Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

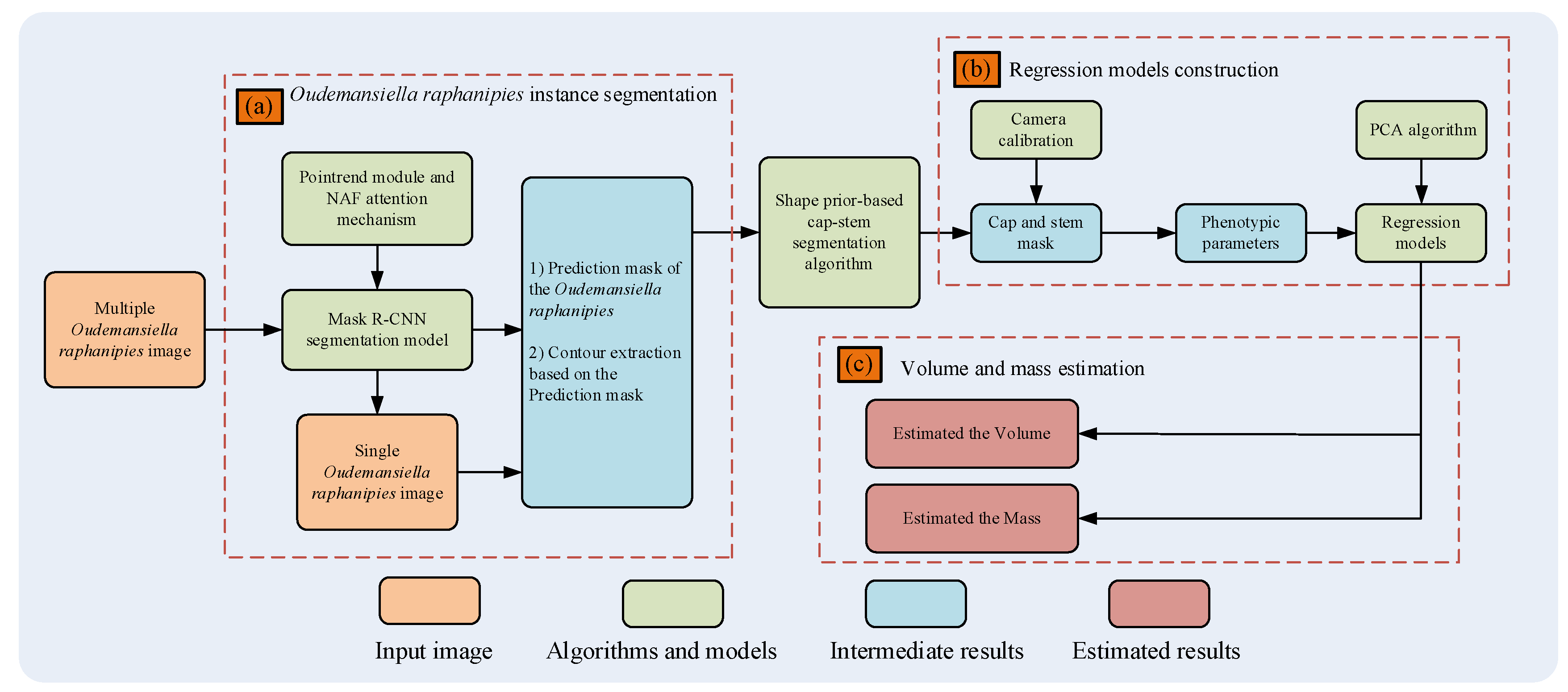

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

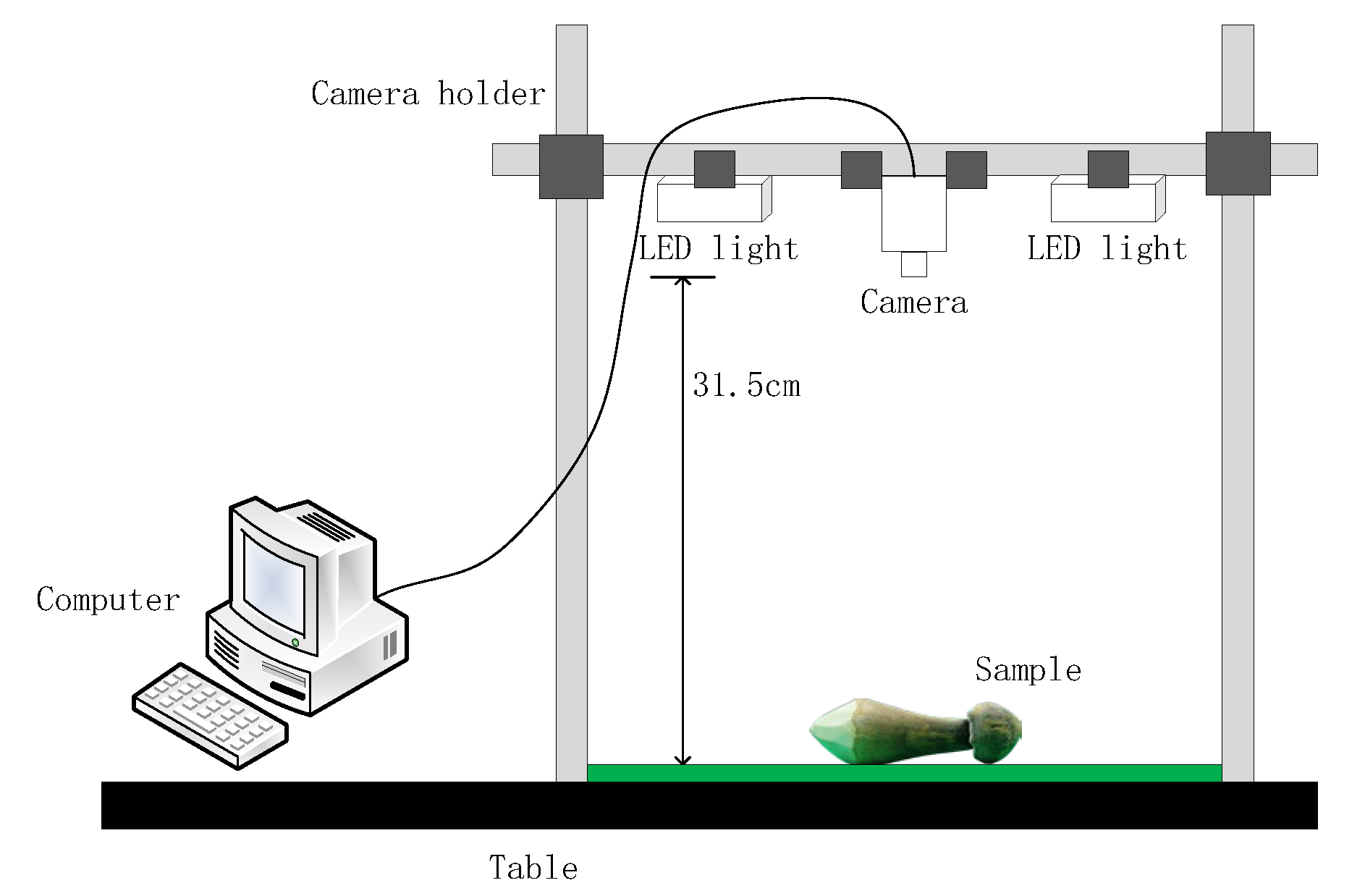

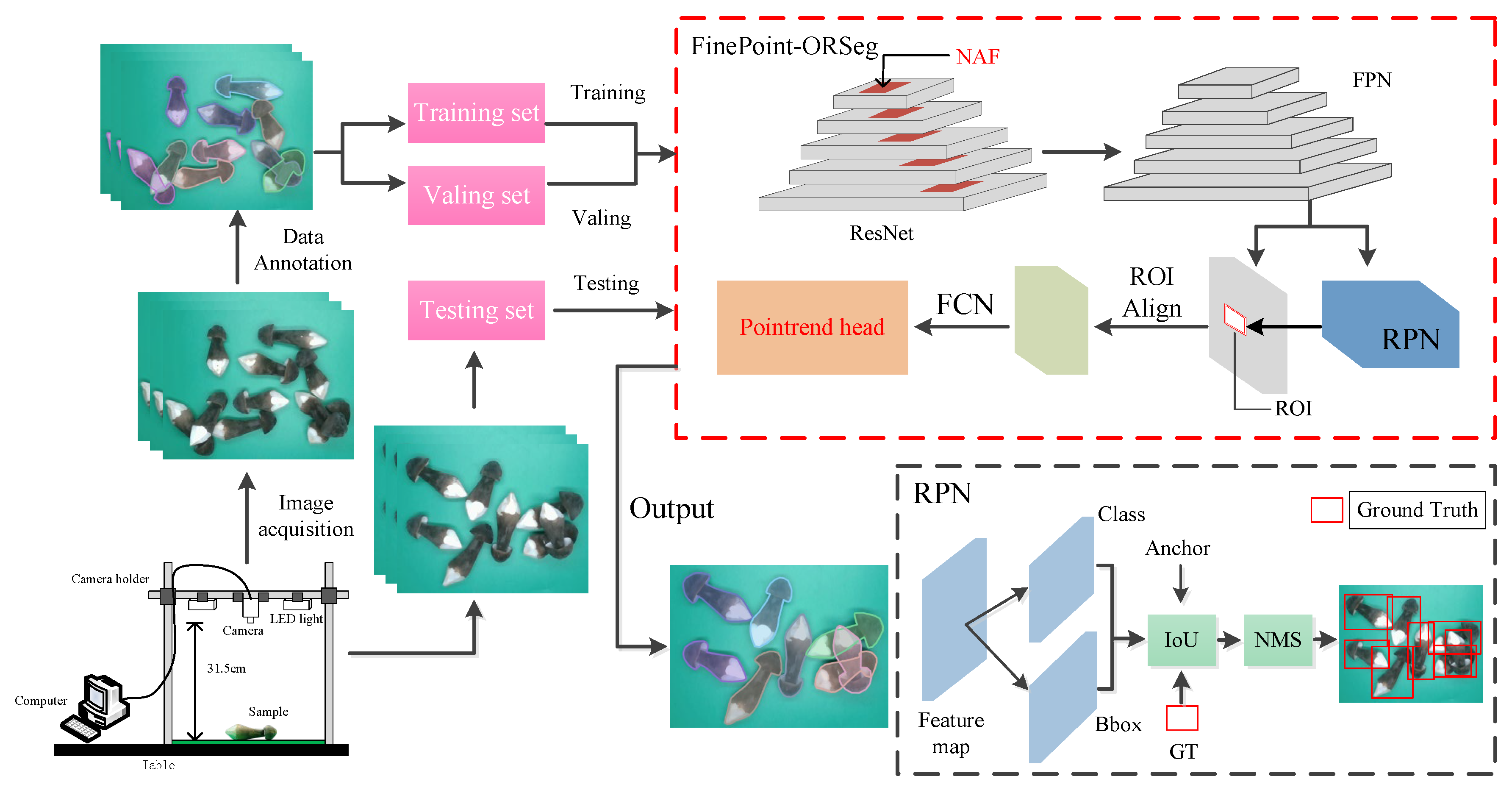

2.1.1. Image Acquisition System

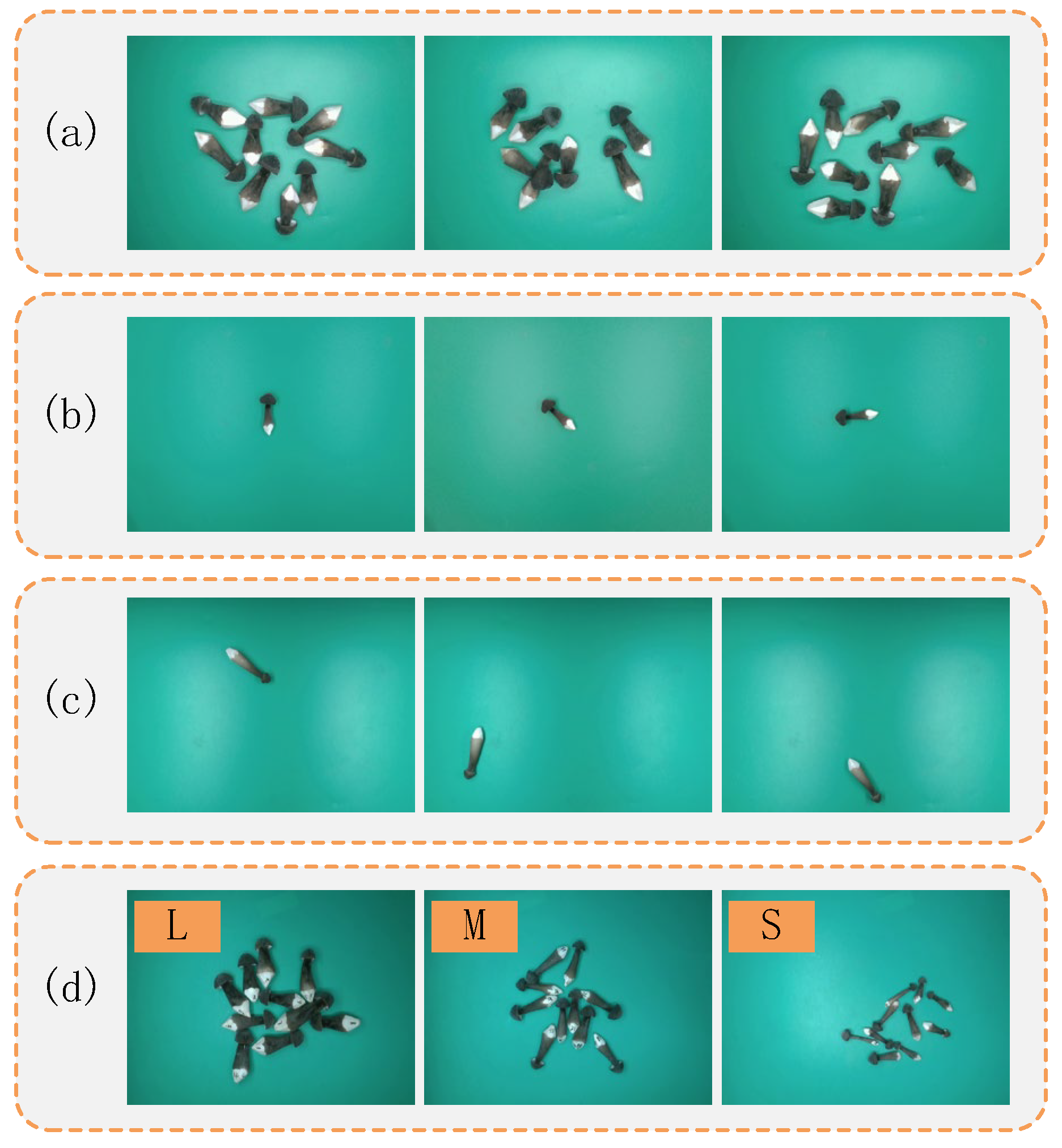

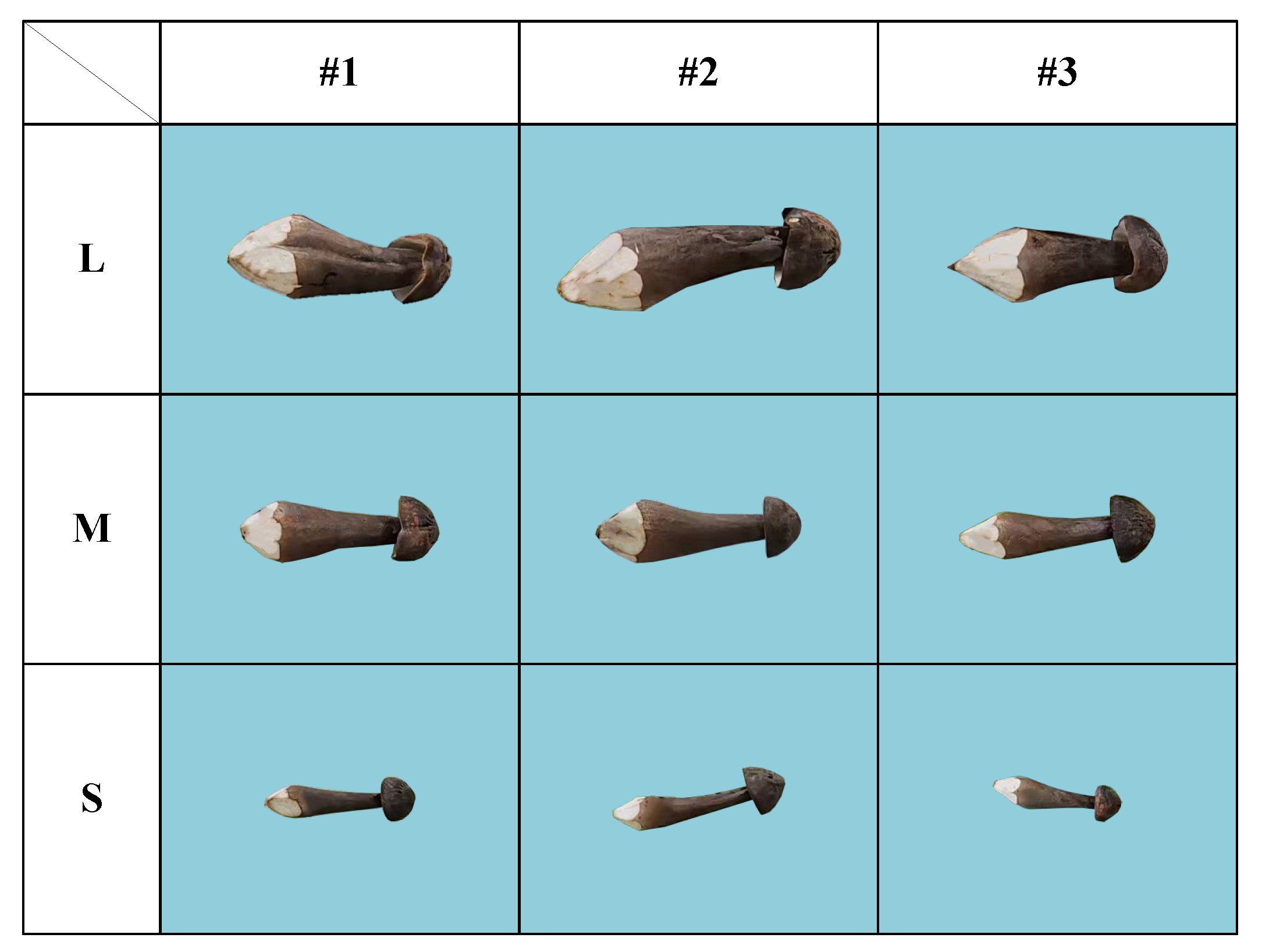

2.1.2. Dataset

2.2. Methods

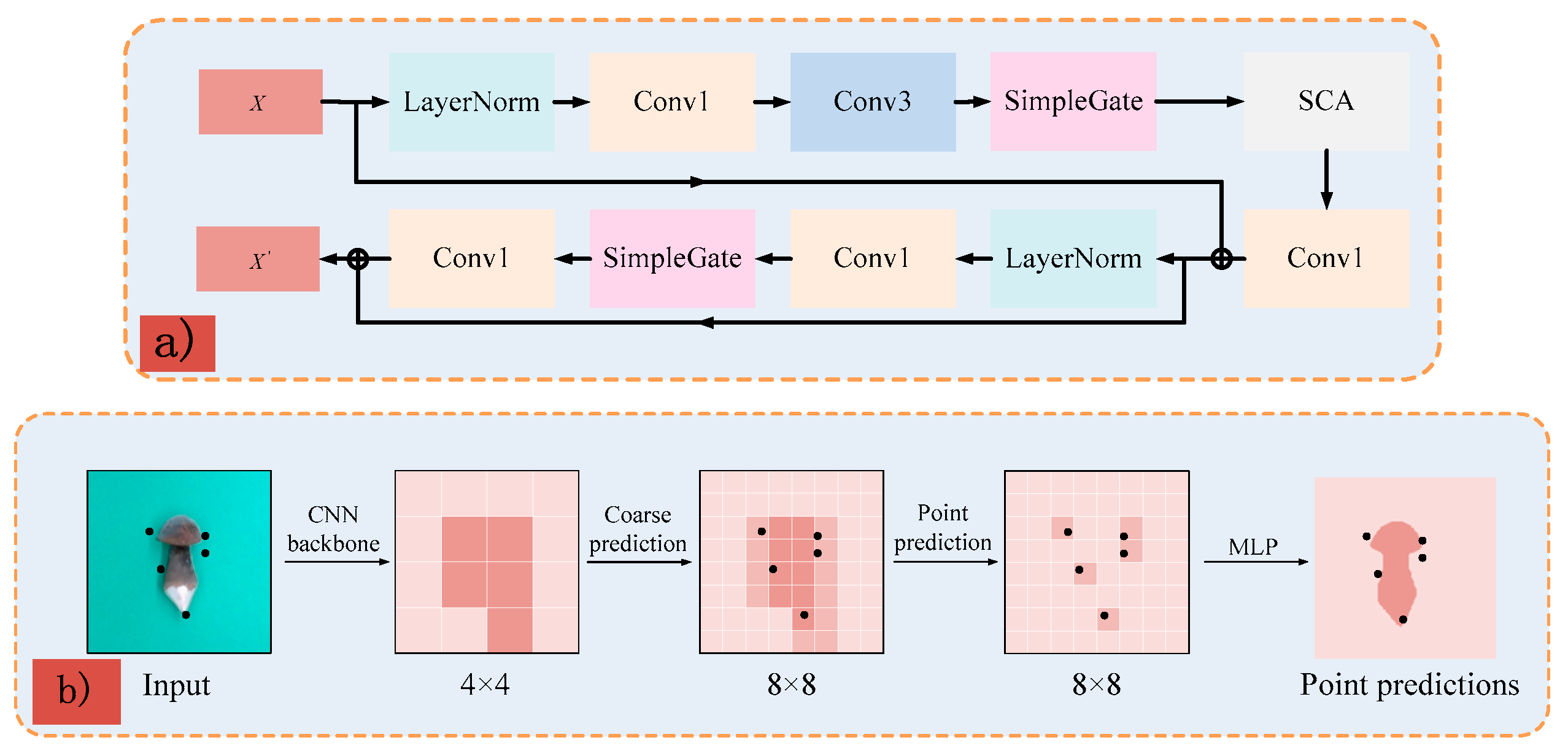

