1. Introduction

Spasticity is a motor disorder that arises after central nervous system lesions and is manifested as a velocity-dependent increase in resistance to passive stretch, associated with positive signs such as clonus, spasms, and exaggerated reflexes, and negative features such as weakness and loss of selective motor control. Lance’s classical definition has been widely used in clinical practice; however, more recent approaches expand its scope. Dressler et al. proposed redefining spasticity within the broader concept of involuntary muscle overactivity associated with upper motor neuron lesions, particularly in the context of botulinum toxin therapy [

1]. Similarly, Mukherjee and Chakravarty emphasized that spasticity results from complex pathophysiological mechanisms that clinicians must consider in daily practice [

2].

Spasticity is common across neurological conditions. After stroke, systematic reviews estimate a prevalence of approximately 25% overall, with higher rates in specific cohorts [

3]. It is also highly prevalent in spinal cord injury and cerebral palsy, where spastic forms comprise nearly 80% of cases [

4]. Spasticity contributes to pain, contractures, mobility limitations, and reduced quality of life, creating a substantial socioeconomic burden. Recent reviews have also highlighted the importance of improving quantitative assessment methods to better characterize and monitor spasticity, which may guide treatment selection and research in novel interventions [

5].

Management requires a multimodal approach. Botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) remains the cornerstone for focal spasticity, with demonstrated efficacy across etiologies and muscle groups [

4]. Complementary interventional strategies are increasingly used in complex or refractory cases. Phenol neurolysis has long been applied in focal patterns, with contemporary surveys and cohort studies describing its practice patterns and feasibility under ultrasound and electrostimulation guidance [

6,

7]. Diagnostic nerve blocks (DNBs) with local anesthetics are gaining recognition as valuable tools to distinguish neural overactivity from fixed contracture and to optimize BoNT-A treatment goals [

8].

In recent years, minimally invasive ablative procedures have been explored. Cryoneurotomy and cryoneurolysis represent emerging options capable of inducing reversible axonotmesis with documented reductions in tone and functional gains in post-stroke and long-standing spasticity [

9,

10]. Similarly, ultrasound-guided radiofrequency thermal neuroablation has been reported as a promising technique for refractory adductor and rectus femoris spasticity [

11], and its application to the musculocutaneous nerve has also been reported as a safe and effective option for patients with severe spasticity presenting an elbow flexor pattern [

12]. For pain management, particularly in hemiplegic shoulder pain, intra-articular BoNT-A injections have shown positive results in reducing pain and improving mobility [

13].

Recently non-invasive adjunctive therapies have gained growing relevance in the management of spasticity, among which Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT) has emerged as a promising option. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 42 studies and 1,973 patients concluded that ESWT significantly reduces Modified Ashworth Scale scores in individuals with upper motor neuron lesions, although the methodological quality of available trials remains limited and heterogeneity is high [

14]. Likewise, a more recent systematic review focused on adults with stroke and cerebral palsy—encompassing 16 studies—found that ESWT effectively reduced spasticity in both upper and lower limbs, with effects maintained up to 12 weeks after treatment [

15]. However, controversy persists regarding the magnitude of effect, the most effective wave type (radial vs. focal), optimal stimulation parameters, and duration of benefits, underscoring the need for larger, high-quality randomized controlled trials to establish standardized protocols and long-term efficacy.

Beyond technical advances, patient participation in the rehabilitation process has become a central paradigm. A systematic review by Rose et al. demonstrated that shared decision-making during rehabilitation goal-setting enhances patient satisfaction and engagement [

16]. More recently, longitudinal evidence confirmed that active patient involvement in rehabilitation processes is associated with better functional outcomes and higher goal attainment [

17]. Such findings support integrating shared decision-making into spasticity management, ensuring that treatment strategies are not only clinically effective but also aligned with patients’ priorities.

Finally, in the European context consensus initiatives have emphasized the need for patient-centered criteria in selecting advanced therapies such as intrathecal baclofen or BoNT-A, underscoring that therapeutic strategies should consider both clinical suitability and patient preferences [

4].

2. Objectives

In this framework, the primary aim of this study was to define consensus-driven, patient-centered priorities for improving spasticity care in Spain by integrating the perspectives of individuals living with spasticity and rehabilitation professionals. This participatory approach sought to identify convergences and divergences in their experiences, transform these insights into actionable innovation strategies, and generate feasible recommendations for clinical and organizational practice.

The specific objectives were as follows:

1. Alignment analysis between patients and professionals.

To systematically map experiences and needs through parallel surveys administered to patients and professionals, and to compare convergence and divergence across key domains, including access to services, adequacy of clinical information, botulinum toxin (BoNT) treatment pathways (including perceived waning effects), preferred communication channels, and hybrid (in-person/remote) follow-up models.

2. Prioritization and feasibility of innovation.

To translate survey-derived signals into potential service innovations and evaluate them through a Real-Time Delphi process involving a group of professionals, thereby prioritizing improvement actions, rating their implementation feasibility, and identifying barriers.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design and Context

