1. Introduction

Infectious Bronchitis Virus

(IBV) is a highly contagious avian coronavirus that affects the respiratory, reproductive, and renal systems of chickens, causing major economic losses to the poultry industry worldwide [

1]. The disease can impact birds of all ages and production types, leading to poor growth, reduced egg production and quality, and greater vulnerability to secondary bacterial infections [

2]. IBV belongs to the genus

Gammacoronavirus within the family

Coronaviridae. Its genome consists of a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA that encodes four major structural proteins: the spike (

S), envelope (

E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (

N) proteins. The spike glycoprotein (especially its S1 subunit) is a key target for neutralizing antibodies and plays a central role in viral attachment and tissue tropism [

3].

Due to its high genetic and antigenic diversity, IBV remains endemic and a major threat to the poultry industry worldwide even with extensive vaccination regimes [

4]. The intrinsic and frequent virus mutations, especially in the spike protein gene along with the recombination events between different IBV strains, gives rise to various genotypes and serotypes that might provide limited cross-protection [

5,

6,

7]. The Massachusetts serotype strain H120 is one of the most widely used live-attenuated vaccines and serves as the foundation of many vaccination schedules [

8,

9,

10]. However, it provides variable degrees of protection against heterologous and newly emerging variants, such as QX (

G1-19) and variant-2 (

GI-23) strains, which are becoming increasingly prevalent in the Middle East and Asia [

11,

12,

13,

14]. This ongoing emergence of diverse field strains underscores the need for more adaptable vaccine platforms that can be rapidly updated and precisely engineered.

Recent advances in reverse genetics have transformed the study of RNA viruses, enabling complete genome reconstruction and the creation of recombinant viruses with defined genetic compositions [

15,

16]. Among these techniques, Golden Gate Assembly (

GGA) offers a fast, cost-effective, and highly accurate approach for assembling full-length viral genomes from multiple synthetic fragments using type IIS restriction enzymes [

17,

18]. This method has proven valuable for studying viral gene function, understanding pathogenesis, and designing improved vaccines [

19,

20]. While reverse genetics systems have been developed for several IBV strains [

21,

22,

23], to date, no studies have used Golden Gate Assembly to reconstruct the classical H120 vaccine strain or to evaluate its biological and immunological properties in chickens.

In this study, we constructed a recombinant H120 strain of IBV (rH120) using a Golden Gate Assembly–based reverse genetics system. We examined its replication and growth characteristics in embryonated chicken eggs and evaluated its immunogenicity in broiler chickens. The successful rescue and evaluation of rH120 demonstrate the reliability of Golden Gate Assembly for generating genetically defined IBV viruses and highlight its potential as a platform for developing next-generation, genotype-matched vaccines to better control infectious bronchitis in poultry.

2. Materials and Methods

The Scientific Research Ethics Committee of Ahliyya Amman University reviewed and approved all procedures carried out in the current study (AUP: AAU/03/02/2025-2026).

2.1. Virus, Cells, and Eggs

The IBV H120 strain was used as the parental genetic backbone. The complete genome of this virus was obtained from GenBank (accession number FJ807652). Twelve genomic fragments covering the entire viral genome were synthesized and assembled using Golden Gate Assembly and rescued using chicken embryo fibroblast cells (CEFs) and embryonated chicken eggs at 9-days-of-age. A commercial H120 vaccine was used in both growth kinetics and chicken infection experiments. Primary chicken embryo fibroblasts obtained from 9-day-old chicken embryos and BHK-21 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) media (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cytiva, Austria), 100 units mL−1 penicillin, and 100 µg mL−1 streptomycin (Euroclone, Italy) and kept at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator.

2.2. Design of Recombinant H120 by Golden Gate Assembly Strategy-Based Reverse Genetics

Using NEBridge SplitSet® Tools available at the New England Biolabs website and the Golden Gate Assembly tool in the SnapGene software, the entire H120 genome was split into 12 fragments of various sizes. Fragment 10 was designed to have the full length of the coding sequence of the spike gene. Special features were included in the design of those 12 fragments to ensure efficient transcription of the rH120 genome. Fragment 1 contains the T7 promoter sequence. In fragment 12, a 30-nucleotide poly (A) tail was added directly after the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). This was followed by the insertion of a Hepatitis Delta Virus (HDV) ribozyme sequence and then a T7 transcription terminator positioned downstream of the ribozyme. To complete the design, fusion sites were added to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the construct, allowing it to form a circular assembly. GGA employs Type IIS restriction enzymes, such as BsmBI (used in our strategy), which cleave outside their recognition sequences, enabling multiple DNA fragments to be assembled efficiently in a single reaction. Because the H120 genome contains four internal BsmBI recognition sites, these sites were removed by introducing silent point mutations at nucleotide positions 5159 (C→T), 7363 (G→C), 15461 (C→G), and 26079 (C→G). These substitutions did not alter the amino acid sequence and were designed according to the chicken codon usage.

All 12 fragments of the IBV H120 strain were chemically synthesized and cloned into pUC57-mini plasmids by GenScript (USA). The plasmids were produced at an industrial scale and supplied as high-purity, endotoxin-free DNA preparations.

2.3. Golden Gate Assembly of IBV H120 Strain, Transfection, and Virus Rescue

All 12 plasmids of the 12 fragments were used in the GGA reaction. The GGA reaction was performed in a final volume of 20 μL, containing 3 nM of each DNA fragment (measured by Qubit 4), and 2 μL of the NEBridge Golden Gate Assembly Kit (BsmBI-v2) (NEB #E1602) (New England Biolabs, USA) in 1× T4 DNA Ligase Reaction Buffer. The reaction mixtures were subjected to 90 thermal cycles, alternating between 37 °C and 16 °C for 5 minutes each and followed by a final incubation at 60 °C for 5 minutes. The assembled products were then stored at −20 °C until their use in the virus recovery experiments. A total of 90 cycles was applied to maximize the yield of the full-length assembled construct. For transfection and virus rescue, CEFs were seeded in six-well plates and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cytiva, Austria), 100 U mL−1 penicillin, and 100 µg mL⁻¹ streptomycin (Euroclone, Italy). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂ until they reached 70–80% confluence. The monolayers were then infected with vaccinia virus at a dose of 103.7 TCID₅₀ per well and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ for 1.5 hours to allow viral adsorption.

After incubation, the inoculum was removed and replaced with Opti-MEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) containing 12 µL of Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 20 µL of the GGA reaction mixture, and 2.5 µL of the helper plasmid carrying the N gene.

For transfection, two solutions were prepared separately:Solution A: 20 µL of the GGA reaction mixture and 2.5 µL of the N gene helper plasmid were diluted in 1.5 mL of Opti-MEM.Solution B: 12 µL of Lipofectamine 2000 was diluted in 1.5 mL of Opti-MEM.

Both solutions were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes, combined, and then left for an additional 30 minutes to allow complex formation. Meanwhile, vaccinia virus–infected cells were washed twice with Opti-MEM to remove residual inoculum.

Next, 3 mL of the transfection mixture was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ for 90 minutes. The mixture was then replaced with DMEM and the cells further incubated for 48 hours under the same conditions. Following incubation, the cells underwent three freeze–thaw cycles (−80 °C / 37 °C) and the harvested supernatant was stored at −20 °C.

A 500 µL aliquot of the harvested material was subsequently inoculated into 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs for three blind passages. Finally, the allantoic fluid was collected and stored at −20 °C for further analyses.

