Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Adhesive Preparation

2.3. Adhesive Characterizations

2.3.1. Solids Content

2.3.2. Gelation Time

2.3.3. Viscosity

3. Results and Discussion

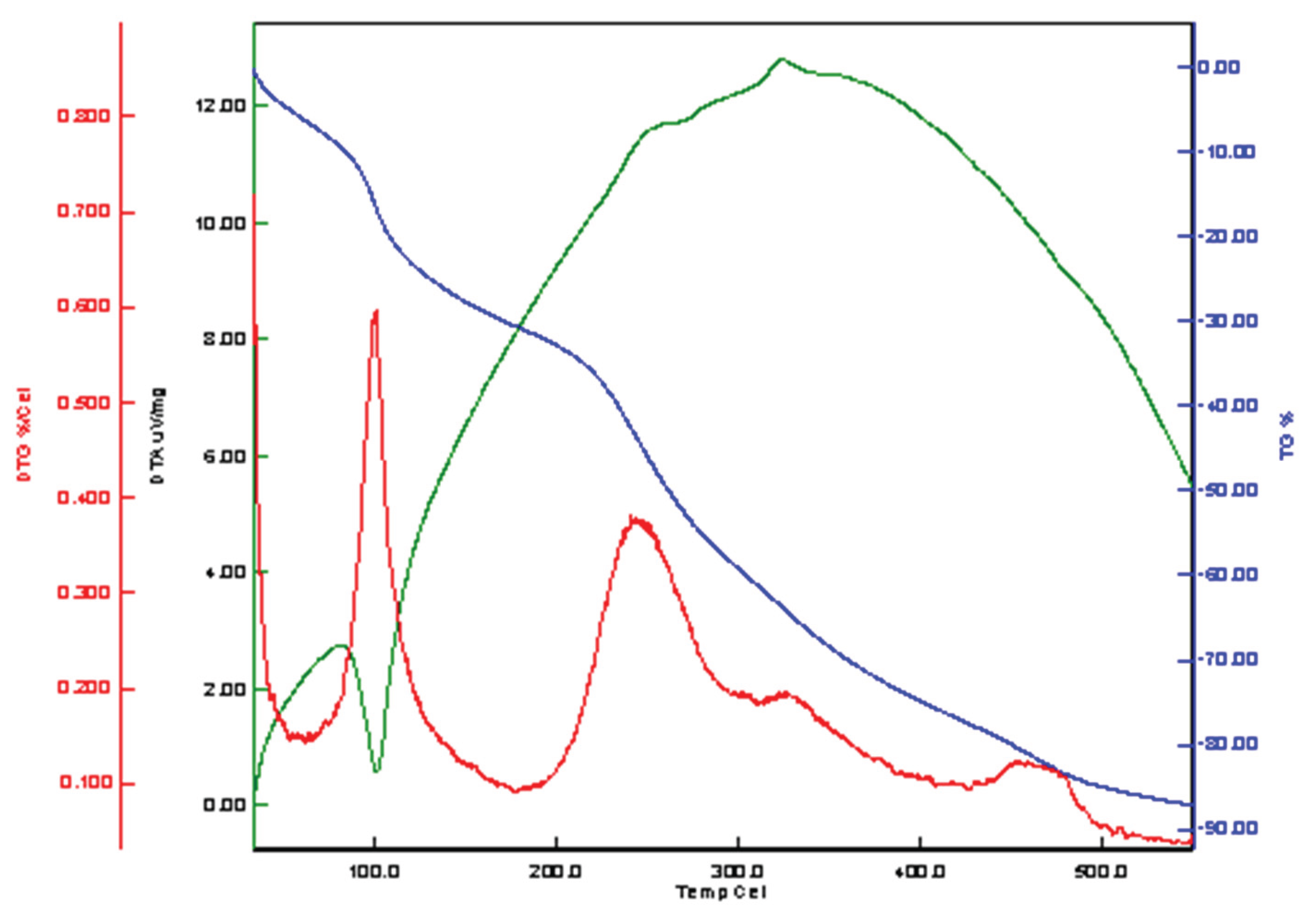

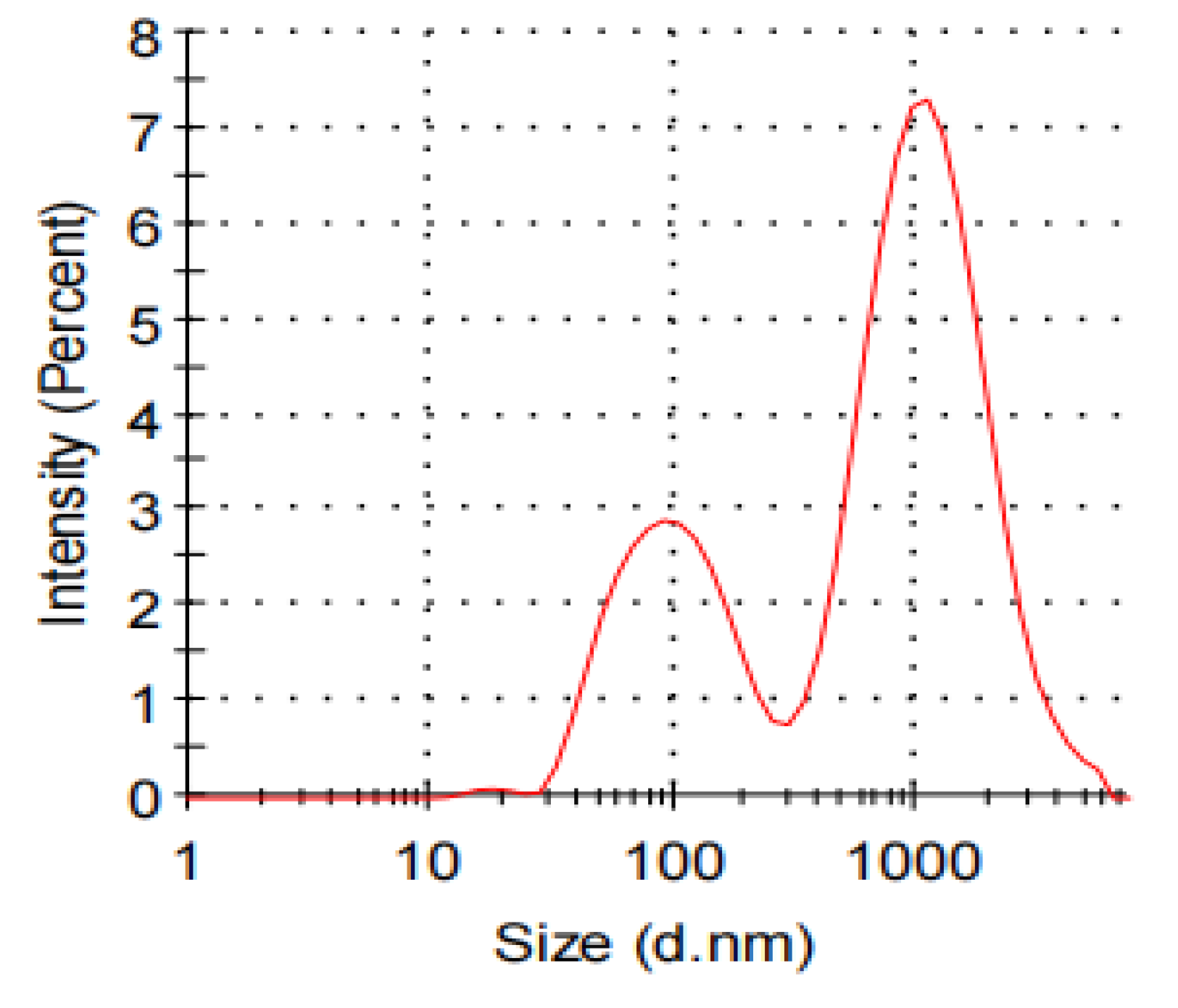

