Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

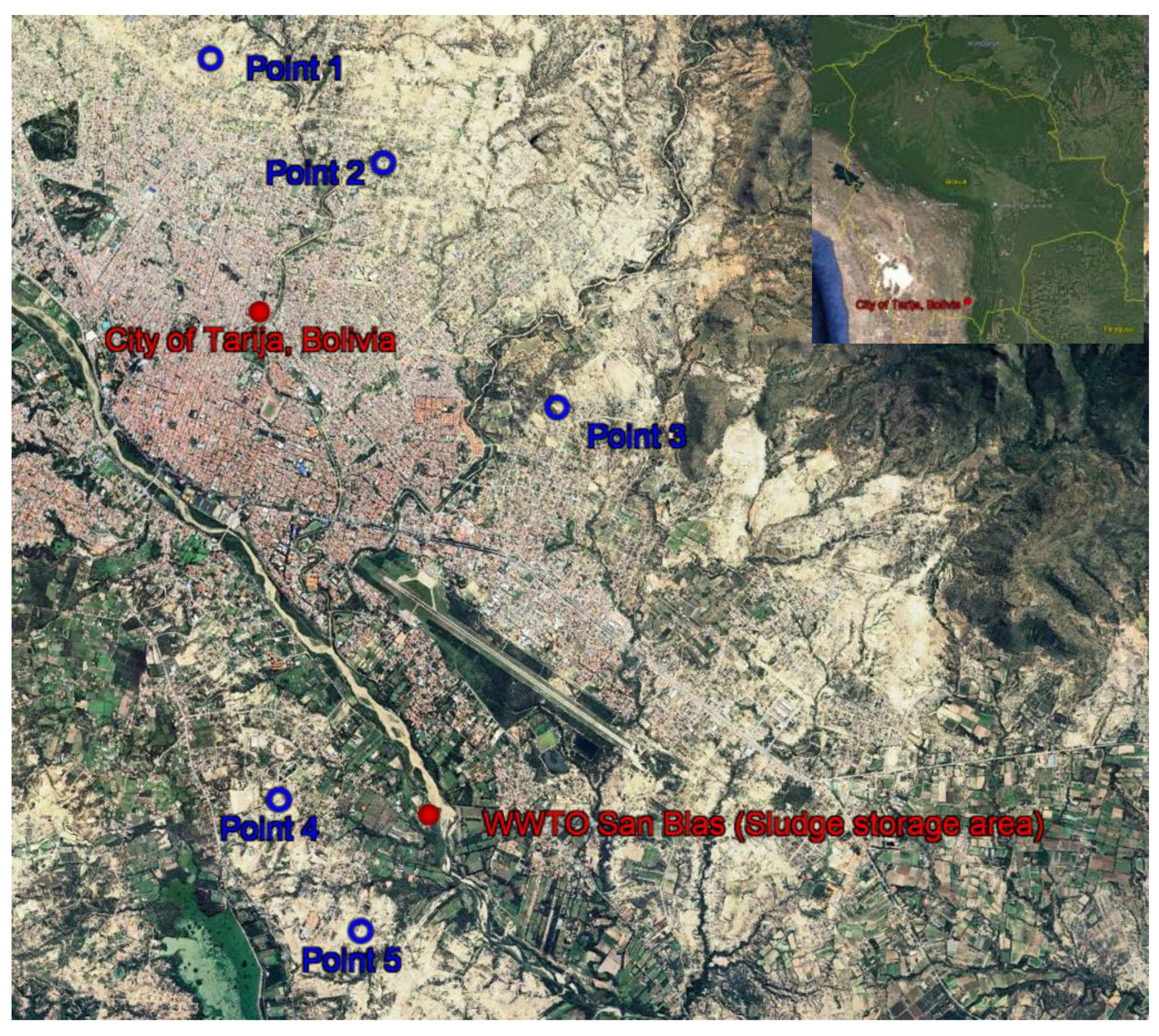

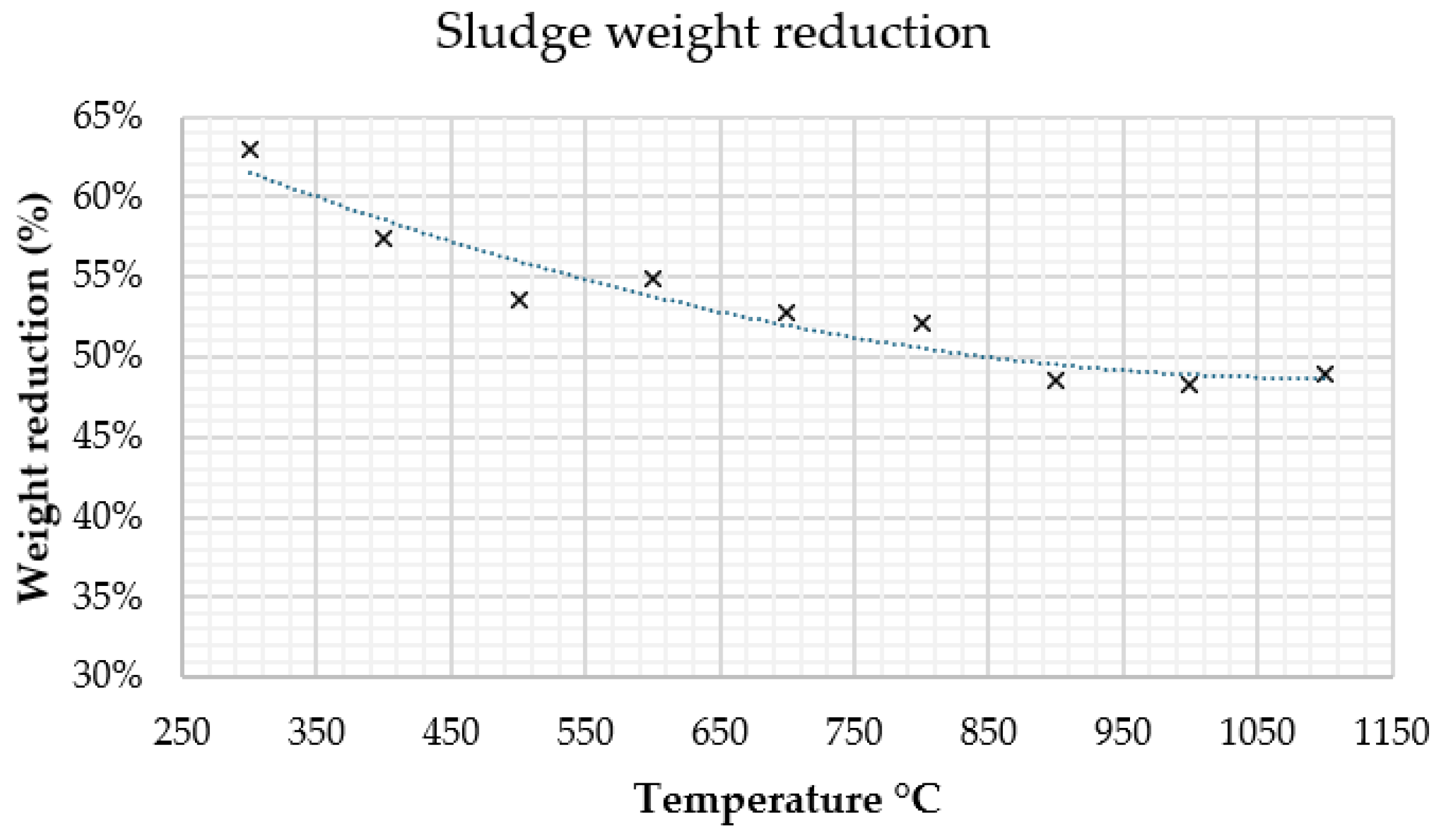

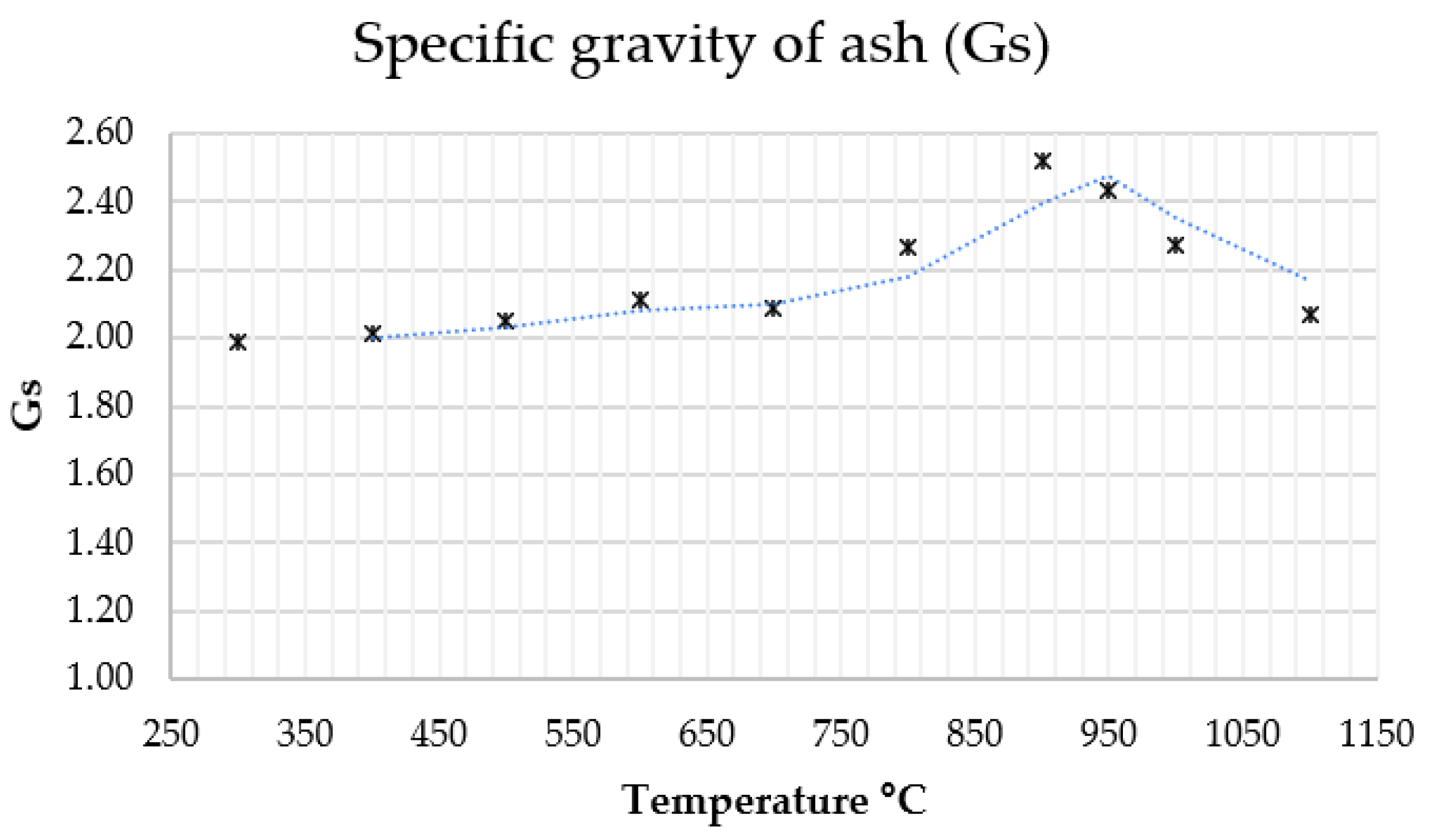

This study presents a sustainable and eco-friendly methodology to enhance the physico-mechanical properties of fine-grained soils through the incorporation of biosolid ashes (BA) derived from the San Blas Wastewater Treatment Plant in Tarija. Currently, this approach provides an alternative for the reuse of more than 3,500 tons of sludge per year, a figure expected to increase significantly with the planned operation of the plant on the left bank of the Río Guadalquivir. The methodology not only improves the mechanical performance of local silt-clay soils but also promotes the valorization of residual sludge, aligning with circular economic principles and reducing the environmental impacts associated with conventional waste disposal. The biosolids were subjected to controlled incineration at 900–1000 °C, generating ashes with a specific gravity of up to 2.52, which were then incorporated into soils at dosages ranging from 5% to 30%. Comprehensive laboratory testing included Atterberg limits, moisture content, specific gravity, modified Proctor tests for maximum and optimum dry density, consolidation, direct shear, and CBR tests on both natural soils and treated mixtures. Results demonstrated reductions in plasticity index of up to 9.5%, substantial increases in shear strength and bearing capacity, and compressibility reductions of up to 45%. CBR strength improved by more than 100% for mixtures containing 30% BA, with optimal performance observed at 10–15% BA content (average specific gravity 2.40). These findings confirm that biosolid ashes are an effective and environmentally responsible additive for geotechnical soil stabilization, offering a sustainable solution that simultaneously addresses construction requirements and promotes ecological waste management in Tarija.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Study Areas

2.2. Residual Sludge

2.3. Laboratory Test

- • Moisture content according to ASTM D2216-90 [69];

- • Specific gravity, ASTM D854 [69];

- • Ability to Work, Liquid Limit, and Plastic Limit according to ASTM D 4318 [69];

- • Modified Proctor compaction tests according to ASTM D 1557-78 [69];

- • Direct shear tests according to ASTM D 3080-90 [69];

- • One-dimensional consolidation (primary) tests according to ASTM D2435 [70].

- • CBR test according to ASTM D 1883-87 [69].

2.4. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Sludge and Ash Assessment

