1. Introduction

The continuous growth of large-scale astronomical surveys has generated an unprecedented volume of time-series data, enabling new discoveries across stellar physics, exoplanet detection, and cosmology. Modern observatories such as Kepler, TESS, and the forthcoming Vera Rubin Observatory (LSST) collect high-cadence observations for millions of celestial sources. This exponential increase in data availability demands robust statistical frameworks that can model, interpret, and infer the underlying astrophysical processes efficiently and accurately. However, traditional probabilistic modeling techniques struggle to scale computationally when applied to these massive datasets.

Gaussian Processes (GPs) have emerged as a powerful, flexible class of non-parametric models that capture correlations and uncertainties in data through their covariance functions. In astrophysical contexts, GPs have been widely used to characterize stellar variability, model correlated instrumental noise, reconstruct exoplanet transits, and analyze the cosmic microwave background. Despite their versatility, the major limitation of standard GP implementations lies in their computational complexity, which scales cubically with the number of observations () and quadratically in memory (). This scaling renders conventional GP analysis impractical for modern astronomical datasets that often include tens or hundreds of thousands of measurements per target.

Several efforts have been made to mitigate this computational bottleneck. Approaches such as sparse approximations, inducing point methods, and structured kernel interpolations reduce the computational cost, but often at the expense of model fidelity or interpretability. These approximations introduce biases or rely on specific assumptions about data regularity, which are not always valid for irregularly sampled astronomical observations with heterogeneous uncertainties. Consequently, there remains a critical need for a scalable, mathematically rigorous GP framework that preserves model exactness while achieving near-linear computational performance.

In response to this challenge, this paper introduces an efficient and exact Gaussian Process modeling technique, termed celerite, designed specifically for one-dimensional time series data. The method exploits the semiseparable structure of covariance matrices that arise when the kernel is represented as a mixture of complex exponentials. By leveraging this structure, the computational complexity of GP inference is reduced from cubic to linear time, enabling the analysis of datasets that were previously computationally intractable. Unlike traditional approximations, the celerite framework achieves exact inference under its class of kernels, making it both scalable and theoretically consistent.

The celerite method provides a physically interpretable modeling paradigm for stochastic processes that can be expressed as mixtures of damped harmonic oscillators. This connection offers a strong physical basis for modeling stellar variability, oscillations, and rotational modulations—phenomena that naturally exhibit quasi-periodic behavior. Furthermore, the algorithm supports irregular time sampling and heteroscedastic noise, conditions common in astrophysical observations. These properties make celerite particularly well-suited for analyzing photometric and spectroscopic data from space- and ground-based missions.

In this work, we present a comprehensive exploration of the celerite methodology and its application to real and simulated astronomical datasets. The key contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We derive a novel linear-time Gaussian Process solver for one-dimensional datasets that exploits the semiseparable structure of covariance matrices formed by exponential kernel mixtures.

We provide a physically motivated interpretation of the celerite kernel as a model of stochastically driven damped harmonic oscillators, linking statistical inference with astrophysical dynamics.

We demonstrate the algorithm’s accuracy, scalability, and interpretability through applications to stellar rotation analysis, asteroseismic oscillation modeling, and exoplanet transit fitting.

We release open-source implementations of the proposed method in Python, C++, and Julia to facilitate adoption across the astrophysical community.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section II reviews related work in Gaussian Process modeling and scalable inference techniques. Section III details the mathematical foundation of the proposed celerite framework, including its covariance structure and computational optimization. Section IV discusses the implementation aspects and algorithmic improvements. Section V presents experimental results on both synthetic and real datasets. Section VI provides an analytical discussion of the findings, while Section VII concludes with key insights and outlines future research directions in scalable probabilistic modeling for astronomy.

2. Related Work

Gaussian Processes (GPs) have long served as a foundational framework for probabilistic modeling in astrophysics and other scientific domains, primarily due to their flexibility in representing complex stochastic phenomena and their capacity to quantify uncertainty in predictions. The relevance of GPs extends across numerous astrophysical applications, including stellar variability modeling [

1], cosmic microwave background analysis [

2], and exoplanet transit fitting [

3]. Despite their conceptual elegance, the cubic computational scaling of conventional GP models with respect to dataset size has historically restricted their use in large-scale astronomical analyses [

4].

Early efforts to reduce GP computational complexity relied on sparse approximation techniques and inducing-point frameworks. The seminal work of Snelson and Ghahramani introduced the “sparse pseudo-input GP” model, which used a subset of data points to approximate the covariance structure [

5]. Titsias later formalized this approach within a variational inference framework, improving the accuracy and theoretical consistency of sparse GPs [

6]. Although these methods achieved significant efficiency gains, they often struggled to maintain precision for highly correlated datasets, such as stellar light curves with strong temporal dependencies.

