Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Intrinsic Parameters of Shells

2.2. Contact Parameters

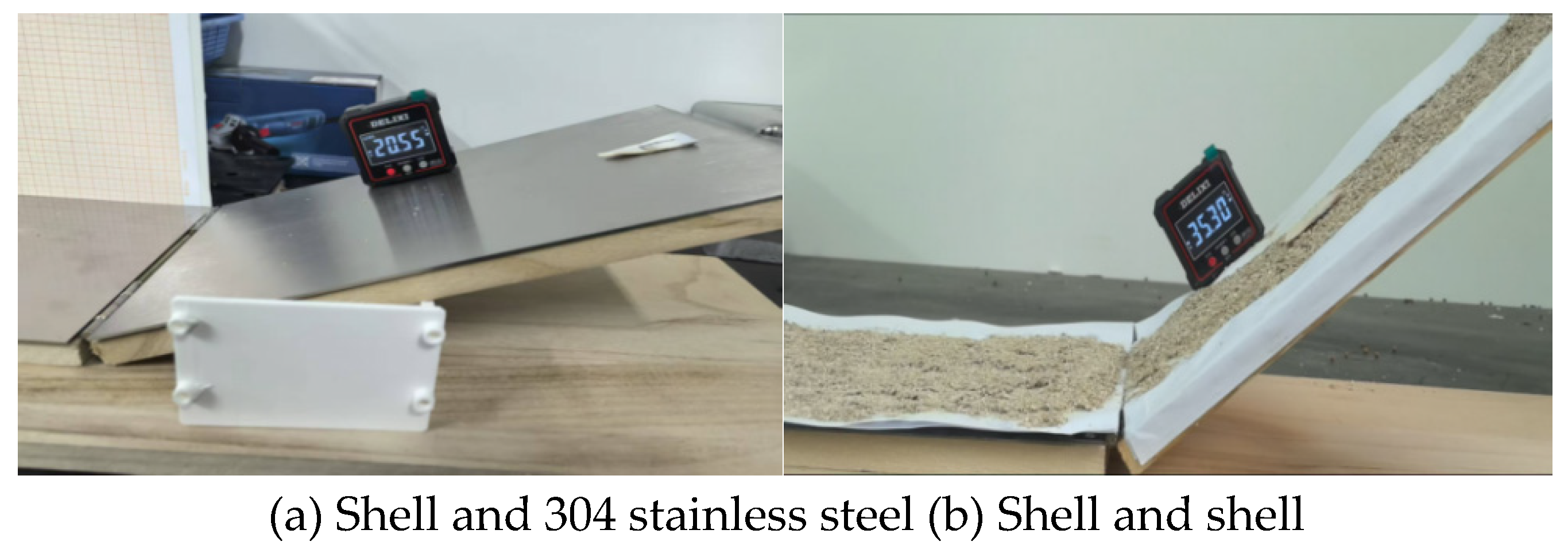

2.2.1. Coefficient of Static Friction

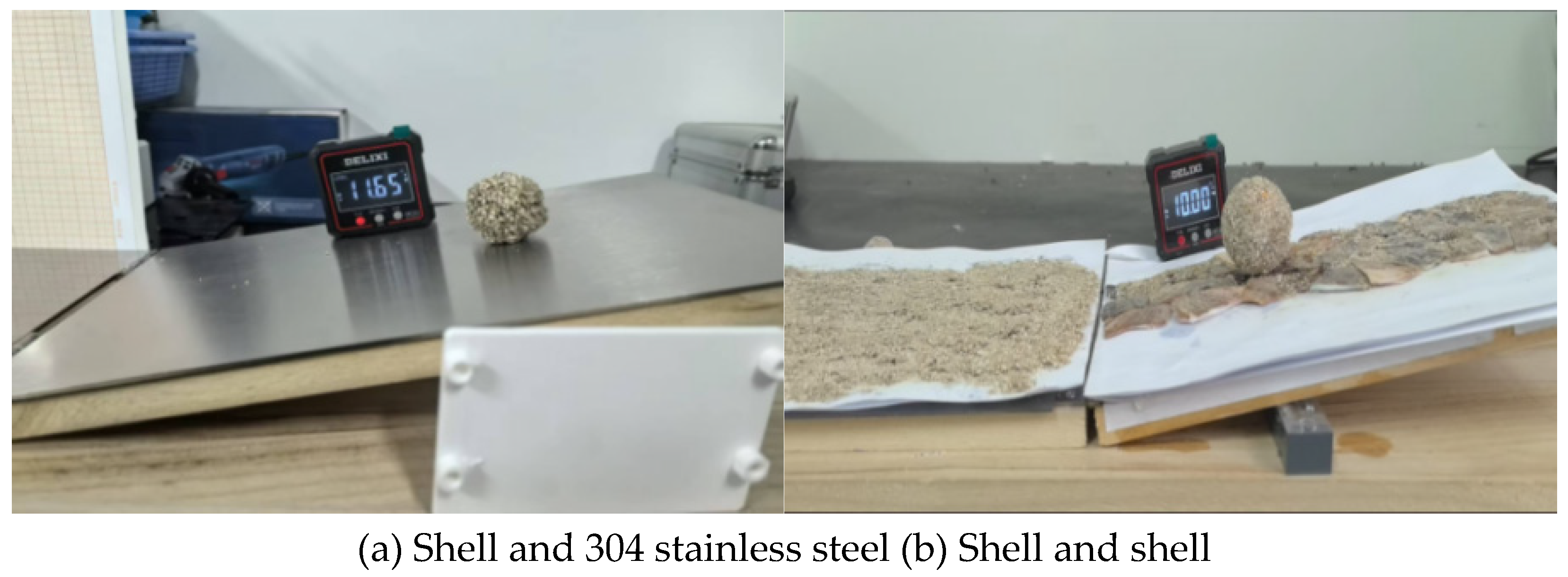

2.2.2. Rolling Friction Coefficient

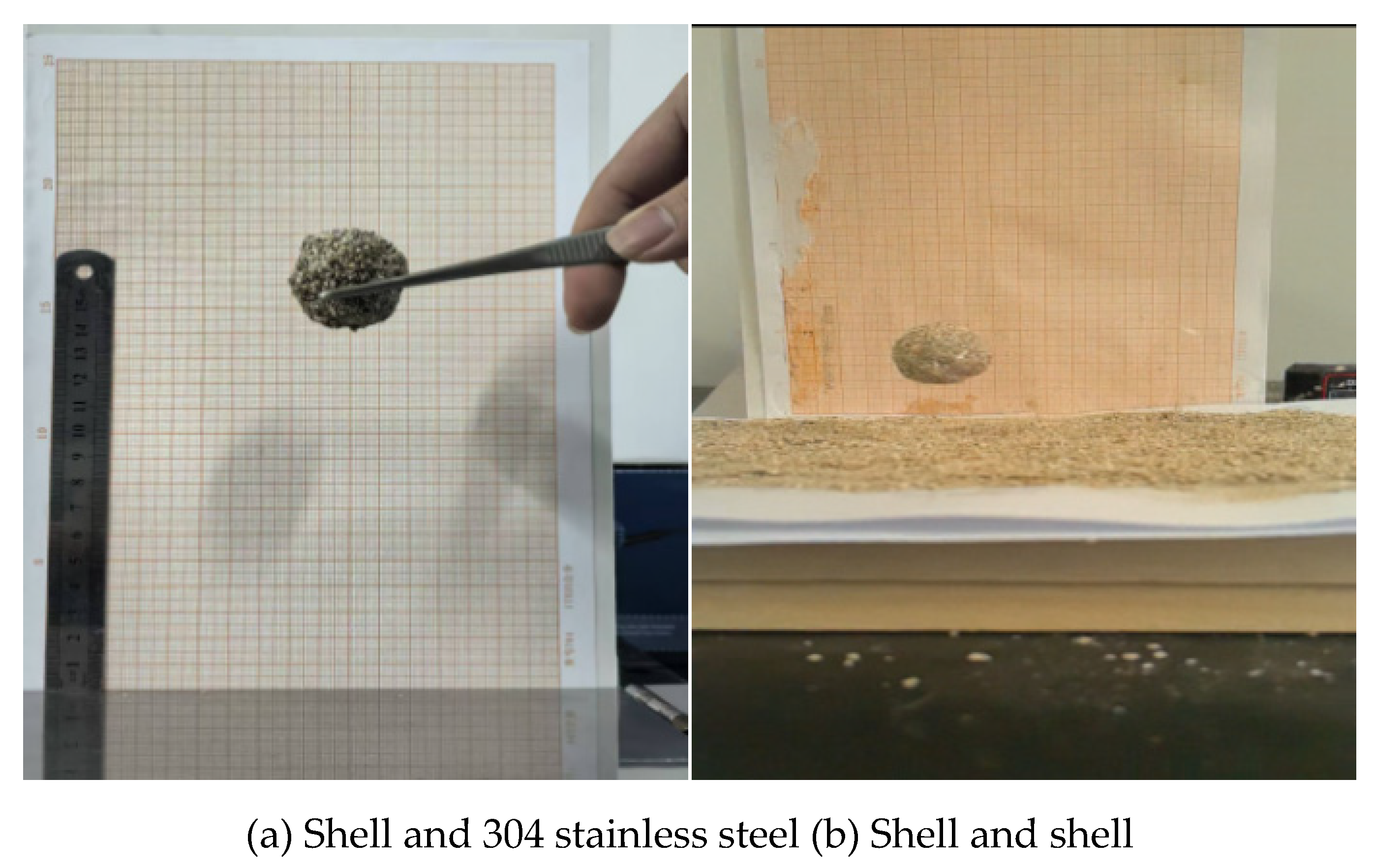

2.2.3. Collision Recovery Coefficient

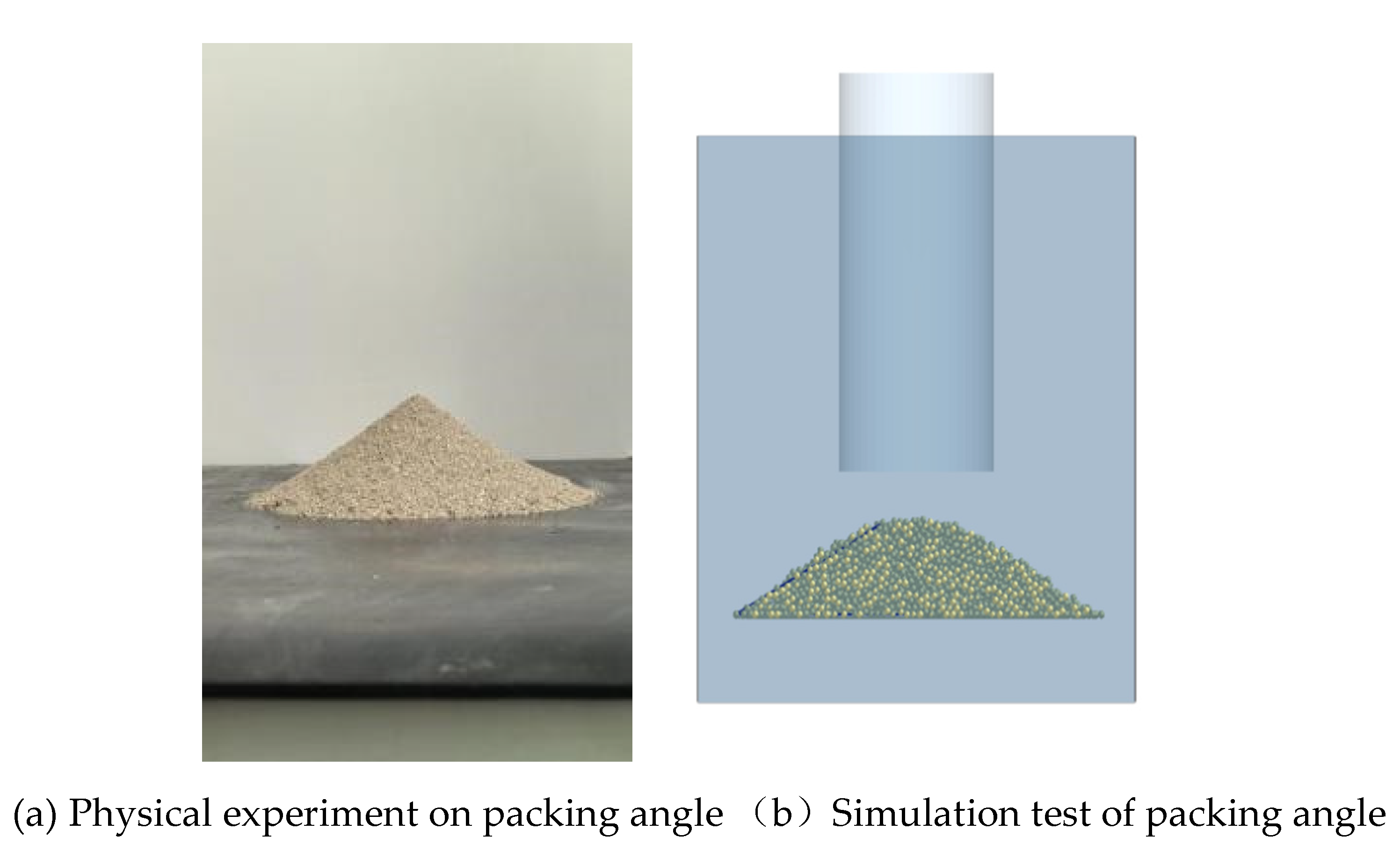

2.2.4. Angle of Restraint Test

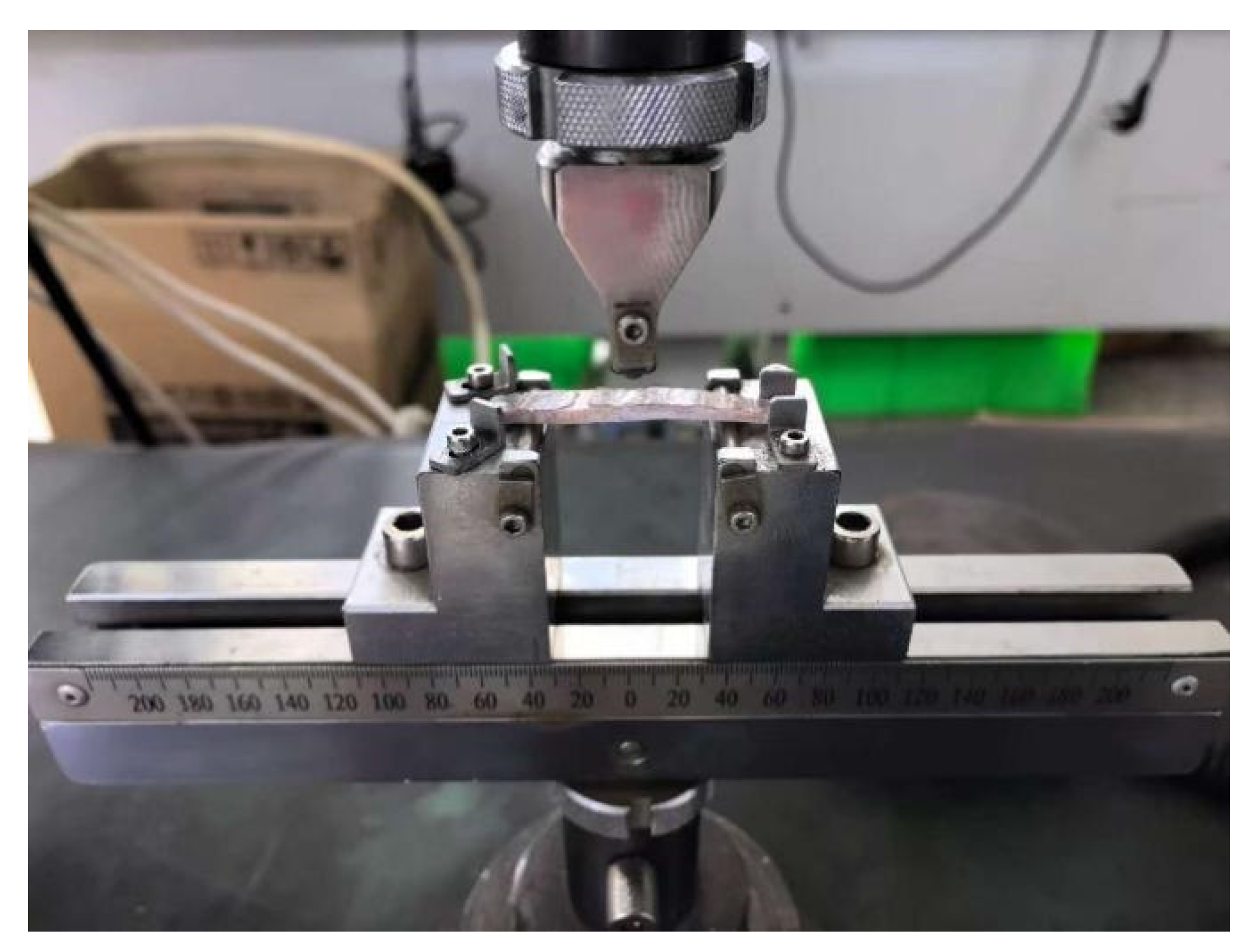

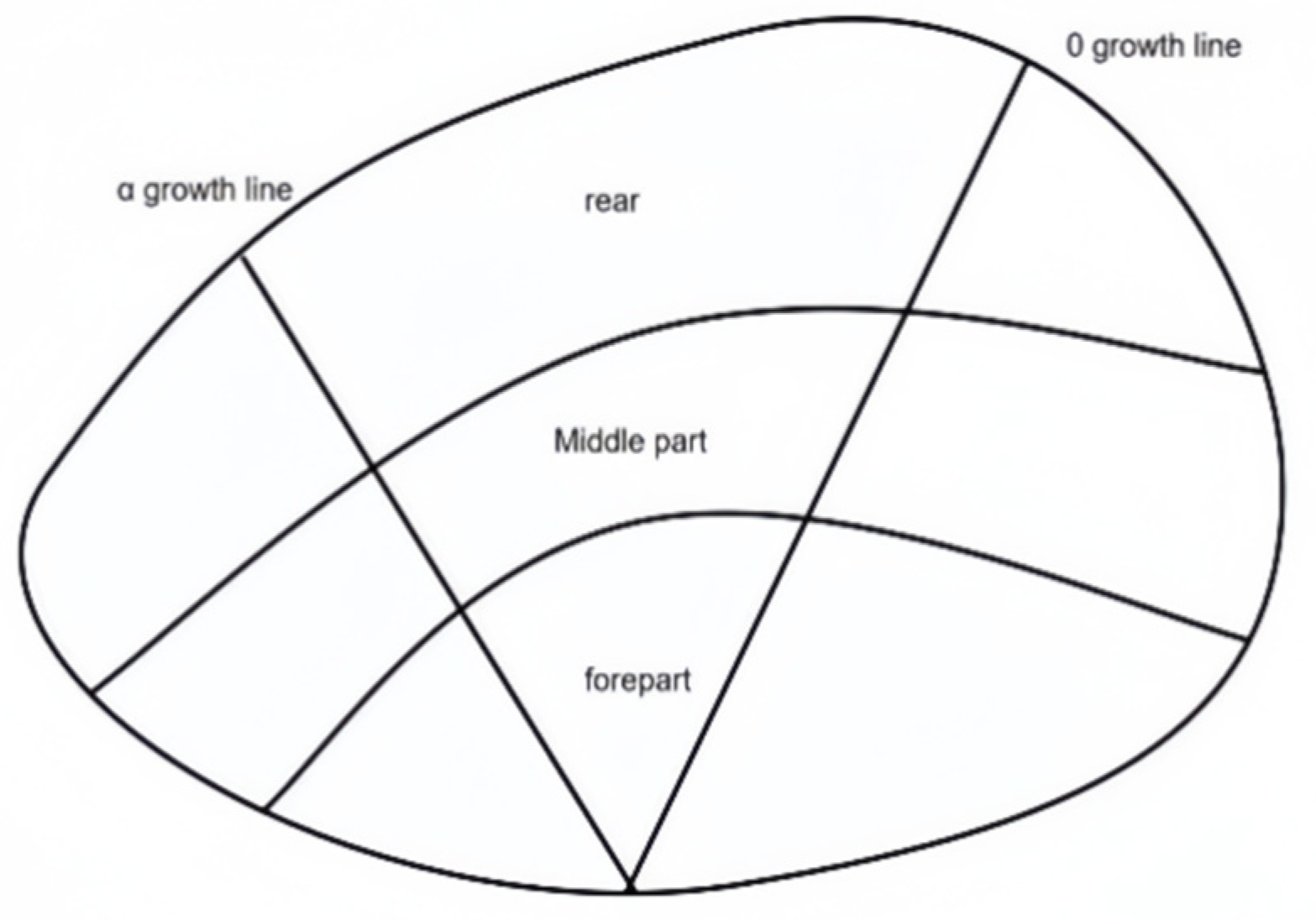

2.3. Three-Point Bending Failure Test and Bongding Model Parameters

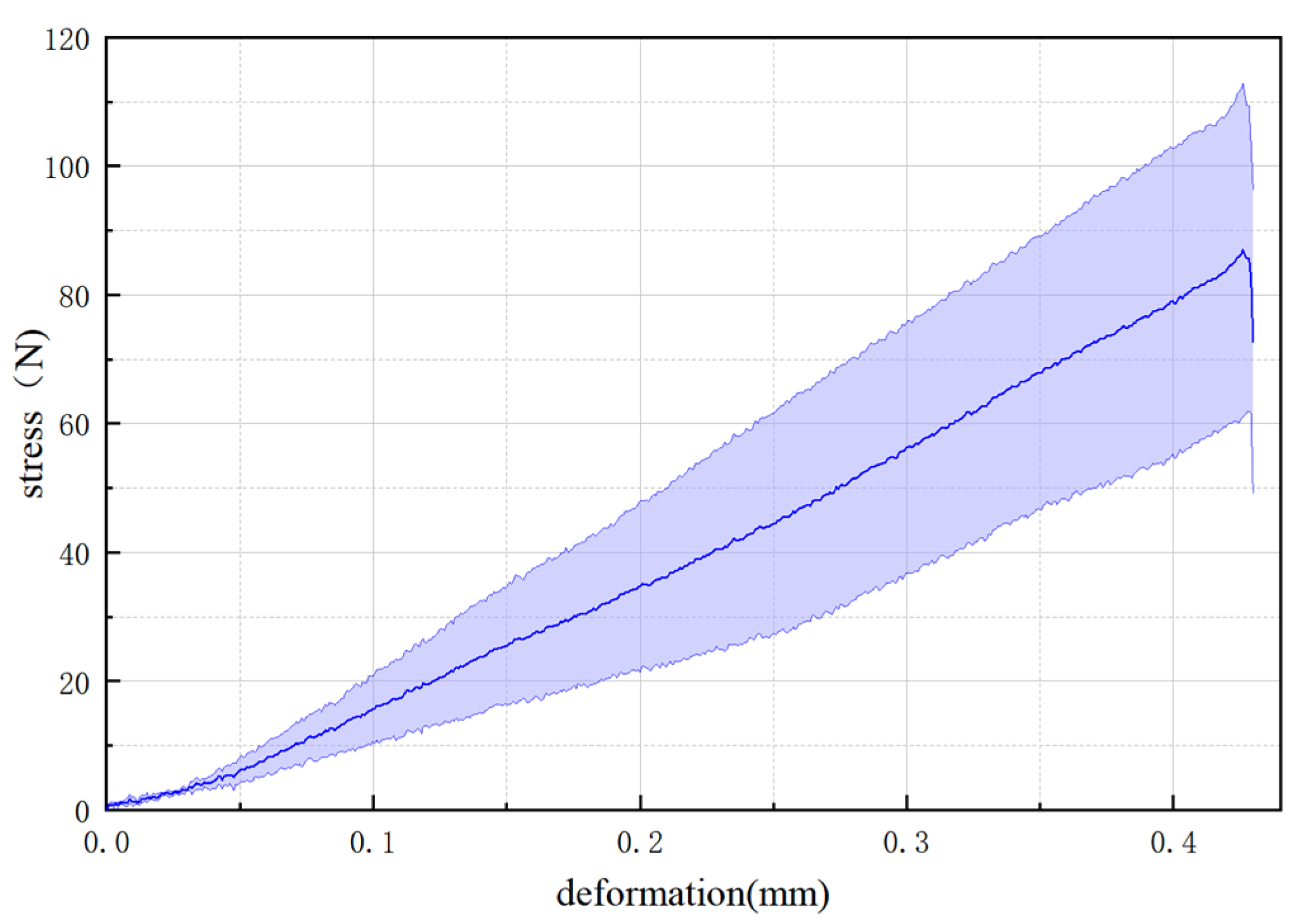

2.3.1. Three-Point Bending Test

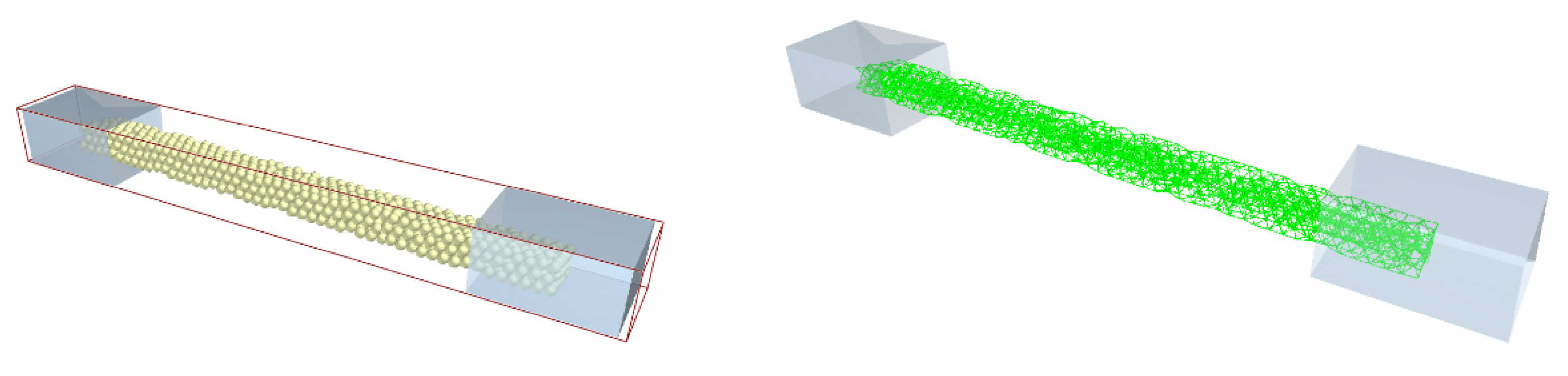

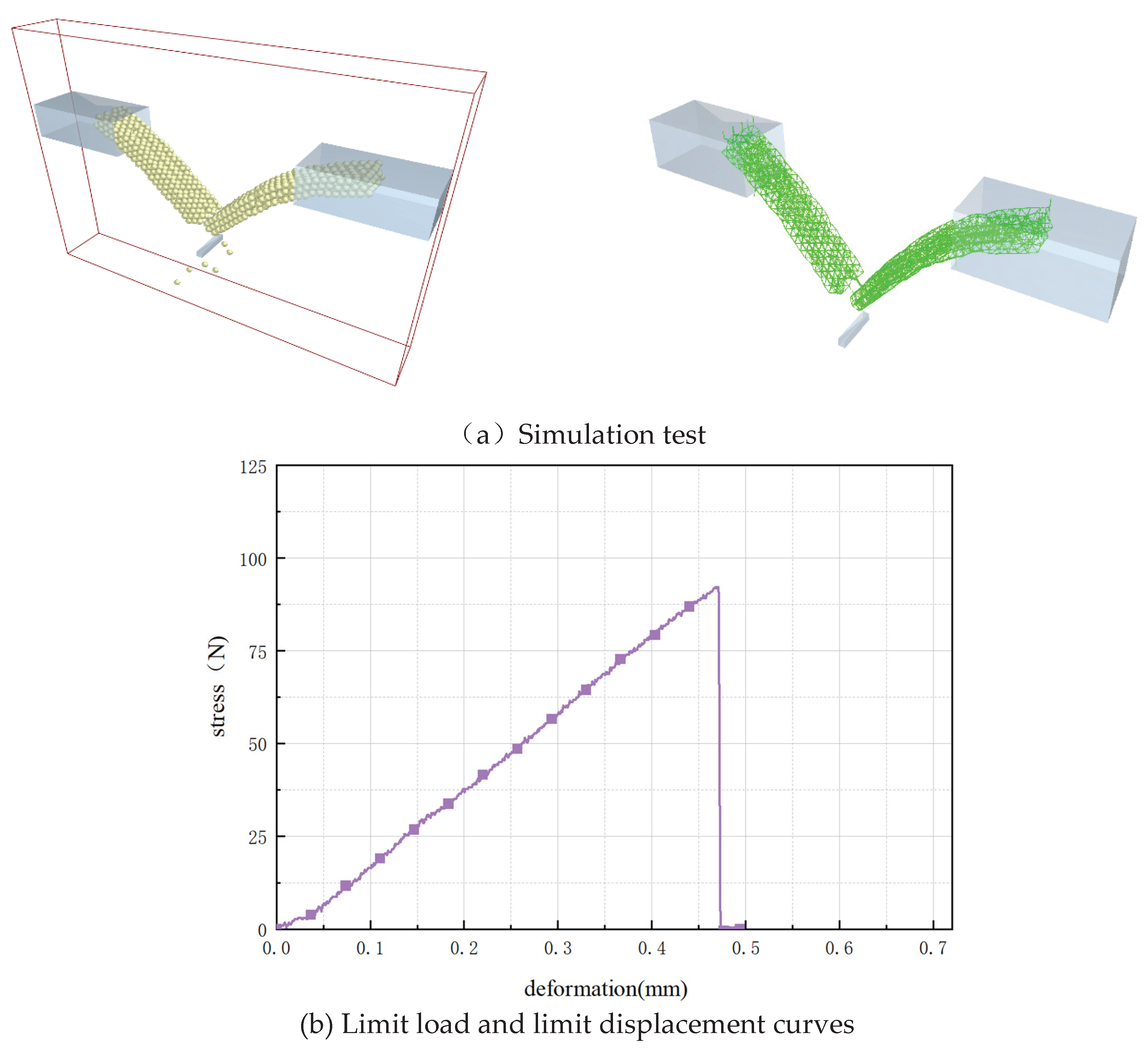

2.3.2. Establishment of a Three-Point Bending Test Simulation Model

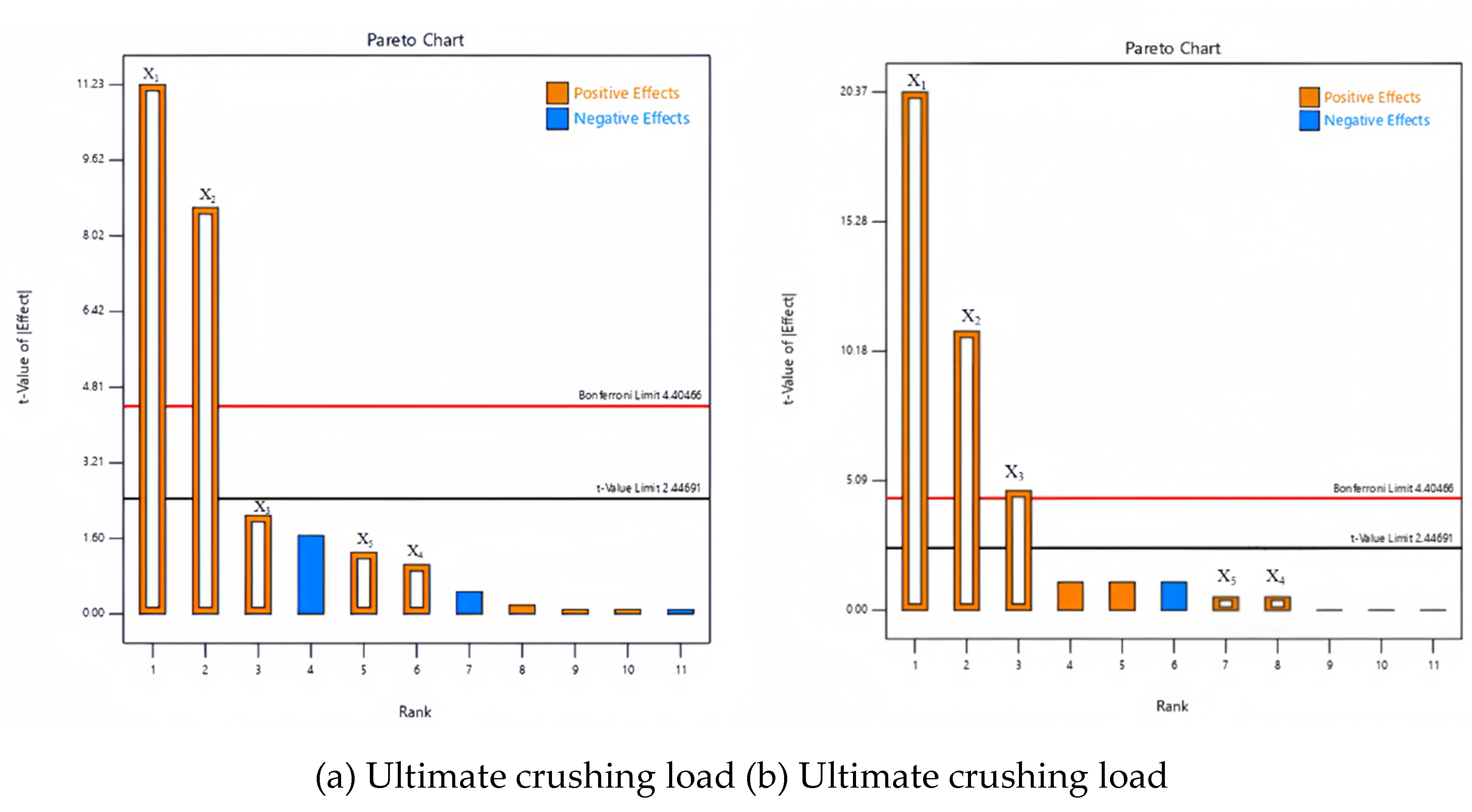