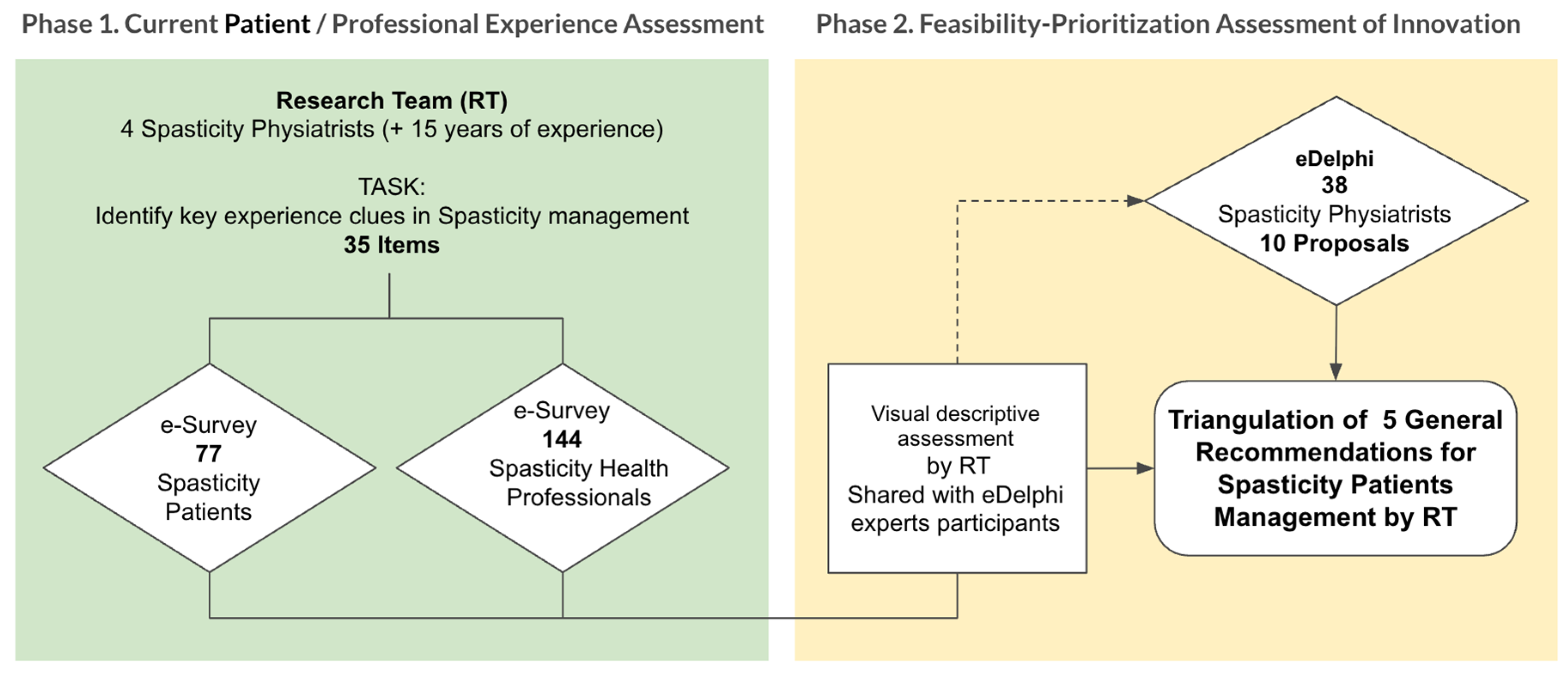

This was a sequential, mixed-methods observational consensus study conducted in two complementary phases designed to explore and align patient and professional perspectives on spasticity care.

Phase 1 involved parallel cross-sectional surveys administered to two target groups:

(1) adults living with spasticity, and (2) rehabilitation professionals (physicians, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists) with expertise in spasticity management.

The aim was to systematically map their experiences, perceptions, and unmet needs throughout the rehabilitation process.

Phase 2 consisted of a Real-Time Delphi process conducted to prioritize the recommendations emerging from Phase 1 and to assess their feasibility for implementation in clinical practice. This participatory stage enabled consensus building between patients and professionals, focusing on actionable innovations in care delivery.

Fieldwork for Phase 1 was carried out between January and May 2023, while the Real-Time Delphi session took place in May 2024.

Recruitment of rehabilitation physicians was conducted nationwide through the Spanish Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (SERMEF), ensuring broad geographical representation across Spain.

Patients were recruited through their treating rehabilitation physicians in hospitals throughout the national territory, including individuals receiving ongoing treatment for spasticity.

Figure 1 illustrates the overall study workflow—from survey distribution to the generation and prioritization of recommendations—as well as the analytic framework applied to integrate patient and professional perspectives.

3.2. Participants and Inclusion Criteria

General Inclusion Criteria

Patients. Adults (≥18 years old) with a confirmed diagnosis of spasticity of any etiology—including stroke, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, or cerebral palsy—were eligible for participation, provided they had prior exposure to rehabilitation care and consented voluntarily to take part in the study.

Professionals. Participants included rehabilitation physicians, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists with active clinical involvement in the assessment and management of spasticity within hospital or specialized outpatient settings. National recruitment was coordinated through the Spanish Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (SERMEF) to ensure wide geographical representation across Spain.

Data Collected

Demographic and profile variables were recorded for both groups to contextualize their responses.

For patients, data included age, sex, underlying etiology of spasticity, functional impact, and rehabilitation trajectory (time since diagnosis, treatment follow-up, and exposure to botulinum toxin therapy (

Table 1).

For professionals, data included sex, years of clinical experience treating spasticity, type of healthcare institution, and involvement in academic or research activities (

Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating patients (N = 77).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating patients (N = 77).

| Variable |

Distribution |

| Gender |

Male: 57.1% (n = 44) Female: 42.9% (n = 33) |

| Education |

Secondary/Vocational: 45.5% University: 31.2% Primary: 19.5% No formal education: 3.9% |

| Living situation |

Independent at home (51.9%) · Family caregiver (36.4%) · Professional caregiver (3.9%) · Supervised housing (3.9%) · Nursing home (3.9%) |

| Etiology of spasticity |

Ischemic stroke: 27.3% Hemorrhagic stroke: 15.6% Cerebral palsy: 11.7% Multiple sclerosis: 10.4% Spinal cord injury: 10.4% Traumatic brain injury: 7.8% Other: 16.9% |

| Time from symptom onset to diagnosis |

<1 year: 32.5% 1–5 years: 33.8% 6–10 years: 11.7% >10 years: 22.1% |

| Time from diagnosis to botulinum toxin treatment |

<1 month: 11.7% 1–3 months: 18.2% 4–6 months: 20.8% >6 months: 49.4% |

| Treatments received |

Botulinum toxin: 85.9% Physiotherapy: 57.8% Occupational therapy: 31.2% Orthoses: 28.1% Oral medication: 20.3% Nerve blocks: 12.5% |

| Employment impact |

Previously employed: 62.3% Currently employed: 22.1% Work disability recognized: 57.1% (of which 54.5% due to spasticity) |

| Comorbidities |

Chronic disease in addition to spasticity: 46.8% |

| Housing adaptation |

Adapted: 57.1% Not adapted: 42.9% |

Table 2.

Characteristics of participating professionals (N = 141).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participating professionals (N = 141).

| Variable |

Distribution |

| Gender |

Female: 77.3% (n = 109) Male: 22.7% (n = 32) |

| Professional category |

PM&R physicians: 86.5% Physiotherapists: 8.5% Occupational therapists: 5% |

| Workplace |

Referral hospital: 61% Area/Secondary hospital (~400 beds): 25.5% Basic general hospital (~200 beds): 5% District hospital (~100 beds): 5.7% Other: 2.8% |

| Experience in spasticity |

<5 years: 17.7% 6–10 years: 24.1% 11–15 years: 18.4% 15–20 years: 22% >20 years: 17.7% |

| Experience in interventional management of spasticity |

<5 years: 26.2% 6–10 years: 28.4% 11–15 years: 17.7% 15–20 years: 16.3% >20 years: 11.3% |

| Treatments used |

Physiotherapy 95% · Botulinum toxin 90.1% · Orthoses 87.9% · Occupational therapy 67.4% · Oral medication 61% · Nerve blocks 37.6% · Intrathecal baclofen pump 24.1% · Shock wave therapy 19.9% · Radiofrequency 7.8% |

| Scientific activity |

No publications: 41.8% <5 publications: 41.1% 5–30 publications: 12.8% >30 publications: 4.3% |

| University teaching |

Yes: 31.2% No: 68.8% |

3.3. Questionnaires

Two parallel online questionnaires (patients/professionals) were specifically designed for this study, each structured into three sections (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3):

Profile and characterization variables: – 10 items for patients and 7 items for professionals describing demographic and clinical background (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

Common items: – 18 questions addressing shared domains such as access to rehabilitation services, adequacy of clinical information, involvement of the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team, use of hybrid or tele-rehabilitation models, and preferred communication channels (

Table 3).

