1. Introduction

Obesity is a complex, chronic disease characterized by excess adiposity that significantly increases the risk of multiple comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers [

1,

2]. The complex etiology, encompassing a dynamic interplay of genetic, neurohormonal, and environmental factors, necessitates a comprehensive and sustained management strategy [

3]. While cornerstone treatments involve dietary and physical activity interventions, programs relying

solely on these modifications often result in challenges maintaining clinically significant weight loss over extended periods [

4].

The landscape of obesity pharmacotherapy has been significantly transformed by the emergence of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), such as semaglutide [

5]. These medications, validated in landmark randomized controlled trials (RCTs) like the STEP program, exert their effect by binding to the GLP-1 receptor [

6]. This action slows gastric emptying, thereby promoting satiety, and acts centrally in the hypothalamus to reduce appetite, leading to substantial weight reduction [

6]. Building on this success, a newer class of medications, dual GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonists, exemplified by Tirzepatide, has been developed. Tirzepatide’s simultaneous activation of both the GLP-1 and GIP receptors results in a synergistic metabolic response [

7]. This potent mechanism has been shown in large RCTs, such as the SURMOUNT program, to deliver superior mean weight loss compared to first-generation GLP-1 RAs, with participants achieving over 20% weight reduction in extended follow-up [

7,

8].

The introduction of these highly effective pharmaceuticals has coincided with the rapid expansion of digital health solutions. Medicated Digital Weight Loss Services (DWLSs) offer a critical pathway to scale access to obesity care. These platforms break down common geographic and temporal barriers to continuous medical management [

9,

10], and virtual care environments have been noted to potentially foster greater comfort and openness in patient-provider communication regarding sensitive health topics [

11]. However, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) emphasizes that pharmacotherapy must be integrated with comprehensive lifestyle interventions and overseen by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) to ensure safe and effective patient-centered care [

12]. Given this, questions have been raised regarding whether all commercial DWLS models meet this required standard of continuous, integrated care.

In this context, collecting real-world data from comprehensive DWLS platforms is essential. While Ng et al. [

13] reported 16.5% mean 12-month weight loss in a real-world Tirzepatide cohort, this was achieved without integrated, continuous lifestyle coaching. Conversely, Johnson et al. [

14] found a substantial difference in 11-month mean weight loss between non-engaged (17.0%) and engaged (21.5%) patients in a comprehensive DWLS, highlighting the therapeutic synergy between medication and high-level behavioral adherence. These findings suggest that identifying predictors of engagement and adherence is crucial for maximizing outcomes. The Juniper UK DWLS is a comprehensive service that combines Tirzepatide with MDT guidance and app-based behavioral support.

This study addresses the existing knowledge gap by retrospectively analyzing a large cohort of patients enrolled in the Juniper UK DWLS to determine the effectiveness of the comprehensive Tirzepatide-supported program over 12 months. Our primary aims are to evaluate the percentage of patients achieving 12-month program adherence and to calculate the mean weight loss among this adherent cohort. Secondary objectives include comparing outcomes (mean weight loss at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, and side effect incidence) between the full cohort and the adherent sub-cohort, and identifying the demographic, clinical, and behavioural factors that predict both weight loss and 12-month adherence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

This study retrospectively analysed data from all patients who commenced the Tirzepatide-supported Juniper UK program between January 1 and 11 November 2024. All study data were retrieved from the Juniper central data repository on Metabase – an open-source business intelligence tool. The study received human ethics approval from the Just Reasonable Independent Research Ethics Committee on 18 August 2025 (IREC015). Investigators followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE) guidelines throughout the study.

2.2. Program Overview

Prospective patients of the Juniper UK DWLS complete a pre-consultation questionnaire that a pharmacist independent prescriber uses to determine their eligibility for the service. These questionnaires contain up to 100 questions and are often supported with medical imaging, pathology results, and/or reports from previous clinicians, should prescribers request them.

Prescribing practitioners base their Juniper UK eligibility decisions on the Mounjaro medication guide, which details body mass index (BMI) ranges, contraindications, and drug interactions. Inclusion criteria include a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2 for patients of non-Caucasian ethnicity, a BMI of at least 30 kg/m2 for everyone else, plus at least one weight-related comorbidity (e.g., hypertension, obstructive sleep apnoea). Hard exclusion criteria included the following contraindications: multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2, a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer, acute kidney disease, acute gallbladder disease, acute pancreatitis, hypoglycaemia, severe gastrointestinal disease, and a known hypersensitivity to Tirzepatide or any of the product’s components.

All prescribing actions are automatically recorded in the Juniper clinical auditing repository on Jira. This system utilizes data analytics to flag potential errors or safety issues for auditors. Patients enrolled in the Juniper UK DWLS are assigned a multidisciplinary care team (MDT), which includes a pharmacist independent prescriber, a university-qualified health coach, a pharmacist, and a medical support officer. Interactions between the patient and their MDT occur via the Juniper mobile application. All patient-MDT communications and program entries (such as weight and progress tracking) are automatically uploaded to the central data repository for efficient care coordination and data management.

During the study period, the Juniper UK DWLS only provided medication-supported therapy, i.e., it has never offered standalone lifestyle or GLP-1 RA/dual GIP/GLP-1 RA treatment. After paying the first monthly subscription fee, Juniper patients receive their initial one-month supply of medication along with access to personalized lifestyle coaching. This coaching is delivered through the Juniper app and provides multimodal educational content, progress trackers, and customized meal and exercise plans. Patients continue to receive monthly medication until (and including) month 4, unless they discontinue payment or choose to opt out of the program. Prescribing clinicians are mandated to assess patients at the 5-month mark of their treatment journey. Patients must be approved by their prescribing clinician at this 5-month follow-up consultation to receive their 5th medication order and continue with lifestyle coaching. Although the MDT encourages patients to log weight data fortnightly via the app, this follow-up consultation is the first time since the program started that weight data is a mandatory requirement for continued participation. Patients are instructed to notify their MDT immediately if any side effects occur.

