1. Introduction

Over the past half century exercise physiology research produced a vast and well documented literature concerning the quantification of training effects on a series of anthropometric, muscle skeletal, cardiorespiratory and metabolic parameters in young professional elite as well as in non-elite athletes participating in all kinds of sport competitions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. In more recent years these studies have been extended to a population of “older” athletes, currently known as master athletes, participating in sport events such as running, swimming, cycling, rowing and in many other sport disciplines [

7,

8,

9]. In all cases athletes’ participation in such competitions entails the athlete’s attendance and adherence to specific coach planned and assisted training programs which are normally aimed at optimizing the athlete’s psycho-physical performance during competition season [

10]. However, a recent report of the European Commission (2010) estimates that, only in Europe, 27% of the population over 15 y.o., is involved at least once a week in physical leisure activities of different types without any supervision. This population that comprises a large variety of people for age, gender, health conditions, practice frequency, sport discipline, etc., is not affiliated to any official sport association or institution, nor its physical training follow the conventional guidelines of coach-assisted programs specific to discipline. In relationship to their physical activity this cohort of people can be therefore defined as “self-trained”. Since it is long known that regular physical activity is a main health factor [

11,

12], monitoring in these people the effectiveness of their training, their progress and achievements in relationship to their specific goals is certainly of great importance because it would contribute to boost their physical practice and help to keep them physically active and healthy. The studies carried out on this “self-trained” population have been mostly focused on the determinants concerning the motivations and type of sport or physical activity chosen in relationship to age and gender of participants [

13,

14,

15]. In some cases, they also provide a quantitative characterization of the performed activity, although limited to a series of non-physiological variables self-reported on specific questionnaires [

16]. There is instead a lack of information about the evaluation of the effectiveness of self-trained people consistently participating in leisure physical activities on their main cardiovascular, respiratory and metabolic functions and body composition as well. Recently Storer and coworkers found in amateur athletes trained by certified coaches an improvement in their body composition and aerobic performance in comparison to self-trained individuals participating in gym fitness programs [

17]. To our knowledge, there are no other studies that investigate in comparative terms the effectiveness of a training season between a population of self-trained and coach-assisted athletes practicing the same sport discipline for leisure and competition, respectively. The main problem concerned with this type of investigation is related to the identification of two homogeneous and therefore comparable sets of participants as for lifestyle, main anthropometric characteristics, health conditions, diet, physical activity history, actual fitness, sport discipline and training workloads. Only in this case in fact the actual efficacy of the considered variables of coaching versus self-training, being this the main difference, could be evaluated in quantitative terms.

Aims of the present study were in fact to quantify the effectiveness either on the stress test performance, as well as on a series of anthropometric, cardiorespiratory and metabolic parameters of a training macrocycle in a cohort of self-trained people practicing swimming for leisure (leisure swimmers: LS) with the only aim to keep a good level of physical fitness, and a cohort of coach trained master swimmers (MS) practicing the same discipline as in preparation for the competitions season. A second goal was to compare before and after the training season in the two populations all the monitored variables. We have chosen to carry out the study on swimmers, because leisure swimming is in Italy among the most popular and practiced sport during the fall and throughout the winter and spring seasons. Furthermore, MS competitions have also become very popular and increasingly attract considerable numbers of master athletes [

18]. Finally was the circumstance that it was possible to identify in the same swimming facility two comparable cohorts of LS and MS who gave their consent to participate to the study.

