Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

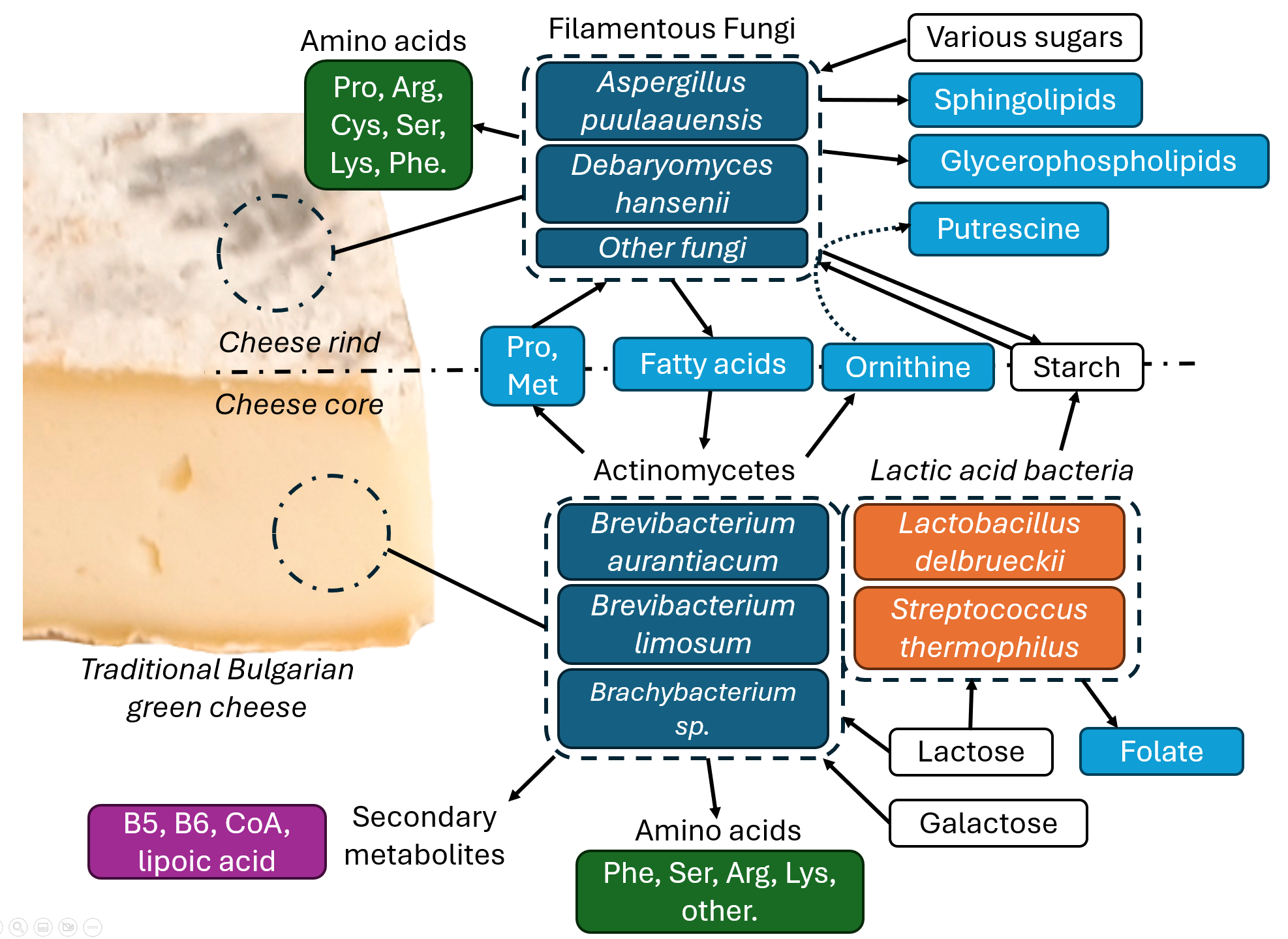

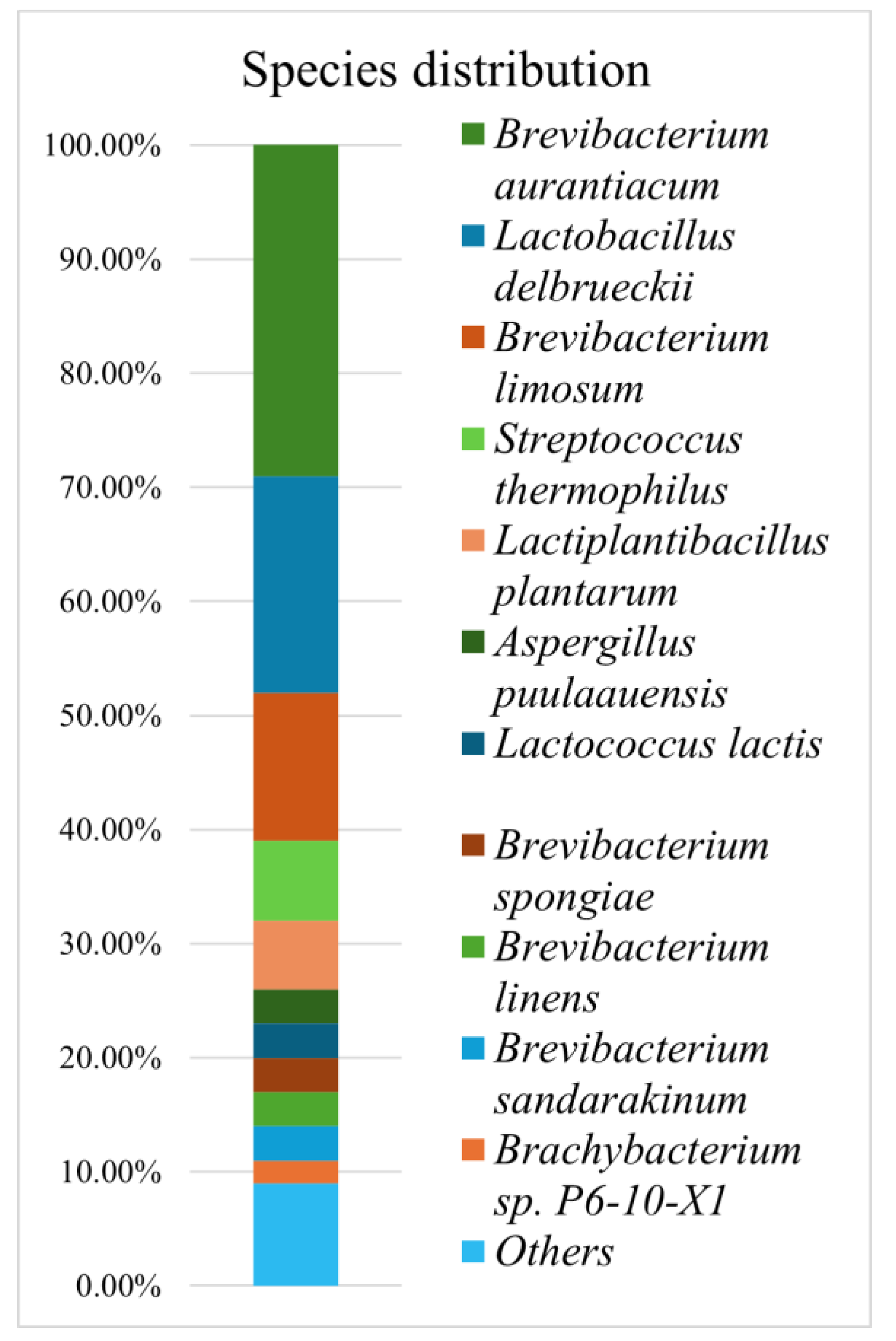

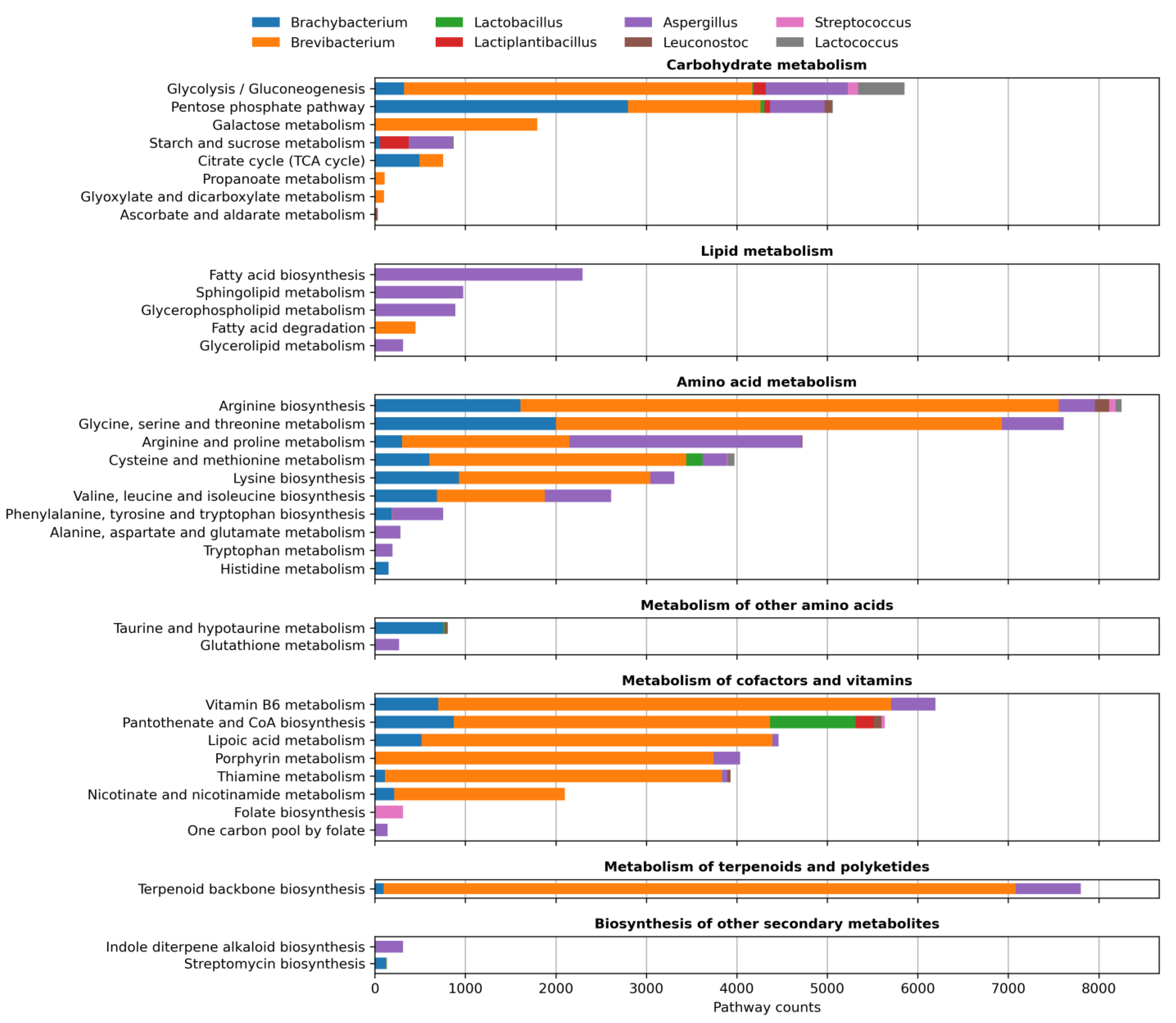

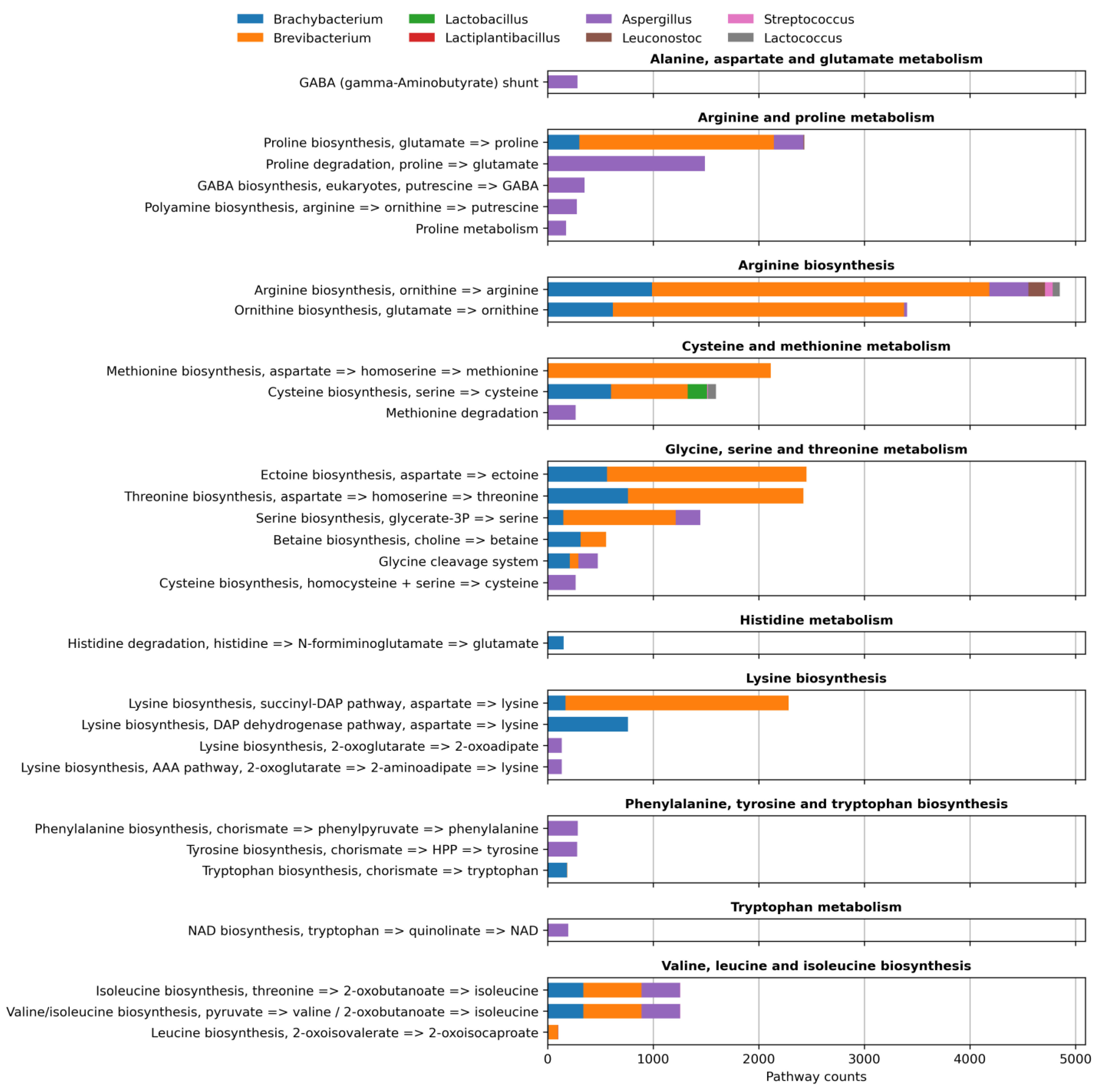

The distinct sensory properties of artisanal cheeses are defined by unique microbial communities and the key compounds they produce during maturation. Traditional Bulgarian green cheese is only produced in the village of Cherni Vit. To better understand the unique microbial community of this type of cheese, we performed shotgun metagenomic sequencing on a sample of the cheese. We found the dominant microorganisms are various species from the genus Brevibacterium (51%), most notably B. aurantiacum (29%). While having a much lower abundance, the genus Brachybacterium (2%) also plays an important role in ripening. Lactic acid bacteria, specifically Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (19%) and Streptococcus thermophilus (7%) also represented a significant share of the community composition. Functional profiling suggests Brevibacterium is a major producer of amino acids such as Phe, Arg, and Lys, as well as cofactors and vitamins like B5 and B6, and lipoic acid. We found the mold Aspergillus puulaauensis (3%) plays a key role in both lipid and amino acid metabolism within the community, despite its low abundance. No pathogens were present, but genes and plasmids encoding antibiotic resistance were detected at low concentrations. We found green cheese consumption is safe, and could be a source of useful secondary metoblites.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, Storage and Preparation

