1. Introduction

The purpose of root canal filling is to prevent bacterial invasion into the aseptic root canal, which is achieved by root canal cleaning and disinfection (i.e., to prevent reinfection) and to entomb trace amounts of remaining bacteria in the root canal, including the dentinal tubules [

1,

2,

3]. Coronal and apical leakage are the main causes of periapical lesions after root canal filling [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Root canal sealers improve sealing between the root canal wall and root canal filling materials and among filling materials themselves. Therefore, these sealers play an important role in maintaining an aseptic root canal and are considered essential materials for root canal filling [

10,

11,

12]. Dye penetration and bacterial leakage tests have been mainly used to evaluate the sealing ability of root canal sealers [

13,

14,

15]. The dye penetration test is relatively simple, but it does not use bacteria and cannot always provide an accurate assessment of bacterial invasion. In recent years, the fluid transport test has become widely used, allowing for quantitative evaluation, and is considered to be more accurate than the dye penetration test [

16,

17,

18]. However, the equipment for the fluid transport test is complicated, with strict control of the conditions required, and similar to the dye penetration test, it does not actually use bacteria. The bacterial leakage test model currently used also has its weaknesses. Even greater care is required to prevent contamination in the bacterial leakage test, and the steps are even more complicated than those of the dye penetration test and the fluid transport test. Therefore, evaluation of the sealing ability of each root canal sealer is affected by the test conditions and varies depending on each test [

19,

20]. The bacterial leakage test is often performed using the entire tooth root. This method can simulate an environment closer to that of clinical practice. However, differences between each evaluation are suggested to be due to anatomical variations, such as side branches and apical bifurcations, the experimental environment (e.g., variations in the prepared root canal shape and equipment attached to specimens), and the complexity of aseptic procedures including sterilization.

Currently, there is a wide variety of root canal sealer products in use. A zinc oxide-eugenol sealer, which was developed in the 1930s, has been widely used worldwide with some improvements since its invention [

20,

21]. However, several types of resin-based sealers have become more popular in recent years, especially in Europe and the United States. Eleazer

et al. [

22] reported that the most commonly used sealers by general dentists registered with the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network were zinc oxide-eugenol-based (43%), resin-based (40%), and calcium hydroxide-based (26%) sealers. Resin sealers are broadly divided into epoxy resin and methacrylate resin types. Among the epoxy resin sealers, AH Plus

® (Dentsply Sirona Inc., Charlotte, NC, USA) is often used as the gold standard comparison when evaluating physical properties of other sealers, such as methacrylate resin sealers [

16,

20]. When methacrylate resin sealers come into contact with the root canal wall, a resin tag and resin-impregnated layer are formed at the interface, resulting in good adhesion [

23,

24,

25]. MetaSEAL

®/Hybrid Root Seal

® (Sun Medical Company, Ltd., Shiga, Japan), which is methacrylate resin-based root canal sealer, is a dual-cure self-adhesive resin sealer containing 4-META. The sealing ability of this sealer when used in combination with gutta-percha or Resilon was evaluated in a fluid transport test, and no significant difference compared with AH Plus was found [

16]. However, similar studies have also reported that the sealing ability of AH Plus is significantly higher than that of MetaSEAL (p < 0.001 for both studies) [

17,

18]. Previously, MetaSEAL was too hard to remove during retreatment. Therefore, MetaSEAL Soft was developed for easier removal during retreatment. Furthermore, MetaSEAL Soft Paste was developed as a paste instead of a powder–liquid product to prevent changes in physical properties due to mixing. A previous study by Ito

et al. [

26] reported that MetaSEAL Soft Paste had better sealing properties than other sealers, including AH Plus Jet, in dye penetration tests. However, the bacterial leakage properties of these sealers have not been compared using bacterial leakage tests.

Enterococcus faecalis is a gram-positive, facultative anaerobic coccus frequently detected in infected root canals with asymptomatic persistent periapical lesions and in infected root canals that require retreatment [

27,

28,

29]. This bacterium is believed to be difficult to remove or disinfect through standard root canal treatment because: 1) it can penetrate deep into the dentinal tubules; 2) it is resistant to alkalinity; 3) it can survive in nutrient-poor, starved environments; and 4) it has the ability to form biofilms, making various antibacterial agents less effective against it [

28,

29].

This study aimed to establish a novel bacterial leakage test model using E. faecalis. We also aimed to compare the ability of various commonly used sealers, including zinc oxide eugenol-based, epoxy resin-based, calcium hydroxide-based, and methacrylate resin-based sealers, to prevent bacterial leakage.

