Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

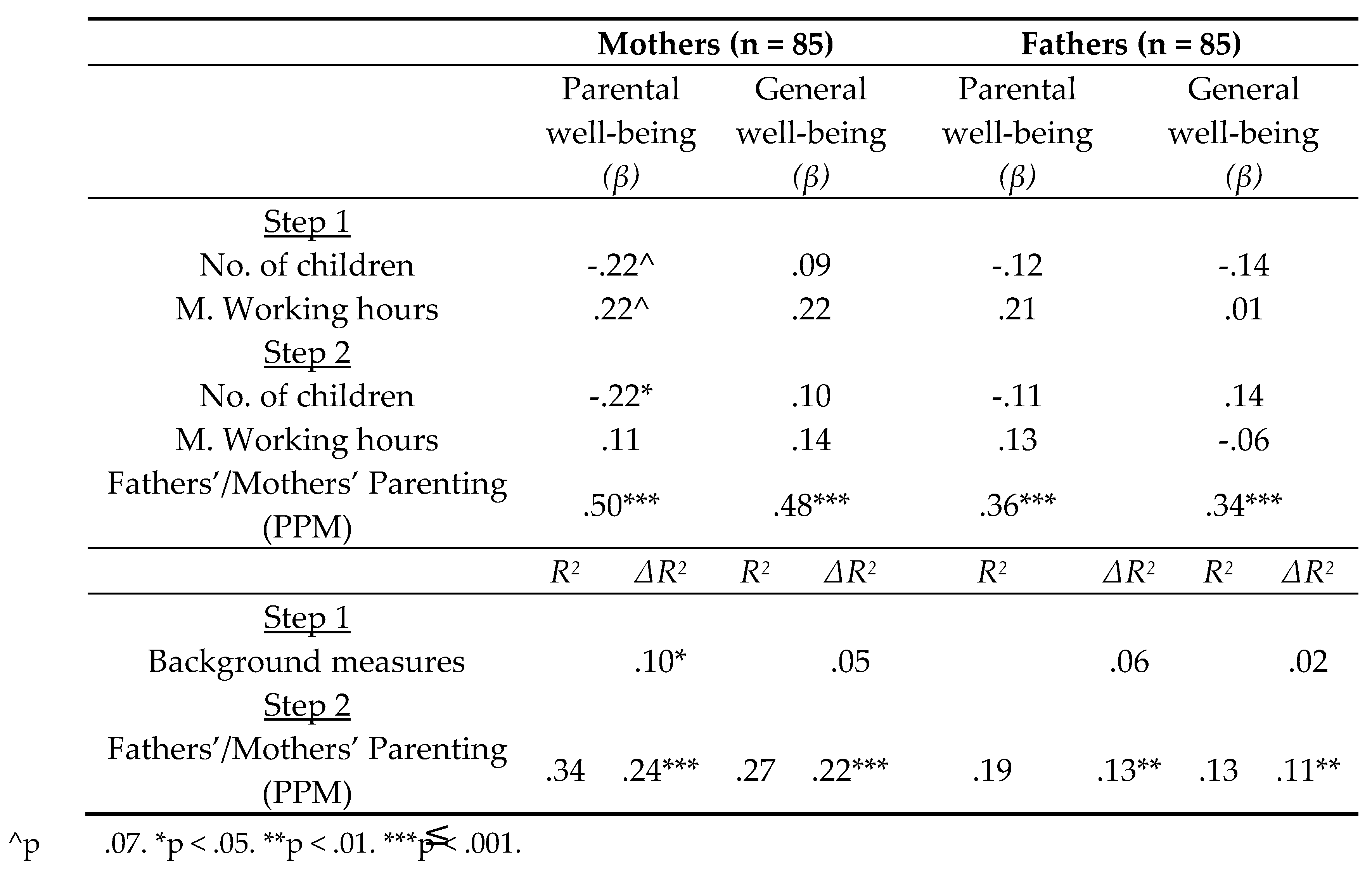

This study highlights the distinction between parents’ general well-being and parental well-being. It reveals the interplay between daily parenting behaviors and individual well-being, as well as the impact of one partner’s (particularly fathers’) behaviors on the other partner’s well-being. These findings contribute to broadening the discourse on parenting by shifting the focus beyond child outcomes to include the role of parenting behaviors in promoting parents’ own well-being and family resilience. This study examined mothers’ and fathers’ daily parenting behaviors through the lens of the Parenting Pentagon Model, which identifies five constructs of beneficial parenting: Partnership, Leadership, Expressions of Love, Encouraging Independence, and Adherence to Rules. The study explored the associations between parenting behaviors and parents’ general and parental well-being. Participants included 170 Israeli parents (85 couples) with young children aged six months to nine years. They completed self-report measures assessing parenting behaviors, well-being, and sociodemographic factors (e.g., family size, education, employment). Analyses explored how sociodemographic factors and parenting behaviors explain parental and general well-being within and across genders. Parents reported frequent beneficial parenting behaviors, with Love being the most prevalent. Mothers reported significantly higher Love behaviors, while other constructs showed no gender differences. Parenting behaviors strongly predicted well-being: Mothers’ behaviors explained 48% (parental) and 44% (general) of their well-being, while fathers’ behaviors explained 35% and 23%, respectively. Fathers’ behaviors more strongly predicted mothers’ well-being (24% parental, 22% general) than mothers’ behaviors predicted fathers’ well-being (13% parental, 11% general). Socio-demographic factors (family size and employment) were associated with maternal well-being.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Partnership

Leadership

Expressions of Love

Encouraging Independence

Adherence to Rules

Focus on Early Childhood

Links to Parental Well-Being

General and Parental Well-Being

Parental Behavior and Parental Well-Being

Research Aims

- (1)

- To describe and compare the daily parenting behaviors of mothers and fathers as defined by the PPM and assess their parental and general well-being.

- (2)