2.3. Medication Titration Schedule

Juniper's prescribing clinicians adhere to the Mounjaro medication guidelines to establish patient titration schedules. The standard recommended schedule is: 2.5mg once weekly for four weeks, followed by increases of 2.5mg every four weeks, up to a maximum of 15mg if required (for example, 5mg once weekly for weeks 5-8, 7.5mg once weekly for weeks 9-12, and so on). However, prescribers retain the clinical judgment to postpone up-titration if a patient's condition makes the standard schedule inappropriate (for instance, if a patient reports adverse events or confirms a missed dose).

2.4. Program Cost

Monthly fees for the Juniper UK DWLS varied by the patient’s medication dose, ranging from 149 to 339 Great British Pounds.

2.5. Endpoints

The study’s primary endpoints were the percentage of patients who reasonably adhered to the Juniper program over a 12-month period and the mean weight loss among these patients. Adherence was determined by the following criteria: patients received a minimum of 10 Tirzepatide orders and submitted weight data between 355 and 375 days after program initiation (10 days either side of 12 months (365 days)). The ≥ 10 order threshold was selected to ensure adequate treatment exposure while accounting for patients who may have paused or delayed treatment for a short period.

Secondary endpoints included a comparison of side effect incidence and the mean weight loss at 3,6,9 and 12 months between the full and adherent cohorts. All missing weight data in the full cohort were imputed via the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. The analysis also sought to understand the factors influencing weight loss in the adherent cohort and 12-month adherence in the full cohort. These factors ranged from demographic variables such as initial BMI and comorbidities to behavioural variables such as weight tracking frequency, health coach message frequency, and maximum Tirzepatide dosage. Weight tracking frequency and health coach communication frequency were calculated by dividing the number of weeks in which a patient tracked or communicated at least once by the number of weeks they were on the program, multiplied by 100 (e.g., a patient was on the program for 8 weeks, and tracked their weight 10 times across weeks 4 and 5 week only: 2/8 *100 = 25%).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Means and standard deviations reported for descriptive data. Multiple linear regression was performed to assess the effect of demographic, clinical and behavioural variables on 12-month weight loss. Binary logistic regression was run to identify the predictors of 12-month adherence (yes/no). For both models, certain numeric variables such as initial BMI, month-1 track count and initial comorbidities were dichotomized or categorized into factor variables wherever investigators determined this would add important clinical nuance to the results. Side effect incidence (yes/no) was compared between the full and adherent cohorts using an Exact Binomial test. All visualizations and statistical analyses were performed on RStudio, version 2023.06.1+524 (RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, Boston, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive data

