Introduction

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols transformed the perioperative management of patients in every aspect of modern surgery. The concept was firstly introduced by Henrik Kehlet in 1995 under the term fast-track surgery, however its popularity was significantly delayed and the first evidence-based consensus protocol for ERAS was published by the ERAS Society ® in 2005, referring to patients undergoing large bowel surgery [

1]. In gynecologic oncology, the concept of ERAS was firstly introduced in 2016 [

2] and society recommendations were provided in an updated form that was published in 2019 [

3].

The revolutionary concept of ERAS is based on the implementation of a series of perioperative measures that help attenuate the physiological stress response to surgery, leading to improved postoperative homeostasis that results in accelerated functional recovery [

4]. Specifically, ERAS protocols include a summary of recommendations that target the optimization of cardiovascular and pulmonary functions during the early postoperative period by emphasizing goal-directed fluid therapy, multimodal analgesia with opioid-sparing strategies, early mobilization, maintenance of normothermia, and early oral intake to support hemodynamic stability and preserve respiratory function [

3].

The adoption of ERAS in an international level seems to differ and to be dependent on the actual incorporation of a dedicated program [

5]. The actual percentage of adoption of individual elements of the ERAS pathway ranges between 40% and 95% with preemptive analgesia, antiemetic use, patient warming and plan for opioid minimization being the parameters that are more likely less adopted according to a recent meta-analysis that included 9,076 participants [

6]. In gynecology and gynecologic oncology, surgical drains also remain a critical component that seems to be disregarded as physicians seem to continue to be reluctant to adhere to current recommendations [

7].

The effectiveness of ERAS protocols is directly related to the actual proportion of elements that were actually followed during the perioperative period. Previous research has shown that compliance rates that exceed the threshold of 70-80% of the sum of recommendations seem to result in clinically meaningful benefit [

8,

9,

10]. This is not, however, easy to achieve or even maintain, as significant coordination among members of the multidisciplinary team, namely surgeons, anesthesiologists, nursing staff and other faculty is needed and must be followed up on a regular basis to ensure continuity in clinical practice [

11,

12].

Several factors may prevent physicians from successfully incorporating ERAS principles in individual patients. The most critical barriers of adherence are patient characteristics such as frailty, poor performance status, significant comorbidities, or complex surgical pathology that limits the feasibility of early mobilization or feeding [

13,

14]. Procedure specific factors may also hinder adherence to ERAS protocols and result in suboptimal compliance. Among those, high-surgical complexity procedures and prolonged operative times seem to be the predominant ones with almost half of medium/high-complexity operations (47%) showing <75% ERAS compliance[

15]. Nevertheless, the feasibility of ERAS has been already proposed, even among patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery [

16].

In the present prospective multi-institutional study, we investigate compliance rates and predictors of compliance with ERAS components in a cohort of patients offered surgical management for gynecological cancer.

Methods

Study Design and Protocol Registration

The present prospective observational study is based on an interim analysis of the Enhanced Recovery Protocols in Gynecologic Oncology (ERGO) study aims to investigate the feasibility of and compliance to a structured ERAS protocol among Gynecological Oncological Centers in Greece as well as to compare the outcomes among patients that fullfilled the minimum number of necessary criteria, compared to those that were enrolled in ERAS protocols but did not meet the sufficient necessary criteria. The study is designed to run under real-world conditions, as a structured ERAS protocol had not been introduced in most participating institutions beforehand; hence, randomization was not feasible. The overall target enrollment is 600 patients, to be accrued over the period October 2024 to July 2026. The present interim analysis is based on a sample of 300 participants.

All patients provided informed consent prior to participation in the present study which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, which ensures the ethical principles for medical research involving human participants, and is designed considering the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating centers and registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database (identifier: NCT06655506).

Data collection and Measured Variables

Data were collected prospectively using uniform electronic forms under the REDCap software managed by trained research coordinators at each center. Baseline patient characteristics were considered, including age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, comorbidities (e.g. hypertension, diabetes), cancer site and stage (latest FIGO staging system), performance status using the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score and ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) score and preoperative laboratory values. Intraoperative characteristics were also documented and those included the surgical approach (laparoscopy vs laparotomy), operative time, estimated blood loss, intraoperative transfusion requirement, complexity score of the procedure (using the Aletti surgical complexity score) and administered fluid volumes.

ERAS Protocol Implementation

The ERAS Society Guidelines for Gynecologic Oncology Surgery (2021 update) were considered as the reference framework. The ERAS pathway comprised standardized elements from the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care of gynecological cancer patients (

Table 1). Briefly, preoperative items emphasize patient preparation, optimized fasting, carbohydrate loading, and evidence-based prophylaxis. Intraoperative measures focus on multimodal analgesia, normothermia, goal-directed fluid therapy, and minimizing tubes and drains. Postoperative components promote early oral intake, mobilization, catheter removal, multimodal analgesia, dietary advancement, glycemic control, and fluid optimization.