2.3.3. Plackett-Burman Experiment

2.3.4. Hill-Climbing Test

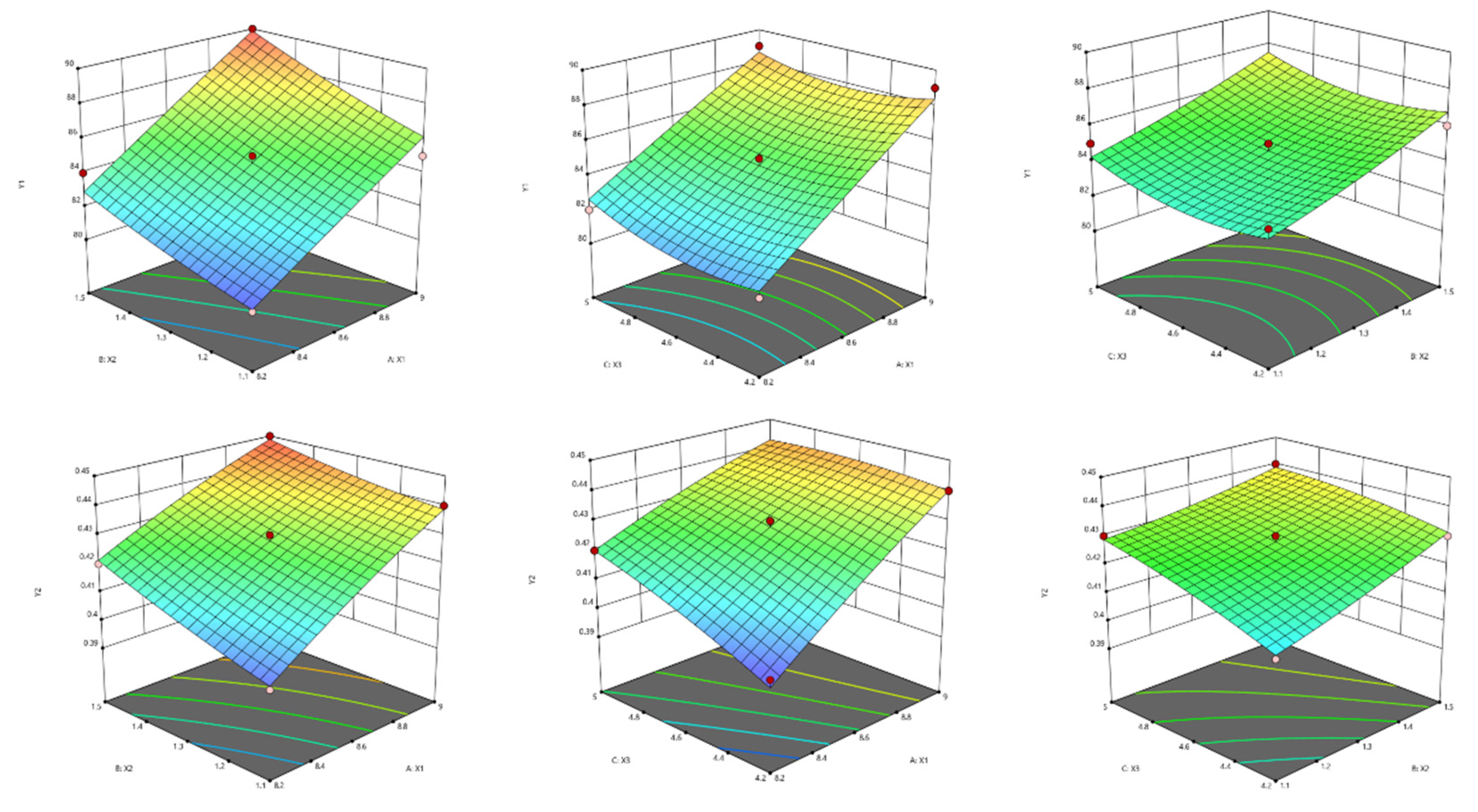

2.3.5. Response Surface Experiment

2.3.6. Verification Test

3. Conclusions

- (1)

- The intrinsic parameters of the shells were determined through the experimental method. The three-dimensional size range of the shells was measured. Due to the diverse shapes of the shells, shell samples of the same size had to be fabricated. The density was measured to be 2.2 kg/m³ using the drainage method. Through uniaxial compression tests and calculations, the Poisson's ratio, shear modulus, and elastic modulus of the shells were obtained, which were 0.26, 1.57×10^8 Pa, and 6.5×10^10 Pa, respectively.

- (2)

- The static friction coefficient, rolling friction coefficient, and collision recovery coefficient between shells and shells were measured by the inclined plane method