1. Introduction

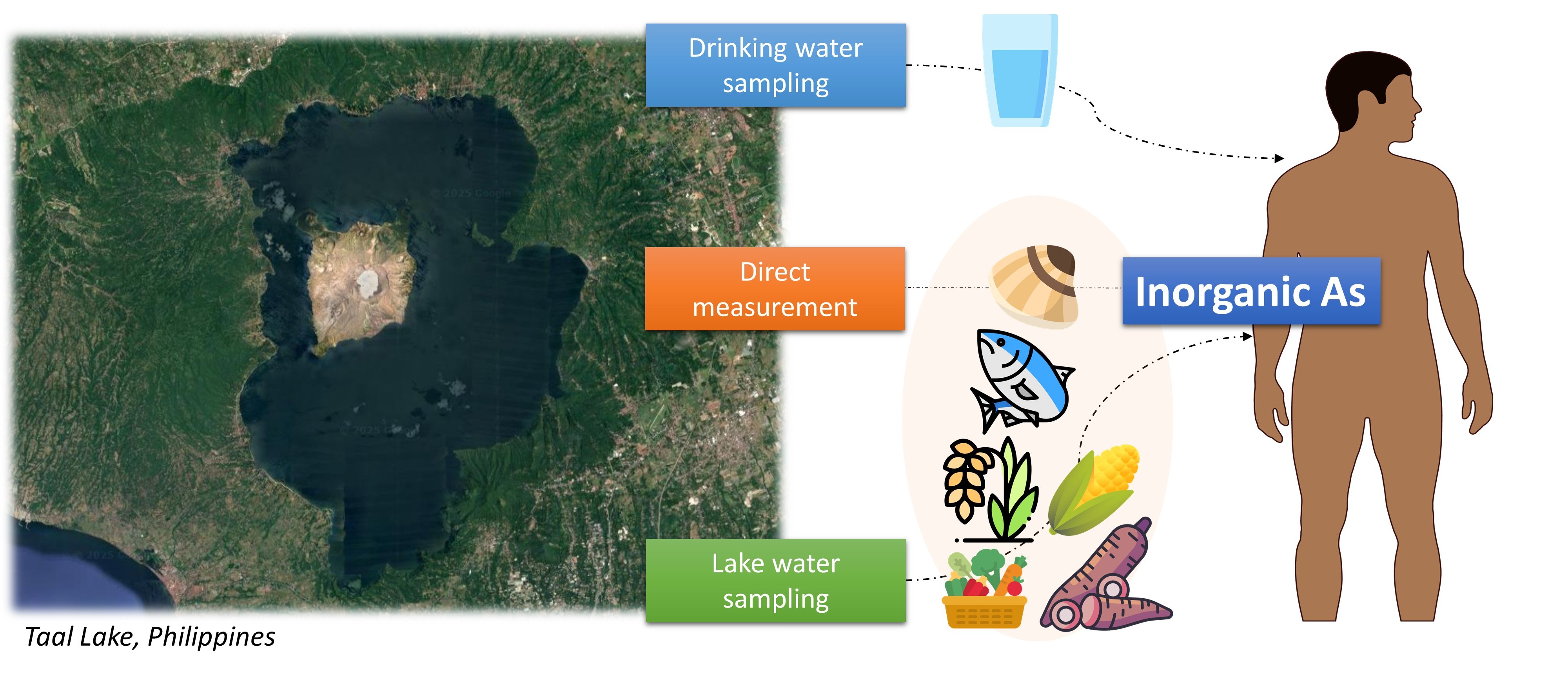

Volcanic eruptions represent significant environmental hazards, capable of mobilizing naturally occurring toxic elements, such as arsenic, into surrounding ecosystems through multiple pathways (Ermolin et al., 2018). Volcanic deposits, particularly fine ash rich in glass shards, are recognized globally as important geogenic sources of arsenic in water, soil, and sediments (Bia et al., 2022; Murray et al., 2023). During and after eruptions, arsenic dispersed through volcanic ash fallout can contaminate water supplies and agricultural soils, eventually entering the food chain via bioaccumulation in crops and aquatic organisms (J. Bundschuh et al., 2021; Witham et al., 2005). These contamination processes pose substantial public health risks, particularly in densely populated areas adjacent to active volcanic systems where communities depend heavily on local water and food resources.

The 2020 Taal Volcano eruption in Batangas, Philippines, exemplified these environmental threats, with the explosive event dispersing volcanic materials across surrounding communities. Our previous investigation documented elevated arsenic concentrations in groundwater sources in communities surrounding Taal Volcano, highlighting the immediate post-eruption contamination of drinking water resources (Apostol et al., 2022). However, the broader implications of this volcanic event extend beyond water contamination, as arsenic mobilized from volcanic deposits can infiltrate agricultural systems and aquatic environments, potentially accumulating in staple foods and creating sustained exposure pathways for affected populations (Rodriguez-Hernandez et al., 2022).

Rice, a dietary staple throughout Southeast Asia including the Philippines, is particularly efficient at accumulating arsenic, with concentrations typically ten times higher than other cereal crops due to its cultivation under flooded conditions that favor arsenic mobilization and uptake through silicon transporters (Menon et al., 2022; Sarwar et al., 2021). In arsenic-affected regions, rice consumption has been identified as a major dietary source of inorganic arsenic (iAs) exposure, contributing substantially to cardiovascular disease and cancer risk even in populations with relatively low drinking water arsenic concentrations (Nachman et al., 2017; Rokonuzzaman et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2020). Similarly, aquatic foods harvested from contaminated water bodies can contribute significantly to aggregate arsenic exposure, particularly in communities with high seafood consumption patterns characteristic of Southeast Asian populations (Kerdthep et al., 2009; Koesmawati & Arifin, 2015; McCarty et al., 2011; Ngoc et al., 2020). Given that iAs is a Group 1 human carcinogen linked to cancers of the skin, lung, and bladder (Schuhmacher–Wolz et al., 2009; Straif et al., 2009) , as well as non-cancer outcomes including neurodevelopmental impairment and peripheral neuropathy (Hong et al., 2014; Naujokas et al., 2013; Rahman et al., 2009), comprehensive exposure assessments are essential in volcanically impacted regions. However, measured iAs data across a wide range of food crops are typically limited, constraining the accuracy of exposure and risk estimates.

To address this gap, we conducted a probabilistic health risk assessment quantifying aggregate iAs exposure among Batangas residents following the Taal eruption. Using arsenic concentrations in groundwater, clams, and major food groups combined with population-specific dietary intake patterns, we estimated both non-cancer and lifetime cancer risks. Sensitivity analyses identified dominant exposure contributors and vulnerable demographic subpopulations. This integrated assessment provides critical evidence to guide public health interventions, food safety management, and risk communication for communities affected by volcanic arsenic contamination in the Philippines and other volcanically active regions worldwide.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Herein, we conducted a probabilistic risk assessment to characterize the aggregate exposure and health risks associated with inorganic arsenic (iAs) among the Filipino population residing within Taal Volcano Protected Landscape (TVPL) in Batangas, Philippines, following the Taal Volcano eruption. The assessment focused on the immediate to medium-term post-eruption period (2020-2022) to capture acute contamination dynamics while recognizing that volcanic arsenic mobilization may persist for years or decades following major eruptive events. This temporal scope is critical for understanding early exposure patterns and establishing baseline risk estimates for ongoing surveillance programs in volcanic regions.

Both dietary and drinking water exposure pathways were considered to reflect post-eruption environmental contamination. The assessment was based on a Monte Carlo simulation framework with 10,000 iterations to account for variability in arsenic concentrations, dietary consumption patterns, and body weight. Two exposure scenarios were modeled to represent lower-bound (LB) and upper-bound (UB) conditions, corresponding to different assumptions regarding the proportion of bioavailable iAs in terrestrial crops (0.5 and 0.9, respectively), thereby capturing a plausible range of population risk.

2.2. Environmental Concentrations of Arsenic in the Taal Lake Region

2.2.1. Total Arsenic Levels in Drinking Water Samples

The arsenic concentrations in drinking water used for exposure modeling and risk assessment were obtained from a previously published field study (Apostol et al., 2022) that assessed arsenic levels in groundwater sources across selected communities surrounding Taal Volcano, Batangas Province, Philippines. In brief, a total of 72 drinking water samples were analyzed from 26 wells in 11 municipalities and one city, collected in 2020 (n=32) and 2021 (n=41). Sampling locations included deep wells (n = 13), shallow wells (n = 4), protected springs (n = 1), and communal waterworks systems (Level III, n = 8), reflecting typical drinking water sources across the region. The sampled wells were geospatially distributed within the 7 km, 10 km, and 14 km volcanic danger zones defined by the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS), as well as areas beyond this perimeter. The sample collection protocol, sample pretreatment, and determination of total arsenic levels in drinking water are detailed elsewhere (Apostol et al., 2022). It is important to recognize that arsenic concentrations in groundwater may vary temporally following volcanic activity, with mobilization often enhanced during rainy seasons and concentration effects possible during dry periods (Solis et al., 2020). Similar seasonal and post-eruptive variability has been reported in other volcanic regions (Jochen Bundschuh et al., 2021; Witham et al., 2005). Incorporating seasonal monitoring into future field campaigns will be essential for capturing these dynamics and supporting adaptive, evidence-based risk management strategies.

2.2.2. Total Arsenic Levels in Soil and Taal Lake Water

Total arsenic concentrations in soil and Taal Lake water were obtained from post-eruption environmental monitoring conducted after the January 2020 Taal Volcano eruption (Banta & Salibay, 2023). In brief, surface soil samples (depth: 0–10 cm) were collected from agricultural sites in Cuenca, Talisay, and Tagaytay City, which were affected by volcanic ashfall. At each location, three composite samples were air-dried, homogenized, and analyzed using hydride-generation atomic absorption spectrophotometry (HG-AAS). Total arsenic concentrations ranged from 1.92 to 7.91 mg/kg, with the highest values reported in Talisay, likely due to its proximity to the volcano. Lake water samples were collected from three nearshore sites in Agoncillo, Cuenca, and Talisay (~500 m from shore), stored in sterile containers, and analyzed the same day using HG-AAS. Total arsenic concentrations ranged from 0.005 to 0.0097 mg/L, below the national Class C water quality guideline of 0.02 mg/L. These measurements served as background values for assessing non-drinking water arsenic exposure near the volcano.

