1. Introduction

Morningglories (

Ipomoea spp., Convolvulaceae) are among the most troublesome broadleaf weeds in row-crop systems across the southeastern United States. These summer weeds pose significant challenges in soybean, cotton, and corn rotations. Their vining growth habit affects crop structure, making harvest more difficult, even causing grain contamination [

1,

2]. Even a few late-season escapes can slow down combines due to vine entanglement, thereby reducing harvest efficiency [

1]. Regional field studies have documented substantial yield losses caused by morningglories, with pitted morningglory (

Ipomoea lacunosa L.) reducing soybean yield by 47–81% depending on plant density [

3]. Earlier research also reported strong competitive effects of morningglories on soybean and cotton growth [

4,

5].

Ipomoea lacunosa, ivyleaf morningglory (

Ipomoea hederacea Jacq.), and tall morningglory [

Ipomoea purpurea (L.) Roth] from the Convolvulaceae family are herbaceous, twining summer annuals, originating from Central and South America [

6], and are widely found in landscapes across the globe, distributed as ornamentals due to their vibrant flowers and rapid growth [

7]. Depending on the species and local growing conditions, flowering usually starts in early summer and can last four to six months [

7]. Morningglories are recognized for their sun-following blooms, which open at dawn and close by late afternoon [

8]. Of the three species,

I. purpurea is the largest, with petals about 4.5–7 cm long and leaves 5–13 cm long.

Ipomoea lacunosa is much smaller, with petals only 1.5–2 cm and leaves up to 9.5 cm, while ivyleaf morningglory falls between these extremes, with petals 2.8–5 cm and leaves 5–13 cm [

1]. Their seed pods split open when mature, dropping seeds near the parent plant. Although most seeds fall naturally, harvest equipment, animals, and pre-existing seedbanks often contribute to wider dispersal [

1].

One of the primary reasons morningglories remain a persistent problem in row-crop systems is their seed characteristics. These species produce hard-coated seeds capable of surviving for years in the soil seedbank [

1,

9], and their impermeable palisade layer enforces physical dormancy (PY), which contributes to long-term persistence [

10,

11]. Morningglory seeds undergo sensitivity cycling and can germinate across an extended portion of the growing season, allowing cohorts to escape early-season control measures [

12,

13,

14]. This issue is especially pronounced in reduced-tillage and no-till systems, where seeds remain near the soil surface and experience strong diurnal temperature fluctuations and repeated wet–dry cycles that promote staggered emergence [

1,

13]. Despite their agronomic importance, information on the cues regulating dormancy release, the environmental factors controlling germination, and the seasonal dynamics of emergence across species is still incomplete and scattered across the literature.

This review synthesizes current knowledge on the seed dormancy and germination ecology of three morningglory species prevalent in the southeastern United States, I. lacunosa, I. hederacea, and I. purpurea. Using South Carolina as an example of a warm-temperate region, we review what is known about dormancy mechanisms, the environmental factors that break dormancy and trigger germination, and seasonal patterns of seedling emergence. We also highlight some key knowledge gaps, such as the influence of maternal environments on dormancy, variation among populations, and the longevity of seeds in southeastern soils. In summary, this synthesis aims to enhance the ecological understanding of Ipomoea seed traits and to develop weed management strategies for addressing these problematic species in summer crops.

2. Basic Concepts of Seed Dormancy and Germination

Dormancy is an inherent seed trait that defines the environmental requirements for germination [

15]. It prevents viable seeds from germinating when suitable conditions for temperature, moisture, and gas exchange are present. This trait is key to the persistence of annual weeds in agroecosystems [

15,

16,

17]. Dormancy levels vary widely, not only among species but also within populations and even among seeds from the same maternal plant, reflecting both genetic differences and environmental influences during seed development [

18]. The degree of dormancy determines how broad or narrow the environmental conditions must be for germination to occur. Seeds with low dormancy can germinate under a wide range of temperatures and water potentials, while highly dormant seeds require very specific conditions [

19,

20]. Seasonal changes in temperature and soil moisture drive dormancy level changes, while signals such as light quality or alternating temperatures can act as immediate triggers once seeds become sensitive enough [

16,

20]. Together, these processes create the staggered emergence patterns seen in the field and contribute to the demographic resilience of many agricultural weed species.