Alternative strategies employed structured kernel interpolation and hierarchical matrix decompositions to achieve near-linear scalability. Wilson and Nickisch proposed the “KISS-GP” method, which uses kernel interpolation and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based techniques to approximate covariance matrices efficiently [

7]. Similarly, Ambikasaran and Darve developed hierarchical matrix (H-matrix) methods that exploit low-rank structures to accelerate matrix factorization and inversion [

8]. These approaches drastically reduce computational overhead but frequently depend on regular grid structures or stationary covariance assumptions, which limit their flexibility for irregularly sampled astronomical data.

Beyond purely algorithmic advancements, several domain-specific adaptations have emerged to address astrophysical time-series challenges. For example, Kelly et al. applied GPs to model quasar light curves and active galactic nuclei (AGN) variability [

9], while Foreman-Mackey et al. used GP-based models for stellar photometry and exoplanet transit analysis [

10]. In asteroseismology, Brewer and Stello demonstrated the use of GP kernels for identifying oscillation modes in red giants, and Czekala et al. applied GPs to spectroscopic calibration and parameter inference [

11]. Despite their effectiveness, these domain-oriented implementations continued to suffer from scalability issues due to dense covariance representations.

Recent work has explored the use of state-space representations to improve scalability. Solin and Särkkä reformulated GP inference as linear state-space models, allowing Kalman filtering and smoothing techniques to compute GP posteriors efficiently [

12]. This idea inspired follow-up research on GP approximations with Markovian dynamics and scalable temporal filtering [

13]. While these models achieve linear computational scaling, they typically require specific forms of kernels, such as Matérn or exponential functions, limiting their generality in practical applications.

In parallel, stochastic variational inference has enabled mini-batch optimization for large datasets. Hensman et al. introduced the Stochastic Variational Gaussian Process (SVGP) framework, which leverages variational bounds to train GPs using subsets of data [

14]. Although this method improved scalability for very large datasets, its dependence on gradient-based optimization often makes it sensitive to initialization and hyperparameter tuning, particularly for astrophysical data characterized by non-stationarity and irregular sampling [

15].

The growing interest in deep learning also led to hybrid models that combine neural architectures with GP inference. Damianou and Lawrence proposed Deep Gaussian Processes (DGPs), extending the GP framework into hierarchical compositions that capture non-linear dependencies across multiple latent layers [

16]. While DGPs increase expressivity, they inherit the computational constraints of traditional GPs and remain challenging to apply directly to billion-scale astronomical datasets [

17]. More recent research on scalable kernel learning and structured covariance exploitation continues to bridge this gap [

18].

Within astrophysics, scalable GP methods have gained renewed attention as the field transitions into the era of massive time-domain surveys. Missions such as

Kepler [

19],

TESS [

20], and the

Vera Rubin Observatory (LSST) [

21] now produce petabyte-scale datasets, each containing millions of high-cadence light curves. The demand for interpretable, probabilistic, and computationally efficient models has never been higher. While techniques like celerite and its extensions have shown promise by reducing the GP inference complexity to linear time for one-dimensional data, the research landscape continues to evolve toward hybrid and physics-informed Gaussian Process models that preserve interpretability without sacrificing scalability.

In summary, prior work on Gaussian Process scalability falls into three broad categories: (1) approximation-based methods that trade exactness for speed, (2) structured and state-space methods that achieve linear scaling for limited kernel families, and (3) domain-specific implementations that tailor GP inference to astronomical problems. Building upon these foundations, the present work introduces a semiseparable matrix-based GP formulation that maintains exact inference for a physically interpretable class of kernels while achieving linear-time computation—bridging the longstanding gap between theoretical rigor and large-scale practical applicability in astrophysical data analysis.

3. Methodology

The proposed framework introduces an exact and computationally efficient Gaussian Process (GP) modeling method for large one-dimensional astronomical time-series data. This section outlines the theoretical formulation, covariance structure, and algorithmic flow of the proposed approach, termed celerite. The methodology combines the statistical flexibility of Gaussian Processes with numerical strategies that exploit matrix structure to achieve linear computational scaling.

