Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

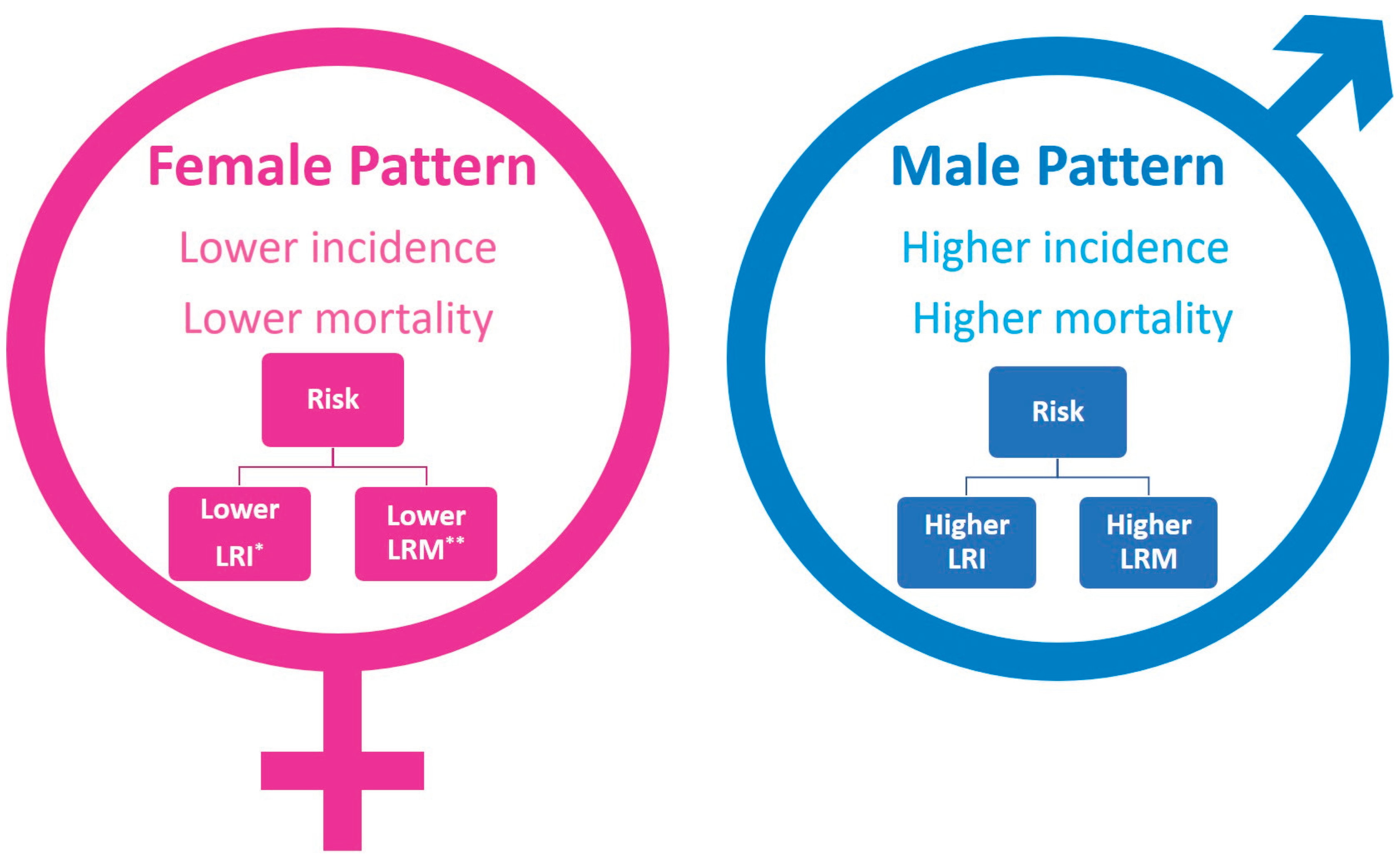

2. Incidence of Leukemia in Males and Females

3. Mortality of Leukemia Patients

4. Sex Specific Patterns in Leukemia

5. Survival Rate of Leukemia PATIENTS

6. Sex-Based Risk Factors

6.1. Environmental, Lifestyle, and Parental Risk Factors

6.2. Genetic Risk Factors

7. Epigenetic Patterns in Males and Females

8. Sex-Based Hematological and Biochemical Profiles

9. Sex-Specific Metabolites in Leukemia

10. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Sex Differences in Leukemia

11. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Man, J.; Zhang, T.; Yin, X.; He, Q.; Lu, M. Secular Trends in the Incidence and Survival of All Leukemia Types in the United States from 1975 to 2017. J Cancer 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rifat, R.H.; Poran, Md.S.; Islam, S.; Sumaya, A.T.; Alam, Md.M.; Rahman, M.R. Incidence, Mortality, and Epidemiology of Leukemia in South Asia: An Ecological Study. Open J Epidemiol 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Filho, A.; Piñeros, M.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Monnereau, A.; Bray, F. Epidemiological Patterns of Leukaemia in 184 Countries: A Population-Based Study. Lancet Haematol 2018, 5. [CrossRef]

- Bertuccio, P.; Bosetti, C.; Malvezzi, M.; Levi, F.; Chatenoud, L.; Negri, E.; Vecchia, C. La Trends in Mortality from Leukemia in Europe: An Update to 2009 and a Projection to 2012. Int J Cancer 2013, 132. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tang, H.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, H. The Current Situation and Future Trend of Leukemia Mortality by Sex and Area in China. Front Public Health 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Jani, C. Mapping Incidence and Mortality of Leukemia and Its Subtypes in 21 World Regions in Last Three Decades and Projections to 2030. Ann Hematol 2022, 101. [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Chen, W.; Liu, K.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Mao, Y.; Sun, X.; Luo, Y.; Shi, J.; Shao, K.; et al. The Global Burden of Leukemia and Its Attributable Factors in 204 Countries and Territories: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study and Projections to 2030. J Oncol 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Stabellini, N.; Tomlinson, B.; Cullen, J.; Shanahan, J.; Waite, K.; Montero, A.J.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Hamerschlak, N. Sex Differences in Adults with Acute Myeloid Leukemia and the Impact of Sex on Overall Survival. Cancer Med 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.B. The Spectrum of Sex Differences in Cancer. Trends Cancer 2022, 8.

- Özdemir, B.C.; Richters, A.; Oertelt-Prigione, S.; Adjei, A.A.; Borchmann, S.; Haanen, J.B.A.G.; Letsch, A.; Quaas, A.; Verhoeven, R.H.A.; Wagner, A.D. 1592P Awareness and Interest of Oncology Professionals in Sex and Gender Differences in Cancer Risk and Outcome: Analysis of an ESMO Gender Medicine Task Force Survey. Annals of Oncology 2024, 35, S959. [CrossRef]

- Kammula, A. V; Schäffer, A.A.; Rajagopal, P.S.; Kurzrock, R.; Ruppin, E. Outcome Differences by Sex in Oncology Clinical Trials. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2608.

- van Eldik, M.J.A.; Ali, M.; Rietkerken, S.; Peters, S.A.E.; den Ruijter, H.M.; Ruigrok, Y.M. Underreporting of Sex-Specific Findings in Risk Factors for Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. Cerebrovascular Diseases 2025.

- Jaime-Pérez, J.C.; Hernández-De Los Santos, J.A.; Fernández, L.T.; Padilla-Medina, J.R.; Gómez-Almaguer, D. Sexual Dimorphism in Children and Adolescents with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Influence on Incidence and Survival. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2020, 42, e293–e298. [CrossRef]

- Stabellini, N.; Tomlinson, B.; Cullen, J.; Shanahan, J.; Waite, K.; Montero, A.J.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Hamerschlak, N. Sex Differences in Adults with Acute Myeloid Leukemia and the Impact of Sex on Overall Survival. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 6711–6721. [CrossRef]

- Chennamadhavuni, A.; Lyengar, V.; Mukkamalla, S.K.R. Leukemia - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. Ncbi 2023.

