1. Introduction

Around the world, increasing regulatory influences on artificial intelligence (AI) impose new requirements regarding trustworthiness on AI systems. For different stakeholders, such as the United Nations

1, OECD

2, or governments

3, the use of AI is subject of critical examinations regarding aspects such as transparency, explainability, reliability, quality, or sustainability, culminating in regulations such as the European Union’s AI Act (EU regulation 2024/1689) [

1]. At the same time, AI comes with promising approaches to mastering domain-specific complexities at scale. This paper takes its motivation from the domain of requirements engineering (RE) in the automotive industry, where in system development huge sets of requirements need to be processed using interlinked AI methods in order to support homologation. Hence, AI-influenced results contribute to the shaping of the final product, where other leading regulations apply. In view of the AI-related regulatory aspects, this implies that in their structure and functioning AI systems need to fulfill various criteria to be used in such domains. This paper aims at the requirements for an ontology that enables the provision of different kinds of explanations by complex AI systems in support of their trustworthiness and of their end-to-end explainability along the entire system development.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the background of the domain while

Section 3 addresses relevant regulatory influences.

Section 4 describes necessary capabilities and relevant dimensions.

Section 5 investigates related work while

Section 6 derives general requirements.

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Initial Situation

In the automotive domain, requirements for the design and manufacturing of products, i.e., vehicles, are typically given in text form and often detailed by multimodal artifacts such as tables, figures, equations, or diagrams, and follow regulations and standards [

2,

3]. Initiated by the original equipment manufacturer (OEM), the requirements are extended along the supply chain by Tier-n suppliers, using requirements management systems. Based on these requirements and their interpretation by requirement engineers, downstream developers, and engineers, the development processes and tools for both products and corresponding production systems, and finally the manufacturing of the products, are influenced [

4]. In automotive, system development typically follows the V-model of ISO/IEC 330xx [

5] resp. ASPICE [

6], which define a well-structured development process. For the final products, eventually, the goal is to obtain road permission, and hence meeting homologation requirements [