3. Target Species

3.1. Ipomoea Lacunosa

Ipomoea lacunosa is widely distributed in warm–temperate and subtropical regions of the Americas, with naturalized populations reported in both North and South America, particularly in agricultural and disturbed habitats [

21,

22]. It is typically found in summer crops, such as soybeans, cotton, and maize fields, as well as along field edges and in no-till systems. This species thrives in disturbed soils, and its slender, twining vines often climb crop stems, competing for resources and interfering with harvest operations [

14,

22]. In many southeastern states, including South Carolina, I. lacunosa is generally the most abundant morningglory species in-season surveys of row crops and is considered a consistent contributor to season-long vine pressure. The species is characterized by delicate, white to pale lavender flowers and small, wedge-shaped seeds released from dehiscent capsules. It flowers and sets seed over an extended part of the summer, even when emergence occurs relatively late [

23]. Even under moderate crop competition, plants can produce a significant amount of seeds, and those that escape herbicide controls often produce seeds that contribute to replenishing the seedbank [

24,

25]. The seeds are small, hard, and long-lived, allowing them to persist in the soil for years and maintain seedbanks that lead to repeated infestations [

26].

3.2. Ipomoea Hederacea

Ipomoea hederacea is found throughout warm–temperate and tropical regions worldwide and is recognized as an agricultural weed in North America, South America, and parts of Asia. It is present in agricultural fields in Iran, as documented by seed collections used in germination studies [

27]. It is generally less abundant than I. lacunosa in many southeastern production systems, but its presence is consistent across multiple cropping environments, and infestations may persist throughout the growing season. In growth studies, I. hederacea emerged successfully across a wide range of planting dates and produced substantial biomass and seeds even under competitive conditions, demonstrating strong adaptability to variable agricultural environments [

28,

29]. Plants typically complete their life cycle within seven to nine weeks after emergence, allowing late-season cohorts to contribute seed to the soil seedbank. The species produces dehiscent capsules that release wedge-shaped seeds, which remain viable in the soil for multiple years. Storage and field-aging studies demonstrate that seeds maintain relatively high viability during the first few years after dispersal and gradually increase in germinability over time, indicating a strong persistence potential under natural field conditions [

23]. I. hederacea can also tolerate a broad range of environmental growing conditions, with evidence of establishment and spread in regions outside the United States, including Iran [

27]. In cropping systems, its climbing habit enables it to interfere with harvest, and its season-long emergence patterns make it a persistent competitor and seedbank contributor, particularly in reduced-tillage systems. Although typically less dominant than I. lacunosa, I. hederacea remains an agronomically important species due to its reproductive flexibility and capacity to occupy a wide range of field microenvironments.

3.3. Ipomoea Purpurea

Ipomoea purpurea is widely distributed across tropical and warm–temperate regions in North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa [

30,

31]. It is considered one of the most abundant and persistent morningglory species in soybean, cotton, and corn production systems, where its vigorous vining habit enables it to climb crop plants and interfere with field operations. When conditions favor its growth, this species is capable of forming dense infestations [

21,

32]. It can produce great amounts of seeds, even beneath the competitive crop canopies of other plants [

23,

32]. The species is distinguished by its twining stems, and the leaves can exhibit differences in morphology, ranging from heart-shaped to slightly lobed [

33]. Seeds are generally wedge-shaped and dark, with a robust testa; however, some variation among populations has been reported [

31].

In cropping systems,

I. purpurea is considered especially problematic because of its aggressive vining behavior and its ability to persist as late-season escapes, which interfere with harvest efficiency and contribute to long-term seedbank enrichment. Reports of herbicide-resistant populations, including those resistant to glyphosate, have been documented in southeastern U.S. populations [

34,

35].

4. Dormancy Mechanisms in Morningglories

Morningglories possess a dormancy system dominated by PY, imposed by a water-impermeable seed coat that prevents imbibition at maturity. Detailed anatomical studies reveal that the seed coat of

I. lacunosa and

I. hederacea comprises a thick palisade layer of macrosclereids, forming a tightly packed, lignified barrier that restricts water entry [

10]. Physical dormancy is associated with a specialized water gap, a morpho-anatomical feature located near the lens–hilum region, that remains sealed in dormant seeds and functions as the primary site of water entry after dormancy break [

11]. In these species, the lens is the key site for structural change. When dormancy-breaking cues occur, this region cracks, loosens, or separates from the underlying tissues, creating an opening that allows water to enter the seed [

11] (

Table 1).

