1. Introduction

Hericium erinaceus, commonly known as lion’s mane, is a widely cultivated and highly popular gourmet and medicinal fungus, renowned for its diverse bioactive constituents that support a variety of positive health outcomes. In the functional mushroom industry,

H. erinaceus is primarily valued for its neuroprotective properties with numerous studies demonstrating its potential to support healthy brain function, promote neurogenesis, mitigate neurodegenerative diseases, and alleviate mood disorders [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Additionally, a wide variety of

H. erinaceus tissues, extracts, and components have demonstrated significant antioxidant activity, modulation of gut microbiota composition, and anticancer effect in both animal models and human clinical trials [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. While myriad health-supporting effects have been attributed to

H. erinaceus, a potentially undervalued benefit of

H. erinaceus mycelium in the supplement industry is its ability to support a healthy immune system.

Many families of bioactive molecules have been identified in

H. erinaceus, including erinacines, hericenones, hericenes, peptides, and polysaccharides such as β-glucans [

2,

6,

12,

13,

14]. Importantly, different

H. erinaceus tissues and developmental stages can produce distinct chemical profiles, with fruit bodies characterized by hericenones, and the mycelium uniquely producing erinacines [

14,

15,

16]. Previous studies

of H. erinaceus constituents have revealed differential biological activities, with erinacines (but not hericenones) consistently inducing nerve growth factor (NGF) expression in neuronal models [

2,

17]. Accordingly, this study investigated whether separate

H. erinaceus fractions also demonstrate divergent immune impacts.

After confirming the hypothesis that H. erinaceus mushroom mycelium in the form of an extracted Host Defense Lion’s Mane powder product (HDLM) would induce clear transcriptomic immune modulation in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), cytokine protein responses induced by this H. erinaceus fraction and a β-glucan-enriched fruit body extract product (FBE) were also investigated. Central inflammatory cytokine targets were screened to compare their engagement under both basal and inflammatory conditions, revealing that HDLM promotes a balanced immune response, demonstrating a unique efficacy in decreasing production of inflammatory interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) under LPS challenge. HDLM also exhibited significant antioxidant and iron chelating effects, as evaluated by antioxidant and ferrous iron chelating assays. In contrast, FBE was observed to increase inflammatory cytokine expression under challenge and displayed significantly lower levels of iron chelating activity across all concentrations tested, highlighting the divergent immunomodulatory and stress quenching effects of H. erinaceus fractions obtained from different tissue types and extraction methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

H. erinaceus mycelial samples were prepared by combining 50 g Host Defense Lion’s Mane powder (HDLM; H. erinaceus mushroom mycelium and fermented brown rice biomass; US-sourced) with 50 g 95% ethanol and 50 g ultrapure water. Samples were macerated at room temperature for 72 h and then centrifuged at 600 x g for 10 min until the supernatant could be decanted. This centrifugation step was repeated until the pellet was nearly dry. After maximum supernatant recovery, samples were passed through a 0.2 μm polypropylene filter, weighed, and then frozen at –80 °C. Samples were lyophilized to dryness, transferred to a new sterile tube, and stored at room temperature until reconstitution in water, DMSO, or PBS for assays.

For the IL-1β ELISA and ferrous iron chelating ability assay, a commercially available H. erinaceus fruit body powder product (FBE) derived from Chinese-sourced material was included to compare bioefficacy outcomes associated with different tissue types (and consequently different compound compositions). As purchased, the fruit body material had been prepared as a hot water extract and was resuspended in each assay’s appropriate solvent to preserve its advertised 30% β-glucan content. While enzymatic assay kits such as those from Megazyme are commonly used to quantify fungal β-glucans, these methods primarily distinguish β-1,3- and β-1,4-linked glucans and do not differentiate β-glucans derived from yeast and mushroom sources. Consequently, the exact size, composition, and relative percentage of fungal β-glucans in this sample could not be precisely quantified.

2.2. PBMC Culture for mRNA-Sequencing

PBMCs (ATCC, PCS-800-011) were removed from cryogenic storage, transferred to T75 flasks in RPMI 1640 (ATCC, 30-2001) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, F1051-100ML) that had been heat inactivated, incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h, then reseeded in 12-well plates. After a 24 h incubation, cells received their treatments along with additional media and were incubated for another 24 h. For harvest, plates were centrifuged at 80 x g for 6 min before media was aspirated to allow cells to be removed using a cell scraper and pipetted into sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes. Tubes were centrifuged at 2000 x g for 30 s, and cell media was again aspirated before cell pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C.

Before starting RNA extraction, surfaces and tools were cleaned with RNaseZap (ThermoFisher, AM9780). Using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, 74104), 350 µL of RLT buffer was added to each microcentrifuge tube after loosening the cell pellet by flicking, and cells were lysed by vortexing for 1 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube and the manufacturer’s recommended extraction procedure for mammalian cells was followed, including the optional step of placing columns into new collection tubes and centrifuging for 1 min at 13,000 x g immediately before elution. For elution, 30 µL of the provided RNase-free water was added to columns, which were incubated at room temperature for 1 min before proceeding. RNA quality (A260/280 ratios) and concentrations of samples were determined spectrophotometrically prior to DNase digestion.

To perform DNase digestions, 30 µL of eluted RNA was added to 3 µL of reaction buffer and 3 µL of DNase I (ThermoFisher, EN0521). Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before 3 µL of 50 mM EDTA was added, and then incubated at 65 °C for 10 min. All samples were stored at –80 °C and shipped to Novogene Corporation Inc. (Sacramento, California) on dry ice for mRNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq).

2.3. Cell Viability Testing

Prior to culturing PBMCs for RNA extraction, an MTT assay (ATCC, 30-1010K) was performed to optimize treatment concentration based on cell viability. A 384-well plate was used with n = 6 replicate wells per treatment concentration. The MTT assay was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s kit instructions, but with a decrease in volume from 110 μl reactions to 55 μl reactions to conduct the assay in a 384-well plate. Treated cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 4 h to most effectively solubilize the formazan dye. Absorbance readings were recorded at 570 and 660 nm, and finalized sample values were calculated by subtracting values at 660 nm from values at 570 nm before further subtracting the average value of the media blank control from all other samples. Percent cell viability was evaluated relative to the PBS vehicle control.

2.4. RNA-Seq and Analysis

Extracted samples only proceeded to sequencing if they had a total RNA quantity exceeding 100 ng and a spectrophotometric A260/280 ratio of 1.95 or above. Novogene’s mRNA-Seq service was used, which was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq X-Plus platform with a paired-end 150 bp read length. A minimum of 20 million read pairs per sample were generated and aligned to human reference genome Homo_sapiens_Ensemble_94. RNA-Seq data are summarized in

Supplementary Figure S1.

Novogene’s analytical platform, NovoMagic, was used to assess data quality and replicate-level variability via principal component analysis (PCA) and to generate differentially expressed gene (DEG) lists and dot plots summarizing KEGG and Reactome pathways. Novogene’s default DESeq2 analysis, applying the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction with an adjusted p-value (padj) cutoff of ≤0.05, was used to identify significant DEG and pathway results [

18]. RStudio 2024.12.0 (R 4.2.2) was used to create bar graphs, volcano plots, and heatmaps.

2.5. Cytokine Activity Assays

Cryopreserved standard human PBMCs (ATCC, PCS-800-011) were thawed, centrifuged, and washed with 37 °C RPMI 1640 media to remove any DMSO used for cryopreservation purposes. Cells were incubated in 15 mL of warmed RPMI 1640 (10% FBS) overnight in a T75 flask to recover from the freeze/thaw process. Viable cell counts were determined via hemocytometer after staining with 0.4% trypan blue diluted with 1X PBS. Following a 24 h growth phase within the T75 flask, cells were transferred to a 96-well plate at 2 × 10⁶ cells per well. Treatments were introduced approximately 24 h after seeding, incubated for 18-24 h post-treatment, then plates were centrifuged at 100 x g for 6 min. The media was aspirated and used for cytokine analysis via ELISA. Cytokine concentrations were quantified using commercially available ELISA kits for interleukin 8 (IL-8; R&D Systems, DY208-05), interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA; R&D Systems, DY280-05), IL-1β (BioLegend, 437004), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α; BioLegend, 430201), and interleukin 13 (IL-13; R&D Systems, DY213-05). All ELISAs were run according to manufacturers’ instructions. For IL-8 only, a PBS buffer was used in place of the specified TBS buffer; all other kits were run without buffer substitutions. All ELISAs used PBS as sample solvent and vehicle control except TNF-α, which was conducted as an initial dose response screen and used DMSO.

2.6. DPPH Assay

A 100 µg/mL DPPH reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, 300267) was prepared in 95% ethanol, providing a stock solution that was calibrated by mixing 60 µL of DPPH stock with 40 µL of sterile water. The resulting solution was added to a single well of a 384-well plate, read spectrophotometrically at 517 nm, and calibrated so absorbance fell between 1.0 and 1.1. Ascorbic acid was used as the positive control, sterile water was used as the blank, and DPPH reagent was included as a maximal signal control. All controls were loaded at 100 µL per well. HDLM treatment was serially diluted in sterile water before being added to a 384-well plate at a volume of 75 µL per well. The 384-well plate was read at 517 nm to evaluate background before adding 25 µL DPPH stock to each well and returning to the plate reader, where it was read at 517 nm every 5 min for 60 min, shaking between read points. Corrected absorbance values were obtained by subtracting the average background absorbance at 60 min from all other wells. Percent radical scavenging activity was calculated by subtracting sample absorbance from the maximal signal control, dividing by the maximal signal control, and multiplying by 100, where the maximal signal control was defined as the average absorbance of DPPH reagent alone at 60 min.

2.7. Evaluation of Ferrous Iron Chelating Ability

In a manner similar to [

19] and [

20], the ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) chelating activity of samples was assessed by measuring the reduction in color intensity resulting from inhibition of the purple ferrozine–Fe²⁺ complex. Sterile water was used for all dilutions of samples, components, blank control, and maximal signal control. A 2x EDTA serial dilution (100 µM-0.78 µM) was included to create a standard curve and express sample iron chelation ability in EDTA µM equivalents. In 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes, 900 µL of sterile water was added to 500 µL of sample, blank, or maximal signal control. 100 µL of 0.6 mM FeCl

2 (ThermoFisher, 389350250) was added to all samples and controls except the blank, which had 100 µL water added. Reaction tubes were vortexed vigorously, then incubated for 10 min at room temperature, with additional vortexing every 2 min. In the dark, 100 µL 5 mM ferrozine (ThermoFisher, AC410570010) was added to all reaction tubes, which were vortexed briefly before reactions were transferred to a 96-well plate, 200 µL per replicate well. The plate was incubated for 10 min at room temperature in the dark, and absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 562 nm.

To determine the ferrous iron chelating percentage of samples and subsequently the EDTA µM equivalent, the average blank absorbance value was subtracted from all other sample and control values. The ferrous iron chelating percentage of samples was calculated by subtracting the sample absorbance value from the average maximal signal control value, dividing by average maximal signal control value, and multiplying by 100. An EDTA standard curve was constructed by plotting EDTA control concentrations against the corresponding ferrous iron chelating percentages, and this standard curve equation was used to determine average EDTA µM equivalents for each sample.

