Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

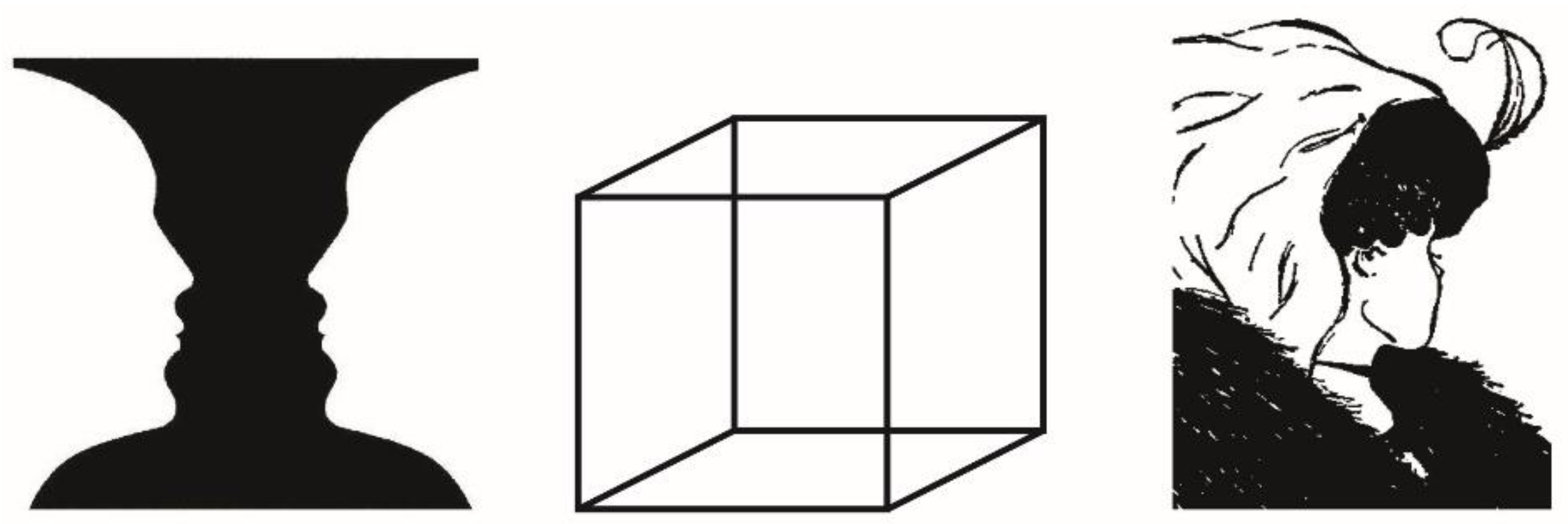

Ambiguous Images and Bistable Logotypes: Psychological Issues Involved

The Conveyance of Semantic Load of Bistable Logotypes

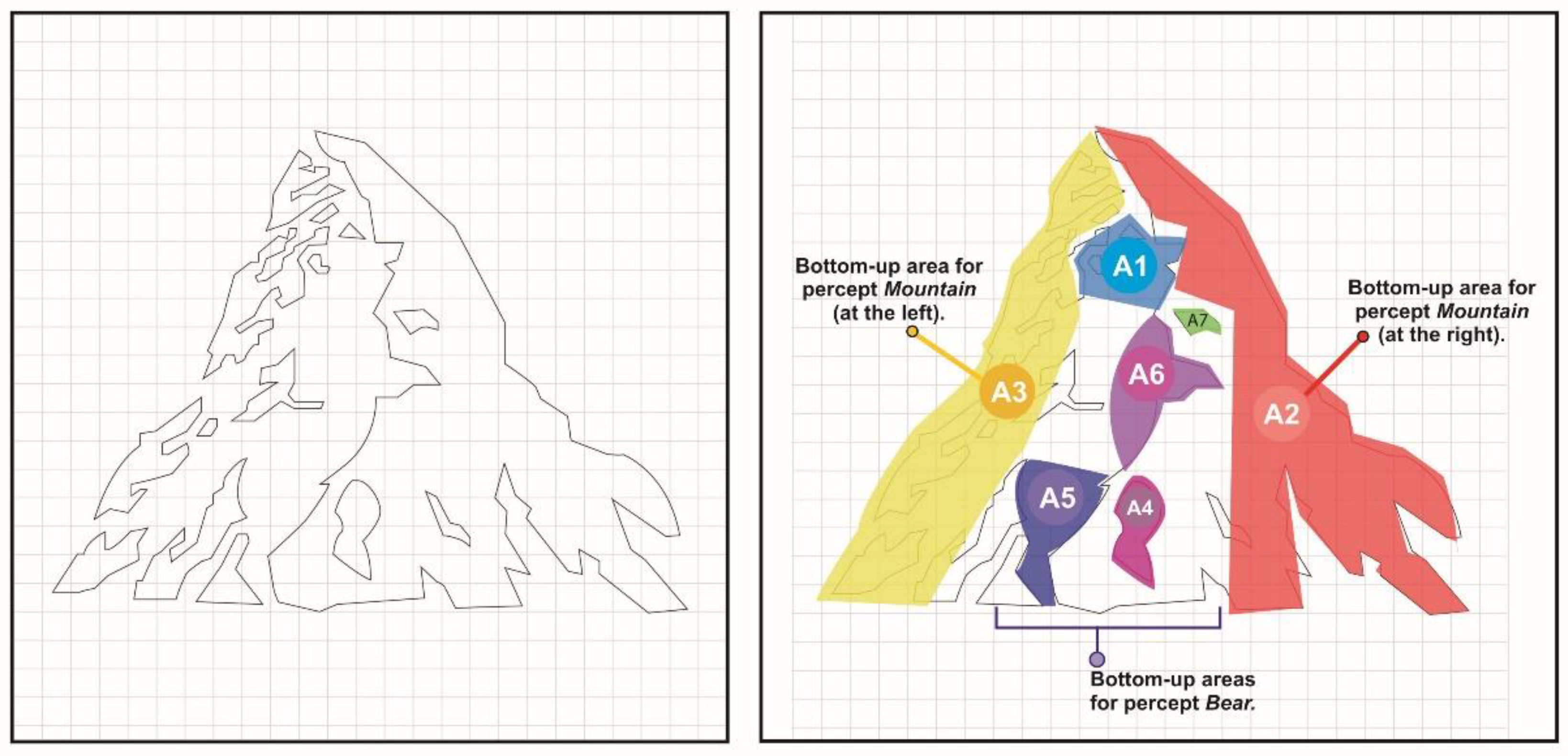

2. Related Work

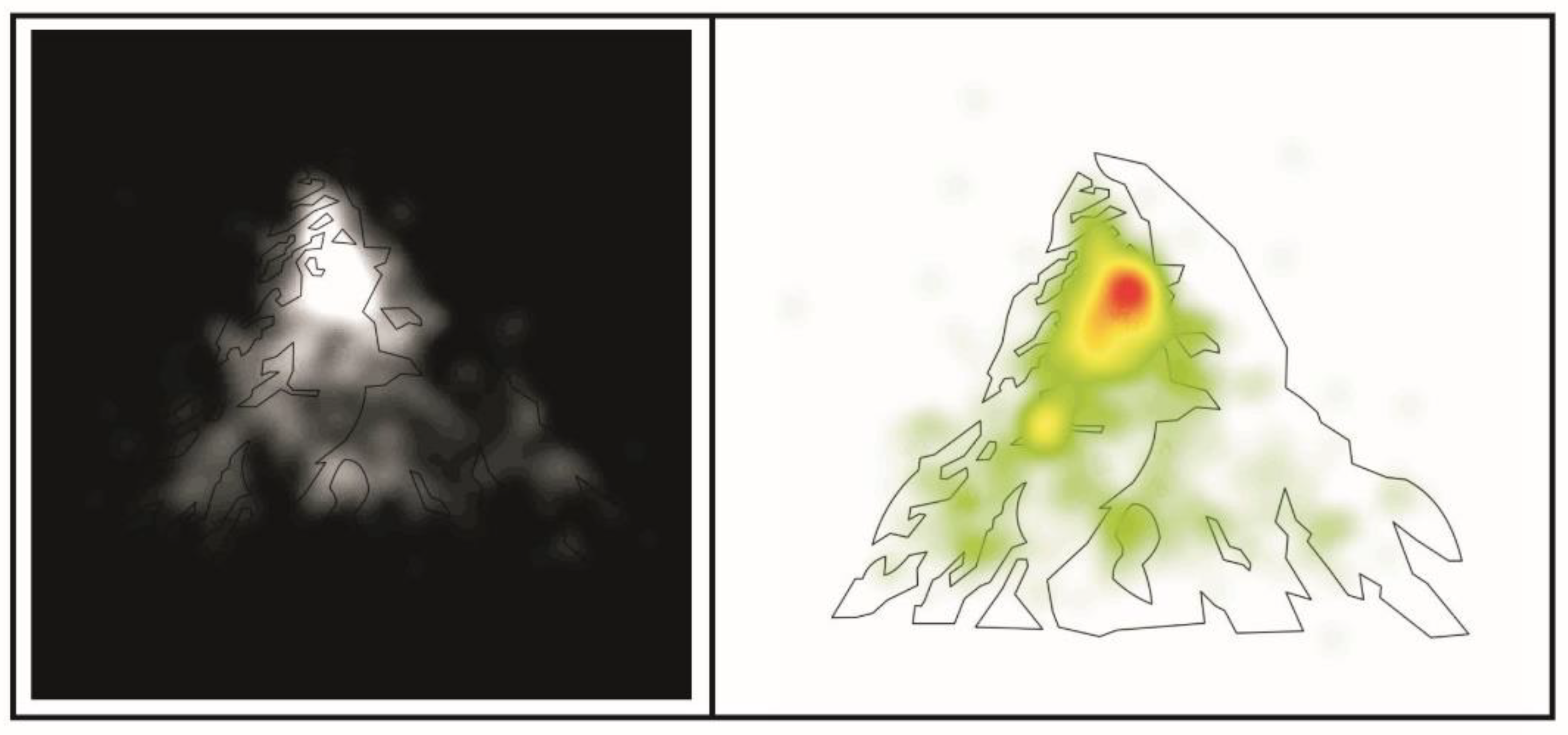

3. Method

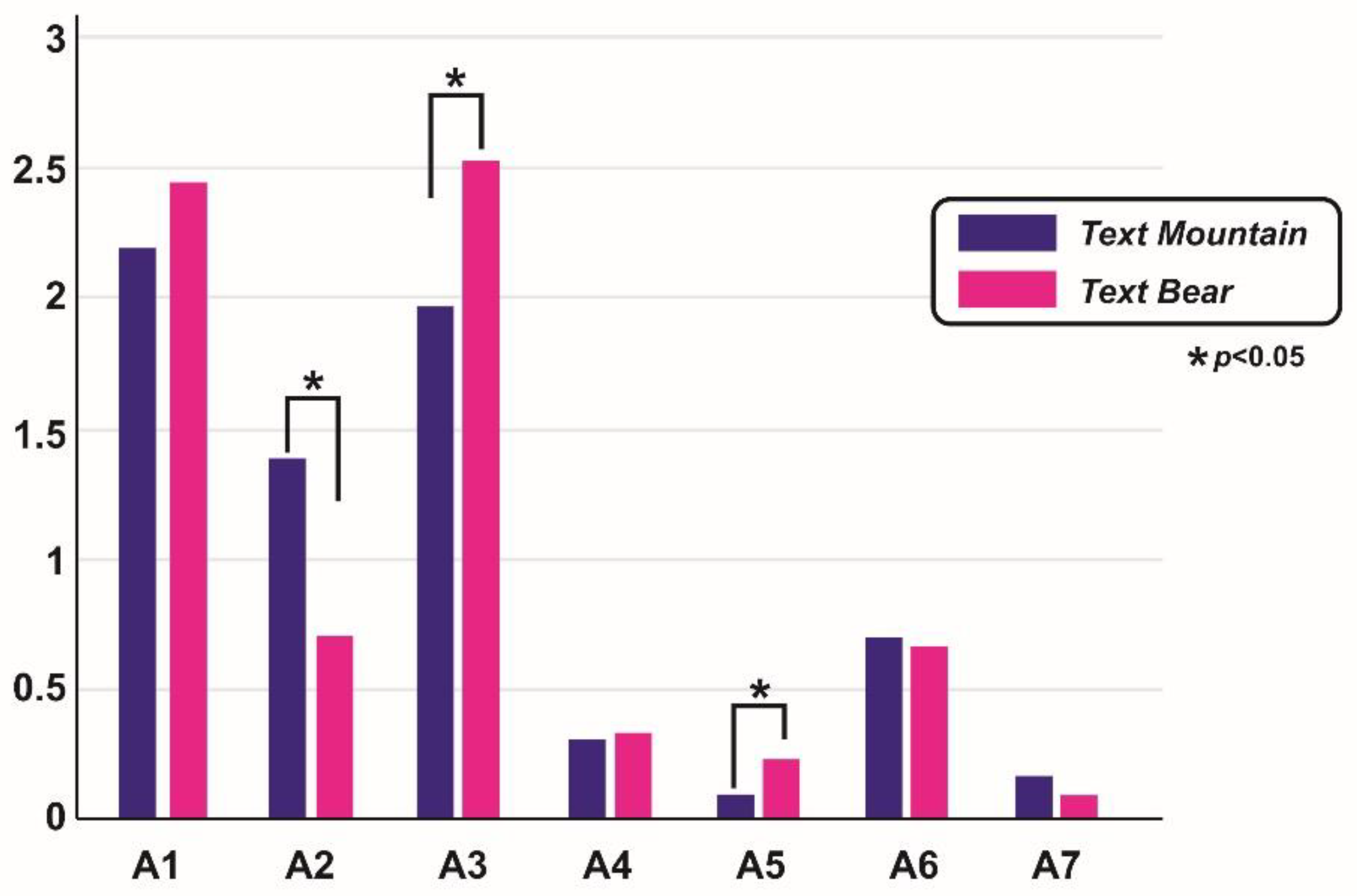

4. Results

5. Discussion and Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| AOIs | Areas of Interest |

| S.D | Standard Deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G. Can ocular fixations modulate the perception of a bistable logo? An eye-tracking study. Gráfica 2025, 13, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. Multistable perception of art-science imagery. Leonardo 2012, 45, 156–164. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y. H.; Chen, C. C. Eye-movement patterns for perceiving bistable figures. J. Vis. 2025, 25, 3–3. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G.; Castillo-Parra, H. Bistable perception: Neural bases and usefulness in psychological research. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2018, 11, 63–76. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G. Eficacia perceptual y comunicativa de un logotipo biestable. Un estudio experimental basado en tecnología eye-tracking. Rev. Texto Livre 2024, 17, e51494. [CrossRef]

- Intaité, M.; Noreika, V.; Šoliūnas, A.; Falter, C. M. Interaction of bottom-up and top-down processes in the perception of ambiguous figures. Vision Res. 2013, 89, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Leopold, D. A.; Logothetis, N. K. Multistable phenomena: changing views in perception. Trends Cognit. Sci. 1999, 3, 254–264. [CrossRef]

- Marroquín-Ciendúa, F.; Rodríguez-Martínez, G.; Rodríguez-Celis, H. G. Modulación de la percepción biestable: estudio basado en estimulación multimodal y registros de actividad oculomotora. Tesis Psicol. 2020, 15, 106–124. [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. H.; Karapanagiotidis, T.; Coggan, D. D.; Wailes-Newson, K.; Smallwood, J. Brain networks underlying bistable perception. NeuroImage 2015, 119, 229–234. [CrossRef]

- Intaité, M.; Kovisto, M.; Castelo-Branco, M. Event-related potential responses to perceptual reversals are modulated by working memory load. Neuropsychologia 2014, 56, 428–438. [CrossRef]

- Clément, G.; Demel, M. Perceptual reversal of bi-stable figures in microgravity and hypergravity during parabolic flight. Neurosci. Lett. 2012, 507, 143–146. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G. Perceptual reversals and creativity: is it possible to develop divergent thinking by modulating bistable perception? Rev. Investig. Desarro. Innov. 2023, 13, 129–144. [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, K.; Barnes, G. R.; Bahrami, B.; Kanai, R.; Overgaard, M.; Rees, G. Distinct MEG correlates of conscious experience, perceptual reversals and stabilization during binocular rivalry. Neuroimage 2014, 100, 161–175. [CrossRef]

- Muth, C.; Carbon, C. C. SeIns: Semantic instability in art. Art Perception 2016, 4, 145–184. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/artp/4/1-2/article-p145_7.xml (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Gamboni, D. Visual ambiguity and interpretation. RES: Anthropol. Aesthet. 2002, 41, 5–15. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G. Six bottom-up modulating areas are valued by observers after having viewed the Dalinian image ‘The invisible man’: a study based on ocular fixations analyses. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 1448–1456. Available online: https://theaspd.com/index.php/ijes/article/view/8547 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Khalil, E. L. Why does Rubin’s vase differ radically from optical illusions? Framing effects contra cognitive illusions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 597758. [CrossRef]

