Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

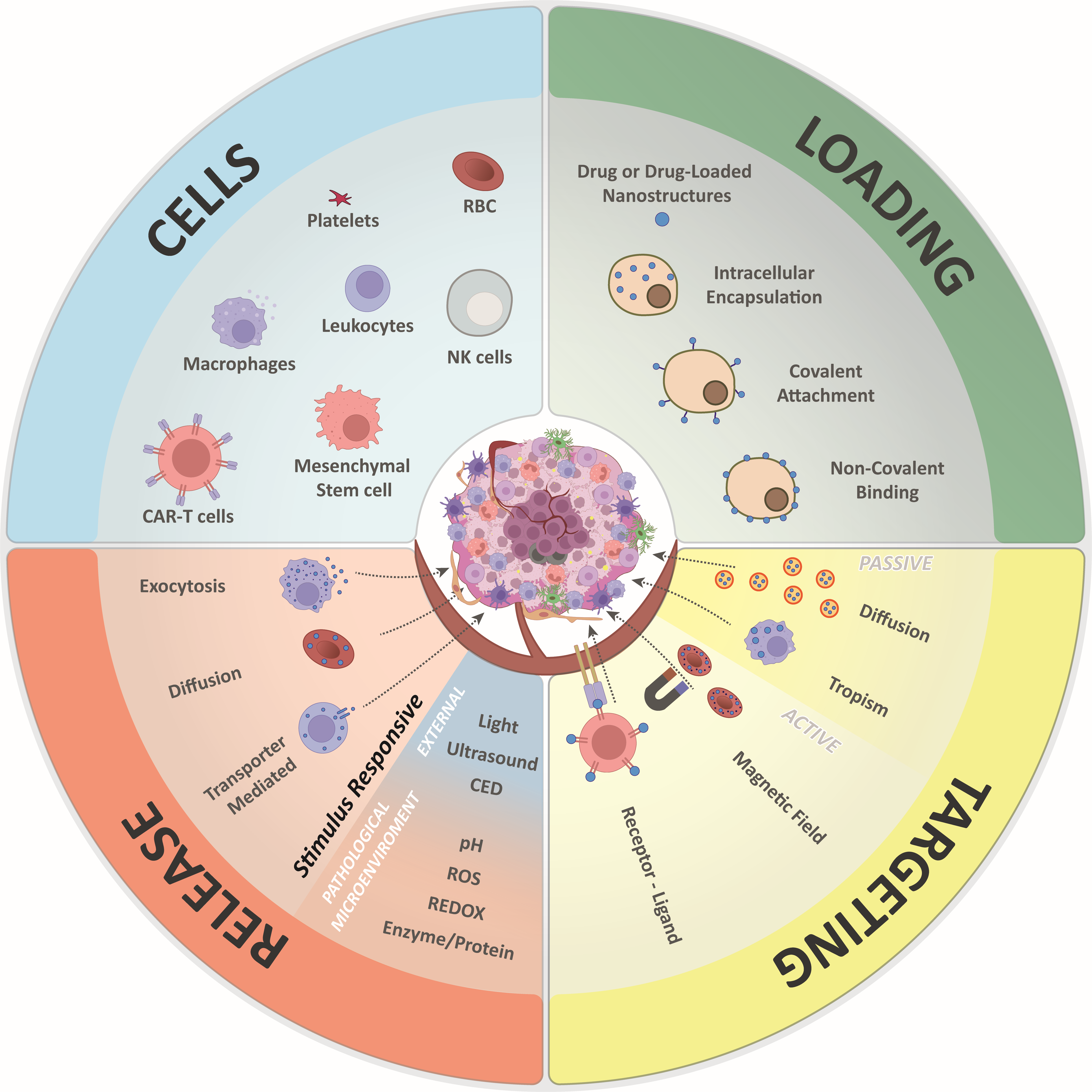

Cell-based drug delivery has emerged as a powerful strategy to improve therapeutic targeting while reducing systemic toxicity. This approach is particularly valuable for anticancer agents, which are often limited by severe side effects arising from off-target activity and non-specific distribution. By using cells as carriers, drugs can evade immune clearance, achieve prolonged circulation, and improve pharmacokinetic profiles, ultimately enhancing therapeutic efficacy. This review surveys the current landscape of cell-mediated drug delivery in oncology, emphasizing both fundamental principles and practical applications. We discuss the design and preparation of cellular carriers, examine the unique characteristics of commonly used cell types, and highlight recent technological innovations that are expanding their theranostic potential, focusing on strategies for delivery to challenging anatomical sites, with a dedicated focus on the brain. By consolidating recent advances and insights, this review aims to provide a comprehensive perspective on the promise and future directions of cell-based drug delivery for cancer therapy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cell-Based Drug Delivery Systems

2.1. Targeting Strategies

2.1.1. Passive Targeting

2.1.2. Active targeting

| Type | Ligand on DDS surface | Linking strategy | Experimental model | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBCs | Folate | DSPE-PEG-folate | 4T-1 cells; in vivo breast model | [32] |

| Nucleolin-binding aptamer |

Lipid-PEG-aptamer | KB cells | [33] | |

| RGD peptide | DSPE-PEG-streptavidin-biotin-PEG-RGD | In vivo glioma model | [23] | |

| Hyaluronidase enzyme | NHS-PEG-rHuPH20 | PC3 cells | [34] | |

| Anti-PECAM and anti-ICAM antibodies | Dual-targeted liposomes | Mouse lungs; ex-vivo human lungs | [8] | |

| Anti-EpCam antibody | DSPE-PEG-biotin-avidin-biotinylated Ab | 4T1 cells | [35] | |

| Mannose | DSPE-PEG-mannose | DC2.4 cells; in vivo melanoma model | [36] | |

| DWSW and NGR | DSPE-PEG-DWSW DSPE-PEG-NGR |

bEnd.3, HUVEC, C6 cells; in vivo glioma model | [37] | |

| NK cells | CD22 ligand | Sialic acid biosynthetic pathway | Raji cells; patient-derived lymphoma cells; in vivo lymphoma model | [38] |

| RAW264.7 | PTK7-binding aptamers | ManM/SH- | CCRF-CEM cells | [39] |

| MSC exosomes | Sgc8 aptamer | Sgc8-COOH/NH2- | B16F0 cells; in vivo melanoma model | [40] |

| MC membranes | RGD peptide | N3/-DBCO | MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells; in vivo breast model | [41] |

| Leukocytes | Anti-PD-1 antibody | -N3/-DBCO | In vivo melanoma and breast models | [42] |

| CAR-T cells | -N3 | -N3/-BCN | Raji cells; in vivo lymphoma model | [43] |

2.2. Loading Strategies

2.2.1. Intracellular Encapsulation

2.2.2. Camouflaged Nanoparticles

2.2.3. Non-Covalent Surface Binding

2.2.4. Surface Covalent Binding

2.3. Drug Release

2.4. Key Features of Major Cell Types

2.4.1. Red Blood Cells

2.4.2. Macrophages

2.4.3. Neutrophils

2.4.5. Mesenchymal Stem Cells

2.4.6. T Cells

2.4.7. Exosomes

3. Current Advance in Theranostic Cell-Based Delivery Systems in Oncology

4. Cells Crossing Barriers on the Path to the Brain

4.1. The Blood-Brain Barrier

4.2. Glioblastoma

4.3. Cell-Mediated Delivery to the Brain

| Type | Modification | Delivery | Agent/Drug | Disease | Ref. | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSCs | Human MSCs | FUS | MCSs | Parkinson's Disease | [173] | 2025 |

| Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs) | IV | Cytopeutics® hUC-MSCs (Neuroncell-EX) | Ischemic Stroke | [174] | 2025 | |

| Muse (Multilineage Differentiating Stress Enduring) Cells | Nasal | Muse cells | Ischemic stroke | [175,176] | 2025 | |

| Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UMSCs) transport miR-124 and programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) | IC | UMSC/miR-124-PD-1 plasmid | Glioblastoma | [176] | 2025 | |

| Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UMSCs) using gadodiamide-concealed magnetic nanoparticles (Gd-FPFNP) | Magnetically | Gadolinium | Glioblastoma | [177] | 2025 | |

| Adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs) with lentiviral transfection | IC | Lentiviral expression of alpha statina (Al-ADSC) | Glioma | [178] | 2025 | |

| Adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs) with MiRNAS and ultra-small paramagnetic nanoparticles (USPNs) | Nasal | hADSCs were transduced with Multi-miR-MUT | Traumatic brain injury | [179] | 2025 | |

| Human Umbellical Cord derived Mesenchimal Stem Cells (hUCMSC) | Intrathecal | hUCMSCs | Spinal cord injuruy | [180] | 2023 | |

| Human Umbellical Cord derived Mesenchimal Stem Cells ( hUCMSC) | In vitro | Secretory factors HGF, BDNF, and TNFR1 | Stoke-brain injury | [181] | 2023 | |

| Adipose derived mesenchimal cells | IP | Th1/Th17 and expansion of Th2/Treg responses | Multiple sclerosis | [182] | 2023 | |

| Allogeneic twin stem cell (TSC) system composed of two tumor-targeting stem cell (SC) populations. | Locoregional | Acquire resistance to oHSV and release immunomodulators, (GM-CSF). | Brain metastasis | [183] | 2023 | |

| Engineered MSCKO- IFNb to co-express scFv-PD1 (MSCKO-IFNb-scFv-PD1) | IC | (MSCKO-IFNb-scFv-PD1) | Glioblastoma | [184] | 2023 | |

| Exosomes | CpG oligodeoxynucleotide–functionalized exosomes (Exo-CpG) | ID | GMB | Glioblastoma | [185] | 2025 |

| Endothelial progenitor cell–derived exosomes (EPC-derived exosomes) | IV / LIPFUS | EPC | Stroke | [186] | 2025 | |

| Decellularized extracellular matrix gel–encapsulated exosomes (dECM@Exo) | IC | hUCMSC | Neuroinflammation | [187] | 2025 | |

| Macrophage-derived exosomes loaded with curcumin and methylene blue | IP | EXO-Cur + MB | Alzheimer’s disease | [188] | 2025 | |

| Mesenchymal stem cell–derived exosomes loaded with rapamycin (Exo-RAPA) | IV | EXO-RAPA | Glioblastoma | [189] | 2025 | |

| Glioblastoma cell–derived exosomes carrying bevacizumab (Exo-BEV) | IV | EXO-BEV | Glioblastoma | [190] | 2025 | |

| Exosomes loaded with a nondegradable form of IκB (Exo-srIκB) | In vitro | Exo-srIκB | Neuroinflammation / Aging | [191] | 2025 | |

