Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. From Eukaryotic “Powerhouse” to the Life-Orchestrating Biosensors in Humans: The Evolution of Mitochondrial Significance Traced by Exercise

3. Mitochondrial Health and Rejuvenation as the Hub of Physical Fitness and Vice Versa

- Ageing is associated with minimal or even no changes in mitochondrial respiration and content; moreover, physical activity status was positively associated with quantity and quality of mitochondria throughout the human lifespan.

- In the pooled group of participants (all ages together) mitochondrial respiration was positively correlated with muscle strength and physical function;

- Noteworthy, ageing per se is not associated with increasing H2O2 emission; however, physically active participants demonstrated higher levels of H2O2 emission compared with physically inactive participants; although potential explanation is controversial (increased number of mitochondrial or/and increased oxidative stress by exercise), this fact has to be kept in mind, when the type, intensity and duration is prescribed;

- No impact of ageing on the mitochondrial calcium uptake was recorded; nonetheless, higher calcium uptake was observed in physically active participant compared to inactive ones within the age group > 40 years.

4. Mitochondrial Multiomic Response to Endurance Exercise Training Is Highly Tissue-Specific

- The minimal mitochondrial multiomic alterations were reported for the brain, small intestine and spleen. To this end, the brain is a mitochondria-rich organ with high levels of energy consumption at rest; although brain activity increases during exercise, the differential metabolic demand is relatively low;

- In contrast, cardiac and skeletal muscles mitochondria demonstrate highly increased ATP production covering significantly enhanced energy demand during contractions. Contextually, the greatest shifts in multiomic patterns were recorded for skeletal muscles, heart but also for liver, colon, adrenal gland, brown and white adipose tissue and blood reflecting adaptive mitochondrial response towards the endurance training and corresponding demands such as stress modulation, improved bioenergetics, blood flow and signalling and metabolic shifts adapting to repeated bouts of exercise.

- Mitochndrial stress response modulation affects sympathetic adrenal-medullary activation, catecholamine and cortisol levels – all considered adaptive for reducing acute stress [24].

- Hepatic mitochondria are critical for oxidising fat for providing ATP and substrates to fuel TCA cycle flux and gluconeogenesis to maintain glucose levels in blood at rest, fasting and under stress conditions. Endurance training leads to improved mitochondrial qualities even independent from their increasing quantity. Per evidence, multiomic changes linked to the exercise demonstrated opposite regulation patterns compared to those induced by the liver cirrhosis [23].

- Brown adipose tissue is rich in mitochondria which are crucial for a physiologic thermogenesis adapted to the cold stress provocation and maintaining physiologic body temperature. Also for this tissue significantly altered multiomic patterns were recorded after endurance training that is well in consensus with energy preservation mechanisms described for professionally trained athletes.

5. Type, Intensity, Frequency, and Duration of the Exercise Training – All Demand Individualised Prescription Tailored to Individualised Patient Profiling

5.1. Healthy Adults of All Ages

- -

- either the moderate intensity cardiorespiratory training for more than 30 minutes daily on at least 5 days a week (totally >150 minutes weekly), vigorous-intensity cardiorespiratory exercise for more than 20 minutes daily on at least 3 days a week (totally >75 minutes weekly),

- -

- or a combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity training with a total energy expenditure of 500-1000 MET minutes per week;

- -

- On 2-3 days a week, adults should perform resistance exercise for each of the major muscle group as well as neuro-motor training of balance, agility and coordination;

- -

- Further, for maintaining joint rang of movement a series of flexibility exercise for each the major muscle-tendon groups (60 seconds per exercise) on at least 2 days a week is strongly recommended.

5.2. Natural Body Building

- Muscle groups in focus should be trained at least two times a week; certainly the muscle volume benefits from a frequent exercise;

- 3-15 repetitions in the 6-12 range (in total 40-70 repetitions for each of the major muscle group per session) should occur to achieve visible effects; for advanced bodybuilder higher numbers of repetitions are appropriate;

- Rest intervals of 1-3 minutes are adequate;

- Chosen tempo should allow for controlling the muscular load;

- Cardiovascular exercise training is recommended to intensify fat loss;

- High-intensity training demands better recovery;

- Fasted cardiovascular training is not recommended, since being not really beneficial and could be even detrimental.

