1. Introduction

Computed tomography (CT) is an essential diagnostic tool in modern medicine [

1]. However, its increasing use has prompted growing interest in understanding how the low doses of ionizing radiation delivered by these scans affect living cells [

2,

3]. In contrast to high-dose radiation, which is typically associated with cellular mortality, low-dose radiation can trigger more subtle changes, including DNA damage, oxidative stress, and altered gene expression patterns [

4,

5]. While the immediate consequences of high doses are well-known, the long-term biological effects of low-dose exposures are not fully understood [

6,

7]. This is particularly relevant and important for stem cells, the body’s natural repair system that may be sensitive to such subtle environmental changes [

8,

9].

Mesenchymal stem cells derived from human adipose tissue (AD-MSCs) are a key population of adult stem cells essential for tissue repair, regeneration, and immunomodulation [

10]. Their function is largely mediated through their paracrine secretion of a vast array of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, collectively known as the secretome [

11]. The secretory profile is highly dynamic and sensitive to environmental stressors [

12].

We hypothesized that exposure to diagnostic CT-level radiation could cause delayed changes to the AD-MSCs’ secretome. Crucially, these changes might not be immediately apparent but could manifest after the cells have undergone multiple divisions following the exposure. This approach allows us to model the potential long-term functional consequences for cells that survive a radiation insult and continue to proliferate.

Therefore, this study aimed to track how the secretome of AD-MSCs changes over a long-term culturing after exposure to different radiation regimens. We included both a negative control (non-irradiated AD-MSCs) and a positive control (a standard therapeutic dose of 2 Gy) to benchmark the effects of single and multiple CT-level diagnostic doses. By analyzing 41 cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors (secreted factors) at early, middle, and late passages, we sought to identify both the immediate and the long-term effects of radiation on the secretory profile of these proliferating stem cells.

2. Results

2.1. Multivariate Analysis Reveals Passage-Dependent Changes in the Secretome

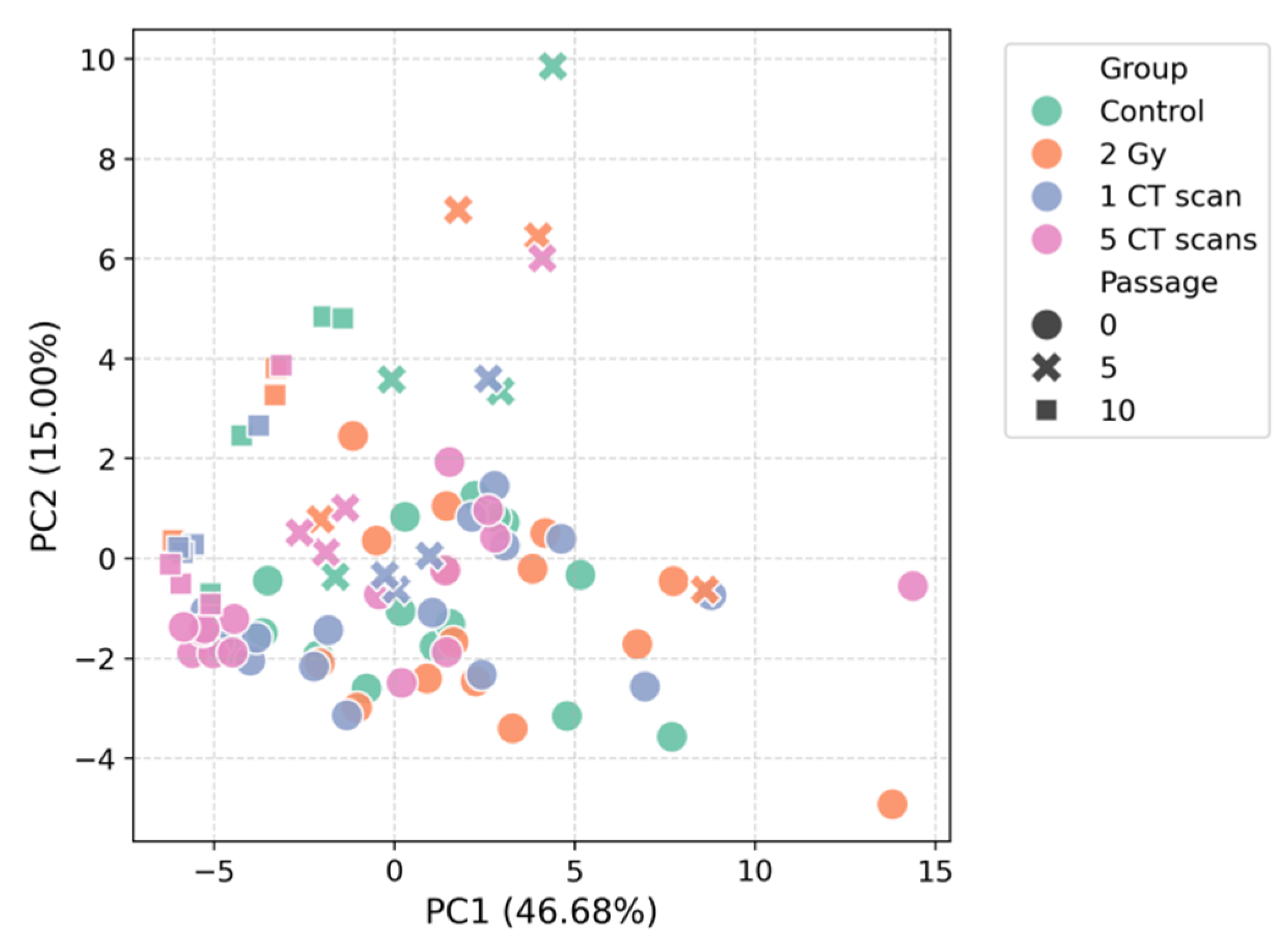

To assess the overall impact of radiation exposure and long-term culturing on the AD-MSCs secretome, we performed unsupervised multivariate analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the z-score normalized data did not reveal clear separation of samples by radiation group at any passage (

Figure 1). The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) accounted for 46.68% and 15.00% of the total variance, respectively, indicating that no single dominant pattern of secretion distinguished the experimental groups.