2.2. Sample Sequencing and Quality Control

2.3. Taxonomic Profiling

2.4. Functional Profiling

2.5. Metagenome Assembled Genome (MAG) Assembly, Binning and Annotation

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing

3.2. Taxonomic Profiling

3.3. Functional Profiling

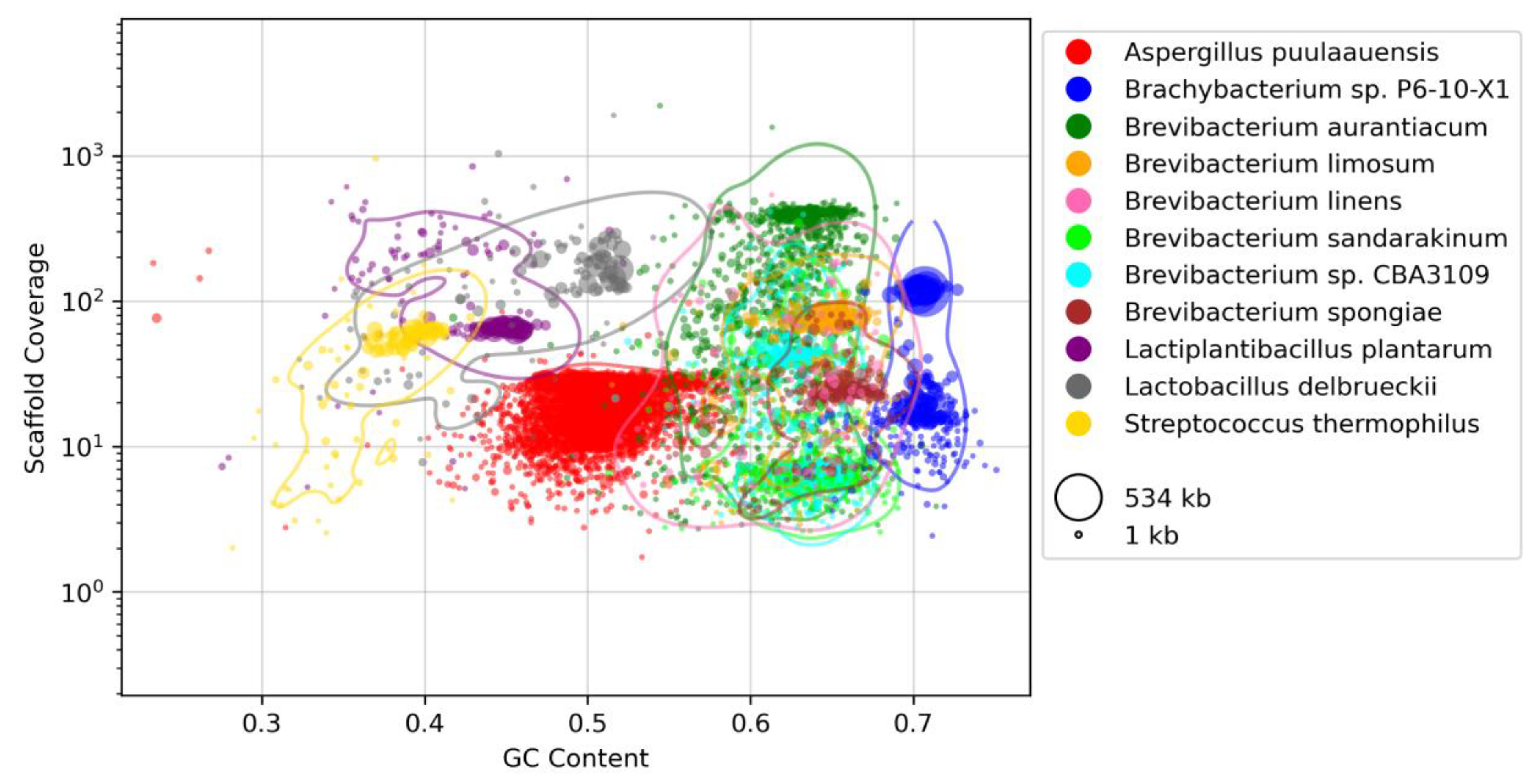

3.4. Metagenome Assembly and Binning

3.5. Bacterial Resistance Annotation

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of Actinomycetes in Green Cheese Ripening

4.2. Role of LAB in Green Cheese Ripening

4.3. Role of Mold in Green Cheese Ripening

4.4. Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Genes in Green Cheese

4.5. Comparison Between Taxonomic Profile Results from Shotgun Sequencing and Amplicon Sequencing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beresford, T.P.; Fitzsimons, N.A.; Brennan, N.L.; Cogan, T.M. Recent Advances in Cheese Microbiology. Int. Dairy J. 2001, 11, 259–274, doi:10.1016/S0958-6946(01)00056-5.

