Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search

3. Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound in Pancreatic Metastases

3.1. Population Characteristics

3.2. Primary Tumors

3.3. Size, Localization and Focality

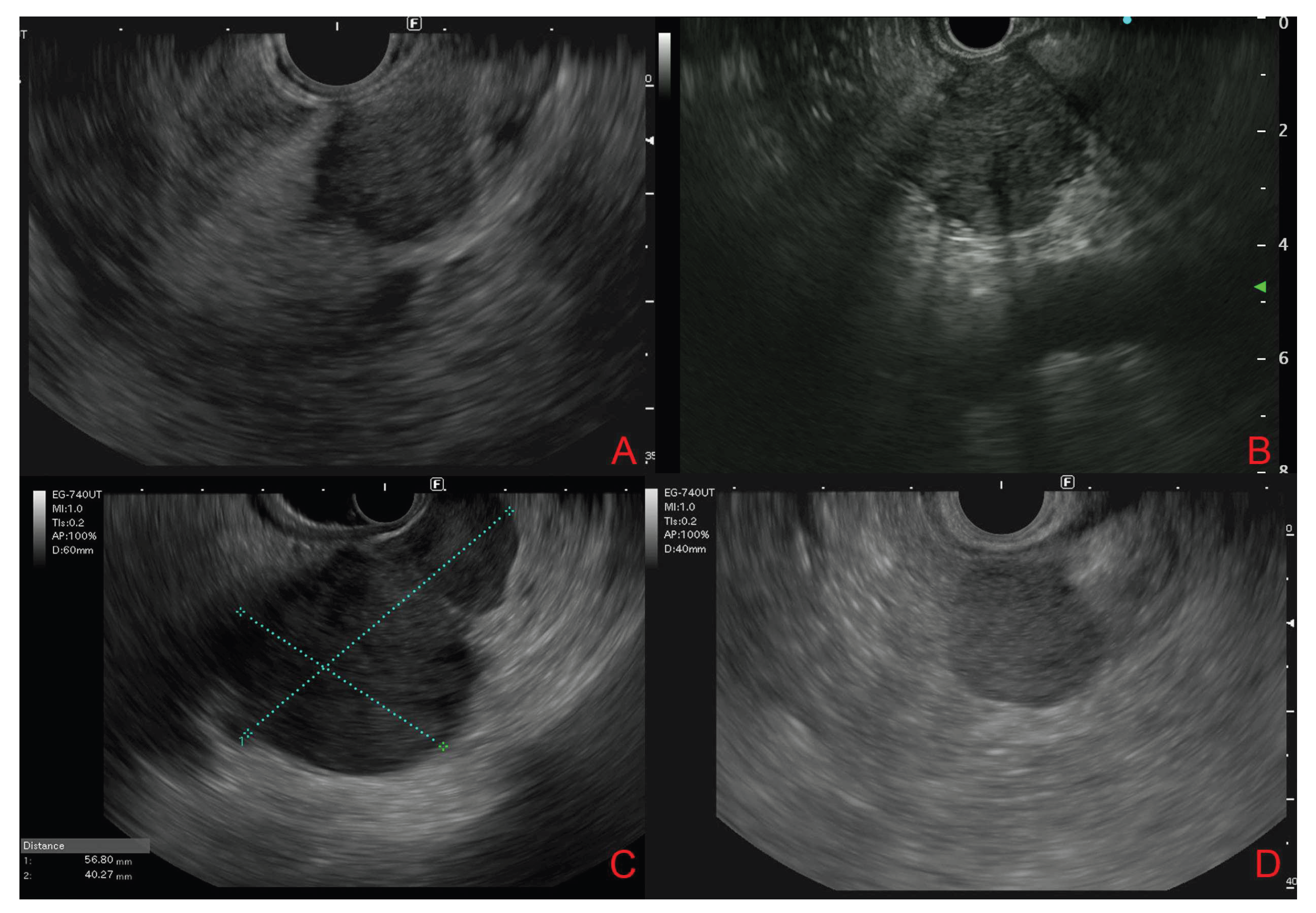

3.4. Endoscopic Ultrasound Morphological Features

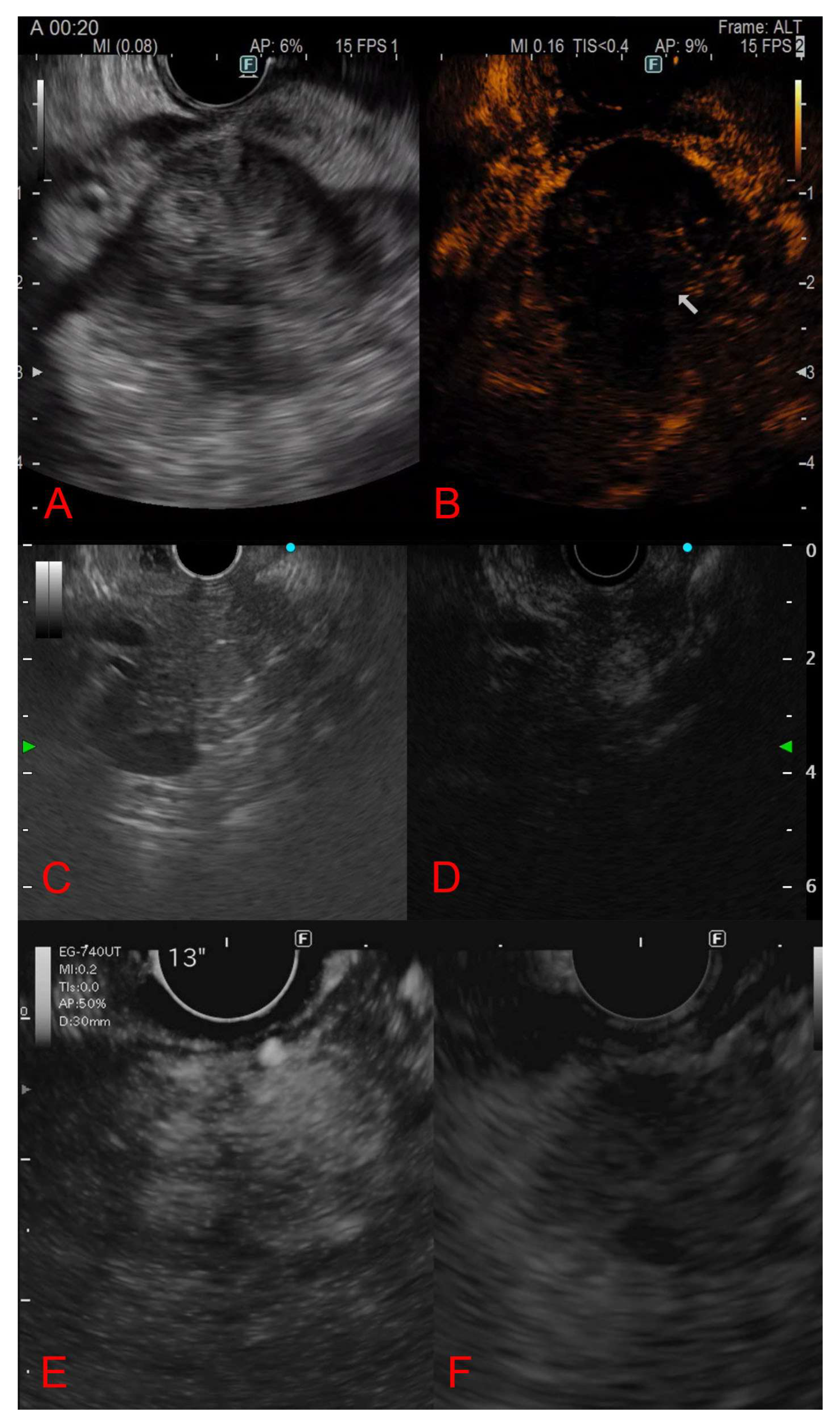

3.5. Contrast-Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasound Features

3.6. Diagnostic Yield and Final Diagnostic Method

3.7. Treatment and Outcomes

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PM | Metastases to the pancreas |

| EUS | Endoscopic ultrasound |

| PDAC | Primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| EUS-TA | EUS-guided tissue acquisition |