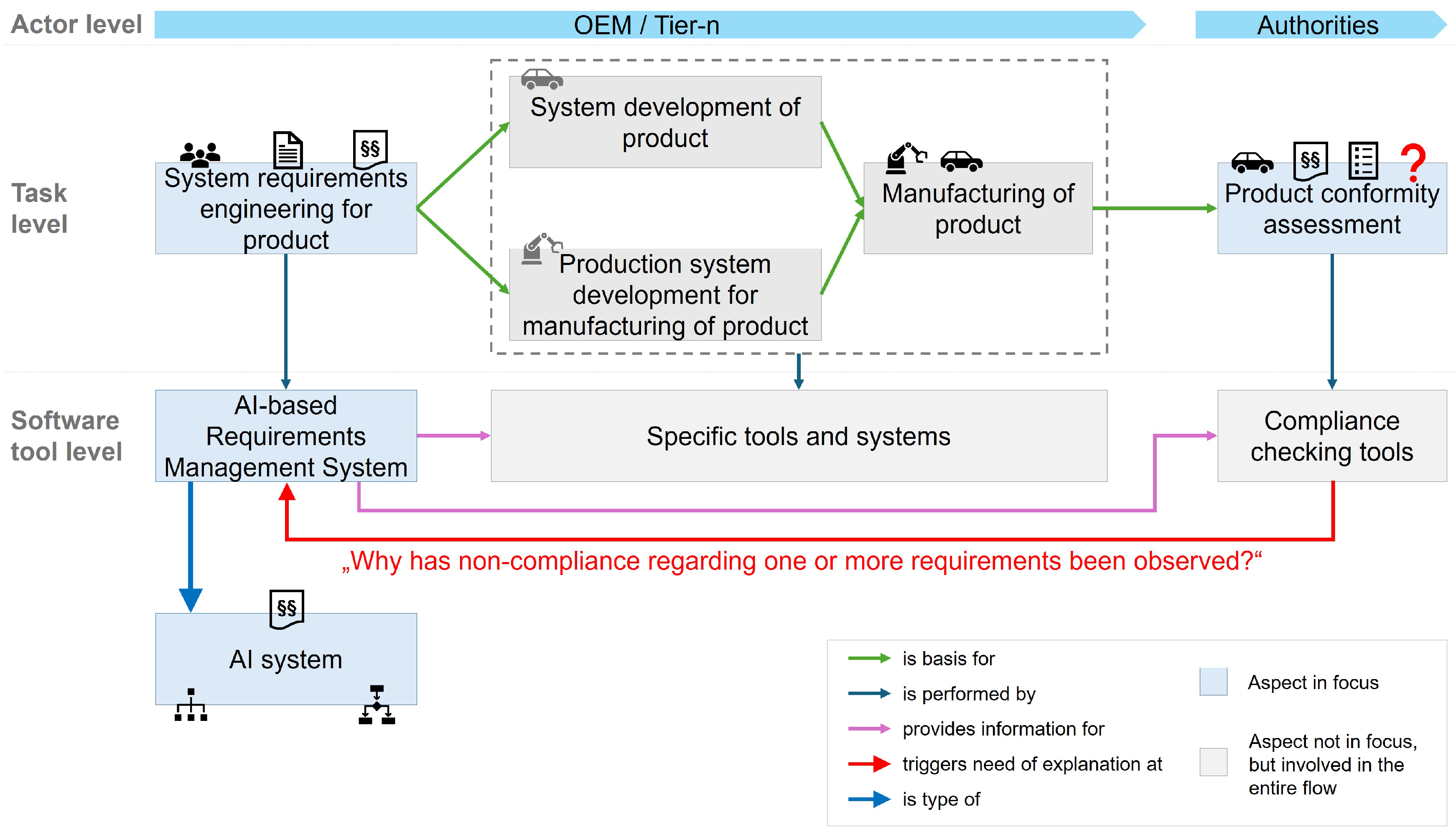

7], which is documented by the passing of product conformity assessments. Such describe, e.g., limits for values for the operation of vehicles or subsystem properties, and whether these are adhered to using standardized tests. Likewise provided as texts or tables, these requirements’ formats and languages additionally depend on the respective country and the testing organization, which adds to the complexity. In case of failed conformity tests, assessing requirements for explanations is common. In addition, the entire domain is characterized by the longevity of the systems, knowledge, data, and products involved. This interplay is outlined in

Figure 1.

Due to the increasing complexity of vehicles, the numbers of related requirements typically range in thousands of interlinked items [

8,

9,

10]. This exceeds human capabilities to efficiently handle such complexities and increases both the risks of errors and the development time. In order to tackle these challenges, AI-based approaches are considered promising and are introduced into RE. The requirements themselves must be interpreted on different levels, i.e., they must be syntactically, semantically, and logically consistent [

11,

12,

13,

14]. In equipping requirements engineers with suitable AI-based functionalities, [

15,

16] identified two key challenges:

Homologation check, addressing the key question "Are the requirements fulfilled?"

MBSE support, addressing the key question "Are the requirements consistent?"

To address these challenges of requirements engineers, specific AI-based functionalities were developed in alignment with the common requirement engineers’ workflows:

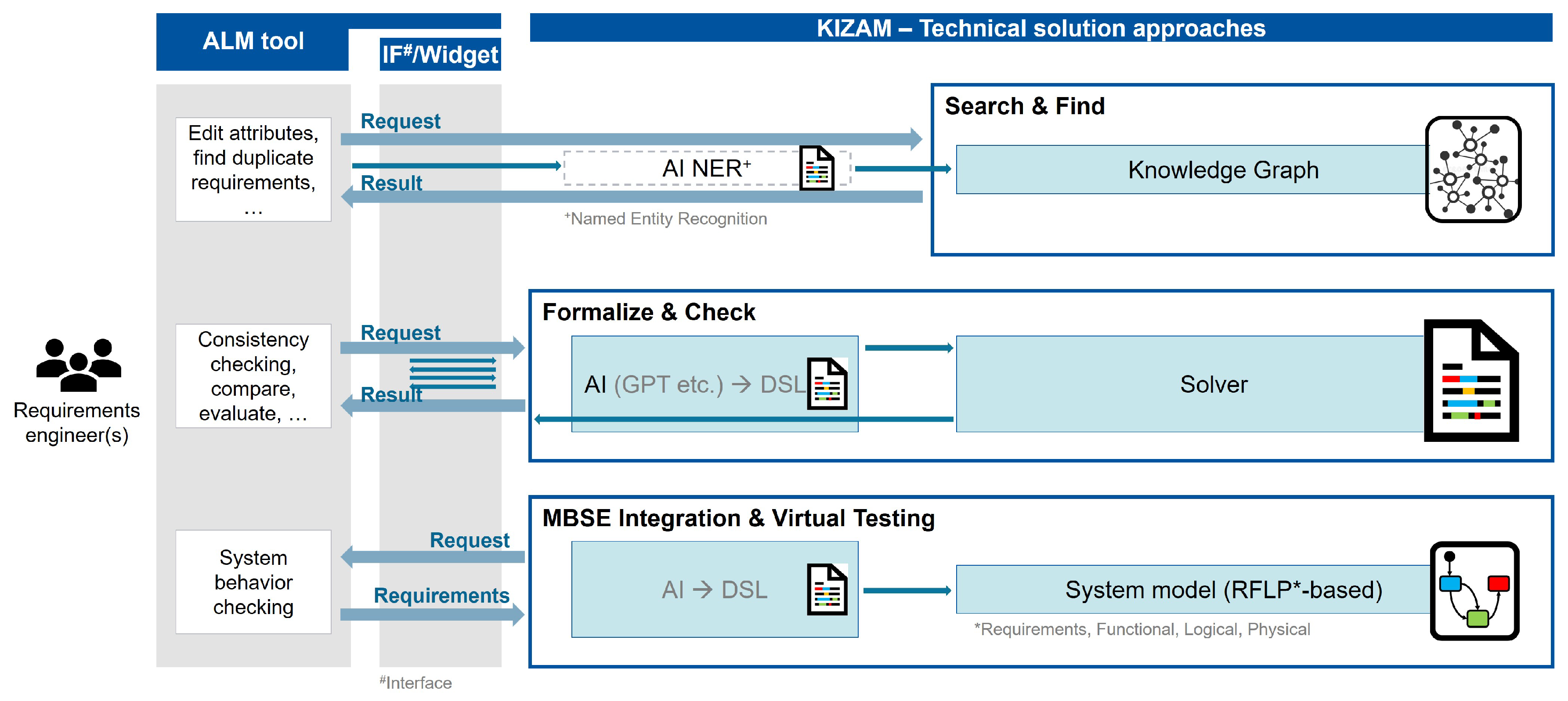

Search & Find: Finding semantically and contextually interrelated requirements.

Formalize & Check: Evaluating and checking the logical consistency of requirements.

MBSE Integration & Virtual Testing: Translation of requirements to MBSE artifacts for downstream reuse.

Each of these uses special AI methods, ranging from natural language processing capabilities over logical validation to SysML-from-text generation. These functionalities were offered via AI-based pipelines on the overall requirements corpus (see

Figure 2).