5.3. Exercise Training in the Overall Management of Obesity in Adults

- An aerobic exercise at moderate intensity is strongly recommended for loss in body weight, total fat, visceral fat, intra-hepatic fat, and for improvement in blood pressure;

- On average, the expected weight loss is 2 to 3 kg;

- An exercise training program based specifically on resistance training at moderate-to-high intensity is recommended for preservation of lean mass during weight loss;

- For improved cardiorespiratory fitness and insulin sensitivity, any type of exercise training can be applied, namely either aerobic or resistance as well as a combination of both – aerobic and resistance one; after cardiovascular risk assessment also high-intensity interval training can be considered under professional supervision;

- Specifically for the muscular fitness improvement, an exercise training program based preferentially on resistance training alone (or in combination with aerobic training) is recommended;

- Complementary recommendations consider psychological and energetic aspects, appetite control and bariatric surgery as well as life style and behavioural habits in overall management of overweight and obesity.

5.4. Adapted Exercise Training Benefits Children with Attention Deficits Hyperactivity Disorders (ADHD)

- Aerobic exercise training demonstrates a capacity to positively impact neurotransmitter (serotonin and dopamine amongst others) production and to stimulate blood flow in the brain;

- Perceptual motor exercise and meditation stimulate neuroplasticity improving synaptic cross-communication and strengthening the sensory-motor competencies collectively mitigating attention deficits;