and collision tests, which were 0.944, 0.129, and 0.242 respectively. The static friction coefficient, rolling friction coefficient, and collision recovery coefficient between shells and 304 stainless steel were 0.349, 0.081, and 0.367 respectively. The reliability of the data was verified by the angle of repose test. The shape of the shells has a significant influence on the accumulation angle in the actual test, and the test results cannot be accurately obtained. Therefore, shell powder was used. The relative error between the simulated values and the real values was 5.1%. This indicates that the data is reliable.

- (3)

- Using the actual ultimate load as the response value, the Bonding parameters were calibrated by the simulation approximation prediction method. Through the Plackett-Burman experimental design, the normal stiffness and tangential stiffness were selected as the significant parameters affecting the ultimate load. The range of significance parameters for calibration was narrowed by the steepest ascent test. On this basis, the Box-Behnken experimental design method and variance analysis were adopted to precisely calibrate the two significant parameters in the Bonding model. Finally, the optimal parameter combination was obtained: the unit area normal stiffness, the unit area tangential stiffness, the critical normal stress, the critical tangential stress, and the bonding radius, which were 8.26×10^10 N/m^3, 1.116×10^10 N/m^3, 4.438×10^7 Pa, 4×10^7 Pa, and 0.5 mm respectively. The error compared with the actual test was 3.8%, verifying the reliability of the shell modeling and the calibrated parameters.

Acknowledgments

References