3. Results

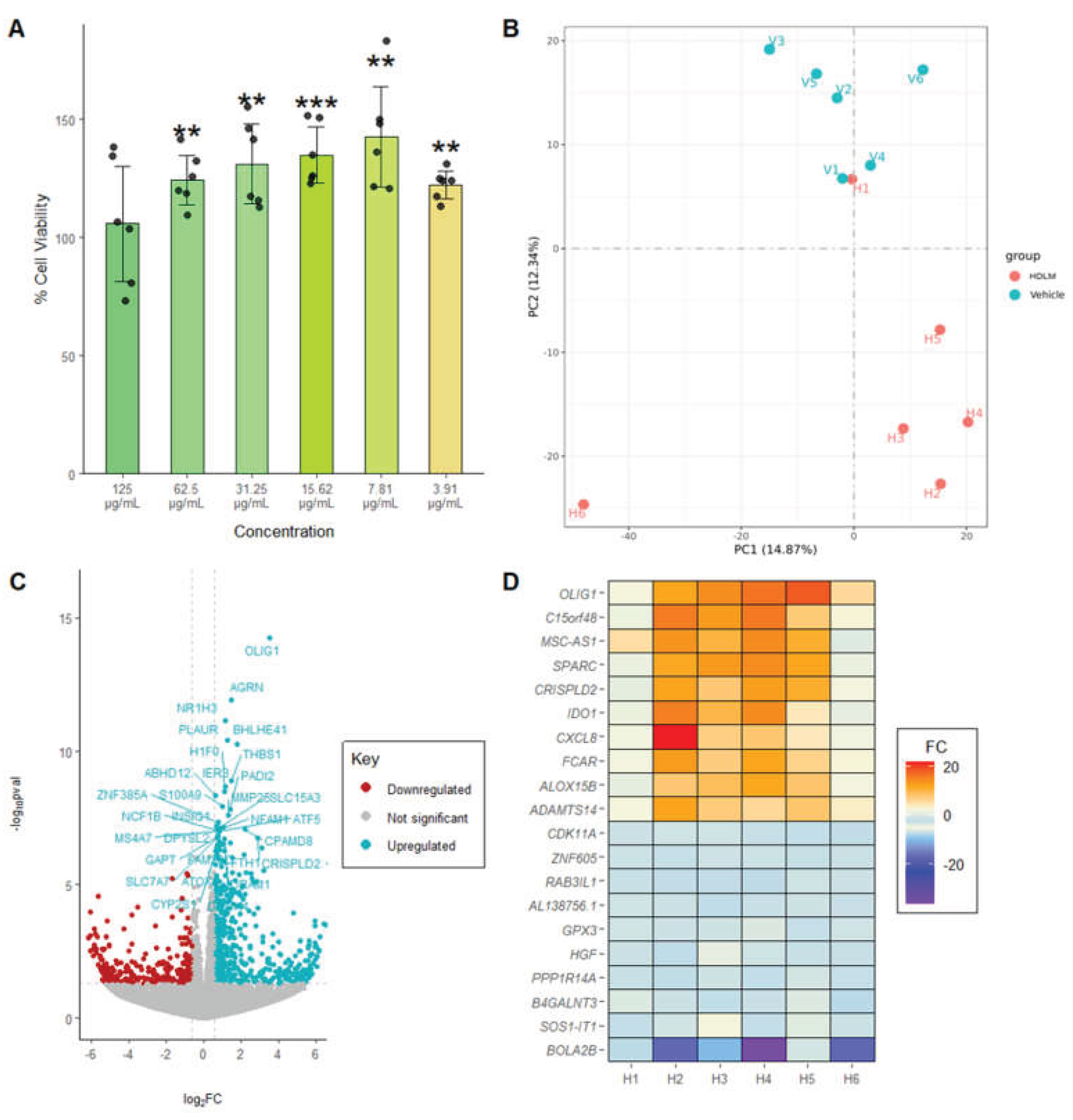

3.1. Cell Culture Optimization and Cell Viability Testing

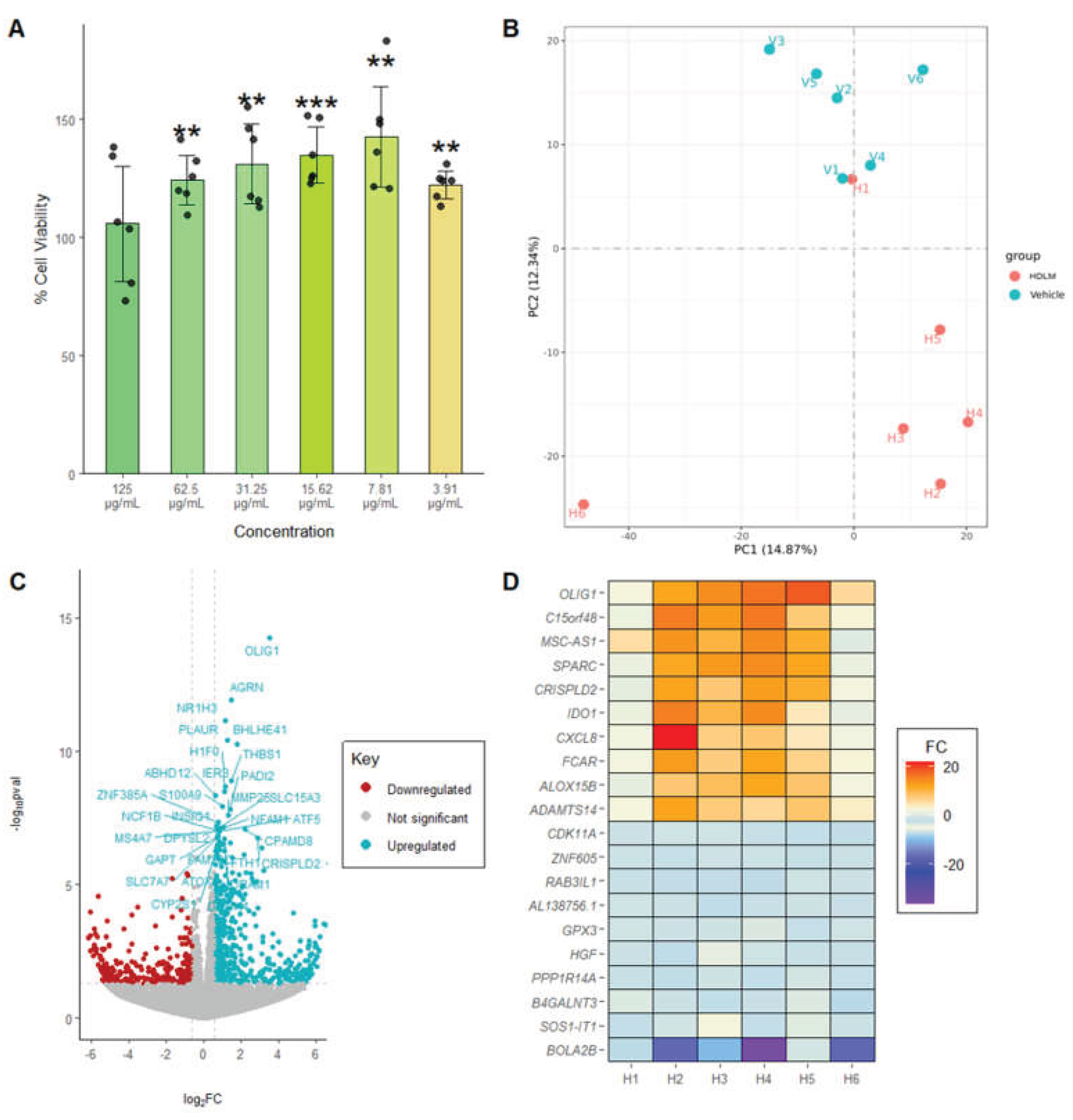

To optimize treatment concentration, an MTT assay was first performed to evaluate cell viability across a dilution series of HDLM (solubilized in PBS) ranging from 125 µg/mL to 3.9 µg/mL. Notably, four treatment concentrations produced responses exceeding those of the vehicle control, suggesting that HDLM may enhance cellular metabolic activity or viability (

Figure 1A). Based on the results, a concentration of 62.5 µg/mL was selected as the RNA-Seq HDLM treatment concentration to balance a high treatment concentration with cell viability exceeding 100%.

3.2. Transcriptomic Impact of HDLM on Human PBMCs

PCA was performed on RNA-Seq data to visualize global gene expression patterns, and results revealed that HDLM and Vehicle samples generally cluster separately, demonstrating the distinctly altered gene expression profile of PBMCs treated with HDLM when compared to the vehicle control (

Figure 1B). Specifically, the HDLM-treated replicates predominantly clustered in quadrant IV, while the vehicle replicates tended to cluster at the interface between quadrants I and II. PC1 and PC2 accounted for 14.87% and 12.34% of the variance respectively.

When comparing the expression profiles of HDLM- and vehicle-treated PBMCs, a pronounced shift in gene expression was observed, with 339 genes significantly upregulated and 39 significantly downregulated, demonstrating broad transcriptional activation elicited by HDLM treatment (DESeq2 analysis, padj<0.05;

Figure 1C). The most statistically significant results included agrin (

AGRN; padj<8.28 × 10

-9), nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 3 (

NR1H3; padj<3.30 × 10

⁻8), plasminogen activator urokinase receptor (

PLAUR; padj<1.37 × 10

⁻7), and basic helix-loop-helix family member e41 (

BHLHE41/

DEC2; padj<1.57 × 10

⁻7). Among the most robustly upregulated transcripts were modulator of cytochrome C oxidase during inflammation (

MOCCI/

C15orf48; fold change (FC) = 9.28), interleukin 8 (

CXCL8/

IL-8; FC = 7.24), and Fc fragment of IgA receptor (

FCAR; FC = 7.04;

Figure 1D). Additionally, the most downregulated transcripts included bolA family member 2B (

BOLA2B; FC = -11.45), SOS1 intronic transcript 1 (

SOS1-IT1; FC = -3.19), and beta-1,4-N-acetyl-galactosaminyltransferase 3 (

B4GALNT3; FC = -3.14;

Figure 1D).