| Exosomes engineered with RVG-Lamp2b-Irisin fusion protein | IP | Exos-RVG-Lamp2b-Irisin | Exertional heat stroke (EHS) | [192] | 2025 | |

| Mesenchymal stem cell–derived exosomes (MSC-derived exosomes) | Nasal | MSC | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | [193] | 2025 | |

| Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell–derived exosomes (BMSCs-Exos) | Nasal | BMSC | Autoimmune encephalomyelitis | [194] | 2025 | |

| Exosomes co-loaded with BACE1 siRNA and Berberine | Nasal | MsEVB@R/siRNA | Alzheimer’s disease | [195] | 2025 | |

| Mesenchymal stem cell–derived small extracellular vesicles (MSC-sEVs) | In vitro | sEVs | Alzheimer’s disease | [196] | 2025 | |

| Human-induced pluripotent stem cell–derived neural stem cell exosomes (hiPSC–NSC–Exos) | Nasal | hiPSC–NSC–Exos | Intracerebral hemorrhage | [197] | 2025 | |

| M1-polarized macrophage–derived exosomes (M1 exosomes) | In vitro | MI | Glioblastoma | [198] | 2025 | |

| Sinomenine-treated microglia–derived exosomes | In vitro | SINO-EXO-miRNA-223-3p | Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH) | [199] | 2025 | |

| Virally infected endothelial progenitor cell–derived exosomes carrying HSP90 shSiRNA (EPC-Exos) | Nasal | m-eO-EPC-EXOs | Intracerebral hemorrhage | [200] | 2025 | |

| Human amniotic mesenchymal stem cell–derived anti-CD19 exosomes (anti-CD19-Exo) | IC | Anti-CD19-Exo-MTX | Central nervous system lymphoma (CNSL) | [201] | 2025 | |

| Sca-1⁺-selected multipotent progenitor cell–derived exosomes combined with intraspinal injection of neural stem cells (NSCs) | MSCs IV / NSCs IS | MPC | Spinal cord injury | [202] | 2025 | |

| Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell–derived exosomes loaded with celastrol (BMSC-Exos-Cel) | IV | BMSC-EVs-Cel | Glioblastoma | [203] | 2024 | |

| Human umbilical mesenchymal stem cell–derived exosomes loaded with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (HuMSC-Spion-Ex) | IV with magnetic targeting | SPION-Ex/MF | Post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) | [204] | 2024 | |

| Folic acid–conjugated exosomes co-loaded with temozolomide (TMZ) and quercetin (Qct) | In vitro | TMZ-Qct-Exo-FA | Glioblastoma | [205] | 2024 | |

| Nanofibrous scaffold loaded with mesenchymal stem cells and neural stem cell–derived exosomes (Duo-Exo@NF) | IC | Duo-Exo@NF | Traumatic brain injury (TBI) | [206] | 2024 | |

| Neural Stem Cells (NSCs) | dopaminergic neuron progenitors derived (hiPSCs) in a gel matrix with tacrolimus-loaded microparticles | IC | (hiPSCs) | Parkinson's | [206] | 2025 |

| Encapsulation of tumoricidal neural stem cells (NSCs) within an injectable chitosan (CS) hydrogel | IT | iNSCs) secreting (sTRAIL; sTR) | Glioblastoma | [207] | 2024 | |

| NSCs in biocompatible 3D hydrogel | In vitro | Neural stem cell (NSC)-containing scaffold | Neuronal diseases | [208] | 2024 | |

| Peripheral nerve-derived stem cell (PNSC) exhibiting Schwann cell-like phenotypes | Intrathecal | Peripheral nerve-derived stem cells (PNSCs) | Traumatic brain injury | [209] | 2024 | |

| iNSC)-secreted RANTES/IL-15 enhancing chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4-targeted CAR-T cell | iNSCs-IC/CAR-T-IV | (CSPG4-CAR-T) activity/ RANTES/IL-15 | Glioblastoma | [210] | 2023 | |

| RBCs | Red blood cell membrane–coated docetaxel drug nanocrystals modified with pHA-VAP (pV) | IV | Docetaxel (pV-RBCm-NC(DTX), | Glioma | [211] | 2024 |

| Erythrocyte membrane (EM) functionalized with the tumor-penetrating peptide iRGD (CRGDK/RGPD/EC) | IV | (CRGDK/RGPD/EC)/Temozolomide (TMZ) | Glioblastoma | [212] | 2024 | |

| EM–coated polycaprolactone (PCL) nanoparticles (NPs) loaded with curcumin (Cur) and conjugated with TGNYKALHPHN (TGN) | IV | Curcumin (Cur) — TGN-RBC-NPs-Cur formulation | Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | [212] | 2024 | |

| Nano-erythrosomes | In vitro | Metformin (MET) | Glioblastoma | [213] | 2023 | |

| RBCm- modified with Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) and BSA NPs loaded with SAB and functionalized with | IV | Salvianolic acid B (SAB) | Brain ischemia | [214] | 2022 | |

| Erythro-Magneto-HA-Virosome (EMHV) | Magnetic | EMHV | Glioma | [215] | 2020 | |

| Macrophages | Injectable oxidized high-amylose starch hydrogel (OHASM) containing macrophages | IT | Macrophages and BLZ945 (macrophage-polarizing drug) | Glioblastoma | [216] | 2025 |

| Macrophages loaded with ferritin-conjugated monomethyl auristatin E (MDC) | In vivo | Ferritin-conjugated monomethyl auristatin E (MDC) | Glioblastoma | [217] | 2025 | |

| Engineered M2-like macrophages (eM2-Mφs) | In vitro | Engineered M2-like macrophages (eM2-Mφs) | Glioblastoma | [218] | 2025 | |

| Mitomycin-treated macrophages (Ma)/photosensitizer (PS) | IV | Photosensitizer-loaded macrophages (MaPS) | Glioblastoma | [219] | 2024 | |

| GASC | PLGA nanoparticles (NPs) coated with GASC–glioma cell fusion (SG cell) membranes | IV | Temozolomide (TMZ)-loaded SGNPs | Glioblastoma | [220] | 2023 |

| GASC-secreted CXCL14 promotes glioma cell invasion | In vitro | GASC-secreted CXCL4 | Low-grade glioma | [221] | 2018 | |

| Neutrophils | Mouse neutrophils (NE) loaded with hexagonal boron nitride nanoparticles carrying chlorin e6 (BNPD-Ce6) | IV/ irradiation | BNPD-Ce6@NE | Glioblastoma | [222] | 2025 |

| TMZ-loaded T7-cholesterol nanoparticle / neutrophils | IV | T7/TMZ-conveyed neutrophils (PMN/T7/TMZ) | Glioblastoma | [223] | 2024 | |

| NE- activated by Cyto-Adhesive Micro-Patches (CAMPs) | IP | NE/CAMPs combined with anti-programmed cell death-1 (aPD-1), termed Checkmate 143 | Glioblastoma | [224] | 2024 | |

| Live neutrophils enveloping liposomes containing dexamethasone, ceftriaxone, and oxygen-saturated perfluorocarbon (Lipo@D/C/P) | IV | Lipo@D/C/P | Brain inflammation | [225] | 2024 | |

| Outer Bacterial Membrane | OMVs carried small-interfering RNA (siRNA) and doxorubicin | In vivo | ΔmsbB OMVs + DOX + siCd47 | Glioblastoma | [226] | 2025 |

| Brain-tumor-seeking and serpin-inhibiting outer membrane vesicles (DE@OMVs) | IV | DE@OMVs (Dexamethasone / Embelin) | Metastatic glioblastoma | [227] | 2024 | |

| Pioglitazone encapsulation (PGZ) | In vivo | OMV@PGZ | Stroke | [228] | 2023 | |

| Doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded bacterial outer membrane vesicles (OMVs/DOX) | IV | Doxorubicin-loaded outer membrane vesicles (OMVs/DOX) | Glioma therapy | [229] | 2023 | |

| Lipopolysaccharide-free EC-K1 outer membrane | IV | dOMV@NPs | Glioblastoma | [230] | 2022 |

4.3.1. RBCs

4.3.2. Mesenchymal Cells

4.3.3. Exosomes

4.3.4. Adoptive Cell Transfer (ACT)

4.3.4.1. CAR-T Cells Crossing the BBB

| Clin. Trial Id. | Modification | Delivery | Agent/drug | Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT05168423 | Bivalent (CAR) T cells targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) epitope 806 and interleukin-13 receptor alpha 2 (IL-13Rα2). | Intrathecal | CART-EGFR-IL13Rα2 | EGFR-amplified recurrent glioblastoma |

| NCT02208362 | IL-13 cytokine-directed CAR mutated at a single site (E12Y) and incorporating a 4-1BB costimulatory domain. | ICV | CART-EGFR-IL13Rα2 | Glioblastoma |

| NCT05660369 | (CAR) T cells targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) variant III tumor-specific antigen, as well as the wild-type EGFR protein. | ICV | CARv3-TEAM | Glioblastoma |

| NCT06815029 | IL13Rα2-targeting chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells with CRISPR knockout of TGFβR2. | IC | TGFβR2KO/IL13Rα2-CAR T | IDH-mutant astrocytoma, grade 3/4 |

| NCT06482905 | Anti-B7-H3 CAR-T cell injection (Tx103). | IV | TX103 | Recurrent progressive grade 4 glioma |

| NCT06186401 | Anti-EphA2/IL-13Rα2 CAR (E-SYNC) T cells. | IV | E-SYNC T | EGFRvIII-positive glioblastoma |

| NCT04185038 | Autologous CD4+ and CD8+ T cells lentivirally transduced to express a B7-H3-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). | ICV | B7-H3 CAR-T | Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) |

| NCT05835687 | Autologous B7-H3-CAR T cells. | OR | Loc3CAR | Primary CNS tumors |

| NCT05577091 | The autologous Tris-CAR-T cell, targeting both CD44 and CD133, the two inversely correlated targets, with truncated IL7Ra. | OR | Tris-CAR-T | Glioblastoma |

| NCT05366179 | (CAR) T cells expressing B7-H3-specific chimeric antigen receptors. | ICV | CAR-B7-H3T | Glioblastoma |

| NCT05353530 | IL-8 receptor-modified CD70 CAR T cells. | IV | 8R-70CAR | CD70-positive adult glioblastoma |

| NCT03726515 | EGFRvIII-directed CAR T cells and PD-1 inhibition. | Infusion | CART-EGFRvIII T and Pembrolizumab | MGMT-unmethylated glioblastoma |

| NCT03283631 | EGFRvIII CAR-T cells. | CED | EGFRvIII-CAR | Glioblastoma |

| NCT02664363 | EGFRvIII CARs. | IV | EGFRvIII CARs | Newly diagnosed grade IV malignant glioma |

| NCT01109095 | CD28 attached to the HER2 chimeric receptor (HER2-CAR). | IV | HER2-CD28 CMV-T cells | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| NCT07209241 | CART-EGFR-IL13Rα2. | Dosing schedules |

