1. Introduction

1.1. Global Context: The Challenges of Rock-Cut Heritage and the Turn to Digitalization

Rock-cut heritage sites, as invaluable treasures of human civilization, are currently facing unprecedented crises in preservation and transmission. These challenges stem from three intrinsic contradictions. Firstly, the material fragility of the caves, murals, and sculptures renders them inherently vulnerable to environmental degradation [

1,

2]. Secondly, the imperative of public accessibility clashes with the perils of over-tourism, as visitor influxes alter microclimates and directly endanger fragile relics [

3]. Thirdly, the heritage’s profound interpretive complexity, encompassing religious, historical, and artistic dimensions, resists full comprehension by non-specialists within the brief span of an on-site visit [

4].

To address these challenges, digital technologies have been globally recognized as a critical solution. From Italy’s Virtual Sistine Chapel to Cambodia’s Angkor Digital Archive, such projects demonstrate how virtual restoration, online exhibitions, and immersive experiences can both safeguard heritage through permanent digital archives and transcend spatial-temporal limitations, greatly enhancing accessibility and interpretive depth [

5,

6,

7]. UNESCO’s advocacy for digital interpretation for sustainable heritage management has thus become a guiding vision for future heritage practices [

8].

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly reshaped the global landscape of cultural heritage interpretation and dissemination. Restrictions on physical access to museums and heritage sites accelerated the global shift toward digital exhibitions, virtual archives, and hybrid cultural experiences that integrate both on-site and online engagement [

9,

10,

11]. This transformation has expanded digital heritage from a supplementary preservation tool into a primary medium of cultural continuity, sustaining public access and intercultural dialogue during periods of social disruption.

Within this post-pandemic context,

Digital Dunhuang [

12] emerges as an exemplary model of resilience and innovation. Like the digital exhibitions developed during the pandemic, it demonstrates how immersive media can preserve not only visual information but also the emotional and spiritual dimensions of heritage. By combining virtual exhibitions, interactive installations, and online dissemination,

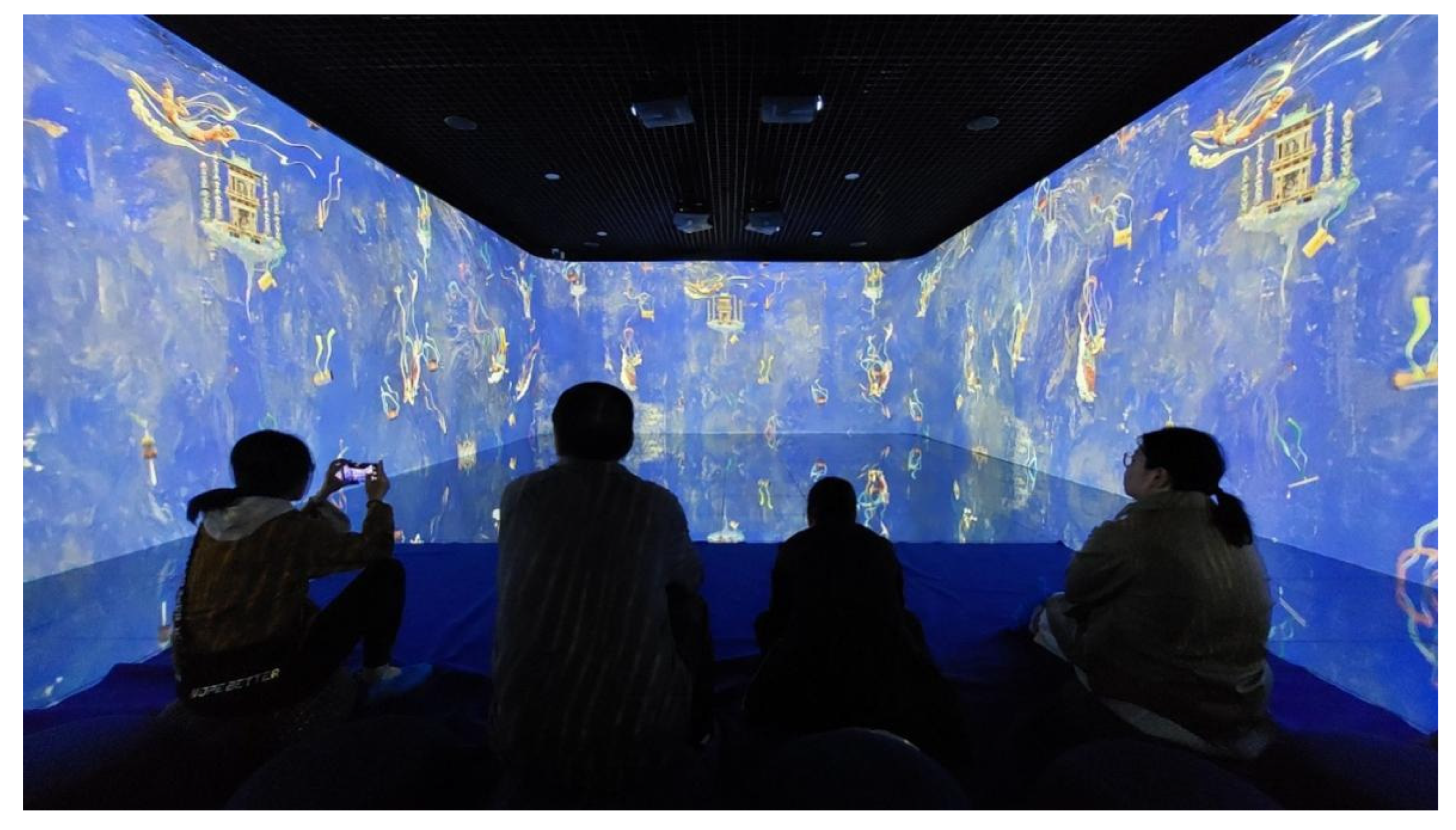

Digital Dunhuang exemplifies the hybrid paradigm of contemporary cultural communication that blends global touring with digital participation. Visitors can engage with immersive virtual experiences that recreate Dunhuang murals in 3D, allowing them to explore both the music and artistic sculptures of the caves (see

Figure 1). Iconic elements, such as Flying Apsaras and Buddha statues, are recreated in the virtual environment (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

In recent years, the emergence of digital heritage studies has signalled a paradigmatic shift in how heritage is understood, preserved, and experienced. Digital heritage projects are no longer merely technological archives or visual surrogates; they are increasingly conceived as interpretive ecosystems that reshape human interactions with history and collective memory [

13,

14]. Their mission has expanded to include inclusive access, participatory engagement, and cross-cultural understanding—all key pillars of sustainable cultural development [

15].

At the European level, projects such as

Europeana have exemplified how digital archives can evolve into participatory ecosystems that redefine the relationship between institutions and the public, allowing audiences not only to “consume” culture but to participate in its reinterpretation [

16,

17,

18]. This participatory logic resonates with the notion of shared authority, suggesting that cultural meaning should be co-created by experts and the public alike [

19]. Hence, the digital turn is not merely a technological phenomenon but also a cultural repositioning that challenges conventional boundaries of authenticity, aura, and experience [

20].

