Introduction

Access to safe drinking water is a significant development issue; central to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the 2030 Agenda, and a fundamental human right recognised by the UN in 2010. Recent data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF reveals an alarming situation in Africa: in 2022, approximately 418 million people on the continent lacked a basic drinking water service. To this can be added 779 million people who lacked basic sanitation services and 839 million without basic hygiene services (Bello, 2024). These figures underscore the urgency of the situation, even though the access to safe drinking water rate in rural areas in Senegal increased from 56% in 2010 to 96.9% in 2022 (CPCSP/MEA, 2024). These statistics, however, hide a complex and nuanced reality, where service quality and economic viability remain major challenges. Many have access to a drinking water point through a public drinking fountain (located within a 30-minute round trip from where they live), others have to make do with groundwater (wells) or surface water (rivers, ponds, etc.) that is unsafe to drink (Diouf et al., 2024). In this context and with the aim of improving access to drinking water conditions, water governance policy actors have undertaken multiple reforms. Consequently, profound changes have been undergone by the sector, moving from centralised public management to service delegation first to community organisations and then to the private sector. If these reforms are officially aimed at improving technical performance and financial viability, their actual impacts on the ground, particularly in rural areas, remain complex and controversial.

In this context, the core issue of this research is to analyse water governance dynamics in the Senegalese rural milieu through the prism of the concept of "disconnection" used in the socio-economic and socio-political field of water studies (Baron & Héloïse, 2023). The major challenge of water governance lies in the local appropriation of the issues, whereas political decisions remain centralised at the state level (Baron & Maillefert, 2021). Regional agencies, responsible for implementing these policies, lack the resources to play their role as intermediaries between users and operators. The latest water reform, enacted in 2014 and led by OFOR (Rural Boreholes Agency), raises questions about its relevance and effectiveness. In practice, communities often face standardised services that do not always meet their specific needs. We position ourselves within the fields of social sciences of public action and hydrosocial geography (Swyngedouw, 2004). Our approach follows in the footsteps of the analyses by Baron and Héloïse (2023). These authors show that the link between resource protection and access to safe water remains fragile, as it depends on institutional mechanisms that are rarely coordinated. We extend this framework by focusing not only on infrastructure and services, but especially on actor coordination and governance processes. Our analysis is based on the idea that these multiple disconnections compromise the achievement of equity and sustainability objectives, making access to drinking water more precarious for the most vulnerable communities. The Senegalese situation, therefore, illustrates a structural tension between financial sustainability and social equity, a debate already widely highlighted in the literature on essential services in sub-Saharan Africa (Jaglin, 2005; Baron & Bonnassieux, 2011).

The purpose of this article is to analyse how service delegation, far from providing a solution to water governance difficulties, has contributed to shifting and sometimes exacerbating certain structural tensions. To do this, we first mobilise the theoretical framework of disconnection and demonstrate its relevance in the Senegalese context. We then present the results of the field survey, which highlight both the dynamics among institutional actors, the transformations of governance in rural areas, and the adaptation strategies implemented by inhabitants in response to the changes induced by the reform. Finally, the discussion contrasts these findings with insights from the scientific literature to draw out the theoretical implications of disconnection and to open avenues for rethinking water governance from a more inclusive and resilient perspective.

1. Water governance analysis framework: an approach based on disconnection, fragmentation, and mismatch

To analyze the challenges of water governance in Senegalese countryside, this study relies on a theoretical framework that goes beyond infrastructure analysis to focus on the dynamics of coordination between actors. The approach is based on the concept of the hydrosocial system and hydrosocial territories (Boelens et al., 2016). Water is taken not only as a physical resource but also as a social, political, and institutional construct (Budds & Linton, 2014). By extending the work of Baron and Héloïse (2023), we take up again the notion of "disconnection," placed at the heart of the observed tensions. This perspective helps understand how institutional fragmentation, technical weaknesses, and market model shocks undermine the connection between resource preservation and equitable access to safe water. Eventually, it encourages us to consider solutions capable of equitably linking together resource protection and universal access to drinking water, in line with the reflections of Jaglin (2005, 2012) and Baechler (2012) on hybrid models and Ostrom (1990) on the collective governance of common-pool resources.

1.1. Institutional Fragmentation: An Interpretation Through Disconnection

Institutional fragmentation is a productive approach for analyzing the limits of water governance. As shown by Baron and Héloïse (2023), the disconnection between access to safe water and resource protection is largely explained by a sectoral split of responsibilities. This interpretation follows in line with the analyses of Lascoumes (1994) on power relations and influence dynamics in environmental policies, and those of Olivier de Sardan (2021) on bureaucratic compartmentalization, or "bureaucratic-state governance," which weakens the effectiveness of public action. It also reaches the same conclusions as Barraqué (2008) and Baron and Valette (2023) as far as the limits of overly segmented governance are concerned. In the rural areas of Senegal, and more specifically in the Senegal River Delta, this fragmentation results in a "disjointed actor system." OFOR, the state entity responsible for managing and planning the rural hydraulic system, is failing to adequately modernize and improve the sector. Operational management is delegated to private operators, such as the SEOH on the Gorom-Lampsar axis, which is connected to OFOR through an operating agreement. These operators are charged with producing and distributing drinking water, but develop no linkage with OLAC, which could provide support or information on the quality of surface water, the main source of raw water for the treatment plants managed by SEOH. A better connection with OLAC would allow these operators to capitalize on available data and improve their knowledge of water treatment.

The hydraulic system thus operates in silos: each entity acts in isolation, without synergy or fluid circulation of information. We qualify this voluntary or involuntary withholding of crucial information between interdependent actors as information load shedding. By keeping information within their own sphere, institutions create a systemic gap that weakens the governance chain. Baron and Héloïse (2023) define articulation as the way in which environmental issues related to resource preservation and access to drinking water for the greatest number are mutually considered within a systemic vision.