CART-EGFR-IL13Rα2 | EGFR-amplified glioblastoma |

| NCT07193628 | EPC-003 Fully Human Anti-B7H3/IL13Ra2 Armored CAR-T Cell Therapy | OR | EPC-003 CAR-T | Refractory Glioblastoma and Recurrent Glioblastoma |

| NCT07180927 | Delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3)-specific CAR-T cells. | IV | DLL3-CAR-T | DLL3 positive brain tumors including glioblastomas and diffused intrinsic pontine or midline gliomas |

| NCT06815432 | Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) derived from an antibody called GC33. | Dosing schedules |

GC33-CAR-T | GPC3-positive brain tumors |

| NCT06691308 | WL276 CAR-T cells. | IC | WL276 CAR-T | Recurrent glioblastoma |

| NCT07209241 | CART-EGFR-IL13Rα2 | IC | SNC-109 CAR-T | EGFR-Amplified Recurrent Glioblastoma |

| NCT05835687 | B7-H3-CAR with a CD28z signaling domain and 41BB ligand (B7-H3-CAR T cells | Locoregional | B7-H3 CAR-T | Diffuse midline glioma |

| NCT05802693 | EGFRvIII CAR-T | ICV | EGFRvIII CAR-T | Recurrent glioblastoma |

| NCT05474378 | B7-H3 chimeric antigen receptor T cells (B7-H3CART). | ICV/IT | B7-H3-CART | Recurrent glioblastoma |

| NCT05063682 | EGFRvIII CAR-T cells (EGFRvIII-specific hinge-optimized CD3ζ-stimulatory/41BB-co-stimulatory chimeric antigen receptor autologous T-lymphocytes). | ICV | EGFRvIII-CAR T | Leptomeningeal disease from glioblastoma |

| NCT04385173 | Safety and efficacy of B7-H3 CAR-T therapy between temozolomide cycles. | OR | B7-H3-CART | Refractory glioblastoma |

| NCT04214392 | Chlorotoxin (EQ)-CD28-CD3ζ-CD19t-expressing CAR T lymphocytes (NCI SYs). | IT/ICV | (EQ)-CD28-CD3zeta-CD19t-CAR T | Recurrent MPP2-positive glioblastoma |

| NCT04045847 | CD147-CAR-T cells. | OR | CD147-CART | Recurrent glioblastoma |

| NCT04003649 | IL13Rα2-CAR T cells (IL13Rα2-specific hinge-optimized 4-1BB costimulatory CAR/truncated CD19-expressing autologous TN/MEM cells). | ICV/IT | IL13Rα2-CAR T | Resectable recurrent glioblastoma |

| Modification | Delivery | Agent/drug | Treatment | Disease | Ref. | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αβ T cells engineered with a high-affinity γ9δ2 T-cell receptor (TEGs) recognizing virally infected cells via BTN2A1 and BTN3A | In vitro | OVs and Vγ9Vδ2 TCR | OV therapy and increased immunetherapy | Pediatric Diffuse Midline Gliomas (DMGs) | [249] | 2025 |

| Prostaglandin F2 receptor negative regulator (PTGFRN)-targeting 5E17-CAR-T cells | IC | 5E17-CAR-T | Immunotherapy | Glioblastoma | [250] | 2025 |

| NKG2D CAR-T cells combined with sodium valproate (VPA) | IV | NKG2D CAR-T+VPA | antitumoral activity | Glioblastoma | [251] | 2025 |

| Gamma delta (γδ) T cells | In vitro | Gamma Delta (γδ)T cells | immune infiltration | Medulloblastoma | [252] | 2025 |

| Fourth-generation combined PSMA- and GD2-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells | IV | PSMA /GD2 CAR-T cell | immunetherapy | Refractory Glioma | [243] | 2025 |

| FLASH therapy combined with GD2 CAR-T cell immunotherapy | IC | GD2 CAR-T |

Sensitization by radiatoin and Reverse immunosuppression | Medulloblastoma | [244] | 2025 |

| CD70-specific CAR-T cells transduced with two third-generation oncolytic adenoviruses (OAds; E1B19K/E3-deleted, replication-selective): OAd-GFP (control) or OAd-IL15 (TS-2021) | IT | CAR-TOAd-GFP and CAR-TTS-2021 | Viral oncolysis/ immunotherapy | Glioblastoma | [253] | 2025 |

| CD44/CD133 dual-targeting CAR-T cells | IC | Tanζ-T28-Δ7R CAR-T cell |

Antitumoral activity | Glioblastoma | [242] | 2025 |

| CAR-Vδ1 T cells targeting B7-H3 and IL-13Rα2 | IT | CAR-Vδ1 T cell cocktail | Multi-step strategy for CAR-Vδ1 T cell cocktail therapy | Heterogeneous Glioblastoma | [246] | 2025 |

| CAR-T cells utilizing monomeric streptavidin-2 (mSA2) | IT | mSA2 CAR-T | Antiproliferative and hetergeneity targeting immunoterapy | Glioblastoma | [246] | 2024 |

| CAR-T cells targeting B7-H3 | IC | B7-H3 CAR | Antitumor | Glioblastoma | [254] | 2025 |

| Bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells | IC | anti-CD87 BiTE and CD87-specific CAR/IL-12 T | Increased immunogenicity and immunotherapy | Invasive Nonfunctioning Pituitary Adenomas (iNFPAs) | [245] | 2024 |

| Antigen-sensitive B7-H3-targeting nanobody-based CAR-T cells | IV | B7-H3 nanoCAR-T | Tumor growth control | Glioblastoma (Xenograft) | [255] | 2024 |

| Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells producing IL-7 and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 19 (CCL19) | IV | IL 7 × 19 CAR-T | Antiproliferative | Glioblastoma / Pancreatic Cancer | [256] | 2024 |

| Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapies targeting glioblastoma-associated antigens such as interleukin-13 receptor subunit alpha-2 (IL-13Rα2) | IV | IL-13Rα2/ TGF-β bispecific CAR-T | Reduction of immunosuppression via TGF-β | Glioblastoma | [257] | 2024 |

| Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells targeting GD2 | IV / IC | GD2-CART | Tumor regression | H3K27M-Mutant Diffuse Midline Gliomas (DMGs) | [257] | 2024 |

4.3.4.2. Tumor Infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACT | Adoptive cell transfer |

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CED | Convection enhanced delivery |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSFB | Cerebral spinal fluid-blood barrier |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DDS | Drug delivery system |

| EPR | Enhanced permeability and retention |

| GASCs | Glioma-associated stem cells |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| ICG | Indocyanine green |

| MC | Macrophages |

| MPS | Mononuclear phagocytic system |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MSC | Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| NETs | Neutrophils extracellular traps |

| NIR | Near Infrared |

| NK | Natural Killer cells |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| PAI | Photoacoustic Imaging |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PLGA | Polylactic-co-glycolic acid |

| RBC | Red blood cell |

| SPIONs | Superparamagnetic iron oxides nanoparticles |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TIL | Tumor Infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| US | Ultrasound |