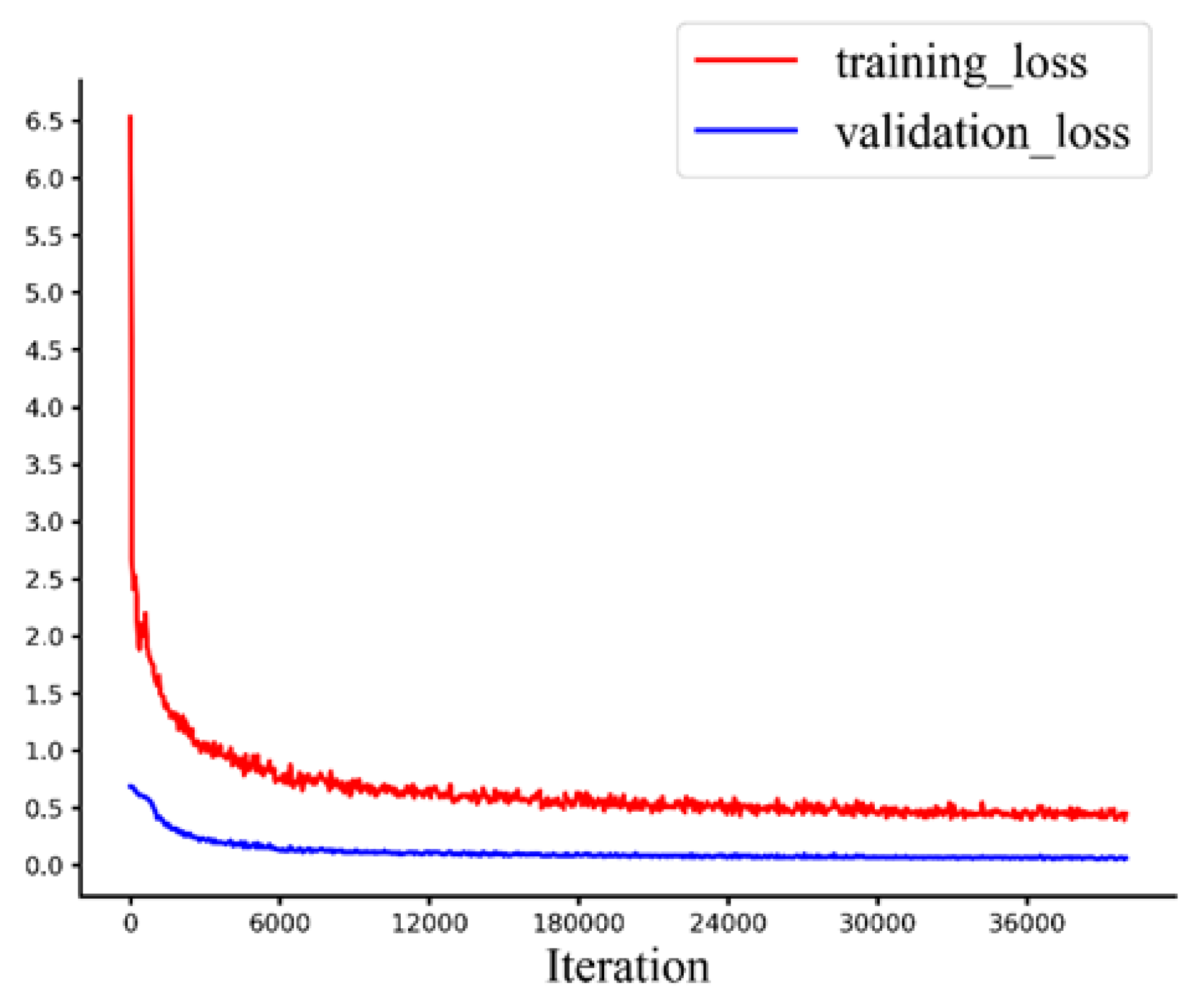

2.2.1. FinePoint-ORSeg Model for Sample Segmentation

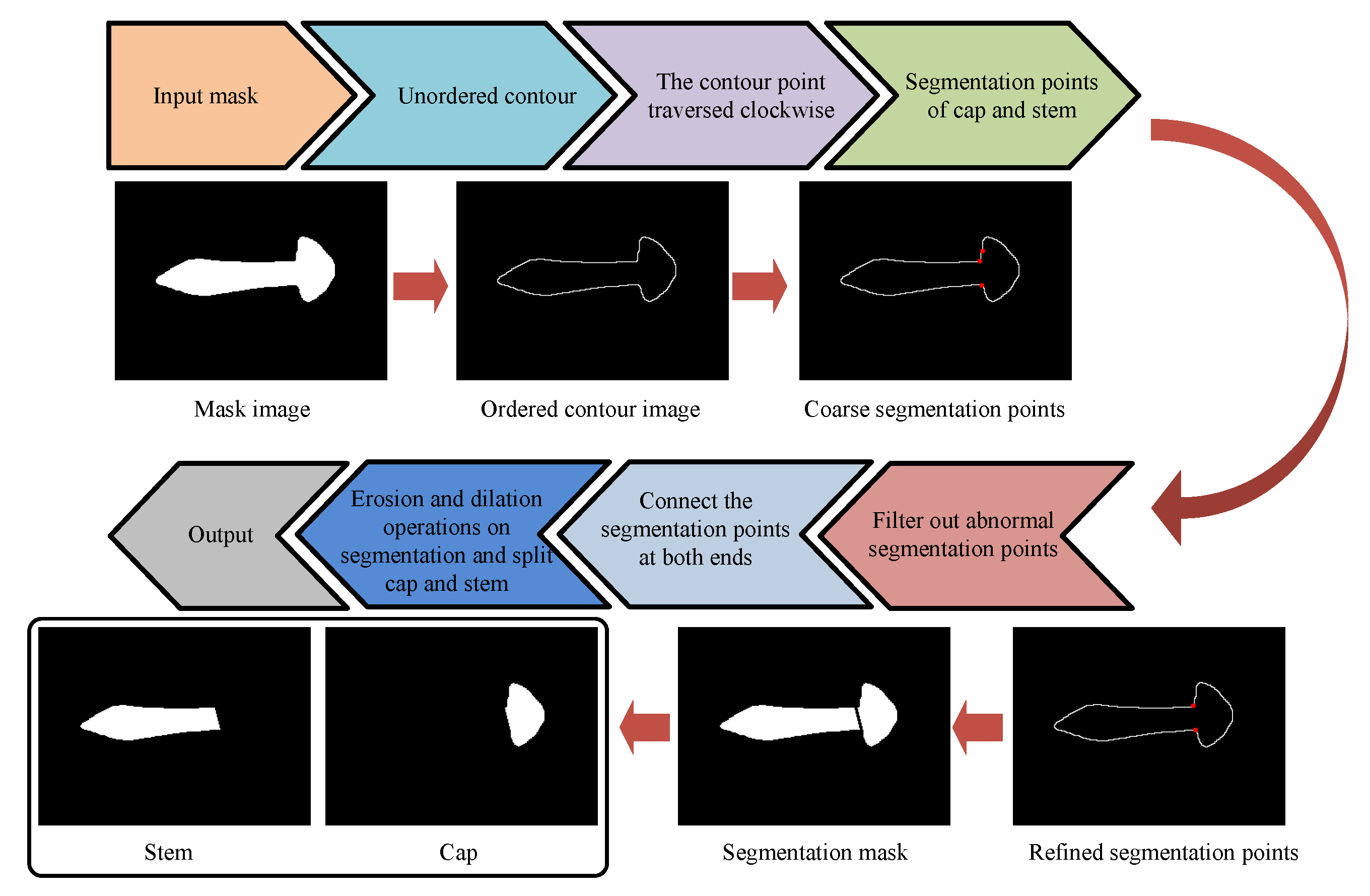

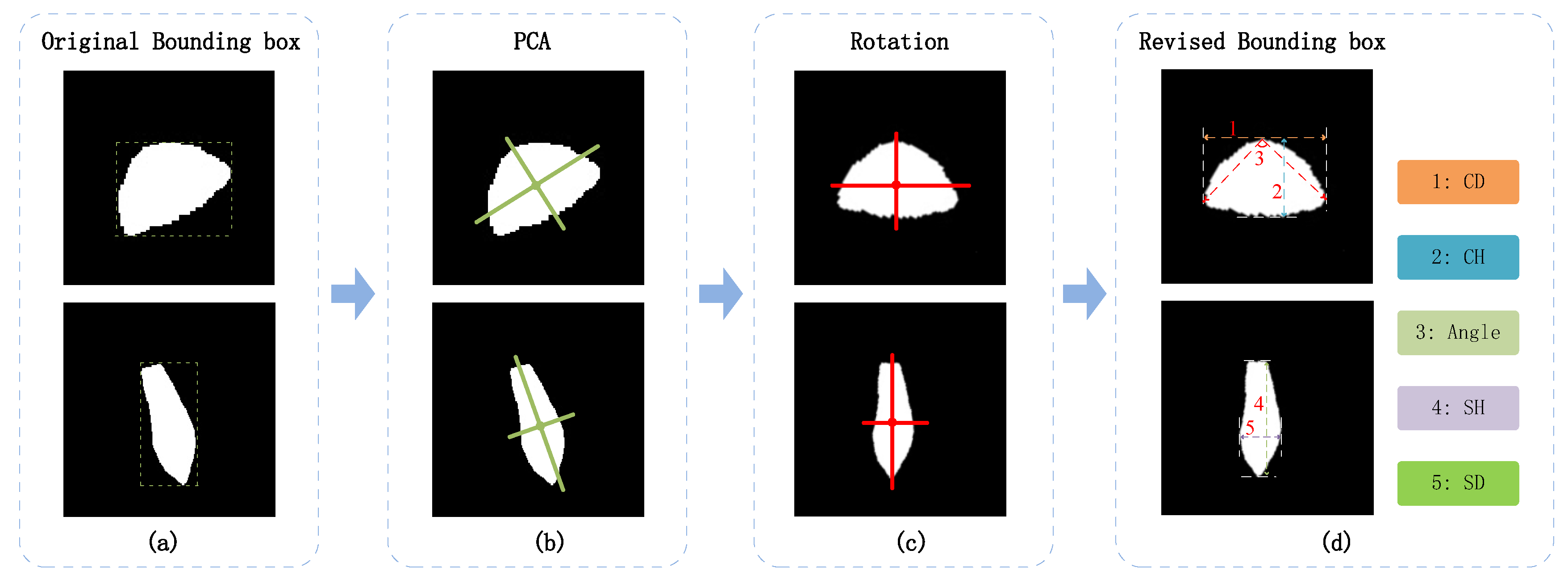

2.2.2. Shape Prior-Based Phenotypic Extraction Algorithm

| ID | Phenotypic parameters |

Equations | Units |

| 1 | CD | mm | |

| 2 | SD | mm | |

| 3 | CH | mm | |

| 4 | SH | mm | |

| 5 | - | ||

| 6 | - | ||

| 7 | mm | ||

| 8 | mm | ||

| 9 | |||

| 10 | |||

| 11 | - | ||

| 12 | - | ||

| 13 | - | ||

| 14 | - | ||

| 15 | - | ||

| 16 | mm | ||

| 17 | mm | ||

| 18 | |||

| Note: the coordinate () represented the cap (stem / fruit body) mask; the was the area of the convex hull of the cap (stem) mask. | |||

2.2.3. Mass Estimation Model

2.2.4. Implementation Details

2.2.5. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Overall Performance of Our Method