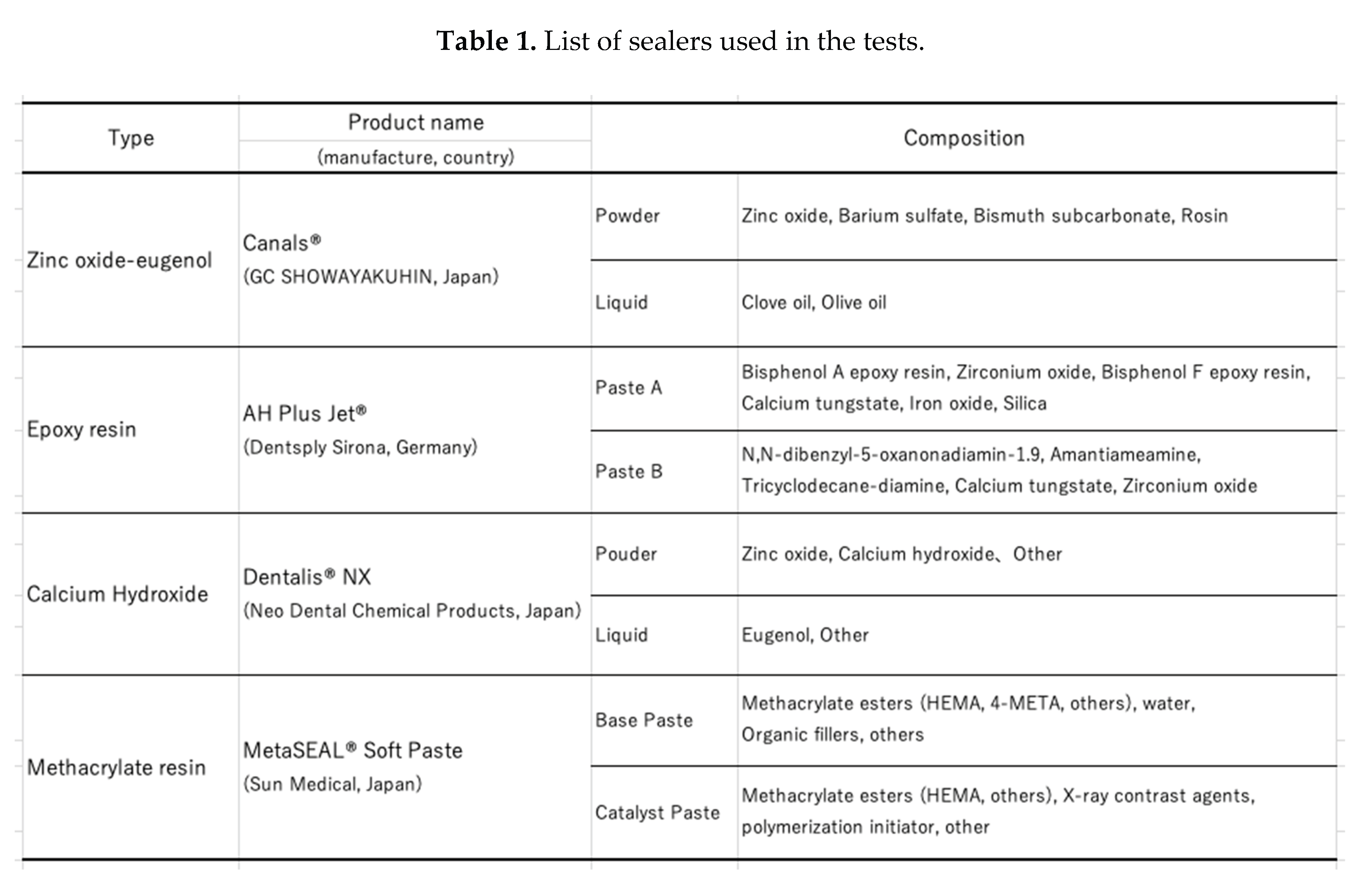

2. Materials and Methods

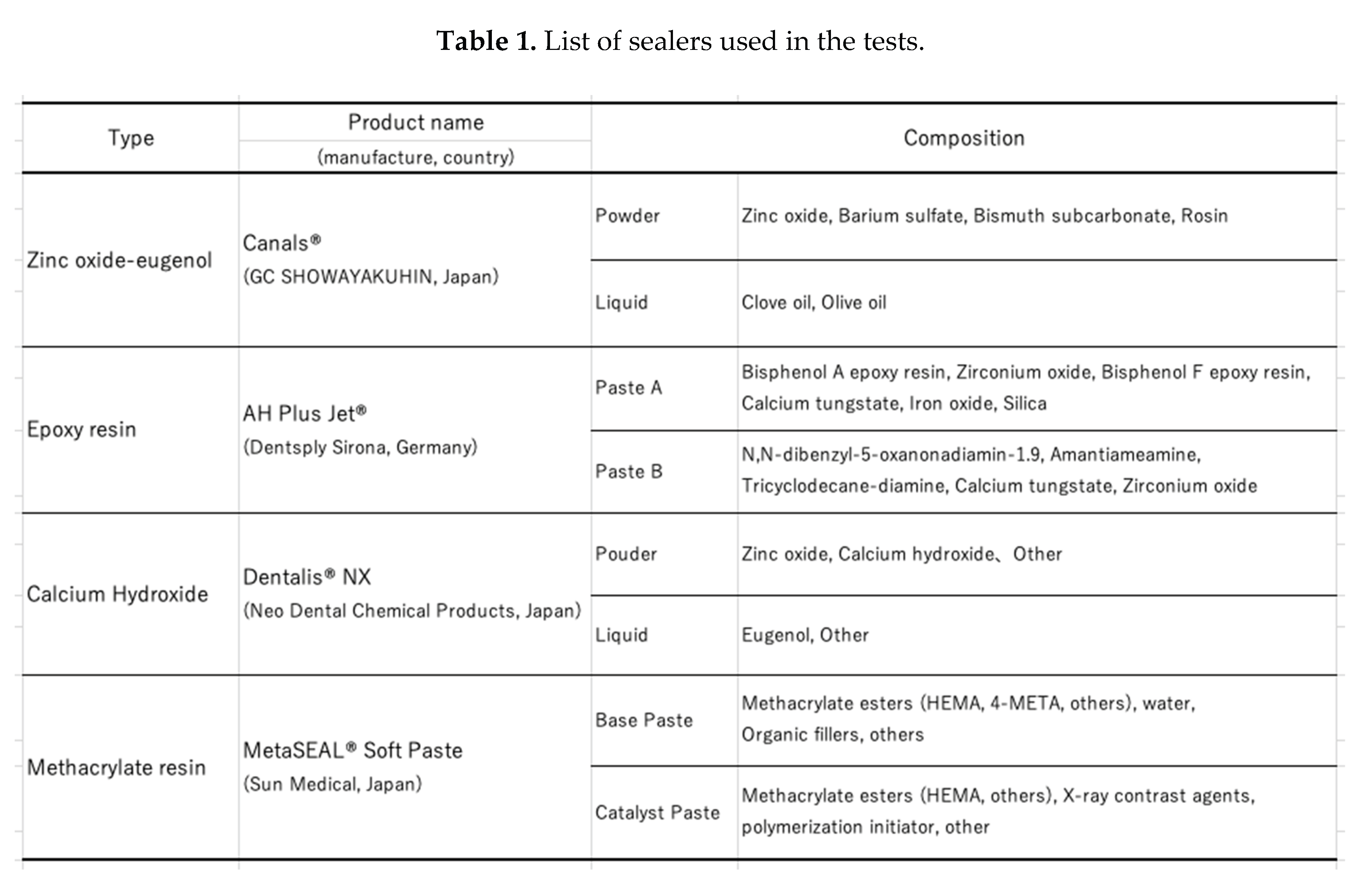

We performed a series of experiments. In these experiments, the equipment that came into direct contact with the specimens was sterile and disposable or sterilized by autoclave or gas sterilization using ethylene oxide gas. The sealers evaluated in this study are shown in Table 1.

2.1. Bacterial Leakage Test

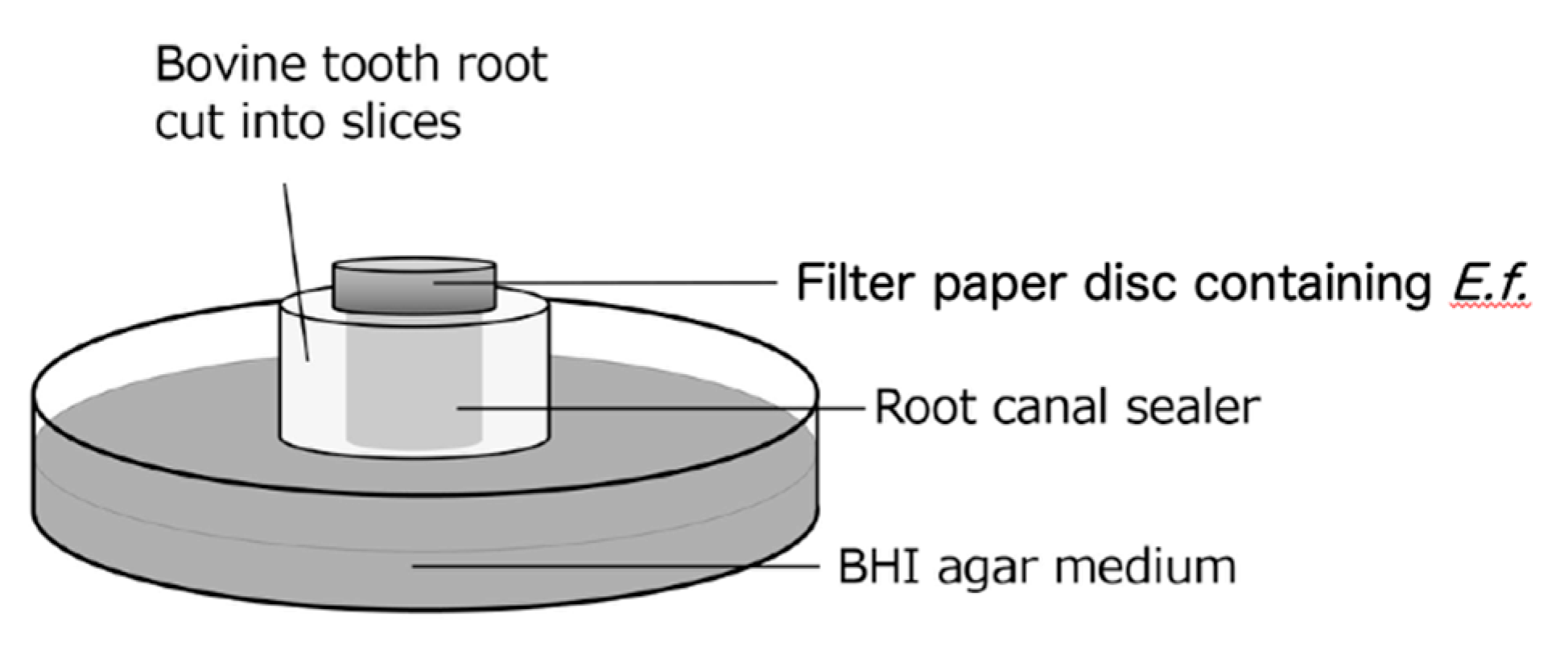

A schematic diagram of the bacterial leakage test model used in this study is shown in

Figure 1. Thirty-six specimens were prepared, 12 of which were used for each test, and each test was carried out 3 times. Three of each of the four sealer types were randomly assigned to each test. The root of a bovine incisor was cut horizontally in the center of the root to a thickness of 3 mm, and the inner diameter was prepared to a diameter of 3 mm using a diamond point (Horiko

® Sinter diamond point SHM111031; Hopf, Ringleb & Co. GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Ultrasonic cleaning was performed for 1 minute each using a 3%–6% sodium hypochlorite solution (DENTAL ANTIFORMIN; Nippon Dental Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., Yamaguchi, Japan), a 3% EDTA solution (Smearclean; Nippon Dental Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd.), and sterile saline solution (Otsuka Saline Injection; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory, Tokushima, Japan). Thereafter, the specimens were sterilized in an autoclave (121°C, 15 minutes) and then immersed in sterile physiological saline for 24 hours. Thereafter, excess moisture was removed from the surface of the specimen with sterile KimWipes