References

- Basak, D.; Arrighi, S.; Darwiche, Y.; Deb, S. Comparison of Anticancer Drug Toxicities: Paradigm Shift in Adverse Effect Profile. Life 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezike, T.C.; Okpala, U.S.; Onoja, U.L.; Nwike, C.P.; Ezeako, E.C.; Okpara, O.J.; Okoroafor, C.C.; Eze, S.C.; Kalu, O.L.; Odoh, E.C.; et al. Advances in Drug Delivery Systems, Challenges and Future Directions. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Guo, B.; Gu, J.; Ta, N.; Gu, J.; Yu, H.; Sun, M.; Han, T. Emerging Advances in Drug Delivery Systems (DDSs) for Optimizing Cancer Complications. Mater Today Bio 2025, 30, 101375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Kaneko, M.; Narukawa, M. Approval Success Rates of Drug Candidates Based on Target, Action, Modality, Application, and Their Combinations. Clin Transl Sci 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davodabadi, F.; Sajjadi, S.F.; Sarhadi, M.; Mirghasemi, S.; Nadali Hezaveh, M.; Khosravi, S.; Kamali Andani, M.; Cordani, M.; Basiri, M.; Ghavami, S. Cancer Chemotherapy Resistance: Mechanisms and Recent Breakthrough in Targeted Drug Delivery. Eur J Pharmacol 2023, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Peng, J. Cell-Based Drug Delivery Systems and Their in Vivo Fate. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2022, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, M.; Li, T.; Niu, M.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Wu, K.; Dai, Z. Targeting Cytokine and Chemokine Signaling Pathways for Cancer Therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.T.; Hood, E.D.; Shuvaeva, T.; Shuvaev, V. V.; Basil, M.C.; Wang, Z.; Nong, J.; Ma, X.; Wu, J.; Myerson, J.W.; et al. Dual Affinity to RBCs and Target Cells (DART) Enhances Both Organ- and Cell Type-Targeting of Intravascular Nanocarriers. ACS Nano 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiet, P.; Berlin, J.M. Exploiting Homing Abilities of Cell Carriers: Targeted Delivery of Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy. Biochem Pharmacol 2017, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; He, S.; Yin, Y.; Liu, H.; Hu, J.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W. Combination of Nanomaterials in Cell-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.R.; Bardhan, R.; Stanton-Maxey, K.J.; Badve, S.; Nakshatri, H.; Stantz, K.M.; Cao, N.; Halas, N.J.; Clare, S.E. Delivery of Nanoparticles to Brain Metastases of Breast Cancer Using a Cellular Trojan Horse. Cancer Nanotechnol 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, C.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y.; Fang, J. Engineered Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells against Cancer. Cell Death Dis 2025, 16, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. Du; Min, H.K.; Kim, H.Y.; Han, J.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, C.S.; Park, J.O.; Choi, E. Primary Macrophage-Based Microrobots: An Effective Tumor Therapy in Vivo by Dual-Targeting Function and Near-Infrared-Triggered Drug Release. ACS Nano 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, K.; Li, T.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Y.; Liu, X.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Han, M.; et al. Monocyte-Mediated Chemotherapy Drug Delivery in Glioblastoma. Nanomedicine 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, H.; Tie, C.; Yan, C.; Deng, Z.; Wan, Q.; Liu, X.; Yan, F.; Zheng, H. MR Imaging Tracking of Inflammation-Activatable Engineered Neutrophils for Targeted Therapy of Surgically Treated Glioma. Nat Commun 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.; Chuvin, N.; Valladeau-Guilemond, J.; Depil, S. Development of NK Cell-Based Cancer Immunotherapies through Receptor Engineering. Cell Mol Immunol 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.Y.; Oskarsson, T.; Acharyya, S.; Nguyen, D.X.; Zhang, X.H.F.; Norton, L.; Massagué, J. Tumor Self-Seeding by Circulating Cancer Cells. Cell 2009, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Pan, H.; Luo, Y.; Yin, T.; Zhang, B.; Liao, J.; Wang, M.; Tang, X.; Huang, G.; Deng, G.; et al. Nanoengineered CAR-T Biohybrids for Solid Tumor Immunotherapy with Microenvironment Photothermal-Remodeling Strategy. Small 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Gupta, V.; Zern, B.J.; Pan, D.; Zakrewsky, M.; Muzykantov, V.; Mitragotri, S. Delivering Nanoparticles to Lungs While Avoiding Liver and Spleen through Adsorption on Red Blood Cells. ACS Nano 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, J.S.; Mitragotri, S.; Muzykantov, V.R. Red Blood Cell Hitchhiking: A Novel Approach for Vascular Delivery of Nanocarriers. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimnejad, P.; Sodagar Taleghani, A.; Asare-Addo, K.; Nokhodchi, A. An Updated Review of Folate-Functionalized Nanocarriers: A Promising Ligand in Cancer. Drug Discov Today 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, N.E.M.; Dhingra, S.; Jois, S.D.; Da Vicente, M.G.H. Molecular Targeting of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (Egfr) and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor (Vegfr). Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Ran, D.; Lu, L.; Zhan, C.; Ruan, H.; Hu, X.; Xie, C.; Jiang, K.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; et al. Ligand-Modified Cell Membrane Enables the Targeted Delivery of Drug Nanocrystals to Glioma. ACS Nano 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Cheng, Z.; Zhao, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, A.; Gan, W.; Zhang, Y. Active Targeting Schemes for Nano-Drug Delivery Systems in Osteosarcoma Therapeutics. J Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondengadan, S.M.; Bansal, S.; Yang, C.; Liu, D.; Fultz, Z.; Wang, B. Click Chemistry and Drug Delivery: A Bird’s-Eye View. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agard, N.J.; Prescher, J.A.; Bertozzi, C.R. A Strain-Promoted [3 + 2] Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition for Covalent Modification of Biomolecules in Living Systems. J Am Chem Soc 2004, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, Y.; Kusamori, K.; Nishikawa, M. Click Chemistry as a Tool for Cell Engineering and Drug Delivery. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, W.; Xiao, P.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, G.; Cao, H.; Wang, D.; et al. Recent Advances in Developing Active Targeting and Multi-Functional Drug Delivery Systems via Bioorthogonal Chemistry. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifantini, R.; Taranta, M.; Gherardini, L.; Naldi, I.; Parri, M.; Grandi, A.; Giannetti, A.; Tombelli, S.; Lucarini, G.; Ricotti, L.; et al. Magnetically Driven Drug Delivery Systems Improving Targeted Immunotherapy for Colon-Rectal Cancer. Journal of Controlled Release 2018, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzoca, A.; Lucarini, G.; Tognoni, E.; Tognarelli, S.; Ricotti, L.; Gherardini, L.; Pelosi, G.; Pellegrino, M.; Menciassi, A.; Grimaldi, S.; et al. Erythro–Magneto–HA–Virosome: A Bio-Inspired Drug Delivery System for Active Targeting of Drugs in the Lungs. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, D.; He, C.; Wang, D.; Wei, M.; Zheng, S.; Li, J. Adoptive Transfer of Fe3O4-SWCNT Engineered M1-like Macrophages for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2023, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fang, H.; Liu, Q.; Gai, Y.; Yuan, L.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Hou, Y.; Gao, M.; Lan, X. Red Blood Cell Membrane-Coated Upconversion Nanoparticles for Pretargeted Multimodality Imaging of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Biomater Sci 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.H.; Hu, C.M.J.; Chen, K.N.H.; Luk, B.T.; Carpenter, C.W.; Gao, W.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.E.; Lu, W.; Zhang, L. Lipid-Insertion Enables Targeting Functionalization of Erythrocyte Membrane-Cloaked Nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Fan, Z.; Lemons, P.K.; Cheng, H. A Facile Approach to Functionalize Cell Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles. Theranostics 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.M.; Xie, W.; Xiao, Y.S.; Suo, M.; Zan, M.H.; Liao, Q.Q.; Hu, X.J.; Chen, L. Ben; Chen, B.; Wu, W.T.; et al. Erythrocyte Membrane-Coated Gold Nanocages for Targeted Photothermal and Chemical Cancer Therapy. Nanotechnology 2018, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, D.; Song, Q.; Wu, T.; Zhuang, X.; Bao, Y.; Kong, M.; Qi, Y.; Tan, S.; Zhang, Z. Erythrocyte Membrane-Enveloped Polymeric Nanoparticles as Nanovaccine for Induction of Antitumor Immunity against Melanoma. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6918–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Sun, J.; Hao, W.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Xu, F.; Gao, C. Dual-Target Peptide-Modified Erythrocyte Membrane-Enveloped PLGA Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Glioma. Front Oncol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lang, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X.; Fang, Z.; Weng, J.; Lu, N.; Wu, X.; Li, T.; et al. Glycoengineering of Natural Killer Cells with CD22 Ligands for Enhanced Anticancer Immunotherapy. ACS Cent Sci 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, S.; Moriyama, R.; Mori, T.; Iwasaki, Y. Surface Engineering of Macrophages with Nucleic Acid Aptamers for the Capture of Circulating Tumor Cells. Chemical Communications 2015, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, E.; Ramezani, M.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Amel Farzad, S.; Nekooei, S.; Alibolandi, M. Targeted Theranostic Oxygen-Filled and Doxorubicin-Loaded Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes-Based-Nanobubble against Melanoma. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2025, 105, 106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhao, L.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Lu, G.; Luo, N.; Gao, X.; Ma, G.; Xie, H.; Wei, W. Construction of a Biomimetic Magnetosome and Its Application as a SiRNA Carrier for High-Performance Anticancer Therapy. Adv Funct Mater 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, F.; Lu, G.H.; Nie, W.; Zhang, L.; Lv, Y.; Bao, W.; Gao, X.; Wei, W.; Pu, K.; et al. Engineering Magnetosomes for Ferroptosis/Immunomodulation Synergism in Cancer. ACS Nano 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Y.; He, W.; Wang, M.; Tang, X.; He, H.; Liu, L.; Zheng, M.; et al. Click CAR-T Cell Engineering for Robustly Boosting Cell Immunotherapy in Blood and Subcutaneous Xenograft Tumor. Bioact Mater 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Qin, J.; Han, L.; Zhao, W.; Liang, J.; Xie, Z.; Yang, P.; Wang, J. Exploiting Macrophages as Targeted Carrier to Guide Nanoparticles into Glioma. Oncotarget 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M.D.; Li, B.; Zhang, M.K.; Feng, J.; Zhang, X.Z. Artificially Reprogrammed Macrophages as Tumor-Tropic Immunosuppression-Resistant Biologics to Realize Therapeutics Production and Immune Activation. Advanced Materials 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvinova, L.S.; Shupletsova, V. V.; Khaziakhmatova, O.G.; Daminova, A.G.; Kudryavtseva, V.L.; Yurova, K.A.; Malashchenko, V. V.; Todosenko, N.M.; Popova, V.; Litvinov, R.I.; et al. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Carrier for a Cell-Mediated Drug Delivery. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Thapa, R.; Naushin, F.; Gupta, S.; Bhar, B.; De, R.; Bhattacharya, J. Antibiotic-Loaded Smart Platelet: A Highly Effective Invisible Mode of Killing Both Antibiotic-Sensitive and -Resistant Bacteria. ACS Omega 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, N.; Mitragotri, S. Macrophages Recognize Size and Shape of Their Targets. PLoS One 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Cerroni, B.; Razuvaev, A.; Härmark, J.; Paradossi, G.; Caidahl, K.; Gustafsson, B. Cellular Uptake of Plain and SPION-Modified Microbubbles for Potential Use in Molecular Imaging. Cell Mol Bioeng 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berikkhanova, K.; Taigulov, E.; Bokebaev, Z.; Kusainov, A.; Tanysheva, G.; Yedrissov, A.; Seredin, G.; Baltabayeva, T.; Zhumadilov, Z. Drug-Loaded Erythrocytes: Modern Approaches for Advanced Drug Delivery for Clinical Use. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinti, C.; Taranta, M.; Naldi, I.; Grimaldi, S. Newly Engineered Magnetic Erythrocytes for Sustained and Targeted Delivery of Anti-Cancer Therapeutic Compounds. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M.; Tajerzadeh, H.; Dehpour, A.R.; Rouini, M.R.; Ejtemaee-Mehr, S. In Vitro Characterization of Human Intact Erythrocytes Loaded by Enalaprilat. Drug Delivery: Journal of Delivery and Targeting of Therapeutic Agents. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, E.J.; Hou, J.H.; Kim, J.M.; Choi, H.G.; Shim, C.K.; Oh, Y.K. Opsonized Erythrocyte Ghosts for Liver-Targeted Delivery of Antisense Oligodeoxynucleotides. Biomaterials 2009, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Liu, S.; Wu, X.; Raza, F.; Li, Y.; Yuan, W.; Qiu, M.; Su, J. Autologous Erythrocytes Delivery of Berberine Hydrochloride with Long-Acting Effect for Hypolipidemia Treatment. Drug Deliv 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavu, L.M.; Antonelli, A.; Scarpa, E.S.; Abdalla, P.; Wilhelm, C.; Silvestri, N.; Pellegrino, T.; Scheffler, K.; Magnani, M.; Rinaldi, R.; et al. Optimization of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Engineering Erythrocytes as Theranostic Agents. Biomater Sci 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, B.I.; Demirbolat, G.M.; Cevik, O. Wharton Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes Induce Apoptosis and Suppress EMT Signaling in Cervical Cancer Cells as an Effective Drug Carrier System of Paclitaxel. PLoS One 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, D.; Wen, S.; Shen, L.; Lin, Q. Augmented Cellular Uptake and Homologous Targeting of Exosome-Based Drug Loaded IOL for Posterior Capsular Opacification Prevention and Biosafety Improvement. Bioact Mater 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannull, J.; Nair, S.K. Transfecting Human Monocytes with RNA. In Methods in Molecular Biology; 2016; Vol. 1428.