- QIAN J, FUJING DENG, SHUMWAY S E, 等. The thick-shell mussel Mytilus coruscus: Ecology, physiology, and aquaculture[J/OL]. Aquaculture, 2024, 580: 740350. [CrossRef]

- WANG F, WALL G. Mudflat development in Jiangsu Province, China: Practices and experiences[J/OL]. Ocean & Coastal Management, 2010, 53(11): 691-699. [CrossRef]

- CHUANG H C, WANG S Y, CHENG A C. Research on and application of low-temperature calcination on waste Taiwanese hard clam shell during Taiwanese hard clam aquaculture[J/OL]. Aquaculture, 2024, 590: 741048. [CrossRef]

- XIAOLEI F, GUANGCE W, DEMAO L, 等. Study on early-stage development of conchospore in Porphyra yezoensis Ueda[J/OL]. Aquaculture, 2008, 278(1-4): 143-149. [CrossRef]

- FAKAYODE O, A. Size-based physical properties of hard-shell clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) shell relevant to the design of mechanical processing equipment[J/OL]. Aquacultural Engineering, 2020, 89: 102056. [CrossRef]

- DERKACH S, KRAVETS P, KUCHINA Y, 等. Mineral-free biomaterials from mussel (Mytilus edulis L.) shells: Their isolation and physicochemical properties[J/OL]. Food Bioscience, 2023, 56: 103188. [CrossRef]

- IWASE K, HARUNARI Y, TERAMOTO M, 等. Crystal structure, microstructure, and mechanical properties of heat-treated oyster shells[J/OL]. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, 2023, 147: 106107. [CrossRef]

- LV J, JIANG Y, ZHANG D. Structural and Mechanical Characterization of Atrina Pectinata and Freshwater Mussel Shells[J/OL]. Journal of Bionic Engineering, 2015, 12(2): 276-284. [CrossRef]

- OSA J L, MONDRAGON G, ORTEGA N, 等. On the friability of mussel shells as abrasive[J/OL]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2022, 375: 134020. [CrossRef]

- 基于科学计量的中国农业工程研究热点探析_师丽娟[Z].