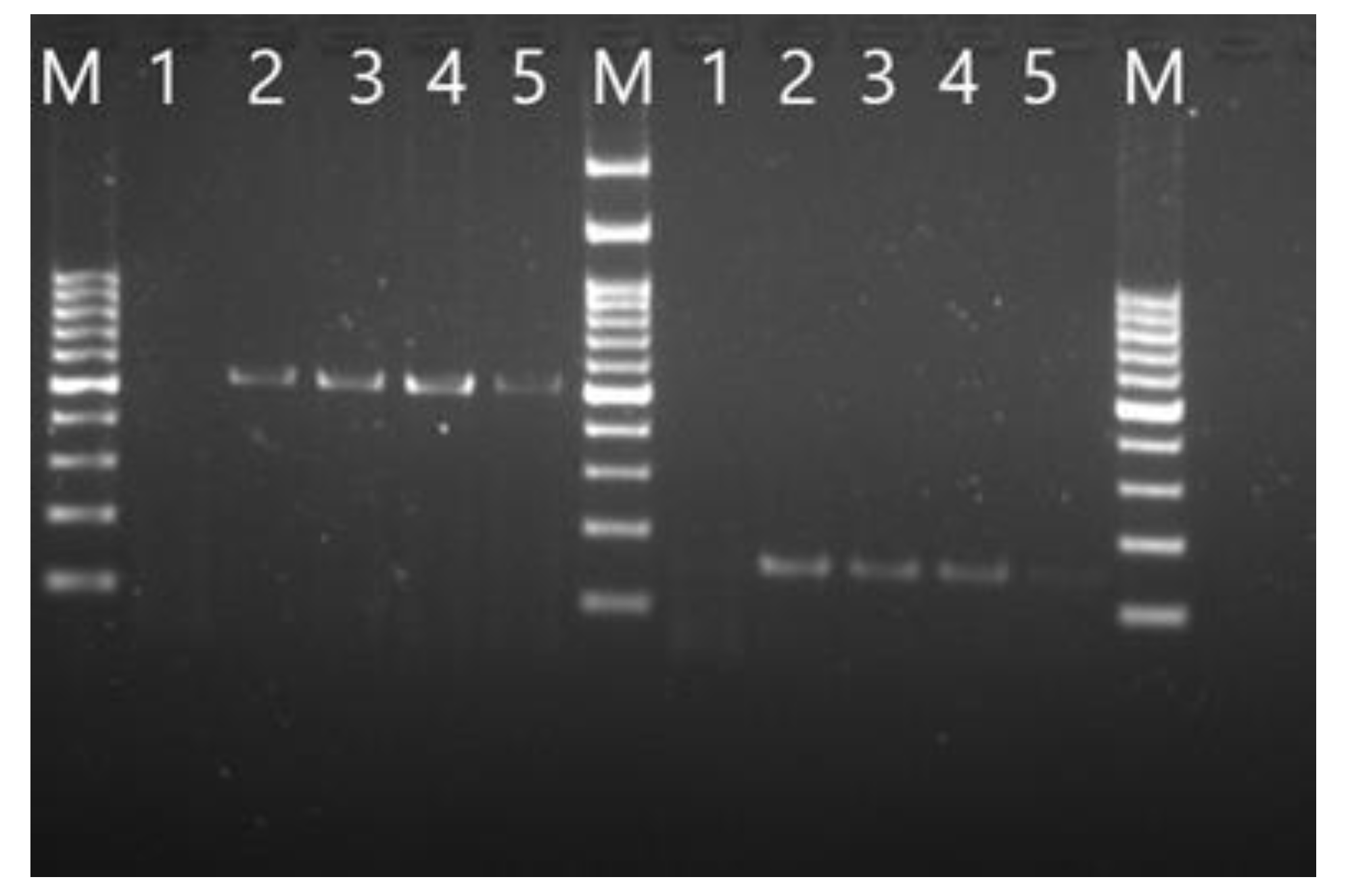

2.4. Validation of GGA Reaction

Four PCR reactions were performed to assess the success of the GGA reaction. The first and second PCR protocols amplify 518 bp and 151 bp products, spanning the region fragments 1, 2 and 3, 5, and 6, respectively. The third PCR reaction was obtained from [