- Nguyen, V. Du; Min, H.K.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, C.S.; Han, J.; Park, J.O.; Choi, E. Macrophage-Mediated Delivery of Multifunctional Nanotherapeutics for Synergistic Chemo-Photothermal Therapy of Solid Tumors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Tang, W.; Wen, R.; Zhou, S.; Lee, C.; Wang, H.; Jiang, W.; Delahunty, I.M.; Zhen, Z.; et al. Nanoparticle-Laden Macrophages for Tumor-Tropic Drug Delivery. Advanced Materials 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, H.Y.; Ju, E.J.; Jung, J.; Park, J.; Chung, H.K.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, J.S.; Park, H.J.; Song, S.Y.; et al. Use of Macrophages to Deliver Therapeutic and Imaging Contrast Agents to Tumors. Biomaterials 2012, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, J.J.; Saha, S. A Nanoparticle’s Journey to the Tumor: Strategies to Overcome First-Pass Metabolism and Their Limitations. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oroojalian, F.; Beygi, M.; Baradaran, B.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Shahbazi, M.A. Immune Cell Membrane-Coated Biomimetic Nanoparticles for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Small 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimohammadvand, S.; Kaveh Zenjanab, M.; Mashinchian, M.; Shayegh, J.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R. Recent Advances in Biomimetic Cell Membrane–Camouflaged Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 177, 116951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.Q.; Li, X.; Dai, H.W. Hybrid Cell Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles: A Multifunctional Biomimetic Platform for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Acta Biomater 2020, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, X. Stem Cell Membrane-Camouflaged Targeted Delivery System in Tumor. Mater Today Bio 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; He, G.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, Q.; Wen, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. DNA Base Pairing-Inspired Supramolecular Nanodrug Camouflaged by Cancer-Cell Membrane for Osteosarcoma Treatment. Small 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, Q.; Ding, S.; Dong, X.; Xue, L.; Zhu, Q.; Zhou, J.; Xia, F.; Wang, S.; et al. Red Blood Cell Membrane-Camouflaged Nanoparticles Loaded with AIEgen and Poly(I: C) for Enhanced Tumoral Photodynamic-Immunotherapy. Natl Sci Rev 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.F.; Correia, I.J.; Moreira, A.F. Red Blood Cell Membrane-Camouflaged Gold-Core Silica Shell Nanorods for Cancer Drug Delivery and Photothermal Therapy. Int J Pharm 2024, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; Ouyang, B.; Liu, H.; Pang, Z.; Yang, W. Platelet Membrane-Camouflaged Magnetic Nanoparticles for Ferroptosis-Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Small 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, X.; Dong, H.; Liu, H.; Gui, R.; Nie, X. Platelet-Membrane-Camouflaged Zirconia Nanoparticles Inhibit the Invasion and Metastasis of Hela Cells. Front Chem 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, F.; Mohammed, M.; Jan, N.; Lulek, E.; Ertas, Y.N. T Cell and Natural Killer Cell Membrane-Camouflaged Nanoparticles for Cancer and Viral Therapies. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2024, 7, 2637–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, N.; Pishavar, E.; Baradaran, B.; Oroojalian, F.; Mokhtarzadeh, A. Stem Cell Membrane, Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Hybrid Stem Cell Camouflaged Nanoparticles: A Promising Biomimetic Nanoplatforms for Cancer Theranostics. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, R.; Zhou, M.; Liu, J.; Dong, K.; Zhao, S.; Cao, J.; Wang, W.; Sun, C.; Wu, S.; et al. Homologous Cancer Cell Membrane-Camouflaged Nanoparticles Target Drug Delivery and Enhance the Chemotherapy Efficacy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Lett 2023, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Zheng, M.; Shi, B. Cancer Cell-Mitochondria Hybrid Membrane Coated Gboxin Loaded Nanomedicines for Glioblastoma Treatment. Nat Commun 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Shen, S.; Fan, Q.; Chen, G.; Archibong, E.; Dotti, G.; Liu, Z.; Gu, Z.; Wang, C. Red Blood Cell-Derived Nanoerythrosome for Antigen Delivery with Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Sci Adv 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Wu, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Cancer-Erythrocyte Hybrid Membrane-Camouflaged Magnetic Nanoparticles with Enhanced Photothermal-Immunotherapy for Ovarian Cancer. ACS Nano 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luan, Z.; Zhao, C.; Bai, C.; Yang, K. Target Delivery Selective CSF-1R Inhibitor to Tumor-Associated Macrophages via Erythrocyte-Cancer Cell Hybrid Membrane Camouflaged PH-Responsive Copolymer Micelle for Cancer Immunotherapy. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Li, Q.; Deng, J.; Shen, J.; Xu, W.; Yang, W.; Chen, B.; Du, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ge, F.; et al. Platelet-Tumor Cell Hybrid Membrane-Camouflaged Nanoparticles for Enhancing Therapy Efficacy in Glioma. Int J Nanomedicine 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, J.S.; Pan, D.C.; Myerson, J.W.; Marcos-Contreras, O.A.; Villa, C.H.; Patel, P.; Hekierski, H.; Chatterjee, S.; Tao, J.Q.; Parhiz, H.; et al. Red Blood Cell-Hitchhiking Boosts Delivery of Nanocarriers to Chosen Organs by Orders of Magnitude. Nat Commun 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelepukin, I. V.; Yaremenko, A. V.; Shipunova, V.O.; Babenyshev, A. V.; Balalaeva, I. V.; Nikitin, P.I.; Deyev, S.M.; Nikitin, M.P. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery: Via RBC-Hitchhiking for the Inhibition of Lung Metastases Growth. Nanoscale 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ukidve, A.; Gao, Y.; Kim, J.; Mitragotri, S. Erythrocyte Leveraged Chemotherapy (ELeCt): Nanoparticle Assembly on Erythrocyte Surface to Combat Lung Metastasis. Sci Adv 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.H.; Pan, D.C.; Johnston, I.H.; Greineder, C.F.; Walsh, L.R.; Hood, E.D.; Cines, D.B.; Poncz, M.; Siegel, D.L.; Muzykantov, V.R. Biocompatible Coupling of Therapeutic Fusion Proteins to Human Erythrocytes. Blood Adv 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, N.; Deng, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhou, J.; Chen, S.; Shi, J.; Zhu, G. Enhancing Circulation and Tumor Accumulation of Carboplatin via an Erythrocyte-Anchored Prodrug Strategy. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. [CrossRef]

