Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

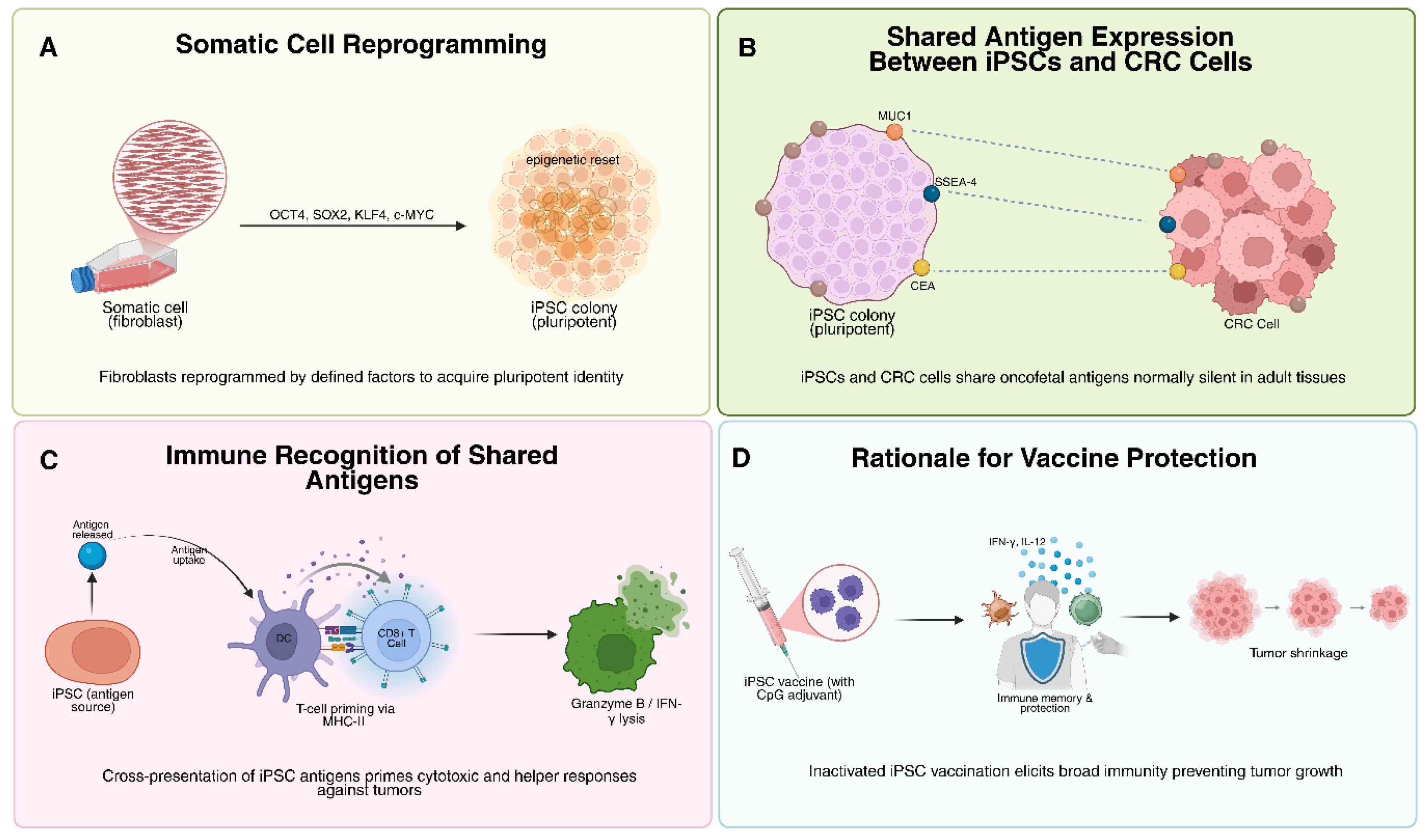

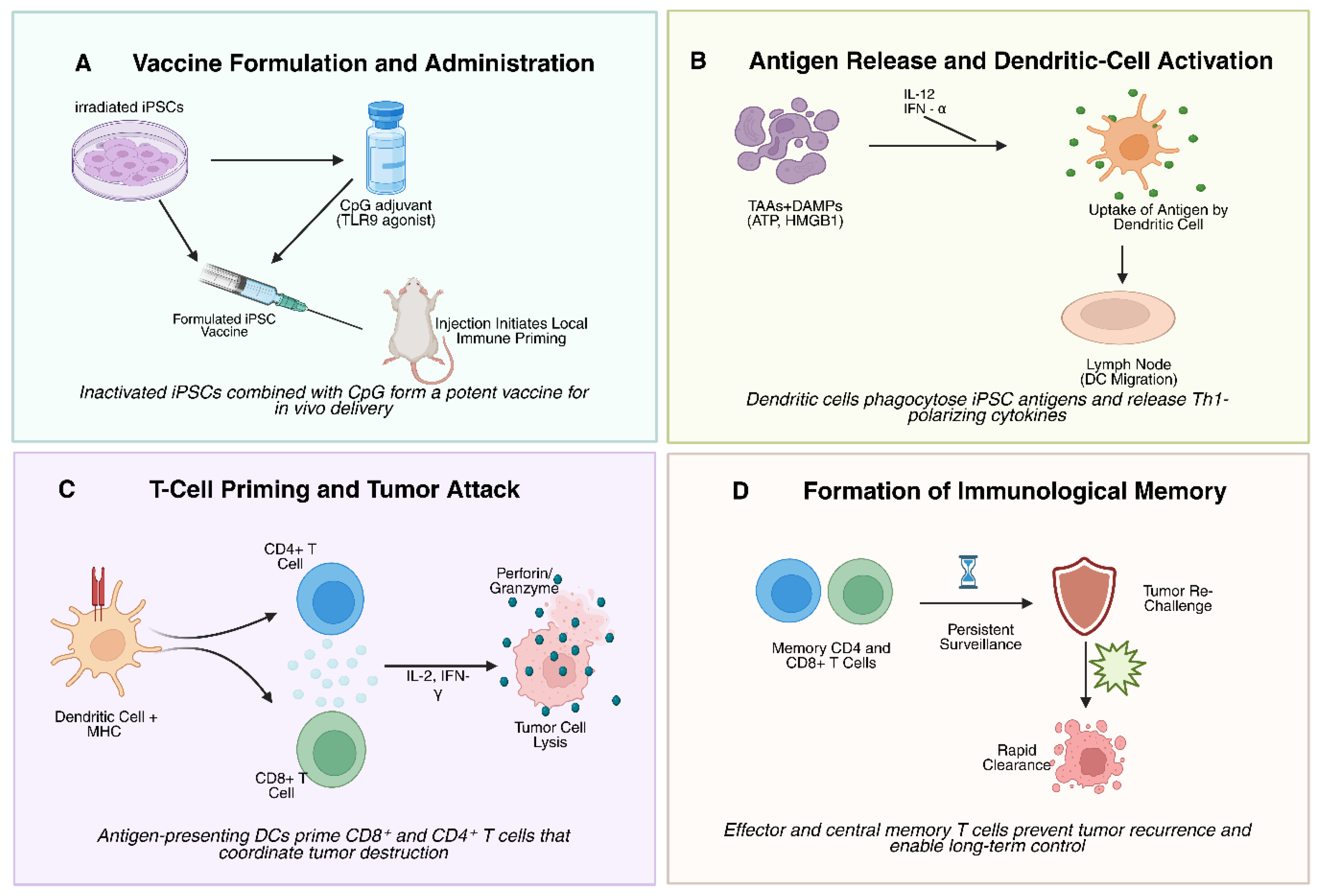

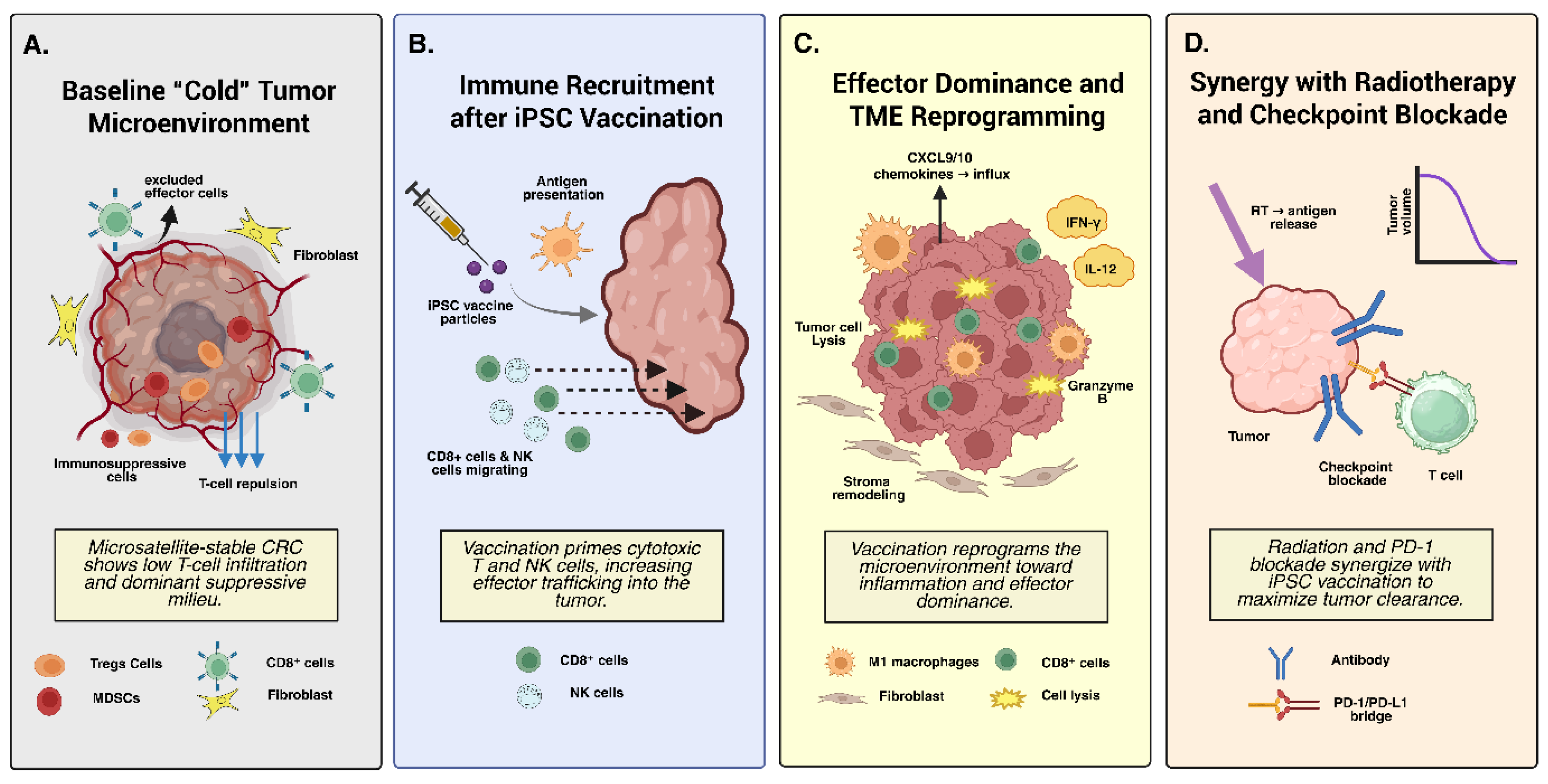

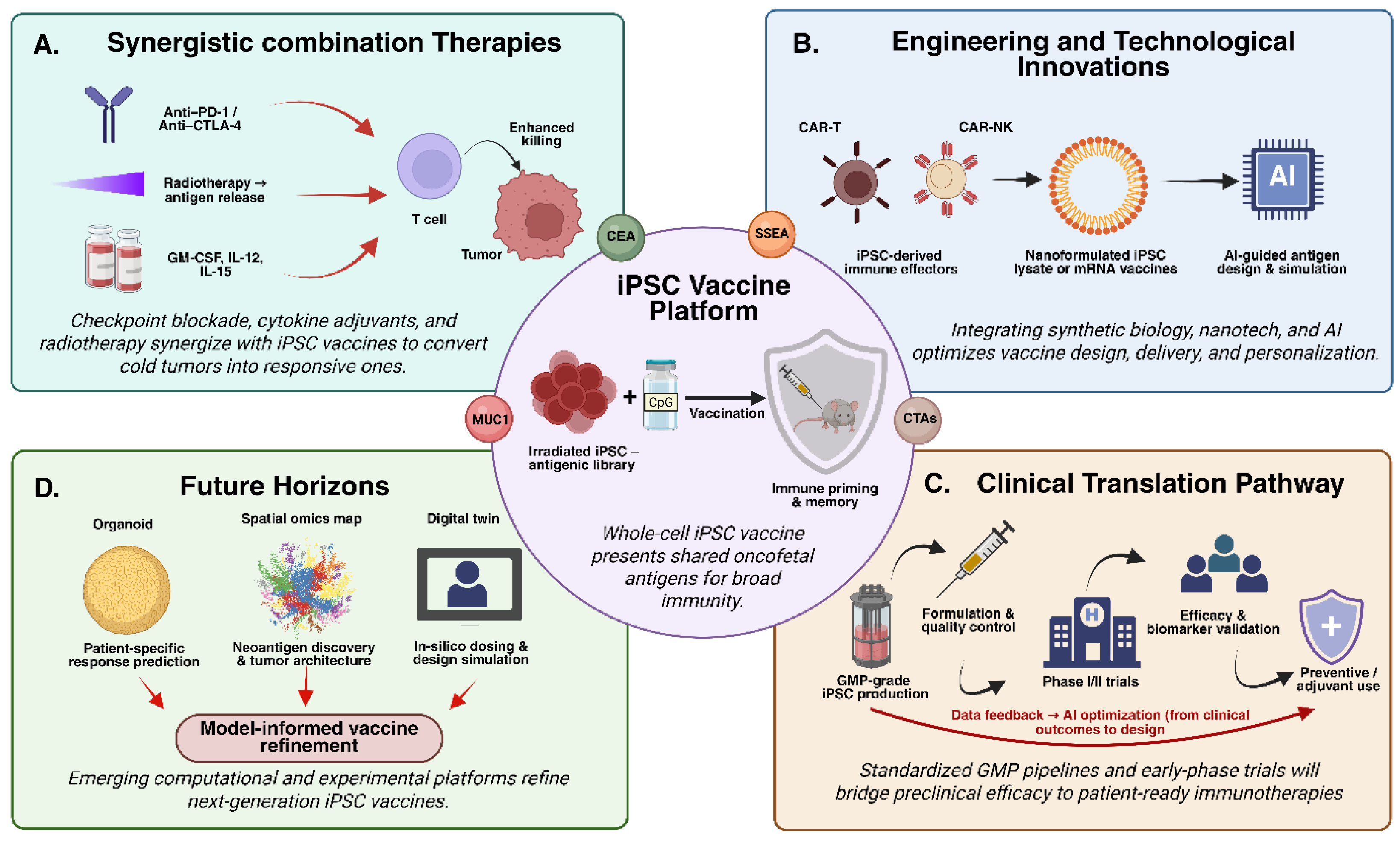

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) exerts a growing global disease burden, with microsatellite-stable/proficient mismatch repair (MSS/pMMR) tumors exhibiting intrinsic refractoriness to immune-checkpoint blockade (ICB) owing to low tumor mutational burden, limited neoantigenicity, and an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) dominated by regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). This review evaluates induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)–derived polyvalent vaccines as ontogenetically recapitulative immunogens capable of reinstating broad antitumor immunity. Reprogramming induces re-expression of oncofetal tumor-associated antigens, including cancer-testis antigens (NY-ESO-1, MAGE-A3), aberrant glycoforms of CEA and MUC1, and clinically actionable neoepitopes such as KRAS^G12D/V, thereby promoting epitope spreading and immunogenic cell death. Irradiated autologous or syngeneic iPSCs, delivered with Toll-like receptor 9 agonists, facilitate robust MHC I/II cross-presentation, driving CD8⁺ cytotoxic T-cell activation, Th1 polarization, perforin/granzyme-mediated cytolysis, and favorable effector-to-suppressor ratios. Preclinical models of melanoma, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, and MSS CRC demonstrate prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy, with neoantigen-enhanced iPSCs synergizing with radiotherapy-induced DAMPs to achieve durable regressions and memory T-cell formation. Translational priorities include CRISPR-engineered hypoimmunogenic iPSC platforms, GMP-compatible non-integrating reprogramming, and combinatorial integration with STING agonists, ICB, CAR-NK cells, and LNP-mRNA constructs to enable biomarker-guided clinical deployment in minimal-residual-disease CRC.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Foundations of iPSC-Based Cancer Vaccines