- NIH Cancer Stat Facts. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program 2022.

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2025. Ca 2025, 75, 10.

- Namayandeh, S.M.; Khazaei, Z.; Najafi, M.L.; Goodarzi, E.; Moslem, A. GLOBAL Leukemia in Children 0-14 Statistics 2018, Incidence and Mortality and Human Development Index (HDI): GLOBOCAN Sources and Methods. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263.

- Sharma, R.; Jani, C. Mapping Incidence and Mortality of Leukemia and Its Subtypes in 21 World Regions in Last Three Decades and Projections to 2030. Ann Hematol 2022, 101, 1523–1534.

- Amini, M.; Sharma, R.; Jani, C. Gender Differences in Leukemia Outcomes Based on Health Care Expenditures Using Estimates from the GLOBOCAN 2020. Archives of public health 2023, 81, 151.

- Sun, K.; Wu, H.; Zhu, Q.; Gu, K.; Wei, H.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Wu, C.; Chen, R.; Pang, Y. Global Landscape and Trends in Lifetime Risks of Haematologic Malignancies in 185 Countries: Population-Based Estimates from GLOBOCAN 2022. EClinicalMedicine 2025, 83.

- Osman, A.E.G.; Deininger, M.W. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Modern Therapies, Current Challenges and Future Directions. Blood Rev 2021, 49, 100825.

- Sasaki, K.; Strom, S.S.; O’Brien, S.; Jabbour, E.; Ravandi, F.; Konopleva, M.; Borthakur, G.; Pemmaraju, N.; Daver, N.; Jain, P. Relative Survival in Patients with Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia in the Tyrosine-Kinase Inhibitor Era: Analysis of Patient Data from Six Prospective Clinical Trials. Lancet Haematol 2015, 2, e186–e193.

- Li, Y.; Zeng, P.; Xiao, J.; Huang, P.; Liu, P. Modulation of Energy Metabolism to Overcome Drug Resistance in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells through Induction of Autophagy. Cell Death Discov 2022, 8, 212.

- Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Zou, Z.; Xu, L.; Li, J. Crosstalk between Autophagy and Metabolism: Implications for Cell Survival in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell Death Discov 2024, 10, 46.

- Beaudet, M.-E.; Szuber, N.; Moussa, H.; Harnois, M.; Assouline, S.E.; Busque, L. Sex-Related Differences in CML Outcomes in a Real-World Prospective Registry (GQR LMC-NMP). Blood 2024, 144, 533.

- Catovsky, D.; Wade, R.; Else, M. The Clinical Significance of Patients’ Sex in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Haematologica 2014, 99. [CrossRef]

- Meeske, K.A.; Ji, L.; Freyer, D.R.; Gaynon, P.; Ruccione, K.; Butturini, A.; Avramis, V.I.; Siegel, S.; Matloub, Y.; Seibel, N.L.; et al. Comparative Toxicity by Sex Among Children Treated for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015, 62. [CrossRef]

- Meeske, K.A.; Ji, L.; Freyer, D.R.; Gaynon, P.; Ruccione, K.; Butturini, A.; Avramis, V.I.; Siegel, S.; Matloub, Y.; Seibel, N.L.; et al. Comparative Toxicity by Sex Among Children Treated for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 2140 – 2149. [CrossRef]

- Jastaniah, W.; Elimam, N.; Abdalla, K.; AlAzmi, A.A.; Aseeri, M.; Felimban, S. High-Dose Methotrexate vs. Capizzi Methotrexate for the Treatment of Childhood T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Leuk Res Rep 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Dorak, M.T.; Karpuzoglu, E. Gender Differences in Cancer Susceptibility: An Inadequately Addressed Issue. Front Genet 2012, 3, 268.

