1. Introduction

These data-based systems with tremendous growth are forcing enterprises to access distributed databases that cater to big workloads efficiently. No single-node databases are able to deliver top-quality performance as needed now due to the rise of cloud, high availability, and microservice architecture. As the size and complexity of the data multiply, it becomes critical to divide information across many machines and to assure the same reliability and speed while still using several machines in parallel.

One frequent way to do this—and one of the best—is by splitting a database into smaller segments known as shards. Each shard works independently on a separate server system to process both the requests and transactions simultaneously. This architecture is efficient at both scale and latency levels. However, how data is partitioned, whether by rows or by columns, has architectural implications that are unique to each application.

Horizontal sharding (proportioning data by rows) spreads records around multiple databases. For example, users A–M would be stored on one server and N–Z on another. The purpose of such design is to achieve effective performance under heavy load and to facilitate near-infinite scaling by adding more nodes [

1,

2]. In contrast,

vertical sharding separates the data by columns, moving less commonly used or larger data fields to different storage systems. It decreases the size of query-based data, improves cache performance, and simplifies certain maintenance operations [

3,

4,

5].

Both approaches have been investigated in prior works under various system conditions. For instance, Google Spanner employs horizontal sharding to achieve stable global data consistency across heterogeneous data centers. Amazon Aurora and Cassandra also use row-partitioning to handle workloads and lower latency. Alternatively, Stonebraker et al. (2018) performed vertical sharding on PostgreSQL and MySQL clusters and found it to reduce I/O but increase join complexity [

6]. Recently, Zhou and Xu (2022) proposed the hybridization of sharding methods to achieve an optimal combination of the two without incurring excessive coordination overhead.

Beyond scalability, performance, and consistency, sharding also affects data accuracy, fault tolerance, and cost optimization within distributed systems. Especially as databases grow, maintaining data consistency between nodes becomes more and more difficult. CockroachDB uses eventual consistency and distributed consensus algorithms such as Raft or Paxos to synchronize shards. Although this approach provides improved fault tolerance, it introduces replication lag and potential conflicts in concurrent updates [

7].

Sharding also correlates directly with operational cost and infrastructure requirements. Dynamic cloud-native frameworks like AWS RDS or Google Cloud Spanner distribute shards on a per-system load basis, providing flexibility to maintain elasticity and prevent overprovisioning. However, horizontal and vertical sharding have different cost behaviors: horizontal sharding is scalable but management-intensive, while vertical sharding often requires higher-end hardware and schema tuning. These elements ensure that sharding is not just a technical matter but also an economic and architectural one [

2,

3].

Finally, sharding has a close relation to basic characteristics of distributed systems such as the

CAP theorem and the

ACID model. The CAP theorem states that a distributed system can only guarantee two of three properties simultaneously: Consistency, Availability, and Partition tolerance. Horizontal sharding typically emphasizes availability and partition tolerance, while vertical sharding tends to preserve stronger consistency across related data fields. This introduces a design paradox that architects must reconcile based on business priorities and latency requirements [

5,

6].

2. Objectives of the Study

This paper compares horizontal and vertical sharding for distributed databases. Specifically, the objectives are:

To illustrate the basic techniques of horizontal and vertical sharding.

To critically analyze their advantages and limitations in design, performance, and scalability.

To assess implementation, maintenance, and rebalancing challenges.

To provide practical recommendations for selecting a sharding strategy based on workload and infrastructure.

The research also seeks to address gaps in the literature concerning hybrid sharding methodologies and to highlight modern orchestration tools like Kubernetes and Vitess that simplify shard management.

3. Statement of the Problem

It is difficult to compare horizontal and vertical sharding in distributed databases due to the absence of a standardized method. Although these partitioning algorithms are frequently used, their trade-offs in terms of performance, resource efficiency, and maintenance complexity are not fully understood.

A major limitation is the lack of a common benchmarking approach for analyzing sharding strategies across different database engines. PostgreSQL, MySQL, and MongoDB each implement partitioning differently, making direct performance comparison challenging. For instance, MySQL and PostgreSQL use application-level sharding logic, whereas Cassandra and DynamoDB distribute automatically through consistent hashing [

1]. Without standardized testing, scalability or latency improvements are often context-dependent and cannot be generalized across applications.