We also see institutional fragmentation in the technical control systems. OFOR, represented at the regional level by the DRH for monitoring and coordinating private and community operators, suffers from a chronic shortage of staff and logistical means. This situation, combined with the remoteness of the water treatment plants, makes it difficult to provide reactive monitoring and quickly resolve user-expressed needs. The analysis of safe water quality is largely entrusted to the SAED laboratory, located in Saint-Louis, which is far from several treatment plants. This arrangement highlights the spatial and organizational limits of surveillance. What is more, the control mission should be supported by the Ministry of Health, which is nevertheless absent from OFOR's supervisory bodies, as well as by the water police of OLAC, which remains largely inoperative owing to a lack of resources. The water police, supposed to prevent pollution and unsanitary conditions, remains inactive due to a lack of logistical and human capital.

This deficit in shared responsibilities widens the gap between centralized decisions and on-the-ground realities. It further illustrates the disconnection (Baron & Héloïse, 2023) between the institutional logic of regulation and the actual capacity of stakeholders to guarantee safe and accessible drinking water. For example, decisions are made at the central level and then imposed on implementing structures (SEOH, OLAC, DRH), with no possibility for negotiation with local actors or donors. This lack of institutional autonomy results in rigid public action: each structure remains confined to its exclusive mandate, preventing the implementation of cross-cutting solutions adapted to local realities.

This conception of water policy, which can be described as "bureaucratic-state governance" using Olivier de Sardan's (2021) term, is one of the causes of unequal access to drinking water due to the profound crisis in the public services responsible for implementing it. We refer to this as "governance inertia" to highlight the slowness and difficulties in deploying responses tailored to local needs. Even when political will is declared, the scarcity of human and financial resources, combined with the siloing of responsibilities, slows down governance and traps it in its own contradictions. In doing so, actors prioritize a "technical" vision, in terms of "performance indicators that cover the environmental, economic, and social dimensions" (Canneva and Guérin-Schneider, 2011: 1, cited by Baron and Héloïse, 2023).

The state and its regional structures must play a crucial role in achieving water security in rural areas. Developing policies and strict standards is not enough; it is also important to provide more financial and technical support to local operators and regional structures to ensure compliance. They are also responsible for coordinating efforts between local authorities, NGOs, and health professionals, as well as for conducting awareness campaigns on the risks associated with unsafe water and for intervening quickly in case of a crisis.

1.2. Disconnect between economic and socio-organizational logics

The delegation of water service to private operators, such as SEOH or SDER, is based on a profit-driven logic and technical efficiency. To cover their investments and operating costs, these operators apply a tariff intended to reflect the "true cost" of water (May, 2023 ; Jaglin, 2005). And yet, this model is directly disconnected from the low purchasing power of rural populations. On the one hand, the lack of sufficient subsidies leads to high pricing, making water unaffordable for many households (Diouf et al., 2024). As Bakker (2003) pointed out, privatization and service delegation policies tend to intensify social inequalities, particularly in fragile territories.

On the other hand, the structural rigidity of the private model allows for no adjustment faced with fluctuations in consumers' income (Breuil, 2004). Disconnections for non-payment then appear as a systemic consequence. They not only increase the marginalization of already vulnerable groups (Barrau & Clement, 2010) but also force the latter to turn to unsafe water sources, thereby canceling out the health benefits of the reform (Diouf et al., 2024). This "informal exit" is not a simple deviance but a rational economic response that reinforces the disconnection between the formal service and users' actual practices. Swyngedouw (2004) and Satterthwaite (2014) have also highlighted this type of contradiction, showing how essential services become vectors of inequality in precarious contexts.

If the private model reveals its limits, other experiences, particularly those of the ASUREP (Associations of Users of Drinking Water Networks), offer an illuminating contrast. These structures embody a form of proximity governance, better adapted to local social and economic realities. ASUREPs are distinguished by their capacity for adaptation. Managed by and for the communities, they implement solidarity-based strategies and flexible collection practices (Diop & Dia, 2011). This flexibility avoids the exclusion of households in struggle. They also embody a collective approach: the users, being also actors in the management, take part in a participatory and adaptive governance. This proximity fosters dialogue, builds trust, and facilitates continuous adjustments. In contrast, the private model relies on a rigid top-down structure and a hierarchy distant from local realities. We can relate this local associative management model to the work of Elinor Ostrom (1990) on common-pool resources, as well as to the analyses of Baron (2003) and Jaglin (2012) on the hybridization of governance models in the Global South. The literature on collaborative governance and public policy analysis (Edelenbos & Teisman, 2011) also insists on the importance of coordination between actors for the coherence of interventions and the effectiveness of policies. In the Senegalese rural context, the absence of clear coordination mechanisms between the state, private operators, and local associations leads to underserved areas and a sense of loss and injustice among the population.

It should be emphasized that the reform based on private delegation, however, despite its potential technical efficiency, suffers from a fundamental disconnection. On the one hand, a rigid economic model, structured around a profitability logic but insensitive to social realities. On the other hand, a need for adaptive governance, rooted in local practices and solidarities. This systemic tension reveals that the incompatibility between market logic and social imperatives can compromise the goal of equitable and universal access to water. As Linton (2013) reminds us, the concept of "modern water" highlights that reducing water to a mere commodity obscures its social and political dimensions, which are nonetheless essential to the sustainability of water services.