2.1. Oncofetal Similarities and Historical Rationale

2.3. Safety Considerations: Irradiation and Autoimmunity

3. Mechanisms of Anti-Tumor Immunity via iPSC Vaccines

3.1. Activation of Cellular and Humoral Immunity: T-Cell Priming, Effector Responses, and Tumor Infiltration

3.2. Development of Immunological Memory and Long-Term Tumor Protection

3.3. Integration of Neoantigens and Synergy with Radiotherapy

3.4. Innate Immune Activation and Remodeling of the Tumor Microenvironment

- a)

- b)

- Adaptive immune activation – DC-mediated priming leads to expansion of CD8⁺ CTLs and CD4⁺ Th1 cells, generating a cytotoxic and cytokine-rich immune response [53].

- c)

- Humoral response and epitope spreading – B-cell–derived antibodies complement cellular immunity, while tumor cell death releases additional antigens that broaden recognition [61].

- d)

- Memory formation – Effector and central memory T cells provide long-term surveillance, protecting against recurrence and metastasis [66].

- e)

- f)

- Microenvironment reprogramming – The balance of immune infiltrates shifts toward effector dominance (CD8⁺, NK, M1 macrophages) with reduced suppressive populations (Tregs, MDSCs) [79].

4.1. Cross Cancer Foundations and Translational Relevance to CRC

4.2. CRC-Specific iPSC Vaccine Studies and Antigen Discovery

4.3. Integrating iPSC Vaccines into the CRC Immunotherapy Landscape

4.4. Expanding CRC Vaccine Strategies: KRAS, CT Antigens, and Neoantigens

4.5. Future Integration: Delivery Innovations and Combination Therapies

4.6. Perspective

5. Tumor Microenvironment (TME): Challenges and Strategies, and Preclinical to Early Clinical Evidence of iPSC-Based Vaccines in Colorectal Cancer

5.1. Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer

5.2. iPSC Vaccine–Mediated Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment

| Vaccine Platform | Example / Target | Clinical Stage / Trial | Key Outcomes / Challenges |

| Whole-cell tumor vaccines | OncoVAX (irradiated autologous colon tumor + BCG) | Phase III (stage II/III CRC) | Reduced recurrence in stage II; modest benefit in stage III; logistic and cost barriers due to individualized manufacturing [125,126]. |

| Vigil™ (autologous tumor + GM-CSF + furin inhibitor) | Phase I / case reports | Safe; occasional long-term remissions in metastatic CRC; remains investigational with limited scalability [127,128,129]. | |

| Dendritic-cell vaccines | CEA-RNA/DC, p53-SLP/DC, tumor-lysate/DC | Phase I–II | Induced tumor-specific T cells in many patients; clinical responses modest; DC yield and standardization remain technical challenges [130]. |

| Peptide vaccines | KRAS G12D/V (ELI-002 2P) | Phase I (AMPLIFY-201) | 84 % of patients developed KRAS-specific T-cell responses; higher responders had prolonged RFS / OS; expanding to Phase II with PD-1 blockade [131]. |

| MUC1 long-peptide (OCV-501) | Phase II (adenoma prevention) | Immunogenic and well-tolerated; trend toward reduced adenoma recurrence [132,133]. | |

| CEA, NY-ESO-1 peptides | Phase I–II | Safe; variable T-cell induction; limited efficacy alone → supports multi-antigen combinations [134]. | |

| Nucleic-acid vaccines | DNA plasmid (pVAX1-CEA, pGS-21) | Early-phase / preclinical | Generated humoral + cellular responses; development shifting toward mRNA platforms. |

| mRNA (neoantigen / shared antigen) | Early clinical (Moderna, BioNTech) | Rapid, customizable; encouraging immunogenicity in GI tumors; CRC-focused trials ongoing. | |

| Viral-vector vaccines | MVA-CEA, MVA-MUC1 | Phase I | Strong innate activation; safe; combinable with adjuvants or checkpoint inhibitors [135]. |

| Oncolytic viruses (T-VEC, adenoviral constructs) | Preclinical / Phase I | Induce tumor lysis + immune priming; under evaluation for CRC metastases [136]. | |

| iPSC-based vaccines | Autologous iPSCs + CpG (syngeneic) | Preclinical (murine) | Multivalent antigen display; prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy; potent T-cell activation; teratoma-safe after irradiation; no human trials yet [37]. |

5.3. Combination Strategies to Overcome Immunosuppression

- Innate immune agonists: CpG (TLR9), poly(I:C) (TLR3), and imiquimod (TLR7) are among the most effective adjuvants for triggering DC maturation and type I interferon production. CpG has been used in nearly all iPSC vaccine formulations, but new synthetic TLR and STING agonists may provide stronger and more sustained DC activation [137]. STING agonists, for instance, promote cGAS-mediated interferon signaling, facilitating cross-presentation of tumor antigens to CD8⁺ cells [138].

- Checkpoint inhibitors: Checkpoint blockade is a logical partner for iPSC vaccines. Anti–PD-1, anti–PD-L1, or anti–CTLA-4 antibodies can release inhibitory constraints on iPSC-induced T cells, enhancing effector proliferation and cytotoxicity [139,140]. While MSS CRC rarely responds to checkpoint blockade alone, vaccines that expand tumor-reactive T cells can create sufficient immune infiltration to render these antibodies effective. Preclinical CRC models are currently testing iPSC + anti–PD-1 combinations, showing promising synergy in tumor control and survival extension [141].

- Cytokine adjuvants: Cytokines such as IL-12, IL-15, and GM-CSF can enhance T-cell survival and effector differentiation. GM-CSF, widely used in whole-cell vaccines (e.g., GVAX), recruits and matures DCs at vaccination sites. Low-dose IL-2 selectively supports effector T-cell expansion when carefully titrated to avoid Treg proliferation. IL-15 strengthens NK and memory CD8⁺ compartments, offering a complementary axis to checkpoint or vaccine-induced activation [142,143].

- Chemotherapy and radiotherapy: Certain cytotoxic agents have immunomodulatory roles. Oxaliplatin and cyclophosphamide induce immunogenic cell death, releasing tumor antigens and transiently depleting Tregs, respectively. Combining these with iPSC vaccination enhances antigen availability and reduces suppression [144]. RT not only provides local tumor control but also serves as an in-situ vaccine by increasing antigen release and vascular permeability, facilitating immune cell trafficking [120].

- Anti-angiogenic and metabolic modulators: Agents like bevacizumab (anti–VEGF) normalize tumor vasculature, improving T-cell access to the tumor parenchyma. Targeting tumor metabolism,such as IDO inhibitors to prevent tryptophan depletion or lactate blockers to reverse acidosis,could further enhance T-cell persistence and function after vaccination [145,146].

6. Preclinical and Early Clinical Data Supporting iPSC-Based Cancer Vaccines

6.1. Murine Model Evidence

6.2. Pancreatic Cancer iPSC Vaccine Models as CRC Analogs

6.3. Early Human Data: Lessons from KRAS Peptide Vaccines

7. Safety, Translational Considerations, and Opportunities for Innovation

7.1. Safety and Translational Considerations

7.2. Opportunities for Innovation

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

8.1. Conclusion

8.2. Future Directions

Funding

Authorship Contribution Statement

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgments

Ethical Statements

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

References

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl Oncol. 2021, 14, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Liu, Z.; Gong, G. Addressing the rising colorectal cancer burden in the older adult: examining modifiable risk and protective factors for comprehensive prevention strategies. Front Oncol. 2025, 15, 1487103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colorectal Cancer Survival Rates | Colorectal Cancer Prognosis [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 11]. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html.