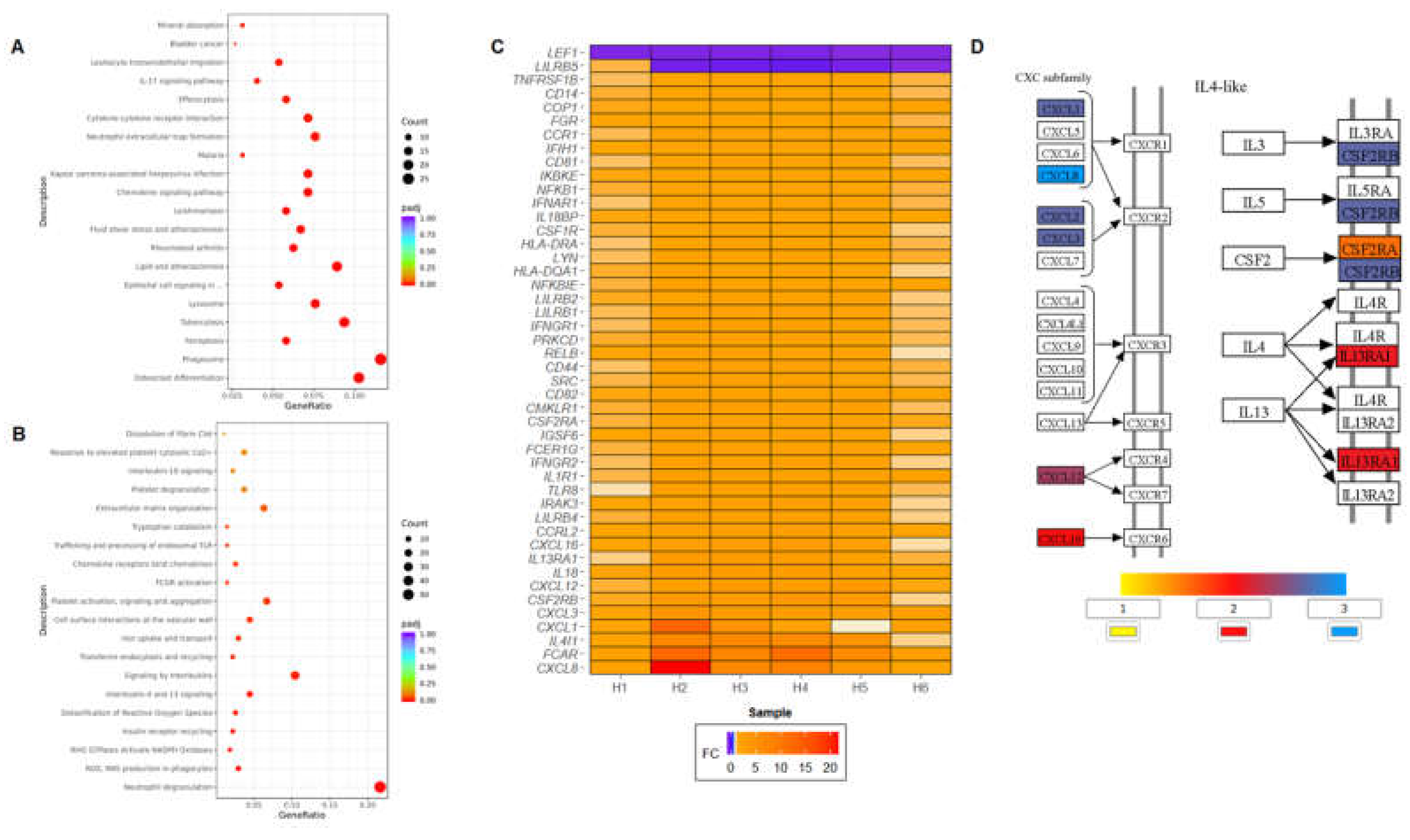

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs revealed several significantly enriched pathways (padj<0.05), including immune-related and stress signaling pathways such as osteoclast differentiation, phagosome, ferroptosis, cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, chemokine signaling, IL-17 signaling, T helper 17 (Th17) cell differentiation, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling, toll-like receptor (TLR), C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway, and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like (NOD-like) receptor pathways (

Figure 2A). Additional enriched pathways included those associated with infectious diseases (e.g., malaria, tuberculosis, leishmaniasis, and Legionellosis), autoimmune conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and systemic lupus-related signaling), and virus-associated immune responses (e.g., Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection, and viral protein interactions with cytokine receptors).

The significantly enriched Reactome pathways fell into several functional categories. Innate immune activation pathways included neutrophil degranulation, Fc gamma receptor (FCGR) activation, chemokine receptors binding chemokines, and trafficking and processing of endosomal TLRs (

Figure 2B). Pathways related to oxidative stress and antimicrobial activity featured prominently, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) production in phagocytes, RHO GTPase activation of NADPH oxidases, and detoxification of ROS. Cytokine signaling was also strongly represented, with enrichment in IL-4 and IL-13 signaling and broader interleukin signaling pathways, corresponding to a mild but significant induction in IL-13 protein after HDLM treatment (

Supplementary Figure S2). Iron metabolism and cellular transport pathways such as transferrin endocytosis and recycling and iron uptake and transport were also enriched.

Overall, immune-related cellular processes were the most highly represented among enriched pathways. Specifically, notable transcript responses included cytokine-related candidates (e.g.,

CXCL8/IL-8, IL4I1, IL18, IL18BP, IL13RA1, and

IL1R1), several CXC-motif chemokine ligands (e.g.,

CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL12, and

CXCL16), interferon receptors (e.g.,

IFNAR1, IFNGR1, and

IFNGR2), and immune cell surface receptors (e.g.,

CD14, CD44,

CD81, and

CD82).

Figure 2C summarizes important immune-related DEGs identified in PBMCs treated with HDLM, with a more comprehensive list included in

Supplementary Figure S3.

Figure 2D shows FC values for the two portions of the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction KEGG pathway most affected by HDLM: IL-4-like and CXC cytokines. The IL-4-like section of the pathway was especially engaged, with nearly half of the downstream targets upregulated following HDLM treatment.

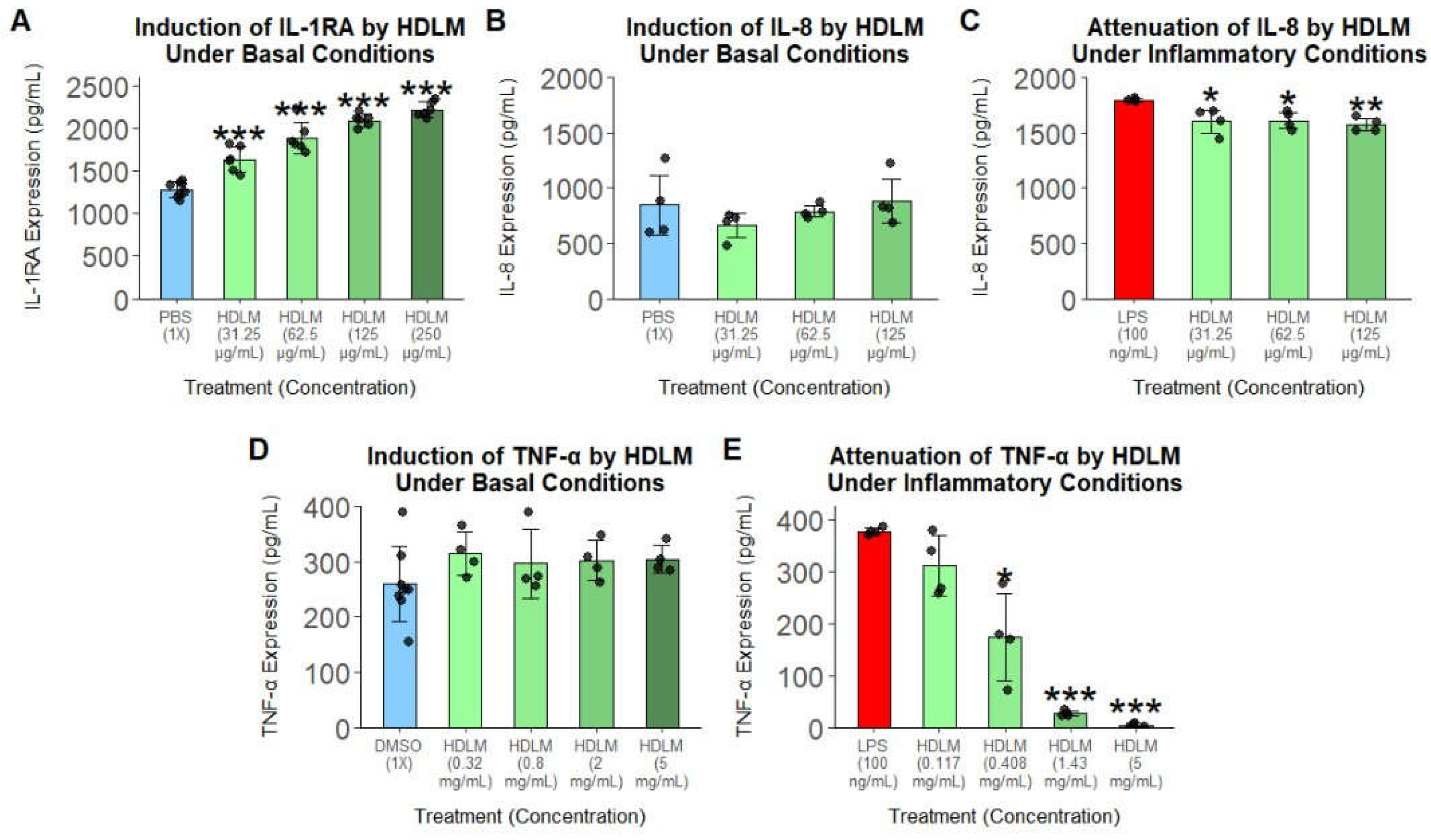

3.3. Cytokine Modulation Under Basal and Inflammatory Conditions

To further support the immunomodulatory effects of HDLM identified by transcriptomic analysis, cytokine ELISA assays were performed under baseline and LPS-induced inflammatory conditions. Under basal conditions, treatment with HDLM elicited a statistically significant, dose-dependent increase in IL-1RA, while the expression of IL-8 and TNF-α remained unchanged (

Figure 3A, 3B, 3D). Under inflammatory conditions, HDLM significantly decreased IL-8 expression and markedly suppressed TNF-α, with the highest treatment concentration almost completely silencing this immune response (

Figure 3C, 3E).

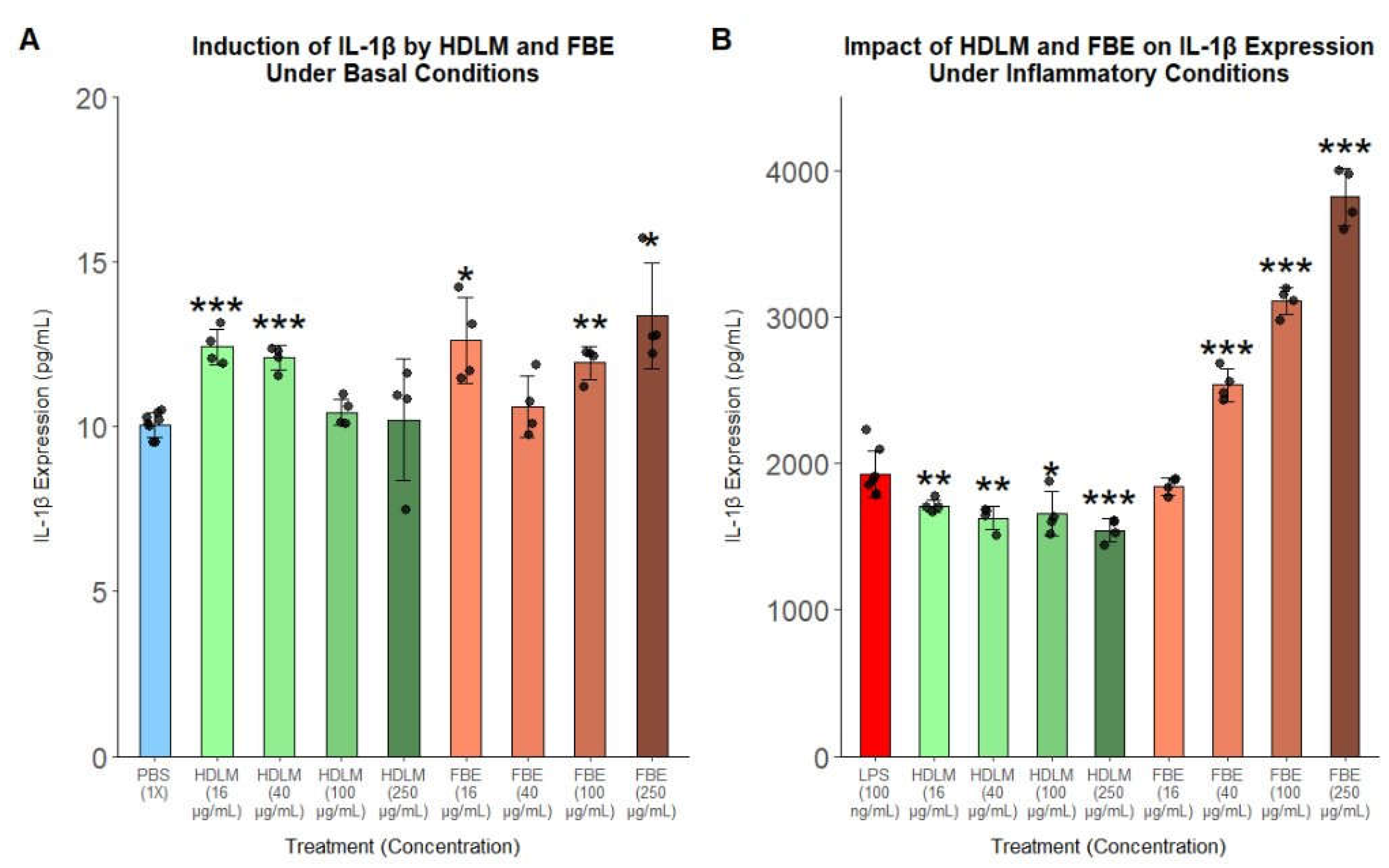

Given the global immune-modulating effects of HDLM observed in transcriptomic analyses alongside these notable protein responses, FBE was included in the IL-1β ELISA for direct comparison to explore how tissue type and chemical composition may influence the immunomodulatory effects of