- To explore the relationship between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors and their respective levels of parental and general well-being, controlling for demographic factors (parents’ education, parents’ age, number of weekly working hours, and number of children in the family).

- (3)

- To examine the associations between mothers’ parenting behaviors and fathers’ parental and general well-being, and vice versa, between fathers’ parenting behaviors and mothers’ parental and general well-being.

Parenting Behaviors of Mothers and Fathers

- Both mothers and fathers will exhibit more Love and Partnership behaviors com- pared to Rules and Independence behaviors.

- Positive correlations will be observed among the five PPM constructs, indicating that parents who demonstrate a high level of parental behavior in one construct are likely to show high levels of behavior in the other.

- Within families, positive correlations will be found between the parenting behavior of fathers and mothers.

- Parents’ well-being

- Fathers will report higher levels of general and parental well-being than mothers. Parental daily behaviors and well-being:

- Mothers’ and fathers’ beneficial parenting behavior will positively correlate with their general well-being, even while controlling for demographic factors.

- Fathers’ beneficial parenting behavior, according to the PPM, will positively predict mothers’ general well-being, and vice versa, beyond demographic factors

2. Materials and Methods Participants

Measurements

Procedure

Data Analysis

3. Results

Descriptive Statistics

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||

| Range | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | t-test | r | |

| The PPM1 | ||||||

| Partnership | 1.43-5.79 | 4.48 (0.83) | 3.23-5.86 | 4.58 (0.66) | -1.43 | .65*** |

| Leadership | 3.11-5.67 | 4.54 (0.55) | 3.22-5.78 | 4.52 (0.51) | 0.36 | .54*** |

| Love | 2.82-5.88 | 4.86 (0.57) | 3.06-5.71 | 4.70 (0.57) | 2.38** | .44*** |

| Independence | 3.36-5.55 | 4.28 (0.48) | 2.45-5.27 | 4.23 (0.53) | 0.80 | .27** |

| Rules | 2.43-5.50 | 4.27 (0.60) | 3.36-5.64 | 4.30 (0.52) | -0.29 | .49*** |

| Parental well-being | ||||||

| Positive feelings | 2.90-6.00 | 4.92 (0.79) | 3.00-6.00 | 4.88 (0.70) | 0.38 | .41*** |

| Negative feelings | 1.00-5.09 | 2.74 (0.82) | 1.00-4.45 | 2.51 (0.71) | 2.32* | .31** |

| General well-being1,2 | ||||||

| Positive feelings | 2.36-5.91 | 4.15 (0.83) | 2.36-5.55 | 4.24 (0.68) | -0.80 | .38** |

| Negative feelings | 1.33-4.80 | 2.82 (0.76) | 1.50-3.89 | 2.48 (0.61) | 3.07** | .21 |

- Figure 1. Description of parents’ report of their implementation of the five PPM constructs.

Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parental and General Well-Being

Associations Between Parenting Behaviors (PPM) and Parents’ Parental and General Well-Being: Relations within Gender

| Mothers (n = 85) | Fathers (n = 85) | ||||||||

|

Parental well-being (β) |

General well-being (β) |

Parental well-being (β) |

Parental well-being (β) |

||||||

| Step 1 | |||||||||

| No. of children | -.22^ | .09 | -.12 | -.14 | |||||

| M. Working hours | .22^ | .22 | .21 | .01 | |||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||

| No. of children | -.21* | .09 | -.11 | -.13 | |||||

| M. Working hours | .07 | .07 | .09 | -.07 | |||||

| Parenting (PPM) | .71*** | .68*** | .61*** | .49*** | |||||

| R2 | ΔR2 | R2 | ΔR2 | R2 | ΔR2 | ||||

| Step 1 | |||||||||

| Background measures | .10* | .05 | .06 | .02 | |||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||

| Parenting (PPM) | .58 | .48** | .49 | .44*** | .41 | .35*** | .25 | .23*** | |

The Relationship Between Parenting Behaviors (PPM) and Parents’ Parental and General Well-Being Beyond the Family Background Measures: Relations Across Genders

|

4. Discussion

Parenting Behaviors and Gender Differences

Parents’ Well-Being (General and Parental) and Its Predictors

Cross-Gender Influences

Practical Implications

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

References

- Demick, J. (2019). Stages of parental development. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Volume 3 Being and becoming a parent (pp. 556–595). Third edition. Routledge.

- Ferguson, E. D., Hagaman, J., Grice, J. W., & Peng, K. (2006). From leadership to parenthood: The applicability of leadership styles to parenting styles. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 10(1), 43–55. [CrossRef]

- Grych, J. (2012). Marital relationships and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Volume 4 social conditions and applied parenting. Psychology Press.

- Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & John, R. S. (2001). Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families.Journal of Family Psychology, 15(1), 3–21. [CrossRef]

- Chung, K. S., & Kim, M. (2017). Anger factors impacting on life satisfaction of mothers with young children in Korea: Does mother’s age matter? Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 190–194. [CrossRef]

- Imafuku, M., Saito, A., Hosokawa, K., Okanoya, K., & Hosoda, C. (2021). Importance of maternal persistence in young children’s persistence. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 726583. [CrossRef]

- Aram, D., Asaf, M., Karabanov, G. M., Ziv, M., Sonnenschein, S., Stites, M., & López-Escribano, C. (2022). Beneficial parenting according to the “Parenting Pentagon Model”: A cross-cultural study during a pandemic. In The impact of COVID-19 on early childhood education and care: International perspectives, challenges, and responses (pp. 215–236). Springer International Publishing.Newland, L. Family well-being, parenting, and child well-being: Pathways to healthy adjustment. Clinical Psychologist 2015, 19, 3–14.

- Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being?Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 846–895. [CrossRef]

- Faircloth, C., & Murray, M. (2015). Parenting: Kinship, Expertise, and Anxiety. Journal of Family Issues, 36(9), 1115-1129. [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, E. A., & Stifter, C. A. (2010). Predicting preschool effortful control from toddler temperament and parenting behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31(3), 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Gorman-Smith, D., Tolan, P. H., Henry, D. B., & Florsheim, P. (2000). Patterns of family functioning and adolescent outcomes among urban African American and Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(3), 436–457. [CrossRef]

- Mandara, J., Murray, C. B., Telesford, J. M., Varner, F. A., & Richman, S. B. (2012). Observed gender differences in African American mother-child relationships and child behavior. Family Relations, 61(1), 129–141. [CrossRef]

- Alon, R., Bergman Deitcher, D., & Aram, D. (2025). The roles of parental identity and behaviors in Ultra-Orthodox Israelis’ parental well-being. Journal of Child and Family Studies. [CrossRef]