Within this global trend, Digital Dunhuang stands as one of the most culturally significant and technologically sophisticated exemplars. Its innovation lies not only in high-precision 3D scanning and virtual reconstruction, but also in the digital transformation of Buddhist art and philosophy into contemporary aesthetic and emotional experiences (reference). In contrast to Western projects such as the Lascaux Virtual Cave in France or Pompeii 3D Experience in Italy, Digital Dunhuang emphasizes the integration of aesthetics, spirituality, and education—embodying the Chinese hermeneutic logic of “revealing principle through imagery and reaching emotion through understanding”.

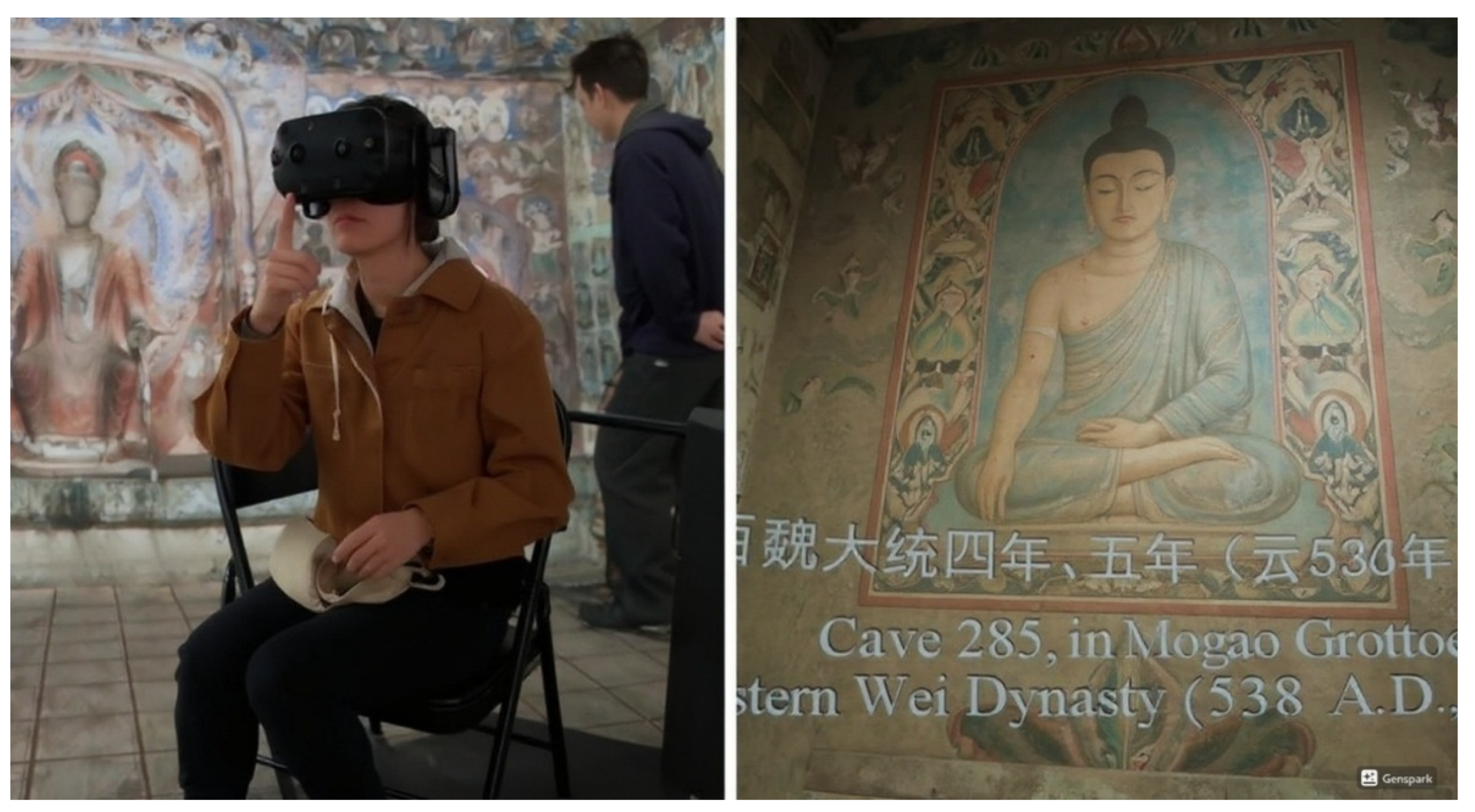

Immersive digital experiences in heritage conservation use VR, AR, and 3D technologies to allow audiences to explore and interact with cultural heritage sites, supporting both public engagement and the scientific documentation, preservation, and interpretation of historical artifacts and spaces. Visitors can engage with immersive 3D virtual experiences that recreate Dunhuang murals in 3D (see

Figure 4).” It represents a living heritage model in which digital media function not only as instruments of preservation but also as bridges of emotion and philosophy.

Compared with global counterparts, Digital Dunhuang reveals two distinctive characteristics:

Core Philosophy: While the Lascaux and Pompeii projects primarily focus on visual replication and visitor management, Dunhuang centers on interpretive transformation—not merely showing what it was but revealing why it matters.

Focus of Experience: Western digital heritage projects often prioritize visual fidelity, whereas Digital Dunhuang seeks experiential authenticity—using digital means to evoke spiritual immersion and cultural resonance. Its virtual authenticity thus derives not only from visual realism but from its ability to recreate the serenity and aesthetic resonance of Buddhist art.

The significance of Digital Dunhuang transcends local or national boundaries. Positioned at the forefront of global heritage interpretation, it demonstrates how digital media can reconcile the tension between preservation and openness. By integrating artistic creativity, technical precision, and interpretive theory, it provides a new paradigm for heritage institutions worldwide—redefining what it means to preserve, experience, and interpret cultural heritage in the digital age.

1.2. The Chinese Context: The Specificity of Dunhuang and the Paradigmatic Role of “Digital Dunhuang”

Within this global shift, China’s Mogao Caves in Dunhuang serve as a highly emblematic case. As a World Heritage site and a key node along the Silk Road, Dunhuang embodies over a millennium of Buddhist art, history, and intercultural exchange. Yet, the tension between its global renown and fragile ecosystem has become increasingly pronounced. It is in this context that the Digital Dunhuang project emerged. Since the opening of its exhibition center in 2016, it has become a global benchmark in the digital heritage field.

Digital Dunhuang is far more than a technological archive. It constitutes a comprehensive digital ecosystem, encompassing high-fidelity virtual caves, dome-screen films, interactive installations, and even digital musical experiences based on research into ancient scores. This system pursues dual objectives: on the one hand, to alleviate visitor pressure on the physical caves through digital alternatives, fulfilling its conservation mission; on the other, to offer audiences deeper cultural engagement beyond the limits of on-site visits. The performance of

Silk Road, Flower Rain vividly translates the murals into stage art (see

Figure 5). The digital dome film

“Dreamlike Buddhist Palace” combines ancient Dunhuang music with modern orchestration and surround sound to create an audiovisual experience (see

Figure 6).

1.3. Research Gap: From Technological Focus to Experience and Interpretation

Despite the technological achievements of Digital Dunhuang, academic discourse has been largely secondary to its practical advancements. Existing studies have predominantly concentrated on technical and preservation dimensions, such as 3D laser scanning accuracy, color restoration algorithms, and database architecture. While important, these discussions tend to confine digital heritage within the framework of preservation tools or display media.

