1. Introduction

Burn injuries pose a significant global health burden, resulting in substantial morbidity and mortality [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. While acute management focuses on preventing infection and fluid resuscitation, the subsequent healing process often presents challenges. Extensive burn wounds can lead to significant scarring, contractures, and impaired functional recovery, necessitating prolonged rehabilitation and impacting the patient’s quality of life [

6,

7,

8].

Traditional wound healing approaches often rely on autografts, which involve harvesting skin from uninjured areas of the patient. However, autografts can be limited by donor site morbidity, inadequate graft availability and potential complications [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Furthermore, the use of allografts, derived from deceased donors, carries the risk of disease transmission and immune rejection [

13,

14].

In recent years, regenerative medicine has emerged as a promising avenue for burn wound treatment, aiming to accelerate and enhance the healing process. Cell-based therapies have garnered significant attention due to their inherent regenerative potential [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Different cell types such as fibroblast, keratinocytes, epidermal stem cells, multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells, bone marrow stem cells, adipose-derived stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells were used to promoting wound healing [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] and these cell sources were reviewed by Rangatchew in 2021 [

7].

However, direct application of cells at the wound site often results in limited cell retention and engraftment due to factors including cell survival, rapid cell migration, lymphatic drainage, and immune rejection [

7,

10,

11]. Therefore, an ideal scaffold that has the capacity to act as a template for the cell therapy is essential [

29,

30,

31]. Several key factors must be considered when using scaffold as the delivery system which include cytocompatibility, biocompatibility, biodegradability, mechanical strength, ideal internal and external architecture to support cell migration and nutrient diffusion.

Biomaterials are essential components in various burn dressings and tissue-engineered constructs. Their primary purpose is to replicate the skin’s extracellular matrix (ECM), which is comprised of collagen, elastin, proteoglycans, nidogen, laminin, and perlecan. The main key components confer critical properties: collagen provides structural strength, elastin enables elasticity and flexibility, and proteoglycans contribute hydration and viscosity [

31].

To date, the majority of commercially available products for skin burn and wound management are based on collagen, decellularized tissues or hydrogel [

28,

32,

33]. Among these biomaterials, hydrogels have proven particularly favourable for burn healing by providing an optimal microenvironment and optimal hydration and are extensively utilized in tissue engineering approaches [

34,

35]. These three-dimensional networks composed of hydrophilic polymers exhibit excellent biocompatibility, tuneable mechanical properties, and the ability to mimic the ECM of native tissues. By incorporating cells within a hydrogel scaffold, researchers can create a more physiologically relevant environment that supports cell survival, proliferation, and function along with providing an ideal methodology for large surface treatments [

36]. Among the various types of hydrogels explored for biomedical applications, hyaluronic acid (HA)-based gels have gained particular attention due to HA intrinsic biocompatibility, biodegradability, and role in tissue regeneration.

The burn wound healing product based on hyaluronic acid should be a commercially available medical device that meets the CE or FDA standards and should possess all the necessary criteria such as quality, efficacy and safety. However, few hyaluronic acid based scaffold products were used for wound healing processes [

37] which limit the clinical development of such approaches.

In this study, we tested Redensity 1

(RD1), a CE-MDR approved, class III, injectable medical device, as a biocompatible vehicle for cell delivery. RD1 is formulated with 1.5%

w/

w of high-quality, high molecular weight, non-animal origin hyaluronic acid, 0.3% w/w lidocaine for patient comfort and pain alleviation, and a cocktail of nutrients (including amino acids, minerals, antioxidants and vitamins). RD1 is indicated for the enhancement of skin quality, hydration and correction of withered skin marked by signs of ageing on the face, neck and neckline. It is also indicated for the prevention of superficial fine wrinkles including forehead lines, crow’s feet, perioral rhytids, and neck lines. As a light, fluid, and smooth product, RD1 is typically injected superficially into the dermis or subdermal plan for optimal effectiveness and would represent an ideal candidate for cytotherapies in burn wound healing [

38,

39].

2. Results

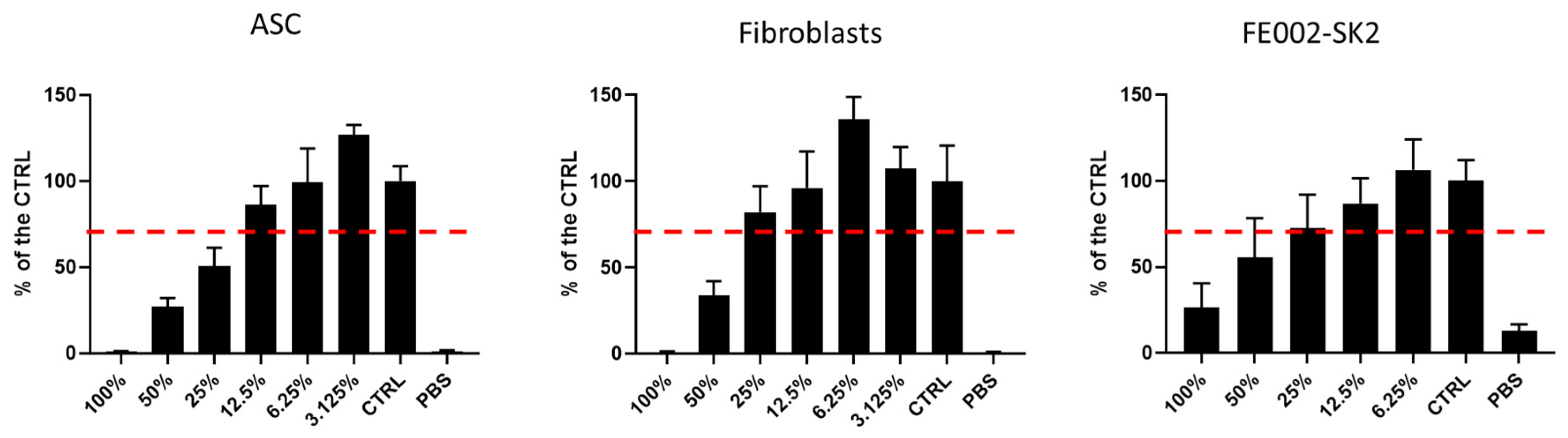

2.1. Cytotoxicity Assay for RD1 Gel

We first evaluated the RD1 gel cytocompatiblity with multiple therapeutic cell types including polydactyly ASC and adult fibroblasts as well as FE002-SK2 progenitor skin fibroblasts which are clinical cells used to treat 2nd and 2nd-deep degree burns [

29,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. As seen in

Figure 1, a dose response with an IC50 of 25% was evidenced for ASC cells, 45.56% for fibroblasts and 60.33% for FE002-SK2. Visual observations of cell morphology matched the cellTiter assay results (suplementary

Figure S1).

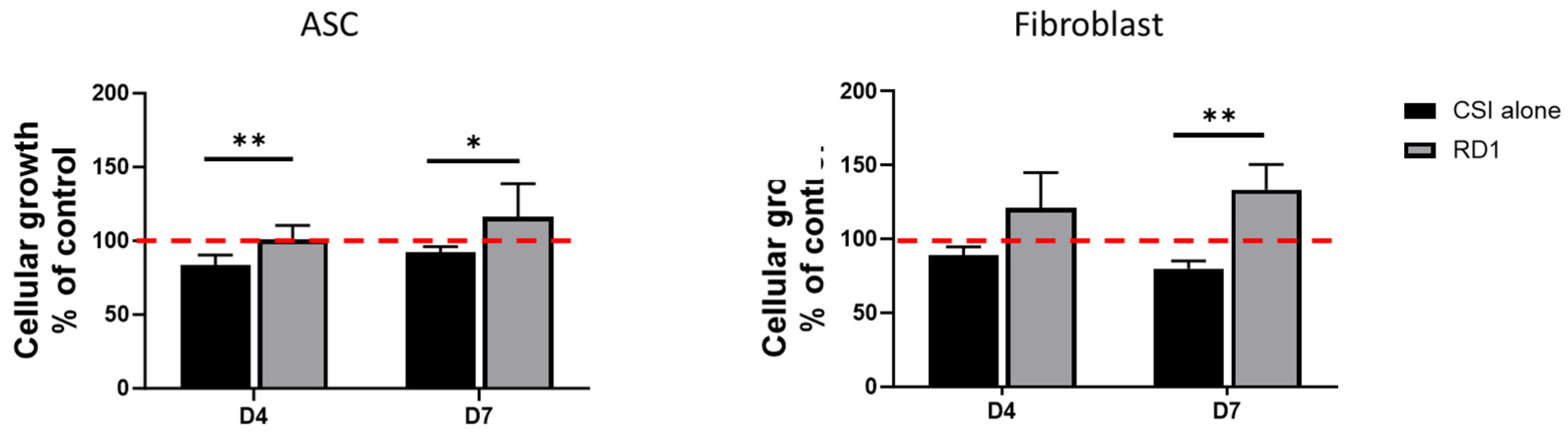

2.2. Clinical Doses of RD1 (100µL) Induce Polydactyly Fibroblasts and ASC Proliferation

To capture the effect of clinically-relevant doses of RD1 on skin cell proliferation (ASC and polydactyly fibroblasts), an in vitro model using cell strainer inserts (CSI) was developed to mimic RD1 gel diffusion into the skin (

supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 2 shows that RD1 promoted cellular growth of both polydactyly fibroblasts and ASC in a significant manner as soon as 4 days of incubation and confirmed at 7 days. CSI alone shows a negative impact on cellular growth. Therefore, the presence of RD1 significantly improved cellular growth of both tested primary cells. Images of the cells in culture can be found in the

supplementary Figure S3.

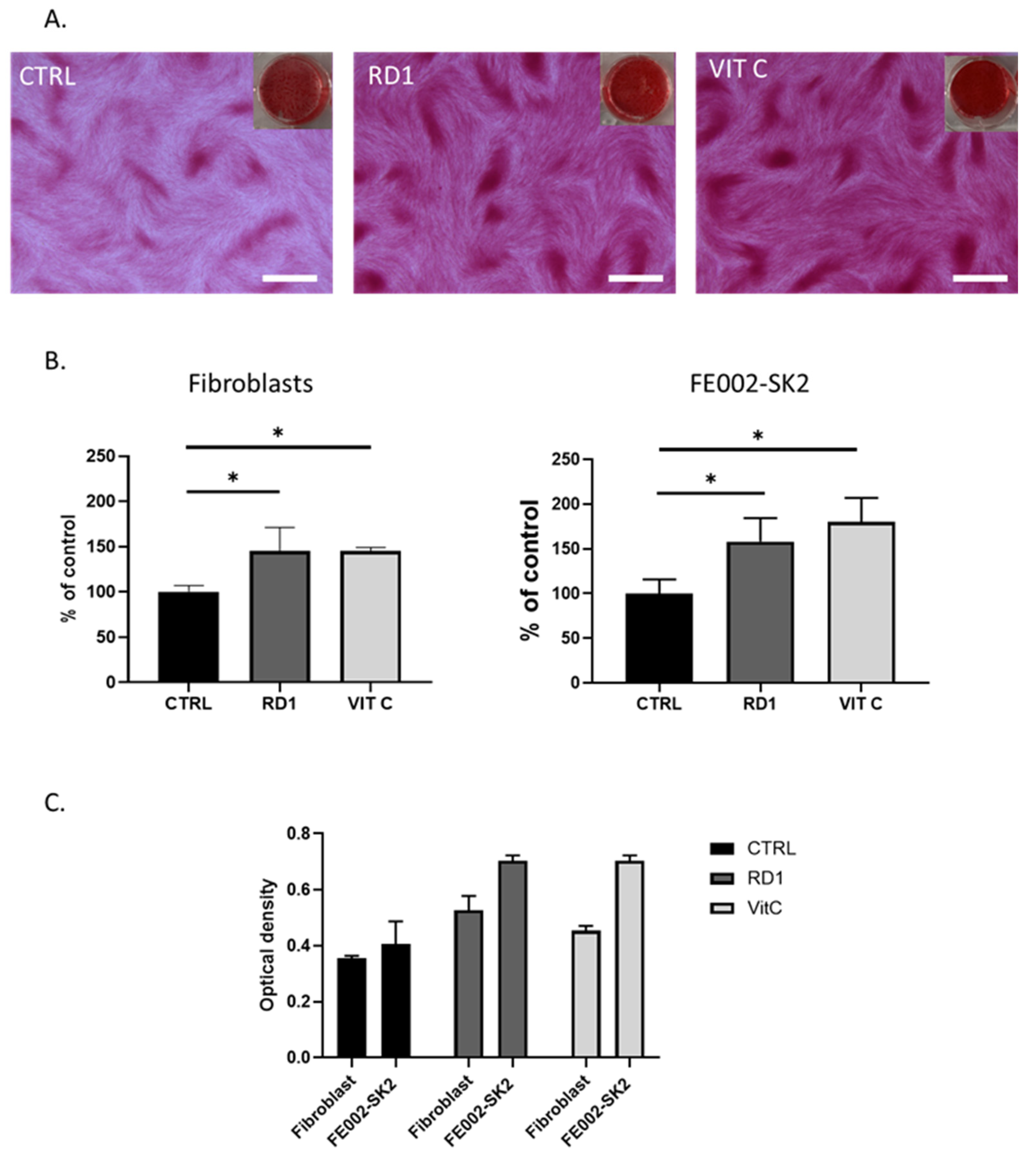

2.3. Clinical Doses of RD1 (100µL) Induce Collagen Production by Polydactyly Fibroblasts and FE002-SK2 Primary Progenitor Fibroblasts

Using the same in vitro model with CSI, we assessed the ability of clinical doses of RD1 gel (100 µL) to promote collagen deposition from polydactily fibroblasts and FE002-SK2 progenitor fibroblast cells.