- Marcellinaro, R.; Spoletini, D.; Grieco, M.; Avella, P.; Cappuccio, M.; Troiano, R.; et al. Colorectal Cancer: Current Updates and Future Perspectives. J Clin Med. 2023, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Gautam, V.; Sandhu, A.; Rawat, K.; Sharma, A.; Saha, L. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches for colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023, 15, 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, R.; Amar-Farkash, S.; Klein-Brill, A.; Rosenberg-Katz, K.; Aran, D. Comparative Analysis of First-Line FOLFOX Treatment With and Without Anti-VEGF Therapy in Metastatic Colorectal Carcinoma: A Real-World Data Study. Cancer Control. 2023, 30, 10732748231202470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmeiner, W.H. Recent Advances in Therapeutic Strategies to Improve Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Cancers. 2024, 16, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoudi González, N.; Salvà, F.; Ros, J.; Baraibar, I.; Rodríguez-Castells, M.; García, A.; et al. Unravelling the Complexity of Colorectal Cancer: Heterogeneity, Clonal Evolution, and Clinical Implications. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamura, K. Colorectal Cancers: An Update on Their Molecular Pathology. Cancers. 2018, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Zhou, W. Immunotherapy in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer: Strategies to overcome resistance. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2025, 212, 104775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizardo, D.Y.; Kuang, C.; Hao, S.; Yu, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L. Immunotherapy efficacy on mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer: From bench to bedside. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020, 1874, 188447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilusic, M.; Madan, R.A. Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines: The Latest Advancement in Targeted Therapy. Am J Ther. 2012, 19, e172–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallio, C.; Esposito, L.; Passardi, A. Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines in Colorectal Cancer: Platforms, Mechanisms, and Combinations. Cancers. 2025, 17, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, D.B.; Xue, Y.; Mahmud, F.; Jocelyn, J.A.; Sang, Q.X.A. Interconversion of Cancer Cells and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cells. 2024, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Orkin, S.H. Embryonic stem cell-specific signatures in cancer: insights into genomic regulatory networks and implications for medicine. Genome Med. 2011, 3, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, J.C.; Ng, H.H. Transcriptomic analysis of pluripotent stem cells: insights into health and disease. Genome Med. 2011, 3, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhu, T.; Hou, B.; Huang, X. An iPSC-derived exosome-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine boosts antitumor immunity in melanoma. Molecular Therapy. 2023, 31, 2376–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooreman, N.G.; Kim, Y.; de Almeida, P.E.; Termglinchan, V.; Diecke, S.; Shao, N.Y.; et al. Autologous iPSC-Based Vaccines Elicit Anti-tumor Responses In Vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2018, 22, 501–513.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaddanapudi, K.; Li, C.; Eaton, J.W. Vaccination with induced pluripotent stem cells confers protection against cancer. Stem Cell Investig. 2018, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes de Jesus, B.; Neves, B.M.; Ferreira, M.; Nóbrega-Pereira, S. Strategies for Cancer Immunotherapy Using Induced Pluripotency Stem Cells-Based Vaccines. Cancers. 2020, 12, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifa, N. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): The Ethical Alternative? Stem Cell Research and Regenerative Medicine. 2024, 7, 251–252. [Google Scholar]

- Attwood, S.W.; Edel, M.J. iPS-Cell Technology and the Problem of Genetic Instability,Can It Ever Be Safe for Clinical Use? J Clin Med. 2019, 8, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budach, W.; Paulsen, F.; Welz, S.; Classen, J.; Scheithauer, H.; Marini, P.; et al. Mitomycin C in combination with radiotherapy as a potent inhibitor of tumour cell repopulation in a human squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002, 86, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.C.Y.; Chen, W.T.L.; Chen, J.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Wu, C.H.; Lai, C.Y.; et al. Neoantigen-augmented iPSC cancer vaccine combined with radiotherapy promotes antitumor immunity in poorly immunogenic cancers. npj Vaccines. 2024, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jwo, S.H.; Ng, S.K.; Li, C.T.; Chen, S.P.; Chen, L.Y.; Liu, P.J.; et al. Dual prophylactic and therapeutic potential of iPSC-based vaccines and neoantigen discovery in colorectal cancer. Theranostics. 2025, 15, 5890–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Blériot, C.; Currenti, J.; Ginhoux, F. Oncofetal reprogramming in tumour development and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022, 22, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanala, V.L.; Zubair, M.; Mukkamalla, S.K.R. Carcinoembryonic Antigen. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 [cited 2025 Nov 11]. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578172/.

- Ouyang, X.; Telli, M.L.; Wu, J.C. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cancer Vaccines. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2019 July 8 [cited 2025 Nov 11];10. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01510/full.

- Wan, G.; Huang, J.D.; Xu, R.H.; Jin, M. Advances and Challenges in Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Whole-Cell Vaccines for Cancer Treatment. Medicine Bulletin. 2025, 1, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerneckis, J.; Cai, H.; Shi, Y. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs): molecular mechanisms of induction and applications. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, I.R.; Garrone, C.M.; Kerins, C.; Kiar, C.S.; Syntaka, S.; Xu, J.Z.; et al. Functional genomics and the future of iPSCs in disease modeling. Stem Cell Reports. 2022, 17, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, U.; Benvenisty, N. The tumorigenicity of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011, 11, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, R.; Uda, M.; Hoki, Y.; Sunayama, M.; Nakamura, M.; Ando, S.; et al. Negligible immunogenicity of terminally differentiated cells derived from induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2013, 494, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, S.; Yamanaka, S. To Be Immunogenic, or Not to Be: That’s the iPSC Question. Cell Stem Cell. 2013, 12, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, J.; Wei, T.T.; Liu, C.; et al. Antitumor effects of iPSC-based cancer vaccine in pancreatic cancer. Stem Cell Reports. 2021, 16, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooreman, N.G.; Kim, Y.; de Almeida, P.E.; Termglinchan, V.; Diecke, S.; Shao, N.Y.; et al. Autologous iPSC-Based Vaccines Elicit Anti-tumor Responses In Vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2018, 22, 501–513.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, S. Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cell Therapy,Promise and Challenges. Cell Stem Cell. 2020, 27, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, S.; Matzinger, P. Danger signals: SOS to the immune system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001, 13, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, X.; Wei, Y.; Yu, Y.; et al. Vaccine adjuvants: mechanisms and platforms. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Zhang, T.; Huang, H.; Feng, H.; Wang, S.; Guo, Z.; et al. Colorectal cancer vaccines: The current scenario and future prospects. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 942235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, A. The Promise and Predicament of Combining Adjuvants in Vaccines. Vaccine Insights. 2025, 4, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, C.; Liu, M.; Pan, X.; Zhu, H. Tumorigenicity risk of iPSCs in vivo: nip it in the bud. Prec Clin Med. 2022, 5, pbac004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Agboola, O.S.; Hu, X.; Wu, Y.; Lei, L. Tumorigenic and Immunogenic Properties of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: a Promising Cancer Vaccine. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020, 16, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. DAMPs and DAMP-sensing receptors in inflammation and diseases. Immunity. 2024, 57, 752–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandolfi, F.; Altamura, S.; Frosali, S.; Conti, P. Key Role of DAMP in Inflammation, Cancer, and Tissue Repair. Clinical Therapeutics. 2016, 38, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, X.; Telli, M.L.; Wu, J.C. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cancer Vaccines. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2019 July 8 [cited 2025 Nov 11];10. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01510/full.

- Ouyang, X.; Telli, M.L.; Wu, J.C. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cancer Vaccines. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Hong, S.G.; Winkler, T.; Spencer, D.M.; Jares, A.; Ichwan, B.; et al. Development of an inducible caspase-9 safety switch for pluripotent stem cell–based therapies. Molecular Therapy Methods & Clinical Development [Internet]. 2014 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Nov 11];1. Available online: https://www.cell.com/molecular-therapy-family/methods/abstract/S2329-0501(16)30122-X.