3.2. Results of Soils Combined with Biosolids Ash

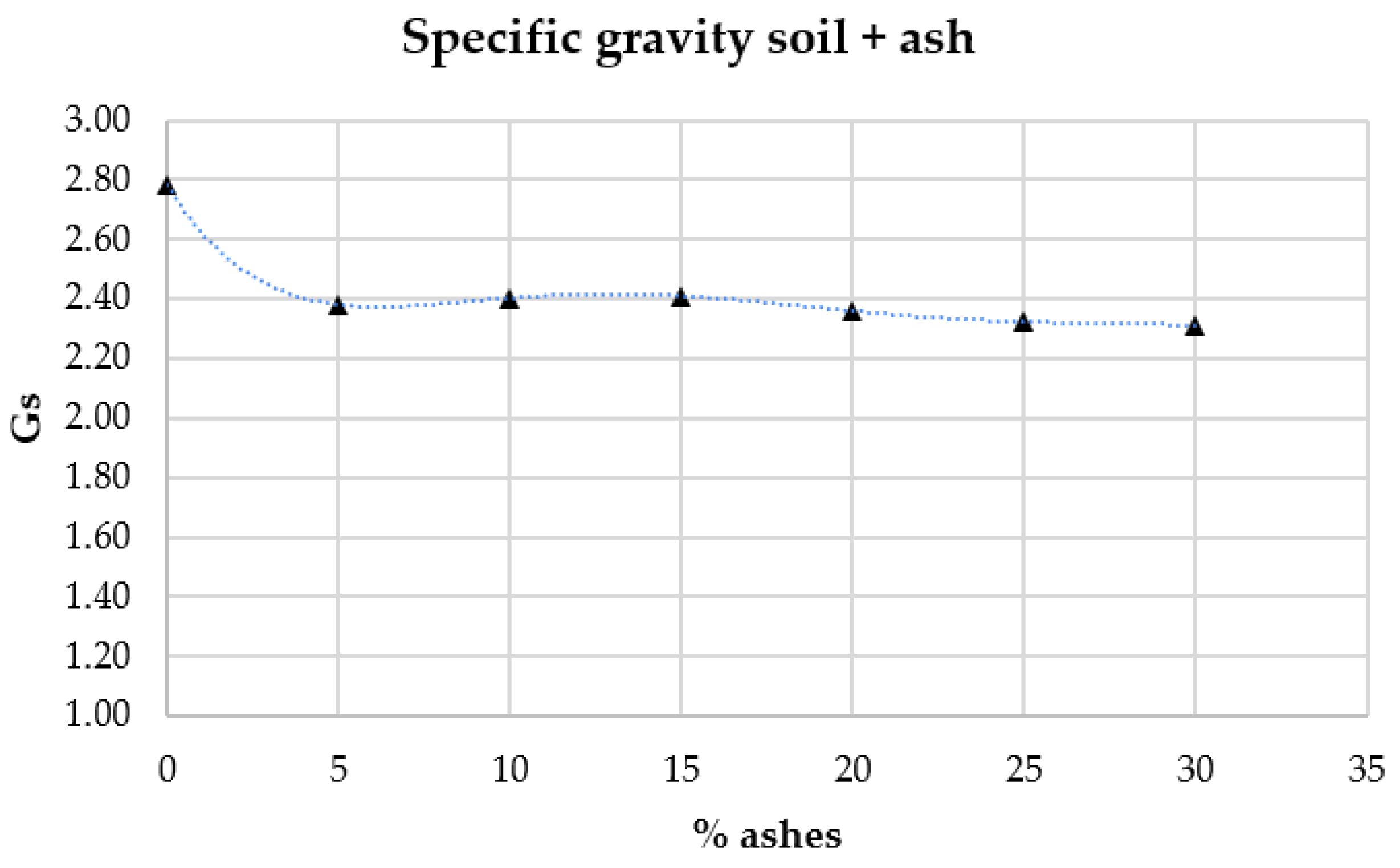

3.2.1. Specific Gravity of Soil and Ash

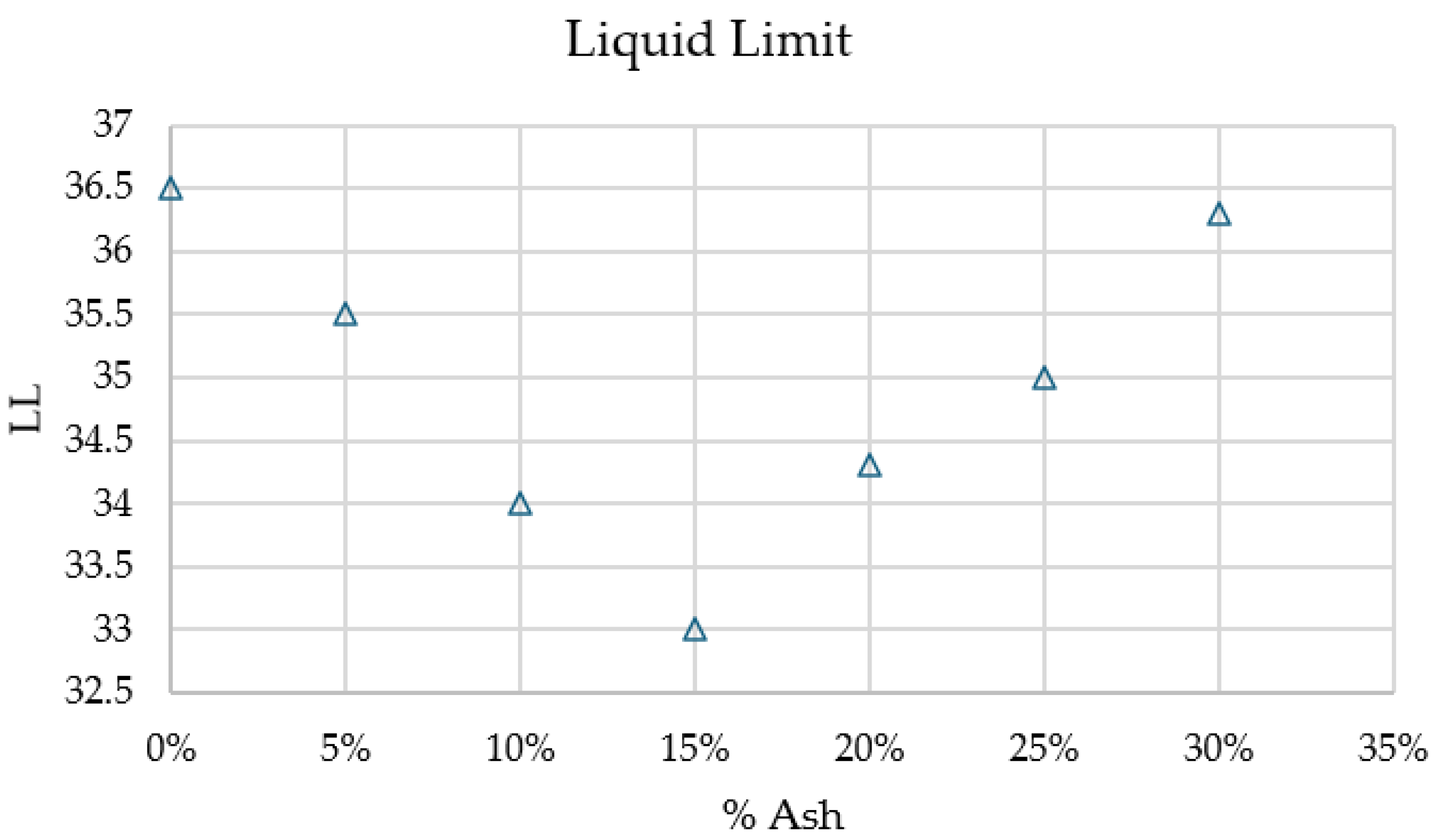

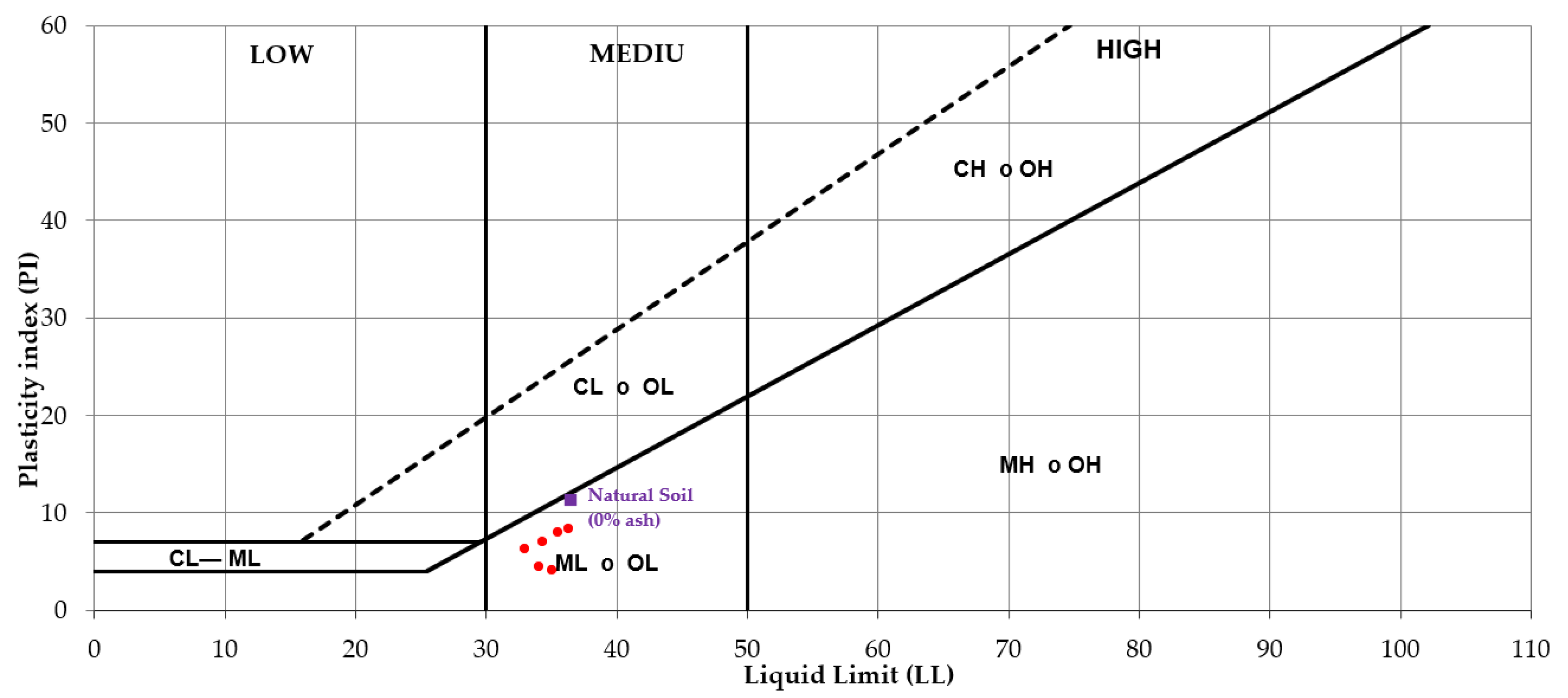

3.2.2. Consistency Limits: Liquid Limit and Plastic Limit

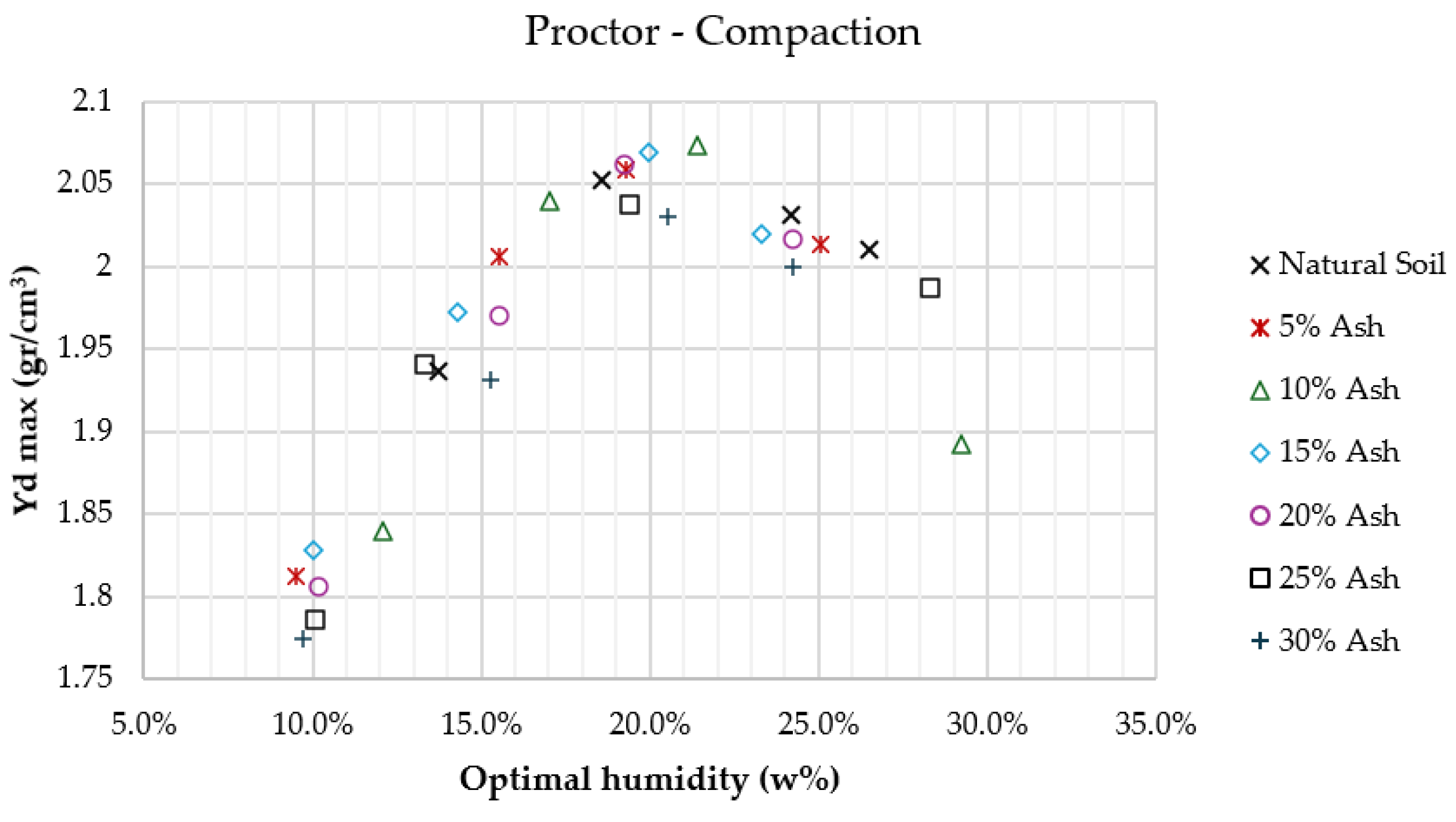