3.2 The Results of Instance Segmentation

3.2.1. Performance of Model

3.2.2. Ablation Experiment

3.2.3. Comparison Results of Different Instance Segmentation Models

3.3. The Result of Phenotypic Parameter Extraction

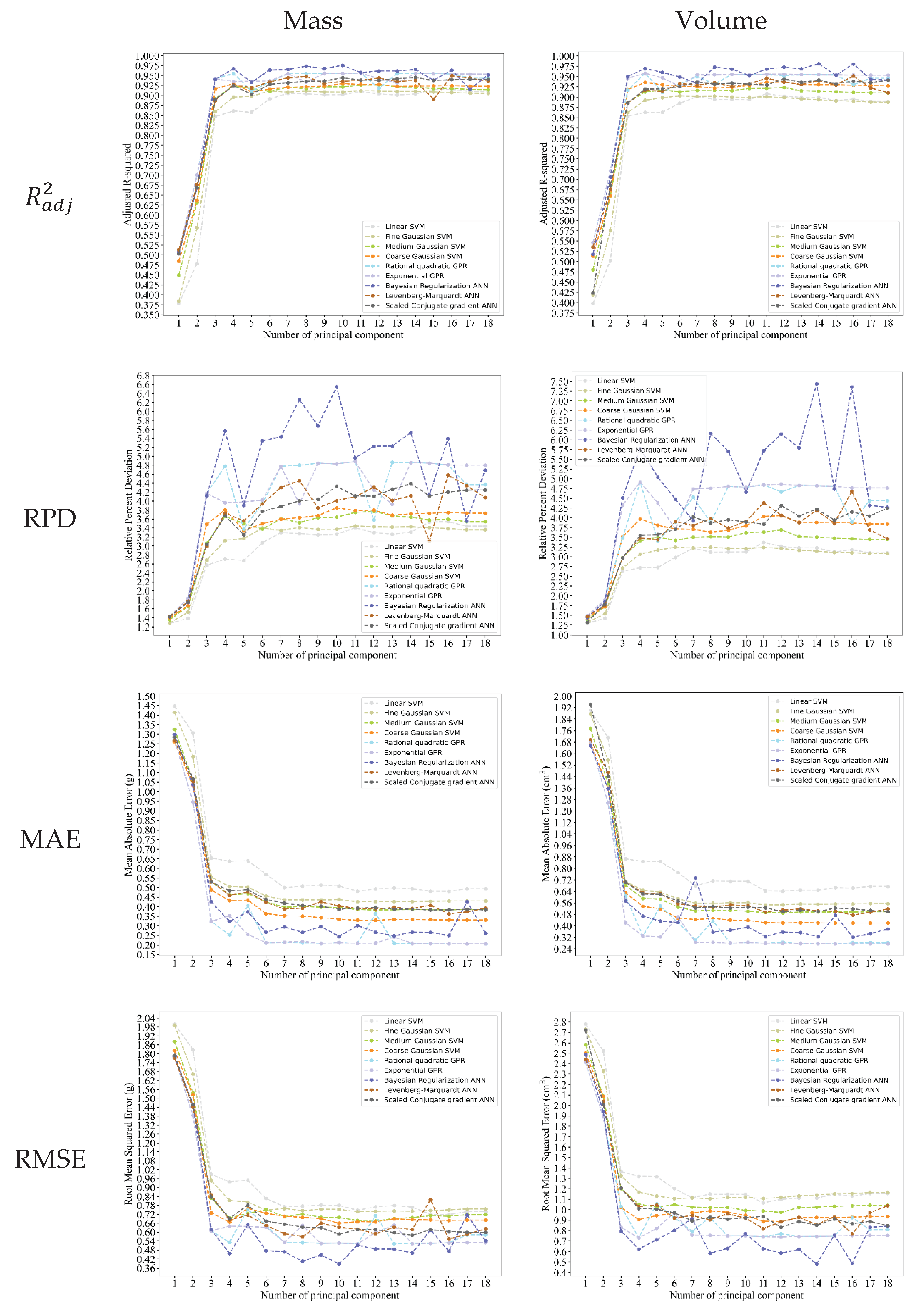

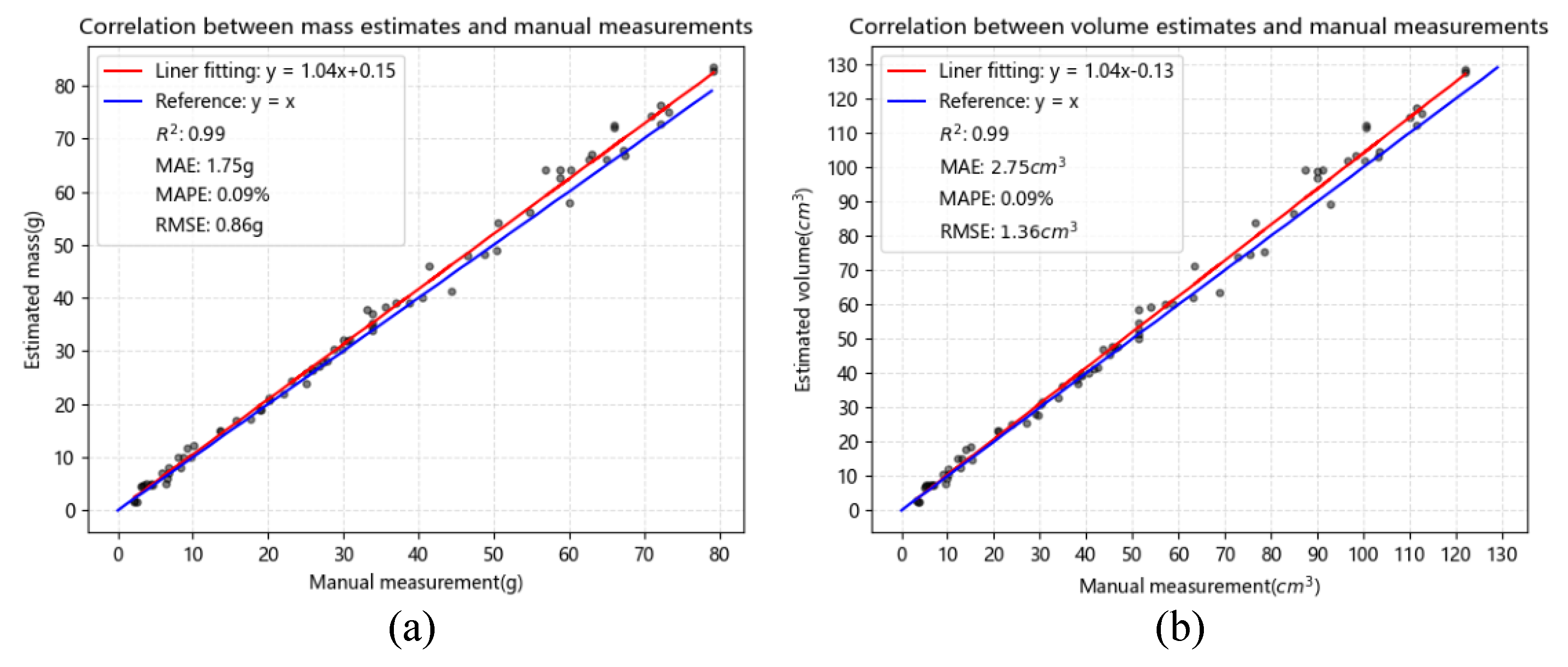

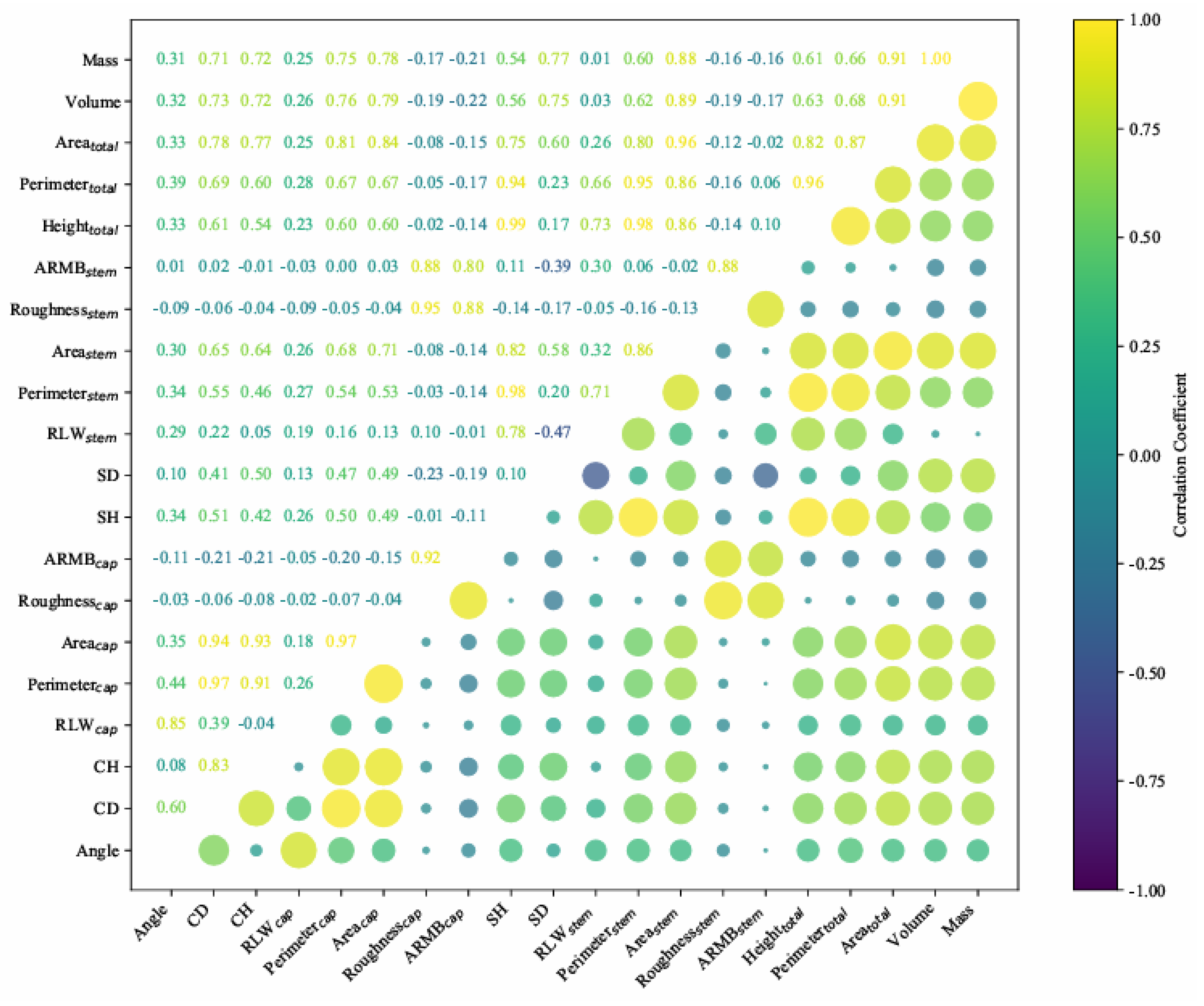

3.4. Correlation Analysis and Best Regression Model Selection