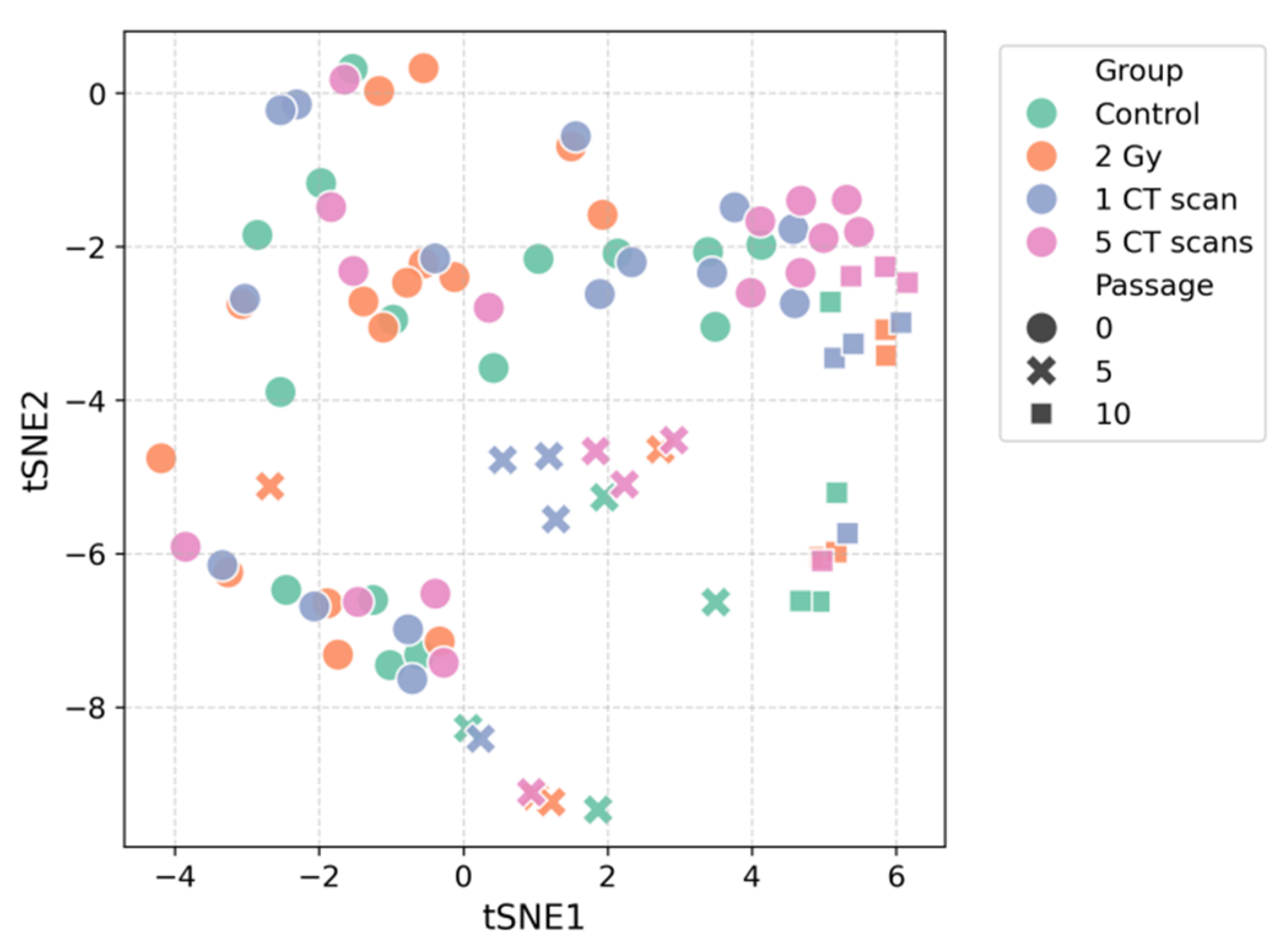

Consistent with the PCA results, visualization via t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) also failed to demonstrate distinct clustering according to radiation treatment (

Figure 2). However, both analytical approaches revealed a notable tendency for samples to group by passage number rather than by radiation exposure. This pattern was particularly evident in the t-SNE projection, where samples from later passages (5 and 10) occupied distinct regions of the dimensionality-reduced space compared to passage 0 samples.

2.2. Cluster Analysis Reveals Shows Minimal Radiation-Induced Secretome Alterations

Initial univariate analysis comparing individual secreted factor levels between experimental groups at passages 0, 5, and 10 did not yield statistically significant differences. Similarly, a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) failed to detect significant multivariate separation between radiation groups when analyzing the full secretome panel at each passage individually.