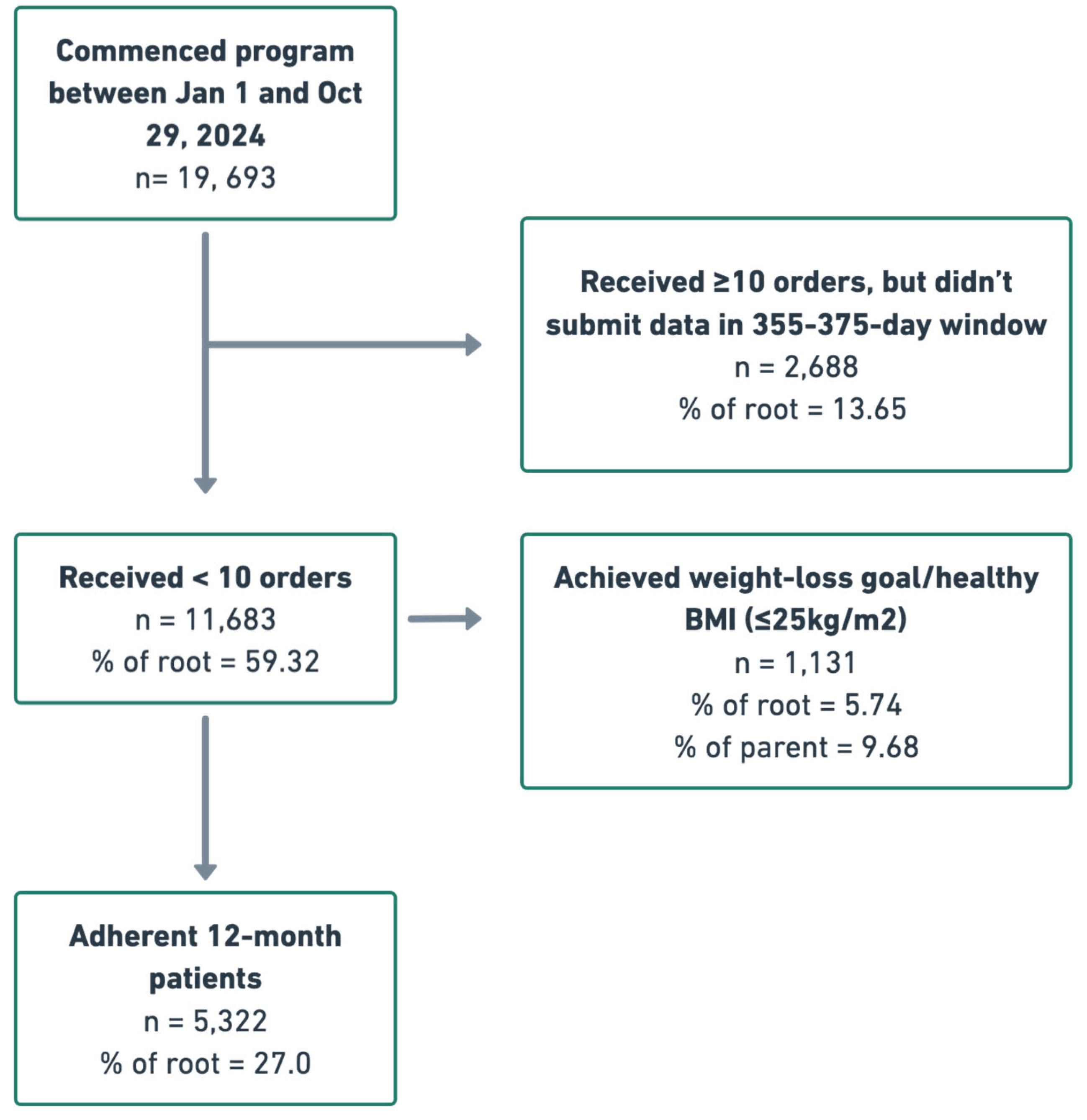

In total, 19,693 patients commenced the Tirzepatide-supported Juniper UK program between January 1 and October 29, 2024. Among these patients, 5322 (27%) satisfied the 12-month program adherence criteria. A further 2688 (13.65%) were relatively adherent to their medication schedule, receiving a minimum of 10 orders of Tirzepatide, but did not submit weight data within the 351-379-day window. Of the remaining 11683 (59.32%) patients, 1131(9.68%) achieved a healthy BMI or their target weight. The full patient flow is visualised in

Figure 1. Across the full cohort, mean patient age was 43.10 (±11.9) years and mean initial BMI was 34.96 (±6.91) kg/m

2 (

Table 1). Nearly 90 percent (89.69) of patients were female at birth and 16150 (82%) were of Caucasian ethnicity.

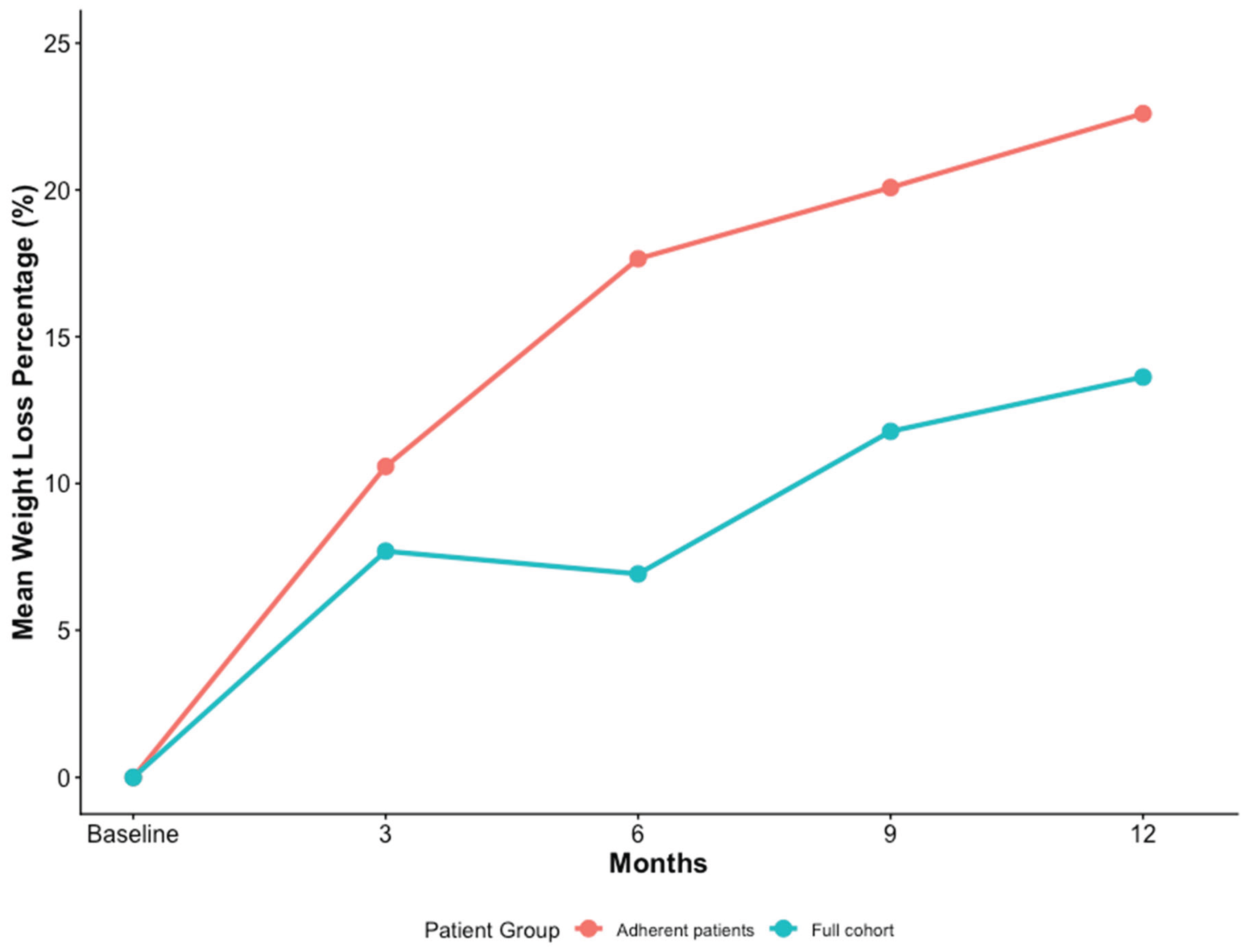

In the adherent cohort, the mean 12-month weight loss was 22.60 (±7.46) percent, with 5261 (98.85%) patients losing a minimum of 5 percent of their baseline weight and 5084 (95.53%) reaching the 10 percent milestone (

Table 2). In the full cohort, which used the LOCF method to impute missing data, the mean 12-month weight loss figure was 13.62 (±10.85) percent. Similar differences were observed across the other 3 intervals: 3-month, 6-month and 9-month weight loss (

Figure 2). Regarding side effects, 16,356 (83.05%) patients in the full cohort reported at least one adverse event, versus 5084 (95.53%) patients in the adherent cohort. A one-sample Exact Binomial Test test revealed that this difference was statistically significant (CI = [0.949,0.961],

p < 0.001). Among the patients who reported side effects, the distribution of worst side effect severity was comparable across the two cohorts, with mild being the most common level in both (~57-58%).

