1. Introduction

Agriculture is widely regarded as one of the most critical sectors, playing a pivotal role in ensuring food security. However, as the global population continues to expand, so does the demand for food, thereby creating the need to transition from conventional farming methods to smart farming practices, also known as Agriculture 4.0 [

1]. Agricultural monitoring and harvesting tasks play a critical role in modern precision agriculture to ensure optimal crop yield and quality. Key tasks such as crop maturity detection, disease or pest detection, and growth stage monitoring use advanced technologies such as computer vision, remote sensing, and machine learning (ML). Ripeness detection helps farmers determine the optimal time to harvest by analyzing the color, texture, and chemical properties of fruits and crops. Disease and pest detection uses image processing and AI models to detect early signs of plant diseases, enabling timely intervention and reducing crop losses. Growth stage monitoring tracks plant development using satellite imagery, drones, or IoT sensors, providing valuable insights into nutrient requirements and overall health. These automated techniques increase efficiency, reduce manual labor, and support sustainable agricultural practices.

Deep learning (DL), a subset of artificial intelligence (AI), has emerged as a powerful tool for image analysis and pattern recognition. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), a prevalent deep learning (DL) architecture, have exhibited substantial success in a variety of image classification tasks, including object detection, fruit counting, automated harvesting, and, notably, plant disease detection and diagnosis. In the realm of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are frequently the preferred option for image detection and classification tasks. This preference can be attributed to the inherent capability of CNNs to autonomously extract relevant image features and to understand spatial hierarchies [

2,

3].

Two categories of object detection algorithms are distinguished: two-stage algorithms and one-stage algorithms. Two-stage algorithms, including ResNet, LeNet-5, AlexNet, GoogLeNet, and Faster R-CNN, delineate a two-step process. Conversely, one-stage algorithms, such as SSD, VGG, and YOLO, execute a single step. It has been demonstrated that two-step algorithms demonstrate relatively high accuracy. However, these algorithms are constrained by computational demands and real-time performance [

3,

4]. The advent of YOLO signified a substantial progression in the domain of object recognition, thereby fundamentally altering the methodologies employed in recognition tasks. The primary innovation of YOLO is the conceptualization of the object detection task as a single regression problem. In the solution approach, the prediction of bounding boxes and class probabilities occurs in a unified process [

5].

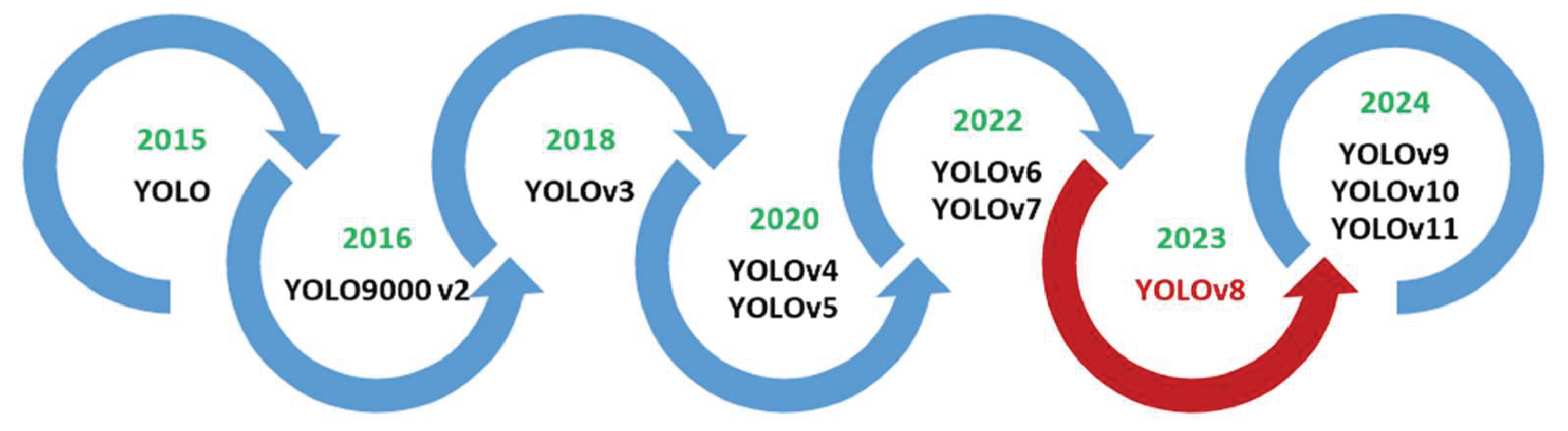

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the YOLO family.

Despite significant advances in object (weed, flower, crop, maturity, disease or pest) detection technology for plant/crop monitoring, diagnostics and harvesting, several formidable challenges remain to be overcome to realize its full potential. A significant challenge in this field pertains to occlusion, wherein objects become partially hidden or obscured, thereby complicating their accurate detection. Another challenge is the management of object scales, wherein objects manifest at varying stages or sizes due to alterations in type (leaf, flower, crop), shape, color, perspective, or distance, thereby impeding the processes of detection or classification. The need for real-time processing adds another layer of complexity, especially in real-world field environments that are diverse and unstructured, where lighting conditions, backgrounds, and object types can vary widely [

5].

The big popularity and widespread application of YOLOv8 to a large number of fields have led to many advancements of its architecture and algorithms. A considerable number of researchers have continued to refine and extend the YOLOv8 framework, applying it to various tasks, including plant identification, disease detection and classification, and crop detection and maturity monitoring studies. These efforts have sought to attain consistent and reliable results in diverse and unstructured environments with varying lighting conditions, backgrounds, object types, scales, and growth stages. We identified over 200 enhanced versions of YOLOv8, though our analysis is constrained to case studies in the domain of agricultural object detection. However, a systematic review of these advancements is conspicuously absent from the extant literature. The majority of reviews offer a more expansive perspective on the evolution of YOLO, encompassing a range of primary versions and offering comparative analyses; for instance, YOLOv5–YOLOv10 in [

6] and YOLOv8–YOLOv11 in [

7]. Other surveys, such as those in [

8,

9], concern the macro framework of DL-based object detection.

A notable exception is the work in [

10], which approaches the subject in a somewhat analogous manner to our paper. However, the scope of Badgujar et al.’s work is considerably more limited, encompassing only a concise overview of the YOLO model development and modification.

The present work aims to provide a comprehensive, detailed, and systematic overview of Improved YOLOv8 algorithms published in the last two and a half years, since the appearance of YOLOv8, focusing particularly on agricultural monitoring and harvesting tasks. This overview is presented in the form of tables, figures, and statistical analysis (pie diagrams). This paper can serve as a starting point for researchers and engineers seeking to expand their knowledge in this field, apply the reviewed algorithms, or develop further enhanced approaches. The main contributions of our work can be summarized as follows:

We present the first systematic review of its kind in this area, analyzing 196 selected research papers on the topic.

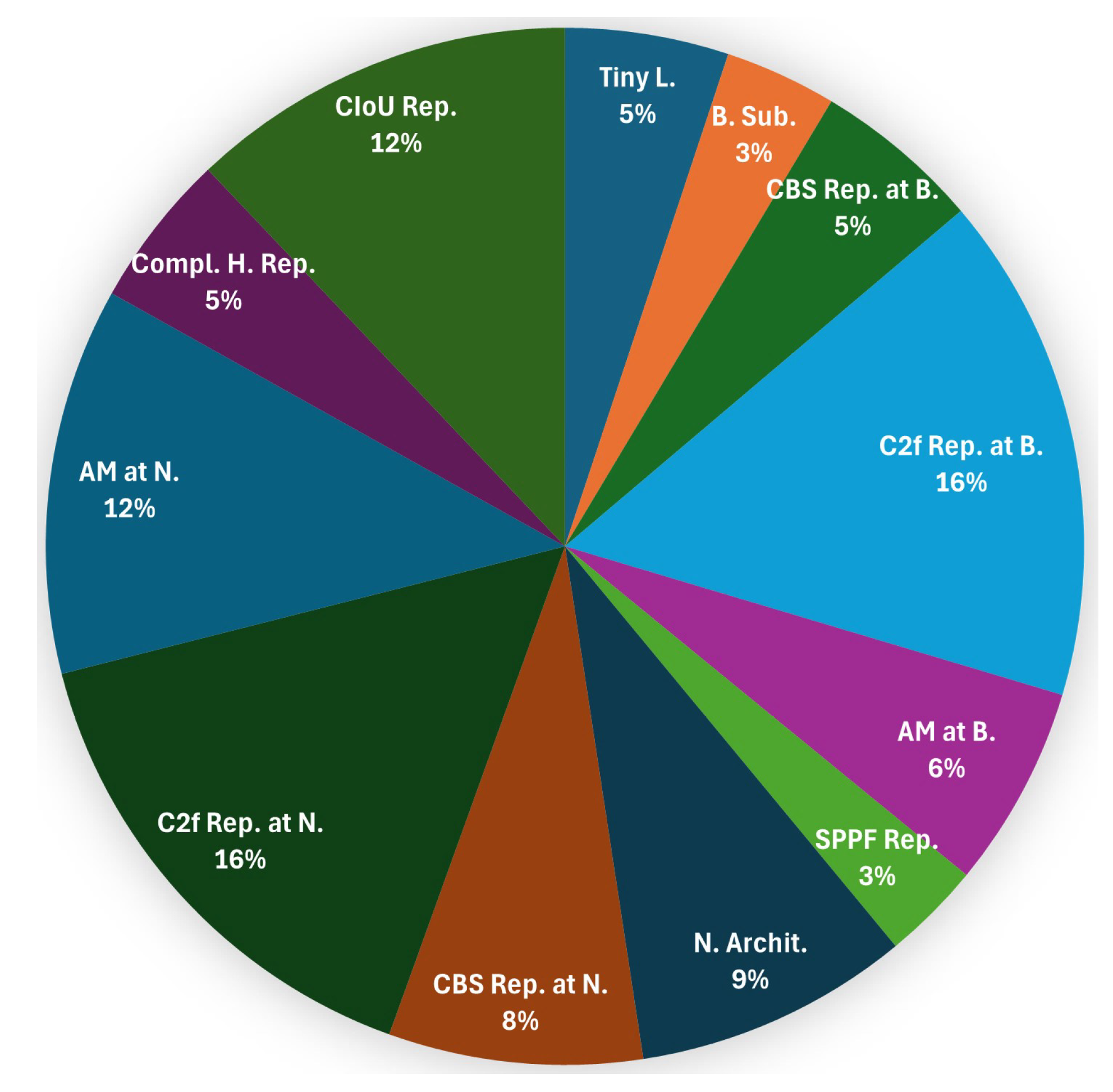

We assign the improvement measures, modifications, or extensions to the individual sections of YOLOv8 (

Figure 2) (backbone, neck, head) and components (CBS, C2f, AM—Attention Mechanism, SPPF, Concat, Upsample, CIoU).

We provide recommendations and highlight potential improvements for each component of YOLOv8 that could be replaced or enhanced.

We recommend the most promising improvements and extensions of YOLOv8 for further development and application of specific detection methods, and outline future research directions in the field.

The present review focuses exclusively on the further development and improvement/modification of the YOLOv8 model. This paper does not cover topics like data acquisition, data processing, or YOLO integration with other algorithms for specific applications.

Figure 2.

YOLOv8 network architecture (based on [

11,

12]). Legend: CBS–Convolution + Batch Normalisation + Sigmoid-weighted Linear Unit (SiLU); C2f—CSP (Cross Stage Partial) bottleneck with 2 convolutions, Fast version; SPPF—Spatial Pyramid Pooling, Fast version; Upsample—upsampling; w—Width multiple; r—Ratio; Concat—Concatenation operation; Detect: Detector; FPN—Feature Pyramid Network; PAN—Path Aggregation Network; Conv2d–2D Convolution; BBox Loss—Bounding Box Loss, IoU—Intersection over Union, CIoU–Complete IoU; DFL—Distributed Focal Loss; Cls Loss—Classification Loss, BCE—Binary Cross Entropy

Figure 2.

YOLOv8 network architecture (based on [

11,

12]). Legend: CBS–Convolution + Batch Normalisation + Sigmoid-weighted Linear Unit (SiLU); C2f—CSP (Cross Stage Partial) bottleneck with 2 convolutions, Fast version; SPPF—Spatial Pyramid Pooling, Fast version; Upsample—upsampling; w—Width multiple; r—Ratio; Concat—Concatenation operation; Detect: Detector; FPN—Feature Pyramid Network; PAN—Path Aggregation Network; Conv2d–2D Convolution; BBox Loss—Bounding Box Loss, IoU—Intersection over Union, CIoU–Complete IoU; DFL—Distributed Focal Loss; Cls Loss—Classification Loss, BCE—Binary Cross Entropy

2. Materials and Methods

This review was (partly) conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews [

13].

2.1. Review Question

The research question guiding this review is as follows: Which module substitutions or extensions in the YOLOv8 architecture are revealed by the literature to improve detection performance in agricultural monitoring and harvesting tasks? What are the best module combinations for improving performance? What open issues warrant further investigation?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

We considered research articles, conference papers, and arXiv papers that explicitly propose and investigate Improved YOLOv8 architectures, with case studies related to agricultural monitoring and harvesting tasks. Only works published in peer-reviewed journals or presented at reputable conferences were included. Additionally, the studies had to clearly describe their methodologies and applications and include an ablation study. They had to focus on at least one of the following five categories:

Detection of plant diseases and pests.

Detection of fruits/crops, their maturity, or picking points for harvesting.

Detection of plant growth stages.

Weed detection.

Plant phenotyping.

The timeline for inclusion spanned publications from January 2023, the year YOLOv8 was released, to October 2025. This reflects YOLOv8’s rapid evolution in recent years.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they were not directly related to one of the considered application fields. General discussions on AI and ML/DL, theoretical and basic works without practical implications, and duplicate publications were omitted. Additionally, non-peer-reviewed content, such as blog posts and opinion articles, as well as works lacking sufficient details on methodology, metric-based evaluations, and an ablation study, were excluded. Papers written in languages other than English were excluded.

2.4. Search Strategy

A simple search strategy was employed to identify relevant literature. Using a combination of keywords and Boolean operators (“AND”, “OR”), we searched multiple academic databases, including Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect. The keywords used were “Improved YOLOv8,” “Disease/Pest Detection,” “Pest Detection,” “Fruit/Crop Detection,” and “Maturity/Picking Point Detection,” among others. We manually screened the reference lists of the included studies to identify additional relevant works and did not use tools such as Mendeley for deduplication and systematic screening.

