Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Methods

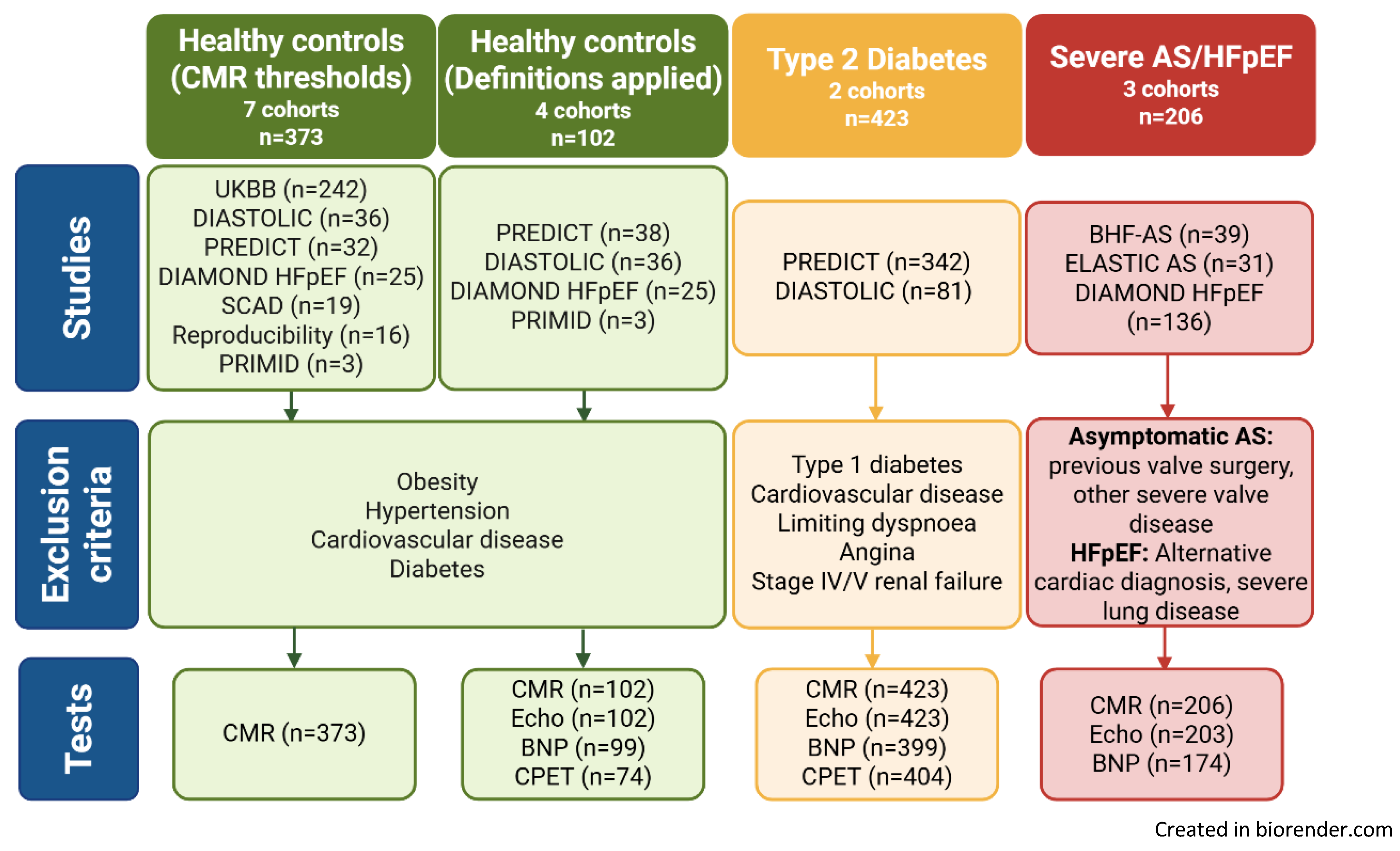

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Assessments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Cohorts