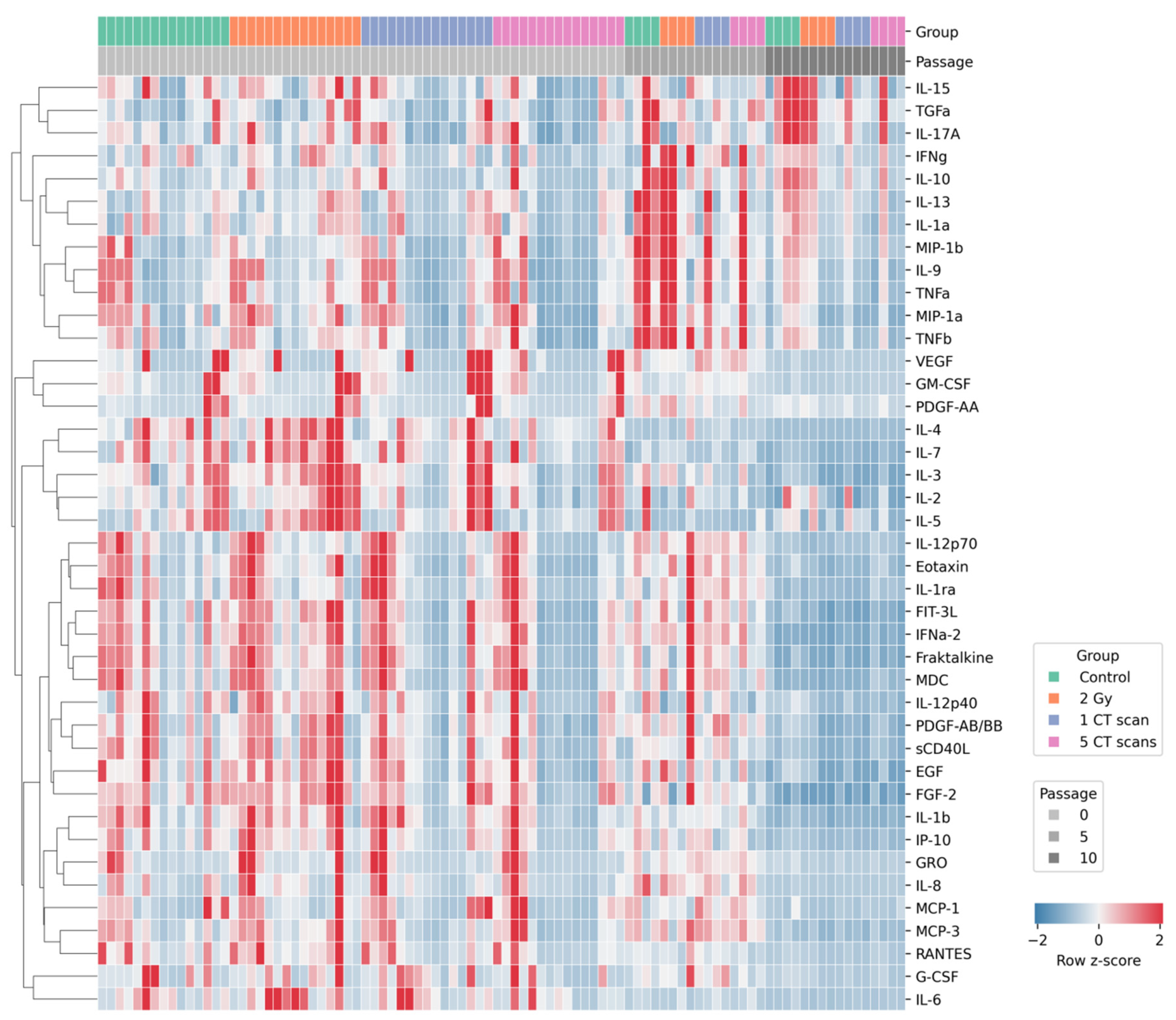

Given the potential for coordinated changes in secreted factors, we employed an unsupervised hierarchical clustering approach to identify latent patterns within the AD-MSCs secretome. Heatmap visualization revealed groups of secreted factors that changed their levels in a coordinated way across different passages and experimental conditions (

Figure 3). To identify these groups systematically, we performed cluster validation to find the optimal number of clusters.

The clustering validation procedure reached statistical significance for the combined dataset (all passages) at t = 2 (

p = 0.04), t = 4 (

p = 0.04), and t = 7 (

p = 0.006). At passage 0, significance was achieved only at t = 7 (

p = 0.016), while no significant clustering was observed at passages 5 and 10. Based on these results and validation with silhouette score and permutation testing (

p = 0.001), we have divided the secreted factors into seven clusters. The biological characteristics of the seven identified clusters are presented in

Table 1.

