Submitted:

30 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Survey Design:

Survey Details

Standards Operating Protocol (SOP) & Guidelines:

- Acute Aortic Syndrome (AAS): This term encompasses aortic dissection, penetrating aortic ulcer (PAU), and intramural hematoma (IMH).[16]

- Type B Aortic Dissection (TBAD) & blood pressure management: TBAD is defined as a dissection occurring in the aorta beyond the left subclavian artery, without involving the ascending aorta. Labetalol is the recommended first line antihypertensive for management of hypertension in TBAD.[16]

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussions

Limitations:

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments of Survery Contributors

Competing interest

Patient consent for publication

Ethics Approval

Provenance and peer review

Data Availability

References

- Olsson C, Thelin S, Stahle E, Ekbom A, Granath F. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: increasing prevalence and improved outcomes reported in a nationwide population-based study of more than 14,000 cases from 1987 to 2002. Circulation. Dec 12 2006;114(24):2611-8. [CrossRef]

- Howard DP, Banerjee A, Fairhead JF, et al. Population-Based Study of Incidence, Risk Factors, Outcome, and Prognosis of Ischemic Peripheral Arterial Events: Implications for Prevention. Circulation. Nov 10 2015;132(19):1805-15. [CrossRef]

- Zhan S, Hong S, Shan-Shan L, et al. Misdiagnosis of aortic dissection: experience of 361 patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). Apr 2012;14(4):256-60. [CrossRef]

- Hansen MS, Nogareda GJ, Hutchison SJ. Frequency of and inappropriate treatment of misdiagnosis of acute aortic dissection. Am J Cardiol. Mar 15 2007;99(6):852-6. [CrossRef]

- Klompas M. Does this patient have an acute thoracic aortic dissection? JAMA. May 1 2002;287(17):2262-72. [CrossRef]

- Nienaber CA, Clough RE. Management of acute aortic dissection. Lancet. Feb 28 2015;385(9970):800-11. [CrossRef]

- Pherwani A. New data highlight rising incidence of aortic dissection in England. VascularNews. Accessed 25/04/2024, https://vascularnews.com/new-data-highlight-rising-incidence-of-aortic-dissection-in-england/#:~:text=New%20data%20highlight%20rising%20incidence%20of%20aortic%20dissection%20in%20England,-25th%20April%202024&text=“The%20incidence%20of%20acute%20aortic,April%2C%20London%2C%20UK).

- Asha SE, Miers JW. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of D-dimer as a Rule-out Test for Suspected Acute Aortic Dissection. Ann Emerg Med. Oct 2015;66(4):368-78. [CrossRef]

- Nazerian P, Morello F, Vanni S, et al. Combined use of aortic dissection detection risk score and D-dimer in the diagnostic workup of suspected acute aortic dissection. Int J Cardiol. Jul 15 2014;175(1):78-82. [CrossRef]

- American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Thoracic Aortic D, Diercks DB, Promes SB, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients with suspected acute nontraumatic thoracic aortic dissection. Ann Emerg Med. Jan 2015;65(1):32-42 e12. [CrossRef]

- Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. Nov 1 2014;35(41):2873-926. [CrossRef]

- Nazerian P, Giachino F, Vanni S, et al. Diagnostic performance of the aortic dissection detection risk score in patients with suspected acute aortic dissection. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. Dec 2014;3(4):373-81. [CrossRef]

- Body HSSI. Delayed recognition of acute aortic dissection. https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/delayed-recognition-of-acute-aortic-dissection/investigation-report/.

- McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276-82.

- Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. Nov 1 2013;67(11):974-8. [CrossRef]

- Riambau V, Bockler D, Brunkwall J, et al. Editor's Choice - Management of Descending Thoracic Aorta Diseases: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. Jan 2017;53(1):4-52. [CrossRef]

- Baliga RR, Nienaber CA, Bossone E, et al. The role of imaging in aortic dissection and related syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. Apr 2014;7(4):406-24. [CrossRef]

- Mills AM, Raja AS, Marin JR. Optimizing diagnostic imaging in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. May 2015;22(5):625-31. [CrossRef]

- Morello F, Santoro M, Fargion AT, Grifoni S, Nazerian P. Diagnosis and management of acute aortic syndromes in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. Jan 2021;16(1):171-181. [CrossRef]