2.2.3. Simulation of Inorganic Arsenic (iAs) Concentrations in High-Risk Foods

2.2.3.1. Food Selection Rationale

Fish, clams, rice, corn, vegetables, and root crops were selected as representative food groups based on three criteria: (1) dietary relevance in Batangas and broader Philippine contexts, where rice provides 35-40% of total caloric intake and fish contributes significantly to protein consumption; (2) plausible biogeochemical exposure pathways of arsenic from volcanic contamination; and (3) availability of consumption data from national nutrition surveys. Fish and clams integrate lake and groundwater inputs across food webs and represent critical protein sources for communities dependent on Taal Lake resources, particularly among lower-income households with limited access to alternative protein sources. Rice cultivation under flooded conditions promotes arsenic uptake through silicon transporters, making it a globally recognized accumulator. Vegetables and root crops can accumulate arsenic from contaminated soils and irrigation water. Corn was included as a secondary staple crop important in rural Philippine diets. This food group selection enables comparison with arsenic exposure assessments from other volcanic regions including Indonesia (Mount Merapi), Japan (multiple volcanic areas), and Latin America.

2.2.3.2. Aquatic Foods

iAs concentrations in fish (mg/kg) were estimated by multiplying lake water As concentrations (mg/L) with a bioaccumulation factor (BAF) sampled from a uniform distribution UBAF_fish [minimum = 10.3, maximum = 22] L·kg⁻¹(Kar et al., 2011). Seasonal effects were accounted for by applying a dry-season conversion factor (CF) sampled from a truncated normal distribution TNCFdry [mean = 6.71, standard deviation = 4.50, minimum = 2.21, maximum = 13.66], reflecting increased arsenic concentrations in fish during drier months (Molina & Kada, 2014). A further fraction of total As was assumed to be inorganic based on a literature-derived multiplier UTotalAs to iAs [minimum = 0.117, maximum = 0.142] (Kar et al., 2011).

For clams, total As concentrations were derived from empirical measurements in Corbicula fluminea samples collected from three active harvesting sites in Taal Lake, including Saluyan, Calawit, and Binintiang Munti (Azores et al., 2025). Two morphotypes (white and purple) were examined to account for potential inter-morph differences in metal accumulation. Clam specimens were obtained by traditional hand-grabbing methods. The soft tissues were air-dried for approximately 240 hours and oven-dried for 24 hours at 55 °C, then homogenized using an agate mortar and pestle to prevent metallic contamination. Dried and pulverized tissues were analyzed for elemental composition using a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (p-XRF; Bruker S1 Titan, GeoExploration mode, 90 s elapsed time). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, and results were expressed as mean dry-weight concentrations (mg/kg dw).

The p-XRF system was calibrated using oxide-phase standards and fitted with a 4 µm Prolene thin film to minimize matrix interference. Quality control included replicate analysis and internal consistency checks between morphs and sites. The mean total As concentrations across all sites ranged between 5.0 and 6.3 mg/kg dry weight, consistent with post-eruption contamination levels (Supplemental File S1).

Accordingly, total As concentrations in clams were simulated using a truncated normal distribution TNtotalAs_clam (mean = 5.67, standard deviation = 3, minimum = 0) and converted to iAs using the same UTotalAs to iAs factor applied to fish. This empirical parameterization reflects the contamination baseline of Taal Lake clams in the post-eruption period, providing site-specific realism for probabilistic exposure modeling.

2.2.3.3. Terrestrial CROPS

Total As concentrations in crops (µg/g) were estimated by multiplying soil As levels (see

Section 2.2.2) with crop-specific transfer factors drawn from literature-based ranges: rice (U

TFrice [minimum = 0.006, maximum = 0.036]), corn (U

TFcorn [minimum = 0.005, maximum = 0.027]), vegetables (U

TFveg [minimum = 0.0003, maximum = 0.028]), and root crops (U

TFrootcrops [minimum = 0.0028, maximum = 0.007])(Huang et al., 2006; Rosas-Castor et al., 2014). To account for variability in arsenic speciation and plant uptake, these total As concentrations were further multiplied by a fixed inorganic fraction—0.9 for the UB scenario and 0.5 for the LB scenario.

2.3. Exposure Factors and Population Parameters

2.3.1. Drinking Water Intake

Daily drinking water consumption was set at 1.79 liters per person, based on the 2018-2019 Philippine Nutrition Facts and Figures: Food Consumption Survey conducted by the Department of Science and Technology–Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST-FNRI)(FNRI, 2022). According to the survey, adults aged 19–59 years reported the highest average water intake among population groups, with a mean of 1,791 mL/day. This value was adopted as the central estimate for the present assessment to represent typical hydration patterns among adults in Batangas. Due to the absence of reported variability (e.g., standard deviation, SD) in the source report, drinking water intake was treated as a fixed parameter in the aggregate exposure model to ensure conservative dose estimation.

2.3.2. Food Consumption Data

Daily intake values (g/day) for six major food categories: fish, rice, corn, vegetables, and root crops, were simulated using truncated normal distributions to capture inter-individual variability while enforcing biologically plausible bounds. Mean and standard deviation values were derived from the Philippine Nutrition Facts and Figures: 2021 Expanded National Nutrition Survey (ENNS), which reported the daily consumption among adults as follows: fish and fish meat (mean= 59 g/day, SD=488.8 g/day); rice (mean= 263 g/day, SD=872.8 g/day); corn (mean=6 g/day; SD=541.2 g/day); vegetables (mean=58 g/day, SD=680.83 g/day); root crops (mean= 7 g/day; SD= 104.7 g/day)(FNRI, 2024). The daily consumption of clam was approximated using data for “Crustaceans and molluscs” from 2023 Philippine Fisheries Profile (mean= 8.5 g/day; SD=70.4 g/day)(BFAR, 2024). Lower bounds were set at 0 g/day, and upper bounds were capped at the mean + 3 SD to reflect conservative high-intake conditions. All distributions were implemented using the “rtruncnorm()” function in R, assuming normality with truncation at both ends. These probabilistic inputs were incorporated into a Monte Carlo simulation framework to estimate total and food-specific iAs intakes across the simulated population.

Table 1.

Daily consumption parameters used in the Monte Carlo simulation for inorganic arsenic (iAs) exposure assessment among the Batangas population. Mean intake and standard deviation (SD) values were derived from national dietary references, while the range (minimum–maximum) was set as 0 to 10 times the mean for a conservative exposure scenario. Drinking water intake was fixed at 1.29 L/day based on national fluid-intake data.

Table 1.

Daily consumption parameters used in the Monte Carlo simulation for inorganic arsenic (iAs) exposure assessment among the Batangas population. Mean intake and standard deviation (SD) values were derived from national dietary references, while the range (minimum–maximum) was set as 0 to 10 times the mean for a conservative exposure scenario. Drinking water intake was fixed at 1.29 L/day based on national fluid-intake data.

| iAs exposure source |

Mean (g/day) |

SD |

Range (g/day) |

| Fish |

85.4 |

42.7 |

0–854 |

| Clam |

8.5 |

4.25 |

0–85 |

| Rice |

325.5 |

162.8 |

0–3255 |

| Corn |

18.8 |

9.4 |

0–188 |

| Vegetables |

58.0 |

29.0 |

0–580 |

| Root crops |

22.6 |

11.3 |

0–226 |

| Drinking water |

1.791 (L/day) |

– |

Fixed |

2.3.3. Demographical Parameters

To incorporate population variability in physiological parameters relevant to dose normalization, we modeled sex distribution, body weight, and height for 10,000 simulated individuals using demographic data and literature-based assumptions. Sex distribution was assigned based on the 2020 Philippine Census, with a population-proportional split of 50.6% male and 49.4% female (Authority, 2022). Body weight and height were modeled using sex-specific truncated normal distributions informed by Filipino anthropometric data (Garcia et al., 2020) and supplemented by comparable regional data (e.g., Taiwanese population studies). All anthropometric distributions were generated using the rtruncnorm() function in R, ensuring simulated values remained within biologically reasonable bounds (

Table 2). These parameters were subsequently used to compute individual-level intake doses (µg/kg-day) by normalizing estimated inorganic arsenic intakes to body weight.

2.4. Aggregate Exposure Modeling of iAs

Aggregate exposure to iAs among the Batangas population was estimated by integrating exposure from dietary intake (fish, clams, rice, corn, vegetables, and root crops) and drinking water ingestion. The assessment followed a probabilistic framework using Monte Carlo simulation (10,000 iterations) to propagate variability in environmental concentrations, consumption patterns, and body weight. For each simulated individual, the daily intake of iAs (µg/kg-day) was computed as the sum of contributions from all exposure media:

where

Ci is the iAs concentration in medium

i (µg/g or µg/L, see

Section 2.2), and IR

i is the corresponding individual consumption rate (g/day or L/day, see

Section 2.3). BW (kg) represents the body weight for the simulated individuals. Two parallel exposure scenarios were generated to represent lower-bound and upper-bound conditions, capturing the uncertainty in iAs bioavailability from terrestrial foods.