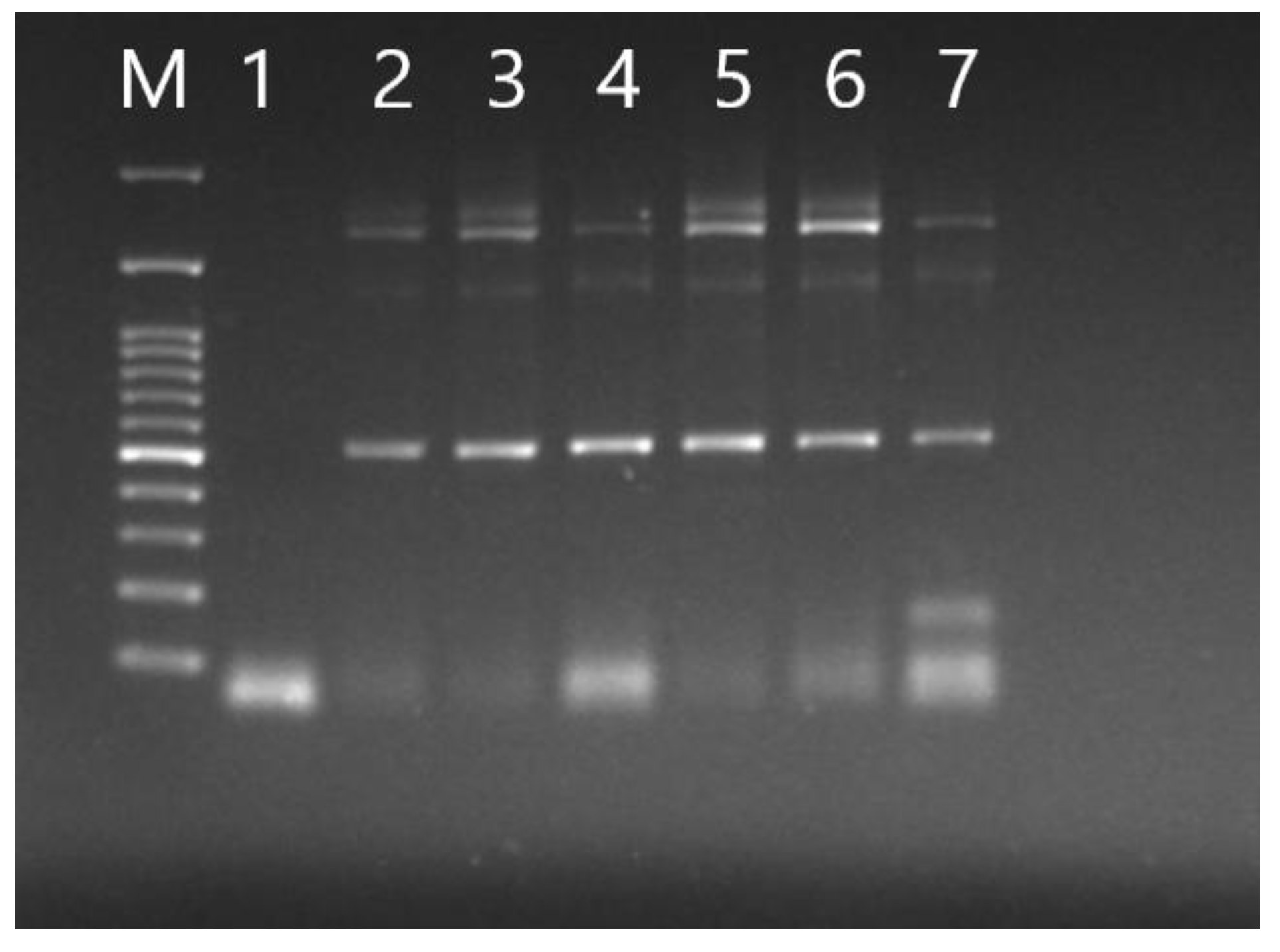

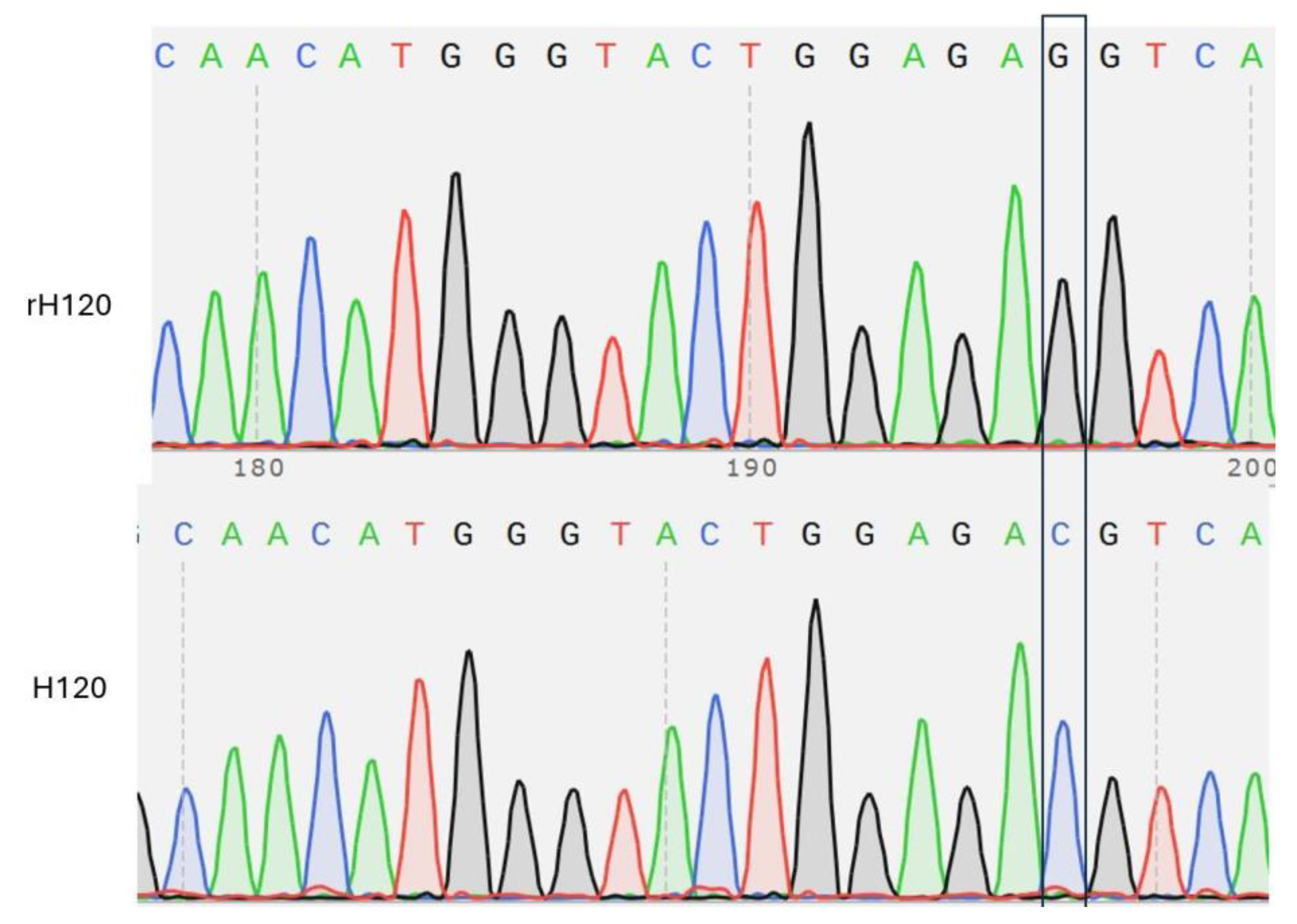

24] to detect the production of gene 5 and gene 7 from the subgenomic RNA of rH120 virus (producing two products at 500 bp and 2000 bp, respectively). The fourth PCR reaction was designed to amplify a 366 bp region in the N gene that has the silent mutation of C to G at position 26079.

2.4.1. Viral RNA Extraction and Complementary DNA Synthesis

Viral RNA was extracted using Quick-RNA Viral Kit (Zymo Research, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. 200 µL of the allantoic fluid were mixed with 200µL of DNA/RNA shield; then, 800 µL of viral RNA buffer was added and the mixture transferred into the zymo-spin IC Column. Following centrifugation for 2 min, 500 µL of viral wash buffer was followed by centrifugation for 1 min. This step was repeated twice before washing in 500µL ethanol (100%) and 1 min centrifugation. RNA was eluted by adding 15 µL of DNase/RNase-free water directly in the column matrix, which was centrifuged again for 30 s and stored at −80 °C. The cDNA was then synthesized using the All-in-One 5x RT Master Mix kit (abmgood, Richmond, Canada) using the following steps. 4µL of All-in-One 5x RT Master Mix was mixed with 2 µg of the extracted RNA and 14 µL of nuclease-free water (NFW). The reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 15 min followed by 60 °C for 10 min. The mixture was stored at −20 °C.

2.4.2. Conventional PCR Protocols

The primer sequences for the first and second PCR protocols, which span fragments 1, 2 and 3, 5, and 6, respectively, are: 1F: 5’-TGCACCATCTTGAGTTGCCTA-3’, 3R: 5’-ATTGCGGCATAAAGCCAT-3-, 5F: 5’-ACTGCTTGTTTTGCCGTGTC-3’, and 6R: 5’-CCCAGTCTGCAGATTACGGT-3’-. 10 pmol from each primer was mixed with 10 µL of Taq2x PCR Master Mix, and 2 µL of the cDNA sample, and diluted by nuclease-free water up to 20 µL . The PCR thermal conditions were 95 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final cycle of 72 °C for 2 min. For the third PCR reaction, primer sequences were obtained from [

24] and the PCR thermal conditions were as mentioned above. For the fourth PCR, the primer sequences are N gene sequence F: 5’-CTATTGCACTAGCCTTGCGC-3’ and N gene sequence R: 5’-TTCTCTAACTCTATACTAGCC -3’. 10 pmol from each primer was mixed with 10 µL Taq2x PCR Master Mix and 2µL of the cDNA sample and diluted by nuclease-free water up to 20 µL. The PCR thermal conditions were 95 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 62 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final cycle of 72 °C for 2 min. After completion of the PCR reactions, the products were run in a 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis set-up and images taken. The products of the fourth PCR reaction were sent for Sanger sequencing at Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea). Sequences were viewed and edited using Finch TV software.