Condition-specific items: – 17 questions focused on spasticity care, including botulinum toxin (BoNT) treatment itineraries (perceived utility, waning effects, adverse events) and the functional and social impact of spasticity.

All items were rated using a six-point Likert scale (1 = very little/poor; 6 = very much/excellent). The inclusion of a common core of 18 items enabled direct comparison between patients and professionals, whereas the condition-specific modules provided a deeper understanding of spasticity-related issues and treatment perceptions.

Table 3.

Differences in perception between patients and professionals.

Table 3.

Differences in perception between patients and professionals.

| |

|

Patients |

Professionals |

|

|

| ID |

|

μ |

σ |

A |

μ |

σ |

A |

SDI |

d |

| Q 6 |

Ability to use the Internet |

4,4 |

1,82 |

58,5 |

3,3 |

0,94 |

10,6 |

0,76 |

3,43 |

| Q 4 |

Adherence to therapy programs |

4,4 |

1,42 |

57,2 |

3,6 |

0,93 |

16,3 |

0,67 |

1,68 |

| Q 18 |

Resolution of doubts through remote consultation |

2,9 |

1,48 |

11,7 |

3,7 |

1,13 |

29 |

0,61 |

0,90 |

| Q 15 |

Usefulness of requesting remote consultations |

3,4 |

1,66 |

26 |

4,3 |

1,33 |

51,8 |

0,60 |

0,59 |

| Q 14 |

Motivation to do virtual group therapy |

3,2 |

1,68 |

23,4 |

4,2 |

1,20 |

42,5 |

0,69 |

0,56 |

| Q 19 |

Effect of spasticity on social life |

4,5 |

1,22 |

55,9 |

5,4 |

0,73 |

88,6 |

0,89 |

0,52 |

| Q 3 |

Agreement on therapy goals |

4,1 |

1,64 |

44,2 |

5 |

0,88 |

74,5 |

0,69 |

0,47 |

| Q 17 |

Need for tutorials before remote consultation |

3,4 |

1,72 |

31,2 |

4,4 |

1,32 |

53,2 |

0,65 |

0,46 |

| Q 16 |

Remote follow-up can replace in-person ones |

2,6 |

1,59 |

15,6 |

3,5 |

1,40 |

26,9 |

0,60 |

0,44 |

| Q 20 |

Effect of spasticity on quality of life |

4,9 |

1,05 |

66,3 |

5,6 |

0,65 |

91,5 |

0,81 |

0,31 |

| Q 22 |

Effect of spasticity on pain |

3,7 |

1,81 |

41,6 |

4,7 |

0,92 |

58,9 |

0,70 |

0,29 |

| Q 10 |

Telephone consultation sufficient |

3,2 |

1,55 |

18,2 |

2,9 |

1,16 |

8,5 |

0,22 |

0,25 |

| Q 13 |

Sharing experiences with other patients (virtually) |

3,6 |

1,76 |

33,8 |

4,4 |

1,05 |

48,2 |

0,55 |

0,24 |

| Q 28 |

Pain when BoNT injection |

2,8 |

1,64 |

18,2 |

3,3 |

1,11 |

11,3 |

0,36 |

0,22 |

| Q 27 |

BoNT usefulness: reducing pain |

4,3 |

1,71 |

53,3 |

4,9 |

0,83 |

78,7 |

0,45 |

0,21 |

| Q 12 |

Mixed program (in-person + remote) covers needs |

4,1 |

1,65 |

44,2 |

4,7 |

1,08 |

58,8 |

0,43 |

0,14 |

| Q 33 |

Satisfaction with rehabilitation physician |

5,2 |

1,30 |

81,8 |

4,7 |

0,81 |

63,1 |

0,46 |

0,14 |

| Q 21 |

Effect of spasticity on mobility |

4,6 |

1,41 |

58,5 |

5 |

0,76 |

77,3 |

0,35 |

0,11 |

| Q 2 |

In-person rehabilitation reviews meet expectations |

4,8 |

1,36 |

67,6 |

4,5 |

0,80 |

51,1 |

0,27 |

0,09 |

| Q 8 |

Usefulness of distance communication with team |

4,2 |

1,65 |

45,5 |

4 |

1,12 |

32,6 |

0,14 |

0,06 |

| Q 5 |

Usefulness of home therapy programs |

4,2 |

1,54 |

46,8 |

4,6 |

1,07 |

53,9 |

0,30 |

0,05 |

| Q 1 |

Team involvement in patient care |

5 |

1,23 |

76,7 |

5,3 |

0,77 |

86,5 |

0,29 |

0,04 |

| Q 11 |

Videocall consultation sufficient |

3,5 |

1,65 |

27,3 |

3,4 |

1,22 |

17,8 |

0,07 |

0,04 |

| Q 34 |

Satisfaction with physiotherapist |

4,9 |

1,48 |

72,8 |

4,6 |

0,85 |

65,3 |

0,25 |

0,03 |

| Q 24 |

BoNT usefulness: improving spasms |

4,8 |

1,54 |

65 |

4,9 |

0,95 |

75,2 |

0,08 |

0,01 |

| Q 29 |

Loss of BoNT effect before next injection |

4,4 |

1,58 |

58,5 |

4,5 |

0,98 |

50,4 |

0,08 |

0,01 |

| Q 9 |

Need for occasional in-person follow-up |

4,4 |

1,48 |

57,2 |

4,6 |

0,95 |

61 |

0,16 |

0,01 |

| Q 7 |

Usefulness of distance health education |

3,8 |

1,61 |

39 |

4,1 |

1,14 |

40,4 |

0,22 |

0,01 |

| Q 31 |

Willingness to join clinical trials |

4,2 |

1,94 |

55,9 |

4,3 |

1,13 |

50,3 |

0,06 |

0,01 |

| Q 35 |

Satisfaction with occupational therapist |

4,3 |

1,85 |

58,5 |

4,4 |

1,13 |

55,1 |

0,07 |

0,00 |

| Q 30 |

Adverse effect due to BoNT injection |

1,8 |

1,43 |

76,6 |

2 |

0,80 |

77,3 |

0,17 |

0,00 |

| Q 32 |

Ease of access to rehabilitation services |

4 |

1,91 |

49,4 |

4,2 |

1,08 |

49,7 |

0,13 |

0,00 |

| Q 23 |

Global usefulness of rehabilitation treatment |

5,3 |

1,10 |

83,1 |

5,2 |

0,84 |

83,7 |

0,10 |

0,00 |

| Q 25 |

BoNT usefulness: improving mobility |

4,6 |

1,62 |

65 |

4,8 |

1,01 |

65,2 |

0,15 |

0,00 |

| Q 26 |

BoNT usefulness: improving joint range of motion |

4,8 |

1,44 |

67,6 |

4,8 |

0,91 |

70,2 |

0,00 |

0,00 |

3.4. Procedure

The study followed a two-phase sequential workflow, combining quantitative and consensus-building methodologies to progressively refine priorities and generate actionable recommendations.