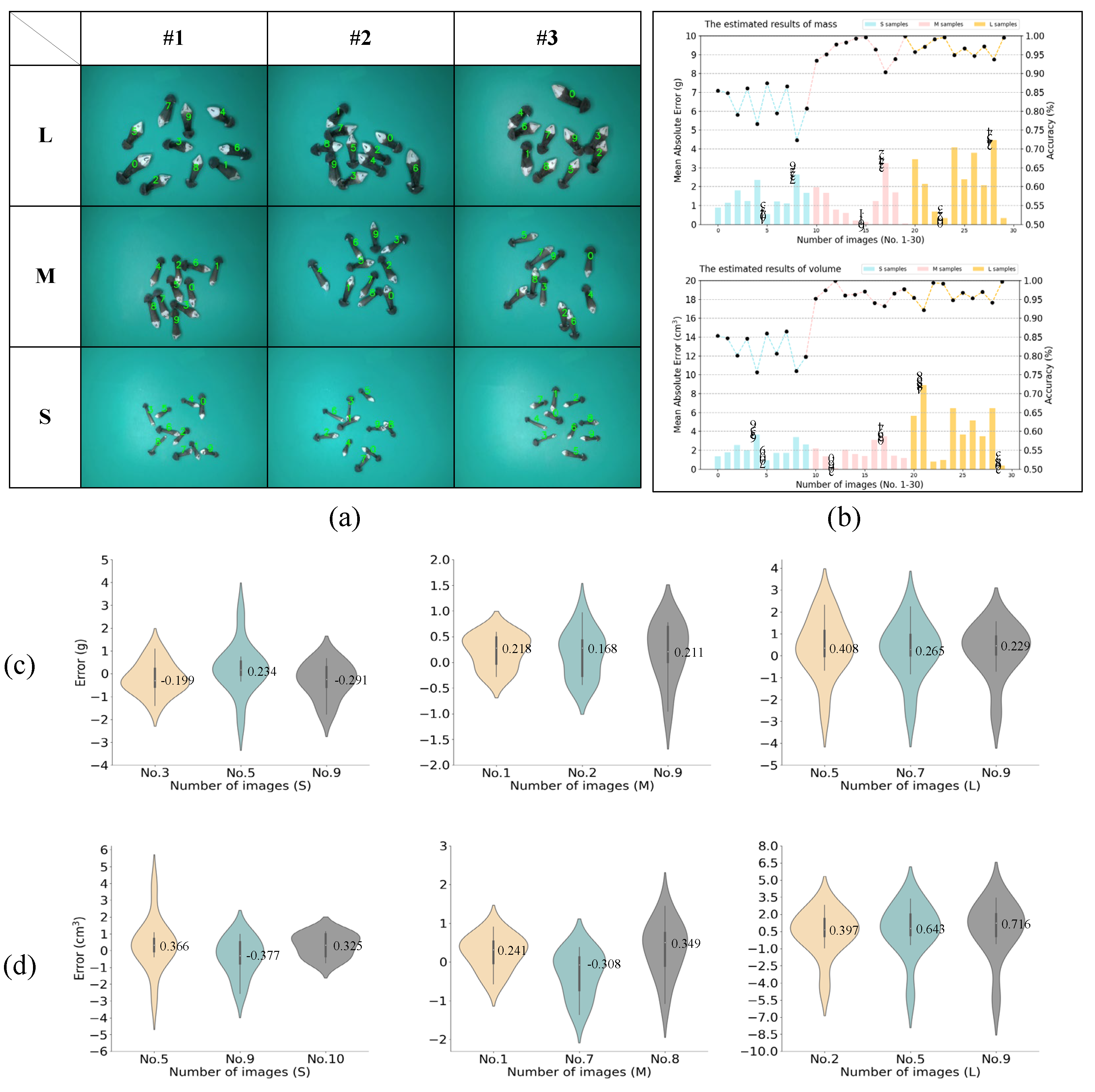

3.5. The results Under Different Conditions

3.5.1. Estimation Results of Single Sample at Random States

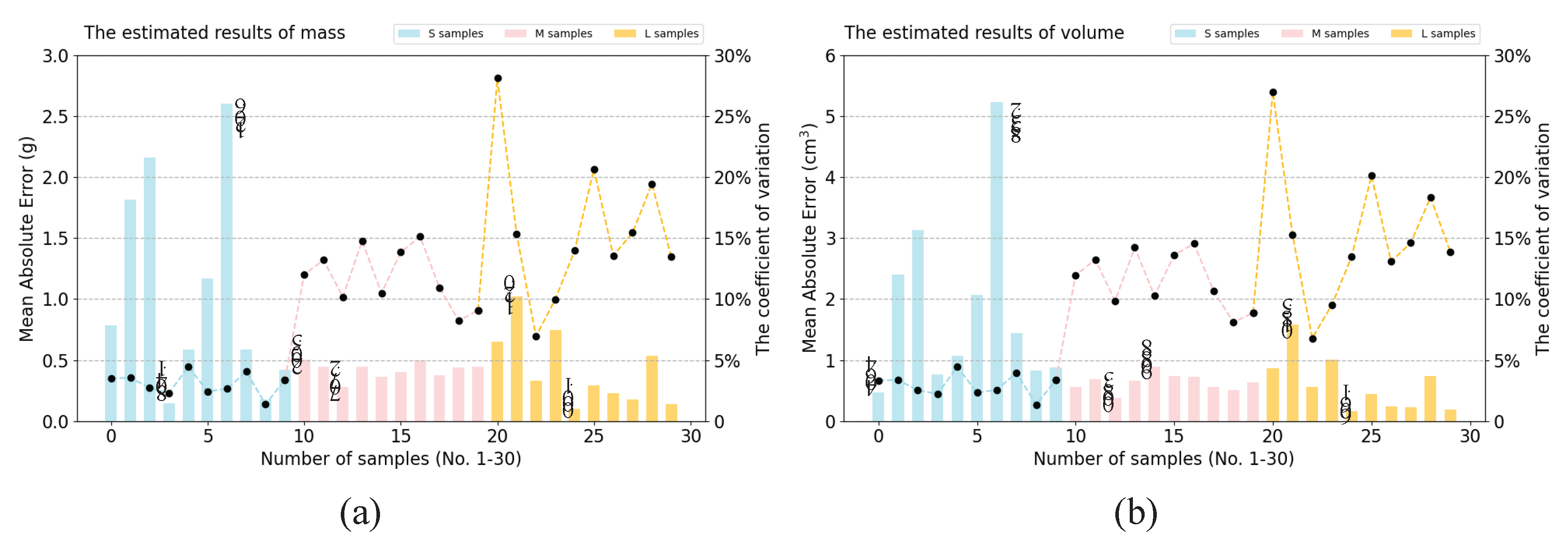

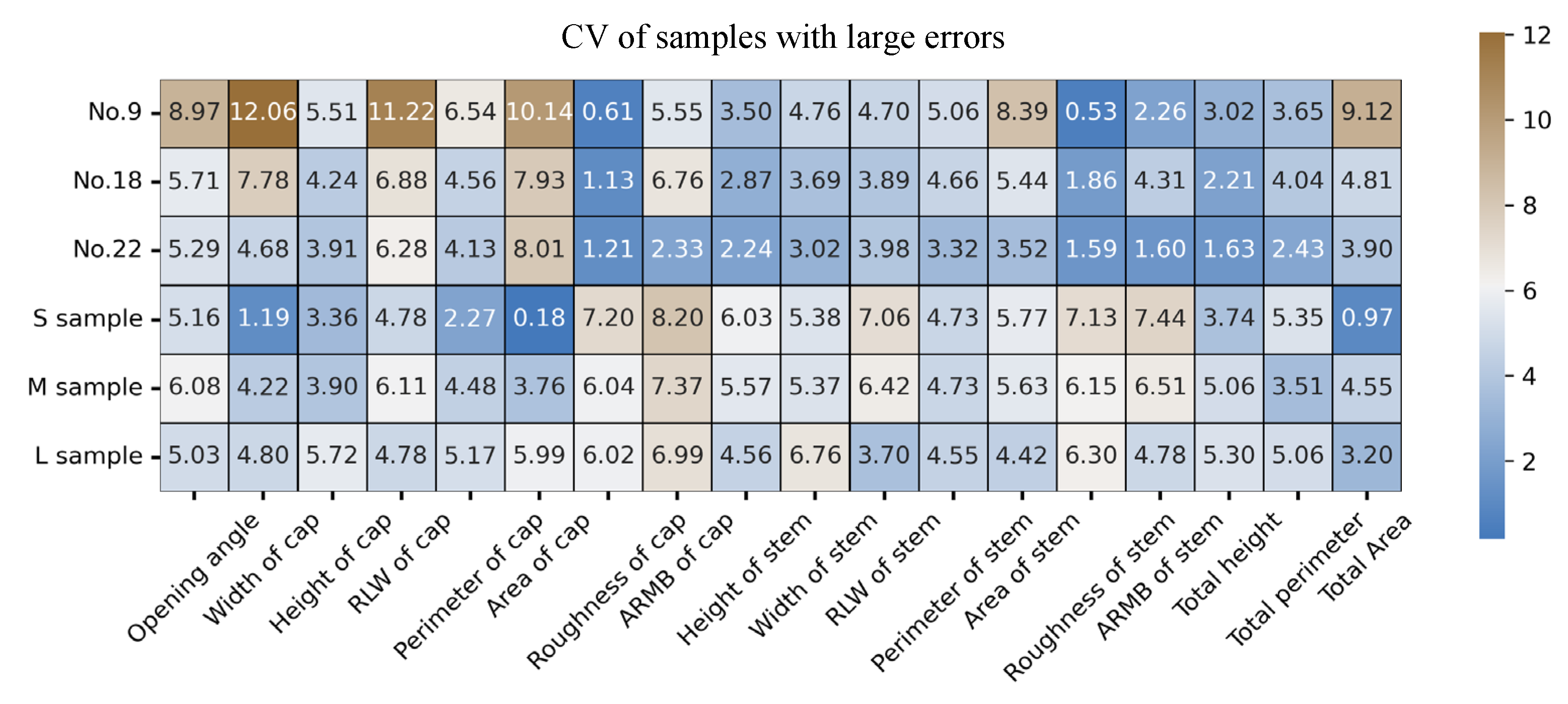

3.5.2. Estimation Results of Multiple Samples on One Image at Random States

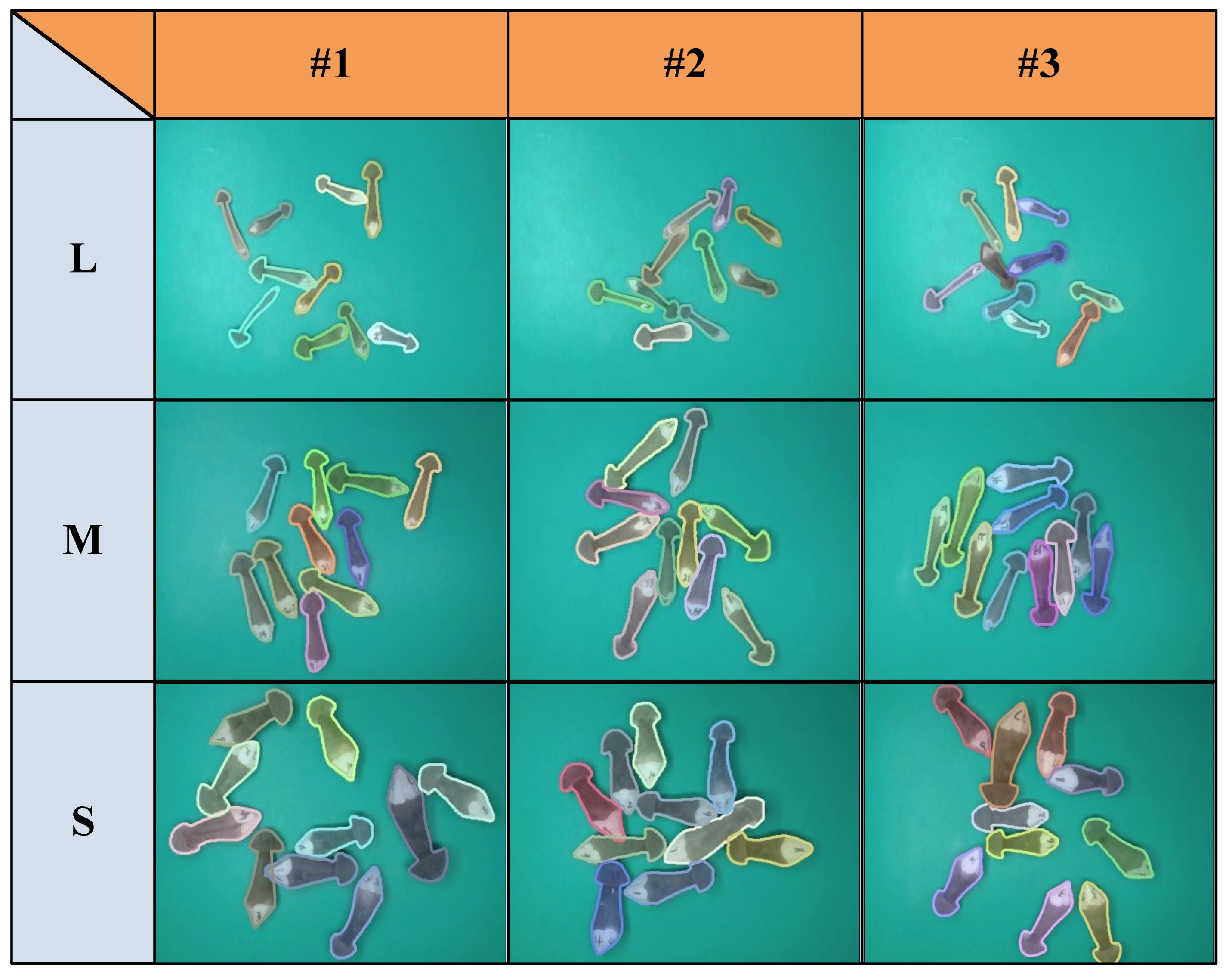

3.5.3. Comparison Results of Samples at Different Grades

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yin, H.; Yi, W.; Hu, D. Computer vision and machine learning applied in the mushroom industry: A critical review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107015. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Xu, J. ; Wang, Y.; Hu, D.; Yi, W. A novel method of situ measurement algorithm for Oudemansiella Raphanipies caps based on YOLOv4 and distance filtering. Agronomy. 2022, 13, 134. [CrossRef]