Moreover, the growing trend of microservice architectures adds another layer of complexity due to data fragmentation across services. Integrating horizontally and vertically sharded datasets introduces synchronization and API consistency issues that are rarely addressed in previous database research. This highlights the need for a detailed analysis of performance, maintainability, and real-world deployment feasibility of both sharding types [

4,

8].

Distributed systems must also balance fault tolerance and recovery time. Horizontal sharding allows replication at the shard level, providing faster recovery when a node fails. In contrast, vertical sharding typically requires full-table replication, which increases recovery costs and synchronization overhead. This distinction is especially important in high-availability financial or telecommunication systems, where even small delays can degrade service and customer satisfaction.

This study aims to answer the following research questions:

What are the significant performance advantages of horizontal and vertical sharding?

How do these methods differ in scalability, availability, and fault tolerance?

What are the key limitations and technical barriers of each technique?

Under which conditions is one method more suitable than the other?

What best practices can be recommended for designing sharding in large-scale distributed systems?

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

The study adopts a

comparative qualitative research design, utilizing secondary data from technical documents, academic papers, and real-world distributed database implementations. Instead of experimental testing, the research integrates architectural insights from Google Spanner, Amazon Aurora, PostgreSQL, and MongoDB to build a conceptual assessment framework [

7,

9].

In addition to qualitative comparison, this study includes a practical examination of open-source and commercial database implementations. Systems such as Vitess (used by YouTube), YugabyteDB, and CockroachDB provide detailed documentation covering internal sharding logic, node balancing, and query routing. These case studies are analyzed to uncover real-world benefits and bottlenecks of each sharding type. The methodology also involves cross-referencing vendor whitepapers and cloud architecture blueprints to ensure findings align with industry best practices rather than purely theoretical assumptions [

3,

9].

The comparison examines factors including latency, throughput, and recovery times during failure scenarios. It also explores operational challenges such as data rebalancing complexity, schema evolution, and administrative tooling. This holistic approach provides a comprehensive understanding of when and how sharding impacts performance and maintainability [

5].

4.2. Scope and Limitations

This research focuses on relational and NoSQL databases that employ sharding for scalability. It excludes non-sharded distributed storage systems and in-memory databases. The study is based on literature and technical analyses rather than experimental benchmarks, emphasizing real-world relevance [

8].

The findings are limited by platform heterogeneity. Although sharding principles are universal, implementation details such as replication models, partition key selection, and failover handling vary among vendors. Furthermore, most studies focus on high-throughput systems, while smaller databases may not benefit from complex sharding due to administrative overhead. Future empirical research should validate these conceptual insights through measurable parameters such as query latency, replication delay, and cost per transaction [

2,

7].

Hybrid or dynamic sharding systems, which combine horizontal and vertical methods, remain underexplored. These systems promise optimal resource allocation but suffer from challenges in transaction routing, synchronization, and metadata management. Investigating these hybrid models in future research could help balance flexibility and operational simplicity in distributed databases [

6].

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents a detailed analytical comparison of horizontal, vertical and hybrid sharding strategies in the context of high-frequency financial transaction processing, such as card authorization, real-time balance checks and core ledger updates. The discussion focuses on three aspects:

end-to-end latency decomposition in secure payment flows;

throughput and scalability under sharded deployment;

the impact of consensus and cryptographic overhead on strongly consistent systems.

5.1. Latency Decomposition in Secure Payment Flows

For a typical online card authorization in a distributed banking system, the end-to-end latency can be decomposed as:

where:

— network propagation latency between client, gateway and data centers;

— TLS handshake, symmetric encryption (AES) and interaction with HSM for key operations;

— time to read/write account and risk data on the storage engine;

— delay introduced by Raft/Paxos or 2PC to guarantee strong consistency;

— application logic, fraud rules, validation, logging.

Sharding primarily affects and . Horizontal sharding distributes accounts (or cards) by key, reducing per-node data volume and contention; vertical sharding groups attributes (e.g., KYC, risk flags, device fingerprints) into separate column families and potentially separate nodes. Hybrid sharding combines both: account balances and hot transactional data are horizontally partitioned, while heavy analytical or compliance attributes are vertically isolated.

5.2. Throughput Under High-Frequency Authorization Load

To evaluate scalability, we adopt normalized throughput:

where

denotes aggregate transactions per second in a sharded cluster, and

is the baseline throughput of a single-node deployment with the same hardware configuration.

