1. Introduction

Skin diseases are among the most common health conditions affecting people worldwide, with a prevalence that continues to increase globally . Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for effective treatment and improved patient outcomes. However, visual diagnosis of skin conditions can be challenging due to the complex morphological patterns, similar appearances across different conditions, and the variability within the same disease .Traditional diagnostic approaches rely heavily on the clinical expertise of dermatologists, who may not always be readily accessible, particularly in resource-limited settings. This limitation often leads to delays in diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, the subjective nature of visual examinations can result in inter-observer variability and diagnostic inaccuracies .Deep learning has emerged as a promising solution to these challenges, with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) demonstrating remarkable capabilities in image classification tasks, including medical image analysis . Recent advances in CNN architectures have led to models that can match or even surpass human-level performance in various visual recognition tasks. Among these architectures, EfficientNet, developed by Tan and Le , has shown superior performance while maintaining computational efficiency through its compound scaling method. This makes it particularly suitable for medical imaging applications where both accuracy and resource constraints are important considerations.In this paper, we present a deep learning approach using EfficientNetB4 for the automated classification of six common skin diseases. We evaluate the model’s performance on a diverse dataset and analyze its strengths and limitations. The primary contributions of this work include:

Implementation of EfficientNetB4 for multiclass skin disease classification

Comprehensive performance evaluation across six distinct skin conditions

Analysis of class-wise performance and identification of challenging cases

Discussion of practical implications for clinical deployment

2. Related Work

Computer-aided diagnosis of skin diseases has been an active area of research, with various machine learning approaches being explored over the years. Traditional methods relied on hand-crafted features and conventional classifiers such as support vector machines (SVMs) and random forests . While these approaches demonstrated some success, they often struggled with the high variability and complexity of dermatological images.

The advent of deep learning has transformed the field, with CNNs becoming the dominant approach for skin disease classification. Esteva et al. were among the first to demonstrate the potential of deep learning in dermatology, using a GoogLeNet Inception v3 CNN to classify skin lesions with performance comparable to board-certified dermatologists.

Subsequent research has explored various CNN architectures for skin disease diagnosis. ResNet architectures have been widely adopted due to their ability to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem through residual connections . Researchers have also utilized VGG and MobileNet architectures for skin lesion classification, with varying degrees of success .

Transfer learning has emerged as a particularly effective approach in medical imaging, where pre-trained models are fine-tuned on domain-specific datasets. This strategy helps address the limited availability of large, annotated medical image datasets . Attention mechanisms and ensemble methods have been investigated to further improve classification performance .

Despite these advances, several challenges remain in automated skin disease detection, including class imbalance, inter-class similarity, intra-class variability, and the need for models that can generalize across diverse patient populations . EfficientNet architectures offer promising solutions to these challenges due to their balanced scaling of network dimensions (width, depth, and resolution) and strong performance-to-efficiency ratio [5].

The present work builds upon these foundations, specifically employing EfficientNetB4 for multiclass skin disease classification. We contribute to the existing literature by providing a comprehensive evaluation across six distinct skin conditions and analyzing the model’s performance in detail.