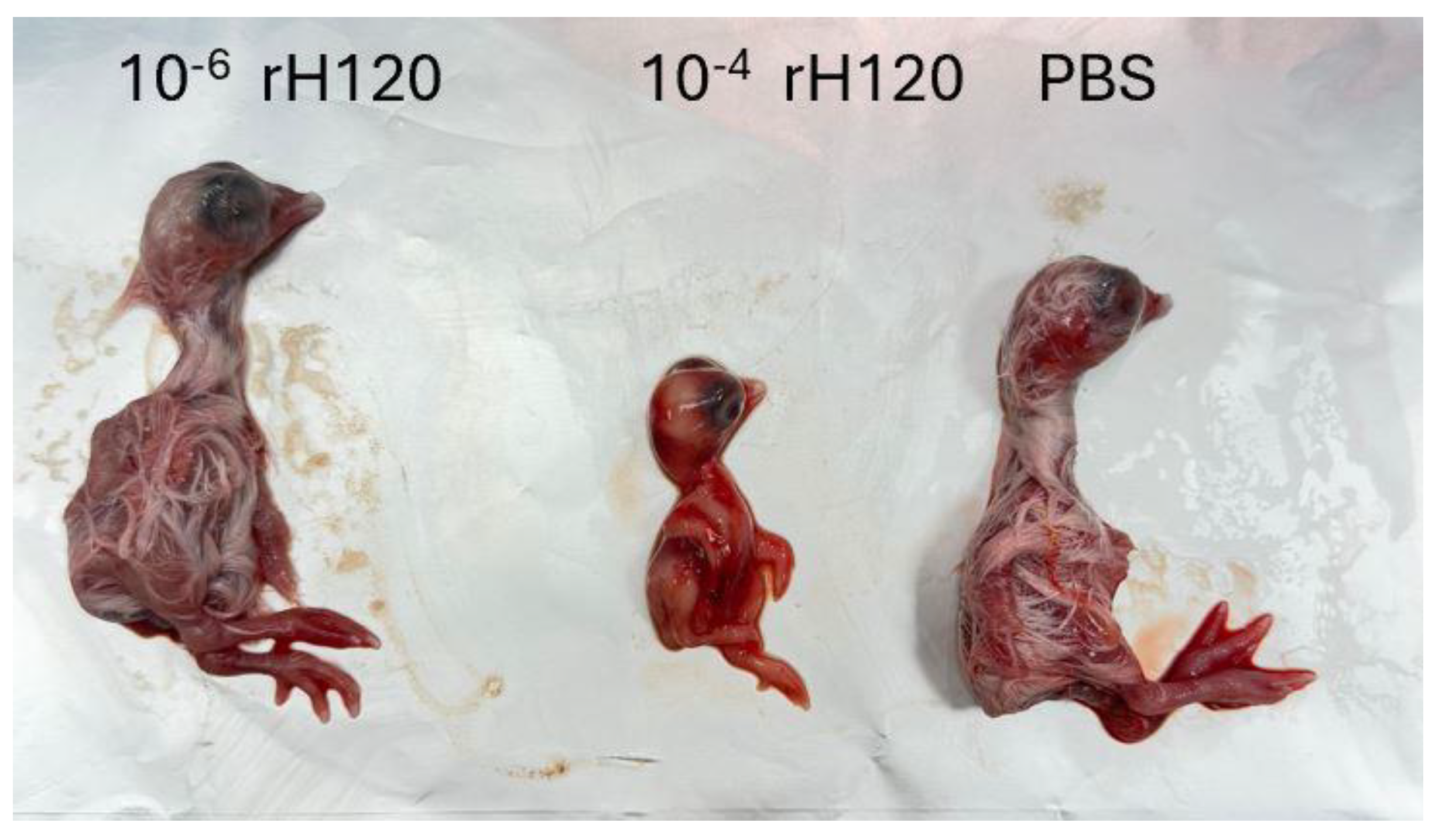

2.4.2. Recombinant H120 (rH120) Viral Propagation and Titration

To determine the virus titer, rH120 was inoculated in 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs via the allantoic cavity and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. After chilling at 4 °C overnight, the infected allantoic fluid was harvested. Viral titers were then determined by inoculating 10-fold serial dilutions (10−1 to 10−6) of the virus into five 9-day-old embryonated eggs per dilution via the allantoic cavity. Inoculated eggs were monitored for embryo mortality for 7 days at 37 °C and the 50% egg infectious dose (EID₅₀/mL) was calculated using the Reed–Muench method.

2.5. Growth Kinetics of Recombinant H120 in Embryonated Chicken Eggs

Both original H120 and rH20 viruses were inoculated at a titer of 103 EID50 into the allantoic cavity of 9-day embryonated chicken eggs. Allantoic fluid was harvested from five eggs inoculated with each virus at 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours. Growth kinetics were assessed using RT-qPCR and expressed as log10 of RNA copies/reaction.

2.5.1. Reverse Transcriptase-Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Viral RNA was extracted from the allantoic fluid using the Quick-RNA Viral Kit (Zymo Research, USA) as mentioned above. RNA concentration was measured using a BioTek spectrophotometer and the concentrations of all samples were subsequently normalized at 100 ng/µL. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the GoScript™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega, USA; Cat. No. A5003). For each reaction, two separate mixtures were prepared as follows:

Solution A: Experimental RNA (100 ng per reaction) was mixed with 0.5 µL of Oligo(dT)₁₈ primer and 0.5 µL of random primer. Nuclease-free water was added to a final volume of 5 µL. The mixture was incubated at 70 °C for 5 min, then immediately placed on ice for 5 min where it remained until use in the reverse transcription reaction.

Solution B: In a separate tube, nuclease-free water was added to achieve a total reaction volume of 15 µL along with 4 µL of GoScript™ 5× Reaction Buffer, 2 µL of MgCl₂, 1 µL of PCR Nucleotide Mix (0.5 mM of each dNTP), and 1 µL of GoScript™ Reverse Transcriptase. All components were gently mixed in the order listed and kept on ice until combined with Solution A. Reverse transcription was performed under the following thermal conditions: 25 °C for 5 min, 42 °C for 60 min, and 70 °C for 15 min to inactivate the enzyme. The resulting cDNA was stored at −20 °C for further analyses.

For RT-qPCR, a standard curve was generated by serial dilution of a plasmid containing a fragment of the N gene cloned in pMG plasmid (Macrogen, South Korea). The primer sequences used in the qPCR were NqPCR F: 5’-CCTGGAAACGAACGGTAGAC-3’ and NqPCR R: 5’-CTGGCATCTTTATACCTACTCTAAACT-3’. 10 pmol from each primer was mixed with 10 µL of BlasTaq2x qPCR Master Mix and 2 µL of the cDNA sample and diluted by nuclease-free water up to 20 µL. The qPCR conditions were 95 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. The qPCR was run in Rotor-Gene Q Thermal Cycler (QIAGEN, Germany). The results were expressed as log10 of RNA copies/reaction.