2.5. Data Extraction and Data Synthesis

We used a thematic synthesis approach to organize the data into predefined YOLOv8 module categories (CBS, C2f, AM, SPPF, Concat, Upsample, and CIoU) and sections (Backbone, Neck, and Head), which are aligned with the study’s focus areas, as defined in

Section 2.2. The synthesis aimed to identify potential module combinations that lead to performance improvement or lightweighting. The visual representation in

Table A1 was generated to summarize the findings and facilitate comparative analysis across studies.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Sources

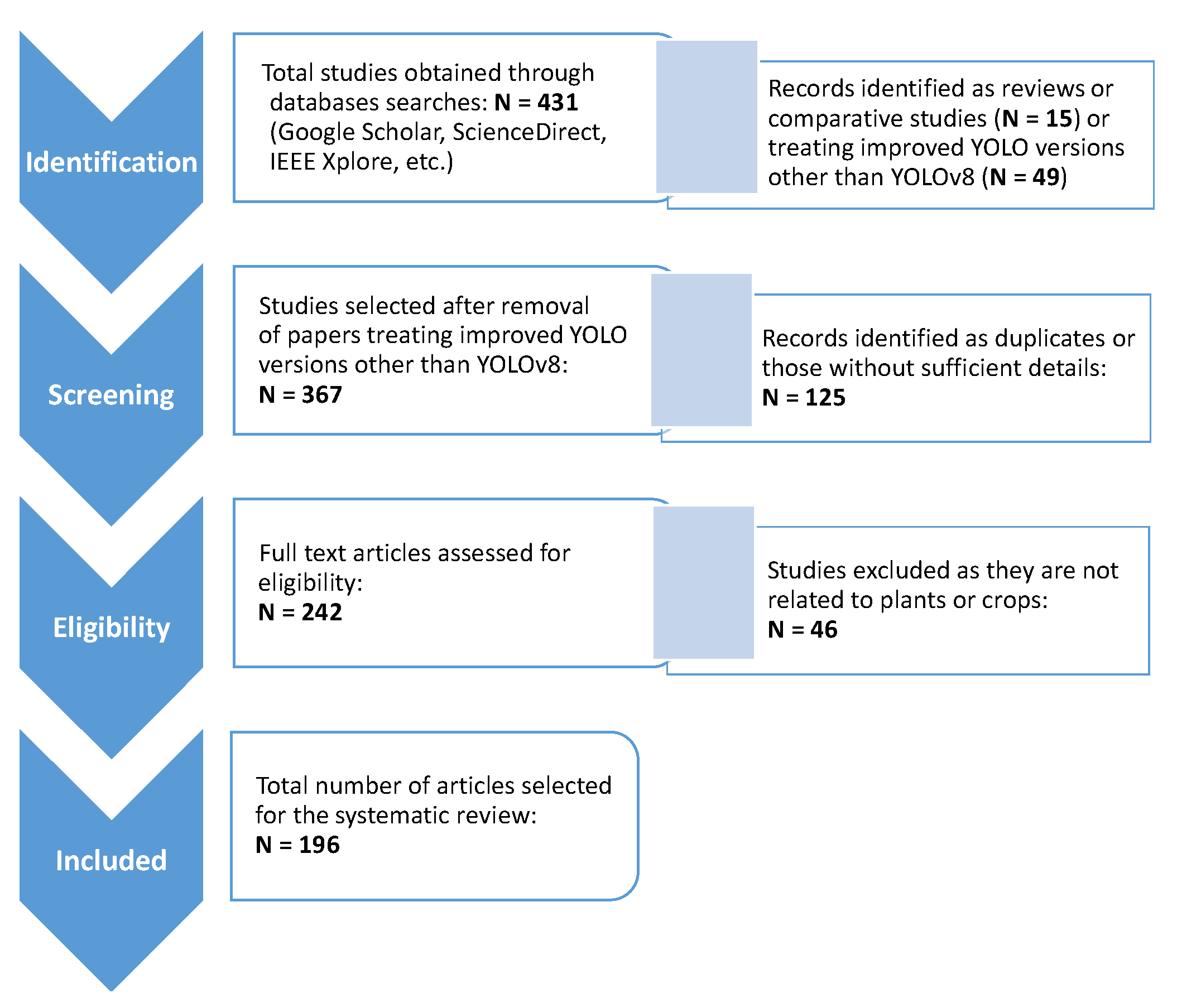

Our review involved analyzing the titles and abstracts of studies to identify matches with the searched keywords. A total of 431 records were initially identified based on these keywords. After eliminating duplicates and excluding overview articles or articles with unrelated content, the remaining full-text studies were selected, screened, and evaluated for inclusion in the systematic review. The flow chart of PRISMA method is shown in

Figure 3. After the first and second rounds of evaluation, we excluded those deemed irrelevant to the topic, non-English papers, and papers without sufficient details, selecting 196 articles for our survey.

3.2. Synthesis of Results

The papers included in our review are listed in

Table A1, summarizing the replacements or extensions introduced in the Improved YOLOv8 algorithms compared to the baseline YOLOv8. The improvement measures will be presented and discussed in

Sections 4–sec:Head Improvements. The included studies are cotogerized to diverse agricultural monitoring and harvesting tasks, including detection of plant diseases and pests (

Table 1), detection of fruit/crop maturity, pose, or picking point for harvesting (

Table 2), detection of plant growth stages (

Table 3), weed detection (

Table 4), and plant phenotyping (

Table 5).

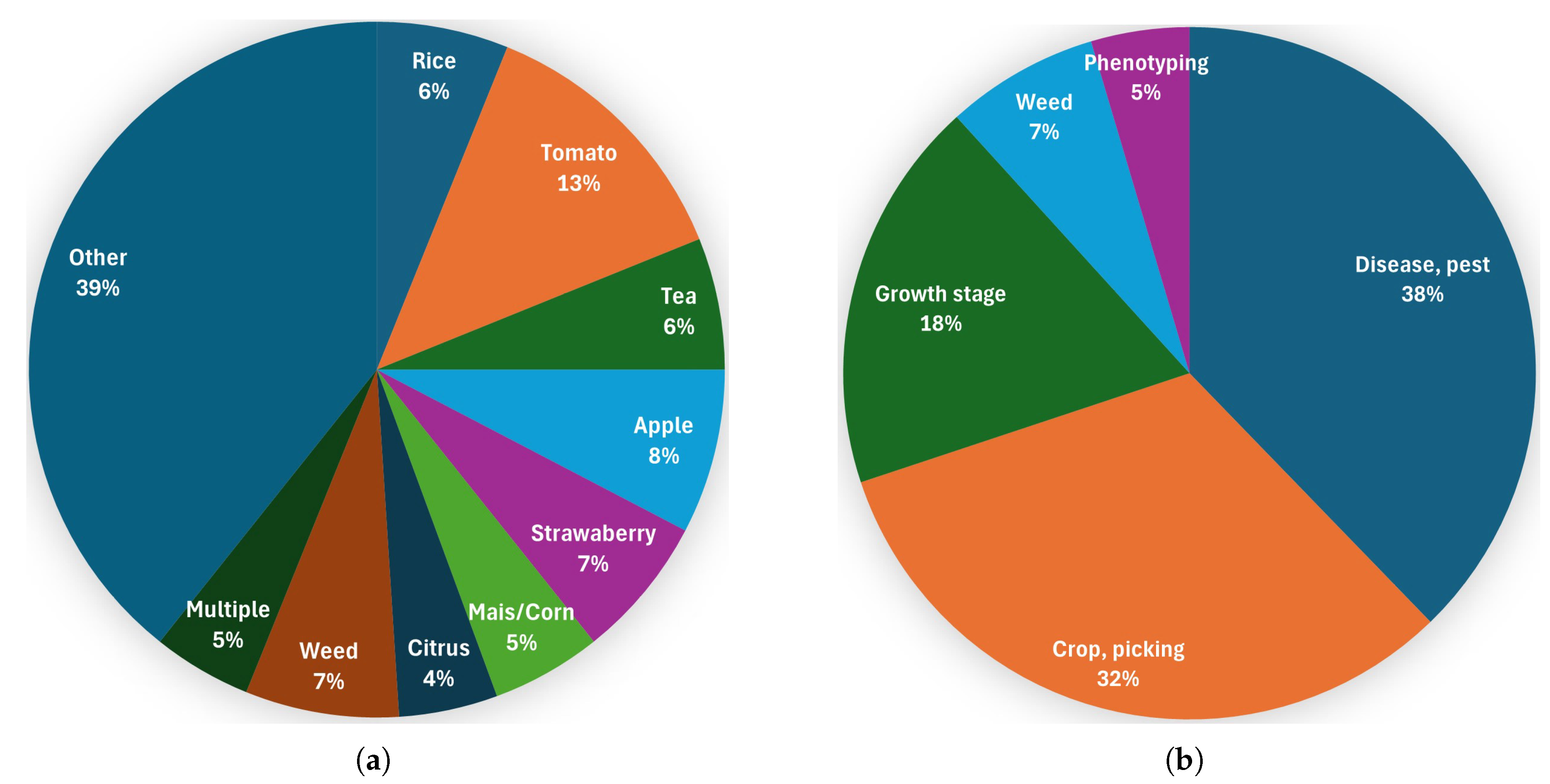

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the reviewed studies across agricultural monitoring and harvesting task categories. As can be seen, the most Improved YOLOv8 versions (38%) are related to disease and pest detection, which confirms its high relevance in agricultural object detection. The application of YOLOv8 variants for real-time identification of crops, picking points, and ripeness with efficiency and precision is similarly important, as demonstrated in 32% of the investigated papers. Next, accurately detecting crop growth stages is important for agricultural monitoring. This information, which was addressed in 18% of the reviewed studies, is essential for planning crops, predicting yields, and reducing fertilizer and workforce consumption. Lastly, weed detection is a traditional application field of computer vision and, thus, of YOLOv8.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the reviewed studies (a) by plant type; (b) by categories of agricultural monitoring and harvesting tasks.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the reviewed studies (a) by plant type; (b) by categories of agricultural monitoring and harvesting tasks.

Figure 5.

Frequency of replacement or extension of the respective YOLOv8 module or section in the reviewed studies (

Table A1). Legend: Tiny L.—Addition of a Tiny object detection Layer at P2, B. Sub.—Substitution of the complete Backbone, CBS Rep. at B.—CBS Replacement at the Backbone, C2f Rep. at B.—C2f Replacement at the Backbone, AM at B.—Addition of an AM in the Backbone, SPPF Rep.—Replacement of the SPPF module, N. Archit.—Change of the Neck Architecture, CBS Rep. at N.—CBS Replacement at the Neck, C2f Rep. at N.—C2f Replacement at the Neck, AM at N.—Addition of an AM in the Neck, Compl. H. Rep.—Replacement of the complete Head, CIoU Rep.—Replacement of the CIoU loss function.

Figure 5.

Frequency of replacement or extension of the respective YOLOv8 module or section in the reviewed studies (

Table A1). Legend: Tiny L.—Addition of a Tiny object detection Layer at P2, B. Sub.—Substitution of the complete Backbone, CBS Rep. at B.—CBS Replacement at the Backbone, C2f Rep. at B.—C2f Replacement at the Backbone, AM at B.—Addition of an AM in the Backbone, SPPF Rep.—Replacement of the SPPF module, N. Archit.—Change of the Neck Architecture, CBS Rep. at N.—CBS Replacement at the Neck, C2f Rep. at N.—C2f Replacement at the Neck, AM at N.—Addition of an AM in the Neck, Compl. H. Rep.—Replacement of the complete Head, CIoU Rep.—Replacement of the CIoU loss function.

3.3. Improved YOLOv8 Taxonomy of this Paper

The YOLOv8 network structure (

Figure 2) consists of three main sections: backbone, neck, and head. Accordingly, the improvement actions introduced relate to each of these sections. We have therefore analyzed the improvements and grouped them into the main categories in addition to pyramid modifications. Our Improved YOLOv8 Taxonomy presented in the paper is shown in

Figure 6. In each category, there are corresponding component replacements or additions.

In the following subsections, we provide our overview and highlight the results of selected methods and/or comparative experiments on introduced improvement or extension measures in the reviewed literature. The presentations and discussions are based on the comprehensive overview of YOLOv8’s modules given in

Table A1. It is important to note that we accept the performance indicator values as stated in the papers without checking or reproducing them because doing so is not possible or would exceed the scope of this paper.

4. Pyramid Structure Modifications

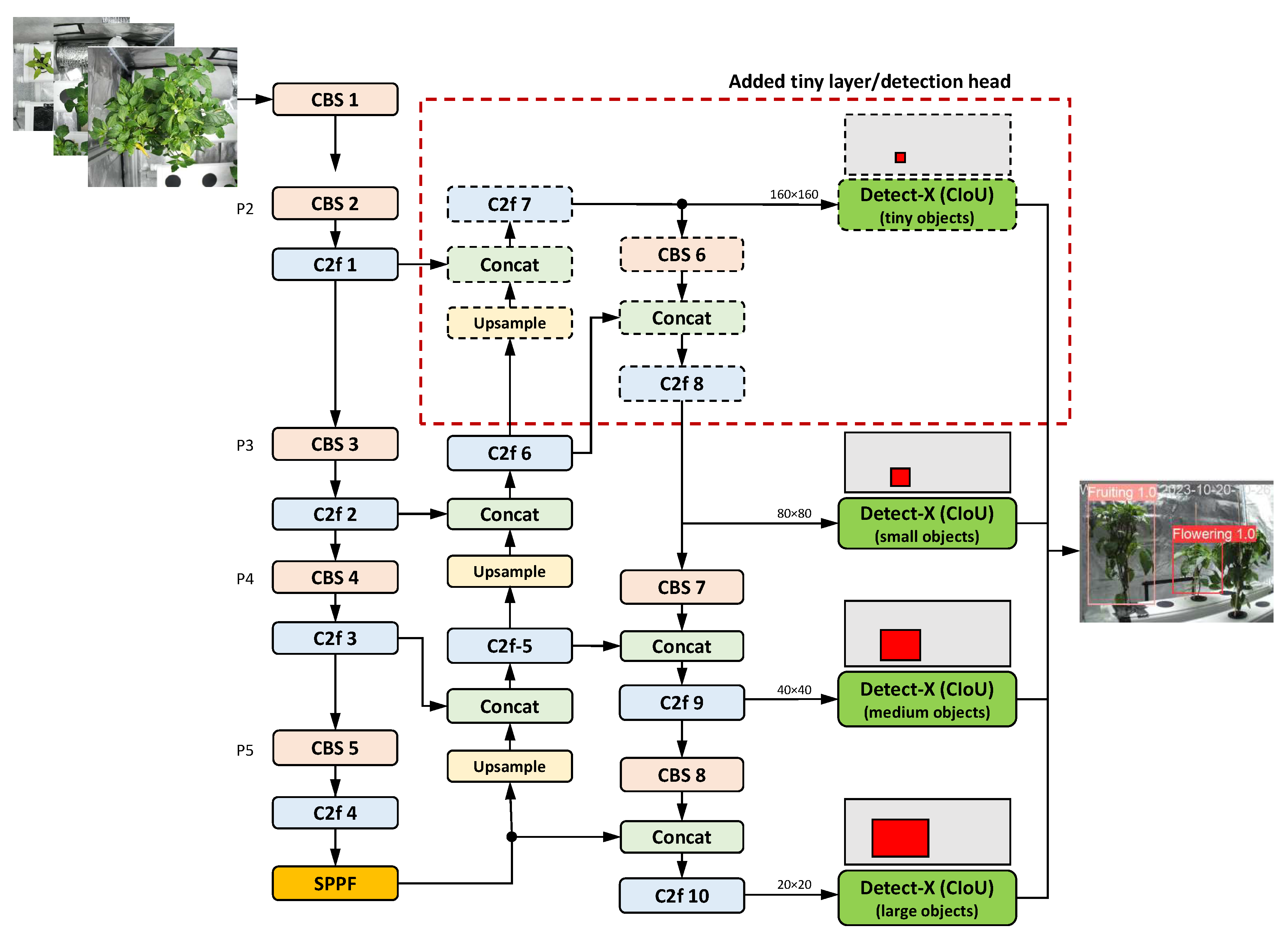

Some improved versions of YOLOv8 extended the original feature pyramid structure at the 160×160 scale (P2), working with an additional detection head to improve performance, as proposed by many researchers, e.g., in [

15,

80,

157]; see

Figure 7. An additional layer addresses the challenges associated with detecting small objects and the depletion of semantic knowledge due to varying scales [

80]. The corresponding detection head uses high-resolution feature maps to accurately predict the location of small targets. This solves the problem of losing information about small targets during feature transfer. [

15]. On the other hand, other researchers have suggested simplifying the complex structure of the standard YOLOv8 model to reduce the number of parameters. For instance, Fang and Yang [

177] eliminated the large target detection modules and decreased the number of detection heads from three to two.