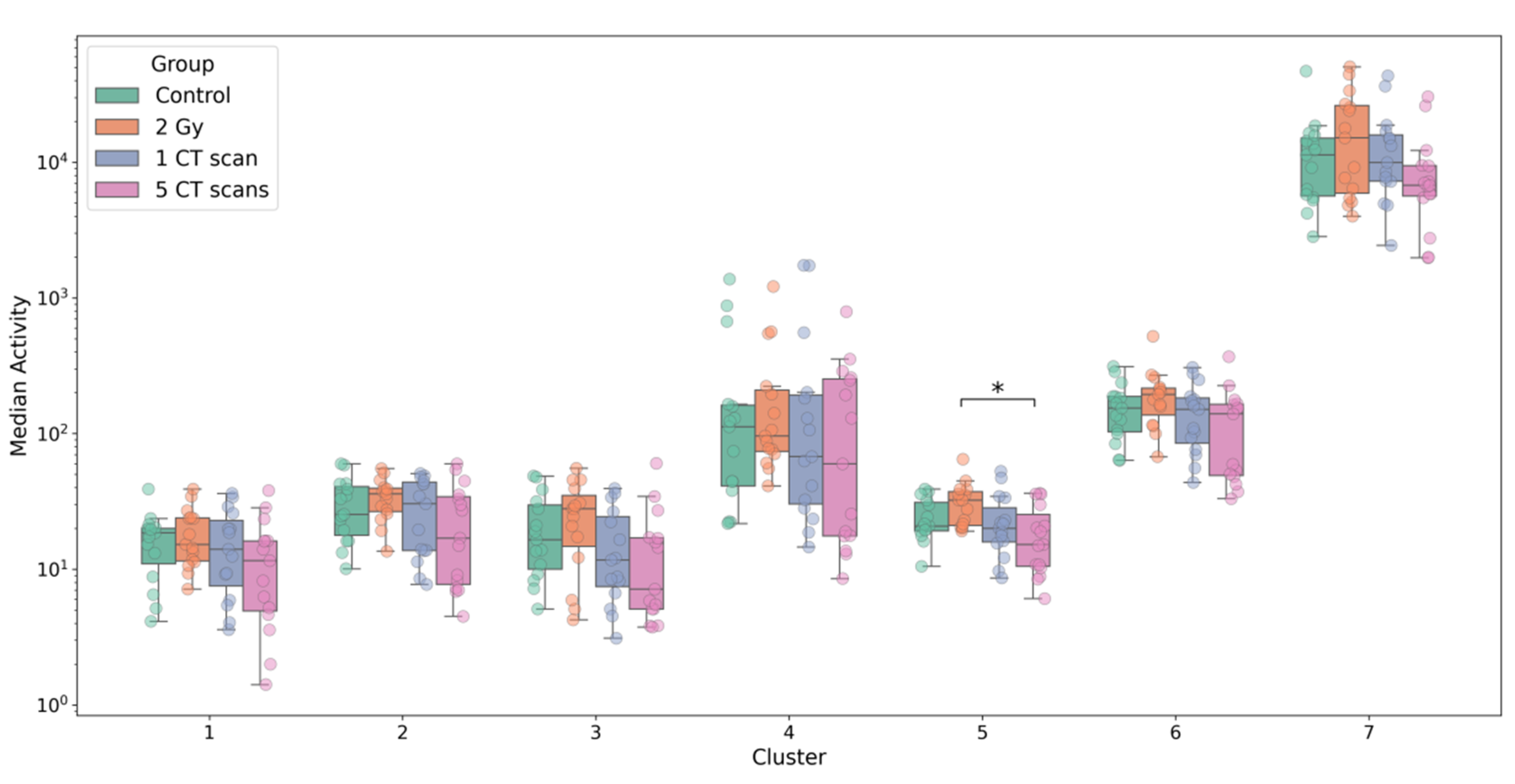

Multivariate analysis using PERMANOVA of the seven cluster activities revealed a statistically significant difference between radiation groups at passage 0 (p < 0.05). Subsequent univariate analysis identified that Cluster 5 (IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-7) showed significantly higher activity in the 2 Gy group compared to the 5 CT scans group (padj = 0.01) (

Figure 4). However, this difference was not sustained at later passages (5 and 10), where no significant intergroup differences were observed in cluster activities (

Figure S1 and

Figure S2).

Taken together, these findings suggest that radiation-induced alterations in the AD-MSCs secretome are minimal and not consistently supported by robust statistical evidence.

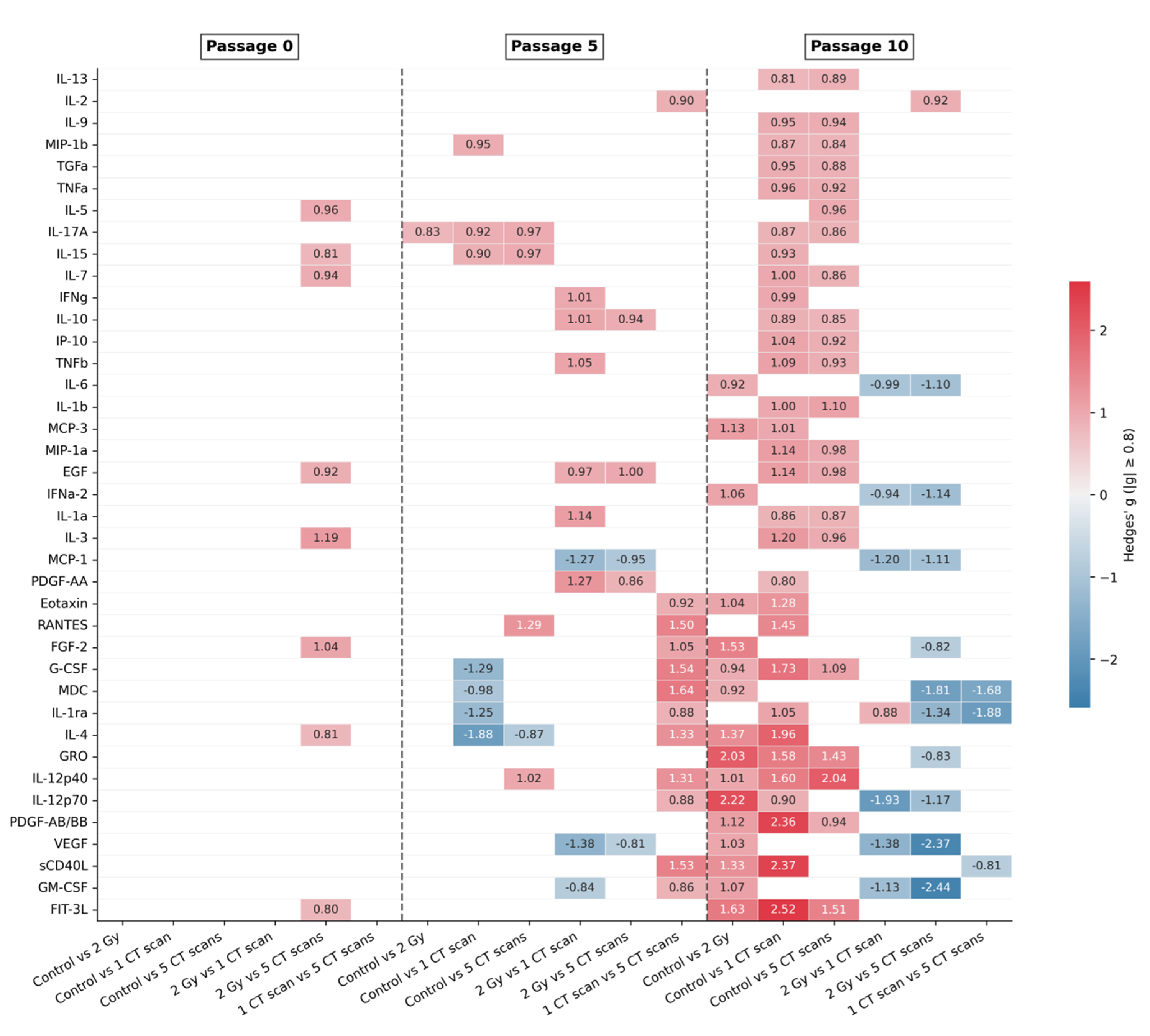

2.3. Effect Size Analysis Uncovers Passage-Dependent Radiation Effects

Due to possible limitations of the power of standard statistical tests, we performed an effect size analysis. It revealed a pronounced passage-dependent escalation in the radiation effect. At passage 0, significant differences were sparse and specific: only 8 secreted factors (IL-3, FGF-2, IL-5, IL-7, EGF, IL-15, IL-4, FIT-3L) exhibited a large effect size (|g| > 0.8), all showing elevated levels in the 2 Gy group compared to the 5 CT scans group (

Figure 5).