| FNA | Fine-needle aspiration |

| FNB | Fine-needle biopsy |

| CH-EUS | Contrast-enhanced EUS |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| RCC | Renal cell carcinoma |

| MHZ | Marginal hypoechoic zone |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- Adsay, N. V.; Andea, A.; Basturk, O.; Kilinc, N.; Nassar, H.; Cheng, JeanetteD. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas: An Analysis of a Surgical and Autopsy Database and Review of the Literature. Virchows Archiv 2004, 444 (6). [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, E.; Shimizu, M.; Itoh, T.; Manabe, T. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas: Clinicopathological Study of 103 Autopsy Cases of Japanese Patients. Pathol Int 2001, 51(9), 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, O.; Green, L.; Reddy, V.; Kluskens, L.; Bitterman, P.; Attal, H.; Prinz, R.; Gattuso, P. Pancreatic Masses: A Multi-Institutional Study of 364 Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsies with Histopathologic Correlation. Diagn Cytopathol 1998, 19(6), 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritscher-Ravens, A.; Sriram, P. V. J.; Krause, C.; Atay, Z.; Jaeckle, S.; Thonke, F.; Brand, B.; Bohnacker, S.; Soehendra, N. Detection of Pancreatic Metastases by EUS-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc 2001, 53(1), 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, H.; Stelow, E. B.; Stanley, M. W.; Mallery, S.; Lai, R.; Bardales, R. H. Diagnosis of Nonprimary Pancreatic Neoplasms by Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine-needle Aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol 2004, 31(5), 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantopoulou, C.; Kolliakou, E.; Karoumpalis, I.; Yarmenitis, S.; Dervenis, C. Metastatic Disease to the Pancreas: An Imaging Challenge. Insights Imaging 2012, 3(2), 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohm, W. D.; Phillip, J.; Hagenmüller, F.; Classen, M. Ultrasonic Tomography by Means of an Ultrasonic Fiberendoscope. Endoscopy 1980, 12(05), 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilmann, P.; Jacobsen, G. K.; Henriksen, F. W.; Hancke, S. Endoscopic Ultrasonography with Guided Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy in Pancreatic Disease. Gastrointest Endosc 1992, 38(2), 172–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiersema, M. J.; Hawes, R. H.; Tao, L.-C.; Wiersema, L. M.; Kopecky, K. K.; Rex, D. K.; Kumar, S.; Lehman, G. A. Endoscopic Ultrasonography as an Adjunct to Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology of the Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Tract. Gastrointest Endosc 1992, 38(1), 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, L.; Borotto, E.; Cellier, C.; Roseau, G.; Chaussade, S.; Couturier, D.; Paolaggi, J. A. Endosonographic Features of Pancreatic Metastases. Gastrointest Endosc 1996, 44(4), 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouw, R. E.; Barret, M.; Biermann, K.; Bisschops, R.; Czakó, L.; Gecse, K. B.; de Hertogh, G.; Hucl, T.; Iacucci, M.; Jansen, M.; Rutter, M.; Savarino, E.; Spaander, M. C. W.; Schmidt, P. T.; Vieth, M.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; van Hooft, J. E. Endoscopic Tissue Sampling – Part 1: Upper Gastrointestinal and Hepatopancreatobiliary Tracts. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2021, 53 (11), 1174–1188. [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.; Jowell, P.; LeBlanc, J.; McHenry, L.; McGreevy, K.; Cramer, H.; Volmar, K.; Sherman, S.; Gress, F. EUS-Guided FNA of Pancreatic Metastases: A Multicenter Experience. Gastrointest Endosc 2005, 61(6), 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A. L.; Odronic, S. I.; Springer, B. S.; Reynolds, J. P. Solid Tumor Metastases to the Pancreas Diagnosed by FNA: A Single-institution Experience and Review of the Literature. Cancer Cytopathol 2015, 123(6), 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betés, M.; González Vázquez, S.; Bojórquez, A.; Lozano, M. D.; Echeveste, J. I.; García Albarrán, L.; Muñoz Navas, M.; Súbtil, J. C. Metastatic Tumors in the Pancreas: The Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration. Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas 2019, 111. [CrossRef]