The addition of the fourth detection head is expected to have a large impact on the overall accuracy improvement. Yao et al. [

66] demonstrated in their wheat disease detection case study that the addition of a small object detection layer resulted in a 3.38% increase in mAP and a 5.35 decrease in FPS. A remarkable 8.2% increase in mAP for small object detection was achieved in the work of Yue et al. [

79] on the detection of crop pests and diseases. Adding a tiny object layer increased mAP by 9.0% and 6.3% for two different prediction models: YOLOv8n-day for daytime and YOLOv8n-night for nighttime in the Zhang et al. [

172] study on raspberry and stalk detection. Improvements of 4% in mAP were achieved by introducing specialized small target detection in [

23].

5. Backbone Improvements

The design of the backbone network structure is intended to efficiently extract multiscale feature information.

5.1. Backbone Substitutions

The complete substitution of the backbone network (except for the SPPF module) represents another structural improvement in the YOLOv8 algorithm. The use of EfficientViT as the backbone network was proposed in [

91,

189]. Other researchers replaced the backbone by StarNet [

201] or RepViT [

189]. Improved YOLOv8 networks, in which the backbone network has been replaced with either the Swin Transformer (SwinT) or the Deformable Attention Transformer (DAT), were presented in [

152] and [

83], respectively. Wang et al. [

20] replaced the backbone with MobileNetV4, a new generation lightweight detection network introduced in April 2024. Other backbone replacements and transformer inclusions can be found in

Table A1.

In [

160], the performance of four different backbone networks (ShuffleNetV2, GhostNetV2, EfficientViT2, MobileNetV3) was compared with that of the C2f-Faster backbone proposed by Zhang et al. while keeping all other parameters constant. It was shown that the C2f-Faster improvement method and MobileNetV3 provided significant advantages in precision, recall, and average precision compared to the other networks. Wang et al. [

37] provided comparative experiments to investigate the impact of different backbone networks on the performance of the YOLOv8 model for tea leaf disease detection. The backbone networks included the original YOLOv8 backbone, ResNeXt, MobileNetV2, ShuffleNetV2, EfficientNetV2, and RepVGG. The efficacy of replacing the original backbone with lightweight networks such as MobileNetV2, ShuffleNetV2, or EfficientNet was demonstrated, leading to an increase in detection speed, albeit at the expense of detection accuracy. In contrast, using the RepVGG backbone significantly reduced the number of parameters, floating-point operations, and memory consumption while maintaining good detection performance (mAP: +2.43%) [

37]. The experimental results in [

183] showed that replacing the backbone with an Mblock-based architecture derived from the MobileNetV3 feature extraction module led to a 3.0% improvement in mAP50 over the baseline YOLOv8 model.

Replacing the backbone network with ConvNeXtV2, as proposed by Chen et al. [

103], increased mAP by 2.09%. This significant improvement indicates that ConvNeXtV2 better captures image features and improves model performance compared to the original YOLOv8 structure.

In their study of weed detection in cotton fields, Zheng et al. [

200] restructured the YOLOv8 backbone network and studied ten

lightweight networks that have been widely used in recent years, including ConvNext, EfficientNet, FasterNet, MobileNeXtV3, MobileNetV3, PP-LCNet, ShuffleNetV2, VanillaNet, GhostNet, GhostNetV2, and StarNet. They found out that their improved algorithm using StarNet significantly outperforms other lightweight networks in terms of mAP (98.0%). Furthermore, a comparative analysis revealed that the performance of all other networks exhibited a range of degrees of deterioration relative to the baseline model. These results suggest that, while lightweight models can effectively reduce the number of parameters and computational requirements, excessive lightweighting may reduce the feature extraction capabilities, resulting in the loss of semantic information and consequently degraded recognition accuracy [

200]. For example, VanillaNet achieved the best results in terms of lightweighting, but it had the lowest detection performance, with an mAP of only 89.0%, which means a decrease of 8.9% in mAP.

5.2. Inclusion of Transformer Networks

In addition to replacing the entire backbone network with a Vision Transformer Network (see

Table A1), certain Transformer modules can be incorporated into the backbone in place of CBS, C2f or SPPF, or to bridge the gap between the backbone and the neck. In the Improved YOLOv8s network proposed by Diao et al. [

152] for maize row segment detection, the backbone network was replaced with a SwinT network, resulting in a 4.03% improvement in mAP. Based on the analysis in [

189], EfficientViT was proposed as the backbone network since it showed the highest performance improvement (+6% in mAP) compared to the original YOLOv8 backbone (baseline) and RepViT (+5.9% in mAP). Compared to the baseline model, Lin et al. [

120] demonstrated that using the NextViT backbone network improved mAP for citrus fruit detection by 4.0%. In comparative experiments involving six CNN- and transformer-based detectors, Lin et al.’s AG-YOLO performed best across all metrics. According to the study by Fan et al. [

129] on peach fruit detection, using FasterNet as the backbone resulted in a 5.2% increase in mAP. Fu et al. [

91] presented an Improved YOLOv8 network structure utilizing EfficientViT as its backbone. They achieved an mAP increase of 6.9% using a self-constructed dataset of tomato fruit.

Do et al. [

53] proposed an SC3T module as a replacement for the SPPF, combining the SPP and C3TR modules. As demonstrated by the conducted experiments, the mAP result was found to be promising, with a value of 78.1%, which represents a 5.8% increase over the baseline model. This was determined using a dataset focusing on strawberry diseases.

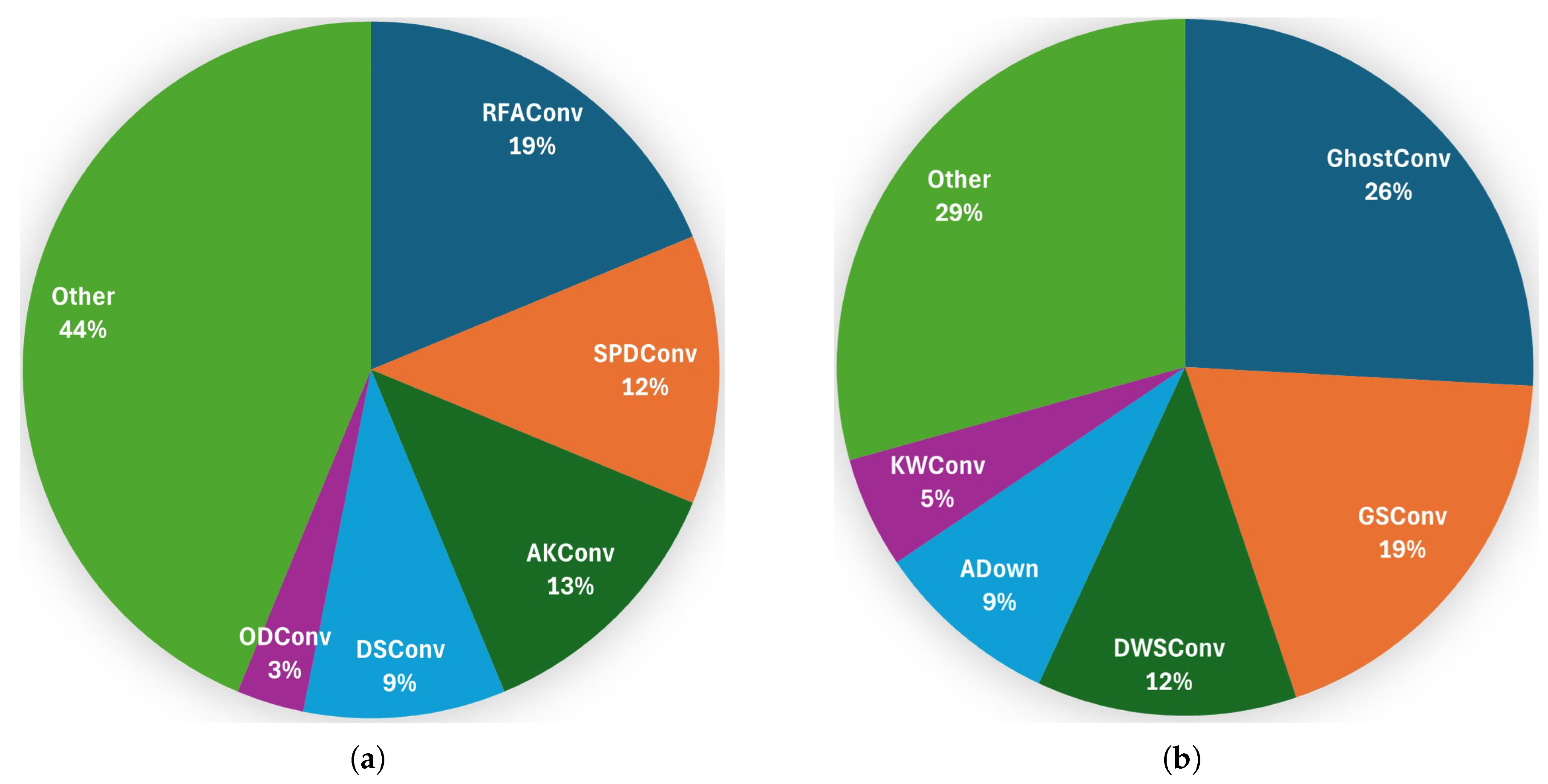

5.3. CBS Replacements

The regular convolution module, i.e., CBS (Conv2d + BatchNorm2d + SiLU), used in YOLOv8, applies a convolution kernel to each channel of the input feature map and adds the convolution results for each channel to create a single output feature map. This process is repeated on all channels of the input feature map to create multiple output feature maps [

88]. To reduce the number of parameters and the computational complexity of this process, various CBS improvements have been proposed, such as DWSConv, PDWConv, GSConv, and AKConv. Other CBS replacements for the Backbone (B) are listed in

Table A1. The classification of a CBS replacement as either a model for higher-accuracy or a lightweight model is not clear-cut. In some cases, it is somewhat fluid.

Among the reviewed papers, the most commonly used CBS replacement is RFAConv, followed by SPDConv and AKConv, for higher-accuracy models; see

Figure 8. For lightweight models, GhostConv is the most prevalent, followed by GSConv and DWSConv. Furthermore, it can be observed that the replacement of CBS modules at the backbone for higher-accuracy models has been proposed with a significantly higher frequency than at the neck. The underlying rationale is evident in the understanding that downsampling operations inherently entail a loss of information. This loss can be mitigated through the implementation of optimized convolution techniques in the early stage (i.e., at the backbone), thereby enhancing the efficacy of the feature extraction process.

Conversely, the replacement of CBS modules at the neck with lightweight models has been proposed at a significantly higher frequency than at the backbone. This objective is twofold: to reduce model complexity while preserving model accuracy.

The primary goal of replacing CBS should be to reduce model complexity while maintaining detection accuracy, as confirmed in [

192]. In this context, the Ghost Module proposed by Han et al. [

210] plays a prominent role. It is a model compression technique that reduces redundant feature extraction across channels. This results in a reduction of the number of parameters and the computational cost, while ensuring that model accuracy and complexity are maintained [

154].

He et al. [

50] compared the 3 different convolution modules DSConv, SPDConv, and KWConv, and found that SPDConv achieved the highest mAP increase of 1.2% compared to the baseline YOLOv8 model. However, it significantly increases the computation time to 43 GFLOPS. Replacing the standard convolution with KWConv increases the mAP by 1.0%, but the computation time is much lower at 14.2 GFLOPS. As a suggestion, KWConv is the right option when detection speed is a priority, SPDConv for applications where accuracy is the primary concern. Wang et al. [

69] showed that replacing CBS with SAConv resulted in a significant improvement in mAP of 1.67%.

Another convolution option is to use GSConv, a combination of Spatial Convolution (SC), DWSConv, and Shuffle operations, as suggested in [

187]. Compared with the baseline network YOLOv8n, the model fused with the GSConv module showed better detection performance, achieving a 1.9% increase in mAP. This finding suggests that the incorporation of GSConv (included in the backbone) and VoV-GSCSP (included in the neck) modules within the network architecture can enhance the diversity and richness of feature extraction while concurrently simplifying the network structure for grassland weed detection. In the comparative analysis of YOLO models for coffee fruit maturity monitoring presented by Kazama et al. [

162], the integration of the RFCAConv module into YOLOv8n achieved a mAP of 74.20%, outperforming the standard YOLOv8n by 1.90%. In their study on tomato leaf disease detection, Shen et al. [

30] showed that replacing the second CBS in YOLOv8 with GDC resulted in a remarkable 3.4% increase in mAP.

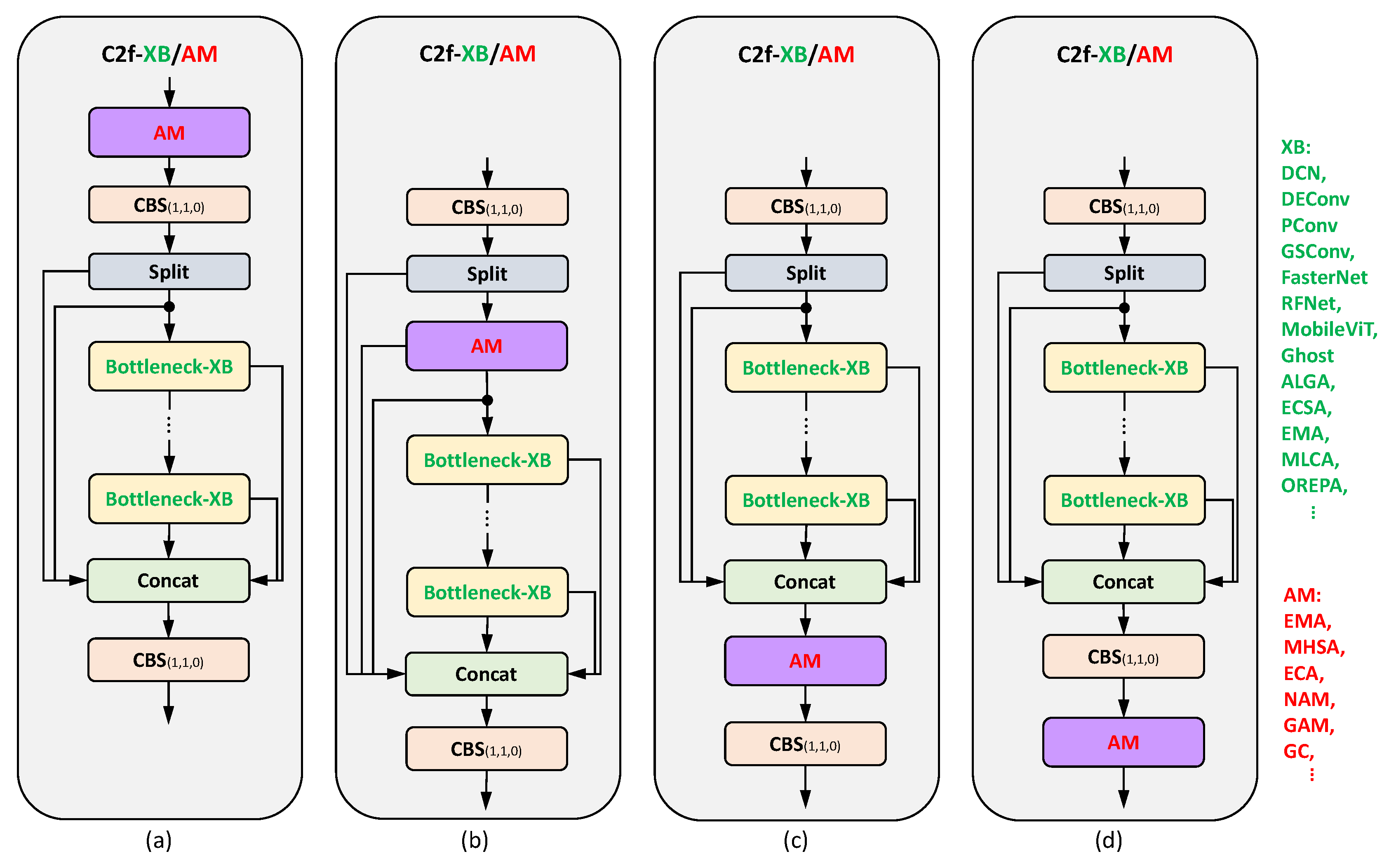

5.4. C2f Replacements

The C2f module is a pivotal component of the YOLOv8 network. Most of the improvements in the backbone thus focused on replacing C2f with various alternatives, such as C2f-DCN to improve the feature extraction ability of plant diseases [

14,

66], PDWConv to optimize the network efficiency [

110], RepBlock to improve accuracy and allow structural re-parameterization for increased detection speed [

37], OREPA module to accelerate the training process [

159], and GELAN to streamline the backbone network structure, optimize its feature extraction capabilities, and achieve model lightweighting [

41]. Novel options to strengthen the model’s feature extraction capabilities and thus improve the model’s detection accuracy are to integrate attention mechanisms into the C2f module, such as C2f-DCN, C2f-MLCA, and C2f-EMA. Other replacements of C2f are given in

Table A1. As for the classification of CBS replacements, it is not clear-cut whether a C2f replacement is a model for higher-accuracy or a lightweight model.