® (Kimberly-Clark Corp., Irving, TX, USA). Each sealer was mixed in the proportions specified by the manufacturer, and then it was inserted into the prepared root canal using a syringe (EndNozzle; Sun Medical Co., Ltd., Shiga, Japan). The specimens were stored at 37°C and 100% humidity. Eight hours after filling, the excess sealer was cut off with a surgical blade (FEATHER

® No. 11; Feather Safety Razor Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) to flatten the sealer surface of the specimen. The sealer-filled specimens were hardened again under the same conditions for up to 24 hours after filling, and they were placed on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar medium (Difco™ Brain Heart Infusion Agar; Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). A filter paper disc (4 mm in diameter, thickness of 1.5 mm, PAPER DISC ADVANTEC

®; Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) containing 20 µl of

E. faecalis (ATCC19433) bacterial suspension (1.0 x 10

7 CFU/ml) was placed on the sealer (3 mm in diameter) on top of the specimen (

Figure 1). The presence or absence of colony formation around the specimen was checked every 24 hours, and the filter paper was replaced every 48 hours.

2.2. Antibacterial Test

2.2.1. Agar Diffusion Test

Thirty-six cylindrical polypropylene molds (diameter: 7 mm, height: 3 mm) were prepared to be filled with the sealers, 12 of which were used in each test, and the test was carried out three times. Three polypropylene molds were used for each of the four types of sealers in each test. Each sealer was injected into the polypropylene mold using the syringe, and it was stored at 37°C and 100% humidity. In the bacterial leakage test, the excess sealer was cut off and removed, and the specimen was allowed to harden for 24 hours under the same conditions. The turbidity of the E. faecalis solution (1.0 x 107 CFU/ml, 100 µl) was adjusted using a spectrophotometer and applied to the surface of the BHI agar medium, after which the specimens were left to stand. After culturing for 24 hours under the same conditions aerobically, the diameter of the inhibition zone formed around the sealer was measured at three random locations, and the average of the three measurements was taken.

2.2.2. Direct Contact Test

A fixed amount (80 µl) of each sealer was injected into a 96-well microplate using a syringe and allowed to harden for 24 hours under 37°C and 100% humidity. The prepared E. faecalis bacterial solution (1.0 x 107 CFU/ml, 200 µl) was poured into each well and cultured aerobically for 24 hours, after which the bacterial solution was collected. Serial dilutions were made and plated on BHI agar medium. After 24 hours of incubation, the colonies were counted, and the number of viable bacteria was calculated. A positive control group containing only the bacterial solution without any sealer filling was added. Three wells were used for each sealer and control group per test, and the test was carried out three times.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

SPSS software (version 26; IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the data. The Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to examine whether there were significant differences in the bacterial leakage test and the antibacterial test. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Leakage Test