- Aversano, A.; Lissandrini, L.; Macor, D.; Carbone, M.; Cassarano, S.; Marino, M.; Giuffrè, M.; De Pellegrin, A.; Terrosu, G.; Berretti, D. The Role of Endoscopic Ultrasonography (EUS) in Metastatic Tumors in the Pancreas: 10 Years of Experience from a Single High-Volume Center. Diagnostics 2024, 14(12), 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaccini, M.; Conti Bellocchi, M. C.; Mangiavillano, B.; Fantin, A.; Rahal, D.; Manfrin, E.; Gavazzi, F.; Bozzarelli, S.; Crinò, S. F.; Terrin, M.; Di Leo, M.; Bonifacio, C.; Facciorusso, A.; Realdon, S.; Cristofori, C.; Auriemma, F.; Fugazza, A.; Frulloni, L.; Hassan, C.; Repici, A.; Carrara, S. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas: A Multicenter Analysis of Clinicopathological and Endosonographic Features. J Clin Med 2023, 12(8), 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, S.; Koizumi, K.; Shionoya, K.; Jinushi, R.; Makazu, M.; Nishino, T.; Kimura, K.; Sumida, C.; Kubota, J.; Ichita, C.; Sasaki, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Kako, M.; Haruki, U. Comprehensive Review on Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Tissue Acquisition Techniques for Solid Pancreatic Tumor. World J Gastroenterol 2023, 29(12), 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, M. J.; McPhail, M. J. W.; Possamai, L.; Dhar, A.; Vlavianos, P.; Monahan, K. J. EUS-Guided FNA for Diagnosis of Solid Pancreatic Neoplasms: A Meta-Analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2012, 75(2), 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusaroli, P.; Napoleon, B.; Gincul, R.; Lefort, C.; Palazzo, L.; Palazzo, M.; Kitano, M.; Minaga, K.; Caletti, G.; Lisotti, A. The Clinical Impact of Ultrasound Contrast Agents in EUS: A Systematic Review According to the Levels of Evidence. Gastrointest Endosc 2016, 84 (4), 587-596.e10. [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, C.; Bolboaca, S. D.; Rusu, I.; Pojoga, C.; Seicean, R.; Mosteanu, O.; Sparchez, Z.; Seicean, A. Contrast Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Metastases. Med Ultrason 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitano, M.; Kamata, K.; Imai, H.; Miyata, T.; Yasukawa, S.; Yanagisawa, A.; Kudo, M. Contrast-enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasonography for Pancreatobiliary Diseases. Digestive Endoscopy 2015, 27 (S1), 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, A.; Mitry, E.; Hammel, P.; Sauvanet, A.; Nassif, T.; Palazzo, L.; Malka, D.; Delchier, J.-C.; Buffet, C.; Chaussade, S.; Aparicio, T.; Lasser, P.; Rougier, P.; Lesur, G. Pancreatic Metastases: A Multicentric Study of 22 Patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2004, 28(10), 872–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarin, R. Pancreatic Metastases from Renal Cell Carcinoma: The State of the Art. World J Gastroenterol 2011, 17(43), 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Edil, B. H.; Cameron, J. L.; Pawlik, T. M.; Herman, J. M.; Gilson, M. M.; Campbell, K. A.; Schulick, R. D.; Ahuja, N.; Wolfgang, C. L. Pancreatic Resection of Isolated Metastases from Nonpancreatic Primary Cancers. Ann Surg Oncol 2008, 15(11), 3199–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, I. I.; LeBlanc, J. K.; Sherman, S.; Al-Haddad, M. A.; Cote, G. A.; McHenry, L.; DeWitt, J. M. Endoscopic Ultrasound–Guided Biopsy of Pancreatic Metastases. Pancreas 2013, 42(3), 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, L.; Si, Q.; Caraway, N.; Mody, D.; Staerkel, G.; Sneige, N. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas Diagnosed by Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine-needle Aspiration: A 10-year Experience. Diagn Cytopathol 2014, 42(9), 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, M.; Amin, K.; Mettler, T.; Miller, L. K.; Mallery, S.; Stewart, J. Pancreatic Involvement by Metastasizing Neoplasms as Determined by Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine Needle Aspiration: A Clinicopathologic Characterization. Diagn Cytopathol 2017, 45(5), 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, S. L. T.; Yugawa, D.; Chang, K. H. F.; Ena, B.; Tauchi-Nishi, P. S. Metastatic Neoplasms to the Pancreas Diagnosed by Fine-needle Aspiration/Biopsy Cytology: A 15-year Retrospective Analysis. Diagn Cytopathol 2017, 45(9), 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Shen, R.; Tonkovich, D.; Li, Z. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration Diagnosis of Secondary Tumors Involving Pancreas: An Institution’s Experience. J Am Soc Cytopathol 2018, 7(5), 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiq, M.; Bhutani, M. S.; Ross, W. A.; Raju, G. S.; Gong, Y.; Tamm, E. P.; Javle, M.; Wang, X.; Lee, J. H. Role of Endoscopic Ultrasonography in Evaluation of Metastatic Lesions to the Pancreas. Pancreas 2013, 42(3), 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijioka, S.; Matsuo, K.; Mizuno, N.; Hara, K.; Mekky, M. A.; Vikram, B.; Hosoda, W.; Yatabe, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Kondo, S.; Tajika, M.; Niwa, Y.; Tamada, K.; Yamao, K. Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound and Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration in Diagnosing Metastasis to the Pancreas: A Tertiary Center Experience. Pancreatology 2011, 11(4), 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Lee, Y.; Rodriguez, T.; Lee, J.; Saif, M. W. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas: A Case Series. Anticancer Res 2012, 32(4), 1449–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, M. A.; Bohy, K.; Singal, A.; Xie, C.; Patel, B.; Nelson, M. E.; Bleeker, J.; Askeland, R.; Abdullah, A.; Aloreidi, K.; Atiq, M. Metastatic Tumors to the Pancreas: Balancing Clinical Impression with Cytology Findings. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2022, 26(1), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Amed, M.; Reid, M. D.; Xue, Y. Secondary Pancreatic Tumors in Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy: Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Morphological Diagnostic Challenges. Hum Pathol 2025, 161, 105869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béchade, D.; Palazzo, L.; Fabre, M.; Algayres, J.-P. EUS-Guided FNA of Pancreatic Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc 2003, 58(5), 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioakim, K. J.; Sydney, G. I.; Michaelides, C.; Sepsa, A.; Psarras, K.; Tsiotos, G. G.; Salla, C.; Nikas, I. P. Evaluation of Metastases to the Pancreas with Fine Needle Aspiration: A Case Series from a Single Centre with Review of the Literature. Cytopathology 2020, 31(2), 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaroli, P.; D’Ercole, M. C.; De Giorgio, R.; Serrani, M.; Caletti, G. Contrast Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasonography in the Characterization of Pancreatic Metastases (With Video). Pancreas 2014, 43(4), 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, A. K.; Ustun, B.; Aslanian, H. R.; Ge, X.; Chhieng, D.; Cai, G. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration Diagnosis of Secondary Tumors Involving the Pancreas: An Institution’s Experience. Cytojournal 2016, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardengh, J. C.; Lopes, C. V.; Kemp, R.; Venco, F.; de Lima-Filho, E. R.; dos Santos, J. S. Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration in the Suspicion of Pancreatic Metastases. BMC Gastroenterol 2013, 13(1), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layfield, L. J.; Hirschowitz, S. L.; Adler, D. G. Metastatic Disease to the Pancreas Documented by Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Fine-needle Aspiration: A Seven-year Experience. Diagn Cytopathol 2012, 40(3), 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellner, F.; Thalhammer, S.; Klimpfinger, M. Tumour Evolution and Seed and Soil Mechanism in Pancreatic Metastases of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(6), 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperti, C.; Pozza, G.; Brazzale, A. R.; Buratin, A.; Moletta, L.; Beltrame, V.; Valmasoni, M. Metastatic Tumors to the Pancreas: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Minerva Chir 2016, 71(5), 337–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Riet, P. A.; Erler, N. S.; Bruno, M. J.; Cahen, D. L. Comparison of Fine-Needle Aspiration and Fine-Needle Biopsy Devices for Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Sampling of Solid Lesions: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endoscopy 2021, 53(04), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, P.; Nassar, A.; Gomez, V.; Raimondo, M.; Woodward, T. A.; Crook, J. E.; Fares, N. S.; Wallace, M. B. Comparison of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy versus Fine-Needle Aspiration for Genomic Profiling and DNA Yield in Pancreatic Cancer: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Endoscopy 2021, 53(04), 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, Y.; Kamata, K.; Kudo, M. Contrast-Enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Puncture for the Patients with Pancreatic Masses. Diagnostics 2023, 13(6), 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itonaga, M.; Kitano, M.; Kojima, F.; Hatamaru, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Tamura, T.; Nuta, J.; Kawaji, Y.; Shimokawa, T.; Tanioka, K.; Murata, S. The Usefulness of EUS-FNA with Contrast-enhanced Harmonic Imaging of Solid Pancreatic Lesions: A Prospective Study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 35(12), 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacelli, M.; Lauri, G.; Tabacelia, D.; Tieranu, C.G.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; Săftoiu, A. Integrating artificial intelligence with endoscopic ultrasound in the early detection of bilio-pancreatic lesions: Current advances and future prospects. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2025 Feb;74:101975. [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, T.; Hara, K.; Mizuno, N.; Haba, S.; Okuno, N.; Kuraishi, Y.; Fumihara, D.; Yanaidani, T.; Ishikawa, S.; Yasuda, T.; et al. Artificial intelligence using deep learning analysis of endoscopic ultrasonography images for the differential diagnosis of pancreatic masses. Endoscopy. 2023 Feb;55(2):140-149. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Study design | Country | Study type | Enrollment period | Patients, n | Mean age (range), years | Sex male, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palazzo et al. [10] | Retrospective | France | Monocentric | 1989-1993 | 7 | 57 (38-77) | 42.9% |