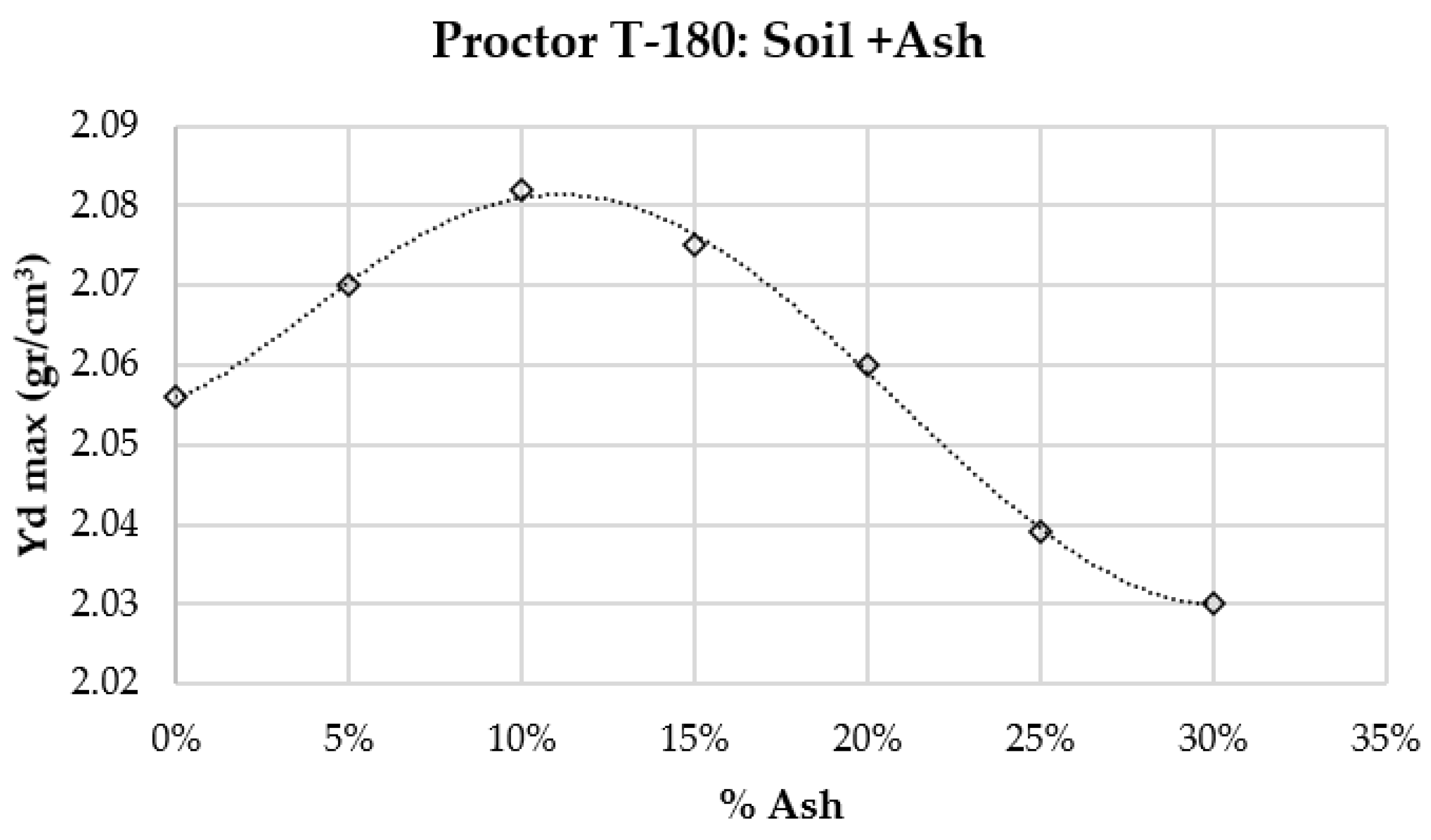

3.2.3. Proctor T-180 Compaction

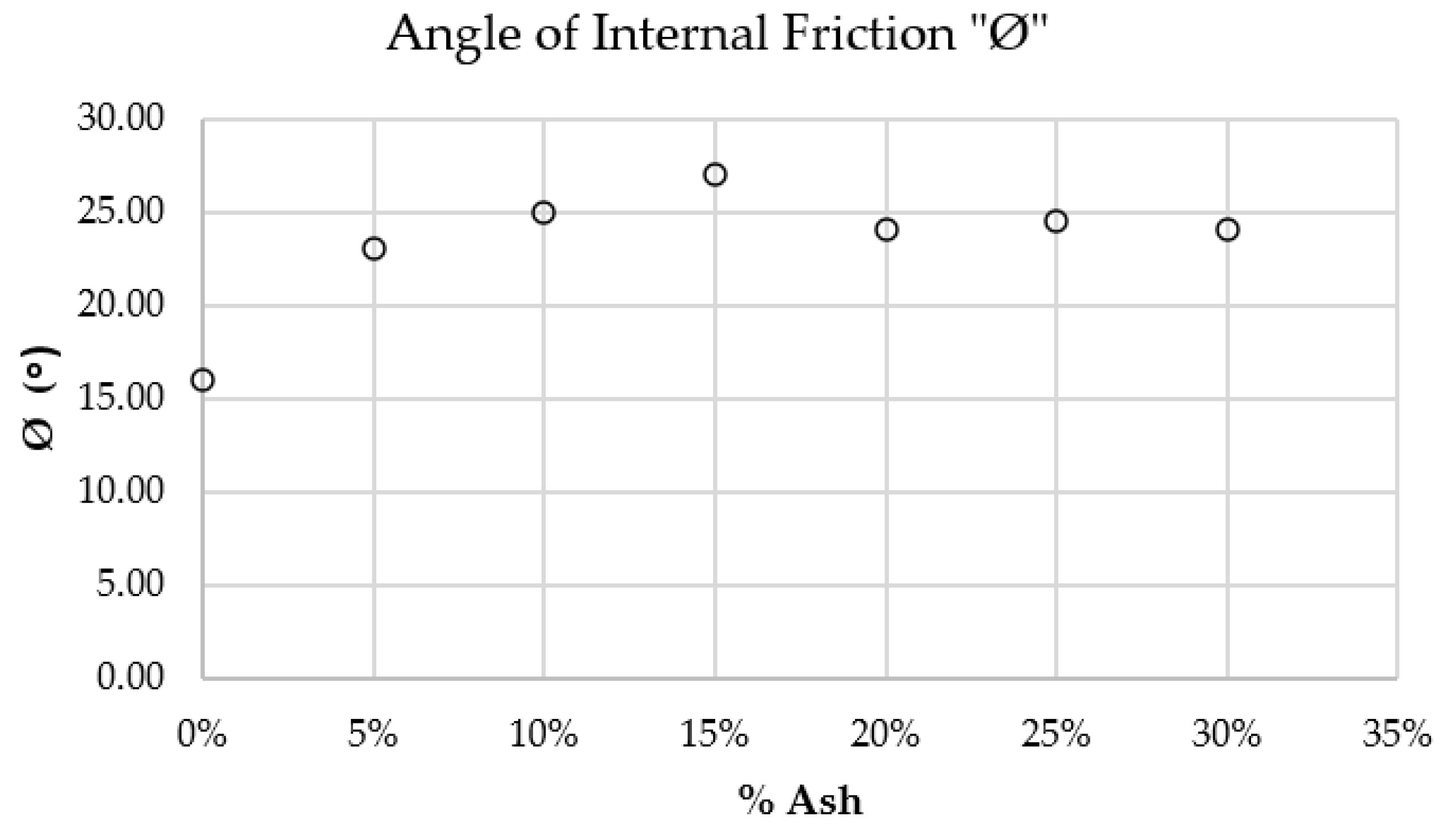

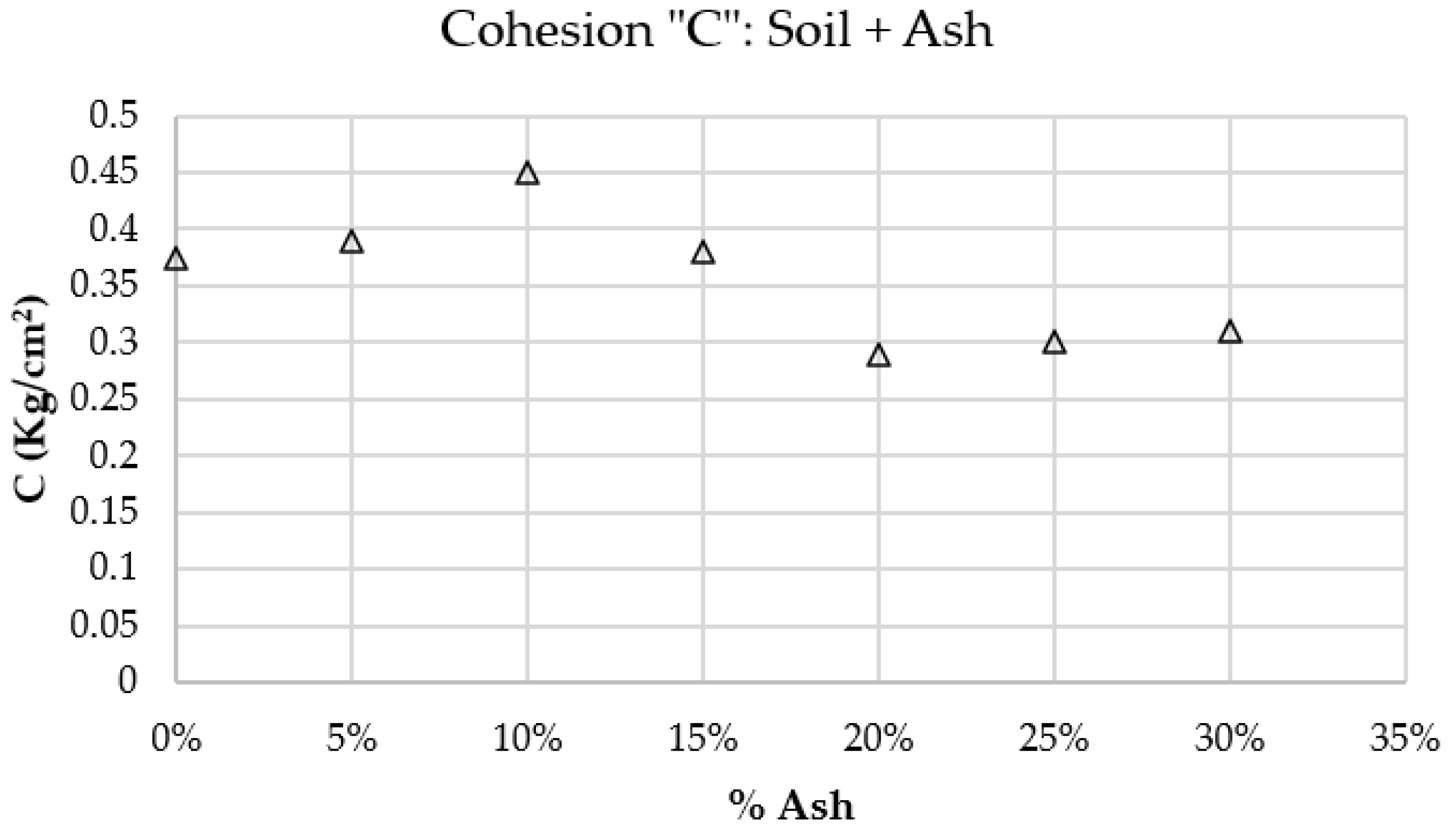

3.2.4. Direct Shear: Resistance Parameters

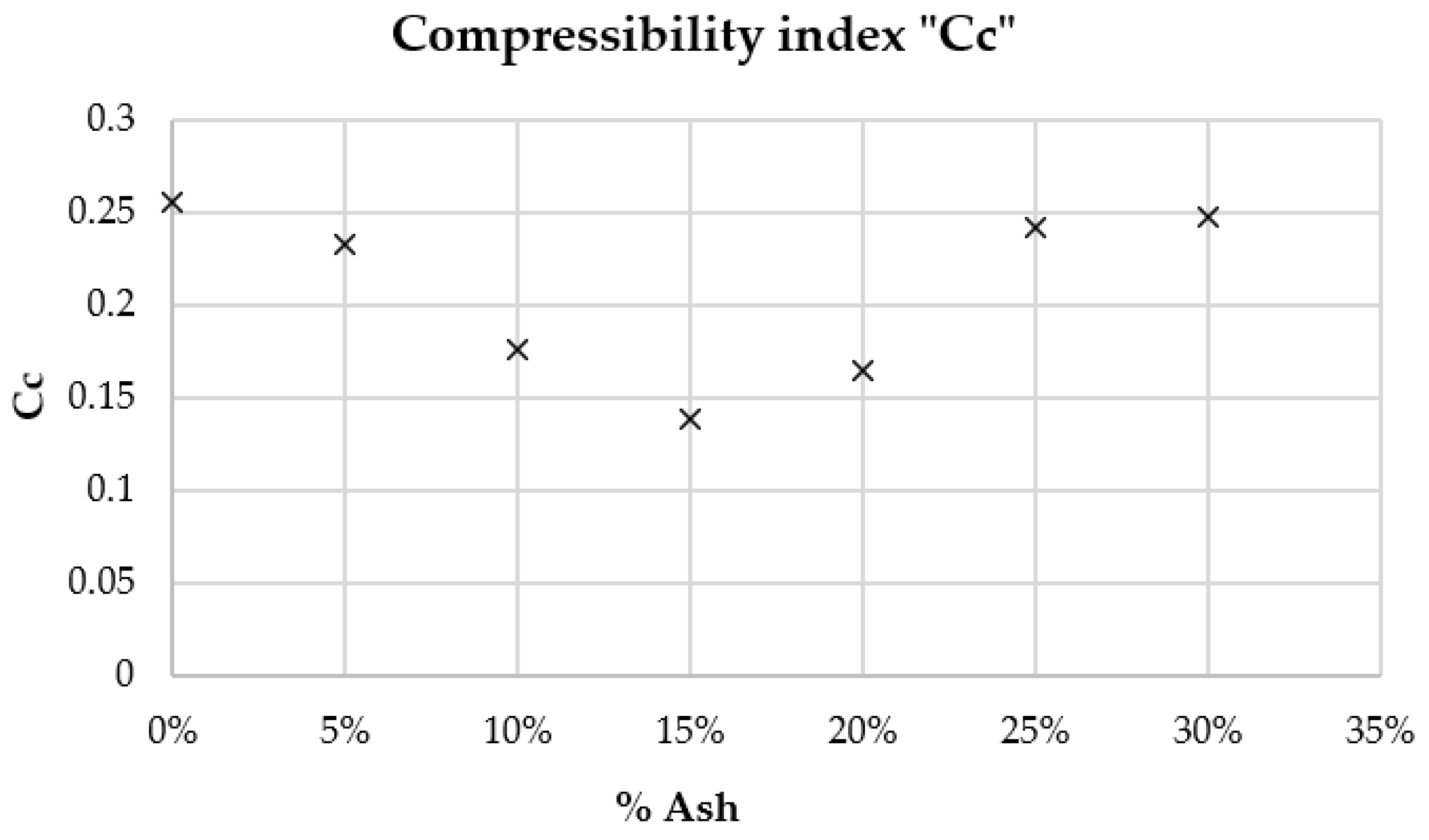

3.2.5. One-Dimensional Consolidation: Compressibility Index

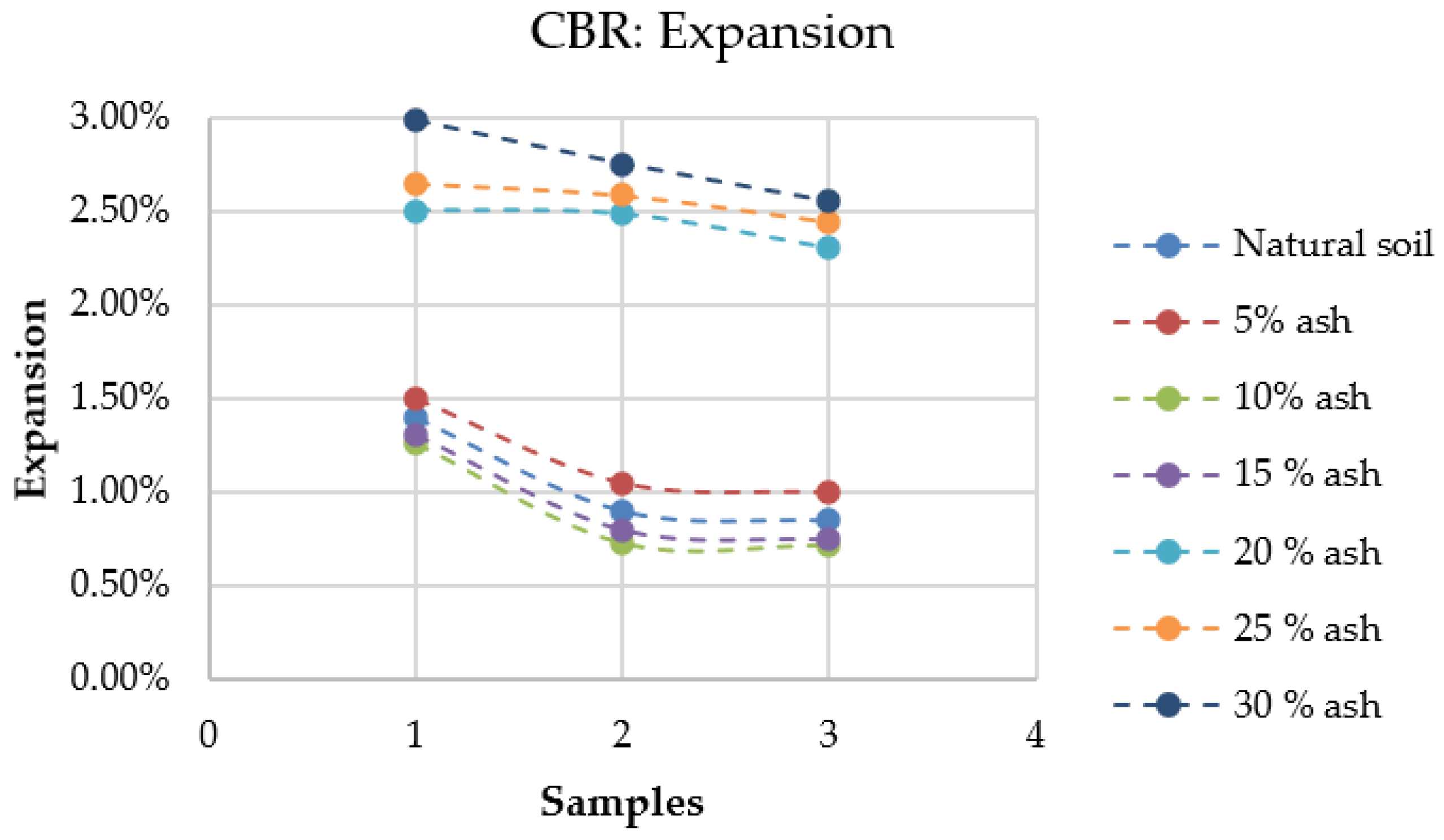