5.5. Exercise for Patients with Peripheral Neuropathies (PN)

5.6. Exercise Recommendations for Individuals Diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

5.7. Exercise Prescription Tailored to the “Long COVID Syndrome” (LCS) Affected Individuals

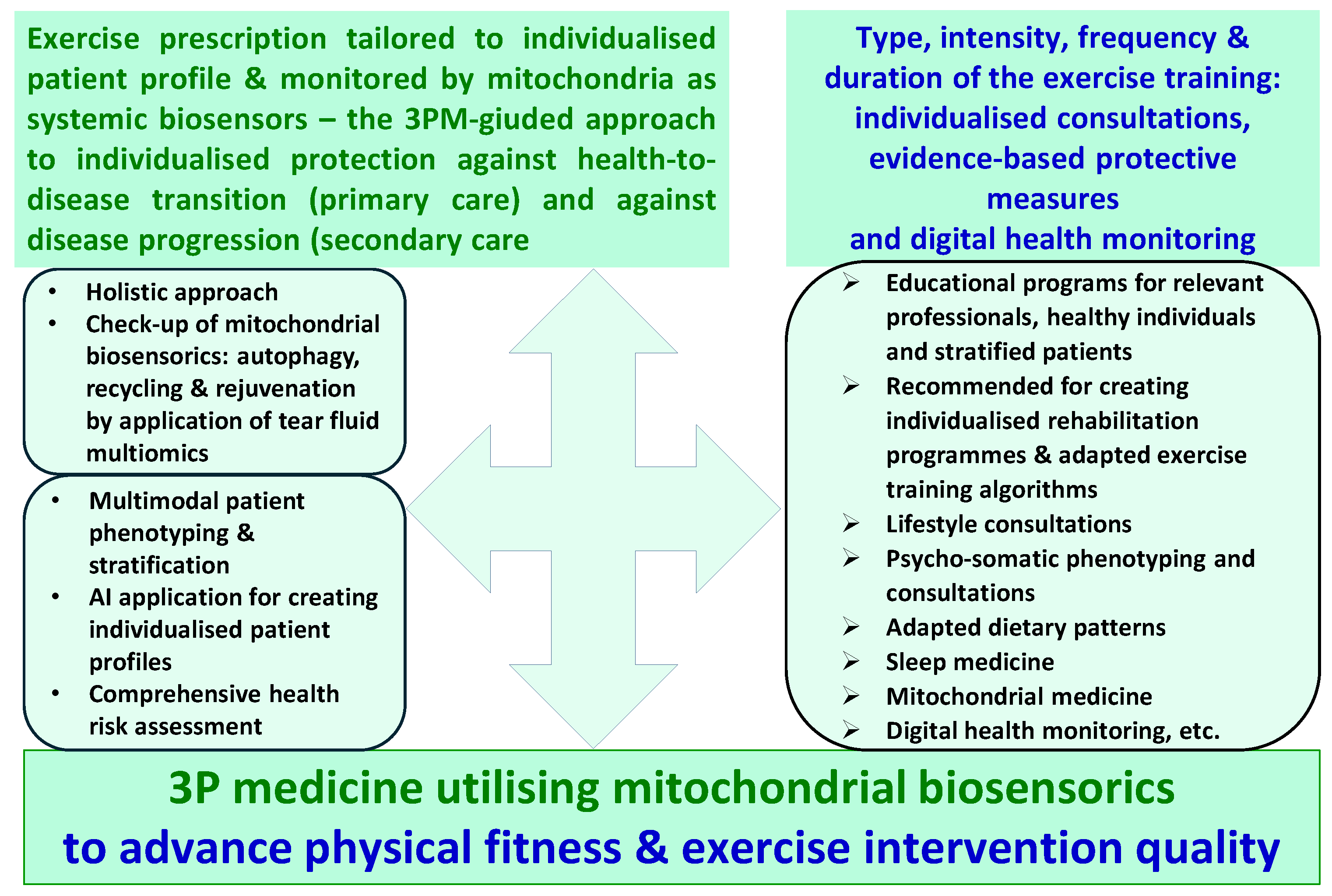

6. Individualised Check-Up of the Mitochondrial Biosensorics Is Crucial for Physical Fitness and Exercise Intervention Quality – Concluding Remarks

- -

- the goal is to improve physical fitness and to advance exercise intervention quality by the paradigm change from reactive to proactive care implementing concepts of predictive, preventive and personalised (3P) medicine;

- -

- the key instrument is mitochondrial biosensorics as detailed in this article;

- -

- the consequent pathway to achieve the goal is, on a regular basis, to perform mitochondrial biosensorics check-up.

Funding

Data availability

Consent for publication

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficits Hyperactivity Disorders |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| HC | Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy |

| LCS | Long-COVID Syndrome |

| PN | Peripheral Neuropathies |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCD | Sudden Cardiac Death |

References

- Wang W, Yan Y, Guo Z, Hou H, Garcia M, Tan X, Anto EO, Mahara G, Zheng Y, Li B, Kang T, Zhong Z, Wang Y, Guo X, Golubnitschaja O; Suboptimal Health Study Consortium and European Association for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine. All around suboptimal health - a joint position paper of the Suboptimal Health Study Consortium and European Association for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine. EPMA J. 2021;12(4):403-433. [CrossRef]

- Booth FW, Roberts CK, Laye MJ. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(2):1143-211. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, Merghani A, Lluis Mont L. Exercise and the heart: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(23):1445-53. [CrossRef]

- Kochi AN, Vettor G, Dessanai MA, Pizzamiglio F, Tondo C. Sudden Cardiac Death in Athletes: From the Basics to the Practical Work-Up. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(2):168. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Malhotra, R.; Chiampas, G.; d’Hemecourt, P.; Troyanos, C.; Cianca, J.; Smith, R.N.; Wang, T.J.; Roberts, W.O. Thompson, P.D.; et al. Cardiac Arrest during Long-Distance Running Races. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 130–140;

- Corrado, D.; Basso, C.; Pavei, A.; Michieli, P.; Schiavon, M.T.G. Trends in Sudden Cardiovascular Death in Young Competitive Athletes. JAMA 2006, 296, 1593–1601.

- Maron, B.J.; Gohman, T.E.; Aeppli, D. Prevalence of Sudden Cardiac Death during Competitive Sports Activities in Minnesota High School Athletes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998, 32, 1881–1884.

- Steinvil, A.; Chundadze, T.; Zeltser, D.; Rogowski, O.; Halkin, A.; Galily, Y.; Perluk, H.; Viskin, S. Mandatory Electrocardiographic Screening of Athletes to Reduce Their Risk for Sudden Death: Proven Fact or Wishful Thinking? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57.

- Harmon, K.G.; Asif, I.M.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Owens, D.S.; Prutkin, J.M.; Salerno, J.C.; Zigman, M.L.; Ellenbogen, R.; Rao, A.L.; Ackerman, M.J.; et al. Incidence, Cause, and Comparative Frequency of Sudden Cardiac Death in National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletes a Decade in Review. Circulation 2015, 132, 10–19; 10.

- Malhotra, A.; Dhutia, H.; Finocchiaro, G.; Gati, S.; Beasley, I.; Clift, P.; Cowie, C.; Kenny, A.; Mayet, J.; Oxborough, D.; et al. Outcomes of Cardiac Screening in Adolescent Soccer Players. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 524–534.