Digital restoration is achieved using robotic scanning technology (see

Figure 7). While these discussions are important, they tend to confine digital heritage within the framework of preservation tools or display media. As hermeneutic theory emphasizes, the value of heritage is not only in the object itself but emerges through interaction with the viewer. Therefore, this study argues that

Digital Dunhuang has not yet been systematically examined through the lens of visitor experience and interpretive theory. Cave 285 exemplifies early medieval Chinese Buddhist art (see

Figure 8).

1.4. Research Questions and Significance

Building upon the identified gap, this study aims to address the following core research questions:

How does the immersive digital ecosystem of Digital Dunhuang, including dome-screen cinema, virtual caves, and interactive installations, reconstruct visitors’ meaning-making and cognitive understanding of Dunhuang’s cultural heritage?

Specifically, how do multisensory digital technologies function as interpretive mechanisms that foster deep emotional connections and cultural resonance among visitors?

Theoretically, this study moves beyond descriptive accounts of technological utility to investigate digital media as a medium of meaning-making, enriching theoretical discourse within digital heritage interpretation. Practically, the findings offer empirical insights for optimizing interpretive strategies at Dunhuang and similar fragile heritage sites, contributing to sustainable management and global dissemination of cultural value.

2. Theoretical Framework

To systematically analyze how

Digital Dunhuang reconstructs visitors’ meaning-making processes, this study adopts Freeman Tilden’s “Six Principles of Heritage Interpretation” as the core theoretical framework [

21]. Tilden contends that effective heritage interpretation is not about the transmission of facts, but about revealing meaning, building connections, and inspiring thought—ultimately leading to appreciation and conservation. His guiding philosophy—

“Through interpretation, understanding; through understanding, appreciation; through appreciation, protection”—resonates deeply with the mission of

Digital Dunhuang, whose stated goal is

“preservation as foundation, dissemination as purpose” [

22].

This research translates Tilden’s principles into three analytical dimensions, integrating the Chinese interpretive logic of “from material perception to rational understanding, and from rational understanding to emotional resonance” (由物入理、由理入情), to construct a Digital Interpretive Hierarchy Model that elucidates the mechanisms and effects of Digital Dunhuang.

2.1. Reinterpreting Tilden in the Digital Age

In the context of digital heritage, Tilden’s framework [

21] provides a human-centered lens for understanding how audiences engage with heritage meaning. However, to apply his mid-20th-century principles effectively in the digital era, it is necessary to align them with contemporary media theory, particularly the concept of

remediation proposed by Bolter and Grusin [

23] and McLuhan’s idea that

“the medium is the message.” [

24].

The theory of remediation emphasizes that new media do not simply replace older forms, but continually re-mediate and re-interpret them, transforming how meaning is conveyed [

25]. McLuhan, meanwhile, reminds us that the characteristics of a medium inherently reshape human perception and cognition. In

Digital Dunhuang, this interplay manifests in how digital technologies restructure the relationship between the audience and heritage. Screens, immersive imagery, and virtual interactivity do more than transmit visual information; they redefine what it means to see and to feel.

While Tilden emphasized a gradual process from knowledge to understanding to emotional engagement, digital media adds an embodied sensory layer to this process. Interpretation in a digital environment is no longer dependent solely on textual or verbal mediation; it unfolds through multisensory interaction, real-time feedback, and spatial immersion, enabling visitors to participate bodily in meaning-making. Hence, Tilden’s goals of “inspiring thought” and “revealing meaning” are now technologically enhanced through what this study calls

“technologically empowered reinterpretation” [

21].

The pandemic context also prompted a re-evaluation of interpretive practices. As Han [

9] notes, digital exhibitions have become vital vehicles for intangible heritage communication, particularly during global lockdowns. Spennemann [

10] highlights that the act of “exhibiting heritage” in this period required rethinking presence and participation when physical co-location was impossible. Likewise, Volanakis [

11] emphasizes that post-pandemic heritage organizations increasingly adopt hybrid interpretive models that combine in-person engagement with digital extensions.

Digital Dunhuang resonates with these global shifts by integrating immersive technologies and new media matrices to foster participatory meaning-making, ensuring heritage accessibility across temporal and spatial boundaries.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated these shifts by forcing museums and heritage institutions to move rapidly online, expanding digital engagement into a primary mode of cultural interaction [

26]. In this context, Tilden’s aims of inspiring understanding and emotional engagement are technologically enhanced through multisensory interaction and spatial immersion [

13,

27]. This technologically empowered reinterpretation enriches interpretive outcomes with immediacy, agency, and personal relevance.

2.2. Digital Authenticity and Re-Mediated “Aura”

The ongoing scholarly debate over digital authenticity provides another critical theoretical foundation for this study. Jones [

28] argues that digital reproduction does not diminish authenticity but generates a new form of

informational authenticity, wherein audiences establish trust through perceived data accuracy, narrative coherence, and emotional resonance. Similarly, Parry [

29] conceptualizes authenticity in digital heritage as a relational experience. This experience arises not from the material original, but through processes of human–machine interaction and cultural empathy.

From this perspective,

Digital Dunhuang’s virtual caves and immersive projections are not substitutes for the real Mogao Caves, but new paradigms of authenticity. They regenerate the spiritual and aesthetic meanings of Buddhist art through digital media, creating an experiential truth grounded in emotional and cognitive resonance rather than physical originality. This notion challenges Walter Benjamin’s well-known argument that the aura of an artwork, defined as the “unique appearance of a distance, however close it may be,” inevitably fades in the age of mechanical reproduction [

20]. In contrast,

Digital Dunhuang suggests that digital interpretation can reconstruct aura through presence, translating historical and spiritual depth into contemporary emotional experience.

2.3. Chinese Hermeneutics and the Logic of “From the Tangible to the Emotional”

Within Chinese cultural epistemology, the interpretive progression of “from material perception to rational understanding, and from rational understanding to emotional resonance” encapsulates a holistic view of cognition and aesthetics. It reflects the traditional unity of form (物), principle (理), and emotion (情).

This logic profoundly aligns with Tilden’s interpretive philosophy [

21], which moves from knowledge (understanding the object) to appreciation (valuing the meaning) to protection (caring through emotion). Integrating this indigenous perspective enables a culturally sensitive reading of digital interpretation practices in Dunhuang.

Drawing upon Gadamer’s hermeneutic theory [

30], this process can be seen as a

fusion of horizons: the viewer, through digital mediation, enters the historical world of the artifact’s creators and engages in a dialogue across time and culture. In this sense, digital media do not obstruct understanding but rather serve as bridges of empathy, allowing visitors to transcend the act of looking and to achieve resonant understanding, representing a transformation from “seeing” to “feeling.” For example, Nighttime drone projections recreate Dunhuang murals across the desert landscape (see

Figure 9).

2.4. Mapping Tilden’s Principles to the Mechanisms of Digital Dunhuang

To operationalize these theoretical insights, this study establishes a correspondence between Tilden’s six interpretive principles [

21] and the mechanisms observed in

Digital Dunhuang, summarized in the

Digital Interpretive Hierarchy Model (see

Table 1).

The model proposes that

Digital Dunhuang’s interpretive effect follows a progressive hierarchy. Beginning with aesthetic and sensory engagement, it advances through revelation and relation, enabling a cognitive leap from tangible form to rational understanding. Subsequently, through provocation and wholeness, it achieves emotional elevation and value identification, culminating in Tilden’s ideal cycle of

understanding → appreciation → protection [

21].