H. erinaceus treatment. Under basal conditions, both HDLM and FBE supported statistically detectable but low-magnitude changes in IL-1β expression without clear dose-response relationships, suggesting slight immune priming or limited immune activation (

Figure 4A). However, under inflammatory conditions, HDLM significantly decreased IL-1β expression, while FBE potently and dose-dependently induced IL-1β expression, with the top concentration more than doubling IL-1β expression compared to the LPS control (

Figure 4B).

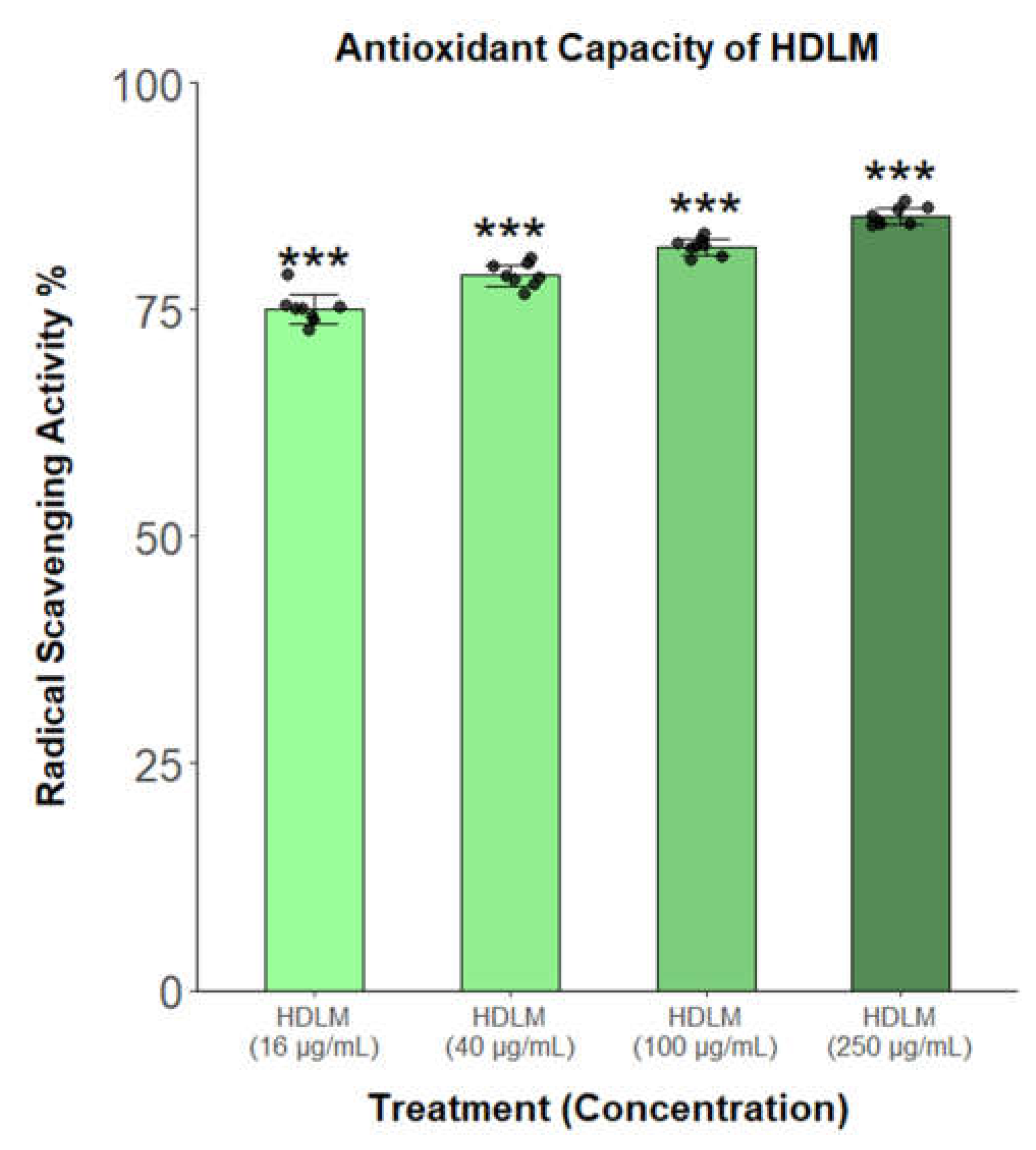

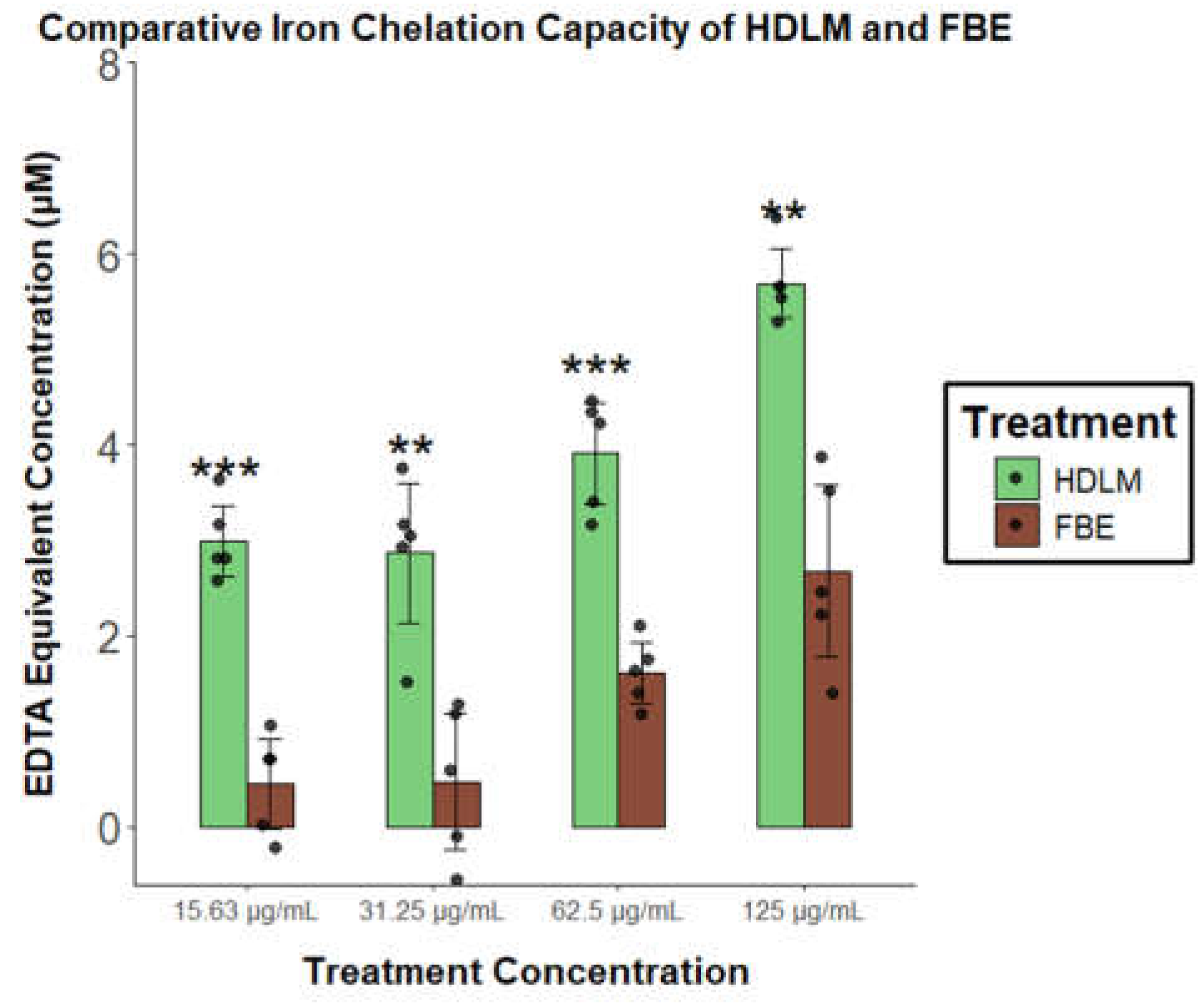

3.4. Antioxidant Capacity of HDLM and FBE

Due to the abundance of antioxidant and iron metabolism KEGG and Reactome hits identified after HDLM treatment, the antioxidant activity of this extract was assessed via DPPH and ferrous iron chelating assays. The DPPH assay revealed that HDLM displays significant and dose-responsive radical scavenging activity, exceeding 75% of the maximal control across all tested concentrations (p<0.001;

Figure 5). Although antioxidant activity of this fungus is well-established, RNA-Seq identified a more novel iron metabolism signal for HDLM, prompting comparison with FBE to determine whether this response is more strongly associated with either extract. HDLM displayed statistically significantly greater iron chelation activity than FBE at each tested concentration, with fold differences of over 6-fold at the lowest concentration and over 2-fold at the highest, demonstrating consistently stronger iron chelation across all doses (p < 0.01;

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

4.1. HDLM-Elicited Activation and Pacification of Immune Responses

Treatment with HDLM in healthy human immune cells consistently elicited balanced modulation of the immune system, especially the innate immune response. A total of 152 broadly immune-related differentially expressed transcripts were identified, all but 12 of which were found to be upregulated (

Supplementary Figure S3). Significant (padj<0.05) pathway enrichments related to immune regulatory signaling were revealed, and protein-level evidence also indicated context-dependent modulation of the immune response with distinct patterns of engagement depending on presence or absence of LPS-induced inflammation, suggesting a balancing of the challenged immune system. Enriched pathways related to innate immunity include phagosome, lysosome, neutrophil extracellular trap formation, leukocyte transendothelial migration, neutrophil degranulation, and several pattern recognition receptor systems. Neutrophils are generally absent from PBMCs, but are activated by cytokines such as

CXCL8/

IL-8 (FC = 7.24), as well as by specific types and concentrations of ROS and RNS [

21]. Neutrophils and other immune effectors such as macrophages produce ROS and RNS in large amounts to destroy pathogens, but in more specific doses, they act as signaling molecules to activate and regulate these cells [

22]. Cytokine and ROS/RNS signaling likely underlies these neutrophil-related observations, given the significant enrichment of Reactome pathways involved with the production and detoxification of ROS/RNS, including ROS, RNS production in phagocytes, RHO GTPases activate NADPH oxidases, and detoxification of ROS.