Figure 3 shows that with a dose equivalent to 1.1% of gel (i.e., 100 µL of gel in 9 mL of medium), RD1 gel is able to enhance the collagen production in both polydactyly fibroblasts and FE002-SK2 cells, comparable to the positive control, vitamin C.

Figure 1C further demonstrated that FE002-SK2 innately produce significantly more collagen than polydactyly primary cells and thus have already a maximum collagen content confirming previous results [

45].

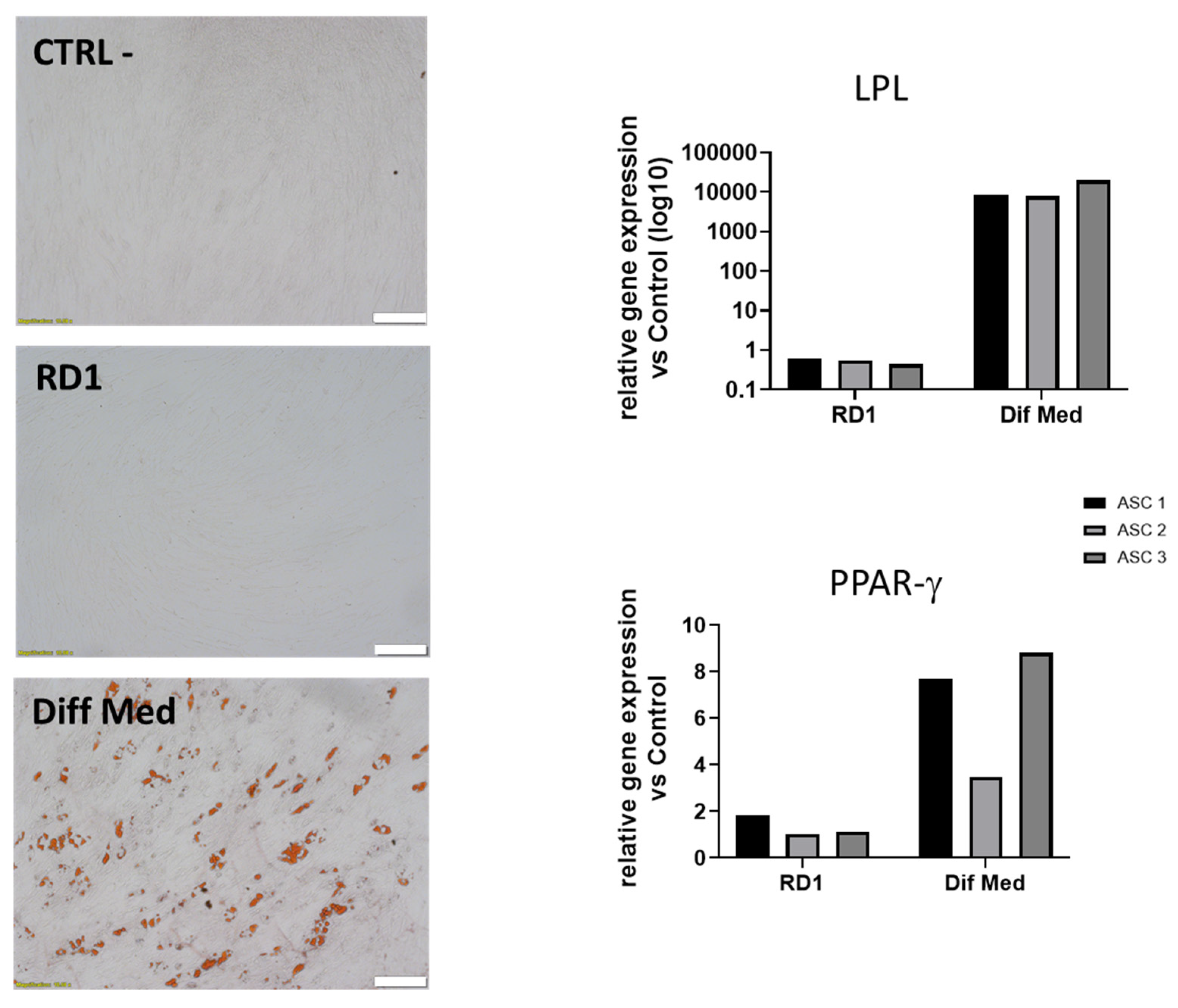

2.4. Clinical Doses of RD1 (100µL) does not Induce ASC Differentiation in Adipocytes

We further assessed the ability of clinical doses of RD1 gel (100 µL) to induce ASC differentiation into adipocytes in normal culture medium with no addition of differentiation factors. The experiment was performed on 3 different polydactyly cell sources,

Figure 4 shows that RD1 does not influence ASC differentiation in adipocytes in normal conditions as shown with Oil Red O staining as well as with qPCR were we observe no increased expression of LPL and PPAR γ genes.

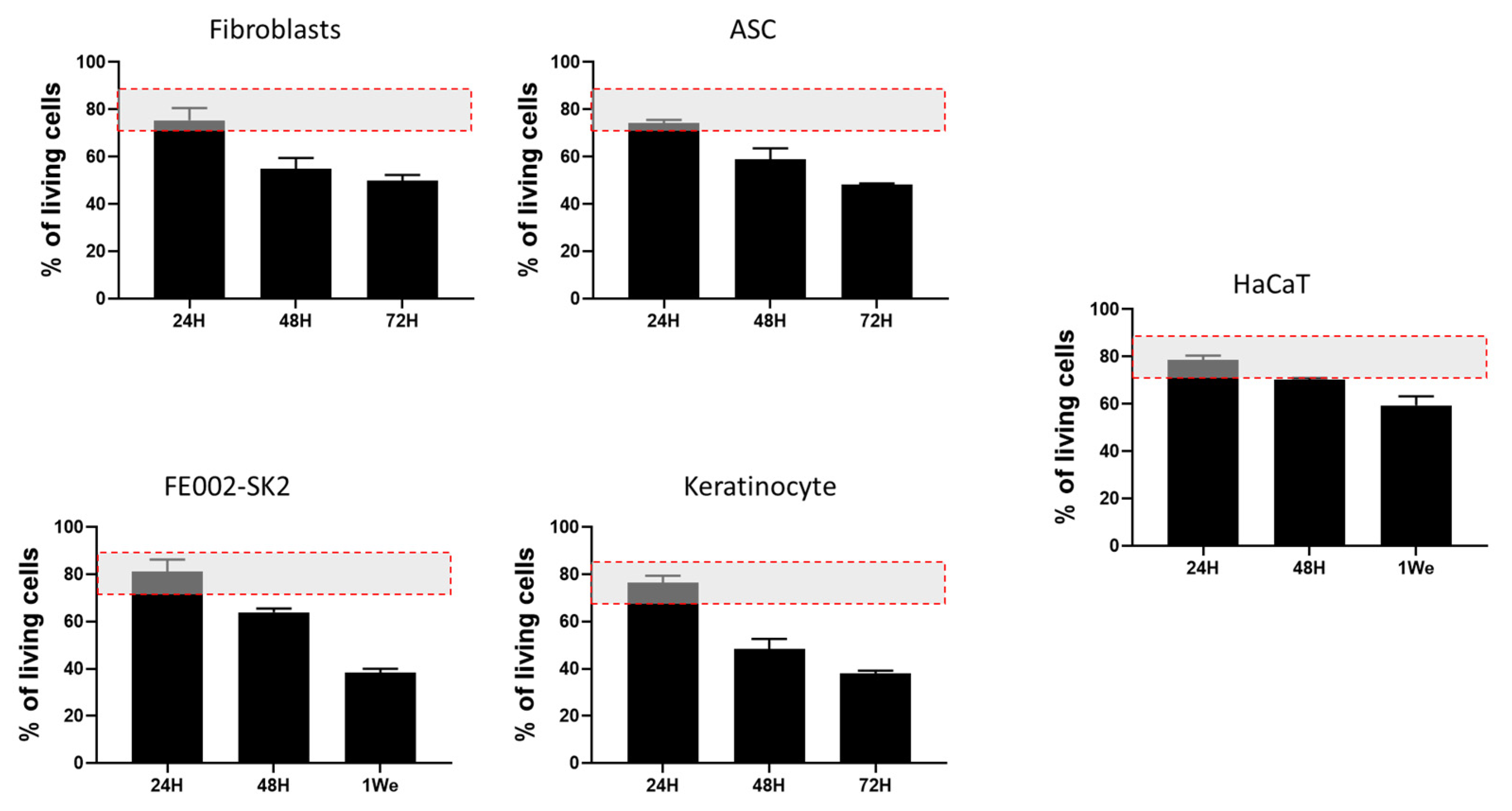

2.5. RD1 Maintains Cell Viability in Starving Conditions

To assess the cell delivery potential of RD1 gel for burn treatment, different cell sources relevant for burn care (polydactyly fibroblasts and ASC; FE002-SK2, keratinocyte and HaCaT) were mixed within the gel in the absence of culture medium (starving conditions) for 24, 48, 72 hrs or 1 week at 37 °C, in a cell culture incubator. The absence of medium is explained by the fact that, when used in the clinic, cells need to be delivered without culture medium for safety and regulatory compliance: culture media often contain components that are not approved for direct human use, such as animal-derived serum or growth factors. Results of the Live/Dead evaluation shown in

Figure 5 present a survival rate of almost 80% after 24h for all the cellular sources tested. After 48 and 72 hrs we observe a decrease in cellular viability around 20% by day for polydactyly fibroblasts and ASC as well as for primary adult keratinocytes. FE002-SK2 cells show a better survival rate after 48 hours than the other primary cells (64% vs 58% (ASC), 54% (fibroblasts) and 48%(Keratinocytes), respectively, and at leat 40% of cells were still viable after 1 week in the gel. HaCaT immortalized keratinocytes presented the higher cellular survival rate at 48 hrs and 1 week than the other cell types but this is an immortalized cell line which is used for wound healing routinely for in vitro studies.