In contrast, the secretome landscape was explicitly altered by passage 10. Each secreted factor demonstrated a large effect size when comparing at least one pair of groups. A key finding at passage 10 was that if any irradiated group (2 Gy, 1 CT scan, or 5 CT scans) was compared to the non-irradiated Сontrol group, then the differences were driven by higher levels of secreted factors in the Control group. This indicates a significant reduction in secretory function in all irradiated AD-MSCs after long-term culturing. Interestingly, the most pronounced contrast was observed between the Control group and the 1 CT scan group that received the lowest radiation dose. A more detailed comparison revealed a nuanced hierarchy in secretory suppression. Although the 2 Gy group was less distinct from the Control group, it demonstrated a significantly lower secretion of IL-12p70, VEGF, MCP-1, GM-CSF, IL-6, and IFNa-2 compared to the 1 CT scan group. Furthermore, the differences between the two diagnostic-dose groups (1 CT scan and 5 CT scans) were minimal. Only three factors (IL-1ra, MDC, and sCD40L) were present at higher levels in the 5 CT scans group (

Figure 5).

At passage 5, the secretome changes were ambiguous, showing no clear or consistent pattern across the treatment groups, which suggests this time point may represent a transitional state between the early response and the late established effects (

Figure 5).

Next, we selected the subsets of secreted factors that demonstrate the largest effect size in a particular passage to screen whether such subsets can provide differences between all four experimental groups. At passage 0, PERMANOVA found statistically significant differences between the groups for every subset we tested, from the single most influential factor (

N = 1) up to the all eight secreted factors that demonstrated a large effect size (

N = 8) (

Table 2). Thus, the key factors driving this early separation between groups were IL-3, FGF-2, IL-5, IL-7, EGF, IL-15, IL-4, and FIT-3L.

This signature strongly aligns with the results of the cluster analysis. Half of these eight factors (IL-3, IL-5, IL-7, IL-4) form the Cluster 5 (

Table 1), which we previously identified as being significantly elevated in the 2 Gy group. The addition of the growth factors FGF-2, EGF, IL-15, and FIT-3L to this signature provides a more complete landscape. This convergence of evidence from two independent analytical methods validates that this specific molecular signature, involved in lymphocyte regulation and growth promotion, is a key driver of the early cellular response to different radiation regimens.

In contrast, no significant differences were found at passage 5 for any subset size, suggesting a lack of clear, coordinated changes in the secretome at this middle passage (

Table 2).

The pattern at passage 10 was more complex. Significant differences between groups were only detected when using either small subsets (the top 1 or 2 secreted factors) or much larger ones (the top 7 to 10 secreted factors) (

Table 2). This indicates that by the late passage, the differences could be captured either by a couple of extremely powerful factors or by a broader signature representing a wider functional decline. The most important factors at this stage were FIT-3L, GM-CSF, sCD40L, VEGF, PDGF-AB/BB, IL-12p70, IL-12p40, GRO, IL-4, and IL-1ra.

Notably, the majority of these secreted factors belong to the large and heterogeneous Cluster 6 (

Table 1). The fact that a signature of factors from this diverse cluster is required to detect the differences tells us that the radiation effect is no longer specific. Instead, it reflects a broad, general breakdown of the secretory function in the irradiated cells after long-term culture.