- Meoded Karabanov, G., Asaf, M., Ziv, M., & Aram, D. (2021). Parental behaviors and involvement in children’s digital activities among Israeli Jewish and Arab families during the COVID-19 lockdown. Early Education and Development, 32(11), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Karreman, A., van Tuijl, C., van Aken, M. A., & Deković, M. (2008). Parenting, coparenting, and effortful control in preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 30-40. [CrossRef]

- Newland, L. I., Coyl, D. D., & Freeman, H. (2008). Predicting preschoolers’ attachment security from fathers’ involvement, internal working models, and use of social support. Early Child Development and Care, 178(7–8), 785–801. [CrossRef]

- Ashton-James, C. E., Kushlev, K., & Dunn, E. W. (2013). Parents reap what they sow: Child-centrism and parental well-being. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(6), 635–642. [CrossRef]

- Bellon, E. O., Ngware, M. W., & Admassu, K. (2017). The Role of Parental Leadership in Academic Performance: A Case of Pupils in the Free Primary Education Program in Kenya. Education and Urban Society, 49(1), 110-130. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S., Assor, A., & Liu, X. (2015). Perception of parents as demonstrating the inherent merit of their values: Relations with self-congruence and subjective well-being. International Journal of Psychology, 50(1), 70–74. [CrossRef]

- Yuliani, F., Awalya, A., & Suminar, T. (2019). Influences of parenting style on independence and confidence characteristics of pre-school children. Journal of Primary Education, 8(7), 83–87. https://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/jpe/article/view/34279.

- Perra, O., Paine, A. L., & Hay, D. F. (2021). Continuity and change in anger and aggressiveness from infancy to childhood: The protective effects of positive parenting. Development and Psychopathology, 33(3), 937–956. [CrossRef]

- Shin, E., Smith, C. L., Devine, D., Day, K. L., & Dunsmore, J. C. (2023). Predicting preschool children’s self-regulation from positive emotion: The moderating role of parental positive emotion socialization. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 62, 53–63. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S. M. (2023). Let me choose: The role of choice in the development of executive function skills. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 32(3), 220–227. [CrossRef]

- Guay, F., Ratelle, C. F., Duchesne, S., & Dubois, P. (2018). Mothers’ and fathers’ autonomy-supportive and controlling behaviors: An analysis of interparental contributions. Parenting, 18(1), 45–65. [CrossRef]

- Laurin, J. C., & Joussemet, M. (2017). Parental autonomy-supportive practices and toddlers’ rule internalization: A prospective observational study. Motivation and Emotion, 41, 562-575. [CrossRef]

- LeCuyer, E. A. (2014). African American and European American mothers’ limit-setting with their 36-month-old children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 275-284. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C., Zeinstra, G. G., Forde, C. G., & Jager, G. (2024). Sweet rules: Parental restriction linked to lower free sugar and higher fruit intake in 4–7-year-old children. Food Quality and Preference, 113, 105071. [CrossRef]

- Roskam, I., Stievenart, M., Meunier, J. C., & Noël, M. P. (2014). The development of children’s inhibition: Does parenting matter? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 122, 166–182. [CrossRef]

- Montesino, S. V., Martín, M. C. M., & Canales, I. S. (2021). Parenting practices of Spanish families during the coronavirus lockdown period. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 19(54), 325–350.

- Herbst, C.M.; Ifcher, J. The increasing happiness of US parents. Review of Economics of the Household 2016, 14, 529–551.

- Nomaguchi, K.; Milkie, M.A. Parenthood and well-being: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family 2020, 82, 198–223.

- Sirois, F.M.; Bögels, S.; Emerson, L.M. Self-compassion improves parental well-being in response to challenging parenting events. The Journal of Psychology 2019, 153, 327–341.

- Luhmann, M.; Hawkley, L.C.; Eid, M.; Cacioppo, J.T. Time frames and the distinction between affective and cognitive well-being. Journal of Research in Personality 2012, 46, 431–441.

- Mckeown, K.; Pratschke, J.; Haase, T. Family well-being: What makes a difference? Study based on a representative sample of parents and children in Ireland. The Céifin Centre 2003.

- Pirralha, A.; Dobewall, H. Does becoming a parent change the meaning of happiness and life satisfaction? Evidence from the European Social Survey. Proceedings of the 48th Scientific Meeting of the Italian Statistical Society SIS2016 Proceedings 2016.