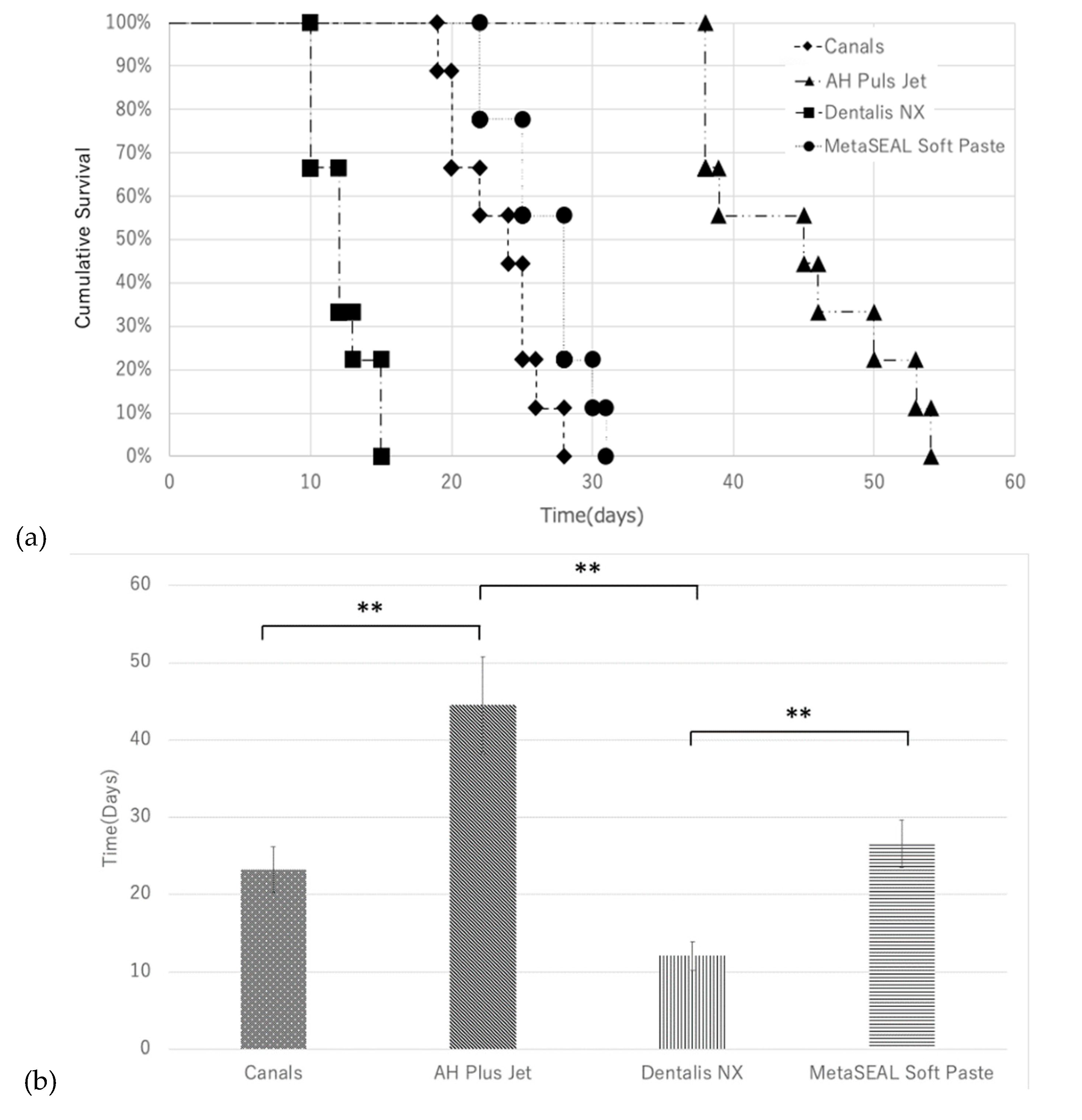

As shown in Kaplan–Meier survival curves (

Figure 2a), colony formation was observed in 10 to 15 days with Dentalis NX. Additionally, colony formation was observed in all specimens of Canals and MetaSEAL Soft Paste at approximately 30 days. However, colony formation was not observed until 54 days in all specimens of AH Plus Jet. The mean number of days required for colony formation in each sealer is shown in

Figure 2b. The mean duration required for colony formation was significantly longer for AH Plus Jet than for Canals and Dentalis NX (p < 0.01), and longer for MetaSeal Soft Paste than for Dentalis NX (p < 0.01) (

Figure 2b). No significant difference in the mean duration required for colony formation was observed between MetaSEAL Soft Paste and AH Plus Jet or between MetaSEAL Soft Paste and Canals, but AH Plus Jet tended to take the longest time to observe colony formation (

Figure 2b).