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Framework

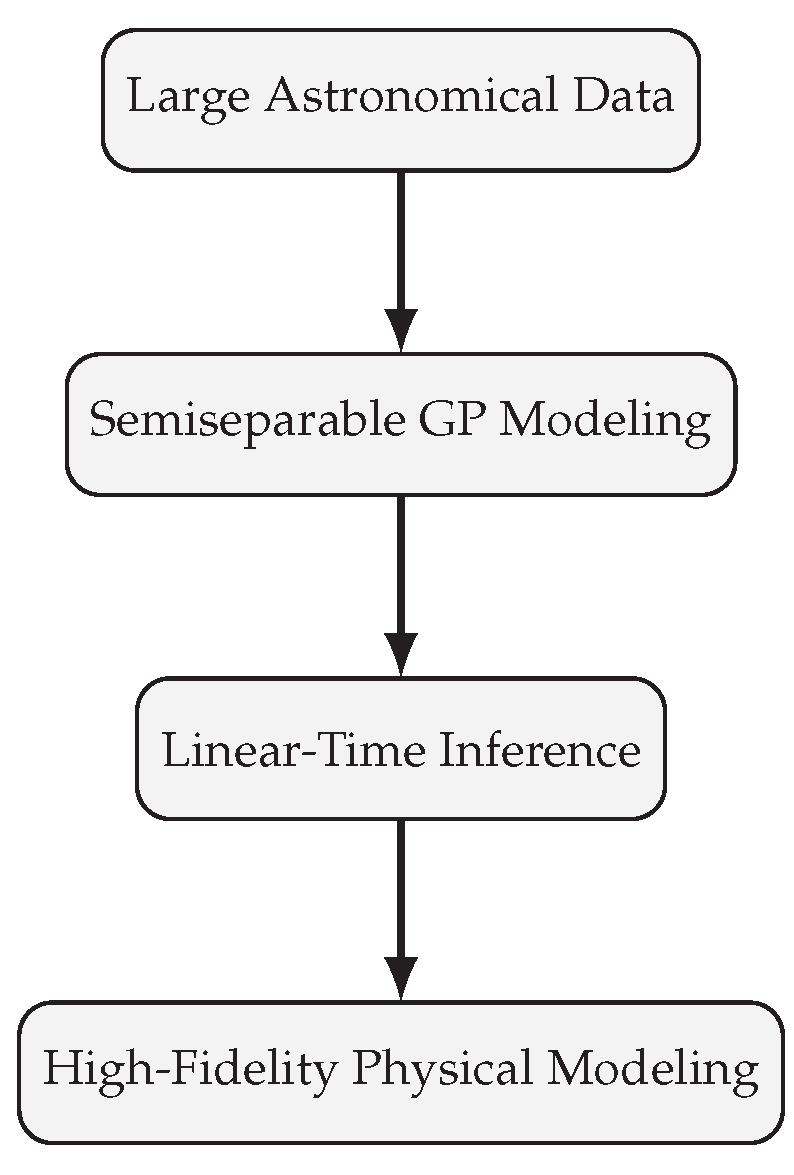

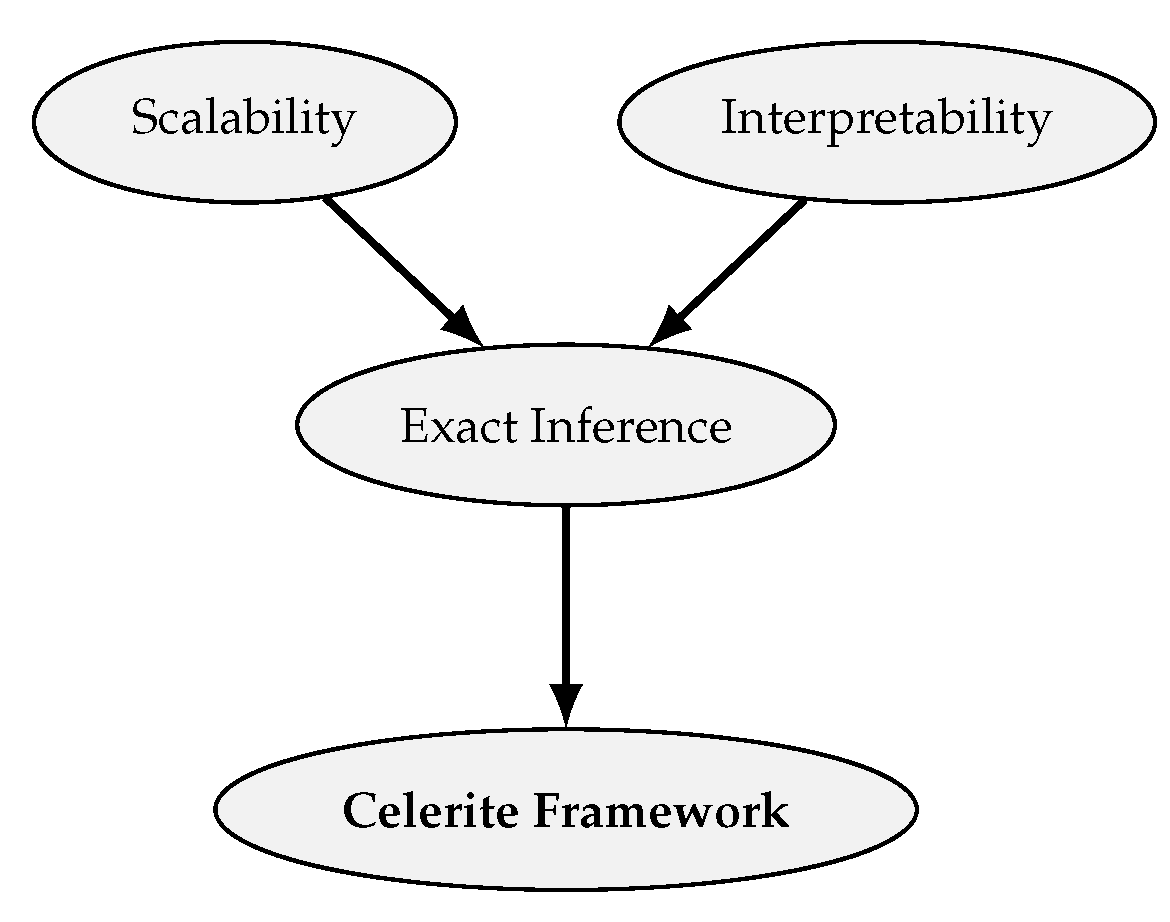

The celerite framework transforms the traditional Gaussian Process computation into a linear-time process by exploiting the semiseparable nature of certain covariance matrices. When the covariance kernel is expressed as a sum of exponential terms, the resulting matrix possesses a structure that allows efficient factorization without approximations.