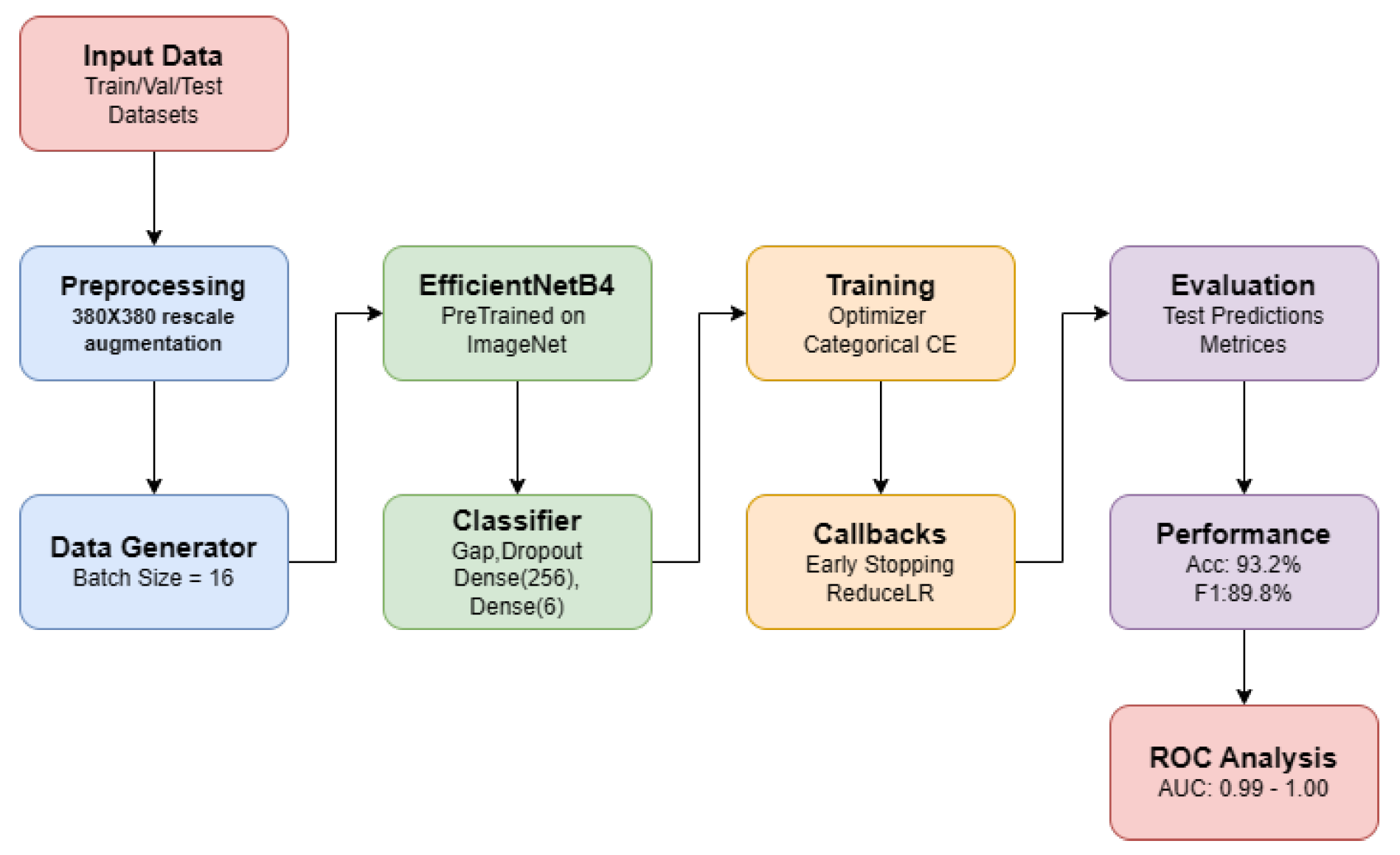

3. Methodology

A. Dataset

Our study utilized a comprehensive skin disease image dataset comprising six distinct categories: Benign, Malign, Akne, Pigment, Ekzama, and Enfeksiyonel. The dataset contains thousands of clinical images organized into class-specific subfolders. The distribution of images across classes is shown in

Table 1.

Table 1: Distribution of images across disease categories

The dataset was pre-split into test, validation, and training sets with roughly 15%, 70%, and 15% splits, respectively. This partitioning provides enough data for training while guaranteeing a strong assessment of the model’s generalization abilities.

3.1. Data Preprocessing

To guarantee fit with the EfficientNetB4 architecture and preserve enough detail for accurate classification, all images were resized to a consistent dimension of 380×380 pixels. We used several data augmentation strategies to the training set in order to improve the generalizing capacity and resilience of the model: Rescaling (1/255) for pixel value normalisation; Random rotation (±30 degrees); Shear transformation (range: 0.2); Zoom adjustment (range: 0.2); Horizontal flipping; Width and height shifts (range: 0.1). These augmentation methods increase the model’s capacity to identify conditions under different clinical imaging environments and help some classes with their limited sample size. To guarantee a fair assessment of the performance of the model, the validation and test sets underwent rescaling alone without any further augmentations.

3.2. Model Architecture

Our base model was pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset and consisted on the EfficientNetB4 architecture. EfficientNetB4 was chosen because it best balanced computational efficiency with model performance. With a given set of scaling coefficients, the architecture uses a compound scaling technique to consistently scale network width, depth, and resolution.

Eliminating the top classification layer and adding a custom classifier made especially for our particular work changed the base model. The whole model architecture comprises of:

EfficientNetB4 base (pre-trained on ImageNet, without top layer)

Global Average Pooling layer

Dropout layer (rate = 0.5) for regularization

Dense layer with 256 units and ReLU activation

Output Dense layer with 6 units and softmax activation

The global average pooling layer reduces the dimensionality of the feature maps while preserving spatial information. The dropout layer helps prevent overfitting by randomly deactivating 50% of the neurons during training. The final dense layer with softmax activation produces probability distributions across the six disease categories.