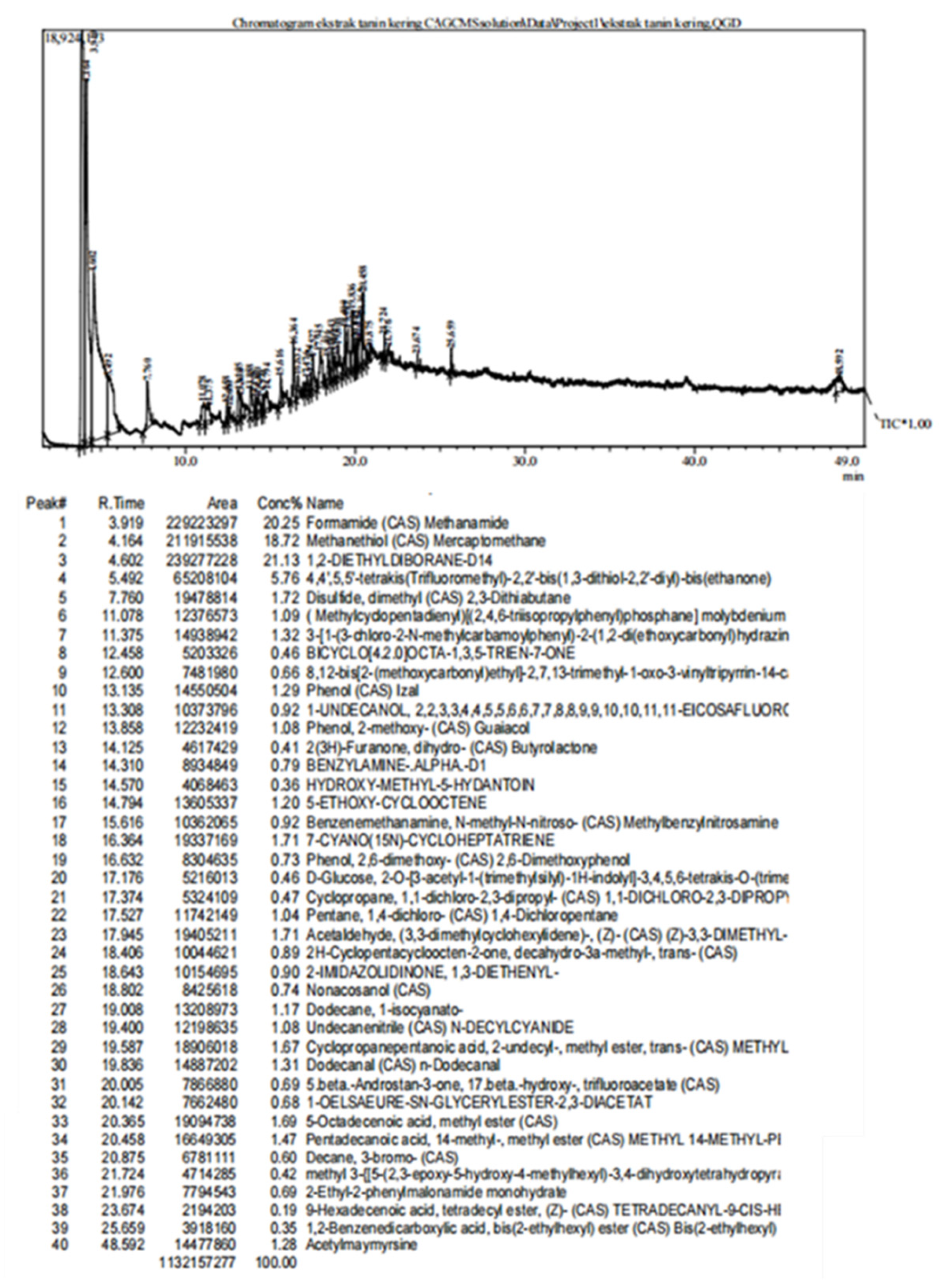

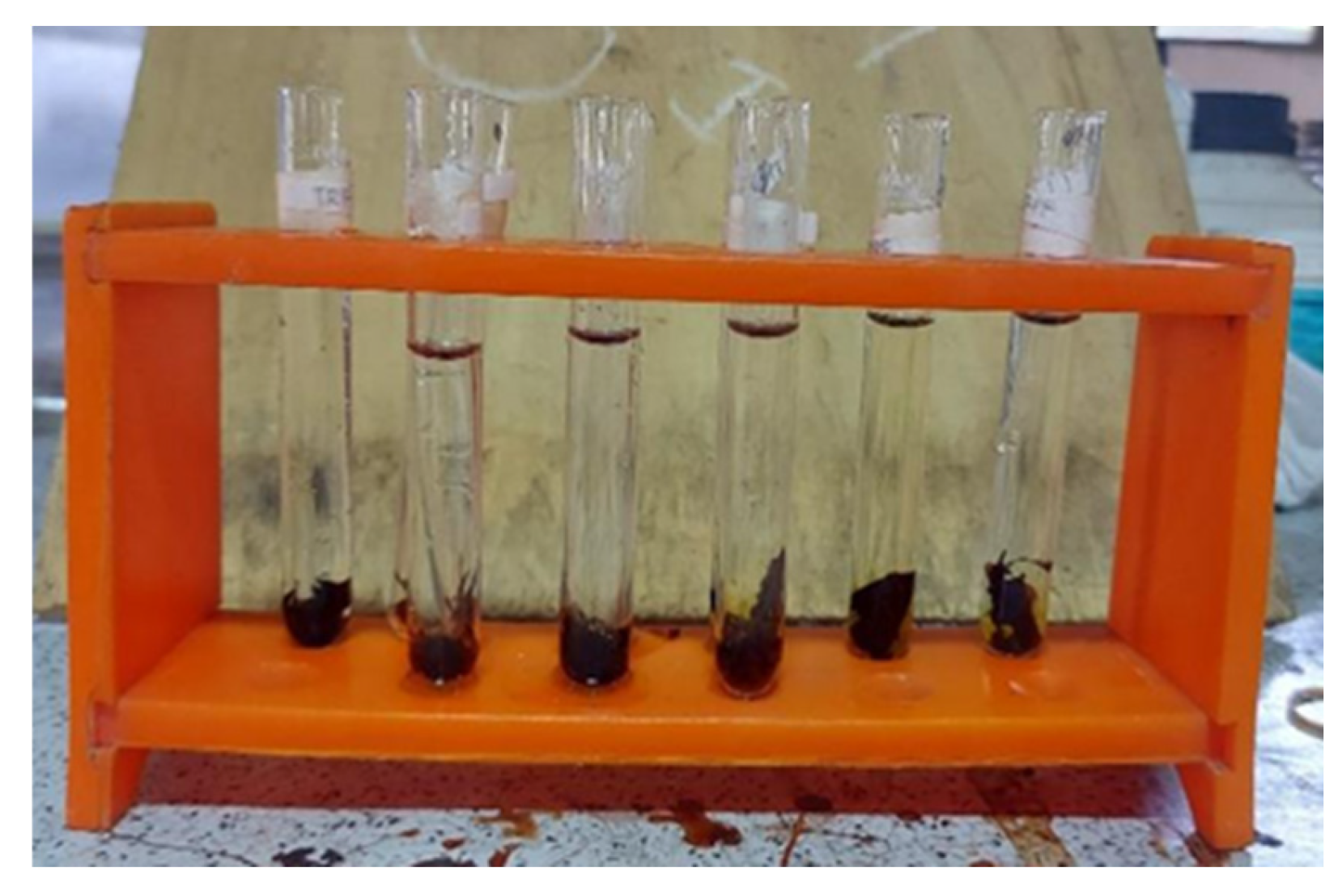

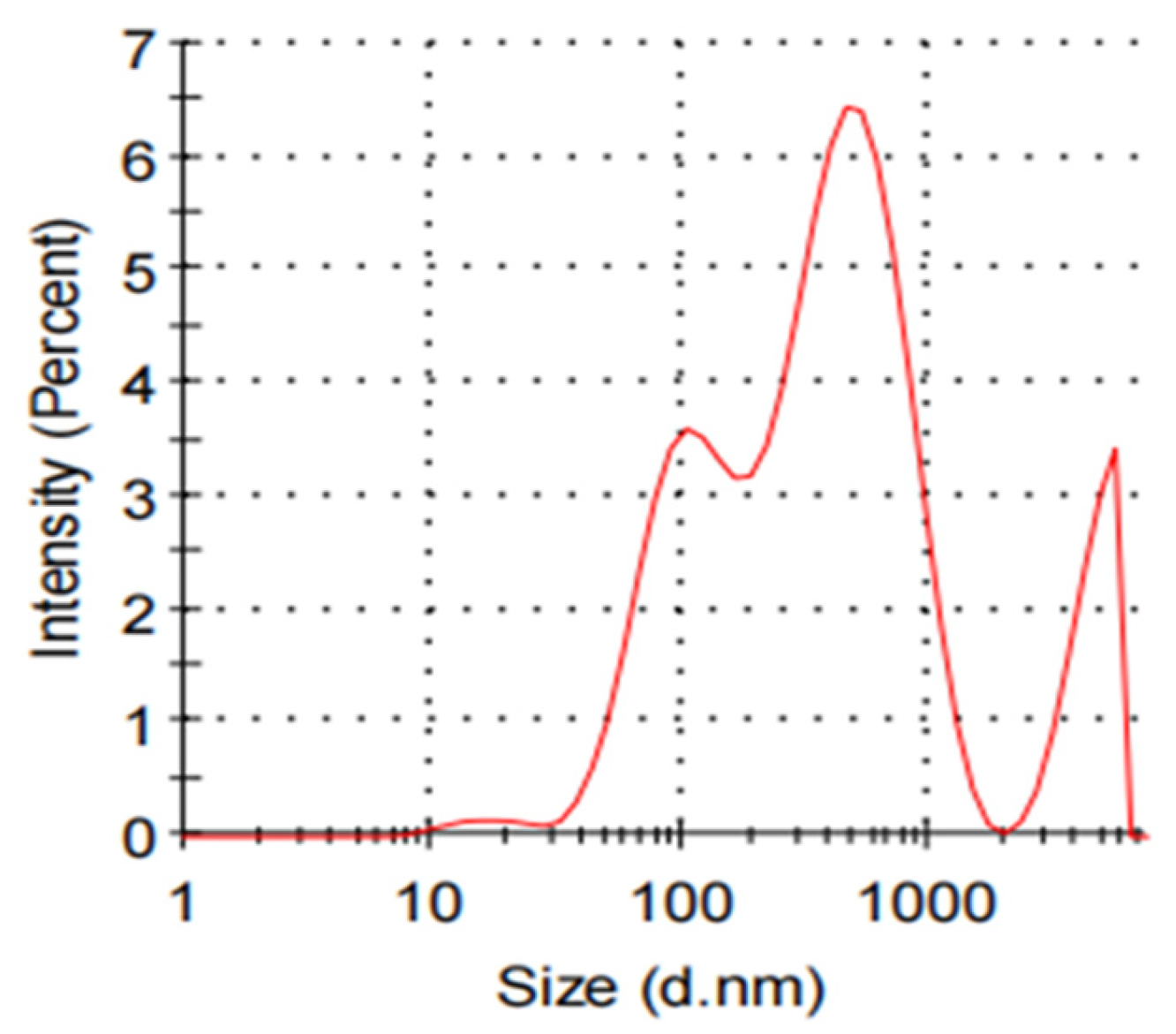

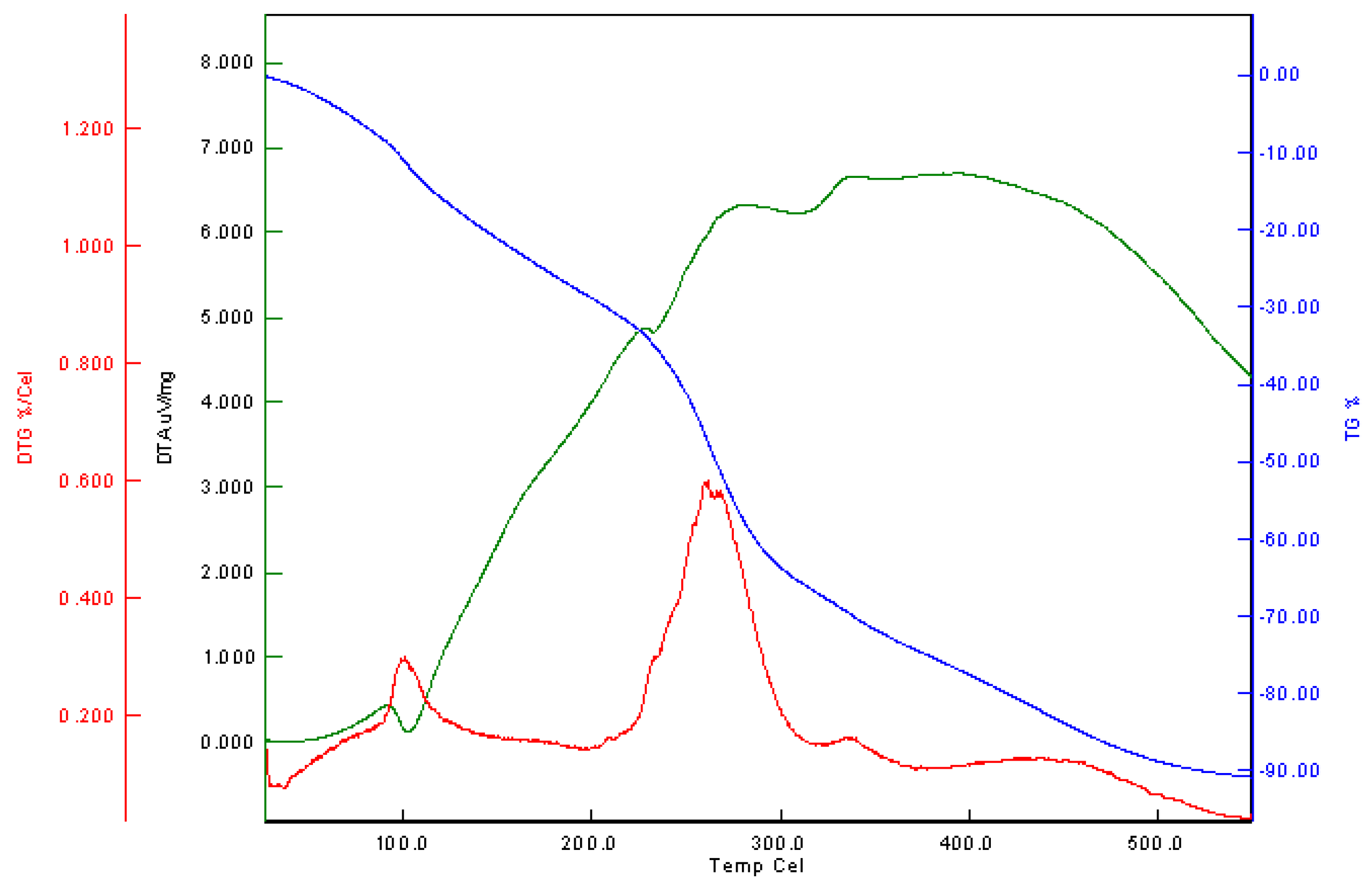

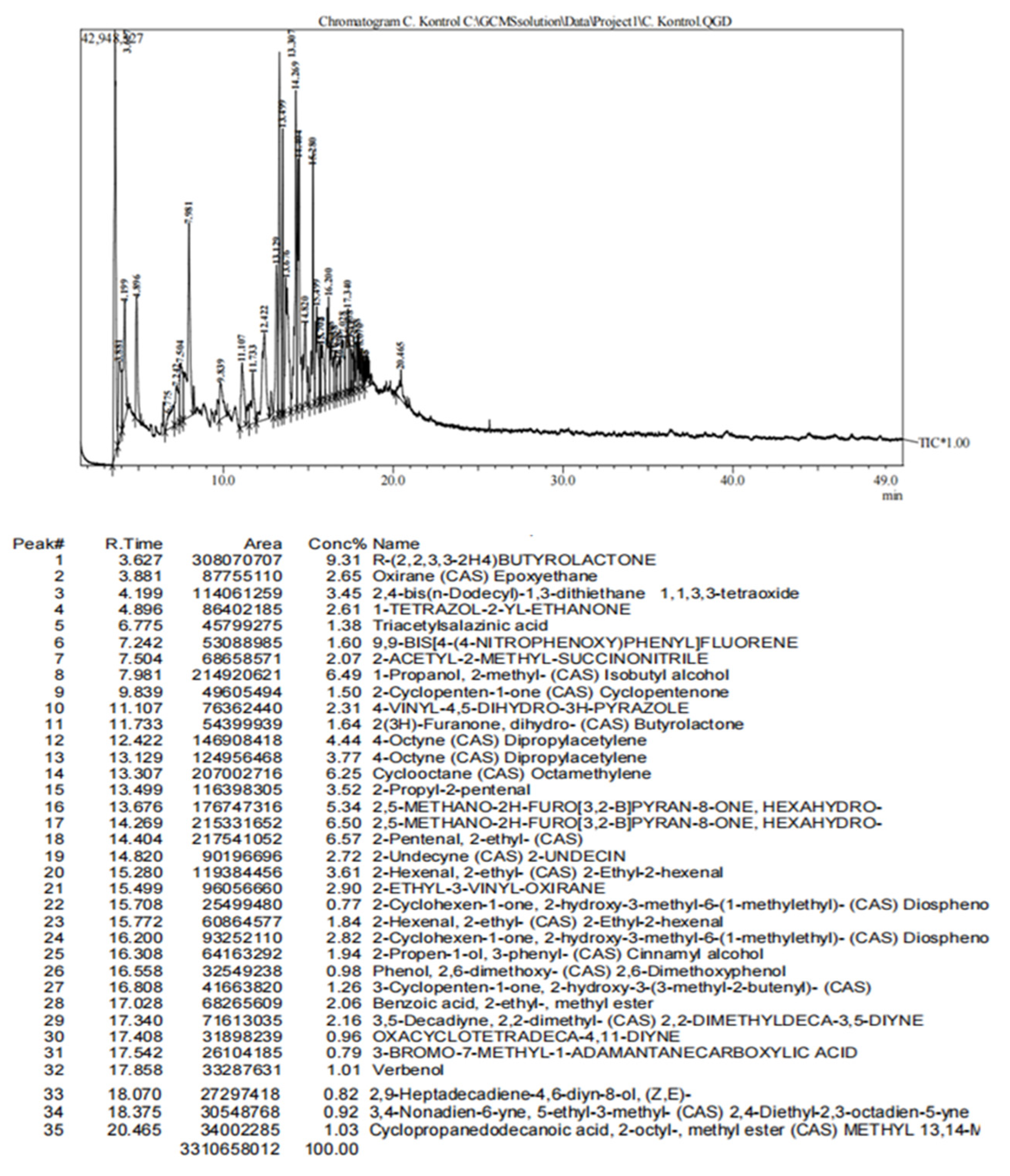

3.1. Characteristics of Sengon Bark Extract

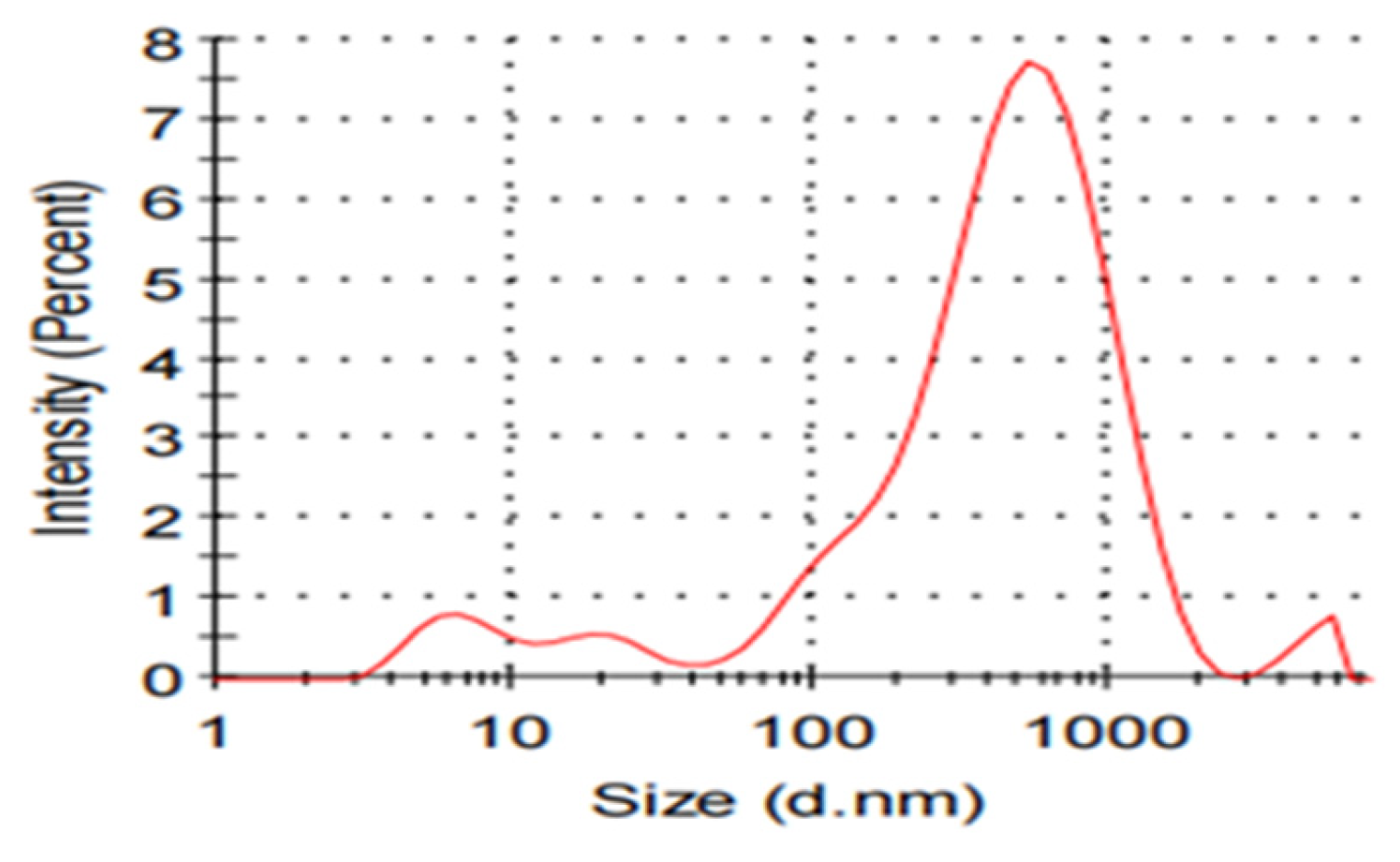

3.2. Characteristics of Bio-Resin Adhesive

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry (2023). Statistics Indonesian Forestry 2022, Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Jakarta, Indonesia.

- TechSci Research. (2023). Plywood and laminates market - Global industry size, share, trends opportunity, and forecast 2018-2028. TechSci Research.

- Ćehić, Minka & Omer, Salah-Eldien & Hodžić, Atif. (2008). Influence Construction And Properties Of Plywood On Areas Of Their Application In Wooden Constructions in Trends in the Development of Machinery and Associated Technology. The 12th International Research/Expert Conference - TMT 2008, Istanbul, Turkey, 26–30 August 2008.

- Sandberg, D. (2016). “Additives in wood products—Today and future development,” in: Environmental Impacts of Traditional and Innovative Forest-based Bioproducts. Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes, A. Kutnar and S.S. Muthu (eds.), Springer, Singapore, pp. 105-172. [CrossRef]

- Sandra, M., M, Jorge, Magalhães, F. Luisa and C. Luisa. (2018). Lightweight Wood Composites: Challenges, Production and Performance. 10.1007/978-3-319-68696-7_7.