- 离散元法在农业工程研究中的应用现状和展望_曾智伟[Z].

- MARAVEAS C, TSIGKAS N, BARTZANAS T. Agricultural processes simulation using discrete element method: a review[J/OL]. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2025, 237: 110733. [CrossRef]

- HAN D, TANG C, LIU B, 等. Hierarchical model acquisition and parameter calibration of the corncob based on the discrete element method[J/OL]. Advanced Powder Technology, 2025, 36(7): 104932. [CrossRef]

- 茶茎秆离散元模型参数标定与试验_杜哲[Z].

- 冷鲜波尔山羊肋骨弯曲破坏离散元参数标定_卫佳[Z].

- 莲藕主藕体弯曲破坏离散元仿真分析_焦俊[Z].

- 基于离散元法的牛肉咀嚼破碎模型构建_王笑丹[Z].

- 玉米秸秆-牛粪混料离散元仿真参数标定与试验_马永财[Z].

- CHEN G, WANG Q, LI H, 等. Rapid acquisition method of discrete element parameters of granular manure and validation[J/OL]. Powder Technology, 2024, 431: 119071. [CrossRef]

- 健胃消食颗粒物性参数测定与离散元仿真参数标定_王子千[Z].

- 基于离散元法的面粉颗粒接触参数标定试验_陈硕[Z].

- 基于离散元法的香菇菌渣颗粒仿真物理参数标定_李震[Z].

- 基于单轴密闭压缩试验的草炭离散元参数标定_王斌斌[Z].

- SCHRAMM M, TEKESTE M Z, PLOUFFE C, 等. Estimating bond damping and bond Young’s modulus for a flexible wheat straw discrete element method model[J/OL]. Biosystems Engineering, 2019, 186: 349-355. [CrossRef]

- SADRMANESH V, CHEN Y. Simulation of tensile behavior of plant fibers using the Discrete Element Method (DEM)[J/OL]. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 2018, 114: 196-203. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG S, ZHANG R, CAO Q, 等. A calibration method for contact parameters of agricultural particle mixtures inspired by the Brazil nut effect (BNE): The case of tiger nut tuber-stem-soil mixture[J/OL]. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2023, 212: 108112. [CrossRef]

- DU C, HAN D, SONG Z, 等. Calibration of contact parameters for complex shaped fruits based on discrete element method: The case of pod pepper (Capsicum annuum)[J/OL]. Biosystems Engineering, 2023, 226: 43-54. [CrossRef]

- FANG M, YU Z, ZHANG W, 等. Friction coefficient calibration of corn stalk particle mixtures using Plackett-Burman design and response surface methodology[J/OL]. Powder Technology, 2022, 396: 731-742. [CrossRef]

- WANG S, YU Z, AORIGELE, 等. Study on the modeling method of sunflower seed particles based on the discrete element method[J/OL]. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2022, 198: 107012. [CrossRef]

- SHI Y, JIANG Y, WANG X, 等. A mechanical model of single wheat straw with failure characteristics based on discrete element method[J/OL]. Biosystems Engineering, 2023, 230: 1-15. [CrossRef]

- ZHAO W, CHEN M, XIE J, 等. Discrete element modeling and physical experiment research on the biomechanical properties of cotton stalk[J/OL]. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2023, 204: 107502. [CrossRef]

- SCHRAMM M, TEKESTE M Z. Wheat straw direct shear simulation using discrete element method of fibrous bonded model[J/OL]. Biosystems Engineering, 2022, 213: 1-12. [CrossRef]

- LEBLICQ T, SMEETS B, RAMON H, 等. A discrete element approach for modelling the compression of crop stems[J/OL]. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2016, 123: 80-88. [CrossRef]

- CHEN F, YUAN H, LIU Z, 等. DEM simulation of an impact crusher using the fast-cutting breakage model[J/OL]. Powder Technology, 2025, 450: 120442. [CrossRef]

- SAAVEDRA L M, BASTÍAS M, MENDOZA P, 等. Environmental correlates of oyster farming in an upwelling system: Implication upon growth, biomass production, shell strength and organic composition[J/OL]. Marine Environmental Research, 2024, 198: 106489. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG C, HU J, XU Q, 等. Mechanical properties and energy evolution mechanism of wheat grain under uniaxial compression[J/OL]. Journal of Stored Products Research, 2024, 108: 102392. [CrossRef]

- GÜLER C, SARIKAYA A, SERTKAYA A A, 等. Almond shell particle containing particleboard mechanical and physical properties[J/OL]. Construction and Building Materials, 2024, 431: 136565. [CrossRef]

- KANAKABANDI C K, GOSWAMI T K. Determination of properties of black pepper to use in discrete element modeling[J/OL]. Journal of Food Engineering, 2019, 246: 111-118. [CrossRef]

- XUAN S, ZHAN C, LIU Z. A multi-bonding and damage model for spherical discrete element method[J/OL]. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, 2025, 179: 106387. [CrossRef]

- OTTESEN M A, LARSON R A, STUBBS C J, 等. A parameterised model of maize stem cross-sectional morphology[J/OL]. Biosystems Engineering, 2022, 218: 110-123. [CrossRef]

- GUO Y, WASSGREN C, HANCOCK B, 等. Validation and time step determination of discrete element modeling of flexible fibers[J/OL]. Powder Technology, 2013, 249: 386-395. [CrossRef]

- SUN W, SUN Y, WANG Y, 等. Calibration and experimental verification of discrete element parameters for modelling feed pelleting[J/OL]. Biosystems Engineering, 2024, 237: 182-195. [CrossRef]

| Level | Factors | ||||

| X1/(N·m-3) | X2/(N·m-3) | X3/Pa | X4/Pa | X5/mm | |

| Low | 7×1010 | 5×109 | 3×107 | 3×107 | 0.95 |

| High | 9×1010 | 1.5×1010 | 5×107 | 5×107 | 1.05 |

| Serial Number | X1/(N·m-3) | X2/(N·m-3) | X3/Pa | X4/Pa | X5/mm | Fmax/N | Smax/mm |