Outcomes

Adherence to each ERAS item was documented as achieved or not achieved. The overall compliance rate was calculated as the percentage of elements fulfilled out of the total applicable ERAS components per patient. An arbitrary cut-off of 70% of fulfilled parameters was used to denote adequate adherence to the ERAS components per patient. Institutional compliance was determined by the mean adherence rate among patients treated in each center. The primary outcome investigated in the present study referred to the actual compliance rates of ERAS principles, using the aforementioned cut-off value. Compliance rates per individual ERAS parameter were also considered as well as interinstitutional variability in ERAS implementation. The effect of time on the adherence of protocols was investigated after subgrouping cases per institution and evaluating differences in compliance rates per 30 cases included. The impact of patient characteristics (age, BMI etc) and intraoperative characteristics (Aletti score, surgical duration etc) on ERAS compliance was also evaluated.

Sample Size Calculation–Decision Point of Interim Analysis

Previous multicenter ERAS audits in gynecologic oncology have reported compliance rates ranging between 56% and 89% depending on institutional experience and resource availability [

17,

18,

19]. Based on this evidence, a minimum sample of 300 patients was estimated to provide an 80% statistical power (1−β = 0.8) to detect a 15% difference in overall compliance among participating centers, assuming a two-sided α = 0.05.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 27.0 program (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Evaluation of data distribution was performed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and graphical methods. Continuous variables were presented as medians (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis test, depending on the number of groups. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with high ERAS compliance (≥70%) and favorable postoperative outcomes. The Backward stepwise method was applied, and odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were retrieved from the final model that demonstrated the best fit according to the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