- Ramage, M. H., Burridge, H., Busse-Wicher, M., Fereday, G., Reynolds, T., Shah, D. U., Wu, G., Yu, L., Fleming, P., Densley-Tingley, D., Allwood, J., Dupree, P., Linden, P. F., & Scherman, O. (2017). The wood from the trees: The use of timber in construction. *Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 68*(Part 1), 333–359. [CrossRef]

- Dunky, M. (1998). “Urea–formaldehyde (UF) adhesive resins for wood,” International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 18(2), 95–107. [CrossRef]

- Zorba, T., Papadopoulou, E., Hatjiissaak, A., Paraskevopoulos, K. M., and Chrissafis, K. (2008). “Urea-formaldehyde resins characterized by thermal analysis and FTIR method,” Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 92(1), 29-33. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Sakai, S., Wu, D., Chen, Z., Zhu, N., Huang, C., Sun, S., Zhang, M., Umemura, K., and Yong, Q. (2019). “Further exploration of sucrose-citric acid adhesive: Investigation of optimal hot-pressing conditions for plywood and curing behavior,” Polymers 11(12), article 1996. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Jeong, B., and Park, B.-D. (2021). “Comparison of adhesion behavior of urea-formaldehyde resins with melamine-urea-formaldehyde resins in bonding wood,” Forests 12(8), article 1037. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H., Qiu, T., Guo, L., Ye, J., and Li, X. (2015). “The microcapsule-type formaldehyde scavenger: The preparation and the application in urea-formaldehyde adhesives,” Journal of Hazardous Materials 293, 46-53. [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, U., and Colakoglu, G. (2021). “Effect of using urea formaldehyde modified with extracts in plywood on formaldehyde emission,” Drvna Industrija 72(3), 237-244. [CrossRef]

- Solt, P., Konnerth, J., Gindl-Altmutter, W., Kantner, W., Moser, J., Mitter, R., and van Herwijnen, H. W. G. (2019). “Technological performance of formaldehyde-free adhesive alternatives for particleboard industry,” International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 94, 99-131. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Carlborn, K., Matuana, L. M., and Heiden, P. A. (2006). “Thermoplastic modification of urea–formaldehyde wood adhesives to improve moisture resistance,” Journal of Applied Polymer Science 101(6), 4222-4229. [CrossRef]

- Hematabadi, H., Behrooz, R., Shakibi, A., and Arabi, M. (2012). “The reduction of indoor air formaldehyde from wood based composites using urea treatment for building materials,” Construction and Building Materials 28(1), 743-746. [CrossRef]

- Matsumae, T., Horito, M., Kurushima, N. and Yoshikazu Yazaki (2019). Development of bark-based adhesives for plywood: utilization of flavonoid compounds from bark and wood. II. J Wood Sci 65, 9 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Frihart, C. R., and Satori, H. (2013). “Soy flour dispersibility and performance as wood adhesive,” Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology 27(18–19), 2043-2052. [CrossRef]

- Veigel, S., Müller, U., Keckes, J., Obersriebnig, M., and Gindl-Altmutter, W. (2011). Cellulose nanofibrils as filler for adhesives: effect on specific fracture energy of solid wood-adhesive bonds. Cellulose, 18, 727–733. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y., Yuan, C., Deng, J., Zheng, W., Ji, Y., and Zhou, Q. (2022). “Injectable self-healing first-aid tissue adhesives with outstanding hemostatic and antibacterial performances for trauma emergency care,” ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 14(14), article 877. [CrossRef]

- Guder, M.; Günther, R.; Bremgartner, K.; Senn, N.; Brändli, C. (2024). Revealing the Impact of Viscoelastic Characteristics on Performance Parameters of UV-Crosslinked Hotmelt Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives: Insights from Time–Temperature Superposition Analysis. Polymers 2024, 16, 2123. [CrossRef]

- Santoso, A. & Abdurachman (2016). Characteristics of Mahogany Bark Extract as Wood Adhesive. Jurnal Penelitian Hasil Hutan Vol. 34 No. 4, Desember 2016: 269-284. DOI : http://doi.org/10.20886/jphh.2016.34.4.269-284.

- Osman, H., and Zakaria, M. H. (2012). “Effects of durian seed flour on processing torque, tensile, thermal and biodegradation properties of polypropylene and high density polyethylene composites,” Polymer-Plastics Technology and Engineering 51(3), 243-250. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L., Y. Zhang, L. G. Wang, X. Chen (2025). A comprehensive review of characterization techniques for particle adhesion and powder flowability. International Journal of Pharmaceutics Volume 669, 25 January 2025, 125029. [CrossRef]

- Dadpour, A., and S. K. Hosseinihashemi (2017). Comparative Analysis of the Chemical Composition of Juniperus excelsa ssp. polycarpos Bark and Wood Extracts. Journal of Advanced Laboratory Research in Biology 8(3): 57-61. https://e-journal.sospublication.co.in/.

- Keith, F. and & C. Oates (2011). Starch Markets in Asia. Southeast Asia and the Pacific at the International Potato Center (CIP), Bogor, Indonesia.