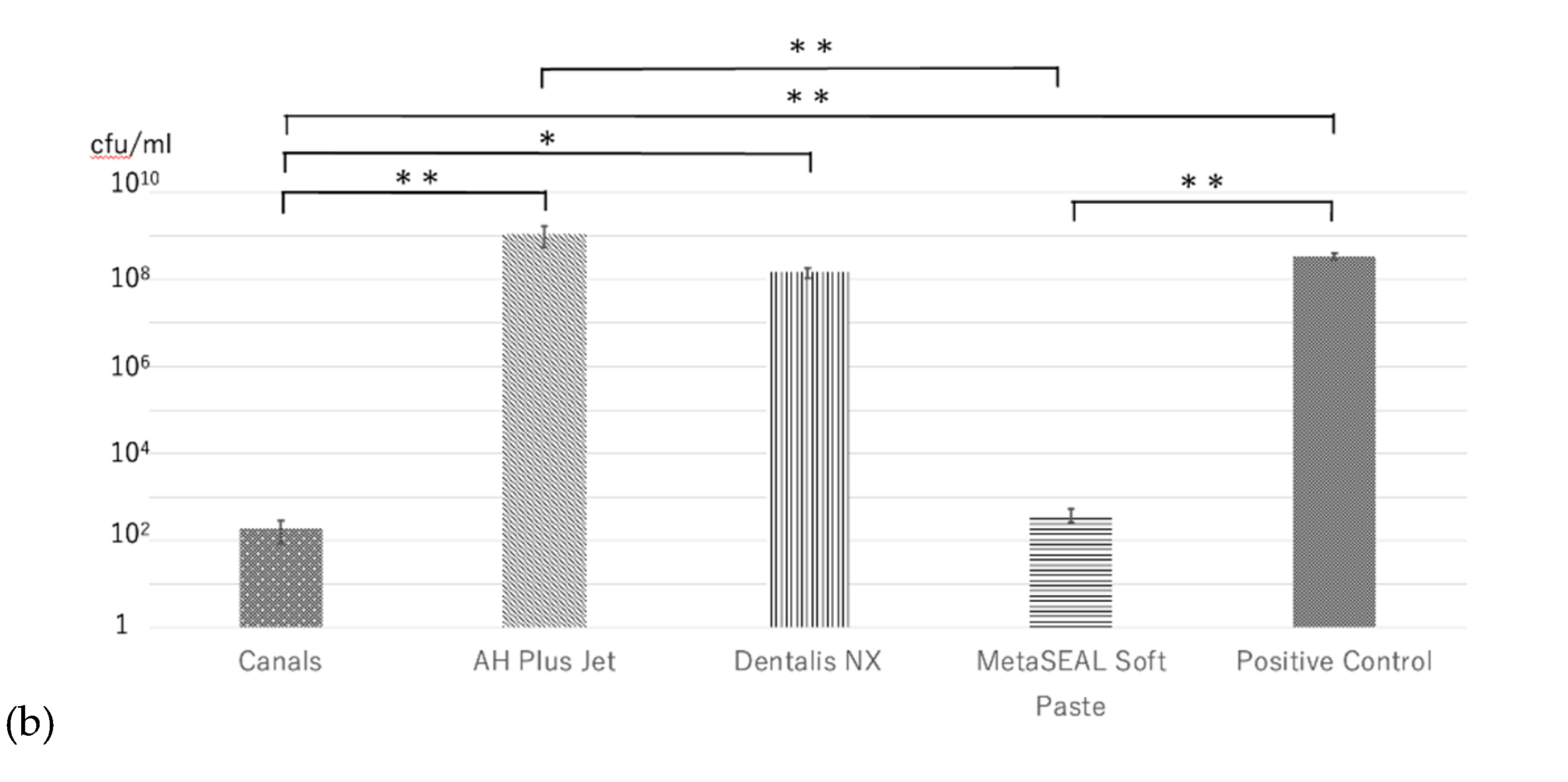

3.2. Antibacterial Test

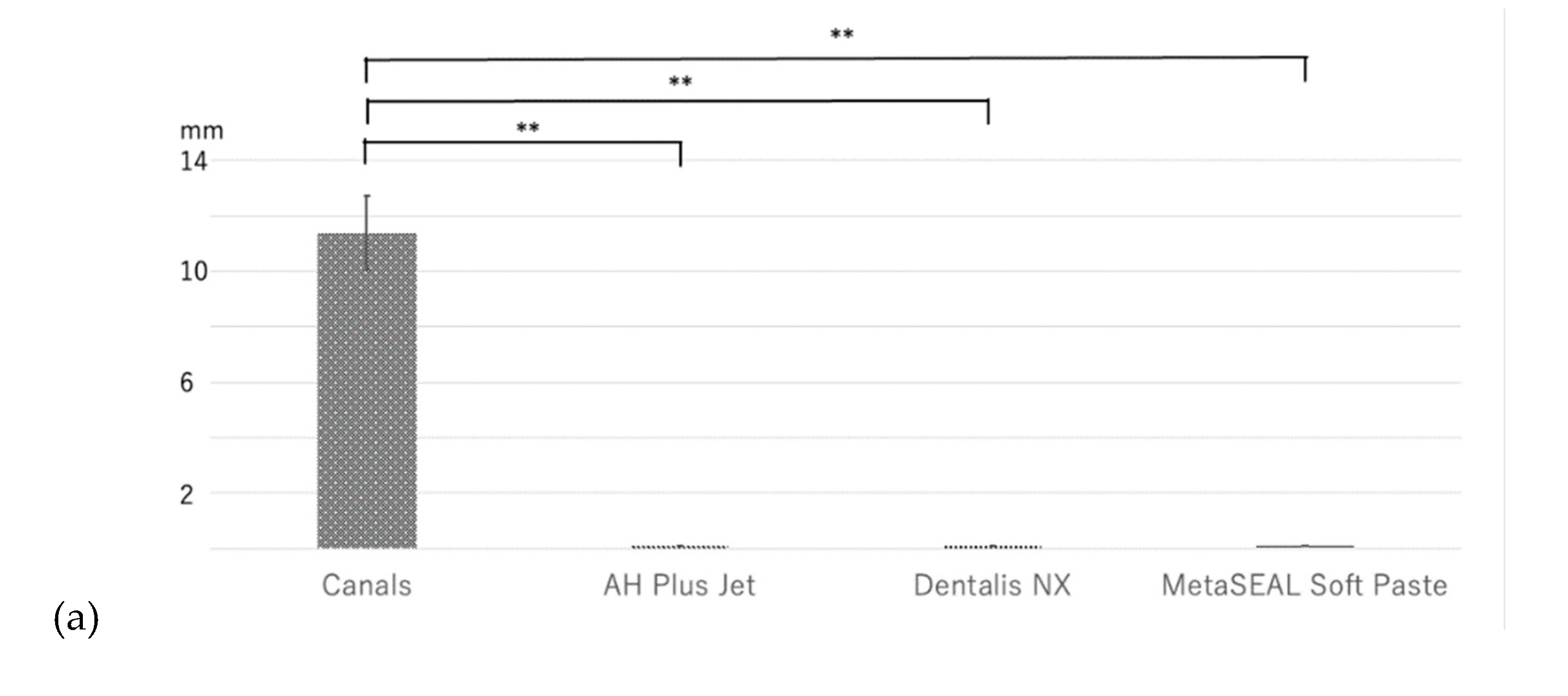

In the agar diffusion test (ADT), an inhibition zone was observed with Canals, but this was not observed with AH Plus Jet, Dentalis NX, or MetaSEAL Soft Paste (

Figure 3a). In the direct contact test (DCT), significantly fewer bacteria were detected in MetaSEAL Soft Paste and Canals than in positive controls (p < 0.01) (

Figure 3b). However, no significant difference in the number of bacteria was observed between MetaSEAL Soft Paste and Canals (

Figure 3b). There was also no significant difference in the number of bacteria between AH Plus Jet or Dentalis NX and positive controls (

Figure 3b). Additionally, no significant difference in the number of bacteria was observed between these two sealers (

Figure 3b). MetaSEAL Soft Paste and Canals showed significantly fewer bacteria than AH Plus Jet (p < 0.01) (

Figure 3b).

4. Discussion

This study showed that in bacterial leakage tests, AH Plus Jet took a significantly longer time for colony formation than Canals and Dentalis NX. Furthermore, although no significant difference in the time for colony formation was observed between AH Plus Jet and MetaSEAL Soft Paste, a strong tendency was observed. In the DCT, significantly fewer bacteria were detected in MetaSEAL Soft Paste and Canals than in AH Plus Jet or positive controls.

AH Plus Jet took a significantly longer time for colony formation than Canals and Dentalis NX in bacterial leakage tests in this study. Many studies have suggested that AH Plus has a higher sealing ability than zinc oxide-eugenol sealers [

15,

30,

31,

32]. Previous studies on the comparison between AH Plus and calcium hydroxide-based sealers have been conflicting. In two studies that evaluated AH Plus and the hydroxide-based sealer Apexit, using similar bacterial leakage tests, one reported that AH Plus was superior in its sealing ability [

14] and the other was reported as inferior [

33]. Similarly, the comparison between AH Plus and Sealapex using the bacterial leakage test has shown conflicting results [

30,

32]. The bacterial leakage test model used in this study can provide a simple and standardized method to evaluate the ability of sealers to prevent bacterial leakage in a more reliable and accurate manner than other tests.