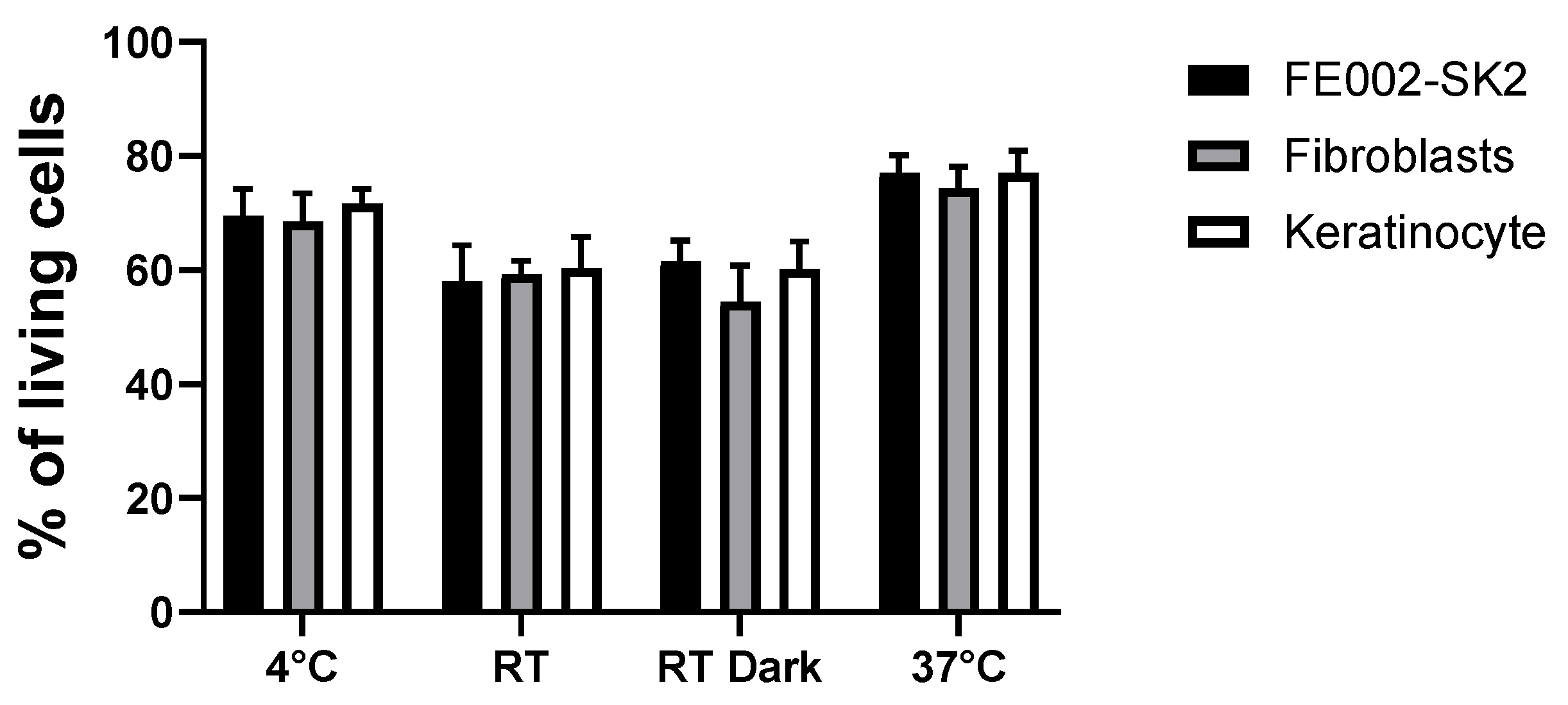

As all cells show a survival of almost 80% at 37 °C, we aimed to test different storage conditions (4 °C, RT, RT in the dark and 37 °C in the cell culture incubator) for 3 different cell sources, corresponding to the ones used in the clinic to treat burn patients.

Figure 6 highlights that the best storage conditions are at 4 °C or 37 °C for all the tested cell sources. This indicates that in the case of a delay in cell delivery in the operating room, cellular preparation could be stored 24 hrs at 4 °C until used.