- Buecker, S.; Luhmann, M.; Haehner, P.; Bühler, J.L.; Dapp, L.C.; Luciano, E.C.; Orth, U. The development of subjective well-being across the life span: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin 2023, 149, 418–446.

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin 1999, 125, 276–302.

- Mathentamo, Q.; Lawana, N.; Hlafa, B. Interrelationship between subjective wellbeing and health. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2213–2213.

- Suldo, S.M.; Shaffer, E.J. Looking Beyond Psychopathology: The Dual-Factor Model of Mental Health in Youth. School Psychology Review 2008, 37, 52–68.

- Musick, K.; Meier, A.; Flood, S. How parents fare: Mothers’ and fathers’ subjective well-being in time with children. American Sociological Review 2016, 81, 1069–1095.

- Voydanoff, P.; Donnelly, B.W. Parents’ risk and protective factors as predictors of parental well-being and behavior. Journal of Marriage and the Family 1998, 60, 344–355.

- Aassve, A.; Goisis, A.; Sironi, M. Happiness and Childbearing Across Europe. Social Indicators Research 2012, 108, 65–86.

- Ballas, D.; Dorling, D. Measuring the impact of major life events upon happiness. International Journal of Epidemiology 2007, 36, 1244–1252.

- Impett, E.A.; English, T.; John, O.P. Women’s emotions during interactions with their grown children in later adulthood: The moderating role of attachment avoidance. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2011, 2, 42–50.

- Bandura, A.; Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Regalia, C.; Scabini, E. Impact of family efficacy beliefs on quality of family functioning and satisfaction with family life. Applied Psychology 2011, 60, 421–448.

- Offer, S. Time with children and employed parents’ emotional well-being. Social Science Research 2014, 47, 192–203.

- Silverberg, S.B.; Steinberg, L. Adolescent autonomy, parent-adolescent conflict, and parental well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 1987, 16, 293–312.

- Fiese, B.H.; Wamboldt, F.S.; Anbar, R.D. Family asthma management routines: Connections to medical adherence and quality of life. The Journal of Pediatrics 2005, 146, 171–176.

- Edlund, J.; Öun, I. Equal sharing or not at all caring? Ideals about fathers’ family involvement and the prevalence of the second half of the gender revolution in 27 societies. Journal of Family Studies 2023, 29, 2576–2599.

- Lee, Y. Undoing gender’ or selection effects?: fathers’ uptake of leave and involvement in housework and childcare in South Korea. Journal of Family Studies 2023, 29, 2430–2458.

- Craig, L.; Mullan, K. How Mothers and Fathers Share Childcare: A Cross-National Time-Use Comparison. American Sociological Review 2011, 76, 834–861.

- Sayer, L.C.; Gornick, J.C. Cross-national variation in the influence of employment hours on child care time. European Sociological Review 2011, 28, 421–442.

- Rinaldi, C.M.; Howe, N., 2012.

- Giallo, R.; Rose, N.; Vittorino, R. Fatigue, wellbeing and parenting in mothers of infants and toddlers with sleep problems. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 2011, 29, 236–249.

- Orchard, E.R.; Ward, P.G.; Egan, G.F.; Jamadar, S.D. Evidence of subjective, but not objective, cognitive deficit in new mothers at 1-year postpartum. Journal of Women’s Health 2022, 31, 1087–1096.

- Mcmahon, C.A.; Boivin, J.; Gibson, F.L.; Hammarberg, K.; Wynter, K.; Fisher, J.R. Older maternal age and major depressive episodes in the first two years after birth: Findings from the Parental Age and Transition to Parenthood Australia (PATPA) study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2015, 175, 454–462.

- Stutzer, A.; Frey, B.S. Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? The Journal of Socio-Economics 2006, 35, 326–347.

- Pollmann-Schult, M. Parenthood and life satisfaction: Why don’t children make people happy? Journal of Marriage and Family 2014, 76, 319–336.

- Augustine, J.M.; Negraia, D.V. Exploring education differences in the parental well-being gap. Sociological Inquiry 2024, 94, 66–87.

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review 2006, 31, 72–92.

- Wayne, J.H.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Work-family facilitation: A theoretical explanation and model of primary antecedents and consequences. Human Resource Management Review 2007, 17, 63–76.