- Precision installation of a highly efficient suicide gene safety switch in human induced pluripotent stem cells - Shi - 2020 - STEM CELLS Translational Medicine - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 11]. Available online: https://stemcellsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sctm.20-0007?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Jin, M.Z.; Wang, X.P. Immunogenic Cell Death-Based Cancer Vaccines. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2021 May 31 [cited 2025 Nov 11];12. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.697964/full.

- Colbert, J.D.; Cruz, F.M.; Rock, K.L. Cross-presentation of exogenous antigens on MHC I molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 2020, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, D.; Fekete-Drimusz, N.; Saborowski, M.; Kühnel, F.; Woller, N. CD4 and CD8 T lymphocyte interplay in controlling tumor growth. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018, 75, 689–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkens, M.J.; Shedlock, D.J.; Jung, E.; Troy, A.; Pearce, E.L.; Shen, H.; et al. Th1 and Th2 Cells Help CD8 T-Cell Responses. Infect Immun. 2007, 75, 2291–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaddanapudi, K.; Li, C.; Eaton, J.W. Vaccination with induced pluripotent stem cells confers protection against cancer. Stem Cell Investigation [Internet]. 2018 July 23 [cited 2025 Nov 11];5(6). Available online: https://sci.amegroups.org/article/view/20487.

- Kishi, M.; Asgarova, A.; Desterke, C.; Chaker, D.; Artus, J.; Turhan, A.G.; et al. Evidence of Antitumor and Antimetastatic Potential of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Vaccines in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Med [Internet]. 2021 Dec 10 [cited 2025 Nov 11];8. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.729018/full. 7290. [Google Scholar]

- Florescu, D.N.; Boldeanu, M.V.; Șerban, R.E.; Florescu, L.M.; Serbanescu, M.S.; Ionescu, M.; et al. Correlation of the Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, Inflammatory Markers, and Tumor Markers with the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer. Life (Basel). 2023, 13, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pegram, M.D.; Wu, J.C. Induced pluripotent stem cells as a novel cancer vaccine. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019, 19, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Chang, X.; Ye, X.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Immunization with Embryonic Stem Cells/Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Induces Effective Immunity against Ovarian Tumor-Initiating Cells in Mice. Stem Cells International. 2023, 2023, 8188324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.; Pahl, J.; Schottelius, A.; Carter, P.J.; Koch, J. Reimagining antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in cancer: the potential of natural killer cell engagers. Trends in Immunology. 2022, 43, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellermann, G.; Leulliot, N.; Cherfils-Vicini, J.; Blaud, M.; Brest, P. Activated B-Cells enhance epitope spreading to support successful cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2024 Mar 19 [cited 2025 Nov 11];15. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1382236/full.

- Crews, D.W.; Dombroski, J.A.; King, M.R. Prophylactic Cancer Vaccines Engineered to Elicit Specific Adaptive Immune Response. Front Oncol [Internet]. 2021 Mar 29 [cited 2025 Nov 11];11. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2021.626463/full. 6264. [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, M.C.; Wu, C.J.; Fritsch, E.F. Cancer vaccines: Building a bridge over troubled waters. Cell. 2022, 185, 2770–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Pegram, M.D.; Wu, J.C. Induced pluripotent stem cells as a novel cancer vaccine. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2019, 19, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Hao, S.; Li, F.; Ye, Z.; Yang, J.; Xiang, J. CD4+ Th1 cells promote CD8+ Tc1 cell survival, memory response, tumor localization and therapy by targeted delivery of interleukin 2 via acquired pMHC I complexes. Immunology. 2007, 120, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontiers | Defining Memory CD8 T Cell [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 11]. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02692/full?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Sahin, I.H.; Ciombor, K.K.; Diaz, L.A.; Yu, J.; Kim, R. Immunotherapy for Microsatellite Stable Colorectal Cancers: Challenges and Novel Therapeutic Avenues. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2022, 42, 242–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Wu, S.; Yu, W. Progress of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Therapy for pMMR/MSS Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2024, 17, 1223–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, L.; Liu, M. Rethinking Antigen Source: Cancer Vaccines Based on Whole Tumor Cell/tissue Lysate or Whole Tumor Cell. Advanced Science. 2023, 10, 2300121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Merhi, M.; Inchakalody, V.P.; Krishnankutty, R.; Relecom, A.; Uddin, S.; et al. Unleashing the immune response to NY-ESO-1 cancer testis antigen as a potential target for cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2020, 18, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, M.; Cao, Y. Tumor antigens and vaccines in colorectal cancer. Medicine in Drug Discovery. 2022, 16, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Mullins, C.S.; Linnebacher, M. Colorectal cancer vaccines: Tumor-associated antigens vs neoantigens. World J Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 5418–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Z. Design and immunogenic evaluation of multi-epitope vaccines for colorectal cancer: insights from molecular dynamics and In-Vitro studies. Front Oncol [Internet]. 2025 June 17 [cited 2025 Nov 11];15. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1592072/full.

- Neoantigen-augmented iPSC cancer vaccine combined with radiotherapy promotes antitumor immunity in poorly immunogenic cancers | npj Vaccines [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 11]. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41541-024-00881-5. 4154.

- Huang, K.C.Y.; Chen, W.T.L.; Chen, J.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Wu, C.H.; Lai, C.Y.; et al. Neoantigen-augmented iPSC cancer vaccine combined with radiotherapy promotes antitumor immunity in poorly immunogenic cancers. NPJ Vaccines. 2024, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.Y.; Chang, C.M.; Liao, H.N.; Chou, W.H.; Guo, C.L.; Yen, Y.; et al. Current Trends in Neoantigen-Based Cancer Vaccines. Pharmaceuticals. 2023, 16, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xin, Z.; Wu, D.; Ni, C.; et al. Radiation-induced tumor immune microenvironments and potential targets for combination therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, F.; Ebert, M.; Cook, A.M. Leveraging radiotherapy to improve immunotherapy outcomes: rationale, progress and research priorities. Clinical & Translational Immunology. 2025, 14, e70030. [Google Scholar]

- Haist, M.; Stege, H.; Grabbe, S.; Bros, M. The Functional Crosstalk between Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Regulatory T Cells within the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gąbka-Buszek, A.; Kwiatkowska-Borowczyk, E.; Jankowski, J.; Kozłowska, A.K.; Mackiewicz, A. Novel Genetic Melanoma Vaccines Based on Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells or Melanosphere-Derived Stem-Like Cells Display High Efficacy in a murine Tumor Rejection Model. Vaccines (Basel). 2020, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Weng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, W.; Meng, W.; et al. Application of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells in Malignant Solid Tumors. Stem Cell Rev and Rep. 2023, 19, 2557–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krog, R.T.; de Miranda, N.F.C.C.; Vahrmeijer, A.L.; Kooreman, N.G. The Potential of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Advance the Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers. 2021, 13, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pegram, M.D.; Wu, J.C. Induced pluripotent stem cells as a novel cancer vaccine. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019, 19, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zein, M.; Boukhdoud, M.; Shammaa, H.; Mouslem, H.; El Ayoubi, L.M.; Iratni, R.; et al. Immunotherapy and immunoevasion of colorectal cancer. Drug Discovery Today. 2023, 28, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillo, T.O.; Beggs, A.D.; Morton, D.G.; Middleton, G. Mechanisms of immunogenicity in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2019, 106, 1283–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, T.; Cohen, R.; Salem, M.E. Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy in Patients With Colorectal Cancer Harboring Microsatellite Instability/Mismatch Repair Deficiency in 2022. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2022, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, P.M.; Adamik, J.; Howes, T.R.; Du, S.; Vujanovic, L.; Warren, S.; et al. Impact of checkpoint blockade on cancer vaccine–activated CD8+ T cell responses. J Exp Med. 2020, 217, e20191369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- From cold to hot tumors: feasibility of applying therapeutic insights to TNBC - PMC [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 12]. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12540225/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Wu, B.; Zhang, B.; Li, B.; Wu, H.; Jiang, M. Cold and hot tumors: from molecular mechanisms to targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hushmandi, K.; Imani Fooladi, A.A.; Reiter, R.J.; Farahani, N.; Liang, L.; Aref, A.R.; et al. Next-generation immunotherapeutic approaches for blood cancers: Exploring the efficacy of CAR-T and cancer vaccines. Experimental Hematology & Oncology. 2025, 14, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, J.; Chen, Y.; Chi, E.; Li, S.; He, Y.; Wang, B.; et al. New power in cancer immunotherapy: the rise of chimeric antigen receptor macrophage (CAR-M). Journal of Translational Medicine. 2025, 23, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M.; Poznańska, J.; Fechner, F.; Michalska, N.; Paszkowska, S.; Napierała, A.; et al. Cancer Vaccine Therapeutics: Limitations and Effectiveness,A Literature Review. Cells. 2023, 12, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; Li, Y.R. iPSC Technology Revolutionizes CAR-T Cell Therapy for Cancer Treatment. Bioengineering (Basel). 2025, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidadi, M.; Barzgar, H.; Zaman, M.; Paevskaya, O.A.; Metanat, Y.; Khodabandehloo, E.; et al. Combining the induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-based immunotherapy: recent advances, challenges, and future prospects. Front Cell Dev Biol [Internet]. 2024 Nov 18 [cited 2025 Nov 12];12. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cell-and-developmental-biology/articles/10.3389/fcell.2024.1491282/full.