2.6. Infection of Broiler Chicken with Recombinant rH120 Virus

Three groups of broiler chickens at 21-days-of-age were housed in biosafety level 3 isolators. Two groups were inoculated by ocular route with 105 EID50 of either rH120 or H120 virus. The third group was left as a control group and inoculated with PBS only. On days 21, 28, and 35 (0, 7, and 14 day post-infection (dpi)), blood samples were collected and serum separated and stored at −20 °C for use in the indirect ID Screen® Infectious Bronchitis ELISA kit to detect antibodies against IBV (ID vet, France). The ELISA procedure was done according to the manufacturer’s manual, and the results were expressed as optical densities (OD) at 450 nm. To evaluate the shedding of the IBV viruses (rH120 or H120), throat and cloacal swabs were collected in RNA shield solution at 24, 27, and 31-days-of-age (3, 6, and 10 dpi). RT-qPCR was performed as mentioned in the growth kinetics section.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Results from the throat and cloacal swabs were analyzed to compare viral RNA shedding between chickens vaccinated with the H120 and rH120 strains at 3, 6, and 10 dpi. Viral RNA copy numbers were converted to their log₁₀ values before analysis to stabilize the variance and improve normality. Results of the ELISA at 0,7 and 10 dpi were expressed as optical densities at 450 nm. Comparisons between the two groups at each time point were made using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction to account for possible differences in variance between groups.

A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Levels of significance are indicated in the figures as follows: p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, p < 0.0001 (****), and p ≥ 0.05 (ns, not significant).

3. Results

3.1. Construction and Rescue of Recombinant H120 (rH120) Virus

The full-length genome of the IBV H120 strain was successfully reconstructed using a GGA strategy with an assembly fidelity of 97% as calculated by the GGA function in SnapGene software. All 12 designed fragments, including a modified spike gene encoded entirely in fragment 10, were efficiently synthesized and assembled into a circular construct. Silent mutations were introduced to eliminate internal BsmBI restriction sites without altering the amino acid sequence.

Following transfection of vaccinia virus-infected CEF cells with the GGA product and helper plasmid encoding the N gene, cytopathic effects were observed after 48 hours. The resulting lysates were passaged in 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs. After three blind passages, viable virus was successfully recovered in the allantoic fluid, confirming the rescue of the recombinant rH120 virus.

3.2. Validation of Viral Genome Assembly

Multiple PCR reactions confirmed correct assembly and transcription of the recombinant virus. Two PCR reactions targeting regions spanning fragments 1, 2, 3, and 5, 6 produced expected amplicons of 518 bp and 151 bp, respectively, as shown in

Figure 1. Subgenomic mRNA of gene 5 and gene 7 was also detected in infected samples, yielding 500 bp and 2,000 bp products, respectively (

Figure 2). A fourth PCR targeting the N gene confirmed the presence of the engineered C→G mutation at position 26079. Sanger sequencing of the amplified region validated this mutation, confirming the identity of the recombinant virus (

Figure 3).

3.3. Propagation and Titration of rH120 Virus

The rescued rH120 virus propagated efficiently in embryonated chicken eggs. Following inoculation and incubation, allantoic fluid was collected, and viral titers were calculated using the Reed–Muench method (

Figure 4). The mean titer across experiments reached approximately 10

5 EID₅₀/mL, demonstrating robust replication comparable to the commercial H120 strain.

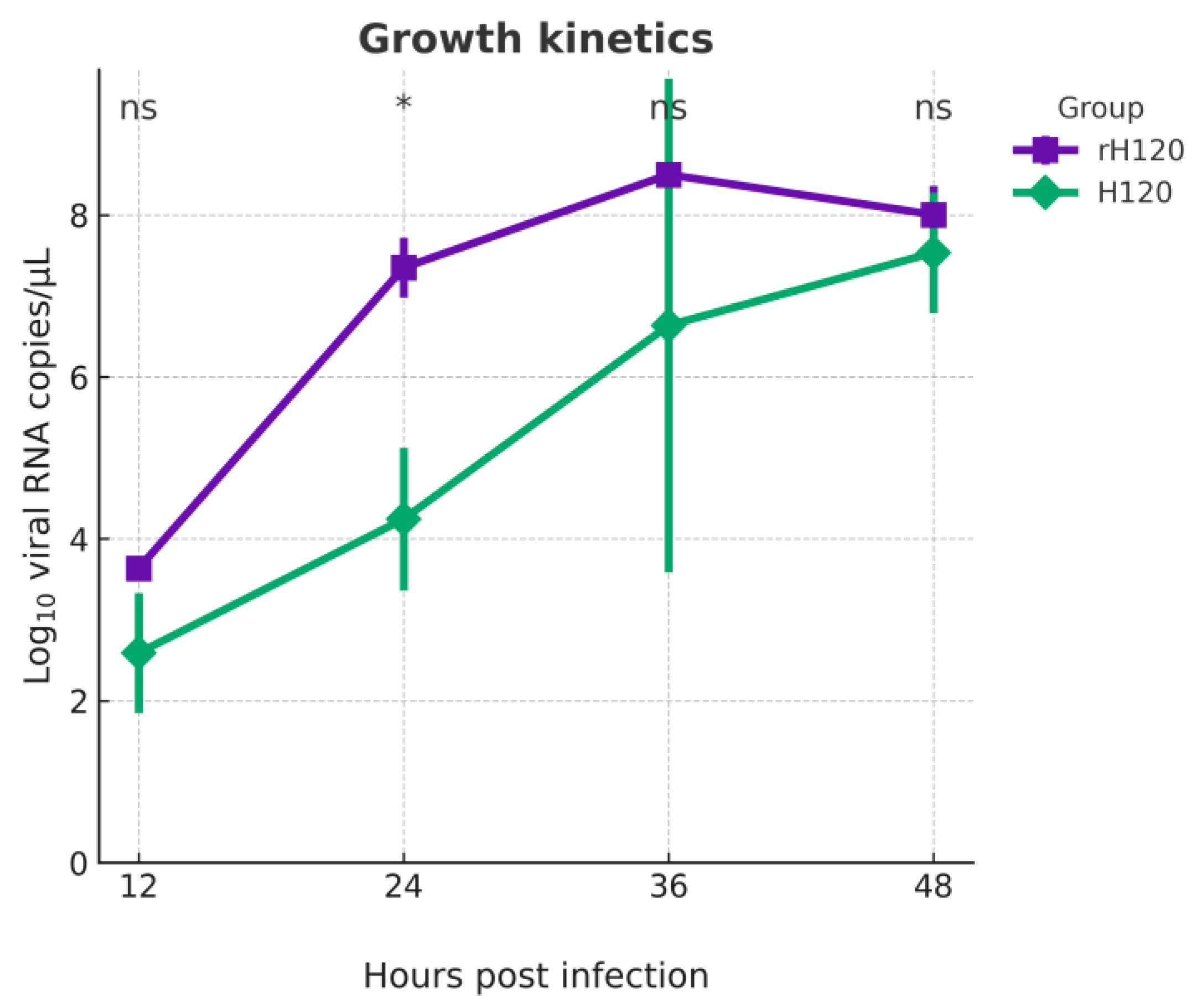

3.4. Growth Kinetics in Embryonated Chicken Eggs

To make sure that the generated recombinant virus has the ability to replicate efficiently in chicken eggs, both rH120 and H120 viruses were inoculated into 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs with 10³ EID₅₀. Using RT-qPCR, the viral RNA amounts were expressed as log₁₀ viral RNA copies/mL and determined at 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours post-inoculation (

Figure 5). Growth kinetics measured as the viral RNA levels for both viruses were very similar at almost all time points, with a slight significant increase for the rH120 at 24 hours (

p < 0.05). Both viruses reached their peaks level at 36 hours after inoculation. The growth kinetics experiment clearly shows that rH120 and H120 have similar replication kinetics in embryonated chicken eggs as in the original H120 virus.

