Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Vulnerability of the Meat Industry

1.2. Drivers of Meat Loss and Waste Across Economies

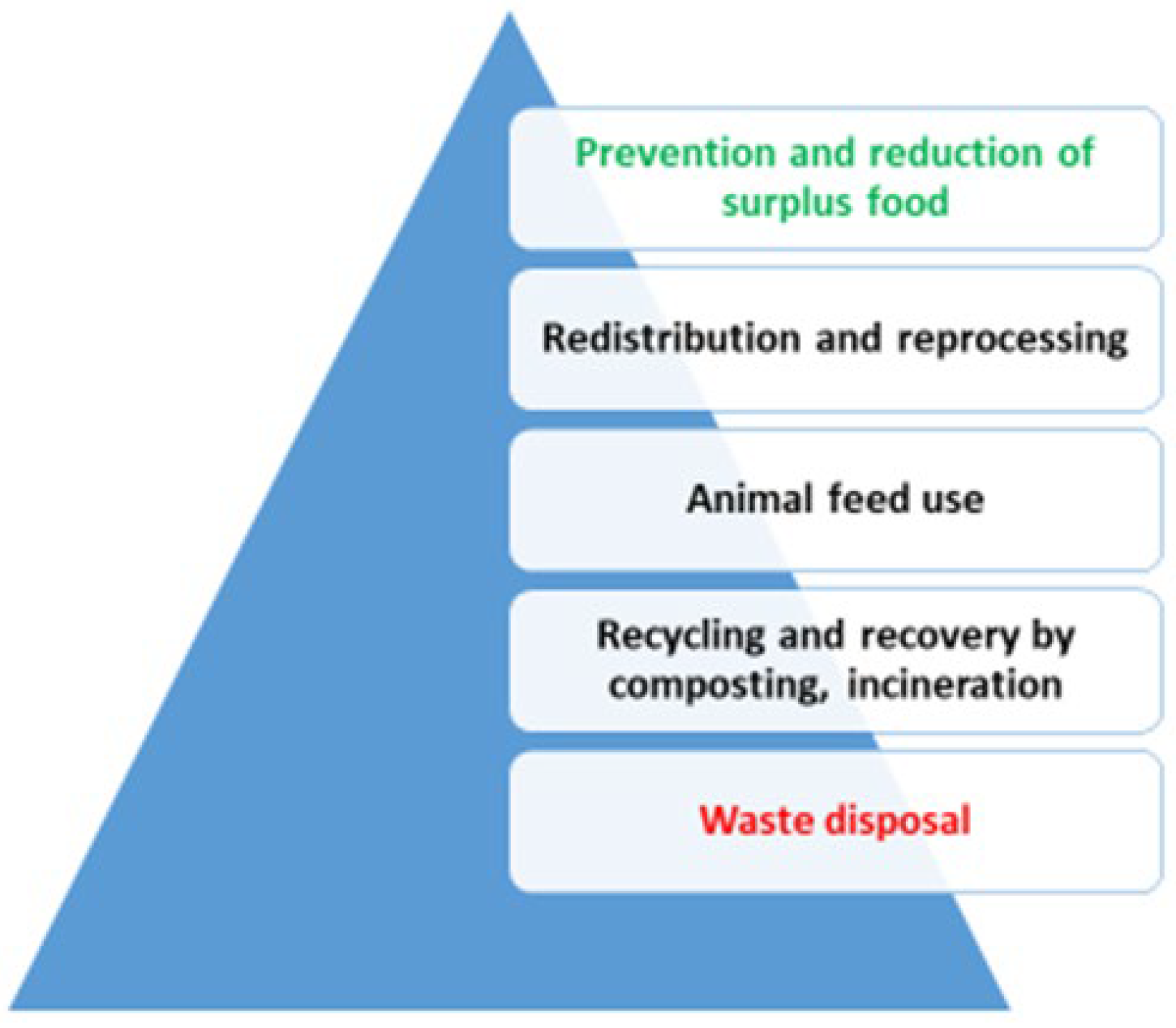

1.3. Understanding FLW Through the Food Waste Hierarchy

1.4. Integrating Preservation Technologies to Reduce Meat Losses and Waste

2. Research Methodology

3. Extent and Relevance of Meat Losses and Waste

3.1. Global Significance of Meat Losses and Waste

3.2. Extent of Losses Across the Supply Chain

- ○

- Production and slaughterhouses: Carcass rejection due to sanitary issues, anatomical defects, or processing inefficiencies can result in losses of 2–5% at the slaughter stage. In developing countries, limited access to adequate slaughter facilities exacerbates these problems.

- ○

- Processing and logistics: Maintaining the cold chain is a major determinant of meat quality. Interruptions during storage or transport create opportunities for microbial growth and spoilage, leading to economic downgrading or outright rejection of products.

- ○

- Retail stage: Overstocking, inaccurate demand forecasting, and rigid product presentation standards are common drivers of loss. For example, meat approaching its expiration date is frequently discarded despite being safe for consumption.

- ○

- Consumers: In high-income countries, households are the single largest contributors to meat waste, primarily due to over-purchasing, inadequate storage, and misunderstanding of “best before” versus “use by” labels. In contrast, in low- and middle-income countries, infrastructural deficits such as unreliable refrigeration, weak transport logistics, and limited cold storage capacity dominate upstream losses.

3.3. Mass Balance Perspective

- ○

- Beef: On average, only 60–70% of a carcass is converted into prime meat cuts. The remainder includes hides, bones, fat, blood, and offal. While some these by-products are processed into secondary products, others remain underused or discarded.

- ○

- Pork: Utilization rates are typically higher (75–80%), due to broader acceptance of processed cuts and by-products in many culinary traditions.

- ○

- Poultry: Carcass yields hover around 70%, with feathers, viscera, and bones. Often a practical example is the breakdown of a 600 kg beef carcass: roughly 370 kg is transformed into edible cuts, while about 230 kg consists of materials that, if not valorized, represent both economic loss and environmental burden. From this perspective, meat loss is not only visible spoilage but also insufficient valorization of non-prime fractions.