2. Materials and Methods

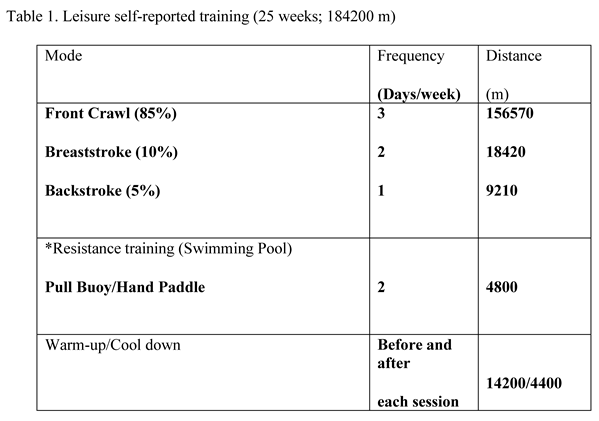

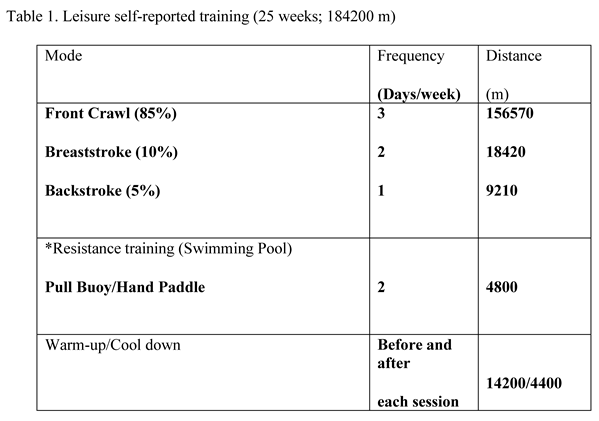

Twenty (n = 20) healthy and physical active male volunteers divided into MS (n = 10) and LS (n = 10), after written and informed consent, were enrolled for the study. All the participants were no smokers, unaware of the main purpose of the study and had no history of any major respiratory, metabolic and cardiovascular disease. They furthermore were not taking any medication or vitamin supplementation or showed health problems at the time of their physical examination. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving individuals were approved by the ethical committee of A.O.U.CA (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Cagliari, approval code: prot. PG/2021/16466, approval date 27 October 2021). Further specific criteria for the recruitment were: age ranging between 40 to 60 y. o., a history of active participation to sport competitions in younger age and in the last three years regularly practicing swimming three times a week starting early in the fall and enduring until late spring. MS followed the specific training protocols administered by a certified swimming coach and participated in competitions. LS followed their self-administered protocols without the specific aim of participating in any competitions (Table 1).

Both groups were only involved in swimming practice and were not performing any other type of physical or sport activities, their training volume (m/week) being similar in both groups. MS and LS were evaluated by taking a series of anthropometrical and metabolic measurements, before starting their training, i.e., late September, early October (T0) and re-evaluated after six months, i.e., late March early April (T6). Before the beginning of the training season, all the LS and MS participants, randomly matched in sets of four at time, were submitted to a series of medical tests to evaluate the level of their physical fitness. A body composition analysis was performed using the multi-frequency impedance analysis technique (MBIA; InBody 3.0 Biospace), after which the athletes were submitted to an incremental treadmill running test to volitional exhaustion while monitoring the ECG (Custo med GmbH, Runner Galaxy, M.T.C, Italy). After 3 min at rest in standing position on the treadmill to record resting data, the subject started to run at 5 km h

-1 and then continued with an incremental speed of 1 km·h

-1/min, until exhaustion. The treadmill gradient was maintained at 1% throughout the test to reflect the energy cost of outdoor running [

19]. After six months training, both groups were re-evaluated and among other parameters the total duration of their performance (total time, TT/s), the maximum speed (Spmax, m·s

-1) and the speed at anaerobic threshold (SpAT) reached by the participants in the test at this time (T6) were evaluated and compared to their respective T0 values. Treadmill running test was chosen since other authors reported that swimmers have on average, comparable VO

2max consumption in swimming tests performed in the pool and treadmill running tests carried out in a laboratory set up [

20]. Throughout the test the athletes’ respiratory parameters were monitored by a portable metabolic system (MedGraphics VO2000, St. Paul, Minneapolis, USA) which, through telemetric transmission, relayed averaged data of 3 consecutive breaths to a specific software. The measurements provided by this device have been reported to be precise, reliable and to comply with others standard metabolic devices for laboratory use [