- Koc, A.B. Determination of watermelon volume using ellipsoid approximation and image processing. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2007, 45(3), 366-371. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.M.; Gopal, A.; Sarma, A. Volume estimation of apple fruits using image processing. 2011 International Conference on Image Information Processing. 2011, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Siswantoro, J.; Hilman, M.; Widiasri, M. Computer vision system for egg volume prediction using backpropagation neural network. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2017, 273, 012002.

- Widiasri, M.; Santoso, L.P.; Siswantoro, J. Computer Vision System in Measurement of the Volume and Mass of Egg Using the Disc Method. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2019, 703, 012050.

- Siswantoro, J.; Asmawati, E.; Siswantoro, M.Z. A rapid and accurate computer vision system for measuring the volume of axi-Symmetric natural products based on cubic spline interpolation. Journal of Food Engineering. 2022, 333, 111139. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; Tran, L. ; Dao, S. Real-time size and mass estimation of slender axi-Symmetric fruit/vegetable using a single top view image. Sensors. 2020, 20, 5406. [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaeefar, A.; Rajabipour, A. Modeling the mass of apples by geometrical attributes. Scientia Horticulturae. 2005, 105, 373-382. [CrossRef]

- Lorestani, A.N.; Tabatabaeefar, A. Modelling the mass of kiwi fruit by geometrical attributes. Scientia Horticulture. 2006, 105:373-382.

- Lee, J.; Nazki, H.; Baek, J., Hong; Y., Lee, M. Artificial intelligence approach for tomato detection and mass estimation in precision agriculture. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 9138. [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; Moon, S.P.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.-H. Development of potato mass estimation system based on deep learning. Applied sciences. 2023, 13, 2614. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pp. 2017, 2961-2969. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Feng, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Ru, M.; Xu, L. Yolactfusion: an Instance segmentation method for rgb-nir multimodal image fusion based on an attention mechanism. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108186. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Kong, T.; Li, L.; Shen, C. Solov2: dynamic and fast Instance segmentation. Advances in Neural information processing systems. 2020, 33, 17721-17732.

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y. ; Cao, Y. ; Hu, H. ; Wei, Y. ; Zhang, Z. ; Lin, S. ; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 2021, 10012-10022. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zheng, L. ; Yang, H.; Zhang, M.; Wu, T.; Sun, S.; Tomasetto, F.; Wang, M. A synthetic datasets based instance segmentation network for high-throughput soybean pods phenotype investigation. Expert systems with applications. 2022, 192, 116403. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yan, Z.; Guo, Y.; Su, X.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, B.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xin, D.; Chen, Q. Spm-Is: An auto-algorithm to acquire a mature soybean phenotype based on instance segmentation. The Crop Journal. 2022, 10, 1412-1423. [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Ahmed, D.; Karkee, M. Comparing YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN for instance segmentation in complex orchard environments. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture. 2024, 13, 84-99. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Chen, H.; Ma, R.; Qi, L. Towards end-to-end rice row detection in paddy fields exploiting two-pathway instance segmentation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109963. [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Ma, X.; Guan, H. A calculation method of phenotypic traits of soybean pods based on image processing technology. Ecological Informatics. 2022, 69, 101676. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Huang, S. ; New, Y. ; Xu, S. Automated detection research for number and key phenotypic parameters of rapeseed silique. Chinese Journal of Oil Crop Sciences. 2020, 42. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Y.; Gu, Q.; Jin, Q.; Zheng, K. High-throughput phenotyping collection and analysis of Flammulina Filiformis based on image recognition technology. Myco. 2021, 40, 3. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Gupta, S.; Gao, X.Z.; Singh, A. Plant species recognition using morphological features and adaptive boosting methodology. IEEE ACCESS. 2019, 7, 163912-163918. [CrossRef]

- Okinda, C.; Sun, Y.; Nyalala, I.; Korohou, T.; Opiyo, S.; Wang, J.; Shen, M. Egg volume estimation based on image processing and computer vision. Journal of Food Engineering. 2020, 283, 110041. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Yin, H.; Luo, S.; Le, Y.; Wan, J. Measurement of morphology of Oudemansiella Raphanipes based on RGBD camera. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Trans. Chinese Soc. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 140-148. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Wei, Q.; Gao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y. Moving toward smart breeding: A robust amodal segmentation method for occluded Oudemansiella Raphanipes cap size estimation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108895. [CrossRef]

- Nyalala, I.; Okinda, C.; Nyalala, L.; Makange, N.; Chao, Q.; Chao, L.; Yousaf, K.; Chen, K. Tomato volume and mass estimation using computer vision and machine learning algorithms: Cherry Tomato Model. Journal of Food Engineering. 2019, 263, 288-298. [CrossRef]

- Saikumar, A.; Nickhil, C.; Badwaik, L.S.; Physicochemical characterization of elephant apple (Dillenia Indica L.) fruit and its mass and volume modeling using computer vision. Scientia Horticulturae. 2023, 314, 111947. [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Wu, Y.; He, K.; Girshick, R. Pointrend: Image segmentation as rendering. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2020, 9799-9808. https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.08193.

- Chen, L.; Chu, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Simple baselines for image restoration. European conference on computer vision, pp. 2022, 17-33. [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning. 1995, 20, 273-297. [CrossRef]

- Nyalala, I.; Okinda, C.; Nyalala, L.; Makange, N.; Chao, Q.; Chao, L.; Yousaf, K.; Chen, K. Tomato volume and mass estimation using computer vision and machine learning algorithms: Cherry tomato model. Journal of Food Engineering. 2019, 263, 288-298. [CrossRef]

- Quinonero-Candela, J.; Rasmussen, C.E.; Williams, C.K. Approximation methods for gaussian process regression. Large-Scale Kernel Machines, MIT Press, pp. 2007, 203-223.

- Gonzalez, B.; Garcia, G.; Velastin, S.A.; GholamHosseini, H.; Tejeda, L.; Farias, G. Automated food weight and content estimation using computer vision and AI algorithms. Sensors. 2024, 24, 7660. [CrossRef]

- Sofwan, A.; Sumardi, S.; Ayun, K.Q.; Budiraharjo, K.; Karno, K. Artificial neural network levenberg-marquardt method for environmental prediction of smart greenhouse. 2022 9th International Conference on Information Technology, Computer, and Electrical Engineering (ICITACEE), pp. 2022, 50-54. [CrossRef]

- Sivaranjani, T.; Vimal, S.; AI method for improving crop yield prediction accuracy using ANN. Computer Systems Science & Engineering. 2023, 47. [CrossRef]

- Kayabaşı, A.; Sabancı, K.; Yiğit, E.; Toktaş, A.; Yerlikaya, M.; Yıldız, B. Image processing based ANN with bayesian regularization learning algorithm for classification of wheat grains. 2017 10th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ELECO). 2017, 1166-1170.

- Amraei, S.; Abdanan M.S.; Salari, S. Broiler weight estimation based on machine vision and artificial neural network. British poultry science. 2017, 58, 200-205. [CrossRef]

- Akbarian, S.; Xu, C.; Wang, W.; Ginns, S.; Lim, S. Sugarcane yields prediction at the row level Using a novel cross-validation approach to multi-Year multispectral images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107024. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.I.; Min, S.G.; Yang, J.H.; Eun, J.B.; Chung, Y.B. Mass and volume estimation of diverse kimchi cabbage forms using RGB-D vision and machine learning. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2024, 218, 113130. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.I.; Min, S.G.; Yang, J.H.; Lee, M.A.; Park, S.H.; Eun, J.B.; Chung, Y.B. Predictive modeling and mass transfer kinetics of tumbling-assisted dry salting of kimchi cabbage. Journal of Food Engineering. 2024, 361, 111742. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Feng, Z.; Ji, S.; Cui, D. Simultaneous prediction of peach firmness and weight using vibration spectra combined with one-dimensional convolutional neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 201, 107341. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wei, S.; Zheng, Z.; Chang, Z.; Yang, D.; Developing a stacked ensemble model for predicting the mass of fresh carrot. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2022, 186, 111848. [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Tang, J.; Peng, J.; Yin, H.;. A novel approach for measuring the volume of pleurotus eryngii based on depth camera and improved circular disk method. Scientia Horticulturae. 2024, 336, 113382. [CrossRef]

| Models | Kernel equations |

| Linear SVM | |

| Fine Gaussian SVM Medium Gaussian SVM Coarse Gaussian SVM |

|

| Rational Quadratic GPR | |

| Exponential GPR | |

| Bayesian Regularization ANN | n-11-2 layers |

| Levenberg-Marquardt ANN | n-11-2 layers |

| Scaled Conjugate gradient ANN | n-11-2 layers |

| Note: σ is the dimensional feature-space scale, is the decay exponent, is the length scale. | |