3.2. Weight-Loss Covariates

A generalized linear regression model was run to predict 12-month weight loss in the adherent cohort, explaining 39.94% of the variance in the outcome (

Appendix A). Statistically significant predictors were found across demographic, clinical, and behavioral factors. Regarding demographics, age was negatively associated with 12-month weight loss (

β = -0.10, p < 0.001), and being male at birth was also associated with a significant decrease (

β = -3.54, p < 0.001). The ethnicity binary also had a weak but statistically significant association with weight-loss, with white patients tending to lose more weight than non-white patients (

β = 0.62, p < 0.05).Relative to the most populated BMI group (30-34.99kg/m

2), the lowest category (<30 kg/m

2) lost significantly less weight (

β= -4.16, p < -0.001), whereas the three higher BMI categories (35-39.99; 40-44.99; >45 kg/m

2) lost statistically more weight (

β= 2.34, p < -0.001;

β= 2.36, p < -0.001;

β= 1.04, p < -0.001).

Behavioral engagement was also found to be a key factor, as a higher weekly weight track percentage was positively associated with 12-month weight loss (β: 0.084, p < 0.001). Conversely, weight tracking in the first month was negatively correlated with weight loss in the three highest categories, relative to patients who only tracked once (baseline weight). Patients in the 16-25 weight entry and >25 weight entry categories lost an average over 4 percentage points less than the baseline group (both p<0.001), while the reduction in the 11-15 weight entries category was over 3 percentage points (p < 0.01). Early progress was strongly predictive, with one-month weight-loss percentage showing a strong positive association (β= 0.93, p < 0.001) with 12-month weight loss. Similarly, achieving clinically significant weight loss at month 3 (≥5%) correlated with a substantial increase in the outcome (β: 5.00, p < 0.001), as did the attainment of a healthy BMI (<25 kg/m2) or their goal weight (β: 4.18, p < 0.001).

Relative to the highest maximum Tirzepatide dose (15mg), significant differences were observed in the 7.5mg (β= -1.30, p < 0.001), 5mg (β= -2.49, p < 0.001) and 2.5mg (β= -2.95, p < 0.05) categories, but not in the 10mg, and 12.5mg categories. The presence of baseline comorbidities, side effect incidence and weekly health coach messaged percentage were not found to be statistically significant predictors of 12-month weight-loss.

3.3. Program Adherence Covariates

A generalized linear model (Logistic Regression, binomial family) was run to predict 12-month adherence (Adherent vs. Churned), explaining 23.91% of the variability in the outcome R

2 = 0.2391). Statistically significant predictors were found across demographic, clinical, and behavioral factors (

Appendix B). Older age (

β = 0.01, p < 0.01), being male at birth (

β = 0.38, p < 0.001), and White ethnicity (

β = 0.13, p < 0.05) were all associated with a statistically significant increase in the log-odds of 12-month adherence. Regarding BMI categories (relative to the reference group of 30–34.99 kg/m

2), only the highest BMI group (>45 kg/m

2) was significantly associated with a decrease in the log-odds of adherence (

β = -0.27, p < 0.001). Comorbidities showed marginal negative associations, with patients reporting three or more comorbidities having a

β = -0.20 (p = 0.056) and those reporting two comorbidities having a

β = -0.13 (p = 0.059).

Early success markers showed mixed effects, highlighting a distinction between velocity and sustainability. Achieving significant weight loss at month 3 (≥ 5%) was associated with an increase in the log-odds of adherence, though the relationship was marginally significant (β = 0.15, p = 0.06). Conversely, 1-month weight loss velocity was negatively associated with adherence in the highest loss categories, relative to the reference group (2.51%–5% loss). Patients with >10% loss at 1 month had a β = -0.49 (p < 0.001), meaning they were 1.67 times more likely to churn, and patients with 7.51%–10% loss were 1.36 times more likely to churn.