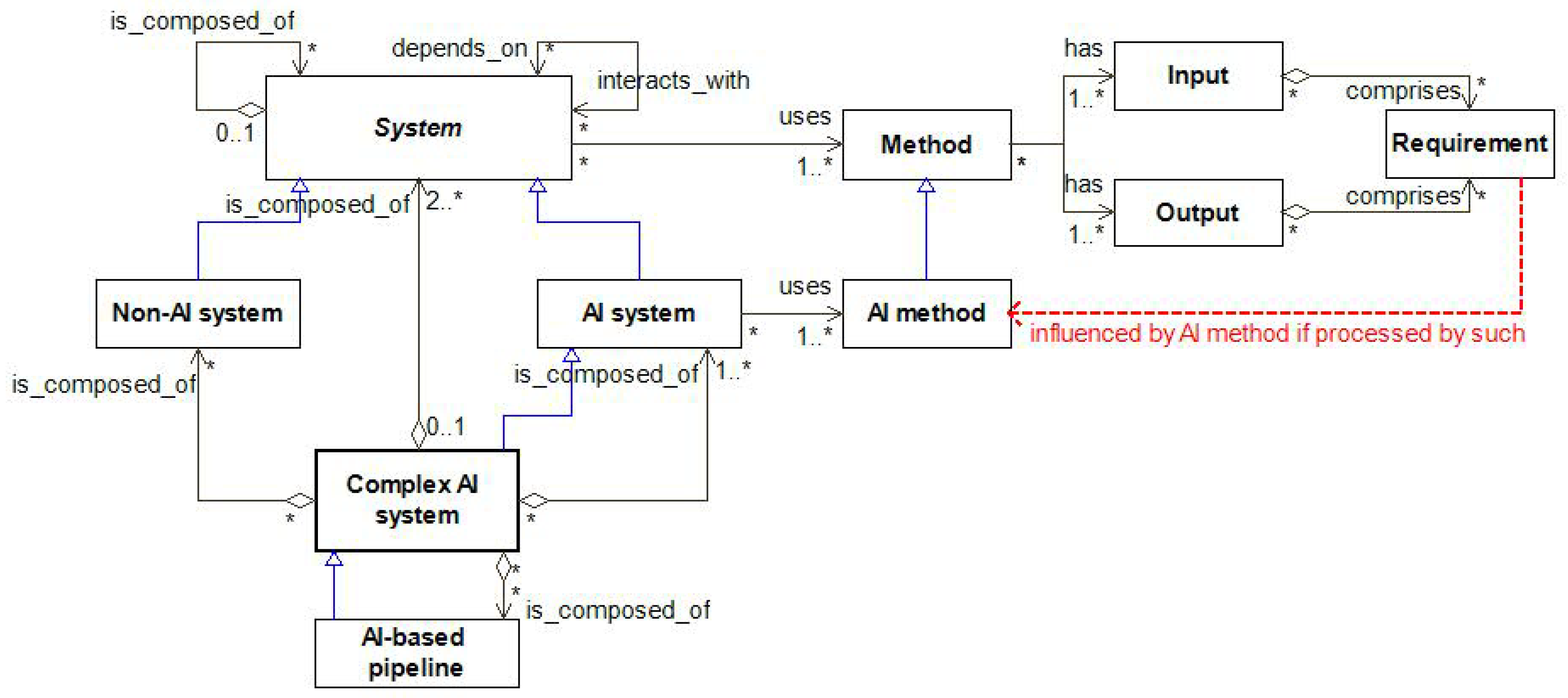

In view of the high demands for knowledge processing in the domain, a key insight is that there is no single AI method nor AI system that can handle all challenges. Instead, combinations and pipelines of interrelated AI methods with special capabilities must be used to address the different needs. In consequence, this makes RE systems complex AI systems in the sense of system composition. In that, a complex AI system is composed of at least two systems, i.e., subsystems, with at least one of them being an AI system, i.e., a system using at least one AI method, and the input and output being requirements that may be influenced, modified, or generated by means of AI methods (see

Figure 3). Here, this dependency (indicated in red) between requirements and AI methods is subject to trustworthiness considerations.

Although being partially orchestrated by the pipelines they are part of, the overall orchestration of the AI (sub)systems effectively depends on the human interaction with the RE tool. This introduces an element of randomness into the AI-based requirements processing flows. Considering today’s already strong demands for compliance in the domain combined with the fast-pace evolution in AI capabilities and shorter AI system lifecycles, this raises the question of how the explainability of such complex AI systems can be continuously safeguarded along their entire lifecycles and those of the products that were built using them.

3. Regulatory Influences

Considering the two challenges from

Section 2, the main regulatory influences come from homologation and AI.

For the automotive industry, obtaining roadworthiness status for products, i.e., vehicles, or parts, and thus international markets access is paramount. Homologation is the mandatory, jurisdiction-dependent official process to check, ensure, and document that all respective legal requirements are met in order to declare the roadworthiness of a vehicle [

17]. In that, it addresses specific safety-related parts of a vehicle. The parts to be taken into account and how they need to be tested depend on the country; however, leading international regulations apply. In the case of the European Union these are prescribed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) [

7], comprise more than 160 individual regulations, and are mutually recognized by other jurisdictions to varying degrees. In total, this forms a highly complex body of interrelated regulatory influences whose fulfillment becomes even more challenging due to vehicles being able to move between different countries.

Introducing AI into the system development process and tools constitutes a shaping influence on the design and manufacturing of vehicles or parts. However, AI is increasingly subject to regulatory influences worldwide. Within the European Union as the market of origin, these influences mainly originate from the AI Act (EU regulation 2024/1689) and the associated regulatory landscape (see [

18], chapter 1.4). By equipping software tools with AI functionalities these tools become AI systems according to the EU AI Act (AI Act, Article 3(1)). Thus, at least minimum transparency obligations apply (AI Act, Article 50). Since AI-based results of RE are used for product design, manufacturing, and permission of operation, impacts from AI and product liability also apply to such AI systems. Given that along the entire RE value chain the involved AI systems may be composed from other AI systems, continuous explainability needs to be ensured, also throughout the entire AI systems’ lifecycles.