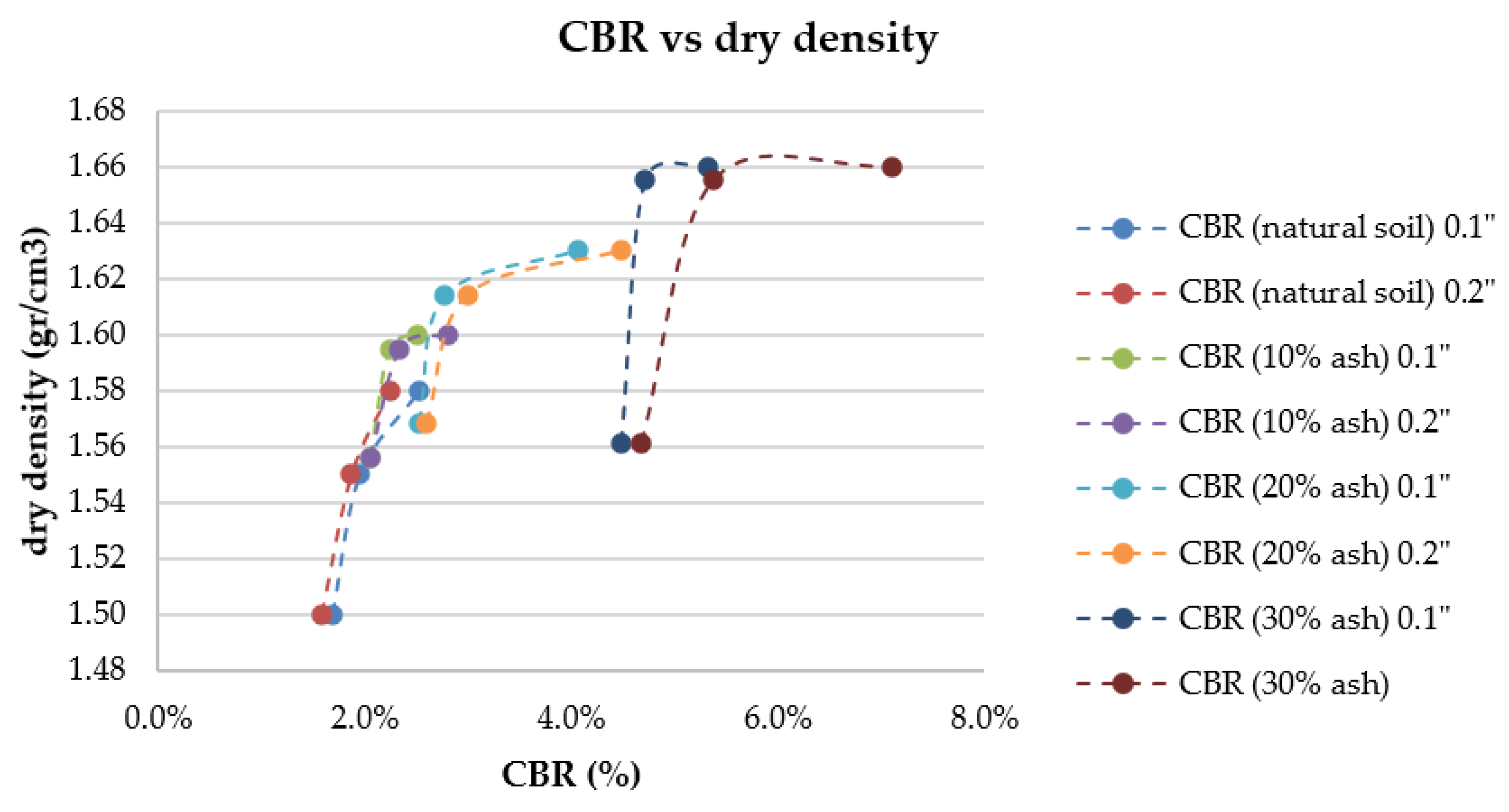

3.2.6. California Bearing Ratio (CBR) Test: Expansion and Deformation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BA | Biosolid Ashes |

| CBR | California Bearing Ratio |

| SSA | Sewage Sludge Ash |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| SS | Sewage Sludge |

| WWTP | Wastewater treatment plants |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds |

References

- Xu, G. Analysis of sewage sludge recovery system in EU in perspectives of nutrients and energy recovery efficiency, and environmental impacts. Norwegian University of Science and Technology 2014, 88. Obtained from: http://hdl.handle.net/11250/235441.