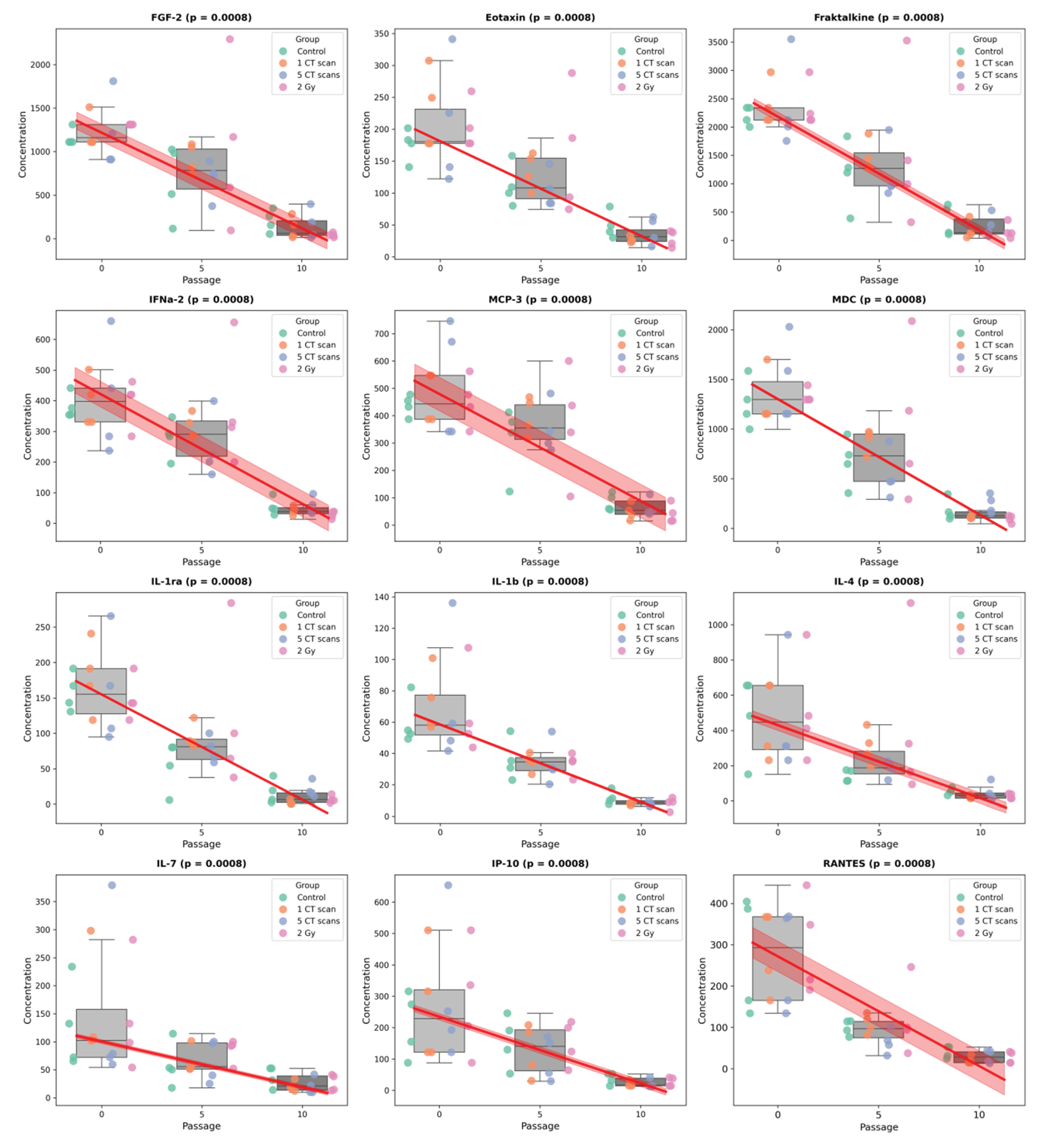

2.4. Temporal Trend Analysis Uncovers Passage-Dependent Secreted Factor Dynamics

Page’s trend test revealed significant decreasing trends in 26 secreted factors across passages, with no factors showing significant increases. The strength of association varied considerably among factors.

Twelve factors demonstrated the strongest passage-dependence (p = 0.0008), including FGF-2, Eotaxin, Fraktalkine, IFNa-2, MCP-3, MDC, IL-1ra, IL-1b, IL-4, IL-7, IP-10, and RANTES (

Figure 6). Five factors showed moderate association (

p = 0.0069): FIT-3L, GRO, IL-12p70, PDGF-AB/BB, and IL-6 (

Figure S3). Nine factors exhibited weaker but still significant trends (

p = 0.0255): EGF, G-CSF, GM-CSF, sCD40L, IL-9, IL-3, IL-8, MIP-1a, and VEGF (

Figure S4). Fifteen factors showed no significant passage-dependent changes (

Figure S5).

Notably, several clusters previously identified showed significant temporal dynamics. Activity of Cluster 6, containing 19 factors including multiple chemokines and growth factors, demonstrated strong passage-dependence (

p = 0.0069). Cluster 7 also showed significant decreases (

p = 0.0069), while Cluster 4 exhibited weaker but significant trends (

p = 0.0255) (

Figure S6).

These findings demonstrate progressive, unidirectional decreases in secreted factor concentrations during in vitro passaging, with particularly strong effects on inflammatory mediators and growth factors.

3. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the long-term effects of diagnostic CT-level radiation on the secretory profile of AD-MSCs. A key aspect of our experimental design was the long-term culturing of AD-MSCs after irradiation, pushing them toward replicative senescence and closely approximating their Hayflick limit. This approach allowed us to model not only the immediate, but the delayed consequences of radiation exposure on AD-MSCs function. It is important to note that maintaining irradiated cells, particularly those receiving higher doses, through multiple passages presented a significant technical challenge due to their reduced proliferative capacity. This resulted in a limited sample size (n = 4) at the middle and late passages (5 and 10, respectively), a constraint that must be considered when interpreting our findings. Furthermore, the AD-MSCs secretome is known to exhibit considerable variability [

12]. Despite these limitations, our data provide compelling evidence that exposure to clinically relevant low-dose radiation regimens can induce significant, passage-dependent alterations in the secretome of AD-MSCs.

Although AD-MSCs are known to maintain functional stability after exposure to ionizing radiation even during long-term culturing [

13], numerous studies have reported alterations in the cellular secretome in response to radiation. For instance, radiation-induced increases in the concentration of IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, and IL-5 are well-documented [

14,

15]. In our study, these interleukins collectively provided a significant distinction between the secretome profiles of AD-MSCs exposed to a single high dose (2 Gy) and those subjected to multiple low doses (5 CT scans) at passage 0. This suggests a crucial role for these cytokines in the immediate cellular response to radiation. Furthermore, this finding underscores that changes in the secretory profile may not be proportional to the total ionizing radiation dose but are dependent on the irradiation regimen.

When investigating the AD-MSCs’ secretome at later passages, we continued to observe non-linear, radiation-dependent changes. Indeed, variations in dose and regimen can yield unpredictable outcomes. For example, Stelcer et al. demonstrated that a 2 Gy dose suppressed cytokine secretion in chondrocyte-like cells differentiated from human induced pluripotent stem cells more strongly than either 1 Gy or 3 Gy doses [

16]. In another study, a 50 mGy dose upregulated IL-6 secretion and downregulated VEGF-A secretion in human gingiva-derived MSCs more potently than higher doses [

17]. Similarly, Schröder et al. reported that irradiating three-dimensional murine endothelial cell culture with 0.01 Gy significantly increased RANTES concentration, whereas higher doses, up to 2 Gy, did not [

18].

A central focus of our study was the long-term culturing of AD-MSCs to model replicative senescence. We identified both passage-dependent radiation effects and a dose- and regimen-independent decline in the concentration of 26 secreted factors. Interestingly, we did not detect a significant increase in the secretion of any factor over successive passages. While IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-8 are described as components of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype, typically upregulated in senescent cells [

19], our study revealed a significant decrease in these factors across all groups, including non-irradiated AD-MSCs. We therefore suggest that replicative senescence in AD-MSCs may mitigate the adverse effects of radiation exposure. Supporting this, we observed a significant passage-dependent reduction in the concentration of the pro-inflammatory chemokines MIP-1a and RANTES, which are known to be induced by radiation [

20].