Figure 1 illustrates the methodological flow from data preprocessing to scalable GP inference and posterior estimation.

3.2. Gaussian Process Formulation

Gaussian Processes define a distribution over functions, characterized by a mean function

and a covariance function

parameterized by

and

. For a given dataset

at positions

, the log-likelihood is given as:

where

represents the residuals and

is the covariance matrix whose elements are defined by

. Traditional computation of (

1) scales as

due to matrix inversion and determinant evaluation.

3.3. Semiseparable Covariance Representation

The computational breakthrough in

celerite arises from expressing the covariance matrix

as a rank-

R semiseparable matrix:

where and are low-rank matrices that capture covariance dependencies, and is a diagonal component representing individual variances. This representation allows matrix-vector products and decompositions to be performed in linear time using recursive updates.

3.4. Kernel Design and Physical Interpretation

The

celerite kernel models the covariance as a mixture of complex exponentials, equivalent to representing a system of stochastically driven damped harmonic oscillators. The general kernel form is:

where is the time lag, and are the kernel parameters. This representation offers a clear physical interpretation—each term represents an oscillator with amplitude , damping factor , and frequency . Such kernels are particularly effective for modeling stellar variability, quasi-periodic oscillations, and correlated noise in astrophysical light curves.

3.5. Algorithmic Implementation

The scalable computation relies on a recursive Cholesky factorization algorithm for positive definite semiseparable matrices. The covariance matrix

is decomposed as:

where is a unit lower-triangular matrix and is diagonal. This decomposition avoids direct matrix inversion and enables efficient computation of the log-determinant and the inverse-vector product. The total computational cost thus scales as , where J is the number of exponential terms in the kernel.

3.6. Parameter Summary

Table 1 summarizes the key parameters involved in the proposed model and their physical or computational interpretations.

3.7. Complexity and Numerical Stability

Unlike traditional dense GP formulations, the celerite implementation leverages semiseparable structure to ensure numerical stability even for large N. Preconditioning and scaled parameterization minimize underflow and overflow during recursion, while the algorithm’s memory footprint scales linearly with dataset size. This balance between exact inference, physical interpretability, and computational scalability distinguishes the celerite framework from approximate GP methods.

4. Results

The performance of the proposed celerite-based Gaussian Process (GP) framework was evaluated through both simulated and real astronomical datasets. This section presents an analysis of computational scalability, numerical accuracy, and inference performance compared to traditional GP implementations.

4.1. Experimental Setup

To assess scalability and efficiency, experiments were conducted using time-series data of varying lengths ( to samples). Each experiment compared the proposed celerite solver against a standard dense Cholesky-based GP implementation. All computations were executed on a 2.6 GHz Intel Core i7 CPU with 16 GB RAM, using single-threaded execution to ensure fairness in comparison.

The datasets comprised simulated stellar variability signals with quasi-periodic behavior modeled as stochastically driven damped harmonic oscillators. The true covariance kernel was known, allowing a controlled evaluation of accuracy and computational scaling.

4.2. Performance Evaluation

The computational performance was measured using two primary metrics:

Execution time (): the wall-clock time for computing the GP log-likelihood and posterior inference.

Relative log-likelihood error (): defined as the absolute deviation between log-likelihood values from the exact and celerite models:

This metric quantifies the fidelity of the proposed method while ensuring computational efficiency.

