3.1. Shrinkage Behavior of 17-4PH Tapes

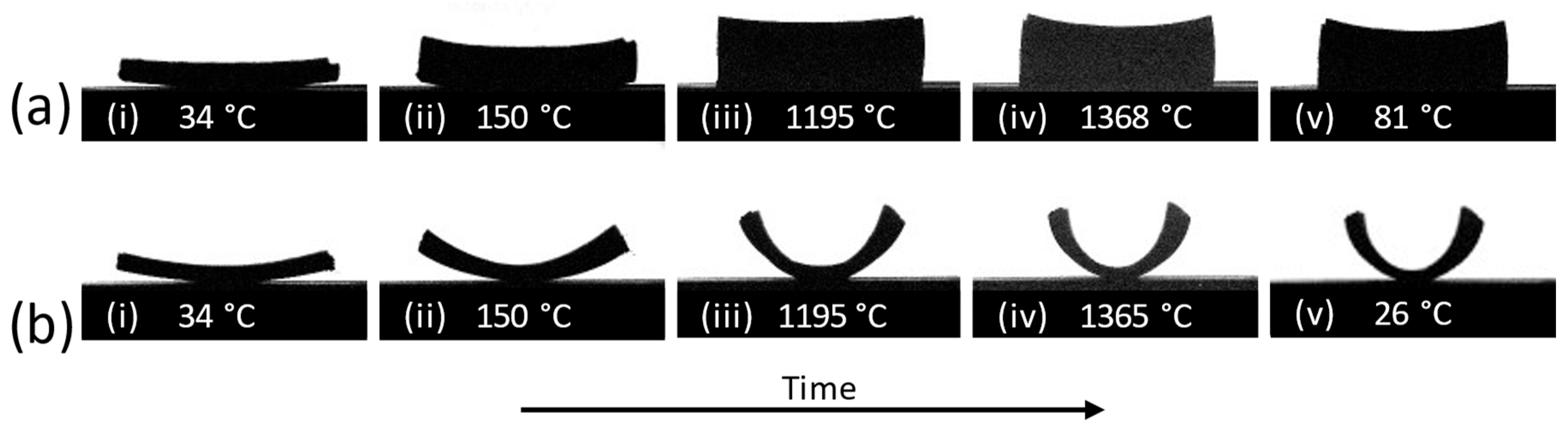

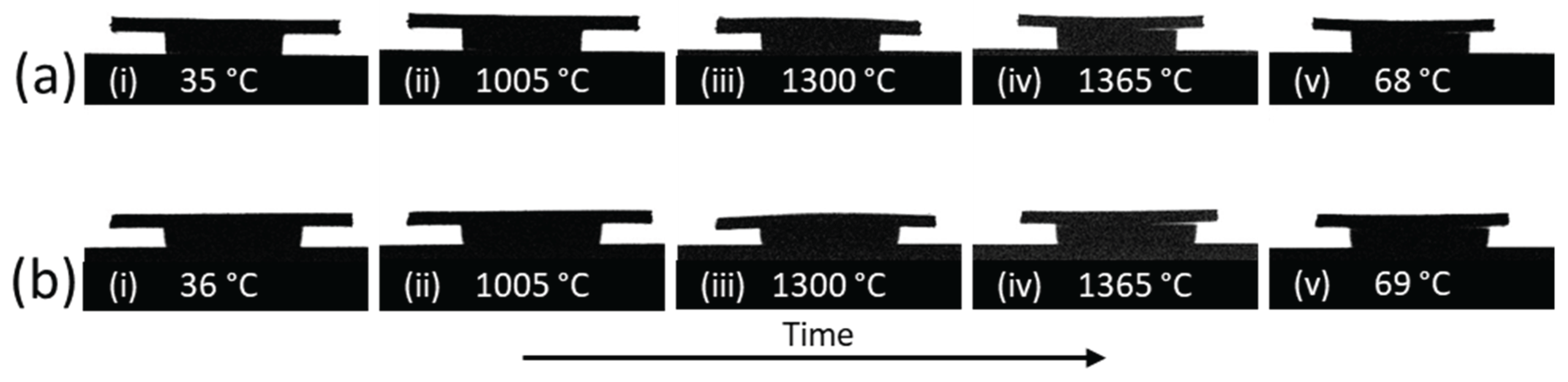

Figure 5 shows the silhouettes for two lying 17-4PH tapes measured in the optical dilatometer at selected temperatures.