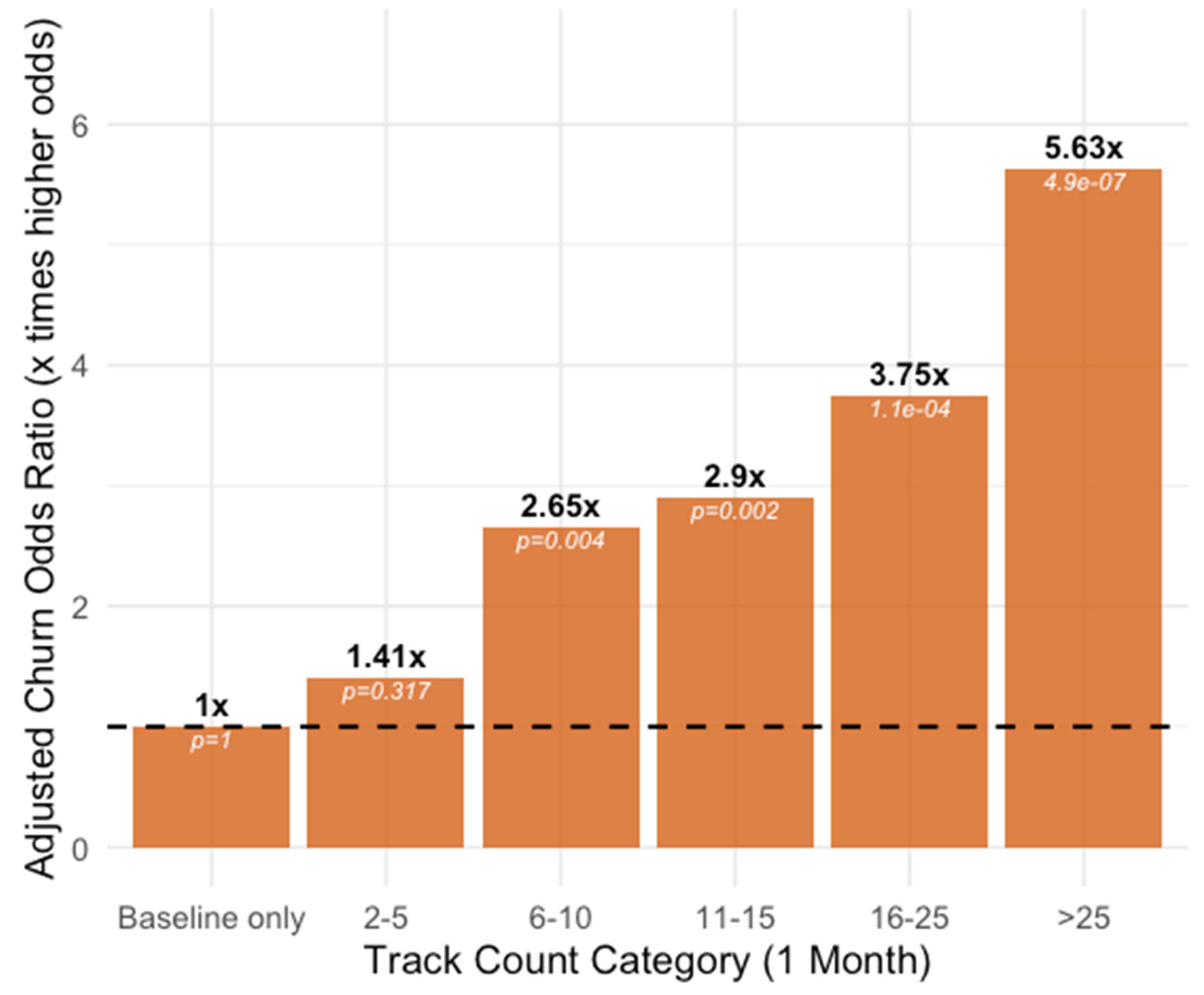

Behavioural engagement showed the strongest correlations: weekly weight track percentage was the most powerful predictor, with a large positive association with adherence (

β = 0.048, p < 0.001). However, high tracking frequency in the first month was strongly and negatively associated with adherence, consistent with the weight loss velocity finding. Patients in the >25 weight entry category had the largest negative coefficient (

β = -1.73, p < 0.001), followed by the 16–25 entry category (

β = -1.32, p < 0.001), the 11-15 category (

β = -1.06, p < 0.001) and the 6-10 category (

β = -0.98, p < 0.01) (

Figure 3). The model demonstrated a strong positive association between weight outcome attainment and perseverance: attaining a healthy BMI or the patient’s target weight was highly predictive of 12-month adherence (

β = 0.48, p < 0.001). Patients who attained this outcome were 1.62 times more likely to be adherent at 12 months than those who did not. Reporting any side effects was also unexpectedly and significantly associated with an increase in the log-odds of adherence (

β = 0.47, p < 0.001). Finally, weekly health coach messaged percentage was a strong positive predictor of adherence (

β = 0.027, p < 0.001), whereas previous use of modern weight-loss medications (Semaglutide, Liraglutide or Tirzepatide) was a negative predictor (

β = -0.35, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This retrospective cohort study of 19,693 patients enrolled in the Tirzepatide-supported Juniper UK DWLS provides essential real-world evidence regarding 12-month effectiveness and adherence predictors in a comprehensive digital obesity setting.

A primary finding is the mean 12-month weight loss of 22.60 (±7.46) percent observed in the adherent cohort (n=5,322). This outcome demonstrates an efficacy level comparable to the mean weight loss achieved in highly controlled RCTs of Tirzepatide [

8], and the 11-month figure reported in the engaged cohort of the Johnson et al study (M = 21.5%). The results align with NICE guidelines on combining dual GIP/GLP-1 RA pharmacotherapy with comprehensive, app-based MDT support. Furthermore, the finding that 98.85 percent of adherent patients achieved the clinically significant 5 percent weight-loss threshold suggests that medicated DWLSs deliver reliable outcomes to adherent patients.

However, the contrast between the adherent cohort's success and the full cohort's LOCF mean weight loss of 13.62 (±10.85) percent highlights the major public health challenge of adherence. With only 27 percent of patients satisfying the strict 12-month adherence criteria, the significant difference in outcomes reveals that while the medication is highly effective, the benefits are limited to those who successfully persist through the duration of the program. Transparent reporting of both the adherent and full (LOCF) cohorts is thus essential for accurately conveying a program’s overall impact.

The predictive models revealed that behavioral engagement is the most powerful determinant of long-term success. The positive association between weekly weight track percentage and both 12-month weight loss (

β = 0.084, p < 0.001) and adherence (

β = 0.048, p < 0.001) confirms the findings of Johnson et al. [

13] and broader DWLS literature that sustained, consistent engagement with tracking tools is crucial for facilitating self-monitoring and reinforcing habit change [

12]. Similarly, the strong positive relationship between weekly health coach message percentage and adherence (

β = 0.027, p < 0.001) demonstrates that active, ongoing MDT communication is a key component in preventing patient dropout, possibly by resolving issues quickly or providing motivation.