3.4. Sustainability Implications and LCA Evidence

- ○

- The environmental consequences of meat loss and waste are among the most severe in the food sector. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) consistently demonstrates that meat—particularly beef—has one of the highest carbon footprints per kilogram of edible product [37].

- ○

- Carbon footprint: Wasted beef generates approximately 27 kg CO₂-eq per kilogram of discarded product, compared with 7–12 kg for pork and 5–6 kg for poultry.

- ○

- Water footprint: Producing 1 kg of beef may require up to 15,000 liters of water (including virtual water for feed crops). The loss of such products therefore represents a substantial inefficiency in freshwater use.

- ○

- Energy footprint: Case studies from Germany report that discarding one ton of pork sausages at the retail stage results in more than 6 MWh of embodied energy loss, excluding additional emissions associated to packaging and refrigeration [38].

3.5. Critical Action Points and Optimization Potential

- ○

- Despite the scale of the problem, several critical intervention points remain underexploited.

- ○

- Valorization of by-products: Significant potential exists in the utilization of blood, fat, bones, skin, and viscera. These materials can be converted into high-value outputs such as collagen, gelatin, biofertilizers, biogas, nutraceutical ingredients, and pharmaceutical precursors. Barriers include cultural aversions, strict sanitary regulations, and logistical challenges yet successful models are already implemented in regions such as Asia and Northern Europe.

- ○

- Shelf-life extension: Intelligent packaging solutions-including time–temperature indicators, oxygen scavengers, and antimicrobial coatings- can markedly reduce spoilage. Modified atmosphere packaging, already established in commercial practice, has extended the shelf life of chilled meat by several days. Digital supply chain management: Artificial intelligence tools are increasingly employed to predict demand, optimize stock rotation, and support dynamic pricing based on real-time freshness indicators. Retail have demonstrated reductions of up to 30% in meat waste when AI-driven pricing systems.

- ○

- Redistribution networks: Legal and logistical frameworks enabling the redistribution of surplus meat to food banks, charities, or community kitchens remain underutilized in many regions. Countries such as France and Denmark are frequently cited as best-practice examples, where legislation actively promotes redistribution.

- ○

- Consumer education: Misinterpretation of date labeling is one of the most avoidable drivers of household-level waste. Public campaigns clarifying the distinction between “use by” and “best before” dates, combined with practical guidance on meal planning and domestic refrigeration, have shown effectiveness in pilot programs.

3.6. Visualization and Communication Strategies

4. Technologies with Transformation Potential

4.1. Measures to Prevent Food Losses and Waste During the Production Stage

4.2. Measures to Prevent Food Losses and Waste During the Food Processing

4.3. Food Packaging

4.4. Identification and Assessment of Sustainable Packaging

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO: The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, (2019).

- Mezgebe, T.T., Alemu, M.: Climate change and food security nexus in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Front Sustain Food Syst. 9, 1563379 (2025).

- An, H. , Galera-Zarco, C.: Tackling food waste and loss through digitalization in the food supply chain: A systematic review and framework development. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 217, 124175 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Buzby, J.C., Farah-Wells, H., Hyman, J.: The estimated amount, value, and calories of postharvest food losses at the retail and consumer levels in the United States. (2014).

- Parfitt, J. , Barthel, M., Macnaughton, S.: Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 365, 3065-3081 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Jones-Garcia, E. , Bakalis, S., Flintham, M.: Consumer Behaviour and Food Waste: Understanding and Mitigating Waste with a Technology Probe. Foods. 11, 2048 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Seyam, A. , EI Barachi, M., Zhang, C., Du, B., Shen, J., Mathew, S.S.: Enhancing resilience and reducing waste in food supply chains: a systematic review and future directions leveraging emerging technologies. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications. 1-35 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J. , Giménez, A., Ares, G.: Household food waste in an emerging country and the reasons why: Consumer´s own accounts and how it differs for target groups. Resour Conserv Recycl. 145, 332-338 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Torres, M., Ceglar, A.: The carbon footprint of astronomical observatories, (2024).

- Grandin, T., Buhr, R.J.: Investigating the impact of pre slaughter management factors on indicators of fed beef cattle welfare – a scoping review. Frontiers in Animal Science. 4, 107384 (2022).

- Teigiserova, D.A. , Hamelin, L., Thomsen, M.: Towards transparent valorization of food surplus, waste and loss: Clarifying definitions, food waste hierarchy, and role in the circular economy. Science of The Total Environment. 706, 136033 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A. , García Ruiz, A.: Exploring incentives to move up the food waste hierarchy: A case study of circular practices in hospitality. J Clean Prod. 395, (2025).

- Huang, I.Y. , Manning, L., James, K.L., Grigoriadis, V., Millington, A., Wood, V., Ward, S.: Food waste management: A review of retailers’ business practices and their implications for sustainable value. J Clean Prod. 285, 125484 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ammann, J. , Arbenz, A., Mack, G., Nemecek, T., El Benni, N.: A review on policy instruments for sustainable food consumption. Sustain Prod Consum. 36, 338-353 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jayasena, D.D. , Kang, T., Wijayasekara, K.N., Jo, C.: Innovative Application of Cold Plasma Technology in Meat and Its Products. Food Sci Anim Resour. 43, 1087-1110 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Dodero, A. , Escher, A., Bertucci, S., Castellano, M., Lova, P.: Intelligent Packaging for Real-Time Monitoring of Food-Quality: Current and Future Developments. Applied Sciences. 11, 3532 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Goraya, R.K., Singla, M., Kaura, R., Singh, C.B., Singh, A.: Exploring the impact of high pressure processing on the characteristics of processed fruit and vegetable products: a comprehensive review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2024).