In this study, AH Plus Jet showed the highest ability to prevent bacterial leakage compared with the other sealers. However, this result may only represent the sealer’s antimicrobial properties and may not indicate its sealing properties. Therefore, we also evaluated the antibacterial properties of each sealer. We found that Canals, a zinc oxide-eugenol-based sealer, showed antibacterial activity in the ADT and the DCT. Eugenol contained in zinc oxide eugenol-based sealers exerts antibacterial effects by inhibiting bacterial cell membrane function, suppressing the production of toxins and enzymes and inhibiting biofilm formation [

34]. Additionally, eugenol exhibits antibacterial properties against

E. faecalis [

35,

36]. Therefore, the antibacterial properties of Canals in this study may be related to free eugenol. Furthermore, eugenol is widely known to possess cytotoxic and tissue-toxic properties and to act as an inflammatory agent [

20,

37]. MetaSEAL Soft Paste showed no antibacterial effect in the ADT, whereas it showed an antibacterial effect in the DCT. This finding may have been due to the excessive number of bacteria used in the ADT, or alternatively, the antibacterial components in MetaSEAL Soft Paste may have had difficulty diffusing into the agar medium. On the other hand, no antibacterial effect was observed in AH Plus Jet in the ADT and the DCT.

Although AH Plus Jet did not show antibacterial properties, it had the longest duration for confirmation of colony formation in the bacterial leakage test, which suggested that it had the highest sealing ability. Furthermore, MetaSEAL Soft Paste, which has been attracting attention in recent years, had higher antibacterial properties than AH Plus Jet, but showed a tendency for earlier colony formation in the bacterial leakage test, which suggested that its sealing ability was inferior to that of AH Plus Jet. This result is different from a report [

26] in which MetaSEAL Soft Paste showed a better sealing ability than AH Plus Jet and Canals in a dye penetration test. Therefore, dye penetration testing methods may not be able to properly evaluate the sealing ability of root canal sealers. The bacterial leakage test performed in this study may not fully reflect actual clinical conditions because the entire root or gutta-percha was not used. However, we believe that this model is reliable for evaluating the ability of the sealer to prevent bacterial leakage.

Nevertheless, long-term sealing depends on many properties, such as adhesion, antibacterial properties, dimensional stability, solubility, and flow. There have been few reports of sealing experiments using MetaSEAL Soft Paste, and further accumulation and examination of experimental data are necessary. Additionally, MTA/bioceramic sealers, which have been attracting attention in recent years, have been reported to have better sealing properties than AH Plus [

33,

38], but also have inferior sealing properties [

4,

30,

31]. Therefore, we plan to conduct a comparative study using this test model in future studies.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests that the novel bacterial leakage test model is effective for accurately evaluating the ability of sealers to prevent bacterial leakage, and further suggests that the sealing ability of MetaSEAL Soft Paste may not be superior to that of AH Plus Jet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.; data curation, K.I., N.H., and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.I. and N.H.; writing—review and editing, T.M.; funding acquisition, T.M., N.H., and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the KAKEN (23K09191 to N.H., 20K18549 to M.F., and 19K10156 and 22K09986 to T.M.). This research was also funded by Sun Medical Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

|

• BHI |

brain heart infusion |

| • ADT |

agar diffusion test |

| • DCT |

direct contact test |

| • MTA |

mineral trioxide aggregate |

References

- Delivanis, P.D.; Mattison, G.D.; Mendel, R.W. The survivability of F43 strain of Streptococcus sanguis in root canals filled with gutta-percha and Procosol cement. J Endod 1983, 9, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezhnev, A.; Neelakantan, P.; Tanaka, R.; Brezhnev, S.; Fokas, G.; Matinlinna, J.P. Antibacterial Additives in Epoxy Resin-Based Root Canal Sealers: A Focused Review. Dent J (Basel) 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirthiga, M.; Thomas, G.; Jose, S.; Adarsh, V.J.; Nair, S. Antimicrobial efficacy of calcium silicate-based bioceramic sealers against Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus - An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent Endod 2024, 27, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, K.; Daniel, J.; Ahn, C.; Primus, C.; Komabayashi, T. Coronal and apical leakage among five endodontic sealers. J Oral Sci 2022, 64, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, J.E.; Gutmann, J.L.; Guo, I.Y. Apical and coronal seal of roots obturated with a dentine bonding agent and resin. Int Endod J 1996, 29, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimura, H.; Yoshioka, T.; Suda, H. Sealing ability of new adhesive root canal filling materials measured by new dye penetration method. Dent Mater J 2007, 26, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.M.; Abbott, P.V. An in vitro study of apical and coronal microleakage of laterally condensed gutta percha with Ketac-Endo and AH-26. Aust Dent J 1998, 43, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, S.; Swanson, K.; Chiles, S.A. An evaluation of coronal microleakage in endodontically treated teeth. Part II. Sealer types. J Endod 1987, 13, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, H.A.; Trope, M. Periapical status of endodontically treated teeth in relation to the technical quality of the root filling and the coronal restoration. Int Endod J 1995, 28, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, E.J.; Dumsha, T.C. Leakage evaluation in vitro of the root canal sealer cement Sealapex. Int Endod J 1985, 18, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.K.; Van Der Sluis, L.W.; Wesselink, P.R. Fluid transport along gutta-percha backfills with and without sealer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004, 97, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, J.M.; Baco, L. Coronal leakage of sealer-only backfill: an in vitro evaluation. J Endod 2005, 31, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthel, C.R.; Moshonov, J.; Shuping, G.; Orstavik, D. Bacterial leakage versus dye leakage in obturated root canals. Int Endod J 1999, 32, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpawat, S.; Amornchat, C.; Trisuwan, W.R. Bacterial coronal leakage after obturation with three root canal sealers. J Endod 2001, 27, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.F., Jr.; Rocas, I.N.; Valois, C.R. Apical sealing ability of five endodontic sealers. Aust Endod J 2001, 27, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, S.; Ozcan, E.; Derinbay, O.; Eldeniz, A.U. A comparative evaluation of sealing ability of a new, self-etching, dual-curable sealer: hybrid root SEAL (MetaSEAL). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008, 106, e45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onay, E.O.; Orucoglu, H.; Kiremitci, A.; Korkmaz, Y.; Berk, G. Effect of Er,Cr:YSGG laser irradiation on the apical sealing ability of AH Plus/gutta-percha and Hybrid Root Seal/Resilon Combinations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010, 110, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, O.I.; Nayir, Y.; Celik, K.; Yaman, S.D. Apical microleakage of different root canal sealers after use of maleic acid and EDTA as final irrigants. Braz Oral Res 2014, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadkouhi, S.T.; Bakhtiar, H.; Ardestani, S.E. In vitro and ex vivo microbial leakage assessment in endodontics: A literature review. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 2016, 6, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komabayashi, T.; Colmenar, D.; Cvach, N.; Bhat, A.; Primus, C.; Imai, Y. Comprehensive review of current endodontic sealers. Dent Mater J 2020, 39, 703–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Bauza, G.A.; Silva-Sousa, Y.T.; da Cunha, S.A.; Rached-Junior, F.J.; Bonetti-Filho, I.; Sousa-Neto, M.D.; Miranda, C.E. Physicochemical properties of endodontic sealers of different bases. J Appl Oral Sci 2012, 20, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleazer, P.D.; Gilbert, G.H.; Funkhouser, E.; Reams, G.J.; Law, A.S.; Benjamin, P.L. ; National Dental Practice-Based Research Network Collaborative, G. Techniques and materials used by general dentists during endodontic treatment procedures: Findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc. [CrossRef]