Phase 1: Surveys.

Invitations were disseminated through professional networks of the Spanish Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (SERMEF) and national patient associations. Participants accessed the surveys through a secure online platform that ensured anonymous participation and data protection. Eligibility was verified through screening questions confirming (a) active clinical involvement in spasticity care for professionals and (b) a confirmed diagnosis of spasticity with prior exposure to rehabilitation for patients. Responses were automatically coded and aggregated for analysis, preventing any personal identification.

Phase 2: Real-Time Delphi.

Building on the areas of convergence and divergence identified in Phase 1, the research team synthesized a preliminary list of candidate recommendations addressing key domains such as:

– pre- and post-BoNT education;

– adjustment of injection intervals and “rescue” access;

– bidirectional and traceable communication pathways;

– hybrid and digitally supported follow-up models.

Professionals participated in a Real-Time Delphi session, where they rated each proposed recommendation for implementation feasibility using a six-point Likert scale (1 = very little/poor; 6 = very much/excellent). Immediate visual feedback and controlled mini-iterations within the same round were applied to enhance the stability and robustness of the consensus process.

The variables assessed in each phase are as follows:

Phase 1 (surveys).

– Primary outcome: alignment gap between patients and professionals across domains: access, information, BoNT treatment, communication and follow-up.

– Indicators: mean scores, proportion of agreement (≥5/6), and Synthetic Indicator (d) combining the standardized difference between perceptions and the agreement gap.

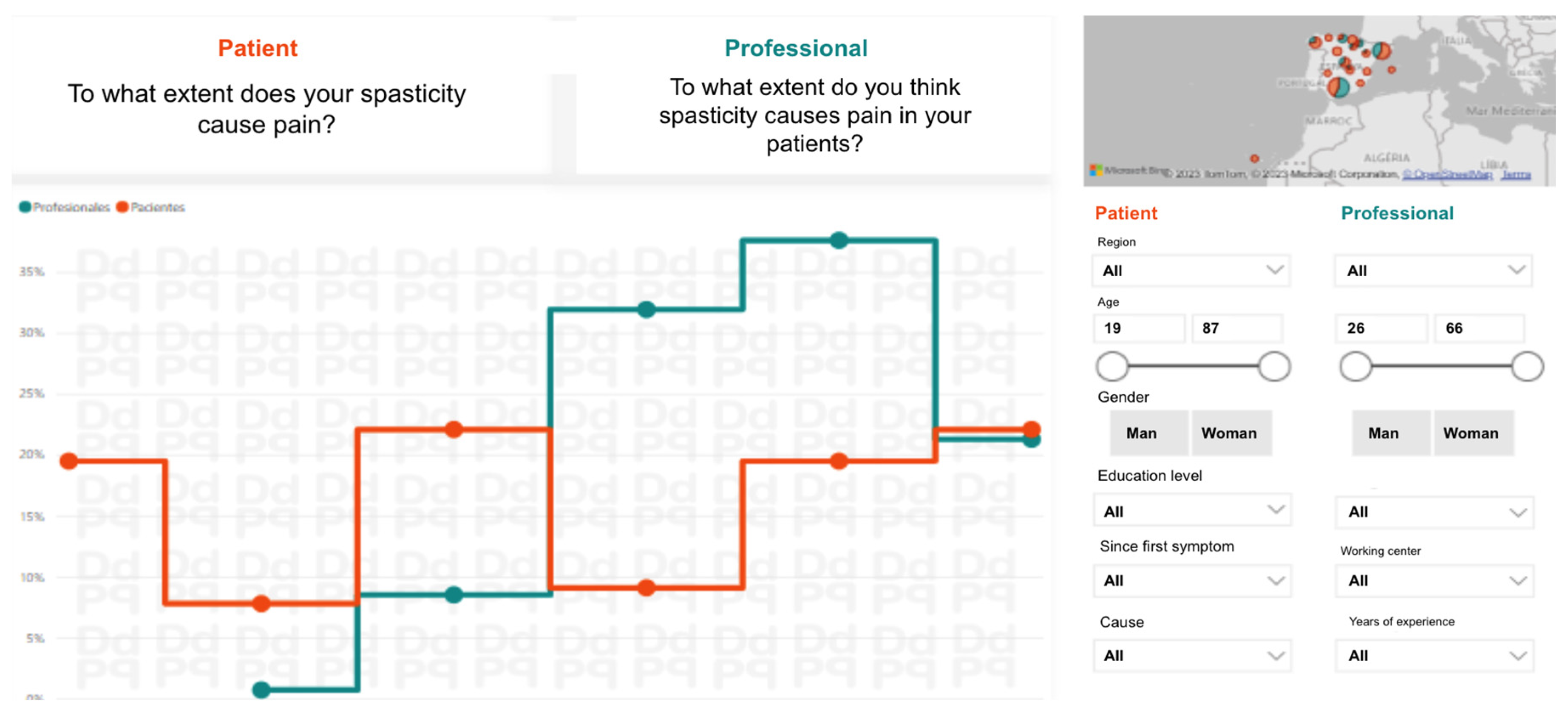

The research team prepared a visual presentation of the comparative analysis of the two surveys, patients and professionals (

Figure 2), to prepare the work of experts in Phase 2.

Phase 2 (Real-Time Delphi).

- -

Indicators: mean (μ), standard deviation (σ), median (Med) and interquartile range (IQR).

- -

Operational output: prioritized list of recommendations by feasibility (μ, Med, IQR) with complementary notes for clinical implementation.

We applied descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, proportions, confidence intervals where applicable) and comparative analyses (differences in means and agreement proportions between groups). Concordance was summarized using the Synthetic Indicator(d).

For the Real-Time Delphi phase, recommendations were ordered by feasibility parameters (μ, Med, IQR).

Figure 2.

Sample screen of the visual descriptive analysis to compare the answers to the same survey questions from patients and from professionals. This visualization was shared with experts prior to the synchronous Real-Time Delphi to assess recommendations.

Figure 2.