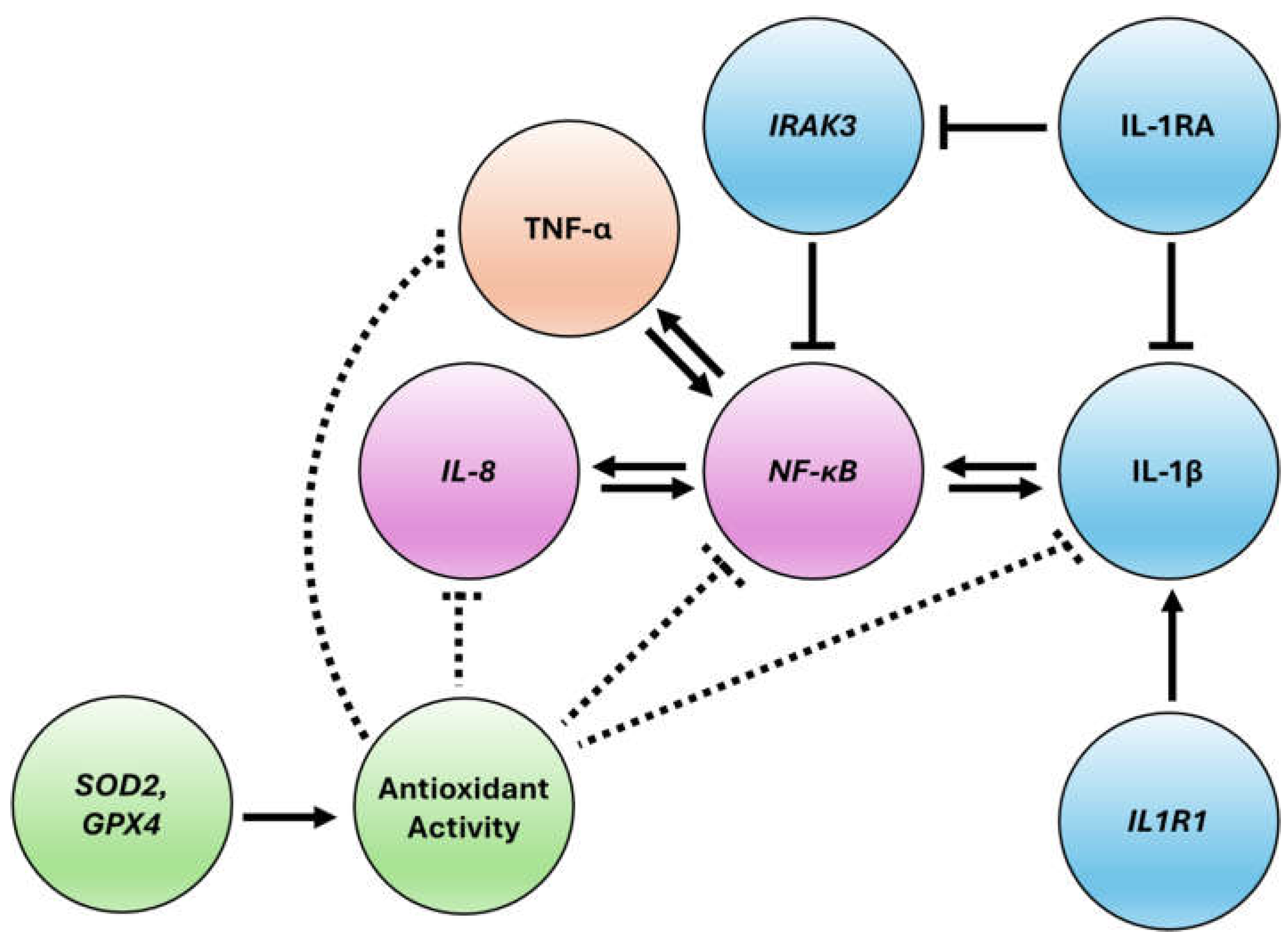

The innate immune transcript activation following HDLM treatment is balanced by induction of anti-inflammatory proteins, such as IL-1RA, paired with minimal engagement of classic inflammatory signals, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8. ELISA results revealed that HDLM did not induce significant amounts of TNF-α or IL-8 protein under basal conditions and significantly decreased expression of both targets under inflammatory conditions (

Figure 3). While

IL-8 transcript was notably upregulated under basal conditions, protein levels remained unchanged. Due to its powerful immune-engaging properties, expression of IL-8 protein is heavily pre- and post-transcriptionally regulated to fine tune immune responses and requires the presence of other inflammatory signals for maximum expression [

23,

24]. This dynamic suggests HDLM may prime human immune cells, enhancing immune readiness without triggering production of pro-inflammatory protein until necessary, a response that has also been noted for other immune effectors [

25,

26].

Similarly, while some concentrations of HDLM mildly increased expression of IL-1β protein under basal conditions, these increases were <5 pg/mL, and mycelium produced far larger and more significant decreases in IL-1β under inflammatory conditions (

Figure 4). This effect may in part reflect the observed increase in interleukin 1 receptor type 1 (

IL1R1, FC = 1.75) transcript after HDLM treatment, as

IL1R1 is a receptor of IL-1α and IL-1β, and an increase in protein can lead to greater engagement of inflammatory signaling molecules [

27]. The robust induction of IL-1RA, which acts as an IL-1 receptor antagonist to competitively prevent IL-1β from engaging its receptor, likely accounts for the low IL-1β protein levels observed under basal conditions [

28]. Additionally, IL-1RA is known to suppress IL-8 expression and could also contribute to the lack of IL-8 protein induction observed under basal conditions [

29]. Interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase 3 (

IRAK3, FC = 1.81) may further contribute to this dynamic, as it is known to dampen the effects of both IL-1 and NF-κB axes [

30,

31].

C-type lectin domain containing 7A (

CLEC7A, FC = 1.44), encoding dectin-1, was modestly upregulated. Dectin-1 recognizes fungal β-glucans to engage the canonical NF-κB pathway, influencing downstream pathways such as Th17 differentiation and IL-17-mediated neutrophil recruitment [

32]. Th17 differentiation is tightly regulated as overactivation can lead to pathogenic inflammation; interferon beta (IFNβ) signaling through the protein encoded by interferon alpha and beta subunit 1 (

IFNAR1, FC = 1.35), prompted by engagement of dectin-1, may help temper Th17 response and IL-1β expression [

33,

34]. This modulatory dynamic is supported by the lack of IL-1β protein induced by HDLM treatment under basal conditions alongside the engagement of additional anti-inflammatory effectors such as sialic acid binding Ig like lectin 10 (

SIGLEC10, FC = 4.17), which acts as an inhibitory receptor to selectively suppress immune responses to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and C-type lectin domain family 4 member E (

CLEC4E/Mincle, FC = 5.75), a strong anti-inflammatory signal that promotes differentiation of T helper 2 (Th2) cells and suppression of inflammatory T helper 1 (Th1) cells [

35,

36,

37]. Additionally, strong upregulation of interleukin 4-induced gene 1 (

IL4I1; FC = 4.37) and significant enrichment of interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling suggests activation of IL-4 pathways; IL-4 is part of the core positive feedback loop for anti-inflammatory Th2 cell differentiation, as it is both produced by and regulates these cells [

38,

39]. While excessive Th2 induction may be undesirable during pathogen challenge, under basal conditions it reflects a clear dampening of inflammatory signaling. This coordinated upregulation of both immune engaging and immune pacifying targets may provide insight into HDLM’s mechanism of action.

4.2. NF-κB Signaling and Adaptive Immune Responses

Consistent with other key immunoregulatory axes, a balanced modulation of the NF-κB pathway following HDLM treatment was observed. Two NF-κB subunit transcripts,

NFKB1 (of the canonical NF-κB pathway) and

RELB (of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway), were expressed at similar levels alongside a variety of NF-κB inhibitors, suggesting a finely tuned activation of this pathway that avoids inflammatory over-engagement. Previous studies have demonstrated that NF-κB activation can occur alongside the stimulation of NF-κB suppressors, providing a tightly regulated response that can prompt either specific immune engagement or general anti-inflammatory action [

40,

41]. Canonical NF-κB pathway activity following HDLM treatment is expected due to the upregulation of

IL-8 and

IL1R1 transcripts alongside inhibitor of NF-κB kinase subunit epsilon (

IKBKE, FC = 1.34) and

NFKB1 (FC = 1.35) [

42]. IL-8 production is driven by the canonical NF-κB pathway, and in turn, reinforces canonical NF-κB activation in a positive feedback loop. Similarly, an increase in IL1R1 also enhances activation of the canonical pathway, promoting the generation of downstream immune effectors [

23,

43,

44,

45]. However, the anti-inflammatory protein results previously discussed, including the lack of IL-8 induction under inflammatory conditions, indicate that activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway occurs in concert with counterbalancing anti-inflammatory signals [

46]. The gently upregulated NF-κB inhibitor epsilon (

NFKBIE, FC = 1.47) is a cytoplasmic NF-κB inhibitor, and glutathione peroxidase (

GPX4, FC = 1.33), through its involvement with antioxidant pathways, is also known to inhibit NF-κB signaling [

47]. Additionally, there are clear signs of noncanonical NF-κB pathway activation, which contributes to the regulation of diverse immune functions including antiviral innate immunity, dendritic cell antigen processing and presentation to T cells, and B cell activation [

48,

49,

50]. TNF receptor superfamily member 1B (

TNFRSF1B, FC = 1.21), a noncanonical NF-κB activator, and

RELB (FC = 1.53), a core noncanonical NF-κB subunit, are both upregulated following HDLM treatment [

46].

This treatment also appears to support antiviral activity through pathways besides innate immune activation. There is significant pathway enrichment for Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection, viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptors, and a variety of pathway-level hits related to adaptive immunity, including B cell receptor signaling pathway, Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, and FCGR activation. Notably, HDLM treatment also significantly upregulated

TLR8 (FC = 1.78) transcript, consistent with an enriched endosomal TLR trafficking and processing pathway. The TLR system is central to regulation of antiviral and immune engaging responses through its induction of IFN-β and other NF-κB-dependent cytokines [

51]. HDLM induced expression of transcripts for both components of the interferon-gamma receptor,

IFNGR1 (FC = 1.52) and

IFNGR2 (FC = 1.67) alongside stimulation of

IFNAR1 (FC = 1.35) [

52].

IL-18 (FC = 2.28), originally named interferon-gamma inducing factor, is also known to drive IFN activity [

53,

54,

55]. The immune-activating antiviral factors expressed following HDLM treatment were paired with immune-pacifying signals, such as interleukin 18 binding protein (

IL18BP, FC = 1.37), the key anti-inflammatory effector that works to ameliorate the effects of IL-18, and DNAJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C5 beta (

DNAJC5B, FC = 2.76), which codes for a protein that has also demonstrated antiviral effect towards hepatitis C in vitro [

43,

56,

57,

58]. Overall, these results emphasize the ability of HDLM treatment to induce production of crucial antiviral effectors, including interferons, while simultaneously promoting anti-inflammatory mediators to maintain a balanced immune defense (

Figure 7).