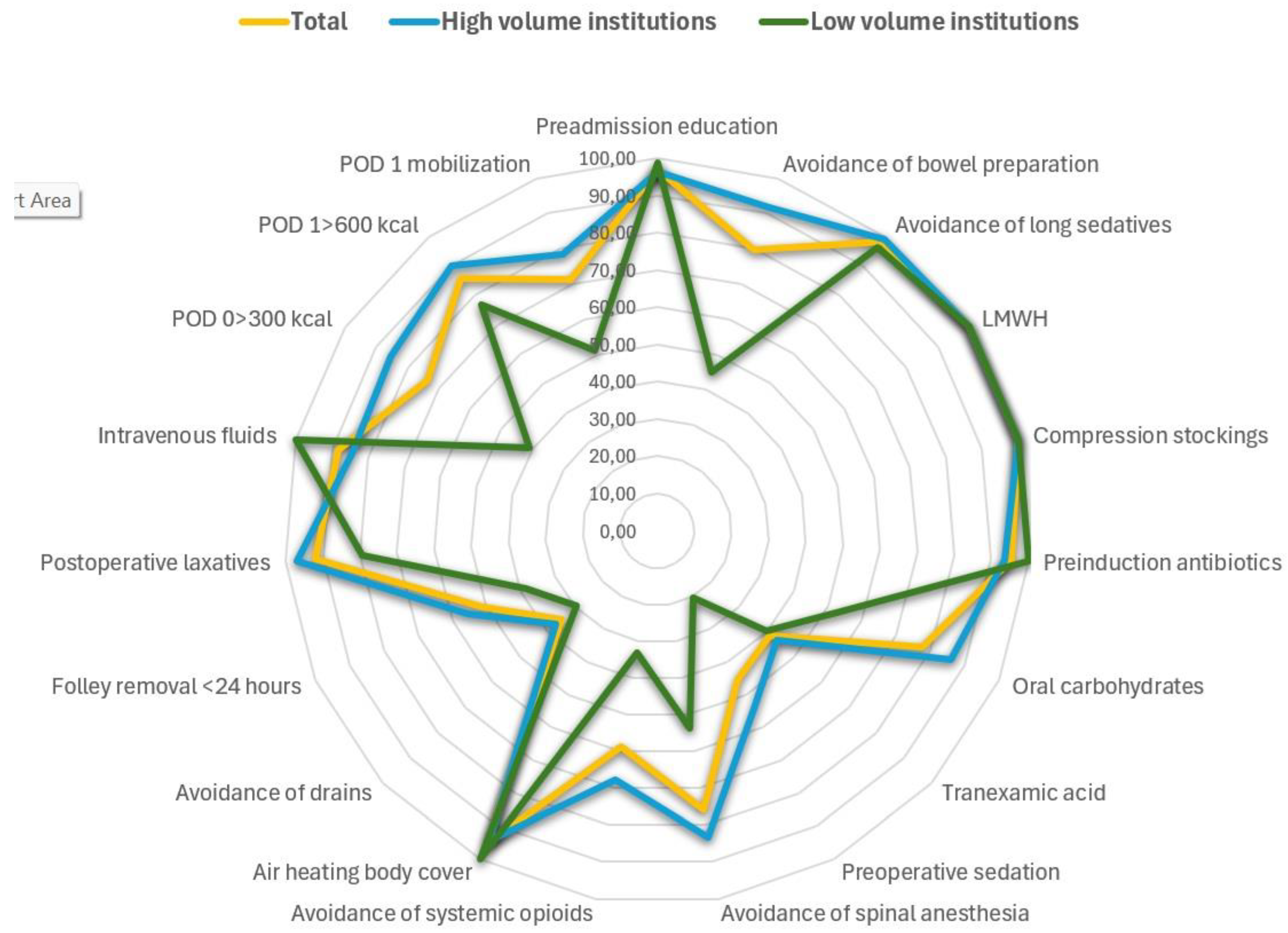

Three hundred patients were included in the present cohort of whom, 211 (70.33%) successfully reached the threshold of compliance in at least 70% of evaluated parameters. Differences were noted among institutions that participated in the study in terms of compliance standards and these seem to be positively related to the actual number of cases that were handled (

Table 2, Figure 1). Specifically, large volume centers exhibited the greatest adherence (83.5% and 84.4%, respectively), whereas the three lower-volume centers showed considerably lower adherence (26.9–35.0%). These findings indicate that a substantial portion of the observed inter-hospital variability may reflect differences in caseload and the maturity of ERAS pathway implementation.