Sample screen of the visual descriptive analysis to compare the answers to the same survey questions from patients and from professionals. This visualization was shared with experts prior to the synchronous Real-Time Delphi to assess recommendations.

4. Results

This study identified significant differences in the perceptions and experiences of spasticity rehabilitation between patients and professionals, while also achieving consensus on recommendations to improve services. Across the two phases of the process, perceptions of care quality were systematically analyzed, and proposals were prioritized according to their feasibility of implementation. These findings culminated in a final proposal organized into specific innovation domains aimed at strengthening patient-centered spasticity care.

4.1. Comparison of Experiences Between Patients and Professionals

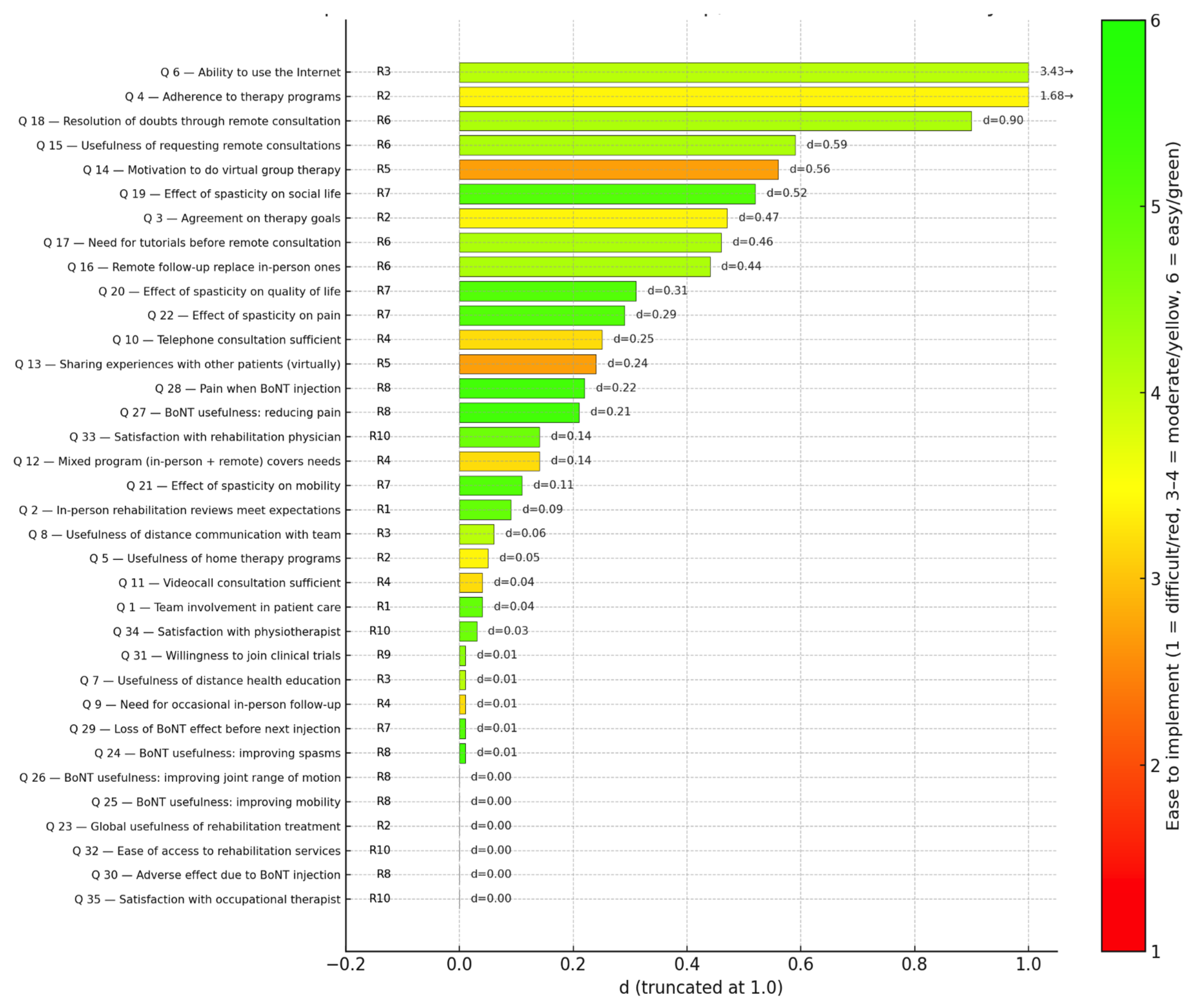

The differences in perception of the different items evaluated are shown in

Table 3. Those differences are calculated in the following manner: A synthetic indicator “d” is proposed, combining the standardized difference between perceptions (SDI) with the high-agreement gap (ΔA), thus capturing both the magnitude of the discrepancy and its consensual relevance.

SDI = | μpat - μpro | / √ [(σ2pat + σ2pro ) /2]

ΔA = | (Apat - Apro ) / Min (Apat ; Apro ) |

μpat , μpro : means for patients and professionals

σpat , σpro : standard deviations for patients and professionals

Apat , Apro : Sum of answers 5 and 6 for patients and professionals

Interpretation:

d = 0: perfect alignment: similar perceptions and comparable high agreement.

d increases as the difference in perception grows and high-agreement convergence decreases, divergence rises.