Note. There are different ways to integrate submodules into C2f to get new C2f structures. Most of these replace the bottleneck in C2f with a specific submodule, such as the DCN block or the FasterNet-EMA block; see

Figure 9.

Among the reviewed papers, the most commonly used C2f replacement is C2f-DCN, followed by C2f-DSConv and C2f-EMA, for higher-accuracy models; see Figure

Figure 10. A substantial body of research has been dedicated to replacing C2f, with a significantly smaller number of studies focusing on replacing CBS. This observation underscores the heightened significance of C2f in the YOLOv8 architecture.

For lightweight models, VoV-GSCS is the most prevalent, followed by C2f-Faster and C2f/C3-Ghost. C2f-DCN structures, which are based on deformable convolution, are typically integrated into networks to improve their ability to adapt to target deformation. This improves the networks’ ability to extract features of crops or crop diseases. Both VoV-GSCS (based on GSConv) and C2f-Ghost (based on GhostConv) are lightweight C2f structures that simplify the network architecture and reduce computational requirements.

The observations and conclusions concerning the frequency of C2f replacement are analogous to those concerning the CBS replacement when comparing the backbone and the neck.

Recently, Jia et al. [

170] investigated the performance effect of some C2f modifications (C2f-GOLDYOLO, C2f-EMSPConv, C2f-SCcConv, C2f-EMBC, C2f-DCNv3, C2f-DAM, and C2f-DBB) within the backbone network of YOLOv8. The experimental results presented there demonstrated that the inclusion of all these modules can improve the detection accuracy of YOLOv8 to a certain (small) extent (mAP: 77.8–80.4%). Relatively speaking, the C2f-DBB module showed greater potential in improving the network’s feature extraction capabilities [

170].

In [

66], Yao et al. showed that the C2f-DCN module alone improved the detection accuracy (mAP) by 2.13% for wheat disease detection. Guan et al. [

202] investigated replacing the C2f module with a C2f-DCN module at different positions in the backbone. When all four positions are replaced with C2f-DCN modules, the mAP of the model increases by 7.7% compared to the original model, indicating that the modified YOLOv8 network performs better in detecting maize plant organs.

Liu et al. [

161] introduced and embedded four attention mechanisms (CA, SE, LSKA, and EMA) into the C2f structure of YOLOv8s-p2 for comparative experiments on the detection of green crisp plum and demonstrated that embedding EMA yields the best performance values, e.g., +1.1% for mAP, compared to the YOLOv8s-p2 model as baseline. When the C2f-ALGA module was integrated, the experimental results described in [

195] showed a 2.9% increase in mAP compared to the YOLOv8s model. In the study of Jin et al. [

23] on rice blast detection, substituting C2f with C2f-ODConv led to a substantial 4.2% increase in mAP.

Yan and Li [

34] proposed replacing C2f with PFEM to introduce multilayer convolution operations within the feature maps. This achieves a richer feature representation, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to recognize tomato leaf diseases against complex backgrounds. The case study presented showed that integrating the PFEM module significantly improves model performance, increasing mAP by 4.5%.

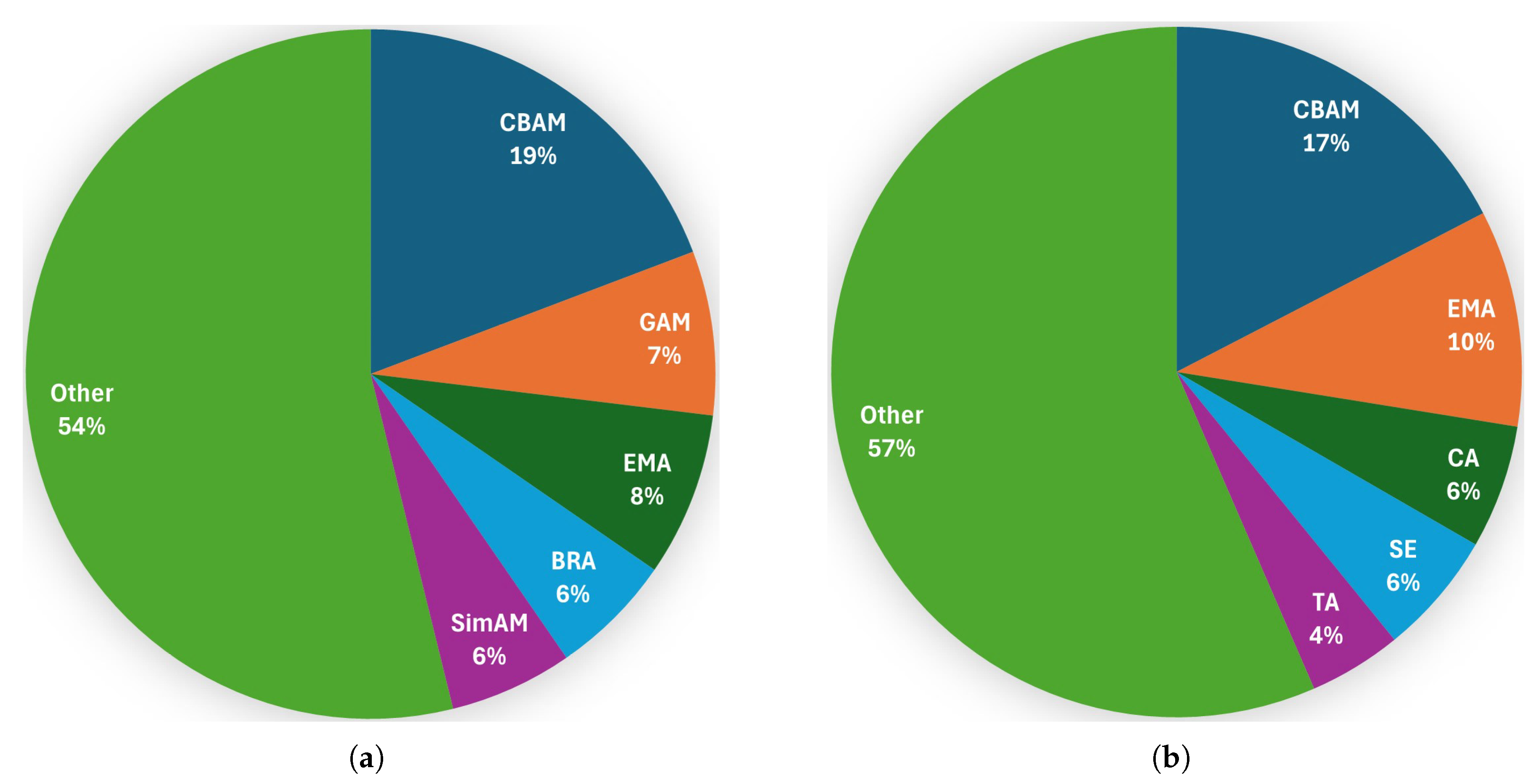

5.5. Additions of Attention Mechanisms

Basic YOLO models typically rely on global features or fixed receptive fields for object detection and localization. However, these are not optimal when dealing with complex scenes, occluded objects, or scale variations, such as those found in crop or disease detection tasks. To address these issues, researchers have initiated the exploration of the inclusion of attention mechanisms in the YOVOv8 architecture. The fundamental premise of attention mechanisms is to empower the model to autonomously discern the regions or features that are of paramount importance for the object detection task. Attention mechanisms draw inspiration from the human vision system, which focuses on essential regions in complex scenes. Similarly, by introducing attention mechanisms in computer vision, the model can focus more on the target regions and ignore background distractors, thereby improving object detection accuracy [

14]. However, it is important to note that including an attention mechanism in the network will inevitably increase computing costs.

Attention mechanisms employed in visual recognition tasks can be broadly categorized into three distinct types: channel attention, spatial attention, and mixed-domain attention. In recent work, for example, CA, EMA, ECA, and GAM, have been included somewhere in the backbone, usually before or after the SPPF module, to enhance the feature extraction capability of the model at different spatial scales and further improve the accuracy. Other suggestions for including attention mechanisms in the backbone are given in

Table A1. We do not categorize attention mechanisms because they are always integrated for higher accuracy, despite their varying levels of complexity.

Among the reviewed papers, the most commonly suggested attention mechanism in the backbone is CBAM, followed by GAM, then EMA; see

Figure 11.

Figure 12 illustrates the structures of CBAM and GAM, as well as their possible combination, as presented in [

151]. Both CBAM and GAM have two submodules that are applied sequentially to the input feature map: the channel attention module (CAM) and the spatial attention module (SAM). Convolution is used to calculate spatial attention and establish spatial location information. However, such calculations can only capture local relationships and cannot capture long-distance dependencies [

211]. Furthermore, attention mechanisms such as CBAM and GAM fail to consider the combined effect of both attentional mechanisms on the features. This effect is mixed after calculating one- and two-dimensional weights, respectively [

189].

In contrast, EMA uses a parallel processing strategy that considers feature grouping and multiscale structures. Using the cross-spatial learning method, the parallelization of convolution kernels seems to be a more powerful structure for handling both short- and long-range dependencies [

212]. Another promising attention mechanism that is simple yet effective is SimAM. It infers three-dimensional attention weights for intralayer feature maps without increasing the number of network parameters. This allows the model to learn from three-dimensional channels, improving its ability to recognize object features [

70,

189].

In [

14], a comparative performance analysis of 12 different attention mechanisms (CBAM, CA, GAM, ECA, TA, SE, SimAM, CoT, MHSA, PPS—Polarized Self-attention, SPS—Sequential Polarized Self-attention, and ESE—Effective SE) modules placed after the SPPF module led to the conclusion that TA yields a great performance improvement (mAP: +15.1%) for object detection of rice leaf diseases. Using SPS and GAM as attention modules also improved the YOLOv8 model’s mAP values and detection accuracy for the four types of rice leaf diseases by 15.3% and 15.1%, respectively. However, the detector’s performance was found to be highly unstable when detecting certain disease features, especially small targets like rice blast [

14]. Another comparative study in [

159] showed that the attention mechanism MPCA, placed after the SPPF module, has superior accuracy (+1.5% in mAP, compared to the baseline) for blueberry fruit detection compared to nine other attention mechanisms (SimAM, LSKBlock, TA, SE, Efficient Attention, BRA, BAMBlock, EMA, and CA). In addition, the introduction of two OREPA modules in the backbone and two OREPA modules in the neck resulted in a 2.7% improvement in mAP. The experiment in [

50] proved that TA, when added after each C2f module in both the backbone and the neck, led to a 3.6% improvement in mAP, compared to the baseline model YOLOv8s, for strawberry disease detection.

Under the EfficientViT backbone network, He et al. [

189] showed that adding DSConv and SimAM integrated into the neck led to an improvement of 6.4% in mAP, beating structures like EMA and BiFormer. Therefore, He et al. suggested the combination of C2f-DSConv and SimAM as the optimal method for weed detection tasks. Another comparison of the detection results of four different attention modules (EMA, SE, CBAM, and CA) in [

211] showed that under the premise of unchanged params and GFLOPs, EMA leads to the best results, i.e., an increase of mAP up to 3.55%, compared to SE, CBAM, and CA. Five different attention mechanisms (SE, CBAM, ECA, CAB, and BiFormer) were investigated in [

27] on the YOLOv8n baseline model for detecting tea defects and pest damage. The findings indicated that the incorporation of BiFormer into the model’s backbone network resulted in the best detection performance: +16.5% increase in mAP, followed by +11.1% when CAB was used to detect tea diseases and defects.

Yin et al. [

16] showed that the inclusion of the Multibranch CBAM (M-CBAM) module improved the detection performance in terms of mAP by 1.8% over the baseline model in their rice pest detection study. In the blueberry fruit detection study by Gai et al. [

159], adding the MPCA module resulted in a 1.5% increase in mAP. A comparison of incorporating different attention mechanisms (MPCA, CPCA, BRA, SE, BAMBlock, and SEAM) into the backbone led to the conclusion that the SEAM attention mechanism is particularly advantageous for detecting small objects [

170].

5.6. SPPF Replacements

YOLOv8’s SPPF structure generates feature maps of different scales through multiple pooling operations, often containing similar information. In addition, the simple concatenation of these feature maps can lead to duplicate representations of features, making the model overly dependent on similar feature representations and increasing the risk of overfitting. This problem can occur with weeds and crops because they often have symmetrical morphologies and are very similar both horizontally and vertically [

195]. SPPF employs three max-pooling methods to extract input features in series. Nonetheless, max pooling merely extracts the maximum value of the input feature. Consequently, it can only represent the local information of the input feature, while ignoring the global feature information of the input image [

38]. Consequently, some researchers have proposed the combination of average pooling and maximum pooling to enhance the extraction of global information by SPPF. Mix-SPPF is one such module. Replacing the SPPF module was suggested, e.g., SimSPPF, SPPELAN, and MDPM. Other SPPF replacements are listed in

Table A1. Among the reviewed papers, the most commonly used SPPF is SPPELAN, followed by SPPF-LSKA; see

Figure 13.

The ablation study by Wei et al. [

151] showed that the replacement of SPPF with SPPELAN alone leads to a significant increase in performance: +2.5% in Precision and +2.2% in Recall. In [

38], MixSPPF proposed by Ye et al. was compared with SPPF-LSA and SPPF-LSKA, and demonstrated superior performance in mAP, i.e., +3.89% compared to the baseline model with SPPF, for a case study of weed detection in cotton fields.