2.5. Sensitivity Analysis

A global sensitivity analysis was performed to identify the key parameters influencing daily iAs intake in the simulated population. Two complementary methods, Standardized Regression Coefficients (SRC) and Partial Rank Correlation Coefficients (PRCC), were applied using 10,000 Monte Carlo iterations. A total of 18 input variables were evaluated, including environmental total As concentrations (i.e., lake water, soil, and drinking water), bioaccumulation or transfer factors, the dry-season conversion factor, daily food consumption rates, and body weight. For the SRC analysis, standardized inputs were fitted in a multiple linear regression model with iAs intake (µg/kg-day) as the dependent variable to estimate linear effects. For the PRCC analysis, rank-transformed inputs and outputs were analyzed using the ppcor package (version 1.1, Spearman method) to capture monotonic and non-linear relationships while accounting for inter-variable dependence. Results from both methods were visualized as tornado plots, with larger absolute coefficients indicating greater influence on exposure variability. Parameters with p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The combined SRC–PRCC framework provided a robust and interpretable assessment of input sensitivity, suitable for probabilistic exposure models with correlated and uncertain parameters.

2.6. Risk Characterization

Health risks associated with iAs exposure were characterized by estimating both non-cancer and cancer risk metrics based on the simulated daily exposure doses (µg/kg-day). For non-cancer effects, the hazard quotient (HQ) was calculated for each iteration as:

where EiAs is the estimated daily iAs exposure dose, and RfD is the oral reference dose for inorganic arsenic (0.06 mg/kg-day) established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA, 2025). An HQ greater than 1 indicates a potential for adverse health effects.

For cancer risk, lifetime excess cancer risk (ECR) was computed using:

where CSF is the oral cancer slope factor for inorganic arsenic (0.032 (mg/kg-day)⁻¹). Cumulative probability distributions of HQ and ECR were generated to evaluate population-level variability and risk exceedance probabilities.

2.7. Data Analysis and Visualization

All analyses were performed in R (version 4.4.0) and RStudio (2023.06.01 Build 421, Posit Software, PBC) using packages dplyr (version 2.5.1), truncnorm (version 1.0-9), ppcor (version 1.1), and ggplot2 (version 4.0.0). The boxplots, pie chart, violin plots, cumulative density plots, and scatter plots were generated using GraphPad Prism 9 (version 9.5.1).

3. Results

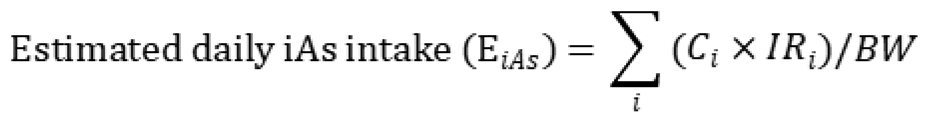

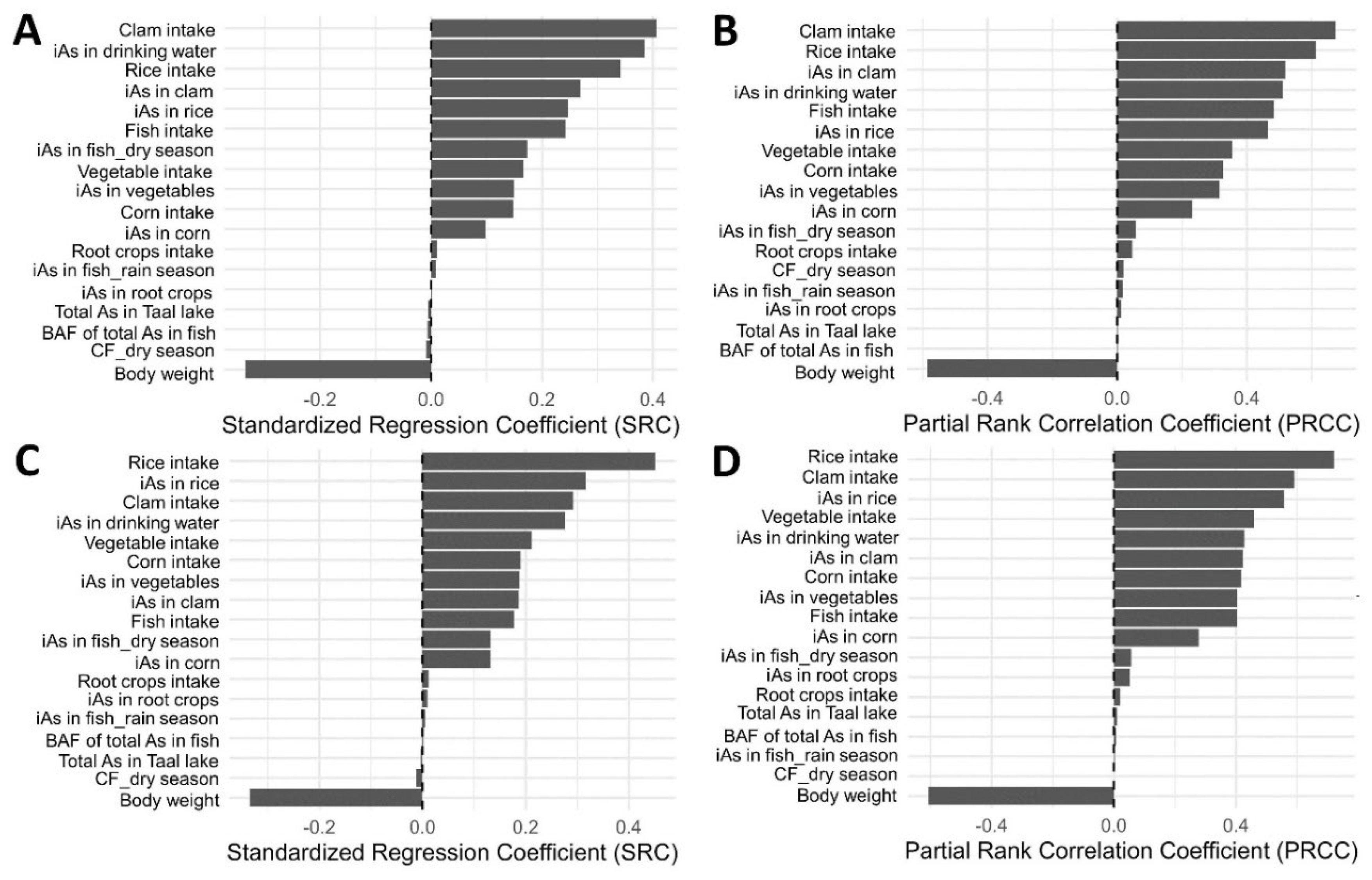

3.1. Simulated Concentrations of iAs in Fish and Terrestrial Crops

iAs concentrations across fish and terrestrial crops were modeled based on the total As levels in soil and

Taal lake water (

Figure 1). Simulated iAs level in fish was 0.016 ± 0.005 μg/g during rainy season and 0.12 ± 0.06 μg/g during dry season. Among terrestrial crops, rice exhibited the highest iAs concentration, followed by corn, vegetables, and root crops. Under the UB scenario (assuming 90% of total arsenic as iAs), concentrations across crops ranged from 0.02–0.12 µg/g, whereas under the LB scenario (assuming 50% iAs), they ranged from 0.007–0.06 µg/g.

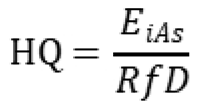

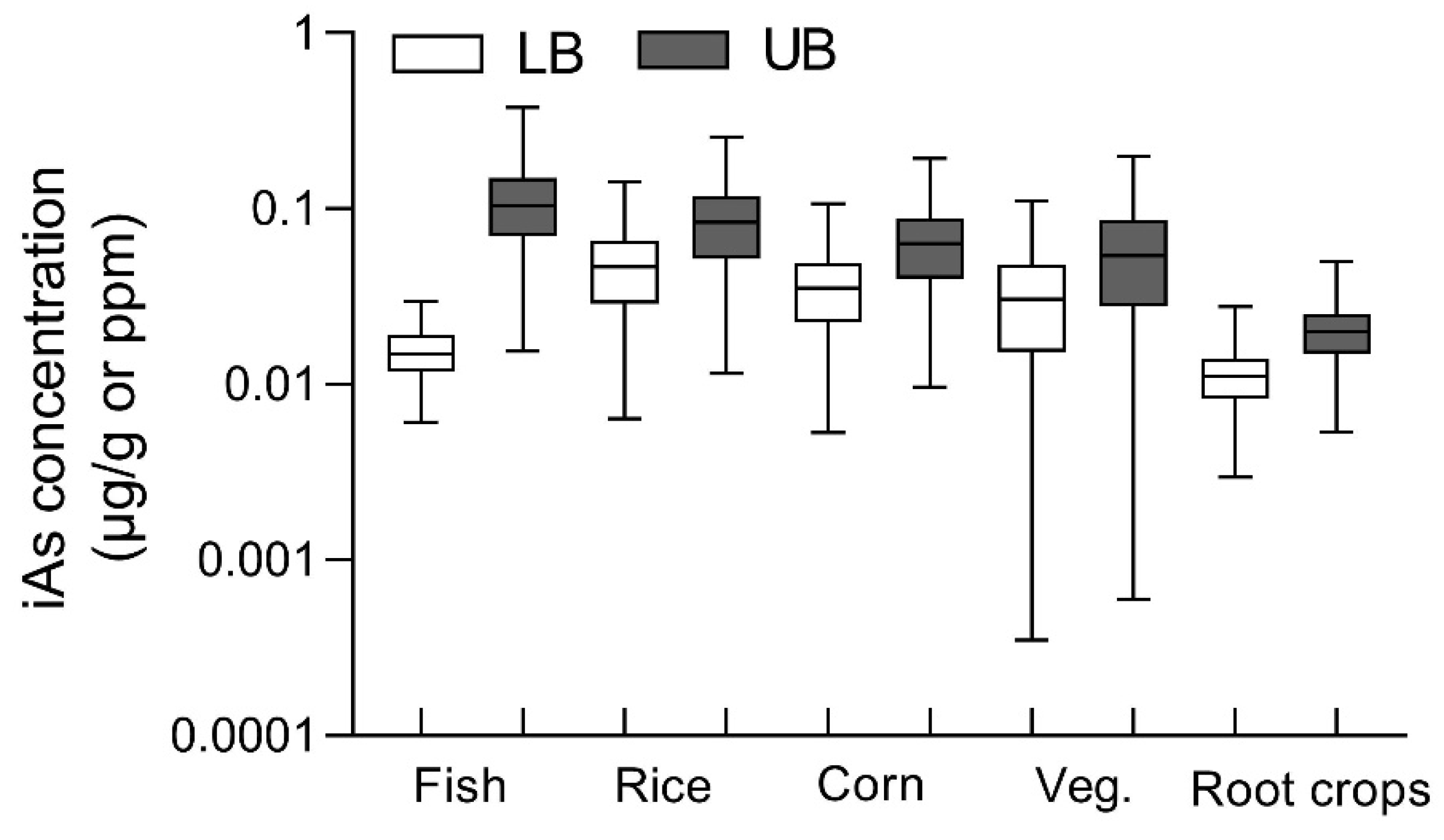

3.2. Contribution of Individual Exposure Pathways to iAs

The pie charts illustrate the relative contributions of different dietary and drinking water pathways to iAs exposure among residents of Batangas (