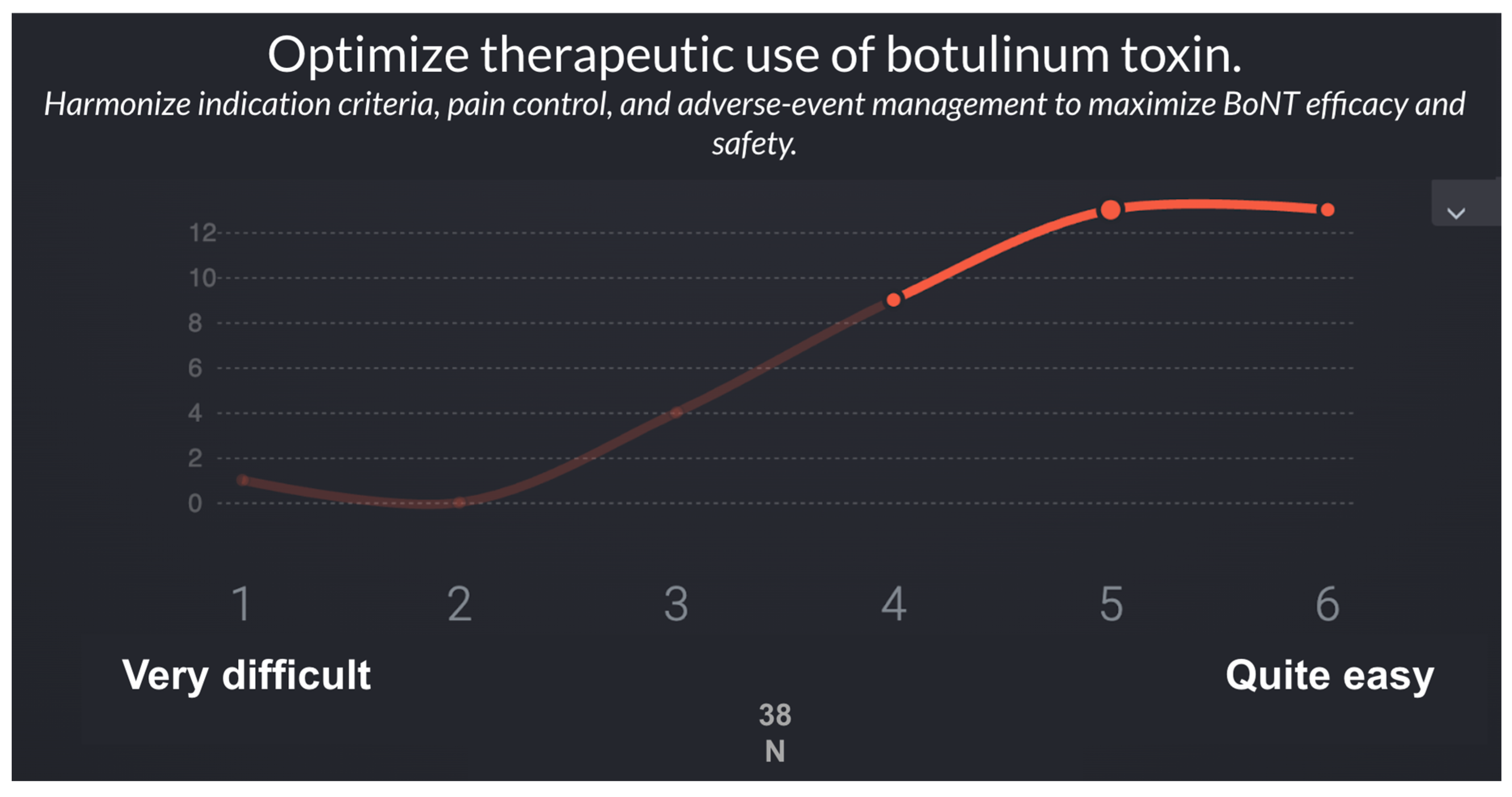

4.2. Second Phase: Validation and Prioritization of Recommendations

In the second phase, a panel of 38 specialists in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) with expertise in spasticity evaluated the feasibility of implementing the recommendations derived from Phase 1 using a Real-Time Delphi process (

Figure 3).

Table 4 and

Table 5 summarize the list of recommendations and the results of the Real-Time Delphi process.

In the second phase, the panel of 38 spasticity experts assessed the feasibility of implementing the recommendations proposed using a Real-Time Delphi application.

Table 5 presents the 10 recommendations proposed with their feasibility scoring on a 1–6 Likert scale. Recommendations are ordered from least to most difficult to implement considering the statistical variables (μ, σ, Med, IQR).

Table 5.

Real-Time Delphi prioritization of recommendations to promote patient-centered spasticity care.

Table 5.

Real-Time Delphi prioritization of recommendations to promote patient-centered spasticity care.

| N |

Question |

μ |

σ |

Med |

IQR |

| R8 |

Optimize therapeutic use of botulinum toxin |

5.3 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

| R7 |

Develop predictive models of spasticity course |

5.1 |

0.9 |

5 |

1 |

| R1 |

Strengthen interdisciplinary coordination in rehabilitation care |

4.9 |

1.2 |

5 |

1 |

| R10 |

Improve accessibility and global satisfaction with rehabilitation services |

4.8 |

1.3 |

5 |

2 |

| R9 |

Foster patient participation in research and continuous improvement |

4.5 |

1.2 |

5 |

2 |

| R6 |

Standardize remote follow-up with protocols and support tools |

4.2 |

1.1 |

4 |

2 |

| R3 |

Promote digital health literacy and safe technology use in rehab |

4.1 |

1.5 |

4 |

3 |

| R2 |

Ensure adherence and continuity of rehabilitation programs |

3.4 |

1.3 |

4 |

2 |

| R4 |

Implement hybrid follow-up models (in-person + telemedicine) |

3.2 |

1.4 |

3 |

2 |

| R5 |

Reinforce the social and motivational dimension of virtual therapy |

2.7 |

1.3 |

2 |

3 |

Figure 4.

Divergence (“d”) of survey items and ease of implementation of corresponding recommendations. Each bar represents the standardized divergence index (d) for one survey item, ordered from lowest to highest. Bar colors reflect the ease of implementation (Likert 1–6) of the linked recommendations: red = difficult, yellow = moderate, and green = easy. Codes on the left (R1–R10) indicate the corresponding recommendations, while the numerical labels to the right of each bar show the exact d values.

Figure 4.

Divergence (“d”) of survey items and ease of implementation of corresponding recommendations. Each bar represents the standardized divergence index (d) for one survey item, ordered from lowest to highest. Bar colors reflect the ease of implementation (Likert 1–6) of the linked recommendations: red = difficult, yellow = moderate, and green = easy. Codes on the left (R1–R10) indicate the corresponding recommendations, while the numerical labels to the right of each bar show the exact d values.

4.3. Final Proposal: Innovation Domains (ID) in Spasticity Rehabilitation

Building on the previous findings, the research team consolidated the ten recommendations into four strategic innovation domains that reflect both the Delphi consensus and the thematic structure of the subsequent discussion.

ID1. Access, coordination, and communication in rehabilitation care.

Strengthening interdisciplinary coordination and ensuring timely, traceable communication between patients and professionals emerged as the first priority. Standardizing referral pathways and promoting structured dialogue—supported by written and audiovisual materials—can improve transparency, continuity, and patient confidence across all stages of the rehabilitation process.

ID2. Education and sustained adherence.

Structured educational strategies for patients and caregivers are essential to promote understanding, engagement, and long-term adherence. Implementing clear therapeutic plans, self-management guides, and pre-visit tutorials for remote sessions can reinforce motivation and bridge the gap between professional prescription and patient follow-through.

ID3. Digital transition and hybrid rehabilitation.

Integrating in-person and remote care through hybrid models offers flexibility without compromising therapeutic quality. Prioritizing digital health literacy, developing safe tele-rehabilitation environments, and formalizing remote follow-up protocols will facilitate the gradual adoption of digital practices aligned with patient capabilities and preferences.

ID4. Personalization and innovation in therapeutic pathways.