3.3. Training Configuration

The model was trained with the following configuration:

To improve training efficiency and model performance, we implemented several callbacks:

Early stopping with a patience of 5 epochs, monitoring validation loss

Learning rate reduction with a patience of 2 epochs and a factor of 0.3

Model checkpoint to save the best-performing model based on validation accuracy

The model was implemented using TensorFlow 2.x and trained on a NVIDIA GPU to accelerate the training process. The training process converged after approximately 17 epochs, as determined by the early stopping callback.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Training Performance

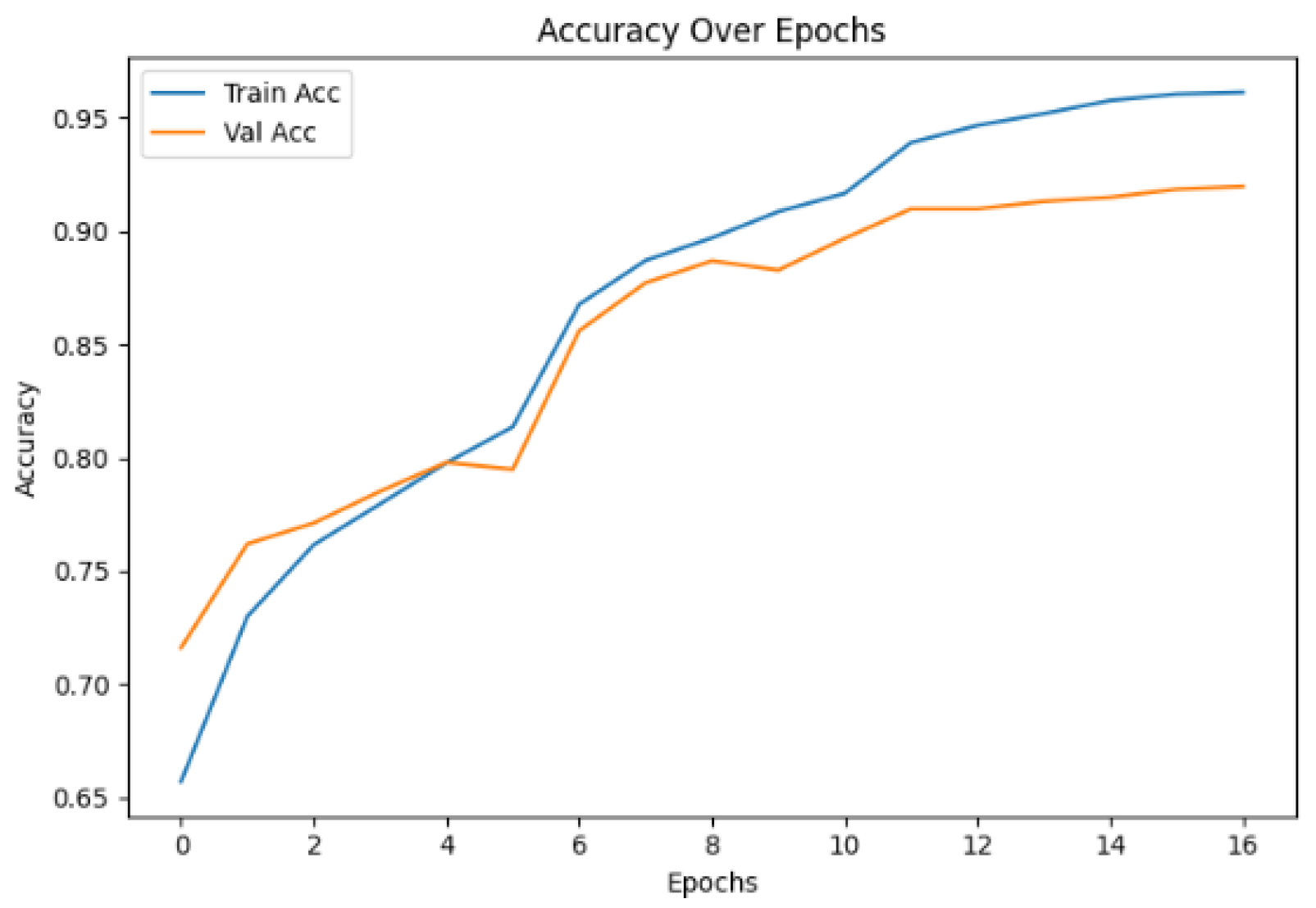

Figure 1 shows the progression of training and validation accuracy over epochs. The model has achieved final training accuracy of 96.2% and validation accuracy of 91.9%. The rapid initial improvement in both metrics indicates effective learning of discriminative features.

Training and validation accuracy over epochs.