- Anyibama, J,.B., K. Orjinta, K., F. Onotole, E., A. Olalemi, A., Temitope Olayinka, O., E. Ogunwale, G., O. Fadipe, E., O. Daniels, E.: Blockchain Application in Food Supply Chains: A Critical Review and Agenda for Future Studies. Int J Innov Sci Res Technol. 2345-2352 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. : Supply Chain Viability and the COVID-19 pandemic: a conceptual and formal generalisation of four major adaptation strategies. Int J Prod Res. 59, 3535-3552 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hunka, A.D. , Daniel, A.M., Lindahl, C., Rydberg, A.: From farm to fork: Swedish consumer preferences for traceable beef attributes. Food and Humanity. 5, 100673 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Roe, S. , Streck, C., Beach, R., Busch, J., Chapman, M., Daioglou, V., Deppermann, A., Doelman, J., Emmet-Booth, J., Engelmann, J., Fricko, O., Frischmann, C., Funk, J., Grassi, G., Griscom, B., Havlik, P., Hanssen, S., Humpenöder, F., Landholm, D., Lomax, G., Lehmann, J., Mesnildrey, L., Nabuurs, G., Popp, A., Rivard, C., Sanderman, J., Sohngen, B., Smith, P., Stehfest, E., Woolf, D., Lawrence, D.: Land-based measures to mitigate climate change: Potential and feasibility by country. Glob Chang Biol. 27, 6025-6058 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Pires, I. , Machado, J., Rocha, A., Liz Martins, M.: Food Waste Perception of Workplace Canteen Users—A Case Study. Sustainability. 14, 1324 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Spang, E.S. , Moreno, L.C., Pace, S.A., Achmon, Y., Donis-Gonzalez, I., Gosliner, W.A., Jablonski-Sheffield, M.P., Momin, M.A., Quested, T.E., Winans, K.S., Tomich, T.P.: Food Loss and Waste: Measurement, Drivers, and Solutions. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 44, 117-156 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, H.M. , Pasquali, M.B., dos Anjos, A.I., Sarinho, A.M., de Melo, E.D., Andrade, R., Batista, L., Lima, J., Diniz, Y., Barros, A.: Innovative and Sustainable Food Preservation Techniques: Enhancing Food Quality, Safety, and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability. 16, 8223 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Scholten, K. , Stevenson, M., van Donk, D.P.: Dealing with the unpredictable: supply chain resilience. International Journal of Operations & Production Management. 40, 1-10 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Bajželj, B. , Quested, T.E., Röös, E., Swannell, R.P.J.: The role of reducing food waste for resilient food systems. Ecosyst Serv. 45, 101140 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, R. , Cruijssen, F.: Food Loss, Food Waste, and Sustainability in Food Supply Chains. Présenté à (2024).

- Bytyqi, H. , Ender Kunili, I., Mestani, M., Adam Antoniak, M., Berisha, K., Ozge Dinc, S., Guzik, P., Szymkowiak, A., Kulawik, P.: Consumer attitudes towards animal-derived food waste and ways to mitigate food loss at the consumer level. Trends Food Sci Technol. 159, 104898 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., Moher, D.: The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. n71 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z. , Peters, M.D.J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., Aromataris, E.: Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 18, 143 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Cisneros, M. , de Lourdes Pérez-Chabela, M., Ponce-Alquicira, E.: New Technologies in Meat Preservation. Dans: Food Processing - Novel Technologies and Practices [Working Title]. IntechOpen (2025).

- Snyder, H. : Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. 104, 333-339 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. , Clarke, V.: Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 11, 589-597 (2019). [CrossRef]

- CASP: CASP Checklists, Critical Appraisal Checklists. (2018).

- Gustavsson, J. , Cederberg, C., Sonesson, U., van Otterdijk, R., Meybeck, A.: Global food losses and food waste: Extent, causes and prevention, (2011).

- FAO: World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021, (2021).

- Poore, J. , Nemecek, T.: Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science (1979). 360, 987-992 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Commission, E. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A farm to fork strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system COM/2020/381 final, (2020).

- Taglioni, C. , Rosero Moncayo, J., Fabi, C.: Food loss estimation: SDG 12.3.1a data and modelling approach. FAO (2023).

- Kafa, N. , Jaegler, A.: Food losses and waste quantification in supply chains: a systematic literature review. British Food Journal. 123, 3502-3521 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, L.V. , Allepuz, A., Mateu, E.: Biosecurity in pig farms: a review. Porcine Health Manag. 7, 5 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Maye, D. , Chan, K.W. (Ray): On-farm biosecurity in livestock production: farmer behaviour, cultural identities and practices of care. Emerg Top Life Sci. 4, 521-530 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Poland, J. , Rutkoski, J.: Advances and Challenges in Genomic Selection for Disease Resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 54, 79-98 (2016). [CrossRef]

- KS, M. , EG, J.: Review on probiotics as a functional feed additive in aquaculture. Int J Fish Aquat Stud. 9, 201-207 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Naiel, M.A.E. , Abdelghany, M.F., Khames, D.K., Abd El-hameed, S.A.A., Mansour, E.M.G., El-Nadi, A.S.M., Shoukry, A.A.: Administration of some probiotic strains in the rearing water enhances the water quality, performance, body chemical analysis, antioxidant and immune responses of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Appl Water Sci. 12, 209 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, L. , Galiot, L., Sauvé, B., Pierre, C., Guay, F., Dumas, G., Gagnon, P., Létourneau Montminy, M.-P.: Impact of Precision Feeding During Gestation on the Performance of Sows over Three Cycles. Animals. 14, 3513 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Pomar, C. , van Milgen, J., Remus, A.: 18: Precision livestock feeding, principle and practice. Dans: Poultry and pig nutrition. p. 397-418. Brill | Wageningen Academic (2019).

- Sun, X. , Dou, Z., Shurson, G.C., Hu, B.: Bioprocessing to upcycle agro-industrial and food wastes into high-nutritional value animal feed for sustainable food and agriculture systems. Resour Conserv Recycl. 201, 107325 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mustapa, M.A.C. , Kallas, Z.: Towards more sustainable animal-feed alternatives: A survey on Spanish consumers’ willingness to consume animal products fed with insects. Sustain Prod Consum. 41, 9-20 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M. , Iqbal, M.: Enzyme supplementation in poultry diets: Implications for performance, gut health, and environmental sustainability. Poult Sci. 102, (2023).