A novel and critical finding is the negative association between hyper-engagement during the first month (specifically high weight tracking frequency and high initial weight loss velocity) and 12-month adherence. Patients in the highest weight entry categories were substantially more likely to churn, and patients achieving >10% weight loss at month 1 were 1.67 times more likely to churn than the reference group. Importantly, this trend was observed even while controlling for the attainment of a health BMI (<25%) or a patient’s target weight, which was positively correlated with 12-month adherence. These discoveries suggest that while early success is a motivator, excessive early weight-loss may lead to unsustainable habits or rapid goal attainment followed by subsequent disengagement – a phenomenon often termed "burnout." The findings specific to first month weight tracking were even starker. Not only did patients in the highest three tracking categories (>25; 16-25; 11-15) experience significantly lower weight loss than the baseline group (1 weight entry), but they were also significantly less likely to adhere to the program for 12 months (along with patients in the 6-10 category). While this discovery lacks clear precedent in the wider chronic disease management literature, it may stem from a combination of heightened performance anxiety and misaligned expectations concerning the speed of weight-loss outcomes [

15,

16]. These expectations have possibly been exaggerated by success narratives surrounding new weight-loss pharmaceuticals on mainstream and social media [

17,

18]. When this intense initial commitment does not immediately translate into continued exponential loss, the resulting tracking fatigue or disillusionment can lead to disengagement and program dropout. DWLS clinicians may view these findings on hyper initial engagement and adherence as an opportunity to coach patients toward sustainable, moderate pacing.

The counter-intuitive finding that reporting any side effects was significantly associated with an increase in the log-odds of 12-month adherence (β = 0.47, p < 0.001) must be interpreted within the comprehensive care model. Adherent patients, who are consistently engaged with the program, are the most likely to diligently report adverse events to their MDT via the app, as instructed. Patients who churned may have stopped using the app due to side effects without formally recording them. Therefore, this correlation likely reflects an adherence bias in reporting, rather than a protective effect of side effects on perseverance. Clinically, this result emphasizes the importance of a structured reporting pathway (like the app) for capturing safety data among engaged users. It also highlights the utility of exit surveys as a means of monitoring the proportion of patients whose side effects were the primary factor behind their discontinuation. Unfortunately, data from Juniper exit surveys were too incomplete to incorporate into this analysis – a limitation affected by the legal restriction on mandating their completion.

Regarding demographic factors, older age (

β = -0.10, p < 0.001) and male sex at birth (

β = -3.54, p < 0.001) were negative predictors of weight loss, aligning with commonly observed trends in weight management literature. Older age is known to present unique barriers to sustained weight loss, as research suggests that increased work and family commitments can hinder the maintenance of healthy diets [

19,

20], while physiological changes such as pre-existing sarcopenia and a lower basal metabolic rate may intrinsically limit the potential for weight reduction in older populations [

21,

22].

Additionally, the greater percentage weight loss observed in patients with higher initial BMI (relative to the 30–34.99 kg/m

2 group is expected) likely reflects the ceiling effect of percentage weight loss in individuals with greater initial weight [

23]. Interestingly, the opposite trend has been observed in a previous study of the Juniper program, although this may have been due to its shorter duration (16 weeks) or the fact that the association was not controlled both other key covariates [

24]. Finally, the discovery that a disproportionate number of non-Caucasian patients failed to adhere to the program for 12 months is consistent with previous research on DWLSs and chronic care services in general [

25,

26]. Although income-related data were not available, It is likely that this trend is a reflection of Juniper UK’s high monthly fee.

This study’s interpretation is limited by its retrospective design, which can only establish correlations, not causation. Although the scale of the cohort is a major strength, the reliance on LOCF for the full cohort introduces a known conservative bias that may not accurately reflect the mean weight loss achieved by those who dropped out early. The sample was also overrepresented by female and Caucasian patients, and given the program fee, would have likely excluded patients of lower socioeconomic status. These factors limit the study’s generalizability. Furthermore, the analysis relies on patient-reported data, such as weight entries and side effect reports, which may be subject to desirability or measurement bias. Finally, analyses would have been enriched by discontinuation reason data, which investigators did not have access to.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective analysis confirms that the Tirzepatide-supported DWLSs are capable of delivering good long-term weight-loss outcomes, with the adherent cohort achieving a mean 12-month loss of 22.60 (±7.46) percent. This finding validates NICE guidelines of using pharmacotherapy as a supplement to continuous multidisciplinary care.

However, the primary translational challenge lies in patient retention, as evidenced by the low (27%} adherence rate and the subsequent reduction in mean weight loss to 13.62% across the full, intent-to-treat cohort. These data underscore that the substantial benefits of Tirzepatide are contingent upon persistence in the program, making adherence the single most critical public health hurdle for digital obesity services.

The study’s predictive models provide clear clinical guidance for overcoming this challenge. The strongest predictors of success were not initial results but markers of long-term consistency: high weekly weight-tracking percentage and frequent health coach communication. Crucially, the discovery that hyper-engagement and high-velocity weight loss in the first month are negatively associated with 12-month adherence suggests clinicians should actively intervene to manage performance anxiety and temper potentially unrealistic patient expectations fuelled by public discourse. Coaching strategies should focus on sustainable, moderate pacing rather than intensive, rapid initial weight loss to mitigate the risk of burnout and subsequent dropout.

In conclusion, while medicated DWLSs deliver reliable outcomes to adherent patients, their overall effectiveness relies on improving long-term adherence. Future prospective studies should investigate targeted interventions designed to promote consistent, moderate engagement throughout the initial months of treatment to maximize patient persistence and optimize therapeutic outcomes at scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T., N.A., and J.H.; methodology, L.T., J.H., and T.S.; software, L.T.; validation, L.T., J.H., T.S., and N.A.; formal analysis, L.T., J.H.; investigation, L.T., J.H., and T.S.,; resources, L.T., and N.A.,.; data curation, L.T., J.H., T.S.,.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T.; writing—review and editing, L.T., J.H., and T.S.; visualization, L.T.; supervision, L.T., J.H.; project administration, L.T., J.H., and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received human ethics approval from the Just Reasonable Independent Research Ethics Committee on 18 August 2025 (IREC015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw study data will be made available by authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all clinicians and patients whose data contributed to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

L.T is paid a salary by Eucalyptus (Juniper parent company) and N.A is a paid advisor at the company.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DWLS |

Digital Weight-Loss Service |

| GLP-1 RAs |

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists |

| GIP |

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide |

| MDT |

Multidisciplinary team |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Generalized Linear Model – Weight Loss Covariates.