6. Neck Improvements

6.1. Neck Architectures

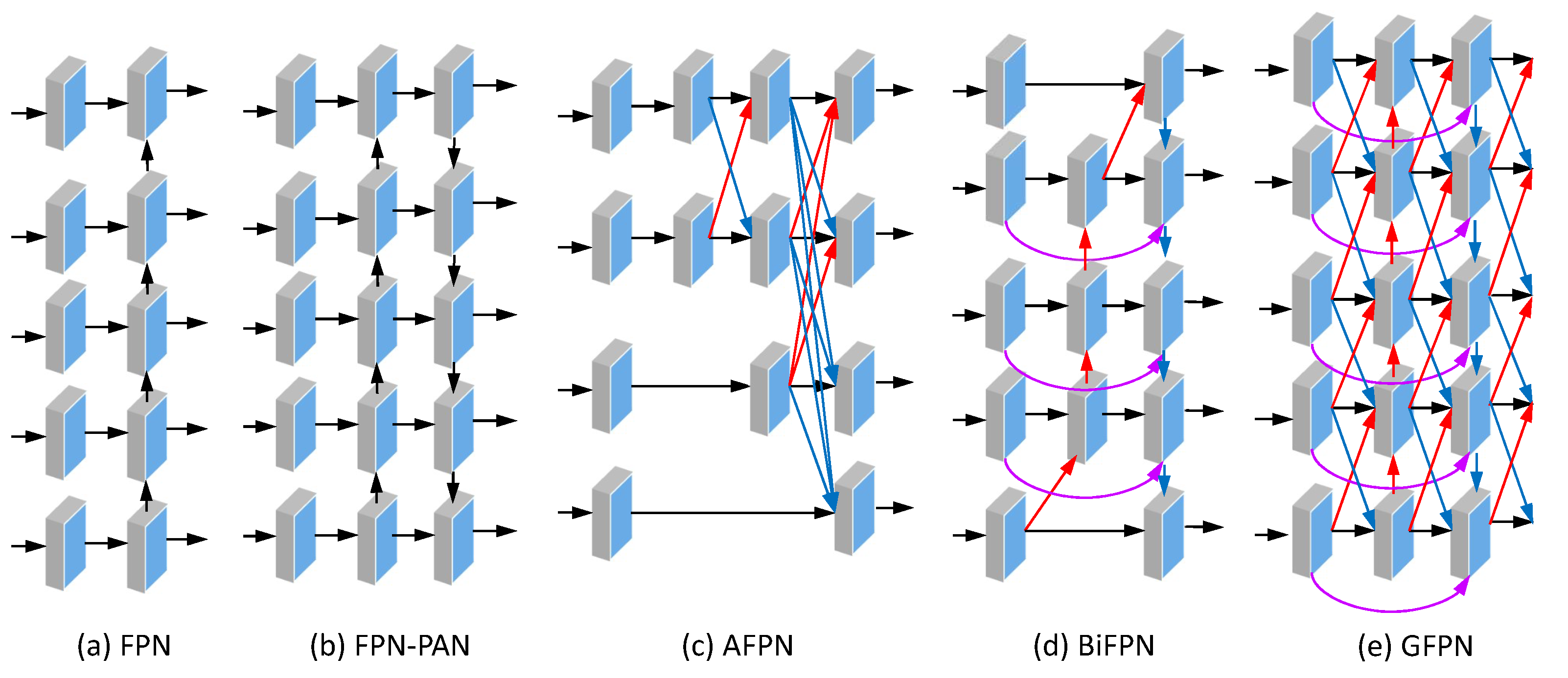

The most widely used architectures of YOLOv8’s neck are the FPN and the PAN. Beyond the FPN/PAN, some cascade fusion strategies have been developed and shown to be potentially effective in multiscale feature fusion, such as the (weighted) BiFPN, the GFPN, the AFPN, and the GFPN. Other neck architectures are listed in

Table A1. Some of these neck structures are illustrated in

Figure 14.

Among the works examined, BiFPN is by far the most commonly used neck architecture, followed by AFPN; see

Figure 13. The BiFPN’s bidirectional architecture facilitates the acquisition of supplementary contextual information through two-way feature exchange. This enhancement in efficiency of feature propagation within the network, in turn, elevates the quality of feature representation [

181]. The architecture of the AFPN is designed with the specific intention of addressing substantial semantic fusion gaps between adjacent layers of the backbone [

71].

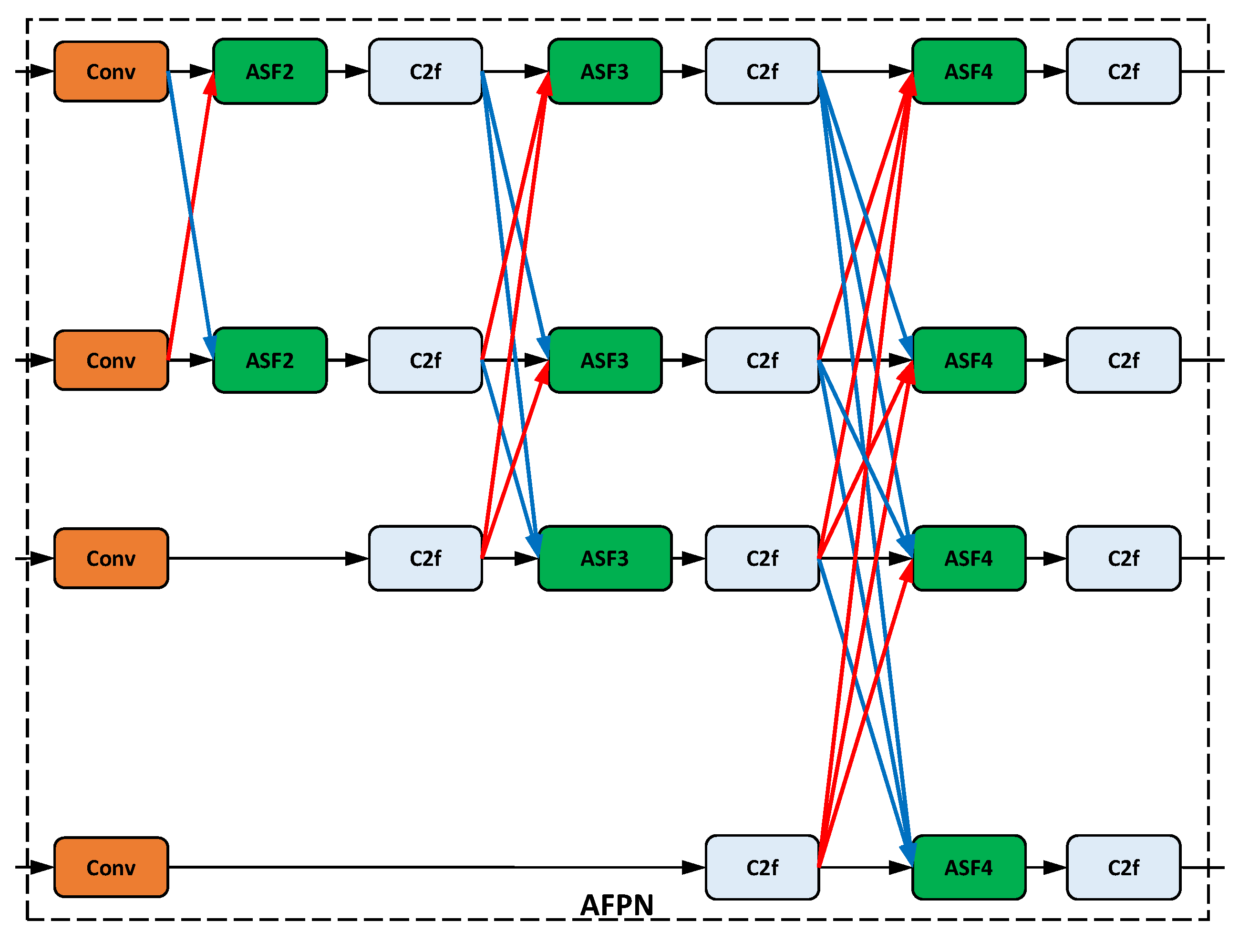

Figure 15 shows an AFPN configuration.

In [

97], it was shown that the introduction of the BiFPN in the neck enhanced the fusion capability of the model’s multiscale features for tomato ripeness detection, resulting in a 3% improvement in mAP compared to the baseline YOLOv8n. According to [

157], the mAP increased by 2.5% after replacing PAN as a neck network with BiFPN. According to the study by Fan et al. [

129] on peach fruit detection, using BiFPN as the neck resulted in a high increase in mAP by 9.6%. A higher improvement (+10.9% in mAP) when replacing FPN-PAN with BiFPN was reported in [

27] for detecting defects and pest damage in tea leaves.

Wu et al. [

141] implemented six different extensions to the YOLOv8n model, YOLOv8n-CARAFE, YOLOv8n-EfficientRepBipan, YOLOv8n-GDFPN, YOLOv8n-GoldYolo, YOLOv8n-HSPAN, and YOLOv8n-ASF, for grape detection. The results showed that YOLOv8n-ASF achieved a mAP of 1.78% higher than the baseline model and demonstrated the best overall improvement in grape detection. Sun et al. [

64] showed that replacing the FPN-PAN neck design of YOLOv8 with an AFPN structure resulted in a 1.92% improvement in mAP for detecting pest species in cotton fields.

In their study, Wu et al. [

94] compared the performance of their MTS-YOLO algorithm with five other modifications of the YOLOv8 neck network: YOLOv8-EfficientRepBiPAN [

215], YOLOv8-GDFPN [

216], YOLOv8-GoldYOLO [

217], YOLOv8-CGAFusion [

218], and YOLOv8-HS-FPN [

219]. It was shown that MTS-YOLO gave the best overall performance, e.g., +1.4% in mAP compared to the original YOLOv8n model. In the ablation study of Chen et al. [

156] on melon ripeness detection, the integration of HS-PAN improved mAP by 2.6%.

6.2. CBS Replacements

As for the backbone, similar CBS replacements can be incorporated into the neck. Prominent options are KWConv, PDWConv, RFAConv. The lightweight subsampling convolution block, called ADown, was introduced in YOLOv9 with the specific purpose of enhancing object detection tasks, as described in [

60]. Other CBS replacements for the Neck (N) are listed in

Table A1. Among the reviewed papers, the most commonly used CBS replacement in the neck is GhostConv, followed by GSConv, then DWSConv; see

Figure 8.

Wang et al. [

220] showed that replacing standard convolution operations with RFAConv modules in the neck mainly reduces the computational cost, thereby increasing the computational speed. Note that the ALSA module relies on the structure of the RFAConv module [

28]. Deng et al. [

122] showed that replacing CBS with GhostConv resulted in a remarkably high 14% improvement in mAP over the original YOLOv8 model for citrus color identification. Replacing the standard CBS modules with ADown modules in both the backbone and neck improved the mAP by 1.3% in the leaf disease detection study by Wen et al. [

86]. Including KWConv in both the backbone and the neck increased the mAP by 3.5% in the ablation study by Ma et al. [

203] on the recognition of desert steppe plants.

6.3. C2f Replacements

In principle, the same C2f modules can be used for the neck as for the backbone. Special C2f replacements introduced in the neck are the lightweight C2f-Ghost [

16,

80,

111] and C2f-Faster [

92,

130] to significantly reduce the number of parameters while improving detection performance. The integration of attention mechanisms, such as EMA and LSKA, was proposed to enhance the model’s capacity to detect small targets and discern ambiguous characteristics. This integration resulted in the development of the C2f-EMA module and the C2f-LSKA module, as outlined in the works of Zhao et al. [

178] and Fang and Yang [

177], respectively. Other C2f replacements for the neck are listed in

Table A1.

Among the works examined, VoV-GSCSP is the most commonly used C2f module in the neck, followed by C2f-Faster, for lightweight YOLOv8 models; see

Figure 10. For higher-accuracy YOLOv8 models, most researchers used C2f-DCN in the neck.

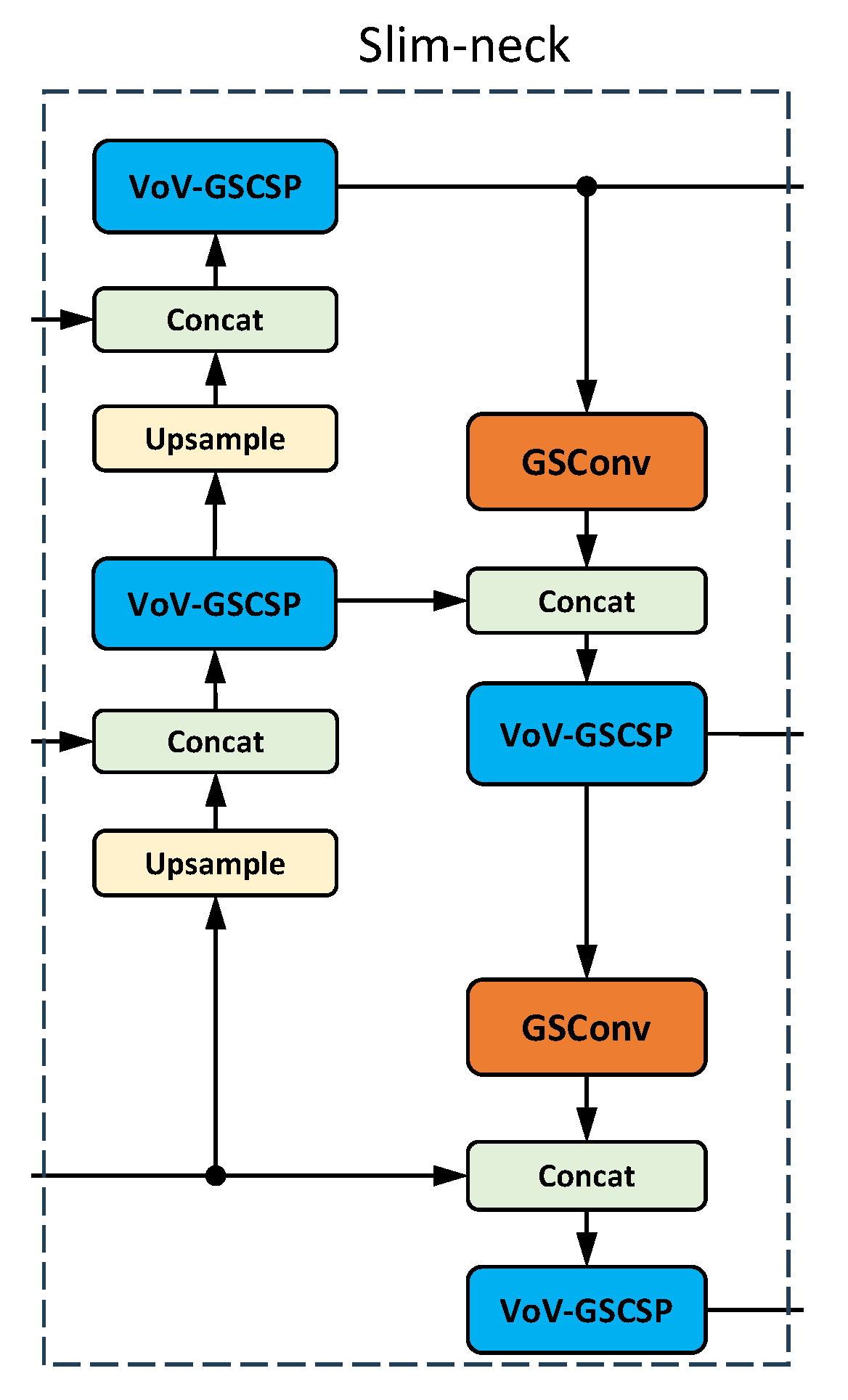

Many studies [

43,

48,

72,

93,

112,

139,

190,

221] adopted the Slim-Neck design concept [

222] for the neck components of YOLOv8, balancing feature extraction performance while significantly reducing model complexity and computational costs. The Slim-Neck architecture (

Figure 16) consists of two components: a lightweight VoV-GSCSP module that replaces C2f and a GSConv module that takes the place of the standard Conv module. C2F-Faster is created by integrating the FasterNet module into the bottleneck, which makes the model more lightweight and reduces the network’s computational load.