- McHugh ML. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2013;23(2):143-9. [CrossRef]

- Blettner M, Sauerbrei W, Schlehofer B, Scheuchenpflug T, Friedenreich C. Traditional reviews, meta-analyses and pooled analyses in epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;28(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

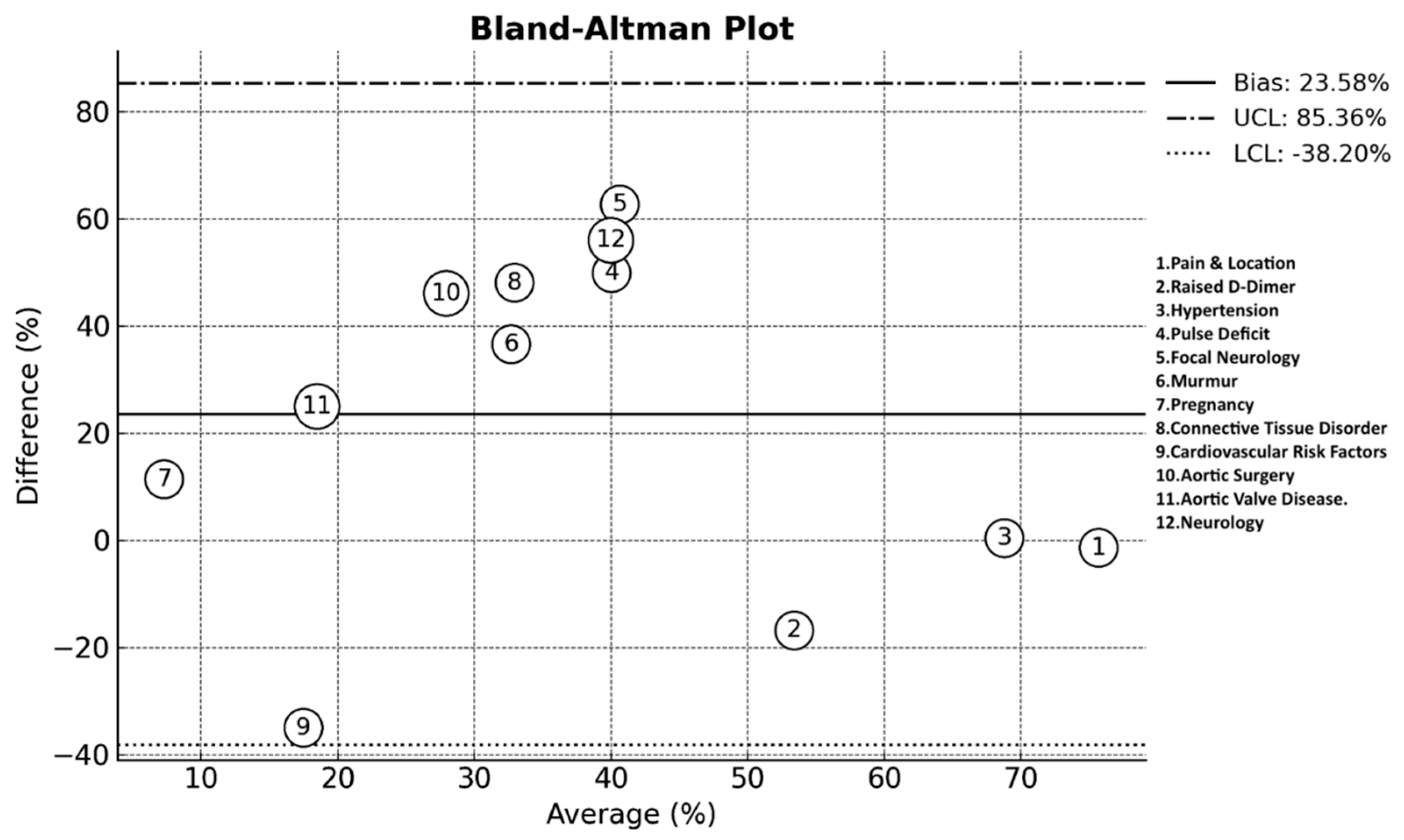

- Giavarina D. Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2015;25(2):141-51. [CrossRef]

- Gerke O. Reporting Standards for a Bland-Altman Agreement Analysis: A Review of Methodological Reviews. Diagnostics (Basel). May 22 2020;10(5). [CrossRef]