- Ober, C.; Loisel, D.A.; Gilad, Y. Sex-Specific Genetic Architecture of Human Disease. Nat Rev Genet 2008, 9, 911–922.

- Delahousse, J.; Wagner, A.D.; Borchmann, S.; Adjei, A.A.; Haanen, J.; Burgers, F.; Letsch, A.; Quaas, A.; Oertelt-Prigione, S.; Oezdemir, B.C. Sex Differences in the Pharmacokinetics of Anticancer Drugs: A Systematic Review. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 104002.

- Paltiel, O.; Ratnasingam, S.; Lee, H. Are We Ignoring Sex Differences in Haematological Malignancies? A Call for Improved Reporting. Br J Haematol 2025, 206, 1315–1329.

- of Washington, U. Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). Http://Ghdx.Healthdata.Org/Gbd-Results-Tool?Params=Gbd-Api-2019-Permalink/D780Dffbe8a381B25E1416884959E88B 2019.

- Du, M.; Chen, W.; Liu, K.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Mao, Y.; Sun, X.; Luo, Y.; Shi, J.; Shao, K.; et al. The Global Burden of Leukemia and Its Attributable Factors in 204 Countries and Territories: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study and Projections to 2030. J Oncol 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kharazmi, E.; Liang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K.; Fallah, M. Maternal Weight during Pregnancy and Risk of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Offspring: ACUTE LYMPHOBLASTIC LEUKEMIA. Leukemia 2025, 39, 590–598. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.S.; Hammal, D.M.; Dorak, M.T.; McNally, R.J.Q.; Parker, L. Paternal Occupational Exposure to Electro-Magnetic Fields as a Risk Factor for Cancer in Children and Young Adults: A Case-Control Study from the North of England. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007, 49, 280–286. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Morales, A.L.; Zonana-Nacach, A.; Zaragoza-Sandoval, V.M. Associated Risk Factors in Acute Leukemia in Children. A Cases and Controls Study; [Factores Asociados a Leucemia Aguda En Niños. Estudio de Casos y Controles.]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 2009, 47, 497 – 503.

- Radivoyevitch, T.; Jankovic, G.M.; Tiu, R. V; Saunthararajah, Y.; Jackson, R.C.; Hlatky, L.R.; Gale, R.P.; Sachs, R.K. Sex Differences in the Incidence of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Radiat Environ Biophys 2014, 53, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Lupo, P.J.; Scheurer, M.E.; Saxena, A.; Kennedy, A.E.; Ibrahimou, B.; Barbieri, M.A.; Mills, K.I.; McCauley, J.L.; Okcu, M.F.; et al. A Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Novel Sex-Specific Risk Variants. Medicine (United States) 2016, 95. [CrossRef]

- Al-absi, B.; Noor, S.M.; Saif-Ali, R.; Salem, S.D.; Ahmed, R.H.; Razif, M.F.M.; Muniandy, S. Association of ARID5B Gene Variants with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Yemeni Children. Tumor Biology 2017, 39. [CrossRef]

- Bolufer, P.; Collado, M.; Barragán, E.; Cervera, J.; Calasanz, M.-J.; Colomer, D.; Roman-Gómez, J.; Sanz, M.A. The Potential Effect of Gender in Combination with Common Genetic Polymorphisms of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes on the Risk of Developing Acute Leukemia. Haematologica 2007, 92, 308 – 314. [CrossRef]

- Meissner, B.; Bartram, T.; Eckert, C.; Trka, J.; Panzer-Grümayer, R.; Hermanova, I.; Ellinghaus, E.; Franke, A.; Möricke, A.; Schrauder, A.; et al. Frequent and Sex-Biased Deletion of SLX4IP by Illegitimate V(D)J-Mediated Recombination in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23, 590–601. [CrossRef]