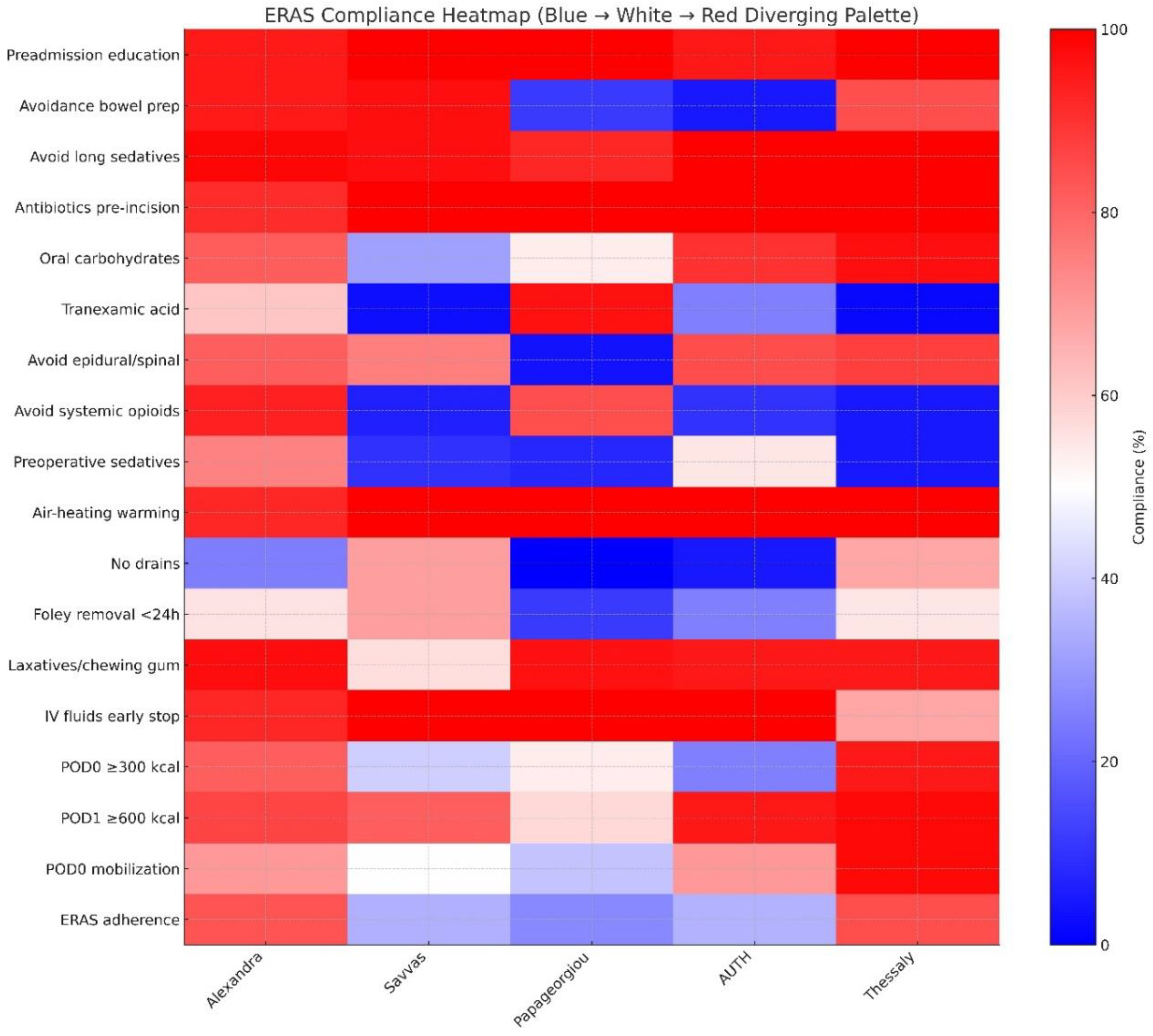

Among intraoperative ERAS elements, thromboprophylaxis and compression stockings were uniformly implemented (100%), indicating high compliance and an established adherence. Preadmission education was also provided in the majority of cases (291 patients - 97.0%) and did not differ significantly across institutions (p = 0.174). On the other hand, avoidance of bowel preparation showed substantial variation (χ² = 172.800, p < 0.001), as did administration of antibiotics prior to incision (χ² = 13.198, p = 0.010) and preoperative oral carbohydrates (χ² = 65.062, p < 0.001). Of note, tranexamic acid use demonstrated one of the highest degrees of institutional variability (χ² = 119.123, p < 0.001) (

Figure 2).

Intraoperative ERAS elements denoted marked inter-institutional differences. Specifically, preoperative sedative use differed significantly (χ² = 128.880, p < 0.001), as did avoidance of epidural/spinal anesthesia (χ² = 81.728, p < 0.001) and avoidance of systemic opioids (χ² = 216.890, p < 0.001). Use of forced-air warming devices varied across centers (χ² = 11.307, p = 0.023). Drain use also differed substantially (χ² = 74.471, p < 0.001). Many of these differences were more pronounced in the lower-volume centers, where small sample sizes produced larger proportional shifts (

Figure 2).

Similarly, differences were also noted in a large proportion of postoperative ERAS elements with high-volume centers demonstrating more consistent application of these elements, whereas low-volume centers exhibitng greater heterogeneity. Specifically, Foley catheter removal (<24 hours) varied by institution (χ² = 27.389, p < 0.001), as did the use of postoperative laxatives or chewing gum (χ² = 66.005, p < 0.001) and continuation of intravenous fluids (χ² = 40.690, p < 0.001). Likewise, early oral intake on POD 0 (>300 kcal) and POD 1 (>600 kcal) differed markedly across hospitals (χ² = 68.558 and 28.337, respectively; both p < 0.001). Finally, early mobilization on POD 0 also showed significant variation (χ² = 43.961, p < 0.001) (

Figure 2).

Multivariate regression analysis was used to evaluate demographic factors (age, BMI, smoking status), comorbidities (diabetes), ECOG performance status, tumour type, and surgical complexity, that contribute to optimal (>70%) ERAS compliance (

Table 3) . Of all factors, surgical complexity and ECOG performance status remained independently associated with ERAS adherence after adjusting for BMI, age, smoking, diabetes, and cancer type. Increasing surgical complexity was associated with progressively lower adherence, with intermediate-complexity procedures showing distinctly reduced likelihood of full compliance compared with low-complexity cases, while the highest-complexity category demonstrated an even more extreme effect. Similarly, declining functional status, reflected by ECOG scores, was associated with a stepwise reduction in adherence, with the poorest-performing category showing a profound decrease in the odds of full compliance. Other factors including age, BMI, smoking, diabetes status, and tumor type, did not exhibit statistically meaningful associations. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was suggestive of adequate calibration of the model, an observation that indicates the model`s predictive probability was aligned with the actual distribution of ERAS adherence outcomes. However, in terms of explanatory performance, the Nagelkerke R² test (0.247), indicated that approximately one-quarter of the variance was accounted for by the predictors included in the analysis. Considering that in pragmatic data Nagelkerke R² values rarely exceed 0.3, the actual result (0.247) is evaluated as realistic and appropriate. However, taking into account that it explains a moderate portion of the variability that is observed, one should consider that other factors, not accounted in the model, also contribute to the observed variance.