Table A1.

Generalized Linear Model – Weight Loss Covariates.

| Predictor Variable |

Estimate (β)

|

Std. Error |

t value |

p value |

| (Intercept) |

15.01 |

1.32 |

11.33 |

<0.001*** |

| Age |

-0.10 |

0.01 |

-12.90 |

<0.001*** |

| Sex at birth |

-3.54 |

0.30 |

-11.68 |

<0.001*** |

| Ethnicity binary (white) |

0.62 |

0.24 |

2.47 |

0.01* |

| BMI <30 kg/m2 (ref = 30-34.99) |

-4.16 |

0.23 |

-17.82 |

<0.001*** |

| BMI 35-39.99 kg/m2 (ref = 30-34.99) |

2.34 |

0.22 |

10.85 |

<0.001*** |

| BMI 40-44.99 kg/m2 (ref = 30-34.99) |

2.36 |

0.28 |

8.43 |

<0.001*** |

| BMI >45 kg/m2 (ref = 30-34.99) |

1.04 |

0.31 |

3.34 |

<0.001*** |

| ≥3 Comorbidities (ref = 0) |

-0.50 |

0.40 |

-1.29 |

0.26 |

| 2 Comorbidity (ref = 0) |

-0.12 |

0.27 |

-1.22 |

0.22 |

| 1 Comorbidity (ref = 0) |

-0.20 |

0.18 |

-0.44 |

0.66 |

| First month weight track count ≥25 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-4.28 |

1.19 |

-3.59 |

0.001*** |

| First month weight track count 16-25 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-4.15 |

1.86 |

-3.50 |

<0.001*** |

| First month weight track count 11-15 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-3.37 |

1.19 |

-2.84 |

<0.01** |

| First month weight track count 6-10 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-3.00 |

1.18 |

-2.54 |

0.01* |

| First month weight track count 2-5 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-0.78 |

1.21 |

-0.65 |

0.52 |

| Any side effects |

-0.30 |

0.39 |

-0.78 |

0.44 |

| Weekly health coach message frequency |

-0.00 |

0.01 |

-0.52 |

0.61 |

| Previous use of modern weight-loss medications |

-0.19 |

0.28 |

-0.68 |

0.50 |

| Weekly weight track frequency |

0.08 |

0.00 |

19.91 |

<0.001*** |

| Healthy BMI or target weight |

4.13 |

0.20 |

20.55 |

<0.001*** |

| Maximum dose 2.5mg |

-2.95 |

1.26 |

-2.23 |

0.02* |

| Maximum dose 5mg |

-2.49 |

0.46 |

-5.37 |

<0.001*** |

| Maximum dose 7.5mg |

-1.3 |

0.34 |

-3.82 |

<0.001*** |

| Maximum dose 10mg |

-0.13 |

0.24 |

-0.55 |

0.58 |

| Maximum dose 12.5mg |

0.21 |

0.25 |

0.85 |

0.39 |

| Overall Model Fit (R2) = 0.3994 |

|

|

|

|

Appendix B

Table A2.

Logistic Regression Model – Adherence Covariates.

Table A2.

Logistic Regression Model – Adherence Covariates.

| Predictor Variable |

Estimate (Log- Odds) |

Odds Ratio (OR) |

z value |

p value |

| (Intercept) |

-2.29 |

0.10 |

-6.15 |

<0.001*** |

| Age |

0.01 |

1.01 |

2.65 |

<0.01** |

| Sex at birth (male) |

0.38 |

1.47 |

5.14 |

<0.001*** |

| Ethnicity binary (White) |

0.13 |

1.14 |

2.27 |

0.02* |

| BMI <30 kg/m2 (ref = 30-34.99) |

0.01 |

1.01 |

0.18 |

0.86 |

| BMI 35-39.99 kg/m2 (ref = 30-34.99) |

-0.02 |

1.02 |

-0.28 |

0.78 |

| BMI 40-44.99 kg/m2 (ref = 30-34.99) |

-0.11 |

1.11 |

-1.47 |

0.15 |

| BMI >45 kg/m2 (ref = 30-34.99) |

-0.27 |

1.31 |

-3.30 |

<0.001*** |

| ≥3 Comorbidities (ref = 0) |

-0.20 |

1.19 |

-1.66 |

0.06 |

| 2 Comorbidities (ref = 0) |

-0.13 |

1.13 |

-1.76 |

0.08 |

| 1 Comorbidity (ref = 0) |

-0.07 |

0.05 |

-1.57 |

0.12 |

| First month weight track count ≥25 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-1.73 |

5.63 |

-5.04 |

<0.001*** |

| First month weight track count 16-25 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-1.32 |

3.75 |

-3.87 |

<0.001*** |

| First month weight track count 11-15 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-1.06 |

2.90 |

-3.87 |

<0.01** |

| First month weight track count 6-10 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-0.98 |

2.65 |

-2.87 |

<0.01** |

| First month weight track count 2-5 (ref = 1/baseline) |

-0.35 |

1.41 |

-1.01 |

0.31 |

| Any side effects |

0.47 |

1.61 |

5.52 |

<0.001*** |

| Weekly health coach message frequency |

0.03 |

1.03 |

10.71 |

<0.001*** |

| Weekly weight track frequency |

0.05 |

1.05 |

47.35 |

<0.001*** |

| Healthy BMI or target weight |

0.48 |

1.62 |

8.56 |

<0.001*** |

| Previous use of modern weight-loss medications |

-0.35 |

0.71 |

-5.38 |

<0.001*** |

| Significant (≥5%) weight-loss by 3 months |

0.15 |

0.16 |

1.82 |

0.06 |

| Month 1 weight loss ≥0% (ref: 2.51-5%) |

0.13 |

1.14 |

1.12 |

0.26 |

| Month 1 weight loss 0.01-2.5% (ref: 2.51-5%) |

-0.07 |

0.93 |

-0.91 |

0.36 |

| Month 1 weight loss 5.01-7.5% (ref: 2.51-5%) |

-0.31 |

0.91 |

-1.94 |

0.05 |

| Month 1 weight loss 7.51-10% (ref: 2.51-5%) |

-0.49 |

0.74 |

-4.53 |

<0.001*** |

| Overall Model Fit (R2) = 0.238 |

|

|

|

|

References

- Malnick, S.D.H. ; Knobler, H The medical complications of obesity. QJM, 2006, 99, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2025). Obesity and overweight. (Accessed November 2025). 20 November.