Seeds usually acquire PY as the palisade layer becomes completely impermeable during maturation and desiccation on the mother plant [

10]. Once seeds reach the seedbank, they are exposed to environmental cues that disrupt or loosen the seed coat structures. However, depending on environmental conditions, seeds can transition between water-gap-sensitive and insensitive states. A phenomenon known as sensitivity cycling, in

I. lacunosa and

I. hederacea, explains how these species distribute germination across multiple seasons [

12]. Warm or fluctuating temperatures and extended wet periods tend to make the water gap more sensitive, thereby reducing the seed dormancy level. In contrast, cooler or drier conditions can cause seeds to revert to an insensitive state [

12]. Newly matured

I. lacunosa seeds exhibit strong inhibition by light and temperature interactions, characteristics that disappear only after ripening, indicating the presence of a transient physiological dormancy layer superimposed on PY [

13] (

Table 1). This physiological component does not prevent imbibition but suppresses germination even when the seed coat becomes permeable. This dual dormancy system contributes to prolonged seed persistence, asynchronous emergence, and the ability of

Ipomoea species to maintain long-lived, resilient seedbanks in agricultural soils.

5. Environmental Factors Affecting Dormancy Release

Environmental conditions have a strong effect on the dormancy release process in these species. Whether by altering seed-coat permeability, changing water-gap sensitivity, and shifting physiological readiness to germinate. In the field, seeds encounter variable thermal amplitudes, fluctuating moisture regimes, and diverse soil environments, all of which drive the progressive release of PY. These processes closely align with the general principles of dormancy regulation described for many weed species, where environmental drivers modulate both the degree of dormancy and the sensitivity of seeds to germination cues [

19,

20].

5.1. Temperature and Temperature Fluctuations

Temperature is one of the primary drivers of dormancy release in morningglories. After-ripened seeds of I. lacunosa, with low dormancy levels, germinate across a very wide thermal range (7.5–52.5 °C). In addition, fluctuating day–night temperatures enhance dormancy loss, indicating that the fluctuating temperatures might contribute to the opening of the water gap [

13]. Anatomical studies have shown that elevated temperatures increase the sensitivity of the lens region to moisture and rupture [

10,

11] (Jayasuriya et al., 2007, 2008) (

Table 1). These species-specific findings are consistent with the broader dormancy release theory, where seeds transitioning from high to low dormancy levels increase their tolerance to a wider range of temperatures, thereby enhancing germination [

19,

20]. Morningglory seeds follow this same pattern, reduced dormancy corresponds with a wider range of permissive temperatures and faster response to thermal fluctuations.

5.2. Soil Moisture, Hydration–Dehydration Cycles

Soil moisture is another important regulator of PY release in Ipomoea species. Hydration–dehydration cycles induce structural changes in the palisade layer and lens region, thereby increasing the likelihood that the water gap will open [

10,

12]. In the field, cycles of rainfall and drying may contribute to the extended emergence periods seen during the growing season. For example, fluctuating moisture speeds up germination in I. lacunosa, once the seeds have undergone after-ripening. Prolonged waterlogging can slow or even prevent dormancy release [

24] (

Table 1).

5.3. Burial Depth and Soil Physical Conditions

Burial depth affects the temperature and moisture conditions surrounding Ipomoea seeds in the seedbank, altering the rate of dormancy release. Seeds at or near the soil surface experience higher thermal amplitudes and more frequent wet–dry cycling, which increases their permeability to water and reduces the dormancy level of seeds [

13]. On the contrary, deeper burial reduces thermal fluctuations and increases moisture stability, which can promote gradual relaxation of PY over longer time periods [

2].

5.4. Mechanical, Microbial, and Chemical Scarification in Soil

Another important factor influencing seed dormancy release in morninggloy species is the long-term exposure to soil processes, which weakens the seed coat. After dispersion, seeds reach the seedbank and are exposed to several processes, including mechanical stress caused by freeze–thaw cycles, soil movement, and abrasion from soil particles, as well as microbial breakdown of surface tissues that can thin or fracture the palisade layer, leading to water-gap opening and reducing the dormancy level of seeds. I. lacunosa buried seeds are less exposed to these conditions and, therefore, can stay viable and dormant for decades in the soil due to the reduced seed coat deterioration [

26]. These scarification processes occur over months or years, driving dormancy cycling and the extended emergence patterns characteristic of Ipomoea seedbanks. Laboratory experiments confirm that physical weakening or removing the lens region quickly increases permeability [

10]. Any exogenous chemical compounds that mimic natural scarification, altering seed-coat properties or disrupting the palisade layer, can be applied to reduce the seed dormancy of morningglory seeds [

22].