21]. Prior to testing, the VO

2000 was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then the following parameters were collected during the test: oxygen uptake (VO

2), carbon dioxide production (VCO

2) and minute ventilation (VE). Achievement of maximal oxygen uptake (VO

2max) was considered when at least two of the following criteria were fulfilled: 1) a plateau in VO

2, despite increasing speed; 2) a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) > 1.10; and 3) a heart rate ± 10 beats·min

-1 of predicted maximum heart rate (HR) calculated as 220-age [

22]. The ventilatory equivalent method [

23] was used to determine the anaerobic threshold (AT). Briefly, AT was assessed as an increase in ventilatory equivalent for oxygen, [i.e., pulmonary ventilation (VE) and oxygen consumption (VO

2) ratio, (VE/VO

2)] without associated increase in the ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide [i.e., pulmonary ventilation (VE) and carbon dioxide output (VCO

2) ratio, (VE/VCO

2)], VO

2 at AT was also assessed (VO

2AT). An index of anaerobic glycolysis was obtained by measuring excess CO

2 production (CO

2 excess). This parameter was assessed as follows: CO

2 excess = VCO

2 _ (RERrest·VO

2), where RERrest is the respiratory exchange ratio at rest [

24]. The rationale behind the use of CO

2 excess as an index of lactate accumulation being that at pH tissue, lactic acid dissociates and produces H+ which is buffered by

–HCO

3 and other cell buffers. The amount being buffered by

–HCO

3 leads to H

2CO

3 increase which in turn dissociates in H

2O and CO

2 [

25,

26]. To establish the calorie intake of participants, each participant was asked to fill, in the week preceding T0 and T6 tests, a semi-quantitative questionnaire [

27] which had the instructions included and consisted of 16 printed forms and 16 pages with colored photos of the most common foods and courses of the standard Italian diet (Table 2).

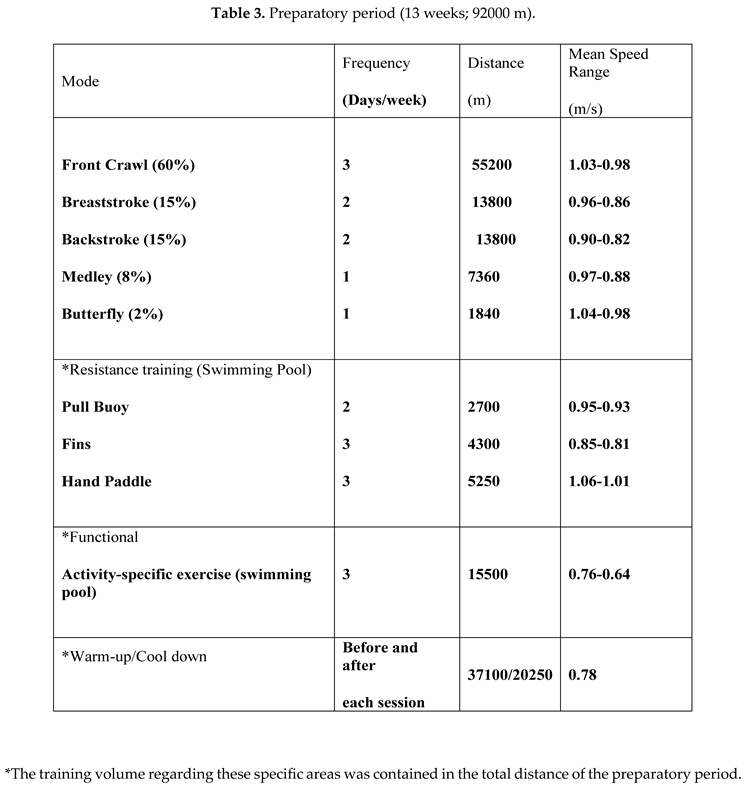

For M.S a periodization training was developed by a certified swimming coach with the purpose of achieving their maximal physical fitness at the time of the main competitions. A block periodization protocol was used for planning the training program [

28]. It consisted of a single macrocycle that included three subsequent mesocycles, each one aimed at the improvement of a specific task. The first cycle consisted of a preparatory period that lasted 13 weeks and 92,000 meters in training volume and was characterized by a high variety of training sessions performed at low intensity. It aimed at the increase of the athletes’ aerobic power and their technical abilities (Table 3).