- Paulin, M.; Lachance-Grzela, M.; Mcgee, S. Bringing work home or bringing family to work: Personal and relational consequences for working parents. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 2017, 38, 463–476.

- Veit, C.T.; Ware, J.E. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1983, 51, 730–742.

- Florian, V.; Drori, Y. Mental Health Inventory (MHI): Psychometric characteristics and normative data regarding the Israeli population. Psychology 1990, pp. 26–35.

- Deater-Deckard, K.; Lansford, J.E.; Malone, P.S.; Alampay, L.P.; Sorbring, E.; Bacchini, D.; Bombi, A.S.; Bornstein, M.H.; Chang, L.; Giunta, L.D.; et al. The association between parental warmth and control in thirteen cultural groups. Journal of Family Psychology 2011, 25, 790–794.

- Lin, X.; Xie, S.; Li, H. Chinese mothers’ and fathers’ involvement in toddler play activity: Type variations and gender differences. Early Child Development and Care 2018, 189, 179–190.

- Milkie, M.A.; Bianchi, S.M.; Mattingly, M.J.; Robinson, J.P. Gendered division of childrearing: Ideals, realities, and the relationship to parental well-being. Sex Roles 2002, 47, 21–38.

- Rajhans, P.; Goin-Kochel, R.P.; Strathearn, L.; Kim, S. It takes two! Exploring sex differences in parenting neurobiology and behaviour. Journal of neuroendocrinology 2019, 31.

- Lewis, C.; Lamb, M.E. Fathers’ influences on children’s development: The evidence from two-parent families. European journal of psychology of education 2003, 18, 211–228.

- Gervais, C.; Lavoie, K.; Garneau, J.; Dubeau, D. Conceptions and experiences of paternal involvement among Quebec fathers: A dual parental experience. Journal of Family Issues 2020, 41, 2329–2351.

- Hodkinson, P.; Brooks, R. Interchangeable parents? The roles and identities of primary and equal carer fathers of young children. Current Sociology 2020, 68, 780–797.

- Sotzker-Cohen, R. 15 notes on Israeli parenting. Panim: A Journal for Culture, Society and Education 2002, 19, 112–117.

- Dwairy, M.; Achoui, M. Introduction to three cross-regional research studies on parenting styles, individuation, and mental health in Arab societies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2006, 37, 221–229.

- Chen, P.; Aram, D.; Tannenbaum, M. Forums for parents of young children: Parents’ online conversations in Israel and France. International Journal About Parents in Education 2014, 8, 11–25.

- Repetti, R.L.; Reynolds, B.M.; Sears, M.S. Families under the microscope: Repeated sampling of perceptions, experiences, biology, and behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family 2015, 77, 126–146.

- Schofield, T.J.; Conger, R.D.; Martin, M.J.; Stockdale, G.D.; Conger, K.J.; Widaman, K.F. Reciprocity in parenting of adolescents within the context of marital negativity. Developmental Psychology 2009, 45, 1708–1722.

- Steenhoff, T.; Tharner, A.; Væver, M.S. Mothers’ and fathers’ observed interaction with preschoolers: Similarities and differences in parenting behavior in a well-resourced sample. Article e0221661 2019, 14.

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.D.; Neve, D.; 2024.

- Skreden, M.; Skari, H.; Malt, U.F.; Pripp, A.H.; Björk, M.D.; Faugli, A.; Emblem, R. Parenting stress and emotional well-being in mothers and fathers of preschool children. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2012, 40, 596–604.

- Nelson-Coffey, S.K.; Killingsworth, M.; Layous, K.; Cole, S.W.; Lyubomirsky, S. Parenthood is associated with greater well-being for fathers than mothers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2019, 45, 1378–1390.

- Bird, L.; Sacker, A.; Mcmunn, A. Relationship satisfaction and concordance in attitudes to maternal employment in British couples with young children. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2020, 37, 3066–3088.

- Shoshani, A.; Yaari, S. Parental flow and positive emotions: Optimal experiences in parent-child interactions and parents’ well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 2022, 23, 789–811.

- Kouros, C.D.; Papp, L.M.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Cummings, E.M. Spillover between marital quality and parent-child relationship quality: Parental depressive symptoms as moderators. Journal of Family Psychology 2014, 28, 315–325.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).