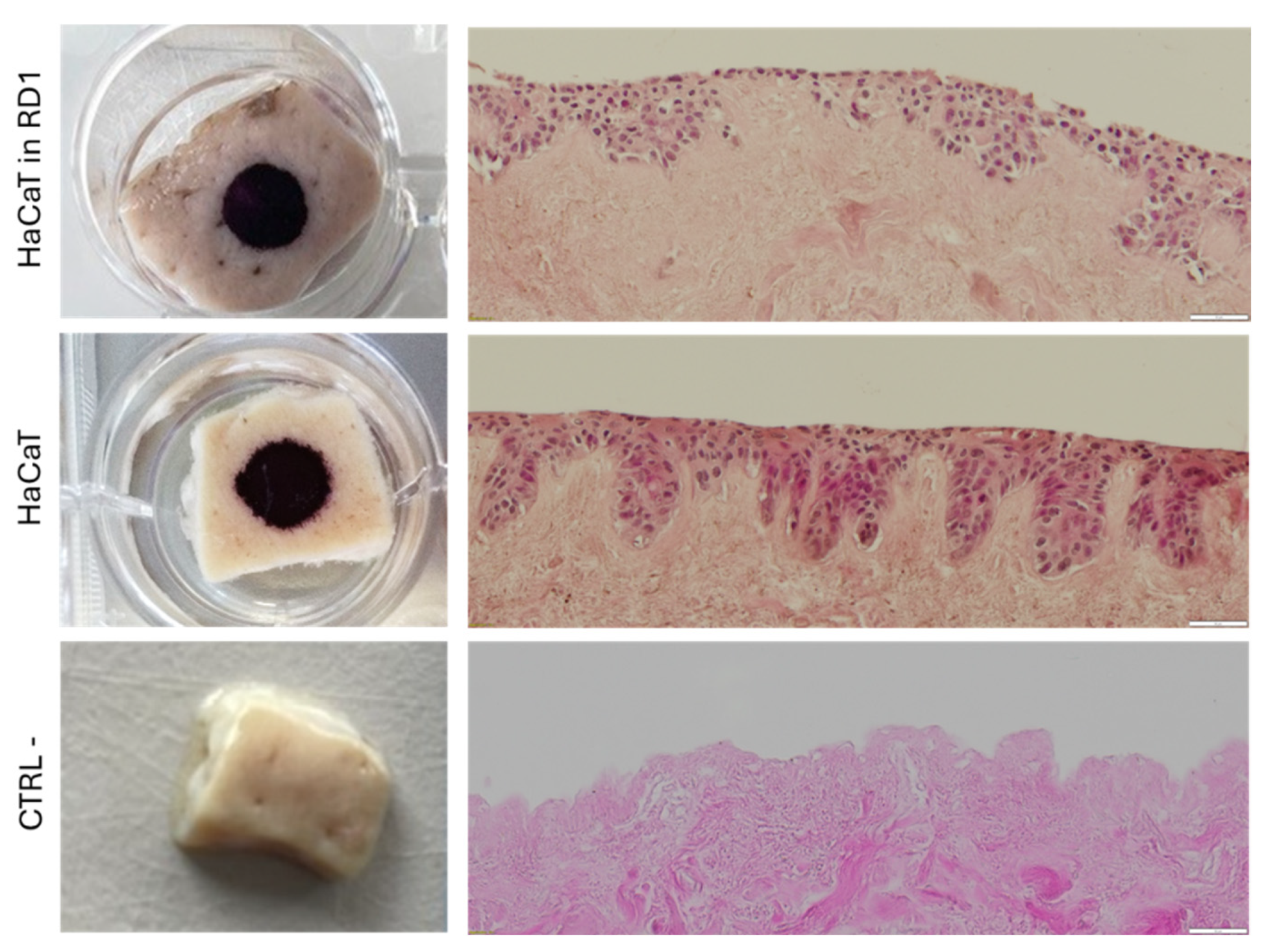

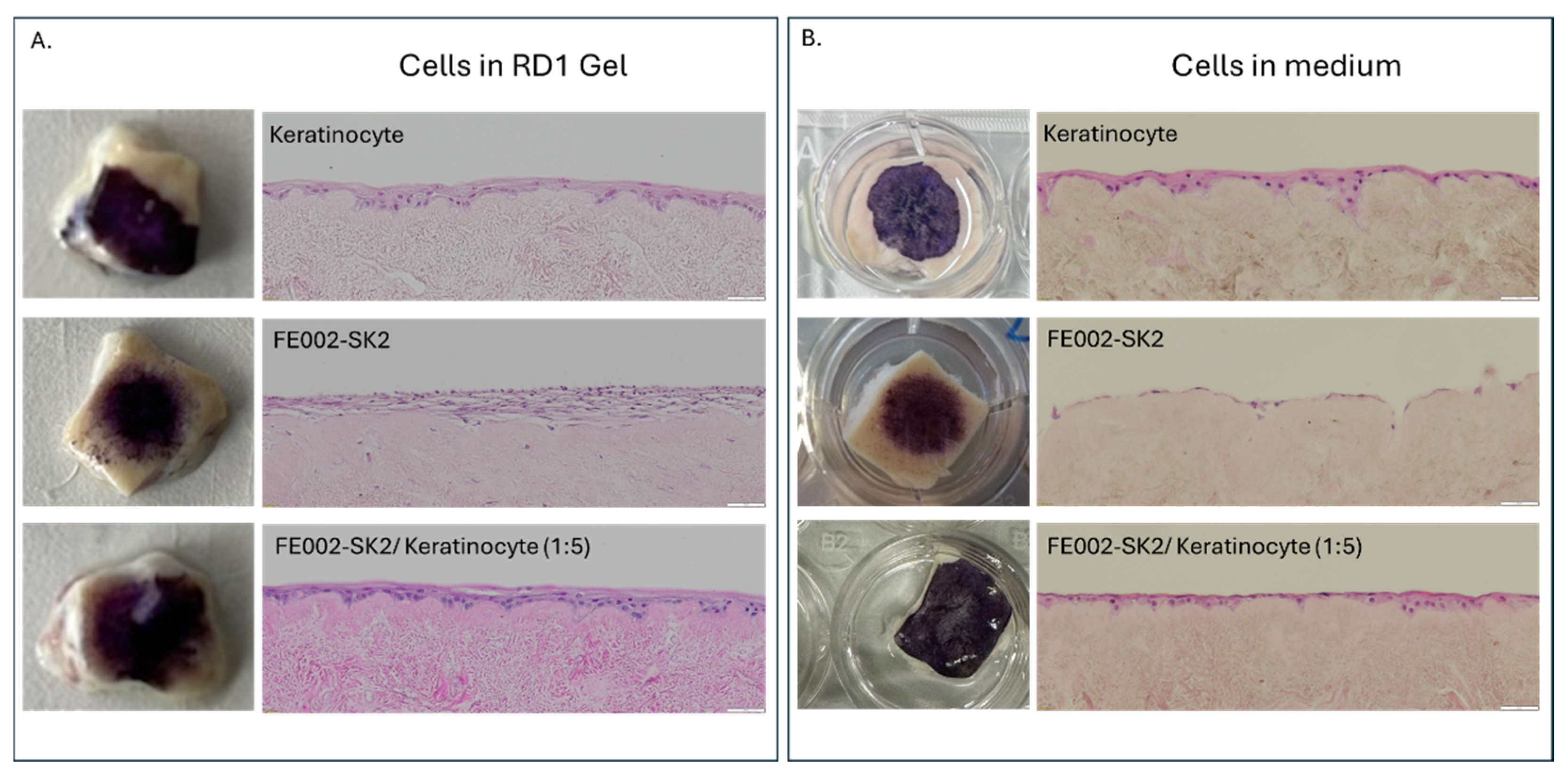

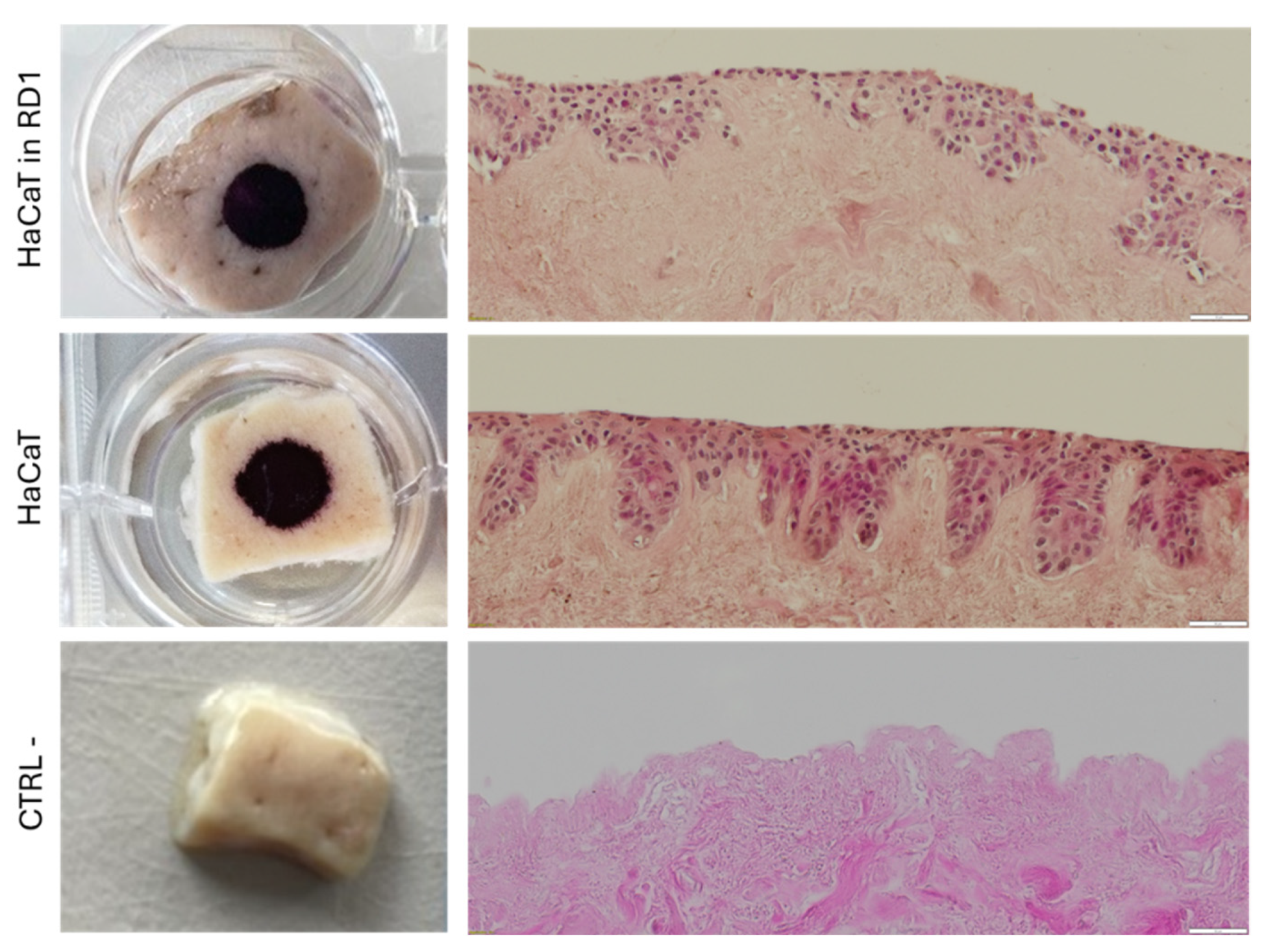

2.6. Evaluation of Cell Delivery on a De-Epidermized Dermis (DED) for Cutaneous Cell Therapies

We first evaluated the possibility to deliver HaCaT keratinocyte cells on a air-liquid interface DED model [

46]. MTT staining of the DED presented no observable difference between viable HaCaT cells mixed with the RD1 gel patern distributions and the HaCaT cells in medium that were used as the control (

Figure 7). This was confirmed by the H&E staining of DED cross-sections which showed the same cellular distribution.

Using the DED model, we then tested the delivery of cells that could be used in the clinic for the treatment of severe burns (keratinocytes, fibroblasts and FE002-SK2 cells). We observed that cells mixed with RD1 gel showed the same skin equivalent appearance than cells directly seeded on the DED, confirming the possibility to deliver cells with RD1 (

Figure 8). Moreover, cells delivered in RD1 presented more cellular layers than those directly seeded in culture medium.

3. Discussion

This study investigated the feasibility of using a commercially available hyaluronic acid (HA) gel as a delivery vehicle for cells in the context of burn treatment. We employed RD1 gel, a CE-MDR approved, class III injectable medical device formulated with 1.5% w/w of high-quality, high molecular weight, non-animal origin hyaluronic acid and 0.3% w/w lidocaine. This gel is routinely used for intradermal injections.

First, we examined the effects of RD1 at clinically relevant doses (100 μL, equivalent to a bolus) on primary cells in culture. Our results demonstrate that this HA hydrogel significantly promotes the proliferation of juvenile fibroblasts and adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) over time. Moreover, the same dose enhances collagen synthesis in juvenile fibroblasts and FE002-SK2 progenitor cells obtained from a clinically validated cell bank used for burn patient treatment [

41]. The stimulatory effect of HA on collagen production has been previously documented in vivo following dermal filler injections [

47], in animal models [

48], and in skin organ culture systems [

49], but not in isolated cell cultures. Importantly, RD1 did not induce collagen synthesis in juvenile ASC (data not shown) nor their differentiation into adipocytes. This represents a safety advantage for burn treatment, particularly in third-degree burns where the gel may contact adipose tissue, as adipogenic differentiation would be undesirable. Previous studies have reported that a cross-linked HA gel with a higher HA concentration (25 mg/mL), combined with adipogenic differentiation medium, promotes ASC differentiation into adipocytes [

50]. However, given the substantial differences in experimental conditions, direct comparison is not appropriate.

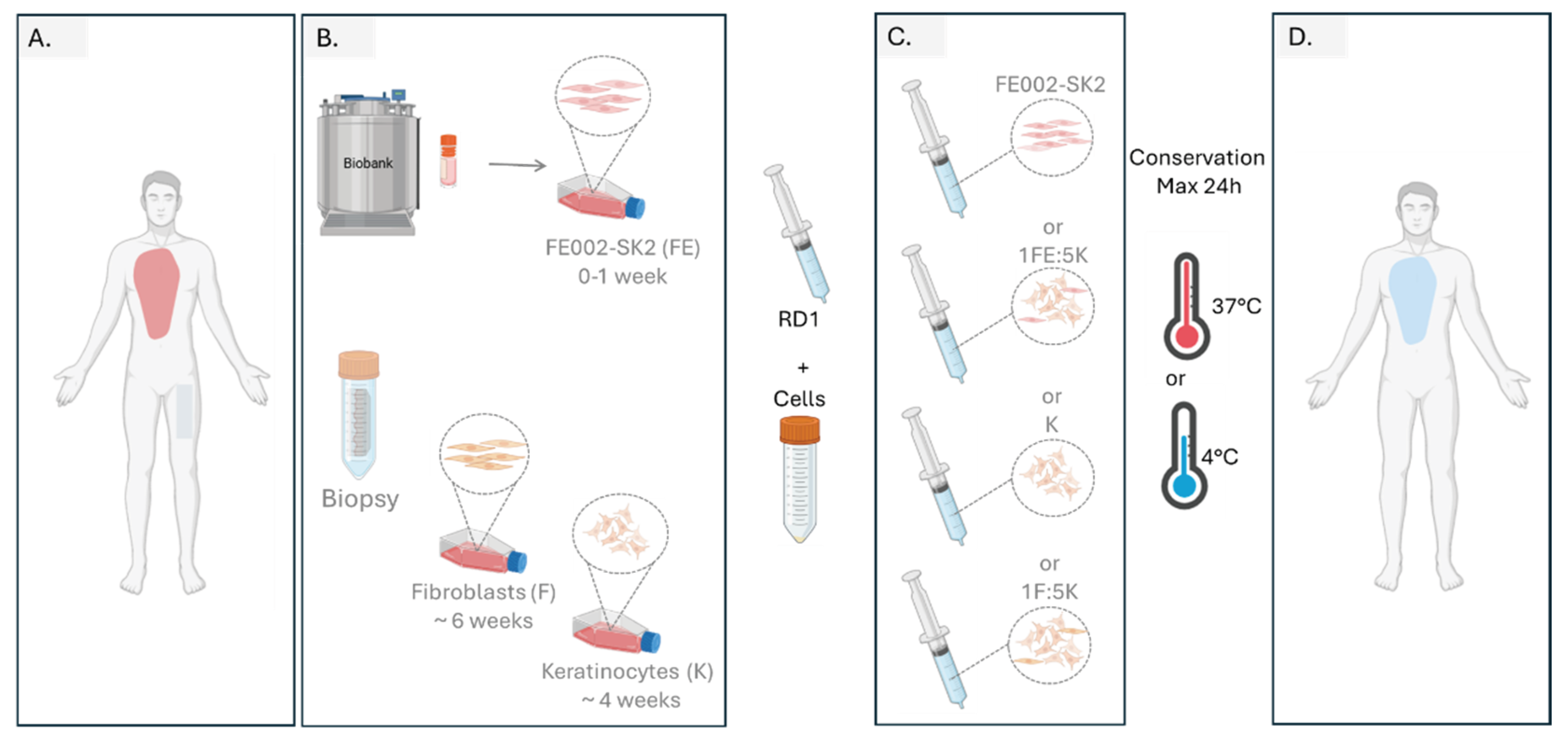

Next, we assessed the potential of RD1 as a cell delivery system. Previously, we demonstrated the feasibility of delivering primary progenitor tenocytes using HA gels employed for clinical viscosupplementation [

51]. Similarly, cells mixed with RD1 exhibited high viability (~80%) after 24 hrs of storage at either 37 °C or 4 °C. This suggests that, in a clinical setting, the cell-gel preparation could be stored in an operating room refrigerator until patient readiness. We used a decellularized skin model for testing cellular delivery of different primary cellular combinations mixed in RD1 gel and compare them to cells directly seeded on the top of the DED. We have demonstrated that RD1 could be an alternative to the collagen matrix that is currently used in the clinic for the delivery of FE002-SK2 progenitor fibroblasts [

41,

52], for early burn coverage. We recently demonstrated that a combination of one fibroblast (progenitor or adult) and five adult keratinocytes delivered in culture medium on a DED model resulted in multilayered keratinocyte structures [

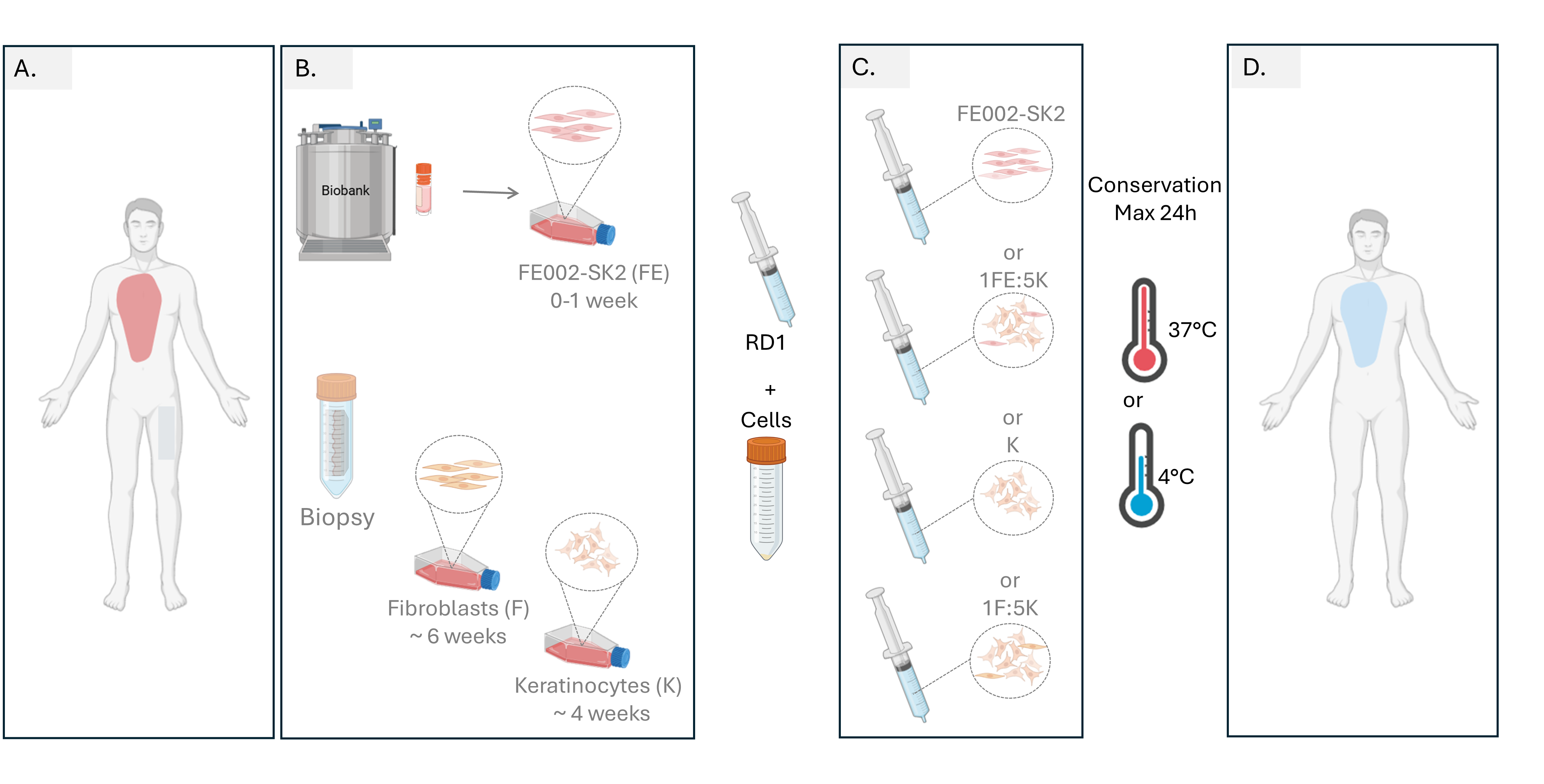

46]. In this study, we show that the same 1F:5K ratio delivered in RD1 gel achieves comparable or superior outcomes, supporting the concept that HA-based delivery could be a viable option for burn patient treatment. A conceptual clinical pathway highlighting the potential use of RD1 as a delivery vehicle for therapeutic skin cells in burn management is presented in

Figure 9, illustrating its translational relevance for regenerative medicine applications.