2. Methodology and data collection

2.1. Study Area

The research was conducted in the Gorom-Lampsar area, situated in the Senegal River Delta, within the Saint-Louis Region. This area is situated between 16° and 16°30 north latitude and 16° and 16°30 west longitude. Gorom-Lampsar’s population territory is estimated to be approximately 60,000 inhabitants, with a population density of 13.7 inhabitants per km² and areas of high human concentration are located along National Route 2 (Faye, 1996). It represents an emblematic space of the socio-spatial contrasts of the Senegal River Delta within the 86 kilometres. The delta begins in the lower valley, near the town of Dagana, and extends to the river mouth (the city of Saint Louis). Covering an area of 4,343 km², it forms a distinct region in relation to the Upper, Middle, and Lower Valleys, both in terms of its natural environment and its development (Dione, 2014). It is drained by two distributaries of the river, namely the Gorom, the Lampsar, the Djeuss, the Kassack, the Djoudj, the Ngalam, and the “Three Marigots”. These distributaries not only supply the deltaic lands, composed of a mosaic of low-lying wetlands separated by a few dune fields, but also constitute the main sources of water for the populations, agriculture, and the livestock sector as well. Fishing is also practiced there.

Ethnic and socio-professional distributions appear to follow a tropism towards the hydraulic axes. The Wolof majority (60% of the population) is concentrated in the large towns along the Gorom-Lampsar axis; this population is primarily engaged in agriculture. The Fulani (35%) and Moors (4%) are mainly located in the Djeuss valley and are predominantly herders and farmers (Diouf, 2024).

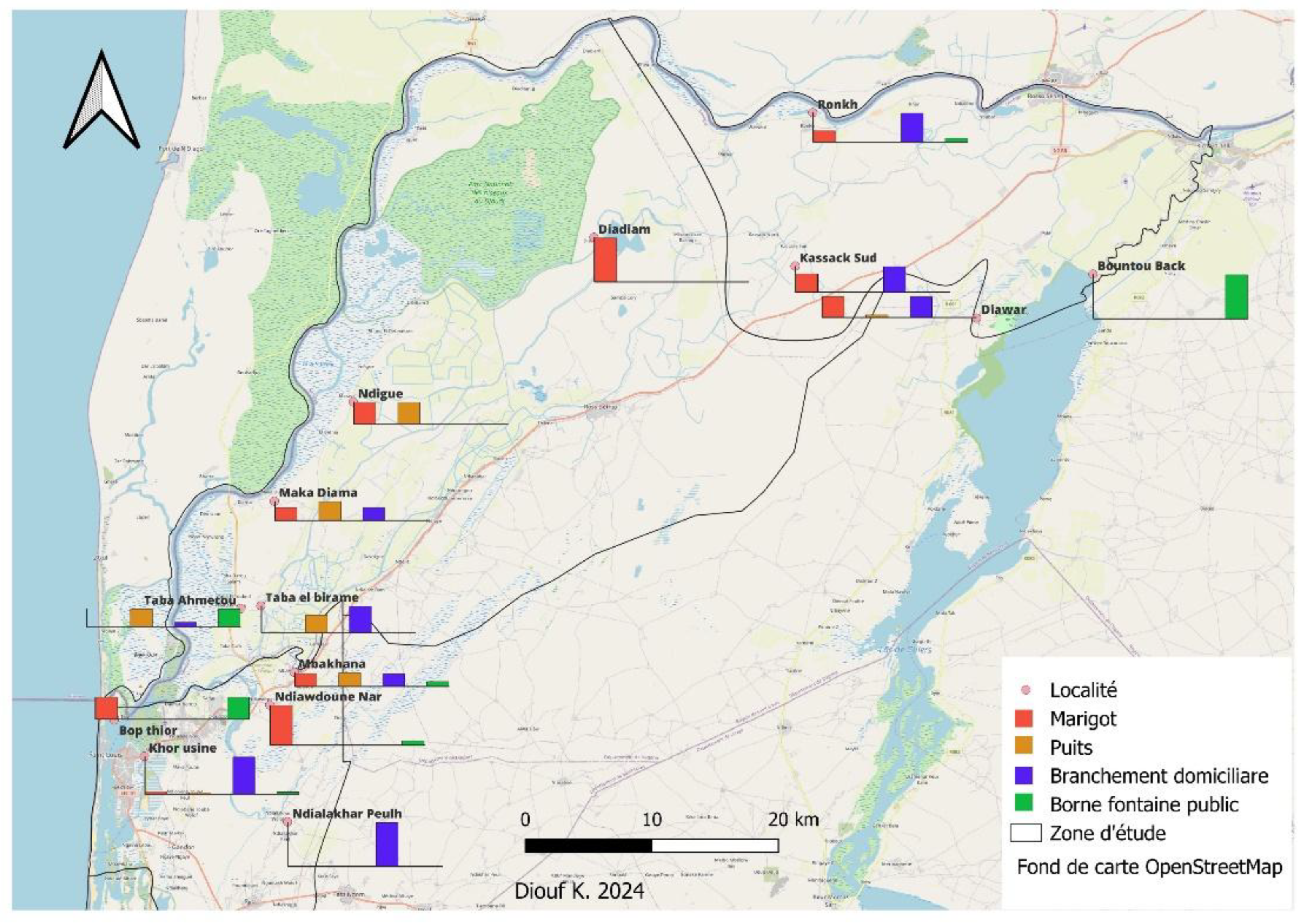

In this zone, fourteen localities were studied (see Map 2). The choice is justified by a central paradox: although the area possesses significant surface water resources (rivers, streams, and waterways), the local population always finds it difficult to access drinking water. This contradiction, revealing the gap between water potential and effective supply, is central to the research. In localities such as Diadaim, Kheune, or Kassack, limited accessibility is observed, including not only the road network but also the absence of public transport connecting the different villages. The precarious state of the roads, lack of public transportation, the weakness of power grids, and the neglect of social services (health, education) increase physical and economic isolation. These conditions compromise equitable access to development opportunities and reinforce the vulnerability of rural populations. Thus, Gorom-Lampsar constitutes a study area that mirrors the structural inequalities and development challenges in Senegal.

Map 1.

Location of the Saint-Louis region of Senegal.

Map 1.

Location of the Saint-Louis region of Senegal.