At the same time, the legal requirements regarding homologation need to be unchangedly met and potential discrepancies explained. Hence, RE toolchains must support the required explainability. The use of AI then imposes additional constraints, ranging from the interlinking of AI-based functionalities to the user interface level. Furthermore, due to global operations of OEMs and their supply chains, the use of AI-based RE in jurisdictions other than the EU must also be considered.

4. Necessary Capabilities

Due to the increasing complexity of requirements management, tasks will increasingly be supported by machine learning techniques, which have proven effective in decision-making in sensitive areas [

19]. Also, the use of AI systems must comply with the growing number of regulatory influences from homologation and AI to obtain approval in various markets [

20]. To be trustworthy, AI systems need to support different users with explanations tailored to their needs [

21]. Therefore, a solution must have specific capabilities that are precisely aligned with the explanation requirements of different users to gain trust and avoid a mismatch between expectation and reality [

22].

The challenges in the automotive industry described in

Section 2 can be broken down into various use cases on working level. The overarching goal of the identified use cases is to reduce repetitive tasks in requirements management to increase efficiency in an increasingly complex automotive development environment. For example, changes in various requirements documents need to be identified to locate changes in different development stages. Other use cases require the comparison of documents from different domains to uncover connections between text segments or address the automatic extraction of requirements from textual documents. To systematically specify these capabilities, a closer look at the characteristics of the use cases and the respective complexity of the explanation task is necessary. Hence, a systematization of explanation use cases and associated user stories in an orientation framework is well suited for this purpose.