| 1 | 9×1010 | 1.5×1010 | 3×107 | 3×107 | 0.95 | 87 | 0.44 |

| 2 | 7×1010 | 5×109 | 5×107 | 3×107 | 1.05 | 64 | 0.36 |

| 3 | 7×1010 | 5×109 | 3×107 | 5×107 | 0.95 | 63 | 0.34 |

| 4 | 9×1010 | 1.5×1010 | 5×107 | 3×107 | 0.95 | 90 | 0.45 |

| 5 | 7×1010 | 5×109 | 3×107 | 3×107 | 0.95 | 62 | 0.34 |

| 6 | 7×1010 | 1.5×1010 | 3×107 | 5×107 | 1.05 | 78 | 0.39 |

| 7 | 9×1010 | 1.5×1010 | 3×107 | 5×107 | 1.05 | 88 | 0.45 |

| 8 | 9×1010 | 5×109 | 5×107 | 5×107 | 1.05 | 82 | 0.42 |

| 9 | 9×1010 | 5×109 | 3×107 | 3×107 | 1.05 | 81 | 0.40 |

| 10 | 9×1010 | 5×109 | 5×107 | 5×107 | 0.95 | 82 | 0.42 |

| 11 | 7×1010 | 1.5×1010 | 5×107 | 3×107 | 1.05 | 79 | 0.39 |

| 12 | 7×1010 | 1.5×1010 | 5×107 | 5×107 | 0.95 | 78 | 0.39 |

| Source of variance | Fmax | ||||

| Sum of Squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F | P | |

| Model | 1014.33 | 5 | 202.87 | 41.50 | 0.0001** |

| X1 | 616.33 | 1 | 616.33 | 126.07 | <0.0001** |

| X2 | 363 | 1 | 363.00 | 74.25 | 0.0001** |

| X3 | 21.33 | 1 | 21.33 | 4.36 | 0.0817 |

| X4 | 5.33 | 1 | 5.33 | 1.09 | 0.3365 |

| X5 | 8.33 | 1 | 8.33 | 1.70 | 0.2395 |

| Residual | 29.33 | 6 | 4.89 | ||

| Total sum | 1043.67 | 11 | |||

| Source of variance | Smax | ||||

| Sum of Squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F | P | |

| Model | 0.0170 | 5 | 0.0034 | 111.55 | <0.0001** |

| X1 | 0.0127 | 1 | 0.0127 | 414.82 | <0.0001** |

| X2 | 0.0037 | 1 | 0.0037 | 120.27 | <0.0001** |

| X3 | 0.0007 | 1 | 0.0007 | 22.09 | 0.0033** |

| X4 | 8.333E-06 | 1 | 8.333E-06 | 0.2727 | 0.6202 |

| X5 | 8.33E-06 | 1 | 8.333E-06 | 0.2727 | 0.6202 |

| Residual | 0.0002 | 6 | 0.00000 | ||

| Total sum | 0.0172 | 11 | |||

| Serial Number | X1(N·m-3) | X2(N·m-3) | X3(Pa) | Fmax(N) | Dmax(mm) | Relative error |

| 1 | 7*1010 | 5*109 | 3*107 | 64 | 0.36 | 23.4% |

| 2 | 7.4*1010 | 7*109 | 3.4*107 | 69 | 0.36 | 17.4% |

| 3 | 7.8*1010 | 9*109 | 3.8*107 | 74 | 0.37 | 11.4% |

| 4 | 8.2*1010 | 1.1*1010 | 4.2*107 | 80 | 0.4 | 4.2% |

| 5 | 8.6*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 4.6*107 | 85 | 0.43 | 1.8% |

| 6 | 9*1010 | 1.5*1010 | 5*107 | 90 | 0.45 | 7.8% |

| Serial Number | X1(N·m-3) | X2(N·m-3) | X3(Pa) | Fmax/N | Smax/mm |

| 1 | 9*1010 | 1.5*1010 | 4.6*107 | 90 | 0.45 |

| 2 | 8.6*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 4.6*107 | 84 | 0.43 |

| 3 | 9*1010 | 1.1*1010 | 4.6*107 | 85 | 0.44 |

| 4 | 8.6*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 4.6*107 | 84 | 0.42 |

| 5 | 9*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 5*107 | 89 | 0.44 |

| 6 | 8.2*1010 | 1.5*1010 | 4.6*107 | 84 | 0.42 |

| 7 | 8.6*1010 | 1.5*1010 | 5*107 | 87 | 0.44 |

| 8 | 8.2*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 4.2*107 | 81 | 0.40 |

| 9 | 8.6*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 4.6*107 | 85 | 0.43 |

| 10 | 8.6*1010 | 1.1*1010 | 5*107 | 85 | 0.43 |

| 11 | 8.6*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 4.6*107 | 85 | 0.43 |

| 12 | 8.6*1010 | 1.5*1010 | 4.2*107 | 86 | 0.43 |

| 13 | 8.2*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 5*107 | 82 | 0.42 |

| 14 | 8.6*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 4.6*107 | 85 | 0.43 |

| 15 | 9*1010 | 1.3*1010 | 4.2*107 | 89 | 0.44 |

| 16 | 8.6*1010 | 1.1*1010 | 4.2*107 | 84 | 0.41 |

| 17 | 8.2*1010 | 1.1*1010 | 4.6*107 | 80 | 0.40 |

| Source of variance | Fmax | ||||||||

| Sum of Squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F | P | |||||

| Model | 109.55 | 9 | 12.17 | 13.21 | 0.0013** | ||||

| X1 | 84.50 | 1 | 84.50 | 91.71 | <0.0001** | ||||

| X2 | 21.12 | 1 | 21.12 | 22.93 | 0.0020** | ||||

| X3 | 1.12 | 1 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.3057 | ||||

| X1X2 | 0.2500 | 1 | 0.2500 | 0.2713 | 0.6185 | ||||

| X1X3 | 0.2500 | 1 | 0.2500 | 0.2713 | 0.6185 | ||||

| X2X3 | 0.0000 | 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | ||||

| X12 X22 X32 |

0.0105 0.1684 2.06 |

1 1 1 |

0.0105 0.1684 2.06 |

0.0114 0.1828 2.24 |

0.9179 0.6818 0.1782 |

||||

| Residual | 6.45 | 7 | 0.9214 | ||||||

| Misfitting item | 5.25 | 3 | 1.75 | 5.83 | 0.0607 | ||||

| Total sum | 116.00 | 16 | |||||||

| R2=0.9444 R2Adj=0.8729 | |||||||||

| Source of variance | Smax | ||||||||

| Sum of Squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F | P | |||||

| Model | 0.0030 | 9 | 0.0003 | 22.58 | 0.0002** | ||||

| X1 | 0.0021 | 1 | 0.0021 | 140.83 | <0.0001** | ||||

| X2 | 0.0004 | 1 | 0.0004 | 30.00 | 0.0009** | ||||

| X3 | 0.0003 | 1 | 0.0003 | 20.83 | 0.0026** | ||||

| X1X2 | 0.0000 | 1 | 0.0000 | 1.67 | 0.2377 | ||||

| X1X3 | 0.0001 | 1 | 0.0001 | 6.67 | 0.0364* | ||||

| X2X3 | 0.0000 | 1 | 0.0000 | 1.67 | 0.2377 | ||||

| X12 X22 X32 |

9.474E-06 4.211E-06 9.474E-06 |

1 1 1 |

9.474E-06 4.211E-06 9.474E-06 |

0.6316 0.2807 0.6316 |

0.4529 0.6126 0.4529 |

||||

| Residual | 0.0001 | 7 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| Misfitting item | 0.0000 | 3 | 8.333E-06 | 0.4167 | 0.7510 | ||||

| Total sum | 0.0032 | 16 | |||||||

| R2=0.9667 R2Adj=0.9239 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).