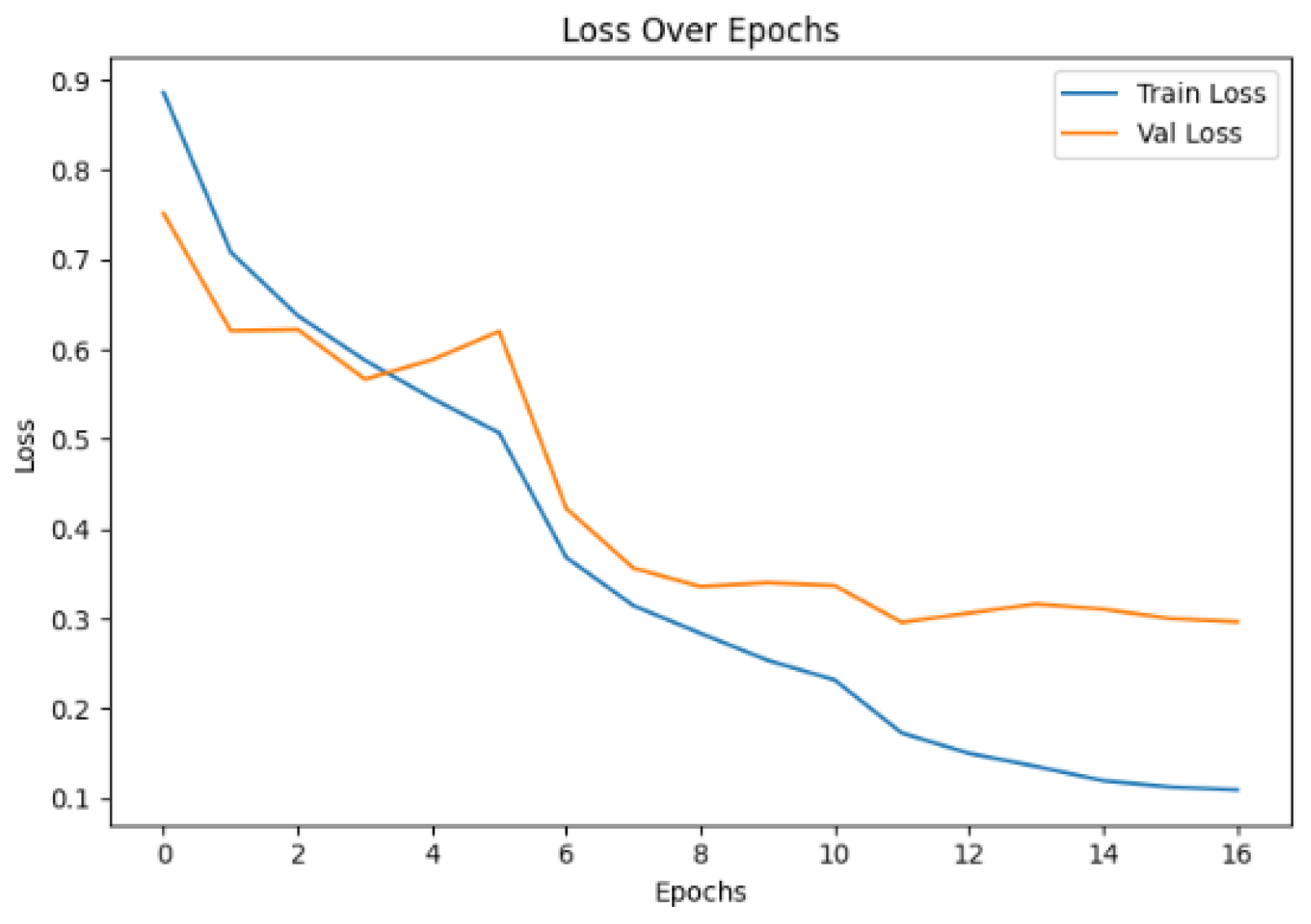

Figure 2 illustrates the corresponding loss curves. The consistent decrease in both training and validation loss demonstrates good convergence behavior. The model achieved final training loss of 0.11 and validation loss of 0.30.

Training and validation loss over epochs.

The gap between training and validation metrics suggests some degree of overfitting, despite the regularization techniques employed. However, the model’s strong performance on the test set indicates good generalization capability.

4.2. Test Set Performance

The model achieved an overall accuracy of 93.2% on the test set, demonstrating its effectiveness in distinguishing between the six skin disease categories.

Table 2 presents the detailed performance metric of each class.

Table 2: Class-wise performance metrics on test set

The model shows strong performance across most classes, with F1-scores ranges from 0.79 to 0.96. The highest performance is observed for the Benign class, which also has the largest number of samples. The Pigment class shows the lowest performance metrics, particularly in terms of recall (0.73), indicating challenges in correctly identifying all instances of this class.