Lu et al. [

14] showed that the C2f-DCNv2 module, when included in the backbone and the neck in place of C2f, helps to better align the irregular targets on the feature map. In the use case considered, this inclusion improved the mAP by 6% compared to the baseline YOLOv8n. Incorporating the EMA attention mechanism into the C2f within the backbone and neck of the base model (YOLOv8n-Pose) resulted in a 2% increase in mAP, with negligible impact on the number of parameters and computations, as shown in the experiments by Chen et al. [

142] for grape and picking point detection. The results in [

85] demonstrated that substituting C2f with C2f-ECA modules in the neck led to a substantial enhancement in plant disease detection through advanced spatial feature integration and characterization, resulting in a 1.9% increase in mAP. Replacing C2f with HCMamba resulted in a 2.7% increase in the mean average precision (mAP) in the study of Liu et al. [

31] on tomato leaf disease detection.

6.4. Additions of Attention Mechanisms

Attention mechanisms dynamically learn feature weights or attention distributions based on context and task requirements, allowing models to adaptively focus on key features [

223]. Various attention mechanisms have been proposed for inclusion in the neck network, such as CA, CBAM, EMA, and SEAM. Other suggestions for including attention mechanisms in the neck are given in

Table A1. The most commonly used attention mechanism in the neck is CBAM, followed by EMA, then CA; see

Figure 11. The CA mechanism incorporates positional information into channel attention, thereby enhancing the importance of key features and achieving long-range dependencies [

82,

224].

Attention mechanisms can be introduced at different positions in the neck layer: as a bridge between the backbone and the neck [

16,

60,

134], only to the FPN or only to the PAN [

188], to both the FPN and the PAN [

37], or at the exit of the neck (i.e., between the neck and the head) [

160,

191].

Deng et al. [

122] showed that introducing the MCA mechanism to focus on capturing the local feature interactions between feature mapping channels in citrus color identification led to a 7.8% improvement in mAP over the original YOLOv8 model. In the study by He et al. [

50], TA increased mAP by 2.4% when the Improved YOLOv8 algorithm was used to identify diseases in strawberry leaves.

In Lin et al.’s study [

173] on pineapple fruit detection, five attention mechanisms (EMA, CPCA, SimAM, MLCA, and CA) were compared during the selection process. The results showed that CA led to the highest level of attention toward the pineapple, increasing mAP by 4.8% and 5%, respectively, compared to EMA and MLCA.

Wei et al. [

151] proposed a peculiar yet interesting approach: combining the GAM and CBAM attention mechanisms and integrating them at the neck. This option can compensate for the shortcomings of the single CBAM attention mechanism and improve the accuracy of the model to a greater extent (+1.6% in Precision, +1.8% in Recall), as shown for the detection of maize tassels [

151].

The experimental results for mango inflorescence detection in [

185] indicated that adding GAM in series with C2f-Faster (C2f-Faster-GAM) to both the backbone and the neck improved the mAP by 2.2%, outperforming other attention mechanisms such as SE, CA, and CBAM.

6.5. Upsampling Replacements

Even the upsampling module in YOLOv8 can be replaced with lightweight versions like DySample or CARAFE. These substitutions can improve the model’s ability to detect important features during upsampling without adding additional parameters or computational overhead, thereby improving the network’s ability to extract disease-related features [

67].

In the use case in [

192], replacing Usample with DySample improved all metrics, e.g., +2.78% in mAP, for the same amount of GFLOPS (8.2). Deng et al. [

122] showed that using CARAFE led to a 3.9% improvement in mAP over the original YOLOv8 model for citrus color identification. In the study [

195], using the CARAFE module instead of Upsample resulted in a 2.1% increase in mAP when the proposed Improved YOLOv8 algorithm was applied to the CottonWeedDet3 dataset.

7. Head Improvements

7.1. Loss Function Replacements

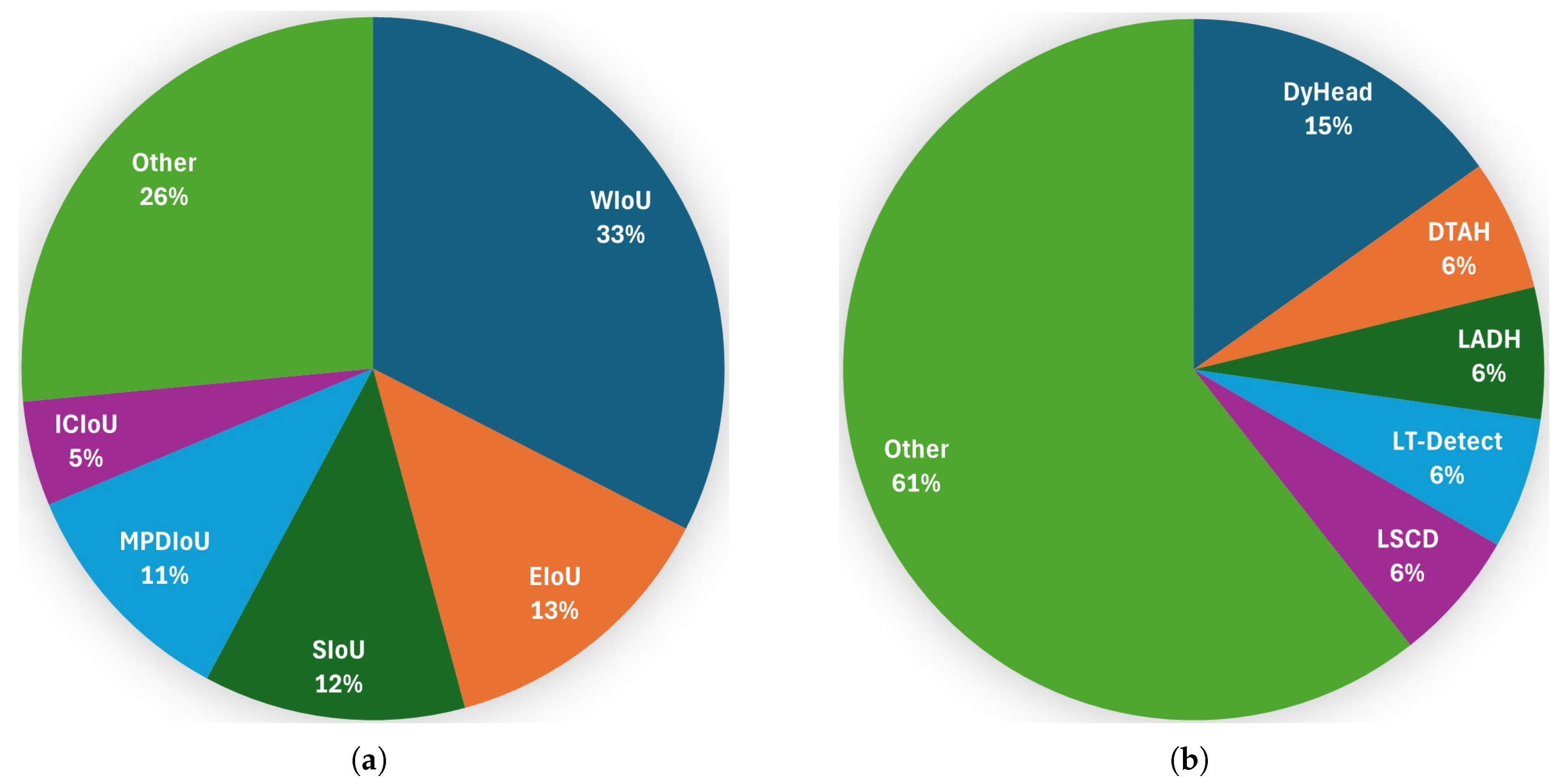

The design of an appropriate loss function is a critical step in enhancing the model’s detection accuracy. The YOLOv8 loss function is comprised of two primary components: CIoU loss and DFL loss for object position regression and VFL loss for object class classification. The bounding box loss, in particular, has been identified as a pivotal element within the object detection loss function. The detection of small (disease/crop) features and higher convergence speed may require alternative loss functions. Options for replacing the CIoU loss function can be found in

Table A1. Among the reviewed papers, the most commonly used CIoU loss replacement is WIoU, followed by EIoU and SIoU; see

Figure 17.

Zhang et al. [

179] compared four different loss functions, including CIoU, Shape-IoU, Inner-IoU, and ISIoU, and showed that ISIoU leads to better performance in detecting crop growth states. As demonstrated in the comparison presented in Wu et al. [

141], the YOLOv8n model employing the WIoU loss function exhibits a 3.11% higher level of detection accuracy compared to the original YOLOv8n model utilizing the CIoU loss function. This superior performance is also observed when benchmarked against all other loss functions considered.

Yao et al. [

66] proposed the redesign of the detection head based on the concept of parameter sharing and an improved loss function called Normalized Wasserstein Distance (NWD). A comparison was made between the original YOLOv8s algorithm and the updated version using the same loss functions as the original model, specifically CIoU, EIoU, SIoU and WIoU. It was found that WIoU and NWD show strong performance, with NWD beating all other approaches and showing the largest improvement of 3.06% in mAP [

66].

Wen et al. [

86] proposed the WSIoU loss function, a combination of Wise-IoUv3 and SIoU, and compared it with eight other loss functions, including GIoU, SIoU, EIoU, CIoU, DIoU, SIoU, WIoUv3, and MPDIoU. The results showed that WSIoU achieved the highest detection accuracy, outperforming all other loss functions. Jin et al. [

23] conducted trials on detecting rice blast and found that the YOLOv8 model performs optimally with WIoUv3 as the loss function. This improved the mAP by 3.8% compared to CIoU.

7.2. Other Improvements in the Head

Several other head improvements have been proposed in the literature; see

Table A1. The ASFF mechanism can be integrated into the original detection framework to improve the spatial consistency and detection accuracy of small-sized targets [

194]. Other measures to improve the head are listed in

Table A1. Among the reviewed papers, the most commonly suggested improvement to the head are the dynamic ones (DyHead, DTAH) to increase the flexibility in detecting plant parts (crops or diseased regions) of varying sizes; see

Figure 17.

A significant number of researchers suggest integrating AM, such as ARFA and SEAM. On the other hand, many authors have proposed lightweight versions, which are useful for real-time critical applications. The standard YOLOv8 detection head accounts for approximately 25% of the model’s parameters.

In the study of Jia et al. [

170], it was concluded that DyHead contributes more significantly to the performance improvement of the soybean pod detection model. DyHead has been demonstrated to dynamically adjust the model’s attention across different scales and occlusions, thereby enhancing its capacity to detect strawberries in complex, overlapping scenarios, as outlined in [

107]. As with all lightweighting measures, LADH reduces the training time and the number of parameters. However, it usually increases the mAP, as shown in [

208] for seedling growth prediction.

The experimental study in [

63] showed that the incorporation of SEAM into the detection head resulted in a 1.1% improvement in mAP compared to the baseline model. This indicates that SEAM improves detection in complex natural scenarios with highly occluded diseased cucumber leaves [

63]. The addition of an auxiliary detection head resulted in a 2.7% increase in mAP in the Fu et al. [

91] study for the identification of tomato fruit. Integrating ARFA-Head optimized the performance in multiscale object detection. Specifically, it increased the mAP by 4.3% in tomato leaf disease detection, as demonstrated in Yan and Li’s study [

34].

8. Some Selected Improved YOLOv8 Architectures

We will now briefly review and assess some improved YOLOv8 architectures to demonstrate their composition and complexity as prime examples of modular YOLOv8 architectures:

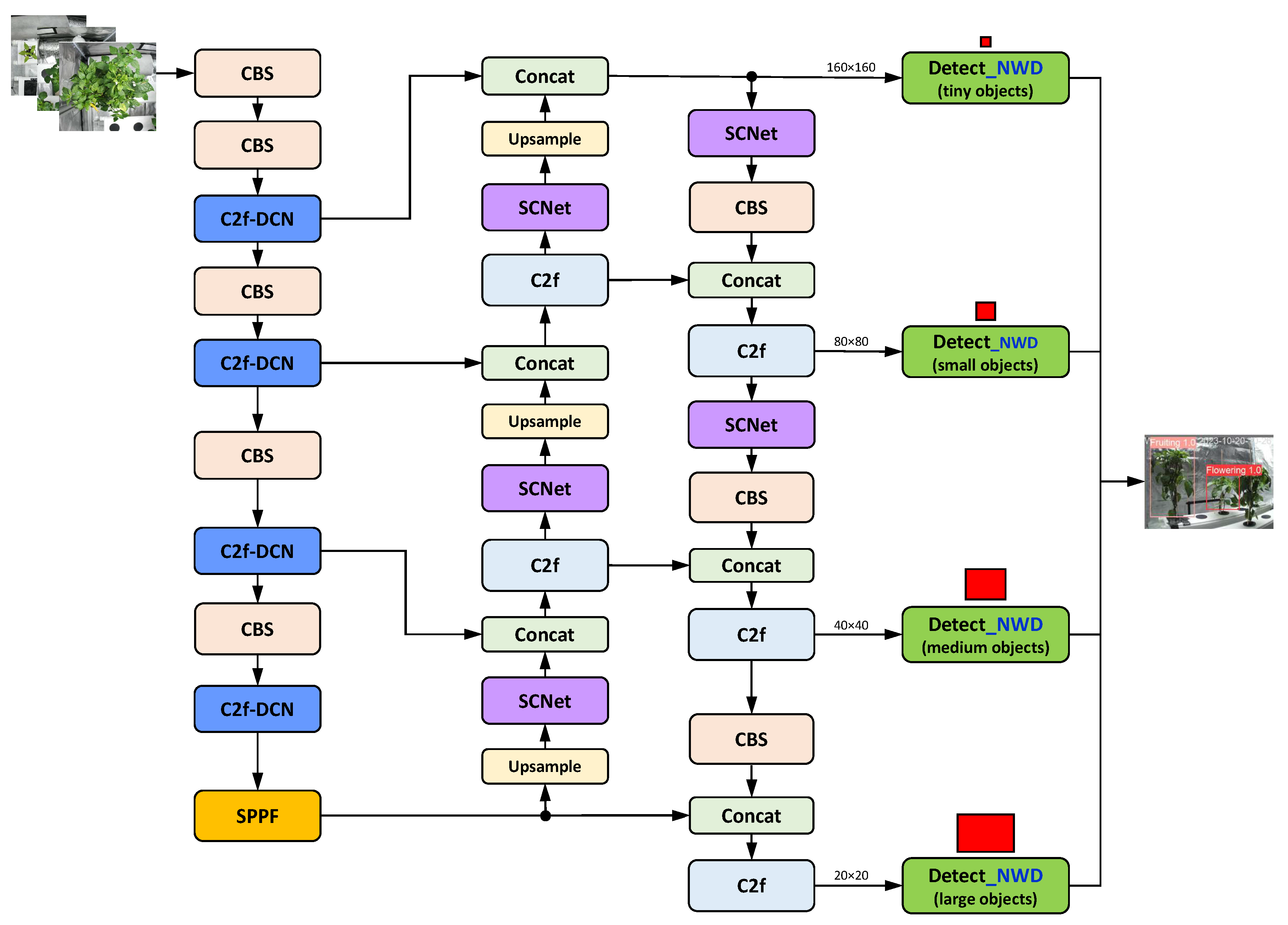

Yao et al.’s YOLO-Wheat (Figure 18): This wheat pest and disease identification algorithm replaces the C2f modules in the backbone with C2f-DCN modules, while also adding SCNet attention modules to the neck. Additionally, it uses the NWD loss function instead of CIoU in the head to calculate the similarity between boxes and frames. The YOLO-Wheat model achieved an mAP of 93.28%, which is 12.47% higher than the baseline YOLOv8s model. The model’s recall increased by 12.74%, while the FPS decreased by 8.99%. We expect higher performance values when the YOLO-Wheat structure is enhanced by integrating CBS replacements.