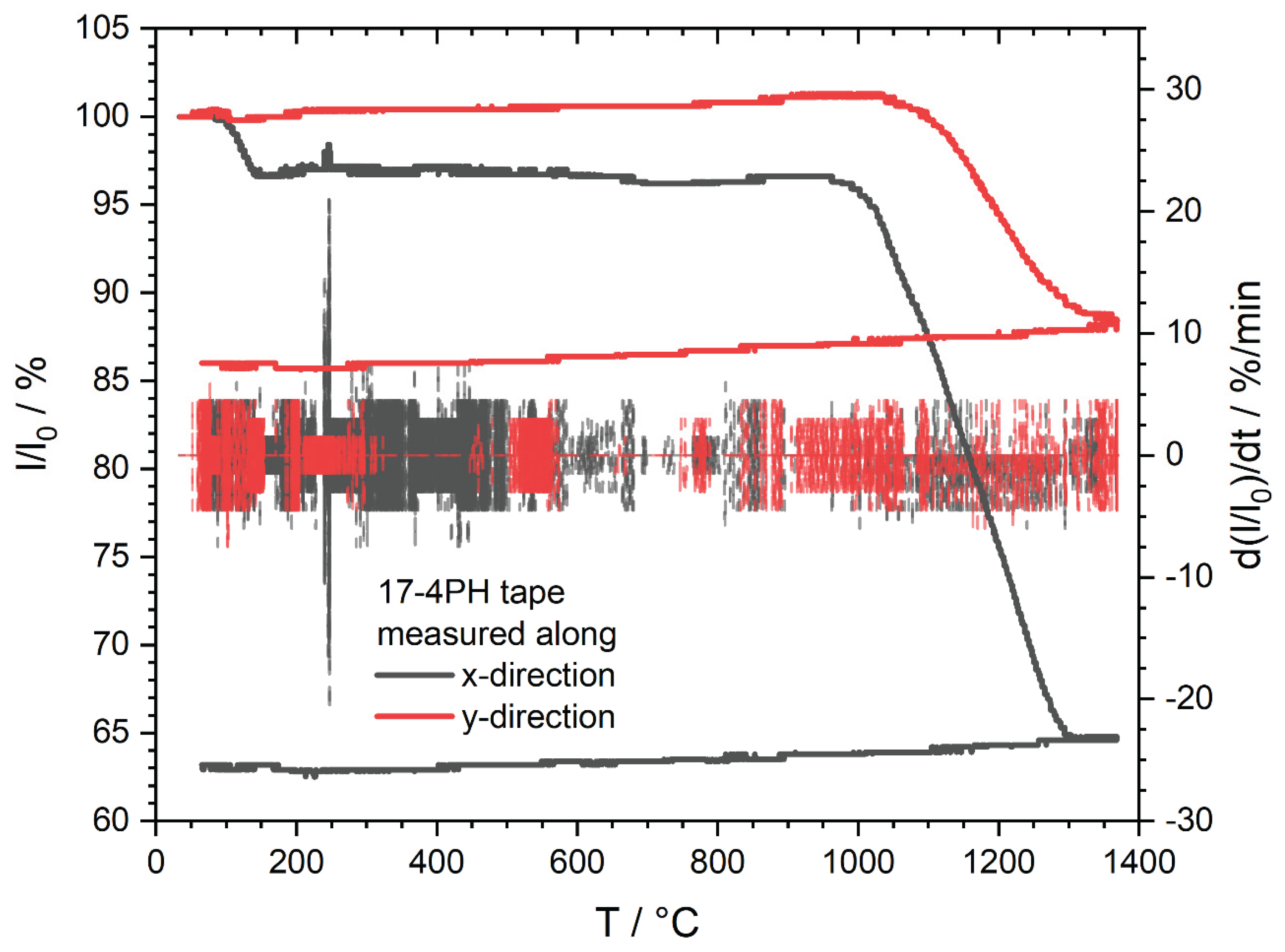

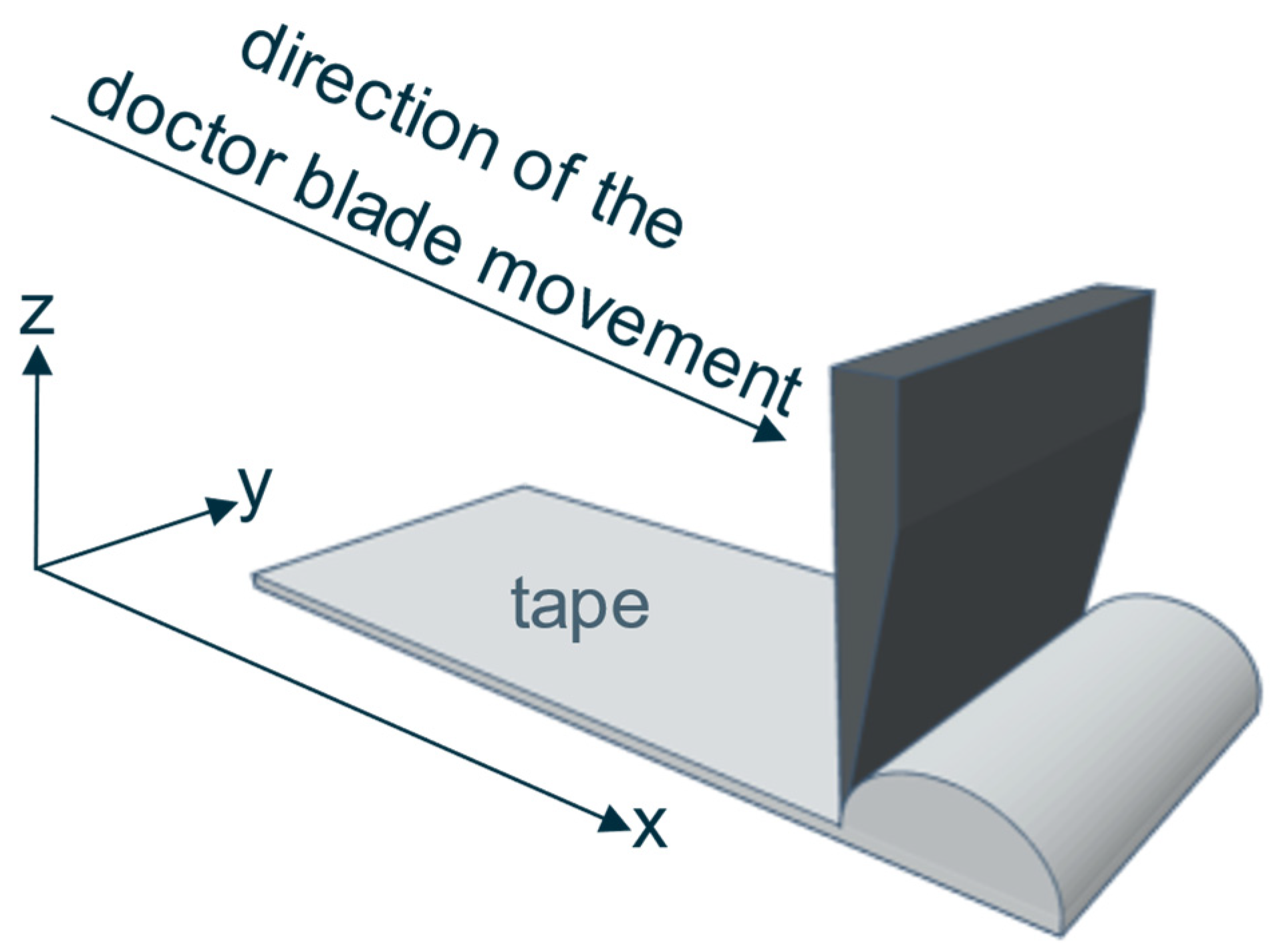

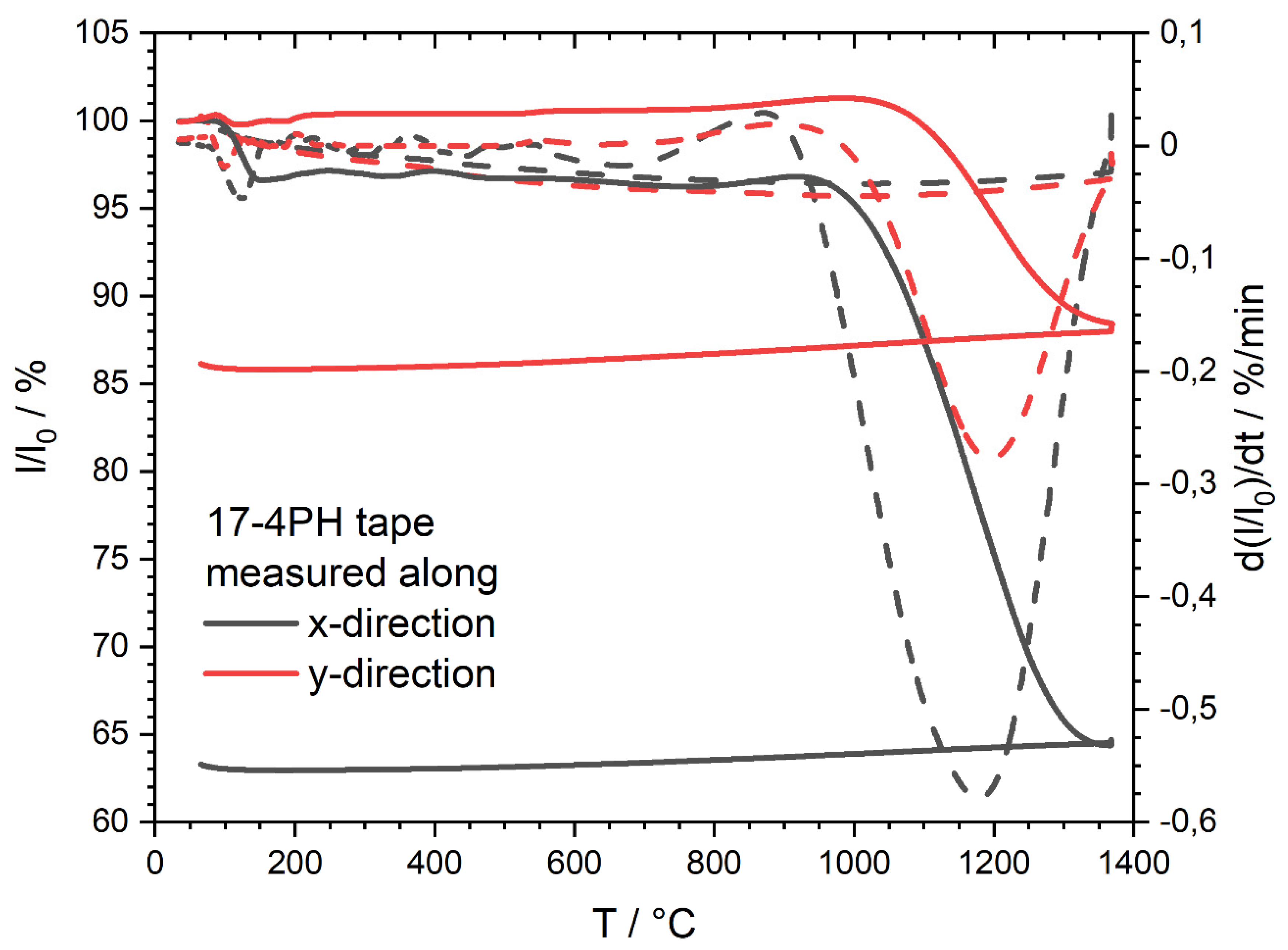

Figure 6 shows the corresponding relative length and relative length change rate. The sample length is measured in the x- and y-directions of the tape. In the x-direction, a change in length of -36.7% is measured, while the measured shrinkage in the y-direction is 13.9%.

For the measurement in the y-direction of the tape, the curve shows the effects of debinding up to around 600 °C with a step at around 100 °C (approximately 1%), where the organic starts to soften. Shrinkage starts at around 980 °C. Shrinkage is not complete at the beginning of the isothermal period and continues to increase during the dwell time.

In the x-direction, a comparatively more pronounced step (approximately 3.2%) occurs at around 100 °C, followed by similar debinding effects up to 600 °C. Shrinkage starts at about 920 °C. For both directions, the relative length continues to decrease as the sample cools, due to the thermal contraction.

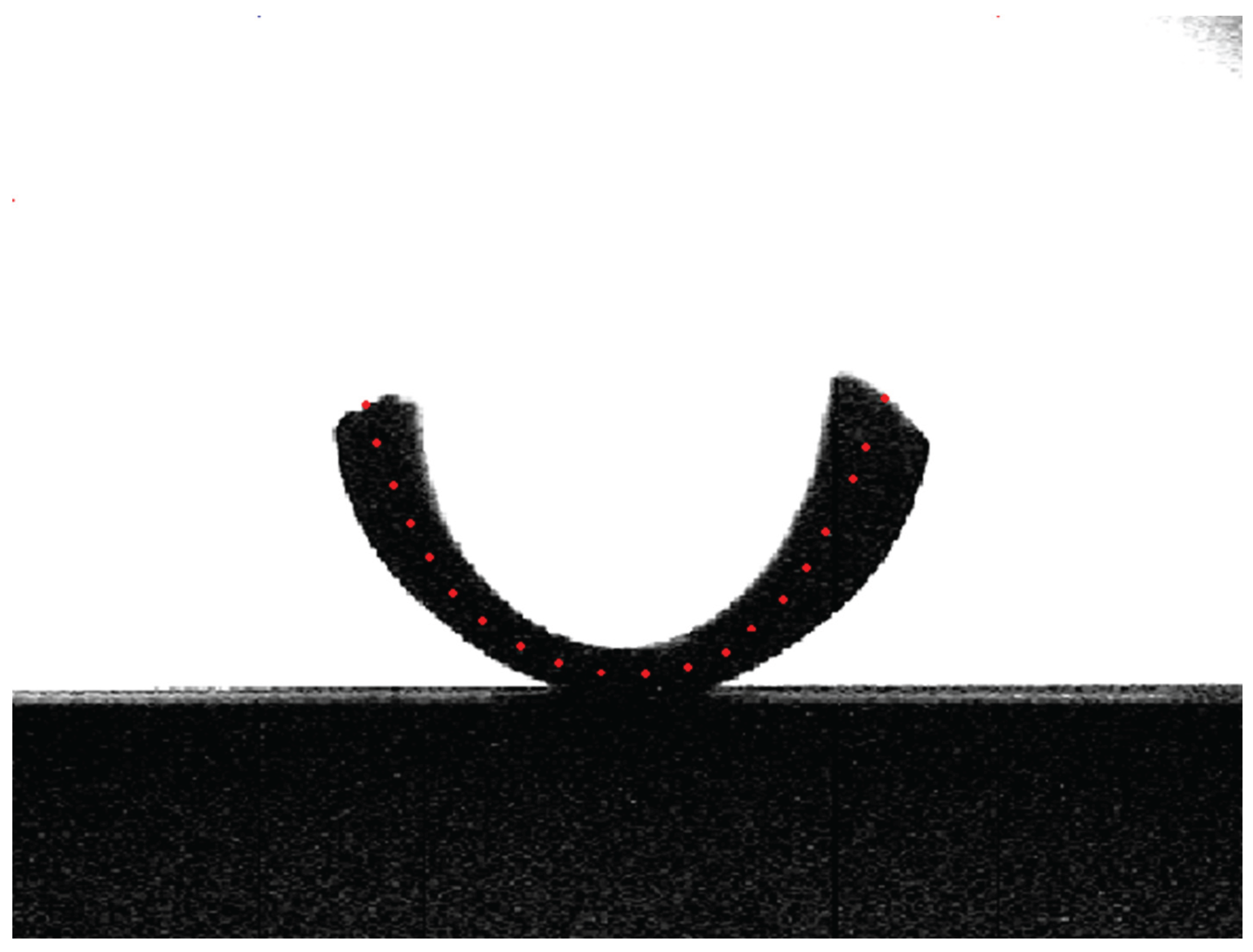

To understand and interpret the curves, it is necessary to look at the silhouettes in

Figure 5. From

Figure 5 (b), picture (ii), it is clear why the measured length of the tape in

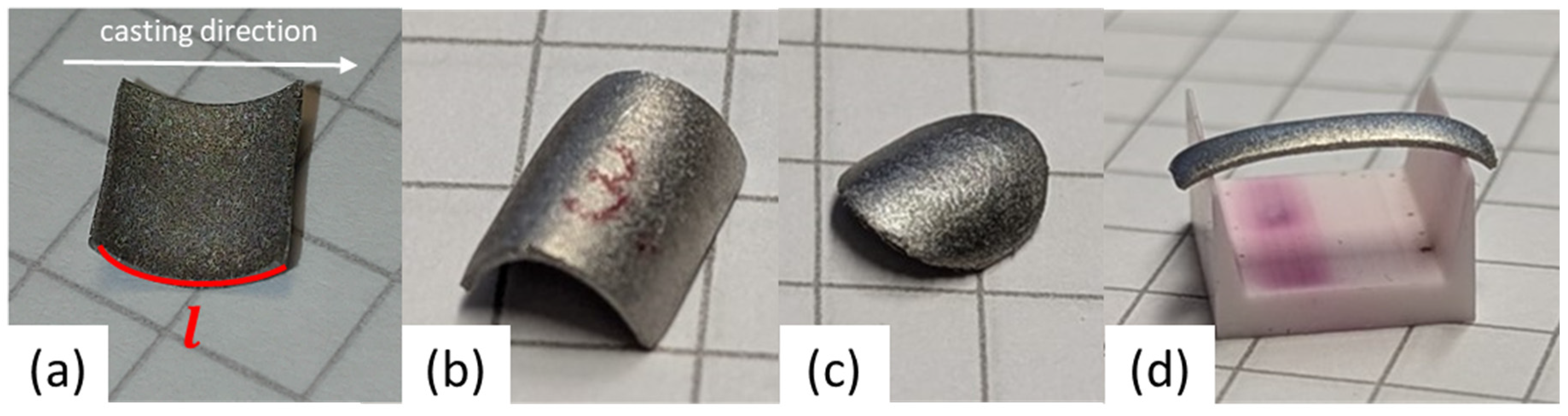

Figure 6 appears to decrease so much in the x-direction of the tape. The 17-4PH tape warps slightly during melting of the organic binder and debinding, and even more during sintering.

Therefore, this change in length is not just shrinkage due to sintering. Measuring the sintered, warped 17-4PH tape with the digital caliper shows an apparent shrinkage of 36.0% in the warped x-direction. This indicates that a correction of the data is necessary to determine the shrinkage in the x-direction caused by sintering (see below).