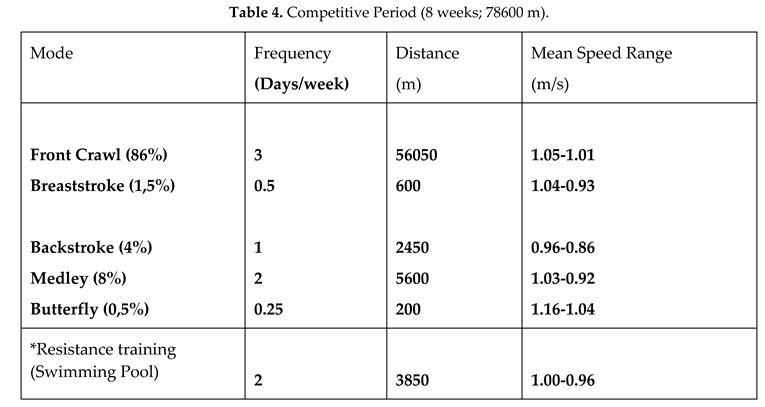

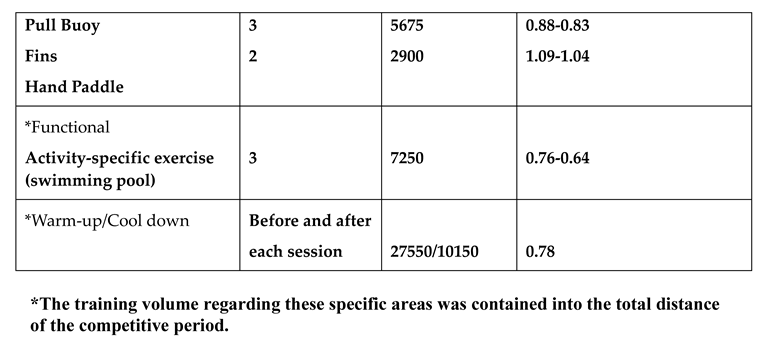

The second period, competitive, lasted 8 weeks and characterized by 78,600 meters in training volume, was aimed at increasing intensity in event specific exercise (free style, strength resistance), Table 4.