- Dimov, S.G.; Gyurova, A.; Zagorchev, L.; Dimitrov, T.; Georgieva-Miteva, D.; Peykov, S. NGS-Based Metagenomic Study of Four Traditional Bulgarian Green Cheeses from Tcherni Vit. LWT 2021, 152, 112278, doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112278.

- Breitwieser, F.P.; Baker, D.N.; Salzberg, S.L. KrakenUniq: Confident and Fast Metagenomics Classification Using Unique k-Mer Counts. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 198, doi:10.1186/s13059-018-1568-0.

- Lu, J.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Thielen, P.; Salzberg, S.L. Bracken: Estimating Species Abundance in Metagenomics Data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2017, 3, e104, doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.104.

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.-G. Sensitive Protein Alignments at Tree-of-Life Scale Using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368, doi:10.1038/s41592-021-01101-x.

- Aramaki, T.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Endo, H.; Ohkubo, K.; Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Ogata, H. KofamKOALA: KEGG Ortholog Assignment Based on Profile HMM and Adaptive Score Threshold. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2251–2252, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz859.

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P.A. metaSPAdes: A New Versatile Metagenomic Assembler. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 824–834, doi:10.1101/gr.213959.116.

- Schwengers, O.; Jelonek, L.; Dieckmann, M.A.; Beyvers, S.; Blom, J.; Goesmann, A. Bakta: Rapid and Standardized Annotation of Bacterial Genomes via Alignment-Free Sequence Identification. Microb. Genomics 2021, 7, 000685, doi:10.1099/mgen.0.000685.

- Levy Karin, E.; Mirdita, M.; Söding, J. MetaEuk—Sensitive, High-Throughput Gene Discovery, and Annotation for Large-Scale Eukaryotic Metagenomics. Microbiome 2020, 8, 48, doi:10.1186/s40168-020-00808-x.

- Feldgarden, M.; Brover, V.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Frye, J.G.; Haendiges, J.; Haft, D.H.; Hoffmann, M.; Pettengill, J.B.; Prasad, A.B.; Tillman, G.E.; et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog Facilitate Examination of the Genomic Links among Antimicrobial Resistance, Stress Response, and Virulence. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12728, doi:10.1038/s41598-021-91456-0.

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; García-Fernández, A.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Hasman, H. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids Using PlasmidFinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3895–3903, doi:10.1128/aac.02412-14.

- Pham, N.-P.; Layec, S.; Dugat-Bony, E.; Vidal, M.; Irlinger, F.; Monnet, C. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Brevibacterium Strains: Insights into Key Genetic Determinants Involved in Adaptation to the Cheese Habitat. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 955, doi:10.1186/s12864-017-4322-1.

- Quigley, L.; O’Sullivan, O.; Stanton, C.; Beresford, T.P.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Cotter, P.D. The Complex Microbiota of Raw Milk. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 664–698, doi:10.1111/1574-6976.12030.

- Niccum, B.A.; Kastman, E.K.; Kfoury, N.; Robbat, A.; Wolfe, B.E. Strain-Level Diversity Impacts Cheese Rind Microbiome Assembly and Function. mSystems 2020, 5, 10.1128/msystems.00149-20, doi:10.1128/msystems.00149-20.

- Kandasamy, S.; Park, W.S.; Yoo, J.; Yun, J.; Kang, H.B.; Seol, K.-H.; Oh, M.-H.; Ham, J.S. Characterisation of Fungal Contamination Sources for Use in Quality Management of Cheese Production Farms in Korea. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 1002–1011, doi:10.5713/ajas.19.0553.

- Anelli, P.; Haidukowski, M.; Epifani, F.; Cimmarusti, M.T.; Moretti, A.; Logrieco, A.; Susca, A. Fungal Mycobiota and Mycotoxin Risk for Traditional Artisan Italian Cave Cheese. Food Microbiol. 2019, 78, 62–72, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2018.09.014.