Figure 2). Under the LB scenario (

Figure 2A), clams represented the largest contributor to total iAs dose (26.2%), followed by rice (22.7%), fish (15.8%), drinking water (14.2%), vegetables (11.1%), corn (9.5%), and root crops (0.6%). Under the UB scenario (

Figure 2B), rice became the dominant contributor (30.4%), followed by clams (19.3%), vegetables (14.4%), corn (12.7%), fish (11.8%), drinking water (10.7%), and root crops (0.8%). Across both scenarios, aquatic foods (fish and clams) accounted for approximately 31–42% of total iAs intake, while terrestrial crops (rice, corn, vegetables, and root crops) contributed 44–58%. These results indicate that dietary sources, particularly rice and aquatic foods, remain the primary exposure pathways for residents of Batangas.

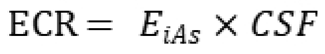

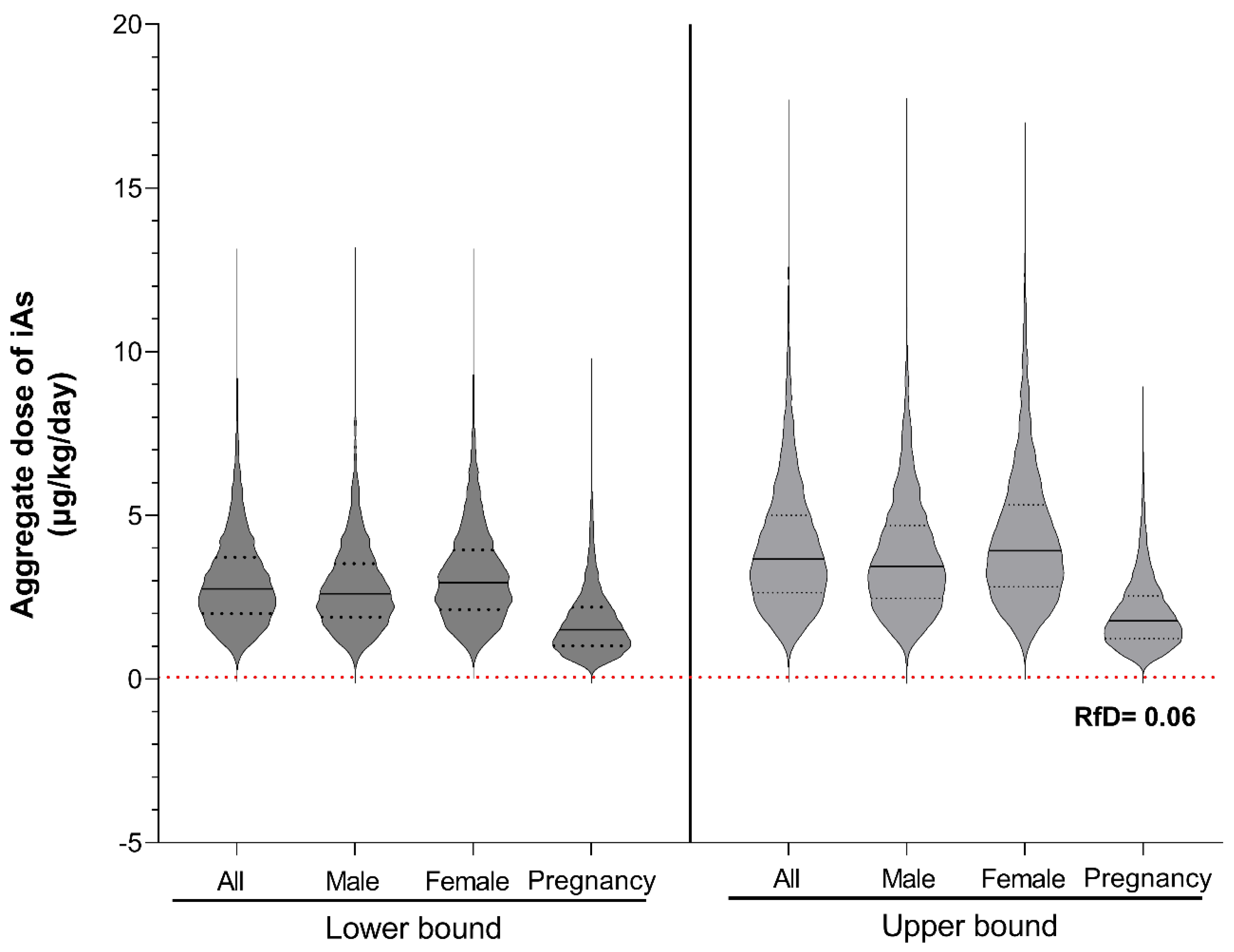

3.3. Aggregate Dose of iAs Under Lower- and Upper-Bound Exposure Scenarios for Residents in Batangas, Philippines

The aggregate daily doses of iAs across the Batangas population were successfully modeled using the Monte Carlo framework (

Figure 3), yielding population means ranging from 3.0 ± 1.4 µg/kg bw/day to 4.0 ± 2.0 µg/kg bw/day across all scenarios. Overall, females showed slightly higher central tendencies than males, with mean doses of 3.2 ± 1.5 µg/kg bw/day versus 2.8 ± 1.3 µg/kg bw/day under the LB scenario, and 4.3 ± 2.1 µg/kg bw/day versus 3.8 ± 1.8 µg/kg bw/day under the UB scenario. Pregnant women exhibited marginally lower aggregate iAs doses (LB: 1.8 ± 1.1 µg/kg bw/day; UB: 2.0±1.1µg/kg bw/day), although differences were not statistically significant as determined by one-way ANOVA.

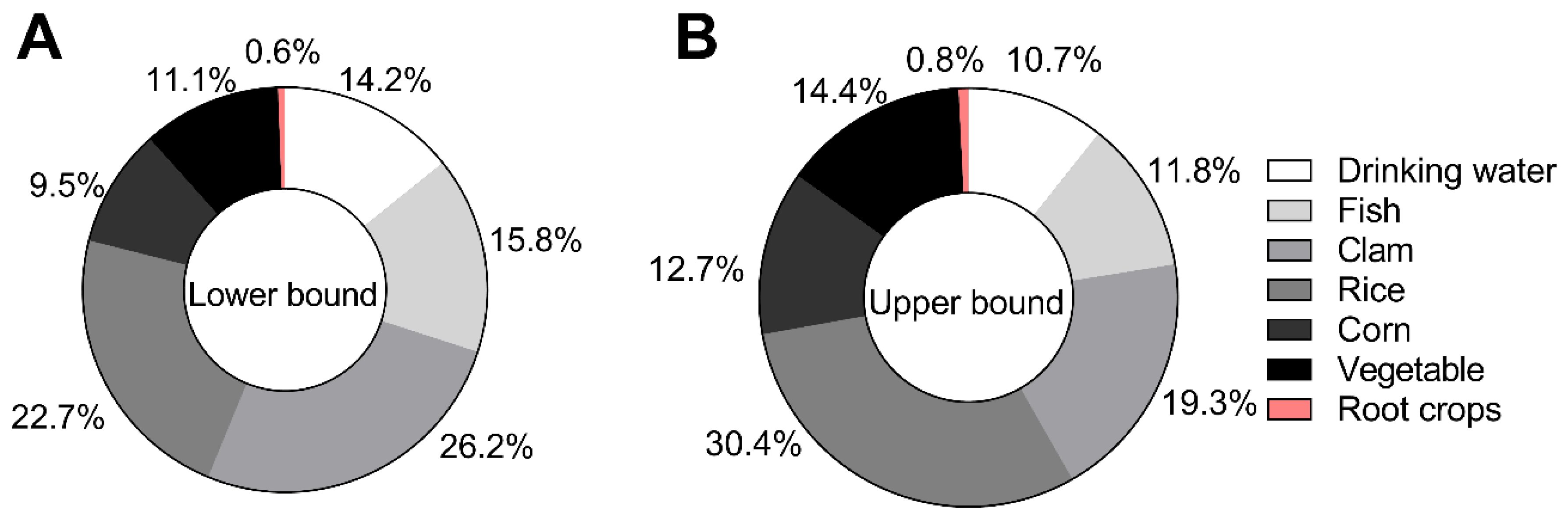

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Input Exposure Variables

A global sensitivity analysis was performed to identify the most influential parameters affecting the aggregate daily intake of iAs (

Figure 4). Standardized regression coefficients (SRC) and partial rank correlation coefficients (PRCC) were applied to evaluate model sensitivity under the LB and UB exposure scenarios, respectively.