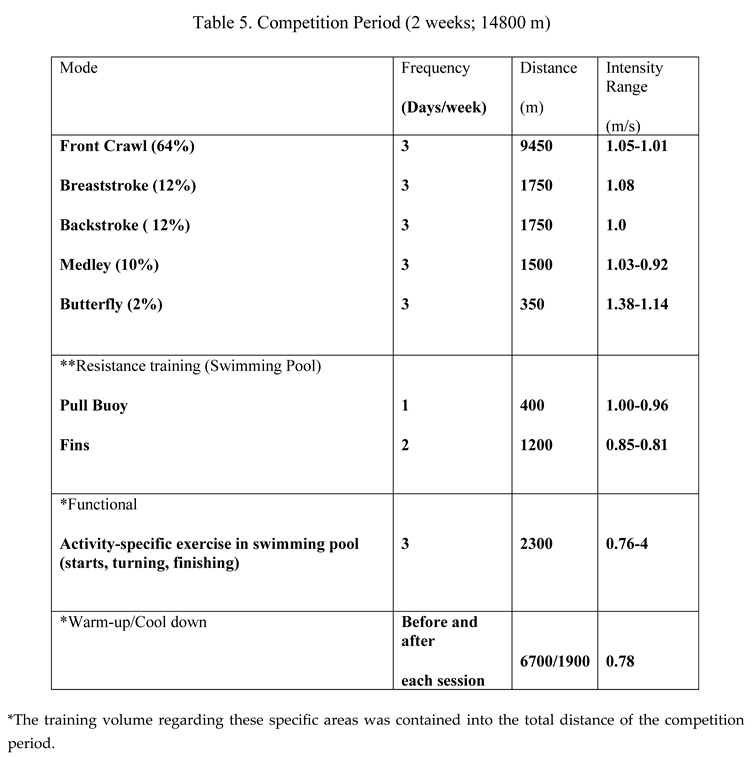

The last period, precompetitive training, lasted 2 weeks and characterized by 14,800 meters in volume, consisted of high intensity sessions orientated to the forthcoming competitions. For the MS the program adherence was weekly checked by their coach. LS carried out an unplanned swimming program of the same duration and volume (23 weeks 184, 200 meters) using a method of their own choosing, self-reporting on a planner their weekly training during the season (Table 5).

*The training volume regarding these specific areas was contained in the total distance of the preparatory period.

*The training volume regarding these specific areas was contained into the total distance of the competition period.

Statistics were produced utilizing the commercially available software Graph-Pad, Prism. The normality assumption was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The α level was set at p < 0.05. Inter-group time related differences (mean ± SD) were shown as delta values between T0 and T6 and assessed by means of unpaired t-test. The α level was set at p < 0.05 in all cases.

3. Results

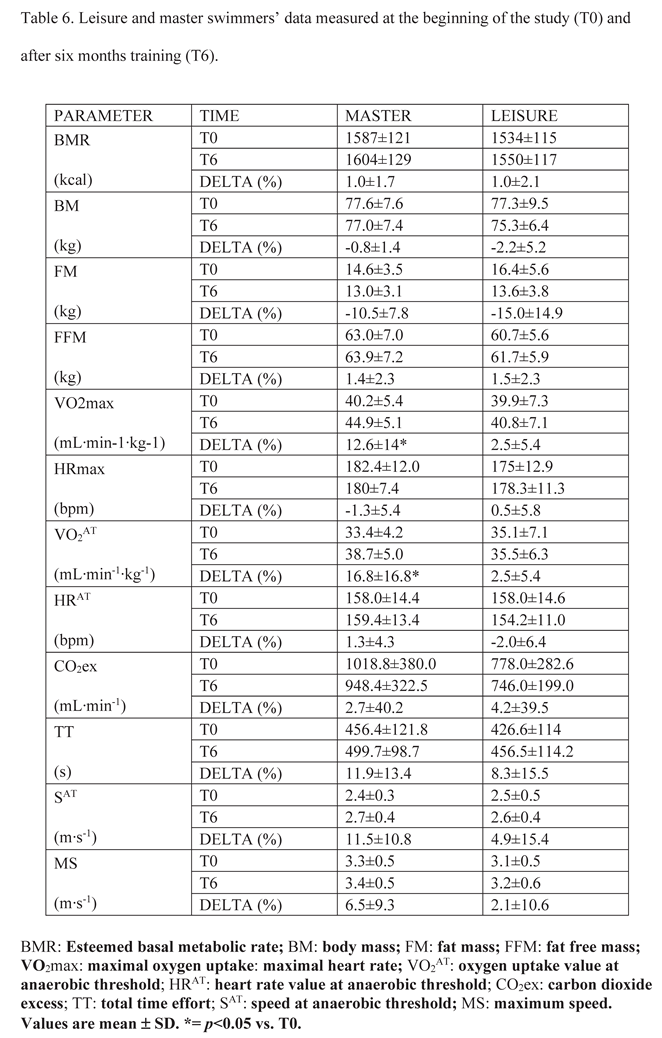

Table 6 reports the overall data collected at T0 and T6 for both master and leisure swimmers along with the statistical significance within each group and between groups.