Map 2.

Location of the study area (the Gorom-Lampsar axis) in the Saint-Louis region.

Map 2.

Location of the study area (the Gorom-Lampsar axis) in the Saint-Louis region.

2.2. Tools and Methods

The methodological approach is mixed and combines qualitative and quantitative methods. This approach allows for the cross-referencing of different types of data and strengthens the validity of the results by avoiding biases associated with using a single source of information.

A quantitative survey was conducted in 2022 with 171 households spread across 14 localities in the study area. For data collection, the KoboToolbox platform was used, making it possible for responses to be recorded directly via tablets. This approach enabled quick data collection while minimizing the risk of errors associated with transcription. The questionnaire focused on water consumption, the relationship with distribution services, households' self-reported standard of living, and supply strategies. The data were then processed to establish correlations between socio-economic indicators and the utilization of alternative water supplies.

In addition to the quantitative survey, a qualitative survey was conducted between March and May 2022 and February and March 2023. It involved 15 semi-structured interviews with a panel of key stakeholders: representatives from structures such as OFOR, OLAC, ARD, members of user associations, etc. These interviews made it possible to explore perceptions related to governance changes, gather narratives of lived experiences, and understand the motivations behind policy decisions as well as community adaptation strategies. The qualitative data analysis was performed using Maxqda software, allowing for a thematic analysis and the highlighting of key arguments.

This combination of methods enabled data triangulation, meaning the cross-referencing of information from questionnaires, interviews, and observations. This approach strengthened the validity of the results and allowed for a more holistic understanding of the dynamics of drinking water governance in the studied environment.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Institutional Actors and Their Interactions

As highlighted in the theoretical framework, water governance cannot be reduced to infrastructure or services: it is understood through the dynamics of coordination between actors, institutional fragmentation, and phenomena of disconnection (Baron & Héloïse, 2023). This perspective highlights how the State centralized choices and the shared responsibilities between different structures can bring about tensions and inefficiencies on the ground. From this viewpoint, we examine how OFOR, represented locally by DRH, collaborates with other institutions such as ARD, OLAC, and associated NGOs.