- Poirier, P. , Giles, T.D., Bray, G.A., Hong, Y., Stern, J.S., Pi-Sunyer, F.X., Eckel, R.H. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology and Vascular Biology, 2006, 26, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, F.M. , Bray, G.A., Carey, V.J., Smith, S.R., Ryan, D.H., Anton, S.D., McManus, K., Champagne, C.M., Bishop, L.M., Laranjo, N., Leboff, M.S., Rood, J.C., de Jonge, L., Greenway, F.L., Loria, C.M., Obarzanek, E., Williamson, D.A. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med, 2009, 360, 1948–1961. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G., Krauthamer, M., Bjalme-Evans, M. Wegovy (Semaglutide): a new weight loss drug for chronic weight management. J Investig Med, 2021, 1, 5–13.

- Wilding, J.P.H. , Batterham, R.L., Calanna, S., Davies, M., Van Gaal, L.F., Lingvay, I., McGowan, B.M., Rosenstock, J., Tran, M.T.D., Wadden, T.A., Wharton, S., Yokote, K., Zeuthen, N., Kushner, R.F. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med, 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M. A. , Quast, D. R., Wefers, J., & Meier, J. J. Dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonism: a novel concept in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2021, 9, 866–881. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. , Shi, H., Xie, M., Sun, Y., & Nahata, C.M. The Efficacy and Safety of Tirzepatide in Patients with Diabetes and/or Obesity: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Pharmaceuticals, 2025, 18, 668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, E.S. , Fabry, A., Ho, A.S., May, C.N., Baldwin, M., Blanco, P., Smith, K., Michaelides, A., Shokoohi, M., West, M., Gotera, K., El Massad, O., Zhou, A. The Impact of a Digital Weight Loss Intervention on Health Care Resource Utilization and Costs Compared Between Users and Nonusers With Overweight and Obesity: Retrospective Analysis Study. J Med Internet Res, 2023, 25, e47083. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, R. , Wren, G.M., Whitman, M. The Potential of a Digital Weight Management Program to Support Specialist Weight Management Services in the UK National Health Service: Retrospective Analysis. JMIR Diabetes, 2023, 9, e52987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doshi, R. S. , Bittleman, D.B., Kelleher, K.M., Clark, J.M. Patient-Provider Communication in Virtual Weight Management Care. J Med Internet Res, 2015, 17, e227. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2025). Overweight and obesity management. (Accessed November 2025).

- Johnson, H. , Clift, A., Reisel, D., Huang, D. (2025) Digital engagement enhances dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist and GLP-1 receptor agonist efficacy: A retrospective cohort analysis of a digital weight loss service on outcomes and safety. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism.

- Ng. C., Divino, V., Wang, J., Toliver, J., Buss, M. () Real-world weight loss observed with semaglutide and tirzepatide in patients with overweight or obesity and without type 2 diabetes. Adv Ther, 2025, 42, 5468–5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpato, E., Toniolo, S., Pagnini, F., Banfi, P. The relationship between anxiety, depression, and treatment adherence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. 2021, 16, 2001–2021.

- Franek, J. Self-management support interventions for persons with chronic disease. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser, 2013, 13, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, H., Cheema, A. From prescription to trend: the misuse of Ozempic in the age of social media. Ann Med Surg (Lond), 2025, 87, 6876–6877. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhan, N., Schaalan, M., El-Sheikh, A. Patterns and predictors of self-medication behaviour of weight-loss medications: a cross-sectional analysis of social media influence and role of pharmacist intervention. Front Pharmacol, 2025, 16, 1606566. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, S., Beydoun, M., Evans, M., Zonderman, A., Kuczmarski, M Caregiver status and diet quality in community-dwelling adults. Nutrients, 2021, 13, 1803. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, J., Giskes, K., Turrell, G. Socio-economic differences in weight-control behaviours and barriers to weight control. Public Health Nutrition, 2011, 14, 1768–78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghbooli, Z., Mozaffari, S., Dehghani, Y., Amirkiasar, P., Malekhosseini, A., Rezanejad, M., Holick, M. The lower basal metabolic rate is associated with increased risk of osteosarcopenia in postmenopausal women. BMC Womens Health, 22(171).

- Batsis, J., Villareal, D. Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: aetiology, epidemiology and treatment strategies. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 14(9):513-537.

- Yan, F. , Chen, Y., Yu, D., Ma, H., Xu, L., & Hu, M. Probability of 5% or Greater Weight Loss or BMI Reduction to Healthy Weight Among Adults With Overweight or Obesity. JAMA Network Open, 2023, 6, e2327358. [Google Scholar]

- Talay, L., Vickers, M., Bell, C., Galvin, T. (2024). Weight loss and engagement in a Tirzepatide-supported digital obesity program: A four-arm patient-blinded retrospective cohort. Telemedicine Reports, 5(1).

- Talay, L., Vickers, M., Patient adherence to a real-world digital, asynchronous weight loss program that combines behavioural and GLP-1 RA therapy: A mixed methods study. Behav Sci, 14(6): 480.

- Marshall, P. , Marshall, S. T., & Marshall, J. L. Barriers to and Facilitators of Digital Health Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations: Qualitative Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res, 2023, 25, e42719. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).