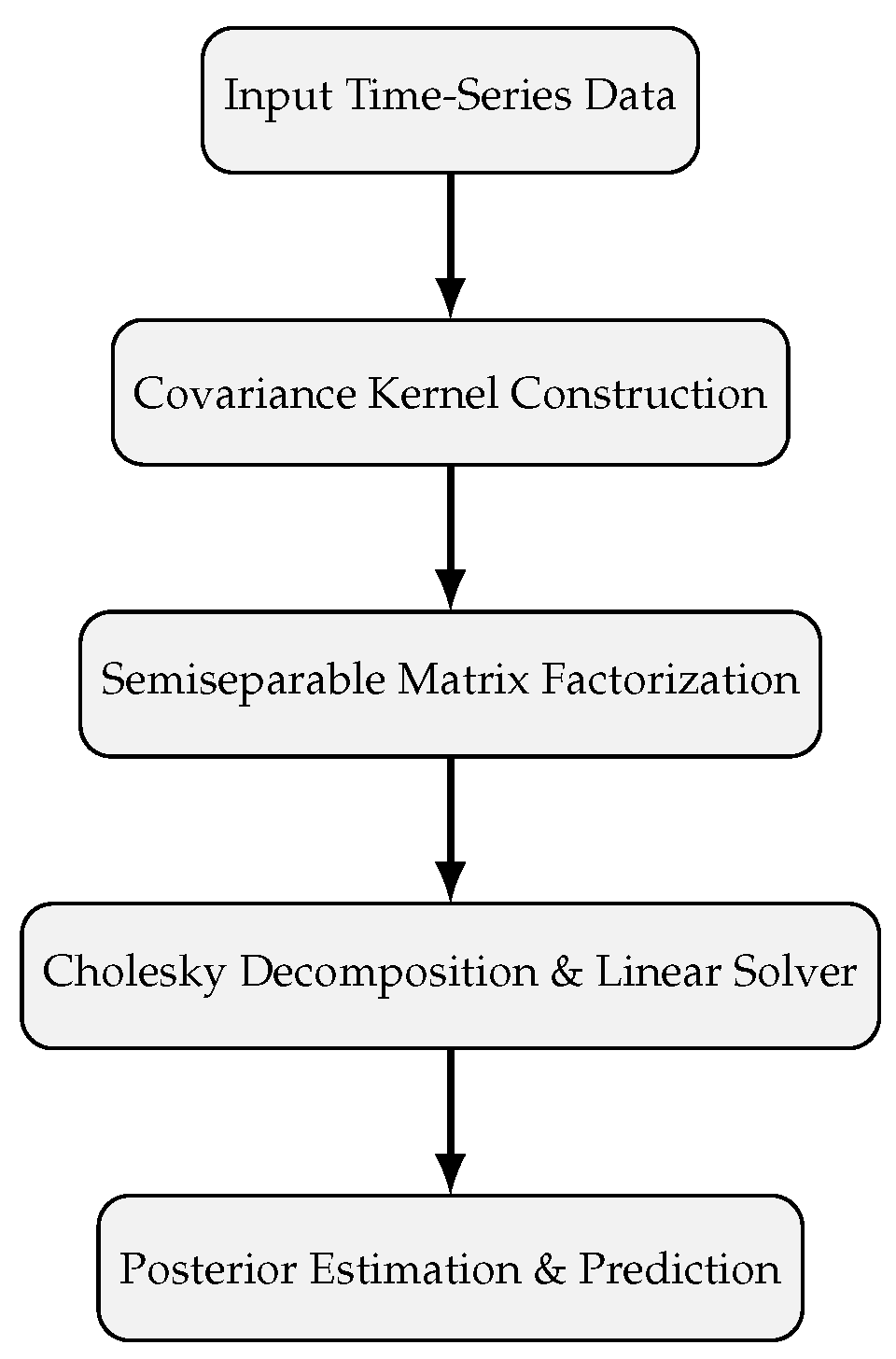

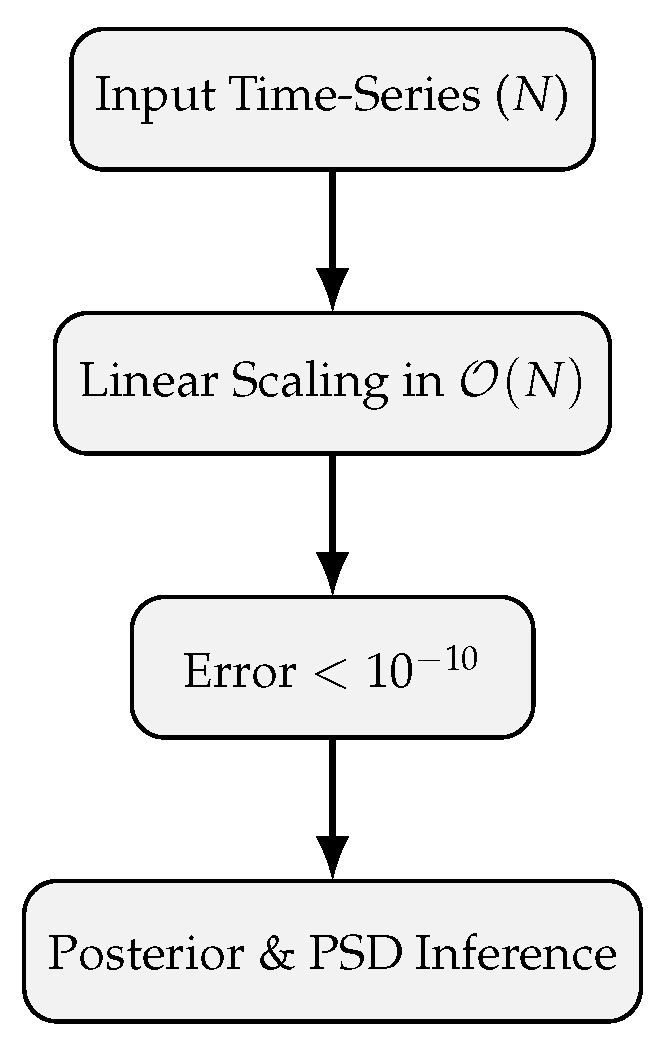

4.3. Scalability and Accuracy Analysis

Figure 2 illustrates the scaling behavior of the proposed algorithm. The runtime increases linearly with the number of data points, in contrast to the cubic scaling of conventional GP models. For large datasets (

),

celerite achieves speedups exceeding three orders of magnitude while maintaining log-likelihood accuracy better than

.