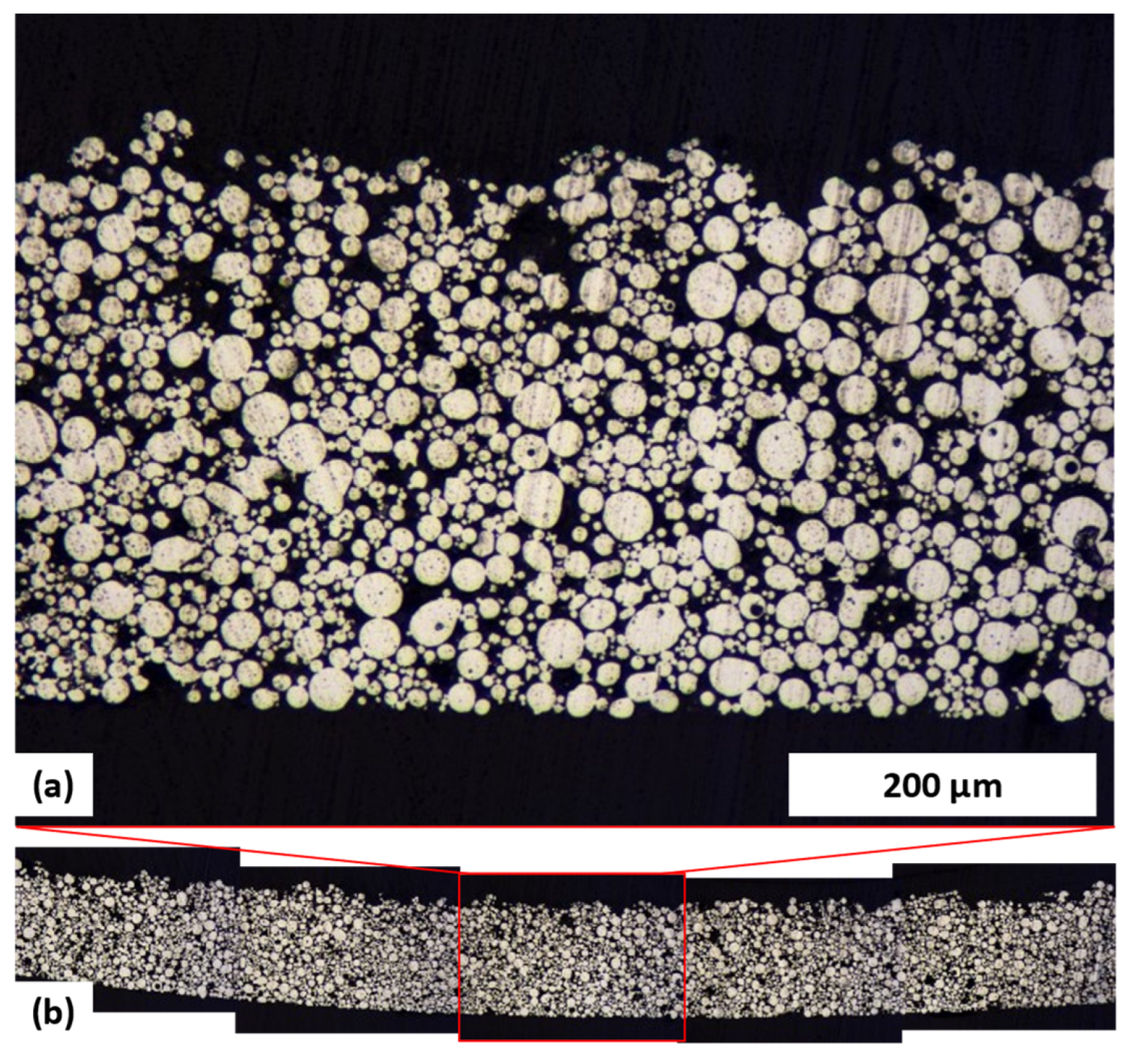

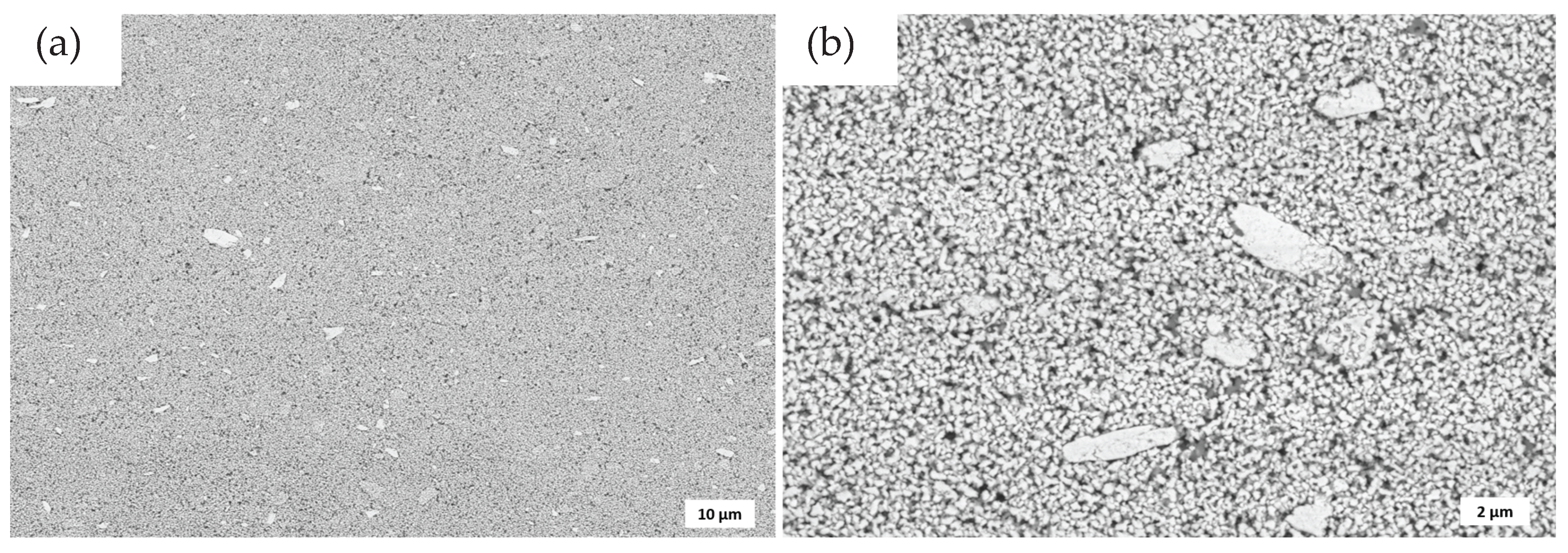

The green steel tape has a smoother, denser bottom (facing the carrier tape) and a rough, less dense top side (compare

Figure 4 (a) and (b),

Figure 7).

Due to softening or melting of the organic components, a slight warpage of the entire edge of the tape in direction of the less dense tape side occurs. The abrupt change in length at approximately 100 °C is associated with this warpage process. The pictures (ii) in

Figure 5 (a) and (b) show the samples at 150 °C when the softening of the organic components was complete. Long-chain molecules, such as the PVA binder used, probably have a higher degree of polymer orientation and are stretched along the casting direction by the doctor blade shear [

30]. As a result, the tape raised slightly more in the x-direction, which means that the tape is pre-embossed in the x-direction after debinding. It is assumed that the resulting state of stress will be conserved during the drying process and is reduced by a deformation of the steel tape as solid organic binder components are melted during heating (such stress relaxation combined with linear shrinkage is observed for aging alumina tapes [

30]). This warpage reduces the recorded sample length and explains why the relative length decreases even before sintering. The warpage of a debinded sample remains stable during cooling. This can be seen in

Figure 7 for a 17-4PH tape that has been debinded and pre-sintered at 1000 °C without dwell time or external loading and has retained its warpage.

In addition, the strong warpage during sintering is also caused by the production process of the tapes and can be explained by a density gradient over the vertical tape profile. When the suspension is applied to the carrier tape during production, the steel particles show different sedimentation behavior depending on the particle size and shape. Consequently, an increase in porosity is observed from the bottom to the top of the tape (

Figure 7). Due to the higher particle concentration on the bottom side caused by the sedimentation process during casting and drying, this region shows less in-plane shrinkage during sintering. In conjunction with the pre-embossing of the tape in the x-direction during debinding, results in the observed warpage.

The described warpage in the x-direction occurred independently of the orientation or position of the sample in the furnace. Experimental influences, such as temperature gradients or magnetic alignment of the sample by the furnace magnetic field (below 600 °C, during binder burnout, 17-4PH is magnetizable) can thus be excluded. Experiments in the optical dilatometer were performed with different flat sample geometries and sample positioning. Round samples as well as strip-shaped samples always showed the described strong warpage to the rough, less dense side in the casting direction, independent of the upward or downward orientation of the less dense side, i.e. the deformation of the sample also takes place against the gravity.

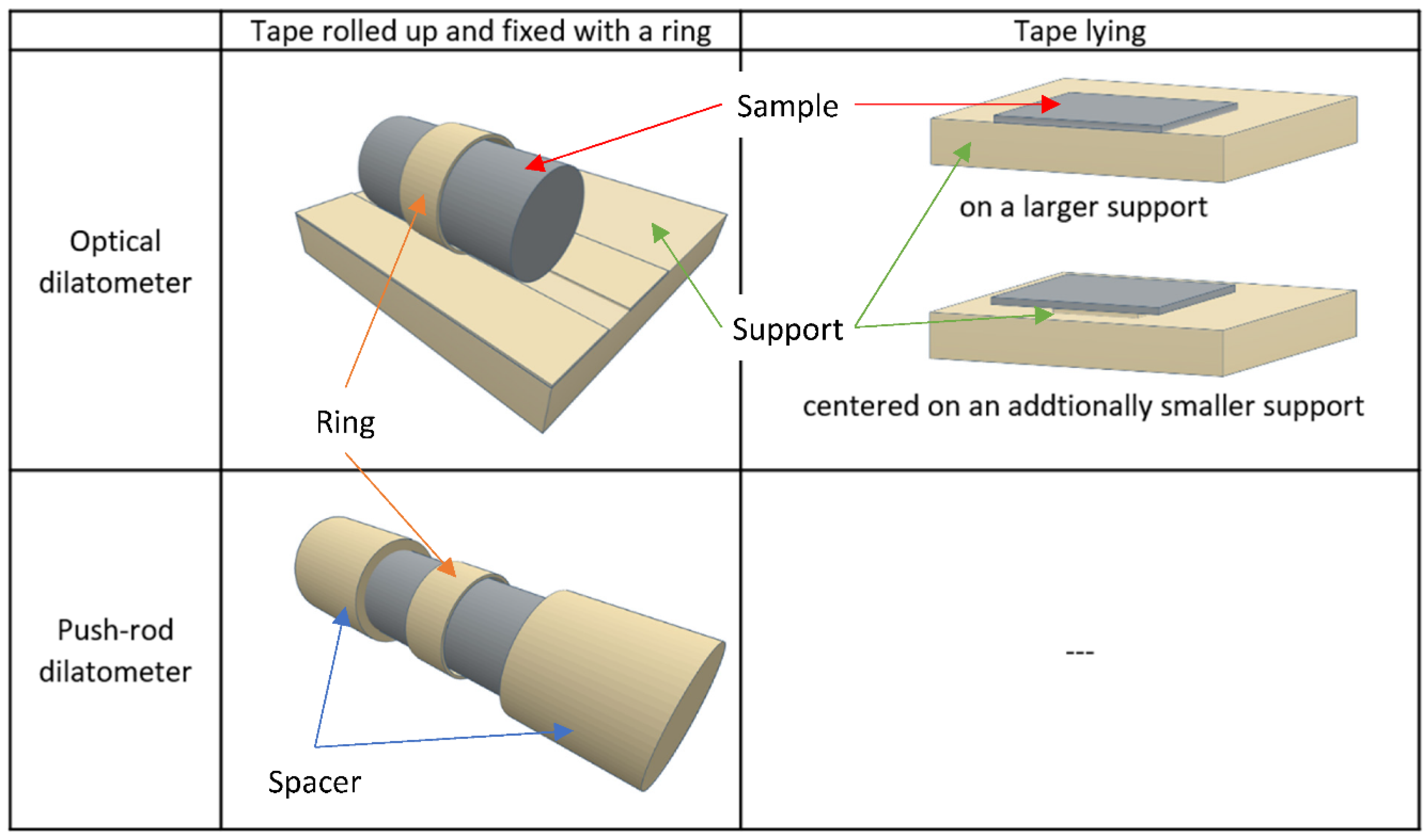

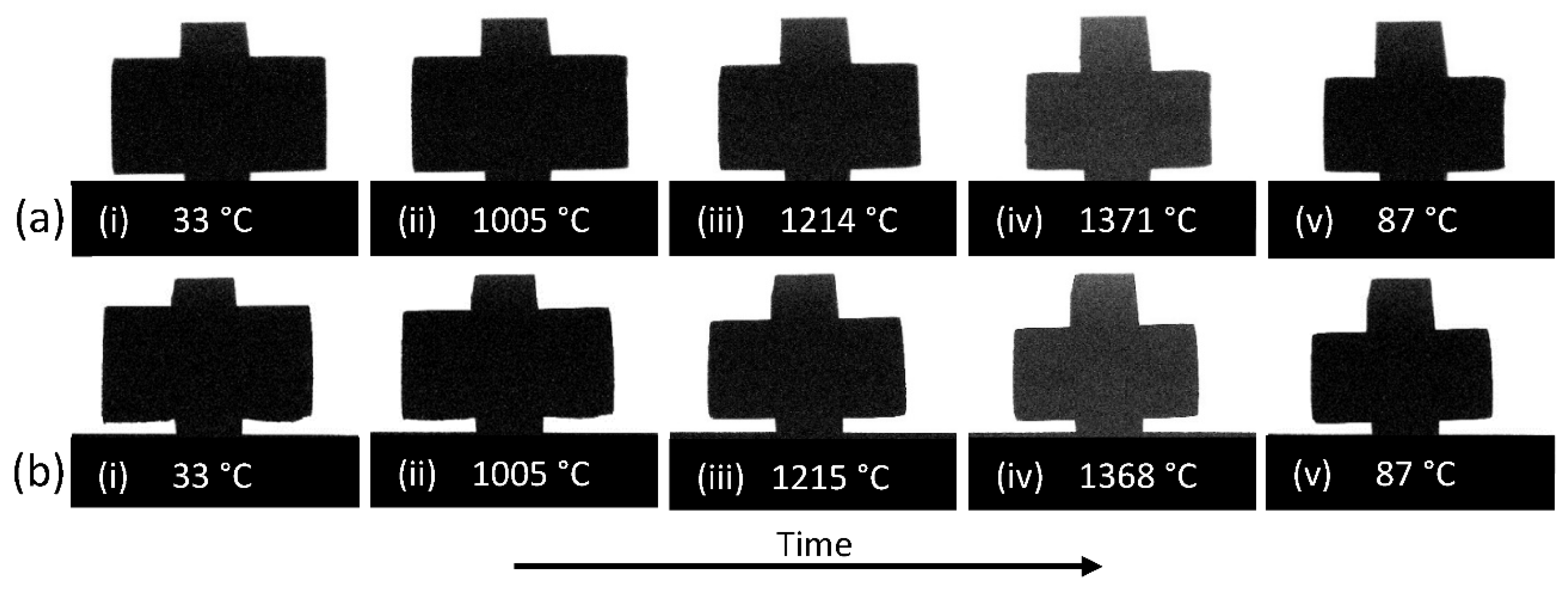

Figure 4 shows examples of the warpage behavior of steel tapes with different tape geometries and experimental arrangements.

In order to prevent the influence of the warpage, the sintering of rolled tapes was tested.

The silhouettes to the shrinkage measurements are shown in

Figure 8. The rolled 17-4PH tape is fixed in the center with a vertical standing ring. Over temperature and time, the rolled tape shrinks due to sintering, while the ring remains in place without changing its shape.