| Fritscher-Ravens et al. [4] | Retrospective | Germany | Monocentric | - | 12 | 61 (34-78) | 33.3% |

| Bechade et al. [35] | Retrospective | France | Monocentric | 1999-2002 | 11 | 65.5 (56-82) | 72.7% |

| Mesa et al. [5] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 2000-2002 | 11 | - | - |

| Moussa et al.[22] | Retrospective | France | Multicentric |

1990-2000 | 22 | 61 (35-76) | 45.5% |

| DeWitt et al.[12] | Retrospective | USA | Multicentric | 1998-2004 | 24 | 60 (33-83) | 62.5% |

| Layfield et al. [40] | Retrospective | USA | Multicentric | 2002-2010 | 17 | 60.9 (15-80) | 88.2% |

| Hijoka et al. [31] | Retrospective | Japan | Monocentric | 1997-2010 | 28 | 59.8 (20-72) | 46.4% |

| Pan et al. [32] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 2010-2012 | 6 | 66.5 (59-73) | 83.3% |

| Ardengh et al. [39] | Retrospective | Brazil | Multicentric | 1997-2010 | 37 | 60.3 (26–84) | 70.3% |

| El Hajj et al. [25] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 1998-2010 | 49 | 63 (30-83) | 46.9% |

| Atiq et al. [30] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 2005-2009 | 23 | 63 | 43.5% |

| Fusaroli et al.[37] | Retrospective | Italy | Monocentric | 2008-2011 | 11 | 66 (42- 82) | 27.3% |

| Waters et al. [26] | Retrospective | USA | Multicentric | 2002-2012 | 66 | 63 (40-89) | 57.6% |

| Smith et al. [13] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 2000-2014 | 22 | 71 (59-83) | 59.1% |

| Alomari et al. [38] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 2005-2012 | 31 | 66 (49-86) | 61.3% |

| Raymond et al. [28] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 2000-2014 | 16 | (43-84) | 68.8% |

| Sekulic et al. [27] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 2006-2016 | 25 | 64 (53-71) (median, IQR) | 52% |

| Hou et al. [29] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 2008-2016 | 30 | 61.2 (25-82) | 60% |

| Betes et al. [14] | Retrospective | Spain | Monocentric | 2004-2016 | 44 | 58 ± 11.7 | 63.6% |

