1. Introduction

Productivity is power, but to unleash its full potential, there is every need to beat the demon of unproductiveness and noetic inertia. Since it is a power, it has the ability to influence and affect states of people’s mind. Both individuals and organisations largely exploit the power of productivity to effect profitable outcomes. Today, improvements in productivity are sought everywhere to enhance our dynamic capabilities. Productivity improvement techniques include various sets of inclusive agendas and strategies including traditional and modern techniques and tools that explains some of the factors contributing to productivity enhancements (Daniels, 1997). In this paper, we introduce a new conceptual view of human productivity and its enhancement: overcoming cognitive constraints that lead to mental fatigue and loss of performance. But first, it is imperative to have a clear understanding of the term productivity: what productivity is and what it is not.

We all can tell what productivity is and what it’s being like to be productive. A clear “productive” definition of productivity can help explain it further to help us grasp its true essence.

“Productivity is the accomplishment of actions that lead to efficient, fruitful outcomes. It denotes production of activities which makes one visible.”

Human productivity is associated with three distinct concepts: mental energy, mental effort and mental fatigue. The amount of useful, free energy available to a mind is limited. Too much mental effort or prolonged hours of cognitive exertion can lead to both mental and physical fatigue. Of these, mental fatigue has more damaging influence on performance (Deli and Kisvardey, 2020), for it has been repeatedly observed that even when physical energy is exhausted, individuals still withstand to carry on with the remaining amount of mental energy which drives the body to action. We call it grit, or never-give-up attitude. This mental energy is necessary for productivity and proactivity, and it is something beyond simple willpower. It is our mental strength—the power of the mind.

Human beings often waste a large amount of mental energy and dump it through negative behaviors and actions: e.g., violence, rage, anger, blame, criticism, etc (Deli and Kisvardey, 2020). Individuals should strive to conserve mind energy for productive work, where low entropy (more amount of energy available for work) is an ideal state for achieving success. Energy wasted in ‘useless activities’ is no longer available for ‘useful activities’: i.e., entropy. Also, when energy is exhausted, fatigue arise. It limits our cognitive performance. Here, motivation is an endogenous factor that can generate the amount of mental energy necessary to sustain and remain productive to effect minimal loss of performance due to cognitive exhaustion. But there’s a limit to such sustenance.

1.1. Motivation at Workplace: A Positive Energiser

Motivation is an intrinsic factor which generates positive mental energy where it is made available for productive purposes. Hence, motivation at workplace is a necessary factor to remain productive. Besides, motivation at workplace is also derived from favourable working conditions that boost productivity and stimulate performance. It is more relevant to labour productivity in the economic sectors (Leonidova & Ivanovskaya, 2021).

“More comfortable working conditions result in better performance and augment workforce productivity to a greater extent.”

Hence, motivation in the productive space is an important factor to consider when we talk about labor productivity. On the other hand, under different contexts of performance and testing, the effect of mental fatigue on performance is related to different levels of control preparedness, as evident from the study conducted by Lindner et al., (2025). Mental fatigue is bound to arise during prolonged cognitive exercise and cognitive performance, but it varies noticeably among the performers due to the presence of fatigue vulnerability traits in different degrees among different individuals (Lindner et. al., 2025).

1.2. Factors of Productivity: Extrinsic and Intrinsic Factors

Power dwells in the mind which drives us to become proactive. The objects of productive powers are natural, instinctive in nature. Or, they may exist outside the mind in the form of latent potential (extrinsic factors) as wisdom, secrets, and special kind of knowledge. Motivation is an intrinsic factor that contributes to human productivity in action (Deli and Kisvardey, 2020). Productivity helps in bringing individuals up to perform actions, accomplish set goals, and achieve ambitions. It is often argued that “necessity” is the mother of all discoveries and inventions, but I would fain say, it is also curiosity which is the cause of inventive productivity. It is our curious intent which often propels our will to action, towards productivity.

The productive intentions of the mind is a trait, which should be ignited and be kept kindled to serve the purpose of human curiosity, as well as necessity. Likewise, decisiveness, too, is a virtue of willpower, necessary for effectiveness of human actions (Szutta, 2020). Decisiveness inspires productivity. Two activities promote productivity to such a degree as well: training and practice. Both produce the knowledge and expertise necessary in the agent to help her become productive. Therefore, productivity is power, alike knowledge. This research relates to this aspect of productivity.