- Van Vlierberghe, P.; Palomero, T.; Khiabanian, H.; Van Der Meulen, J.; Castillo, M.; Van Roy, N.; De Moerloose, B.; Philippé, J.; González-García, S.; Toribio, M.L.; et al. PHF6 Mutations in T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Nat Genet 2010, 42, 338–342. [CrossRef]

- Van Vlierberghe, P.; Patel, J.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Lobry, C.; Hedvat, C. V; Balbin, M.; Nicolas, C.; Payer, A.R.; Fernandez, H.F.; Tallman, M.S.; et al. PHF6 Mutations in Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Leukemia 2011, 25, 130–134. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meulen, J.; Sanghvi, V.; Mavrakis, K.; Durinck, K.; Fang, F.; Matthijssens, F.; Rondou, P.; Rosen, M.; Pieters, T.; Vandenberghe, P.; et al. The H3K27me3 Demethylase UTX Is a Gender-Specific Tumor Suppressor in T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood 2015, 125, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Lafta, S.A.; Abdulhassan, I.A. Prevalence of Classification of Nucleophosmin 1 Gene Mutations in Iraqi Cohort of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Journal of Applied Hematology 2025, 16, 74–80. [CrossRef]

- Ozga, M.; Nicolet, D.; Mrózek, K.; Yilmaz, A.S.; Kohlschmidt, J.; Larkin, K.T.; Blachly, J.S.; Oakes, C.C.; Buss, J.; Walker, C.J.; et al. Sex-Associated Differences in Frequencies and Prognostic Impact of Recurrent Genetic Alterations in Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia (Alliance, AMLCG). Leukemia 2024, 38, 45–57. [CrossRef]

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of AML in Adults: 2022 Recommendations from an International Expert Panel on Behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140. [CrossRef]

- Radkiewicz, C.; Bruchfeld, J.B.; Weibull, C.E.; Jeppesen, M.L.; Frederiksen, H.; Lambe, M.; Jakobsen, L.; El-Galaly, T.C.; Smedby, K.E.; Wästerlid, T. Sex Differences in Lymphoma Incidence and Mortality by Subtype: A Population-Based Study. Am J Hematol 2023, 98. [CrossRef]

- Molica, S. Sex Differences in Incidence and Outcome of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Patients. Leuk Lymphoma 2006, 47.

- Hu, D.; Shilatifard, A. Epigenetics of Hematopoiesis and Hematological Malignancies. Genes Dev 2016, 30, 2021–2041.

- Cullen, S.M.; Mayle, A.; Rossi, L.; Goodell, M.A. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Development: An Epigenetic Journey. Curr Top Dev Biol 2014, 107, 39–75.

- Rubin, J.B.; Abou-Antoun, T.; Ippolito, J.E.; Llaci, L.; Marquez, C.T.; Wong, J.P.; Yang, L. Epigenetic Developmental Mechanisms Underlying Sex Differences in Cancer. J Clin Invest 2024, 134.

- Dinardo, C.D.; Gharibyan, V.; Yang, H.; Wei, Y.; Pierce, S.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Rytting, M. Impact of Aberrant DNA Methylation Patterns Including CYP1B1 Methylation in Adolescents and Young Adults with Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia. Am J Hematol 2013, 88, 784–789. [CrossRef]

- Cecotka, A.; Krol, L.; O’Brien, G.; Badie, C.; Polanska, J. May Gender Have an Impact on Methylation Profile and Survival Prognosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia? In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; 2022; Vol. 325 LNNS, pp. 126–135.

- Lin, S.; Liu, Y.; Goldin, L.R.; Lyu, C.; Kong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Caporaso, N.E.; Xiang, S.; Gao, Y. Sex-Related DNA Methylation Differences in B Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Biol Sex Differ 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, F.M.; Nafea, D.A.; El-Attar, L.M.; Saied, M.H. Epigenetic Silencing of the DAPK1 Gene in Egyptian Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Meta Gene 2020, 26, 100779.