- Stephan, M.T.; Moon, J.J.; Um, S.H.; Bersthteyn, A.; Irvine, D.J. Therapeutic Cell Engineering with Surface-Conjugated Synthetic Nanoparticles. Nat Med 2010, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Sun, M.; Li, B.; Pan, F.; Ma, A.; Liao, J.; Yin, T.; Tang, X.; Huang, G.; et al. IL-12 Nanochaperone-Engineered CAR T Cell for Robust Tumor-Immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2022, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yang, S.; Tu, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Yuan, Y.; Lian, Z. Bioorthogonal Equipping CAR-T Cells with Hyaluronidase and Checkpoint Blocking Antibody for Enhanced Solid Tumor Immunotherapy. ACS Cent Sci 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Wu, G.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.L.; Ding, J.; Jiang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Pu, K.; et al. Responsive Exosome Nano-Bioconjugates for Synergistic Cancer Therapy. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qin, Z.; Sun, H.; Chen, X.; Dong, J.; Shen, S.; Zheng, L.; Gu, N.; Jiang, Q. Nanoenzyme Engineered Neutrophil-Derived Exosomes Attenuate Joint Injury in Advanced Rheumatoid Arthritis via Regulating Inflammatory Environment. Bioact Mater 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani Giri, P.; Banerjee, A.; Ghosal, A.; Salu, P.; Reindl, K.; Layek, B. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Delivered Paclitaxel Nanoparticles Exhibit Enhanced Efficacy against a Syngeneic Orthotopic Mouse Model of Pancreatic Cancer. Int J Pharm 2024, 666, 124753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessina, A.; Bonomi, A.; Coccè, V.; Invernici, G.; Navone, S.; Cavicchini, L.; Sisto, F.; Ferrari, M.; Viganò, L.; Locatelli, A.; et al. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Primed with Paclitaxel Provide a New Approach for Cancer Therapy. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpa, E.; Bailey, J.L.; Janeczek, A.A.; Stumpf, P.S.; Johnston, A.H.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Woo, Y.L.; Cheong, Y.C.; Evans, N.D.; Newman, T.A. Quantification of Intracellular Payload Release from Polymersome Nanoparticles. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagiotti, S.; Pirla, E.; Magnani, M. Drug Transport by Red Blood Cells. Front Physiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zou, D.; Zhao, A.; Yang, P. Design and Optimization of the Circulatory Cell-Driven Drug Delivery Platform. Stem Cells Int 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.C.; Chiang, W.H.; Cheng, Y.H.; Lin, W.C.; Yu, C.F.; Yen, C.Y.; Yeh, C.K.; Chern, C.S.; Chiang, C.S.; Chiu, H.C. Tumortropic Monocyte-Mediated Delivery of Echogenic Polymer Bubbles and Therapeutic Vesicles for Chemotherapy of Tumor Hypoxia. Biomaterials 2015, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Feng, W.; Mao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X. Nanoengineered Sonosensitive Platelets for Synergistically Augmented Sonodynamic Tumor Therapy by Glutamine Deprivation and Cascading Thrombosis. Bioact Mater 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Saiding, Q.; Zhang, Y.; An, S.; Khan, M.M.; Ji, X.; Qiao, R.; Tao, W.; et al. Macrophage Hitchhiking Nanomedicine for Enhanced β-Elemene Delivery and Tumor Therapy. Sci Adv 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Jia, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, N.; Liu, P.; Wu, F. Repurposing Erythrocytes as a “Photoactivatable Bomb”: A General Strategy for Site-Specific Drug Release in Blood Vessels. Small 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.Z.; Li, T.F.; Ma, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.C.; Zhao, L.; Chen, X. Targeted Photodynamic Therapy of Glioblastoma Mediated by Platelets with Photo-Controlled Release Property. Biomaterials 2022, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, O.; Kumar, S.; Köster, M.; Ullah, S.; Sarker, S.; Hagemann, V.; Habib, M.; Klaassen, N.; Notter, S.; Feldmann, C.; et al. Macrophages Co-Loaded with Drug-Associated and Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles for Triggered Drug Release by Alternating Magnetic Fields. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2025, 15, 2779–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashele, S.S. Stimuli-Responsive, Cell-Mediated Drug Delivery Systems: Engineering Smart Cellular Vehicles for Precision Therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zuo, H.; Chen, B.; Wang, R.; Ahmed, A.; Hu, Y.; Ouyang, J. Doxorubicin-Loaded Platelets as a Smart Drug Delivery System: An Improved Therapy for Lymphoma. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.; Jiang, L.; Gu, Y.; Soe, Z.C.; Kim, B.K.; Gautam, M.; Poudel, K.; Pham, L.M.; Phung, C.D.; Chang, J.H.; et al. Regulatory T Cells Tailored with PH-Responsive Liposomes Shape an Immuno-Antitumor Milieu against Tumors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenroth, A.; Baazaoui, F.; Hosseinnejad, A.; Schäfer, L.; Vogg, A.; Singh, S.; Mottaghy, F.M. Neural Stem Cells as Carriers of Nucleoside-Conjugated Nanogels: A New Approach toward Cell-Mediated Delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Q.; Qian, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Spatial-Drug-Laden Protease-Activatable M1 Macrophage System Targets Lung Metastasis and Potentiates Antitumor Immunity. ACS Nano 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Leng, Y.; He, C.; Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Qu, Y.; Wu, Y. Red Blood Cells: A Potential Delivery System. J Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagiotti, S.; Paoletti, M.F.; Fraternale, A.; Rossi, L.; Magnani, M. Drug Delivery by Red Blood Cells. IUBMB Life 2011, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadi Barhaghtalab, R.; Tanimowo Aiyelabegan, H.; Maleki, H.; Mirzavi, F.; Gholizadeh Navashenaq, J.; Abdi, F.; Ghaffari, F.; Vakili-Ghartavol, R. Recent Advances with Erythrocytes as Therapeutics Carriers. Int J Pharm 2024, 665, 124658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizano, C.; Pérez, M.T.; Pinilla, M. Mouse Erythrocytes as Carriers for Coencapsulated Alcohol and Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Obtained by Electroporation - In Vivo Survival Rate in Circulation, Organ Distribution and Ethanol Degradation. Life Sci 2001, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favretto, M.E.; Cluitmans, J.C.A.; Bosman, G.J.C.G.M.; Brock, R. Human Erythrocytes as Drug Carriers: Loading Efficiency and Side Effects of Hypotonic Dialysis, Chlorpromazine Treatment and Fusion with Liposomes. Journal of Controlled Release 2013, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chung, H.S.; Kwon, Y.M.; Shin, M.C.; Lee, K.; Yang, V.C. Cell-Penetrating Peptides Meditated Encapsulation of Protein Therapeutics into Intact Red Blood Cells and Its Application. Journal of Controlled Release 2014, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, M.K.; Leuzzi, V.; Gouider, R.; Yiu, E.M.; Pietrucha, B.; Stray-Pedersen, A.; Perlman, S.L.; Wu, S.; Burgers, T.; Borgohain, R.; et al. Long-Term Safety of Dexamethasone Sodium Phosphate Encapsulated in Autologous Erythrocytes in Pediatric Patients with Ataxia Telangiectasia. Front Neurol 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, A.; Szczygieł, A.; Szermer-Olearnik, B.; Pajtasz-Piasecka, E. Macrophages as Promising Carriers for Nanoparticle Delivery in Anticancer Therapy. Int J Nanomedicine 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J.; Fang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Hu, J. Advances in Engineered Macrophages: A New Frontier in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Xiao, A.; Tong, A.; Xu, J. Tumor-Associated Macrophage-Related Strategies for Glioma Immunotherapy. NPJ Precis Oncol 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, N.B.; Orear, C.R.; Velazquez-Albino, A.C.; Good, H.J.; Melnyk, A.; Rinaldi-Ramos, C.M.; Shields IV, C.W. Magnetic Cellular Backpacks for Spatial Targeting, Imaging, and Immunotherapy. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Dan, Z.; He, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, H.; Yin, Q.; Li, Y. Liposomes Coated with Isolated Macrophage Membrane Can Target Lung Metastasis of Breast Cancer. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 7738–7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J. Primary M1 Macrophages as Multifunctional Carrier Combined with Plga Nanoparticle Delivering Anticancer Drug for Efficient Glioma Therapy. Drug Deliv 2018, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Hu, Q. Convergence of Nanomedicine and Neutrophils for Drug Delivery. Bioact Mater 2024, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanina, A.S.; Vishnevskiy, D.A.; Chernysheva, A.A.; Valikhov, M.P.; Malinovskaya, J.A.; Lazareva, P.A.; Semkina, A.S.; Abakumov, M.A.; Naumenko, V.A. Neutrophil as a Carrier for Cancer Nanotherapeutics: A Comparative Study of Liposome, PLGA, and Magnetic Nanoparticles Delivery to Tumors. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahnou, H.; El Kebbaj, R.; Hba, S.; Ouadghiri, Z.; El Faqer, O.; Pinon, A.; Liagre, B.; Limami, Y.; Duval, R.E. Neutrophils and Neutrophil-Based Drug Delivery Systems in Anti-Cancer Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Allickson, J. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy: Progress to Date and Future Outlook. Molecular Therapy 2025, 33, 2679–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babajani, A.; Soltani, P.; Jamshidi, E.; Farjoo, M.H.; Niknejad, H. Recent Advances on Drug-Loaded Mesenchymal Stem Cells With Anti-Neoplastic Agents for Targeted Treatment of Cancer. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, T.; Huang, T.; Gao, J. Current Advances and Challenges of Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Based Drug Delivery System and Their Improvements. Int J Pharm 2021, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Fang, J.; Chen, M.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Double-Edged Sword in Tumor Growth: Focusing on MSC-Derived Cytokines. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwon, N.; Kim, Y.J.; Siegler, E.; Chen, X.; Rohrs, J.A.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P. CAR-T Cells Surface-Engineered with Drug-Encapsulated Nanoparticles Can Ameliorate Intratumoral T-Cell Hypofunction. Cancer Immunol Res 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhang, S.; Liu, T.; Ye, S.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhu, L.; Sun, X.; et al. Improving CAR-T Cell Function through a Targeted Cytokine Delivery System Utilizing Car Target-Modified Extracellular Vesicles. Exp Hematol Oncol 2025, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Melo, M.B.; Mabardi, L.; Castaño, A.P.; Xie, Y.Q.; Li, N.; Kudchodkar, S.B.; Wong, H.C.; Jeng, E.K.; et al. Enhancing T Cell Therapy through TCR-Signaling-Responsive Nanoparticle Drug Delivery. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Stephan, M.T.; Gai, S.A.; Abraham, W.; Shearer, A.; Irvine, D.J. In Vivo Targeting of Adoptively Transferred T-Cells with Antibody- and Cytokine-Conjugated Liposomes. Journal of Controlled Release 2013, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, W.; Wei, W.; Zuo, L.; Lv, C.; Zhang, F.; Lu, G.H.; Li, F.; Wu, G.; Huang, L.L.; Xi, X.; et al. Magnetic Nanoclusters Armed with Responsive PD-1 Antibody Synergistically Improved Adoptive T-Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors. ACS Nano 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.B.; Aragon-Sanabria, V.; Randolph, L.; Jiang, H.; Reynolds, J.A.; Webb, B.S.; Madhankumar, A.; Lian, X.; Connor, J.R.; Yang, J.; et al. High-Affinity Mutant Interleukin-13 Targeted CAR T Cells Enhance Delivery of Clickable Biodegradable Fluorescent Nanoparticles to Glioblastoma. Bioact Mater 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, H.; Newmyer, S.L.; Javitz, H.S.; Bhatnagar, P. Engineered CD4 T Cells for in Vivo Delivery of Therapeutic Proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasik, J.; Jasiński, M.; Basak, G.W. Next Generations of CAR-T Cells - New Therapeutic Opportunities in Hematology? Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewski, M.; Abken, H. TRUCKs: The Fourth Generation of CARs. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2015, 15, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipson, B.I.; O’Connor, R.S.; May, M.J.; June, C.H.; Albelda, S.M.; Milone, M.C. 4-1BB Costimulation Promotes CAR T Cell Survival through Noncanonical NF-ΚB Signaling. Sci Signal 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco Cárdenas, R.M.