2.5. Toward a Synthesis: Digital Interpretation as Cultural Re-Mediation

In summary, the theoretical framework of this study integrates Tilden’s interpretive principles [

21], media theories of remediation, and debates on digital authenticity within a cross-cultural dialogue. This synthesis reveals a new dimension of heritage interpretation in the digital age: in a re-mediated environment,

digital authenticity and

cultural experience jointly propel a cyclical process of

understanding–empathy–stewardship. Through

Digital Dunhuang, heritage interpretation becomes not a passive transfer of information, but an active re-creation of meaning, in which technology functions as both a bridge to the past and a catalyst for emotional resonance in the present.

3. Research Design

To explore the mechanisms by which Digital Dunhuang reconstructs heritage meaning-making and visitor experience, this study adopts an interpretive qualitative research design. Rather than seeking statistical generalizability, the aim is to develop an in-depth understanding of the complex cognitive, emotional, and cultural processes involved in visitors’ engagement with digital heritage environments.

This section outlines the study’s methodological orientation, sampling strategy, ethical considerations, and data collection and analysis procedures, culminating in a comparative design that integrates both online and on-site experiences.

3.1. Research Orientation and Methodological Rationale

Given that Digital Dunhuang involves deeply embodied, affective, and interpretive visitor experiences, the study is grounded in interpretivism and constructivist epistemology. This perspective assumes that heritage meaning is co-constructed through interaction between visitors and exhibits, researchers and participants, and technology and culture, rather than pre-existing as an objective entity.

The qualitative orientation allows for the capture of contextual depth and experiential nuance, particularly relevant for exploring how digital media mediate understanding, emotion, and value perception. In this sense, qualitative inquiry is not merely descriptive but interpretive: it seeks to reconstruct the participants’ lived experiences as meaningful narratives that reveal underlying interpretive mechanisms.

The interpretive design is thus guided by three objectives:

To identify how digital technologies shape visitors’ perception and meaning-making processes;

To interpret how these processes translate into emotional and ethical engagement;

To evaluate how the overall digital interpretive ecosystem contributes to heritage appreciation and conservation awareness.

3.2. Research Participants and Sampling Strategy

To capture a comprehensive range of visitor perspectives, this study employs maximum variation sampling, which seeks diversity rather than representativeness. Given that Digital Dunhuang attracts audiences from multiple cultural, linguistic, and educational backgrounds, this strategy ensures analytical richness across interpretive responses.

Sample composition:

Age range: 18 to 70 years old

Educational background: Humanities, sciences, and arts

Nationalities represented: China, Japan, and several European countries

This heterogeneity enables cross-cultural comparison and facilitates exploration of how cultural background shapes cognitive and emotional engagement with digital heritage.

A total of 30 semi-structured interviews were conducted, supplemented by participant observation at the Digital Dunhuang Exhibition Centre and within its virtual online platform. Each interview lasted between 45 and 90 minutes, and all were audio-recorded with participants’ consent. Field notes and reflective memos were kept throughout the process to ensure contextual integrity and analytic transparency.

3.3. Ethical Considerations and Reflexivity

This research was conducted in strict compliance with the ethical guidelines stipulated by the British Sociological Association (BSA) [

31] and UNESCO [

8]. Before participation, all individuals received a full disclosure regarding the study’s objectives, the scope of data utilization, and the confidentiality protocols in place, upon which written informed consent was secured. The confidentiality of participants was protected through the anonymization of all personal data with non-identifiable codes, while audio recordings and transcripts were preserved in securely encrypted files with sole access granted to the researcher. Ethical rigor was further upheld through sustained reflexivity. Given the interpretive nature of the study, a reflexive journal was maintained to critically interrogate the researcher’s subjective positionality and preconceptions, a process that fortified analytical transparency and guarded against interpretive bias. In the presentation of findings, this reflexive practice ensured the faithful contextualization of participant quotations, preventing their selective deployment to reinforce prior arguments.

3.4. Data Collection Methods

3.4.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews were the primary data source. A flexible guide was used to allow participants to reflect freely on their experiences, perceptions, and emotional responses. Key themes included:

Perceived authenticity and emotional engagement;

Comparative reflections between digital and on-site heritage experiences;

Awareness of preservation and cultural significance after the visit.

Probing questions encouraged participants to articulate not just what they experienced but how they interpreted and emotionally processed those experiences. This interpretive depth is critical for linking empirical evidence with the theoretical framework of digital interpretation.

3.4.2. Participant Observation

Observation took place in both on-site and online contexts.

On-site observation was conducted at the Digital Dunhuang Exhibition Centre, focusing on how visitors interacted with dome-screen films, virtual caves, and interactive installations.

Online observation examined user behavior on the Digital Dunhuang International Website and its virtual browsing interface, documenting how remote users engage with immersive narratives and interpretive cues.

Field notes captured environmental cues, emotional expressions, moments of engagement or distraction, and instances of dialogue or reflection. These observations helped contextualize interview data and provided insight into the embodied and affective dimensions of digital experience.

3.5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed through thematic analysis, following the framework of Braun and Clarke [

32]. The process unfolded in three sequential stages using

NVivo 14 software to manage and code qualitative data systematically.

Each transcript and observation note was read line-by-line to identify initial concepts and recurrent patterns (e.g., “emotional resonance,” “virtual sacredness,” “time collapse”).

- 2.

Axial Coding:

Relationships between codes were examined to form subthemes (e.g., “embodied immersion,” “historical empathy,” “knowledge contextualization”). These subthemes were linked to the theoretical dimensions of

revelation,

relation, and

provocation derived from Tilden’s framework [

21].

- 3.

Selective Coding:

Core themes were integrated to construct an overarching interpretive model that aligns with the Digital Interpretive Hierarchy. This final synthesis explicates how digital experiences progress from cognitive reconstruction to emotional elevation and value internalization.

Reliability checks were conducted through peer debriefing and intercoder consistency testing. Two independent researchers reviewed a subset of transcripts, confirming analytical stability and transparency.

3.6. Comparative Design: Integrating Online and On-Site Experiences

Recognizing that Digital Dunhuang exists as both a physical immersive exhibition and an online virtual platform, this study incorporates a comparative multi-sited design.

On-site component: Examined sensory, spatial, and communal dimensions of embodied experience in the exhibition space, with particular attention to visitors’ responses to the dome-screen films and interactive installations.

Online component: Explored interpretive engagement in remote settings, focusing on digital immersion, comprehension depth, and perceived authenticity during virtual browsing.

This hybrid site comparison allows for a systematic examination of how different digital mediation environments shape cognitive and emotional processes. It also highlights the role of technology in bridging geographical, temporal, and cultural distances, showing digital heritage not as a substitute for physical experience but as a complementary interpretive environment.

3.7. Ensuring Validity and Trustworthiness

The trustworthiness of the study was secured through the implementation of established qualitative validation techniques. Triangulation of data sources, combining interviews, observational notes, and researcher reflexivity memos, was utilized to construct a robust understanding of the phenomena and minimize single-method bias [

33]. The reporting of findings is characterized by thick description [

34] to provide the necessary contextual depth for evaluating interpretive claims. The emergent thematic framework was subjected to member checking with participants, a process that serves as a corrective measure and strengthens interpretive credibility [

35]. The feedback obtained was incorporated, leading to nuanced adjustments that reinforced the authenticity and ethical rigor of the final narrative. Thus, by integrating these procedures with a reflexive and multi-modal approach, the research design aligns with the stringent ethical and theoretical expectations of contemporary digital heritage scholarship.