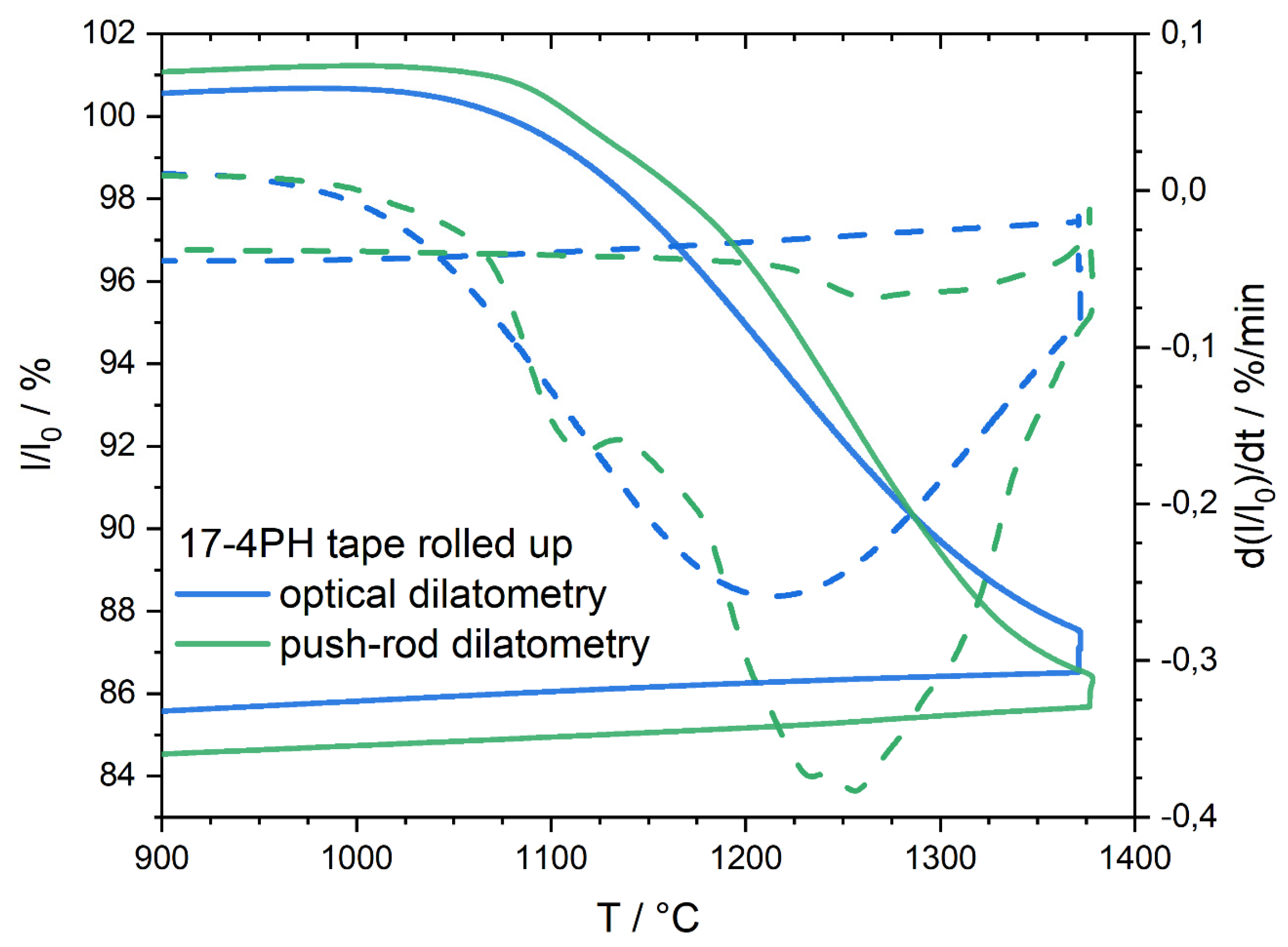

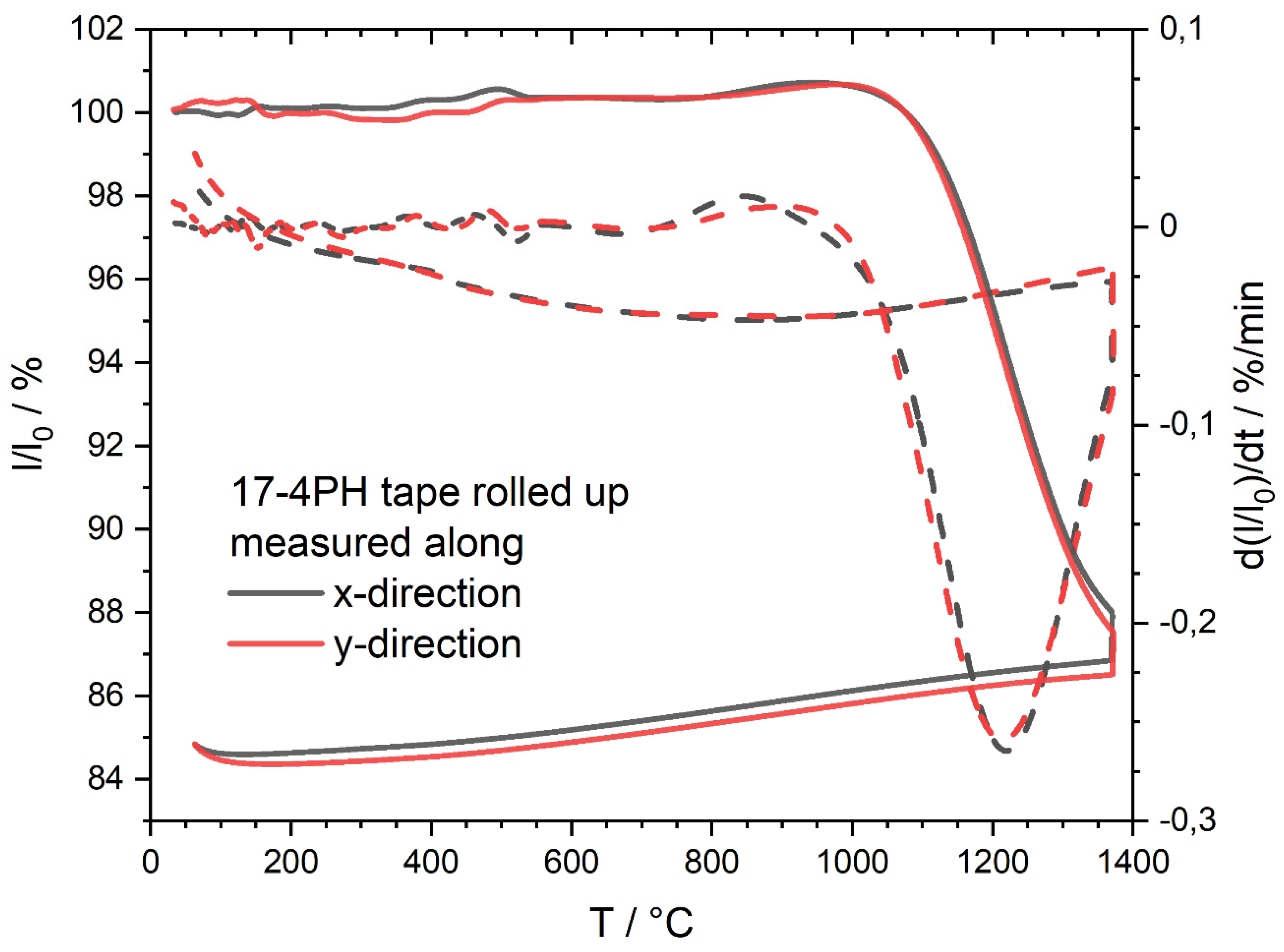

The corresponding relative length and relative length change rate curves of the rolled 17-4PH tapes measured by optical dilatometry are shown in

Figure 9. The black and red curves were determined by measuring the change in sample length along the x- and y-directions of the tape, respectively. With this type of sample preparation, the 17-4PH tapes show very similar sintering behavior in both directions of the tape. The total shrinkage for both measurements is 15.2%. This means that the shrinkage of the rolled tapes is slightly greater than the values measured for the flat tapes (

Figure 6). The wobbling of both curves up to around 600 °C can again be attributed to the debinding process of the tapes. In the y-direction, the debinding behavior is similar to that of the lying tape. Shrinkage starts at about 940 °C and 980 °C for the x- and y-direction, respectively. However, it is not possible to accurately determine the sintering initiation temperature for the steel tapes from the optical dilatometry curves (see below). The maximum relative length change rate is observed at about 1220 °C for both directions. The values for both directions are higher than those for the lying tapes. At around 1320 °C the two curves separate slightly, and the tape measured in the y-direction (rolled up in x-direction) appears to shrink slightly more than in the x-direction, but not significantly. The sintering is still pronounced at the dwell time at 1370 °C. During cooling, there are deviations between the two tape directions, but these can be considered similar within the relative resolution of 0.3% of the relative length. The differences are most likely caused by scatter in the experimental data.

