.; Lewis Jr, B. G.; Probe, A. B.; et al. A validation framework for orbit uncertainty propagation using real satellite data applied to orthogonal probability approximation. Acta Astronautica 2025, 232, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallado, D. A.; Crawford, P. SGP4 Orbit Determination. AIAA/AAS Astrodynamics Specialist Conference 2008, AIAA 2008-6770.

- Tapley, B. D.; Schutz, B. E.; Born, G. H. Statistical Orbit Determination; Academic Press: Burlington, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kavitha, R.; Vathsal, S.; Desai, U. B. Extended Kalman filter-based precise orbit estimation of LEO satellites. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julier, S. J.; Uhlmann, J. K. Unscented Filtering and Nonlinear Estimation. Proceedings of the IEEE 2004, 92, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardal, P. C. P. M.; Kuga, H. K.; de Moraes, R. V. Analyzing the Unscented Kalman Filter Robustness for Satellite Orbit Determination. Journal of Aerospace Technology and Management 2013, 5, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiku, A. K.; Mathur, R.; Fitz-Coy, N. G. Statistical Orbit Determination using the Particle Filter for Incorporating Non-Gaussian Uncertainties. NASA Technical Report 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Crassidis, J. L. Particle Filtering for Sequential Spacecraft Attitude Estimation. AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference 2004, AIAA 2004-4855.

- Bevanda, P.; Sosnowski, S.; Hirche, S. Koopman operator dynamical models: Learning, analysis and control. Annual Reviews in Control 2021, 52, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, I. Koopman–von Neumann approach to quantum simulation of nonlinear classical dynamics. Physical Review Research 2020, 2, 043102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondar, D. I.; Gay-Balmaz, F.; Tronci, C. Koopman wavefunctions and classical–quantum correlation dynamics. Proceedings of the Royal Society A 2019, 475, 20180879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chruściński, D.; Jamiolkowski, A. Koopman’s approach to dissipation. Reports on Mathematical Physics 2006, 57, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigner, E. On the quantum correction for thermodynamic equilibrium. Physical Review 1932, 40, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtright, T. L.; Zachos, C. K. Quantum mechanics in phase space. Asia Pacific Physics Newsletter 2012, 01, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W. H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Nature 2003, 412, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragoman, D.; Dragoman, M. Quantum-classical analogues; Springer: Berlin; New York, 2004; Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- Haroche, S.; Raimond, J. M. Exploring the quantum: atoms, cavities and photons; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Ma, B.-Q. Quark Wigner distributions in a light-cone spectator model. Physical Review D 2015, 91(3), 034019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L. Time-frequency distributions—A review. Proceedings of the IEEE 1989, 77, 941–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrie, C.; Emerson, J. Frame representations of quantum mechanics and the necessity of negativity in quasi-probability representations. New Journal of Physics 2009, 11, 063040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, V.; Ferrie, C.; Gross, D.; Emerson, J. Negative quasi-probability as a resource for quantum computation. New Journal of Physics 2012, 14, 113011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; Eisert, J. Positive Wigner functions render classical simulation of quantum computation efficient. Physical Review Letters 2012, 109, 230503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurek, W. H. Sub-Planck structure in phase space and its relevance for quantum decoherence. Nature 2001, 412, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, B. O. Hamiltonian systems and transformation in Hilbert space. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1931, 17, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Zur Operatorenmethode in der klassischen Mechanik. Annals of Mathematics 1932, 33, 587–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Zusätze zur Arbeit “Zur Operatorenmethode...”. Annals of Mathematics 1932, 33, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzi, E.; Pagani, C. Universal local symmetries and nonsuperposition in classical mechanics. Physical Review Letters 2010, 105, 150604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brumer, P.; Gong, J. Born rule in quantum and classical mechanics. Physical Review A 2006, 73, 052109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, P.; Gozzi, E.; Mauro, D. Koopman–von Neumann formulation of classical Yang–Mills theories: I. Annalen der Physik 2006, 518, 177–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasone, M.; Jizba, P.; Kleinert, H. Path-integral approach to’t Hooft’s derivation of quantum physics from classical physics. Physical Review A 2005, 71, 052507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Values | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-major axis | a | 9600, 24382, 42164 | km |