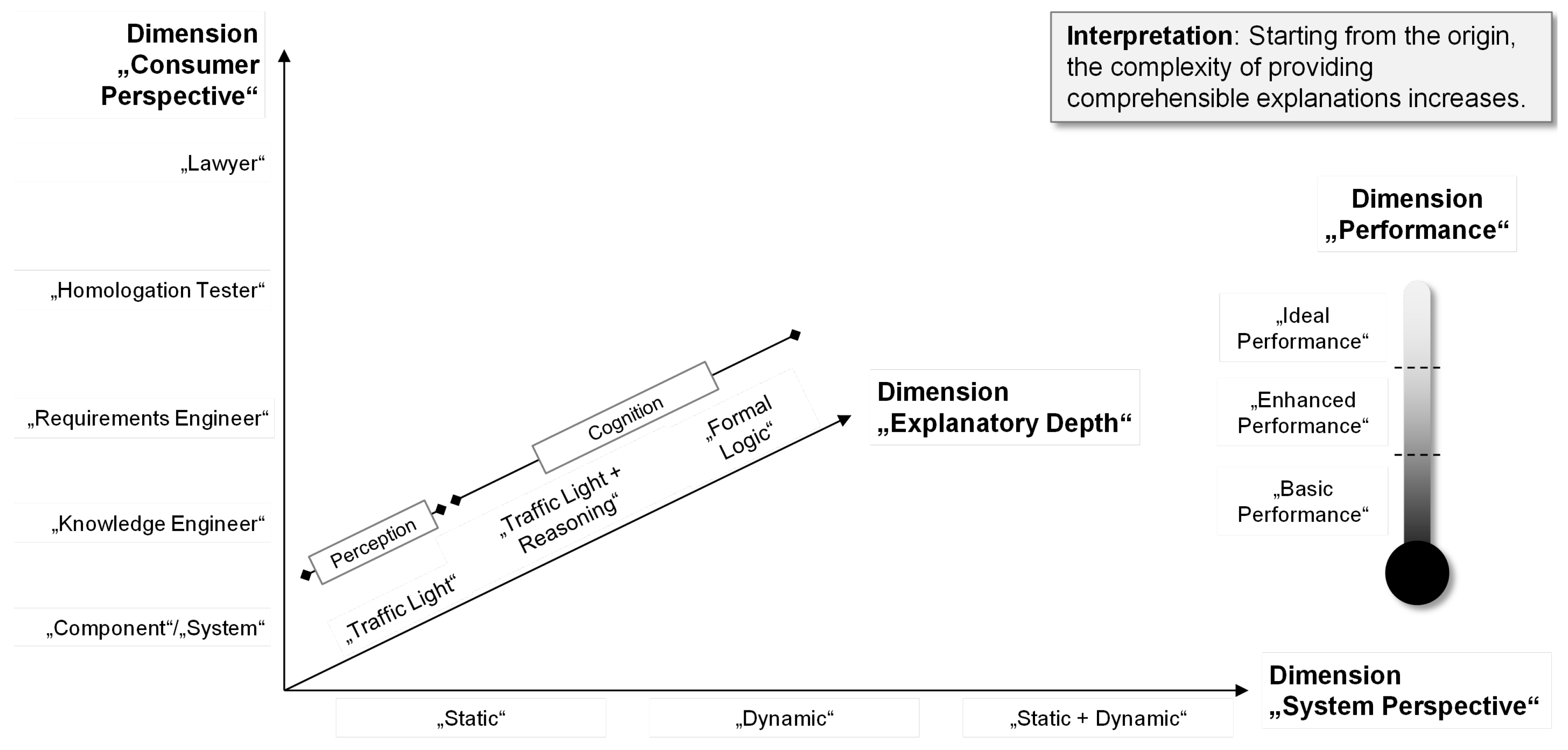

The first dimension of the framework is the consumer perspective, which describes information needs of users interacting with the system. If an error occurs in the automated processing of a development document, users require different types of explanations to understand the problem and take appropriate action. While a system or a component requires an output from the system that is machine-readable, a knowledge engineer is skilled enough to work with all levels of explanation. Furthermore, a requirements engineer needs explanations in the context of requirements management. A homologation tester needs explanations in form of format-specific justifications. Finally, lawyers need justifications that are legally usable in court.

The second dimension is the system perspective and refers to the topology of a complex AI system or process executed by it, thus to the AI-supported process steps. Some explanations refer only to the static structure of the elements of the AI system in use. Others require analysis of the interdependencies between individual system elements referring to the dynamic case. The most complex case is a mixture of the static and dynamic structure, where an interaction of elements and their related interdependencies is relevant.

The third dimension is the depth of explanation. While a visual summary of the results is often sufficient when simply comparing documents, more in-depth explanations are often necessary for security-related topics. The simplest case is pure perception. For example, a simple traffic light can indicate that processes have been completed successfully or that errors have occurred. The complexity increases in the area of cognition. An example would be the enrichment of a traffic light with additional outputs and reasoning that describe the events in the executed process in more detail. The third and most complex case requires formal logic. In this case, the traffic light status is explained by additional information.

The fourth dimension is the performance dimension. For some background applications, a basic performance that takes days to calculate is acceptable. In other cases, the answer is needed in a faster time frame of hours or minutes in an enhanced performance. Optimal performance creates responses in the matter of seconds and enables real-time interaction.

As the individual dimensions are located further away from the origin, the complexity of information processing also increases. The orientation framework with the four dimensions is shown in

Figure 4.

In addition to the conceptual capabilities that consider the requirements of the end users, the system to be developed must have various formal capabilities. These include a certain degree of robustness. Robustness describes the ability of a system or algorithm to deal with errors in execution, missing values, faulty data, and unknown information. It also ensures that AI-based systems do not take unnecessary risks and cannot be easily misused during their lifecycle [

20]. Furthermore, a telemetry capability that provides identifiers for different pre- and post-execution contexts should be provided. For this purpose, a universally applicable key performance indicator system must be developed. In addition, end-to-end declarations must be available so that the context can be fully integrated throughout the configured system at all times.

5. Related Work

To address the identified capabilities, solution elements can be drawn from various existing approaches to be combined and expanded as needed. The following section describes a selection of the most important application-oriented approaches and summarizes them to form a basis for deriving specific requirements.

Confalonieri [

23] discuss the role of ontologies in explainable AI from three perspectives: reference modeling, everyday knowledge and knowledge refinement with special regard to complexity management. Ontologies provide formal models that are essential for designing explainable systems and generating explanations by promoting interoperability and reusability across different domains. They enable explanations to be created with linked semantics that can be refined through logical reasoning.

Tsakalakis [

24] developed a nine-dimensional typology of explanations to support an explainability-by-design strategy. It introduces the role of a “legal engineer” who acts as an interface between compliance and engineering teams and aligns the structured collection of explanation-related requirements. The typology enables the derivation of computationally processable explanation elements that can be translated into system requirements in the technical design process.

Golpayegani [

25] present an ontology named AIRO for the formal, machine-readable, and interoperable representation of risks associated with AI systems, based on the EU AI Act and the ISO 31000 family of standards. It particularly supports the identification of high-risk AI systems and the generation of technical documentation through semantic web technologies such as SPARQL and SHACL. In addition, AIRO enables automated management, temporal tracking, and analysis of risk information, which supports organizations in complying with regulatory requirements and implementing monitoring systems in accordance with regulations.