- Malik, J., A Santoso, B Ozarska (2020). Polymerised merbau extractives as impregnating material for wood properties enhancement. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 935 (2020) 012021. [CrossRef]

- Benthien, J. T., Sieburg-Rockel, J., Engehausen, N., Koch, G., & Lüdtke, J. (2022). Analysis of Adhesive Distribution over Particles According to Their Size and Potential Savings from Particle Surface Determination. Fibers, 10(11), 97. [CrossRef]

- Krisnawati, Haruni & E., Varis & Kallio, Maarit & Kanninen, Markku. (2011). Paraserianthes falcataria (L.) Nielsen: Ecology, silviculture and productivity. [CrossRef]

- Aryawan, C. W., and Fitriana, I. (2022). “Supplemental porang glucomannan flour (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) on green grass jelly (Cyclea barbata L. Miers) texture, syneresis, and moisture content,” Indonesian Journal of Food Technology 1(2), 180-193. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A., Paiva, N., Ferra, J., Martins, J., Carvalho, L., Barros-Timmons, A., and Magalhães, F. D. (2018). “Highly flexible glycol-urea-formaldehyde resins,” European Polymer Journal 105, 167-176. [CrossRef]

- Aydin, I., Colakoglu, G., Colak, S., and Demirkir, C. (2006). “Effects of moisture content on formaldehyde emission and mechanical properties of plywood,” Building and Environment 41(10), 1311-1316. [CrossRef]

- Bacigalupe, A., Molinari, F., Eisenberg, P., and Escobar, M. M. (2020). “Adhesive properties of urea-formaldehyde resins blended with soy protein concentrate,” Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials 3(2), 213-221. [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.-K., and Park, B.-D. (2017). “Effect of urea-formaldehyde resin adhesive viscosity on plywood adhesion,” Journal of the Korean Wood Science and Technology 45(2), 223-231. [CrossRef]

- He, J., Zhang, Z., Yang, Y., Ren, F., Li, J., Zhu, S., Ma, F., Wu, R., Lv, Y., He, G., et al. (2021). “Injectable self-healing adhesive pH-responsive hydrogels accelerate gastric hemostasis and wound healing,” Nano-Micro Letters 13(1), article 80. [CrossRef]

- Herzele, S., van Herwijnen, H. W. G., Edler, M., Gindl-Altmutter, W., & Konnerth, J. (2018). Cell-layer dependent adhesion differences in wood bonds. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 114, 21–29 []. You can consult the APA Style website for more details on formatting references.

- Frihart, C. R. (2005). Wood adhesion and adhesives. In J. W. Rowell (Ed.), Handbook of wood chemistry and wood composites (pp. 215–278). CRC Press.

- Frihart, C. R. (2009). Adhesive bonding and performance testing of bonded wood products. In C. R. Frihart & C. G. Hunt (Eds.), Adhesives with wood materials: Bond formation and performance (pp. 1–24). ASTM International.

- Frihart, C. R., & Hunt, C. G. (2010). Wood structure and adhesive bond strength. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Wood Adhesives (pp. 1–10). Forest Products Society.

- Pizzi, A., & Mittal, K. L. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of adhesive technology (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

- Li, J., & Li, X. (2014). Nanofillers in wood adhesives: Effects on mechanical properties and bonding performance. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, 28(8–9), 843–857.

- Zheng, G., Pan, A., Xu, Y., and Zhang, X. (2024). “Preparation of a superior soy protein adhesive with high solid content by enzymatic hydrolysis combined with cross-linking modification,” Industrial Crops and Products 213, article 118446. [CrossRef]

- Ebnesajjad, S. (2011). Handbook of adhesives and sealants (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

- ASTM International. (2018). ASTM D1084-16: Standard test methods for viscosity of adhesives.

- Hartati, N. S., Sudarmonowati, E., Fatriasari, W., Hermiati, E., & Dwianto, W. (2020). Wood characteristic of superior Sengon collection and prospect of wood properties improvement through genetic engineering. Research Centre for Biotechnology, LIPI. Hartati, N. S., Sudarmonowati, E., Fatriasari, W., Hermiati, E., & Dwianto, W. (2020). Wood characteristic of superior Sengon collection and prospect of wood properties improvement through genetic engineering. Research Centre for Biotechnology, LIPI.

- Fatriasari, W., & Risanto, L. (2015). The properties of kraft pulp from Sengon wood (Paraserianthes falcataria): Differences of cooking liquor concentration and bleaching sequence. Jurnal Selulosa, 50(2), 45–56.

- Loike, K.. (2022). Sengon: A fast growing wood at a glance. Retrieved from https://lightwood.org/sengon-a-fast-growing-wood-at-a-glance/. Published 22. February 2022.

- Fengel, D., & Wegener, G. (1989). Wood: Chemistry, ultrastructure, reactions. Walter de Gruyter.

- Yang, H., Yan, R., Chen, H., Lee, D. H., & Zheng, C. (2007). Characteristics of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin pyrolysis. Fuel, 86(12–13), 1781–1788.

- Fatriasari, W., Hermiati, E., & Syafii, W. (2014). Characterization of lignin from sengon (Paraserianthes falcataria) bark and its potential application in adhesives. Jurnal Selulosa, 49(2), 65–74.

- Mohan, D., Pittman, C. U., & Steele, P. H. (2006). Pyrolysis of wood/biomass for bio-oil: A critical review. Energy & Fuels, 20(3), 848–889.

- Heinze, T., & Liebert, T. (2001). Unconventional methods in cellulose functionalization. Progress in Polymer Science, 26(9), 1689–1762.

- Sun, X. S. (2005). Biobased polymers and composites. Elsevier Academic Press.

- Mohan, D., Pittman, C. U., & Steele, P. H. (2006). Pyrolysis of wood/biomass for bio-oil: A critical review. Energy & Fuels, 20(3), 848–889.

- Ding, R., Su, C., Yang, Y., Li, C., and Liu, J. (2013). “Effect of wheat flour on the viscosity of urea-formaldehyde adhesive,” International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 41, 1-5. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).