- Tollefsbol, T. Personalized Epigenetics; Elsevier, 2024; ISBN 0443238030.

- Khalid, A.; Ahmed, M.; Hasnain, S. Biochemical and Hematologic Profiles in B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2023, 45, E867–E872. [CrossRef]

- Izu, A.; Yanagida, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Fujita, S.; Okada, M.; Takemura, T. Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis and Partial Deletion of Chromosome 6p: A Case Report. Clin Nephrol 2011, 76. [CrossRef]

- Sá, A.C.M.G.N. de; Bacal, N.S.; Gomes, C.S.; Silva, T.M.R. da; Gonçalves, R.P.F.; Malta, D.C. Blood Count Reference Intervals for the Brazilian Adult Population: National Health Survey. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia 2023, 26, e230004.

- Tefferi, A.; Hanson, C.A.; Inwards, D.J. How to Interpret and Pursue an Abnormal Complete Blood Cell Count in Adults. Mayo Clin Proc 2005, 80.

- Duarte, D. da S.; Teixeira, E.B.; de Oliveira, M.B.; Carneiro, T.X.; Leão, L.B.C.; Mello Júnior, F.A.R.; Carneiro, D.M.; Nunes, P.F.; Cohen-Paes, A.; Alcantara, D.D.F.Á.; et al. Hematological and Biochemical Characteristics Associated with Cytogenetic Findern Alterations in Adult Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) from the Northern Region of Brazil. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Munker, R.; Hill, U.; Jehn, U.; Kolb, H.J.; Schalhorn, A. Renal Complications in Acute Leukemias. Haematologica 1998, 83.

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, L.S. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Complicated by Acute Renal Failure: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin Nephrol 2010, 73. [CrossRef]

- Berger, U.; Maywald, O.; Pfirmann, M.; Lahaye, T.; Hochhaus, A.; Reiter, A.; Hasford, J.; Heimpel, H.; Hossfeld, D.K.; Kolb, H.-J.; et al. Gender Aspects in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Long-Term Results from Randomized Studies. Leukemia 2005, 19, 984–989. [CrossRef]

- Addisia, G.D.; Tegegne, A.S.; Belay, D.B.; Muluneh, M.W.; Kassaw, M.A. Risk Factors of White Blood Cell Progression Among Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Cancer Inform 2022, 21, 11769351211069902.

- Advani, A. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL). Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2017, 30, 173–174.

- Niaz, H.; Malik, H.S.; Mahmood, R.; Mehmood, A.; Zaidi, S.A.; Nisar, U. CLINICO-HAEMATOLOGIC PARAMETERS AND ASSESSMENT OF POST-INDUCTION STATUS IN ACUTE LYMPHOBLASTIC LEUKAEMIA. Journal of Ayub Medical College 2022, 34. [CrossRef]

- Pujari, K.N.; Jadkar, S.P.; Belwalkar, G.J. Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels in Leukemias. 2012, 3, B454–B459.

- Gemmati, D.; Varani, K.; Bramanti, B.; Piva, R.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Trentini, A.; Manfrinato, M.C.; Tisato, V.; Carè, A.; Bellini, T. “Bridging the Gap” Everything That Could Have Been Avoided If We Had Applied Gender Medicine, Pharmacogenetics and Personalized Medicine in the Gender-Omics and Sex-Omics Era. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 21, 296.

- Wishart, D.S.; Jewison, T.; Guo, A.C.; Wilson, M.; Knox, C.; Liu, Y.; Djoumbou, Y.; Mandal, R.; Aziat, F.; Dong, E. HMDB 3.0—the Human Metabolome Database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 41, D801–D807.