- Javier, Mateo-Sagasta.; Liqa, Raschid-Sally.; Anne, Thebo. Global wastewater and sludge production, treatment and use. P. Drechsel et al. (eds.). Wastewater Economic Asset in an Urbanizing World 2015. [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, A.; Bonfiglioli, L.; Pellegrini, M.; Saccani, C. Sewage sludge drying process integration with a waste-to-energy power plant. Waste Manag 2015, 42, 159–165. [CrossRef]

- Gherghel, A.; Teodosiu, C.; De Gisi, S. A review on wastewater sludge valorisation and its challenges in the context of circular economy. J. Clean. Prod 2019, 228, 244–263. [CrossRef]

- Kelessidis, A.; Stasinakis, A.S. Comparative study of the methods used for treatment and final disposal of sewage sludge in European countries. Waste Manag 2012, 32, 1186–1195. [CrossRef]

- Bertanza, G.; Papa, M.; Canato, M.; Collivignarelli, M.C.; Pedrazzani, R. How can sludge dewatering devices be assessed? Development of a new DSS and its application to real case studies. J. Environ. Manag 2014, 137, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Shehu, M.S.; Abdul Manan, Z.; Wan Alwi, S.R. Optimization of thermo-alkaline disintegration of sewage sludge for enhanced biogas yield. Bioresour. Technol 2012, 114, 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Elvira, S.I.; Nieto Diez, P.; Fdz-Polanco. F. Sludge minimisation technologies. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol 2006, 5, 375–398. [CrossRef]

- Sever Akdağ, A.; Atak, O.; Atimtay, A.T.; Sanin, F.D. Co-combustion of sewage sludge from different treatment processes and a lignite coal in a laboratory scale combustor. Energy 2018, 158, 417–426. [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, M. C.; Abbà, A.; Carnevale Miino, M.,; Torretta, V. What Advanced Treatments Can Be Used to Minimize the Production of Sewage Sludge in WWTPs?. Applied Sciences 2019, 9(13), 2650. [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.; Singh-Sikarwar, V.; Wafa Dastyar, J-H.; Dionysiou, D.; Wang, W.; Zhao, M. Opportunities and challenges in sustainable treatment and resource reuse of sewage sludge: A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 337, 616-641. [CrossRef]

- Fuerhacker, M.; Haile, T. M. Treatment and reuse of sludge. Waste water treatment and reuse in the mediterranean region 2011, 63-92. Obtained from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/698_2010_60.

- Nguyen, M. D.; Thomas, M.; Surapaneni, A.; Moon, E. M.; Milne, N. A. Beneficial reuse of water treatment sludge in the context of circular economy. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 28, 102651. [CrossRef]

- Vouk, D.; Nakic, D.; Stirmer, N. Reuse of sewage sludge–problems and possibilities. In Proceedings of the international conference IWWATV 2015, 1-021. Obtained from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/114529626/Vouk_et_al-libre.pdf?1715677524=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DReuse_of_Sewage_Sludge_Problems_and_Poss.pdf&Expires=1763153688&Signature=RjUTRTiQM32902IoHfB1uzBoahjz8HQz0oADEUBPAFdRWtIPW3JMS~29WpGfIjQpp2UW2Xrz00Y-Rtyjef9wg2CE0TjEYuKV9Nef0G1QwDWaFJl4J0AQgEtZ6d4d-ZYyYZz2Gu2UaxFJI5EJdnYej4MeA1qeXxp665fQc89Muu1oxIHXjr60Ynzsa09DgqBGigh4BfkkGpC-evrpHrmSFkCs0f1IXcw2-32mtil-NZ0zh9Xc1L1lAbcNj8aZ9MO~dMglUsXb5xN8mn~79W5ClpoEzvfo99QnnnCGETy5CheGi3Vk39uKKlVQHf9d3QEgwdwyAaObSvmjuTCkWe~l9Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA.

- Kumar, V.; Chopra, A. K.; Kumar, A. A review on sewage sludge (Biosolids) a resource for sustainable agriculture. Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science 2017, 2(4), 340-347. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. R. Organic contaminants in sewage sludge (biosolids) and their significance for agricultural recycling. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2009, 367(1904), 4005-4041. [CrossRef]

- Krüger, O.; Grabner, A.; Adam, C. Complete survey of German sewage sludge ash. Environmental science & technology 2014, 48(20), 11811-11818. [CrossRef]

- Roy, M. M.; Dutta, A.; Corscadden, K.; Havard, P.; Dickie, L. Review of biosolids management options and co-incineration of a biosolid-derived fuel. Waste Management 2011, 31(11), 2228-2235. [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.F.; Lin, K.L.; Hung, M.J.; Luo, H.L. Sludge ash/hydrated lime on the geotechnical properties of soft soil. J. Hazard. Mater 2007, 145 (1-2), 58-64. [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.; Dsifani, M.; Suthagaran, V. Imteaz, Select chemical and engineering properties of wastewater biosolids. J. Waste Manage 2011, 31, 2522–2526. [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.; Disfani, M.; Suthagaran, V.; Bo, M. Laboratory evaluation of the geotechnical characteristics of wastewater biosolids in road embankment. J. Mater. Civ. Eng 2013, 25, 1943–5533. [CrossRef]

- Tastan, E.; Edil, T.; Benson, C.; Adilek, H. Stabilization of organic soils with fly ash. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng 2011, 137, 1943–5606. [CrossRef]

- Wanare, R.; Iyer, K. K.; Dave, T. N. Application of biosolids in civil engineering: State of the art. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 65, 1146-1153. [CrossRef]

- Franz, M. Phosphate fertilizer from sewage sludge ash (SSA). Waste Management 2008, 28(10): 1809-1818. [CrossRef]

- Fytili, D.; Zabaniotou, A. Utilization of sewage sludge in EU application of old and new methods - A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2008, 12, 116-140. [CrossRef]

- Lundin, M.; Olofsson, M.; Pettersson, G.J.; Zetterlund, H. Environmental and economic assessment of sewage sludge handling options. Resource, Conservation and Recycling 2004, 41(4): 255-278. [CrossRef]

- EPA. Handbook Estimating Sludge Management Costs. EPA/625/6-85/010. U.S. Environmental protection agency, Cincinnati, Ohio 1985.

- EPA. http//www.epa.gov/ORD/WebPubs/Landap.html> September 1995. Retrieved on October, 2000.

- Walker, J.M. Production, use, and creative design of sewage sludge biosolids 1994, Pages 67 -74 in C.E. Clapp, W.E. Larson, and R.H. Dowdy, editors. Sewage Sludge: land utilization and the environment. American Society of Agronomy, Inc., Crop Science Society of America, Inc., Soil Science Society of America, Inc. Madison, WI. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Shen, Q.; Zhou, J.; Yang, L. Soil enzymatic activity and growth of rice and barley as influenced by organic manure in an anthropogenic soil. Geoderma 2003, 115: 149-160. [CrossRef]

- Tejada, M.; Garcia, C.; Gonzalez, J.L.; Hernandez, M.T. Use of organic amendment as a strategy for saline soil remediation: influence on the physical, chemical and biological properties of soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2006, 38: 1413-1421. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Nikolic, M.; Peng, Y.; Chen, W.; Jiang, Y. Organic manure stimulates biological activity and barley growth in soil subject to secondary salinization. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2005, 37: 1185-1195. [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.J.; Bernal, M.P. The effects of olive mill waste compost and poultry manure on the availability and plant uptake of nutrients in a highly saline soil. Bioresource Technology 2008, 99: 396-403. [CrossRef]

- Abdelbasset, L.; Scelza, R.; Scotti, R.; Rao, M.; Jedidi, N.; Gianfreda, L.; Chedly Abdelly. The effect of compost and sewage sludge on soil biologic activities in salt affected soil. Revista de la Ciencia del Suelo y Nutrición Vegetal 2010, 10(1): 40-47. [CrossRef]

- Donatello, S.; Cheeseman, C.R. Recycling and recovery routes for incinerated sewage sludge ash (ISSA): A review. Waste Manage 2013, 33, 2328-2340. [CrossRef]

- Husillos R.; Martinez-Ramirez, S.; Blanco-Varela M.T.; Donatelo, S.; Guillem, M.; Puig, J.; Fos, C.; Larrotcha, E.; Flores, J. The effect of using thermally dried sewage sludge as an alternative fuel on Portland cement clinker production. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 52, 94-102. [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, A.; Mehrdadi, N.; Jamshidi, M. Application of sewage dry sludge as fine aggregate in concrete. J. Envir. Stud 2011, Vol. 37, No. 59, 7-14. Obtained from: https://www.sid.ir/paper/3270/en.

- Monzo, J.; Paya, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Bellver, A.; Peris-Mora, E. Study of cement-based mortars containing spanish ground sewage sludge ash. Stud. Environ. Sci 1997, 71, 349-354. [CrossRef]

- Monzo, J.; Paya, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Girbes, I. Reuse of sewage sludge ashes (SSA) in cement mixtures: the effect of SSA on the workability of cement mortars. Waste Manage 2003, 23, 373-381. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.C.; Tseng, D.H.; Lee, C.C.; Lee, C. Influence of the fineness of sewage sludge ash on the mortar properties. Waste Manage 2003, 33, 1749-1754. [CrossRef]

- Cyr, M.; Coutand, M.; Clastres, P. Technological and environmental behaviour of sewage sludge ash (SSA) in cement-based materials. Cem. Concr. Res 2007, 37, 1278-1289. [CrossRef]

- Garces P.; Perez-Carrion, M.; Garcia-Alcocel, E.; Paya, J.; Monzo, J.; Borrachero, M.V. Mechanical and physical properties of cement blended with sewage sludge ash. Waste Manage 2008, 28, 2495-2502. [CrossRef]

- Paya, J., Monzo, J., Borrachero, M.V., Amahjour, F., Girbes, I., Velazquez, S.; Ordonez, L.M. Advantages in the use of fly ashes in cements containing pozzolanic combustion residues: silica fume, sewage sludge ash, spent fluidized bed catalys and rice husk ash. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 2002, 77, 331-335. [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.H. Potential use of sewage sludge ash as construction material. Resour. Conserv. Recy 1986, 13, 53-58. Obtained may 2025 from: https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/7141288.