- Gale, A.; Findlay, J. Eye-movement patterns in viewing ambiguous figures. In Eye Movements and Psychological Functions: International Views; Groner, R., Menz, C., Fisher, D., Monty, R., Eds.; LEA: Hillsdale, NJ, 1983; pp 145–168. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, J.; Chen, Y.; Spence, C.; Yeh, S. Assessing the effects of audiovisual semantic congruency on the perception of a biestable figure. Consciousness Cogn. 2012, 21, 775–787. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G.; Castillo-Parra, H.; Rosa, P. J.; Marroquín-Ciendúa, F. Ocular fixations modulate audiovisual semantic congruency when standing in an upright position. Suma Psicol. 2021, 28, 43–51. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G.; Marroquín-Ciendúa, F.; Rosa, P. J.; Castillo-Parra, H. Perceptual reversals and time-response analyses within the scope of decoding a bistable image. Interdisciplinaria 2022, 39, 257–273. [CrossRef]

- Khrennikov, A. Quantum-like model of unconscious–conscious dynamics. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 997. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Hardstone, R.; He, B. J. Neural oscillations promoting perceptual stability and perceptual memory during bistable perception. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2760. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Grabowecky, M.; Susuki, S. Auditory-visual crossmodal integration in perception of face gender. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1680–1685. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G. The perception of a visual bistable design can be semantically modulated by an incomprehensible spoken language. New Design Ideas 2025, 9, 5–29. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G.; Sojo, J. Biestabilidad perceptual en rostros andróginos: análisis del efecto de congruencia semántica considerando registros de actividad oculomotora. Rev. Ibér. Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2022, E52, 133–147. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/aa17500f4faeaf59d9d99670f1b5d763/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1006393 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Rodríguez, G.; Marroquín-Ciendúa, F. Bottom-up modulation within the scope of consumers’ visual perception: the effect of previous ocular fixations on the perception of bistable logotypes. Int. J. Recent Adv. Multidiscip. Res. 2019, 6, 5129–5135. Available online: https://www.ijramr.com/sites/default/files/issues-pdf/2636.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Gross, J. Why Toblerone Is Dropping a Famous Swiss Mountain From Its Packaging. The New York Times [Digital Edition], 6 March 2023. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A748995601/AONE?u=anon~9af2c378&sid=googleScholar&xid=29f5d875 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Goolkasian, P.; Woodberry, C. Priming effects with ambiguous figures. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2010, 72, 168–178. [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Tong, F. Can attention selectively bias bistable perception? Differences between binocular rivalry and ambiguous figures. J. Vis. 2004, 4, 539–551. [CrossRef]

- Poom, L. Divergent mechanisms of perceptual reversals in spinning and wobbling structure-from-motion stimuli. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297963. [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, M. Visual inhomogeneity and eye movements in multistable perception. Percept. Psychophys. 1989, 46, 397–400. [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, M. A. Eye movements and perceptual multistability. Adv. Psychol. 1992, 88, 73–109. [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M.; Calderón, L. Notes for supporting an epistemological neuropsychology: contributions from three perspectives. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2013, 6, 107–118. [CrossRef]

- Tarder-Stoll, H.; Jayakumar, M.; Dimsdale-Zucker, H. R.; Günseli, E.; Aly, M. Dynamic internal states shape memory retrieval. Neuropsychologia 2020, 138, 107328. [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, M. Top-down modulation of unconscious ‘automatic’ processes: A gating framework. Adv. Cognit. Psychol. 2007, 3, 289.

- Kesoglou, A. M.; Mikellidou, K. The effect of semantic content on the perception of audiovisual movieclips. bioRxiv 2024, Artículo 2024.01.24.576956. [CrossRef]

- Delong, P.; Noppeney, U. Semantic and spatial congruency mould audiovisual integration depending on perceptual awareness. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gijs, B.; van Ee, R. Endogenous influences on perceptual bistability depend on exogenous stimulus characteristics. Vision Res. 2006, 46, 3393–3402. [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, M.; Kaneko, Y.; Yumoto, M.; Arima, K. Perceptual change in response to a bistable picture increases neuromagnetic beta-band activities. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 61, 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H. Y.; Chuang, H. C. An eye-tracking-based investigation on the principle of closure in logo design. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2024, 17, Artículo e3. [CrossRef]

- Mamassian, P.; Goutcher, R. Temporal dynamics in bistable perception. J. Vis. 2025, 5, 361–375. [CrossRef]