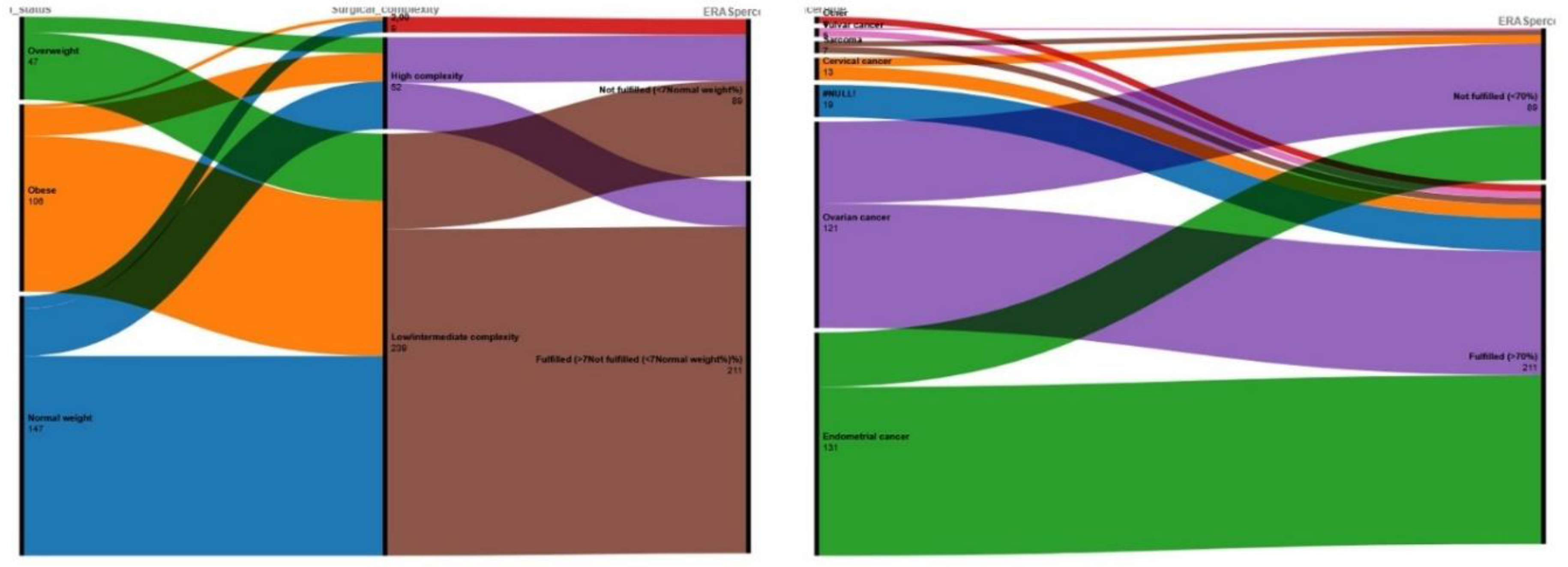

Despite the fact that cancer type did not seem to influence the actual decision to optimally implement ERAS parameters, we opted to evaluate the effect in the form of an alluvial plot to better understand how this variable distributes across adherence categories. Τηε alluvial plot demonstrated that the majority of patients with endometrial and ovarian cancer (that constitute the largest diagnostic groups) flow into the “Fulfilled (>70%)” adherence category, as reflected by the broad green and purple streams (

Figure 3 – right side). On the other hand, patients with less prominent cancer forms (cervical, vulvar, and sarcoma) exhibited a more heterogeneous pattern, with relatively greater proportions of patients flowing into the “Not fulfilled (<70%)” category compared with the larger cancer types.

Considering the results of the multivariate analysis, we constructed an alluvial plot to visualize the patterns of categorical flows between BMI groups, surgical complexity, and ERAS adherence (

Figure 3 – left side). We observed that normal-weight and overweight patients undergo low- or intermediate-complexity procedures, and these pathways predominantly lead to the “Fulfilled (>70%)” adherence category. Obesity as a factor equally distributes across both surgical complexity categories. It should be noted that a substantial proportion of obese patients, submitted low/intermediate-complexity surgery, ultimately receives an optimal ERAS perioperative plan. On the other hand, high-complexity procedures, irrespective of BMI category, seem to flow into the “Not fulfilled (<70%)” category, producing a concentrated purple stream toward this outcome.

Discussion

Principal Findings

The findings of this prospective multi-institutional cohort of 300 patients undergoing gynecologic oncology surgery within an ERAS framework, suggest a high optimal adherence rate (≥70%) as 211 patients (70.33%) reached the predefined threshold for adequate compliance. Implementation of ERAS protocols is expected to vary significantly, particularly when firstly introduced, with high-volume institutions demonstrating the highest adherence rates and in our cohort the difference was substantial as high-volume institutions superseded the necessary threshold easily (83.5% and 84.4%), while the three lower-volume centers exhibited markedly inferior performance, achieving only 26.9% to 35.0% adherence. This pattern suggests that institutional experience, workflow maturity, and cumulative exposure to ERAS practices are key determinants of successful protocol application and indicate that a significant number of cases is needed to help establish a robust protocol with optimal adherence rates. Examination of individual ERAS components revealed a heterogeneous landscape: while some preoperative measures such as thromboprophylaxis, compression stockings, and preadmission education showed near-universal implementation, other elements, including avoidance of bowel preparation, administration of preoperative antibiotics, preoperative carbohydrate loading, and tranexamic acid use, demonstrated significant inter-institutional variability. Intraoperative practices were even more inconsistent, with large disparities noted in the use of preoperative sedation, avoidance of regional anesthesia techniques, minimization of systemic opioids, application of forced-air warming, and drain utilization. Postoperative elements similarly varied across centers, particularly regarding early Foley catheter removal, laxative or chewing gum use, continuation of intravenous fluids, early oral intake on postoperative days 0 and 1, and early mobilization. It should be noted at this point that the components that were more likely to be implanted are those that have gained acceptance in the perioperative care, before the implementation of ERAS guidelines, whereas new components that have not been traditionally used were more likely to not gain universal acceptance. The results of our multivariate analysis indicate that the only strong predictors of optimal ERAS adherence were surgical complexity and ECOG performance status. Specifically, increasing operative complexity and poorer functional status each associated with progressively lower likelihood of achieving compliance ≥70%, an observation that seems reasonable during the first steps of a newly instituted perioperative program, where teams are still adapting workflows, clinical judgment may default on the side of caution in high-risk or technically demanding cases, and the full integration of ERAS principles into complex surgical pathways has not yet reached operational maturity. Neither age, BMI, smoking, diabetes, nor tumor type were significantly associated with adherence. Complementary alluvial visualizations reinforced these findings by illustrating the strong directional flow from high-complexity procedures toward the “Not fulfilled” category, regardless of BMI, and the predominance of endometrial and ovarian cancer patients within the “Fulfilled” adherence group.