6. Germination Requirements

Germination patterns in I. lacunosa, I. hederacea, and I. purpurea result from interactions among temperature, moisture, light, and seed age, with species-specific differences shaped by their PY and after-ripening dynamics.

6.1. Thermal Requirements and Optimal Conditions

Once PY is released, temperature plays a strong role in regulating germination in these species. I. purpurea has well-characterized cardinal temperatures, with a base temperature of 7–8 °C, optimum temperatures between 23–30 °C, and a maximum of 39–40 °C [

39]. Recently dispersed I. purpurea seeds germinate best at constant temperatures of 15–25 °C, with germination declining sharply at 35–40 °C [

35]. Alternating temperature regimes enhance germination, with 25/15 °C and 30/20 °C achieving germination rates of 86–89% [

37]. Nondormant I. hederacea seeds germinate at an optimum range of 20–25 °C and show little to no germination at 15 °C [

23]. In nondormant seeds, alternating temperatures of 15/25 °C resulted in up to 94% germination, with similarly high values under 20/30 °C [

27]. Ipomoea lacunosa shows the highest germination at moderate temperatures (20–25 °C) once physical dormancy is removed, based on tests using scarified or after-ripened seeds [

11] (

Table 1).

6.2. Light Sensitivity

Light is not a requirement once PY is released. I. purpurea germinates similarly in light and darkness under constant and fluctuating temperatures [

36], and I. lacunosa is known to emerge successfully under dense crop canopies [

38] (

Table 1).

6.3. Moisture and Water Potential

Moisture has a strong interaction with temperatures to promote germination in these species. Although all three Ipomoea species require adequate soil moisture to imbibe and initiate germination, I. purpurea is the only species for which quantitative moisture thresholds have been documented. I. purpurea can germinate under mild water stress, but the germination is reduced when water availability is reduced (80–90% at 0.0 MPa, approximately 60% at –0.2 MPa, 30–40% at –0.4 MPa, less than 10% at –0.6 MPa, and 0% at –0.8 MPa) [

37]. In I. lacunosa, saturated or waterlogged soils reduce germination by preventing dormancy break rather than by inhibiting germination itself [

24] (

Table 1).

6.4. Seed Age and After-Ripening

Seed ageing generally increases germination percentages across the three species by reducing the strength of PY. In I. purpurea, germination expands from a narrow range (15–25 °C) at maturity to a much wider range (10–40 °C) after 6 months of dry after-ripening [

36]. Storage of I. hederacea for two months at 35/20 °C increases germination to more than 80%, and room-temperature storage for five months increases it to ~45% [

12] (

Table 1).