There are several products available which are hyaluronan-based for the topical management of burn wounds. Cell-free products include Hyalomatrix

®, Hyalosafe

®, HYAFF

®-11, and Ialugen

® while cell-laden products such as Hyalograft 3D™, and Laserskin™ are also available [

36,

53,

54,

55,

56] and several clinical studies have shown their benefits for their use on burn wounds [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. Hyaluronan hydrogels are easy to apply to the wound and provide a smoothing effect which may contribute to the significant alleviation of pain noticed by many patients [

62]. Still, hyaluronan hydrogels may have moderate outcome depending on the extent and gravity of burn injury. Topical delivery of HA has shown variable tissue penetration capacities, wherein a MW of 100 kDa enabled optimal passage through the disrupted skin barrier [

63,

64]. Hence, if large surfaces of “intact” skin remain throughout the burn injury, there may be variable clinical results. This was shown in a recent study by De Francesco in a burn patient with a formulation of 0.2% HA needing more than 4 weeks for partial wound closure [

37].

Hyaluronan viscous solutions like RD1 can also be used to incorporate therapeutic cells, forming a 3D environment with enhanced biological activities and wound healing potential [

65,

66,

67]. The 3D cell incorporation could also potentially reduce the inherent immunogenicity of the scaffold formulations [

68]. Furthermore, the use of RD1 may offer several practical advantages. The ease of manufacturing and sterile delivery of these hydrogels could streamline clinical application. Additionally, the potential for customization, such as incorporating specific growth factors or antimicrobial agents, could allow for personalized treatment approaches tailored to individual patient needs. Similarly, autologous patient cells or off-the-shelf cells within highly controlled cell banks could be proposed.

4. Conclusions

Taken together, these findings and our past data support the use of non-crosslinked hyaluronan RD1 as a versatile and effective vehicle for cell delivery. RD1 not only protects the cells but provides the ideal viscosity to remain at the injured burn site which is not the case with cells delivered in NaCl. Noteworthy, the HA solution also showed stimulation of cell growth and collagen synthesis. Its ease of use, compatibility with various cell types, and ability to support therapeutic outcomes make it a strong candidate for applications in wound healing, burn management, and regenerative medicine. Future research should explore its performance in long-term in vivo models, its interaction with bioactive molecules, and its scalability for clinical translation. In addition, the experiments employing larger gel volumes (5–10 mL) are needed to enable coverage of extensive burn areas, so as to get to real-life conditions. Finally, clarification of the regulatory framework for this “combination product” is required to ensure appropriate pathways for patient use.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Ethical Compliance of the Study

Obtention and use of patient primary cellular materials (i.e., primary polydactyly fibroblasts and ASCs, adult keratinocyte) followed the regulations of the Biobank of the Department of Musculoskeletal Medicine at the CHUV (Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland) and were registered in the CHUV-DAL Department Biobank under an ethics protocol approval and following the applicable biobanking directive (BB_029_DAL). The clinical grade primary progenitor cell source used in the present study (i.e., FE002-SK2 primary progenitor fibroblasts) was established from the FE002 organ donation, as approved by the Vaud Cantonal Ethics Committee (University Hospital of Lausanne, Ethics Committee Protocol N 62/07).

5.2. Cell Sources

Polydactyly primary dermal fibroblasts and adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) from 3 polydactyly patients (aged from 1, 2 and 7 days) were thawed from previously established cell banks [

69]. Dermal fibroblasts were cultured in Medium 1 composed of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 1% L-glutamine (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). ASCs were cultured in Medium 2 composed of DMEM supplemented with 5% human platelet lysate (HPL, BioLife Solutions). HaCaT immortalized keratinocytes (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in Med_1, served as a control cell line. Primary adult keratinocytes were obtained from tissue designated as medical waste following routine abdominoplasties as described previously [

8] and cultured in Medium 3, CnT-PR medium (CellnTec, Bern, Switzerland). FE002-SK2 primary progenitor fibroblast vials from our clinical cell bank were thawed and serially expanded in vitro in Med_1. For all the cells, medium was exchanged twice per week, and all cultures were maintained in humidified incubators at 37 ◦C with 5% CO

2. Primary cells were used for experiments between passages 3 to 6 unless specified and FE002-SK2 primary progenitor fibroblast were used at passages 7 and 9.

5.3. RD1 Cytotoxicity Assay on FE002-SK2 and Polydactily Fibroblast and ASC cells

FE002-SK2 primary progenitor fibroblasts, Polydactyly fibroblasts and ASCs were seeded at a cellular density of 1x104 cells/well in 96-well plates. After 24 hours, cells were treated with 100 µl RD1 gel diluted in their respective culture medium at concentrations ranging from 100% to 3.125% RD1 gel. Cells cultured in their respective medium served as positive control, and cells maintained in PBS as negative control. Cell viability was assessed after 72 hours using the CellTiter® assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) as recommended by the manufacturer.

5.4. Cellular Growth Evaluation of Various Cell Types Exposed to Hydrogels

We developed an in vitro model to mimic gel diffusion in the skin with the use of 100uL cell strainer inserts (CSI) (Corning

®, NY, USA). Polydactyly fibroblasts and ASCs cells were seeded at 3x10

3 cells/cm

2 in 6-well plates in their respective culture medium. After 24 hours, 3 culture conditions were set up: (1) control, cells in their respective culture medium with no CSI (CTRL), (2) CSI alone, cells in their respective culture medium with a CSI and no RD1 gel (3) CSI with 100µl RD1, cells in their respective culture medium with a CSI containing 100uL of RD1 gel (see supplementary

Figure 1 for the experimental set up). In brief, medium was removed from the cultured cells and replaced with 3 mL of fresh medium, cell strainers were placed in the 6 well plates with and without 100µl RD1 gel. Then, medium was added to submerge the gel (final volume of 9 mL). There were no further medium changes during the experiment duration. Cells were enumerated at after 4 and 7 days. Results were expressed as percentage of control. Pictures were taken with an inverted Olympus IX83 microscope with a DP75 camera.

5.5. Collagen Production of Various Cell Types

To evaluate collagen production enhancement ability of RD1, polydactyly fibroblasts and FE002-SK2 skin progenitor fibroblasts were seeded at 3x103 cells/cm2 in 6-well plates. Upon reaching confluence, 3 groups and controls were set up as follows: (1) control, cells in culture medium 1 (CTRL), (2) CSI with 100 µl RD1, cells in culture medium 1 with a CSI containing 100uL of RD1 gel, (3) VitC, cells in culture medium 1 supplemented with 10−4 M vitamin C. The medium was replaced every 2 days for 7 days for the control and the vitamin C condition but not for the CSI with the RD1 gel. After 7 days, the treated cell monolayers were washed with 1× PBS, fixed in methanol at −20 °C for 10 mins, rinsed three times with 1× PBS, and Sirius Red staining and subsequent quantification was performed. The collagen was stained with 2mL of 0.1% Sirius Red (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) in 1.3% picric acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 1 hr at room temperature with agitation; after gently rinsing each well four times with 0.5% acetic acid. Macroscopic imaging was performed on an iPhone 12 Pro Max (Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA) and microscopic images on an Olympus IX83 microscope with a DP75 camera. For quantification, 2mL of 0.1 M NaOH was added to the wells for 30 mins at room temperature with agitation. The samples were then transferred to a new 96-well plate for absorbance measurement at 560 nm on a Varioskan LUX multimode plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Absorbance data were analyzed using the Skanit-RE software v5.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

5.6. Adipogenesis Induction Assays with Polydactyly Adipocyte Stem Cells (ASC)

To assess if RD1 gel was able to induce the differentiation of polydactyly ASC cells in natural conditions, cells were seeded at 3x103 cells/cm2 in 6-well plates. Upon reaching confluence, 3 groups and controls were set up as follows: (1) positive control for ASC differentiation with adipogenic induction medium (DMEM, ITS 1x (Corning®, NY, USA), 100 μM indomethacin (Acros Organics™, Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA), 1 μM dexamethasone (Acros Organics™, Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA), 100 μM IBMX (Alfa Aesar™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), (2) negative control for ASC differentiation with culture medium 2, and (3) CSI with 100µl RD1 in culture medium 2. Medium was changed once a week for RD1 group and twice a week for the other 2 groups. After 14 days of adipogenic induction, lipid droplet formation was assessed by Oil Red O staining (Sigma-Aldrich®, USA). Experiments were performed on 3 different polydactyly ASC sources.

5.7. Analysis of Adipogenic Gene Induction (PPARγ, LPL): RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as described by the manufacturer. RNA purity and concentration were quantified via spectrophotometry with a NanoDrop instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Reverse transcription into cDNA was performed using 500 ng of RNA in a final volume of 10 µL using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, San Jose, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The reverse transcription cycle conditions were as follows: 37 ◦C for 15 min and 85 ◦C for 5 s. A real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was then performed in 96-well microplates on a QuantStudio™ PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The reaction was performed using 5 ng of cDNA for a final volume of 10 µL using the KAPA SYBR Fast (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescence was acquired using the following cycling conditions: 95 °C for 3 minutes (enzyme activation) and 40 amplification cycles (95 °C for 3 seconds and annealing extension at 60 °C for 30 seconds). Each sample was run in triplicate, and the relative expression level for each gene was normalized to GAPDH forward 5′-CGC TCT CTG CTC CTC CTG TT-3′, reverse 5′-CCA TGG TGT CTG AGC GAT GT-3′. Gene expression levels for PPARγ forward 5′-TAC TGT CGG TTT CAG AAA TGC C-3′, reverse 5′-GTC AGC GGA CTC TGG ATT CAG-3′, and LPL forward 5′- CTG GTC AGA CTG GTG GAG CA-3′, reverse 5′- ACA AAT ACC GCA GGT GCC TT-3′ genes were quantified using the 2

−∆∆Ct calculation method [

70].

5.8. Cellular Behavior in Gels

To analyze the possibility of using RD1 gel as a delivery system for cellular therapies, viability of polydactyly fibroblasts and ASC from 3 donors as well as the clinical grade FE002-SK2 primary progenitor fibroblast cell line, primary keratinocytes and HaCaT cells mixed with the gel was evaluated at different time points. To this end, suspensions containing 250,000 cells were centrifuged at 230 × g for 10 mins and the supernatant was removed. Cells were mixed with 250µL of RD1 (1′000 cells/µl) and 100 µL was deposited on the bottom of a 96 well plate. The plate was placed in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under 5% CO

2 for 24, 48, 72 hrs and 1 week, at that time Live/Dead (Biotium, Fremmont, CA) staining was done. 100µl of Live/Dead solution was deposited on the top gel and incubate 30 mins in the incubator at 37 °C under 5% CO

2. After the incubation period, 20 µl of mix of cells in RD1 was transferred on the top of a glass slide and pictures were taken with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX83 microscope With a DP75 camera) using the appropriate filters, GFP: green fluorescence for live cells and TRITC, red fluorescence for dead cells. Cell counting (live and dead cells) was done with the Image J program [

71]. Three experiments were done for each cell source. Results are presented as a percentage of live cells. Supplementary

Figure 4 shows a representative image of the obtained results after Live/Dead staining)

With the same protocol, cellular survival was evaluated in different storage conditions such as 4 °C (in the fridge), room temperature (RT) on the bench (with natural light exposure), RT in the dark and 37 °C (cell culture incubator) for 24 and 48 hrs.