Optimizing botulinum toxin (BoNT) treatment through individualized schedules, predictive models, and continuous feedback mechanisms represents a key opportunity for innovation. These advances, together with participatory approaches that value patient experience, can transform technological progress into genuine cultural change toward a more inclusive, patient-centered rehabilitation model.

These four domains form the conceptual basis for the following discussion, which examines how communication, digital transition, therapeutic optimization, and organizational culture jointly define the future of patient-centered spasticity care.

5. Discussion

This study provides evidence on the convergence and divergence between patients and rehabilitation professionals in the management of spasticity. Using a two-phase, digital Delphi-Dialogue design, it confirms the feasibility of real-time consensus methods to identify achievable innovations and patient-centered priorities in neurorehabilitation. Both groups strongly agreed on the benefits of botulinum toxin (BoNT) in reducing spasms, pain, and improving mobility, consistent with current clinical and pharmacological evidence [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, significant perceptual gaps persisted regarding access, communication, and the adoption of tele-rehabilitation, underscoring that clinical effectiveness alone is insufficient to ensure perceived quality and adherence.

Access and Communication Gaps

Nearly 40% of patients reported difficulties accessing Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) services or understanding their therapeutic plan, while most professionals considered their involvement sufficient. This mismatch mirrors the structural barriers reported internationally—limited availability of trained providers, referral variability, and uneven continuity between hospital and community phases [

20,

21]. Similar findings have been described in consensus statements of the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R) and in large real-world surveys of spasticity care [

21,

22]. Addressing these inequalities requires coordinated system-level actions: standardized referral pathways, tele-expertise between hospitals, and structured education for both professionals and patients [

18,

23,

24].

Communication and patient education emerge as central determinants of satisfaction and adherence. Educational interventions and structured dialogue have shown measurable improvement in engagement and self-management capacity [

25,

26]. Yet, despite the availability of evidence-based BoNT guidelines [

21,

27,

28], patients often report insufficient information about treatment intervals, expected outcomes, and side effects. Reinforcing bidirectional, traceable communication—through written plans, audiovisual material, and shared-decision tools—should therefore be a standard component of multidisciplinary spasticity management.

Digital and Hybrid Rehabilitation

A recurrent divergence concerned attitudes toward digital care. While professionals generally endorsed hybrid follow-up models, a notable subset of patients expressed reluctance to replace face-to-face reviews with telemedicine. Current evidence confirms that tele-rehabilitation can yield outcomes equivalent to conventional therapy when integrated within structured, hybrid pathways that maintain direct clinician oversight [

29,

30,

31]. Barriers such as digital literacy, trust, and sensory or cognitive impairments must nevertheless be anticipated. As recent guidelines emphasize, remote interventions should complement—not substitute—therapeutic contact, ensuring patient safety and personalization [

29]. The DDPP-Spasticity model, by combining online interaction with real-time expert consensus, represents a viable example of this balanced digital transition.

Therapeutic Personalization and BoNT Optimization

Both patients and professionals recognized BoNT as effective and well-tolerated, in agreement with systematic reviews and pragmatic studies [

18,

20,

22,

24,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Nonetheless, half of the patients perceived a loss of effect before the next injection, reflecting the variability of pharmacodynamics and muscle response. Evidence supports individualized injection intervals based on functional goals and spasticity severity [

28,

31]. Combined programs integrating stretching or home-based exercises after BoNT amplify and prolong therapeutic gains [

30,

32]. The use of ultrasound-guided injections and governance frameworks further enhances precision and safety [

27]. These findings highlight that optimizing BoNT treatment requires not only pharmacological precision but also continuous rehabilitation engagement and patient feedback.

From Technological Innovation to Cultural Change

Methodologically, the project reinforces the value of Real-Time Delphi systems to accelerate convergence between clinicians and patients. Compared with traditional asynchronous rounds, this format reduces attrition bias and facilitates cross-stakeholder learning, an advantage increasingly recognized in digital health research [

29,

30,

31]. Beyond technology, however, the findings emphasize that progress toward truly patient-centered spasticity care depends on cultural and organizational transformation. Health systems must incentivize the systematic capture of patient-reported experiences, integrate communication-skills training, and institutionalize shared-decision monitoring. As Topol argued, the medicine of the future will use technology to make healthcare more human—not more distant [

32].

In summary, the DDPP-Spasticity study provides a reproducible framework for aligning professional standards with patient expectations. Combining structured education, individualized BoNT schedules, and hybrid follow-up can improve adherence, trust, and perceived quality. Embedding these principles into national rehabilitation strategies could foster equitable, participatory, and outcome-oriented spasticity care.

6. Conclusions

This study underscores the need to evolve toward a more inclusive, patient-centered model of spasticity care. Combining in-person and remote strategies, together with robust educational resources, can enhance quality and accessibility. The Delphi-based recommendations provide a solid foundation for future interventions and the optimization of spasticity rehabilitation services.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Perceptions are subjective and may be influenced by recall bias or recent experiences. Differences in digital literacy and access to technology may also have affected responses about tele-rehabilitation. Finally, while recruitment was nationwide, the sample may under-represent disadvantaged populations, which could limit generalizability.

Author Contributions

Removed to maintain anonymity as per double-blind peer review protocol.

Funding

Removed to maintain anonymity as per double-blind peer review protocol.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with all applicable Spanish and European regulations on biomedical research and data protection, including the Spanish Biomedical Research Law 14/2007, the Royal Decree 1090/2015, and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, EU 2016/679) [

18,

19,

20,

21]. In accordance with Articles 2 and 3 of Law 14/2007 and Article 2 of Royal Decree 1090/2015, this research did not require evaluation by a Research Ethics Committee (CEIm) because it involved anonymized online surveys without intervention or collection of personal health data and therefore did not constitute a biomedical study involving human biological samples or therapeutic procedures.

Informed Consent Statement

Participation was voluntary for both patients and professionals. All participants received an online information sheet explaining the study objectives, procedures, and data protection safeguards, and provided informed consent before participation. Eligibility was confirmed through initial screening questions ensuring that (a) patients had a confirmed diagnosis of spasticity and prior exposure to rehabilitation, and (b) professionals had active clinical involvement in spasticity management. Survey data were collected anonymously through a secure web platform. No identifiable or sensitive information was stored, and all responses were aggregated for analysis to preserve confidentiality. During the Real-Time Delphi phase, responses remained fully anonymized, and only group-level feedback was shared to avoid any attribution of individual opinions. The study protocol was reviewed internally by the coordinating research institution and endorsed by the Spanish Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (SERMEF). Recruitment of patients and professionals was supported by national hospital networks, ensuring compliance with ethical and legal standards for non-interventional survey-based research.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Removed to maintain anonymity as per double-blind peer review protocol.

Conflicts of Interest

Removed to maintain anonymity as per double-blind peer review protocol.