- Yaman, H.; Yaman, Ş. The effect of gestalt theory on emblem and logo design. Uluslar. Akad. Birikim Derg. 2022, 5. Available online: https://akademikbirikimdergisi.com/index.php/uabd/article/view/63 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Rach, S.; Huster, R. J. In search of causal mechanisms underlying bistable perception. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 689–690. [CrossRef]

- De Marchis, G. P.; Reales-Avilés, J. M.; Rivero, M. D. P. Comparative values of variables related to brand logos. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2018, 22, 75–87. [CrossRef]

- Dehaghin, R. The Applications and Effects of Gestalt Theory in Logotype design. Humanit. Nat. Sci. J. 2023, 4, 597–610. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, K.; Adiloglu, F. Analyzing the role of gestalt elements and design principles in logo and branding. Int. J. Commun. Media Sci. 2023, 10, 33–43. [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, E.; Rodríguez-Martínez, G. Análisis de movimientos oculares durante la observación del logotipo biestable de Toblerone. Expeditiorepositorio.utadeo 2024. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12010/34421 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Andéhn, M.; Decosta, P. L. The variable nature of country-to-brand association and its impact on the strength of the country-of-origin effect. Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 33, 852–866. [CrossRef]

- Rüdisser, J.; Schirpke, U.; Tappeiner, U. Symbolic entities in the European Alps: Perception and use of a cultural ecosystem service. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 39, 100980. [CrossRef]

- Calboli, I. Chocolate, Fashion, Toys and Cabs: The Misunderstood Distinctiveness of Non-Traditional Trademarks. IIC 2018, 49, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Burmann, C.; Riley, N. M.; Halaszovich, T.; Schade, M. Identity-Based Brand Management; Springer Gabler: 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bucher-Edwards, E.; Grimmer, L.; Grimmer, M. Using Place-of-Origin Branding Strategies to Market Australian Premium-Niche Whisky and Gin Products. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2023, 35, 135–153. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Wei, D.; Li, H.; Yu, C.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Q. The vase–face illusion seen by the brain: An event-related brain potentials study. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2009, 74, 69–73. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. J.; Lim, J. H. A comprehensive review on logo literature: research topics, findings, and future directions. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 1291–1365. [CrossRef]

- Kornmeier, J.; Hein, C. M.; Bach, M. Multistable perception: when bottom-up and top-down coincide. Brain Cognit. 2009, 69, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Hartcher-O’Brien, J.; Soto-Faraco, S.; Adam, R. A matter of bottom-up or top-down processes: The role of attention in multisensory integration. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2017, 11, Artículo 5. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, P. What do your eyes say? Bridging eye movements to consumer behavior. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2015, 8, 90–103. [CrossRef]

- Nada, M.; Azmy, A. Eye-tracking in out-of-home advertising: Exploring the application of Gestalt principles. Int. Des. J. 2023, 13, 437–446. [CrossRef]

- Raz, A.; Lamar, M.; Buhle, J. T.; Kane, M. J.; Peterson, B. S. Selective biasing of a specific bistable-figure percept involves fMRI signal changes in frontostriatal circuits: A step toward unlocking the neural correlates of top-down control and self-regulation. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2007, 50, 137–156. [CrossRef]

- Girisken, Y.; Bulut, D. How do consumers perceive a/an logotype/emblem in the advertisements: an eye tracking study. Int. J. Strateg. Innov. Mark. 2014, 1, 198–209. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; Rodríguez, G. Generación del concepto creativo publicitario en función del modelo de fases sugerido por Graham Wallas: un estudio cualitativo basado en las teorías asociacionista y gestáltica. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 1252–1273. [CrossRef]

- Puškarević, I.; Nedeljković, U.; Dimovski, V.; Možina, K. An eye tracking study of attention to print advertisements: Effects of typeface figuration. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2016, 9, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, G. Impact of Face Inversion on Eye-Tracking Data Quality: A Study Using the Tobii T-120. In Applied Informatics. ICAI 2024. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Florez, H., Astudillo, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2025; Vol. 2237. [CrossRef]