To summarize, the research design balances methodological rigor with interpretive sensitivity. It combines qualitative inquiry across multiple sites, ethical reflexivity, and systematic coding procedures to examine how Digital Dunhuang reconstructs heritage experience and meaning-making across cognitive, emotional, and ethical dimensions. Through this cross-cultural and cross-media framework, the study seeks to reveal how digital interpretation, when guided by human-centered hermeneutics, can transform not only how heritage is preserved but also how it is felt, understood, and protected in the contemporary world.

4. Findings and Discussion

Through thematic analysis of interview and observation data, this study reveals that

Digital Dunhuang systematically reconstructs visitors’ heritage experiences across three interconnected dimensions: cognitive, affective, and axiological. These dimensions correspond to the interpretive progression proposed in the Digital Interpretive Hierarchy Model, which moves from cognitive reconstruction to emotional elevation and finally to value internalization. This section discusses these findings in depth and relates them to Tilden’s interpretive principles, theories of re-mediation, and debates on digital authenticity [

21]. Together, they illuminate how

Digital Dunhuang redefines the processes through which visitors understand, feel, and commit to the safeguarding of cultural heritage in the digital age.

4.1. Cognitive Reconstruction: From “Knowledge Viewing” to “Contextual Understanding”

One of the most significant findings concerns the shift in visitors’ cognitive engagement. Traditional on-site visits to the Mogao Caves are constrained by preservation lighting and linear guided tours, resulting in fragmented and object-focused experiences. Visitors tend to recall individual murals or sculptures rather than grasping their historical and philosophical coherence.

In contrast,

Digital Dunhuang transforms this fragmented perception through its multi-modal digital narratives. The dome-screen films, for instance, weave the artistic essence of hundreds of caves into a continuous historical and aesthetic storyline. As one respondent vividly described: “Inside the real caves, I only saw isolated ‘points’ of beauty; in the digital film, I could finally perceive the ‘flow’ and ‘transformation’ of the Silk Road.” This quotation encapsulates the transition from visual accumulation to narrative integration. Digital media situate static artefacts within a living historical continuum, realizing what Tilden called “revelation” [

21], which is the act of exposing connections and meaning rather than merely stating facts.

A deeper mechanism underlying this cognitive transformation is what this study terms “temporal folding.” Through the immersive visual field of the dome projection, viewers inhabit a space where past and present, art and technology, converge. As another participant reflected: “When the camera moved from the flying apsaras to the desert horizon, I felt as though time was breathing with me—the ancient painters and I shared the same moment.” This experience exemplifies the remediation effect described by Bolter and Grusin: new media reconfigure older representational forms to produce a sensation of co-presence across time. Digital Dunhuang thus transcends linear viewing, enabling visitors to experience history as a fluid, sensory continuum.

In sum, digital interpretation redefines heritage cognition as situated understanding, in which visitors connect empirical perception with conceptual insight. The process embodies the shift “from the material to the rational” (由物及理), demonstrating that knowledge acquisition in digital heritage contexts is inherently interpretive and relational rather than purely informational.

4.2. Emotional Elevation: From “Static Gaze” to “Empathic Presence”

At the affective level, the research identifies a striking transformation from detached observation to embodied empathy. Whereas the physical site experience often fosters reverent distance, digital immersion evokes intimacy and emotional resonance. Many participants described the sensation of “being inside the cave” when viewing dome projections or interacting with virtual murals. One young visitor remarked: “When the camera zoomed into the mural details, it felt like I was flying myself, as I examined every stroke closely. It was breathtaking.”

This sense of corporeal immersion redefines the viewer’s role from spectator to participant. The digital environment creates what participants described as a “virtual sacred space,” a digitally mediated environment capable of inducing awe, reflection, and even spiritual feeling. Interestingly, most participants were fully aware of the artificial nature of the experience, yet they still reported a profound emotional impact. This shows that digital authenticity, the sense of truthfulness and sincerity evoked by digital representation, does not depend on material originality but on relational and affective engagement.

As several interviewees expressed, the digital replication did not diminish but rather reactivated their sense of aura. One participant summarized: “Even though I knew it was digital, the quietness, the light, and the music made me feel I was standing in front of something sacred. It touched me deeply.” This challenges Benjamin’s notion that mechanical reproduction necessarily erodes aura. Instead, Digital Dunhuang illustrates how digital presence can reconstruct aura through sensorial and emotional re-mediation. The carefully designed visual rhythm, dim lighting, and the spatial soundscape collectively generate a contemplative atmosphere, which restores the spiritual energy of the original site.

Emotional elevation also manifests through empathetic identification. Several visitors reported developing emotional connections with the figures and creators represented in the digital scenes. As one student described: “When I saw the digital restorer repainting the colors on the wall, I suddenly felt a desire to protect it myself.”

This statement captures the emergence of what Parry [

27] calls “relational authenticity”—authenticity experienced through empathy and care rather than physical originality. The digital heritage space thus becomes a site of co-created emotion, where audiences are both recipients and co-producers of meaning. In this transformation,

Digital Dunhuang extends Tilden’s notion of provocation [

21]: it not only stimulates intellectual curiosity but also provokes affective participation—the transformation of understanding into compassion.

4.3. Value Internalization: From “Cultural Appreciation” to “Protective Consciousness”

The final stage of interpretive transformation concerns the internalization of values. The data reveal that the digital experience fosters not merely aesthetic enjoyment but a deeper sense of ethical responsibility towards heritage preservation.

A recurrent theme across interviews was visitors’ heightened awareness of fragility. By visualizing the processes of mural fading, damage, and digital restoration,

Digital Dunhuang renders vulnerability visible and emotionally tangible. One interviewee observed: “Seeing how much effort goes into restoring these treasures made me realize how fragile and precious they are. I felt responsible to learn more and help protect them.” This statement echoes Tilden’s ultimate interpretive goal: “through understanding comes appreciation, and through appreciation, protection” [

21]. Digital interpretation serves as an incubator for stewardship, transforming passive spectators into potential advocates for heritage conservation.

Moreover, the project’s emphasis on accessibility and global dissemination encourages participants to view cultural preservation as a shared human duty. Experiencing Dunhuang’s spiritual and artistic essence online fosters what several respondents described as “cultural solidarity.” This refers to a shared moral recognition that the value of heritage goes beyond national boundaries.

Thus, Digital Dunhuang not only disseminates knowledge but also cultivates what might be called digital ethics of care, a collective awareness that technological mediation can and should serve the moral purpose of protecting the past. This finding extends the concept of digital authenticity into an ethical dimension: authenticity is not solely an ontological attribute but also a moral relation. Visitors perceive authenticity not because the digital copy is materially “real”, but because the experience resonates with their values and evokes a sense of duty to sustain cultural continuity.

4.4. Theoretical Reflection: The Duality and New Trajectories of Digital Interpretation

Synthesizing these findings reveals a fundamental duality in digital heritage interpretation. On one hand, digitalization renders heritage more accessible, emotionally engaging, and pedagogically powerful; on the other, it raises ongoing concerns about whether virtual reproductions dilute material authenticity. This tension encapsulates the central paradox of the digital heritage era, which is the balance between presence and preservation.