Under the LB scenario, the SRC analysis identified 13 statistically significant parameters (

Figure 4A), where clam intake was the most influential parameter (+0.41), followed by iAs concentration in drinking water (+0.38), rice intake (+0.34), body weight (-0.33), iAs concentration in clams (+0.27), iAs in rice (+0.25), fish intake (+0.24), vegetable intake (+0.17), iAs in dry season fish (+0.17), corn intake (+0.15), iAs in vegetables (+0.15), iAs in corn (+0.10), and root crops intake (+0.01). The PRCC analysis identified 14 statistically significant parameters (

Figure 4B), where clam intake remains the most influential parameter (+0.67), followed by rice intake (+0.61), body weight (-0.59), iAs in clam (+0.52), iAs in drinking water (+0.51), fish intake (+0.48), iAs in rice (+0.46), vegetable intake (+0.36), corn intake (+0.33), iAs in vegetables (+0.32), iAs in corn (+0.23), iAs in dry season fish (+0.06), root crops intake (+0.05) and dry season conversion factor (+0.02).

Under the UB scenario, the SRC analysis identified 14 statistically significant parameters (

Figure 4C), where rice intake was the most influential parameter (+0.45), followed by body weight (-0.33), iAs in rice (+0.32), clam intake (+0.29), iAs in drinking water (+0.28), vegetable intake (+0.21), corn intake (+0.19), iAs in vegetables (+0.19), iAs in clam (+0.19), fish intake (+0.18), iAs in corn (+0.13), iAs in dry season fish (+0.13), root crops intake (+0.01), and iAs in root crops (+0.01). The PRCC analysis also identified 14 statistically significant parameters (

Figure 4D), where rice intake remains the most influential parameter (+0.72), followed by body weight (-0.61), clam intake (+0.59), iAs in rice (+0.56), vegetable intake (+0.46), iAs in drinking water (+0.43), iAs in clam (+0.42), corn intake (+0.42), iAs in vegetables (+0.40), fish intake (+0.40), iAs in corn (+0.28), iAs in dry season fish (+0.06), iAs in root crops (+0.05), and root crops intake (+0.02).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of key input variables influencing estimated inorganic arsenic (iAs) exposure. Panels show standardized regression coefficients (SRC; lower-bound scenario in A and upper-bound scenario in C) and partial rank correlation coefficients (PRCC; lower-bound in B and upper-bound in D).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of key input variables influencing estimated inorganic arsenic (iAs) exposure. Panels show standardized regression coefficients (SRC; lower-bound scenario in A and upper-bound scenario in C) and partial rank correlation coefficients (PRCC; lower-bound in B and upper-bound in D).

3.5. Risk Characterization

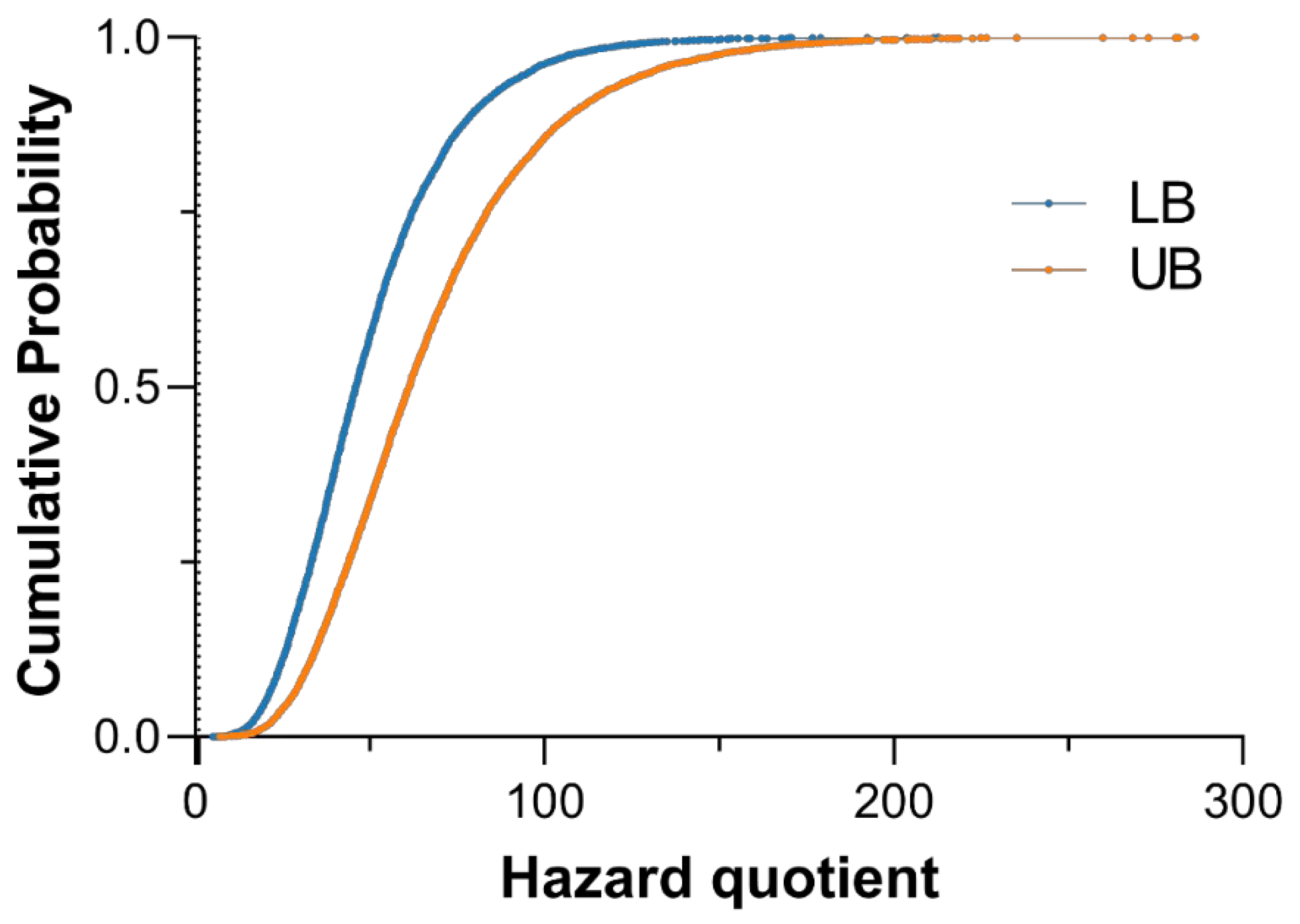

All simulated individuals exhibited HQs greater than 1 under both LB and UB exposure scenarios, indicating potential concern for non-cancer health effects associated with iAs exposure (

Figure 5). The maximum HQs reached 212.8 in the LB scenario and 286.1 in the UB scenario, showing that combined dietary and drinking water exposures substantially exceeded the U.S. EPA reference dose (0.06μg/kg/day).

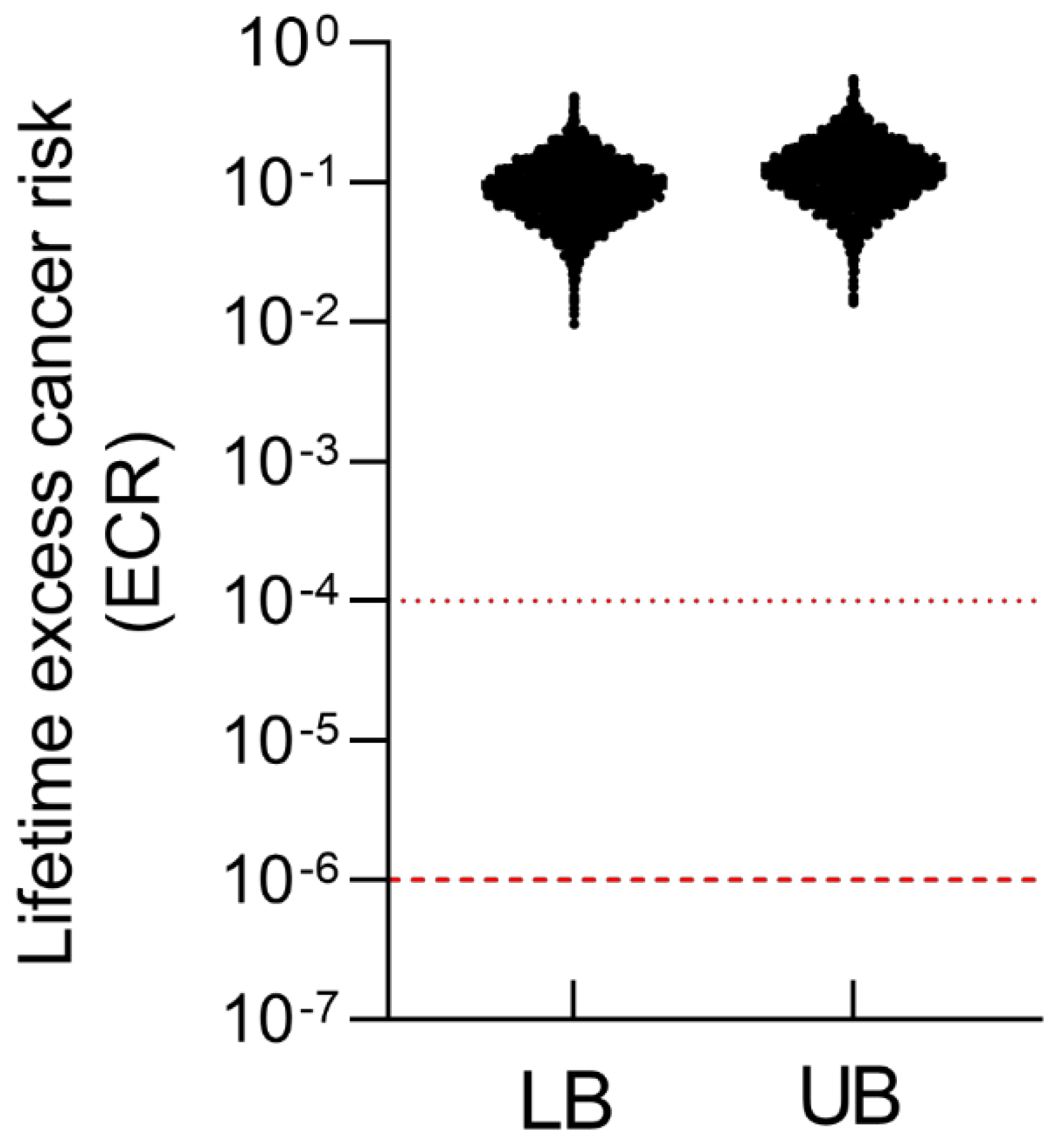

For cancer risk, ECRs were estimated using simulated aggregate iAs doses and the oral cancer slope factor (

Figure 6). All modeled individuals exceeded the acceptable benchmark of 10

-6 for the general population, with ECRs under both scenarios primarily distributed between 10

-2 and 1. These findings indicate a markedly elevated lifetime cancer risk among Batangas residents and underscore the need for continued monitoring and mitigation of iAs contamination in both aquatic and terrestrial food pathways.