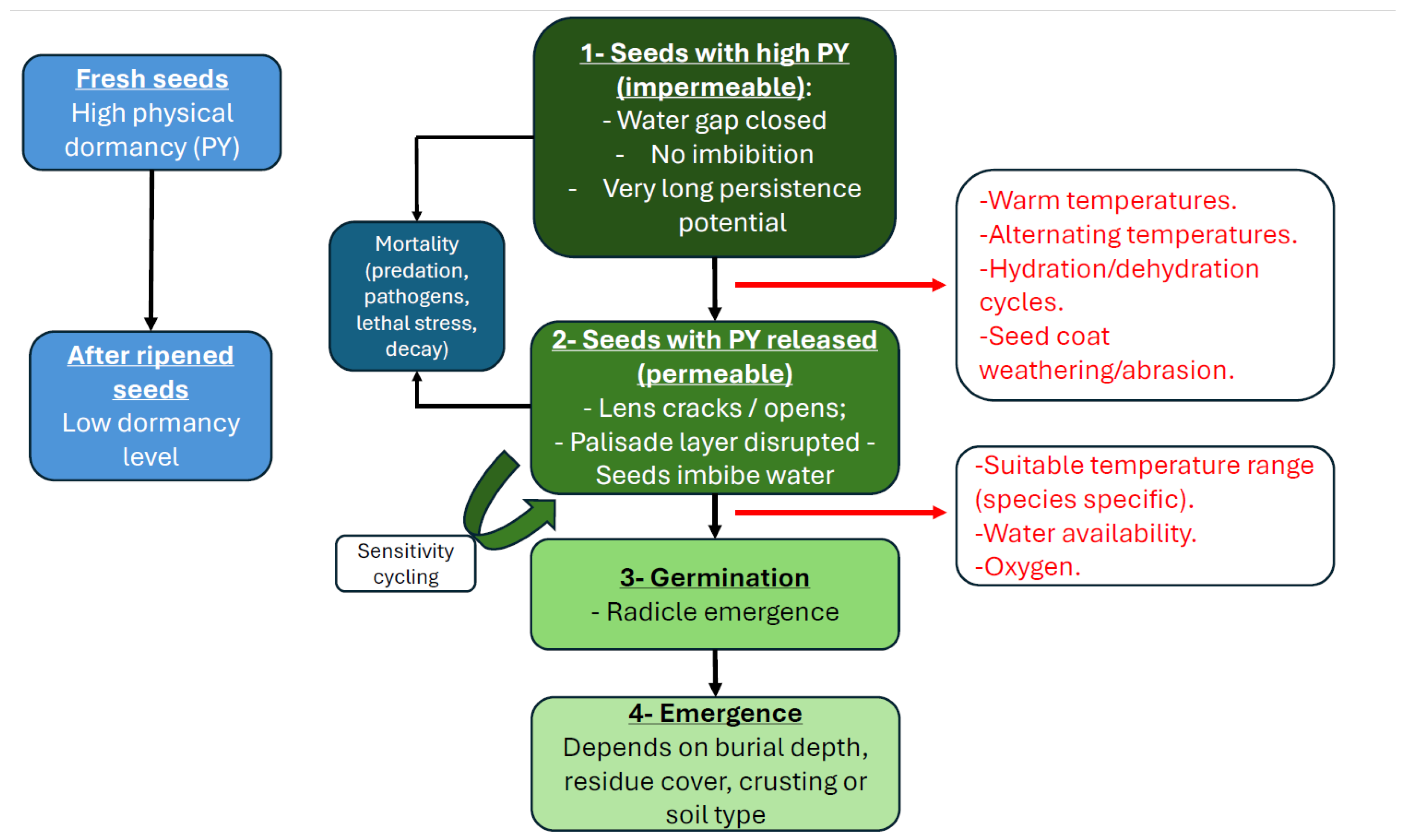

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram summarizing the transition from high physical dormancy to germination and emergence in Ipomoea spp., highlighting after-ripening, environmental cues that break physical dormancy, and factors influencing germination and seedling emergence.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram summarizing the transition from high physical dormancy to germination and emergence in Ipomoea spp., highlighting after-ripening, environmental cues that break physical dormancy, and factors influencing germination and seedling emergence.

7. Seasonal Emergence Patterns

Morningglories tend to emerge over an extended period throughout the warm-temperate regions. Ipomoea lacunosa begins to emerge in late spring, when soil temperatures are rising and seed dormancy levels are low. In no-till systems, seeds emerge earlier than in conventional systems due to the environmental conditions explored by the seeds on the surface, higher temperature fluctuations and repeated wet–dry cycles. Emergence continues into midsummer [

13,

14]. Field observations in wheat–soybean and soybean systems show that I. lacunosa continues to produce new cohorts under canopy shade, even when red:far-red ratios are extremely low, indicating that germination and early emergence are primarily driven by temperature and moisture rather than the light environment [

38] (

Table 1).

Ipomoea hederacea exhibits a slightly later and often more prolonged emergence period relative to I. lacunosa. It has the ability to emerge and complete its life cycle even when it emerges relatively late in the season [

28,

29]. Emergence has been observed well into mid-season in soybean and cotton systems [

13,

14,

38]. This prolonged emergence period enables the species to evade early-season control measures and replenish the seedbank (

Table 1).

For Ipomoea purpurea, emergence timing is similarly extended. The species shows high ecological plasticity and is capable of establishing under variable thermal and moisture conditions [

33]. The species produces successive emergence cohorts across several weeks in spring and early summer, especially when seedbank densities are high [

37]. It is capable of establishing new seedlings even under crop canopy shade [

35,

36] (

Table 1).

8. Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

While research has shed light on key aspects of PY, germination ecology, and emergence timing in Ipomoea species, important gaps remain that limit our understanding of their dynamics in warm-temperate agroecosystems such as the southeastern United States and similar regions worldwide.

8.1. Maternal Environmental Effects on Dormancy Intensity

Seed dormancy is strongly influenced by conditions experienced by the maternal plant in many species, but this remains largely unstudied in Ipomoea spp. There are no published studies quantifying how temperature, drought, nutrient availability, or crop competition during seed development alter (I) the strength of PY, (II) the likelihood of sensitivity cycling, or (III) the physiological dormancy component described in I. hederacea and I. purpurea. Understanding these maternal effects is essential for predicting year-to-year variability in emergence patterns.