- Cowieson, A.J. , Toghyani, M., Kheravii, S.K., Wu, S.-B., Romero, L.F., Choct, M.: A mono-component microbial protease improves performance, net energy, and digestibility of amino acids and starch, and upregulates jejunal expression of genes responsible for peptide transport in broilers fed corn/wheat-based diets supplemented with xylanase and phytase. Poult Sci. 98, 1321-1332 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, M. , Yik, S.: Precision Livestock Farming in Swine Welfare: A Review for Swine Practitioners. Animals. 9, 133 (2019). [CrossRef]

- BERCKMANS, D. : Precision livestock farming technologies for welfare management in intensive livestock systems. Revue Scientifique et Technique de l’OIE. 33, 189-196 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Da Borso, F. , Chiumenti, A., Sigura, M., Pezzuolo, A.: Influence of automatic feeding systems on design and management of dairy farms. Journal of Agricultural Engineering. 48-52 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Tullo, E. , Finzi, A., Guarino, M.: Review: Environmental impact of livestock farming and Precision Livestock Farming as a mitigation strategy. Science of The Total Environment. 650, 2751-2760 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A. , Abdollahi, A., Rejeb, K., Treiblmaier, H.: Drones in agriculture: A review and bibliometric analysis. Comput Electron Agric. 198, 107017 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jinya, L. : Genomic Selection in Livestock Breeding: Advances and Applications. Animal Molecular Breeding. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.J. : Implications of Assisted Reproductive Technologies for Pregnancy Outcomes in Mammals. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 8, 395-413 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Menchaca, A. : Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) and genome editing to support a sustainable livestock. Anim Reprod. 20, e20230074 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.P. , Sousa, F.C. de, Silva, A.L. da, Schultz, É.B., Valderrama Londoño, R.I., Souza, P.A.R. de: Heat Stress in Dairy Cows: Impacts, Identification, and Mitigation Strategies—A Review. Animals. 15, 249 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S. , Reddy, I.J.: Impact of climate change on livestock production. Dans: Singh, S.S. et Kumar, N. (éd.) Biotechnology for sustainable agriculture. p. 235-256. Elsevier (2018).

- Tahamtani, F.M. , Pedersen, I.J., Riber, A.B.: Effects of environmental complexity on welfare indicators of fast-growing broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 99, 21-29 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J. , Ngoc, T.N., ThiHanhYen, T., Mayrhofer, R., El-Matbouli, M., Focken, U.: Earthworm Meal as Fishmeal Replacement in Plant based Feeds for Common Carp in Semi-intensive Aquaculture in Rural Northern Vietnam. Turk J Fish Aquat Sci. 14, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.E. , McNevin, A.A.: Aerator energy use in shrimp farming and means for improvement. J World Aquac Soc. 52, 6-29 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Grandin, T. : Livestock handling and transport. CABI (2019).

- Terlouw, E.M.C. , Veissier, I.: Animal welfare during transport and slaughter: an issue that remains to be solved. Animal Frontiers. 12, 3-5 (2022). [CrossRef]

- González, L.A. , Faucitano, L.: Road transport of livestock: Implications for animal welfare and meat quality. Animal Frontiers. 13, 22-30 (2023).

- Wurtz, K.E. , Herskin, M.S., Riber, A.B.: Water deprivation in poultry in connection with transport to slaughter—a review. Poult Sci. 103, 103419 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. , Makridis, P., Henry, I., Velle-George, M., Ribicic, D., Bhatnagar, A., Skalska-Tuomi, K., Daneshvar, E., Ciani, E., Persson, D., Netzer, R.: Recent Developments in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems: A Review. Aquac Res. 2024, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. , Narayan, E., Rey Planellas, S., Phillips, C.J.C., Zheng, L., Xu, B., Wang, L., Liu, Y., Sun, Y., Sagada, G., Shih, H., Shao, Q., Descovich, K.: Effects of stocking density during simulated transport on physiology and behavior of largemouth bass ( Micropterus salmoides ). J World Aquac Soc. 55, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zainalabidin, F.A. , Hassan, F.M., Zin, N.S.M., Azmi, W.N.W., Ismail, M.I.: Halal System in Meat Industries. Malaysian Journal of Halal Research. 2, 1-5 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Qin, X. , Shen, Q., Guo, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, H., Jia, W., Xu, X., Zhang, C.: An advanced strategy for efficient recycling of bovine bone: Preparing high-valued bone powder via instant catapult steam-explosion. Food Chem. 374, 131614 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Mercier, S. , Villeneuve, S., Mondor, M., Uysal, I.: Time–Temperature Management Along the Food Cold Chain: A Review of Recent Developments. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 16, 647-667 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z. , Yang, J., Zhu, Y., Xu, L., Yang, S., Li, M., Zhao, L., Zhang, Y., Guo, Q., Zhao, G.: Development and design of an intelligent monitoring system for cold chain meat freshness. Food Materials Research. 3, 1-10 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Food, (FAO), A.O.: Climate change and livestock sector (1st ed., 2 pages), (2020).

- Rojas-Downing, M.M. , Nejadhashemi, A.P., Harrigan, T., Woznicki, S.A.: Climate change and livestock: Impacts, adaptation, and mitigation. Clim Risk Manag. 16, 145-163 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wisser, D. , Grogan, D.S., Lanzoni, L., Tempio, G., Cinardi, G., Prusevich, A., Glidden, S.: Water Use in Livestock Agri-Food Systems and Its Contribution to Local Water Scarcity: A Spatially Distributed Global Analysis. Water (Basel). 16, 1681 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Toldrá, F. , Mora, L., Reig, M.: New insights into meat by-product utilization. Meat Sci. 120, 54-59 (2016). [CrossRef]

- van Huis, A. , Oonincx, D.G.A.B.: The environmental sustainability of insects as food and feed. A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 37, 43 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Halloran, A. , Roos, N., Eilenberg, J., Cerutti, A., Bruun, S.: Life cycle assessment of edible insects for food protein: a review. Agron Sustain Dev. 36, 57 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Sevillano, C.A. , Pesantes, A.A., Peña Carpio, E., Martínez, E.J., Gómez, X.: Anaerobic Digestion for Producing Renewable Energy—The Evolution of This Technology in a New Uncertain Scenario. Entropy. 23, 145 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Bywater, A. , Adam, J.A.H., Kusch-Brandt, S., Heaven, S.: Co-Digestion of Cattle Slurry and Food Waste: Perspectives on Scale-Up. Methane. 4, 8 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Buzdugan, S.N. , Alarcon, P., Huntington, B., Rushton, J., Blake, D.P., Guitian, J.: Enhancing the value of meat inspection records for broiler health and welfare surveillance: longitudinal detection of relational patterns. BMC Vet Res. 17, 278 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Dongo, D. , Torre, G.: Animal transport and welfare: 5 EFSA opinions to define new EU rules.