However, the Digital Dunhuang case suggests a third path beyond this dichotomy: the value of digital interpretation lies not in perfect replication of the material original but in technologically empowered re-interpretation. By creating multisensory experiences that integrate cognition, emotion, and ethics, Digital Dunhuang activates new layers of meaning and engagement. Rather than replacing the physical site, the digital project functions as a prologue and extension, serving as a preparatory and reflective space that deepens understanding and increases emotional readiness for encountering the authentic site. It connects rather than separates the digital and the real.

This insight contributes to a re-conceptualization of digital heritage as a dynamic hermeneutic process, wherein authenticity is continuously negotiated and co-created through interaction. Digital interpretation thus becomes a living practice of meaning-making, sustaining both the spirit of the past and the empathy of the present.

4.5. Summary

In conclusion, the findings demonstrate that Digital Dunhuang reconfigures the heritage experience through a triadic interpretive progression:

Cognitive Reconstruction – digital mediation transforms factual observation into contextual understanding.

Emotional Elevation – immersive presence evokes empathy and reconstitutes digital aura.

Value Internalization – emotional engagement translates into ethical responsibility and conservation awareness.

Together, these dimensions form a cyclical interpretive process of

understanding → appreciation → protection, echoing both Tilden’s philosophy [

21] and the Chinese hermeneutic principle of

from material to rational, from rational to emotional.

Ultimately, Digital Dunhuang exemplifies how digital interpretation can transcend the dichotomy between authenticity and simulation, restoring not only the visibility of heritage but also its spiritual vitality in the contemporary world.

5. Reconstructing Heritage Experience Through Digital Dunhuang

This study employs qualitative research methods to conduct an in-depth analysis of Digital Dunhuang as a representative case, systematically revealing how digital technologies, through their immersive ecosystem, reconstruct visitors’ heritage experiences and meaning-making at cognitive, emotional, and value levels. This section summarizes the key findings, elucidates their theoretical contributions and practical implications, and outlines directions for future research.

5.1. Research Conclusions

The core conclusion of this study is that the successful practice of Digital Dunhuang signals a paradigmatic shift in cultural heritage experience and education towards a “post-authenticity” era. Within this paradigm, the notion of heritage “authenticity” is no longer solely dependent on material objects or provenance. Instead, it emerges as a form of relational authenticity, co-constructed through technological mediation, emotional resonance, and deep cognitive engagement. Specifically, this study identifies the following mechanisms:

-

Cognitive Dimension

Digital technologies facilitate a transition from “knowledge observation” to “contextual understanding.” Through multimodal narratives and the “temporal folding” effect, Digital Dunhuang situates static and isolated artefacts within a dynamic and coherent historical-cultural context, effectively guiding visitors from perceiving the forms (“wu”) to understanding their underlying principles (“li”). This cognitive leap exemplifies Tilden’s principle of “revelation” [

21] in interpretation, demonstrating the potential of digital mediation to enhance intellectual comprehension of cultural heritage.

- 2.

-

Emotional Dimension

Digital experiences elevate engagement from “static gazing” to “empathetic presence.” The immersive environments foster a sense of bodily presence, while the carefully reconstructed “digital sacredness” elicits profound emotional identification and spiritual resonance. This constitutes a form of digital authenticity, grounded in both information fidelity and affective projection, facilitating a transformation from rational cognition (“li”) to emotional engagement (“qing”).

- 3.

-

Value Dimension

Digital interpretation ultimately promotes a transition from “cultural appreciation” to the internalization of “conservation consensus.” By visualizing both the vulnerability and extraordinary significance of heritage, Digital Dunhuang successfully stimulates visitors’ consciousness of responsibility and stewardship, thereby achieving the ultimate goal of Tilden’s interpretive philosophy [

21]: cultivating protective behaviors through understanding and aesthetic appreciation.

In summary, Digital Dunhuang demonstrates that the intersection of technology, cognition, emotion, and value can engender a holistic heritage experience that transcends traditional boundaries, highlighting the emerging potential of digital heritage to foster intellectual, emotional, and ethical engagement simultaneously.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Contributions

Building on the findings above, this study makes several significant theoretical contributions.

-

Introducing the Concept of “Digital Spiritual Heritage”

This research is among the first to explicitly define and theorize “digital spiritual heritage” as a form of cultural transmission mediated by digital technologies, capable of transcending material boundaries. Unlike conventional perspectives that emphasize digital heritage primarily as a technical tool for preservation or a sensory medium for display, this concept highlights its capacity to evoke aesthetic, religious, and humanistic comprehension. It underscores an intrinsic human need for meaning-making and transcendence in technologically mediated environments, signalling a shift in heritage theory from material preservation to the cultivation of experiential and reflective engagement.

-

Expanding Interpretive Frameworks in Heritage Studies

By integrating Tilden’s principles [

21] with traditional Chinese cognition—specifically the “from form to principle, from principle to emotion” logic—this study demonstrates a comprehensive interpretive framework in which cognitive understanding, emotional resonance, and value internalization are interconnected. This framework offers a theoretical lens for examining how digital mediation can simultaneously activate intellectual, affective, and ethical dimensions of heritage experience, providing a model for future empirical investigations in diverse cultural contexts.

-

Bridging Technology and Heritage Meaning-Making

The study empirically validates the mechanisms through which immersive technologies mediate relational authenticity, offering a nuanced understanding of how digital artefacts function not only as conveyors of information but also as catalysts for affective and ethical engagement. This advances theoretical discussions in digital heritage, suggesting that the evaluative criteria of authenticity and value are contextually co-constructed rather than intrinsically fixed.

5.2.2. Practical Implications

The findings also yield practical implications for heritage institutions, particularly those managing vulnerable cultural assets. Digitalization should be reconceptualized as more than a mechanism for archival preservation or visitor traffic management. Instead, it ought to be regarded as a strategic instrument for cultural interpretation and the dissemination of heritage values. Effective digital heritage management requires investment in the development of immersive ecosystems capable of eliciting multi-layered, multisensory experiences that engage visitors cognitively, emotionally, and ethically. Such environments not only enhance interpretive depth but also strengthen the public’s affective and moral connection to cultural heritage.

Interpretive content design should integrate Tilden’s foundational principles of interpretation [

21] alongside culturally specific modes of cognition and expression. Rather than focusing on the accumulation of information or the exhibition of technological novelty, interpretive practice should prioritize narrative coherence, emotional resonance, and participatory meaning-making. This orientation encourages reflective engagement and empathetic understanding among audiences, fostering protective attitudes toward heritage sites and aligning interpretive practice with broader educational and conservation objectives.

Digital heritage initiatives hold significant potential as instruments for informal learning, public participation, and intercultural dialogue. Policy frameworks should therefore promote the ethical and pedagogically sound deployment of immersive technologies, ensuring that such experiences remain accessible, inclusive, and educationally meaningful. By integrating digital heritage into broader cultural and educational policies, governments and institutions can cultivate digitally mediated spaces that inspire critical awareness, cross-cultural empathy, and collective responsibility for heritage preservation.