4.3. Confusion Matrix

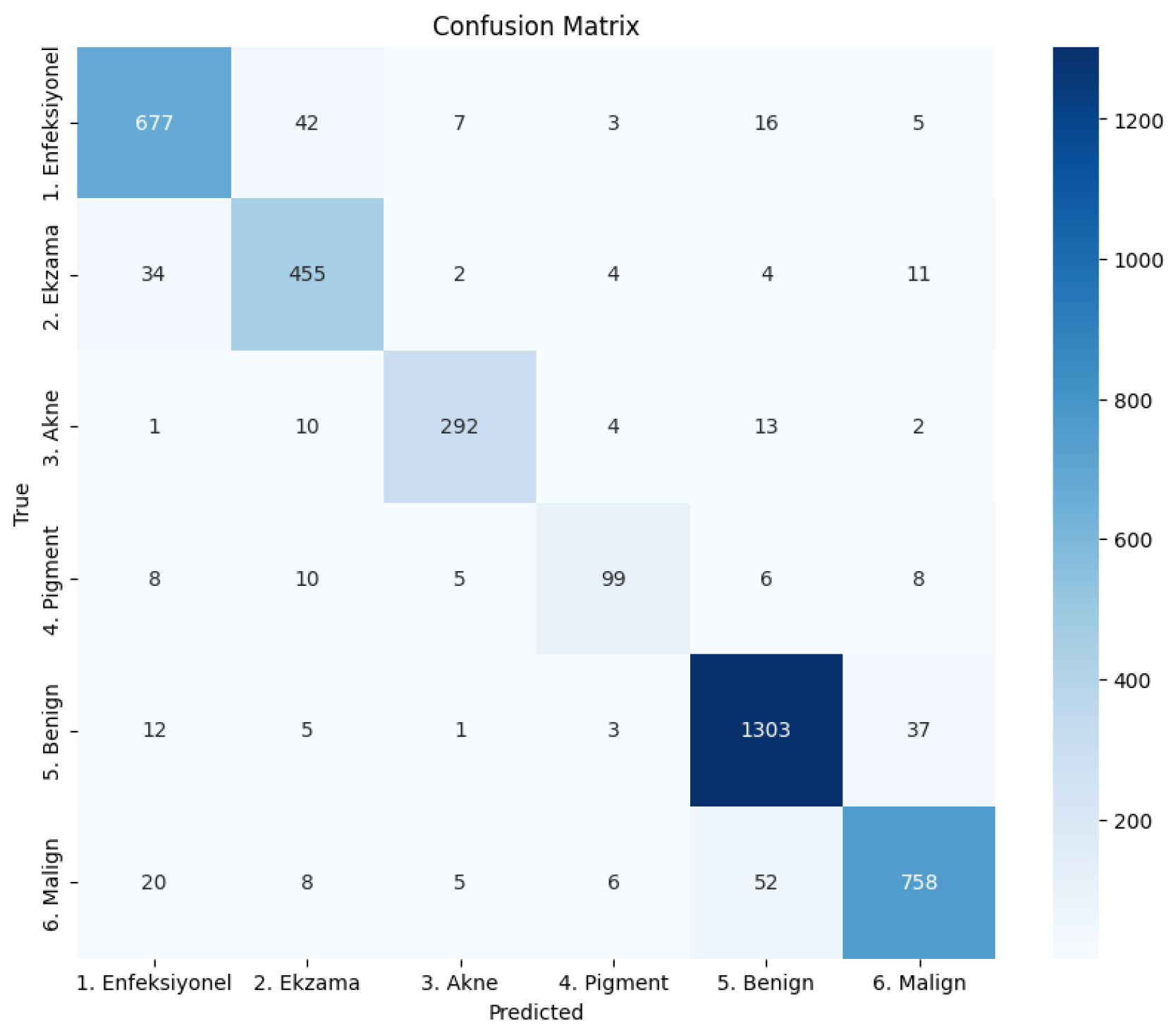

The confusion matrix provides further insights into the model’s classification behavior, revealing patterns of correct classifications and misclassifications across the different disease categories.

Confusion matrix showing classification results across the six skin disease categories.

From confusion matrix in

Figure 3, we observe:

The Benign class has the highest number of correctly classified instances (1303) with minimal misclassifications.

There is some confusion between Ekzama and Enfeksiyonel categories, with 34 instances of Ekzama misclassified as Enfeksiyonel and 42 instances of Enfeksiyonel misclassified as Ekzama.

The Pigment class shows significant misclassifications, particularly with Malign (8 instances) and Enfeksiyonel (8 instances), consistent with its lower recall value.

Misclassifications between Benign and Malign are relatively low (52 Malign samples misclassified as Benign, and 37 Benign samples misclassified as Malign), which is encouraging given the clinical importance of distinguishing between these two categories.