4. Discussions

Volcanic activity can profoundly alter the geochemical processes in surrounding ecosystems, mobilizing naturally occurring elements such as arsenic into soil, water, and food chains. Following the 2020 Taal Volcano eruption, concerns emerged regarding elevated iAs exposure among nearby populations. Although arsenic contamination in volcanic regions has been documented globally, few studies have applied an aggregate, probabilistic approach integrating both dietary and drinking water pathways. By combining environmental monitoring data with Monte Carlo–based exposure modeling, this study provides the first quantitative characterization of post-eruption iAs exposure among residents of Batangas, Philippines. The findings contribute to a better understanding of how volcanic events can intensify environmental contamination and potentially influence long-term population health risks.

Overall, the modeled iAs concentrations in food crops were consistent with measured values reported in the literature. The reconstructed concentrations of iAs in terrestrial crops followed the order rice > corn > vegetables > root crops, consistent with findings from the European Food Safety Authority (Authority et al., 2021). EFSA similarly identified rice and rice-based products as the dominant contributors to dietary iAs intake due to the efficient uptake of arsenic under flooded paddy conditions, where reduced soil environments promote arsenite formation and bioavailability. The modeled iAs concentrations in this study align with real-world monitoring data, in which rice typically contains 0.026-0.76 mg/kg and vegetables and tubers generally remain below 0.03 mg/kg (Lynch et al., 2014). The mean iAs concentrations in rice (0.13 mg/kg) reported in the literature is within the same order of magnitude as the simulated values in this study.

Similarly, the modeled iAs concentrations in fish were comparable with field measurements from the Philippines. In Laguana de Bay, total As concentrations in fish ranged from 0.15-0.39 mg/kg during the dry season and 0.018-0.107 mg/kg during the wet season (Molina & Kada, 2014). Assuming that 11.7-14.2 % of total As occurs in the inorganic form, the modeled iAs concentrations in this study fall within the same order of magnitude. This correspondence suggests that the applied bioaccumulation and dry-season correction factors effectively represent the hydrological and geochemical dynamics of Taal Lake following the 2020 eruption. The strong agreement between simulated and observed data supports the reliability of the probabilistic reconstruction framework in characterizing post-eruption arsenic contamination in the Batangas region.

Although the majority of arsenic in fish and clams exists as less toxic organic forms, aquatic foods remain important contributors to aggregate iAs exposure. This is attributable to the combination of relatively high total arsenic concentrations in these species and the substantial seafood consumption rates among Filipinos (mean fish intake = 59 g/day; “crustaceans and molluscs,” representing clams= 8.5 g/day). Experimental evidence further indicates that under elevated iAs exposure, biotransformation efficiency in clams may decline, leading to increased accumulation of iAs. In Asaphis violascens, exposure to rising concentrations of As(III) or As(V) resulted in a marked reduction in arsenobetaine (AsB) and a concomitant increase in dimethylarsinic acid (DMA) and inorganic arsenic fractions—reaching up to several tens of percent under high exposure conditions. Uptake of As(III) was found to exceed that of As(V), suggesting dose-dependent bioaccumulation and altered speciation dynamics (Zhang et al., 2019). These findings demonstrate that even when the inorganic fraction is relatively small, the combination of high total arsenic concentrations and frequent seafood consumption can substantially elevate aggregate exposures among lake-dependent communities.

Local dependence on Taal Lake fisheries creates a unique vulnerability for surrounding communities. Before the 2020 eruption, the lake produced approximately 5,000 metric tons of fish annually and served as the primary livelihood for many households. Post-eruption contamination and fishing restrictions now impose dual pressures—elevated chemical exposure for those who continue harvesting and economic displacement for those who cannot. Similar patterns have been documented in other volcanic lake systems, such as Lake Atitlán in Guatemala, Lake Ilopango in El Salvador, and several Indonesian calderas, where aquatic resources remain simultaneously contaminated yet economically indispensable. Addressing these intertwined environmental and socioeconomic challenges requires risk management approaches that integrate environmental health with economic justice, including continued biomonitoring with defined thresholds for issuing consumption advisories, livelihood diversification programs for affected households, exploration of feasible arsenic reduction strategies for aquaculture, and transparent risk communication to support informed decision-making within impacted communities.

Pregnant women exhibited lower aggregate iAs doses than the general adult population, likely reflecting culturally embedded dietary restrictions on fish and shellfish consumption during pregnancy across Southeast Asia (Köhler et al., 2019). While these practices may reduce high-iAs exposure pathways, they also carry the unintended consequence of limiting intake of critical nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids, iodine, and high-quality protein. Notably, despite experiencing approximately 40–50% lower exposure, pregnant women in this study still exceeded the U.S. EPA reference dose by 30–33 fold. Given the heightened developmental vulnerability of the fetus—and well-documented associations between prenatal arsenic exposure and reduced birth weight, increased infant mortality, and impaired cognitive development (Naujokas et al., 2013; Tolins et al., 2014)—targeted public health interventions are warranted. Priority actions include prenatal urinary arsenic speciation monitoring, nutritional counseling that emphasizes low-arsenic protein alternatives, folate and vitamin B12 supplementation to enhance arsenic methylation capacity, selection of lower-arsenic rice varieties, and strengthened prenatal screening for arsenic-associated outcomes.

The sensitivity analysis identified clam intake, rice intake, iAs in rice, iAs in clams, and iAs in drinking water as the dominant determinants of aggregate exposure. This finding aligns with well-established evidence that food and drinking water constitute the principal exposure pathways for iAs (Caceres et al., 2005; Yost et al., 2004). According to EFSA’s report, rice and rice-based products are consistently the largest contributors to dietary iAs exposure across all age groups, followed by drinking water and other grain-based commodities (Authority et al., 2021). Rice is uniquely efficient in accumulating arsenic because its cultivation under flooded, anaerobic conditions enhances the mobilization and uptake of arsenite, the more bioavailable and toxic inorganic form. Similarly, shellfish and bivalves such as clams can accumulate iAs through sediment interactions, making them important but variable contributors to total intake depending on local geochemical conditions. Drinking water, though generally containing lower concentrations (~2 µg/L on average), remains a critical exposure route due to high daily consumption volumes. These findings mirror the present study’s results, in which both dietary and waterborne pathways were key determinants of aggregate exposure, underscoring the need for integrated mitigation strategies targeting both food and water contamination.

All simulated individuals exhibited HQs greater than 1 in both lower- and upper-bound scenarios, with maximum HQs of 212.8 and 286.1, respectively. These levels far exceed the U.S. EPA’s reference dose of 0.06 µg/kg bw/day, indicating substantial non-cancer health risks. Likewise, all simulated lifetime excess cancer risks exceeded the benchmark range of 10⁻⁶–10⁻⁴, with most values between 10⁻² and 1, suggesting markedly elevated cancer risks. These risk magnitudes are comparable to those observed in volcanic or geothermal regions such as Latin-American countries (Costa et al., 2024) and southern Italy (Salvo et al., 2018), where naturally occurring arsenic contamination has led to significant population-level health impacts. These results highlight the urgent need for systematic environmental and biomonitoring programs to assess exposure trends over time and evaluate the effectiveness of mitigation strategies. Furthermore, establishing post-eruption baseline levels of iAs in soil, water, and locally produced food is essential to accurately characterize long-term exposure and effectively communicate environmental health risks to affected communities.

This study highlights the need for an integrated public health response that encompasses post-eruption health surveillance registries to track arsenic-associated outcomes, population-based urinary, nail, or hair arsenic biomonitoring with biospeciation stratified by age, sex, pregnancy status, and proximity to the volcano, and clinical screening programs embedded within existing Philippine health systems. Longitudinal environmental monitoring is also essential to capture temporal trends in contamination, alongside capacity building in arsenic toxicology, exposure science, and risk assessment among local health professionals. Coordinated efforts among the Philippine Inter-Agency Committee on Environmental Health, PHIVOLCS, academic institutions, and international partners will be critical for establishing post-eruption baselines and ensuring an effective, sustained response to protect affected communities.

Despite these important findings, several limitations should be acknowledged. This study relied on total As concentrations measured in soil, Taal lake water, and clams, without direct determination of iAs in locally cultivated crops and fish. Additional speciation analyses and expanded food monitoring are therefore warranted to reduce uncertainty in exposure estimates. The transfer factors and bioaccumulation parameters used to reconstruct iAs concentrations were derived from studies conducted in diverse geochemical settings and may not fully capture local volcanic soil conditions. Arsenic uptake in crops is strongly influenced by soil pH, organic matter, iron and aluminum oxides, redox conditions, irrigation practices, and rice cultivar genetics, and Philippine rice varieties may differ substantially from those examined in Bangladesh, China, or other regions. Moreover, volcanic ash–derived soils in Batangas—characterized by high glass shard content, variable post-eruption pH, elevated sulfur and fluorine, and short-range-order minerals such as allophane and imogolite—possess geochemical properties distinct from the alluvial and deltaic soils where most transfer factor studies have been conducted. These differences may alter arsenic sorption, mobility, and crop uptake patterns, and future research should prioritize direct measurement of region-specific transfer factors and validation using iAs concentrations in locally grown foods.