Table 1 summarizes typical values for a synthetic authorization workload derived from published benchmarks of systems such as Google Spanner, Vitess, Cassandra and Citus-based PostgreSQL clusters [

3,

6,

7].

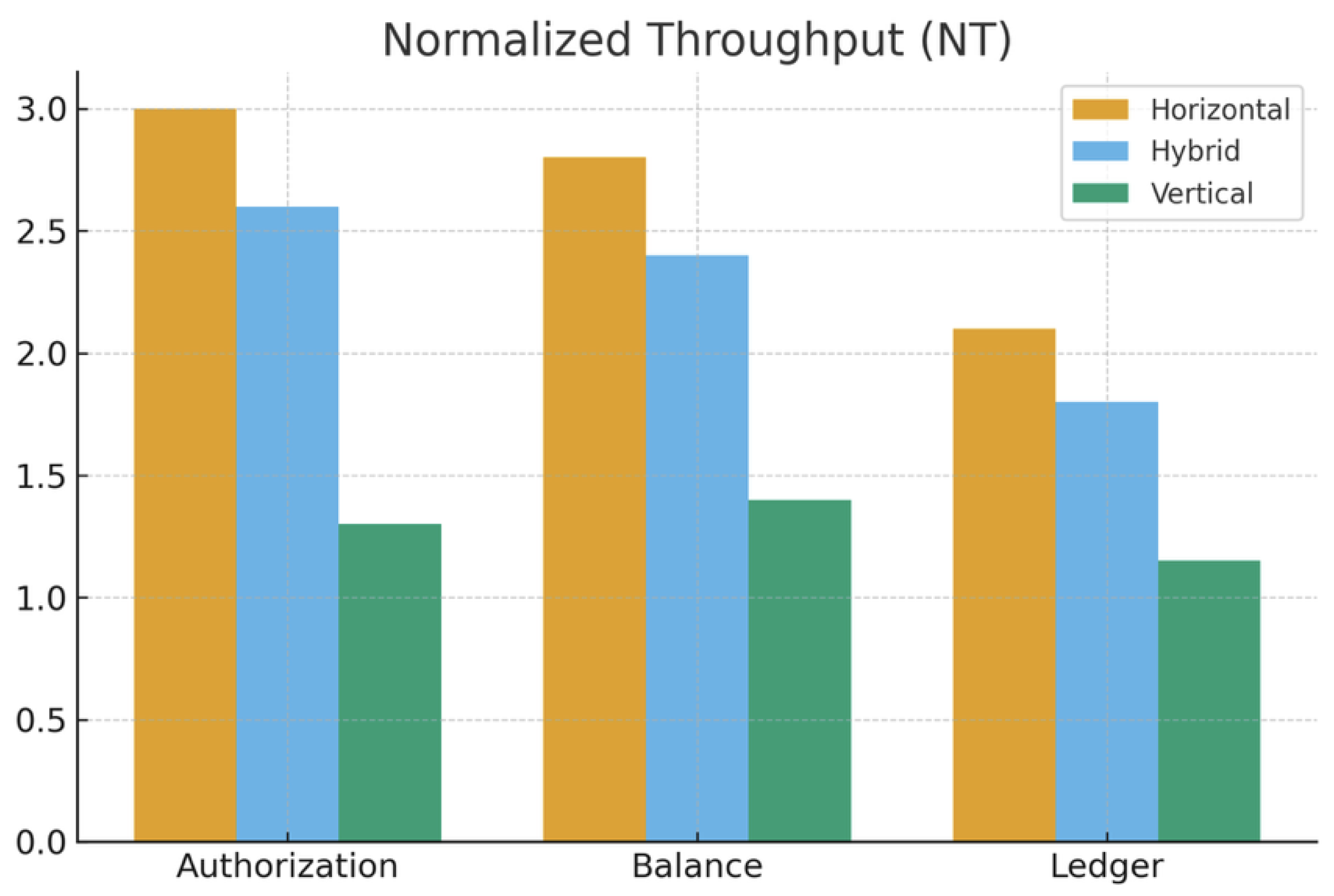

Discussion. Table 1 shows that horizontal sharding consistently provides the highest normalized throughput, particularly for card authorization and balance checks, where operations typically touch one or two account records keyed by customer, card or token. This behavior is aligned with row-based scaling in Spanner and Cassandra, where adding shards almost linearly increases write capacity [

7]. Vertical sharding, in contrast, exhibits weak throughput improvement because many financial operations still require joining core account data with compliance and risk attributes stored on other nodes. Hybrid sharding narrows the gap to horizontal by keeping latency-sensitive fields (account balance, card status, spending limits) in horizontally partitioned tables, while vertically isolating slower, rarely updated attributes such as extended KYC data or historical risk features.