- Decontardi, S.; Soares, C.; Lima, N.; Battilani, P. Polyphasic Identification of Penicillia and Aspergilli Isolated from Italian Grana Cheese. Food Microbiol. 2018, 73, 137–149, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2018.01.012.

- Anast, J.M.; Dzieciol, M.; Schultz, D.L.; Wagner, M.; Mann, E.; Schmitz-Esser, S. Brevibacterium from Austrian Hard Cheese Harbor a Putative Histamine Catabolism Pathway and a Plasmid for Adaptation to the Cheese Environment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6164, doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42525-y.

- Gavrish, E.Yu.; Krauzova, V.I.; Potekhina, N.V.; Karasev, S.G.; Plotnikova, E.G.; Altyntseva, O.V.; Korosteleva, L.A.; Evtushenko, L.I. Three New Species of Brevibacteria, Brevibacterium Antiquum Sp. Nov., Brevibacterium Aurantiacum Sp. Nov., and Brevibacterium Permense Sp. Nov. Microbiology 2004, 73, 176–183, doi:10.1023/B:MICI.0000023986.52066.1e.

- Michel, V.; Martley, F.G. Streptococcus Thermophilus in Cheddar Cheese – Production and Fate of Galactose. J. Dairy Res. 2001, 68, 317–325, doi:10.1017/S0022029901004812.

- Lipoic Acid | Linus Pauling Institute | Oregon State University Available online: https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/dietary-factors/lipoic-acid (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Gorąca, A.; Huk-Kolega, H.; Piechota, A.; Kleniewska, P.; Ciejka, E.; Skibska, B. Lipoic Acid – Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential. Pharmacol. Rep. 2011, 63, 849–858, doi:10.1016/S1734-1140(11)70600-4.

- Stach, K.; Stach, W.; Augoff, K. Vitamin B6 in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3229, doi:10.3390/nu13093229.

- Sanvictores, T.; Chauhan, S. Vitamin B5 (Pantothenic Acid). In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing, 2024.

- Paul McSweeney; Patrick Fox; Paul Cotter; David Everett Cheese: Chemistry, Physics & Microbiology (Fourth Eidition); Academic Press, 2017;

- Muñoz-Tebar, N.; González-Navarro, E.J.; López-Díaz, T.M.; Santos, J.A.; Elguea-Culebras, G.O. de; García-Martínez, M.M.; Molina, A.; Carmona, M.; Berruga, M.I. Biological Activity of Extracts from Aromatic Plants as Control Agents against Spoilage Molds Isolated from Sheep Cheese. Foods 2021, 10, 1576, doi:10.3390/foods10071576.

- Finoli, C.; Vecchio, A.; Galli, A.; Franzetti, L. Production of Cyclopiazonic Acid by Molds Isolated from Taleggio Cheese. J. Food Prot. 1999, 62, 1198–1202, doi:10.4315/0362-028X-62.10.1198.

- Curtin, Á.C.; McSweeney, P.L.H. Catabolism of Amino Acids in Cheese during Ripening. In Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology; Fox, P.F., McSweeney, P.L.H., Cogan, T.M., Guinee, T.P., Eds.; General Aspects; Academic Press, 2004; Vol. 1, pp. 435–454.

- Pham, N.-P.; Layec, S.; Dugat-Bony, E.; Vidal, M.; Irlinger, F.; Monnet, C. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Brevibacterium Strains: Insights into Key Genetic Determinants Involved in Adaptation to the Cheese Habitat. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 955, doi:10.1186/s12864-017-4322-1.

- Hahn, M.B.; Meyer, S.; Schröter, M.-A.; Kunte, H.-J.; Solomun, T.; Sturm, H. DNA Protection by Ectoine from Ionizing Radiation: Molecular Mechanisms. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 25717–25722, doi:10.1039/C7CP02860A.

- Diana, M.; Rafecas, M.; Arco, C.; Quílez, J. Free Amino Acid Profile of Spanish Artisanal Cheeses: Importance of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Ornithine Content. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2014, 35, 94–100, doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2014.06.007.