Dietary patterns in Batangas may also deviate from national averages, particularly in lakeshore communities where fish and clam consumption is likely higher than in the general population. Post-eruption livelihood disruptions may have further shifted food consumption behaviors relative to pre-2020 conditions. Vulnerable subgroups—including children, lactating women, and older adults—may have distinct intake profiles and heightened susceptibility to arsenic toxicity, highlighting the importance of region-specific dietary surveys to improve exposure assessment precision. Additionally, the absence of pre-eruption baseline data limits the ability to characterize temporal trends in environmental arsenic mobilization and post-eruption recovery.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provides the first integrated, post-eruption probabilistic assessment of iAs exposure in Batangas. The findings demonstrate that both dietary and drinking water pathways substantially contribute to elevated health risks among residents, particularly through rice, clams, and drinking water. These results underscore the urgent need for comprehensive monitoring, targeted risk communication, and sustainable mitigation strategies to protect public health. Establishing long-term surveillance and biomonitoring programs will be critical for tracking exposure trends and supporting evidence-based management in this and other volcanic regions affected by arsenic contamination.

Funding

This work was supported by a Suballotment Grant (Department Order 2022-069) from the Department of Health, Philippines, through the Disease Prevention and Control Bureau.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yu-Syuan Luo: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Validation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft. Jullian Patrick C. Azores: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing-review & editing . Rhodora M. Reyes: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing-review & editing. Geminn Louis C. Apostol: Writing-Original Draft.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. .

Acknowledgments

Design components of the graphical abstract were partially sourced from Flaticon.com. We also thank the Department of Health, Center for Health Development IV-A, and the local government of Batangas Province, Philippines, for their support in this study.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author utilized ChatGPT-5 to enhance the quality of the English writing. Following the use of this tool, the author thoroughly reviewed and revised the content as necessary and assumes full responsibility for the content of the published article.

References

- Apostol, G. L. C., Valenzuela, S., & Seposo, X. (2022). Arsenic in groundwater sources from selected communities surrounding Taal Volcano, Philippines: An exploratory study. Earth, 3(1), 448–459.

- Authority, E. F. S., Arcella, D., Cascio, C., & Gómez Ruiz, J. Á. (2021). Chronic dietary exposure to inorganic arsenic. Efsa Journal, 19(1), e06380.

- Authority, P. S. (2022). Age and Sex Distribution in the Philippine Population (2020 Census of Population and Housing). Retrieved 10/12 from https://psa.gov.ph/content/age-and-sex-distribution-philippine-population-2020-census-population-and-housing#:~:text=Fri%2C%2008/12/2022,males%20for%20every%20100%20females.

- Azores, J. P., Tumlos, R., Agapito, J., Sucgang, R., Jagonoy, A., & Tagayom, A. (2025). Radionuclide Consumption Health Risk Assessment of Asian Clam (Corbicula fluminea) in Volcanic Lake of Taal, Philippines. Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 28(1).

- Banta, G., & Salibay, C. (2023). Heavy metal contamination in the soil and Taal Lake Post-Taal Volcano eruption. Journal of Applied Science, Engineering, Technology, and Education, 5(2), 150–158.

- BFAR. (2024). 2023 Philippine Fisheries Profile. https://www.bfar.da.gov.ph/media-resources/publications/archives-philippine-fisheries-profile/.

- Bia, G., Garcia, M. G., Cosentino, N. J., & Borgnino, L. (2022). Dispersion of arsenic species from highly explosive historical volcanic eruptions in Patagonia. Sci Total Environ, 853, 158389. [CrossRef]

- Bundschuh, J., Schneider, J., Alam, M. A., Niazi, N. K., Herath, I., Parvez, F., Tomaszewska, B., Guilherme, L. R. G., Maity, J. P., & López, D. L. (2021). Seven potential sources of arsenic pollution in Latin America and their environmental and health impacts. Science of The Total Environment, 780, 146274.

- Bundschuh, J., Schneider, J., Alam, M. A., Niazi, N. K., Herath, I., Parvez, F., Tomaszewska, B., Guilherme, L. R. G., Maity, J. P., Lopez, D. L., Cirelli, A. F., Perez-Carrera, A., Morales-Simfors, N., Alarcon-Herrera, M. T., Baisch, P., Mohan, D., & Mukherjee, A. (2021). Seven potential sources of arsenic pollution in Latin America and their environmental and health impacts. Sci Total Environ, 780, 146274. [CrossRef]

- Caceres, D. D., Pino, P., Montesinos, N., Atalah, E., Amigo, H., & Loomis, D. (2005). Exposure to inorganic arsenic in drinking water and total urinary arsenic concentration in a Chilean population. Environmental Research, 98(2), 151–159.

- Costa, F. C. R., Moreira, V. R., Guimarães, R. N., Moser, P. B., & Amaral, M. C. S. (2024). Arsenic in natural waters of Latin-American countries: Occurrence, risk assessment, low-cost methods, and technologies for remediation. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 184, 116–128.

- Ermolin, M. S., Fedotov, P. S., Malik, N. A., & Karandashev, V. K. (2018). Nanoparticles of volcanic ash as a carrier for toxic elements on the global scale. Chemosphere, 200, 16–22. [CrossRef]

- FNRI. (2022). Philippine nutrition facts and figures: 2018-2019 Expanded National Nutrition Survey (ENNS) FNRI. https://enutrition.fnri.dost.gov.ph/uploads/2018-2019%20Facts%20and%20Figures%20-%20Food%20Consumption%20Survey.pdf.

- FNRI. (2024). Philippine Nutrition Facts and Figures: 2021 Expanded National Nutrition Survey FNRI.

- Garcia, M. B., Mangaba, J. B., & Vinluan, A. A. (2020). Towards the development of a personalized nutrition knowledge-based system: a mixed-methods needs analysis of virtual dietitian. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 9(4), 2068–2074.

- Hong, Y.-S., Song, K.-H., & Chung, J.-Y. (2014). Health effects of chronic arsenic exposure. Journal of preventive medicine and public health, 47(5), 245.

- Huang, R.-Q., Gao, S.-F., Wang, W.-L., Staunton, S., & Wang, G. (2006). Soil arsenic availability and the transfer of soil arsenic to crops in suburban areas in Fujian Province, southeast China. Science of The Total Environment, 368(2-3), 531–541.

- Kar, S., Maity, J. P., Jean, J. S., Liu, C. C., Liu, C. W., Bundschuh, J., & Lu, H. Y. (2011). Health risks for human intake of aquacultural fish: Arsenic bioaccumulation and contamination. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng, 46(11), 1266–1273. [CrossRef]

- Kerdthep, P., Tongyonk, L., & Rojanapantip, L. (2009). Concentrations of cadmium and arsenic in seafood from Muang District, Rayong Province. J. Health Res, 23(179), e184.

- Koesmawati, T. A., & Arifin, Z. (2015). Mercury and arsenic content in seafood samples from the Jakarta fishing port, Indonesia. Marine Research in Indonesia, 40(1), 9–16.

- Köhler, R., Lambert, C., & Biesalski, H. K. (2019). Animal-based food taboos during pregnancy and the postpartum period of Southeast Asian women–A review of literature. Food Research International, 115, 480–486.

- Lynch, H. N., Greenberg, G. I., Pollock, M. C., & Lewis, A. S. (2014). A comprehensive evaluation of inorganic arsenic in food and considerations for dietary intake analyses. Science of The Total Environment, 496, 299–313.

- McCarty, K. M., Hanh, H. T., & Kim, K.-W. (2011). Arsenic geochemistry and human health in South East Asia. Reviews on environmental health, 26(1), 71.

- Menon, M., Smith, A., & Fennell, J. (2022). Essential nutrient element profiles in rice types: a risk–benefit assessment including inorganic arsenic. British Journal of Nutrition, 128(5), 888–899.

- Molina, V. B., & Kada, R. (2014). Carcinogenic health risk of arsenic in five commercially important fish from Laguna de Bay, Philippines. Acta Medica Philippina, 48(3).

- Murray, J., Guzmán, S., Tapia, J., & Nordstrom, D. K. (2023). Silicic volcanic rocks, a main regional source of geogenic arsenic in waters: Insights from the Altiplano-Puna plateau, Central Andes. Chemical Geology, 629, 121473.

- Nachman, K. E., Ginsberg, G. L., Miller, M. D., Murray, C. J., Nigra, A. E., & Pendergrast, C. B. (2017). Mitigating dietary arsenic exposure: Current status in the United States and recommendations for an improved path forward. Sci Total Environ, 581-582, 221–236. [CrossRef]

- Naujokas, M. F., Anderson, B., Ahsan, H., Aposhian, H. V., Graziano, J. H., Thompson, C., & Suk, W. A. (2013). The broad scope of health effects from chronic arsenic exposure: update on a worldwide public health problem. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121(3), 295–302.

- Ngoc, N. T. M., Chuyen, N. V., Thao, N. T. T., Duc, N. Q., Trang, N. T. T., Binh, N. T. T., Sa, H. C., Tran, N. B., Ba, N. V., Khai, N. V., Son, H. A., Han, P. V., Wattenberg, E. V., Nakamura, H., & Thuc, P. V. (2020). Chromium, Cadmium, Lead, and Arsenic Concentrations in Water, Vegetables, and Seafood Consumed in a Coastal Area in Northern Vietnam. Environ Health Insights, 14, 1178630220921410. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M., Ng, J. C., & Naidu, R. (2009). Chronic exposure of arsenic via drinking water and its adverse health impacts on humans. Environmental geochemistry and health, 31(Suppl 1), 189–200.