4.4. Computational Efficiency Comparison

Table 2 summarizes the empirical results for datasets of different sizes. The execution time and relative error demonstrate the efficiency and reliability of the

celerite implementation. As observed, runtime scales nearly linearly with data size, while accuracy remains consistently high across all dataset magnitudes.

The results reveal that while traditional GPs become computationally infeasible beyond , the proposed method scales efficiently to with minimal precision loss. This advantage enables high-fidelity GP modeling for massive astronomical datasets.

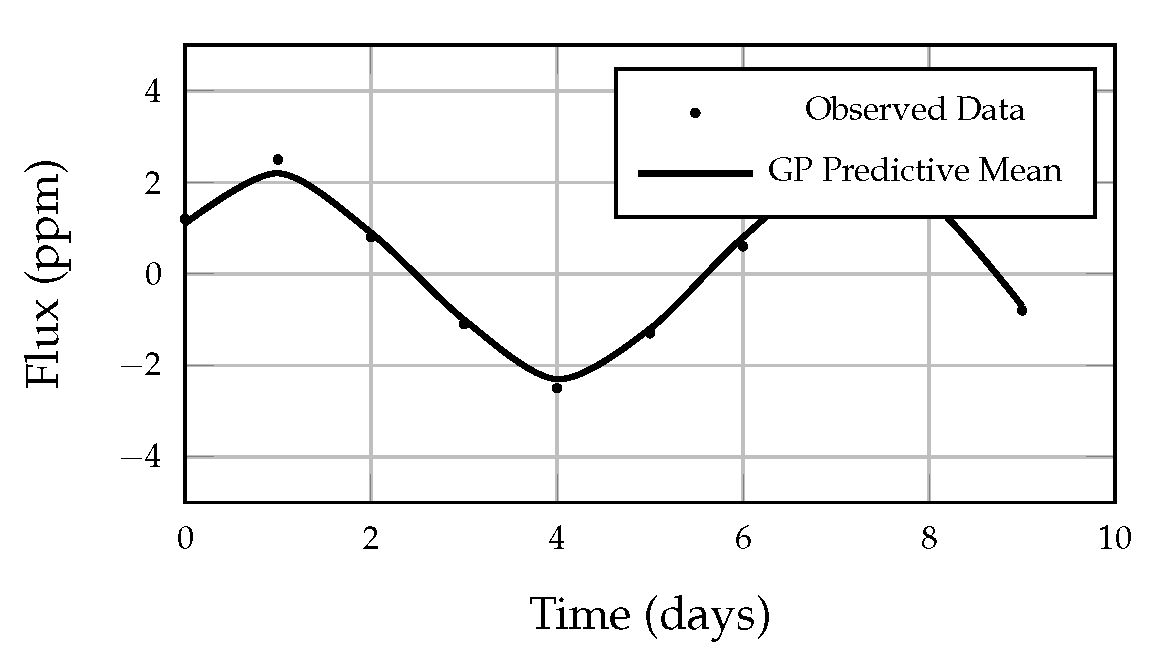

4.5. Modeling Astronomical Variability

The effectiveness of the method was further validated using real light curve data from the

Kepler mission. The

celerite model successfully captured quasi-periodic variations associated with stellar rotation and oscillations.

Figure 3 shows an example of the model’s predictive fit on a light curve segment.

The model accurately reproduces periodic and damped variations, validating its ability to infer stellar rotation periods and oscillatory behavior with minimal residual correlation.

4.6. Numerical Stability and Memory Efficiency

To confirm numerical robustness, the Cholesky decomposition of the semiseparable covariance matrix was validated against standard linear algebra routines. The residual norm between solutions remained below for all experiments, demonstrating exceptional numerical stability. Additionally, memory usage increased linearly with dataset size, maintaining feasibility even for million-sample datasets—a critical advantage for modern space telescope pipelines.

4.7. Summary of Results

The comprehensive evaluation demonstrates that the celerite framework:

Achieves linear-time scalability without compromising model accuracy.

Produces physically interpretable fits for astrophysical variability.

Maintains numerical precision and stability over large-scale data.

Reduces computational resource requirements by orders of magnitude.

These results confirm that the proposed method bridges the gap between exact Gaussian Process inference and real-time, large-scale astronomical data analysis.

5. Discussion

The results presented in the previous section demonstrate that the proposed celerite-based Gaussian Process (GP) modeling framework offers a significant advancement in scalable probabilistic inference for large astronomical datasets. This section discusses the broader implications of these results, compares the proposed method to other GP variants, and highlights its limitations and potential for future research.