4.3. Inflammatory Response Triggered by FBE

The balanced response mediated in human PBMCs by HDLM does not seem to be replicated by FBE. While FBE provided only minor increases in IL-1β under basal conditions, under inflammatory conditions it induced significant, dose-dependent production of IL-1β, seemingly augmenting the inflammatory effects of LPS. It is possible that fungal β-glucan’s known immunostimulatory effect is over-engaged in PBMCs by this sample due to its particularly enriched β-glucan content, leading to greater expression of ROS and inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β [

59,

60,

61]. While production of pro-inflammatory cytokines is an important response to microbial invasion, overproduction of cytokines in an already stressed cellular environment is not desirable and can lead to development of autoimmune conditions over time [

62,

63]. Accordingly, these findings provide further preclinical evidence supporting caution when using fruit body extracts to treat infected immune cells, as the pronounced IL-1β overproduction and broader pro-inflammatory response may contribute to immune dysregulation and cytokine storm, and exacerbate inflammasome-mediated IL-1β signaling, potentially adversely affecting multiple organ systems [

64,

65,

66]. Moreover, isolated fungal β-glucans have demonstrated the ability to increase expression of multiple TLR and lectin transcripts, decrease expression of key antioxidant enzyme transcripts, and enhance ROS production in human PBMCs [

67].

Fungal β-glucans and their engagement of dectin-1 may support trained immunity, which enhances the ability of innate immune cells to mount stronger responses upon repeat exposure [

33,

68,

69]. However, despite the attention which fungal β-glucans have historically garnered for this purpose, β-glucans themselves may not be the primary immune-engaging constituent, but rather additional molecules residing within the β-glucan matrix [

70]. For example, polysaccharide-K (PSK) is a polysaccharide β-glucan fraction from

Trametes versicolor mycelium with demonstrated anticancer effects; however, the TLR2 agonist responsible for PSK’s ability to stimulate dendritic and T cells was identified as a structurally distinct lipid within this fraction [

71,

72]. In another study,

T. versicolor mycelium enhanced early activation of human monocytes and lymphocytes in vitro, while its fermented substrate induced larger, dose-dependent increases in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines [

73]. Accordingly, the fermented substrate component of HDLM may contribute to the immunomodulatory balance observed in our study, which was distinct from the pro-inflammatory response seen with FBE.

Given the differential protein-level effects observed for HDLM compared to FBE, the pronounced pro-inflammatory activity associated with FBE seemingly reflects β-glucan-driven dysregulation of the immune system leading to overactivation, whereas the response to mycelium suggests the presence of additional bioactive compounds that temper inflammatory signaling. Interestingly, as observed with PSK, β-glucans can also elicit beneficial immune responses, highlighting the importance of analytical methods capable of reliably quantifying and characterizing β-glucans by size, structure, and fungal species origin, as functional testing is beginning to reveal the disparate impacts of various β-glucan fractions. Furthermore, this dynamic demonstrates the need for caution, as the fungal supplement industry's focus on increasingly prominent biomarker claims may be outpacing rigorous safety testing and functional assays.

4.4. Stress Quenching Abilities of HDLM and FBE

Ferroptosis, one of the top KEGG results, is a type of cell death driven by excess levels of iron leading to lipid peroxidation, which initially manifests in the shrinkage and rupture of mitochondria [

74]. Although HDLM treatment of PBMCs enriches iron metabolism-related Reactome pathways (

Figure 2B), ferroptosis does not appear to be activated. Rather, gene regulation trends and accompanying in vitro antioxidant activity suggest this is more likely the result of gene products differentially regulated by HDLM treatment. Because ferroptosis operates through a ROS-based mechanism, antioxidant activity can rescue cells from ferroptosis or prevent it entirely by quenching oxidative stress. A wide variety of

H. erinaceus fractions and tissue types possess well-established antioxidant activity, and HDLM demonstrated significant radical scavenging activity and ferrous iron chelating potential alongside Reactome enrichment for ROS/RNS production in phagocytes, RHO GTPases activate NADPH oxidases, and detoxification of ROS (

Figure 2A and B) [

6,

75]. Even at twice the treatment concentration used for RNA-Seq, HDLM did not significantly decrease cell viability compared to the vehicle control, making ferroptosis unlikely (

Figure 1A).

Antioxidant activity also appears on the level of individual gene products. Superoxide dismutase 2 (

SOD2, FC = 3.76), the central mitochondrial superoxide dismutase, is essential for cellular defense against ROS created by the electron transport chain during cellular respiration [

76]. Beyond the mitochondria, HDLM treatment also influences glutathione peroxidases;

C15orf48/MOCCI (FC = 9.28), which promotes antioxidant activity by increasing glutathione production, is strongly upregulated alongside expression of

GPX4 (FC = 1.33), a negative regulator of ferroptosis [

75,

77]. FAM20C, a Golgi-associated secretory pathway kinase (

FAM20C; FC = 1.70) phosphorylates endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase 1 alpha, ERO1A, prior to localization to enhance its activity and facilitate maintenance of redox homeostasis [

78]. Several components of the standard cellular iron recycling pathway are upregulated, including cytochrome B561 family member A3 (

CYB561A3, FC = 2.25), which is also particularly highly expressed on monocytes and B lymphocytes, and

STEAP3 (FC = 4.68), a metalloreductase that targets both iron and copper [

79,

80]. Furthermore, antioxidant 1 copper chaperone (

ATOX1, FC = 1.94) facilitates copper transport and has been shown to protect cells by regulating antioxidant activity and DNA repair [

81,

82]. This variety of antioxidant enzymes targeting various ROS in multiple cellular locations provides strong mechanistic support for the prominent antioxidant capacity observed for HDLM. Additionally, the significantly greater ferrous iron chelating ability of HDLM compared to FBE highlights the increased stress quenching potential of mycelium. Overall, HDLM demonstrated stress quenching through antioxidant activity coupled with targeted immune pacification, likely contributing to its established anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects.

5. Conclusions

Overall, HDLM promotes a balanced and adaptable immune response, primed for potential cellular challenges while avoiding excessive activation. Strikingly, while HDLM provides a modest upregulation of many immune activation targets, particularly at the transcript level, this research indicates that mild protein activation under healthy conditions is coupled with an ability to pacify the immune system under cellular stress, reducing the levels of several key inflammatory biomarkers. Beyond its immune balancing and modulating effects, HDLM provided consistent antioxidant activity as transcriptomic leads were confirmed by in vitro antioxidant tests, suggesting that this treatment may calm cellular stress through distinct yet complementary mechanisms. Interestingly, when compared to FBE, HDLM provided stronger iron chelation activity. Additionally, FBE did not provide the same immune-modulating balance observed with HDLM, instead eliciting an approximately two-fold increase in the IL-1β-associated stress response. These findings have broader implications for the wellness and supplement industry, as different fungal tissue types and extraction methods can elicit biological responses of varying magnitudes and even opposing outcomes. While further clinical substantiation is needed to draw firmer conclusions, the current work provides clear evidence that HDLM elicits immunomodulatory and stress-quenching effects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Complete DEG list with unfiltered mRNA-Seq results comparing the transcriptomic profiles of human PBMCs treated with HDLM compared to Vehicle; Figure S2: Induction of IL-13 by HDLM in PBMCs; Figure S3: Immune-related DEGs elicited by HDLM treatment in PBMCs relative to Vehicle.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B. and E.D.; Methodology, C.B., E.D., and J.K.; Software, Z.B. and E.D.; Validation, E.D. and J.K.; Formal Analysis, E.D.; Investigation, J.K and E.D.; Data Curation, E.D. and J.K.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, E.D. and C.B.; Writing – Review & Editing, E.D., C.B., J.K., and Z.B.; Visualization, E.D., Z.B. and C.B.; Supervision, C.B.; Project Administration, C.B. and E.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data from differential gene expression analysis is provided in

Supplementary Figure S1. All data are available upon reasonable request to chase.b@fungi.com.

Acknowledgments

We extend our appreciation to Regan Nally, Kyle Meyer, Jacqueline Morgado, and Patrick Bennett for their valuable insight and support, and gratefully acknowledge Paul Stamets for his support and vision, which was essential for the realization of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors are employed by Fungi Perfecti, LLC, a producer of fungal dietary supplements, including the Host Defense Lion’s Mane mushroom mycelium product evaluated in this study.

References

- Li, I.-C.; Chang, H.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Chen, W.-P.; Lu, T.-H.; Lee, L.-Y.; Chen, Y.-W.; Chen, Y.-P.; Chen, C.-C.; Lin, D.P.-C. Prevention of Early Alzheimer’s Disease by Erinacine A-Enriched Hericium erinaceus Mycelia Pilot Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Front Aging Neurosci 2020, 12, 155. [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Obara, Y.; Hirota, M.; Azumi, Y.; Kinugasa, S.; Inatomi, S.; Nakahata, N. Nerve Growth Factor-Inducing Activity of Hericium erinaceus in 1321N1 Human Astrocytoma Cells. Biol Pharm Bull 2008, 31, 1727–1732. [CrossRef]

- Ornish, D.; Madison, C.; Kivipelto, M.; Kemp, C.; McCulloch, C.E.; Galasko, D.; Artz, J.; Rentz, D.; Lin, J.; Norman, K.; et al. Effects of Intensive Lifestyle Changes on the Progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment or Early Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Alz Res Therapy 2024, 16, 122. [CrossRef]

- Vigna, L.; Morelli, F.; Agnelli, G.M.; Napolitano, F.; Ratto, D.; Occhinegro, A.; Di Iorio, C.; Savino, E.; Girometta, C.; Brandalise, F.; et al. Hericium erinaceus Improves Mood and Sleep Disorders in Patients Affected by Overweight or Obesity: Could Circulating pro-BDNF and BDNF Be Potential Biomarkers? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2019, 2019, 7861297. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.C.; Yang, H.-L.; Pan, J.-H.; Korivi, M.; Pan, J.-Y.; Hsieh, M.-C.; Chao, P.-M.; Huang, P.-J.; Tsai, C.-T.; Hseu, Y.-C. Hericium erinaceus Inhibits TNF-α-Induced Angiogenesis and ROS Generation through Suppression of MMP-9/NF-κB Signaling and Activation of Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant Genes in Human EA.Hy926 Endothelial Cells. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2016, 2016, 8257238. [CrossRef]

- Contato, A.G.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Lion’s Mane Mushroom (Hericium erinaceus): A Neuroprotective Fungus with Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antimicrobial Potential—a Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1307. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, M.; Xiao, X.; Gao, M.; Gao, Q.; Xu, D. Molecular Properties, Structure, and Antioxidant Activities of the Oligosaccharide Hep-2 Isolated from Cultured Mycelium of Hericium erinaceus. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2019, 43, e12985. [CrossRef]