| Tasks | Evaluation metrics | Equations |

| Instance segmentation | The average precision () |

|

| Note: TP represents the number of samples that the model correctly predicted as positive examples, FP represents the number of samples that the model wrongly predicted as positive examples, and FN represents the number of samples that the model wrongly predicted as negative examples. | ||

| Phenotypic parameter extraction | Mean absolute error (MAE) | |

| Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) | ||

| Note: the n refers to the number of samples, represent the manual measurements, and the represent the estimated measurements. | ||

| Regression model | Adjusted () |

|

| Ratio of performance to deviation (RPD) |

|

|

| Mean absolute error (MAE) | ||

| Root mean square error () | ||

| Note: the n refers to the number of samples, represents the number of independent variables, represent the manual measurements, and the represent the estimated measurements. | ||

| Mass evaluation under different conditions | Mean absolute percentage error () | |

| Coefficient of variation () |

|

|

| Note: the n refers to the number of samples, represent the manual measurements, and the represent the estimated measurements, represent the average predicted values. | ||

| ID | PointRend | NAF | AP | AP50 | AP75 | APs |

| 1 | - | - | 0.811 | 0.977 | 0.911 | 0.857 |

| 2 | √ | - | 0.813 | 0.975 | 0.921 | 0.843 |

| 3 | - | √ | 0.814 | 0.976 | 0.935 | 0.855 |

| 4 | √ | √ | 0.831 | 0.984 | 0.930 | 0.860 |

| Method | AP | AP50 | AP75 | APs |

| Mask R-CNN | 0.811 | 0.977 | 0.911 | 0.857 |

| SOLOv2 | 0.818 | 0.973 | 0.917 | 0.857 |

| YOLACT | 0.655 | 0.937 | 0.740 | 0.730 |

| Mask2former | 0.831 | 0.969 | 0.908 | 0.864 |

| TensorMask | 0.798 | 0.966 | 0.908 | 0.830 |

| Mask R-CNN with swin | 0.829 | 0.977 | 0.960 | 0.857 |

| InstaBoost | 0.760 | 0.965 | 0.874 | 0.792 |

| FinePoint-ORSeg | 0.831 | 0.984 | 0.930 | 0.860 |

| Parameter | Number | (mm) | (mm) | MAE (mm) | MAPE (%) |

| CD | 1 | 14.9 | 16.88 | 1.98 | 13.26 |

| 2 | 20.6 | 21.88 | 1.28 | 6.19 | |

| 3 | 19.5 | 18.75 | 0.75 | 3.85 | |

| 4 | 20.9 | 21.25 | 0.35 | 1.68 | |

| 5 | 21.4 | 21.88 | 0.48 | 2.22 | |

| 6 | 22.1 | 23.75 | 1.67 | 7.47 | |

| 7 | 25.3 | 25.00 | 0.30 | 1.29 | |

| 8 | 20.2 | 22.50 | 2.30 | 11.39 | |

| 9 | 23.7 | 24.38 | 0.68 | 2.85 | |

| 10 | 25.9 | 26.25 | 0.35 | 1.35 | |

| Average | 21.45 | 22.25 | 1.01 | 5.16 | |

| CH | 1 | 12.7 | 12.50 | 0.20 | 1.58 |

| 2 | 14.6 | 16.25 | 1.65 | 11.30 | |

| 3 | 14.0 | 13.75 | 0.25 | 1.79 | |

| 4 | 15.8 | 16.88 | 1.08 | 6.80 | |

| 5 | 15.5 | 15.63 | 0.13 | 0.80 | |

| 6 | 17.8 | 19.38 | 1.58 | 8.85 | |

| 7 | 15.4 | 15.63 | 0.23 | 1.46 | |

| 8 | 13.1 | 14.38 | 1.28 | 9.73 | |

| 9 | 15.2 | 15.63 | 0.43 | 2.80 | |

| 10 | 12.1 | 12.50 | 0.44 | 3.65 | |

| Average | 14.62 | 15.25 | 0.73 | 4.88 | |

| SD | 1 | 39.1 | 39.38 | 0.28 | 0.70 |

| 2 | 30.9 | 30.63 | 0.28 | 0.89 | |

| 3 | 36.5 | 38.13 | 1.63 | 4.45 | |

| 4 | 41.8 | 43.13 | 1.33 | 3.17 | |

| 5 | 58.6 | 61.88 | 3.28 | 5.59 | |

| 6 | 33.7 | 33.75 | 0.05 | 1.48 | |

| 7 | 33.6 | 30.00 | 3.60 | 10.71 | |

| 8 | 33.1 | 31.25 | 1.85 | 5.59 | |

| 9 | 32.7 | 33.13 | 0.43 | 1.30 | |

| 10 | 37.16 | 36.88 | 0.29 | 0.77 | |

| Average | 37.72 | 37.82 | 1.30 | 3.47 | |

| SH | 1 | 13.1 | 13.75 | 0.65 | 4.96 |

| 2 | 14.9 | 15.63 | 0.725 | 4.87 | |

| 3 | 18.5 | 18.75 | 0.25 | 1.35 | |

| 4 | 18.8 | 19.38 | 0.575 | 3.06 | |

| 5 | 17.5 | 18.13 | 0.625 | 3.57 | |

| 6 | 17.8 | 18.75 | 0.95 | 5.34 | |

| 7 | 12.1 | 11.88 | 0.225 | 1.86 | |

| 8 | 18.1 | 18.75 | 0.65 | 3.59 | |

| 9 | 15.9 | 16.25 | 0.35 | 2.20 | |

| 10 | 18.0 | 18.75 | 0.75 | 4.17 | |

| Average | 16.47 | 17.00 | 0.58 | 3.50 |

|

ID |

Mass | Volume | |||||||||

| Ref (g) | APV (g) | MAE (g) | STD (g) | CV (%) | Ref (cm3) | APV (cm3) | MAE (cm3) | STD (cm3) | CV (%) | ||

| 1 | 3.23 | 3.10 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 5.42 | 4.28 | 4.32 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 7.31 | |

| 2 | 2.20 | 2.15 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 7.92 | 3.04 | 2.93 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 7.62 | |

| 3 | 3.21 | 3.20 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 7.92 | 4.25 | 4.46 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 6.81 | |

| 4 | 3.36 | 3.10 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 9.13 | 4.29 | 4.43 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 5.25 | |

| 5 | 2.37 | 2.45 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 7.59 | 3.55 | 3.46 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 8.16 | |

| 6 | 2.53 | 2.40 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 8.27 | 3.34 | 3.46 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 7.26 | |

| 7 | 2.95 | 2.40 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 4.12 | 3.96 | 3.51 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 3.09 | |

| 8 | 2.72 | 2.70 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 3.84 | 3.45 | 3.65 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 7.02 | |

| 9 | 3.10 | 2.93 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 13.34 | 4.38 | 4.66 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 12.37 | |

| 10 | 3.31 | 3.43 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 3.37 | 4.35 | 4.81 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 2.21 | |

| 11 | 2.92 | 2.57 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 5.40 | 4.20 | 3.70 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 3.95 | |

| 12 | 3.11 | 2.95 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 9.57 | 4.25 | 4.24 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 8.84 | |

| 13 | 3.25 | 2.74 | 0.51 | 0.16 | 5.86 | 4.25 | 4.13 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 7.13 | |

| 14 | 3.08 | 3.08 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 5.03 | 4.24 | 4.29 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 6.67 | |

| 15 | 2.17 | 2.27 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 9.69 | 2.98 | 3.31 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 7.99 | |

| 16 | 3.06 | 2.96 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 4.46 | 4.51 | 4.56 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 5.22 | |

| 17 | 2.35 | 2.12 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 5.71 | 3.37 | 3.29 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 7.01 | |

| 18 | 2.98 | 2.70 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 11.88 | 4.01 | 3.85 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 13.21 | |

| 19 | 2.25 | 2.34 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 3.45 | 3.16 | 3.34 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 9.79 | |

| 20 | 3.34 | 3.12 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 9.17 | 4.25 | 4.51 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 6.61 | |

| 21 | 3.40 | 2.54 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 6.99 | 4.70 | 4.03 | 0.67 | 0.20 | 4.98 | |

| 22 | 3.35 | 3.29 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 3.47 | 4.72 | 4.93 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 4.94 | |

| 23 | 3.17 | 3.05 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 4.85 | 4.64 | 4.36 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 4.94 | |

| 24 | 3.29 | 3.29 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 6.90 | 4.46 | 4.46 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 8.12 | |

| Average | 2.95 | 2.79 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 6.81 | 4.03 | 4.03 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 6.94 | |

| Grade | Total | ||||

| S | M | L | |||

| Number of images | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 | |

| Mass | RMSE () | 0.590 | 0.493 | 1.323 | 0.802 |

| MAE (g) | 1.454 | 1.323 | 2.367 | 1.714 | |

| MAPE (%) | 18.17% | 4.22% | 3.21% | 8.53% | |

| Volume | RMSE () | 0.835 | 0.757 | 2.327 | 1.306 |

| MAE () | 2.140 | 1.796 | 4.713 | 2.703 | |

| MAPE (%) | 17.94% | 3.77% | 3.66% | 8.46% | |

| Grade | Total | ||||

| S | M | L | |||

| Number of samples | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 | |

| Mass | RMSE () | 0.390 | 0.494 | 1.083 | 0.656 |

| MAE (g) | 0.422 | 0.421 | 1.045 | 0.629 | |

| MAPE (%) | 48.62% | 12.76% | 13.97% | 25.12% | |

| Volume | RMSE () | 0.556 | 0.752 | 1.884 | 1.064 |

| MAE () | 0.601 | 0.634 | 1.830 | 1.022 | |

| MAPE (%) | 44.89% | 12.76% | 15.18% | 24.28% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).