8.2. Population-Level Variation in Dormancy, Permeability, and Germination Traits

Most detailed dormancy studies [

10,

11,

12] use single populations. Yet, both

I. hederacea and

I. purpurea are known to exhibit ecological differentiation and local adaptation in other traits (e.g., growth, reproduction). Whether populations differ in palisade-layer thickness, water-gap sensitivity, after-ripening requirements, or physiological dormancy is unknown. Such variation could strongly influence emergence timing and herbicide escape rates across regions.

8.3. Long-Term Seedbank Persistence

Only a handful of studies provide hard estimates of seed longevity for

I. lacunosa [

9,

26]. No comparable long-term data exists for

I. hederacea or

I. purpurea, and no modern burial trials have been conducted under current reduced-tillage and cover-crop systems. The widespread adoption of no-till in subtropical regions is likely to alter seed persistence dynamics through changes in moisture and temperature regimes, but empirical verification is lacking.

8.4. Integration of Climatic Drivers into Predictive Emergence Models

To date, no thermal-time or hydrothermal-time models have been developed for Ipomoea species. Without mechanistic frameworks that link environmental conditions, dormancy transitions, and germination probability, emergence prediction remains highly uncertain. Building such models is critical, especially as warmer winters, earlier springs, and increasingly erratic precipitation patterns reshape seasonal dynamics.

8.5. Impacts of Cover Crops on Dormancy Release, Germination Cues, and Emergence Timing

While some emergence suppression has been observed anecdotally, no mechanistic studies evaluate how cover crop residues influence seedbank environment where Ipomoea seeds are to explain their effects on water-gap opening, after-ripening dynamics, physiological dormancy, or the timing of recruitment in Ipomoea species.

8.6. Seed Predation, Microbial Decay, and the Biological Seedbank Pathway

Seed fate in the soil is influenced not only by PY and abiotic drivers but also by soil biota. No studies quantify rates of microbial degradation, fungal infection, or invertebrate seed predation for any of the three species. These biological processes may play a substantial role in determining seedbank persistence under no-till systems, particularly in warm, humid regions such as the southeastern United States.

9. Conclusions

Morningglories continue to be persistent weeds in summer row crops across warm–temperate and subtropical regions, in part due to their long-lived seedbanks, strong PY and their ability to germinate under a wide range of environmental conditions. Understanding how dormancy interacts with temperature, moisture, burial depth, and canopy microclimate is essential for comprehending why these species persist in reduced-tillage and no-till systems. This review synthesizes current knowledge on dormancy processes, germination cues, and emergence patterns, highlighting the need for predictive and mechanistic models to enhance management strategies. Incorporating these traits into mechanistic seedbank and emergence models represents a promising path toward improving the timing and effectiveness of weed management strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.H.O. and H.H.; methodology, F.H.O.; validation, F.H.O. and H.H.; formal analysis, F.H.O.; investigation, H.H.; resources, F.H.O.; data curation, H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H. and F.H.O.; writing—review and editing, F.H.O. and H.H.; visualization, F.H.O.; supervision, F.H.O.; project administration, F.H.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mohler, C. L., Teasdale, J. R., DiTommaso, A. Manage weeds on your farm: a guide to ecological strategies. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education. 2021.

- Oliveira, M.J.; Norsworthy, J.K. Germination characteristics of pitted morningglory (Ipomoea lacunosa). Weed Sci. 2006, 54, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsworthy, J.K.; Oliver, L.R. Pitted morningglory (Ipomoea lacunosa) interference with soybean (Glycine max). Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, R.H.; Buchanan, G.A. Competition of four morningglory species with cotton. Weed Sci. 1978, 26, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe III, O.W. , Oliver, L.R. Influence of soybean (Glycine max) row spacing on pitted morningglory (Ipomoea lacunosa) interference. Weed Sci, 1987, 35, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, C.T., DeFelice, M.S. Convolvulaceae (MorningGlory) Weeds of the South. 2009, University of Georgia Press, pp. 165–175.