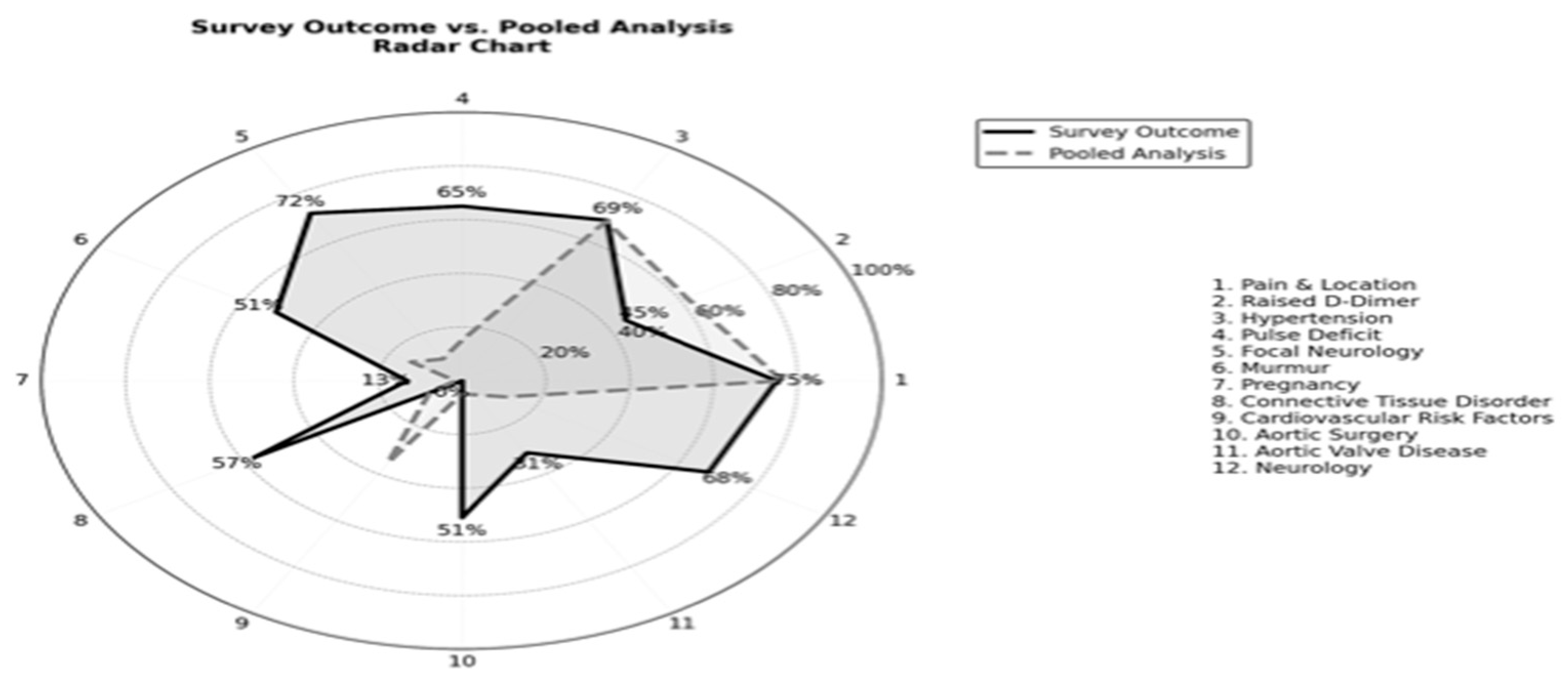

- Saary MJ. Radar plots: a useful way for presenting multivariate health care data. J Clin Epidemiol. Apr 2008;61(4):311-7. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki T, Mehta RH, Ince H, et al. Clinical profiles and outcomes of acute type B aortic dissection in the current era: lessons from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation. Sep 9 2003;108 Suppl 1:II312-7. [CrossRef]

- Morello F, Bima P, Pivetta E, et al. Development and Validation of a Simplified Probability Assessment Score Integrated With Age-Adjusted d-Dimer for Diagnosis of Acute Aortic Syndromes. J Am Heart Assoc. Feb 2 2021;10(3):e018425. [CrossRef]