- Fuseini, A. : Pre-slaughter handling and possible impact on animal welfare and meat quality. Dans: Halal Slaughter of Livestock: Animal Welfare Science, History and Politics of Religious Slaughter. p. 49-86. Springer (2022).

- Nath, D. : Smart Farming: Automation and Robotics in Agriculture. Dans: Recent Trends in Agriculture. p. 281-310. Integrated Publications (2023).

- Papakonstantinou, G.I. , Voulgarakis, N., Terzidou, G., Fotos, L., Giamouri, E., Papatsiros, V.G.: Precision Livestock Farming Technology: Applications and Challenges of Animal Welfare and Climate Change. Agriculture. 14, 620 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Food, of the United Nations, A.O.: The State of Food and Agriculture 2023: Unlocking the potential of livestock systems, (2023). U: The State of Food and Agriculture 2023.

- Food, of the United Nations, A.O.: Pathways towards lower emissions – A global assessment of greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation options from livestock agrifood systems, (2023).

- Caccialanza, A. , Cerrato, D., Galli, D.: Sustainability practices and challenges in the meat supply chain: a systematic literature review. British Food Journal. 125, 4470-4497 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. , Sullivan, P., Bretón, J., Dean, L., Edwards-Callaway, L.: Investigating the impact of pre-slaughter management factors on indicators of fed beef cattle welfare – a scoping review. Frontiers in Animal Science. 3, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kappes, A. , Tozooneyi, T., Shakil, G., Railey, A.F., McIntyre, K.M., Mayberry, D.E., Rushton, J., Pendell, D.L., Marsh, T.L.: Livestock health and disease economics: a scoping review of selected literature. Front Vet Sci. 10, (2023). [CrossRef]

- García-Machado, J.J. , Greblikaitė, J., Iranzo Llopis, C.E.: Risk Management Tools in the Agriculture Sector: an Updated Bibliometric Mapping Analysis. Studies in Risk and Sustainable Development. 398, 1-26 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Food, of the United Nations, A.O.: Voluntary Code of Conduct for Food Loss and Waste Reduction, (2022).

- Gbaguidi, L.A.M. , Münstermann, S., Sow, M.: Manual for the Management of Operations during an Animal Health Emergency (FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 27), (2022).

- Collins, L.M. , Smith, L.M.: Review: Smart agri-systems for the pig industry. animal. 16, 100518 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Prates, J.A.M. : Heat Stress Effects on Animal Health and Performance in Monogastric Livestock: Physiological Responses, Molecular Mechanisms, and Management Interventions. Vet Sci. 12, 429 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Schrobback, P. , Zhang, A., Loechel, B., Ricketts, K., Ingham, A.: Food Credence Attributes: A Conceptual Framework of Supply Chain Stakeholders, Their Motives, and Mechanisms to Address Information Asymmetry. Foods. 12, 538 (2023). [CrossRef]

- FAO: FAO strategic framework 2022–31, (2021).

- Commission, E. : Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee – Aligning the circular economy and the bioeconomy at EU and national level (own-initiative opinion), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/C/2025/109/oj, (2025).