Comparison with Existing Literature

Our findings are in accordance with current knowledge as suggested by a recent survey that was conducted across gynecologic oncologists in Europe that denotes widespread implementation of ERAS protocols but substantial variation in adherence to specific elements, and highlights that despite formal pathway adoption, key items such as early urinary catheter removal and avoidance of drains remain poorly implemented [

20]. Specifically, the overall adherence rate in this survey was comparable to that of our study, ranging between 60 and 80% among the 44% of participating centers. Similar to our study, thromboembolic prophylaxis was highly adopted by the majority of participants (79%) whereas, avoidance of bowel preparation demonstrated low compliance rates.

In line with these data, another recent multicenter cross-sectional study from Southwestern China, focusing on gastroenterology, gynecology, hepatobiliary surgery, and urology published by Mu et al. highlighted that achieving high adherence to ERAS protocols remains challenging, with considerable variability in compliance across institutions [

21]. Specifically, the authors of this study demonstrated an overall median adherence of 71.5%, a figure that is also similar to the proportion of patients in our study who achieved ≥70% compliance (70.33%). Nevertheless, in their study they did not mention a predetermined cut-off value of optimal ERAS adherence, therefore, somehow differentiating from our method of reporting. In line with our observation concerning the number of handled cases, Mu et al. also identified treatment in a tertiary center as an independent predictor of higher compliance. These converging observations reinforce the notion that ERAS implementation success is directly related to the level of organizational maturity, the existence of relevant resources and the actual familiarity and level of training of coordinated multidisciplinary teams. Additionally, both studies reveal significant heterogeneity across individual ERAS elements. Similar to our findings, where certain components such as preadmission education or thromboprophylaxis were nearly universally implemented while others showed marked variation, Mu et al. reported that while adherence to core items such as fasting avoidance exceeded 85%, compliance with components like preoperative carbohydrate loading remained as low as 42%.

The feasibility of implementing ERAS protocols in high surgical complexity procedures has been implied earlier by Pandraklakis et al in a cohort of 66 patients undergoing complex cytoreduction for advanced ovarian cancer, with or without the use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) [

16]. Similar results were also reported by a smaller cohort that included 31 patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC that suggested the positive effect of ERAS protocols in this population, together stating that the possibility of increased complications or readmissions was not increased [

22]. The most important evidence comes from the PROFAST trial that also targeted high complexity score procedures and reported a surprisingly high overall compliance that reached 92% [

23]. It should be noted that in this study, the authors reported no differences postoperative complications among patients that were randomized in the ERAS arm and control patients. This observation was also confirmed for major complications, including those that referred to the anastomotic site. In our study a clear negative effect on ERAS protocol compliance was observed with increasing surgical complexity. Taking in mind the results of the aforementioned studies, it seems that while high compliance is achievable, this can be typically observed among centers with long-standing ERAS culture, robust multidisciplinary coordination, and substantial procedural volume. Although, to date, relevant evidence is missing from the literature, multiple barriers may be observed in the institution of ERAS protocols including limited familiarity and confidence among staff, logistical constraints, and reluctance to fully apply early feeding and mobilization, particularly among patients that received multivisceral resections that increase their frailty index.

It should be noted that several of the ERAS elements with the lowest adherence in our cohort were primarily driven by anesthesiology practice. In particular, avoidance of preoperative sedation, minimization of systemic opioids, use of regional anesthesia techniques, maintenance of normothermia, and administration of tranexamic acid all demonstrated marked inter-institutional differences, often among the highest variability observed across the entire pathway as indicated in

