Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

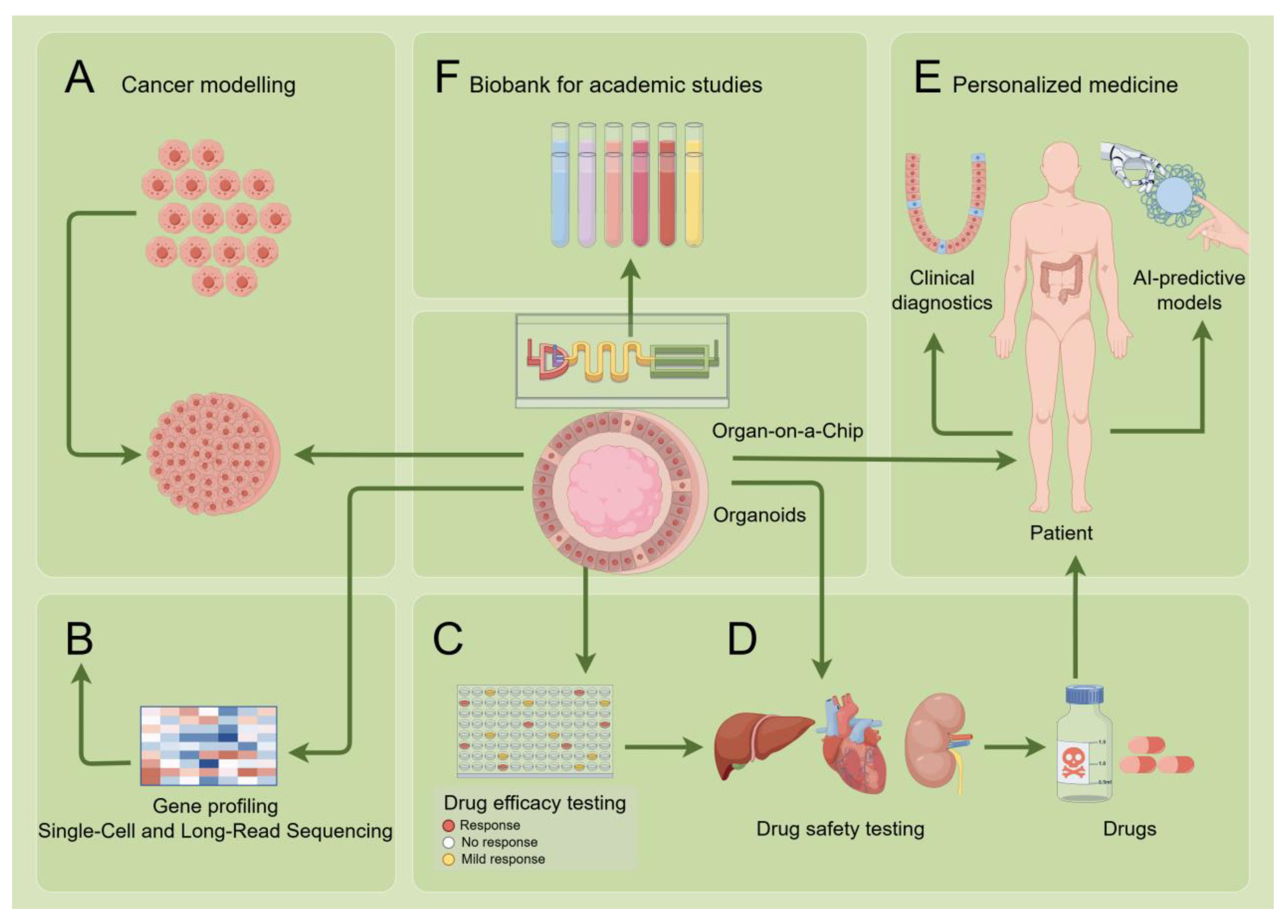

2. Organoids and Organ-on-a-Chip Systems

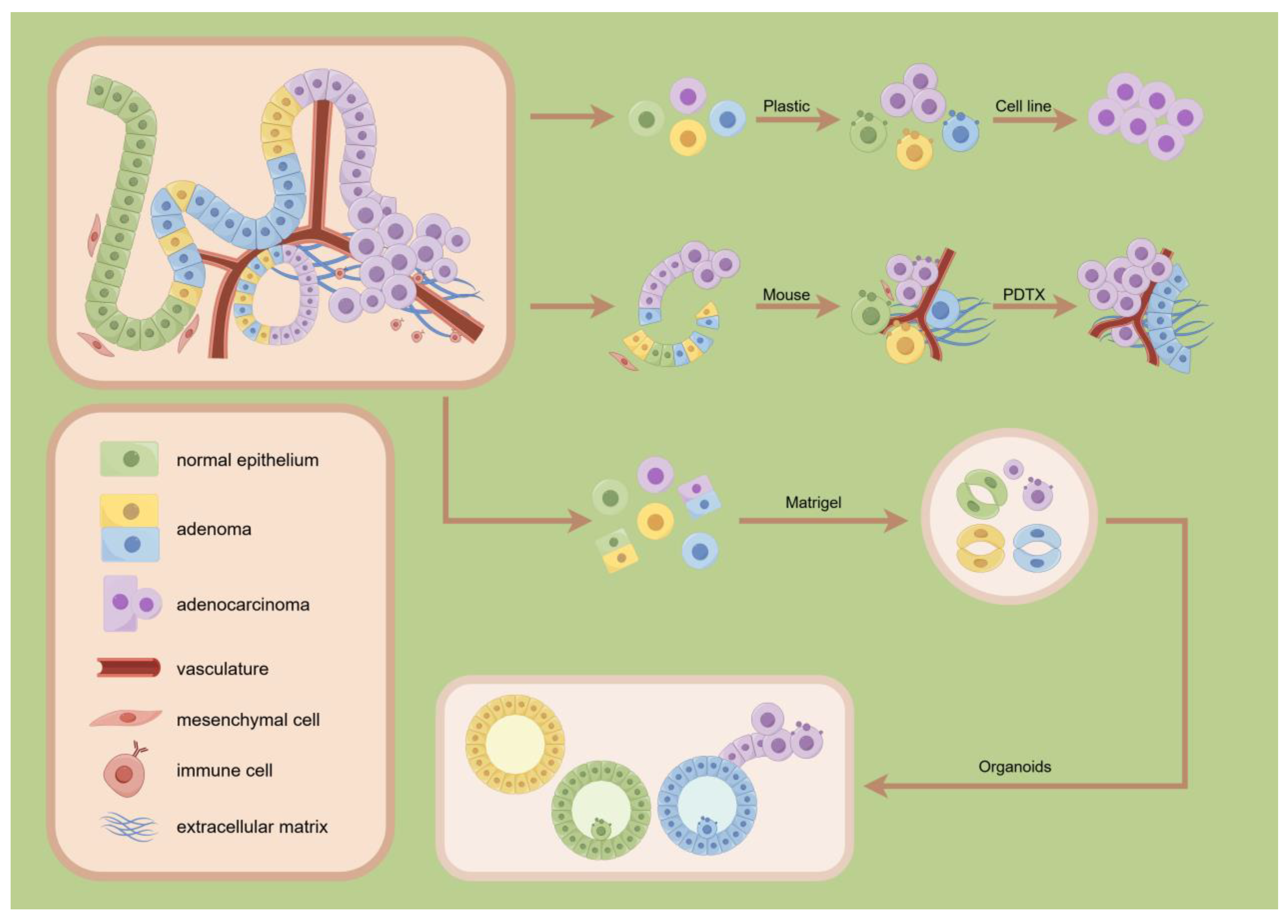

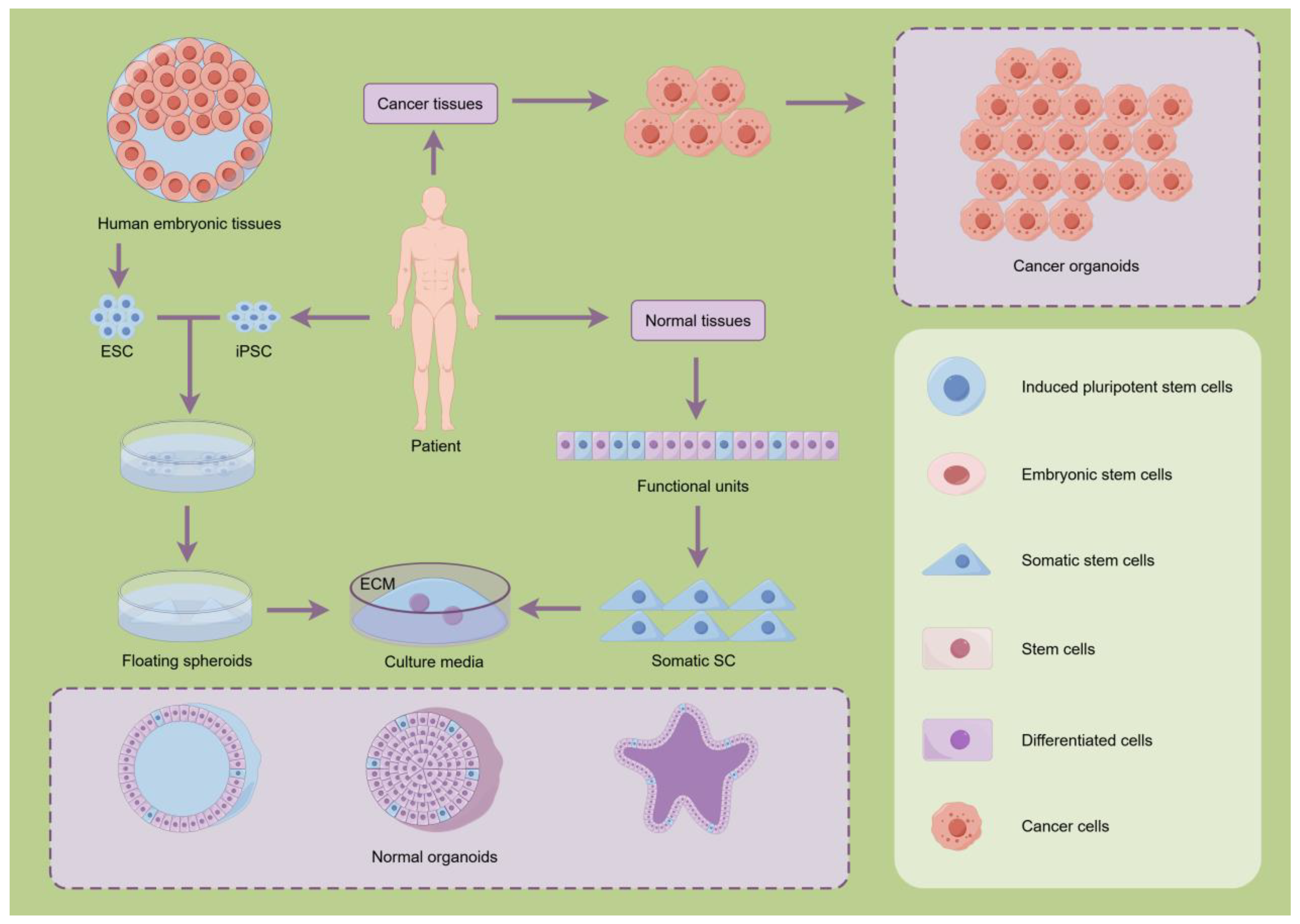

2.1. Organoids Systems

2.2. Organ-on-a-Chip Systems

2.3. Organoid Revolution

3. Advancing Organoid Technology: Culture and Quality Control

3.1. Breakthroughs in the Core Culture Technology of Organoids

3.2. Quality Assessment and Standardization of Organoids

4. Clinical Translation of Organoids

4.1. Application of Organoids in Clinical Diagnostics

4.2. Applications of Organoids in Disease Modeling

4.3. Application of Organoids in Therapeutic Development and Personalized Medicine

4.4. Barriers in Translation

5. Future Directions: Integration of AI and Sequencing Technologies

5.1. AI-Powered Organoid Analysis

5.2. Application of Organoid Technology in Single-Cell and Long-Read Sequencing

6. Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| PDTO | Patient-Derived Tumor Organoid |

| iPSCs | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| ASCs | Adult Stem Cells |

| PDOs | Patient-Derived Organoids |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| HUVECs | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells |

| NVUs | Neurovascular Units |

| dECM | Decellularized Extracellular Matrix |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate |

| FAD | Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide |

| CF | Cystic Fibrosis |

| CFTR | Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator |

| TILs | Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes |

| NAFLD | Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| NASH | Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis |

| GSIS | Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| CRS | Cytokine Release Syndrome |

| CAR-T | Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Practice |

| PK-PD | Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| FAIR | Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| siRNA | Small Interfering RNA |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