5.9. Cell Delivery Assessment in a (de-epidermialized dermis) DED Model

To assess the potential of cellular delivery of cells mixed with RD1 gel we used a de-epidermialized dermis (DED) model as described previously [

8,

46]. In brief, DED 1.5 cm

2 were taken from stored batches at 4 °C, washed several times with DMEM and incubated for at least 1 hour in Medium 1. Then, DED samples were deposited (reticular dermis facing down) onto a perforated metal support measuring 1 × 1 × 0.5 cm that were placed at the bottom of a 12-well plate. Medium 4 composed by DMEM and Ham’s F12 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at a 3:1 proportion, 0.14 nM cholera toxin (Lubio Science, Zurich, Switzerland), 332.9 ng/mL hydrocortisone (Pfizer, New York, NY, USA), 8.3 ng/mL EGF (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 832.2 µM L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.12 U/mL insulin (Novo Nordisk Pharma, Bagsværd, Danemark), and 10% FBS (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added just to let the top of the dermis uncovered to create an air liquid interface. A glass insert was carefully positioned in the center of the DED with the help of a sterile forceps for the cells suspended in medium, then cells were added on the insert or directly on the DED as follows: (1) 100µL of RD1 mixed with 20,000 FE002-SK2 fibroblasts (2) 100µL of RD1 mixed with 20,000 primary keratinocytes (3) 100µL of RD1 mixed with 20,000 HaCaT cells, (4) 100µL of RD1 mixed with 4′000 FE002-sk2 and 16′000 primary keratinocytes and (5) 100µL of culture medium mixed with 20,000 HaCaT cells as the positive control (see supplementary

Figure S5). The negative control was the DED with no cellular addition. The plates with DEDs were incubated for 3 days at 37 °C and 5% CO

2. Following this period, the inserts were removed, the DED culture medium was refreshed, and the constructs were maintained for 1 week at 37 °C and 5% CO

2. Then, DED samples were stained with MTT to assess cellular viability and homogeneity.

5.10. DED Processing to Evaluate Cellular Attachment and Viability

Cellular attachment and viability were assessed by an MTT staining (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide conversion assay, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The DED were placed into 12-well plates, and 1–2 mL of 0.5 mg/mL MTT in 1xPBS (Bichsel, Unterseen, Switzerland) was added, followed by a 2-hour incubation at 37 °C. After incubation, the samples were rinsed twice with PBS, and imaging was carried out macroscopically using an iPhone 12 Pro Max (Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA). Metabolically active cells appeared stained in purple. The stained DED samples were then fixed in formalin for histological analysis and subsequent hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining of 7 µm sections as described previously [

46]. Pictures were taken with an inverted Olympus IX83 microscope with a DP75 camera.

5.11. Statistical Analysis and Data Presentation

For cell viability and toxicity studies, all the obtained datasets were analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Cellular viability and were converted into percentages of the control, with standard deviations plotted as error bars. Data calculations and/or presentations were performed using the GraphPad Prism® software version 8.3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) or Microsoft Office Powerpoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L, X.C., K.F., R.B., J.F., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; methodology, Z.L., X.C., K.F., R.B., J.F., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; validation, Z.L., X.C., K.F., R.B., J.F., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; formal analysis, Z.L., K.F., R.B., J.F., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; investigation, Z.L., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; resources, K.F., R.B., J.F., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; data curation, Z.L., K.F., R.B., J.F., L.A.A. and N.H.-B writing: original draft preparation L.Z., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; writing, review and editing, Z.L, X.C., K.F., R.B., J.F., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; visualization, Z.L, X.C., K.F., R.B., J.F., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; supervision, K.F., R.B., J.F., L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; project administration, L.A.A. and N.H.-B.; funding acquisition, L.A.A. and N.H.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by TEOXANE SA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The biological starting materials used for the present study were procured according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the appropriate Cantonal Ethics Committee [

61,

62]. The progenitor cell source used in the present study (i.e., FE002-SK2 primary progenitor cells) was established from the FE002 organ donation, as approved by the Vaud Cantonal Ethics Committee (University Hospital of Lausanne–CHUV, Ethics Committee Protocol N 62/07). The FE002 donation was registered under a federal cell transplantation program (i.e., Swiss progenitor cell transplantation program). Obtention and use of patient cellular materials followed the regulations of the Biobank of the CHUV Department of Musculoskeletal Medicine. Materials from adult burn patients were included in the study under the Ethics Committee Protocol N 264/12, approved by the Vaud Cantonal Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Appropriate informed consent was obtained from and confirmed by starting material donors at the time of inclusion in the Swiss progenitor cell transplantation program, following specifically devised protocols and procedures which were validated by the appropriate health authorities. Informed consent (i.e., formalized in a general informed consent agreement) was obtained from all patients or from their legal representatives at the time of treatment for unrestricted use of the gathered and anonymized patient data or anonymized biological materials (i.e., donors of primary cell types).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article files.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Family Sandoz Foundation and Foundation S.A.N.T.E for the continued support for the Transplantation program of burn patients. An addtional thanks is for the generous donation of the FE-002SK2 skin cells this for this specific research project from Prof. Applegate.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Flégeau, Dr. Ballarini, Dr. Brusini, and Dr. Faivre are employees of Teoxane SA, Geneva, Switzerland. Prof. Applegate and Dr. Hirt-Burri have received financial support for the project provided by Teoxane SA. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| DED |

de-epidermized dermis |

| DMEM |

dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| DMSO |

dimethyl sulfoxide |

| CSI |

cell strainer inserts |

| HA |

hyaluronic acid |

| ASC |

adipose stem cells |

| RD1 |

redensity 1 hydrogel |

| ECM |

extracellular matrix |

| FDA |

food and drug administration |

References

- Wood, F. M., M. L. Kolybaba, and P. Allen. “The Use of Cultured Epithelial Autograft in the Treatment of Major Burn Wounds: Eleven Years of Clinical Experience.” Burns 32, no. 5 (2006): 538-44. [CrossRef]

- Cirodde, A., T. Leclerc, P. Jault, P. Duhamel, J. J. Lataillade, and L. Bargues. “Cultured Epithelial Autografts in Massive Burns: A Single-Center Retrospective Study with 63 Patients.” Burns 37, no. 6 (2011): 964-72. [CrossRef]

- Chemali, M., A. Laurent, C. Scaletta, L. Waselle, J. P. Simon, M. Michetti, J. F. Brunet, M. Flahaut, N. Hirt-Burri, W. Raffoul, L. A. Applegate, A. S. de Buys Roessingh, and P. Abdel-Sayed. “Burn Center Organization and Cellular Therapy Integration: Managing Risks and Costs.” J Burn Care Res 42, no. 5 (2021): 911-24. [CrossRef]

- Auxenfans, C., V. Menet, Z. Catherine, H. Shipkov, P. Lacroix, M. Bertin-Maghit, O. Damour, and F. Braye. “Cultured Autologous Keratinocytes in the Treatment of Large and Deep Burns: A Retrospective Study over 15 Years.” Burns 41, no. 1 (2015): 71-9. [CrossRef]

- (WHO), World Health Organization. “Burn Injuries.” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns.

- Sabeh, G., M. Sabe, S. Ishak, and R. Sweid. “[Not Available].” Ann Burns Fire Disasters 31, no. 3 (2018): 213-22.

- Rangatchew, F., P. Vester-Glowinski, B. S. Rasmussen, E. Haastrup, L. Munthe-Fog, M. L. Talman, C. Bonde, K. T. Drzewiecki, A. Fischer-Nielsen, and R. Holmgaard. “Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy of Acute Thermal Burns: A Systematic Review of the Effect on Inflammation and Wound Healing.” Burns 47, no. 2 (2021): 270-94. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., A. Laurent, Z. Liao, S. Jaccoud, P. Abdel-Sayed, M. Flahaut, C. Scaletta, W. Raffoul, L. A. Applegate, and N. Hirt-Burri. “Cutaneous Cell Therapy Manufacturing Timeframe Rationalization: Allogeneic Off-the-Freezer Fibroblasts for Dermo-Epidermal Combined Preparations (De-Fe002-Sk2) in Burn Care.” Pharmaceutics 15, no. 9 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ter Horst, B., G. Chouhan, N. S. Moiemen, and L. M. Grover. “Advances in Keratinocyte Delivery in Burn Wound Care.” Adv Drug Deliv Rev 123 (2018): 18-32. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, B., A. Ekkernkamp, C. Johnen, J. C. Gerlach, C. Belfekroun, and M. V. Kuntscher. “Sprayed Cultured Epithelial Autografts for Deep Dermal Burns of the Face and Neck.” Ann Plast Surg 58, no. 1 (2007): 70-3. [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Vives, R., A. Corcos, M. S. Choi, M. T. Young, P. Over, J. Ziembicki, and J. C. Gerlach. “Cell-Spray Auto-Grafting Technology for Deep Partial-Thickness Burns: Problems and Solutions During Clinical Implementation.” Burns 44, no. 3 (2018): 549-59. [CrossRef]

- Ozhathil, Deepak K, Michael W Tay, Steven E Wolf, and Ludwik K %J Medicina Branski. “A Narrative Review of the History of Skin Grafting in Burn Care.” 57, no. 4 (2021): 380.

- Obeng, M. K., R. L. McCauley, J. R. Barnett, J. P. Heggers, K. Sheridan, and S. S. Schutzler. “Cadaveric Allograft Discards as a Result of Positive Skin Cultures.” Burns 27, no. 3 (2001): 267-71. [CrossRef]

- Bolivar-Flores, Y. J., and W. Kuri-Harcuch. “Frozen Allogeneic Human Epidermal Cultured Sheets for the Cure of Complicated Leg Ulcers.” Dermatol Surg 25, no. 8 (1999): 610-7. [CrossRef]

- Surowiecka, A., A. Chrapusta, M. Klimeczek-Chrapusta, T. Korzeniowski, J. Drukala, and J. Struzyna. “Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Burn Wound Management.” Int J Mol Sci 23, no. 23 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y., Q. Zhang, Y. Peng, X. Qiao, J. Yan, B. Wang, Z. Zhu, Z. Li, and Y. Zhang. “Effect of Stem Cell Treatment on Burn Wounds: A Systemic Review and a Meta-Analysis.” Int Wound J 20, no. 1 (2023): 8-17.

- Lukomskyj, A. O., N. Rao, L. Yan, J. S. Pye, H. Li, B. Wang, and J. J. Li. “Stem Cell-Based Tissue Engineering for the Treatment of Burn Wounds: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Studies.” Stem Cell Rev Rep 18, no. 6 (2022): 1926-55. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., W. D. Xia, L. Van der Merwe, W. T. Dai, and C. Lin. “Efficacy of Stem Cell Therapy for Burn Wounds: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Preclinical Studies.” Stem Cell Res Ther 11, no. 1 (2020): 322. [CrossRef]

- Arno, A., A. H. Smith, P. H. Blit, M. A. Shehab, G. G. Gauglitz, and M. G. Jeschke. “Stem Cell Therapy: A New Treatment for Burns?” Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 4, no. 10 (2011): 1355-80. [CrossRef]

- Abdul Kareem, N., A. Aijaz, and M. G. Jeschke. “Stem Cell Therapy for Burns: Story So Far.” Biologics 15 (2021): 379-97. [CrossRef]

- Weissman, Irving %J Jama. “Stem Cell Research: Paths to Cancer Therapies and Regenerative Medicine.” 294, no. 11 (2005): 1359-66.