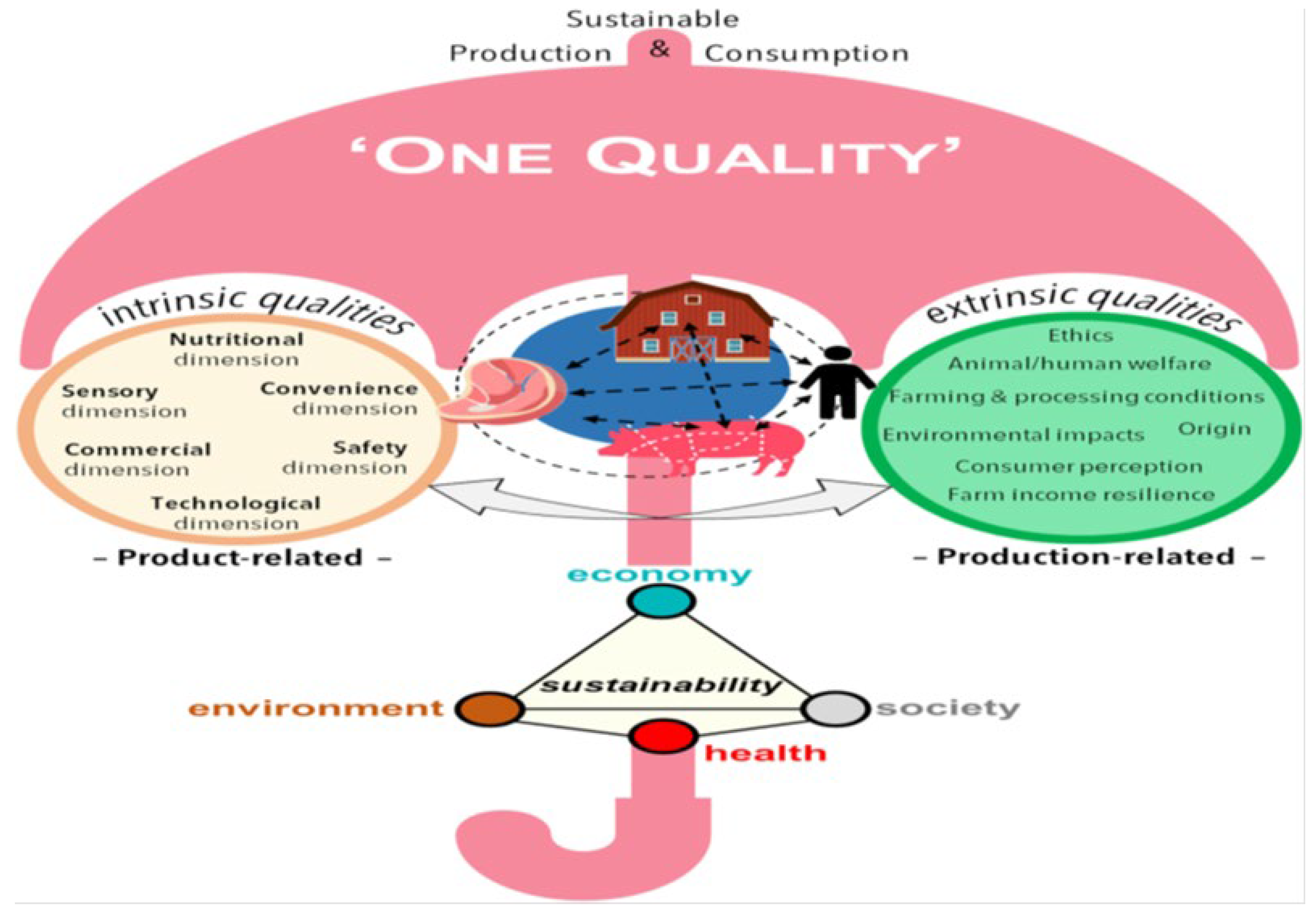

- Gagaoua, M. , Gondret, F., Lebret, B.: Towards a ‘One quality’ approach of pork: A perspective on the challenges and opportunities in the context of the farm-to-fork continuum – Invited review. Meat Sci. 226, 109834 (2025). [CrossRef]

- EFPRA: European Fat Processors and Renderers Association Sustainability charter for a circular bioeconomy, version 1, https://efpra.eu/sustainability/, (2021).

- Alibekov, R.S. , Alibekova, Z.I., Bakhtybekova, A.R., Taip, F.S., Urazbayeva, K.A., Kobzhasarova, Z.I.: Review of the slaughter wastes and the meat by-products recycling opportunities. Front Sustain Food Syst. 8, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Shirsath, A.P. , Henchion, M.M.: Bovine and ovine meat co-products valorisation opportunities: A systematic literature review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 118, 57-70 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Sagar, N.A. , Pathak, M., Sati, H., Agarwal, S., Pareek, S.: Advances in pretreatment methods for the upcycling of food waste: A sustainable approach. Trends Food Sci Technol. 147, 104413 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S, R. , Sabumon, P.C.: A critical review on slaughterhouse waste management and framing sustainable practices in managing slaughterhouse waste in India. J Environ Manage. 327, 116823 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Shurson, G.C. , Urriola, P.E.: Sustainable swine feeding programs require the convergence of multiple dimensions of circular agriculture and food systems with One Health. Animal Frontiers. 12, 30-40 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Rodriguez, J. , Ryschawy, J., Grillot, M., Martin, G.: Circularity and livestock diversity: Pathways to sustainability in intensive pig farming regions. Agric Syst. 213, 103809 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Shurson, G.C. : We Can Optimize Protein Nutrition and Reduce Nitrogen Waste in Global Pig and Food Production Systems by Adopting Circular, Sustainable, and One Health Practices. J Nutr. 155, 367-377 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ozturk-Kerimoglu, B. , Tkacz, K., Modzelewska-Kapituła, M., Ozdikicierler, O., Urgu-Ozturk, M.: Current perspectives on sustainable technologies for effective valorization of industrial meat waste: Opening the door to a greener future. Dans: Advances in Food and Nutrition Research. p. 239-294 (2025).

- Binhweel, F. , Ahmad, M.I., H.P.S., A.K., Hossain, M.S., Shakir, M.A., Senusi, W., Shalfoh, E., Alsaadi, S.: Kinetics, thermodynamics, and optimization analyses of lipid extraction from discarded beef tallow for bioenergy production. Sep Sci Technol. 1-20 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.-W. , Kim, H.-J., Shin, M.-S., Pak, S.-H.: Ultrasonic treatment of waste livestock blood for enhancement of solubilization. Environmental Engineering Research. 21, 22-28 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Kadem, Z.A. , Al-Hilphy, A.R., Alasadi, M.H., Gavahian, M.: Combination of ohmic heating and subcritical water to recover amino acids from poultry slaughterhouse waste at a pilot-scale: new valorization technique. J Food Sci Technol. 60, 24-34 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chatti, W. , Majeed, M.T.: Meat production, technological advances, and environmental protection: evidence from a dynamic panel data model. Environ Dev Sustain. 26, 31225-31250 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, Z. , Kulczycka, J., Makara, A., Mondello, G., Salomone, R.: Industrial Symbiosis for Sustainable Management of Meat Waste: The Case of Śmiłowo Eco-Industrial Park, Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 20, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Varzakas, T.; Smaoui, S. Global Food Security and Sustainability Issues: The Road to 2030 from Nutrition and Sustainable Healthy Diets to Food Systems Change. Foods 2024, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floros, J.D. , Newsome, R., Fisher, W., Barbosa-Cánovas, G. V., Chen, H., Dunne, C.P., German, J.B., Hall, R.L., Heldman, D.R., Karwe, M. V., Knabel, S.J., Labuza, T.P., Lund, D.B., Newell-McGloughlin, M., Robinson, J.L., Sebranek, J.G., Shewfelt, R.L., Tracy, W.F., Weaver, C.M., Ziegler, G.R.: Feeding the World Today and Tomorrow: The Importance of Food Science and Technology. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 9, 572-599 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.L. Food packaging : principles and practice. CRC Press (2016).

- Falkman, M. Ann.: Fundamentals of packaging technology. Institue of Packaging Professionals (2014).

- Singh, Preeti., Wani, A.Abas., Langowski, H.-Christian.: Food Packaging Materials : Testing & Quality Assurance. CRC Press (2017).

- HLPE: Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food systems, (2014).

- Falkman, M. Ann.: Fundamentals of packaging technology. Institue of Packaging Professionals (2014).