- Makker, S.; Galley, C.; Bennett, C.L. Cancer vaccines: from an immunology perspective. immunother advanc. 2024, 4, ltad030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pegram, M.D.; Wu, J.C. Induced pluripotent stem cells as a novel cancer vaccine. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019, 19, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainberg, Z.A.; Weekes, C.D.; Furqan, M.; Kasi, P.M.; Devoe, C.E.; Leal, A.D.; et al. Lymph node-targeted, mKRAS-specific amphiphile vaccine in pancreatic and colorectal cancer: phase 1 AMPLIFY-201 trial final results. Nat Med. 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, E.M.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Weekes, C.D.; Furqan, M.; Kasi, P.M.; Devoe, C.E.; et al. AMPLIFY-201, a first-in-human safety and efficacy trial of adjuvant ELI-002 2P immunotherapy for patients with high-relapse risk with KRAS G12D- or G12R-mutated pancreatic and colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41 (16_suppl), 2528–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, H.; Yang, H.; Li, L.; Ma, J.; Liu, K.; Li, Z. Cancer/testis antigens: promising immunotherapy targets for digestive tract cancers. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2023 June 16 [cited 2025 Nov 12];14. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1190883/full.

- Liu, Z.; Lv, J.; Dang, Q.; Liu, L.; Weng, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Engineering neoantigen vaccines to improve cancer personalized immunotherapy. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2022, 18, 5607–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, N.; Shen, G.; Huang, C.; Zhu, H. Neoantigen-driven personalized tumor therapy: An update from discovery to clinical application. Chinese Medical Journal. 2025, 138, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Mu, X.; et al. Personalised neoantigen-based therapy in colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2023, 13, e1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Porter, F.W.; Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines, a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J.; Jiao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Pan, X.; et al. mRNA vaccines in the context of cancer treatment: from concept to application. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2025, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukutty, P.; Woo, H.Y.; Yoo, S.Y. Therapeutic Colorectal Cancer Vaccines: Emerging Modalities and Translational Opportunities. Vaccines. 2025, 13, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhao, H.; Ma, L.; Shi, Y.; Ji, M.; Sun, X.; et al. The quest for nanoparticle-powered vaccines in cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 2024, 22, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genetic Adjuvants Interleukin-12 and Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor Enhance the Immunogenicity of an Ebola Virus Deoxyribonucleic Acid Vaccine in Mice | The Journal of Infectious Diseases | Oxford Academic [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 15]. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/218/suppl_5/S519/5056373?utm_source=chatgpt.com&login=false.

- Ma, S.X.; Li, L.; Cai, H.; Guo, T.K.; Zhang, L.S. Therapeutic challenge for immunotherapy targeting cold colorectal cancer: A narrative review. World J Clin Oncol. 2023, 14, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, T.; Wang, G. Clinical Application of Adaptive Immune Therapy in MSS Colorectal Cancer Patients. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2021 Oct 13 [cited 2025 Nov 15];12. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.762341/full.

- Predictors of response to immunotherapy in colorectal cancer | The Oncologist | Oxford Academic [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 15]. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/oncolo/article/29/10/824/7699403?utm_source=chatgpt.com&login=false.

- Immunosuppressive cells in cancer: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets | Journal of Hematology & Oncology | Full Text [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 15]. Available online: https://jhoonline.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13045-022-01282-8?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells; mechanisms, functional significance, and targeting in cancer therapy | Cellular Oncology [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 15]. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13402-025-01051-y?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Davern, M.; Donlon, N.E.; O’Connell, F.; Gaughan, C.; O’Donovan, C.; McGrath, J.; et al. Nutrient deprivation and hypoxia alter T cell immune checkpoint expression: potential impact for immunotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023, 149, 5377–5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; Todd, L.; Huang, L.; Noguera-Ortega, E.; Lu, Z.; Huang, L.; et al. Desmoplastic stroma restricts T cell extravasation and mediates immune exclusion and immunosuppression in solid tumors. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, W.; Shen, L.; Yao, Y.; Xia, W.; Ni, C. Tumor battlefield within inflamed, excluded or desert immune phenotypes: the mechanisms and strategies. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yan, G.; Xu, B.; Yu, H.; An, Y.; Sun, M. Evaluating the role of IDO1 macrophages in immunotherapy using scRNA-seq and bulk-seq in colorectal cancer. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2022 Sept 29 [cited 2025 Nov 15];13. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1006501/full.

- Xie, Q.; Liu, X.; Liu, R.; Pan, J.; Liang, J. Cellular mechanisms of combining innate immunity activation with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in treatment of colorectal cancer. Molecular Cancer. 2024, 23, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkoshi, Z. On the Prognostic Power of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes – A Critical Commentary. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2022 May 12 [cited 2025 Nov 16];13. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.892543/full.

- Solis-Castillo, L.A.; Garcia-Romo, G.S.; Diaz-Rodriguez, A.; Reyes-Hernandez, D.; Tellez-Rivera, E.; Rosales-Garcia, V.H.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells, CD8/Treg ratio, and cancer stem cells are correlated with lymph node metastasis in patients with early breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2020, 27, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Tang, J.; Cao, M. Radiotherapy induced immunogenic cell death by remodeling tumor immune microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1074477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Li, T.; Niu, M.; Mei, Q.; Zhao, B.; Chu, Q.; et al. Exploiting innate immunity for cancer immunotherapy. Molecular Cancer. 2023, 22, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.N.; Luo, W.; Sun, C.; Jin, Z.; Zeng, X.; Alexander, P.B.; et al. Radiation-induced eosinophils improve cytotoxic T lymphocyte recruitment and response to immunotherapy. Sci Adv. 2021, 7, eabc7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, B.; Li, B.; Wu, H.; Jiang, M. Cold and hot tumors: from molecular mechanisms to targeted therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Zhou, K.; Lei, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, H. Cancer vaccines: platforms and current progress. Mol Biomed. 2025, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna Jr, M.G. Immunotherapy with autologous tumor cell vaccines for treatment of occult disease in early stage colon cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012, 8, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyl-de Groot, C.A.; Vermorken, J.B.; Hanna, M.G.; Verboom, P.; Groot, M.T.; Bonsel, G.J.; et al. Immunotherapy with autologous tumor cell-BCG vaccine in patients with colon cancer: a prospective study of medical and economic benefits. Vaccine. 2005, 23, 2379–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemunaitis, J.; Stanbery, L.; Walter, A.; Wallraven, G.; Nemunaitis, A.; Horvath, S.; et al. Gemogenovatucel-T (Vigil): bi-shRNA plasmid-based targeted immunotherapy. Future Oncol. 20, 2149–2164. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dörrie, J.; Schaft, N.; Schuler, G.; Schuler-Thurner, B. Therapeutic Cancer Vaccination with Ex Vivo RNA-Transfected Dendritic Cells,An Update. Pharmaceutics. 2020, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D. The Application of Dendritic Cells Vaccines in Tumor Therapy and Their Combination with Biomimetic Nanoparticles. Vaccines. 2025, 13, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhhasan, M.; Ahmadieh-Yazdi, A.; Heidari, R.; Chamanara, M.; Akbari, M.; Poondla, N.; et al. Revolutionizing cancer treatment: The power of dendritic cell-based vaccines in immunotherapy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2025, 184, 117858. [Google Scholar]