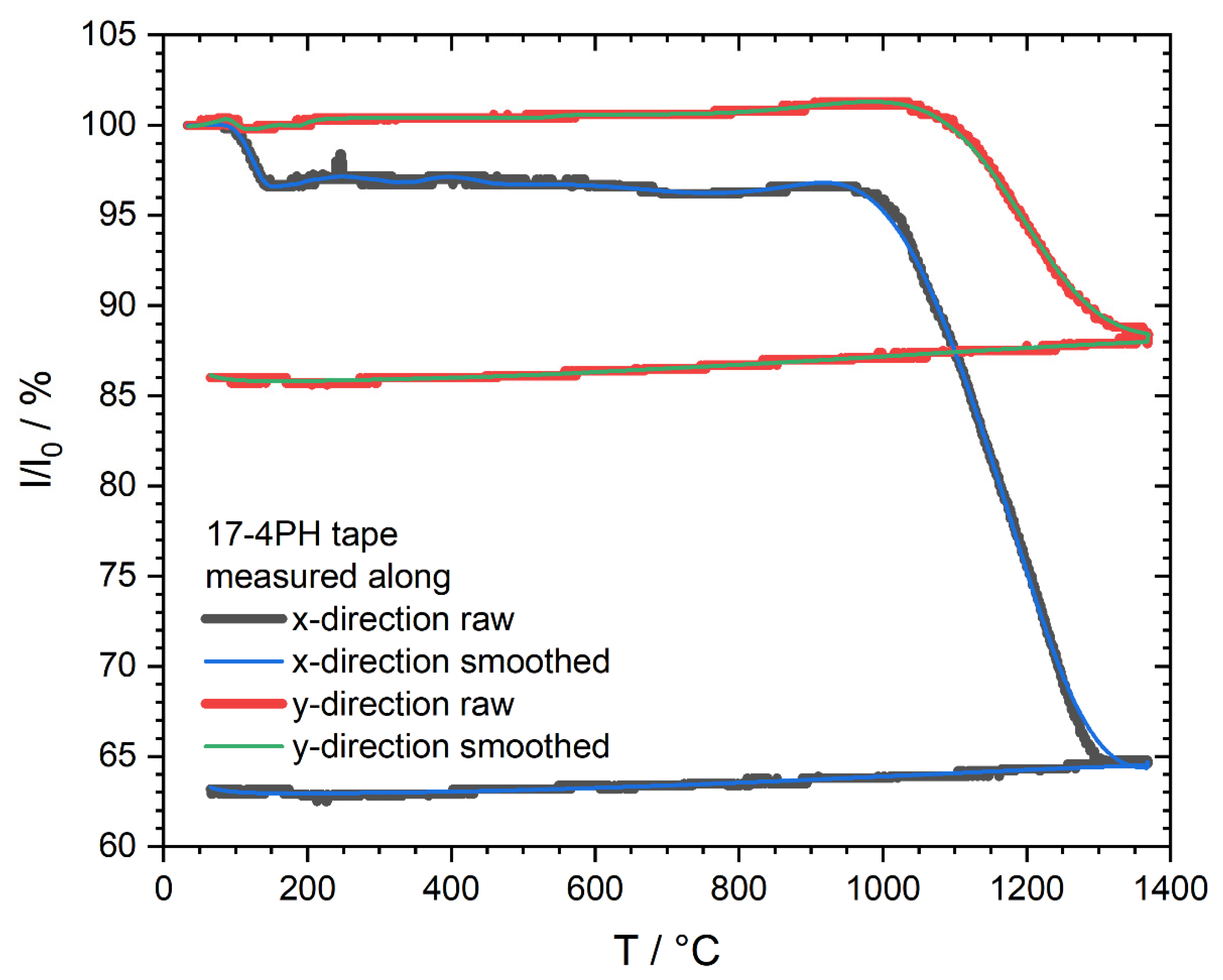

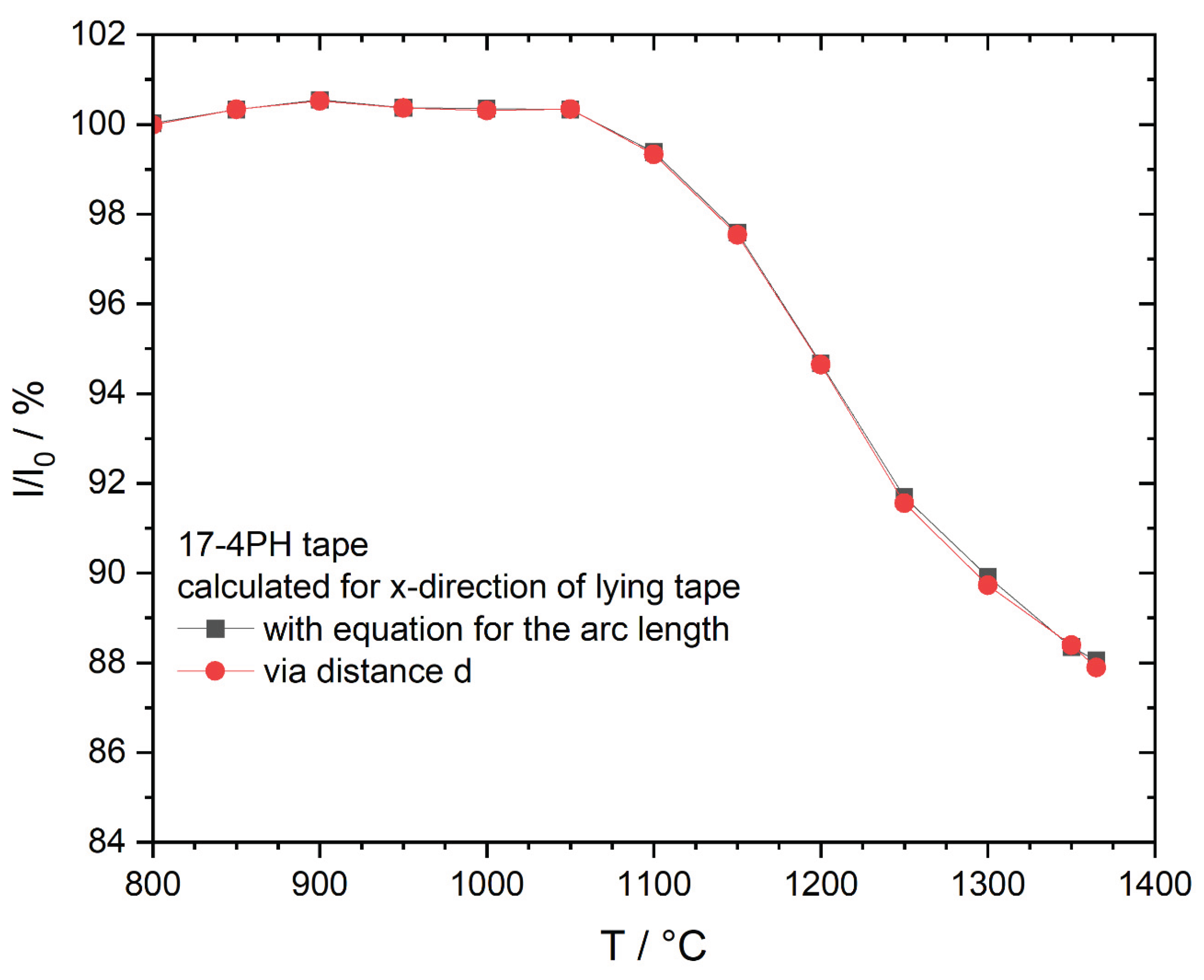

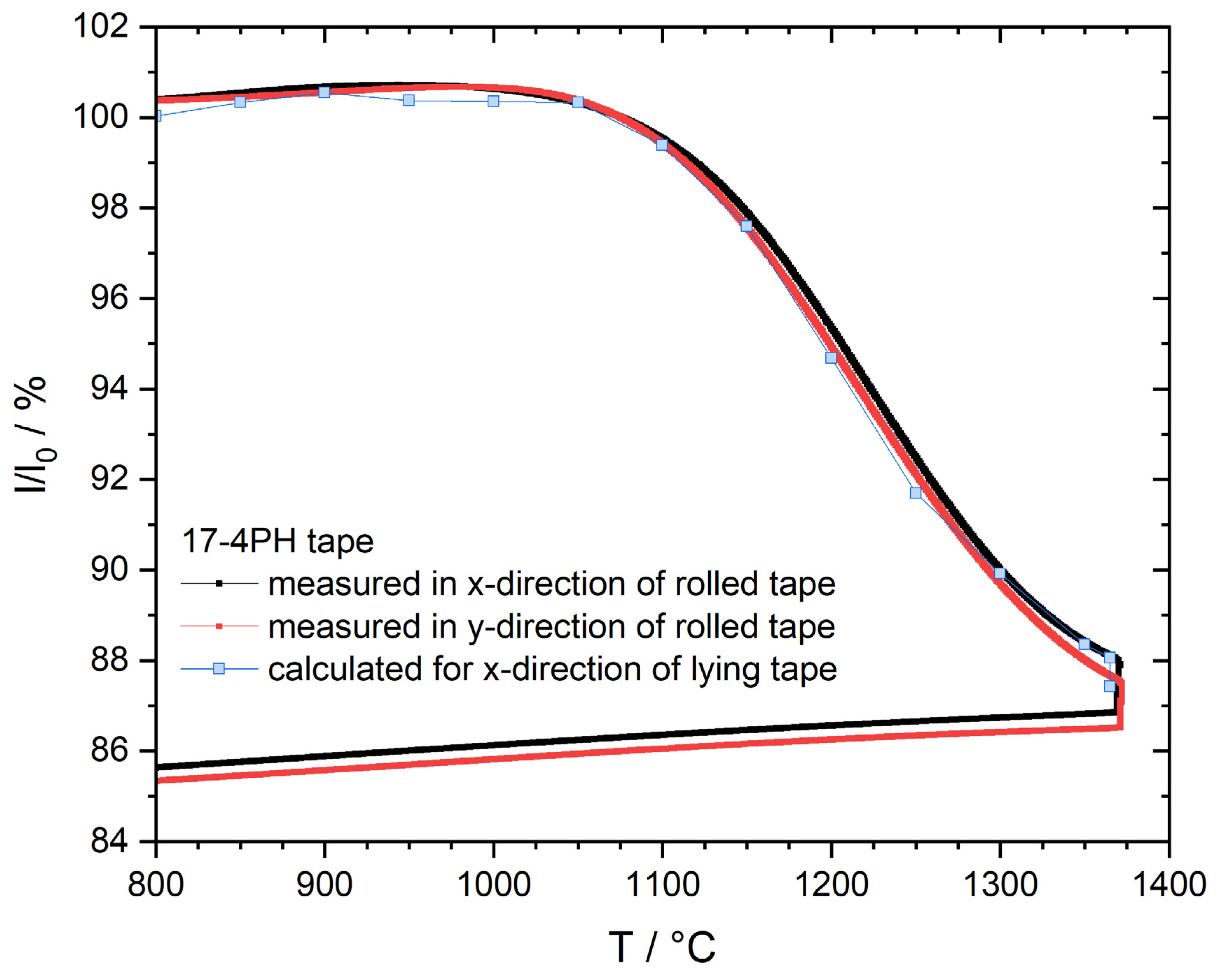

To get a true value for the shrinkage of the 17-4PH tape in the warped x-direction, the approximation as described in the previous

Section 2.5 was used, resulting in a total shrinkage of 13.3%. The corrected curve for the x-direction is shown in

Figure 10. It is compared to the measured values of the rolled 17-4PH tape in the x- and y-directions from

Figure 9. The deviations between the calculated and measured values can be neglected in terms of measurement uncertainty. This indicates that there is no or only a negligible anisotropic shrinkage in the x- and y-directions of the 17-4PH tape when warpage is prevented. However, the shrinkage caused by sintering must be separated from the overall length change by additional processing of the warped tape data. Alternatively, it can be measured on rolled tapes that do not show warpage of the measured dimension. The higher shrinkage of 13.9% in the y-direction of the lying 17-4PH tape compared to its calculated value in the x-direction is explained by the position of the tape at the beginning. The steel tape was slightly bent and lay slightly twisted until sintering (see

Figure 5 (a)).