In summary, our data demonstrate that radiation exposure triggers passage-dependent changes in the AD-MSCs secretome. The early response was characterized by a specific signature of cytokines related to lymphocyte regulation. In contrast, the long-term effect was a generalized decline in secretory function, which was amplified by prior radiation exposure. This indicates that the long-term functional consequences for AD-MSCs are not evident immediately after exposure but manifest after multiple cell divisions. Our findings underscore the importance of considering long-term culture models to fully assess the biological impact of diagnostic radiation on stem cell function.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. AD-MSCs Culture

A primary AD-MSCs culture of passages 5-6, obtained from the collection of Cell Systems LLC (Database: MC16.05.16, Accession numbers: 250716; 270716; 290716; 110816 and 130816, Moscow, Russia), was used. The AD-MSCs were cultured in DMEM medium with 1 g/L of glucose (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) under standard CO2 incubator conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2), changing the medium every three days.

For experimental standardization, passage numbering was reset such that the initial time point was designated as passage 0, with subsequent analyses conducted at passages 5 and 10, corresponding to actual passages 10-11 and 15-16, respectively.

4.2. Irradiation of AD-MSCs

The AD-MSCs were irradiated in the exponential growth phase, when the AD-MSCs population density was 60-70 %.

A TOSHIBA AQUILION 64 CT scanner (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) was used to irradiate AD-MSCs under parameters simulating human head scans (120 kV, 350 mA, 5 mm collimator, pitch 1). Both single and quintuple (with 5 min intervals) irradiations were conducted. Dosimetry was carried out by the thermoluminescent method using aluminum-phosphate dosimeters (by IKS-A DOSIMETRY COMPLEX (IBF, USSR, zav. No. 425)) and dosimeters based on magnesium borate (by Doza-TLD dosimetry complex (NPP Doza, Moscow, Russia)). CTDI was 86 mGy and DLP was 36.7 mGy × cm; the effective head dose was 5.1 mSv (16 cm phantom). For non-standard objects, characteristics like size, mass, and density were considered. AD-MSCs irradiated in 35 mm petri dishes (with 2 mL culture medium volume) received absorbed doses consistent with CTDI values, confirmed by dosimetry: 88 ± 15 mGy per dish per CT session, accounting for spatial heterogeneity and detector error.

An X-ray biological facility (RUST-M1, Diagnostika-M LLC, Moscow, Russia) with two emitters was used for comparative studies and positive control. Irradiation conditions: absorbed dose 2 Gy at 0.85 Gy/min, 200 kV anode voltage, 5 mA current per tube, and a 1.5 mm Al filter. Dosimetry control of the absorbed dose was carried out by the DRK-1M clinical X-ray dosimeter (NPP Doza, Moscow, Russia). The total uncertainty of the dispensed absorbed dose did not exceed 15%.

Thus, the following experimental groups were formed: Control – non-irradiated AD-MSCs; 1 CT scan – AD-MSCs subjected to a single CT scan; 5 CT scans – AD-MSCs irradiated five times with 5-minute intervals; and 2 Gy – AD-MSCs irradiated using the X-ray facility as a positive control.

4.3. Multiplex Analysis

Secreted factors in samples were analyzed with the HCYTMAG-60K-PX41 MILLIPLEX™ magnetic microsphere panel for the detection of human cytokines/chemokines (Merck Millipore, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were analyzed on a MagPix apparatus (Luminex, USA) with xPONENT software (Luminex, USA). All samples contained secreted factors synthesized by 1.0 × 106 cells per 1 ml.

4.4. Data Analysis

All data analyses were performed using Python (v. 3.10) with standard scientific computing libraries.

4.4.1. Data Scaling and Multivariate Exploration

For multivariate exploratory analysis, the concentration data of all secreted factors were z-score normalized. This scaled dataset was used as the input for dimensionality reduction and clustering algorithms. Specifically, we applied PCA and t-SNE for visualization in low-dimensional space.

4.4.2. Cluster Identification and Validation

To identify patterns in secretory profiles of AD-MSCs, hierarchical clustering of the secreted factors was performed on the scaled data using the Euclidean distance metric and average linkage method. The optimal number of clusters (t) was determined by evaluating values from 2 to 10. The quality of each candidate clustering solution was assessed using two complementary approaches.

First, biological coherence was quantified by calculating the mean of the p-values (pmean) obtained from Kruskal-Wallis tests conducted on the non-scaled concentration data of the secreted factors within each cluster, comparing the experimental groups.

Second, the geometric compactness and separation of the clusters were evaluated using the silhouette score. The statistical significance of the silhouette score for the chosen cluster solution was validated with a permutation test (1000 iterations). In this test, a null distribution was generated by calculating the silhouette score on matrices where the relationships between secreted factors were randomly permuted. The p-value was calculated as the proportion of permutations yielding a silhouette score greater than or equal to the observed value.

A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Cluster activity for each sample was then defined as the median of the concentrations of all secreted factors within that cluster.

4.4.3. Statistical Testing

Differences in the levels of individual secreted factors or cluster activities between experimental groups at each passage (0, 5, 10) were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistical significance was defined as p-value of less than 0.05. Significant results were further analyzed with Dunn’s post-hoc test, applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. An adjusted p-value (padj) of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

To assess overall differences in secretome profiles between experimental groups, PERMANOVA was performed. The analysis was conducted on a Euclidean distance matrix calculated from the z-score normalized dataset. The statistical significance of the grouping factor was tested with 1000 permutations under the reduced model. The pseudo-F statistic and associated p-value were calculated by comparing the observed variance explained by the grouping factor to a null distribution generated by random permutation of group labels across samples. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the PERMANOVA. This analysis was performed separately for each passage to evaluate group differences at specific time points, as well as on the combined dataset to assess the overall effect of radiation across the entire experiment.

4.4.4. Effect Size Analysis

The size of observed effects for individual secreted factors was quantified using Hedges’ g (a corrected version of Cohen’s d for small sample sizes). To ensure robust interpretation, only effect sizes with an absolute value exceeding 0.8 were considered significant.