References

- Han, X.; Cai, C.; Deng, W.; et al. Landscape of human organoids: Ideal model in clinics and research. Innovation (Camb) 2024, 5, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, I.; Gupta, K.; Mishra, R.; et al. An Exploration of Organoid Technology: Present Advancements, Applications, and Obstacles. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2024, 25, 1000–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Hou, K.; Zhou, H.; et al. Liver organoids and their application in liver cancer research. Regen Ther 2024, 25, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, B.; Li, X.; Hao, M.; et al. Organoid-Guided Precision Medicine: From Bench to Bedside. MedComm 2025, 6, e70195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, B.; Zinocker, S.; Holm, S.; et al. Organoids in the Clinic: A Systematic Review of Outcomes. Cells Tissues Organs 2023, 212, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, L.; Kirk, R. High drug attrition rates--where are we going wrong? . Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011, 8, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhans, S.A. Three-Dimensional in Vitro Cell Culture Models in Drug Discovery and Drug Repositioning. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, I.W.; Evaniew, N.; Ghert, M. Lost in translation: animal models and clinical trials in cancer treatment. Am J Transl Res 2014, 6, 114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P.M.; Weaver, V.M. Cellular adaptation to biomechanical stress across length scales in tissue homeostasis and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2017, 67, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maman, S.; Witz, I.P. A history of exploring cancer in context. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H. Modeling Development and Disease with Organoids. Cell 2016, 165, 1586–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Vries, R.G.; Snippert, H.J.; et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 2009, 459, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drost, J.; Clevers, H. Organoids in cancer research. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachogiannis, G.; Hedayat, S.; Vatsiou, A.; et al. Patient-derived organoids model treatment response of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. Science 2018, 359, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Koo, B.; Knoblich, J.A. Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduin, M.; Hoeben, A.; De Ruysscher, D.; et al. Patient-Derived Cancer Organoids as Predictors of Treatment Response. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 641980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, B.; et al. Patient-derived models facilitate precision medicine in liver cancer by remodeling cell-matrix interaction. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistini, C.; Cavallaro, U. Patient-Derived In Vitro Models of Ovarian Cancer: Powerful Tools to Explore the Biology of the Disease and Develop Personalized Treatments. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Advances in Thyroid Organoids Research and Applications. Endocr Res 2024, 49, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Seong, Y.; Lee, E.; et al. Applications and research trends in organoid based infectious disease models. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 25185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Oyang, L.; Peng, Q.; et al. Organoids: opportunities and challenges of cancer therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1232528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, M.J.; et al. Validating Well-Functioning Hepatic Organoids for Toxicity Evaluation. Toxics 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qu, P.; Liu, J.; et al. Application of human cardiac organoids in cardiovascular disease research. Front Cell Dev Biol 2025, 13, 1564889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittman-Soto, X.S.; Thomas, E.S.; Ganshert, M.E.; et al. The Transformative Role of 3D Culture Models in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Research. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne, O.; Sabatie, S.; Laurent, B. Deciphering the physiopathology of neurodevelopmental disorders using brain organoids. Brain 2025, 148, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.; Vilar, E.; Tsai, S.; et al. Colonic organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for modeling colorectal cancer and drug testing. Nat Med 2017, 23, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, N.; de Ligt, J.; Kopper, O.; et al. A Living Biobank of Breast Cancer Organoids Captures Disease Heterogeneity. Cell 2018, 172, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooft, S.N.; Weeber, F.; Dijkstra, K.K.; et al. Patient-derived organoids can predict response to chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Sci Transl Med 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driehuis, E.; van Hoeck, A.; Moore, K.; et al. Pancreatic cancer organoids recapitulate disease and allow personalized drug screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 26580–26590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, L.; et al. Patient-Derived Organoids Predict Chemoradiation Responses of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensink, G.E.; Elias, S.G.; Mullenders, J.; et al. Patient-derived organoids as a predictive biomarker for treatment response in cancer patients. NPJ Precis Oncol 2021, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontheimer-Phelps, A.; Hassell, B.A.; Ingber, D.E. Modelling cancer in microfluidic human organs-on-chips. Nat Rev Cancer 2019, 19, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingber, D.E. Human organs-on-chips for disease modelling, drug development and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Genet 2022, 23, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Montiel, F.T.; George, S.M.; Gough, A.H.; et al. Control of oxygen tension recapitulates zone-specific functions in human liver microphysiology systems. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2017, 242, 1617–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Fritz, J.V.; Glaab, E.; et al. A microfluidics-based in vitro model of the gastrointestinal human-microbe interface. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Coppeta, J.R.; Rogers, H.B.; et al. A microfluidic culture model of the human reproductive tract and 28-day menstrual cycle. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimek, K.; Hsu, H.; Boehme, M.; et al. Bioengineering of a Full-Thickness Skin Equivalent in a 96-Well Insert Format for Substance Permeation Studies and Organ-On-A-Chip Applications. Bioengineering (Basel) 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Bai, H.; Rodas, M.; et al. A human-airway-on-a-chip for the rapid identification of candidate antiviral therapeutics and prophylactics. Nat Biomed Eng 2021, 5, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Loskill, P.; Shao, K.; et al. Human iPSC-based cardiac microphysiological system for drug screening applications. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peletier, M.; Zhang, X.; Klein, S.; et al. Multicellular 3D models to study myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1494911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.A.P.; Aleman, J.; Wan, M.; et al. Probing prodrug metabolism and reciprocal toxicity with an integrated and humanized multi-tissue organ-on-a-chip platform. Acta Biomater 2020, 106, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, F.A.; Gibot, L.; Lacroix, D. The pivotal role of vascularization in tissue engineering. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2013, 15, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Mouradov, D.; Lee, M.; et al. Unified framework for patient-derived, tumor-organoid-based predictive testing of standard-of-care therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, X.; et al. From cell spheroids to vascularized cancer organoids: Microfluidic tumor-on-a-chip models for preclinical drug evaluations. Biomicrofluidics 2021, 15, 61503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, A.; Phan, D.T.T.; Datta, R.; et al. 3D microtumors in vitro supported by perfused vascular networks. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 31589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R.W.; Aref, A.R.; Lizotte, P.H.; et al. Ex Vivo Profiling of PD-1 Blockade Using Organotypic Tumor Spheroids. Cancer Discov 2018, 8, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenberg, N.; Hoehnel, S.; Kuttler, F.; et al. High-throughput automated organoid culture via stem-cell aggregation in microcavity arrays. Nat Biomed Eng 2020, 4, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, R.; Ingram, M.; Marquez, S.; et al. Robotic fluidic coupling and interrogation of multiple vascularized organ chips. Nat Biomed Eng 2020, 4, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Aleman, J.; Shin, S.R.; et al. Multisensor-integrated organs-on-chips platform for automated and continual in situ monitoring of organoid behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E2293–E2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjakkal, L.; Dervin, S.; Dahiya, R. Flexible potentiometric pH sensors for wearable systems. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 8594–8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.; Ortega-Ribera, M.; Guimera, X.; et al. Online oxygen monitoring using integrated inkjet-printed sensors in a liver-on-a-chip system. Lab Chip 2018, 18, 2023–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lang, Q.; Liang, B.; et al. Electrochemical Glucose Biosensor Based on Glucose Oxidase Displayed on Yeast Surface. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1319, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perni, M.; Galvagnion, C.; Maltsev, A.; et al. A natural product inhibits the initiation of alpha-synuclein aggregation and suppresses its toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E1009–E1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szucs, D.; Fekete, Z.; Guba, M.; et al. Toward better drug development: Three-dimensional bioprinting in toxicological research. Int J Bioprint 2023, 9, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.A.; Mummery, C.; Berridge, B.R.; et al. Organs-on-chips: into the next decade. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Gao, W.; Hu, H.; et al. Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? . Acta Pharm Sin B 2022, 12, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broutier, L.; Mastrogiovanni, G.; Verstegen, M.M.; et al. Human primary liver cancer-derived organoid cultures for disease modeling and drug screening. Nat Med 2017, 23, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, N.L.; Ashuach, T.; Lyons, D.E.; et al. Hepatitis C virus infects and perturbs liver stem cells. mBio 2023, 14, e131823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, Z.; et al. Construction of vascularized liver microtissues recapitulates angiocrine-mediated hepatocytes maturation and enhances therapeutic efficacy for acute liver failure. Bioact Mater 2025, 50, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, V.; Parseh, B. Organoid models of breast cancer in precision medicine and translational research. Mol Biol Rep 2024, 52, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, T.A.; Muotri, A.R. Advancing preclinical models of psychiatric disorders with human brain organoid cultures. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, S.; Gu, L.; et al. High-throughput bioengineering of homogenous and functional human-induced pluripotent stem cells-derived liver organoids via micropatterning technique. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 937595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Y.; Ueyama-Toba, Y.; Yokota, J.; et al. Efficient hepatocyte differentiation of primary human hepatocyte-derived organoids using three dimensional nanofibers (HYDROX) and their possible application in hepatotoxicity research. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 10846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gout, J.; Ekizce, M.; Roger, E.; et al. Pancreatic organoids as cancer avatars for true personalized medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2025, 224, 115642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, S.; Ma, D.; et al. Targeting SphK2 Reverses Acquired Resistance of Regorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Mourtzinos, A.; Heegsma, J.; et al. Growth differentiation factor 7 autocrine signaling promotes hepatic progenitor cell expansion in liver fibrosis. Stem Cell Res Ther 2023, 14, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khobar, K.E.; Sukowati, C.H.C. Updates on Organoid Model for the Study of Liver Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2023, 22, 2071071318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.S.; Postovit, L.M.; Lajoie, G.A. Matrigel: a complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics 2010, 10, 1886–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjorevski, N.; Sachs, N.; Manfrin, A.; et al. Designer matrices for intestinal stem cell and organoid culture. Nature 2016, 539, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giobbe, G.G.; Michielin, F.; Luni, C.; et al. Functional differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells on a chip. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Sung, J.H. Organ-on-a-Chip Technology for Reproducing Multiorgan Physiology. Adv Healthc Mater 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, K.A.; Gupta, N.; Kroll, K.T.; et al. Flow-enhanced vascularization and maturation of kidney organoids in vitro. Nat Methods 2019, 16, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Shao, Q.; et al. Pentapeptide IKVAV-engineered hydrogels for neural stem cell attachment. Biomater Sci 2021, 9, 2887–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, F.; Zou, Y.; Bie, B.; et al. Dual siRNA-Loaded Cell Membrane Functionalized Matrix Facilitates Bone Regeneration with Angiogenesis and Neurogenesis. Small 2024, 20, e2307062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; et al. Trends and challenges in organoid modeling and expansion with pluripotent stem cells and somatic tissue. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.C.; Than, N.; Park, S.J.; et al. Bioengineered human gut-on-a-chip for advancing non-clinical pharmaco-toxicology. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2024, 20, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, M.; Lutolf, M.P. Engineering organoids. Nat Rev Mater 2021, 6, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehnke, K.; Iversen, P.W.; Schumacher, D.; et al. Assay Establishment and Validation of a High-Throughput Screening Platform for Three-Dimensional Patient-Derived Colon Cancer Organoid Cultures. J Biomol Screen 2016, 21, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, C.; Boutros, M.; Camp, J.G.; et al. The Organoid Cell Atlas. Nat Biotechnol 2021, 39, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, J.F.; Alieva, M.; Wellens, L.M.; et al. High-resolution 3D imaging of fixed and cleared organoids. Nat Protoc 2019, 14, 1756–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikura, M.; Muraoka, Y.; Hirami, Y.; et al. Adaptive Optics Optical Coherence Tomography Analysis of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Retinal Organoid Transplantation in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Cureus 2024, 16, e64962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, D.A.; Deming, D.; Skala, M.C. Patient-derived cancer organoid tracking with wide-field one-photon redox imaging to assess treatment response. J Biomed Opt 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sahoo, S.; Pattanaik, S.; et al. Advancing breast cancer research: a comprehensive review of in vitro and in vivo experimental models. Med Oncol 2025, 42, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto, E.P.; Dobrolecki, L.E.; Villanueva, H.; et al. In Vivo Modeling of Human Breast Cancer Using Cell Line and Patient-Derived Xenografts. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2022, 27, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevers, H. COVID-19: organoids go viral. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Huch, M. Disease modelling in human organoids. Dis Model Mech 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasato, M.; Er, P.X.; Chiu, H.S.; et al. Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis. Nature 2015, 526, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Nguyen, H.N.; Song, M.M.; et al. Brain-Region-Specific Organoids Using Mini-bioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure. Cell 2016, 165, 1238–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretto, M.; Maenhoudt, N.; Luo, X.; et al. Patient-derived organoids from endometrial disease capture clinical heterogeneity and are amenable to drug screening. Nat Cell Biol 2019, 21, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili-Firoozinezhad, S.; Gazzaniga, F.S.; Calamari, E.L.; et al. A complex human gut microbiome cultured in an anaerobic intestine-on-a-chip. Nat Biomed Eng 2019, 3, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, E.; Meraviglia, V.; Campostrini, G.; et al. Human-iPSC-Derived Cardiac Stromal Cells Enhance Maturation in 3D Cardiac Microtissues and Reveal Non-cardiomyocyte Contributions to Heart Disease. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 862–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, C.A.; Gao, R.; Negraes, P.D.; et al. Complex Oscillatory Waves Emerging from Cortical Organoids Model Early Human Brain Network Development. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Mead, B.E.; Safaee, H.; et al. Engineering Stem Cell Organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, U.; Siranosian, B.; Ha, G.; et al. Genetic and transcriptional evolution alters cancer cell line drug response. Nature 2018, 560, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiriac, H.; Belleau, P.; Engle, D.D.; et al. Organoid Profiling Identifies Common Responders to Chemotherapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov 2018, 8, 1112–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Non-genetic heterogeneity of cells in development: more than just noise. Development 2009, 136, 3853–3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Clevers, H. Growing self-organizing mini-guts from a single intestinal stem cell: mechanism and applications. Science 2013, 340, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.J.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, H.; Madrange, L.; Baquerre, C.; et al. Towards a quality control framework for cerebral cortical organoids. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 29431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehullah, A.; Tan, S.H.; Barker, N. Organoids as an in vitro model of human development and disease. Nat Cell Biol 2016, 18, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkauskas, C.E.; Chung, M.; Fioret, B.; et al. Lung organoids: current uses and future promise. Development 2017, 144, 986–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; He, A.; Zhou, R.; et al. Building consensus on the application of organoid-based drug sensitivity testing in cancer precision medicine and drug development. Theranostics 2024, 14, 3300–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madorsky Rowdo, F.P.; Xiao, G.; Khramtsova, G.F.; et al. Patient-derived tumor organoids with p53 mutations, and not wild-type p53, are sensitive to synergistic combination PARP inhibitor treatment. Cancer Lett 2024, 584, 216608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Cao, J.; Wang, G.; et al. Circulating bile acid profiles characteristics and the potential predictive role in clear cell renal cell carcinoma progression. BMC Nephrol 2025, 26, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Clinical value and influencing factors of establishing stomach cancer organoids by endoscopic biopsy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023, 149, 3803–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorel, L.; Elie, N.; Morice, P.; et al. Automated Scoring to Assess RAD51-Mediated Homologous Recombination in Ovarian Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids. Lab Invest 2025, 105, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, W.K.; Mungenast, A.E.; Lin, Y.; et al. Self-Organizing 3D Human Neural Tissue Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Recapitulate Alzheimer’s Disease Phenotypes. PLoS One 2016, 11, e161969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, R.; Sheng, S.; et al. Combination therapy using intestinal organoids and their extracellular vesicles for inflammatory bowel disease complicated with osteoporosis. J Orthop Translat 2025, 53, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairon, K.G.; Nigam, A.; Khanal, T.; et al. RCAN1.4 regulates tumor cell engraftment and invasion in a thyroid cancer to lung metastasis-on-a-chip microphysiological system. Biofabrication 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astashkina, A.I.; Mann, B.K.; Prestwich, G.D.; et al. Comparing predictive drug nephrotoxicity biomarkers in kidney 3-D primary organoid culture and immortalized cell lines. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 4712–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaziotis, F.; Muraro, D.; Tysoe, O.C.; et al. Cholangiocyte organoids can repair bile ducts after transplantation in the human liver. Science 2021, 371, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashimoto, Y.; Okada, R.; Hanada, S.; et al. Vascularized cancer on a chip: The effect of perfusion on growth and drug delivery of tumor spheroid. Biomaterials 2020, 229, 119547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, C.; Samudyata, S.; Thams, S.; et al. Organoids and chimeras: the hopeful fusion transforming traumatic brain injury research. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2024, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wetering, M.; Francies, H.E.; Francis, J.M.; et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell 2015, 161, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yu, Y. Patient-derived organoids in translational oncology and drug screening. Cancer Lett 2023, 562, 216180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurts, M.H.; de Poel, E.; Amatngalim, G.D.; et al. CRISPR-Based Adenine Editors Correct Nonsense Mutations in a Cystic Fibrosis Organoid Biobank. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.; Mao, Y.; Han, X.; et al. EGR1 Regulates SHANK3 Transcription at Different Stages of Brain Development. Neuroscience 2024, 540, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, Y.; Kolahi, K.S.; Du, Y.; et al. A CRISPR/Cas9-Engineered ARID1A-Deficient Human Gastric Cancer Organoid Model Reveals Essential and Nonessential Modes of Oncogenic Transformation. Cancer Discov 2021, 11, 1562–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, C.J.; Poling, H.M.; Chen, K.; et al. Coordinated differentiation of human intestinal organoids with functional enteric neurons and vasculature. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youk, J.; Kim, T.; Evans, K.V.; et al. Three-Dimensional Human Alveolar Stem Cell Culture Models Reveal Infection Response to SARS-CoV-2. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahudeen, A.A.; Choi, S.S.; Rustagi, A.; et al. Progenitor identification and SARS-CoV-2 infection in human distal lung organoids. Nature 2020, 588, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettayebi, K.; Kaur, G.; Patil, K.; et al. Insights into human norovirus cultivation in human intestinal enteroids. mSphere 2024, 9, e44824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Buth, J.E.; Vishlaghi, N.; et al. Self-Organized Cerebral Organoids with Human-Specific Features Predict Effective Drugs to Combat Zika Virus Infection. Cell Rep 2017, 21, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, R.; Togo, S.; Kimura, M.; et al. Modeling Steatohepatitis in Humans with Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Organoids. Cell Metab 2019, 30, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboa, D.; Saarimaki-Vire, J.; Borshagovski, D.; et al. Insulin mutations impair beta-cell development in a patient-derived iPSC model of neonatal diabetes. Elife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahjalal, H.M.; Abdal Dayem, A.; Lim, K.M.; et al. Generation of pancreatic beta cells for treatment of diabetes: advances and challenges. Stem Cell Res Ther 2018, 9, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Mun, H.; Sung, C.O.; et al. Patient-derived lung cancer organoids as in vitro cancer models for therapeutic screening. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adashi, E.Y.; O’Mahony, D.P.; Cohen, I.G. The FDA Modernization Act 2.0: Drug Testing in Animals is Rendered Optional. Am J Med 2023, 136, 853–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S.; Petersilie, L.; Inak, G.; et al. Generation of Human Brain Organoids for Mitochondrial Disease Modeling. J Vis Exp 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto, N.; Sasaki, N.; Aoki, R.; et al. Gut pathobionts underlie intestinal barrier dysfunction and liver T helper 17 cell immune response in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat Microbiol 2019, 4, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.J.; Soibam, B.; O’Leary, J.G.; et al. Recellularization of rat liver: An in vitro model for assessing human drug metabolism and liver biology. PLoS One 2018, 13, e191892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Deng, N.; Dou, L.; et al. 3-D Human Renal Tubular Organoids Generated from Urine-Derived Stem Cells for Nephrotoxicity Screening. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2020, 6, 6701–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, K.K.; Cattaneo, C.M.; Weeber, F.; et al. Generation of Tumor-Reactive T Cells by Co-culture of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes and Tumor Organoids. Cell 2018, 174, 1586–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, K.; Wu, C.; O’Rourke, K.P.; et al. A rectal cancer organoid platform to study individual responses to chemoradiation. Nat Med 2019, 25, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gong, T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Colorectal cancer organoid models uncover oxaliplatin-resistant mechanisms at single cell resolution. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2022, 45, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Berical, A.; Lee, R.E.; Lu, J.; et al. A multimodal iPSC platform for cystic fibrosis drug testing. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Zhang, X.; Ge, Q.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of HBsAg inhibits proliferation and tumorigenicity of HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Cell Biochem 2018, 119, 8419–8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logun, M.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; et al. Patient-derived glioblastoma organoids as real-time avatars for assessing responses to clinical CAR-T cell therapy. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, B.; Muthugounder, S.; Jambon, S.; et al. Preclinical assessment of the efficacy and specificity of GD2-B7H3 SynNotch CAR-T in metastatic neuroblastoma. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.T.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; et al. Organoid Modeling of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Cell 2018, 175, 1972–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Manfrin, A.; Lutolf, M.P. Progress and potential in organoid research. Nat Rev Genet 2018, 19, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, H.M.; Louzada, J.; Bardgett, R.D.; et al. Assessing the Importance of Intraspecific Variability in Dung Beetle Functional Traits. PLoS One 2016, 11, e145598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavazza, A.; Massimini, M. Cerebral organoids and consciousness: how far are we willing to go? . J Med Ethics 2018, 44, 613–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trepagnier, D.M. Human embryonic stem cell research: implications from an ethical and legal standpoint. J La State Med Soc 2000, 152, 616–624. [Google Scholar]