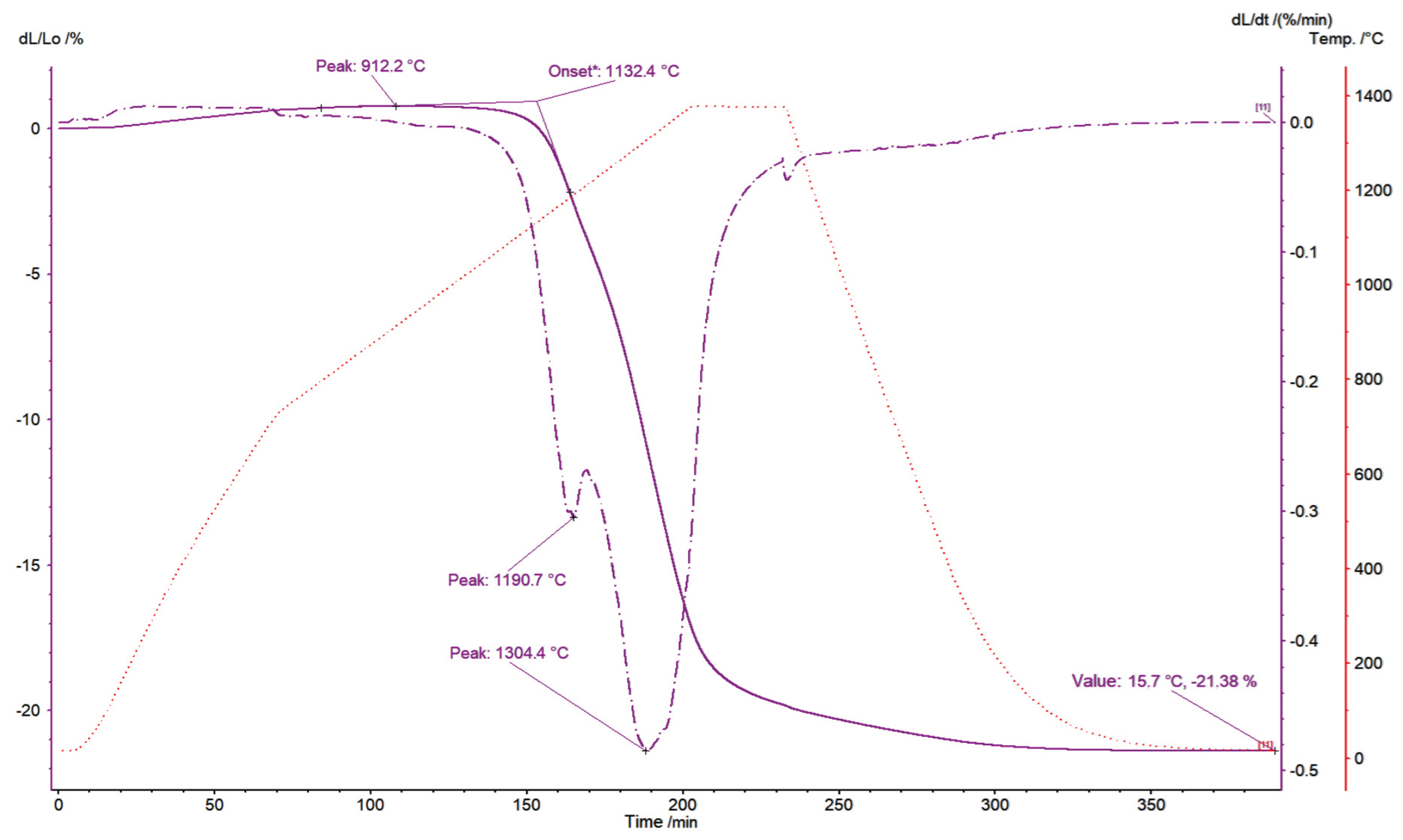

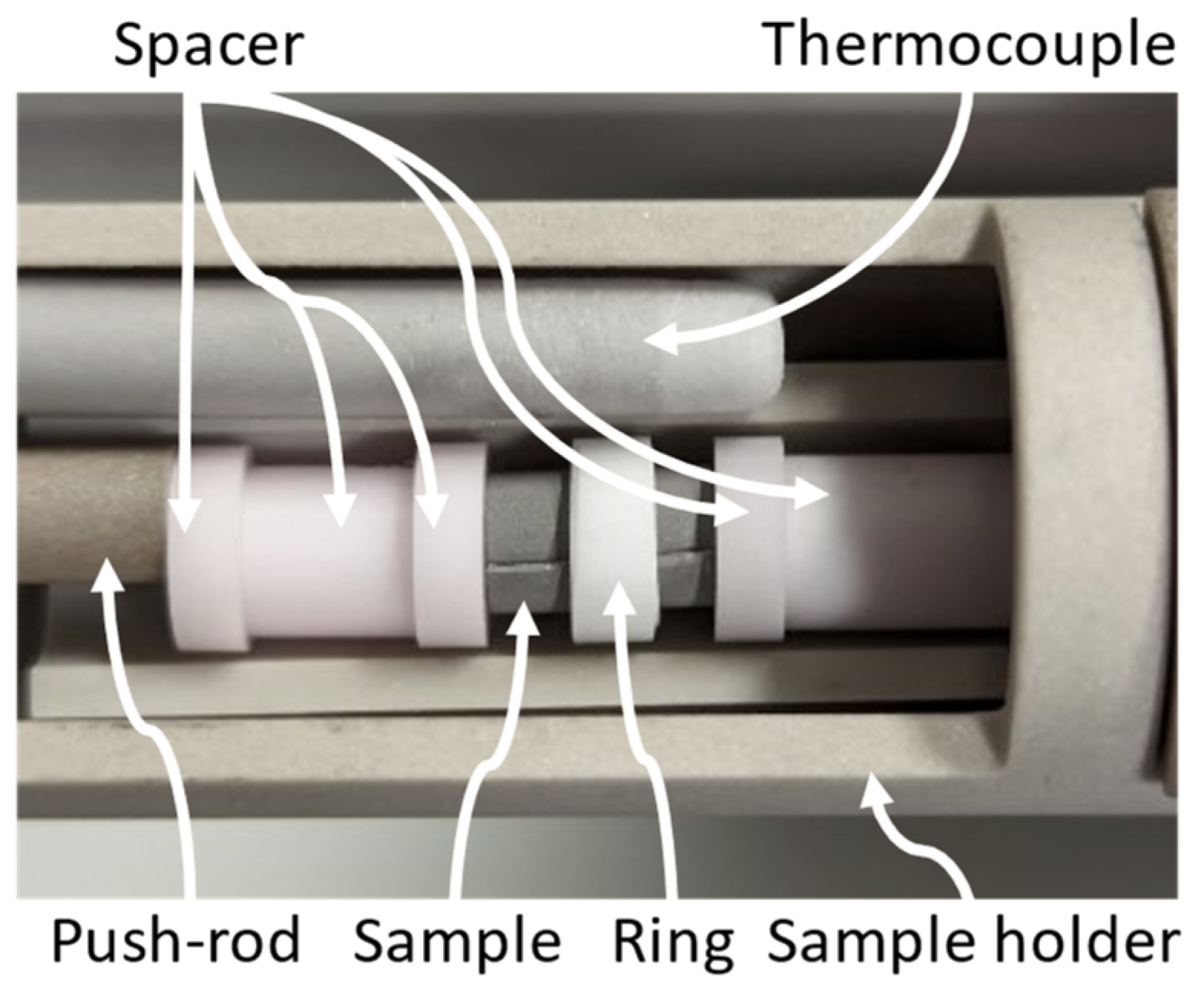

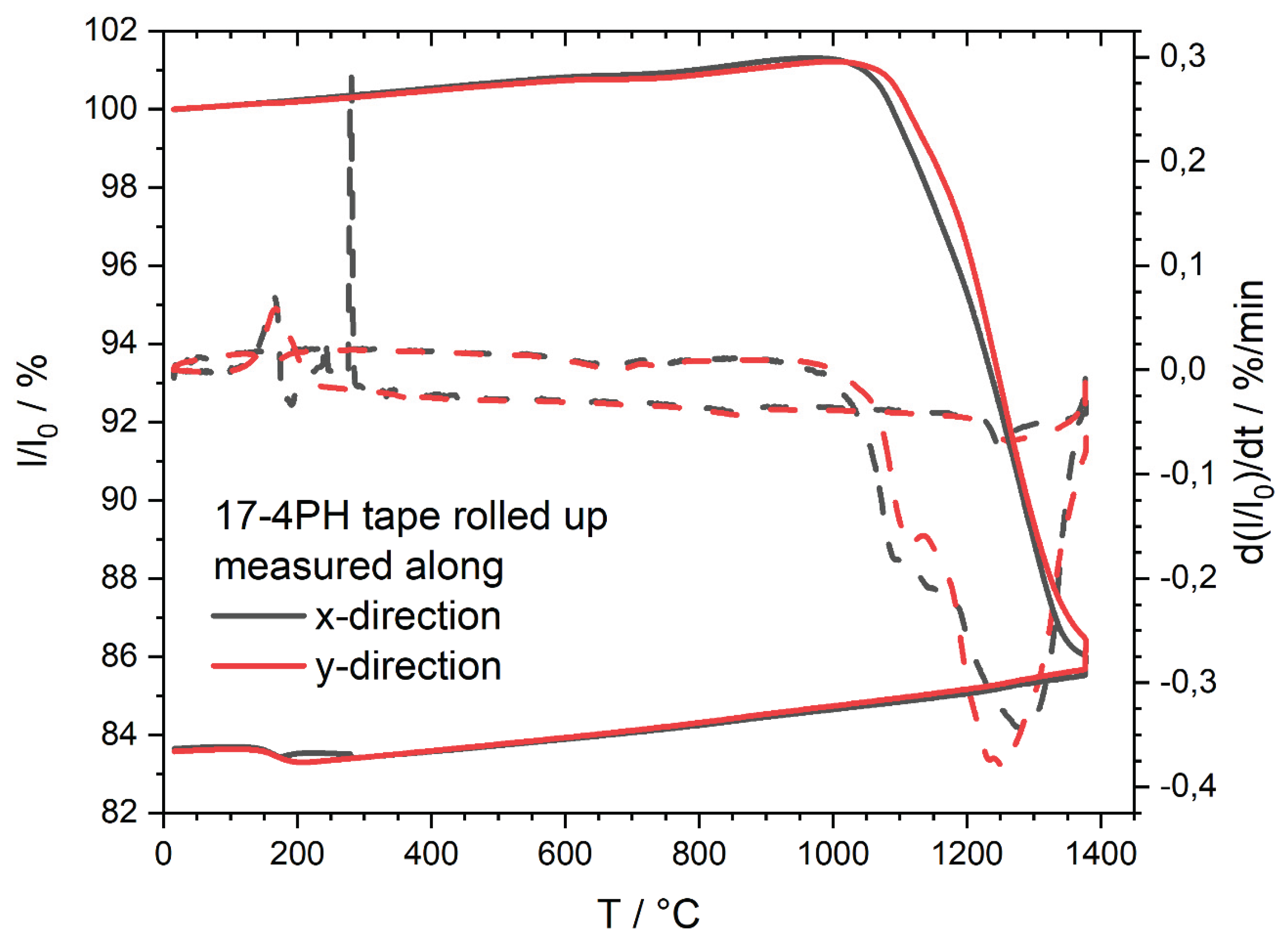

The samples of the rolled tapes can also be analyzed in the push-rod dilatometer. The measurement results for 17-4PH tapes are shown in

Figure 11. The sintering behavior is very similar in both directions, ending in a shrinkage of 16.4% for both directions of the tape. Since the samples were debinded prior to the push-rod dilatometric measurements, no similar effects of debinding are observed as with the not debinded samples from the optical dilatometry. The slight downward slope at around 630 °C indicates the austenitization (γ-phase) of 17-4PH. The phase transition is followed by a continuous increase due to thermal expansion until sintering starts at about 970 °C and 1000 °C for the x- and y-directions, respectively. As with optical dilatometry, it is difficult to determine the correct onset of sintering, so the values shown are for orientation. In contrast to the behavior determined in the optical dilatometer, an additional peak in the relative length change rate occurs at approximately 1120 °C. This could be due to the contact pressure used. The contact pressure accelerates the particle rearrangement in the initial state of sintering. In addition, a flattening of the not perfect cutting edges of the tap may contribute. The contact pressure also leads to a higher relative length change rate and a higher peak temperature for the main maximum compared to the heating microscope. The total shrinkage is also slightly higher than for optical dilatometry (16.4% versus 15.2%), indicating the influence of the contact pressure. The data indicate that the application of the contact pressure does not alter the sintering mechanism. However, it does influence the intensity and temperature ranges of the individual processes. Upon cooling below 200 °C, the γ-α-phase transition (to the martensitic α-phase) of 17-4PH takes place, accompanied by an increase in volume [

29], which could not be clearly determined in the optical dilatometer due to the lower resolution (see

Appendix A in

Figure A3). In the x-direction cooling curve, there is an apparent end of contraction at approximately 300 °C before the phase transition. This is a measurement artifact where the measurement signal has exceeded the measurement range of the push-rod dilatometer.

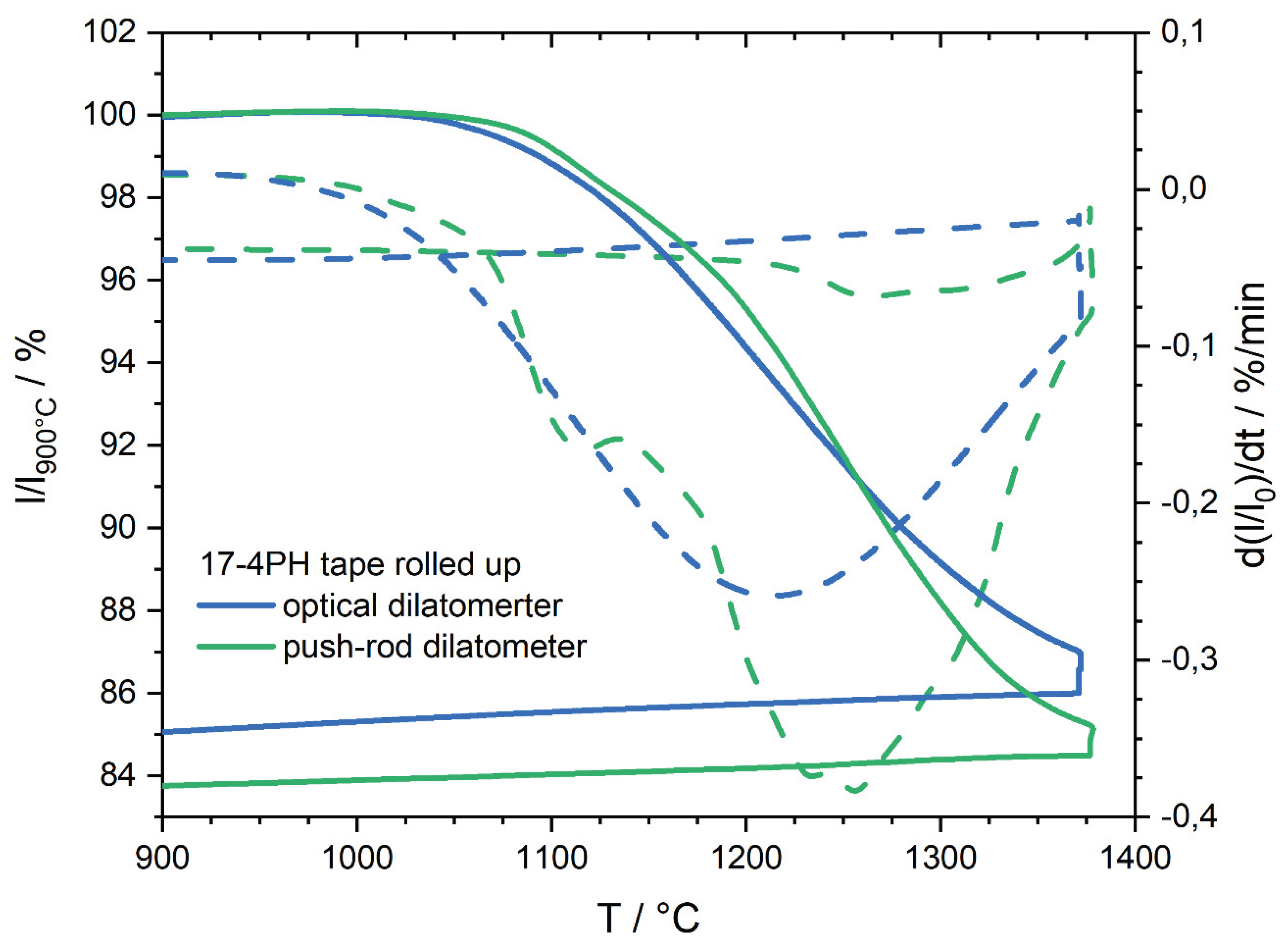

Figure 12 compares the data normalized at 900 °C in the y-direction of rolled up 17-4PH tapes measured by optical dilatometry and push-rod dilatometry. The data used are the same as in

Figure 9 and

Figure 11. The shrinkage between the two types of dilatometers differs by about 1.2% and can be explained by the constant force of 20 cN when measuring with the push-rod dilatometer. The relative length change rate is higher and shows two peaks between 1075 °C and 1300 °C when measured with the push-rod dilatometer, while only one maximum is detected when measured with the optical dilatometer.

Figure C1,

Appendix C compares the two curves when the data are not normalized to 900 °C.

3.2. Shrinkage Behavior of TZ-3YS-E Tapes

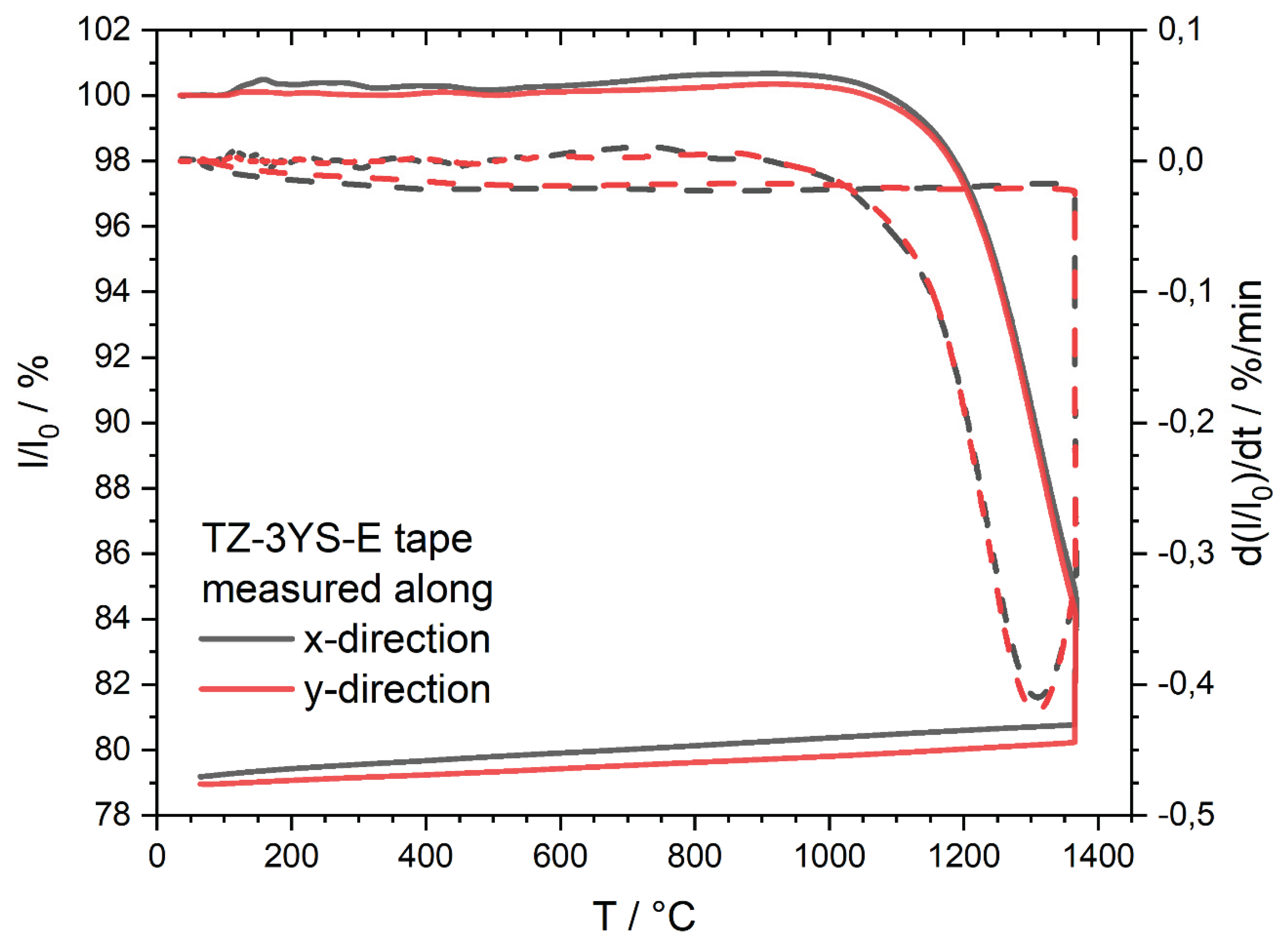

TZ-3YS-E tapes show no significant warpage during sintering as shown in

Figure 13. This indicates a high stability of the TZ-3YS-E suspension due to the much smaller grain size compared to the steel powder.

Figure 14 shows the cross section of a pre-sintered TZ-3YS-E tape at 1000 °C. Regardless of the partly large zirconia agglomerates (bright areas), the zirconia particles and agglomerates are distributed homogeneously over the volume. The small dark gray areas are pores.