At the time of the enrolment (T0) both MS and LS had a comparable esteemed basal metabolic rate (BMR), mean body masses (BM) and weekly total calories intake (kcal/w). Table 6. Leisure and master swimmers’ data measured at the beginning of the study (T0) and after six months training (T6).

Body composition analysis at T6 showed in both groups a significant reduction of their respective BM (MS = -0.8 ± 1.4%; LS = -2.2 ± 5.2%; p> 0.05) and FM (MS= -10.5±7.8% and LS= -15.0 ± 14.9%; p>0.05) with a slight, although not significant, FFM and BMR increase. Intergroup statistical analysis did not show at T6 any significant variation of these variables between the groups.

With regard to the stress test data collected at T0, both groups performed the test with comparable total time (TT), maximum speed at anaerobic threshold (SpAT) and absolute maximum speed (Spmax), and even in this case TT and Spmax values of MS performance were slightly better than those of LS At the end of the training period (T6) both groups performed the test with a significant increase of their total time (TT; MS= 11.9 ± 13.4%; LS = 8.3 ± 15.5%; p>0.05) and maximum speed reached (Spmax; MS= 6.5 ± 9.3%; LS = 2.1 ± 10.6%; p>0.05), but without any significant difference between the two groups.

The analysis of the maximal aerobic capacity (VO2max) and VO2 at anaerobic threshold (VO2AT) at the time of the entrance test did not show any significant difference between the two groups. Data from the stress test at T6 showed however a dramatic increase of these variables in MS in comparison to LS. Maximal aerobic capacity in MS increased by 12.6 ±14% while in LS 2.5 ± 5.4% (p<0.05). As for VO2 consumption at anaerobic threshold the increase was of 16.8 ± 16.8% for MS and 2.5 ± 5.4% for LS (p< 0.05).

Chronotropic response at the peak of the stress was similar in both groups at T0 and remained substantially unmodified in the control test at T6. A similar trend showed the index of anaerobic capacity (CO2 excess).

4. Discussion

The WHO set the “Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health” with the overall aim of providing specific guidelines on the dose-response relationship relatively to the frequency, duration, intensity, type and total amount of physical activity needed for the prevention of deconditioning processes [

29]. The recommendations set out in this document address the following three age groups: 5–17; 18–64 and 65 years old and above. For adults aged 18–64, physical activity includes leisure time activities such as: walking, dancing, gardening, hiking, swimming as well as other activities performed in the contest of normal daily life. Adults aged 18–64 should do at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week or do at least 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week or an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous-intensity activity. For additional health benefits, adults should increase their moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity up to 300 minutes per week or engage in 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, or an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous-intensity activity.

Both master and leisure swimmers enrolled in our study satisfied these requirements and as a matter of fact both demonstrated to be rather fit in the preliminary tests performed at the time of their enrolment.

Body composition analysis showed that BM, FM, FFM parameters were within the normal range in both groups, although the values were slightly better in MS in comparison to LS. Regarding the stress test ergometer data at T0, the total duration (total time, TT/s) the maximum speed (Spmax, m·s

-1) and the maximum speed at anaerobic threshold (SpAT) were comparable in the two groups. The physical fitness of all participants was also confirmed by the results of the preliminary cardiopulmonary stress test data at T0 which showed that in both groups the specific VO

2max consumption for gender and age fell within the values range between “above average” and “good” for healthy individuals [

30]. The pretest data seem therefore to confirm the hypothesis of a substantially homogeneous set of the enrolled participants to the study.

Comparison between groups at T6 showed a statistically significant improvement of VO2max and VO2 consumption at anaerobic threshold, in MS respect to LS. Moreover, a positive trend in comparison to T0 was more evident, for most of the considered parameters, in MS rather than LS. Considering the equivalent amount of work in terms of total distance covered in MS and LS this different outcome may be due to the specific training periodization followed by MS in comparison to LS. It is reasonable to speculate that a longer training period (possibly 6 more months) would have resulted in more effective, statistically significant, improvements in their aerobic capacity.