3.5. In vivo Infection and Immune Response in Broiler Chickens

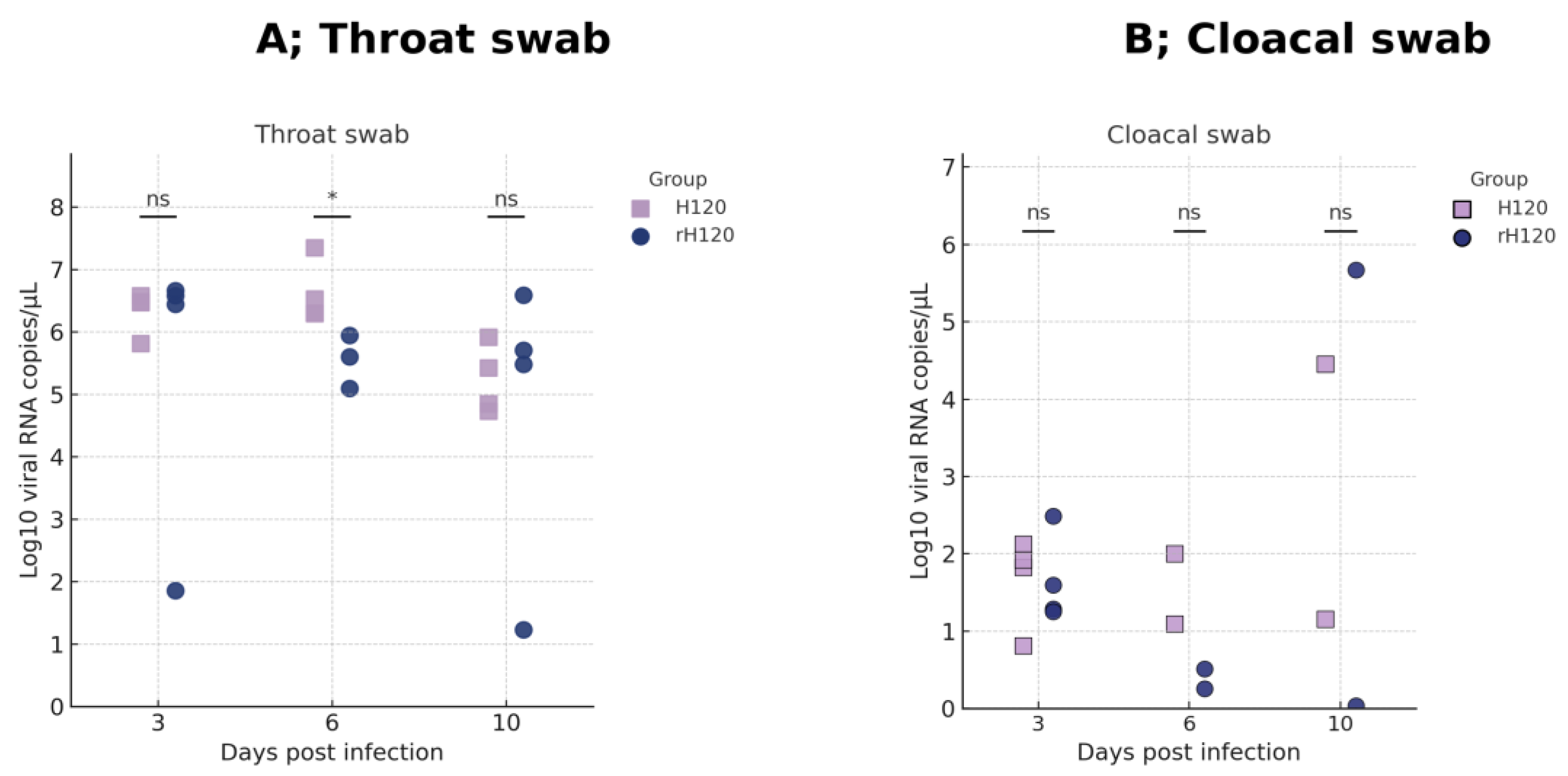

Three groups of broiler chickens at 21-days-of-age were inoculated with either rH120, H120, or PBS. This experiment was designed to check the

in vivo viral replication (measured by viral shedding) and the ability of the rH120 and H120 to induce humoral immune response (as measured by IBV-specific antibody titer). To assess viral shedding, throat and cloacal swabs were collected at 3, 6, and 10 dpi and viral RNA measured by RT-qPCR (

Figure 6). Both rH120 and H120 groups exhibited similar shedding profiles.

In throat swabs, both viruses showed comparable levels of viral RNA at 3 and 6 dpi followed by a marked decline at 10 dpi. In cloacal swabs, four samples were collected at each time point. At 3 dpi, all four swabs tested positive for viral RNA in both groups, whereas at 6 dpi and 10 dpi, only two of four swabs yielded a detectable viral titer. Overall, viral shedding was consistently higher through the respiratory route than through the cloacal route. No viral RNA was detected in the negative control group. All viral RNA quantities are expressed as log₁₀ viral RNA copies/mL as determined by RT-qPCR.

(A) Throat swabs: Both groups showed detectable viral RNA beginning at 3 days post-infection (dpi). The viral load peaked at 6 dpi, where birds inoculated with the recombinant rH120 (blue circles) had significantly higher RNA copies compared to those infected with the original H120 strain (purple squares). By 10 dpi, viral levels declined in both groups, with no significant differences.

(B) Cloacal swabs: Intermittent viral shedding was detected from 3 to 10 dpi in both groups, but the levels were generally lower than those observed in the throat samples, and no significant differences were found between rH120 and H120. (*): p < 0.05 (statistically significant).