5.3. Future Directions

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. Firstly, as a qualitative case study focused on Digital Dunhuang, the generalizability of the findings requires further validation across different types of heritage sites and cultural contexts. Secondly, the study primarily examines on-site immersive experiences, leaving the mechanisms of purely online virtual tours underexplored. Future research should extend these findings to digital-only and hybrid engagement models to provide a more comprehensive understanding of digital heritage interactions.

Looking forward, the evolving landscape of digital technologies offers considerable opportunities for further exploration. The evolving landscape of digital technology presents several promising trajectories for scholarly inquiry. A primary direction lies in leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) [

36] to generate adaptive narrative pathways, enabling dynamic dialogues between visitors and heritage. Future empirical studies are warranted to systematically examine how such AI-mediated storytelling influences cognitive comprehension, emotional engagement, and the development of conservation-oriented behaviors, while also scrutinizing its ethical implications for constructs of authenticity. Concurrently, Extended Reality (XR) technologies—encompassing virtual, augmented, and mixed reality [

37]—offer the capacity to create hybrid experiences that seamlessly blend virtual and physical elements, potentially fostering a state of augmented authenticity. Research could productively investigate how these XR-mediated environments impact visitor perceptions of historical accuracy, depth of emotional immersion, and capacity for reflective learning.

Further on the technological horizon, holographic reconstructions may enable the synchronous recreation of historical scenes, facilitating a shared sense of temporal presence across spatial and chronological divides. Scholarly exploration into the psychological, cultural, and pedagogical effects of such immersive holographic engagements would yield valuable insights. Beyond specific technologies, a critical overarching need exists for the development of robust, systematic evaluation frameworks designed to measure the long-term societal and cultural impacts of digital heritage. These frameworks should incorporate metrics for cognitive gains, emotional resonance, behavioral changes in conservation, and contributions to intercultural understanding.

To ensure the global relevance of these advancements, comparative cross-cultural research is essential to elucidate how diverse sociocultural backgrounds shape the reception of digital heritage. The findings from such studies would be instrumental in designing culturally sensitive digital experiences that resonate with heterogeneous audiences. Finally, the integration of digital heritage as a platform for formal and informal education, community engagement, and cross-generational learning represents a fertile ground for future research. Investigations into the specific roles that schools, universities, and community organizations can play in leveraging digital heritage for social, ethical, and educational outcomes will be crucial for maximizing its public benefit.

In summary, the trajectory of digital heritage is moving from visual immersion towards emotional and spiritual resonance, positioning ancient cultural assets as vital sources for nurturing contemporary societal consciousness. As technologies continue to evolve, digital heritage experiences will not only safeguard the past but also enrich the present and future, offering pathways for cognitive, emotional, and ethical growth across global audiences.

6. Conclusions

This study has illuminated how Digital Dunhuang redefines the relationship between heritage, technology, and human experience. Moving beyond the traditional boundaries of preservation demonstrates that digital interpretation. Rather than replacing this, it regenerates the aura of heritage. Through the integration of Freeman Tilden’s interpretive theory [

21] with Chinese hermeneutic principles, this research has introduced a novel interpretive framework that connects cognition, emotion, and ethical consciousness into a single continuum of engagement.

Three original contributions distinguish this work. Firstly, it conceptualizes digital spiritual heritage as a new paradigm that captures how technology mediates not only knowledge but also empathy and transcendence. Secondly, it establishes a cross-cultural interpretive model that bridges Western interpretive thought and Eastern epistemology, offering a globally adaptable framework for heritage communication. Thirdly, it empirically demonstrates how digital mediation can evoke relational authenticity, reshaping visitors’ understanding from passive observation to participatory stewardship.

At a broader level, this study positions

Digital Dunhuang as a symbol of resilience and intercultural dialogue in a post-pandemic world. Echoing recent insights into how COVID-19 accelerated digital transformation across the heritage sector [

9,

10,

11], it shows that the fusion of digital innovation and cultural interpretation can sustain connectivity even amid disruption.

Ultimately, Digital Dunhuang points toward a future where technology becomes a vessel of compassion and cultural continuity—a bridge that unites art, philosophy, and humanity across time and space. As digital heritage enters this “post-authenticity” era, it offers not only a means to preserve the past but also an invitation to re-imagine how we feel, learn, and care together in the shared pursuit of cultural wisdom.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B. and J.B.; methodology, H.B.; formal analysis, H.B.; investigation, H.B.; resources, writing—original draft preparation, H.B. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, J.B. and H.B.; project administration, J.B.; funding acquisition, H.B. and J.B. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Jonathan Bowen is funded by the UK Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS).

Acknowledgements

The Dunhung Academy provided support and travel funding that enabled this research. Jonathan Bowen received additional support and funding from Museophile Limited. All figures in this paper are by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Agnew, N.; Demas, M. Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road. Getty Conservation Institute, 2010.

- Brandi, C. Teoria del Restauro. Einaudi, 1963.

- Leask, A. Progress in visitor attraction research: Towards more effective management. Tourism Management 2010, 31, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Reichel, A.; Biran, A. Heritage site management: Motivations and expectations. Annals of Tourism Research 2003, 30, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F.; Bruno, S.; De Sensi, G.; Luchi, M. L.; Mancuso, S.; Muzzupappa, M. From 3D reconstruction to virtual reality: A complete methodology for digital archaeological exhibition. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2010, 11, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, M.; Evans, D. Reimagining Angkor: The importance of mapping. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 2015, 373, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huvila, I.; Börjesson, L.; Dell’Unto, N.; Löwenborg, D.; Petersson, B.; Stenborg, P. Archaeological information work and the digital turn. In Archaeology and Archaeological Information in the Digital Society. Routledge, 2018. pp. 143–158.

- UNESCO. Ethics of Cultural Heritage. UNESCO, 2021. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/ethics-cultural-heritage (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Han, M. Digital exhibition of intangible heritage and the role of digital tools in the COVID-19 era. Heritage 2022, 5, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D. H. R. Exhibiting the heritage of COVID-19—A conversation with curators and conservators. Heritage 2023, 6, 5634–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volanakis, A. Assessing the long-COVID impact on heritage organisations. Heritage 2024, 7, 3126–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Aesthetic interpretation in Digital Dunhuang [In Chinese]. Dunhuang Research 2019, 175, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccardi, E. (Ed.) Heritage and Social Media: Understanding heritage in a participatory culture. Routledge, 2012.

- Parry, R. Recoding the Museum: Digital heritage and the technologies of change. Routledge, 2007.

- Avrami, E.; Macdonald, S.; Mason, R.; Myers, D. Values in Heritage Management: Emerging approaches and research directions. Getty Conservation Institute, 2019.

- Europeana. Europeana Strategy 2020. Europeana Foundation, 2016

. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/post/europeana-business-plan-2016 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- European Commission. Independent evaluation of Europeana. Publications Office of the European Union, 2018

. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1f4c6579-33d2-11e8-b5fe-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Simon, N. The Participatory Museum. Museum 2.0, 2010

. Available online: https://www.participatorymuseum.org (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Frisch, M. A Shared Authority: Essays on the craft and meaning of oral and public history. State University of New York Press, 1990.

- Benjamin, W. The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. In H. Arendt, Ed., Illuminations (H. Zohn, Trans., pp. 217–251). Schocken Books, 1969. (Original work published 1936.

- Tilden, F. Interpreting our Heritage, 4th edition. The University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

- Ham, S. H. Interpretation: Making a Difference on Purpose. Fulcrum Publishing, 2013.