- Kushairi, N.; Phan, C.W.; Sabaratnam, V.; David, P.; Naidu, M. Lion’s Mane Mushroom, Hericium erinaceus (Bull.: Fr.) Pers. Suppresses H2O2-Induced Oxidative Damage and LPS-Induced Inflammation in HT22 Hippocampal Neurons and BV2 Microglia. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8, 261. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Xu, D.; Gao, Y.; Gao, Q. A Polysaccharide Isolated from Mycelia of the Lion’s Mane Medicinal Mushroom Hericium erinaceus (Agaricomycetes) Induced Apoptosis in Precancerous Human Gastric Cells. IJM 2017, 19. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Geng, Y.; Du, Y.; Li, W.; Lu, Z.-M.; Xu, H.-Y.; Xu, G.-H.; Shi, J.-S.; Xu, Z.-H. Polysaccharide of Hericium erinaceus Attenuates Colitis in C57BL/6 Mice via Regulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation-Related Signaling Pathways and Modulating the Composition of the Gut Microbiota. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2018, 57, 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.-Q.; Geng, Y.; Guan, Q.; Ren, Y.; Guo, L.; Lv, Q.; Lu, Z.-M.; Shi, J.-S.; Xu, Z.-H. Influence of Short-Term Consumption of Hericium erinaceus on Serum Biochemical Markers and the Changes of the Gut Microbiota: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1008. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Chemistry, Nutrition, and Health-Promoting Properties of Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane) Mushroom Fruiting Bodies and Mycelia and Their Bioactive Compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7108–7123. [CrossRef]

- Kawagishi, H.; Shimada, A.; Shirai, R.; Okamoto, K.; Ojima, F.; Sakamoto, H.; Ishiguro, Y.; Furukawa, S. Erinacines A, B and C, Strong Stimulators of Nerve Growth Factor (NGF)-Synthesis, from the Mycelia of Hericium erinaceum. Tetrahedron Letters 1994, 35, 1569–1572. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.-J.; Shen, J.-W.; Yu, H.-Y.; Ruan, Y.; Wu, T.-T.; Zhao, X. Hericenones and Erinacines: Stimulators of Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) Biosynthesis in Hericium erinaceus. Mycology 2010, 1, 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Doar, E.; Meyer, K.W.; Bair, Z.J.; Nally, R.; McNalley, S.; Davis, R.; Beathard, C. Influences of Substrate and Tissue Type on Erinacine Production and Biosynthetic Gene Expression in Hericium erinaceus. Fungal Biol Biotechnol 2025, 12, 4. [CrossRef]

- Kawagishi, H.; Zhuang, C. Compounds for Dementia from Hericium erinaceum. Drugs of the Future 2008, 33, 0149. [CrossRef]

- Shimbo, M.; Kawagishi, H.; Yokogoshi, H. Erinacine A Increases Catecholamine and Nerve Growth Factor Content in the Central Nervous System of Rats. Nutrition Research 2005, 25, 617–623. [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biology 2014, 15, 550. [CrossRef]

- Dinis, T.C.P.; Madeira, V.M.C.; Almeida, L.M. Action of Phenolic Derivatives (Acetaminophen, Salicylate, and 5-Aminosalicylate) as Inhibitors of Membrane Lipid Peroxidation and as Peroxyl Radical Scavengers. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 1994, 315, 161–169. [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.Bt.Md.; Hasan, M.H.; Armayni, U.A.; Ahmad, M.S.B.; Wahab, I.A. The Ferrous Iron Chelating Assay of Extracts. The Open Conference Proceedings Journal 2013, 4, 1555. [CrossRef]

- Cambier, S.; Gouwy, M.; Proost, P. The Chemokines CXCL8 and CXCL12: Molecular and Functional Properties, Role in Disease and Efforts towards Pharmacological Intervention. Cell Mol Immunol 2023, 20, 217–251. [CrossRef]

- Fialkow, L.; Wang, Y.; Downey, G.P. Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species as Signaling Molecules Regulating Neutrophil Function. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2007, 42, 153–164. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.; Dittrich-Breiholz, O.; Holtmann, H.; Kracht, M. Multiple Control of Interleukin-8 Gene Expression. J Leukoc Biol 2002, 72, 847–855.

- Vacchini, A.; Mortier, A.; Proost, P.; Locati, M.; Metzemaekers, M.; Borroni, E.M. Differential Effects of Posttranslational Modifications of CXCL8/Interleukin-8 on CXCR1 and CXCR2 Internalization and Signaling Properties. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 3768. [CrossRef]

- Freen-van Heeren, J.J. Post-Transcriptional Control of T-Cell Cytokine Production: Implications for Cancer Therapy. Immunology 2021, 164, 57–72. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Sironi, M.; Vecchi, A.; Colotta, F.; Mantovani, A.; Locati, M. IL-8 Induces a Specific Transcriptional Profile in Human Neutrophils: Synergism with LPS for IL-1 Production. European Journal of Immunology 2004, 34, 2286–2292. [CrossRef]

- Luís, J.P.; Simões, C.J.V.; Brito, R.M.M. The Therapeutic Prospects of Targeting IL-1R1 for the Modulation of Neuroinflammation in Central Nervous System Disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 1731. [CrossRef]

- Arend, W.P. The Balance between IL-1 and IL-1Ra in Disease. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2002, 13, 323–340. [CrossRef]

- Kaplanski, G.; Farnarier, C.; Kaplanski, S.; Porat, R.; Shapiro, L.; Bongrand, P.; Dinarello, C.A. Interleukin-1 Induces Interleukin-8 Secretion from Endothelial Cells by a Juxtacrine Mechanism. Blood 1994, 84, 4242–4248. [CrossRef]

- Freihat, L.A.; Wheeler, J.I.; Wong, A.; Turek, I.; Manallack, D.T.; Irving, H.R. IRAK3 Modulates Downstream Innate Immune Signalling through Its Guanylate Cyclase Activity. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 15468. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Gazzinelli, R.T. Regulation of Innate Immune Signaling by IRAK Proteins. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Dambuza, I.M.; Brown, G.D. C-Type Lectins in Immunity: Recent Developments. Current Opinion in Immunology 2015, 32, 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Geijtenbeek, T.B.H.; Gringhuis, S.I. C-Type Lectin Receptors in the Control of T Helper Cell Differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol 2016, 16, 433–448. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Hirota, K. The Pathogenicity of Th17 Cells in Autoimmune Diseases. Semin Immunopathol 2019, 41, 283–297. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-Y.; Tang, J.; Zheng, P.; Liu, Y. CD24 and Siglec-10 Selectively Repress Tissue Damage-Induced Immune Responses. Science 2009, 323, 1722–1725. [CrossRef]

- Wevers, B.A. C-Type Lectin Signaling in Dendritic Cells: Molecular Control of Antifungal Inflammation, 2014.

- Wevers, B.A.; Kaptein, T.M.; Zijlstra-Willems, E.M.; Theelen, B.; Boekhout, T.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.H.; Gringhuis, S.I. Fungal Engagement of the C-Type Lectin Mincle Suppresses Dectin-1-Induced Antifungal Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 494–505. [CrossRef]

- Romagnani, S. IL4I1: Key Immunoregulator at a Crossroads of Divergent T-Cell Functions. Eur J Immunol 2016, 46, 2302–2305. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, W.; Sun, B. Th1/Th2 Cell Differentiation and Molecular Signals. In T Helper Cell Differentiation and Their Function; Sun, B., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2014; pp. 15–44 ISBN 978-94-017-9487-9.

- Downton, P.; Bagnall, J.S.; England, H.; Spiller, D.G.; Humphreys, N.E.; Jackson, D.A.; Paszek, P.; White, M.R.H.; Adamson, A.D. Overexpression of IκB⍺ Modulates NF-κB Activation of Inflammatory Target Gene Expression. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Oeckinghaus, A.; Ghosh, S. The NF-κB Family of Transcription Factors and Its Regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009, 1, a000034. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.-C. NF-κB Signaling in Inflammation. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2017, 2, 17023. [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.K.; Ramesh, G.T. Interleukin-8 Induces Nuclear Transcription Factor-κB through a TRAF6-Dependent Pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 7010–7021. [CrossRef]

- Whitley, S.K.; Balasubramani, A.; Zindl, C.L.; Sen, R.; Shibata, Y.; Crawford, G.E.; Weathington, N.M.; Hatton, R.D.; Weaver, C.T. IL-1R Signaling Promotes STAT3 and NF-κB Factor Recruitment to Distal Cis-Regulatory Elements That Regulate Il17a/f Transcription. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2018, 293, 15790–15800. [CrossRef]

- Verstrepen, L.; Bekaert, T.; Chau, T.-L.; Tavernier, J.; Chariot, A.; Beyaert, R. TLR-4, IL-1R and TNF-R Signaling to NF-κB: Variations on a Common Theme. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 2964–2978. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-C. The Non-Canonical NF-κB Pathway in Immunity and Inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2017, 17, 545–558. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Deng, X.; Xie, X.; Liu, Y.; Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Lai, L. Activation of Glutathione Peroxidase 4 as a Novel Anti-Inflammatory Strategy. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Hu, H.; Li, H.S.; Yu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Brittain, G.C.; Zou, Q.; Cheng, X.; Mallette, F.A.; Watowich, S.S.; et al. Noncanonical NF-κB Pathway Controls the Production of Type I Interferons in Antiviral Innate Immunity. Immunity 2014, 40, 342–354. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-C. The Noncanonical NF-κB Pathway. Immunological Reviews 2012, 246, 125–140. [CrossRef]

- De Silva, N.S.; Silva, K.; Anderson, M.M.; Bhagat, G.; Klein, U. Impairment of Mature B Cell Maintenance upon Combined Deletion of the Alternative NF-κB Transcription Factors RELB and NF-κB2 in B Cells. The Journal of Immunology 2016, 196, 2591–2601. [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.L.; Weinerman, B.; Basole, C.; Salazar, J.C. TLR8: The Forgotten Relative Revindicated. Cell Mol Immunol 2012, 9, 434–438. [CrossRef]

- Pestka, S.; Kotenko, S.V.; Muthukumaran, G.; Izotova, L.S.; Cook, J.R.; Garotta, G. The Interferon Gamma (IFN-γ) Receptor: A Paradigm for the Multichain Cytokine Receptor. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 1997, 8, 189–206. [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A.; Novick, D.; Puren, A.J.; Fantuzzi, G.; Shapiro, L.; Mühl, H.; Yoon, D.-Y.; Reznikov, L.L.; Kim, S.-H.; Rubinstein, M. Overview of Interleukin-18: More than an Interferon-γ Inducing Factor. J Leukoc Biol. 1998, 63, 658–664. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Okamura, H.; Wada, M.; Nagata, K.; Tamura, T. Endotoxin-Induced Serum Factor That Stimulates Gamma Interferon Production. Infection and Immunity 1989, 57, 590–595. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, T.; Okamura, H.; Tagawa, Y.-I.; Iwakura, Y.; Nakanishi, K. Interleukin 18 Together with Interleukin 12 Inhibits IgE Production by Induction of Interferon-γ Production from Activated B Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1997, 94, 3948–3953. [CrossRef]

- Bian, F.; Yan, D.; Wu, X.; Yang, C. A Biological Perspective of TLR8 Signaling in Host Defense and Inflammation. Infectious Microbes & Diseases 2023, 5, 44. [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.C.S.; Carneiro, B.M.; Batista, M.N.; Akinaga, M.M.; Bittar, C.; Rahal, P. Heat Shock Proteins HSPB8 and DNAJC5B Have HCV Antiviral Activity. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0188467. [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A.; Novick, D.; Kim, S.; Kaplanski, G. Interleukin-18 and IL-18 Binding Protein. Front Immunol 2013, 4, 289. [CrossRef]