Chari [

26] developed an ontology for explanations that helps system designers integrate different types of explanations into AI-supported systems. The ontology extends existing explanation patterns and uses the SIO ontology to define the necessary classes and properties for generating user-centered explanations. It was developed through extensive literature research and requirements from clinical practice and is flexible and extensible to address future needs. The ontology supports system designers in selecting appropriate explanation types and will serve as the basis for a middleware framework that generates personalized explanations based on user input and context.

Allemang [

27] present an approach to improve the accuracy of LLM-supported question-answering systems by using ontologies. Ontology-based query checking is used to verify the semantic correctness of SPARQL queries and identify errors. The LLM is then triggered with the explanations of the errors to correct the queries. This cycle is repeated until the query is correct or an upper limit of cycles is reached.

An analysis of related work shows that systematic interlinking of information has the potential to provide complex explanations in line with demand. Existing ontologies can be used as a basis and expanded with the context of application-specific knowledge to manage complexity. It should provide formal models that promote interoperability and reusability while enabling understandable explanations. In summary, it can be stated that the capabilities developed in

Section 4 can be well fulfilled by an ontology.

6. Requirements Elicitation

The capabilities and insights from

Section 4 and

Section 5 serve as a basis for addressing the needs for explanation arising from the challenges and influences from

Section 2 and

Section 3, following the method from [

28]. The key question of explainability "Why was a given result generated?" (ISO/IEC 22989 [

29], 3.5.7) is broken down into requirements categories for the design of explanations of complex AI systems as ontological concepts and data objects. For each of the dimensions described in

Section 4 respective requirements are derived and justified in

Table 1.

System Perspective: These requirements relate to the basic information to be represented for retracing the inner workings of a complex AI system and thus to the information to be conveyed by an explanation. Hence, the subject of interest is an AI system or AI method, respectively.

Consumer Perspective: These requirements relate to the consumer of generated explanations. Hence, these are the subject of interest.

Depth of Explanation: These requirements address the amount of information presented to the recipient of an explanation. Hence, the subject of interest is the information content of an explanation.

Performance: These requirements address the guidance of consumer expectations towards the provision of explanations. Thus, the subject of interest is the classification of an explanation.

7. Conclusion and Outlook

In this paper, basic requirements for explanations of complex AI systems, i.e., compound systems with at least one AI method involved, have been addressed. The motivation for this comes from RE in the automotive industry, where the insertion of AI, along with its increasing regulatory constraints, into the system development process of products, i.e., vehicles, meets leading regulatory constraints from homologation. To narrow down the roles, influences, and effects of the involved AI systems on requirements management, an orientation framework with four perspectives on capabilities for the provision of explanations has been presented, and explanation-related requirements have been derived. Although originating in a specific domain, the approaches shall be generalizable and applicable to any domain and kind of AI system.

Next steps include the design and implementation of a suitable telemetry approach in support, evaluation, and validation of the presented requirements, together with a suitable key performance indicator system to address the needs of different recipients of explanations. Ultimately, the goal is to enable the automated derivation of end-to-end chains of explanations for AI-based data processing activities and flows. This is considered a cornerstone for the trustworthiness of such complex AI systems.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the KIMBA project, funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action.

References

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Regulation - EU - 2024/1689: Artificial Intelligence Act, 2024.

- Spoletini, P.; Ferrari, A. The Return of Formal Requirements Engineering in the Era of Large Language Models. In Requirements Engineering: Foundation for Software Quality; Mendez, D., Moreira, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; Vol. 14588, pp. 344–353. [Google Scholar]

- Laplante, P.A.; Kassab, M.H. Requirements Engineering for Software and Systems, 4 ed.; Auerbach Publications: New York, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt, F.; Holder, D.; Maier, T. The Vehicle Development Process Where Engineering Meets Industrial Design. IEEE Engineering Management Review 2023, 51, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC. ISO/IEC 33000 Information Technology - Process Assessment.

- VDA. Automotive SPICE® – VDA QMC. Technical report, 2023.

- UNECE regulations - European Commission.

- Faustmann, C.; Kranabitl, P.; Bajzek, M.; Fritz, J.; Hick, H.; Sorger, H. Future of Systems Engineering. In Systems Engineering for Automotive Powertrain Development; Springer, 2021; pp. 855–882.