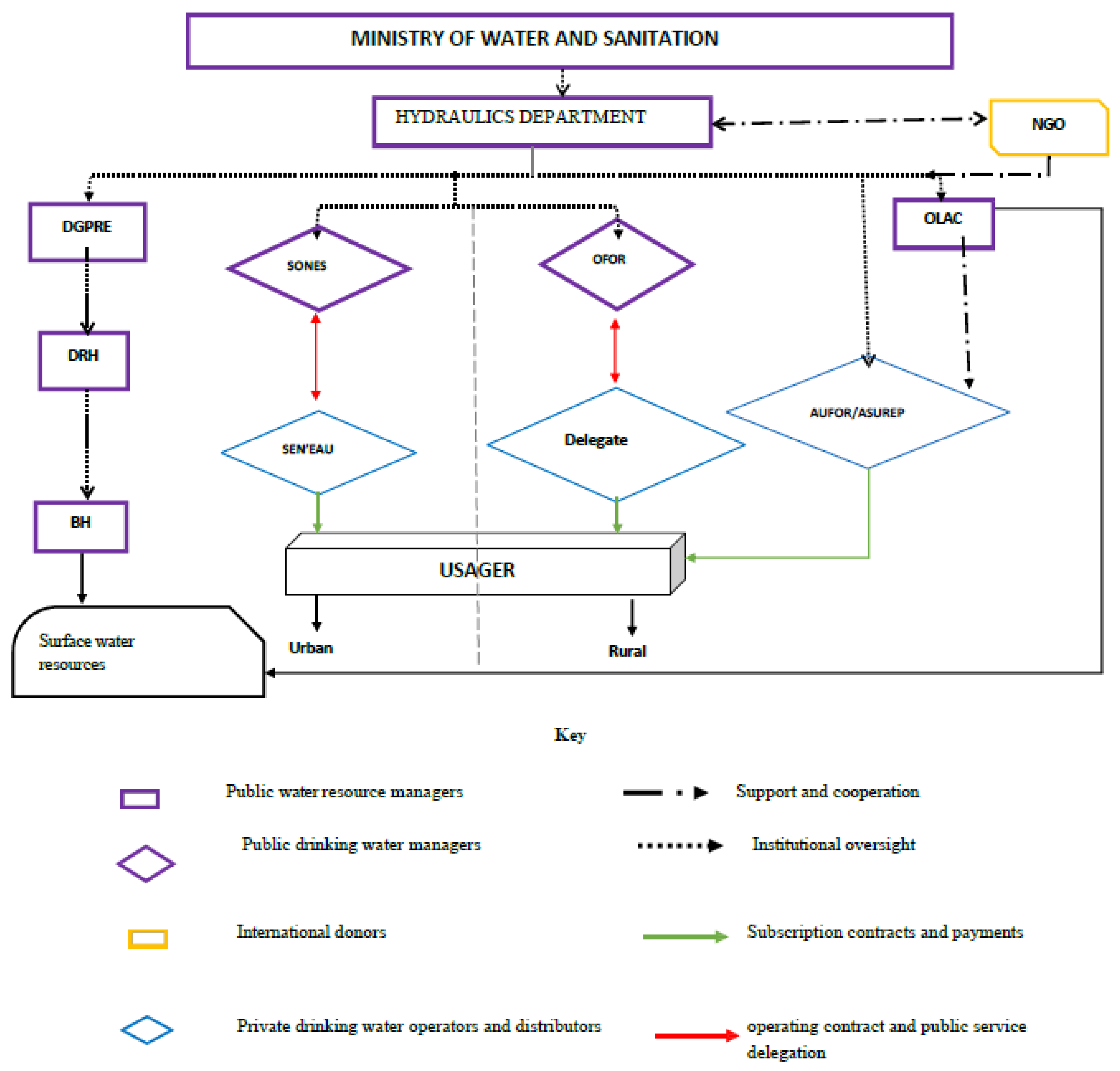

The water infrastructure system in Senegal is based on a complex architecture of public and private actors, each with a specific role in the management and distribution of water (see diagram below). At the top, the Ministry of Water and Sanitation (MEA) oversees the entire sector via the Directorate of Water Resources, defining national policies and strategic orientations. For water resources management, the DGPRE focuses on defining and implementing national policies for water resources management. At the same time, OLAC (a public industrial and commercial establishment) is involved in the development, monitoring, and protection of water bodies and the country's inland lakes and rivers. As for the OMVS, it is an international organization comprising the four countries that share the Senegal River, and the decisions of which escape the direct control of local actors and officials. OFOR is a public industrial and commercial establishment (EPIC) under the technical supervision of the MEA and the financial supervision of the ministry in charge of finance. It is an ex-officio member of the monitoring committee, control, provisional and final acceptance of works, and is responsible for the rehabilitation, renewal, and strengthening of existing rural water infrastructure assets.

Furthermore, ARD appears to occupy an interesting position in governance, with the close monitoring of equipment projects implemented by NGOs such as GRET. However, collaborations between these structures (DRH, OLAC, etc.) and the Saint-Louis ARD are somewhat difficult, often hampered by different prerogatives. In other words, ARD, as a decentralized structure, has autonomy that allows it to act according to specific local needs, work with NGOs, and fund projects in areas such as water, education, agriculture, health, etc. NGOs often provide funding, technical expertise, and additional resources, whereas ARD provides logistical support and alignment with regional priorities. For the provision of drinking water, the distribution is geographically differentiated. In urban areas, SONES delegates distribution to SENEAU, a private operator, which manages the direct relationship with subscribers and service quality. In rural areas, OFOR delegates management to private operators (SEOH, SDER) responsible for producing and distributing water under OFOR's supervision. In rural areas, community actors (AUFOR/ASUREP) also play a role similar to that of private operators (delegated service operators). However, these community actors are being gradually phased out since the 2014 reform (Law 2014-13). This configuration shows that each actor (see

Figure 1) has specific missions, but they depend on each other to ensure water access and resource preservation.

However, under the purview of different administrative authorities and not always having the same prerogatives, these actors do not maintain genuine cooperative relationships and tend to operate in a fragmented manner. For example, an entity like the Human Resources Department (DRH), which is directly subordinate to the central government, must comply with more rigid national directives: "These state agencies do not have the right to negotiate with donors," stated one of our contacts at the Regional Development Agency. Yet, building teamwork between these organizations with different responsibilities could, for instance, help improve the local management of OFOR, the national structure responsible for rural water management, which is often consequently far removed from on-the-ground realities.

Moreover, OFOR faces various internal challenges, including limited staff, insufficient equipment, a lack of a clear vision for its functions, and a general lack of dynamism. This situation hinders OFOR's ability to identify shortcomings in the work of private or community operators in the field and to learn from them. In addition, these decentralized structures at the regional level do not have decision-making power regarding water services.

According to our fieldwork in 2023, OLAC conducts regular quality monitoring for raw water from rivers and nationally significant resources, particularly Lake of ‘‘Guiers”, which supplies Dakar and its outskirts. In the Gorom-Lampsar area, the Laboratory (OLAC) is unable to regularly ensure the monitoring of raw water quality due to a lack of financial resources. This funding gap compromises the execution of sampling campaigns and laboratory analyses.

The environmental inequality constituted by a lack of a drinking water network is thus accompanied by an ecological inequality (Durand & Jaglin, 2012), namely the pollution of the waterway by various activities, including domestic wastewater and, predominantly, agribusinesses in the watershed. It is necessary for the decentralized state services in charge of quality monitoring to maximize the control of anthropogenic pollution and enforce the treatment of agricultural wastewater before it is discharged into the river; the water police function is not implemented on the ground by the Laboratory (OLAC) due to a lack of means. It also appears that the raw water analysis data from this structure are not shared with the managers responsible for drinking water treatment. This situation, common among Senegalese agencies, creates difficulties, as access to necessary data is often limited. Regarding information sharing, confidentiality should not hinder the essential cooperation between different stakeholders to ensure optimal water quality management. Sharing this data would allow the latter to gain an initial understanding of water quality, its seasonal and annual fluctuations, as well as long-term trends.

Despite the presence of diverse and specialized actors, the Senegalese water system remains marked by institutional fragmentation that limits its ability to effectively meet user needs. The growing number of responsibilities, the compartmentalization between resource management and water supply, as well as the dependence on external funding, exacerbate tensions between technical objectives, economic constraints, and social demands. This situation underscores the need for better coordination, strengthened institutional oversight, and clear articulation between actors to guarantee equitable and sustainable access to water.

3.2. Analysis of Changes in Drinking Water Governance in Rural Areas

Drinking water governance has experienced a profound transformation, marked by a paradigm shift: the move from a community-based management model to a delegated management model relying on Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs). Historically, water supply in rural areas was ensured by local structures such as Borehole User Associations (ASUFOR) and Drinking Water User Associations (ASUREP). The transition to the current private model is the result of a series of successive reforms.

The first reform, called the Rural Borehole Management Reform (REGEFOR) in 1996, formalized the creation of ASUFORs and ASUREPs to replace traditional management committees. The next step, in 2014, was marked by the creation of the Office for Rural Boreholes (OFOR), tasked with taking over the missions of the former technical services of the Ministry of Hydraulics (notably the Directorate of Operation and Maintenance - DEM) as well as a large part of village organizations. This new framework paved the way for greater private sector involvement. From 2015, OFOR began awarding lease contracts, following international invitation to tender, to private operators such as SEOH in the Gorom Lampsar area. In the same spirit, the Senegalese Water Company (SDE), which had been the delegated manager for urban water distribution since 1996, saw the emergence of a subsidiary dedicated to rural areas, the Senegalese Rural Water Company (SDER), which took over water management in certain regions like Louga and Matam starting in 2023. These user associations (ASUFOR and ASUREP) embodied principles of proximity, community solidarity, and consideration of local specificities, ensuring both the operation and maintenance of water infrastructure (Olivier de Sardan & Dagobi, 2000).