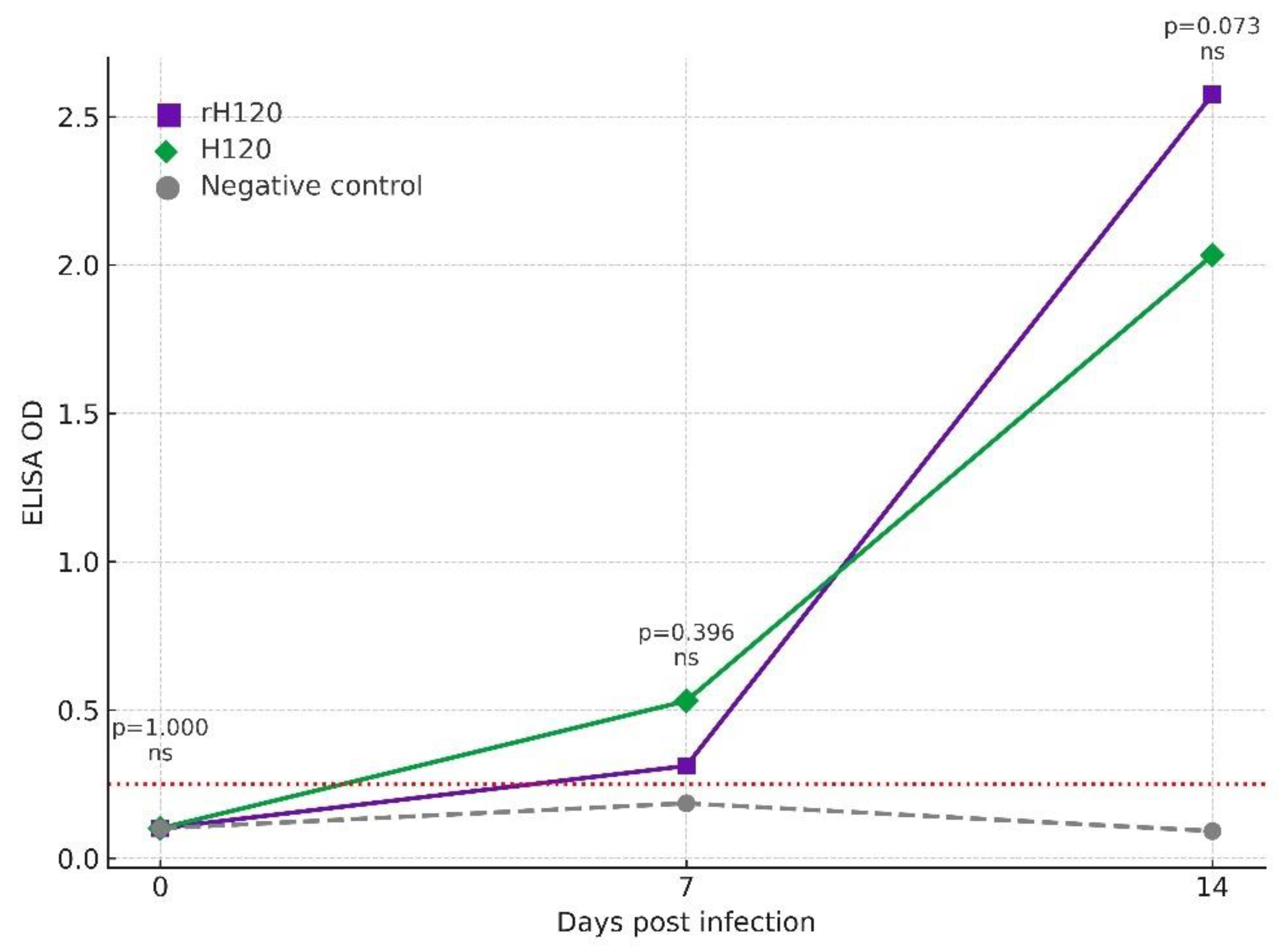

ELISA testing revealed a strong serological response in both groups (rH120 and H120) with antibody levels significantly increasing at 7 and 14 days post-infection compared to the control group. No antibodies were detected in PBS-inoculated birds (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The aims of this study were to (1) reconstruct the full-length genome of the infectious bronchitis virus H120 strain using a GGA-based reverse genetics system, and (2) to rescue a viable, recombinant virus, designated as rH120. The 12 genomic fragments of H120 were assembled using GGA, including the spike gene in fragment 10. The silent mutations introduced to remove internal BsmBI restriction sites did not alter the encoded amino acids or virus viability. The infectious virus was recovered successfully following transfection; in addition, serial passage in embryonated eggs confirmed that the reverse genetics system is functional and reliable for IBV manipulation.

In this study, the choice of reverse genetics system was based on its suitability for vaccine development and mutagenesis studies. Several platforms have been developed for IBV and other coronaviruses. The most commonly used approaches include Golden Gate Assembly [

19], targeted RNA recombination [

21], vaccinia virus vectors [

22], bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)–based systems [

25], and transformation-associated recombination (TAR) cloning [

23,

26]. GGA was selected as it offers rapid, modular, and scar-free assembly.

Sequencing and molecular verification by PCR were used to confirm the genetic integrity of the rescued virus. The accuracy of genome transcription and viral replication was demonstrated by (1) the presence of expected amplicons, which span different genomic regions, and (2) the detection of subgenomic mRNAs. The single-nucleotide substitution (C→G) at position 26,079 was introduced to remove the BsmBI restriction site. This substitution was validated by Sanger sequencing and did not interfere with virus recovery. Hence, the modification was genetically stable and fully compatible with efficient virus replication. Although other studies have employed a GGA-based reverse genetics system to reconstruct a full-length IBV genome, this is the first to apply this strategy to a vaccine strain of IBV (H120).

The rescued rH120 virus replicated effectively in embryonated chicken eggs, reaching titers comparable to those of the parental commercial H120 strain. The mean titer of approximately 10⁵ EID₅₀/mL reflects robust viral propagation, suggesting that the recombinant virus retained the replication competence of the original strain. This concurs with earlier studies on IBV, showing that carefully designed genome manipulation does not necessarily compromise viral growth characteristics [

23,

27,

28].

Both the rH120 and the original H120 showed nearly identical replication kinetics and progressive increases in viral RNA up to 36 hours post-infection followed by stabilization. The slightly higher RNA copy number observed for rH120 at 24 hours (

p < 0.05) may indicate a modest replication advantage during the early phase of infection, though this difference was transient [

27]. Beyond 24 hours, both viruses displayed equivalent growth patterns, confirming that the introduced modification did not affect the overall replication profile. The biological stability of the recombinant construct and its suitability for further functional and immunological evaluations have been reported in studies of related coronaviruses such as SARS-COV-2 and Porcine Epidemic Diarrhoea Virus [

20,

29].

The broiler chickens produced no deleterious clinical indications following experimental infection, indicating the

in vivo safety and tolerance of rH120 and H120 [

25,

30]. The viral shedding profiles in throat and cloacal swabs followed a typical IBV infection pattern, peaking approximately 6 days post-infection and declining by day 10 [

31]. The consistently higher RNA levels detected in throat swabs compared with cloacal samples reflect the respiratory tropism of IBV and align with previous reports indicating limited intestinal replication [

27]. The comparable shedding dynamics between the two groups further demonstrate that rH120 preserves the

in vivo replication characteristics the original H120 strain.

The virological results were consistent with the serological findings. Both rH120 and H120 induced strong antibody responses detectable by 7 days post-infection, with antibody levels continuing to rise by day 14 [

14,

30]. The slightly higher mean ELISA optical density values in the rH120 group indicate that the recombinant virus may stimulate a modestly stronger humoral immune response. This enhanced immunogenicity may reflect improved antigen expression or subtle differences in replication dynamics [

32]. Additional challenge studies will be necessary to determine whether this response translates into increased protective efficacy.

Overall, the reconstruction and rescue of rH120 represent a major advance in the development of a flexible reverse genetics platform for IBV. The recombinant virus demonstrated genetic stability, biological competence, and immunogenicity in vivo. These findings provide a foundation for future work including rational attenuation, chimeric vaccine development. and investigations into spike gene function and viral pathogenesis. Ongoing studies will assess the protective efficacy of rH120 against both homologous and heterologous IBV challenge strains and will explore the use of this platform to engineer next-generation IBV vaccines with improved cross-protective capacity.

5. Conclusions

This study reports the successful construction and rescue of a recombinant infectious bronchitis virus (rH120) using a Golden Gate Assembly reverse genetics system. The recombinant virus exhibited genetic stability, replicated efficiently in embryonated chicken eggs, and displayed biological characteristics comparable to the original H120 strain. In vivo, rH120 was safe, showed predominant replication in the respiratory tract, and elicited a strong antibody response in broiler chickens. Together, these findings validate the reliability of the GGA platform and underscore its potential for developing and evaluating genetically defined IBV vaccine candidates.