- Elder, M.J.; Webster, S.J.; Chee, R.; Williams, D.L.; Hill Gaston, J.S.; Goodall, J.C. β-Glucan Size Controls Dectin-1-Mediated Immune Responses in Human Dendritic Cells by Regulating IL-1β Production. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.J.; Rezoagli, E.; Major, I.; Rowan, N.J.; Laffey, J.G. β-Glucan Metabolic and Immunomodulatory Properties and Potential for Clinical Application. Journal of Fungi 2020, 6, 356. [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, L.; Krizan, J.; Sima, P.; Stakheev, D.; Caja, F.; Rajsiglova, L.; Horak, V.; Saieh, M. Immunostimulatory Properties and Antitumor Activities of Glucans (Review). Int J Oncol 2013, 43, 357–364. [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Rao, X.; Sigdel, K.R. Regulation of Inflammation in Autoimmune Disease. J Immunol Res 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Hasan, S.; Sharma, S.; Nagra, S.; Yamaguchi, D.T.; Wong, D.T.W.; Hahn, B.H.; Hossain, A. Th17 Cells in Inflammation and Autoimmunity. Autoimmunity Reviews 2014, 13, 1174–1181. [CrossRef]

- Alschuler, L.; Weil, A.; Horwitz, R.; Stamets, P.; Chiasson, A.M.; Crocker, R.; Maizes, V. Integrative Considerations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. EXPLORE 2020, 16, 354–356. [CrossRef]

- Potere, N.; Buono, M.G.D.; Caricchio, R.; Cremer, P.C.; Vecchié, A.; Porreca, E.; Gasperina, D.D.; Dentali, F.; Abbate, A.; Bonaventura, A. Interleukin-1 and the NLRP3 Inflammasome in COVID-19: Pathogenetic and Therapeutic Implications. eBioMedicine 2022, 85. [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.Z.; Bujko, K.; Ciechanowicz, A.; Sielatycka, K.; Cymer, M.; Marlicz, W.; Kucia, M. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Receptor ACE2 Is Expressed on Very Small CD45− Precursors of Hematopoietic and Endothelial Cells and in Response to Virus Spike Protein Activates the Nlrp3 Inflammasome. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2021, 17, 266–277. [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska, E.; Agier, J.; Różalska, S.; Jurczak, M.; Góralczyk-Bińkowska, A.; Żelechowska, P. Fungal β-Glucans Shape Innate Immune Responses in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs): An in Vitro Study on PRR Regulation, Cytokine Expression, and Oxidative Balance. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 6458. [CrossRef]

- Mata-Martínez, P.; Bergón-Gutiérrez, M.; del Fresno, C. Dectin-1 Signaling Update: New Perspectives for Trained Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Vuscan, P.; Kischkel, B.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Netea, M.G. Trained Immunity: General and Emerging Concepts. Immunological Reviews 2024, 323, 164–185. [CrossRef]

- Vetvicka, V.; Vannucci, L.; Sima, P. β-Glucan as a New Tool in Vaccine Development. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology 2020, 91, e12833. [CrossRef]

- Eliza, W.L.Y.; Fai, C.K.; Chung, L.P. Efficacy of Yun Zhi (Coriolus versicolor) on Survival in Cancer Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2012, 6, 78–87. [CrossRef]

- Quayle, K.; Coy, C.; Standish, L.; Lu, H. The TLR2 Agonist in Polysaccharide-K Is a Structurally Distinct Lipid Which Acts Synergistically with the Protein-Bound β-Glucan. J Nat Med 2015, 69, 198–208. [CrossRef]

- Benson, K.F.; Stamets, P.; Davis, R.; Nally, R.; Taylor, A.; Slater, S.; Jensen, G.S. The Mycelium of the Trametes Versicolor (Turkey Tail) Mushroom and Its Fermented Substrate Each Show Potent and Complementary Immune Activating Properties in Vitro. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2019, 19, 342. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, F.; Yin, H.; Huang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Mao, N.; Sun, B.; Wang, G. Ferroptosis: Past, Present and Future. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Hou, W.; Song, X.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Ferroptosis: Process and Function. Cell Death Differ 2016, 23, 369–379. [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Ratti, B.A.; O’Brien, J.G.; Lautenschlager, S.O.; Gius, D.R.; Bonini, M.G.; Zhu, Y. Manganese Superoxide Dismutase (SOD2): Is There a Center in the Universe of Mitochondrial Redox Signaling? J Bioenerg Biomembr 2017, 49, 325–333. [CrossRef]

- Takakura, Y.; Machida, M.; Terada, N.; Katsumi, Y.; Kawamura, S.; Horie, K.; Miyauchi, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Akiyama, N.; Seki, T.; et al. Mitochondrial Protein C15ORF48 Is a Stress-Independent Inducer of Autophagy That Regulates Oxidative Stress and Autoimmunity. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 953. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, C.-C.; Wang, L. Secretory Kinase Fam20C Tunes Endoplasmic Reticulum Redox State via Phosphorylation of Ero1α. EMBO J 2018, 37, e98699. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, X.; An, P.; Shen, Y.; Wu, Q.; Yu, Y.; Wang, F. Metalloreductase Steap3 Coordinates the Regulation of Iron Homeostasis and Inflammatory Responses. Haematologica 2012, 97, 1826–1835. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; An, Z.; Lei, H.; Liao, H.; Guo, X. Role of the Human Cytochrome B561 Family in Iron Metabolism and Tumors (Review). Oncol Lett 2025, 29, 111. [CrossRef]

- Hatori, Y.; Lutsenko, S. An Expanding Range of Functions for the Copper Chaperone/Antioxidant Protein Atox1. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 19, 945–957. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xiao, P.; Qiu, B.; Yu, H.-F.; Teng, C.-B. Copper Chaperone Antioxidant 1: Multiple Roles and a Potential Therapeutic Target. J Mol Med 2023, 101, 527–542. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(A) Percent cell viability of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) treated with Host Defense Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus, HDLM) relative to Vehicle (PBS) as evaluated by MTT assay (n = 6 wells per treatment concentration; significance evaluated relative to the vehicle control, two-tailed t-test, unequal variances, p<0.05: *, p<0.01: **, p<0.001: ***). (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) for HDLM- and Vehicle-treated samples evaluating the similarities or differences between these treatment groups based on their transcriptomic clustering patterns (n = 6). (C) Volcano plot for HDLM-treated PBMCs relative to Vehicle, displaying the magnitude of differential gene expression (log2FoldChange) in relation to statistical significance (-log10(padj)). Statistically significant results are indicated in blue for downregulated genes and red for upregulated genes (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05). (D) Top 10 up- and down-regulated genes by fold change (FC) for the HDLM treatment relative to Vehicle (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05).

Figure 1.

(A) Percent cell viability of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) treated with Host Defense Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus, HDLM) relative to Vehicle (PBS) as evaluated by MTT assay (n = 6 wells per treatment concentration; significance evaluated relative to the vehicle control, two-tailed t-test, unequal variances, p<0.05: *, p<0.01: **, p<0.001: ***). (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) for HDLM- and Vehicle-treated samples evaluating the similarities or differences between these treatment groups based on their transcriptomic clustering patterns (n = 6). (C) Volcano plot for HDLM-treated PBMCs relative to Vehicle, displaying the magnitude of differential gene expression (log2FoldChange) in relation to statistical significance (-log10(padj)). Statistically significant results are indicated in blue for downregulated genes and red for upregulated genes (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05). (D) Top 10 up- and down-regulated genes by fold change (FC) for the HDLM treatment relative to Vehicle (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05).

Figure 2.

(A) KEGG and (B) Reactome dot plots for HDLM-treated PBMCs relative to Vehicle (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05). (C) Immune-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified in HDLM-treated PBMCs compared to Vehicle (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05). (D) IL-4-like and CXC subfamily sections of the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction KEGG pathway map, with HDLM DEGs highlighted by FC value (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05).

Figure 2.

(A) KEGG and (B) Reactome dot plots for HDLM-treated PBMCs relative to Vehicle (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05). (C) Immune-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified in HDLM-treated PBMCs compared to Vehicle (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05). (D) IL-4-like and CXC subfamily sections of the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction KEGG pathway map, with HDLM DEGs highlighted by FC value (n = 6, DESeq2, padj<0.05).

Figure 3.

Cytokine protein responses in HDLM-treated human PBMCs under basal and inflammatory conditions. (A) IL-1RA under basal conditions (n = 6). (B–C) IL-8 under basal (B) and inflammatory (C) conditions (n = 4). (D–E) TNF-α under basal (D) and inflammatory (E) conditions (n = 4). In all cases, significance was evaluated relative to the vehicle control using two-tailed t-tests with unequal variances (p<0.05: *, p < 0.01: **, p < 0.001: ***).

Figure 3.

Cytokine protein responses in HDLM-treated human PBMCs under basal and inflammatory conditions. (A) IL-1RA under basal conditions (n = 6). (B–C) IL-8 under basal (B) and inflammatory (C) conditions (n = 4). (D–E) TNF-α under basal (D) and inflammatory (E) conditions (n = 4). In all cases, significance was evaluated relative to the vehicle control using two-tailed t-tests with unequal variances (p<0.05: *, p < 0.01: **, p < 0.001: ***).

Figure 4.

IL-1β protein responses in human PBMCs treated with HDLM or H. erinaceus fruit body extract powder (FBE) under basal (A) and inflammatory (B) conditions (n = 4, p < 0.05: *, p < 0.01: **, p < 0.001: ***).

Figure 4.

IL-1β protein responses in human PBMCs treated with HDLM or H. erinaceus fruit body extract powder (FBE) under basal (A) and inflammatory (B) conditions (n = 4, p < 0.05: *, p < 0.01: **, p < 0.001: ***).

Figure 5.

Antioxidant capacity of HDLM evaluated by DPPH assay (n = 8; significance evaluated relative to the maximal signal control, two-tailed t-test, unequal variances, p<0.05: *, p<0.01: **, p<0.001: ***).

Figure 5.

Antioxidant capacity of HDLM evaluated by DPPH assay (n = 8; significance evaluated relative to the maximal signal control, two-tailed t-test, unequal variances, p<0.05: *, p<0.01: **, p<0.001: ***).

Figure 6.

Ferrous iron chelation capacity of HDLM and FBE, expressed as EDTA µM equivalents (n = 5; significance testing performed by comparing each concentration of HDLM to the equivalent FBE concentration, two-tailed t-test, unequal variances, p<0.05: *, p<0.01: **, p<0.001: ***).

Figure 6.

Ferrous iron chelation capacity of HDLM and FBE, expressed as EDTA µM equivalents (n = 5; significance testing performed by comparing each concentration of HDLM to the equivalent FBE concentration, two-tailed t-test, unequal variances, p<0.05: *, p<0.01: **, p<0.001: ***).

Figure 7.

Model of the immunomodulatory and cellular stress quenching activity of HDLM in human PBMCs. Data revealed modulatory dynamics surrounding the NF-κB/IL-8 (purple), IL-1 (blue), and TNF (orange) axes that simultaneously activate and pacify these immune pathways. Antioxidant activity is shown in green, with dotted lines indicating less direct regulatory effects.

Figure 7.

Model of the immunomodulatory and cellular stress quenching activity of HDLM in human PBMCs. Data revealed modulatory dynamics surrounding the NF-κB/IL-8 (purple), IL-1 (blue), and TNF (orange) axes that simultaneously activate and pacify these immune pathways. Antioxidant activity is shown in green, with dotted lines indicating less direct regulatory effects.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).