- Foubert, P., A. D. Gonzalez, S. Teodosescu, F. Berard, M. Doyle-Eisele, K. Yekkala, M. Tenenhaus, and J. K. Fraser. “Adipose-Derived Regenerative Cell Therapy for Burn Wound Healing: A Comparison of Two Delivery Methods.” Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 5, no. 7 (2016): 288-98. [CrossRef]

- Igura, K., X. Zhang, K. Takahashi, A. Mitsuru, S. Yamaguchi, and T. A. Takashi. “Isolation and Characterization of Mesenchymal Progenitor Cells from Chorionic Villi of Human Placenta.” Cytotherapy 6, no. 6 (2004): 543-53. [CrossRef]

- Soncini, M., E. Vertua, L. Gibelli, F. Zorzi, M. Denegri, A. Albertini, G. S. Wengler, and O. Parolini. “Isolation and Characterization of Mesenchymal Cells from Human Fetal Membranes.” J Tissue Eng Regen Med 1, no. 4 (2007): 296-305. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S., S. Mansoor, A. Ayub, M. Ejaz, H. Zafar, F. Feroz, A. Khan, and M. Ali. “An Update on Stem Cells Applications in Burn Wound Healing.” Tissue Cell 72 (2021): 101527. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, M. A., N. J. Walker, E. Napoli, and D. L. Borjesson. “Evaluation of Senescence in Mesenchymal Stem Cells Isolated from Equine Bone Marrow, Adipose Tissue, and Umbilical Cord Tissue.” Stem Cells Dev 21, no. 2 (2012): 273-83. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., X. Xu, X. Lei, J. Tan, and H. Xie. “Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Burn Wound Healing.” Burns Trauma 9 (2021): tkab002. [CrossRef]

- Shpichka, Anastasia, Denis Butnaru, Evgeny A Bezrukov, Roman B Sukhanov, Anthony Atala, Vitaliy Burdukovskii, Yuanyuan Zhang, Peter %J Stem cell research Timashev, and therapy. “Skin Tissue Regeneration for Burn Injury.” 10, no. 1 (2019): 94. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A., P. Lin, C. Scaletta, N. Hirt-Burri, M. Michetti, A. S. de Buys Roessingh, W. Raffoul, B. R. She, and L. A. Applegate. “Bringing Safe and Standardized Cell Therapies to Industrialized Processing for Burns and Wounds.” Front Bioeng Biotechnol 8 (2020): 581. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. J., J. Pieper, R. Schotel, C. A. van Blitterswijk, and E. N. Lamme. “Stimulation of Skin Repair Is Dependent on Fibroblast Source and Presence of Extracellular Matrix.” Tissue Eng 10, no. 7-8 (2004): 1054-64.

- Zhifeng, Liao, Chen Xi, Hirt-Burri Nathalie, Porcello Alexandre, Marques Cíntia, Kelly Lourenço, Laurent Alexis, and Ann Applegate Lee. “Pharmacological and Biological Strategies as Regulators of Scarless Wound Healing and Regeneration of Skin.” In Wound Healing - Mechanisms and Pharmacological Interventions, edited by Guadalupe Tirma González-Mateo and Valeria Kopytina. London: IntechOpen, 2025.

- Cerceo, J. R., A. Malkoc, A. Nguyen, A. Daoud, D. T. Wong, and B. Woodward. “Management of Large Full-Thickness Burns Using Kerecis Acellular Fish Skin Graft and Recell Autologous Skin Cell Suspension: A Case Report of Two Patients with Large Surface Area Burns.” Cureus 16, no. 10 (2024): e71101. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B. K., Z. Siprashvili, and P. A. Khavari. “Advances in Skin Grafting and Treatment of Cutaneous Wounds.” Science 346, no. 6212 (2014): 941-5. [CrossRef]

- Porcello, A., A. Laurent, N. Hirt-Burri, P. Abdel-Sayed, A. de Buys Roessingh, W. Raffoul, O. Jordan, E. Allémann, and L.A. Applegate. “Hyaluronan-Based Hydrogels as Functional Vectors for Standardised Therapeutics in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine.” CRC Press, 2022.

- Sun, G, YI Shen, and JW Harmon. “Engineering Pro-Regenerative Hydrogels for Scarless Wound Healing, Adv. Healthc. Mater. 7 (2018) 1–12.”. [CrossRef]

- Longinotti, C. “The Use of Hyaluronic Acid Based Dressings to Treat Burns: A Review.” Burns Trauma 2, no. 4 (2014): 162-8. [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, F., A. Saparov, and M. Riccio. “Hyaluronic Acid Accelerates Re-Epithelialization and Healing of Acute Cutaneous Wounds.” Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 27, no. 3 Suppl (2023): 37-45. [CrossRef]

- Bezpalko, L., and A. Filipskiy. “Clinical and Ultrasound Evaluation of Skin Quality after Subdermal Injection of Two Non-Crosslinked Hyaluronic Acid-Based Fillers.” Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 16 (2023): 2175-83. [CrossRef]

- Fanian, Ferial. “In-Vivo Injection of Oligonutrients and High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid - Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Aesthetic Medicine 3 (2017): 23-33.

- Abdel-Sayed, P., N. Hirt-Burri, A. de Buys Roessingh, W. Raffoul, and L. A. Applegate. “Evolution of Biological Bandages as First Cover for Burn Patients.” Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 8, no. 11 (2019): 555-64. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dourobi, K., A. Laurent, L. Deghayli, M. Flahaut, P. Abdel-Sayed, C. Scaletta, M. Michetti, L. Waselle, J. P. Simon, O. E. Ezzi, W. Raffoul, L. A. Applegate, N. Hirt-Burri, and A. S. B. Roessingh. “Retrospective Evaluation of Progenitor Biological Bandage Use: A Complementary and Safe Therapeutic Management Option for Prevention of Hypertrophic Scarring in Pediatric Burn Care.” Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 14, no. 3 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A., M. Rey, C. Scaletta, P. Abdel-Sayed, M. Michetti, M. Flahaut, W. Raffoul, A. de Buys Roessingh, N. Hirt-Burri, and L. A. Applegate. “Retrospectives on Three Decades of Safe Clinical Experience with Allogeneic Dermal Progenitor Fibroblasts: High Versatility in Topical Cytotherapeutic Care.” Pharmaceutics 15, no. 1 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A., C. Scaletta, M. Michetti, N. Hirt-Burri, A. S. de Buys Roessingh, W. Raffoul, and L. A. Applegate. “Gmp Tiered Cell Banking of Non-Enzymatically Isolated Dermal Progenitor Fibroblasts for Allogenic Regenerative Medicine.” Methods Mol Biol 2286 (2021): 25-48.

- Laurent, A., C. Scaletta, M. Michetti, N. Hirt-Burri, M. Flahaut, W. Raffoul, A. S. de Buys Roessingh, and L. A. Applegate. “Progenitor Biological Bandages: An Authentic Swiss Tool for Safe Therapeutic Management of Burns, Ulcers, and Donor Site Grafts.” Methods Mol Biol 2286 (2021): 49-65.

- Chen, X., N. Hirt-Burri, C. Scaletta, A. E. Laurent, and L. A. Applegate. “Bicomponent Cutaneous Cell Therapy for Early Burn Care: Manufacturing Homogeneity and Epidermis-Structuring Functions of Clinical Grade Fe002-Sk2 Allogeneic Dermal Progenitor Fibroblasts.” Pharmaceutics 17, no. 6 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., C. Scaletta, Z. Liao, A. Laurent, L. A. Applegate, and N. Hirt-Burri. “Optimization and Standardization of Stable De-Epidermized Dermis (Ded) Models for Functional Evaluation of Cutaneous Cell Therapies.” Bioengineering (Basel) 11, no. 12 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., L. A. Garza, S. Kang, J. Varani, J. S. Orringer, G. J. Fisher, and J. J. Voorhees. “In Vivo Stimulation of De Novo Collagen Production Caused by Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid Dermal Filler Injections in Photodamaged Human Skin.” Arch Dermatol 143, no. 2 (2007): 155-63. [CrossRef]

- Iannitti, T., J. C. Morales-Medina, A. Coacci, and B. Palmieri. “Experimental and Clinical Efficacy of Two Hyaluronic Acid-Based Compounds of Different Cross-Linkage and Composition in the Rejuvenation of the Skin.” Pharm Res 33, no. 12 (2016): 2879-90. [CrossRef]

- Quan, T., F. Wang, Y. Shao, L. Rittie, W. Xia, J. S. Orringer, J. J. Voorhees, and G. J. Fisher. “Enhancing Structural Support of the Dermal Microenvironment Activates Fibroblasts, Endothelial Cells, and Keratinocytes in Aged Human Skin in Vivo.” J Invest Dermatol 133, no. 3 (2013): 658-67. [CrossRef]

- Nadra, K., M. Andre, E. Marchaud, P. Kestemont, F. Braccini, H. Cartier, M. Keophiphath, and F. Fanian. “A Hyaluronic Acid-Based Filler Reduces Lipolysis in Human Mature Adipocytes and Maintains Adherence and Lipid Accumulation of Long-Term Differentiated Human Preadipocytes.” J Cosmet Dermatol 20, no. 5 (2021): 1474-82. [CrossRef]

- Grognuz, A., C. Scaletta, A. Farron, D. P. Pioletti, W. Raffoul, and L. A. Applegate. “Stability Enhancement Using Hyaluronic Acid Gels for Delivery of Human Fetal Progenitor Tenocytes.” Cell Med 8, no. 3 (2016): 87-97. [CrossRef]

- Hohlfeld, J., A. de Buys Roessingh, N. Hirt-Burri, P. Chaubert, S. Gerber, C. Scaletta, P. Hohlfeld, and L. A. Applegate. “Tissue Engineered Fetal Skin Constructs for Paediatric Burns.” Lancet 366, no. 9488 (2005): 840-2. [CrossRef]

- Dalmedico, M. M., M. J. Meier, J. V. Felix, F. S. Pott, F. Petz Fde, and M. C. Santos. “Hyaluronic Acid Covers in Burn Treatment: A Systematic Review.” Rev Esc Enferm USP 50, no. 3 (2016): 522-8. [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, R. V., S. L. James, and S. E. James. “A Review of Tissue-Engineered Skin Bioconstructs Available for Skin Reconstruction.” J R Soc Interface 7, no. 43 (2010): 229-58.

- Tezel, A., and G. H. Fredrickson. “The Science of Hyaluronic Acid Dermal Fillers.” J Cosmet Laser Ther 10, no. 1 (2008): 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Turner, N. J., C. M. Kielty, M. G. Walker, and A. E. Canfield. “A Novel Hyaluronan-Based Biomaterial (Hyaff-11) as a Scaffold for Endothelial Cells in Tissue Engineered Vascular Grafts.” Biomaterials 25, no. 28 (2004): 5955-64. [CrossRef]

- Fino, P., A. M. Spagnoli, M. Ruggieri, and M. G. Onesti. “Caustic Burn Caused by Intradermal Self Administration of Muriatic Acid for Suicidal Attempt: Optimal Wound Healing and Functional Recovery with a Non Surgical Treatment.” G Chir 36, no. 5 (2015): 214-8.

- Gravante, G., R. Sorge, A. Merone, A. M. Tamisani, A. Di Lonardo, A. Scalise, G. Doneddu, D. Melandri, G. Stracuzzi, M. G. Onesti, P. Cerulli, R. Pinn, and G. Esposito. “Hyalomatrix Pa in Burn Care Practice: Results from a National Retrospective Survey, 2005 to 2006.” Ann Plast Surg 64, no. 1 (2010): 69-79.