- Bolter, J. D.; Grusin, R. Remediation: Understanding new media. The MIT Press, 1999.

- McLuhan, M. Understanding media: The extensions of man. McGraw-Hill, 1964.

- Lister, M.; Dovey, J.; Giddings, S.; Grant, I.; Kelly, K. New Media: A Critical Introduction, 2nd edition. Routledge, 2009.

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J. P.

Museums and Digital Culture: From Reality to Digitality in the Age of COVID-19

. Heritage 2022, 5, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R. The trusted art object: A new authenticity paradigm for the museum. In R. Parry, Ed., Museum Ontologies, pp. 145–160). Routledge, 2019.

- Jones, S. Negotiating authentic objects and authentic selves: Beyond the deconstruction of authenticity. Journal of Material Culture 2010, 15, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R. How museums made and remade their digital user. In T. Giannini; J. P. Bowen, Eds., Museums and Digital Culture: New perspectives and research, chapter 15, pp. 275–293. Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2019 International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Gadamer, H.-G. Truth and Method (J. Weinsheimer; D. G. Marshall, Trans.). Continuum, 2004. (Original work published 1960.

- British Sociological Association. BSA Statement of Ethical Practice. British Sociological Association, 2017

. Available online: https://www.britsoc.co.uk/media/24310/bsa_statement_of_ethical_practice.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. K. The Research Act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Routledge, 2017.

- Geertz, C. Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays, pp. 3–30. Basic Books, 1973.

- Lincoln, Y. S.; Guba, E. G. Naturalistic Inquiry. SAGE Publications, 1985.

- Bowen, J. P.; Digital cultural heritage and artificial intelligence: Whence and whither? In Dunhuang Forum: Academic Symposium on Digital-Intelligent Technologies for Cultural Heritages, pp. 204–213. Dunhuang Academy, September 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jonathan-Bowen-2/publication/396046180 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Bowen, J. P. The Metaverse and Expo 2020: VR. AR, MR, and XR. In T. Giannini; J. P. Bowen, Eds., The Arts and Computational Culture: Real and Virtual Worlds, chapter 12, pp. 299–317. Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Visitors experiencing immersive virtual scenes of Dunhuang music and artistic sculptures.

Figure 1.

Visitors experiencing immersive virtual scenes of Dunhuang music and artistic sculptures.

Figure 2.

Visitors exploring virtual Dunhuang scenes, including Flying Apsaras and Buddha statues.

Figure 2.

Visitors exploring virtual Dunhuang scenes, including Flying Apsaras and Buddha statues.

Figure 3.

Visitors exploring virtual Dunhuang scenes, including Flying Apsaras and Buddha statues.

Figure 3.

Visitors exploring virtual Dunhuang scenes, including Flying Apsaras and Buddha statues.

Figure 4.

A visitor engaging with the 3D VR interactive experience at the Mogao Caves, Dunhuang.

Figure 4.

A visitor engaging with the 3D VR interactive experience at the Mogao Caves, Dunhuang.

Figure 5.

Silk Road, Flower Rain, a large-scale dance drama by Gansu Dunhuang Art Theatre, brings Dunhuang

murals to life on stage, blending regional folk songs and dances to celebrate the richness of Dunhuang culture

and the ancient Silk Road.

Figure 5.

Silk Road, Flower Rain, a large-scale dance drama by Gansu Dunhuang Art Theatre, brings Dunhuang

murals to life on stage, blending regional folk songs and dances to celebrate the richness of Dunhuang culture

and the ancient Silk Road.

Figure 6.

Music for the digital dome film “Dreamlike Buddhist Palace” by Zhang Qianyi blends ancient Dunhuang melodies with modern symphonic arrangements and surround sound, creating an immersive audiovisual experience. It incorporates sampled sounds of restored Dunhuang instruments, with some melodies inspired by Tang dynasty musical manuscripts from the Dunhuang Library Cave.

Figure 6.

Music for the digital dome film “Dreamlike Buddhist Palace” by Zhang Qianyi blends ancient Dunhuang melodies with modern symphonic arrangements and surround sound, creating an immersive audiovisual experience. It incorporates sampled sounds of restored Dunhuang instruments, with some melodies inspired by Tang dynasty musical manuscripts from the Dunhuang Library Cave.

Figure 7.

A robot used for mural scanning and digital restoration, equipped with high-precision sensors and imaging technology for non-contact analysis, documentation, and preservation of fragile murals.

Figure 7.

A robot used for mural scanning and digital restoration, equipped with high-precision sensors and imaging technology for non-contact analysis, documentation, and preservation of fragile murals.

Figure 8.

Interior of Digital Cave 285, Mogao Grottoes, featuring murals and Buddha statues from the Western Wei Dynasty (538–539 A.D.), exemplifying early medieval Chinese Buddhist art.

Figure 8.

Interior of Digital Cave 285, Mogao Grottoes, featuring murals and Buddha statues from the Western Wei Dynasty (538–539 A.D.), exemplifying early medieval Chinese Buddhist art.

Figure 9.

The “Ten-Thousand-People Starry Sky Concert” at Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Moon Spring Scenic Area uses drones, lighting, and sound to project Flying Apsaras, the Mogao Caves pagoda, and desert camels onto the dunes, creating an immersive reinterpretation of Dunhuang murals for over ten thousand nightly participants.

Figure 9.

The “Ten-Thousand-People Starry Sky Concert” at Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Moon Spring Scenic Area uses drones, lighting, and sound to project Flying Apsaras, the Mogao Caves pagoda, and desert camels onto the dunes, creating an immersive reinterpretation of Dunhuang murals for over ten thousand nightly participants.

Table 1.

Digital Interpretive Hierarchy Model.

Table 1.

Digital Interpretive Hierarchy Model.

| Tilden’s Principle |

Digital Dunhuang Mechanism |

Experiential Level (From the Tangible to the Emotional) |

| 1. Relation (Connect the subject to the visitor’s personal experience) |

Interactive virtual design (e.g., deity adornment) and emotional storytelling (e.g., historical figures) link millennia-old cultural heritage with visitors’ modern sensibilities and lived experience. |

Material → Rational & Emotional fusion: establishes initial empathy through connecting tangible objects with personal meaning. |

| 2. Revelation (Reveal meaning rather than state facts) |

High-resolution zooming, animated sequences (e.g., pigment layering, painting techniques), and cross-media narratives visualize the invisible—Buddhist philosophy, history, and social context. |

From Material to Rational: visitors move from perceiving the “object” to understanding the “principle” embedded within it. |

| 3. Provocation (Inspire curiosity and reflection) |

Dome-screen films and interactive installations (e.g., digital mural restoration) foster exploratory learning environments, provoking reflection on creation, decline, and preservation. |

From Rational to Emotional: cognitive insight transforms into affective identification and conservation awareness. |

| 4. The Art of Interpretation (Interpretation as creative art) |

The aesthetic sophistication of digital media—grand narrative dome films, digitally reconstructed music, and light simulations—creates an artistic interpretive language. |

Sensory Level: activates embodied perception, allowing visitors to be “within the object.” |

| 5. Wholeness (The whole rather than the part) |

Integrated multimedia (film + music + VR + text) weaves scattered caves and artifacts into a coherent Silk Road narrative. |

Comprehensive Cognition: synthesizes fragmented “objects” and “principles” into a holistic cultural narrative. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).