However, a main consequence of this institutional transformation has been the marginalization of local actors and the devaluation of their expertise. These user associations (ASUFOR and ASUREP) also carried values of solidarity and proximity. They thus helped maintain a fragile balance between financial sustainability and social equity, sometimes adjusting tariffs according to households' payment capacity. For example, ASUREPs sometimes contributed financially to various activities organized in their localities, such as football tournaments, religious ceremonies ("gamou"), etc.: "we help them by giving money for the school, for a ceremony [...] we help villagers build morgues, mosques, and during the independence holiday we receive letters requesting financial support," testified a former ASUREP official from Lampsar.

Furthermore, the expertise acquired over time by ASUFOR and ASUREP managers, based on an intimate knowledge of the technical networks and local social dynamics, has been poorly recognized within the framework of professionalization required by the new model.

The considerable commitment of these associations is also evidenced by their lack of a fixed salary, limited to an annual allowance. For example, the ASUREP of South Kassack receives an annual percentage of 5% of the budget from water sales. The members of the executive board are simply elected members. As for the technicians who operate the water treatment plants, they receive low wages and often struggle to maintain a decent standard of living. This sometimes forces them to seek additional work, in agriculture or construction for example, to secure extra income and meet their financial needs. For instance, South Kassack operator informed us that he is also a farmer because his technician's salary is insufficient to meet all his needs: "I have a monthly salary of 50,000 CFA francs (76 euros), I will not have a pension, and there is a health risk due to my direct contact with chemicals without adequate protection." Moreover, the lack of proper equipment to protect themselves from the chemicals used in water treatment constitutes an additional constraint for these often highly committed actors.

The relationship of trust and the commitment to the well-being of local communities are essential elements for ensuring the sustainability of water services, going beyond mere financial considerations. According to Olivier de Sardan (2021), "Similarly, in Africa, it is the associative world (the 'civil society') that is credited with an innovative capacity, at least potentially." For many years, many are the authors who have emphasized that the excessive centralization of political decisions is a significant obstacle for African countries. According to Olivier de Sardan and Bierschenk (1993), the concentration of power at the top of the state stifles local political and economic initiatives, thereby hindering regional development. They go so far as to label these "Commando States" (Kommandostaat) (Elwert, 1990 cited by Olivier de Sardan and Bierschenk, 1993).

Would it not be wise to renew community management, but this time with better supervision? Is the adequate path between the fully privatized management model, on one hand, and the community model on the other, not rather the territorialization of public policies, so as to entrust the sector to local elected officials (mayors), who would then supervise the ASUREPs’ actions? All the more, "relying on one's own strength" is not absurd or incongruous and does not necessarily express any kind of isolationism. It can simply mean encouraging initiative and reforms from within, within state services, municipalities, or local associations (Olivier de Sardan, 2021). Drinking water network user associations, supervised by Mayors, could ensure technical, logistical, and financial follow-up and allow for an adapted operation of the water service in rural areas, ensuring its sustainability.

3.3. Strategies for Community Adaptation and Resilience in Water Access

In the face of inadequacies in the drinking water service, often characterized by high cost and intermittent supply, the local populations do not remain passive. On the contrary, they develop adaptation and survival strategies that reveal both their vulnerability and their capacity for resilience. These strategies are based on three main dynamics: the use of alternative water sources, the emergence of an informal water market, and the persistence of community-based management practices in some areas.

In the localities of Gorom Lampsar, the target population consists mostly of middle-class and low-income households, dependent on agricultural incomes and without state allowances. Here, the existence of a drinking water network does not guarantee access for all. Not all residents can have a home connection due to a lack of means to pay the connection fees. Purchasing water from public taps is even more expensive and tiring, which places a particular burden on large families. For example, water collected per concession (a house grouping several households) represents on average eight basins per day for a set of monogamous and polygamous households. Most concessions bring together members of the same extended family: the head of the family and his children, and the latter with their respective wives and children.

Figure 2.

Respondents' self-assessed standard of living from the questionnaire (2022, K. Diouf).

Figure 2.

Respondents' self-assessed standard of living from the questionnaire (2022, K. Diouf).

Surveys show that 51% of households consider themselves to have a medium standard of living, 46% as poor, and only 3% as rich. This socio-economic indicator, albeit self-reported, helps clarify the distribution of choices and constraints regarding sources of drinking water. The bottled water market is growing, primarily benefiting wealthier consumers, while the majority of middle- or low-income households turn to "free," non-potable sources, such as wells or rivers, for their domestic water needs. In rural areas, especially with high birth rates, one must have a high income to afford bottled water, since 10 liters cost 1,000 FCFA: a sum 100 times higher than the price per cubic meter of water from public taps, which is already expensive for most households. The low standard of living is one of the factors driving the use of "free," non-potable water sources (wells or rivers), as shown in Map 3. The latter illustrates the relationship between the socio-economic levels of the surveyed population and the frequency of well water usage.

Map 3.

Highlighting standard of living and the use of well water based on household questionnaire responses (K. Diouf, 2022).

Map 3.

Highlighting standard of living and the use of well water based on household questionnaire responses (K. Diouf, 2022).