| Eccentricity | e | 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 | – |

| Inclination | i | 5, 15, 25, 35, 45 | ○ |

| Right ascension of node | 0, 120, 240 | ○ | |

| Argument of perigee | 0, 120, 240 | ○ |

| Perturbation | Symbol | |

|---|---|---|

| Earth oblateness | ||

| Atmospheric drag | ||

| Solar radiation pressure |

| Scene | Factor | Error | H | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clean | Inclination | abs | 0.929 | 0.9203 |

| Clean | Inclination | R | 9.511 | 0.0495 |

| Clean | Inclination | T | 8.021 | 0.0908 |

| Clean | Inclination | N | 5.047 | 0.2825 |

| Clean | Semi-Major Axis | abs | 370.698 | 0.0000 |

| Clean | Semi-Major Axis | R | 0.569 | 0.7523 |

| Clean | Semi-Major Axis | T | 26.254 | 0.0000 |

| Clean | Semi-Major Axis | N | 0.543 | 0.7624 |

| Clean | Eccentricity | abs | 0.493 | 0.7814 |

| Clean | Eccentricity | R | 1.799 | 0.4067 |

| Clean | Eccentricity | T | 0.344 | 0.8418 |

| Clean | Eccentricity | N | 0.088 | 0.9568 |

| SysBias | Inclination | abs | 0.323 | 0.9883 |

| SysBias | Inclination | R | 7.676 | 0.1042 |

| SysBias | Inclination | T | 2.105 | 0.7165 |

| SysBias | Inclination | N | 0.239 | 0.9934 |

| SysBias | Semi-Major Axis | abs | 809.385 | 0.0000 |

| SysBias | Semi-Major Axis | R | 832.716 | 0.0000 |

| SysBias | Semi-Major Axis | T | 843.947 | 0.0000 |

| SysBias | Semi-Major Axis | N | 0.006 | 0.9972 |

| SysBias | Eccentricity | abs | 0.467 | 0.7916 |

| SysBias | Eccentricity | R | 0.317 | 0.1042 |

| SysBias | Eccentricity | T | 0.158 | 0.7165 |

| SysBias | Eccentricity | N | 0.101 | 0.9934 |

| ObsNoise | Inclination | abs | 2.352 | 0.6713 |

| ObsNoise | Inclination | R | 3.728 | 0.4441 |

| ObsNoise | Inclination | T | 2.426 | 0.6580 |

| ObsNoise | Inclination | N | 1.934 | 0.7478 |

| ObsNoise | Semi-Major Axis | abs | 713.261 | 0.0000 |

| ObsNoise | Semi-Major Axis | R | 1.254 | 0.5343 |

| ObsNoise | Semi-Major Axis | T | 0.227 | 0.8928 |

| ObsNoise | Semi-Major Axis | N | 1.675 | 0.4329 |

| ObsNoise | Eccentricity | abs | 0.431 | 0.8059 |

| ObsNoise | Eccentricity | R | 2.518 | 0.2840 |

| ObsNoise | Eccentricity | T | 0.048 | 0.9761 |

| ObsNoise | Eccentricity | N | 2.892 | 0.2355 |

| time/sec | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 |

| error for Chebyshev [8,10] /m | 14.61 | 48.11 | 113.53 | 228.20 | 419.18 |

| error for Chebyshev [10,18] /m | 2.45 | 8.32 | 21.29 | 48.87 | 99.81 |

| error for Chebyshev [14,30] /m | 4.67 | 24.41 | 80.77 | 215.76 | 510.60 |

| time/min | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| error for LEO/meter | 5.9 | 9.8 | 17.9 | 29.0 | 42.2 | 56.4 | / | / | / | / | / |

| error for GEO/meter | 56.5 | 56.6 | 56.4 | 56.2 | 56.6 | 56.3 | 56.3 | 56.5 | 56.3 | 56.3 | 56.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).