Supplementary Materials

There are no supplementary materials for this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N. and M.A.; methodology, A.N., S.J., M.A.; software, A.N., S.J., M.A.; validation, A.N. and S.J.; formal analysis, M.A. and A.N.; investigation, A.N., S.J., M.A.; resources, A.N. and S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, A.N., S.J., M.A.; visualization, A.N., S.J., M.A.; supervision, A.N. and M.A.; funding acquisition, A.N., S.J. M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Arab Pesticides and Veterinary Drugs Manufacturing Company.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Faris Tahayneh for his invaluable insights and exceptional technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Ali Nayef and Sara Jibreen are employed by the Arab Pesticides and Veterinary Drugs Manufacturing Company.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IBV |

Infectious Bronchitis Virus |

| rH120 |

recombinant H120 |

| GGA |

Golden Gate Assembly |

| CEFs |

chicken fibroblast cells |

| UTR |

Untranslated region |

| HDZ |

Hepatitis Delta Virus |

| cDNA |

Complementary DNA |

| NFW |

Nuclease-free water |

| dpi |

Days post-infection |

| EID₅₀. |

Embryo Infectious Dose 50 |

| RT-qPCR |

Reverse Transcriptase-Quantitative PCR |

References

- Rafique, S., et al., Avian infectious bronchitis virus (AIBV) review by continent. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2024. 14: p. 1325346.

- Lu, Y., et al., Molecular characteristic, evolution, and pathogenicity analysis of avian infectious bronchitis virus isolates associated with QX type in China. Poult Sci, 2024. 103(12): p. 104256.

- Shah, A.U., et al., Some novel field isolates belonging to lineage-1 of the genotype GI-avian infectious bronchitis virus (AIBV) show strong evidence of recombination with field/vaccinal strains. Infect Genet Evol, 2025. 129: p. 105723.

- Salles, G.B.C., et al., Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV) in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated Broilers in Brazil: Surveillance and Persistence of Vaccine Viruses. Microorganisms, 2025. 13(3).

- Vermeulen, C.J., et al., Genetic analysis of infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) in vaccinated poultry populations over a period of 10 years. Avian Pathol, 2023. 52(3): p. 157-167.

- Keep, S., et al., Limited Cross-Protection against Infectious Bronchitis Provided by Recombinant Infectious Bronchitis Viruses Expressing Heterologous Spike Glycoproteins. Vaccines (Basel), 2020. 8(2).

- Sjaak de Wit, J.J., J.K. Cook, and H.M. van der Heijden, Infectious bronchitis virus variants: a review of the history, current situation and control measures. Avian Pathol, 2011. 40(3): p. 223-35.

- Bijlenga, G., et al., Development and use of the H strain of avian infectious bronchitis virus from the Netherlands as a vaccine: a review. Avian Pathol, 2004. 33(6): p. 550-7.

- Fan, W.S., et al., Immune protection conferred by three commonly used commercial live attenuated vaccines against the prevalent local strains of avian infectious bronchitis virus in southern China. J Vet Med Sci, 2018. 80(9): p. 1438-1444.

- Cook, J.K., M. Jackwood, and R.C. Jones, The long view: 40 years of infectious bronchitis research. Avian Pathol, 2012. 41(3): p. 239-50.

- Yang, C.Y., et al., Effect of monovalent and bivalent live attenuated vaccines against QX-like IBV infection in young chickens. Poult Sci, 2023. 102(4): p. 102501.

- Shao, G., et al., Efficacy of commercial polyvalent avian infectious bronchitis vaccines against Chinese QX-like and TW-like strain via different vaccination strategies. Poult Sci, 2020. 99(10): p. 4786-4794.

- Abozeid, H.H. and M.M. Naguib, Infectious Bronchitis Virus in Egypt: Genetic Diversity and Vaccination Strategies. Vet Sci, 2020. 7(4).

- Sultan, H.A., et al., Protective Efficacy of Different Live Attenuated Infectious Bronchitis Virus Vaccination Regimes Against Challenge With IBV Variant-2 Circulating in the Middle East. Front Vet Sci, 2019. 6: p. 341.

- Almazan, F., et al., Engineering the largest RNA virus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2000. 97(10): p. 5516-21.

- Cai, H.L. and Y.W. Huang, Reverse genetics systems for SARS-CoV-2: Development and applications. Virol Sin, 2023. 38(6): p. 837-850.

- Marillonnet, S. and R. Grutzner, Synthetic DNA Assembly Using Golden Gate Cloning and the Hierarchical Modular Cloning Pipeline. Curr Protoc Mol Biol, 2020. 130(1): p. e115.

- Sikkema, A.P., et al., High-Complexity One-Pot Golden Gate Assembly. Curr Protoc, 2023. 3(9): p. e882.

- Bilotti, K., et al., One-pot Golden Gate Assembly of an avian infectious bronchitis virus reverse genetics system. PLoS One, 2024. 19(7): p. e0307655.

- Taha, T.Y., et al., Rapid assembly of SARS-CoV-2 genomes reveals attenuation of the Omicron BA.1 variant through NSP6. Nat Commun, 2023. 14(1): p. 2308.

- van Beurden, S.J., et al., A reverse genetics system for avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus based on targeted RNA recombination. Virol J, 2017. 14(1): p. 109.

- Zhao, Y., et al., Successful establishment of a reverse genetic system for QX-type infectious bronchitis virus and technical improvement of the rescue procedure. Virus Res, 2019. 272: p. 197726.

- Li, Y., et al., Rapid reconstruction of infectious bronchitis virus expressing fluorescent protein from its nsp2 gene based on transformation-associated recombination platform. J Virol, 2025. 99(7): p. e0053525.

- Keep, S., et al., Multiple novel non-canonically transcribed sub-genomic mRNAs produced by avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. J Gen Virol, 2020. 101(10): p. 1103-1118.

- Zhou, Y., et al., The establishment and characteristics of cell-adapted IBV strain H120. Arch Virol, 2016. 161(11): p. 3179-87.

- Thi Nhu Thao, T., et al., Rapid reconstruction of SARS-CoV-2 using a synthetic genomics platform. Nature, 2020. 582(7813): p. 561-565.

- Lu, Y., et al., Rapid development of attenuated IBV vaccine candidates through a versatile backbone applicable to variants. NPJ Vaccines, 2025. 10(1): p. 60.

- Lv, C., et al., Construction of an infectious bronchitis virus vaccine strain carrying chimeric S1 gene of a virulent isolate and its pathogenicity analysis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2020. 104(19): p. 8427-8437.

- Kristen-Burmann, C., et al., Reverse Genetic Assessment of the Roles Played by the Spike Protein and ORF3 in Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Pathogenicity. J Virol, 2023. 97(7): p. e0196422.

- Zhou, Y.S., et al., Establishment of reverse genetics system for infectious bronchitis virus attenuated vaccine strain H120. Vet Microbiol, 2013. 162(1): p. 53-61.

- Naqi, S., et al., Establishment of persistent avian infectious bronchitis virus infection in antibody-free and antibody-positive chickens. Avian Dis, 2003. 47(3): p. 594-601.

- Ellis, S., et al., Recombinant Infectious Bronchitis Viruses Expressing Chimeric Spike Glycoproteins Induce Partial Protective Immunity against Homologous Challenge despite Limited Replication In Vivo. J Virol, 2018. 92(23).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).