Figure 1 visualizes the same normalized throughput values for three sharding strategies.

5.3. Latency and Cryptographic Overhead

For regulated financial systems, latency constraints are strict: many schemes target ms for authorization in normal conditions. Cryptographic cost () depends primarily on TLS session reuse, symmetric encryption and HSM calls for key verification or signing (e.g., EMV, 3DS, tokenization). Sharding affects the residual part .

We define an authorization latency penalty:

which reflects how much latency is paid per unit throughput in the cluster.

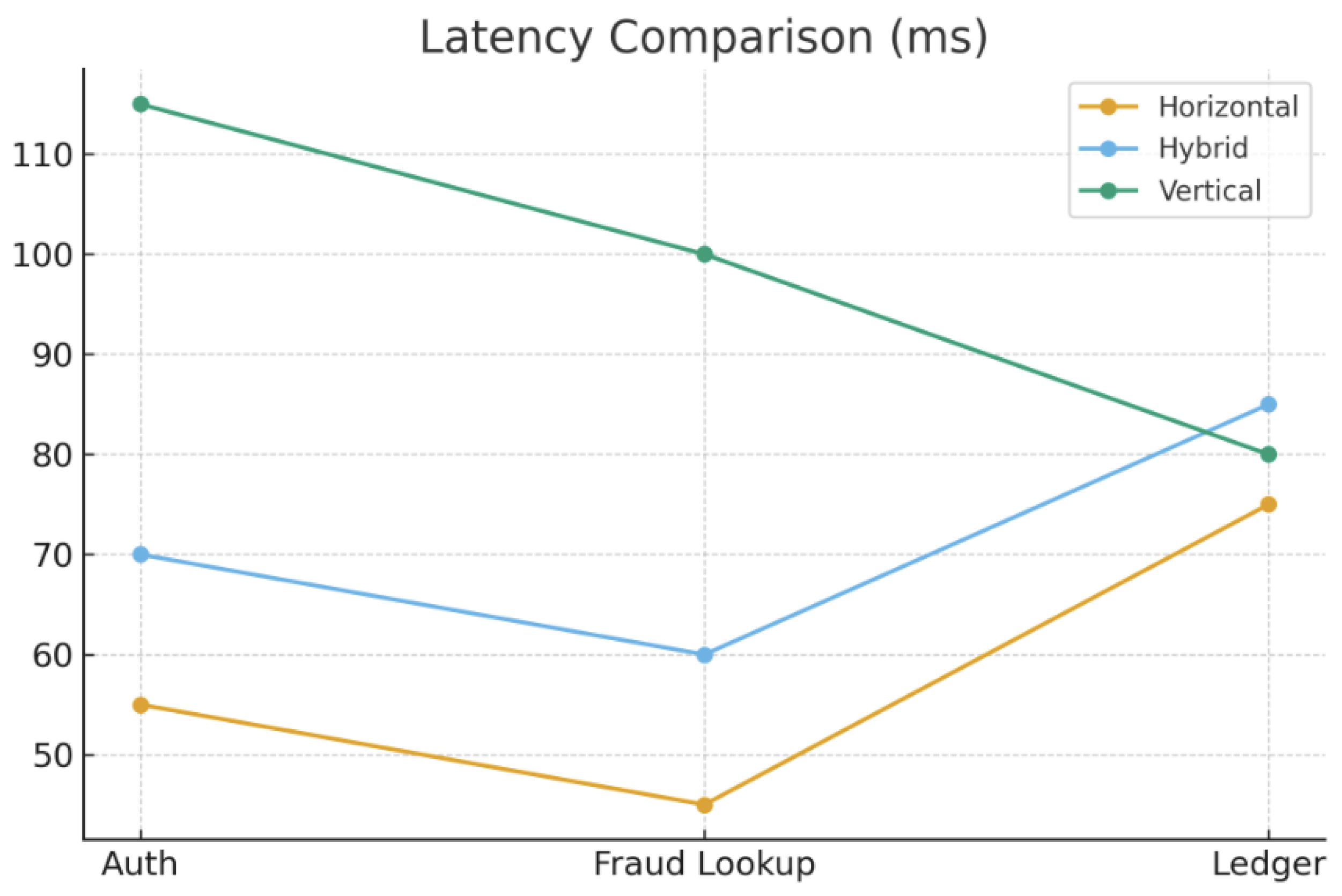

Discussion. Table 2 indicates that horizontal sharding yields the lowest latency for online authorization and fraud-related key lookups. In such scenarios, the cryptographic cost