- Peschel, A. O.; Orquin, J. L.; Loose, S. M. Increasing consumers’ attention capture and food choice through bottom-up effects. Appetite 2019, 132, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, R.; Chowdhury, A. Presence of Gestalt Traits in a Brand Logo and Its Impact in Evoking the Intended Meaning. In Recent Advancements in Product Design and Manufacturing Systems. IPDIMS 2023. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Deepak, B. B. V. L., Bahubalendruni, M. R., Parhi, D., Biswal, B. B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.; Hong, S. W. Semantic-based crossmodal processing during visual suppression. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 722. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G. The semantic congruency effect into bistable visual perception: a study based on tones of voice as top-down modulating stimuli. Int. J. Recent Adv. Multidiscip. Res. 2019, 6, 5143–5149. Available online: https://mail.ijramr.com/sites/default/files/issues-pdf/2647.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Spence, C. Crossmodal correspondences: A tutorial review. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2011, 73, 971–995. [CrossRef]

- Pálffy, Z.; Farkas, K.; Csukly, G.; Kéri, S.; Polner, B. Cross-modal auditory priors drive the perception of bistable visual stimuli with reliable differences between individuals. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16943. [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Squire, S. Multisensory integration: Maintaining the perception of synchrony. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, R519–R521. [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Robayo, S. D. Análisis de fijaciones oculares durante la observación e interpretación de logotipos biestables: un estudio basado en técnicas de autoreporte. M. S. Thesis, Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Bogotá, 2020. Available online: https://expeditiorepositorio.utadeo.edu.co/handle/20.500.12010/16382 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Holmqvist, K.; Nyström, M.; Andersson, R.; Dewhurst, R.; Jarodzka, H.; van De Weijer, J. Eye-Tracking. A Comprehensive Guide to Methods and Measures; Oxford University Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2011.

- Arango, C. A.; Rodríguez-Martínez, G.; Marroquín-Ciendúa, F. La contaminación visual en Bogotá: análisis de cargas visuales en localidades con alta estimulación publicitaria. Rev. Investig. Desarro. Innov. 2021, 11, 373–386. [CrossRef]

- Abed, F. Cultural influences on visual scanning patterns. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1991, 22, 525–534. [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Wang, L.; Sun, Z.; Engel, S. A.; He, S. The independent and shared mechanisms of intrinsic brain dynamics: Insights from bistable perception. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, Artículo 589. [CrossRef]

- Nuthmann, A. How do the regions of the visual field contribute to object search in real-world scenes? Evidence from eye movements. J. Exp. Psychol.: Hum. Percept. Perform. 2014, 40, 342. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Arteaga, D.; He, B. J. Brain mechanisms for simple perception and bistable perception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, E3350–E3359. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, M.; Rodríguez-Martínez, G. Analyzing emotional and attentional responses to promotional images using a remote eye-tracker device and face-reading techniques. In Applied Informatics. ICAI 2024. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Florez, H., Astudillo, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2025; Vol. 2237, pp 44–54. [CrossRef]

| AOIs | Statistical data | Text Mountain | Text Bear | p-value |

| A1 | Mean | 2.179411765 | 2.453235294 | 0.326572285 |

| A1 | Standard deviation | 1.191494964 | 1.349892747 | |

| A1 | Variance | 1.41966025 | 1.822210428 | |

| A2 | Mean | 1.379411765 | 0.701470588 | 0.002591325 |

| A2 | Standard deviation | 1.192776088 | 0.515352967 | |

| A2 | Variance | 1.422714795 | 0.265588681 | |

| A3 | Mean | 1.976470588 | 2.522352941 | 0.038637319 |

| A3 | Standard deviation | 1.272444277 | 1.116425733 | |

| A3 | Variance | 1.619114439 | 1.246406417 | |

| A4 | Mean | 0.308823529 | 0.327647059 | 0.798612352 |

| A4 | Standard deviation | 0.283653274 | 0.272130303 | |

| A4 | Variance | 0.08045918 | 0.074054902 | |

| A5 | Mean | 0.098823529 | 0.232352941 | 0.018304235 |

| A5 | Standard deviation | 0.191513346 | 0.249497177 | |

| A5 | Variance | 0.036677362 | 0.062248841 | |

| A6 | Mean | 0.694705882 | 0.666470588 | 0.738765146 |

| A6 | Standard deviation | 0.462576679 | 0.430615362 | |

| A6 | Variance | 0.213977184 | 0.18542959 | |

| A7 | Mean | 0.168235294 | 0.094117647 | 0.402850046 |

| A7 | Standard deviation | 0.481603827 | 0.167804317 | |

| A7 | Variance | 0.231942246 | 0.028158289 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).