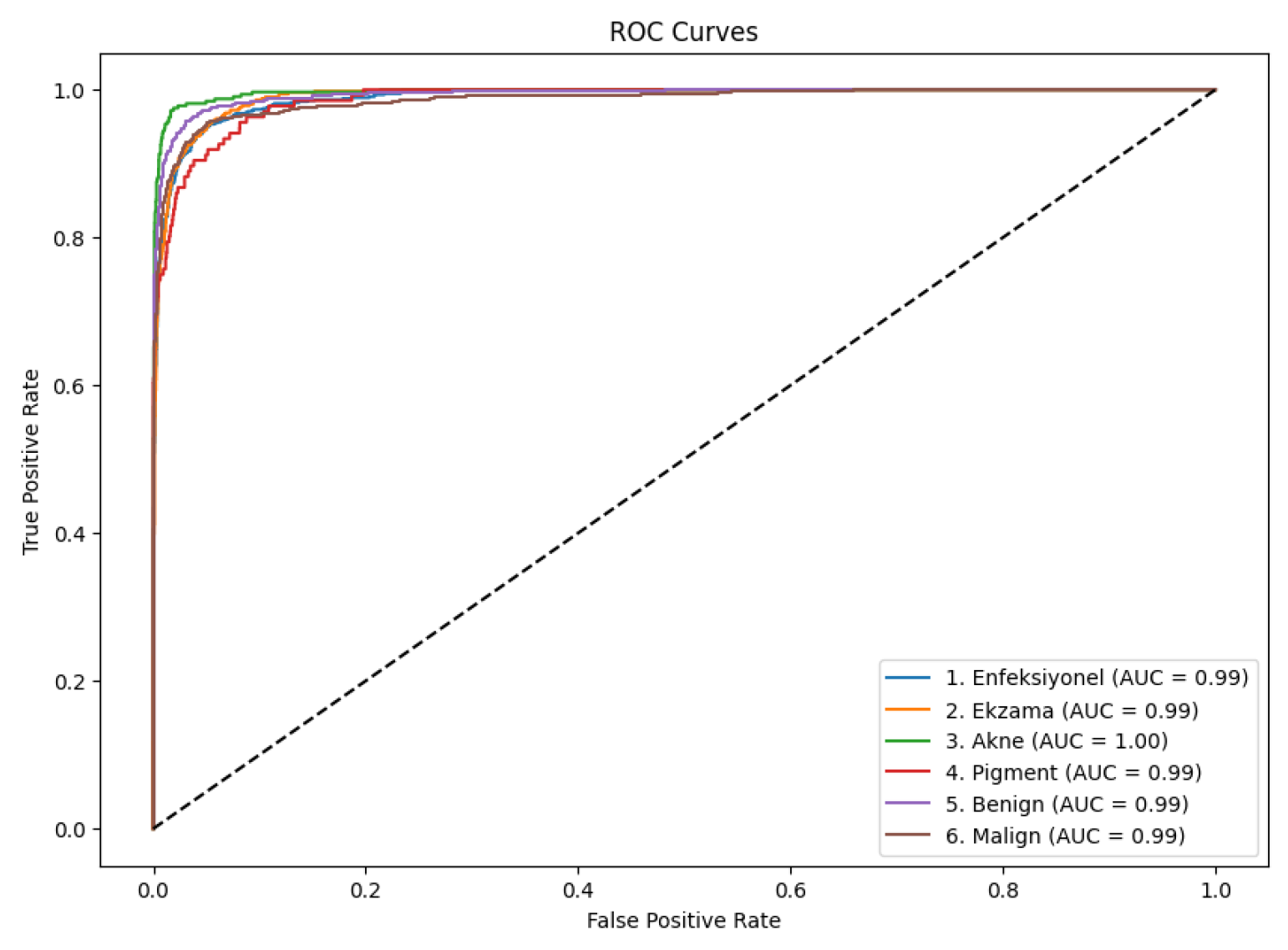

4.4. ROC Curve

Figure 4 presents the ROC curves for all six classes, demonstrating the model’s discriminative capability across different classification thresholds.

ROC curves for each disease category with corresponding AUC values.

All six classes demonstrate excellent ROC performance with AUC values that ranges from 0.99 to 1.00. The Akne class achieves a perfect AUC of 1.00, indicating outstanding discriminative capability. Even the Pigment class, which shows lower precision and recall values, maintains a high AUC of 0.99, suggesting that the model’s confidence scores are well-calibrated for this class despite classification challenges.

5. Results

Our results shows the effectiveness of the EfficientNetB4 architecture for multiclass skin disease classification. The model achieves high overall accuracy and maintains strong performance across most disease categories. However, several observations and limitations warrant discussion.

The superior performance on the Benign class (F1-score of 0.96) can get from the to two factors: the larger number of training samples and potentially more distinctive visual characteristics. Conversely, the Pigment class displays the lowest performance metrics (F1-score of 0.79), which may be due to its smaller sample size (136 test instances) and greater visual similarity to other conditions, particularly Enfeksiyonel and Malign.

The confusion between certain disease pairs, such as Ekzama and Enfeksiyonel, reflects real-world diagnostic challenges faced by dermatologists. These conditions can present with similar morphological patterns, making them difficult to distinguish even for human experts. The model’s ability to maintain high ROC AUC values despite these challenges suggests that it successfully captures subtle discriminative features.

EfficientNetB4’s compound scaling approach appears to contribute significantly to the model’s performance. By optimally balancing network width, depth, and input resolution, the architecture efficiently extracts hierarchical features from skin images at multiple scales. This capability is particularly valuable for dermatological image analysis, where relevant features may exist at various scales.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the dataset exhibits class imbalance, with the number of samples varying substantially across categories. Although we employed data augmentation to mitigate this issue, more balanced representation would likely improve performance for underrepresented classes like Pigment. Second, the model’s training convergence pattern suggests some degree of overfitting despite regularization efforts. Additional regularization techniques or a larger, more diverse dataset could address this limitation.