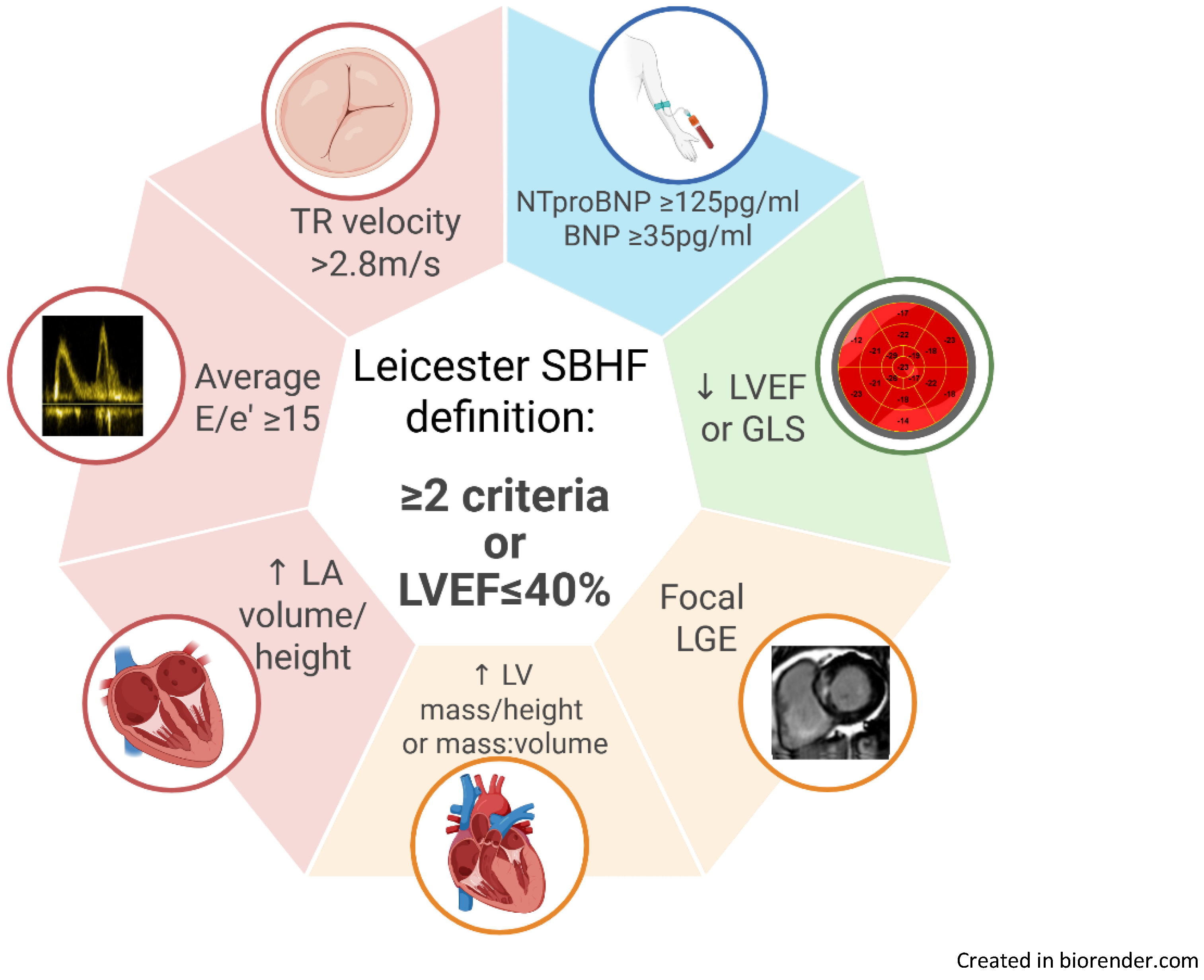

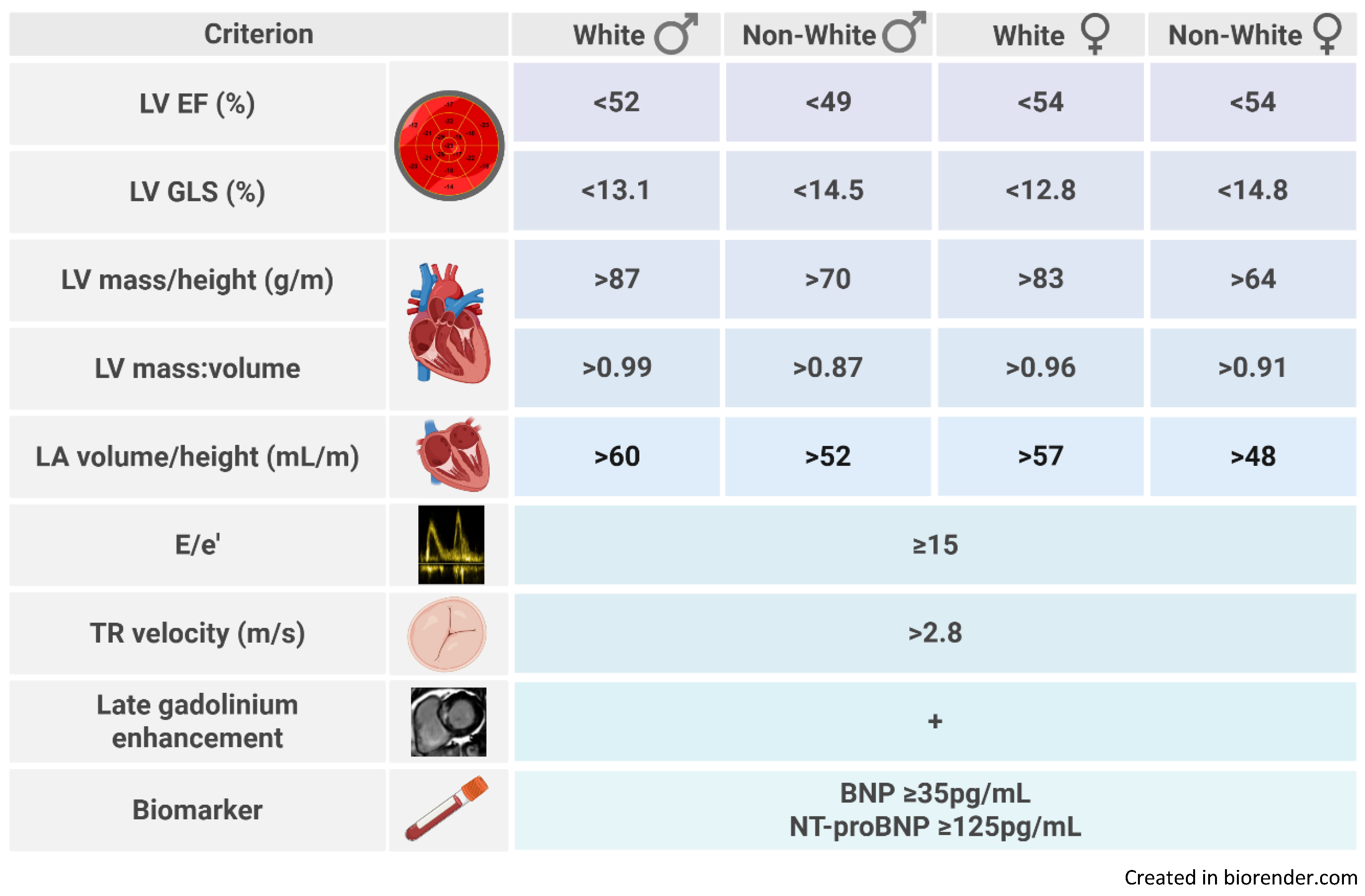

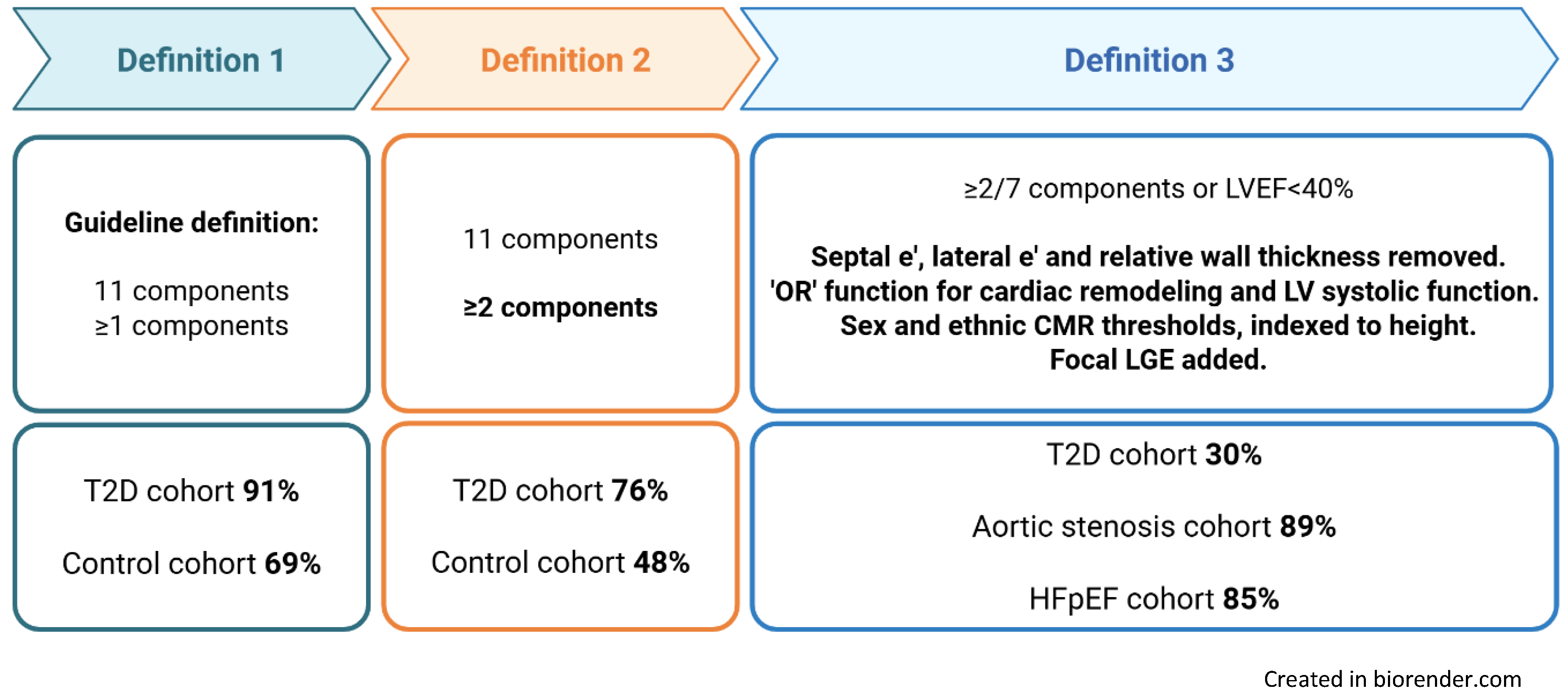

3.2. Prevalence of Stage B Heart Failure by Definition

3.3. Comparison of Characteristics Between Stage A and B Heart Failure in the Type 2 Diabetes Cohort

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| AS | Aortic stenosis |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CMR | Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| CPET | Cardiopulmonary exercise testing |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| HC | Healthy controls |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFSA | Heart failure society of America |

| LGE | Late gadolinium enhancement |

| LV | Left ventricular |

| SBHF | Stage B heart failure |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

References

- Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic P, Rosano GMC, Coats AJS. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovascular Research. 2023;118(17):3272-87. [CrossRef]

- Foundation, BH. Heart Statistics: British Heart Foundation; 2024 [Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/our-research/heart-statistics.

- Wang H, Gao C, Guignard-Duff M, Cole C, Hall C, Baruah R, et al. Inpatient versus outpatient diagnosis of heart failure across the spectrum of ejection fraction: a population cohort study. Heart. 2025;111(11):523-31. [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895-e1032.

- Wang TJ, Evans JC, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Leroy EC, Vasan RS. Natural History of Asymptomatic Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction in the Community. Circulation. 2003;108(8):977-82. [CrossRef]

- Young KA, Scott CG, Rodeheffer RJ, Chen HH. Progression of Preclinical Heart Failure: A Description of Stage A and B Heart Failure in a Community Population. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2021;14(5).

- HSCI, C. Are diabetes services in England and Wales Measuring up? National Diabetes Audit 2011-12. In: HSCI C, editor. 2011-2012.

- Rawshani A, Rawshani A, Franzén S, Sattar N, Eliasson B, Svensson A-M, et al. Risk Factors, Mortality, and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(7):633-44. [CrossRef]

- Khan H, Kunutsor S, Rauramaa R, Savonen K, Kalogeropoulos AP, Georgiopoulou VV, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of heart failure: a population-based follow-up study. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2014;16(2):180-8.

- Sarullo FM, Fazio G, Brusca I, Fasullo S, Paterna S, Licata P, et al. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: Prognostic Comparison from Peak VO2 and VE/VCO2 Slope. The Open Cardiovascular Medicine Journal. 2010;4(1):127-34.