- Nazerian P, Mueller C, Soeiro AM, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Aortic Dissection Detection Risk Score Plus D-Dimer for Acute Aortic Syndromes: The ADvISED Prospective Multicenter Study. Circulation. Jan 16 2018;137(3):250-258. [CrossRef]

- von Kodolitsch Y, Schwartz AG, Nienaber CA. Clinical prediction of acute aortic dissection. Arch Intern Med. Oct 23 2000;160(19):2977-82. [CrossRef]

- Ohle R, McIsaac S, Van Drusen M, et al. Evaluation of the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines Risk Prediction Tool for Acute Aortic Syndrome: The RIPP Score. Emerg Med Int. 2023;2023:6636800. [CrossRef]

- McLatchie R, Reed MJ, Freeman N, et al. Diagnosis of Acute Aortic Syndrome in the Emergency Department (DAShED) study: an observational cohort study of people attending the emergency department with symptoms consistent with acute aortic syndrome. Emerg Med J. Feb 20 2024;41(3):136-144. [CrossRef]

- Matsushita A, Tabata M, Mihara W, et al. Risk score system for late aortic events in patients with uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Jun 2020;159(6):2173-2183 e1. [CrossRef]

- Rogers AM, Hermann LK, Booher AM, et al. Sensitivity of the aortic dissection detection risk score, a novel guideline-based tool for identification of acute aortic dissection at initial presentation: results from the international registry of acute aortic dissection. Circulation. May 24 2011;123(20):2213-8. [CrossRef]

- Riambau V, Bockler D, Brunkwall J, et al. Editor's Choice - Management of Descending Thoracic Aorta Diseases: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. Jan 2017;53(1):4-52. [CrossRef]

- Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. Feb 16 2000;283(7):897-903. [CrossRef]

- Larson EW, Edwards WD. Risk factors for aortic dissection: a necropsy study of 161 cases. Am J Cardiol. Mar 1 1984;53(6):849-55. [CrossRef]

- Eagle KA, Isselbacher EM, DeSanctis RW, Investigators tIRfAD. Cocaine-Related Aortic Dissection in Perspective. Circulation. 2002;105(13):1529-1530. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Wicky S, Wintermark M, Schnyder P, Capasso P, Denys A. Imaging of blunt chest trauma. Eur Radiol. 2000;10(10):1524-38. [CrossRef]

- Cambria RP, Brewster DC, Gertler J, et al. Vascular complications associated with spontaneous aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. Feb 1988;7(2):199-209.

- Durham CA, Cambria RP, Wang LJ, et al. The natural history of medically managed acute type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. May 2015;61(5):1192-8. [CrossRef]

- Myles PS, Cui J. Using the Bland-Altman method to measure agreement with repeated measures. Br J Anaesth. Sep 2007;99(3):309-11. [CrossRef]

- Liu WT, Lin CS, Tsao TP, et al. A Deep-Learning Algorithm-Enhanced System Integrating Electrocardiograms and Chest X-rays for Diagnosing Aortic Dissection. Can J Cardiol. Feb 2022;38(2):160-168. [CrossRef]

- Thokala P, Goodacre S, Cooper G, et al. Decision analytical modelling of strategies for investigating suspected acute aortic syndrome. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2024:emermed-2024-214222. [CrossRef]

| Years Of Experience | Outcome | What Prompts CTA? | Outcome |

| 0-4 | 28% (95% CI: 22.1% - 35.5%) | Normal ECG | 9% (95% CI: 5.4% - 14.5%) |

| 5-10 | 31% (95% CI: 24.8% - 38.5%) | Normal Troponin | 10% (95% CI: 6.2% - 15.8%) |

| >10 | 41% (95% CI: 33.4% - 47.9%) | Raised D-Dimer | 44% (95% CI: 36.9% - 51.6%) |

| Prior Involvement (Yes) | 96% (n=166/173) | Raised Lactate | 25% (95% CI: 19.0% - 31.8%) |

| Prior Diagnosis | None Of the Above | 35% (95% CI: 28.3% - 42.2%) | |

| 0-4 | 49% (95% CI: 41.8% - 56.5%) | All Of the Above | 12% (95% CI: 8.0% - 17.8%) |

| 5-10 | 38% (95% CI: 31.0% - 45.1%) | ||

| >10 | 13% (95% CI: 8.9% - 18.9%) | Rapid CTA & Reporting: (Yes) | 70% (n=122/173) |