- King, T. , Cole, M., Farber, J.M., Eisenbrand, G., Zabaras, D., Fox, E.M., Hill, J.P.: Food safety for food security: Relationship between global megatrends and developments in food safety. Trends Food Sci Technol. 68, 160-175 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Mullan, M. , McDowell, D.: Modified Atmosphere Packaging. Dans: Food and Beverage Packaging Technology. p. 263-294. Wiley (2011).

- Spencer, K.C. : Modified atmosphere packaging of ready-to-eat foods. Dans: Innovations in Food Packaging. p. 185-203. Elsevier (2005).

- Heinrich, V. , Zunabovic, M., Nehm, L., Bergmair, J., Kneifel, W.: Influence of argon modified atmosphere packaging on the growth potential of strains of Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli. Food Control. 59, 513-523 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Tiekstra, S. , Dopico-Parada, A., Koivula, H., Lahti, J., Buntinx, M.: Holistic Approach to a Successful Market Implementation of Active and Intelligent Food Packaging. Foods. 10, 465 (2021). [CrossRef]

- COST Action FP1405 (ActInPak): Active and Intelligent Fibre-Based Packaging – Innovation and Market Introduction. A: Action FP1405 (ActInPak).

- European Commission: Commission Regulation (EC) No 450/2009 of 29 May 2009 on Active and Intelligent Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food (Text with EEA Relevance). (2009).

- Parliament, E. of the European Union, C.: Regulation (EC) No 1935/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 October 2004 on materials and articles intended to come into contact with food and repealing Directives 80/590/EEC and 89/109/EEC, (2004).

- Han, J.H. Innovations in Food Packaging. Elsevier (2005).

- Martín-Mateos, M.J. , Amaro-Blanco, G., Manzano, R., Andrés, A.I., Ramírez, R.: Efficacy of modified active packaging with oxygen scavengers for the preservation of sliced Iberian dry-cured shoulder. Food Science and Technology International. 29, 318-330 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. , Zhang, J., Zhang, L., Qin, Z., Wang, T.: Review of Recent Advances in Intelligent and Antibacterial Packaging for Meat Quality and Safety. Foods. 14, 1157 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Smaoui, S. , Ben Hlima, H., Tavares, L., Ennouri, K., Ben Braiek, O., Mellouli, L., Abdelkafi, S., Mousavi Khaneghah, A.: Application of essential oils in meat packaging: A systemic review of recent literature. Food Control. 132, 108566 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gaba, S. , Morsy, M., Abdel-Daim, M., Mahgoub, S.: Protective impact of chitosan film loaded with oregano and thyme essential oils on the microbial profile and quality attributes of beef meat. Antibiotics. 11, 583 (2022).

- Jeong, S. , Lee, H., Lee, S.Y., Yoo, S.: Preparation of food active packaging materials based on calcium hydroxide and modified porous medium for reducing carbon dioxide and kimchi odor. J Food Sci. 89, 419-434 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, S.M.H. , Kaur, M., Farahnaky, A., Torley, P.J., Osborn, A.M.: Microbial and Quality Attributes of Beef Steaks under High-CO2 Packaging: Emitter Pads versus Gas Flushing. Foods. 13, 2913 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Castrica, M. , Miraglia, D., Menchetti, L., Branciari, R., Ranucci, D., Balzaretti, C.M.: Antibacterial Effect of an Active Absorbent Pad on Fresh Beef Meat during the Shelf-Life: Preliminary Results. Applied Sciences. 10, 7904 (2020). [CrossRef]

- das Neves, M. da S., Scandorieiro, S., Pereira, G.N., Ribeiro, J.M., Seabra, A.B., Dias, A.P., Yamashita, F., Martinez, C.B. dos R., Kobayashi, R.K.T., Nakazato, G.: Antibacterial Activity of Biodegradable Films Incorporated with Biologically-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles and the Evaluation of Their Migration to Chicken Meat. Antibiotics. 12, 178 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Baghi, F. , Gharsallaoui, A., Dumas, E., Ghnimi, S.: Advancements in Biodegradable Active Films for Food Packaging: Effects of Nano/Microcapsule Incorporation. Foods. 11, 760 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Waldhans, C. , Albrecht, A., Ibald, R., Wollenweber, D., Sy, S.-J., Kreyenschmidt, J.: Temperature Control and Data Exchange in Food Supply Chains: Current Situation and the Applicability of a Digitalized System of Time–Temperature-Indicators to Optimize Temperature Monitoring in Different Cold Chains. J Packag Technol Res. 8, 79-93 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. , Wen, L., Liu, J., Du, P., Liu, Y., Hu, P., Cao, J., Wang, W.: Enhanced pH-sensitive anthocyanin film based on chitosan quaternary ammonium salt: A promising colorimetric indicator for visual pork freshness monitoring. Int J Biol Macromol. 279, 135236 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Commission, E. Final report summary – TOXDTECT (Innovative packaging for the detection of fresh meat quality and prediction of shelf-life) [Project ID 603425], (2024).

- Mehdizadeh, S.A. , Noshad, M., Chaharlangi, M., Ampatzidis, Y.: AI-driven non-destructive detection of meat freshness using a multi-indicator sensor array and smartphone technology. Smart Agricultural Technology. 10, 100822 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, K.R. , Uysal-Unalan, I., Krauter, V., Weinrich, R., Incarnato, L., Karlovits, I., Colelli, G., Chrysochou, P., Fenech, M.C., Pettersen, M.K., Arranz, E., Marcos, B., Frigerio, V., Apicella, A., Yildirim, S., Poças, F., Dekker, M., Johanna, L., Coma, V., Corredig, M.: Sustainable food packaging: An updated definition following a holistic approach. Front Sustain Food Syst. 7, (2023). [CrossRef]

- ISO: ISO 14040:2006, https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html, (2006).

- Hunt, R.G. , Franklin, W.E., Welch, R.O., Cross, J.A., Woodall, A.E.: Resource and Environmental Profile Analysis of Nine Beverage Container Alternatives, (1974).

- Molina-Besch, K. , Wikström, F., Williams, H.: The environmental impact of packaging in food supply chains—does life cycle assessment of food provide the full picture? Int J Life Cycle Assess. 24, 37-50 (2019). [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme: Single-use supermarket food packaging and its alternatives: Recommendations from life cycle assessments. , Nairobi, Kenya (2022).