We used the effect size results to discover which secreted factors were the strongest drivers of the differences between experimental groups. For a specific passage, we ranked all secreted factors by the absolute value of their Hedges’ g effect size. We then selected the top N factors from this ranked list (testing N from 1 to 10) and used PERMANOVA to screen if that subset could provide a significant difference between the groups.

4.4.5. Temporal Trends Analysis

Temporal trends in the concentrations of secreted factors across passages (0, 5, 10) were analyzed using Page’s trend test. The analysis included four donors with complete measurements at all passages. For each secreted factor, we tested for consistent monotonic trends, reporting both the direction and statistical significance (α = 0.05). Significant trends were visualized with linear regression lines based on median values.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1. Radiation-induced alterations in cluster activity at passage 5; Figure S2. Radiation-induced alterations in cluster activity at passage 10; Figure S3. Significant trends in secreted factor concentrations across passages (0.001 ≤ p < 0.01); Figure S4. Significant trends in secreted factor concentrations across passages (0.01 ≤ p < 0.05); Figure S5. Secreted factors without significant passage-dependent trends (p ≥ 0.05); Figure S6. Passage-dependent changes in cluster activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.O. and N.Z.; methodology, Т.Т., A.C. and N.V.; formal analysis, A.K. and I.B.; investigation, Т.Т., A.C., A.O., Y.F., P.E., and N.V.; resources, N.V. and A.N.O.; data curation Т.Т., A.C. I.B. and N.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.N.O. and N.Z.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, A.N.O.; project administration, A.N.O.; funding acquisition, A.N.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 23-14-00078).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available fromthe corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marina Prokhorova for help with a multiplex immunoassay, and Andrey Bashkov, Tamara Gimadova, Daniil Alexeyev for their assistance with irradiation and dosimetry.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hsieh, J.; Flohr, T. Computed tomography recent history and future perspectives. Journal of Medical Imaging 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.G.M.; Wang, Y. Advances in the Current Understanding of How Low-Dose Radiation Affects the Cell Cycle. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignatov, M.; Markelova, E.E.; Chigasova, A.; Osipov, A.; Buianov, I.; Fedotov, Y.; Eremin, P.; Vorobyeva, N.; Zyuzikov, N.; Osipov, A.N. Molecular and Cellular Effects of CT Scans in Human Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Meng, L.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. Radiation-Induced Normal Tissue Damage: Oxidative Stress and Epigenetic Mechanisms. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2019, 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, B.; Hill, M.A.; Parsons, J.L. The Cellular Response to Complex DNA Damage Induced by Ionising Radiation. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaiserman, A.; Koliada, A.; Zabuga, O.; Socol, Y. Health Impacts of Low-Dose Ionizing Radiation: Current Scientific Debates and Regulatory Issues. Dose-Response 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osipov, A.; Chigasova, A.; Yashkina, E.; Ignatov, M.; Vorobyeva, N.; Zyuzikov, N.; Osipov, A.N. Early and Late Effects of Low-Dose X-ray Exposure in Human Fibroblasts: DNA Repair Foci, Proliferation, Autophagy, and Senescence. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostyuk, S.V.; Proskurnina, E.V.; Konkova, M.S.; Abramova, M.S.; Kalianov, A.A.; Ershova, E.S.; Izhevskaya, V.L.; Kutsev, S.I.; Veiko, N.N. Effect of Low-Dose Ionizing Radiation on the Expression of Mitochondria-Related Genes in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapel, A. Stem Cells and Irradiation. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunnell, B.A. Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumarwoto, T.; Suroto, H.; Mahyudin, F.; Utomo, D.N.; Romaniyanto; Tinduh, D.; Notobroto, H.B.; Sigit Prakoeswa, C.R.; Rantam, F.A.; Rhatomy, S. Role of adipose mesenchymal stem cells and secretome in peripheral nerve regeneration. Annals of Medicine & Surgery 2021, 67. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro-Machado, E.; Getova, V.E.; Harmsen, M.C.; Burgess, J.K.; Smink, A.M. Towards standardization of human adipose-derived stromal cells secretomes. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports 2023, 19, 2131–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodina, A.V.; Semochkina, Y.P.; Vysotskaya, O.V.; Glukhov, A.I.; Moskaleva, E.Y. Features of the Response of Long-Term Cultured Adipose Tissue–Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells to γ-Irradiation. Biology Bulletin 2022, 48, 2060–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiang, J.G.; Cannon, G. An Update on Dynamic Changes in Cytokine Expression and Dysbiosis Due to Radiation Combined Injury. International journal of molecular sciences 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Tang, Y.; Chen, P.; Ding, Z.; Zhou, M. Unveiling the role of immune response and related cytokines in radiation-induced skin injury: orchestrate inflammation to repair or fibrosis. Radiation Medicine and Protection 2025, 6, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelcer, E.; Kulcenty, K.; Rucinski, M.; Kruszyna-Mochalska, M.; Skrobala, A.; Sobecka, A.; Jopek, K.; Suchorska, W.M. Ionizing radiation exposure of stem cell-derived chondrocytes affects their gene and microRNA expression profiles and cytokine production. Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usupzhanova, D.Y.; Astrelina, T.A.; Kobzeva, I.V.; Suchkova, Y.B.; Brunchukov, V.A.; Rastorgueva, A.A.; Nikitina, V.A.; Samoilov, A.S. Evaluation of Changes in Some Functional Properties of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Induced by Low Doses of Ionizing Radiation. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, S.; Kriesen, S.; Paape, D.; Hildebrandt, G.; Manda, K. Modulation of Inflammatory Reactions by Low-Dose Ionizing Radiation: Cytokine Release of Murine Endothelial Cells Is Dependent on Culture Conditions. Journal of Immunology Research 2018, 2018, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Brown, S.L.; Gordon, M.N. Radiation-induced senescence: therapeutic opportunities. Radiation Oncology 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Y.; Jia, Q.; Chu, Q. The roles of CC chemokines in response to radiation. Radiation Oncology 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).