Clinically, it is especially crucial to distinguish benign from malignant disorders. With rather few misclassifications between these categories, the model shows great performance in this important dis-tension. Still, the 52 cases of Malign misclassified as Benign point to possible false negatives with major clinical consequences, so underscoring the need of more improvement.

For clinical decision support, the high AUC values across all classes show that the model generates well calibrated probability outputs. These confidence scores could be quite useful for doctors guiding additional diagnostic tests, giving cases with unclear classifications top priority.

6. Comparative Analysis

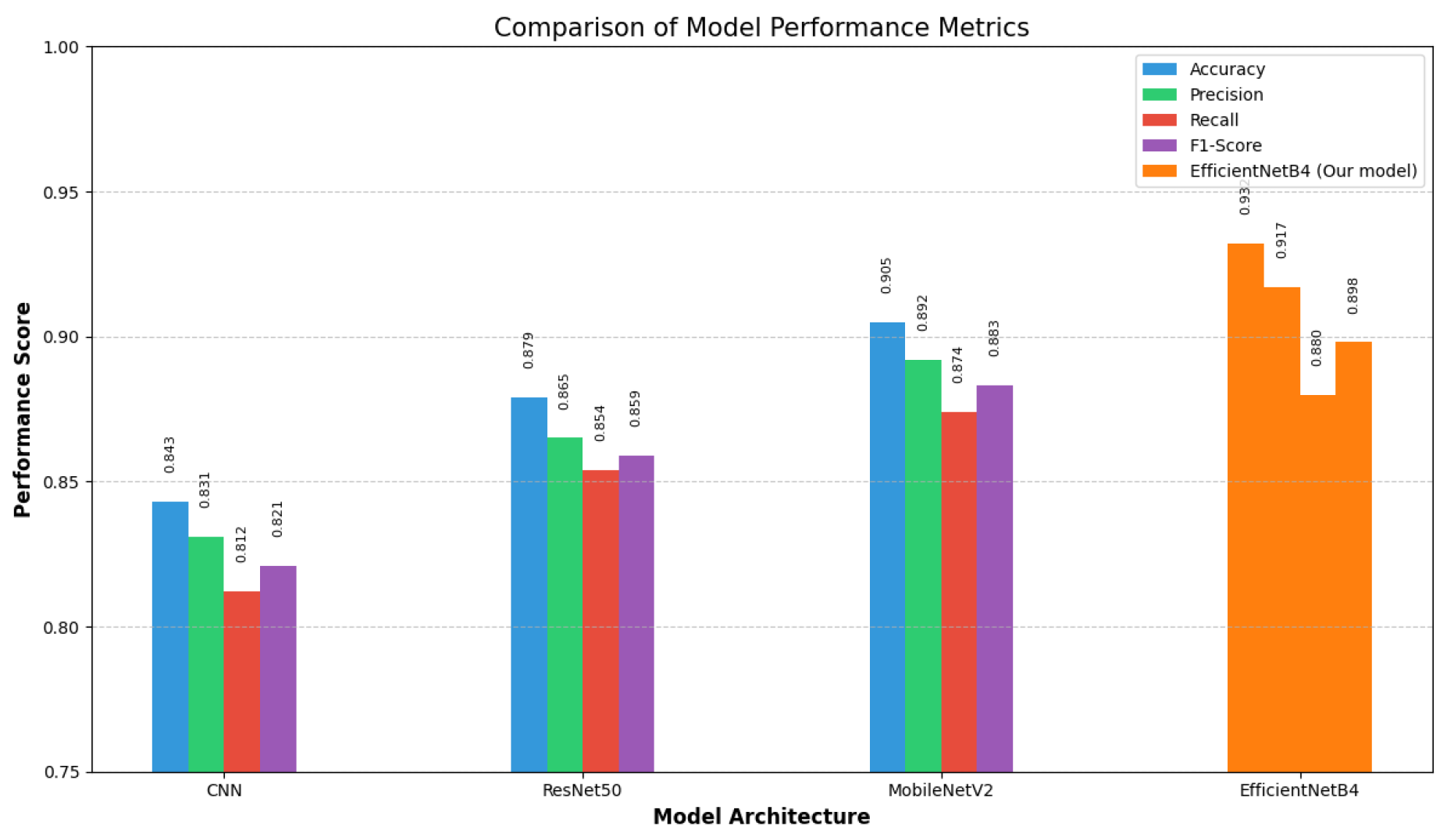

To contextualize our results, we conducted a comparative analysis of EfficientNetB4 against other prominent CNN architectures commonly used for skin disease classification.