- Kalogo, Y.; Monteith, H.; Eng, P. STATE OF SCIENCE REPORT: ENERGY AND RESOURCE RECOVERY FROM SLUDGE 2012. Obtained may 2025 from: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/titel/1887162.

- Bachmann, N. Sustainable biogas production in municipal wastewater treatment plants. IEA Bioenergy, ENVI Concept Route de Chambovey 2CH-1869 Massongex, Switzerland 2015. Obtained may 2025 from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://kh.aquaenergyexpo.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Sustainable-Biogas-Production-In-Municipal-Wastewater-Treatment-Plants.pdf.

- Pöschl, M.; Ward, S.; Owende, P. Evaluation of energy efficiency of various biogas production and utilization pathways. Applied. Energy 2010, 87(11): 3305-3321. [CrossRef]

- Halls, S. Environmentally Sound Technologies for Wastewater and Stormwater Management. Japan, Newsletter and Technical Publications 2000.

- Bories, C.; Borredon, M.-E.; Vedrenne, E.; Vilarem, G. Development of eco-friendly porous fired clay bricks using pore-forming agents: A review. Journal of Environmental Management 2014, 143, 186-196. [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.-H.; Lin, D.-F.; Chiang, P.-C. Utilization of sludge as brick materials. Advances in Environmental Research 2003, 7, 679-685. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.R.; Santos, G.T.A.; Souza, A.E.; Alessio, P.; Souza, S.A.; Souza, N.R. The effect of incorporation of a Brazilian water treatment sewage sludge on the properties of ceramic materials. Appl. Clay Sci 2011, 53, 561-565. [CrossRef]

- Petavratzi, E.; Wilson, S., Incinerated sewage sludge ash in facing bricks. Characterisation of Mineral Wastes, Resources and Processing technologies – Integrated waste management for the production of construction material. WRT177/WR0115. 2007. Obtained may 2025 from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/114529626/Vouk_et_al-libre.pdf?1715677524=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DReuse_of_Sewage_Sludge_Problems_and_Poss.pdf&Expires=1763155054&Signature=bTqWL9Xo8npiyXH0p4bVP9GAujvkUq2GgaVcmKGCuEGPkr7t6b5sfRUsm0VTxLqxv-5QWkIwpY2Hi5ZM~yj2FsZCEVbsTEMPU-Du7V~o4HZGaQN~Tw~f8hNbEB8Repop76wDWu543nRhgrB30ZCyPy7LgC0BhwJ1z8SF38-tTmZe66HGhi1iy76EF3ykPz8txhlKwV1TQlEspYM7A-V0CzoNDyozUKuRZrMnSiCFYYoVh5fpBd5Z6v0sFYuiq5922iJ2xp79yNTTsBFmM09I182Yqqc3RIv5rk6wm~uBHscMH88JkTqQwJkacGx1EHTH1qLODU5VvHqUjnIt8ohg1A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA.

- Anderson, M.; Skerratt, R.G. Variability study of incinerated sewage sludge ash in relation to future use in ceramic brick manufacture. Brit. Ceram. T 2 003, 102 (3), pp 109-113. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharif, M.M.; Attom, M.F. A geoenvironmental application of burned wastewater sludge ash in soil stabilization. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013. . Obtained may 2025 from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12665-013-2645-z. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Jeon, W.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.; Kim, K. Engineering properties of water/ wastewater-treatment sludge modified by hydrated lime, fly ash and loess. J. Water Res 2007, 36, 4177–4184. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. & Lin, D.F. Stabilization treatment of soft subgrade soil by sewage sludge ash and cement. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 162 (1), pp 321-327. [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Oyamada, T.; Hanehara, S. Applicability of sewage sludge ash (SSA) for paving materials: A study on using SSA as filler for asphalt mixture and base course material. Third International Conference on Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies 2013. Obtained may 2025 from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://www.claisse.info/2013%20papers/data/e283.pdf.

- Maghoolpilehrood, F., Disfani, M.; Arulrajah, A. Geotechnical characteristics of aged biosolids stabilized with cement and lime. Aust. Geomech. J. 2013, 48, 113–120. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274712346.

- Disfani, M. M.; Arulrajah, A.; Maghoolpilehrood, F.; Bo, M. W.; Narsilio, G. A. Geotechnical characteristics of stabilised aged biosolids. Environmental geotechnics 2015, 2(5), 269-279. [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, Y. M.; Al-Obaidi, S.; Alrub, F. Y.; Igwe, D. Geotechnical properties of clayey soil improved by sewage sludge ash. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 34-47. [CrossRef]

- Aparna, R. P. Sewage sludge ash for soil stabilization: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, Vol part 2, 392-399. [CrossRef]

- Zabielska-Adamska, K. Sewage Sludge Bottom Ash Characteristics and Potential for Use in Geotechnical Engineering. Sustainability 2019, 12(1), 39. [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.; Cabalar, A. F. USE OF SEWAGE SLUDGE ASH IN SOIL IMPROVEMENT. The International Journal of Energy and Engineering Sciences 2017, 2(3), 4-9. Obtained may 2025 from: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijees/issue/48360/612287.

- Zhang, H.; Tu, C.; He, C. Study on Sustainable Sludge Utilization via the Combination of Electroosmotic Vacuum Preloading and Polyacrylamide Flocculation. Sustainability 2025, 17(21), 9802. [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Li, H.; Duan, K.; Zhang, R.; Peng, Q.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Sun, K.; Tu, P. Optimization of Technical Parameters for the Vacuum Preloading-Flocculation-Solidification Combined Method for Sustainable Sludge Utilization. Sustainability 2025, 17(6), 2710. [CrossRef]

- Cooperativa de Servicios de Agua y Alcantarillado Sanitario de Tarija [COSAALT], 2025.

- López, R. Uso de cenizas de Biosólidos como reemplazante parcial del cemento en concreto no estructural. 29th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering Ferrol 2025, 1629-1642. [CrossRef]

- Villena, E.; Sánchez. L.; Lo Iacono. V.; Torregrosa, J-I. & Lora, J. ALTERNATIVAS DE REUSO DE LOS RESIDUALES DE UNA PTAR: ESTUDIO DE CASO EN TARIJA. 29th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering Ferrol 2025, 1222-1237. [CrossRef]

- Bowles, J. E. Engineering properties of soils and their measurement. 1992.

- ASTM International, “ASTM D2435. Standard Test Methods for One-Dimensional Con- solidation Properties of Soils Using Incremental Loading,”. pp. 1-15, 2011. 187. Obtained may 2025 from: https://store.astm.org/d2435-04.html.

- Shen L.; Zhang D. Low-temperature pyrolysis of sewage sludge and putrescible garbage for fuel oil production. Fuel 2005, 84, 809-815. [CrossRef]

- Principi P.; Villa F.; Bernasconi M.; Zanardini E. Metal toxicity in municipal wastewater activated sludge investigated by multivariate analysis and in situ hybridization. Water Research 2006, 40, 199-106. [CrossRef]

- Chin S.; Jurng J.; Lee J.; Hur J.H. Oxygen-enriched air for co-incineration of organic sludges with municipal solid waste: A pilot plant experiment. Waste Management 2008, 28, 2684-2689. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez M.C.; Larrubia M.A.; Herrera M.C.; Guerrero-Pérez M.O.; Malpartida I., Alemany L.J.; Palacios C. Valorización energética de biosólidos: algunos aspectos económicos y ambientales en la EDAR Guadalhorce (Málaga). Residuos: Revista técnica 2007, 98, 60-67. Obtained may 2025 from: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2355624.

| Test | % ash | Gs | Decrease |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 2.78 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 5 | 2.38 | -14.36 |

| 3 | 10 | 2.40 | -13.55 |

| 4 | 15 | 2.41 | -13.31 |

| 5 | 20 | 2.36 | -15.12 |

| 6 | 25 | 2.32 | -16.43 |

| 7 | 30 | 2.31 | -16.91 |

| Soil + Ashes | LL | LP | IP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 36.5 | 25.2 | 11.3 |

| 5% | 35.5 | 27.5 | 8 |

| 10% | 34 | 29.5 | 4.5 |

| 15% | 33 | 26.7 | 6.3 |

| 20% | 34.3 | 27.3 | 7 |

| 25% | 35 | 30.9 | 4.1 |

| 30% | 36.3 | 28 | 8.3 |

| Samples (number of blows) | Expansion (natural soil) | Expansion (5% Ash) | Expansion (10% Ash) | Expansion (15% Ash) | Expansion (20% Ash) | Expansion (25% Ash) | Expansion (30% Ash) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.40% | 1.500% | 1.261% | 1.30% | 2.50% | 2.65% | 2.98% | |

| 2 | 0.90% | 1.050% | 0.730% | 0.80% | 2.48% | 2.58% | 2.75% | |

| 3 | 0.85% | 1.000% | 0.720% | 0.75% | 2.30% | 2.44% | 2.55% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).