Training and practice strengthen our bond with actions. This is a deep philosophical statement linking practical training with action, since both training and practice are considered activities. Training directs attention to details, whereas practice creates the right ambience which sets the stage, and which aids in the development of productive habits (Clark, 2008). It instils confidence in the self. While productivity is a virtue—it is a quality trait usually found in individuals who strive hard to achieve their goals. Hence, it is necessary to cultivate a fertile mind in which ideas on productivity can flourish and develop. We do not endorse any ideological context in support of productivity, but stress on productive intents that set contexts. Hence, without moulding productivity by idealistic philosophy, it is necessary to express ideas in a productive way.

2. Productivity Is an Outcome

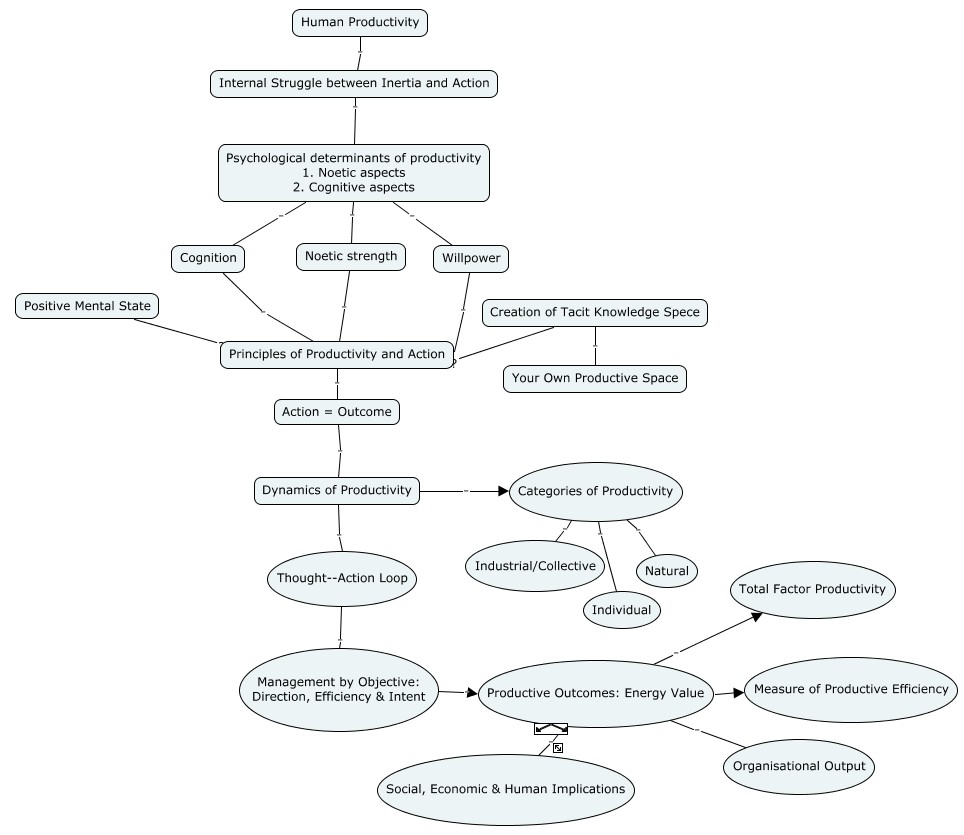

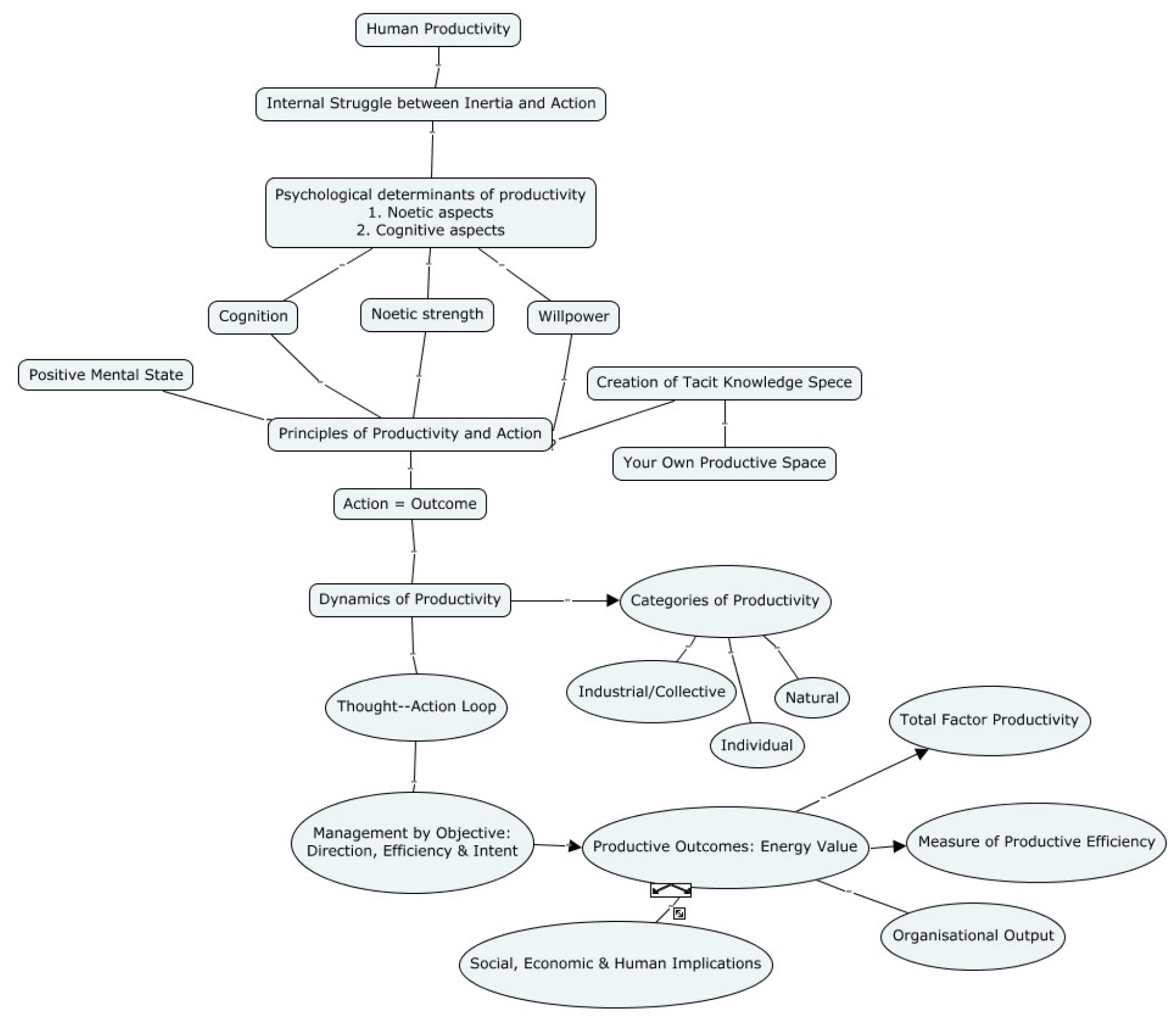

Productivity is the outcome of the effects of a struggle between inertia and action. At the noetic level, however, it is a struggle between several components of the mind—e.g., cognition, willpower, and mental strength that determine the physical principles of productivity. The goal is to rise above all obstacles to become productive where “being productive” is considered as a positive state of the mind. It thus throws productive lights on the conception of action, work, and human productive potential (Chatterjee, 2025a). Therefore, it is imperative to us for creating our own productive space if we don’t have one. Since there’s no action without interaction, so there’s no outcome without any action. In simple words, we can draw an allegorical construal which echoes Immanuel Kant’s idea (Soteriou, 2005)—“everything in mind acts where it is”.