References

- Dressler, D.; Bhidayasiri, R.; Bohlega, S.; Chana, P.; Chien, H.F.; Chung, T.M.; Colosimo, C.; Ebke, M.; Fedoroff, K.; Frank, B.; et al. Defining spasticity: A new approach considering current movement disorders terminology and botulinum toxin therapy. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 856–862. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Chakravarty, A. Spasticity mechanisms—for the clinician. Front. Neurol. 2010, 1, 149. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Tan, S. Prevalence and risk factors for spasticity after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 616097. [CrossRef]

- Biering-Sørensen, B.; Stevenson, V.; Bensmail, D.; Grabljevec, K.; Martínez Moreno, M.; Pucks-Faes, E.; Wissel, J.; Zampolini, M. European expert consensus on improving patient selection for the management of disabling spasticity with intrathecal baclofen and/or botulinum toxin type A. J. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 54, jrm00241. [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Luo, A.; Yu, J.; Qian, C.; Liu, D.; Hou, M.; Ma, Y. Quantitative assessment of spasticity: A narrative review of novel approaches and technologies. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1121323. [CrossRef]

- Karri, J.; Mas, M.F.; Francisco, G.E.; Li, S. Practice patterns for spasticity management with phenol neurolysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 49, 482–488. [CrossRef]

- Korupolu, R.; Malik, A.; Pemberton, E.; Stampas, A.; Li, S. Phenol neurolysis in people with spinal cord injury: A descriptive study. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2022, 8, 90. [CrossRef]

- Filippetti, M.; Tamburin, S.; Di Censo, R.; Adamo, M.; Manera, E.; Ingrà, J.; Mantovani, E.; Facciorusso, S.; Battaglia, M.; Baricich, A.; et al. Role of diagnostic nerve blocks in the goal-oriented treatment of spasticity with botulinum toxin type A: A case-control study. Toxins 2024, 16, 258. [CrossRef]

- Winston, P.; Mills, P.B.; Reebye, R.; Vincent, D. Cryoneurotomy as a percutaneous mini-invasive therapy for the treatment of the spastic limb: Case presentation, review of the literature, and proposed approach for use. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2019, 1, 100030. [CrossRef]

- David, R.; Hashemi, M.; Schatz, L.; Winston, P. Multisite treatment with percutaneous cryoneurolysis for the upper and lower limb in long-standing post-stroke spasticity. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 60, 793–797. [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, A.; Lourenço, C.; Ermida, F.N.; Costa, A.; Carvalho, J.L. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous radiofrequency thermal neuroablation for the treatment of adductor and rectus femoris spasticity. Cureus 2023, 15, e33422. [CrossRef]

- Otero-Villaverde, S.; Formigo-Couceiro, J.; Martin-Mourelle, R.; Montoto-Marques, A. Safety and Effectiveness of Thermal Radiofrequency Applied to the Musculocutaneous Nerve for Patients with Spasticity. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1369947. [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, A.; Bagnato, S.; Boccagni, C.; Romano, M.C.; Galardi, G. Efficacy of intra-articular injection of botulinum toxin type A in refractory hemiplegic shoulder pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1034–1037. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-L.; Zhang, X.-J.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy on Spasticity After Upper Motor Neuron Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, 615–623. [CrossRef]

- Otero-Luis, I.; Gómez-Santaclara, M.; Vidal-García, E.; de la Fuente-García, A. Effectiveness of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy in the Treatment of Spasticity of Different Aetiologies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1323. [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.; Rosewilliam, S.; Soundy, A. Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Sagen, J.S.; Kjeken, I.; Habberstad, A.; Linge, A.D.; Simonsen, A.E.; Lyken, A.D.; Irgens, E.L.; Framstad, H.; Lyby, P.S.; Klokkerud, M.; et al. Patient involvement in the rehabilitation process is associated with improvement in function and goal attainment: Results from an explorative longitudinal study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 320. [CrossRef]

- Levy J.; Piazza R.; Darnige L.; et al. Botulinum toxin use in patients with post-stroke spasticity: a nationwide French database study. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1245228. PMCID: PMC10482253.

- Verduzco-Gutierrez M.; Chelluri A.; Tesauro G.; et al. AAPM&R consensus guidance on spasticity assessment and management. PM&R 2024, 16(10), 1179–1192. PMID: 37962834.

- Patel A.; Alfaro S.; Verduzco-Gutierrez M.; et al. Multidisciplinary collaborative consensus statement on barriers and solutions to care access for spasticity patients. PM&R 2024, 16(10), 1179–1192. [CrossRef]

- Francisco G.E.; Balbert A.; Bavikatte G.; et al. A practical guide to optimizing the benefits of post-stroke spasticity interventions with botulinum toxin A: An international group consensus. J. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 53(1), 2715. [CrossRef]

- Falcone N.; Li S.; Liu S.Y.; et al. Long-term management of post-stroke spasticity with onabotulinumtoxinA: a real-world cohort. Toxins (Basel) 2024, 16(2), 100. PMCID: PMC11436082.

- D’Agostino T.A.; Atkinson T.M.; Latella L.E.; et al. Promoting patient participation in healthcare interactions through communication-skills training: a systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100(7), 1247–1257. [CrossRef]

- Vahdat S.; Hamzehgardeshi L.; Hessam S.; Hamzehgardeshi Z. Patient involvement in healthcare decision making: a review. Iran Red Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16(1), e12454. [CrossRef]

- Rose A.; Rosewilliam S.; Soundy A. Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: a systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Plewnia A.; Bengel J.; Körner M. Patient-centeredness and its impact on satisfaction and treatment outcomes in medical rehabilitation. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99(12), 2063–2070. [CrossRef]

- Ashford S.; Turner-Stokes L.; Picelli A.; et al. Ultrasound-image-guided injection of botulinum toxin for spasticity: scope of practice and governance framework. Adv. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 2, 100036. PMCID: PMC10757174.

- Wissel J.; Wissel B.E.; Meyer T.; et al. Early versus late botulinum toxin A injections in post-stroke spastic movement disorder: a prospective study. J. Neural Transm. 2023, 130(9), 1265–1277.

- Lee A.C.; Davenport T.E.; Randall K.; et al. Telerehabilitation in physical therapist practice: a clinical practice guideline. Phys. Ther. 2024, 104(4), pzae023. PMCID: PMC11140266.

- Federico S.; Lulaj E.; Gabrielli L.; et al. Telerehabilitation for neurological motor impairment: impact on quality of life, satisfaction, and acceptance. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12(1), 120. PMCID: PMC10779774.

- Hwang I.S.; Lin Y.T.; Lin K.C.; et al. Long-term enhancement of botulinum toxin injections for post-stroke upper-limb spasticity by structured stretching exercises. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13(12), 3327. PMID: 38922161.

- Topol, E. Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1541644632.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).