Map 3 is based on two standard of living categories (low and medium) and assumes that wealthy residents do not use wells. Most localities, 9 out of 14, have a low proportion of their population using well water (0-6%), while some, such as Mbakhana and Taba Ametou, have a high proportion (40-50%). The map shows that in villages like Bountou Back and Ndialakhar, the target populations have a low standard of living, but the frequency of well water usage is zero. This is also seen in other localities such as Khor Usine, Kassack Sud, Ronkh, and Diadiam, which can be explained by the absence of wells in these areas, but especially by the presence of nearby river water resources or reserves.

Photo 1.

Domestic well, Taba Ahmetou (Diama municipality) (K. Diouf, field survey, 2022).

Photo 1.

Domestic well, Taba Ahmetou (Diama municipality) (K. Diouf, field survey, 2022).

The use of alternative water sources depends not only on household size but also on billing methods and the absence of social pricing. Purchasing water from public standpipes can cost up to 1,250 FCFA per cubic meter, excluding transportation costs, which leads to high monthly expenses, often exceeding the local minimum wage (SMIC) for a five-person household. This situation highlights the economic vulnerability of households and the disconnection between the cost of water services and users' actual ability to afford them.

Carte 4.

Different water sources used in the study area, based on survey responses (K. Diouf, field survey, 2022).

Carte 4.

Different water sources used in the study area, based on survey responses (K. Diouf, field survey, 2022).

This map shows the distribution of the different water sources used in the study area, particularly wells, rivers, public standpipes, and household connections. Free water sources are widely used for domestic needs, with the exception of direct consumption without prior treatment. The quality of this water remains problematic, as agricultural and domestic pollution make it a potential vector for waterborne diseases.

However, it would be pertinent for the government to develop a harmonized pricing strategy for laboratory water analysis and support the operators in this mission. In this regard, the Mayor of Ronkh, a commune in the northern part of the surveyed territory, raises the question: “how to drink quality water at a lower cost?”. This local official also encourages his counterparts to raise awareness among the population, so that they stop polluting surface water, as well as using raw water directly, especially for drinking.

3.4. Outcomes of the Reform and the Public Service Delegation

Since the introduction of private operators, initial feedback has been viewed positively by the Office of Rural Drilling (OFOR). According to one interviewee, "We conduct satisfaction surveys to get an idea of the users' perception level regarding the service provided by the operator, and the feedback is positive." "There is performance monitoring because the lease contract includes performance indicators that are tracked to monitor the operator's performance on water quality, service quality, and reaction time in case of breakdown," according to one of our contacts at OFOR. OFOR has observed two major improvements: the standardization of water tariffs and a clear increase in professionalism in service delivery. It is acknowledged that private operators generally possess strong initial capacity to manage public water services, based on their technical expertise, service management, and financial capacity.

However, this performance diminishes over time, notably due to funding difficulties for expanding services. Furthermore, non-compliance with specifications often linked to a lack of control and monitoring, compromises service quality over time.

Shortcomings in the monitoring of providers were raised during our interviews in 2023, as highlighted by one of our interlocutors: "In the Matam region, newly installed hydraulic systems are temporarily managed by agents, entrepreneurs, who know nothing about water management, winning contracts (for five systems). One thing is sure: these people, due to their lack of competence, will have to hire locals to manage the systems." This observation again illustrates the disconnection between institutional objectives and operational practices, as well as the fragility of the link between central supervision and local management. This lack of monitoring also highlights the persistent fragmentation and the inadequacy of the on-the-ground reality checks.

Admittedly, OFOR states that it is satisfied with the work of the private delegates and also receives monthly reports from them. However, we did not have access to these reports to verify the conformity of OFOR's statements with the situation on the ground. This, moreover, underscores the need for internal control to guarantee the reliability and transparency of information. For instance, OFOR claims that these private managers show great competence in administrative, logistical, and financial matters, thus surpassing the ASUREPs. It is revealed by our fieldwork observations that private enterprises’ technical competencies are mainly limited to senior managers, while the operational staff lacks adequate training. The assistant technician at the Mboubene station told us that he is a farmer and was recruited by SEOH to manage the service for the 11 villages connected to this water network on weekends. Thus, he has no specific qualifications for water treatment, a skill that is nonetheless essential for ensuring public health. He was trained on the job in an accelerated program and is starting to get used to his work, although he still encounters difficulties, particularly when the water turbidity is high. These observations show a discrepancy between official statements and field reality, raising questions about the level of professionalism actually sought by the state when replacing community management with private operators to improve the rural hydraulics sector.

The reasons for user complaints can be explained by service failures, which were voiced under the pretext of high water costs, even though the price of water was cut in half. Users experience water breakdowns and cuts, which, as we know, are still a reality even in urban areas where the service is considered to be better. Tested by inequalities in access to water and a lack of consideration compared to cities, these users are resentful. It is thus recognized that concerning stability and security: "Individuals who have experienced deficiencies in the past will react differently to the current satisfaction of these needs than those who have never suffered from a lack" (Maslow, 2008). According to Maslow (2008), human needs must be satisfied sequentially according to the "hierarchy of needs." When fundamental needs, like access to water, are not met despite high expectations, it can cause intense frustration. This frustration often translates into intolerance to service interruptions and water cuts due to non-payment of bills.

Furthermore, the specifications defined between the State and the concessionaires include a clause granting a long payment period to prevent water cuts for the population, which is not applied in the public-private water management contracts in Senegal. The lack of transparency and communication regarding the contract clauses can lead to distrust among residents. We can refer here to Herbert Simon's theory of "bounded rationality," which states that individuals make decisions based on their cognitive abilities and the information available to them. In our case, users may delay or avoid paying their water bills due to limited rationality, perhaps due to a lack of understanding of the long-term consequences or other pressing financial obligations. One of our interviewees considers the non-payment of bills to be deliberate, knowing that users prioritize covering other expenses, such as internet subscriptions, and that they adopt strategies of delaying or even omitting payment when it comes to settling their water bills. The analysis of these elements shows that the challenges and opportunities accompanying the delegation of the public water service require a holistic approach, integrating social, economic, and behavioral dimensions. To this must be added transparency in communication, which is essential for establishing good relations between users and the delegated operators, who are obliged to coexist until the end of the contract (2015-2025).