- Bei, Z.; Lu, L.; Amar, Z.; Zhang, X. Light Adaptations of Ipomoea purpurea (L.) Roth: Functional Analysis of Leaf and Petal Interfaces. Plants 2025, 14, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D.F. Convolvulaceae—Morning Glory Family. J. Ariz.-Nev. Acad. Sci. 1998, 30, 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Toole, E.H.; Brown, E. Final results of the USDA seed viability tests. J. Agric. Res. 1946, 72, 201–224. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasuriya, K.M.G.G., Baskin, J.M., Geneve, R.L., Baskin, C.C. (2007). Morphology and anatomy of physical dormancy in Ipomoea lacunosa: identification of the water gap in seeds of Convolvulaceae (Solanales). Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 13–22.

- Jayasuriya, K.M.G.G. , Baskin, J.M., Geneve, R.L., Baskin, C.C. Seed development in Ipomoea lacunosa (Convolvulaceae), with particular reference to anatomy of the water gap. Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasuriya, K.M.G.G.; Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. Sensitivity cycling in physically dormant seeds of Ipomoea hederacea and I. lacunosa. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Norsworthy, J.K.; Oliveira, M.J. Role of light quality and temperature on pitted morningglory (Ipomoea lacunosa) germination with after-ripening. Weed Sci. 2007, 55, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenfeld, K.L.; Martin, A.R.; Mortensen, D.A.; Mason, S.C. Weed management in glyphosate resistant soybean: weed emergence patterns in relation to glyphosate treatment timing. Weed Technol. 2004, 18, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vleeshouwers, L.M.; Bouwmeester, H.J.; Karssen, C.M. Redefining seed dormancy: An attempt to integrate physiology and ecology. J. Ecol. 1995, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S.; Macchia, M. Seedbank reduction after different stale seedbed techniques in organic agriculture systems. Ital. J. Agron. 2006, 1, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, M. The effects of the parent environment on seed germinability. Seed Sci. Res. 1991, 1, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benech-Arnold, R.L.; Sánchez, R.A.; Forcella, F.; Kruk, B.C.; Ghersa, C.M. Environmental control of dormancy in soil seedbanks. Field Crops Res. 2000, 67, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlla, D., Benech-Arnold, R.L. Predicting changes in dormancy level in natural seed soil banks. Plant mol. Biol., 2010, 73, 3–13.

- Jones, E.A.; Contreras, D.J.; Everman, W.J. Ipomoea hederacea, Ipomoea lacunosa, and Ipomoea purpurea. In Biology and Management of Problematic Crop Weed Species; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 241–259. [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi, S., Yazlık, A., Bazos, I., Gherekhloo, J., Kati, V., Kitiş, Y.E., Arianoutsou, M., Kortz, A. and Pyšek, P. Alien species of Ipomoea in Greece, Türkiye and Iran: distribution, impacts and management. NeoBiota, 2025, 97, 135–160.

- Asami, H. , Ishioka, G., Homma, K. Relationship between storage period and germination of Ipomoea hederacea var. integriuscula seeds under natural condition. Weed Biol. Manag. 2021, 21, 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Gealy, D.R. Differential response of palmleaf morningglory (Ipomoea wrightii) and pitted morningglory (Ipomoea lacunosa) to flooding. Weed Sci., 1998, 46, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoveland, C. S. , Buchanan, G. A. (1973). Weed seed germination under simulated drought. Weed Sci. 1973, 21, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egley, G.H. , Chandler, J.M. Germination and viability of weed seeds after 2.5 years in a 50-year buried seed study. Weed Sci. 1978, 26, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahmarguee, A. , Gorgani, M., Ghaderi-Far, F., Asgarpour, R. Germination ecology of Ivy-leaved morning-glory: an invasive weed in soybean fields, Iran. Planta Daninha, 2020, 38, e020196227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thullen, R.J. , Keeley, P.E. Germination, growth, and seed production of Ipomoea hederacea when planted at monthly intervals. Weed Sci. 1983, 31, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, P.E. , Thullen, R.J., Carter, C.H. Influence of planting date on growth of ivyleaf morningglory (Ipomoea hederacea) in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Weed Sci. 1986, 34, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mircea, D. M. , Li, R., Blasco Giménez, L., Vicente, O., Sestras, A. F., Sestras, R. E., Boscaiu M., Mir R. Salt and water stress tolerance in Ipomoea purpurea and Ipomoea tricolor, two ornamentals with invasive potential. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunwenmo, K. Variation in fruit and seed morphology, germination and seedling behaviour of some taxa of Ipomoea L.(Convolvulaceae). Feddes Repert. 2006, 117, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, A.A.M., Ferreira, P.S.H., Martins, D. Growth and development of Ipomoea weeds. Planta Daninha, 2019, 37, e019186421.