| Ioakim et al. [36] | Retrospective | Greece | Monocentric | 2013-2018 | 7 | 66.9 (56-76) | 71.4% |

| Abdallah et al. [33] | Retrospective | USA | Monocentric | 2011-2017 | 8 | 68.38 ± 10.56 | 50% |

| Teodorescu et al. [20] | Retrospective | Romania | Monocentric | 2012-2020 | 20 | 62 (56–66)(median, IQR) | 50% |

| Spadaccini et al. [16] | Retrospective | Italy | Multicentric | 2010-2021 | 116 | 66.7 (26-86) | 59.5% |

| Aversano et al. [15] | Retrospective | Italy | Monocentric | 2013-2023 | 41 | 71.53 (30-85) | 61% |

| Cui et al. [34] | Retrospective | USA | Multicentric | 2015-2023 | 62 | 66 (42-87) | 46.8% |

| Reference | Lesions, n | Primaries (Kidney/Lung/Colon/Breast/ other) |

Mean lesion size (range), mm |

Location (head (uncinate, neck)/body/ tail/multiple) |

Focality (monofocal/multifocal) |

EUS morphology | CH-EUS pattern | Final diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palazzo et al. [10] | 16 | 4/0/0/0/3 | 40 (15-60) | 5/0/1/0 | 6/1 | Isoechoic moderately hypoechoic, homogeneous, rounded and well delineated and associated with peripheral intensification or no attenuation. Hypervascular. |

- | Pre-FNA era, focus on morphology (6 surgery, 1 CT biopsy) |

| Fritscher-Ravens et al. [4] | 12 | 3/1/1/2/4 | 28 (18-40) |

10/2/0/0 | - | Hypoechoic (2); Hypoechoic and inhomogeneus (10) |

- | EUS-FNA |

| Bechade et al. [35] | 29 | 11/0/0/0/0 | - | 5/1/0/5 | 5/6 | Rounded, solid, well-defined, homogeneous, hypoechoic, or isoechoic lesions, with peripheral enhancement of the US beam |

- | EUS-FNA (9/11) |

| Mesa et al. [5] | 11 | 1/4/1/2/3 | - | 6/3/1/1 | - | - | - | |

| Moussa et al.[22] | 31 | 10/4/4/2/2 | - | - | 14/3 | Hypoechogenic (9), well-limited borders (6), posterior enhancement (3), hyperechogenic aspect (1), homogeneous aspect (1) |

- | EUS-FNA (N = 6), CT-guided biopsy (N = 2), ultrasound-guided biopsy (N = 3), duodenoscopy (N = 3) |

| DeWitt et al.[12] | 29 | 10/4/2/0/8 | 36,13 (16-70) |

15/5/3/1 | 22/2 | Borders: poorly defined in 13 (54%); well defined in 11 (46%). Hypoechoic 20 (83%); 1 metastatic RCC hyperechoic; 1 anechoic; 2 mixed hypoechoic/ anechoic 2 lesions. |

- | EUS-FNA |

| Layfield et al. [40] | 17 | 8/2/0/0/9 | - | 6/4/0/4 | - | - | - | EUS-FNA |

| Hijoka et al. [31] | 38 | 7/6/1/2/12 | 34.4 (13-90) | 9/13/3/3 | 23/5 | Regular borders in 18 (64.2%), clear boundary in 26 (92.8%), homogeneous internal echoic pattern in 14 (50.0%). Cystic components in 8 (28.5%), MHZ in 10 (35.7%); calcifications in 3 (10.7%). Distal MPD dilation in 10 (35.7%), distal parenchymal atrophy in 3 (10.7%). |

-- | 22 (78,5%) EUS-FNA; 12 (42.8%) surgical resection |

| Pan et al. [32] | 6 | 2/2/1/1/0 | - | 1/3/1/1 | 5/1 | - | - | - |

| Ardengh et al. [39] | 37 | 5/6/4/3/17 | 42 (12-127) | 22/9/4/0/2 | 34/3 | Hypoechoic (34), with well- defined borders (23) and heterogeneous (22) |