- Szczepski, K.; Al-Younis, I.; Dhahri, M.; Lachowicz, J.I.; Al-Talla, Z.A.; Almahasheer, H.; Alasmael, N.; Rahman, M.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, Ł.; et al. Metabolic Biomarkers in Cancer. In Metabolomics: A Path Towards Personalized Medicine; 2023; pp. 173–198.

- Petrick, L.; Imani, P.; Perttula, K.; Yano, Y.; Whitehead, T.; Metayer, C.; Schiffman, C.; Dolios, G.; Dudoit, S.; Rappaport, S. Untargeted Metabolomics of Newborn Dried Blood Spots Reveals Sex-Specific Associations with Pediatric Acute Myeloid Leukemia. 2021, 106. [CrossRef]

- Allain, E.P.; Venzl, K.; Caron, P.; Turcotte, V.; Simonyan, D.; Gruber, M.; Le, T.; Lévesque, E.; Guillemette, C.; Vanura, K. Sex-Dependent Association of Circulating Sex Steroids and Pituitary Hormones with Treatment-Free Survival in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Patients. 2018, 97, 1649–1661. [CrossRef]

- Bond, K.M.; McCarthy, M.M.; Rubin, J.B.; Swanson, K.R. Molecular Omics Resources Should Require Sex Annotation: A Call for Action. Nat Methods 2021, 18, 585–588.

- Costanzo, M.; Caterino, M.; Sotgiu, G.; Ruoppolo, M.; Franconi, F.; Campesi, I. Sex Differences in the Human Metabolome. Biol Sex Differ 2022, 13, 30.

- Huh, J.; Moon, H.; Chung, W.S. Incidence and Clinical Significance of Sex Chromosome Losses in Bone Marrow of Patients with Hematologic Diseases. Korean J Lab Med 2007, 27. [CrossRef]

- Meulen, J. Van Der; Sanghvi, V.; Mavrakis, K.; Durinck, K.; Fang, F.; Matthijssens, F.; Rondou, P.; Rosen, M.; Pieters, T.; Vandenberghe, P.; et al. The H3K27me3 Demethylase UTX Is a Gender-Specific Tumor Suppressor in T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood 2015, 125. [CrossRef]

- Scotland, R.S.; Stables, M.J.; Madalli, S.; Watson, P.; Gilroy, D.W. Sex Differences in Resident Immune Cell Phenotype Underlie More Efficient Acute Inflammatory Responses in Female Mice. Blood 2011, 118. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.W.; Yap, H.K.; Chew, F.T.; Quah, T.C.; Prabhakaran, K.; Chan, G.S.H.; Wong, S.C.; Seah, C.C. Age- and Sex-Related Changes in Lymphocyte Subpopulations of Healthy Asian Subjects: From Birth to Adulthood. Communications in Clinical Cytometry 1996, 26. [CrossRef]

- Lisse, I.M.; Aaby, P.; Whittle, H.; Jensen, H.; Engelmann, M.; Christensen, L.B. T-Lymphocyte Subsets in West African Children: Impact of Age, Sex, and Season. Journal of Pediatrics 1997, 130. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Chai, P.S.; Chong, M.Y.; Tohit, E.R.M.; Ramasamy, R.; Pei, C.P.; Vidyadaran, S. Gender Effect on in Vitro Lymphocyte Subset Levels of Healthy Individuals. Cell Immunol 2012, 272. [CrossRef]

- Uppal, S.S.; Verma, S.; Dhot, P.S. Normal Values of CD4 and CD8 Lymphocyte Subsets in Healthy Indian Adults and the Effects of Sex, Age, Ethnicity, and Smoking. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2003, 52. [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex Differences in Immune Responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2016, 16, 626–638.

- Bupp, M.R.G.; Potluri, T.; Fink, A.L.; Klein, S.L. The Confluence of Sex Hormones and Aging on Immunity. Front Immunol 2018, 9.