Figure 2. Considering that these components are largely controlled by anesthesiologists, their limited engagement likely reflects differing levels of familiarity with ERAS principles as well as potential variation in training, during the early implementation phase. This interpretation is further supported by the observation that adherence was highest for elements traditionally adopted in routine perioperative workflow, mainly thromboprophylaxis and compression stockings, whereas newly introduced anesthesia-led components showed the lowest uptake. Considering the importance of multidisciplinary engagement to help ensure appropriate ERAS adoption, it seems important to help integrate targeted educational initiatives to establish standardized intraoperative protocols particularly in centers at the beginning of their ERAS implementation journey.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of our study is its prospective, multi-institutional design that captures the real-world implementation of ERAS protocols across gynecologic oncology centers, thereby enhancing the potential external validity and representativeness of reported findings. Its pragmatic design, conducted under routine clinical conditions helps capture the adoption of ERAS principles in clinical practice, across different hospital settings, staffing structures, and resource levels, therefore, avoiding the potential constraints of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) which overcomes these barriers through its randomization process. This way it can provide meaningful insights into real-world barriers to adherence. Another significant strength of our study is its preregistration in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06655506) that reinforces its methodological transparency by ensuring adherence to a predefined analytic plan; thus, avoiding selective reporting. Moreover, it should be noted that all data were collected using standardized electronic REDCap forms, ensuring procedural consistency, together reducing information bias. The design is anchored in a contemporary, guideline-based ERAS framework following the 2021 ERAS Society recommendations, ensuring alignment with international standards; thus, avoiding selection of arbitrary ERAS components. Multivariable logistic regression allowed us to further determine independent predictors of adherence, specifically surgical complexity and ECOG performance status which were confirmed by the inclusion of alluvial plots which offered an intuitive visualization of interactions among patient factors, surgical complexity, and adherence categories.

On the other hand, it should be noted that the pragmatic nature of the study, also means that interventions were not standardized to the degree achievable in an RCT, therefore, being prone to the actual variability in institutional workflows, resources, and team experience. Additionally, many participating centers were in the early phases of ERAS adoption, which likely contributed to the significant inter-institutional variability observed, which seems to be more pronounced among anesthesiology-driven components which were less integrated in our series. Moreover, despite the use of two distinct groups that were based on a predefined adherence threshold (≥70% vs. <70%), the observational nature of the study still prevents causal inference. Although the multivariate analysis identified factors potentially associated with optimal ERAS incorporation, the associations identified should be interpreted as descriptive and hypothesis-generating rather than causal.

Conclusions and Implications

The present multicenter study highlights the difficulties of achieving consistent ERAS adherence across gynecologic oncology centers, particularly during the early phases of protocol adoption. The marked variability observed between high- and low-volume centers suggests that implementation success depends on structured protocols, ongoing team training, and the establishment of clear institutional workflows. The strong influence of surgical complexity and patient performance status on adherence indicates that further familiarization is needed to help physicians constituting the multidisciplinary team confidently apply the ERAS principles in complex scenarios, as current evidence suggests that this is feasible and safe. Future research should focus on identifying practical strategies that can support the adoption of ERAS in settings with limited experience, as well as exploring barriers to complex cases. The completion of the full ERGO cohort will allow assessment of temporal improvements in adherence and facilitate evaluation of the relationship between compliance and postoperative outcomes. Additional future stepped-wedge designed cohorts could further clarify causal pathways, something that was not possible in our study, to help guide optimization of instructional procedures and increase the acceptability of ERAS programs in gynecologic oncology.

Authors contributions

Vasilios Pergialiotis conceived the study, supervised protocol development, contributed to data interpretation, and drafted and revised the manuscript. Dimitrios Haidopoulos contributed to study conception, clinical oversight, and critical revision of the manuscript. Alexandros Daponte coordinated data collection at his center, contributed to methodology refinement, and reviewed the manuscript. Dimitrios Tsolakidis coordinated data collection at his center, contributed to methodology refinement, and reviewed the manuscript. Stamatios Petousis coordinated data collection at his center, contributed to methodology refinement, and reviewed the manuscript. Ioannis Kalogiannidis coordinated data collection at his center, contributed to methodology refinement, and reviewed the manuscript. Dimitrios Efthimios Vlachos contributed to data management, statistical accuracy verification, and manuscript review. Vasilios Lygizos assisted with data acquisition and contributed to drafting sections of the Methods and Results. Maria Fanaki coordinated REDCap data entry, performed data validation, and assisted in manuscript preparation. George Delinasios contributed to data collection and supported manuscript editing. Panagiotis Tzitzis participated in patient recruitment and contributed to data accuracy checks. Philipos Ntailianas participated in patient recruitment and contributed to data accuracy checks. Vasilios Theodoulidis assisted with clinical data entry and revision of the manuscript. Georgia Margioula Siarkou contributed to data collection, patient follow-up, and manuscript review. Nikoletta Daponte assisted in data verification, literature review, and manuscript editing. Nikolaos Thomakos supervised the clinical research activities, contributed to study design and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Clinicaltrials registration number

NCT06655506.

Conflicts of Interest

None for all authors.