- Harris, P. A., F. di Francesco, D. Barisoni, I. M. Leigh, and H. A. Navsaria. “Use of Hyaluronic Acid and Cultured Autologous Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts in Extensive Burns.” Lancet 353, no. 9146 (1999): 35-6. [CrossRef]

- Price, R. D., M. G. Berry, and H. A. Navsaria. “Hyaluronic Acid: The Scientific and Clinical Evidence.” J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 60, no. 10 (2007): 1110-9. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J., and V. R. Driver. “Hyaluronic Acid Derivatives and Their Healing Effect on Burns, Epithelial Surgical Wounds, and Chronic Wounds: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Wound Repair Regen 20, no. 3 (2012): 317-31. [CrossRef]

- Jones, Annie, and David Vaughan. “Hydrogel Dressings in the Management of a Variety of Wound Types: A Review.” Journal of Orthopaedic Nursing 9 (2005): S1-S11. [CrossRef]

- Mesa, F. L., J. Aneiros, A. Cabrera, M. Bravo, T. Caballero, F. Revelles, R. G. del Moral, and F. O’Valle. “Antiproliferative Effect of Topic Hyaluronic Acid Gel. Study in Gingival Biopsies of Patients with Periodontal Disease.” Histol Histopathol 17, no. 3 (2002): 747-53. [CrossRef]

- Witting, M., A. Boreham, R. Brodwolf, K. Vavrova, U. Alexiev, W. Friess, and S. Hedtrich. “Interactions of Hyaluronic Acid with the Skin and Implications for the Dermal Delivery of Biomacromolecules.” Mol Pharm 12, no. 5 (2015): 1391-401. [CrossRef]

- Dicker, K. T., L. A. Gurski, S. Pradhan-Bhatt, R. L. Witt, M. C. Farach-Carson, and X. Jia. “Hyaluronan: A Simple Polysaccharide with Diverse Biological Functions.” Acta Biomater 10, no. 4 (2014): 1558-70. [CrossRef]

- Khademhosseini, A., G. Eng, J. Yeh, J. Fukuda, J. Blumling, 3rd, R. Langer, and J. A. Burdick. “Micromolding of Photocrosslinkable Hyaluronic Acid for Cell Encapsulation and Entrapment.” J Biomed Mater Res A 79, no. 3 (2006): 522-32.

- Thones, S., L. M. Kutz, S. Oehmichen, J. Becher, K. Heymann, A. Saalbach, W. Knolle, M. Schnabelrauch, S. Reichelt, and U. Anderegg. “New E-Beam-Initiated Hyaluronan Acrylate Cryogels Support Growth and Matrix Deposition by Dermal Fibroblasts.” Int J Biol Macromol 94, no. Pt A (2017): 611-20. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J. J., J. Rowley, and H. J. Kong. “Hydrogels Used for Cell-Based Drug Delivery.” J Biomed Mater Res A 87, no. 4 (2008): 1113-22. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z., N. Laurent, N. Hirt-Burri, C. Scaletta, P. Abdel-Sayed, W. Raffoul, S. Luo, D. J. Krysan, A. Laurent, and L. A. Applegate. “Sustainable Primary Cell Banking for Topical Compound Cytotoxicity Assays: Protocol Validation on Novel Biocides and Antifungals for Optimized Burn Wound Care.” Eur Burn J 5, no. 3 (2024): 249-70. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. “Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative Pcr and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method.” Methods 25, no. 4 (2001): 402-8.

- Schneider, C. A., W. S. Rasband, and K. W. Eliceiri. “Nih Image to Imagej: 25 Years of Image Analysis.” Nat Methods 9, no. 7 (2012): 671-5. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

RD1 cytotoxicity assay. CellTiter results of cytotoxicity assay of RD1 gel on ASCs, polydactyly primary fibroblasts, and FE002-SK2 progenitor fibroblasts cells. Cellular viability is shown as a % of the control (i.e., untreated cells in growth medium). IC50 for ASC cells (25.48%), fibroblasts (45.56%) and FE002-SK2 (60.33%). ASC, adipose stem cells. The doted line corresponds to the regulatory treshold at 70% of viability vs CTRL.

Figure 1.

RD1 cytotoxicity assay. CellTiter results of cytotoxicity assay of RD1 gel on ASCs, polydactyly primary fibroblasts, and FE002-SK2 progenitor fibroblasts cells. Cellular viability is shown as a % of the control (i.e., untreated cells in growth medium). IC50 for ASC cells (25.48%), fibroblasts (45.56%) and FE002-SK2 (60.33%). ASC, adipose stem cells. The doted line corresponds to the regulatory treshold at 70% of viability vs CTRL.

Figure 2.

Cellular growth evaluation by cellular enumeration at day 4 and day 7 of polydactyly primary ASCs and fibroblastss cultured in their respective growth medium with the presence of a CSI, with or without 100 µL RD1 gel. Four independent experiments were performed and results are presented as a percent of control cells. Statistical differences between the CSI and the CSI + 100µL RD1 are represented as * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Cellular growth evaluation by cellular enumeration at day 4 and day 7 of polydactyly primary ASCs and fibroblastss cultured in their respective growth medium with the presence of a CSI, with or without 100 µL RD1 gel. Four independent experiments were performed and results are presented as a percent of control cells. Statistical differences between the CSI and the CSI + 100µL RD1 are represented as * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 3.

Collagen production: effect of 100 µl of RD1 on fibroblasts. (A.) Example of Sirius Red staining of polydactyly fibroblasts post-7 days exposure to 100 µl of RD1 or 10−4 M Vitamin C. Scale bars = 400 nm (B.) Collagen quantification is presented as % of control (CSI alone). (C.) Raw OD560 visible absorbance (wich corresponds to collagen content) of one experiment where both primary cell lines were treated in parallel. FE002-SK2 show a higher relative and innate quantity of collagen.. Statistical differences are represented as * p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Collagen production: effect of 100 µl of RD1 on fibroblasts. (A.) Example of Sirius Red staining of polydactyly fibroblasts post-7 days exposure to 100 µl of RD1 or 10−4 M Vitamin C. Scale bars = 400 nm (B.) Collagen quantification is presented as % of control (CSI alone). (C.) Raw OD560 visible absorbance (wich corresponds to collagen content) of one experiment where both primary cell lines were treated in parallel. FE002-SK2 show a higher relative and innate quantity of collagen.. Statistical differences are represented as * p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of adipogenic potential of 100 µL RD1 on polydactyly ASC primary cells. (Left) Representative images of the Oil red O staining for one polydactyly ASC cell line. Scale bar = 100 μm. (Right), relative mRNA expression of LPL and PPAR-γ genes. Three polydactyly ASC cell lines were cultured for 14 days in adipocyte differentiation medium (Diff Med), CSI with 100 µl RD1 in culture medium (RD1) and with culture medium (CTRL-).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of adipogenic potential of 100 µL RD1 on polydactyly ASC primary cells. (Left) Representative images of the Oil red O staining for one polydactyly ASC cell line. Scale bar = 100 μm. (Right), relative mRNA expression of LPL and PPAR-γ genes. Three polydactyly ASC cell lines were cultured for 14 days in adipocyte differentiation medium (Diff Med), CSI with 100 µl RD1 in culture medium (RD1) and with culture medium (CTRL-).

Figure 5.

Live/Dead evaluation of cellular survival in RD1 gel. 100,000 cells were mixed with 100 µL of RD1, deposited in 96-well plates and kept at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator. Live/Dead staining was performed after 24, 48, 72 hrs or 1 week. Experiments were done in triplicate. The red doted rectangle illutrates the range of cellular viability usually accepted for cell therapies.

Figure 5.

Live/Dead evaluation of cellular survival in RD1 gel. 100,000 cells were mixed with 100 µL of RD1, deposited in 96-well plates and kept at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator. Live/Dead staining was performed after 24, 48, 72 hrs or 1 week. Experiments were done in triplicate. The red doted rectangle illutrates the range of cellular viability usually accepted for cell therapies.

Figure 6.

Live/Dead evaluation of polydactyly fibroblast, FE002-SK2 clinical cells and adult keratinocye cell survival in RD1 stored in different conditons after 24 hrs. 100,000 cells were mixed with 100 µL of RD1, deposited in 96-well plates and kept at 4 °C, RT, RT in the dark and 37 °C in a cell culture incubator. Live/Dead staining was performed after 24 hrs. Experiments were done in triplicate.

Figure 6.

Live/Dead evaluation of polydactyly fibroblast, FE002-SK2 clinical cells and adult keratinocye cell survival in RD1 stored in different conditons after 24 hrs. 100,000 cells were mixed with 100 µL of RD1, deposited in 96-well plates and kept at 4 °C, RT, RT in the dark and 37 °C in a cell culture incubator. Live/Dead staining was performed after 24 hrs. Experiments were done in triplicate.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of HaCaT cellular delivery on a DED model. 1.5 cm2 DED were taken from stored batches at 4 °C and deposited reticular dermis facing down onto a perforated metal support. A glass insert was carefully positioned in the center of the DED, cells suspended in medium or RD1 were added on the insert. DEDs were incubated for 3 days, then the inserts were removed, the constructs were maintained for 1 additional week at 37 °C and 5% CO2. DED samples were stained with MTT to assess cellular viability and homogeneity. The MTT stained DED samples were then fixed in formalin for histological analysis and sub-sequent hematoxylin & eosin (H&E). (left) Macroscopic images of MTT staining of DED samples, (right) H&E staining of cross-sections of the DED samples 100,000 HaCaT cells were mixed with 100 µL of RD1 and 50 µL of the mixture was deposited on the bottom of the DED, 50,000 HaCaT cells in medium were deposited on a glass insert on the bottom of the DED; CTRL- Negative control DED with no cells. Scale bar = 50µm.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of HaCaT cellular delivery on a DED model. 1.5 cm2 DED were taken from stored batches at 4 °C and deposited reticular dermis facing down onto a perforated metal support. A glass insert was carefully positioned in the center of the DED, cells suspended in medium or RD1 were added on the insert. DEDs were incubated for 3 days, then the inserts were removed, the constructs were maintained for 1 additional week at 37 °C and 5% CO2. DED samples were stained with MTT to assess cellular viability and homogeneity. The MTT stained DED samples were then fixed in formalin for histological analysis and sub-sequent hematoxylin & eosin (H&E). (left) Macroscopic images of MTT staining of DED samples, (right) H&E staining of cross-sections of the DED samples 100,000 HaCaT cells were mixed with 100 µL of RD1 and 50 µL of the mixture was deposited on the bottom of the DED, 50,000 HaCaT cells in medium were deposited on a glass insert on the bottom of the DED; CTRL- Negative control DED with no cells. Scale bar = 50µm.

Figure 8.

Evaluation of cell delivery on a DED model. Progenitor primary fibroblasts (FE002-SK2) and/or keratinocytes cells were deposited on the top of a decellularized skin. (A.) Macroscopic images of MTT staining of DED samples with cells mixed with RD1 without medium and the H&E staining of cross-sections of the DED samples. (B.) Macroscopic images of MTT staining of DED samples with cells seeded on top of the DED in medium and the H&E staining of cross-sections of the DED samples. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 8.

Evaluation of cell delivery on a DED model. Progenitor primary fibroblasts (FE002-SK2) and/or keratinocytes cells were deposited on the top of a decellularized skin. (A.) Macroscopic images of MTT staining of DED samples with cells mixed with RD1 without medium and the H&E staining of cross-sections of the DED samples. (B.) Macroscopic images of MTT staining of DED samples with cells seeded on top of the DED in medium and the H&E staining of cross-sections of the DED samples. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 9.

Proposed workflow for burn management with cells delivered in RD1 gel. (A.) Burned patient arrival, after burn evaluation a biopsy is taken for autologous fibroblast and keratinocyte cell culture (B.) Progenitor FE002-SK2 cells are thawed, cells can either be used directly or if more cells are needed for large burn surfaces, a maximum of 1 week to reach de desired cellular amount for treatment. Cellular amplification autologous fibroblasts and keratinocyte need around 4 and 6 weeks respectively to reach enough cells for patient treatment. (C.) The day of the treatment, either cellular combination can be prepared by mixing cultured cells with RD1 gel and transfer cells to the operating room. (D.) Gel with cells should be applied during the first 24 hrs after preparation.

Figure 9.

Proposed workflow for burn management with cells delivered in RD1 gel. (A.) Burned patient arrival, after burn evaluation a biopsy is taken for autologous fibroblast and keratinocyte cell culture (B.) Progenitor FE002-SK2 cells are thawed, cells can either be used directly or if more cells are needed for large burn surfaces, a maximum of 1 week to reach de desired cellular amount for treatment. Cellular amplification autologous fibroblasts and keratinocyte need around 4 and 6 weeks respectively to reach enough cells for patient treatment. (C.) The day of the treatment, either cellular combination can be prepared by mixing cultured cells with RD1 gel and transfer cells to the operating room. (D.) Gel with cells should be applied during the first 24 hrs after preparation.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).