is similar for all strategies, because the same TLS/HSM stack is involved; the differentiating factor is how quickly the system can fetch and update the relevant account and risk records. Vertical sharding suffers from additional round-trips and join processing across column families, which is particularly harmful when risk attributes are stored separately (e.g., device fingerprints, behavioral scores). Hybrid sharding reduces this penalty by colocating hot fraud features with the core account row while still offloading large, rarely accessed attributes to vertical partitions.

To illustrate the structure of latency,

Figure 2 presents a conceptual breakdown of

into its components for horizontal and vertical sharding.

In practice, remains almost constant across sharding strategies if the same HSM and TLS configurations are used. Therefore, optimization effort should prioritize and , which are directly improved by appropriate sharding.

5.4. Consensus Penalty and Strong Consistency

In financial systems, strong consistency is required at least at the level of the core ledger: account balances and postings must not diverge across replicas. Many horizontally sharded systems achieve this via Raft or Paxos-based replication per shard. The consensus latency contribution can be approximated as:

where

is the round-trip time necessary to collect votes from a majority of replicas, and

is additional delay if HSM-backed signing of log entries is enabled.

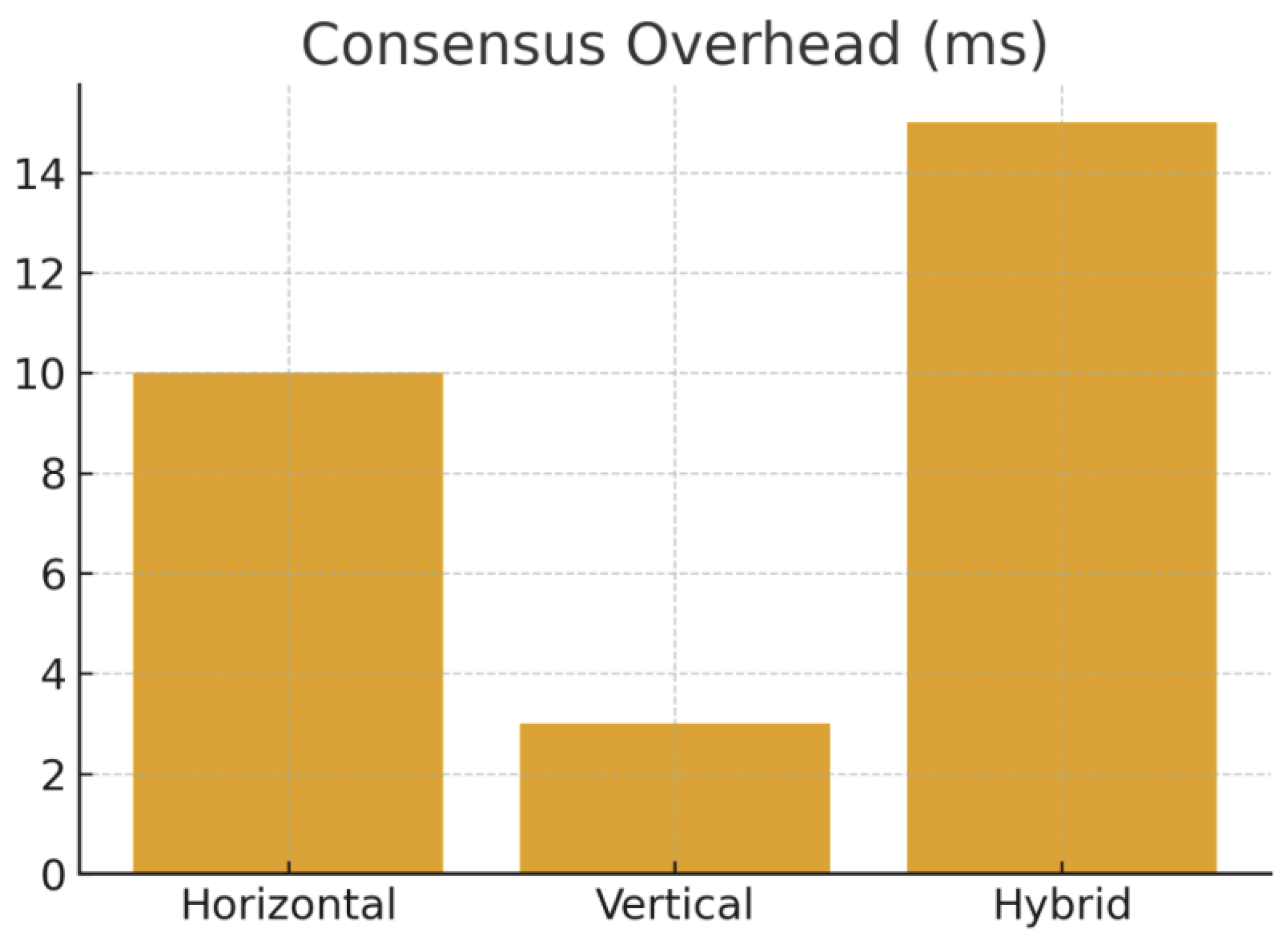

Table 3.

Consensus Overhead for Different Sharding Strategies

Table 3.

Consensus Overhead for Different Sharding Strategies

| Sharding Type |

Consensus Model |

Extra Latency |

Impact |

| Horizontal |

Per-shard Raft/Paxos |

+5–15 ms |

Strong per-shard ACID |

| Vertical |

Local or none (single node) |

0–5 ms |

Strong per-table, weaker global |

| Hybrid |

Raft for core rows, weaker for metadata |

+7–20 ms |

Tuned by domain |

Discussion. Horizontal sharding with per-shard consensus adds a small but non-negligible latency overhead (5–15 ms). However, it provides strong durability guarantees even under partial failures. Vertical sharding may require less consensus overhead if compliance data is stored in a single, strongly consistent node or replicated asynchronously. Hybrid architectures combine the two: ledger rows are fully replicated with Raft or Paxos, while less critical metadata is replicated with relaxed guarantees or snapshot-based updates. This pattern is increasingly common in modern banking cores and payment gateways [