Shui et al.’s YOLOv8-Improved (Figure 19): The YOLOv8-Improved model uses C2f-MLCA instead of C2f modules and BiFPN instead of PAN to enhance multiscale feature fusion. In addition, WIoU is incorporated in place of CIoU. The model performed well in the study [

157] on detecting the maturity of flowering Chinese cabbage. It reached an mAP of 91.8% and a recall of 86.0%, which are 2.7% and 2.9% higher than the baseline YOLOv8 model, respectively. This model could benefit from the addition of attention modules in the neck and the replacement of CBS modules.

Yin et al.’s YOLO-RMD (Figure 20): The novel YOLO-RMD model, as presented in [

24] for rice pest detection, integrates C2f-RFAConv modules, replacing the C2f modules in the backbone, and adds MLCA modules between the neck and head. It also incorporates a dynamic head (DyHead), which integrates multiple types of attention across feature levels, spatial positions, and output channels [

225]. Yin et al. achieved very high mAP and recall values of 98.2% and 96.2%, respectively. This represents a 3% increase in mAP and a 3.5% increase in recall compared to the baseline YOLOv8n model. However, this was accompanied by an increase in the model’s parameter count and a corresponding decrease in detection speed [

24]. Given this, it seems unlikely that replacing or adding more modules would significantly improve the accuracy. On the other hand, the level of accuracy of YOLO-RMD can be maintained while making it significantly lighter by integrating modules designed for this purpose. This would increase the detection speed, allowing for better deployment to edge computing devices.

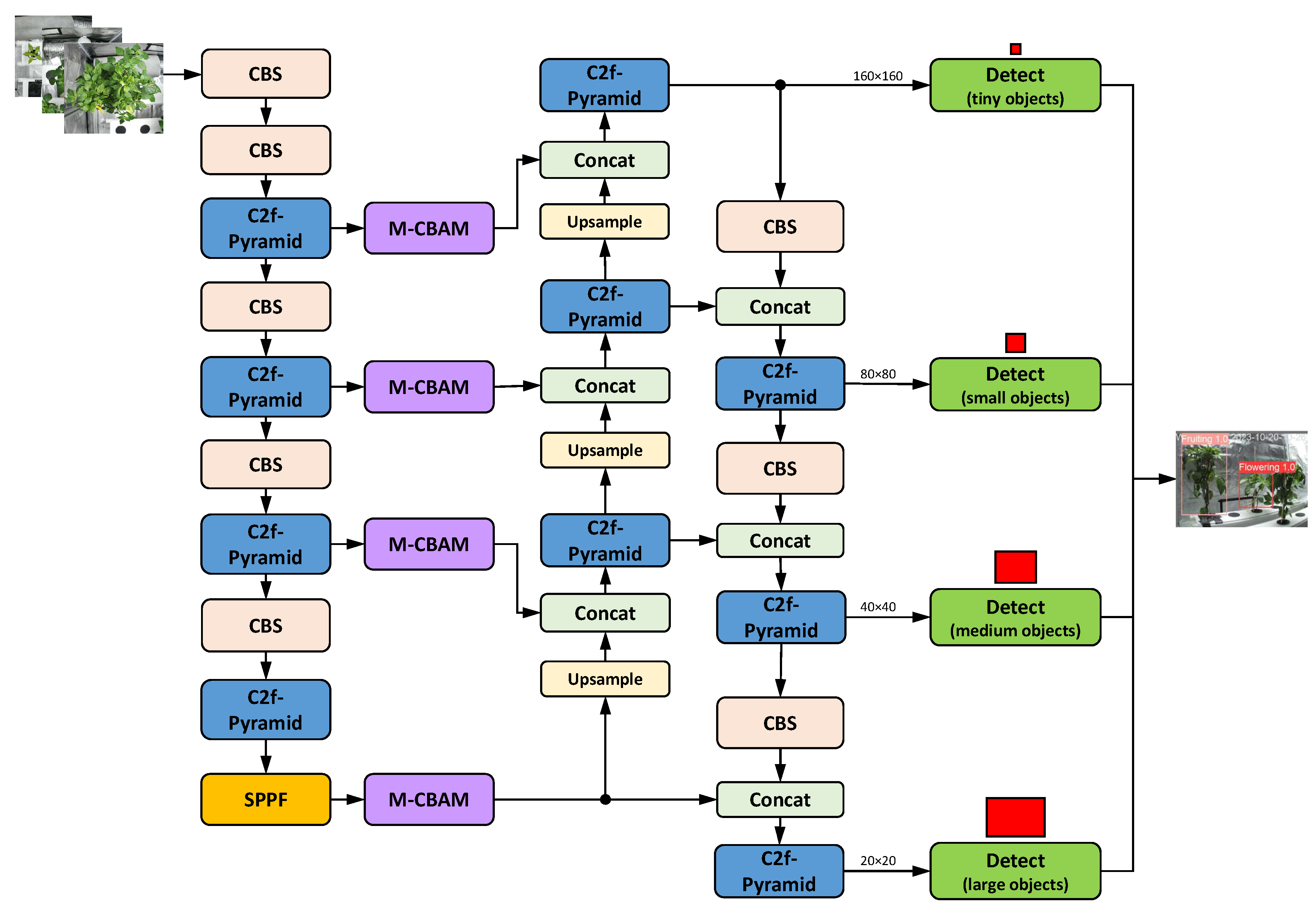

Cao et al.’s Pyramid-YOLOv8 (Figure 21): Pyramid-YOLOv8 was developed in [

15] for rapid and accurate rice leaf blast disease detection. Throughout the entire network, the algorithm uses C2f-Pyramid modules instead of C2f modules. It also adds M-CBAM modules, which serve as a bridge between the backbone and the neck. Pyramid-YOLOv8 demonstrated good performance, achieving an mAP of 84.3% and a recall of 75.7%. This represents a 6.1% and 3.9% improvement, respectively, over the baseline YOLOv8x model. Therefore, there is still room for improvement in terms of accuracy, which can be achieved by modifying the head. On the other hand, the Pyramid-YOLOv8 model still requires significant computing resources, making it difficult to deploy on resource-constrained edge devices, as concluded in [

15]. Therefore, improving the model’s real-time performance and adopting a lighter network are still open areas of research.

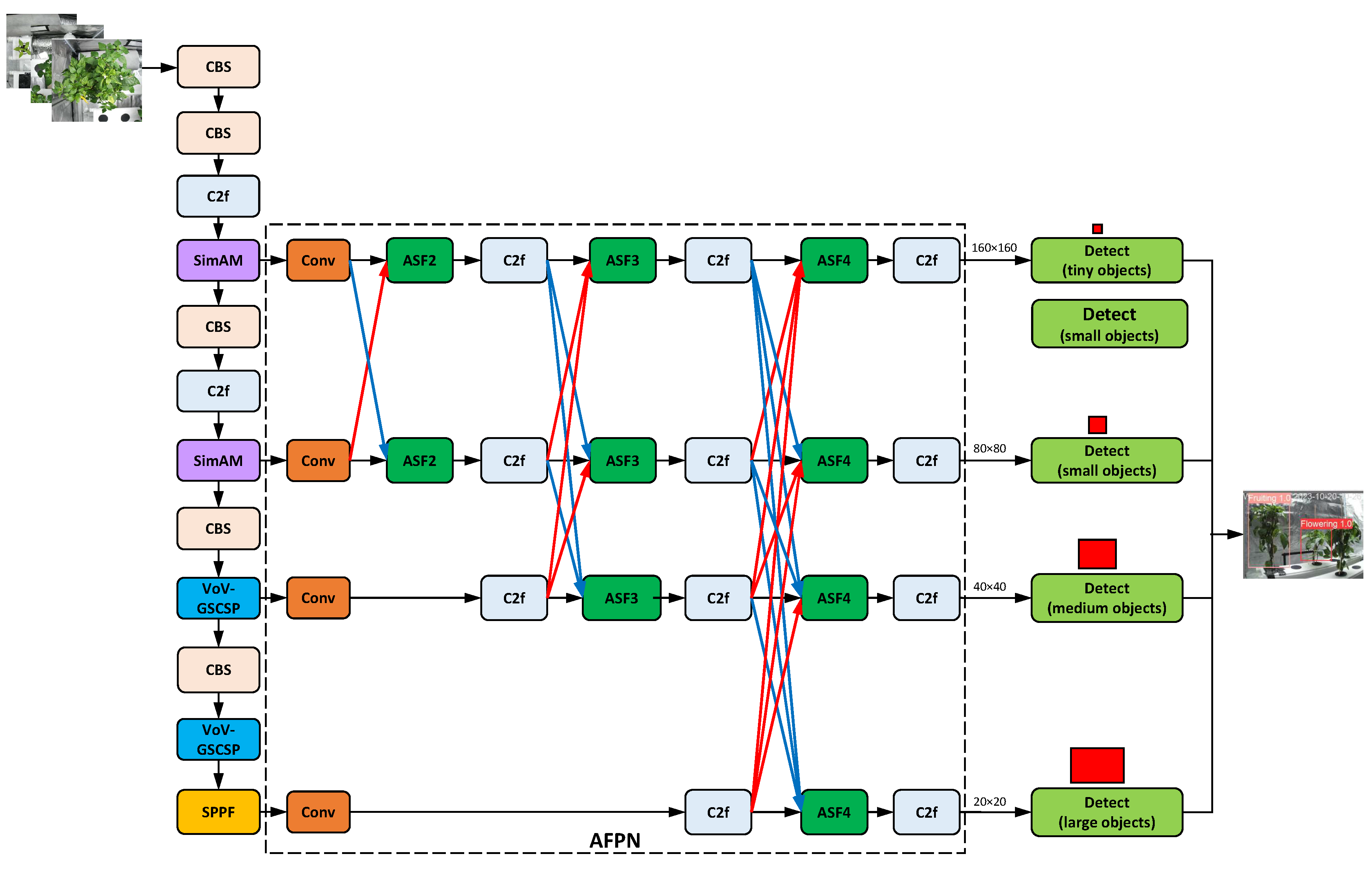

Sun et al.’s Improved YOLOv8l (Figure 22): In the enhanced YOLOv8 model by Sun et al. [

71], the last two backbone C2f modules are replaced with VoV-GSCSP modules. Additionally, two SimAM attention modules are incorporated into the backbone and the neck of the original network is replaced with a BiFPN. All of this results in a complicated, nonhomogeneous model. Compared to the baseline YOLOv8l model, the Sun et al. model’s parameters and GFLOPs are reduced by 52.66% and 19.9%, respectively. Meanwhile, the model’s mAP improved by 1%, and its recall improved by 2.7% [

71], achieving an mAP of 88.9% and a recall of 80.1%. It can be concluded that the enhanced YOLOv8 model effectively balances resource consumption and detection accuracy. However, there is still room for improvement in terms of accuracy, which can be achieved by modifying the head.

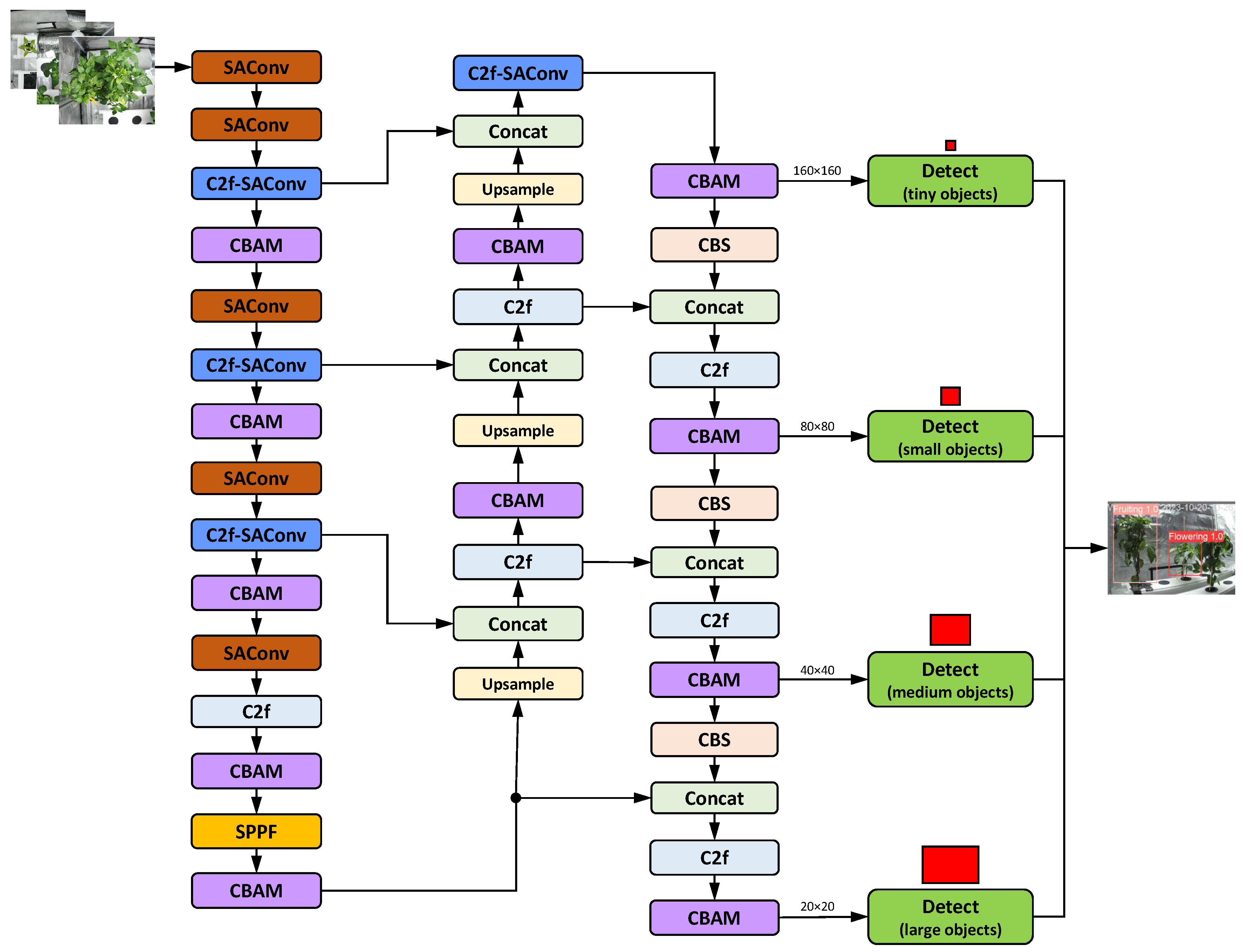

Wang et al.’s LSD-YOLO (Figure 23): LSD-YOLO uses SAConv instead of CBS and C2f-SAConv instead of C2f in all positions of the backbone. Additionally, it incorporates CBAM modules throughout the entire network, including the backbone and neck. Among the reviewed architectures, it has the highest number of modules and thus builds the most complex structure. LSD-YOLO achieved an mAP of 92.89% and 88.36% for healthy and diseased lemons, respectively. Compared to the YOLOv8n baseline model, LSD-YOLO achieved an mAP of 90.62%, an improvement of 2.64%, with only a 0.34 million parameter increase [

69]. Therefore, despite its relative complexity, the LSD-YOLO model provides accurate recognition of healthy and diseased lemons without significantly increasing the computational burden. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement in the neck (more C2f replacements, CBS replacements) and head areas.