- Gürdal A, Kasikcioglu E, Yakal S, Bugra Z. Impact of diabetes and diastolic dysfunction on exercise capacity in normotensive patients without coronary artery disease. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2015;12(3):181-8.

- Segerström Å B, Elgzyri T, Eriksson KF, Groop L, Thorsson O, Wollmer P. Exercise capacity in relation to body fat distribution and muscle fibre distribution in elderly male subjects with impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and matched controls. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(1):57-63. [CrossRef]

- Kiencke S, Handschin R, von Dahlen R, Muser J, Brunner-Larocca HP, Schumann J, et al. Pre-clinical diabetic cardiomyopathy: prevalence, screening, and outcome. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12(9):951-7.

- Wang Y, Yang H, Huynh Q, Nolan M, Negishi K, Marwick TH. Diagnosis of Nonischemic Stage B Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Optimal Parameters for Prediction of Heart Failure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(10):1390-400.

- Oo MM, Tan Chung Zhen I, Ng KS, Tan KL, Tan ATB, Vethakkan SR, et al. Observational study investigating the prevalence of asymptomatic stage B heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes who are not known to have coronary artery disease. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e039869.

- Ferreira VM, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, Kramer CM, Carbone I, Sechtem U, et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Nonischemic Myocardial Inflammation: Expert Recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(24):3158-76.

- Parke KS, Brady EM, Alfuhied A, Motiwale RS, Razieh CS, Singh A, et al. Ethnic differences in cardiac structure and function assessed by MRI in healthy South Asian and White European people: A UK Biobank Study. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2024;26(1):100001.

- Yeo JL, Dattani A, Bilak JM, Wood AL, Athithan L, Deshpande A, et al. Sex differences and determinants of coronary microvascular function in asymptomatic adults with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2025;27(1):101132. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Greenwood JP, Berry C, Dawson DK, Hogrefe K, Kelly DJ, et al. Comparison of exercise testing and CMR measured myocardial perfusion reserve for predicting outcome in asymptomatic aortic stenosis: the PRognostic Importance of MIcrovascular Dysfunction in Aortic Stenosis (PRIMID AS) Study. European Heart Journal. 2017;38(16):1222-9.

- Kanagala P, Arnold JR, Singh A, Khan JN, Gulsin GS, Gupta P, et al. Prevalence of right ventricular dysfunction and prognostic significance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;37(1):255-66.

- Gulsin GS, Swarbrick DJ, Athithan L, Brady EM, Henson J, Baldry E, et al. Effects of Low-Energy Diet or Exercise on Cardiovascular Function in Working-Age Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective, Randomized, Open-Label, Blinded End Point Trial. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(6):1300-10. [CrossRef]

- Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) study ISRCTN registry2019 [updated 22/07/2025. Available from: https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN42661582.

- Ayton SL, Alfuhied A, Gulsin GS, Parke KS, Wormleighton JV, Arnold JR, et al. The Interfield Strength Agreement of Left Ventricular Strain Measurements at 1.5 T and 3 T Using Cardiac MRI Feature Tracking. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2023;57(4):1250-61.

- Steadman CD, Jerosch-Herold M, Grundy B, Rafelt S, Ng LL, Squire IB, et al. Determinants and functional significance of myocardial perfusion reserve in severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(2):182-9.

- Yeo JL, Gulsin GS, Dattani A, Ayton SL, Bilak JM, Parke KS, et al. Unmasking early diastolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes using the peak early-to-late diastolic strain rate ratio by cardiac MRI feature tracking. European Heart Journal. 2022;43(Supplement_2). [CrossRef]

- Captur G, Lobascio I, Ye Y, Culotta V, Boubertakh R, Xue H, et al. Motion-corrected free-breathing LGE delivers high quality imaging and reduces scan time by half: an independent validation study. The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2019;35(10):1893-901.

- Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2015;28(1):1-39.e14.

- Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2016;29(4):277-314.

- Wasserman K, Hansen J, Sue DY, Stringer W, Sietsema K, Sun X-G, Whipp BJ. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation: Including pathophysiology and clinical applications: Fifth edition2011. 1-592 p.

- Sietsema KE, Stringer WW, Sue DY, Ward S. Wasserman & Whipp's: principles of exercise testing and interpretation: including pathophysiology and clinical applications: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020.