Productivity, therefore, is the result of dynamic efforts (see Figure 1 above) made with the objective of achieving certain goals that establish a mutual relationship between thought and action (Shalley, 1995; Adler et al., 2009). The fundamental belief is that, productivity results in the production of energy value. It could mean productive dynamics of industrial organisations or relative productivity of individual employees. Here, the mode of productivity is of great importance since productivity can be classified into three major categories: industrial or collective productivity, individual, and natural productivity. The knowledge of productivity which a productive mode or process carries with it is an immense implication for society and people. Every method has its applications: whether they be productive or unproductive depends on the purpose and the intent of the producer/agent who’s is in action. Herein, the role of management by objective is an important criteria that determines organisational productivity (Ogochukwu et al., 2022). Special emphasis on the empirical side of productivity have been highlighted by many researchers who relate to the measurement of productivity—the prime focus being on total factor productivity and efficiency (See Grosskopf, 1993).

Figure 1.

SOCIAL, ORGANISATIONAL & HUMAN IMPLICATIONS OF PRODUCTIVITY.

Figure 1.

SOCIAL, ORGANISATIONAL & HUMAN IMPLICATIONS OF PRODUCTIVITY.

Signs of productivity generates a positive vibe which propels the agent into action, with advancement from one phase of productivity to another. This philosophy is dominated by the principles of absolute productivity—which states that, “the idea of productivity, whether it be abstract or real has its origin in the sources of productive wisdom of action.” Tracing this form of productive wisdom is an exploratory exercise, a practice for many individuals, and a sign of productivity for others characterising individual productiveness.

3. The Foundations of Productive Motivation

In this section, we shall examine the theory of productive motivation, and the role of motivation in triggering higher productivity (Srivastava & Barmola, 2011). Motivation is one of the primary means of inspiring productivity in employees (Sabir, 2017)). It is, by all means, coherent with the basic principles of the philosophy of productivity—that philosophy which evolves through practice and action. Motivations can be derived from the productive interpretations of this principle concerning clear understanding of what’s being learned, taught, or worked upon, or what’s need be done or accomplished.

Philosophy of productivity evolves in workplaces. Strategic protocols for the productive guidance of workforces reveal the forces in action which influence individuals in striving harder to achieve organizational goals and objectives. It would be futile to ignore the influence of a productive field on the outcome of efforts on the part of the employees that delineates the basic principles of the philosophy of productivity. According to Adair (2009), inspiring ideas propel individuals towards actions, and they help breed ambitions. Leaders, too, inspire their followers to actions. Great leaders create economic and social value (Beer, 2011). They are generally ambitious personalities. Ambitions motivate us to action which trigger our latent productive instincts. Whether motivations are effective in pushing individuals to perform better depends on the “nature of incentives” that drive productivity. Motivations are also derived from productive interpretations of successful actions that produced great effects in the past—the reason we are often inspired by history.

Productive motivations modulate the possibility of attaining success, albeit to some extent, as observed by researchers working in this field (Srivastava & Barmola, 2011). The chief goal is to organize the means and methods of activities and processes that become meaningful in the performance of industrious undertakings. It not only renders actions more productive but reveals by gradually unfolding the wisdom of action that seem effective and inspiring at the same time.

4. Motivations in The Productive Space

Is it necessary to be inspired or motivated to become productive? Do specially designed productive spaces motivate us to work better? For most individuals, their works bear the proof of their productiveness, for the works must be carried on as a rule to remain in action. Often, specific conditions must be met to inspire productivity, including incentive structures and favourable ambience—which promote productivity among the employees (Chatterjee, 2025b). Choosing an ideal if not the best place to work supports people in performing better.

Today, most companies are, in essence, buyer, seller, as well as developer of skills and expertise. They strive to excel in providing better products and services as much as they thrive in their efforts to serve better. Good firms are always in search of productive wisdom—the knowledge and intelligence that they need to compete and survive. Supply constraints and uncertainty in production frontier have become the things of the past—as they are ruled out at the very beginning of starting any business, and which cannot be relied upon for trade purposes. Profitable exploitation of the available talent pool of human resources has led to the development of complex incentive structures to motivate the workforces in action. Productive communication channels, decentralisation of operations, learning and information sharing have all led to the realisation of higher productivity across business organisations. And yet, many companies do fail to survive. Some of them cease to be productive, innovative, and creative—since productivity alone couldn’t be the sole factor of organisational success.