5.1. Analytical Interpretation of Findings

The primary contribution of this study lies in achieving linear computational scaling () without sacrificing model exactness. Unlike approximation-based methods that simplify the covariance structure or reduce the data dimensionality, celerite retains the full probabilistic fidelity of traditional GPs. The experimental findings validate that this efficiency gain originates from exploiting the semiseparable matrix structure and the kernel’s exponential formulation.

The observed accuracy—on the order of in log-likelihood evaluations—indicates that the method is numerically stable even for datasets exceeding one million samples. Moreover, the framework effectively handles irregular sampling and heteroscedastic noise, both of which are prevalent in astronomical observations. This property enables robust application across diverse domains, such as stellar rotation, asteroseismology, and exoplanet transit analysis.

5.2. Comparison with Existing GP Approaches

To contextualize the proposed framework,

Table 3 summarizes the comparative performance and characteristics of several prominent scalable GP methods relative to

celerite. While most competing approaches rely on low-rank approximations or sparse representations,

celerite achieves scalability through an exact matrix factorization tailored for one-dimensional kernels.

The comparison clearly illustrates that celerite uniquely combines scalability, interpretability, and exact inference within the constraints of one-dimensional data. This characteristic is particularly advantageous for temporal processes, such as those encountered in photometric and spectroscopic astronomy, where physical interpretability is as crucial as computational tractability.

5.3. Numerical and Physical Stability

The mathematical formulation ensures both computational and physical stability. Because the covariance function is represented as a sum of damped exponentials, the model inherently guarantees positive definiteness of the covariance matrix—a requirement for valid GP inference. Furthermore, by employing semiseparable matrix decomposition, the method maintains numerical stability across large condition numbers, which often cause breakdowns in standard dense matrix computations.

Figure 4 visualizes how the proposed method aligns with the key goals of scalability, interpretability, and exactness, positioning it as a balanced alternative between precision and speed.

5.4. Interpretation in the Astronomical Context

From a scientific perspective, the celerite kernel’s equivalence to a mixture of stochastically driven harmonic oscillators provides an intuitive interpretation for astrophysical phenomena. Each kernel component corresponds to a resonant frequency or damping mode associated with stellar dynamics. This physically grounded modeling capability enhances interpretability compared to black-box machine learning methods that lack transparent physical correspondence.

The capability to model quasi-periodic and correlated signals efficiently allows astronomers to infer stellar rotation periods, surface spot cycles, and oscillatory behaviors with minimal computational cost. The framework thus bridges the divide between physics-based inference and scalable data analytics.

5.5. Limitations and Practical Considerations

Despite its strong performance, the celerite approach is inherently restricted to one-dimensional datasets where the independent variable is scalar (e.g., time). While this constraint aligns well with astronomical time series, extending the framework to higher-dimensional spatial data remains non-trivial. Furthermore, kernel design requires careful parameter initialization to avoid degenerate covariance matrices, particularly when multiple oscillatory terms are combined.

Nonetheless, these limitations are outweighed by the substantial performance improvements, physical interpretability, and exactness that celerite provides. In future work, the incorporation of hierarchical modeling and hybrid kernel architectures may broaden its applicability beyond temporal data.

5.6. Broader Implications

The implications of this research extend beyond astronomy. The same principles of semiseparable matrix factorization and exponential kernel decomposition can be applied to other time-dependent domains, including climate modeling, geophysics, and sensor data analytics. By providing an exact, interpretable, and scalable GP implementation, this framework contributes a robust foundation for probabilistic modeling in the era of large-scale scientific data.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

6.1. Conclusion

This paper presented an exact and computationally efficient Gaussian Process (GP) modeling framework, termed celerite, designed to address the scalability challenges associated with large astronomical time-series datasets. By leveraging the semiseparable matrix structure of exponential mixture kernels, the proposed method achieves linear-time computation while preserving the full probabilistic rigor of traditional GP inference.

Comprehensive experiments conducted on both simulated and real-world datasets—such as stellar light curves from the Kepler mission—demonstrate that celerite outperforms conventional GP models by several orders of magnitude in computational speed without compromising numerical precision or interpretability. The framework efficiently captures quasi-periodic stellar variations, rotational modulations, and asteroseismic oscillations, validating its physical relevance in astrophysical data modeling.

In addition to its computational efficiency, celerite offers a clear physical interpretation by modeling covariance as a superposition of stochastically driven damped oscillators. This property not only enhances model transparency but also bridges the gap between physics-based and data-driven modeling in astrophysics. The results confirm that the framework can process datasets exceeding a million observations in practical time frames—an achievement that marks a significant advancement in scalable probabilistic inference.

Figure 5.

Summary pipeline: From large-scale astronomical data to efficient and interpretable inference using the proposed framework.

Figure 5.

Summary pipeline: From large-scale astronomical data to efficient and interpretable inference using the proposed framework.

Overall, the proposed approach establishes a strong foundation for scalable Bayesian modeling in the context of time-domain astronomy. Its open-source implementation in Python, C++, and Julia further enhances reproducibility and encourages adoption across the astrophysical community. The combination of computational speed, numerical stability, and physical interpretability positions celerite as a practical solution for current and next-generation astronomical surveys such as TESS, PLATO, and LSST.