-H.; Brandl, S.M.; Meléndez, A.V.; Schlaak, A.E.; Buschky, A.; Peters, T.; Beier, F.; Serrels, B.; Taromi, S.; Raute, K.; et al. Harnessing CD3 Diversity to Optimize CAR T Cells. Nat Immunol 2023, 24, 2135–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmamaw Dejenie, T.; Tiruneh G/Medhin, M.; Dessie Terefe, G.; Tadele Admasu, F.; Wale Tesega, W.; Chekol Abebe, E. Current Updates on Generations, Approvals, and Clinical Trials of CAR T-Cell Therapy. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraghty, A.C.; Acosta-Alvarez, L.; Rotiroti, M.C.; Dutton, S.; O’Dea, M.R.; Kim, W.; Trivedi, V.; Mancusi, R.; Shamardani, K.; Malacon, K.; et al. Immunotherapy-Related Cognitive Impairment after CAR T Cell Therapy in Mice. Cell 2025, 188, 3238–3258.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Abraham, W.D.; Zheng, Y.; Bustamante López, S.C.; Luo, S.S.; Irvine, D.J. Active Targeting of Chemotherapy to Disseminated Tumors Using Nanoparticle-Carrying T Cells. Sci Transl Med 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastantuono, S.; Manini, I.; Di Loreto, C.; Beltrami, A.P.; Vindigni, M.; Cesselli, D. Glioma-Derived Exosomes and Their Application as Drug Nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The Biology, Function, and Biomedical Applications of Exosomes. Science (1979) 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokumcu, T.; Iskar, M.; Schneider, M.; Helm, D.; Klinke, G.; Schlicker, L.; Bethke, F.; Müller, G.; Richter, K.; Poschet, G.; et al. Proteomic, Metabolomic, and Fatty Acid Profiling of Small Extracellular Vesicles from Glioblastoma Stem-Like Cells and Their Role in Tumor Heterogeneity. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 2500–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruqu, F.N.; Liam-Or, R.; Zhou, S.; Nip, R.; Al-Jamal, K.T. Defined Serum-free Three-dimensional Culture of Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Yields Exosomes That Promote Fibroblast Proliferation and Migration in Vitro. The FASEB Journal 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Guo, C.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, J.; Li, F. Exosome-Mediated MiRNA Delivery: A Molecular Switch for Reshaping Neuropathic Pain Therapy. Front Mol Neurosci 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohak, S.; Fabian, Z. Extracellular Vesicles as Precision Delivery Systems for Biopharmaceuticals: Innovations, Challenges, and Therapeutic Potential. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigaj-Józefowska, M.J.; Grześkowiak, B.F. Polymeric Nanoparticles Wrapped in Biological Membranes for Targeted Anticancer Treatment. Eur Polym J 2022, 176, 111427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.C.; Vankayala, R.; Mac, J.T.; Anvari, B. RBC-Derived Optical Nanoparticles Remain Stable After a Freeze–Thaw Cycle. Langmuir 2020, 36, 10003–10011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Luo, Q.; Li, Y.; Lin, X.; Fan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, X. Fabrication of Red Blood Cell-Based Multimodal Theranostic Probes for Second Near-Infrared Window Fluorescence Imaging-Guided Tumor Surgery and Photodynamic Therapy. Theranostics 2019, 9, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yin, Y.; Song, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Xu, Y.; Cai, S.; Wang, K.; Yang, W.; et al. Red-Blood-Cell-Membrane-Enveloped Magnetic Nanoclusters as a Biomimetic Theranostic Nanoplatform for Bimodal Imaging-Guided Cancer Photothermal Therapy. J Mater Chem B 2020, 8, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.K.; Angsantikul, P.; Pang, Z.; Nasongkla, N.; Hussen, R.S.D.; Thamphiwatana, S.D. Biomimetic Targeted Theranostic Nanoparticles for Breast Cancer Treatment. Molecules 2022, 27, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jia, H.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Duan, Q.; Xu, K.; Shan, B.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, F. A Red Blood Cell-derived Bionic Microrobot Capable of Hierarchically Adapting to Five Critical Stages in Systemic Drug Delivery. Exploration 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, H.; Tian, H.; Yan, F. Real-Time Imaging Tracking of Engineered Macrophages as Ultrasound-Triggered Cell Bombs for Cancer Treatment. Adv Funct Mater 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Si, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C.; Tian, H. Polymerization and Coordination Synergistically Constructed Photothermal Agents for Macrophages-Mediated Tumor Targeting Diagnosis and Therapy. Biomaterials 2021, 264, 120382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Xing, G.; Dong, X.; Zhu, D.; Yang, W.; Mei, L.; Lv, F. Nanozyme-Laden Intelligent Macrophage EXPRESS Amplifying Cancer Photothermal-Starvation Therapy by Responsive Stimulation. Mater Today Bio 2022, 16, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hu, G.; Wu, X.; Nie, Y.; Wu, H.; Kong, D.; Ning, X. Multistage Targeted “Photoactive Neutrophil” for Enhancing Synergistic Photo-Chemotherapy. Biomaterials 2021, 279, 121224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ji, C.; Zhang, H.; Shi, H.; Mao, F.; Qian, H.; Xu, W.; Wang, D.; Pan, J.; Fang, X.; et al. Engineered Neutrophil-Derived Exosome-like Vesicles for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Sci Adv 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, T.; He, M.; Nie, C.; Chen, T.; Jiang, J.; Chu, X. Feature-Enhanced Artificial Neutrophils for Dual-Modal MR/NIR Imaging-Guided Cancer Therapy. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 495, 153436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Jiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Pang, X.; Xue, B.; Yao, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Teng, L. Neutrophil-Mediated Delivery Platforms for Synergistic Chemo-Immunotherapy of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Therapy. Nano Lett 2025, 25, 14229–14236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiru, L.; Zlitni, A.; Tousley, A.M.; Dalton, G.N.; Wu, W.; Lafortune, F.; Liu, A.; Cunanan, K.M.; Nejadnik, H.; Sulchek, T.; et al. In Vivo Imaging of Nanoparticle-Labeled CAR T Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, J.; Schregel, K.; Boztepe, B.; Agardy, D.A.; Turco, V.; Karimian-Jazi, K.; Weidenfeld, I.; Streibel, Y.; Fischer, M.; Sturm, V.; et al. In Vivo Nanoparticle-Based T Cell Imaging Can Predict Therapy Response towards Adoptive T Cell Therapy in Experimental Glioma. Theranostics 2023, 13, 5170–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Sandoval Castellanos, A.M.; Kim, M.; Kulkarni, A.D.; Lee, J.; Jhunjhunwala, A.; Wang, C.; Xia, Y.; Kubelick, K.P.; Emelianov, S.Y.; et al. Nanoengineered Cytotoxic T Cells for Photoacoustic Image-Guided Combinatorial Cancer Therapy. Biomed Eng Lett 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Wang, K.; Wang, M.; Liu, R.; Song, H.; Li, N.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Du, Y.; Yang, W.; et al. Bioinspired Nanoplatelets for Chemo-Photothermal Therapy of Breast Cancer Metastasis Inhibition. Biomaterials 2019, 206, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, Z.; Bao, H.; Yuan, X.; Chen, C.; Xia, D.; Wang, X. A Platelet-Powered Drug Delivery System for Enhancing Chemotherapy Efficacy for Liver Cancer Using the Trojan Horse Strategy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barar, J.; Rafi, M.A.; Pourseif, M.M.; Omidi, Y. Blood-Brain Barrier Transport Machineries and Targeted Therapy of Brain Diseases. BioImpacts 2016, 6, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freret, M.E.; Boire, A. The Anatomic Basis of Leptomeningeal Metastasis. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2024, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, O.M.; Woodall, R.C.; Gutova, M.; Brown, C.E.; Rockne, R.C.; Munson, J.M. Delivery Strategies for Cell-Based Therapies in the Brain: Overcoming Multiple Barriers. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2021, 11, 2448–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torp, S.H.; Solheim, O.; Skjulsvik, A.J. The WHO 2021 Classification of Central Nervous System Tumours: A Practical Update on What Neurosurgeons Need to Know—a Minireview. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2022, 164, 2453–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brás, J.P.; Jesus, T.T.; Prazeres, H.; Lima, J.; Soares, P.; Vinagre, J. TERTmonitor—QPCR Detection of TERTp Mutations in Glioma. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Weng, S.; Liu, Z.; Xu, H.; Ren, Y.; Guo, C.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, Y.; Han, X. CRISPR-Cas9 Identifies Growth-Related Subtypes of Glioblastoma with Therapeutical Significance through Cell Line Knockdown. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADEGBOYEGA, G.; KANMOUNYE, U.S.; PETRINIC, T.; OZAIR, A.; BANDYOPADHYAY, S.; KURI, A.; ZOLO, Y.; MARKS, K.; RAMJEE, S.; BATICULON, R.E.; et al. Global Landscape of Glioblastoma Multiforme Management in the Stupp Protocol Era: Systematic Review Protocol. Int J Surg Protoc 2021, 25, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiariello, M.; Inzalaco, G.; Barone, V.; Gherardini, L. Overcoming Challenges in Glioblastoma Treatment: Targeting Infiltrating Cancer Cells and Harnessing the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Cell Neurosci 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Millán, C.; Colino Gandarillas, C.I.; Sayalero Marinero, M.L.; Lanao, J.M. Cell-Based Drug-Delivery Platforms. Ther Deliv 2012, 3, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-K.; Tsai, C.-L.; Mir, A.; Hynynen, K. MRI-Guided Focused Ultrasound for Treating Parkinson’s Disease with Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, S.-P. ; Abd. Rahim, E.N.A.; Nor Arfuzir, N.N. Neuroprotective Effects of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells (Neuroncell-EX) in a Rat Model of Ischemic Stroke Are Mediated by Immunomodulation, Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity, Angiogenesis, and Neurogenesis. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2025, 61, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Shiraishi, K.; Kushida, Y.; Oguma, Y.; Wakao, S.; Dezawa, M.; Kuroda, S. Nose-to-Brain Delivery of Human Muse Cells Enhances Structural and Functional Recovery in the Murine Ischemic Stroke Model. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 16243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yueh, P.-F.; Chiang, I.-T.; Weng, Y.-S.; Liu, Y.-C.; Wong, R.C.B.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hsu, J.B.-K.; Jeng, L.-B.; Shyu, W.-C.; Hsu, F.-T. Innovative Dual-Gene Delivery Platform Using MiR-124 and PD-1 via Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Exosome for Glioblastoma Therapy. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2025, 44, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-H.; Su, C.-Y.; Cheng, H.-W.; Chu, C.-Y.; Jeng, L.-B.; Chiang, C.-S.; Shyu, W.-C.; Chen, S.-Y. Stem Cell–Nanomedicine System as a Theranostic Bio-Gadolinium Agent for Targeted Neutron Capture Cancer Therapy. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Wei, T.; Zhang, T.; Niu, C. Adipose-derived Stem Cell-mediated Alphastatin Targeting Delivery System Inhibits Angiogenesis and Tumor Growth in Glioma. Mol Med Rep 2023, 28, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Sun, S.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Yin, R.; Chen, Y.; Chang, J.; Ye, L.; Gao, J.; Zhao, X.; et al. Intranasal Delivery of Engineered Extracellular Vesicles Promotes Neurofunctional Recovery in Traumatic Brain Injury. J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; A, M.; Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Abulimiti, M.; Maimaitiaili, N.; Qin, H. Intrathecal Transplantation of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhances Spinal Cord Injury Recovery: Role of MiR-124-3p as a Biomarker. Exp Ther Med 2025, 29, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, D.; Jia, J.; Hao, C.; Ge, Q.; Xu, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Mi, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Neuroprotection of Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (HUC-MSCs) in Alleviating Ischemic Stroke-Induced Brain Injury by Regulating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Neurochem Res 2024, 49, 2871–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargarani, S.; Tavaf, M.J.; Soltanmohammadi, A.; Yazdanpanah, E.; Baharlou, R.; Yousefi, B.; Sadighimoghaddam, B.; Esmaeili, S.; Haghmorad, D. Adipose-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis via Modulation of Th1/Th17 and Expansion of Th2/Treg Responses. Cell Biol Int 2024, 48, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaya, N.; Kitamura, Y.; Lopez Vazquez, M.; Franco, A.; Chen, K.