- Dierlamm, J.; Michaux, L.; Criel, A.; Wlodarska, I.; Zeller, W.; Louwagie, A.; Michaux, J. -L; Mecucci, C.; Berghe, H. Van Den Isodicentric (X)(Q13) in Haematological Malignancies: Presentation of Five New Cases, Application of Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH) and Review of the Literature. Br J Haematol 1995, 91. [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka, A.; Smoley, S.; Fink, S.; Sanchez, J.; Dyke, D.L. Van; Dewald, G. Isochromosome (X)(P10) in Hematologic Disorders: FISH Study of 14 New Cases Show Three Types of Centromere Signal Patterns. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2007, 179. [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, M.; Halvardson, J.; Davies, H.; Moghadam, B.T.; Mattisson, J.; Rychlicka-Buniowska, E.; Jaszczyński, J.; Heintz, J.; Lannfelt, L.; Giedraitis, V.; et al. Longitudinal Changes in the Frequency of Mosaic Chromosome Y Loss in Peripheral Blood Cells of Aging Men Varies Profoundly between Individuals. European Journal of Human Genetics 2020, 28. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Watson, N.; Sharma, P. Frequency of Trisomy 15 and Loss of the Y Chromosome in Adult Leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1999, 114. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C. Mosaic Loss of Chromosome Y Promotes Leukemogenesis and Clonal Hematopoiesis. JCI Insight 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Snell, D.M.; Turner, J.M.A. Sex Chromosome Effects on Male–Female Differences in Mammals. Current Biology 2018, 28.

- Kovats, S. Estrogen Receptors Regulate Innate Immune Cells and Signaling Pathways. Cell Immunol 2015, 294. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.C.; Garratt, M.G. Life History Evolution, Reproduction, and the Origins of Sex-Dependent Aging and Longevity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2017, 1389. [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, N.; Rafiee, M.; Azaryan, E.; Wilkinson, D.; Bagheri, V. Inhibitory Effects of Progesterone on the Human Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cell Line. Gene Rep 2024, 36, 101991.

- Taneja, V. Sex Hormones Determine Immune Response. Front Immunol 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

| Mechanism | Female characteristics | Male characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Factors Sex chromosomes (XX vs. XY) |

Idic(X)(q13) is the most frequently observed structural anomaly of the X chromosome in hematologic malignancies [90]. This chromosomal abnormality has been reported exclusively in older female patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), chronic myeloproliferative disorders, and AML [90,91]. |

The most common chromosomal abnormality in adult male blood cells is mosaic loss of chromosome Y (mLOY) [92]. Leukocyte mLOY is a risk factor for hematological malignancies, such as myelodysplastic syndrome, ALL, and AML[93]. mLOY functionally drives leukemogenesis and clonal hematopoiesis [94]. |

| Epigenetic factors | The epigenetic modifier lysine demethylases KDM6A (UTX), which escapes X-chromosome inactivation, is expressed at higher levels in females [95]. In T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, KDM6A has been identified as a tumor suppressor [82]. |

Notably, UTX mutations were observed exclusively in male T-ALL patients [82]. UTX is the first identified X-linked tumor suppressor gene that may partially account for the skewed gender distribution (3:1) toward males in T-ALL on a genetic level [82]. |

| Innate immunity | Females have higher numbers of macrophages and neutrophils, resulting in greater phagocytic activity [83]. | Males have higher numbers of natural killer cells than females [83]. |

| Adaptive immunity | Females have higher levels of circulating CD4 T cells and B cells [84,85,86,87]. |

Males have higher levels of CD8 T cells [84,85,86,87]. |

| Sex hormones | Females have higher levels of progesterone and estrogen [96]. Estrogen receptors are detected in immune cell types such as lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages [96], which have protective properties and immunostimulant effects [97]. Progesterone could be effective in growth-inhibiting NALM6 cells by decreasing cell viability and lowering ROS levels [98]. |

Males have higher testosterone concentrations [96]. Testosterone has immunosuppressive effects [99] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).