- Wasserman, K. Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation: Including Pathophysiology and Clinical Applications: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. College Station: TX: StataCorp LLC; 2023.

- Horowitz, GL. Estimating reference intervals. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133(2):175-7.

- Mohebi R, Wang D, Lau ES, Parekh JK, Allen N, Psaty BM, et al. Effect of 2022 ACC/AHA/HFSA Criteria on Stages of Heart Failure in a Pooled Community Cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(23):2231-42.

- Chahal H, Bluemke DA, Wu CO, McClelland R, Liu K, Shea SJ, et al. Heart failure risk prediction in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Heart. 2015;101(1):58-64.

- Petersen SE, Aung N, Sanghvi MM, Zemrak F, Fung K, Paiva JM, et al. Reference ranges for cardiac structure and function using cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) in Caucasians from the UK Biobank population cohort. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2016;19(1):18.

- Yang W, Xu J, Zhu L, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Zhao S, Lu M. Myocardial Strain Measurements Derived From MR Feature-Tracking. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2024;17(4):364-79.

- Raisi-Estabragh Z, Szabo L, McCracken C, Bülow R, Aquaro GD, Andre F, et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Reference Ranges From the Healthy Hearts Consortium. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2024;17(7):746-62. [CrossRef]

- Gottdiener JS, Kitzman DW, Aurigemma GP, Arnold AM, Manolio TA. Left Atrial Volume, Geometry, and Function in Systolic and Diastolic Heart Failure of Persons ≥65 Years of Age (The Cardiovascular Health Study). The American Journal of Cardiology. 2006;97(1):83-9.

- Reimer Jensen AM, Zierath R, Claggett B, Skali H, Solomon SD, Matsushita K, et al. Association of Left Ventricular Systolic Function With Incident Heart Failure in Late Life. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(5):509-20.

- Subramanian V, Keshvani N, Segar MW, Kondamudi NJ, Chandra A, Maddineni B, et al. Association of global longitudinal strain by feature tracking cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with adverse outcomes among community-dwelling adults without cardiovascular disease: The Dallas Heart Study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024;26(2):208-15.

- Velagaleti RS, Gona P, Pencina MJ, Aragam J, Wang TJ, Levy D, et al. Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Patterns and Incidence of Heart Failure With Preserved Versus Reduced Ejection Fraction. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2014;113(1):117-22. [CrossRef]

- Taqueti VR, Solomon SD, Shah AM, Desai AS, Groarke JD, Osborne MT, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and future risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(10):840-9.

- Marques MD, Weinberg R, Kapoor S, Ostovaneh MR, Kato Y, Liu CY, et al. Myocardial fibrosis by T1 mapping magnetic resonance imaging predicts incident cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging. 2022;23(10):1407-16.

- Shah AM, Claggett B, Sweitzer NK, Shah SJ, Anand IS, O’Meara E, et al. Cardiac Structure and Function and Prognosis in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2014;7(5):740-51.

- Shahim A, Hourqueig M, Donal E, Oger E, Venkateshvaran A, Daubert JC, et al. Predictors of long-term outcome in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a follow-up from the KaRen study. ESC Heart Failure. 2021;8(5):4243-54. [CrossRef]

- Gerstenblith G, Frederiksen J, Yin FC, Fortuin NJ, Lakatta EG, Weisfeldt ML. Echocardiographic assessment of a normal adult aging population. Circulation. 1977;56(2):273-8.

- Lee DS, Massaro JM, Wang TJ, Kannel WB, Benjamin EJ, Kenchaiah S, et al. Antecedent Blood Pressure, Body Mass Index, and the Risk of Incident Heart Failure in Later Life. Hypertension. 2007;50(5):869-76.

- Davis EF, Crousillat DR, He W, Andrews CT, Hung JW, Danik JS. Indexing Left Atrial Volumes: Alternative Indexing Methods Better Predict Outcomes in Overweight and Obese Populations. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(6):989-97.