- Li B, Liu F, Chen X, Chen T, Zhang J, Liu Y, Yao Y, Hu W, Zhang M, Wang B, Liu L, Chen K, Wu Y. FARS2 Deficiency Causes Cardiomyopathy by Disrupting Mitochondrial Homeostasis and the Mitochondrial Quality Control System. Circulation. 2024;149(16):1268-1284. [CrossRef]

- Song M, Franco A, Fleischer JA, Zhang L, Dorn GW 2nd. Abrogating Mitochondrial Dynamics in Mouse Hearts Accelerates Mitochondrial Senescence. Cell Metab. 2017;26(6):872-883.e5. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson ÅB, Dorn GW 2nd. Evolving and Expanding the Roles of Mitophagy as a Homeostatic and Pathogenic Process. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(1):853-892. [CrossRef]

- Ostojic SM. Exercise-induced mitochondrial dysfunction: a myth or reality? Clin Sci (Lond). 2016 Aug 1;130(16):1407-16. [CrossRef]

- Bishop DJ, Lee MJ, Picard M. Exercise as Mitochondrial Medicine: How Does the Exercise Prescription Affect Mitochondrial Adaptations to Training? Annu Rev Physiol. 2025;87(1):107-129. [CrossRef]

- Kurland CG, Andersson SG. Origin and evolution of the mitochondrial proteome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64(4):786-820. [CrossRef]

- Holland HD. The oxygenation of the atmosphere and oceans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1470):903-15. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson MI, Tarnopolsky MA. Mitochondria and Aging-The Role of Exercise as a Countermeasure. Biology (Basel). 2019;8(2):40. [CrossRef]

- Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis JAMA 2009;301(19):2024-35. [CrossRef]

- Reimers CD, Knapp G, Reimers AK. Does physical activity increase life expectancy? A review of the literature. J Aging Res. 2012:2012:243958. [CrossRef]

- Lee DC, Brellenthin AG, Thompson PD, Sui X, Lee IM, Lavie CJ. Running as a Key Lifestyle Medicine for Longevity. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60(1):45-55. [CrossRef]

- Cefis M, Marcangeli V, Hammad R, Granet J, Leduc-Gaudet J-P et al. Impact of physical activity on physical function, mitochondrial energetics, ROS production, and Ca2+ handling across the adult lifespan in men Cell Rep Med. 2025;6(2):101968. [CrossRef]

- Amar D, Gay NR, Jimenez-Morales D, Jean Beltran PM, Ramaker ME, Raja AN, Zhao B, Sun Y, Marwaha S, Gaul DA, Hershman SG, Ferrasse A, Xia A, Lanza I, Fernández FM, Montgomery SB, Hevener AL, Ashley EA, Walsh MJ, Sparks LM, Burant CF, Rector RS, Thyfault J, Wheeler MT, Goodpaster BH, Coen PM, Schenk S, Bodine SC, Lindholm ME; MoTrPAC Study Group. The mitochondrial multi-omic response to exercise training across rat tissues. Cell Metab. 2024;36(6):1411-1429.e10. [CrossRef]

- Picard M, McManus MJ, Gray JD, Nasca C, Moffat C et al. Mitochondrial functions modulate neuroendocrine, metabolic, inflammatory, and transcriptional responses to acute psychological stress Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(48):E6614-23. [CrossRef]

- Miko HC, Zillmann N, Ring-Dimitriou S, Dorner TE, Titze S, Bauer R. Effects of Physical Activity on Health. Gesundheitswesen. 2020;82(S 03):S184-S195. [CrossRef]

- Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, Nieman DC, Swain DP; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334-59. [CrossRef]

- Golubnitschaja O, Kapinova A, Sargheini N, Bojkova B, Kapalla M, Heinrich L, Gkika E, Kubatka P. Mini-encyclopedia of mitochondria-relevant nutraceuticals protecting health in primary and secondary care-clinically relevant 3PM innovation. EPMA J. 2024;15(2):163-205. [CrossRef]

- Helms ER, Fitschen PJ, Aragon AA, Cronin J, Schoenfeld BJ. Recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: resistance and cardiovascular training. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2015;55(3):164-78.

- Oppert JM, Bellicha A, van Baak MA, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, Carraça EV, Encantado J, Ermolao A, Pramono A, Farpour-Lambert N, Woodward E, Dicker D, Busetto L. Exercise training in the management of overweight and obesity in adults: Synthesis of the evidence and recommendations from the European Association for the Study of Obesity Physical Activity Working Group. Obes Rev. 2021;22 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):e13273. [CrossRef]

- Chan YS, Jang JT, Ho CS. Effects of physical exercise on children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biomed J. 2022;45(2):265-270. [CrossRef]

- Khodagholi F, Zareh Shahamati S, Maleki Chamgordani M, Mousavi MA, Moslemi M, Salehpour M, Rafiei S, Foolad F. Interval aerobic training improves bioenergetics state and mitochondrial dynamics of different brain regions in restraint stressed rats. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48(3):2071-2082. [CrossRef]

- Streckmann F, Balke M, Cavaletti G, Toscanelli A, Bloch W, Décard BF, Lehmann HC, Faude O. Exercise and Neuropathy: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52(5):1043-1065. [CrossRef]