- Rodriguez-Hernandez, A., Diaz-Diaz, R., Zumbado, M., Bernal-Suarez, M. D. M., Acosta-Dacal, A., Macias-Montes, A., Travieso-Aja, M. D. M., Rial-Berriel, C., Henriquez Hernandez, L. A., Boada, L. D., & Luzardo, O. P. (2022). Impact of chemical elements released by the volcanic eruption of La Palma (Canary Islands, Spain) on banana agriculture and European consumers. Chemosphere, 293, 133508. [CrossRef]

- Rokonuzzaman, M. D., Li, W. C., Wu, C., & Ye, Z. H. (2022). Human health impact due to arsenic contaminated rice and vegetables consumption in naturally arsenic endemic regions. Environ Pollut, 308, 119712. [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Castor, J., Guzmán-Mar, J., Alfaro-Barbosa, J., Hernández-Ramírez, A., Pérez-Maldonado, I., Caballero-Quintero, A., & Hinojosa-Reyes, L. (2014). Evaluation of the transfer of soil arsenic to maize crops in suburban areas of San Luis Potosi, Mexico. Science of The Total Environment, 497, 153–162.

- Salvo, A., La Torre, G. L., Mangano, V., Casale, K. E., Bartolomeo, G., Santini, A., Granata, T., & Dugo, G. (2018). Toxic inorganic pollutants in foods from agricultural producing areas of Southern Italy: Level and risk assessment. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 148, 114–124.

- Sarwar, T., Khan, S., Muhammad, S., & Amin, S. (2021). Arsenic speciation, mechanisms, and factors affecting rice uptake and potential human health risk: A systematic review. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 22, 101392.

- Schuhmacher–Wolz, U., Dieter, H. H., Klein, D., & Schneider, K. (2009). Oral exposure to inorganic arsenic: evaluation of its carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic effects. Critical reviews in toxicology, 39(4), 271–298.

- Solis, K. L. B., Macasieb, R. Q., Parangat Jr, R. C., Resurreccion, A. C., & Ocon, J. D. (2020). Spatiotemporal variation of groundwater arsenic in Pampanga, Philippines. Water, 12(9), 2366.

- Straif, K., Benbrahim-Tallaa, L., Baan, R., Grosse, Y., Secretan, B., El Ghissassi, F., Bouvard, V., Guha, N., Freeman, C., & Galichet, L. (2009). A review of human carcinogens—part C: metals, arsenic, dusts, and fibres. The lancet oncology, 10(5), 453–454.

- Tolins, M., Ruchirawat, M., & Landrigan, P. (2014). The developmental neurotoxicity of arsenic: cognitive and behavioral consequences of early life exposure. Annals of global health, 80(4), 303–314.

- USEPA. (2025). IRIS Toxicological Review of Inorganic Arsenic. https://iris.epa.gov/document/&deid=363892#downloads.

- Wang, D., Kim, B. F., Nachman, K. E., Chiger, A. A., Herbstman, J., Loladze, I., Zhao, F. J., Chen, C., Gao, A., Zhu, Y., Li, F., Shen, R. F., Yan, X., Zhang, J., Cai, C., Song, L., Shen, M., Ma, C., Yang, X.,…Ziska, L. H. (2025). Impact of climate change on arsenic concentrations in paddy rice and the associated dietary health risks in Asia: an experimental and modelling study. Lancet Planet Health, 9(5), e397–e409. [CrossRef]

- Witham, C. S., Oppenheimer, C., & Horwell, C. J. (2005). Volcanic ash-leachates: a review and recommendations for sampling methods. Journal of volcanology and Geothermal Research, 141(3-4), 299–326.

- Xu, L., Polya, D. A., Li, Q., & Mondal, D. (2020). Association of low-level inorganic arsenic exposure from rice with age-standardized mortality risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in England and Wales. Sci Total Environ, 743, 140534. [CrossRef]

- Yost, L., Tao, S.-H., Egan, S., Barraj, L., Smith, K., Tsuji, J., Lowney, Y., Schoof, R., & Rachman, N. (2004). Estimation of dietary intake of inorganic arsenic in US children. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment, 10(3), 473–483.

- Zhang, W., Guo, Z., Wu, Y., Qiao, Y., & Zhang, L. (2019). Arsenic bioaccumulation and biotransformation in clams (Asaphis violascens) exposed to inorganic arsenic: effects of species and concentrations. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 103(1), 114–119.

Figure 1.

Simulated concentrations of inorganic arsenic (iAs) in major food groups under lower-bound and upper-bound exposure scenarios. Boxplots show the distribution of estimated iAs concentrations (µg/g or ppm, log scale) across 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations for five dietary categories: fish, rice, corn, vegetables, and root crops. The lower-bound (LB; white boxes) and upper-bound (UB; gray boxes) scenarios represent conservative and worst-case assumptions, respectively, reflecting differences in seasonal concentration factors and conversion rates of total arsenic to inorganic arsenic. Boxes show medians and minimum-maximum ranges, with whiskers indicating 5th–95th percentiles.

Figure 1.

Simulated concentrations of inorganic arsenic (iAs) in major food groups under lower-bound and upper-bound exposure scenarios. Boxplots show the distribution of estimated iAs concentrations (µg/g or ppm, log scale) across 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations for five dietary categories: fish, rice, corn, vegetables, and root crops. The lower-bound (LB; white boxes) and upper-bound (UB; gray boxes) scenarios represent conservative and worst-case assumptions, respectively, reflecting differences in seasonal concentration factors and conversion rates of total arsenic to inorganic arsenic. Boxes show medians and minimum-maximum ranges, with whiskers indicating 5th–95th percentiles.

Figure 2.

Contribution of individual exposure pathways to total inorganic arsenic (iAs) intake under lower-bound and upper-bound scenarios. The left panel shows the percentage contribution of each pathway under the lower-bound scenario (iAs conversion factor=0.5 for rice, corn, vegetable, and root crops), while the right panel reflects the upper-bound scenario (iAs conversion factor =0.9). Drinking water and rice were the dominant sources of iAs intake across both scenarios, followed by fish and clam consumption. Root crops and vegetables contributed minimally. These estimates are based on probabilistic modeling incorporating concentration and consumption variability.

Figure 2.

Contribution of individual exposure pathways to total inorganic arsenic (iAs) intake under lower-bound and upper-bound scenarios. The left panel shows the percentage contribution of each pathway under the lower-bound scenario (iAs conversion factor=0.5 for rice, corn, vegetable, and root crops), while the right panel reflects the upper-bound scenario (iAs conversion factor =0.9). Drinking water and rice were the dominant sources of iAs intake across both scenarios, followed by fish and clam consumption. Root crops and vegetables contributed minimally. These estimates are based on probabilistic modeling incorporating concentration and consumption variability.

Figure 3.

Distribution of simulated aggregate inorganic arsenic (iAs) dose among residents of Batangas, Philippines, under lower- and upper-bound exposure scenarios. Violin plots show the distribution of daily iAs doses (µg/kg-day) from 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations for the total population (All) and subgroups (Male, Female, Pregnancy). The left and right panels represent lower-bound and upper-bound scenarios, respectively. The red dashed line indicates the U.S. EPA oral reference dose (RfD) for inorganic arsenic (0.06 µg/kg-day).

Figure 3.

Distribution of simulated aggregate inorganic arsenic (iAs) dose among residents of Batangas, Philippines, under lower- and upper-bound exposure scenarios. Violin plots show the distribution of daily iAs doses (µg/kg-day) from 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations for the total population (All) and subgroups (Male, Female, Pregnancy). The left and right panels represent lower-bound and upper-bound scenarios, respectively. The red dashed line indicates the U.S. EPA oral reference dose (RfD) for inorganic arsenic (0.06 µg/kg-day).

Figure 5.

Cumulative distribution of hazard quotient (HQ) for total inorganic arsenic (iAs) intake under lower- (blue) and upper-bound (orange) exposure scenarios. The plot shows the empirical cumulative distribution functions of the simulated HQ values for total iAs intake based on 10,000 Monte Carlo iterations for each scenario. The vertical dotted line at HQ = 1 represents the U.S. EPA reference dose (RfD) threshold for non-cancer health effects (0.06 µg/kg bw/day).

Figure 5.

Cumulative distribution of hazard quotient (HQ) for total inorganic arsenic (iAs) intake under lower- (blue) and upper-bound (orange) exposure scenarios. The plot shows the empirical cumulative distribution functions of the simulated HQ values for total iAs intake based on 10,000 Monte Carlo iterations for each scenario. The vertical dotted line at HQ = 1 represents the U.S. EPA reference dose (RfD) threshold for non-cancer health effects (0.06 µg/kg bw/day).

Figure 6.

Lifetime excess cancer risk (ECR) from inorganic arsenic (iAs) exposure among residents of Batangas, Philippines, under lower-bound (LB) and upper-bound (UB) exposure scenarios. Red dashed lines denote the U.S. EPA benchmark risk range for lifetime cancer risk (10⁻⁶–10⁻⁴).

Figure 6.

Lifetime excess cancer risk (ECR) from inorganic arsenic (iAs) exposure among residents of Batangas, Philippines, under lower-bound (LB) and upper-bound (UB) exposure scenarios. Red dashed lines denote the U.S. EPA benchmark risk range for lifetime cancer risk (10⁻⁶–10⁻⁴).

Table 2.

Sex-specific body weight and height parameters used in the Monte Carlo simulation, modeled as truncated normal distributions with defined mean, standard deviation (SD), and plausible bounds.

Table 2.

Sex-specific body weight and height parameters used in the Monte Carlo simulation, modeled as truncated normal distributions with defined mean, standard deviation (SD), and plausible bounds.

| Sex |

Parameter |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

| Male |

Body weight (kg) |

61.3 |

9.0 |

40 |

155 |

| |

Height (cm) |

163.0 |

6.5 |

60 |

220 |

| Female |

Body weight (kg) |

54.3 |

8.5 |

35 |

145 |

| |

Height (cm) |

154.0 |

6.0 |

55 |

210 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).