- Wainberg, Z.A.; Weekes, C.D.; Furqan, M.; Kasi, P.M.; Devoe, C.E.; Leal, A.D.; et al. Lymph node-targeted, mKRAS-specific amphiphile vaccine in pancreatic and colorectal cancer: phase 1 AMPLIFY-201 trial final results. Nat Med. 2025, 31, 3648–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, N.; Urschbach, M.; Gabba, A.; Schmitt, E.; Kunz, H.; Besenius, P. The Development of Vaccines from Synthetic Tumor-Associated Mucin Glycopeptides and their Glycosylation-Dependent Immune Response. The Chemical Record. 2021, 21, 3313–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.M.; Mehta, V.; Finn, O.J. Three Different Vaccines Based on the 140-Amino Acid MUC1 Peptide with Seven Tandemly Repeated Tumor-Specific Epitopes Elicit Distinct Immune Effector Mechanisms in Wild-Type Versus MUC1-Transgenic Mice with Different Potential for Tumor Rejection1. J Immunol. 2001, 166, 6555–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ma, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, B.; Qiao, D.; Ren, P.; et al. Current advances in cancer vaccines targeting NY-ESO-1 for solid cancer treatment. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2023 Sept 5 [cited 2025 Nov 16];14. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1255799/full.

- Mayer, L.; Weskamm, L.M.; Fathi, A.; Kono, M.; Heidepriem, J.; Krähling, V.; et al. MVA-based vaccine candidates encoding the native or prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spike reveal differential immunogenicity in humans. NPJ Vaccines. 2024, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, D.L.; Liu, Z.; Sathaiah, M.; Ravindranathan, R.; Guo, Z.; He, Y.; et al. Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Mol Cancer. 2013, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baljon, J.J.; Kwiatkowski, A.J.; Pagendarm, H.M.; Stone, P.T.; Kumar, A.; Bharti, V.; et al. A Cancer Nanovaccine for Co-Delivery of Peptide Neoantigens and Optimized Combinations of STING and TLR4 Agonists. ACS Nano. 2024, 18, 6845–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Baldwin, J.; Brar, D.; Salunke, D.B.; Petrovsky, N. Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists as a driving force behind next-generation vaccine adjuvants and cancer therapeutics. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2022, 70, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturki, N.A. Review of the Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in the Context of Cancer Treatment. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Han, Z.; Ma, D. Immune checkpoint therapy for solid tumours: clinical dilemmas and future trends. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, A.; Puglisi, S.; Pirrone, C.; Martelli, V.; Catalano, F.; Nardin, S.; et al. The role of immunotherapy in microsatellites stable metastatic colorectal cancer: state of the art and future perspectives. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1161048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ResearchGate [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 16]. (PDF) Whole tumor cell vaccine adjuvants: Comparing IL-12 to IL-2 and IL-15. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308725229_Whole_tumor_cell_vaccine_adjuvants_Comparing_IL-12_to_IL-2_and_IL-15.

- Rahman, T.; Das, A.; Abir, M.H.; Nafiz, I.H.; Mahmud, A.R.; Sarker, M.d.R.; et al. Cytokines and their role as immunotherapeutics and vaccine Adjuvants: The emerging concepts. Cytokine. 2023, 169, 156268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principe, D.R.; Kamath, S.D.; Korc, M.; Munshi, H.G. The immune modifying effects of chemotherapy and advances in chemo-immunotherapy. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2022, 236, 108111. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Liu, W.Q.; Broussy, S.; Han, B.; Fang, H. Recent advances of anti-angiogenic inhibitors targeting VEGF/VEGFR axis. Front Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1307860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.; Manavi, M.S.; Afshinpour, M.; Khorram, R.; Vafadar, R.; Rezaei-Tazangi, F.; et al. Emerging immunologic approaches as cancer anti-angiogenic therapies. Clin Transl Oncol. 2025, 27, 1406–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.M.; Redman, J.M.; Gulley, J.L. Combining vaccines and immune checkpoint inhibitors to prime, expand, and facilitate effective tumor immunotherapy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018, 17, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elicio Therapeutics. First in Human Phase 1 Trial of ELI-002 Immunotherapy as Treatment for Subjects With Kirsten Rat Sarcoma (KRAS) Mutated Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Other Solid Tumors [Internet]. clinicaltrials.gov; 2025 Aug [cited 2025 Nov 16]. Report No.: NCT04853017. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04853017.

- Wang, A.Y.L.; Aviña, A.E.; Liu, Y.Y.; Kao, H.K. Pluripotent Stem Cells: Recent Advances and Emerging Trends. Biomedicines. 2025, 13, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerneckis, J.; Cai, H.; Shi, Y. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs): molecular mechanisms of induction and applications. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzmich, N.N.; Sivak, K.V.; Chubarev, V.N.; Porozov, Y.B.; Savateeva-Lyubimova, T.N.; Peri, F. TLR4 Signaling Pathway Modulators as Potential Therapeutics in Inflammation and Sepsis. Vaccines (Basel). 2017, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinthareddy, A.; Oroszi, T. Exploration of Kras Mutations and Their Potential for Being a Target Molecule in Cancer Chemotherapy. Journal of Cancer Therapy. 2023, 14, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, P.F.; Pala, L.; Conforti, F.; Cocorocchio, E. Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC): An Intralesional Cancer Immunotherapy for Advanced Melanoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Telli, M.L.; Wu, J.C. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cancer Vaccines. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2019 July 8 [cited 2025 Nov 17];10. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01510/full.

- Chehelgerdi, M.; Behdarvand Dehkordi, F.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Kabiri, H.; Salehian-Dehkordi, H.; Abdolvand, M.; et al. Exploring the promising potential of induced pluripotent stem cells in cancer research and therapy. Mol Cancer. 2023, 22, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiner, Z.S.; Talib, S.; Feigal, E.G. The Potential for Immunogenicity of Autologous Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-derived Therapies *. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014, 289, 4571–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; La Shu, S.; Rio-Espinola, A.D.; Ferreira, J.R.; Bando, K.; Lemmens, M.; et al. Evaluating teratoma formation risk of pluripotent stem cell-derived cell therapy products: a consensus recommendation from the Health and Environmental Sciences Institute’s International Cell Therapy Committee. Cytotherapy. 2025, 27, 1072–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, M.; Sumen, C.; Aivio, S.; Saklayen, N. Autologous Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cell Therapies: Promise, Progress, and Challenges. Curr Protoc. 2021, 1, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Sarabi, P.; Rismani, E.; Shabanpouremam, M.; Hendi, Z.; Nikoubin, B.; Rahimi, S.; et al. Hypoimmunogenic pluripotent stem cells: A game-changer in cell-based regenerative medicine. International Immunopharmacology. 2025, 162, 115134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, M.; Lakshmipathy, U.; Zhang, X.; Bharti, K.; Wall, D.M.; Sato, Y.; et al. Considerations for the development of iPSC-derived cell therapies: a review of key challenges by the JSRM-ISCT iPSC Committee. Cytotherapy. 2024, 26, 1382–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, C.E.; Rivera, T.A.; Soto, C.A.; Deeks, T.; Kalergis, A.M. Current GMP standards for the production of vaccines and antibodies: An overview. Front Public Health. 2022, 10, 1021905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocki, F.; van der Stegen, S.J.C.; Miller, J.S. Engineered and banked iPSCs for advanced NK- and T-cell immunotherapies. Blood. 2023, 141, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Dong, P.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J. Advances in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Natural Killer Cell Therapy. Cells. 2024, 13, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Li, W. ‘Off the shelf’ immunotherapies: Generation and application of pluripotent stem cell-derived immune cells. Cell Prolif. 2023, 56, e13425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roybal, K.T.; Lim, W.A. Synthetic Immunology: Hacking Immune Cells to Expand Their Therapeutic Capabilities. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017, 35, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.; Allen, A.; Luo, C.; Finn, J.D. Unlocking the potential of iPSC-derived immune cells: engineering iNK and iT cells for cutting-edge immunotherapy. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2024 Aug 30 [cited 2025 Nov 17];15. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1457629/full.