- Antinyan, V. Revealing the complexity of automotive software. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, Virtual Event USA, 2020; pp. 1525–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum, S.K.; Wolff, C.; Toledo, N. Adapting Agile Principles for Requirements Engineering in Automotive Software Development. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE European Technology and Engineering Management Summit (E-TEMS), 2022, pp. 166–174.

- Christophe, F.; Mokammel, F.; Coatanéa, E.; Nguyen, A.; Bakhouya, M.; Bernard, A. A methodology supporting syntactic, lexical and semantic clarification of requirements in systems engineering. International Journal of Product Development 2014, 19, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, A.; Sánchez, L.E.; Antonelli, L. Building an integrated requirements engineering process based on Intelligent Systems and Semantic Reasoning on the basis of a systematic analysis of existing proposals. JUCS - Journal of Universal Computer Science 2022, 28, 1136–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, F.S.; Reis, P.A.; Cavalcante, M.S.; Oliveira, A.H.M.d. Systems Engineering Process Enhancement: Requirements Verification Methodology using Natural Language Processing (NLP) for Automotive Industry. SAE Technical Paper 2023-36-0117, SAE International, Warrendale, PA, 2024.

- Sonbol, R.; Rebdawi, G.; Ghneim, N. The Use of NLP-Based Text Representation Techniques to Support Requirement Engineering Tasks: A Systematic Mapping Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 62811–62830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeld, T.; Bertram, V.; Dehn, S.; Slawik, V.; Fleischer, D.; Chander, J.; Müller, A.W.; Kostov, N.; Schmitz, J.N. Mehr Effizienz und Qualität im Requirements Engineering mit KI - Potenziale, Implementierung, Chancen und Risiken am Beispiel Forschungsprojekt KIZAM. In Proceedings of the Tagungsband Embedded Software Engineering Kongress 2023, Sindelfingen, 2023.

- Korten, M.; Hötter, M. Use of Artificial Intelligence in Requirements Management. ATZ worldwide 2024, 126, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thipse, Y. LEAN Techniques for Effective, Efficient and Secure Information Processing in Automotive Homologation. SAE Technical Paper 2019-26-0335, SAE International, Warrendale, PA, 2019.

- DIN/DKE. Artificial Intelligence Standardization Roadmap, 2nd edition, 2022.

- Chander, B.; John, C.; Warrier, L.; Gopalakrishnan, K. Toward Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (TAI) in the Context of Explainability and Robustness. ACM Computing Surveys 2025, 57, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöldy, M.; Szalay, Z.; Tihanyi, V. Challenges in homologation process of vehicles with artificial intelligence. Transport 2020, 35, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasothy, A.; Laugel, T.; Lesot, M.J.; Marsala, C.; Detyniecki, M. A general framework for personalising post hoc explanations through user knowledge integration. International Journal of Approximate Reasoning 2023, 160, 108944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umm-E-Habiba. Requirements Engineering for Explainable AI. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 31st International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE), Hannover, Germany, 2023; pp. 376–380.

- Confalonieri, R.; Guizzardi, G. On the Multiple Roles of Ontologies in Explainable AI, 2023. arXiv:2311.04778.

- Tsakalakis, N.; Stalla-Bourdillon, S.; Huynh, D.; Moreau, L. A typology of explanations to support Explainability-by-Design. ACM Journal on Responsible Computing 2025, 2, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpayegani, D.; Pandit, H.J.; Lewis, D. AIRO: An Ontology for Representing AI Risks Based on the Proposed EU AI Act and ISO Risk Management Standards. In Studies on the Semantic Web; Dimou, A.; Neumaier, S.; Pellegrini, T.; Vahdati, S., Eds.; IOS Press, 2022.

- Chari, S.; Seneviratne, O.; Ghalwash, M.; Shirai, S.; Gruen, D.M.; Meyer, P.; Chakraborty, P.; McGuinness, D.L. Explanation Ontology: A general-purpose, semantic representation for supporting user-centered explanations. Semantic Web 2024, 15, 959–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemang, D.; Sequeda, J. Increasing the LLM Accuracy for Question Answering: Ontologies to the Rescue!, 2024. arXiv:2405.11706 [cs].

- Hildebrandt, C.; Köcher, A.; Küstner, C.; Lopez-Enriquez, C.M.; Müller, A.W.; Caesar, B.; Gundlach, C.S.; Fay, A. Ontology Building for Cyber-Physical Systems: Application in the Manufacturing Domain. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 22989:2022(en), Information technology — Artificial intelligence — Artificial intelligence concepts and terminology.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).