9. Discussion and Recommendations

Based on our comprehensive review and analysis, we offer the following recommendations for each YOLOv8 section/component that could be replaced or improved:

Pyramid structure: In applications where small objects, such as berries, need to be detected, or when plant images have low resolution or contrast and need to be captured from a long or variable distance (e.g., by drones), the original YOLOv8 does not perform optimally. Small objects can easily be obscured by other objects or the background, particularly in dense scenes. Furthermore, background noise can resemble small objects, which increases the risk of false positives [

226]. The incorporation of a tiny object detection layer at 160×160 resolution (P2) has been demonstrated to augment the precision of the YOLOv8 network in detecting small and medium-sized object targets. Thus, we recommend the tiny object detection layer to be the default in modular YOLOv8 architectures.

-

Backbone/CBS: The use of ordinary convolution operations to extract local features from an image by performing sliding operations on the input data through a convolution kernel has become standard practice for object detection tasks. However, standard convolution (Conv2d+BatchNorm2d+SiLU) presents some challenges, particularly when the receptive field size is fixed. This can limit the model’s ability to capture information at different scales in the input data. Local connectivity may cause the model to overlook global information, negatively impacting performance [

69]. Therefore, we suggest replacing the conventional CBS with convolution modules that adaptively adjust the sensing field according to changes in the target’s scale and position within the image. These modules capture global information about the entire image and work efficiently in a wide range of contexts. SPDConv and RFAConv are suitable options for applications where accuracy is the primary concern. In contrast, GhostConv and GSConv are the suggested options for applications where the main objective is model lightweighting that is required for embedded, edge, or mobile devices. Emerging options are SAConv and KWConv. SAConv improves object detection performance by applying different atrous rates to convolutions. It also incorporates a global context module and a weight-locking mechanism that enhances the model’s ability to capture and utilize information from local and global contexts [

69]. KWConv is an extension of dynamic convolution. It involves segmenting the convolutional kernel into nonoverlapping units and linearly mixing each unit using a predefined repository shared across multiple adjacent layers. KWConv replaces static convolutional kernels with sequential combinations of their respective blending results. This strengthens the dependency of convolutional parameters between the same and succeeding layers by dividing and sharing the kernels [

203].

To ensure consistency and homogeneity, the CBS should be replaced by one module throughout the entire network. Alternatively, one module could be used for each section of the model (i.e., the backbone, neck, and head).

Backbone/C2f: The standard C2f module in YOLOv8 uses a traditional, static convolutional computation. This method uses the same convolutional kernel to process different input information, which often leads to severe information loss [

23]. However, the C2f module should be modified to adapt to the deformation of targets to be detected. This can be best achieved by replacing traditional convolution modules in C2f with dynamic ones. Based on our analysis of the reviewed papers, we recommend C2f-DCN and C2f-EMA as optimal choices for achieving higher-accuracy models. For lightweight models, good options are VoV-GSCSP, C2f-Ghost, and C2f-Faster. Emerging options are C2f-ODConv, PFEM, and OREPA. PFEM uses innovative convolution and multilevel feature fusion techniques to effectively distinguish disease spots from the background. This allows the model to maintain high detection accuracy in complex environments [

34]. OREPA serves as a model structure for online convolutional reparameterization. The pipeline is composed of two stages, with the objective of reducing the training overhead by compressing complex training blocks into a single convolution [

159].

Backbone/IM: In the field of object detection for agricultural monitoring and harvesting tasks, deploying attention mechanisms enables networks to prioritize and allocate resources to critical areas. The analysis of the reviewed papers emphasizes the important role of these mechanisms. These mechanisms improve feature extraction, enhance model interpretability, and increase overall detection accuracy. Beyond the prominent and widely used CBAM and GAM, we recommend EMA, and particularly SimAM. The latter is a complete 3D weight attention network that outperforms traditional 1D and 2D weight attention networks. On the other hand, CA is recommended for lightweight models to improve the accuracy of the network with minimal additional computational overhead.

Backbone/SPPF: The main issue with the multi-scale feature extraction capability of SPPF is the redundancy of information in the fused feature maps [

195]. Therefore, enhanced modules are needed to better fuse multiscale features and improve the ability to identify important features. We recommend using SPPELAN or SPPF-LSKA as replacement for SPPF. SPPELAN uses a combination of Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP) and an Efficient Local Aggregation Network (ELAN) to achieve superior feature extraction and fusion: While SPP can handle inputs of varying sizes through its multilevel pooling, which incorporates pooling operations of various sizes, ELAN improves feature utilization efficiency by establishing direct connections between different network layers[

84]. The SPPF-LSKA module integrates the multiscale feature extraction functionality of the SPPF module with the long-range dependency capture capability of an LSKA mechanism. This integration enables the module to achieve more efficient and accurate feature extraction [

201].

Neck/Architecture: YOLOv8 uses a top-down FPN-PAN structure to fuse features at multiple scales. During the transmission of high-level semantic information, it disregards low-level details present in the feature fusion process. This approach does not take into account the unequal contributions of input features with different resolutions to the fused output features [

31]. To improve the model’s ability to detect objects at multiple scales, the neck network structure should be redesigned or extended so that it combines feature maps from different scales using cross-scale feature interaction mechanisms. At least, pathways need to be added from high-resolution features to low-resolution features. The most suitable and recommended options are BiFPN and AFPN, which are widely used in the reviewed literature. Emerging neck architectures are HS/LS-PAN and LFEP. The HS-FPN architecture integrates multiscale feature information to mitigate interference from complex backgrounds and enhance fruit detection accuracy. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the color of immature fruit surfaces is similar to the color of the surrounding leaves and canes. The distinction between color-changing fruit and the complex background is accentuated by the disruption caused by elements such as fluctuating illumination and occlusion [

156]. LFEP integrates four distinct scale feature maps through a series of upsampling and downsampling operations, thereby generating feature information at scales of 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32 for subsequent processing. During this process, the feature information is processed by a Comprehensive Multi-Kernel Module (CMKM), which contains large, medium, and small local feature processing branches [

33].

Neck/CBS: Beyond the prominent and widely used GhostConv, DWSConv and GSConv for lightweight models, we recommend RFAConv and DSConv for higher-accuracy models. Emerging options are MKConv and ODConv. MKConv is a multiscale convolution module that can be parametrized by a variety of configuration options. It can adapt flexibly to sampling shapes with specific data characteristics [

58]. ODConv is a dynamic convolution approach that learns convolutional kernel features in parallel throughout all four dimensions of the convolutional kernel space using a unique attention mechanism. By introducing four types of attention to the accumulation kernel and applying them gradually to the respective convolution kernels, ODConv significantly improves the ability to extract features at each convolution layer [

39].

Neck/C2f: Based on our analysis of the reviewed papers, we recommend C2f-DCN and C2f-EMA (as well as C2f-DCN-EMA) as the best options for creating more accurate models. Good options for lightweight models are VoV-GSCSP (within Slim-Neck), C2f-Ghost, and C2f-Faster. Emerging options include OREPA, LW-C3STR, and HCMamba. In contrast to conventional transformer networks, which rely on the global attention mechanism and exhibit high computational complexity, the SwinT network employs window-based attention mechanisms. This approach reduces computational complexity by confining attention computations to individual windows, thereby enhancing efficiency and reducing overheads. [

152]. HCMamba is a hybrid convolutional module that integrates local detail information, extracted via convolution, with global context information provided by a state-space model-based approach. This design improves the model’s ability to capture both global and detailed image features, thereby enhancing its performance in target localization and classification [

31].

Neck/AM: Attention mechanisms can be introduced at different positions in the neck layer: as a bridge between the backbone and the neck, only to the PAN, or at the exit of the neck, i.e., between the neck and the head. Beyond the prominent and widely used CBAM and EMA, we recommend GAM and CA. Emerging options are MLCA and TA. MLCA fully leverages the richness of features by integrating channel, spatial, local, and global information to improve feature representation and model performance. Additionally, MLCA uses a one-dimensional convolutional acceleration method to reduce computational demands and parameters [

75]. TA is a new method that uses a three-branch structure (a series of rotations and arrangements) to capture cross-dimensional interactions and compute attention weights. Unlike other attention methods, TA emphasizes multidimensional interactions without reducing dimensionality and eliminates indirect correspondences between channels and weights [

14].

Neck/Upsample: Basic YOLOv8 uses nearest neighbor interpolation for upsampling. Although this method is simple and computationally efficient, it does not fully exploit the semantic information within the feature map for certain object detection tasks [

195]. There are only two common options for Upsample replacements in improved versions of YOLOv8. We recommend using either DySample or CARAFE. Both are lightweight and efficient upsampling methods. DySample generates dynamic kernels and uses higher-resolution structures to guide the upsampling process. [

192]. CARAFE considers not only the nearest neighbor points but also combines the content information of the feature map. This facilitates the attainment of more precise upsampling through the process of recombining feature map information [

122].

Head/Detect: The standard YOLOv8 detection head has a limited ability to handle multiscale disease features because it uses fixed receptive fields [

34]. To address this problem, the introduction of dynamically adjustable receptive fields should improve detection accuracy and reduce errors caused by variations in the size of crops or disease spots. The module of choice is DyHead to substitute the original detection head module. We also suggest ARFA-Head as an emerging head version. ARFA-Head incorporates the RFAConv module, combining spatial attention with adaptive receptive fields. This allows the receptive field size to adjust dynamically and overcome the limitations of fixed receptive fields when handling complex, multiscale image inputs [

34].

Head/CoU: The CIoU is a key component of the bounding box prediction, as it quantifies the overlap between the predicted and ground truth boxes. The preferred function for replacing the CIoU loss function in the detection heads is the WIoU, which is widely used in the analyzed papers, followed by MPDIoU and EIoU.

These suggestions for selecting components serve as guidelines for implementing and applying advanced YOLOv8 algorithms for object detection in agricultural settings. The comprehensive analysis of numerous research papers reveals that the application of stacking modules does not yield substantial enhancements in model performance. Therefore, it is imperative to select network modules and sections that are tailored to the specific task at hand. To this end, combining and comparing different modules and subnetworks is always indispensable. To ensure consistency and homogeneity, the C2f or CBS should be replaced by one type of module throughout the entire network. Alternatively, one module type could be used for each section (i.e., backbone and neck).

10. Conclusions and Future Directions

In this paper, we presented the first detailed survey of the current state of object detection based on improved YOLOv8 algorithms, focusing on object detection in agricultural monitoring and harvesting tasks, and evaluated the proposed changes or improvements. We divided the improvement measures into individual sections (backbone, neck, and head) and components (CBS, C2f, AM, SPPF, Concat, Upsample, and Loss Function CIoU) of YOLOv8.

We highlighted the results of selected methods and/or comparative experiments regarding the introduced improvement or extension measures found in the reviewed literature. We provided recommendations for potential improvements to each component of YOLOv8 that could be replaced or enhanced. Based on these findings, we presented and evaluated improved YOLOv8 architectures from the reviewed literature to showcase their composition and complexity as prime examples of modular YOLOv8 architectures.

The detection of plant objects, such as crops, crop maturity, crop pose, picking points, plant growth stages, pests, and diseases in leaves or crops, is a constantly evolving area of research in agriculture and applied sciences. There are several promising future directions that researchers are exploring in this field:

Automatic generation of Improved YOLOv8 configurations: Tailored YOLOv8 configurations can be generated using optimization algorithms, such as grid search or genetic algorithms, based on objective functions to be defined for detection accuracy, parameter counts, or detection speed.

-

Check of the performance results of the reviewed YOLOv8 algorithms: The studies and results presented in the reviewed papers are all based on very different datasets and use partly divergent hyperparameters, etc. Therefore, the conclusions drawn in the papers are specific to the situation at hand and thus not transferable to other or similar situations. There is a great need for comparative studies of different models with different network structures on the same machine and computational environment, using the same datasets. This would provide fair and clear performance evaluations.

Moreover, we found that some papers (marked with

** in

Table A1) may contain incorrect or misleading DL procedures due to the fact that many groups and researchers around the world are applying AI techniques and sometimes overlooking fundamental aspects of data processing or modeling. For instance, data augmentation is a widely used technique in ML to enhance model generalization, yet its improper application —specifically, augmenting data before splitting them into training and test sets— can lead to significant data leakage and inflated performance metrics. We will address this problem in detail in an upcoming paper.

Investigating recommended extensions of primary YOLOv8 architecture examples: The further improvement suggestions for the examples of enhanced YOLOv8 architectures given in

Section 8 can be implemented and investigated in real use cases and comparative studies.

Investigation of transformer-based YOLOv8 algorithms: The inclusion of transformer networks into YOLOv8 is very promising in the future. Of the studies examined, only a few consider transformer mechanisms to optimize detection performance; see

Table A1. Transformer modules use the self-attention mechanism to capture global semantic information, such as long-range dependencies between fruits and stems. These modules can also effectively distinguish fruits from the background, preventing dense green leaves from being misidentified as fruits [

99]. However, transformer-based models require more computational resources. We found contradictory results and conclusions regarding the integration of transformer networks and their achieved performance for YOLOv8. This motivates us to address this challenging topic in the near future.

Benchmarking against other detectors: Meanwhile, higher versions of YOLO, i.e., YOLOv9–YOLOv12 have appeared and some improvement measures have been proposed and evaluated in recent papers. Analyzing these studies can expand our survey, which focuses on YOLOv8. Claims could be strengthened by a broader benchmarking against other state-of-the-art detectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.; Formal analysis, M.J.; Investigation, M.J.; Methodology, M.J.; Project administration, M.J.; Software Supervision, M.J.; Validation, M.J.; Visualization, M.J.; Writing - original draft, M.J.; Writing - review & editing, M.J.

Institutional Review Board Statement

INot applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in the review are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

This section contains the abbreviations used in the manuscript. They are listed according to the improvements or substitutions introduced in the YOLOv8 sections, as shown in the taxonomy in Figure 6.

Abbreviations Used for CBS Replacements Primarily Introduced for Lightweight YOLOv8 Models

| ADown |

Subsampled convolution |

| ALSA |

Attention Lightweight Subsampling |

| BConv |

Multi-modal hybrid convolution structure combining DWConv and PConv |

| CBRM |

Conv2d + BatchNorm2d + ReLu + MaxPool2d |

| DiSConv |

Distributed Shift Convolution |

| DWSConv |

DepthWise Separable Convolution |