Indeed, there are things beyond productive power which we often face, and which we must manage to maintain in generous fashion the productive momentum of organisations. New means of advanced digital tools are created in effecting productivity in inefficient organisations to obtain maximum outcomes from given efforts. They also constitute “motivational tools” of productivity. In fact, organisations can increase their efficiency by strictly following effective guidelines to bring stability in their operations. This is a proven fact which is also a recognized truth, as observed by researchers working on operations research field (Adler et al., 2009). Much of the productivity improvement programme conform to such inclusive set of guidelines that need be followed to effect improvement in productivity (Baines, 1997).

“At the individual level, those who seamlessly adopt such techniques and tools become productive, too, to find heavy work a light task later on along their career paths.”

Effective practical habits do the job in strengthening our minds through augmenting productivity by tapping on our latent productive potential. If we are able to tap our potential, we can become more productive, provided that we nurture practical habits. Today, productive wisdom are communicated and conveyed with much ease and efficiency, and with more convenience all for the benefit of the employees. It is a motivating factor, after all. Organisations today strive hard to mould their productive spaces with positive vibes, creating environments of trust, harmony, equanimity and coordination, while turning their places into ideal spaces of productivity.

Firms do care to find in knowing what productive wisdom lay at the depth, so they dig more. They formulate strict routines that are effective for their incumbents to follow in making their workforces more productive. The idea of deep learning is a glowing example, as much for the reason being that both machines (AI agents) and human beings are now capable of going to the remotest depth in learning and thinking. Still, there are limits to human productivity, but which we continuously strive to surpass. It is, therefore, true that unproductiveness adds a terrible burden to organisational dynamics. To stimulate productivity, hence, organisations adopt various practices based on proven productive strategies to follow strict division of duties, craft strict protocols, generate guidelines, and emulate practices that have already proved beneficial to other organisations. All these steps render productive spaces more inspiring to their employees. Consequently, it may be correct to ascertain that motivation in the productive space is a much desirable factor: Inspired employees perform better, turning things around in their favor. Organisations create and put in place conditions that satisfy a higher optimum level of productivity to support business growth and expansion.

5. Productive Outcomes of Actions

Every possibility of a productive outcome—the results of actions performed with an aim to accomplish things of value and utility generalises the core concept of productivity. How that is possible could be explained in the following way: when we engage our attention and our intellect in a fruitful way on a dynamic, productive domain or field, achieving success in it becomes a possibility. Magnates, i.e., entrepreneurs and creative producers including artists are among those who serve as excellent examples exhibiting properties of high productiveness. Top scientists and scholars, including authors, too, show exceptional qualities of higher productiveness. It may be easier to relate productiveness to Parkinson’s Law1 which is a theory about “work that expands to fill the time available for doing it,” and which the great masters of productivity excel in accomplishing it. Since productivity is a power, there’s no need for any special theory to differentiate between productivity and unproductiveness, because it is an observable factor. What we can simply do is to place the science of productivity on a new scale. New measures of productivity are emerging whereas organisations are prioritising productive activities based on their intrinsic importance.

All we need to do is to act and perform according to a formal, productive, and efficient routine. Further guidance on the path could be obtained when one proceeds along with the intent and determination to succeed. The science of productive perfection rests on this principle which guides one in boosting performance towards attaining excellence. For this to occur, understanding productive specificity is essential. But what do we mean by productive specificity? It signifies devoting one’s entire “attention” and “effort” to specific goals which one wants to attain. As we have mentioned before, productive ability is a virtue. The outcomes of productivity modulates human expectations, but such expectations in turn influence future outcomes as well. This type of periphrastic relationship between outcome and expectation give shape to performance which individuals tend to perfect with, as they go about and progress through devoting themselves with determination to productive endeavors. This explains one part of the productive principle.

The other part relates to the performance of routine tasks that do not require perfection but help build productive habits in the long run. By birth, human beings are not virtuous nor productive, but some prodigious kids give evidences of inborn talents, and tend to be more productive than most others. However, it shall be kept in mind that productivity is an acquirable trait. Children learn to be so in order to attain higher capabilities by virtue of continuous practice and learning. Similarly, one’s claim to expertise is proved by one’s performance with regard to solving problems or accomplishing certain tasks successfully. Of course, virtue favor those who are hardworking. Here lay the positive influence of the effects of intelligence and wisdom on productivity. The wisdom of action influences the mind in a categorical manner. The influence of productive wisdom on the outcome of actions entail a determined engagement in productive practice. Of much importance in this case is Jean Piaget’s (Piaget, 1950 & 2000) theory of cognitive development in children, and Bandura’s (Bandura & Walters, 1977) social learning theories in relation to cognitive improvement.