| A Differential in Chest Pain? (Yes) | 94% (n=163/173) | First Line Antihypertensive? | |

| Suspecting Symptoms | Labetalol | 88% (95% CI: 82.2% - 91.9%) | |

| Severity and Location of Pain | 75% (95% CI: 67.6% - 80.5%) | GTN | 19% (95% CI: 13.9% - 25.6%) |

| Neurology | 68% (95% CI: 60.3% - 74.2%) | Nitroprusside | 1% (95% CI: 0.3% - 4.1%) |

| Shortness Of Breath | 11% (95% CI: 7.1% - 16.5%) | Hydralazine | 0% (95% CI: 0.0% - 2.2%) |

| Nausea And Vomiting | 6% (95% CI: 3.6% - 11.0%) | I Don’t Start | 2.5% (95% CI: 0.9% - 5.8%) |

| All Of the Above | 25% (95% CI: 19.0% - 31.8%) | Site Management | |

| None Of the Above | 0.5% (95% CI: 0.1% - 2.5%) | Local | 41% (95% CI: 34.0% - 48.5%) |

| Suspecting Clinical Signs | Tertiary Centre | 47% (95% CI: 39.9% - 54.3%) | |

| Hypertension | 69% (95% CI: 61.7% - 75.2%) | Both | 12% (95% CI: 7.8% - 17.7%) |

| Pulse Deficit | 65% (95% CI: 57.7% - 71.6%) | Speciality Management | |

| Focal Neurology | 72% (95% CI: 64.7% - 78.1%) | Internal Medicine | 33% (95% CI: 26.4% - 39.9%) |

| Reduced Air Entry | 0.5% (95% CI: 0.1% - 2.5% | Vascular Surgery | 40% (95% CI: 33.4% - 47.0%) |

| Murmurs | 50% (95% CI: 42.6% - 57.4%) | Cardiothoracic Surgery | 51% (95% CI: 43.6% - 58.2%) |

| All Of the Above | 20% (95% CI: 14.7% - 26.6%) | Decision Tool Awareness? | |

| Risk Factor? | Aortic Dissection Decision Tool | 26% (95% CI: 20.1% - 32.9%) | |

| Age | 48% (95% CI: 40.4% - 55.7%) | ADDR + Age Adjusted D-Dimer | 19% (95% CI: 13.9% - 25.6%) |

| Gender | 30% (95% CI: 23.8% - 37.1%) | ADDR + D-Dimer >500 | 19% (95% CI: 13.9% - 25.6%) |

| Pregnancy | 13% (95% CI: 8.9% - 18.7%) | ADDR + Ascending Aorta > 40 | 1.5% (95% CI: 0.5% - 4.3%) |

| Connective Tissue Disorder | 56% (95% CI: 48.6% - 62.8%) | None Of the Above | 51% (95% CI: 43.6% - 58.2%) |

| Cardiovascular Risk Factors | 0% (95% CI: 0.0% - 2.1%) | All Of the Above | 0.5% (95% CI: 0.1% - 2.5%) |

| Aortic Surgery | 51% (95% CI: 43.6% - 58.2%) | Is Stratification Useful? (Yes) | 85% (n=147/173) |

| Family History of Aortic Valve Disease | 31% (95% CI: 24.6% - 38.3%) | Rate Of Misdiagnosis? | |

| All Of the Above | 39% (95% CI: 31.7% - 46.5%) | 10-29% | 31% (95% CI: 24.6% - 38.3%) |

| In Teaching Programme? (Yes) | 93% (n=161/173) | 30-49% | 39% (95% CI: 31.7% - 46.5%) |