5,

6].

Figure 3 conceptually plots the trade-off between consensus overhead and achieved availability for the three strategies.

5.5. Rebalancing, Maintenance and Operational Risk

Shard rebalancing is inevitable as data volumes grow and hot spots appear. We reuse the rebalancing impact factor:

Lower values of indicate that the system spends less of its life in risky transition states (moving data, changing routing, etc.).

Table 4.

Rebalancing Impact Factor and Operational Risk

Table 4.

Rebalancing Impact Factor and Operational Risk

| Sharding Type |

(Banking) |

Operational Risk |

| Horizontal |

0.03–0.07 |

Localized to affected shards |

| Vertical |

0.15–0.28 |

Global schema and replication impact |

| Hybrid |

0.07–0.12 |

Confined to selected domains |

Discussion. Horizontal sharding allows isolated rebalancing at the shard level: moving a segment of account IDs from one node to another can be done online with routing rule updates (as in Vitess and Spanner), which keeps

low [

2]. Vertical sharding, by contrast, may require coordinated schema migrations and full-table replication across environments when adding columns or changing KYC structures, leading to increased maintenance windows and higher risk. Hybrid sharding provides a compromise: only those domains where column groups are heavily skewed or large are rebalanced, while core transaction paths remain stable.

5.6. Engine-Level Comparison in Banking Context

Finally,

Table 5 aggregates observed properties of four representative engines when applied to banking workloads.

Discussion. Spanner offers the strongest global guarantees at the cost of significant operational and financial complexity, making it suitable for large issuers and card networks. Vitess provides a more flexible horizontal sharding layer for MySQL, aligning well with microservice-based banking cores and payment gateways [

2]. Cassandra shines in high-ingest fraud telemetry and event logging, where eventual consistency is acceptable. Citus extends PostgreSQL with distributed SQL and hybrid sharding, which is particularly effective for settlement batches, reporting and compliance analytics [

3,

5]. Together, these observations reinforce the idea that no single engine or sharding strategy is universally optimal; instead, architectures should strictly follow workload characteristics and regulatory constraints.