- Nakabayashi, N.; Takarada, K. Effect of HEMA on bonding to dentin. Dent Mater 1992, 8, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.S.; Loushine, B.; Mai, S.; Weller, R.N.; Pashley, D.H.; Tay, F.R.; Loushine, R.J. Resistance of a 4-META-containing, methacrylate-based sealer to dislocation in root canals. J Endod 2008, 34, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, S.R.; Tordik, P.A.; Imamura, G.M.; Baginski, T.A.; Goodell, G.G. A confocal laser scanning microscope investigation of the epiphany obturation system. J Endod 2007, 33, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Kado, T.; Furuichi, Y. Evaluation of root canal sealing and removal of resin-based sealers (In Japanese). The Joural of Japan Endodontic Association 2023, 44, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist, G.; Figdor, D.; Persson, S.; Sjögren, U. Microbiologic analysis of teeth with failed endodontic treatment and the outcome of conservative re-treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1998, 85, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, F.; Shakir, M. The Influence of Enterococcus faecalis as a Dental Root Canal Pathogen on Endodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2020, 12, e7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShwaimi, E.; Bogari, D.; Ajaj, R.; Al-Shahrani, S.; Almas, K.; Majeed, A. In Vitro Antimicrobial Effectiveness of Root Canal Sealers against Enterococcus faecalis: A Systematic Review. J Endod 2016, 42, 1588–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.C.; Tanomaru, J.M.; Faria-Junior, N.; Tanomaru-Filho, M. Bacterial leakage in root canals filled with conventional and MTA-based sealers. Int Endod J 2011, 44, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakke Patil, A.; Patil, A.G.; Shaikh, S.; Bhandarkar, S.; Moharir, A.; Sharma, A. Comparative Evaluation of the Sealing Ability of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA)-Based, Resin-Based, and Zinc Oxide Eugenol Root Canal Sealers: An In Vitro Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e52201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Deus, G.; Coutinho-Filho, T.; Reis, C.; Murad, C.; Paciornik, S. Polymicrobial leakage of four root canal sealers at two different thicknesses. J Endod 2006, 32, 998–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeniz, A.U.; Ørstavik, D. A laboratory assessment of coronal bacterial leakage in root canals filled with new and conventional sealers. Int Endod J 2009, 42, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Singh, K.; Verma, P.K.; Khan, A.U. Eugenol-induced suppression of biofilm-forming genes in Streptococcus mutans: An approach to inhibit biofilms. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2014, 2, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaidka, S.; Somani, R.; Singh, D.J.; Sheikh, T.; Chaudhary, N.; Basheer, A. Herbal combat against E. faecalis - An in vitro study. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2017, 7, 178-181. [CrossRef]

- Gowda, J.; Tavarageri, A.; Kulkarni, R.; Anegundi, R.T.; Janardhan, A.; Bhat, M.A. Comparative Assessment of the Antimicrobial Efficacy of Triclosan, Amoxicillin and Eugenol against Enterococcus faecalis. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2021, 14, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, D.R.; Wilcko, J.M.; Pullon, P.A.; Furst, M.L.; Passo, S.A. A comparative tissue toxicity evaluation of the liquid components of gutta-percha root canal sealers. J Endod 1981, 7, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaul, S.; Kumar, A.; Badiyani, B.K.; Sukhtankar, L.; Madhumitha, M.; Kumar, A. Comparison of Sealing Ability of Bioceramic Sealer, AH Plus, and GuttaFlow in Conservatively Prepared Curved Root Canals Obturated with Single-Cone Technique: An In vitro Study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2021, 13, S857–s860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).