- Márquez, P.G.; Wolman, F.J.; Glisoni, R.J. Nanotechnology platforms for antigen and immunostimulant delivery in vaccine formulations. Nano Trends. 2024, 8, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, M.; Fadaee Dowlat, B.; Yaghmayee, S.; Habibian, A.; Keshavarzi, S.; Oksenych, V.; et al. Next-Generation Vaccine Platforms: Integrating Synthetic Biology, Nanotechnology, and Systems Immunology for Improved Immunogenicity. Vaccines (Basel). 2025, 13, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.E.; White, J.M.; Viola, N.T.; Gibson, H.M. In vivo Imaging Technologies to Monitor the Immune System. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; Teke, J.; Fapohunda, O.; Weerasinghe, K.; Usman, S.O.; Ige, A.O.; et al. Leveraging artificial intelligence in vaccine development: A narrative review. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2024, 224, 106998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururaj, A.E.; Scheuermann, R.H.; Lin, D. AI and immunology as a new research paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2024, 25, 1993–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guan, H.; Feng, X.; Liu, M.; Shao, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Emerging strategies in colorectal cancer immunotherapy: enhancing efficacy and survival. Front Immunol. 2025, 16, 1616414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steup, C.; Kennel, K.B.; Neurath, M.F.; Fichtner-Feigl, S.; Greten, F.R. Current and emerging concepts for systemic treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. 2025 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Nov 17]. Available online: https://gut.bmj.com/content/74/12/2070.

| Antigen / Target | Type / Class | Prevalence in CRC | Vaccine Strategy / Relevance |

| NY-ESO-1 | Cancer-testis antigen (CTA) | 10–20 % of CRCs; serum antibody ≈ 10 % | Used in peptide and DC vaccines; highly immunogenic; often combined with CEA / MUC1 for broader coverage [70,71]. |

| MAGE-A3 / MAGE-A4 | CTA | 5–15 % | Tested in multi-epitope peptide constructs; limited single-antigen efficacy; promising for combination vaccines [71,72]. |

| DKKL1 (Dickkopf-like 1) | CTA | Overexpressed; absent in normal colon | Identified as novel CRC antigen via immunoinformatics; CTL epitopes validated in vitro; suitable for peptide/DC vaccines [73]. |

| FBXO39 | CTA | Elevated in CRC tissues | Incorporated in in-silico multi-epitope constructs; elicits human CTL activation [73]. |

| OIP5 (Opa-interacting protein 5) | CTA | Frequently upregulated in CRC | Immunogenic in vitro; included in composite CTA vaccine designs [73]. |

| Mutant KRAS (G12D/V) | Neoantigen | ~50 % of metastatic CRC | Validated by ELI-002 trial; induced durable CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ responses; correlated with improved RFS/OS [71,72]. |

| Personalized neoantigens | Neoantigen | Rare in MSS; abundant in MSI-H | Basis for individualized mRNA or peptide vaccines; early clinical testing ongoing [71]. |

| CEA (Carcinoembryonic antigen) | Oncofetal glycoprotein | Highly expressed (>80 % CRC) | Central biomarker and vaccine target; peptides less immunogenic alone; used with GM-CSF or viral vectors [71,72]. |

| MUC1 (aberrant glycoform) | Oncofetal glycoprotein | Widely expressed | Studied in peptide/DC vaccines; moderate efficacy; potential preventive use in adenoma recurrence [71,72]. |

| Study (Year) | Cancer Model | iPSC Source / Adjuvant | Key Experimental Findings |

| Kooreman et al. (2018, Cell Stem Cell) | Murine melanoma, breast carcinoma, mesothelioma | Autologous mouse iPSCs; CpG (TLR9 agonist) | Prophylactic vaccination prevented tumor growth in ~60 % of mice; induced strong CD8⁺ cytotoxic T-cell and antibody responses; adoptive transfer of T cells from vaccinated mice conferred protection; demonstrated cross-reactivity between iPSC and tumor antigens [37]. |

| Ouyang et al. (2021, Stem Cell Reports) | Murine pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) | Autologous mouse iPSCs; CpG adjuvant | 75 % of vaccinated mice rejected tumors completely; vaccine elicited robust effector/memory CD8⁺ T cells and humoral immunity; reduced intratumoral FoxP3⁺ Tregs and MDSCs; prolonged survival in adjuvant (post-surgical) setting [36]. |

| Huang et al. (2024, Cancer Immunol Res) | Microsatellite-stable (MSS) colorectal carcinoma and TNBC | Autologous iPSCs engineered with eight CT26 neoantigens via AAV; combined with focal radiotherapy | iPSC + RT yielded ~60 % complete regression vs <10 % with single modality; generated strong neoantigen-specific CD8⁺ T-cell responses, high IFN-γ / granzyme B expression, and reduced metastasis; validated synergy between iPSC vaccination and RT-induced antigen release [75]. |

| Jwo et al. (2025, Nat Commun, preclinical) | Murine colorectal carcinoma (CT26, MC38) | Autologous iPSCs; CpG adjuvant | Demonstrated both prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy; increased tumor-infiltrating CD8⁺ cells, elevated IFN-γ; identified shared antigens HNRNPU and NCL as dominant targets; peptide vaccines against these antigens reproduced cytotoxic and memory responses [26]. |

| Multiple groups (2000s–2020s) | Melanoma, lung, ovarian, colon models | Allogeneic/ syngeneic ESCs or iPSCs ± CpG, poly(I:C), GM-CSF | Proof-of-concept studies established pluripotent stem cells as broad antigen sources; antitumor efficacy observed only with potent adjuvants or in combination with checkpoint blockade, highlighting need for multi-modal design [149,150]. |

| Strategy / Agent | Primary TME Target | Mechanism / Functional Effect | Representative Example / Status |

| TLR agonists (CpG, poly(I:C)) | Dendritic cells / macrophages | Activate innate sensors → type I IFN + IL-12 release; promote cross-presentation and Th1 polarization. | CpG used in iPSC vaccine protocols; multiple TLR agonists in clinical testing as adjuvants [138]. |

| Checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4) | Exhausted T cells | Block inhibitory signaling → restore effector function; synergize with vaccines by sustaining T-cell activity. | Approved for MSI-H CRC; trials ongoing in MSS CRC with vaccine combination [86,140,147]. |

| TLR2/4 agonists (MPLA, poly-ICLC) | APC activation | Trigger NF-κB and IRF pathways; enhance antigen presentation; safe adjuvants. | MPLA used in HPV vaccine (Cervarix); adapted for experimental cancer vaccines [137,138,151]. |

| Cytokines (GM-CSF, IL-2, IL-12, IL-15) | DCs / T cells / NK cells | Recruit and activate APCs and effector cells; strengthen cytotoxic responses. | GM-CSF in GVAX and iPSC vaccines; IL-12/IL-15 potent but dose-limited clinically [142,143]. |

| Radiotherapy (RT) | Tumor cells and vasculature | Induces immunogenic cell death, increases MHC I expression, releases DAMPs; normalizes vasculature. | Synergy demonstrated in NA-iPSC + RT CRC model; clinical validation underway [78,120]. |

| Chemotherapy (Oxaliplatin, Cyclophosphamide) | Tumor + immune cells | Oxaliplatin triggers immunogenic death; low-dose cyclophosphamide transiently depletes Tregs. | Combined in CRC vaccine trials to enhance immune priming [144,152]. |

| Anti-angiogenic therapy (Bevacizumab) | Tumor vasculature / hypoxia | Normalizes vessels, increases T-cell infiltration, reduces MDSCs. | Widely used in metastatic CRC; under evaluation with vaccines + ICI [145,146]. |

| Oncolytic viruses (T-VEC, AdV, VV) | Tumor cells and innate pathways | Cause direct tumor lysis and release neoantigens; viral PAMPs activate STING / TLR. | T-VEC approved for melanoma; engineered adenoviral/vaccinia vectors in CRC Phase I [136,153] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).