- Lensink, M.A.; Boers, S.N.; Jongsma, K.R.; et al. Organoids for personalized treatment of Cystic Fibrosis: Professional perspectives on the ethics and governance of organoid biobanking. J Cyst Fibros 2021, 20, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.B.; Becker, S.M.; Low, L.A.; et al. Improved Ocular Tissue Models and Eye-On-A-Chip Technologies Will Facilitate Ophthalmic Drug Development. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2020, 36, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, W.; et al. An Automated Organoid Platform with Inter-organoid Homogeneity and Inter-patient Heterogeneity. Cell Rep Med 2020, 1, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, J.J.; Pereda, C.; Adhikari, A.; et al. Deep-learning analysis of micropattern-based organoids enables high-throughput drug screening of Huntington’s disease models. Cell Rep Methods 2022, 2, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Kim, M.; Lee, S.; et al. VONet: A deep learning network for 3D reconstruction of organoid structures with a minimal number of confocal images. Patterns (N Y) 2024, 5, 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Fu, L.; Wu, J.; et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data with structural similarity. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maramraju, S.; Kowalczewski, A.; Kaza, A.; et al. AI-organoid integrated systems for biomedical studies and applications. Bioeng Transl Med 2024, 9, e10641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; et al. AI-enabled organoids: Construction, analysis, and application. Bioact Mater 2024, 31, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, T.; Satija, R. Integrative single-cell analysis. Nat Rev Genet 2019, 20, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; et al. Microfluidic Chip-Based Automatic System for Sequencing Patient-Derived Organoids at the Single-Cell Level. Anal Chem 2024, 96, 17027–17036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagella, P.; Soderholm, S.; Nordin, A.; et al. The time-resolved genomic impact of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cell Syst 2023, 14, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montorsi, L.; Pitcher, M.J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Double-negative B cells and DNASE1L3 colocalise with microbiota in gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo Gonzalez-Blas, C.; Matetovici, I.; Hillen, H.; et al. Single-cell spatial multi-omics and deep learning dissect enhancer-driven gene regulatory networks in liver zonation. Nat Cell Biol 2024, 26, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Muto, Y.; Ledru, N.; et al. A single-cell multiomic analysis of kidney organoid differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2075268176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Lim, S.; et al. Modeling Clinical Responses to Targeted Therapies by Patient-Derived Organoids of Advanced Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 4397–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulcaen, M.; Kortleven, P.; Liu, R.B.; et al. Prime editing functionally corrects cystic fibrosis-causing CFTR mutations in human organoids and airway epithelial cells. Cell Rep Med 2024, 5, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Fujimori, N.; Ichihara, K.; et al. Patient-derived organoids of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma for subtype determination and clinical outcome prediction. J Gastroenterol 2024, 59, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).