However, only the coach-assisted training was able to evoke significant physiological adaptations in parameters related to aerobic capacity such as VO

2max and VO

2AT. Our results partially agree with what was reported in a recent study in which amateur athletes participating in a 12-week gym program planned by certified personal trainers were compared to self-trained individuals practicing self-directed activities [

17]. These authors reported that coach assisted athletes, in comparison to self-trained individuals, significantly improved at the end of their training body compositions, muscle strength and power, as well as VO

2max consumption, while the training, unlike what observed in our study, was unable to affect their anaerobic threshold [

17].

5. Conclusions

A six-month specific coach-assisted training periodization was more effective than self-assisted training to improve aerobic capacity in amateur athletes. Considering the equivalent amount of work in terms of total distance covered in MS and LS, this different outcome may be due to the training periodization followed by MS. Of note, these improvements can be detected by a specific cardiopulmonary treadmill test. Our research highlighted coach-assisted training has been helpful in improving aerobic capacity in recreational swimmers, and it would have been interesting to see whether this improvement can be beneficial in terms of specific swimming performance.

Coach-assisted training could be more effective to achieve well-being and prevention of pathologies linked to sedentary lifestyle. Training successfully is a process that requires specific competence in various sports and cannot be profitably done by oneself.

The main limit of our research was that tests (for practical reasons) took place on treadmill and not on the water environment. It may be useful for future research to evaluate the coach-assisted training adaptations in a swimming pool, testing swimmers in their specific activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: MPG, FT, MAC. Data curation: FT, MPG, VP, GM, GMG, ADG. Formal analysis: FT, VP, GM, MM, CMC. Investigation: FT, MPG, VP, GM, MAC. Methodology: FT, MAC, MPG. Supervision: FT, MPG, MAC, MM, CMC. Writing–original draft: MAC, FT, VP. Writing–review & editing: FT, MAC.

Funding

It has been no financial assistance regarding this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the name of COMITATO ETICO INDIPENDENTE Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Cagliari. The approval code number: ALLEGATO N° 2..27 all VERBALE N..32 and the date of approval 27 Ottobre 2021.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The experiments comply with the current laws of Italian Government. This study was made possible by technical support from the Swim Sassari ASD.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have not a conflict of interest to declare. The authors declare no specific funding for this work.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LS |

leisure swimmers |

| MS |

coach trained master swimmers |

| ECG |

electrocardiogram |

| Spmax |

maximum speed |

| SpAT

|

speed at anaerobic threshold |

| VO2

|

oxygen uptake |

| VCO2

|

carbon dioxide production |

| VE |

minute ventilation |

| VO2max |

maximal oxygen uptake |

| RER |

respiratory exchange ratio |

| HR |

heart rate |

| AT |

anaerobic threshold |

| VE/VO2

|

ventilatory equivalent for oxygen |

| VE/VCO2

|

ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide |

| CO2 excess |

excess of CO2 production |

| RERrest |

respiratory exchange ratio at rest |

| FFQ |

Food Frequency Questionnaire |

| BMR |

basal metabolic rate |

| BM |

body mass |

| kcal/w |

weekly total calories intake |

| FM |

fat mass |

| FFM |

fat free mass |

| HRAT

|

heart rate value at anaerobic threshold |

| TT |

total time effort |

References

- De Luca A, Stefani L, Pedrizzetti G, et al. The effect of exercise training on left ventricular function in young elite athletes. Cardiovasc Ultrasound.

- Baggish AL, Wang F, Weiner RB, et al. Training-specific changes in cardiac structure and function: a prospective and longitudinal assessment of competitive athletes. J Appl Physiol, 1121.

- Coffey VG and Hawley, JA. The molecular bases of training adaptation. Sport Med.