-S.; van Schaik, T.A.; Farzani, T.A.; Borges, P.; Ichinose, T.; Seddiq, W.; et al. Gene-Edited and -Engineered Stem Cell Platform Drives Immunotherapy for Brain Metastatic Melanomas. Sci Transl Med 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogiatzi, I.; Lama, L.M.; Lehmann, A.; Rossignoli, F.; Gettemans, J.; Shah, K. Allogeneic Stem Cells Engineered to Release Interferon β and ScFv-PD1 Target Glioblastoma and Alter the Tumor Microenvironment. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, M.; Shi, B. Glioblastoma Cell Derived Exosomes as a Potent Vaccine Platform Targeting Primary Brain Cancers and Brain Metastases. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 17309–17322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alptekin, A.; Khan, M.B.; Parvin, M.; Chowdhury, H.; Kashif, S.; Selina, F.A.; Bushra, A.; Kelleher, J.; Ghosh, S.; Williams, D.; et al. Effects of Low-Intensity Pulsed Focal Ultrasound-Mediated Delivery of Endothelial Progenitor-Derived Exosomes in TMCAo Stroke. Front Neurol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Sun, B.; Nan, C.; Cong, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, L. Effects of 3D-Printed Exosome-Functionalized Brain Acellular Matrix Hydrogel on Neuroinflammation in Rats Following Cerebral Hemorrhage. Stem Cell Res Ther 2025, 16, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Deng, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Gong, J. Exosome-Mediated Dual Drug Delivery of Curcumin and Methylene Blue for Enhanced Cognitive Function and Mechanistic Elucidation in Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.L.; Tang, Y.P.; Qu, Y.Q.; Yun, Y.X.; Zhang, R.L.; Wang, C.R.; Wong, V.K.W.; Wang, H.M.; Liu, M.H.; Qu, L.Q.; et al. Exosomal Delivery of Rapamycin Modulates Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration and VEGF Axis in Glioblastoma. Journal of Controlled Release 2025, 381, 113605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.; Sun, Y.; Tang, X.; Duan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, H.; Xu, L.; Zhang, P.; Sun, K.; Yang, G.; et al. The Tumor-Derived Exosomes Enhanced Bevacizumab across the Blood–Brain Barrier for Antiangiogenesis Therapy against Glioblastoma. Mol Pharm 2025, 22, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-J.; Jang, S.H.; Lim, J.; Park, H.; Ahn, S.-H.; Park, S.Y.; Seo, H.; Song, S.-J.; Shin, J.-A.; Choi, C.; et al. Exosome-Based Targeted Delivery of NF-ΚB Ameliorates Age-Related Neuroinflammation in the Aged Mouse Brain. Exp Mol Med 2025, 57, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Duan, H.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, Z.; Yin, L.; Li, M.; et al. Heat Acclimation Defense against Exertional Heat Stroke by Improving the Function of Preoptic TRPV1 Neurons. Theranostics 2025, 15, 1376–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, S.; Kawabori, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Nakahara, Y.; Yoshie, E.; Konno, K.; Mizuno, Y.; Fujioka, Y.; Ohba, Y.; Kuge, Y.; et al. Intranasal Administration of Stem Cell-Derived Exosome Alleviates Cognitive Impairment against Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Exp Neurol 2025, 386, 115143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Li, A.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhuang, W.; Ma, X.; Qiao, Z.; Xiu, X.; Lang, X.; et al. Intranasal Delivery of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Int Immunopharmacol 2025, 146, 113853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Sha, S.; Shan, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, L.; Xing, C.; Guo, Z.; Du, H. Intranasal Delivery of BACE1 SiRNA and Berberine via Engineered Stem Cell Exosomes for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Nanomedicine 2025, Volume 20, 5873–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanova, D.Y.; Bobkova, N. V.; Chaplygina, A. V.; Svirshchevskaya, E. V.; Poltavtseva, R.A.; Vodennikova, A.A.; Chernyshev, V.S.; Sukhikh, G.T. Effect of Small Extracellular Vesicles Produced by Mesenchymal Stem Cells on 5xFAD Mice Hippocampal Cultures. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, F.; Han, Z.; Yan, B.; Liao, P.; Yin, Z.; Ge, X.; Li, D.; Zhong, R.; Liu, Q.; et al. Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Neural Stem Cell Exosomes Improve Blood–Brain Barrier Function after Intracerebral Hemorrhage by Activating Astrocytes via PI3K/AKT/MCP-1 Axis. Neural Regen Res 2025, 20, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhou, K.; Wang, C.; Du, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhang, H.; Hui, X. Exosomal <scp>miR</Scp> -142-3p from <scp>M1</Scp> -polarized Macrophages Suppresses Cell Growth and Immune Escape in Glioblastoma through Regulating <scp>HMGB1</Scp> -mediated <scp>PD</Scp> -1/ <scp>PD</Scp> - <scp>L1</Scp> Checkpoint. J Neurochem 2025, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, K.-B.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, J.-C.; Hu, D.-X.; Luo, J. Sinomenine Alleviates Neuroinflammation in Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion by Promoting M2 Microglial Polarization and Inhibiting Neuronal Pyroptosis via Exosomal MiRNA-223-3p. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2025, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, G.; Li, Z.; Gu, L.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Geng, R.; Chen, Y.; Ma, W.; Bao, X.; et al. Endoscopic Nasal Delivery of Engineered Endothelial Progenitor Cell-Derived Exosomes Improves Angiogenesis and Neurological Deficits in Rats with Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Mater Today Bio 2025, 32, 101652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, Q.; Chai, Y.; Rong, R.; He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. An Anti-CD19-Exosome Delivery System Navigates the Blood–Brain Barrier for Targeting of Central Nervous System Lymphoma. J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.V.; Ma, Y.H.E.; Plant, C.D.; Harvey, A.R.; Plant, G.W. Combined Transplantation of Mesenchymal Progenitor and Neural Stem Cells to Repair Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. Cells 2025, 14, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Long, Z.; Qin, Z.; Ran, H.; Wu, S.; Gong, M.; Li, J. A Detailed Evaluation of the Advantages among Extracellular Vesicles from Three Cell Origins for Targeting Delivery of Celastrol and Treatment of Glioblastoma. Int J Pharm 2024, 667, 125005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.-J.; Wei, H.; Cai, L.-L.; Xu, Y.-H.; Du, R.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, X.-L.; Li, Y.-F. Magnetic Targeting Enhances the Neuroprotective Function of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Iron Oxide Exosomes by Delivering MiR-1228-5p. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmasoumi, P.; Abdouss, M.; Farhadi, M.; Jameie, S.B.; Khonakdar, H.A. Co-Delivery of Temozolomide and Quercetin with Folic Acid-Conjugated Exosomes in Glioblastoma Treatment. Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 2271–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, E.A.; Gregory, H.N.; Carter, L.N.; Evans, R.E.; Roberton, V.H.; Dickman, R.; Phillips, J.B. An Immunomodulatory Encapsulation System to Deliver Human IPSC-Derived Dopaminergic Neuron Progenitors for Parkinson’s Disease Treatment. Biomater Sci 2025, 13, 2012–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.L.; Valdivia, A.; Hingtgen, S.D.; Benhabbour, S.R. Injectable Tumoricidal Neural Stem Cell-Laden Hydrogel for Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme—An In Vivo Safety, Persistence, and Efficacy Study. Pharmaceutics 2024, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, L.; Thang, M.; Zhang, Y.; DeVane, C.; Logan, J.; Tessema, A.; Perry, J.; Hingtgen, S. Development of a Biocompatible 3D Hydrogel Scaffold Using Continuous Liquid Interface Production for the Delivery of Cell Therapies to Treat Recurrent Glioblastoma. Bioeng Transl Med 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.E.; Lee, W.-J.; Park, K.-S.; Yu, Y.; Kim, G.; Roh, E.J.; Song, B.G.; Jung, J.-H.; Cho, K.; Ha, Y.; et al. Repeated Intrathecal Injections of Peripheral Nerve-Derived Stem Cell Spheroids Improve Outcomes in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Stem Cell Res Ther 2024, 15, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodell, A.S.; Landoni, E.; Valdivia, A.; Buckley, A.; Ogunnaike, E.A.; Dotti, G.; Hingtgen, S.D. Utilizing Induced Neural Stem Cell-based Delivery of a Cytokine Cocktail to Enhance Chimeric Antigen Receptor-modified T-cell Therapy for Brain Cancer. Bioeng Transl Med 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Xu, Q.; Chai, Z.; Wu, S.; Xu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Luo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xie, C.; et al. All-Stage Targeted Red Blood Cell Membrane-Coated Docetaxel Nanocrystals for Glioma Treatment. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 369, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Yan, C.; Yin, S.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; Xue, A.; Lei, X.; Zhang, N.; Geng, F. Erythrocyte Membrane-Coated Nanocarriers Modified by TGN for Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 366, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moezzi, S.M.I.; Javadi, P.; Mozafari, N.; Ashrafi, H.; Azadi, A. Metformin-Loaded Nanoerythrosomes: An Erythrocyte-Based Drug Delivery System as a Therapeutic Tool for Glioma. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, X. Erythrocyte Membrane-Enveloped Salvianolic Acid B Nanoparticles Attenuate Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Int J Nanomedicine 2022, Volume 17, 3561–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucarini, G.; Sbaraglia, F.; Vizzoca, A.; Cinti, C.; Ricotti, L.; Menciassi, A. Design of an Innovative Platform for the Treatment of Cerebral Tumors by Means of Erythro-Magneto-HA-Virosomes. Biomed Phys Eng Express 2020, 6, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Chao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, G. Injectable Oxidized High-Amylose Starch Hydrogel Scaffold for Macrophage-Mediated Glioblastoma Therapy. Biomaterials 2025, 318, 123128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Bialasek, M.; Mayoux, M.; Lin, M.-S.; Buck, A.; Marszałek, I.; Taciak, B.; Bühler, M.; Górczak, M.; Kucharzewska, P.; et al. Adoptive Cell Therapy with Macrophage-Drug Conjugates Facilitates Cytotoxic Drug Transfer and Immune Activation in Glioblastoma Models. Sci Transl Med 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yin, H.; Zhao, J.; Yao, B.; Cheng, G.; Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.; et al. Adoptive Macrophages Suppress Glioblastoma Growth by Reversing Immunosuppressive Microenvironment through Programmed Phenotype Repolarization. Cell Rep 2025, 44, 116350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, C.; Madsen, S.J.; Peng, Q.; Hirschberg, H. Macrophages as a Photosensitizer Delivery System for Photodynamic Therapy: Potential for the Local Treatment of Resected Glioblastoma. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2024, 45, 103897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Dai, L.; Yu, J.; Cao, H.; Bao, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhou, L.; Yang, J.; Sofia, A.; Chen, H.; et al. Tumor Microenvironment Targeting System for Glioma Treatment via Fusion Cell Membrane Coating Nanotechnology. Biomaterials 2023, 295, 122026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; You, C.; Zhao, D. Long Non-Coding RNA UCA1/MiR-182/PFKFB2 Axis Modulates Glioblastoma-Associated Stromal Cells-Mediated Glycolysis and Invasion of Glioma Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 500, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Liu, Y.; Tian, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. Efficient Photosensitizer Delivery by Neutrophils for Targeted Photodynamic Therapy of Glioblastoma. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, C.; Lee, J.; Kim, G.E.; Choe, Y.H.; Lee, H.; Hyun, Y.-M. Targeted Delivery of Nanoparticle-Conveyed Neutrophils to the Glioblastoma Site for Efficient Therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 41819–41827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]