- Crippa, M. , Solazzo, E., Guizzardi, D., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Tubiello, F.N., Leip, A.: Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat Food. 2, 198-209 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, S.J. , Campbell, B.M., Ingram, J.S.I.: Climate Change and Food Systems. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 37, 195-222 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Jungbluth, N. : Environmental consequences of food consumption: A modular life cycle assessment to evaluate product characteristics. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 5, 143-144 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Williams, H. , Verghese, K., Lockrey, S., Crossin, E., Clune, S., Rio, M., Wikström, F.: The greenhouse gas profile of a “Hungry Planet”; quantifying the impacts of the weekly food purchases including associated packaging and food waste of three families. Dans: 19th IAPRI World Conference on Packaging. , Melbourne, Australia (2014).

- Heller, M.C. , Selke, S.E.M., Keoleian, G.A.: Mapping the Influence of Food Waste in Food Packaging Environmental Performance Assessments. J Ind Ecol. 23, 480-495 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Krauter, V. , Bauer, A.-S., Milousi, M., Dörnyei, K.R., Ganczewski, G., Leppik, K., Krepil, J., Varzakas, T.: Cereal and Confectionary Packaging: Assessment of Sustainability and Environmental Impact with a Special Focus on Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Foods. 11, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Hellström, D. , Olsson, A., Nilsson, F.: Managing Packaging Design for Sustainable Development. Wiley (2016).

- Licciardello, F. : Packaging, blessing in disguise. Review on its diverse contribution to food sustainability. Trends Food Sci Technol. 65, 32-39 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wikström, F. , Williams, H.: Potential environmental gains from reducing food losses through development of new packaging – a life-cycle model. Packaging Technology and Science. 23, 403-411 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Williams, H. , Wikström, F.: Environmental impact of packaging and food losses in a life cycle perspective: a comparative analysis of five food items. J Clean Prod. 19, 43-48 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, H. , Balcells, M., Sazdovski, I., Fullana-i-Palmer, P., Margallo, M., Aldaco, R., Puig, R.: Environmental comparison of food-packaging systems: The significance of shelf-life extension. Cleaner Environmental Systems. 13, 100197 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Casson, A. , Giovenzana, V., Frigerio, V., Zambelli, M., Beghi, R., Pampuri, A., Tugnolo, A., Merlini, A., Colombo, L., Limbo, S., Guidetti, R.: Beyond the eco-design of case-ready beef packaging: The relationship between food waste and shelf-life as a key element in life cycle assessment. Food Packag Shelf Life. 34, 100943 (2022). [CrossRef]

| Preventive Actions | Application | Impact |

Estimated Losses Prevented (%) |

Recent Sources |

| Animal Health Management | Use of veterinary services, vaccinations, early disease detection, and improved hygiene. | Reduces mortality and condemned carcasses. | 3–7% (on-farm mortality reduction) | FAO, 2023; Buzdugan et al., 2021 [83] |

| Improved Animal Handling & Transport | Trained staff, reduced transport time, gentle handling. | Reduces bruising, DFD/PSE meat, transport deaths. | 1–3% of total carcass value preserved | Dongo et al., 2022; [84] Fuseini, 2022 [85] |

| Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) | Smart sensors, real-time health/feed monitoring. | Prevents early losses, improves efficiency. | 2–5% mortality and inefficiency reduction | Nath, 2023[86]; Papakonstantinou, 2021 [87] |

| Genetic Improvement and Breeding | Selecting traits, feed conversion, disease resistance. | Better survivability and consistency in meat production. | 1–3% long-term yield increase | Li, 2024[57]; FAO, 2023a[88] |

| Feed Quality and Management | Balanced rations, proper storage, clean water access. | Reduces digestive issues, improves weight gain. | 2–4% mortality reduction & improved conversion | FAO, 2023b [89]; Caccialanza et al., 2023[90] |

| Slaughterhouse Scheduling and Coordination | Aligning transport and slaughter capacity. | Minimizes animal stress and holding-time losses. | Up to 2% reduction in pre-slaughter losses | Davis et al., 2022 [91] |

| On-farm Mortality Surveillance and Reduction Programs | Continuous tracking and timely interventions. | Reduces unexplained livestock deaths. | 1–2.5% fewer unproductive deaths | Kappes et al., 2023[92]; García-Machado et al., 2024[93] |

| Training and Capacity Building for Producers | Educating on welfare, nutrition, handling. | Improves productivity and reduces error-related losses. | Variable, but up to 5% efficiency improvement | FAO, 2022[94]; Gbaguidi, 2022[95] |

| Environmental Control in Animal Housing | Ventilation, cooling, proper bedding and lighting. | Prevents heat/cold stress and death. | 1–4% loss reduction in hot/cold climates | Collins & Smith, 2022;[96] Prates, 2025[97] |

| Use of Mobile/Decentralized Slaughter Units | Slaughter units near farms to reduce transport. | Lowers stress, mortality, and meat defects. | Up to 2% pre-slaughter loss reduction | Schrobback et al., 2023;[98] FAO, 2022[94] |

| Study Focus | Packaging Type | Key Findings | Reference |

| Assessment of greenhouse gas emissions in food–packaging systems | General comparison across food categories | Packaging contributes about 5% of total GHG emissions in the food–packaging system; values vary depending on the product group | [37,150] |

| Environmental contribution of meat vs. plant-based food packaging | Overwrap and MAP packaging in meat products | Meat packaging accounts for ~2% of total GHG emissions, while fruits and vegetables packaging accounts for ~10% | [151,152,153,154,155] |

| Optimization of packaging for high-impact foods | Meat and meat products | Effective packaging plays a key role in reducing food waste and overall environmental impact | [153,154,156,157,158] |

| Role of packaging in reducing food waste | Various optimized packaging systems | Well-designed and, where needed, increased packaging use helps minimize total environmental impact | [159,160] |

| Comparative LCA of different meat packaging systems | Overwrap, high-oxygen MAP, and vacuum skin packaging | Vacuum skin packaging showed better environmental performance and extended shelf life compared to traditional methods | [161] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).