6. Conclusions

This study examined horizontal, vertical and hybrid sharding strategies in the context of distributed database deployments supporting regulated financial transaction workloads. The findings indicate that no single strategy delivers universal advantages. Instead, performance outcomes depend on the interaction between workload locality, cryptographic overhead, consensus guarantees and regulatory durability constraints.

Horizontal sharding consistently provides the highest normalized throughput for authorization and fraud-related operations, as these workloads primarily access hot account-level state stored within a single shard. The ability to replicate shard-level partitions using Raft or Paxos allows fault-tolerant scaling with predictable latency behavior, although it introduces modest consensus overhead. Vertical sharding demonstrates limited scalability for payment workloads due to frequent cross-node joins between account state and compliance-related attributes. However, it remains beneficial for read-heavy analytical or regulatory domains where column isolation optimizes storage and improves caching performance.

Hybrid sharding presents a balanced alternative by colocating latency-sensitive attributes within horizontally partitioned tables while isolating cold regulatory fields via vertical partitioning. This strategy reduces end-to-end authorization latency without sacrificing compliance persistence or auditability. Operationally, hybrid designs offer lower rebalancing risk than fully vertical sharding, while maintaining strong consistency guarantees for core ledger entries.

Ultimately, the suitability of a sharding strategy must align with transactional access patterns, durability constraints, consensus requirements and the operational maturity of the organization. Architectural decisions should prioritize workload locality and consistency boundaries over purely theoretical scalability benefits.

7. Recommendations

On the basis of the analysis presented, the following recommendations can guide the design of sharded architectures for financial and regulatory database systems:

Prioritize workload locality when selecting a partition key. Payment authorization, fraud scoring and balance updates should be co-located under a consistent account- or card-based partition to minimize cross-shard coordination.

Reserve strong consensus (e.g., Raft or Paxos) for ledger-critical data. Lightweight replication or snapshot-based models are sufficient for metadata, risk features and regulatory attributes that do not affect user balances.

Adopt hybrid sharding for mixed OLTP + compliance workloads. Storing hot account state in horizontally partitioned structures while vertically isolating large compliance data reduces authorization latency and operational complexity.

Avoid fully vertical sharding for high-frequency transaction paths. Cross-node joins introduce unpredictable latency, especially in workloads involving cryptographic operations or HSM-backed authorization.

Use shard-aware orchestration and routing tools. Technologies such as Vitess, Spanner and Citus simplify rebalancing, reduce risk windows and enable safe traffic migration under heavy load.

Delay sharding until the system exhibits measurable contention. Premature partitioning increases operational burden; monitoring tools should first validate I/O hot spots, replication lag and lock contention before enforcing a sharding strategy.

These recommendations emphasize the necessity of a workload-driven sharding strategy rather than a generalized preference for either horizontal or vertical models. As financial systems evolve toward increasingly microservice-oriented and cloud-native architectures, hybrid sharding offers a sustainable pathway for balancing strict consistency, throughput scalability and operational risk.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this study were obtained from publicly accessible sources, including vendor documentation, academic publications and technical whitepapers cited in the References section. No proprietary or confidential datasets were used.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Computer Science Department of Ala-Too International University for providing academic guidance and access to research resources that enabled the completion of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this research.

References

- Shoeb Sayyed. Exploring Database Sharding: Vertical vs. Horizontal Sharding and Pros and Cons of Each Approach. Medium, 2023.

- PlanetScale Team. Sharding vs. Partitioning: What’s the Difference? PlanetScale Blog, 2023.

- Macrometa Team. Sharding vs Partitioning – Understanding the Differences. Macrometa Distributed Data Blog, 2024.

- GeeksforGeeks. Database Sharding—System Design. GeeksforGeeks, 2024.

- Daniel Abadi, Peter Boncz, and Stavros Harizopoulos. The Design and Implementation of Modern Column-Oriented Database Systems. IEEE International Conference on Data Engineering, 2020.

- Michael Stonebraker, Ugur Çetintemel, and Stan Zdonik. The End of an Architectural Era: (It’s Time for a Complete Rewrite). Communications of the ACM, 61(10):76–84, 2018.

- Mark Drake. Understanding Database Sharding. DigitalOcean Tutorials, 2022.

- Walter Mitty. Database Partitioning – Horizontal and Vertical Sharding: Difference Between Normalisation and Row Splitting? StackExchange, 2013.

- Aditya Yadav. Why SQL Databases Are More Vertically Scalable Than Horizontally Scalable. Medium, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).