- Kurata, K.; Nagasawa, M.; Tomonaga, S.; Aoki, M.; Morishita, K.; Denbow, D.M.; Furuse, M. Orally Administered L-Ornithine Elevates Brain l-Ornithine Levels and Has an Anxiolytic-like Effect in Mice. Nutr. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 243–248, doi:10.1179/1476830511Y.0000000018.

- Li, X.; Xiao, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, P. Uncovering de Novo Polyamine Biosynthesis in the Gut Microbiome and Its Alteration in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut Microbes 17, 2464225, doi:10.1080/19490976.2025.2464225.

- Herreros, M.A.; Sandoval, H.; González, L.; Castro, J.M.; Fresno, J.M.; Tornadijo, M.E. Antimicrobial Activity and Antibiotic Resistance of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Armada Cheese (a Spanish Goats’ Milk Cheese). Food Microbiol. 2005, 22, 455–459, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2004.11.007.

- Belletti, N.; Gatti, M.; Bottari, B.; Neviani, E.; Tabanelli, G.; Gardini, F. Antibiotic Resistance of Lactobacilli Isolated from Two Italian Hard Cheeses. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 2162–2169, doi:10.4315/0362-028X-72.10.2162.

- Jamet, E.; Akary, E.; Poisson, M.-A.; Chamba, J.-F.; Bertrand, X.; Serror, P. Prevalence and Characterization of Antibiotic Resistant Enterococcus Faecalis in French Cheeses. Food Microbiol. 2012, 31, 191–198, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2012.03.009.

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, A.; Li, S.; Tao, R.; Chen, K.; Huang, P.; Li, L.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; et al. Comparison of the Full-Length Sequence and Sub-Regions of 16S rRNA Gene for Skin Microbiome Profiling. mSystems 2024, 9, e00399-24, doi:10.1128/msystems.00399-24.

| Bin Taxonomy | Completeness | Contamination | N50 | L50 |

| Brachybacterium sp. P6-10-X1 | 100 | 2.5 | 120479 | 8 |

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99.31 | 1.06 | 50434 | 20 |

| Lactococcus lactis | 100 | 0.88 | 133251 | 6 |

| Staphylococcus simulans | 100 | 0.13 | 50608 | 14 |

| Levillactobacillus brevis | 100 | 0.36 | 52054 | 18 |

| Streptococcus thermophilus | 100 | 2.76 | 35987 | 15 |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 100 | 0.43 | 34786 | 15 |

| Corynebacterium glyciniphilum | 100 | 0.67 | 39133 | 26 |

| Staphylococcus equorum | 99.28 | 1.82 | 14552 | 52 |

| Mammaliicoccus lentus | 100 | 2.75 | 11713 | 65 |

| Leuconostoc falkenbergense | 100 | 0.12 | 53532 | 10 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 100 | 2.88 | 11855 | 59 |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii | 100 | 0.63 | 52959 | 9 |

| Brevibacterium aurantiacum | 99.83 | 19.28 | 14652 | 95 |

| Brevibacterium limosum | 100 | 2.52 | 24147 | 35 |

| Brevibacterium spongiae | 100 | 1.06 | 16330 | 43 |

| Scaffold taxonomy | Plasmid origin in contig | Gene | Resistance | Point mutation |

| Enterococcus faecium | - | aph(3’)-IIIa | Amikacin/Kanamycin | + |

| Enterococcus faecium | rep | eat(A)_T450I | Pleuromutilin | - |

| Enterococcus faecium Com15 | - | msr(C) | Azithromycin, Erythromycin, Streptogramin B, Tylosin | - |

| Enterococcus faecium Com15 | - | liaR_E75K | Daptomycin | + |

| Enterococcus faecium DO | - | aac(6’)-I | Aminoglycoside | - |

| Lactococcus formosensis | - | tet(S) | Tetracycline | - |

| Mammaliicoccus lentus | - | sal(B) | Lincosamide, Pleuromutilin, Streptogramin | - |

| Mammaliicoccus lentus | - | mph(C) | Erythromycin, Spiramycin, Telithromycin | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus | - | blaI | Beta-lactam | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus | - | blaR1 | Beta-lactam | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus | pS194 | str | Streptomycin | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus | pS0385p1 | tet(K) | Tetracycline | - |

| Staphylococcus equorum | - | mph(C) | Erythromycin, Spiramycin, Telithromycin | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).