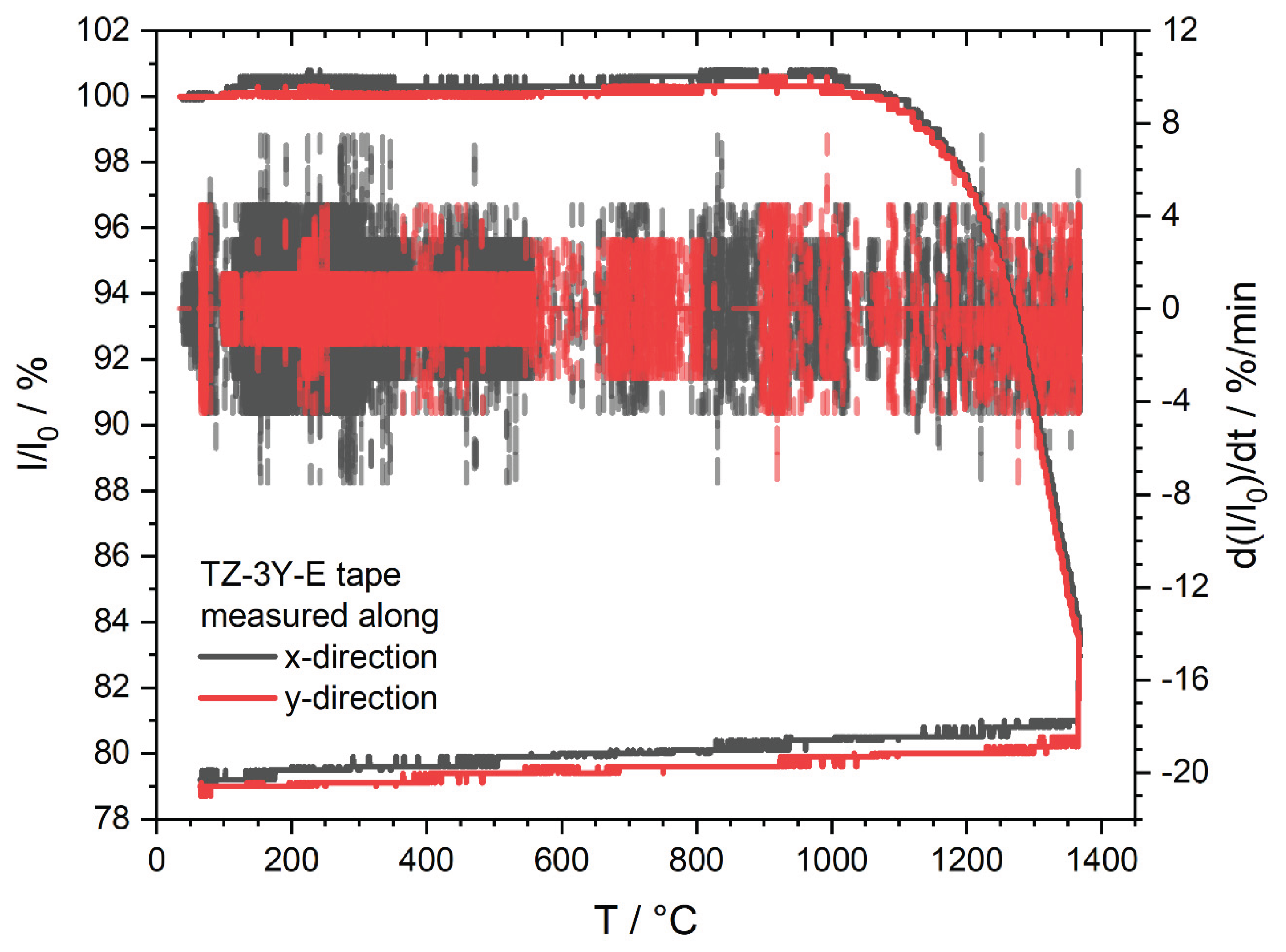

The relative length and relative length change rate for lying free sintering TZ-3YS-E tapes, measured in the optical dilatometer in the x- and y-directions of the tape, are shown in

Figure 15. The general sintering behavior of both directions is similar. The shrinkage is 20.8% and 21.0% for the x- and y-directions, respectively. The observed wobble of the curve is attributed to debinding processes and disappears above 600 °C when debinding is complete. Beyond 600 °C, the thermal expansion of the sample can be observed until sintering starts at around 1000 °C. There is only one peak in the sintering rate, which occurs at approximately 1300 °C.

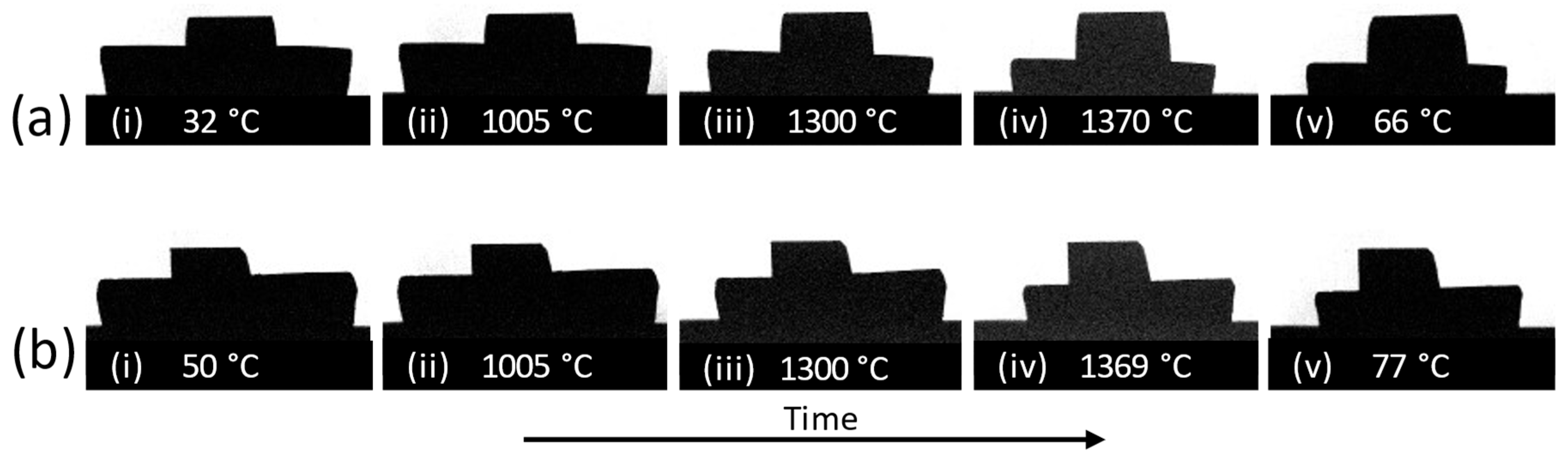

The silhouettes of rolled TZ-3YS-E tapes are shown in

Figure 16. A similar setup is shown as for the rolled 17-4PH tapes, but in addition the lower part of the image is covered by a thicker alumina stripe, which should hold the ring with the rolled tape in its position and provide a better baseline (required by the software) for the measuring of the length.

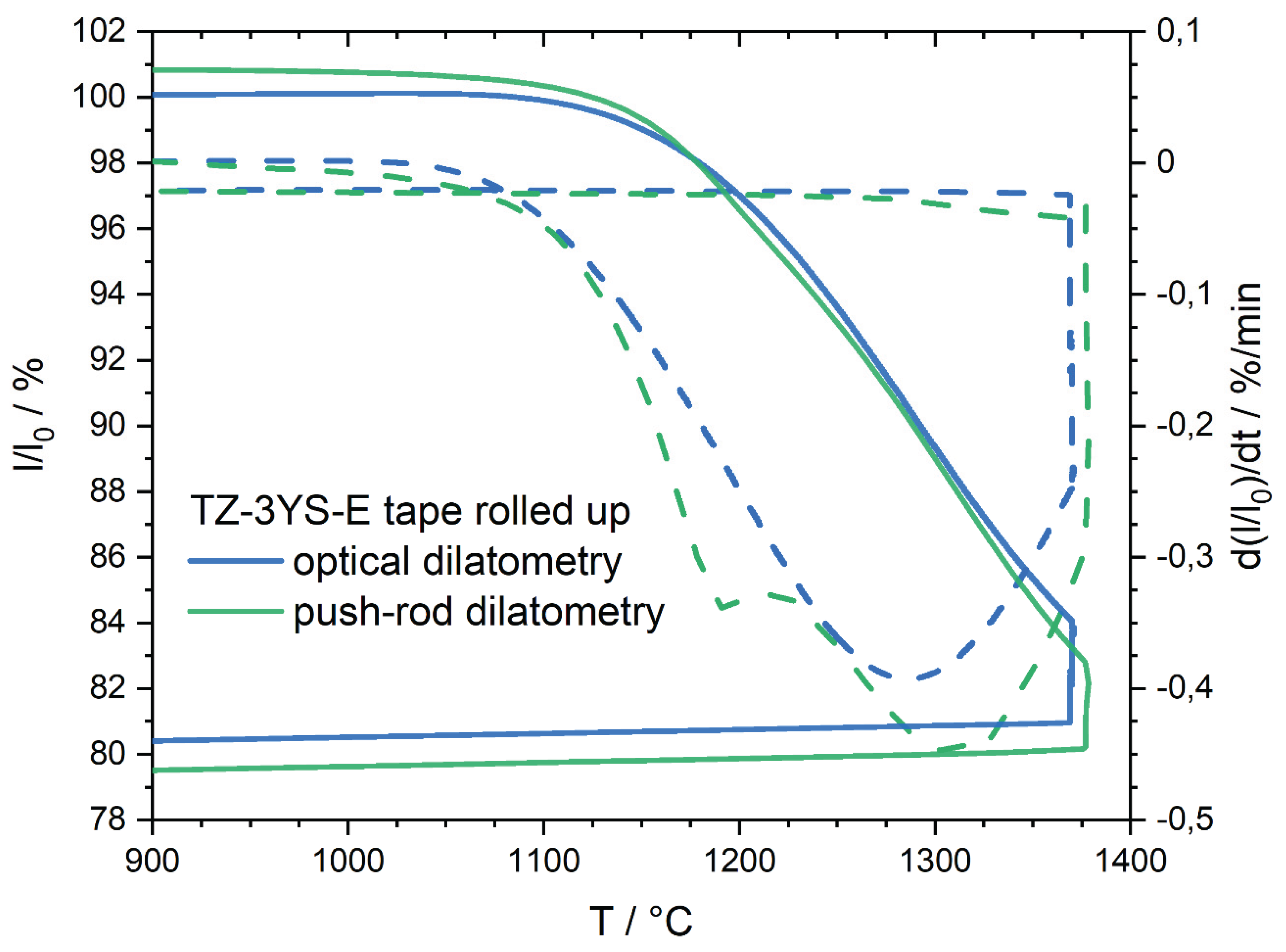

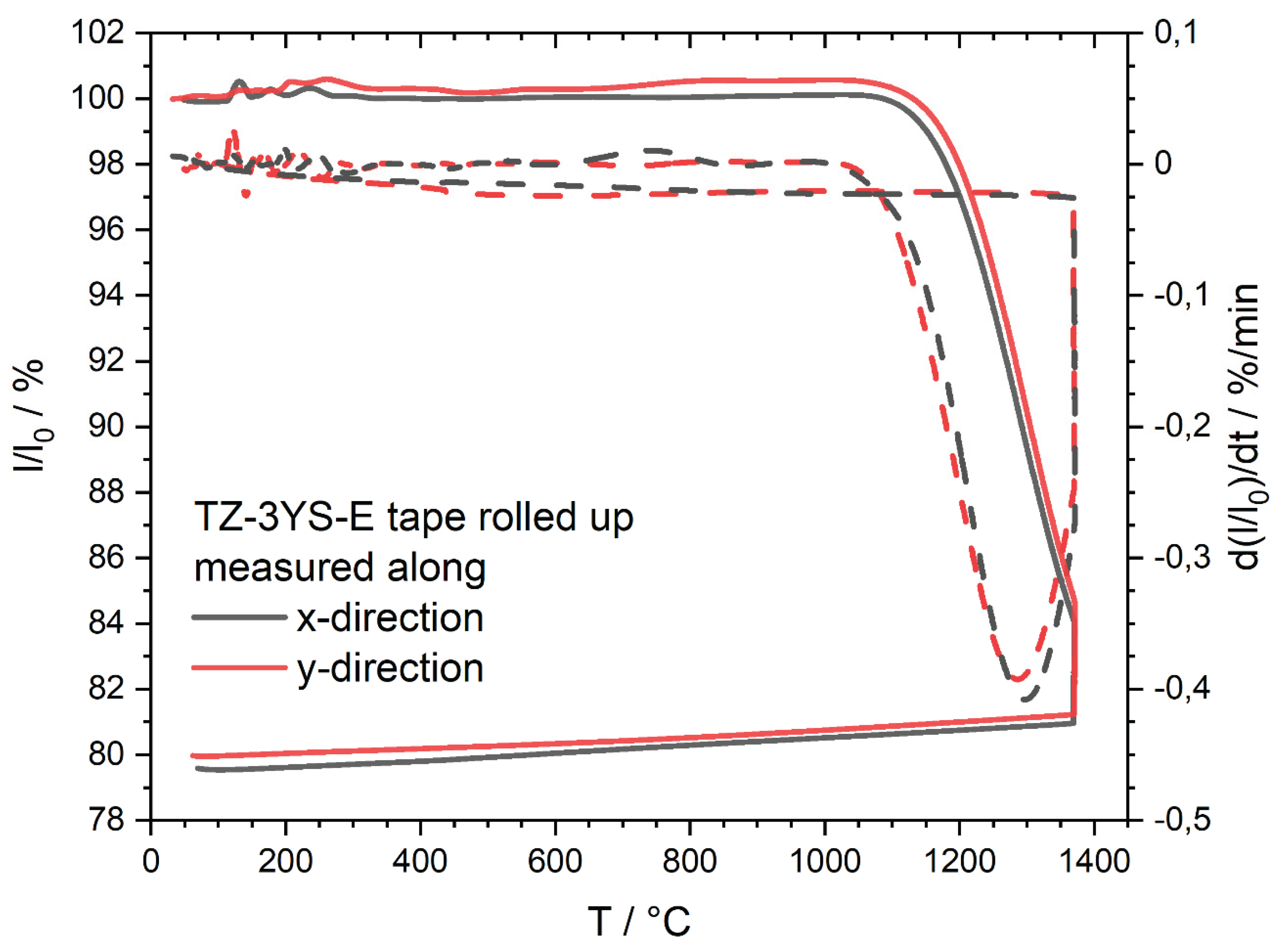

The corresponding curves of the relative length and relative length change rate of the rolled TZ-3YS-E tapes measured by optical dilatometry are shown in

Figure 17. The black and red curves were determined by measuring the sample length in x- and in the y-directions of the tape. As the lying sintered tapes, the rolled tapes show similar sintering behavior for the x- and y-directions with a shrinkage of 20.4% and 20.0%, respectively. However, the shrinkage in the x-direction is slightly greater than that in the y-direction, whereas the opposite was true in the unrolled state. This indicates that these differences are due to the relative resolution of 0.3%, measurement errors, and sample preparation. Again, in both measurements the detected relative length is influenced by the debinding process up to about 600 °C when the organic is removed. After further thermal expansion, the shrinkage process starts at about 1010 °C. Only one pronounced maximum of the sintering rate is observed at approximately 1270 °C and 1290 °C for the x- and y-directions, respectively. These values are close to, but lower than, those of the lying ceramic tapes.