References

- Fearon, K.C.; Ljungqvist, O.; Von Meyenfeldt, M.; Revhaug, A.; Dejong, C.H.; Lassen, K.; et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr 2005, 24, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.J.; Kim, M.-S.; Lee, Y.-Y. The implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery protocols in ovarian malignancy surgery. Gland Surgery 2020, 10, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, G.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.; Kalogera, E.; Glaser, G.; Altman, A.; Meyer, L.A.; et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations-2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2019, 29, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, F. Physiologic considerations of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programs: implications of the stress response. Can J Anaesth 2015, 62, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ore, A.S.; Shear, M.A.; Liu, F.W.; Dalrymple, J.L.; Awtrey, C.S.; Garrett, L.; et al. Adoption of enhanced recovery after laparotomy in gynecologic oncology. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2020, 30, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, K.M.; Smith, C.; Ibadin, S.; Thomas, A.; Ganshorn, H.; Bakunda, L.; et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Guidelines and Hospital Length of Stay, Readmission, Complications, and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2417310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margioula-Siarkou, C.; Almperis, A.; Almperi, E.A.; Margioula-Siarkou, G.; Flindris, S.; Daponte, N.; et al. Prophylactic and Therapeutic Usage of Drains in Gynecologic Oncology Procedures: A Comprehensive Review. J Pers Med 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, B.; Jurt, J.; Grass, F.; Hübner, M.; Demartines, N.; Mathevet, P.; et al. Compliance with enhanced recovery after surgery program in gynecology: are all items of equal importance? International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2019, 29, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasilainen, S.; Tiainen, T.; Pakarinen, M.; Bumblyte, V.; Scheinin, T.; Schramko, A. ERAS failure and major complications in elective colon surgery: Common risk factors. Surgery in Practice and Science 2022, 10, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, A.S.; Welsch, T.; Brodersen, F.; Auinger, J.; Moll-Khosrawi, P.; Goetz, M.R.; et al. Impact of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol Compliance on Outcome After Pancreatic Surgery: Results From a Certified ERAS Center. Annals of Surgery Open 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljungqvist, O.; Scott, M.; Fearon, K.C. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surgery 2017, 152, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, L.M.; Sheppard, C.E.; Wasylak, T.; Gilmour, L.E.; Ljungqvist, O.; Basualdo-Hammond, C.; et al. Implementation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: a strategy to transform surgical care across a health system. Implement Sci 2017, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millan, M. Enhanced recovery after surgery in elderly and high-risk patients. Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Lv, F.; Min, S.; Wu, G.; Jin, J.; Gong, Y.; et al. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery protocol compliance on patients' outcome in benign hysterectomy and establishment of a predictive nomogram model. BMC Anesthesiol 2021, 21, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijk, L.; Udumyan, R.; Pache, B.; Altman, A.D.; Williams, L.L.; Elias, K.M.; et al. International validation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society guidelines on enhanced recovery for gynecologic surgery. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2019, 221, 237.e231–237.e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandraklakis, A.; Liakou, C.; La Russa, M.; Ochoa-Ferraro, R.; Stearns, A.; Burbos, N. Implementation of enhanced recovery protocols in patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for metastatic ovarian cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. A feasibility study. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2024, 56, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesta, M.D.; Lasala, J.; Mena, G.; Rodriguez-Restrepo, A.; Salvo, G.; Pitcher, B.; et al. Impact of compliance with an enhanced recovery after surgery pathway on patient outcomes in open gynecologic surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2019, 29, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisch, S.P.; Wells, T.; Gramlich, L.; Faris, P.; Wang, X.; Tran, D.T.; et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in gynecologic oncology: System-wide implementation and audit leads to improved value and patient outcomes. Gynecol Oncol 2018, 151, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, J.; Zorrilla-Vaca, A.; Meyer, L.A.; Mena, G.; Lasala, J.; Iniesta, M.D.; et al. Patient outcomes and adherence to an enhanced recovery pathway for open gynecologic surgery: a 6-year single-center experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2022, 32, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Hidalgo, N.R.; Pletnev, A.; Razumova, Z.; Bizzarri, N.; Selcuk, I.; Theofanakis, C.; et al. European Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) gynecologic oncology survey: Status of ERAS protocol implementation across Europe. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2023, 160, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, T.; Chen, Y.; Ren, L.; Lv, F.; Hu, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Adherence to the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol and its influencing factors among patients in Southwestern China: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2025, 12, 1660083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.W.; Fields, A.C.; Shabat, G.; Bleday, R.; Goldberg, J.E.; Irani, J.; et al. Cytoreductive Surgery and HIPEC in an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Program: A Feasibility Study. J Surg Res 2020, 247, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Iglesias, J.L.; Carbonell-Socias, M.; Pérez-Benavente, M.A.; Monreal Clua, S.; Manrique-Muñoz, S.; García Gorriz, M.; et al. PROFAST: A randomised trial implementing enhanced recovery after surgery for highcomplexity advanced ovarian cancer surgery. Eur J Cancer 2020, 136, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).