- Legaz Arrese A, Serrano Ostàriz E, Jcasajùs Mallén JA, et al. The changes in running performance and maximal oxygen uptake after long-term training in elite athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness.

- Fitts, RH. Effects of regular exercise training on skeletal muscle contractile function. Am J Phys Med Rehabil.

- Pluim BM, Zwinderman A H, Van der Laarse A, et al. The athlete’s heart: a meta-analysis of cardiac structure and function. Circulation.

- Baker AB and Tang, YQ. Aging performance for masters records in athletics, swimming, rowing, cycling, triathlon, and weightlifting. Exp Aging Res.

- Berger NJ, Rittweger J. Kwiet A, et al. Pulmonary O2 uptake on-kinetics in endurance and sprint-trained master athletes. Int J Sports Med, 1005.

- Trappe, S. Master Athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab, S: Suppl.

- Mageau GA and Vallerand, RJ. The coach-athlete relationship: a motivational model. J Sport Sci.

- Bauman, AE. Updating the evidence that physical activity is good for health. J Sci Med Sport.

- Kesaniemi Y, Danforth E, Jensen M, et al. Dose-responses issues concerning physical activity and health an evidence-based symposium. Med Sci Sports Exerc.

- Downward P and Rasciute, S. Exploring the covariates of sport participation for health: an analysis of males and female in England. J Sport Sci.

- Dawes NP, Vest A and Simpkins S. Youth participation in organized and informal sports activities across childhood and adolescence: exploring the relationship of motivational beliefs, developmental stage and gender. J Youth Adolesc, 1374.

- Brunet J and Sabiston, C. Exploring motivation for physical activity cross the adult life span. Psyicol Sport Exerc.

- Potdevin FJ, Normani C and Pelayo P. Examining self-training procedures in leisure swimming. J Sport Sci Med.

- Storer TW, Dolezal BA, Berenc MN, et al. Effect of Supervised, Periodized Exercise Training vs. Self-Directed Training on Lean Body Mass and Other Fitness Variables in Health Club Members. J Strength Cond Res, 1995.

- ISTAT. La pratica Sportiva in Italia nel 2013. http://www.istat. 4 July 1286.

- Jones A and Doust, JA. 1% treadmill grade most accurately reflects the energetic cost of outdoor running. J Sports Sci.

- Pinna M, Milia R, Roberto S, et al. Assessment of the specificity of cardiopulmonary response during tethered swimming using a new snorkel device. J Physiol Sci.

- Crouter SE, Antczak A, Hudak JR, et al. Accuracy and reliability of the ParvoMedics TrueOne 2400 and MedGraphics VO2000 metabolic systems. Eur J Appl Physiol 2006; 98(2): 139–151.

- Howley ET, Bassett DR and Welch HG. Criteria for maximal oxygen uptake: review and commentary. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 1292.

- Davis JA, Frank MH, Whipp BJ, et al. Anaerobic threshold alterations caused by endurance training in middle-age men. J Appl Physiol, 1039.

- Anderson GS and Rhodes, EC. A review of blood lactate and ventilatory methods of detecting transition thresholds. Sports Med.

- Beaver LL, Wasserman K and Whipp BJ. Bicarbonate buffering of lactic acid generate during exercise. J Appl Physiol.

- Crisafulli A, Pittau GL, Lorrai L, et al. Poor reliability of heart rate monitoring to assess oxygen consumption during field training. Int J Sports Med.

- Fidanza F, Gentile MG and Porrini MA. A self-administered semiquantitative food-frequency questionnaire with optical reading and its concurrent validation. Eur J Epidemiol.

- Issurin, VB. New horizons for the methodology and physiology of training periodization. Sports Med.

- Geneva: World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Free Books & Documents. 2010. [PubMed]

- Schneider, J. Age Dependency of Oxygen Uptake and Related Parameters in Exercise Testing: An Expert Opinion on Reference Values Suitable for Adults. Lung.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).