- Caballero L, Kou S, Dulgheru R, Gonjilashvili N, Athanassopoulos GD, Barone D, et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal cardiac Doppler data: results from the NORRE Study. European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging. 2015. [CrossRef]

| Clinical characteristics | Healthy controls (n=102) |

Type 2 diabetes (n=423) |

Aortic stenosis (n=70) |

HFpEF (n=136) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59 ± 11 | 61 ± 9 | 70 (62, 74) | 74 (67, 78) |

| Male sex | 49 (48%) | 258 (61%) | 53 (76%) | 67 (49%) |

| White ethnicity | 75 (74%) | 311 (74%) | 64 (91%) | 114 (84%) |

| Current or ex-smoker | 27 (26%) | 187 (44%) | 44 (63%) | 72 (53%) |

| Hypertensive | - | 240 (57%) | 47 (67%) | 123 (90%) |

| T2D duration (years) | - | 10 (5, 21) | - | - |

| Statin | 12 (12%) | 292 (69%) | 49 (72%) | 86 (63%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.5 ± 2.2 | 31.5 ± 6.2 | 29.9 ± 5.3 | 33.8 ± 7.0 |

| Clinic systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 133 ± 22 | 137 ± 17 | 136 ± 22 | 145 ± 25 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 65 ± 10 | 76 ± 12 | 67 ± 14 | 67 ± 14 |

| Glycosylated haemoglobin (%) | - | 7.3 ± 1.2 | - | 6.2 (5.7, 7.3) |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.732) | 87 ± 12 | 87 ± 15 | 75 ± 17 | 64 ± 21 |

| Maximum workload (W)* | 142 (100, 200) | 115 (87, 150) | - | - |

| Peak VO2 (mL/Kg/min)* | 25.5 ± 7.6 | 19.0 ± 5.2 | - | - |

| % predicted workload* | 124 ± 32 | 100 ± 25 | - | - |

| % predicted VO2 Max* | 97 ± 21 | 88 ± 20 | - | - |

| Definition 1 Current ACC/AHA/HFSA |

Definition 2 ≥2 ACC/AHA/HFSA criteria |

Definition 3 ≥2 criteria or LVEF ≤40% |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stage A n=37 |

Stage B n=386 |

P |

Stage A n=101 |

Stage B n=322 |

P |

Stage A n=295 |

Stage B n=128 |

P | |||

| Age, years | 58 ± 7 | 61 ± 9 | 0.028 | 58 ± 9 | 62 ± 8 | <0.001 | 62 ± 8 | 59 ± 10 | 0.002 | ||

| Male sex | 25 (68%) | 233 (60%) | 0.391 | 59 (58%) | 199 (62%) | 0.543 | 172 (58%) | 86 (67%) | 0.085 | ||

| White ethnicity | 27 (73%) | 284 (74%) | 0.937 | 77 (76%) | 234 (73%) | 0.478 | 227 (77%) | 84 (66%) | 0.015 | ||

| Current/ex-smoker | 15 (41%) | 172 (45%) | 0.638 | 38 (38%) | 149 (46%) | 0.127 | 119 (40%) | 68 (53%) | 0.015 | ||

| Hypertensive | 20 (54%) | 220 (57%) | 0.730 | 52 (51%) | 188 (58%) | 0.222 | 161 (55%) | 79 (62%) | 0.173 | ||

| T2D duration, years | 6 (3, 11) | 8 (5, 12) | 0.274 | 5 (3, 10) | 8 (5, 13) | 0.002 | 8 (5, 13) | 6 (4, 11) | 0.067 | ||

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 29.5 ± 5.6 | 31.7 ± 6.2 | 0.036 | 30.3 ± 6.5 | 31.9 ± 6.0 | 0.019 | 30.3 ± 5.5 | 34.2 ± 6.9 | <0.001 | ||

| Average SBP, mmHg | 130 ± 13 | 137 ± 17 | 0.013 | 131 (15) | 138 (17) | <0.001 | 134 (15) | 143 ± 18 | <0.001 | ||

| HbA1c, % | 7.5 ± 1.4 | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 0.242 | 7.2 ± 1.2 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 0.211 | 7.3 ± 1.2 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | 0.360 | ||

| Exercise capacity | |||||||||||

| % predicted workload* | 91 ± 19 | 101 ± 25 | 0.015 | 98 ± 25 | 101 ± 25 | 0.297 | 104 ± 26 | 93 ± 21 | <0.001 | ||

| % predicted VO2 Max* | 83 ± 17 | 88 ± 20 | 0.102 | 88 ± 19 | 88 ± 20 | 0.794 | 91 ± 20 | 81 ± 16 | <0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).