Nevertheless, it is still too early today to make definitive judgments about the results of this delegation of the public water service. We can only state that if the specifications are strictly followed, in accordance with what is stipulated for water pricing, the State can hope to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

4. Discussion

A complex landscape is revealed by the analysis of local practices for accessing drinking water, where institutional fragmentation (Lascoumes, 1994) and the disconnection between public actors, private operators, and local communities strongly influence the distribution and use of the resource. The transition to a Public Service Delegation (PSD) model has certainly led to a professionalization of services and a standardization of tariffs, but it has also marginalized local actors, such as ASUFOR and ASUREP, who historically represented the institutional memory and deep knowledge of the networks and community needs. Our results reveal that water governance in rural Senegal suffers from multiple disconnections that compromise the achievement of its objectives.

The transition from the community-based model (ASUFOR/ASUREP) to delegated management (SEOH, SDER) has marginalized local expertise in favor of technical-financial skills deemed superior. This disconnection of expertise is not merely a question of professionalization; it creates a rupture between the memory of community management and the new rational management (Olivier de Sardan & Dagobi, 2000). The know-how of the former managers, based on an intimate knowledge of the networks and social dynamics, is lost. As highlighted by Elinor Ostrom's work (1990) on the governance of common-pool resources, local communities are often better placed to develop adapted governance rules. By sidelining these actors, the reform produces a maladjustment that manifests itself as a lack of responsiveness and a loss of user trust.

This observation corroborates the thesis of Kamara and Ndiaye (2023), who criticize the rushed and "top-down" nature of the reform, emphasizing its disconnection from the reality of rural communities. By marginalizing local actors and disqualifying the empirical knowledge accumulated by ASUFOR and ASUREP managers, the reform broke a bond of trust that constituted a foundation for social cohesion (Diouf et al., 2024). However, as UNESCO (2023) reminds us, social cohesion is a crucial factor in determining development and security, particularly in vulnerable territories. The participation of local actors in all aspects of water governance projects, from design to evaluation and implementation (Bosredon & Dumont, 2021), should be encouraged and strengthened. According to Olivier de Sardan (2022), "the risk aversion within public services underscores the necessity of revising dominant bureaucratic practices. The lack of knowledge of local contexts, the disinterest of political elites, and the dependence on aid compromise the effectiveness of interventions. It is essential to value the expertise of local actors, who, despite innovations that are more contextualized, possess a precious capacity for innovation adapted to specific realities."

Admittedly, evidence in Senegal shows that not all user associations for boreholes (ASUFOR) and drinking water networks (ASUREP) have fully succeeded in fulfilling their public water service mission due to a lack of financial, logistical, managerial, and technical support, among other factors. However, this management model is nonetheless more attuned to the local level (Dione, 2014).

Recent developments in public action, particularly within state structures, present opportunities to rebuild weakened relationships between non-state actors and communities. Yet, these developments raise crucial questions about the need to re-establish mutual connections among private competition, political authority, and public action. Such reconnection is indispensable for the effective implementation of so-called “modern” management strategies (Berthet, 2008).

Furthermore, the tension between the "true cost" of water (May, 2023) and the low purchasing power of rural populations are confirmed by our observations. The rigidity of the private operator model, which leads to disconnections for non-payment conflicts with the social imperative of a universal and equitable access to water. The reform discourse, which promises efficiency and service for all, clashes with the exclusion mechanisms it generates itself. Olivier de Sardan's analyses of neoliberal governance argue that reducing water to a mere commodity obscures its essential social and political dimensions (Linton, 2013). In response, users adopt avoidance strategies, fueling an informal "exit" economy that weakens the entire system and reinforces distrust. The Senegalese situation thus illustrates a structural tension between financial sustainability and social equity, a tension already widely highlighted in the literature on essential services in sub-Saharan Africa (Jaglin, 2005 ; Baron & Bonnassieux, 2011).

In addition, the adaptive strategies of rural populations such as turning to alternative water sources or informal markets reflect both their vulnerability and their resilience. The widespread use of wells, rivers, or public fountains reveals that, despite the existence of distribution infrastructure, real access to drinking water remains conditioned by economic, social, and technical factors. This highlights the effective unavailability of water for part of the population and demonstrates how pricing policies can exacerbate inequalities in access, as noted by Diouf et al. (2024) in their work on water pricing and access.

Water quality, often compromised by agricultural and domestic pollution, constitutes an additional vector of health risks. It underscores the crucial role of the State and its decentralized structures in monitoring, control, and coordinating actions between private operators, local authorities, and communities. The absence of effective quality control mechanisms and communication around safety standards contributes to user distrust and accentuates the fragmentation of the governance system, as studied by Baron and Héloïse (2023).

This issue aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda. SDG 6 aims for universal access to clean water and adequate sanitation, which implies sound management and rigorous monitoring of water quality, just like SDG 13 on climate, as pollution is often aggravated by climate variability or SDG 15 on the preservation of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

In sum, the multiple disconnections observed demonstrate that the problem of water governance in rural Senegal is not merely technical or financial but profoundly systemic. Addressing these challenges requires more than reinforcing infrastructure or improving contracts; it necessitates rethinking the articulation among all actors. Strengthening this articulation through an integrated approach that combines technical expertise, local knowledge, and community participation in line with the work of Jaglin (2005, 2012), Olivier de Sardan and Dagobi (2000), and Bourdieu (1980) on habitus and social capital appears essential.

The challenges encountered demonstrate that PSD cannot achieve its sustainability and equity objectives without improved institutional coordination, transparent communication, and support policies that are genuinely adapted to local capacities (Lavigne Delville, 2018).