- | EUS-FNA (Final diagnosis in 94% of cases) |

| El Hajj et al. [25] | 72 | 21/8/4/3/13 | 34 (4-80) |

34/8/7/0 | 38/11 | Hypoechoic 39 (80%); mixed hypoechoic/anechoic 7 (14%), hyperechoic 2 (4%); anechoic in 1 (2%). Regular borders in 27 (55%), irregular in 22 (45%). |

- | EUS-FNA |

| Atiq et al. [30] | 23 | 4/4/4/0/11 | 39.1 (16-90) | 10/8/4/1 |

18/5 | Solitary pancreatic lesion in 18 (78.3%). Hypoechoic in 16 (69.6%), anechoic in 2 (8.7%), mixed echogenicity in 5 (21.7%). |

- | 21 EUS-FNA; 1 CT FNA; 1 clinical course |

| Fusaroli et al.[37] | 11 | 3/0/2/2/4 | 29.7 (10-50) |

2/8/0/0/1 | 11/0 | Hypoechoic with homogeneous in echotexture (10). Regular margins (9). Irregular margins in breast cancer metastasis. |

Hypoenhancing with heterogeneous pattern 4; Hypoenhancing with homogeneous pattern 2; Hyperenhancing with homogeneous pattern 4 (RCC); Isoenhancing with heterogeneous pattern 1. |

EUS-FNA and surgical |

| Waters et al. [26] | 66 | 27/9/5/6/19 | - |

30/15/17/1 | 65/1 | - | - | All EUS-FNA |

| Smith et al. [13] | 22 | 14/1/2/0/5 | 37 (15-65) | - | 16/6 | - | - | All EUS-FNA |

| Alomari et al. [38] | 31 | 8/7/2/2/12 | 43 (11- 100) |

13/3/2/13 | 17/14 | - | - | EUS -FNA (Final diagnoses in 94% of cases) |

| Raymond et al. [28] | 16 | 3/6/2/0/5 | 42 (12- 109) | 7/5/4/0 | 15/1 | - | - | EUS FNA 8; CT FNA 3; CT CNB 5; |

| Sekulic et al. [27] | 25 | 10/2/4/1/8 | 15 (9.5- 26) (median, IQR) | 17/11/9/7 | 18/7 | Hypoechoic, heterogeneous, and with variably defined borders |

- | EUS-FNA |

| Hou et al. [29] | 30 | 11/5/2/2/10 | - | 12/7/8/2 | - | - | - | EUS-FNA (93.3% accuracy) |

| Betes et al. [14] | 44 | 12/10/5/1/16 | 28.63 ± 19.4 | 22/8/7/7 | 34/10 | - | - | EUS-FNA |

| Ioakim et al. [36] | 10 | 3/1/1/0/2 | - | - | - | All lesions, except one that showed a mixed solid and cystic morphology, appeared solid. |

- | EUS-FNA |

| Abdallah et al. [33] | 12 | 5/1/0/1/1 | 31.88 ± 25.85 | 3/2/2/0 | 6/2 | - | - | EUS-FNA |

| Teodorescu et al. [20] | 20 | 6/5/3/1/5 |

30 (22–36) (median, IQR) |

12/2/6/0 | 14/6 | Hypoechoic and hypervascularized in 11 (55%) |

Arterial hyperenhancement in 11 (55%); hypoenhancement in 9 |

EUS-FNA |

| Spadaccini et al. [16] | 205 | 75/7/9/7/18 | 25.4 ± 15.2 | 137/50/49/0 | 59/57 | Hypoechoic (95), hypervascular (60), with a heterogeneous pattern (54), well-defined borders (52) |

- | 82 EUS-FNB; 12 EUS-FNA; 15 surgery. |

| Aversano et al. [15] | 41 | 18/4/4/2/13 | 30 (IQR 27) | 17/7/5/12 | 26/15 | Hypoechoic (97.56%), oval-shaped (54.66%), well-defined borders (60.98%), predominantly hypervascular. |

- | 35 EUS-FNA/B; 2 surgery; 3 clinical history and appearances |

| Cui et al. [34] | 62 | 11/9/2/3/37 | 34 (6-130) | 26/13/13/10 | 46/16 | - | - | EUS-FNB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).