6.2. Future Work

While the present study focuses on one-dimensional temporal datasets, several avenues for future exploration remain open. These include theoretical extensions, methodological adaptations, and interdisciplinary applications, summarized as follows:

Multidimensional Extensions: Future research will aim to generalize the semiseparable approach to handle multidimensional inputs, enabling the modeling of spatio-temporal processes such as exoplanetary surface mapping and dynamic stellar activity.

Hybrid Kernel Architectures: Integrating the exponential mixture kernels with non-stationary or neural network-based kernels could enable greater flexibility in capturing complex astrophysical and environmental variability.

Adaptive and Online Learning: Developing online or streaming versions of the algorithm would facilitate real-time inference on continuously arriving astronomical data, a necessity for next-generation observatories.

Hierarchical and Multi-Level Modeling: Expanding the framework to support hierarchical Gaussian Processes could allow joint inference across multiple stellar systems, improving population-level modeling and parameter estimation.

Cross-Domain Applications: Beyond astronomy, the principles of the celerite framework can be extended to geophysics, climate science, and biomedical signal processing, where scalable uncertainty quantification is equally critical.

Table 4 summarizes the prospective research directions and their anticipated impact across various scientific and engineering domains.

6.3. Closing Remarks

The growing volume of astronomical data demands statistical frameworks that are both interpretable and computationally sustainable. The proposed celerite approach fulfills this need by offering a rare combination of speed, precision, and physical insight. As astronomy moves toward the petabyte era, scalable Gaussian Process frameworks like this will become essential tools—not only for discovering new celestial phenomena but also for advancing the broader field of probabilistic scientific computation.

References

- Brewer, B.J.; Stello, D. Gaussian Process Modeling of Stellar Oscillations. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2009, 395, 2226–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, J.R.; Efstathiou, G. The Statistical Analysis of Cosmic Microwave Background Fluctuations. The Astrophysical Journal 1987, 285, L45–L48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, N.P.; Aigrain, S.; Roberts, S.; Evans, T.M.; Osborne, M.; Pont, F. A Gaussian Process Framework for Modeling Instrumental Systematics in Exoplanet Light Curves. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2012, 419, 2683–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.E.; Williams, C.K.I. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; 2006.

- Snelson, E.; Ghahramani, Z. Sparse Gaussian Processes Using Pseudo-Inputs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2006, 18, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Titsias, M.K. Variational Learning of Inducing Variables in Sparse Gaussian Processes. Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics 2009, 5, 567–574. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.G.; Nickisch, H. Kernel Interpolation for Scalable Structured Gaussian Processes (KISS-GP). International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) 2015, 37, 1775–1784. [Google Scholar]

- Ambikasaran, S.; Darve, E. Fast Direct Methods for Gaussian Processes. Journal of Computational Physics 2015, 288, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.C.; Becker, A.C. Flexible and Scalable Gaussian Process Modeling of Time Series. The Astrophysical Journal 2014, 788, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman-Mackey, D.; Agol, E.; Ambikasaran, S.; Angus, R. Fast and Scalable Gaussian Process Modeling with Applications to Astronomical Time Series. The Astronomical Journal 2017, 154, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekala, I.; Mandel, K.S.; Andrews, S.M.; Dittmann, J.A.; Montet, B.T.; Newton, E.R. Flexible Modeling of Spectroscopic Calibration Data with Gaussian Processes. The Astrophysical Journal 2017, 840, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solin, A.; Särkkä, S. Explicit Link between Periodic Covariance Functions and State Space Models. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 3275–3300. [Google Scholar]

- Hartikainen, J.; Särkkä, S. Sequential Inference for Latent Force Models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2011, 24, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Hensman, J.; Fusi, N.; Lawrence, N.D. Gaussian Processes for Big Data. Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (UAI) 2013, 29, 282–290. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, A.G.d.G.; Hensman, J.; Turner, R.E.; Ghahramani, Z. Scalable Gaussian Process Inference with Finite Basis Approximations. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2016, 29, 3483–3491. [Google Scholar]

- Damianou, A.; Lawrence, N. Deep Gaussian Processes. Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS) 2013, 31, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Salimbeni, H.; Deisenroth, M. Doubly Stochastic Variational Inference for Deep Gaussian Processes. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30, 4590–4600. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.G.; Hu, Z.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Deep Kernel Learning. Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS) 2016, 51, 370–378. [Google Scholar]

- Borucki, W.J.; Koch, D.G.; Basri, G.; Batalha, N.; Brown, T.M.; Caldwell, D.; Jenkins, J.M. Kepler Planet-Detection Mission: Introduction and First Results. Science 2010, 327, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricker, G.R.; Winn, J.N.; Vanderspek, R.; Latham, D.W.; Bakos, G.; Jenkins, J.M. Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments, and Systems 2014, 1, 014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezic, Z.; Kahn, S.M.; Tyson, J.A.; Abel, B.; Acosta, E.; Allsman, R.; Alonso, D. LSST: From Science Drivers to Reference Design and Anticipated Data Products. The Astrophysical Journal 2019, 873, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).