Figure 5 presents a comparison of key performance metrics across four different models.

As evident from

Figure 6, our implementation of EfficientNetB4 consistently outperforms other architectures across all evaluation metrics. With an accuracy of 93.2%, EfficientNetB4 significantly surpasses the performance of MobileNetV2 (90.5%), ResNet50 (87.9%), and the baseline CNN model (84.3%).

The baseline CNN architecture, while providing reasonable performance, lacks the sophisticated architectural elements needed to capture the complex patterns present in dermatological images. ResNet50, despite its deep architecture with residual connections that help mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, still falls short compared to more recent architectures.

MobileNetV2 demonstrates competitive performance with its inverted residual structure and linear bottlenecks, offering a good balance between model size and classification capability. However, it still lags behind EfficientNetB4 by approximately 2.7 percentage points in accuracy and similar margins in precision, recall, and F1-score.

The superior performance of EfficientNetB4 can be attributed to its compound scaling approach, which optimally balances network width, depth, and resolution. This balanced scaling strategy is particularly advantageous for dermatological images where diagnostically relevant features exist at multiple scales and levels of abstraction.

Notably, EfficientNetB4 achieves the highest precision ( 91.7%) and F1-score (89.8%), indicating its reliability in both minimizing false positives and maintaining a good balance between precision and recall. This characteristic is particularly important in medical diagnostic applications where both false positives and false negatives carry significant consequences.

The performance difference becomes even more pronounced when examining challenging classes like Pigment, where EfficientNetB4’s sophisticated feature extraction capabilities allow it to identify subtle discriminative patterns that other models might miss.

7. Conclusions

This study introduced a deep learning technique for automated skin disease classification using the EfficientNetB4 architecture. Our model showed good performance metrics, even for challenging disease categories, with an overall accuracy of 93.2% across six skin conditions. The results demonstrate how deep learning can enhance clinical judgment and assist in dermatological diagnosis. The EfficientNetB4 architecture was effective for this task because it balanced computational efficiency and classification performance. It is particularly noteworthy that the model is very reliable in distinguishing between benign and malignant conditions, considering the clinical significance of this distinction. Numerous research avenues are made possible by our findings. First, addressing the class gap with strategies like stratified sampling or more advanced data augmentation may help improve performance for underrepresented classes. Second, investigating ensemble approaches that integrate several complementary models may improve overall robustness and accuracy. Third, by incorporating attention mechanisms, the model may be able to concentrate on the areas of skin lesion images that are the most discriminative.

From an application standpoint, implementing such models in clinical settings necessitates ongoing validation with a variety of patient populations, interpretability for healthcare professionals, and careful consideration of integration with current workflows. Creating mobile applications with simplified versions of the model could also increase access to dermatological knowledge in environments with limited resources.

To sum up, our research adds to the increasing amount of data proving AI-assisted dermatology and shows how deep learning can be used to automate the diagnosis of skin conditions. Strong performance across a range of skin conditions indicates promising prospects for computer-aided diagnosis in dermatological practice, even though more improvement and validation are required before clinical deployment.

References

- Hay, R. J.; et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2014, 134, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenziano, G.; et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: Results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2003, 48, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. C. F. Codella et al., “Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: A challenge at the 2017 International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC),” in IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018), 2018, pp. 168-172.

- G. Litjens et al., “A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis,” Medical Image Analysis, vol. 42, pp. 60-88, 2017.

- M. Tan and Q. V. Le, “EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks,” in Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2019, pp. 6105-6114.

- L. Yu et al., “Automated melanoma recognition in dermoscopy images via very deep residual networks,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 994-1004, 2017.

- A. Esteva et al., “Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks,” Nature, vol. 542, no. 7639, pp. 115-118, 2017.

- K. He, X. K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Deep residual learning for image recognition,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016, pp. 770-778.

- K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman, “Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition,” in International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2015.

- A. G. Howard et al. MobileNets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv, 2017. arXiv:1704.04861.

- H. C. Shin et al., “Deep convolutional neural networks for computer-aided detection: CNN architectures, dataset characteristics and transfer learning,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 1285-1298, 2016.

- J. Hu, L. J. Hu, L. Shen, and G. Sun, “Squeeze-and-excitation networks,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2018, pp. 7132-7141.

- P. Tschandl, C. P. Tschandl, C. Rosendahl, and H. Kittler, “The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions,” Scientific Data, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1-9, 2018.

- N. Gessert, T. Sentker, F. Madesta, R. Schmitz, H. Kniep, I. Baltruschat, R.Werner, and A. Schlaefer. Skin lesion diagnosis using ensembles, unscaled multi-crop evaluation and loss weighting. arXiv, 2018. arXiv:1808.01694.

- X. He, K. X. He, K. Zhao, and X. Chu, “AutoML: A survey of the state-of-the-art,” Knowledge-Based Systems, vol. 212, p. 106622, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).