| Is There a SOP (Yes) | 32% (n=55/173) | >50% | 30% (95% CI: 23.5% - 37.3%) |

|

Group 1 (0-4 years) |

Group 2 (5-10 years) |

Group 3 (>10 years) |

p-value | |

| How Many Diagnosed (0-4) | 67.35% (95% CI: 54.22% - 80.48%) |

57.41% (95% CI: 44.22% - 70.60%) |

28.99% (95% CI: 18.28% - 39.69%) |

p < 0.001 |

| How Many Diagnosed (5-10) | 26.53% (95% CI: 14.17% - 38.89%) |

33.33% (95% CI: 20.76% - 45.91%) |

50.72% (95% CI: 38.93% - 62.52%) |

p < 0.05 |

| How Many Diagnosed (>10) | 6.12% (95% CI: 0.00% - 12.84%) |

9.26% (95% CI: 1.53% - 16.99%) |

20.29% (95% CI: 10.80% - 29.78%) |

p < 0.05 |

| Murmurs | 48.98% (95% CI: 34.98% - 62.98%) |

37.04% (95% CI: 24.16% - 49.92%) |

65.22% (95% CI: 53.98% - 76.46%) |

p < 0.01 |

| Normal ECG as a Prompt | 4.08% (95% CI: 0.00% - 9.62%) |

1.85% (95% CI: 0.00% - 5.45%) |

17.39% (95% CI: 8.45% - 26.33%) |

p < 0.01 |

|

Rapid CT & Reporting |

59.18% (95% CI: 45.42% - 72.95%) |

64.81% (95% CI: 52.08% - 77.55%) |

82.61% (95% CI: 73.67% - 91.55%) |

p < 0.05 |

| First Line Antihypertensive: Labetalol | 100.00% (95% CI: 100.00% - 100.00%) |

92.59% (95% CI: 85.61% - 99.58%) |

86.96% (95% CI: 79.01% - 94.90%) |

p < 0.05 |

| ESVS |

Ohle et al. |

Von Kodolitsch et al. |

Lovy et al. |

McLatchie et al. |

Morello et al. |

Rogers et al. |

Nazerian et al. |

Matsushita et al. | Suzuki et al. | Pooled Analysis | |

| Pain & Location | 80% | 81.2% | 79% | 83-89% | 44-86% | - | 72.7-79.3% | - | 44-69% | 86.3-89.2% | 76.4% (95% CI: 72.7% - 79.8%) |

| Neurology | - | - | 20% | - | 8% | 10.2% | - | - | 6% | - | 11.5% (95% CI: 7.6% - 17.0%) |

| Shortness of Breath | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | N/A |

| Nausea/Vomiting | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | N/A |

| Hypertension | - | - | 82% | 82.1% | 31% | 69.4% | - | 55.4% | 73% | 69.1% | 68.6% (95% CI: 61.5% - 74.9%) |

| Pulse deficit | 9% | 5.3% | 38% | - | 1% | 14.3% | 20.3% | 7.9% | - | 21.1% | 15.1% (95% CI: 10.6% - 21.1% |

| Focal neurology | 7% | 10.8% | 13% | - | 5% | 1.41–5.42% | 10.8% | 11.4% | 3% | 4.7% | 9.3% (95% CI: 5.8% - 14.4%) |

| Reduced Air Entry | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | N/A |

| Murmur | - | 4.2% | 28% | - | 0.2% | 2.7% | 23.6% | - | - | - | 14.4% (95% CI: 9.7% - 20.8%) |

| Age | Yes** | 68.5 | 57 | 66 | 55 | 70 | - | 62 | 71 | 64.6 | 64.5 (95%CI: 61- 69 years) |

| Pregnancy | Yes* | - | - | - | 3% | - | - | - | - | 0.2% | 1.6% (95% CI: 1.1% - 4.3%) |

| Connective tissue disorder | 13-22% | 0.2% | - | - | 0.5% | 5% | 4.3% | - | - | 2.9% | 8.9% (95% CI: 5.6% - 14.1%) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | - | 6% | - | - | - | 42.9% | - | - | 53% | 42% | 35.0% (CI: 10.7% -59.3%) |

| Aortic surgery | - | 0.3% | - | - | 1% | 2% | 2.8% | - | - | 12.3% | 4.9% (95% CI: 2.6% - 9.0%) |

| Aortic Valve Disease | - | 1.5% | - | - | 2% | 14.3% | 11.9% | - | - | - | 6.3% (95% CI: 3.4% - 11.5%) |

| Normal ECG | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 31% | N/A |

| Normal Troponin | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | N/A |

| Raised D-Dimer | Yes* | - | - | - | 40% | 18.2–77.8% | Yes* | YES* | 94-97% | Yes* | 61.8% (95% CI: 54.4% - 68.7%) |

| Raised Lactate | Yes* | - | - | - | Yes* | - | - | - | - | - | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).