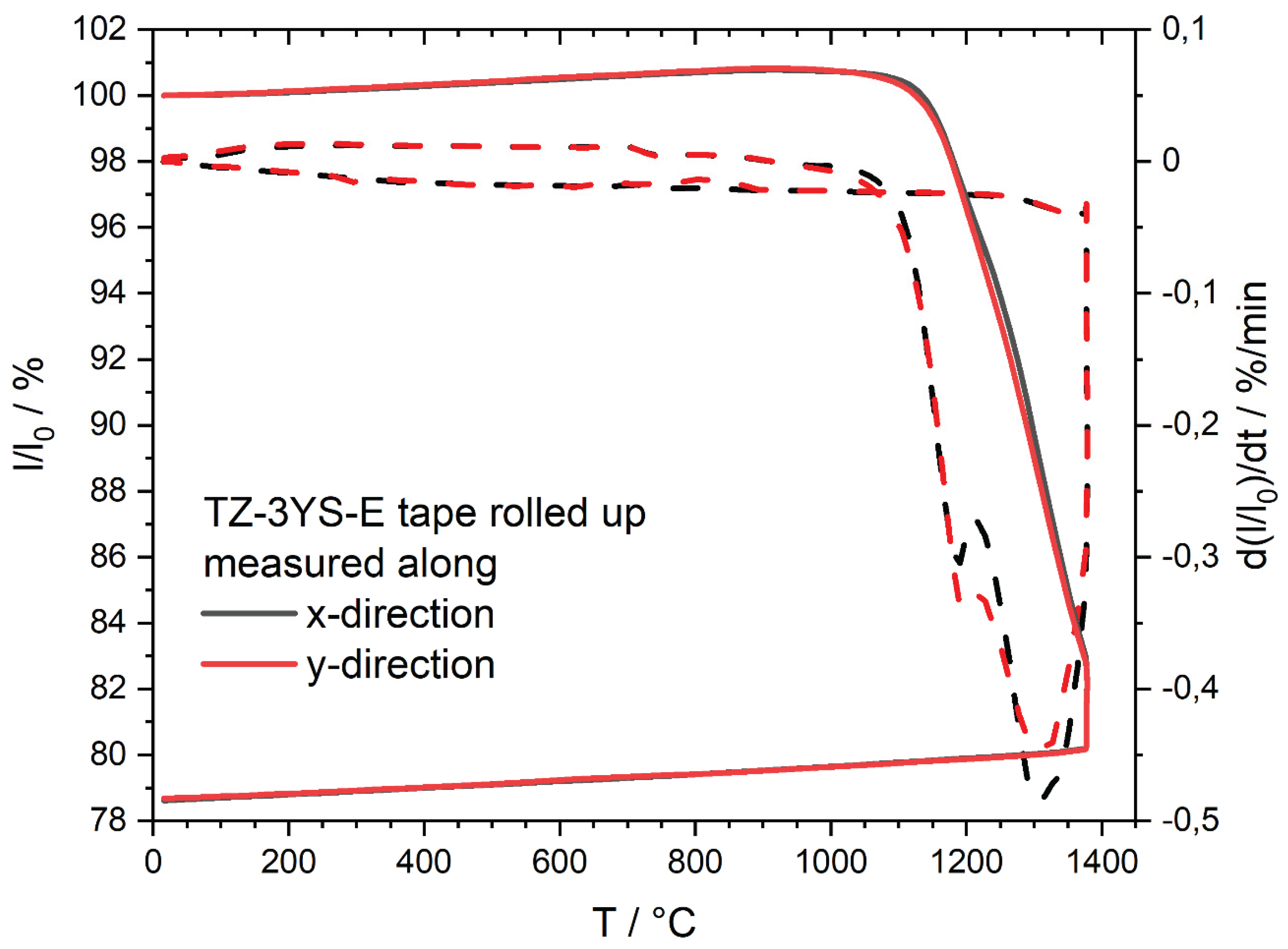

Push-rod dilatometer measurements of rolled up TZ-3YS-E tapes are shown in

Figure 18. Overall, the two curves are similar. The shrinkage is 21.4% and 21.3% in the x- and y-directions of the tape, respectively. Since the samples were previously debinded, there is no effect other than thermal expansion prior to sintering.

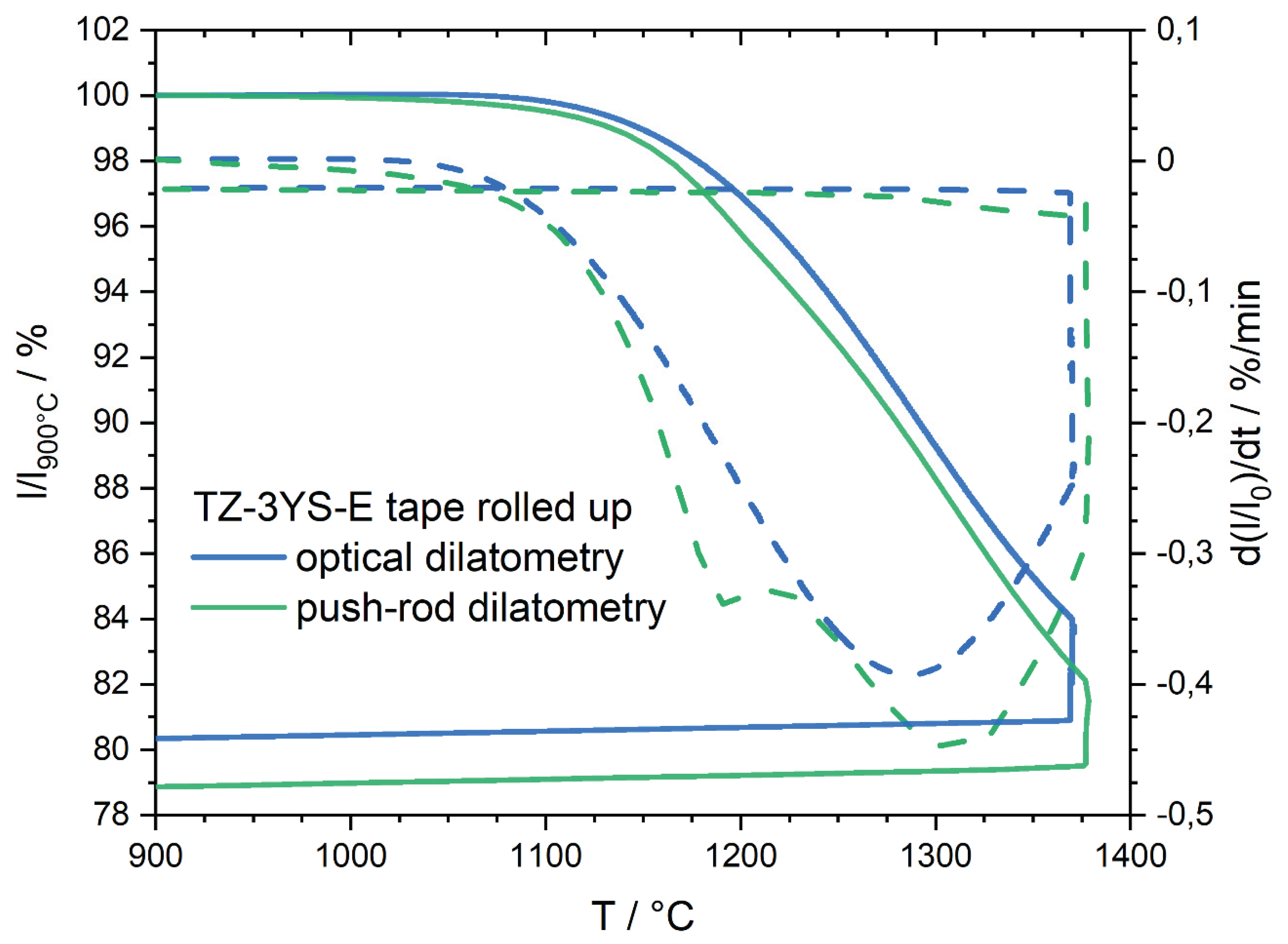

Figure 19 compares the data normalized at 900 °C in the y-direction of rolled TZ-3YS-E tapes measured by optical dilatometry and push-rod dilatometry. The data used are the same as in

Figure 15 and

Figure 17. Slight differences can be seen at the beginning of shrinkage and during the dwell time. The two curves differ slightly in sintering rate from the optical dilatometer data. As with the steel tapes, an additional peak occurs at about 1190 °C and the peak of the relative length change rate is shifted to higher temperatures and higher densification rates. This can be explained in a similar way to the steel tapes. The contact pressure results in a higher total shrinkage up to 1.3%.

Figure C2,

Appendix C compares the two curves when the data are not normalized to 900 °C.

From all the measurements made with the TZ-3YS-E tapes under different conditions, there is no shrinkage anisotropy recognizable between the x- and y-directions of the TZ-3YS-E tape. The difference in total shrinkage between the x- and y-directions is less than 0.4%.

3.3. Comparison of the Results for 17-4PH and TZ-3YS-E

Table 3 summarizes the results for linear shrinkage caused by densification and compares the measured values of the optical or push-rod dilatometer and the caliper, for the materials and the measurement directions of the tape.

In optical dilatometry lying 17-4PH tapes show less shrinkage than rolled tapes, with the difference being less than 2% for both tape directions. Lying TZ-3YS-E tapes in optical dilatometry show higher shrinkage than the rolled tapes, with a difference in shrinkage of less than 1%. This difference is probably caused due to experimental reasons and is not completely understood.

Push-rod dilatometry data for rolled tapes of both materials show higher shrinkage of about 1.0% to 1.3% compared to optical dilatometry. This is most likely due to the contact pressure of the push- rod.

The shrinkage in x-direction of the warped 17-4PH steel tape was corrected from 36.7% (with warpage) to 13.3%. This value is close to the value of 13.9% for the y-direction of the steel tape. In addition, the calculated curve follows the curve for the x- and y-direction of a rolled up tape measured in the optical dilatometer (whose warpage was suppressed).

The optical dilatometry results for rolled up 17-4PH tapes exhibits a shrinkage of 15.2% for both measured directions of the tape. The shrinkage measured with the push-rod dilatometer is also the same in both directions at 16.4%. This reveal, that there is no anisotropy in shrinkage. However, the contact pressure of the push-rod dilatometer influences the densification.

The optical dilatometry results show only 0.2% and 0.4% difference in shrinkage between the x- and y- directions for the lying and rolled TZ-3YS-E ceramic tapes respectively, which can be considered equal within the measurement uncertainty. The shrinkage measured with the push-rod dilatometer is similar in both directions, but also higher than with optical dilatometry, as observed with the steel tapes.

The following should be noted about the temperatures measured in this work. In addition to the measurement uncertainty of u(T) < 5 K, there is an error in the determination of the characteristic temperatures caused by the smoothing of the raw data. The determination of the sintering start temperature in optical dilatometry is particularly affected by this. Since the transition region between thermal expansion and the start of sintering is usually given by a flat curve, the smoothing process has a strong influence on the maximum value of the relative length and thus on the temperature position of the start of sintering to be determined. Depending on the data range selected for smoothing, the value for the sintering start temperature fluctuates by up to 60 K. The values given for the start of sintering are given with their largest deviation. Due to the resolution of the optical dilatometer, the noisy raw signal and the effects of data smoothing, the determination of the sintering start temperature is only useful for orientation. The double tangent extrapolation method (as described in DIN 51007-1:2024-08) is used for determining the onset of accelerated sintering. With push-rod dilatometry, the determination of the temperature position of the additional peak is less affected by the smoothing of the data, and for the characteristic temperatures, the differences due to smoothing are less than 2 K. The temperature values obtained have all been rounded to the nearest ten.

Table 4 summarizes the characteristic temperatures for the sintering process of the steel and ceramic tapes (onset: accelerated sintering, peak of the rate of change in relative length: maximum sintering rate).

Appendix D contains an example for determining the characteristic temperatures and the total shrinkage.

For 17-4PH, the characteristic temperatures are generally lowest in optical dilatometry for the lying tape, are higher in optical dilatometry for the rolled tape, and are even higher in the push-rod dilatometer for the rolled tape. Thermal expansion dominates up to about 950 °C. A transition to shrinkage initiation cannot be clearly determined due to measurement uncertainties.

The characteristic temperatures of TZ-3YS-E tapes measured in the optical dilatometer and rolled up tapes measured in the push-rod dilatometer are similar for both directions of the tape. The temperatures of the beginning of sintering and the start of accelerated sintering of the rolled up tapes determined by optical dilatometry are higher, while the temperature of the maximum relative length change rate is again comparable to the other prepared and measured ceramic tapes.