6. Conclusion

Workplace environments do matter when it comes to securing better performances from the workers (Emmanuel, 2021). Motivation at workspace is an important factor that drives productivity of workers. Workplace motivation is a contributing factor towards attainment of success. When organisations ask for extra efforts, they must ensure that such efforts originate from encouragements and be rewarded in a like manner. There have always been incentives to inspire performance and productivity in private organisations. Organisations should also see that emerging cognitive constraints that lead to mental fatigue among the employees be properly dealt with, to ensure conservation of productive energy. To derive favorable productive outcomes from individuals, incentives alone are not enough, since individuals should themselves be a diligent and motivated lot, and beyond this, organisational ambience should play a positive role in inspiring performance and stimulate productivity. The power of productivity can only be unleashed given that individuals enjoy and love their work and find them interesting.

References

- Adair, J. (2009). The inspirational leader: How to motivate, encourage and achieve success. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Adler, P. S., Benner, M., Brunner, D. J., MacDuffie, J. P., Osono, E., Staats, B. R., ... & Winter, S. G. (2009). Perspectives on the productivity dilemma. Journal of Operations Management, 27(2), 99-113.

- Baines, A. (1997). Productivity improvement. Work study, 46(2), 49-51.

- Beer, M. (2011). Higher ambition: How great leaders create economic and social value. Harvard Business Press.

- Chatterjee, S. (2025a). The Foundations of Productive Potential.

- Chatterjee, S. (2025b). Conditions for Productivity: Reflections on the Choice of Actions.

- Clark, R. C. (2008). Building expertise: Cognitive methods for training and performance improvement. John Wiley & Sons.

- Daniels, S. (1997). Back to basics with productivity techniques. Work study, 46(2), 52-57.

- Déli, E., & Kisvárday, Z. (2020). The thermodynamic brain and the evolution of intellect: the role of mental energy. Cognitive neurodynamics, 14(6), 743-756. [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, O. O. (2021). The dynamics of work environment and its impact on organizational objectives. Annals of Human Resource Management Research, 1(2), 145-158.

- Jansen, Peter (2008). IT-Service-Management Volgens ITIL. Derde Editie. Pearson Education. p. 179. ISBN 978-90-430-1323-9.

- Leonidova, G. V., & Ivanovskaya, A. L. (2021). Working conditions as a factor of increasing its productivity in Russia's regions. Ekonomicheskie i Sotsialnye Peremeny, 14(3), 118-134.

- Lindner, C., Retelsdorf, J., Nagy, G., & Zitzmann, S. (2025). The waning willpower: A highly powered longitudinal study investigating fatigue vulnerability and its relation to personality, intelligence, and cognitive performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- Ogochukwu, O. E., Amah, E., & Okocha, B. F. (2022). Management by objective and organizational productivity: A literature review. South Asian Research Journal of Business and Management, 4(3), 99-113.

- Piaget, J. (1950). The psychology of intelligence. London, UK: Routledge.

- Piaget, J. (2000). Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. Childhood cognitive development: The essential readings, 2(7), 33-47.

- Sabir, A. (2017). Motivation: Outstanding way to promote productivity in employees. American Journal of Management Science and Engineering, 2(3), 35-40.

- Shalley, C. E. (1995). Effects of coaction, expected evaluation, and goal setting on creativity and productivity. Academy of Management journal, 38(2), 483-503.

- Soteriou, M. (2005). Mental action and the epistemology of mind. Noûs, 39(1), 83-105.

- Srivastava, S. K., & Barmola, K. C. (2011). Role of motivation in higher productivity. Management Insight, 7(1), 63-82.

- Szutta, N. (2020). The virtues of will-power–from a philosophical & psychological perspective. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 23(2), 325-339.

Notes

| 1 |

See Parkinson, Cyril Northcote (1958). Parkinson's Law, or The Pursuit of Progress. London: John Murray. A corollary to this law has been drawn which states that (Jansen, 2008), “Data expands to fill the space available for storage.” |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).