- Liu, C.C. , Gui, M.Y., Sun, Y.C., Wang, X.F., He, H., Wang, T.X., Li, J.Y. Doubly guaranteed mechanism for pollination and fertilization in Ipomoea purpurea. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debban, C.L. , Okum, S., Pieper, K.E., Wilson, A., Baucom, R.S. An examination of fitness costs of glyphosate resistance in the common morning glory, Ipomoea purpurea. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 5284–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P., Norsworthy, J. K., Kumar, V., Reichard, N. Annual changes in temperature and light requirements for Ipomoea purpurea seed germination with after-ripening in the field following dispersal. Crop Prot. 2015, 67, 84–90.

- Pazuch, D., Trezzi, M. M., Diesel, F., Barancelli, M. V. J., Batistel, S. C., & Pasini, R. (2015). Superação de dormência em sementes de três espécies de Ipomoea. Ciência Rural, 45, 192-199.

- Singh, M., Ramirez, A.H., Sharma, S.D. and Jhala, A.J. Factors affecting the germination of tall morningglory (Ipomoea purpurea). Weed Sci. 2012, 60, 64–68.

- Norsworthy, J.K. Soybean canopy formation effects on pitted morningglory (Ipomoea lacunosa), common cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium), and sicklepod (Senna obtusifolia) emergence. Weed Sci. 2004, 52, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, I. , Zaefarian, F., Younesabadi, M. Study of biological aspect of germination and emergence in morning glory (Ipomoea purpurea L.). Iran. J. Plant Prot. Res, 2022, 36, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

Table 1.

Summary of seed traits and germination ecology of three Ipomoea species.

Table 1.

Summary of seed traits and germination ecology of three Ipomoea species.

| Species |

Ipomoea lacunosa |

Ipomoea hederacea |

Ipomoea purpurea |

| Seed dormancy type |

Physical dormancy imposed by impermeable palisade layer [10,11] |

Physical dormancy with additional physiological inhibition in some seeds. |

Physical dormancy [37,39] |

| Seed-coat anatomy |

Thick palisade layer; lens–hilum region functions as a water gap [10,11] |

Palisade macrosclereids; lens region acts as water gap [10,12] |

Hard seed coat, thick, wedge-shaped testa [37,39] |

| Dormancy-release |

• Warm temperatures increase lens sensitivity and promote dormancy release. [10,11]

• Alternating temperatures accelerate release after after-ripening [13]

•Hydration–dehydration cycles induce structural weakening of palisade layer [12]

•Long-term burial weakens seed coat [26]

• Sensitivity cycling documented [12] |

• Warm temperatures enhance lens responsiveness to moisture [10,12]

• Hydration–dehydration cycles promote lens loosening [12]

• Dry after-ripening increases germination [12,23] |

• Dry after-ripening reduces dormancy, widening the germinable temperature range [37]

• Scarification enables immediate high germination across temperatures [37,39]

Chemical scarification (H₂SO₄) markedly increases germination [36]

• Alternating temperatures enhance germination in after-ripened seeds [37]

• Dormancy level decreases over dry storage time [37] |

| Temperature requirements |

Germination peaks at 20–25 °C after after-ripening or scarification (constant or alternating 25/15 °C) [2,13] |

Optimum 20–25 °C; strong response to alternating 15/25 °C (~94% germination) [27] |

Base 7–8 °C; optimum 23–30 °C; maximum ~39–40 °C. Narrow 15–25 °C range at dispersal, expanding to 10–40 °C after 6 months dry storage [37,39] |

| Light requirements |

Emerges under very low R:FR (<0.1) in soybean [38] |

No information |

Light is not required; similar germination occurs in both light and dark [37,39] |

| Moisture / Water potential |

Saturated soils delay dormancy release rather than germination [24] |

No information |

Quantitative thresholds:

~80–90% at 0.0 MPa;

~60% at −0.2 MPa;

~30–40% at −0.4 MPa;

<10% at −0.6 MPa;

0% at −0.8 MPa [39] |

| Seasonal emergence patterns |

Early to midsummer; prolonged emergence in no-till due to surface conditions [13,14] |

Slightly later emergence than I. lacunosa; continues into mid-season [14,38] |

Extended cohorts across spring–early summer; high plasticity [35,37] |

| Seed longevity evidence |

Long-term viability ≥39 years [9] |

High viability in storage for multiple years; field data show persistence [23] |

No information |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).