- Pesta M, Mrazova B, Kapalla M, Kulda V, Gkika E, Golubnitschaja O. Mitochondria-based holistic 3PM approach as the 'game-changer' for individualised rehabilitation - the proof-of-principle model by treated breast cancer survivors. EPMA J. 2024;15(4):559-571. [CrossRef]

- Du L, Xi H, Zhang S, Zhou Y, Tao X, Lv Y, Hou X, Yu L. Effects of exercise in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1387658. [CrossRef]

- Edward JA, Peruri A, Rudofker E, Shamapant N, Parker H, Cotter R, Sabin K, Lawley J, Cornwell WK 3rd. Characteristics and Treatment of Exercise Intolerance in Patients With Long COVID. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2023;43(6):400-406. [CrossRef]

- Gaffney FA, Nixon JV, Karlsson ES, Campbell W, Dowdey ABC, Blomqvist CG. Cardiovascular deconditioning produced by 20 hours of bedrest with head-down tilt (-5 degrees) in middle-aged healthy men. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56:634-638.

- Gluckman TJ, Bhave NM, Allen LA, et al. 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on cardiovascular sequelae of COVID-19 in adults: myocarditis and other myocardial involvement, post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and return to play. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(17):1717-1756.

- Ormiston CK, Swiatkiewicz I, Taub PR. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome as a sequela of COVID-19. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19(11):1880-1889.

- Rudofker E, Parker H, Cornwell WK III. An exercise prescription as a novel management strategy for treatment of Long COVID. JACC Case Rep. 2022;4(20):1344-1347.

- Rao P, Peritz DC, Systrom D, Lewine K, Cornwell WK III Hsu JJ. Orthostatic and exercise intolerance in recreational and competitive athletes with Long COVID. JACC Case Rep. 2022;4(17):1119-1123.

- Hughes DC, Orchard JW, Partridge EM, La Gerche A, Broderick C. Return to exercise post-COVID-19 infection: a pragmatic approach in mid-2022. J Sci Med Sport. 2022;25(7):544-547.

- Salman D, Vishnubala D, Le Feuvre P, et al. Returning to physical activity after Covid-19. BMJ. 2021;372:m4721.

- Teo WP, Goodwill AM. Can exercise attenuate the negative effects of long COVID syndrome on brain health? Front Immunol. 2022;13:986950.

- Guan Y, Yan Z. Mitochondrial Quality Control. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2025;1478:51-60. [CrossRef]

- Picca A, Calvani R, Leeuwenburgh C, Coelho-Junior HJ, Bernabei R, Landi F, Marzetti E. Targeting mitochondrial quality control for treating sarcopenia: lessons from physical exercise. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2019;23(2):153-160. [CrossRef]

- Romanello V, Sandri M. Mitochondrial Quality Control and Muscle Mass Maintenance. Front Physiol. 2016;6:422. [CrossRef]

- Oizumi R, Sugimoto Y, Aibara H. The Potential of Exercise on Lifestyle and Skin Function: Narrative Review. JMIR Dermatol. 2024;7:e51962. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Suo W, Zhang X, Liang J, Zhao W, Wang Y, Li H, Ni Q. Targeting mitochondrial quality control for diabetic cardiomyopathy: Therapeutic potential of hypoglycemic drugs. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;168:115669. [CrossRef]

- Golubnitschaja O. How to use an extensive Flammer syndrome phenotyping for a holistic protection against health-to-disease transition - facts and practical recommendations. EPMA J. 2025;16(3):535-539. [CrossRef]

- Shao Q, Ndzie Noah ML, Golubnitschaja O, Zhan X. Mitochondrial medicine: "from bench to bedside" 3PM-guided concept. EPMA J. 2025;16(2):239-264. [CrossRef]

- Golubnitschaja O, Sargheini N, Bastert J. Mitochondria in cutaneous health, disease, ageing and rejuvenation-the 3PM-guided mitochondria-centric dermatology. EPMA J. 2025;16(1):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Smokovski I, Steinle N, Behnke A, Bhaskar SMM, Grech G, Richter K, Niklewski G, Birkenbihl C, Parini P, Andrews RJ, Bauchner H, Golubnitschaja O. Digital biomarkers: 3PM approach revolutionizing chronic disease management - EPMA 2024 position. EPMA J. 2024;15(2):149-162. [CrossRef]

- 3PMedicon–your risk reducer. https://www.3pmedicon.com/en/scientific-evidence/compromised-mitochondrial-health assessed on September 19th 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).